The Mouse and the Snake

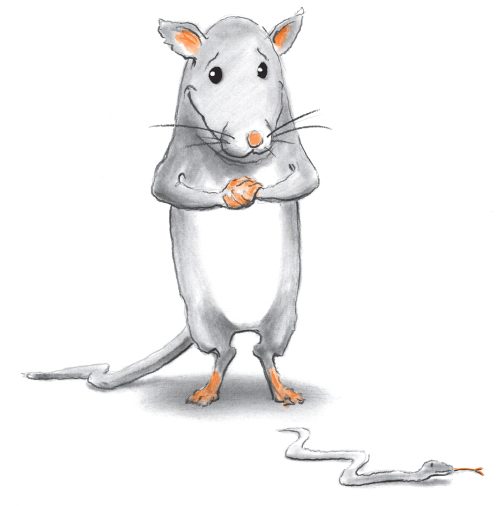

Plenty of animals had pets, but few were more devoted than the mouse, who owned a baby corn snake—“A rescue snake,�� she’d be quick to inform you. This made it sound like he’d been snatched from the jaws of a raccoon, but what she’d really rescued him from was a life without her love. And what sort of a life would that have been?

“I saw him hatching from his little egg and knew right then that I had to save him,” she was fond of saying. “I mean, look at that face! How could I have said no!” The snake would flick his split ribbon of tongue, and his mistress would dandle the scales beneath his chin. “He’s saying, ‘Hello, new friend. Nice to meet you!’ ”

But the friends weren’t so sure. When the serpent coiled, they jumped and fretted, reactions that left the mouse feeling almost unbelievably special—exotic, really, which was different from eccentric. To qualify for the latter, all you needed was a turban and an affinity for ridiculously large beads or the color purple. To be exotic, on the other hand, one had to think not just outside the box but outside the world of boxes.

“You’re not afraid of my snake,” the mouse would insist. “You’re afraid of the idea of him. Why, this little fellow wouldn’t strike if his life depended on it. Haven’t I explained that?” She’d then describe how he slept at the foot of her bed and woke her each morning with a kiss. “He says, ‘Get up, Mommy. It’s time to start the day!’ ”

The snake was the smartest, the handsomest, the most thoughtful creature that had ever lived. The way he lay in the sun or stared dumbly into space for hours on end—it was uncanny. “He thinks he’s one of us,” the mouse told her friends, who responded with increasingly forced smiles. In time she stopped using the word “pet,” as it seemed demeaning. The term “to own” was banished as well, as it made it sound as though she were keeping him against his will, like a firefly trapped in a jar. “He’s a reptile companion,” she took to saying, and thus, in time, he became her only companion.

This suited the mouse just fine. “I never had anything in common with them anyway,” she said. “Not even the ones my own age.” The snake blinked as if to say, All we need is each other, and the mouse reached out to hug his slender neck. It was almost spooky how like-minded they were: On the weather, on the all-important hoard or binge question, the two were most definitely on the same page. Both liked weekends, both hated owls; their opinions differed only when it came to food. “Won’t you at least try a bit of grain?” the mouse had asked when the snake was very young. He wouldn’t, though, preferring instead a live baby toad. How he could eat these things was beyond her. She’d taken a bite once, just to see what it was like, and the ghost of it, viscous and fishy, had lingered in her mouth for days.

You couldn’t expect a youngster, especially such a vulnerable one, to hunt his own food, and so the mouse did it for him. Aside from baby toads, she’d fetched him a robin’s egg and a very young mole, which, like everything else, he ate whole. “My goodness,” she said. “Slow down. Taste!”

In those first few months, their lunch was followed by a speech-therapy session. “Can you say, ‘Hello, mouse friend’? Can you say, ‘I love you’?”

Eventually she saw the chauvinism of her attempt. Why should he learn to speak like a rodent? Why not the other way around? Hence she made it her business to try and master snake. After weeks of getting nowhere she split her tongue with a razor. This didn’t make it any easier to communicate, but it did give them something else in common.

The two were in front of the fireplace one afternoon, softly hissing at each other, when someone knocked on the door. It was a toad, and after a great sigh at the inconvenience, the mouse stepped onto the front stoop to greet her. Even without the mimeographed flyers under her arm, anyone could have guessed why she was here: it was that “long-suffering mother” look so common to amphibians, who had children by the thousands and then fell apart when a handful were sacrificed to a higher cause.

