THE HOLY UNSPEAKABLE NAME OF GOD

The Ogham Craobh, which is printed in Ledwich’s Antiquities of Ireland and attested by an alphabetic inscription at Callen, County Clare, Ireland, ascribed to 295 AD, runs as follows:

B L N T S B D T C Q M G Ng Z R

This is the ordinary Ogham alphabet as given by Macalister; except that where one would expect F and H it has T and B – the very consonants which occur mysteriously in Hyginus’s account of the seven original letters invented by the Three Fates. There was evidently a taboo at Callen on the F and H – T and B had to be used instead; and it looks as if just the same thing had happened in the 15-consonant Greek alphabet known to Hyginus, and that he refrained from specifying Palamedes’s contribution of eleven consonants because he did not wish to call attention to the recurrence of B and T.

If so, the Palamedes alphabet can be reconstructed as follows in the Ogham order:

B L N F S H D T C M G [Ng] R

There is no warrant for Ng in Greek, so I have enclosed it in square brackets, but it must be remembered that the original Pelasgians talked a non-Greek Language. This had nearly died out by the fifth century BC but, according to Herodotus, survived in at least one of the oracles of Apollo, that of Apollo Ptous, which was in Boeotian territory. He records that a certain Mys, sent by the son-in-law of King Darius of Persia to consult the Greek oracles, was attended by three Boeotian priests with triangular writing tablets. The priestess made her reply in a barbarous tongue which Mys, snatching a tablet from one of the priests, copied down. It proved to be in the Carian dialect, which Mys understood, being a ‘European’, that is to say of Cretan extraction – Europë, daughter of Agenor, having ridden to Crete from Phoenicia on the back of a bull. If Cretan was, as is probable, a Hamitic language it may well have had Ng at place 14. Ng is not part of the Greek alphabet and Dr. Macalister points out that even in Old Goidelic no word began with Ng, and that such words as ngomair, and ngetal which occur in the Ogham alphabets as the names of the Ng letter are wholly artificial forms of gomair and getal. But in Hamitic languages the initial Ng is common, as a glance at the map of Africa will show.

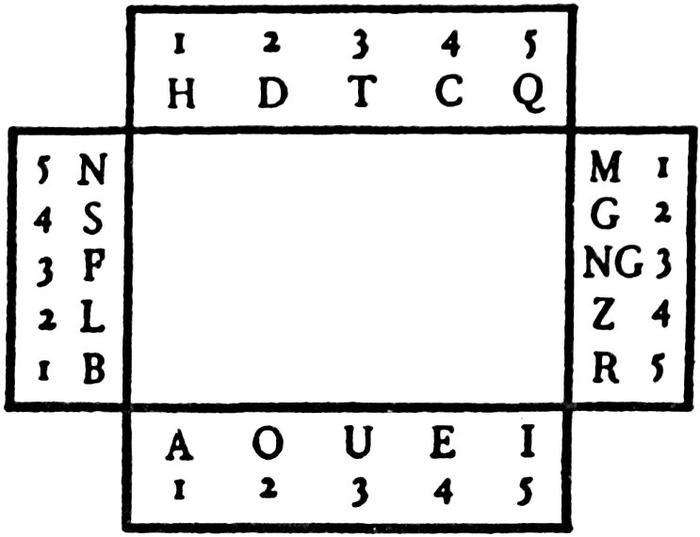

The existence of this dubious Pelasgian letter Ng, which had not been borrowed by the makers of the Cadmean alphabet, may explain the uncertainty of ‘twelve, or some say thirteen letters’ ascribed by Diodorus Siculus to the Pelasgian alphabet; and may also explain why Ng in the middle of a word was in Greek spelt GG, as Aggelos for Angelos, G being the letter which immediately precedes Ng in the Beth-Luis-Nion. Yet from the analogy of the Beth-Luis-Nion it may be suspected that the Palamedes alphabet contained two secret letters which brought the number up to fifteen. The Latin alphabet at any rate was originally a 15-consonant one, with 5 vowels, and was probably arranged by ‘Carmenta’ as follows:

B L F S N H D T C Q M G Ng P R

For the Romans continued to use the Ng sound at the beginning of words in Republican times – they even spelt natus as gnatus, and navus (‘diligent’) as gnavus – and probably pronounced it like the gn in the middle of such French words as Catalogne and seigneur.

It looks as if Epicharmus was the Greek who invented the early form of the Cadmean alphabet mentioned by Diodorus as consisting of sixteen consonants, namely the thirteen of the Palamedes alphabet as given above, less the Ng; plus Zeta, and Pi as a substitute for Koppa (Q); plus Chi and Theta. But only two letters are ascribed to Epicharmus by Hyginus; and these are given in the most reputable MSS. as Chi and Theta. So Pi (or Koppa) and Zeta are likely to have been concealed letters of the Palamedes alphabet, as Quert and Straif are concealed letters of the Beth-Luis-Nion; not mentioned by Hyginus because they were merely doubled C and S.

We know that Simonides then removed the H aspirate and also the F, Digamma, which was replaced by Phi, and added Psi and Xi and two vowels – long E, Eta, to which he assigned the character of H aspirate, and long O, Omega; which brought the total number of letters up to twenty-four.

All these alphabets seem to be carefully designed sacred alphabets, not selective Greek transcriptions of the commercial Phoenician alphabet of twenty-six letters as scratched on the Formello-Cervetri vases. One virtue of the Epicharmian alphabet lay in its having sixteen consonants – sixteen being the number of increase – and twenty-one letters in all, twenty-one being a number sacred to the Sun since the time of the Pharaoh Akhenaton who introduced into Egypt about the year 1415 BC the monotheistic cult of the sun’s disc. Epicharmus, as an Asclepiad, was descended from the Sun.

It must be noted that Simonides’s new consonants were artificial ones – previously Xi had been spelt chi-sigma and Psi, pi-sigma – and that there was no real need for them compared, for instance, with the need of new letters to distinguish long from short A, and long from short I. I suspect Simonides of having composed a secret alphabetical charm consisting of the familiar letter-names of the Greek alphabet arranged with the vowels and consonants together, in three eight-letter parts, each letter suggesting a word of the charm; for example xi, psi might stand for xiphon psilon, ‘a naked sword’. Unfortunately the abbreviations of most of the Greek letter names are too short for this guess to be substantiated; it is only an occasional letter, like lambda, which seems to stand for lampada (‘torches’) and sigma, which seems to stand for sigmos (‘a hissing for silence’), that hints at the secret.

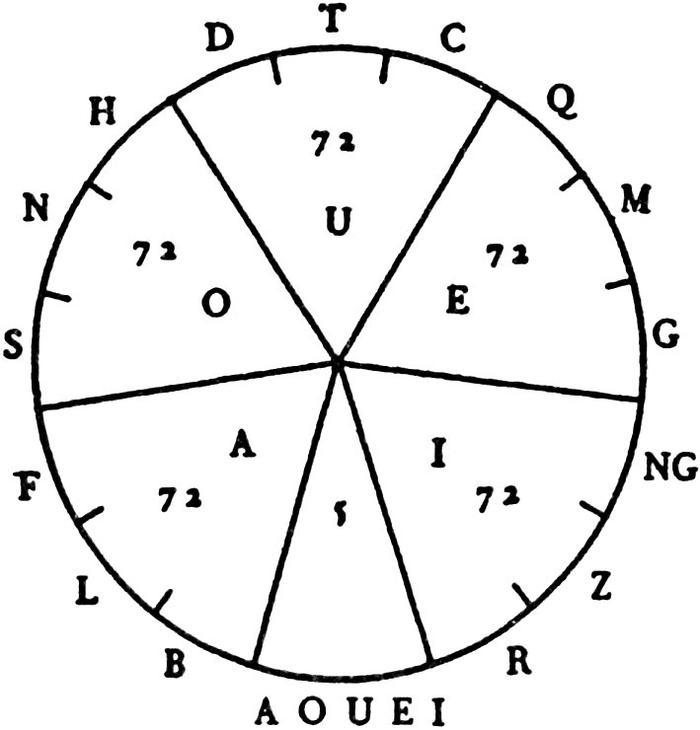

But can we guess why Simonides removed F and H from the alphabet? And why Hyginus the Spaniard and the author of the Irish Callen inscription used B and T as cipher disguises for these same two letters? We can begin by noting that the Etruscan calendar, which the Romans adopted during the Republic, was arranged in nundina, or eight-day periods, in Greek called ‘ogdoads’ and that the Roman Goddess of Wisdom, Minerva, had 5 (written V) as her sacred numeral. We can identify Minerva with Carmenta, because she was generally credited at Rome with the invention of the arts and sciences and because flower-decorated boats, probably made of alder wood, were sailed on her festival, the Quinquatria. ‘Quinquatrid’ means ‘the five halls’, presumably five seasons of the year, and was celebrated five days after the Spring New Year feast of the Calendar Goddess Anna Perenna; this suggests that the five days were those left over when the year had been divided into five seasons of 72 days each, the sanctity of the five and the seventy-two having been similarly established in the Beth-Luis-Nion system.