“I’m sorry to barge in on you this way,” the toad said, “but a few of my babies has taken off and I’m just about at my wit’s end.” She blew her nose into her open palm, then wiped the snotty hand against her thigh. “They’s girls as well as boys. Nine in all, and wasn’t a one of them old enough to fend for themselves.”

It was this last part that tested the mouse’s patience—fend for themselves—as if a toad needed any particular training. They hatched, they opened their eyes, and then they hopped around, each one as graceless and unappealing as a stone.

“Well,” the mouse said, “if you were that concerned for the safety of your children, you probably should have kept an eye on them.”

“But I did,” wept the toad. “They was just outside, playing in the yard, like youngsters do.”

Playing indeed, thought the mouse, and she recalled the patch of sandy soil, bare but for a single, withered dandelion. The area bordered a thicket of tall ferns, and that was where she had hidden herself and lured the listless, gullible children with the promise of cluster flies. If they hadn’t been starving, and possibly brain damaged due to their upbringing, they wouldn’t have so blindly followed her. So really, wasn’t this the toad’s fault? Where was her pity when flies came to the door, asking about their missing babies? Was an insect’s mother love any less worthy than an amphibian’s? And wasn’t the snake a baby as well, as cute and innocent and deserving of protection as any other living creature?

It pained the mouse to realize that, while he’d always be adorable, her companion was not the little one he had been. In the months since she’d rescued him, he’d grown almost five inches, and there seemed to be no stopping him. Underage toads would not suffice for much longer, and so the mouse accepted a leaflet and studied it for a moment. “I’ll tell you what,” she said. “How’s about I keep my eyes open, and you check back with me in, oh, say, about two weeks or so. How does that sound?”

A few days later there came another knock, this time from a mole. “I’m wondering,” she asked, “if you’ve by any chance seen my daughter?”

“Well, I don’t know,” the mouse said. “What did she look like?”

The mole shrugged. “Don’t know exactly. I guess most likely she looked like me but smaller.”

“It’s a shame when things you love go missing,” the mouse said. “Take these grubs, for instance. I had a whole colony living in my backyard, darlings, every one. And just so smart you couldn’t keep up with them. One minute they were there, and the next thing I knew they’d taken off—no note or anything.”

Her visitor looked at the ground for a moment, and the mouse thought, Exactly. If awards were given to the world’s biggest hypocrites, you’d be hard-pressed to choose between the moles and the toads.

“To answer your question, I did meet a little mole,” the mouse said. “A girl it was, said she’d run away from home and asked if she could come live with me for a while. I told her, ‘Well, maybe you should think it over and not be so rash.’ I said, ‘Why don’t you see how you feel in a month, and then come back?’ ”

“A month!” wailed the mole.

“That’s what I told her, so why don’t you do the same? If your daughter is here, I’ll keep her for you, and if not, at least you tried.”

Off went the mole, buoyed with hope, and the mouse stepped back into her house. “Idiot,” she whispered. The snake lifted its flat head off the carpet, and she explained that from now on, his meals would deliver themselves. “That’s all the more time we can spend together,” she said. “Would you like that, baby? I know you would.”

Out slid the snake’s forked tongue, and she thought again that she had never seen such a beautiful creature. Smart too. Beautiful and smart, and above all loyal.

A month later the mole was back. She stood at the door, knocking politely, and just as she began pounding, the toad hopped by. “If you’re looking for that mouse, I think you can probably forget it,” she called.

The mole whirled around and squinted.

“I came by two weeks ago and did just what you’re doing. Knocked on that door till I just about busted it, but didn’t nobody answer. Then I talked to some squirrels yonder, and they said there hadn’t been smoke out the chimney since the beginning of the month. Strange, they said, because that mouse always had a fire going, even in summer. Their guess and mine too is that she took off, maybe found a mate or something. You know how mice are—anything for a little affection.”

The mole, distressed, spilled out the story of her missing child. The toad did the same. But had they not wept and commiserated, had they instead put their ears to the door, they might have heard the snake, his belly full of unconditional love, banging to be let out.