An alphabet-calendar arranged on this principle, with the vowels kept apart from the consonants, implies a 360-day year of five vowel-seasons, each of 72 days, with five days left over; each season being divided into three periods each consisting of twenty-four days. The 360-day year can also be divided, in honour of the Triple Goddess, into three 120-day seasons each containing five periods of equal length, namely twenty-four days – with the same five days over; and this is the year that was in public use in Egypt. The Egyptians said that the five days were those which the God Thoth (Hermes or Mercury) won at draughts from the Moon-goddess Isis, composed of the seventy-second parts of every day in the year; and the birthdays of Osiris, Horus, Set, Isis and Nephthys were celebrated on them in this order. The mythic sense of the legend is that a change of religion necessitated a change of calendar: that the old Moon-goddess year of 364 days with one day over was succeeded by a year of 360 days with five over, and that in the new system the first three periods of the year were allotted to Osiris, Horus and Set, and the last two to Isis and Nephthys. Though, under Assyrian influence, each of the three Egyptian seasons was divided into four periods of 30 days, not five of 24, the 72-day season occurs in the Egypto-Byblian myth that the Goddess Isis hid her child Horus, or Harpocrates, from the rage of the ass-eared Sun-god Set during the 72 hottest days of the year, namely the third of the five seasons, which was astronomically ruled by the Dog Sirius and the two Asses. (The hiding of the Child Horus seems to have been assisted by the Lapwing, a bird much used in the Etruscan science of augury which the Romans borrowed; at any rate, Pliny twice mentions in his Natural History that the Lapwing disappears completely between the rising of Sirius and its setting.)

But here the argument must be held up by a discussion of Set and his worship.

The Greek legend that the God Dionysus placed the Asses in the Sign of Cancer (‘the Crab’) suggests that the Dionysus who visited Egypt and was entertained by Proteus King of Pharos was Osiris, brother of the Hyksos god Typhon, alias Set. The Hyksos people, non-Semitic pastoralists, coming from Armenia or beyond, pressed down through Cappadocia, Syria and Palestine into Egypt about the year 1780 BC. That they managed so easily to establish themselves in Northern Egypt with their capital at Pelusium, on the Canopic arm of the Nile Delta, can be accounted for only by an alliance with the Byblians of Phoenicia. Byblos, a protectorate of Egypt from very early times, was the ‘Land of Negu’ (‘Trees’) from which the Egyptians imported timber, and a cylinder seal of the Old Empire shows Adonis, the God of Byblos, in company with the horned Moon-goddess Isis, or Hathor, or Astarte. The Byblians who, with the Cretans, managed the Egyptian carrying-trade – the Egyptians hated the sea – had trading stations at Pelusium and elsewhere in Lower Egypt from very early times. To judge from the Homeric legend of King Proteus, the earliest Pelasgian settlers in the Delta used Pharos, the lighthouse island off what afterwards became Alexandria, as their sacred oracular island. Proteus, the oracular Old Man of the Sea, who was King of Pharos and lived in a cave – where Menelaus consulted him – had the power of changing his shape, like Merddin, Dionysus, Atabyrius, Llew Llaw, Periclymenus and all Sun-heroes of the same sort. Evidently Pharos was his Isle of Avalon. That Apuleius connects the sistrum of Osiris, used to frighten away the God Set, with Pharos suggests that Proteus and Osiris were there regarded as the same person. Proteus, according to Virgil, had another sacred island, Carpathus, between Crete and Rhodes; but that was the Thessalian Proteus. Another Proteus, spelt Proetus, was an Arcadian.

It would be a great mistake to think of Pharos as a secluded sacred island inhabited only by the attendants of the oracle: when Menelaus came there with his ships he was entering the largest port in the Mediterranean.1 Gaston Jondet in his Les ports submergés de l’ancienne Île de Pharos (1916) has established the existence here even in pre-Hellenic times of a vast system of harbour-works, now submerged, exceeding in extent the island itself. They consisted of an inner basin covering 150 acres and an outer basin of about half that area, the massive sea-walls, jetties and quays being constructed of enormous stones, some of them weighing six tons. The work seems to have been carried out towards the end of the third millennium BC by Egyptian labour according to plans submitted to the local authorities by Cretan or Phoenician marine architects. The wide landing-quay at the entrance to the port consisted of rough blocks, some of them sixteen feet long, deeply grooved with a chequer-work of pentagons. Since pentagons are inconvenient figures for a chequer, compared with squares and hexagons, the number five must have had some important religious significance. Was Pharos the centre of a five-season calendar system?

The island was oddly connected with the numbers five and seventy-two at the beginning of the Christian era: the Jews of Alexandria used to visit the island for an annual (five-day?) festival, the excuse for which was that the Five Books of Moses had been miraculously translated there into Greek by seventy-two doctors of the Law (‘the Septuagint’) who had worked for seventy-two days on them, each apart from the rest, and agreed exactly in their renderings at the conclusion of their task. There is something behind this myth. All similar festivals in the ancient world commemorated some ancient tribal treaty or act of confederacy. What the occasion here was remains obscure, unless the Pharaoh who married Sarah, the goddess mother of the ‘Abraham’ tribe that visited Egypt at the close of the third millennium, was the priest-king of Pharos. If so, the festival would be a record of the sacred marriage by which the ancestors of the Hebrews joined the great confederacy of the Peoples of the Sea, whose strongest base was Pharos. Hebrews seem to have been in continuous residence in Lower Egypt for the next two millennia, and the meaning of the festival would have been forgotten by the time that the Pentateuch was translated into Greek.

In the Odyssey, which is a popular romance not at all to be depended on for mythical detail, Proteus’s transformations are described as lion, serpent, panther, boar, water, fire and leafy tree. This is a mixed list,1 reminding one of Gwion’s deliberately muddled ‘I have been’s’. The boar is the symbol of the G month; lion and serpent are seasonal symbols; the panther is a mythical beast half-leopard, half-lion, sacred to Dionysus. It is a pity that Homer does not particularize the leafy tree; its association here with water and fire suggests the alder, or cornel-tree, as sacred to Proteus, a god of the Bran type – though in the story Proteus is degraded to a mere herdsman of seals in the service of the Ash-god Poseidon.

The Nile is called Ogygian by Aeschylus, and Eustathius the Byzantine grammarian says that Ogygia was the earliest name for Egypt. This suggests that the Island of Ogygia ruled over by Calypso daughter of Atlas, was really Pharos where Proteus, alias Atlas or ‘The Sufferer’, had an oracular shrine. Pharos commanded the mouth of the Nile, and Greek sailors would talk of ‘sailing to Ogygia’ rather than ‘sailing to Egypt’; it often happens that a small island used as a trading depot gives its name to a whole province – Bombay is a useful example. The waters of Styx are also called Ogygian by Hesiod; not (as Liddell and Scott suggest) because Ogygian meant vaguely ‘primeval’, but because the head-waters were at Lusi, the seat of the three oracular daughters of Proetus, who is apparently the same cult-character as Proteus.

When the Byblians first brought their Syrian Tempest-god to Egypt, the one who, disguised as a boar, yearly killed his brother Adonis, the god always born under a fir-tree, they identified him with Set, the ancient Egyptian god of the desert whose sacred beast was the wild ass, and who yearly destroyed his brother Osiris, the god of the Nile vegetation. This must be what Sanchthoniatho the Phoenician, in a fragment preserved by Philo, means when he says that the mysteries of Phoenicia were brought to Egypt. He reports that the two first inventors of the human race, Upsouranios and his brother Ousous consecrated two pillars, to fire and wind – presumably the Jachin and Boaz pillars representing Adonis, god of the waxing year and the new-born sun, and Typhon, god of the waning year and of destructive winds. The Hyksos Kings under Byblian influence, similarly converted their Tempest-god into Set, and his new brother, the Hyksos Osiris, alias Adonis, alias Dionysus, paid a courtesy call on his Pelasgian counterpart, Proteus King of Pharos.

In pre-dynastic times Set must have been the chief of all the gods of Egypt, since the sign of royalty which all the dynastic gods carried was Set’s ass-eared reed sceptre. But he had declined in importance before the Hyksos revived his worship at Pelusium, and reverted to obscurity after they were thrown out of Egypt about two hundred years later by the Pharaohs of the 18th Dynasty.1 The Egyptians identified him with the long-eared constellation Orion, ‘Lord of the Chambers of the South’, and ‘the Breath of Set’ was the South wind from the deserts which, then as now, caused a wave of criminal violence in Egypt, Libya and Southern Europe whenever it blew. The cult of ass-eared Set in Southern Judaea is proved by Apion’s account of the golden ass-mask of Edomite Dora, captured by King Alexander Jannaeus and cleverly stolen back again from Jerusalem by one Zabidus. The ass occurs in many of the more obviously iconotropic anecdotes of Genesis and the early historical books of the Bible: Saul chosen as king when in search of Kish’s lost asses; the ass that was with Abraham when he was about to sacrifice Isaac; the ass whose jawbone Samson used against the Philistines; the ass of Balaam with its human voice. Moreover, Jacob’s uncle Ishmael son of Hagar with his twelve sons is described in Genesis, XVI, 12 as a wild ass among men: this suggests a religious confederacy of thirteen goddess-worshipping tribes of the Southern desert, under the leadership of a tribe dedicated to Set. Ishmael perhaps means ‘the beloved man’, the Goddess’s favourite.

The legend of Midas the Phrygian and the ass’s ears confirms this association of Dionysus and Set, for Midas, son of the Mother Goddess, was a devotee of Dionysus. The legend is plainly an iconotropic one and Midas has been confidently identified with Mita, King of the Moschians, or Mushki, a people from Thrace – originally from Pontus – who broke the power of the Hittites about the year 1200 BC when they captured Pteria the Hittite capital. Mita was a dynastic name and is said to have meant ‘seed’ in the Orphic language; Herodotus mentions certain rose-gardens of Midas on Mount Bermios in Macedonia, planted before the Moschian invasion of Asia Minor. It is likely that their Greek name Moschoi, ‘calf-men’, refers to their cult of the Spirit of the Year as a bull-calf: a golden calf like that which the Israelites claimed to have brought them safely out of Egypt.

That no record has survived in Egypt of a five-season year concurrent with the three-season one, is no proof that it was not in popular use among the devotees of Osiris. For that matter absolutely no official Pharaonic record has been found in Egypt of the construction, or even the existence, of the port of Pharos though it commanded the mouths of the Nile, controlled the South-Eastern terminus of the Mediterranean sea-routes, and was in active use for at least a thousand years. Osiris worship was the popular religion in the Delta from pre-dynastic times, but it had no official standing. Egyptian texts and pictorial records are notorious for their suppression or distortion of popular beliefs. Even the Book of the Dead, which passes for popular, seldom expresses the true beliefs of the Osirian masses: the aristocratic priests of the Established Church had begun to tamper with the popular myth as early as 2800 BC. One of the most important elements in Osirianism, tree-worship, was not officialized until about 300 BC, under the Macedonian Ptolemies. In the Book of the Dead many primitive beliefs have been iconotropically suppressed. For instance, at the close of the Twelfth Hour of Darkness, when Osiris’ sun-boat approaches the last gateway of the Otherworld before its reemergence into the light of day, the god is pictured bent backwards in the form of a hoop with his hands raised and his toes touching the back of his head. This is explained as ‘Osiris whose circuit is the Otherworld’: which means that by adopting this acrobatic posture he is defining the Otherworld as a circular region behind the ring of mountains that surround the ordinary world, and thus making the Twelve Hours analogous with the Twelve Signs of the Zodiac. Here an ingenious priestly notion has clearly been superimposed on an earlier popular icon: Osiris captured by his rival Set and tied, like Ixion or Cuchulain, in the five-fold bond that joined wrists, neck and ankles together. ‘Osiris whose circuit is the Otherworld’ is also the economical way of identifying the god with the snake Ophion, coiled around the habitable earth, a symbol of universal fertility out of death.

Gwion’s ‘Ercwlf’ (Hercules) evidently used the three-season year when he laid his ‘four pillars of equal height’, the Boibel-Loth, in order [see overleaf]. The vowels represent the five extra days, the entrance to the year, and the lintel and two pillars each represent 120 days. But Q and Z have no months of their own in the Beth-Luis-Nion and their occurrence as twenty-four day periods in the second part of the Boibel-Loth year makes Tinne, not Duir as in the Beth-Luis-Nion, the central, that is the ruling, letter. Tinnus, or Tannus, becomes the chief god, as in Etruria and Druidic Gaul. From this figure the transition to the disc arrangement is simple:

As 8 is the sacred numeral of Tinne’s month – and in the Imperial Roman Calendar also the ruling month was the eighth, called Sebastos (‘Holy’) or Augustus – so the eight-day period rules the calendar. In fact, Tannus displaces his oak-twin Durus and seems to be doing him a great kindness – the same kindness celestial Hercules did for Atlas – in relieving him of his traditional burden. The twins were already connected with the numeral 8 because of their eight-year reign, which was fixed (as we have seen) by the approximation at every hundredth lunation of lunar and solar time. That a calendar of this sort was in use in ancient Ireland is suggested by numerous ancient Circles of the Sun, consisting of five stones surrounding a central altar; and by the ancient division of the land into five provinces – Ulster, the two Munsters, Leinster and Connaught – meeting at a central point in what is now West Meath, marked by a Stone of Divisions. (The two Munsters had already coalesced by the time of King Tuathal the Acceptable, who reigned from 130–160 AD; he took off a piece of all four provinces to form his central demesne of Meath.) And there is a clear reference to this calendar system in the tenth-century AD Irish Saltair na Rann where a Heavenly City is described, with fifteen ramparts, eight gates, and seventy-two different kinds of fruit in the gardens enclosed.

*

Now, it has been shown that the God Bran possessed an alphabetic secret before Gwydion, with Amathaon’s help, stole it from him at the Battle of the Trees in the course of the first Belgic invasion of Britain; that close religious ties existed between Pelasgia and Bronze Age Britain; and that the Pelasgians used an alphabet of the same sort as the British tree-alphabet, the trees of which came from the north of Asia Minor.

As might be expected, the myth connecting Cronos, Bran’s counterpart, with an alphabetic secret survives in many versions. It concerns the Dactyls (fingers), five beings created by the White Goddess Rhea, ‘while Zeus was still an infant in the Dictaean Cave’, as attendants on her lover Cronos. Cronos became the first king of Elis, where the Dactyls were worshipped, according to Pausanias, under the names of Heracles, Paeonius, Epimedes, Jasius and Idas, or Aces-Idas. They were also worshipped in Phrygia, Samothrace, Cyprus, Crete and at Ephesus. Diodorus quotes Cretan historians to the effect that the Dactyls made magical incantations which caused a great stir in Samothrace, and that Orpheus (who used the Pelasgian alphabet) was their disciple. They are called the fathers of the Cabeiroi of Samothrace, and their original seat is said to have been either Phrygia or Crete. They are also associated with the mysteries of smith-craft, and Diodorus identifies them with the Curetes, tutors of the infant Zeus and founders of Cnossos. Their names at Elis correspond exactly with the fingers. Heracles is the phallic thumb; Paeonius (‘deliverer from evil’) is the lucky fore-finger; Epimedes (‘he who thinks too late’) is the middle, or fool’s, finger; Jasius (‘healer’) is the physic finger; Idas (‘he of Mount Ida’ – Rhea’s seat) is the oracular little finger. The syllable Aces means that he averted ill-luck, and the Orphic willow tree, the tree belonging to the little finger-tip, grew just outside the Dictaean Cave which was, perhaps for that reason, also called the Idaean Cave.

The Alexandrian scholiast on Apollonius Rhodius gives the names of three of the Dactyls as Acmon (‘anvil’) Damnameneus (‘hammer’) and Celmis (‘smelter’). These are probably names of the thumb and first two fingers, used in the Phrygian (or ‘Latin’) blessing: for walnuts are cracked between thumb and forefinger; and the middle finger based on U, the vowel of sexuality, still retains its ancient obscene reputation as the smelter of female passion. In mediaeval times it was called digitus impudicus or obscenus because, according to the seventeenth-century physician Isbrand de Diemerbroek, it used to be ‘pointed at men in infamy or derision’ – as a sign that they had failed to keep their wives’ affection. Apollonius had mentioned only two Dactyls by name: Titias and Cyllenius. I have shown that Cyllen (or Cyllenius) was son of Elate, ‘Artemis of the fir tree’; so the Dactyl Cyllenius must have been the thumb, which is based on the fir-letter A. And Titias was king of Mariandynë in Bithynia, from where Hercules stole the Dog, and was killed by Hercules at a funeral games. Some mythographers make Titias the father of Mariandynus, founder of the town. Since Hercules was the god of the waxing year which begins with A, the thumb, it follows that Titias was the god of the waning year, which begins with U, the fool’s finger – the fool killed by Hercules at the winter-solstice. The name ‘Titias’ is apparently a reduplication of the letter T, which belongs to the fool’s finger, and identical with the Giant Tityus whom Zeus killed and consigned to Tartarus.

Here is a neat problem in poetic logic: if the Dactyl Cyllenius is an alias of Hercules, and Hercules is the thumb, and Titias is the fool’s finger, it should be possible to find in the myth of Hercules and Titias the name of the intervening finger, the forefinger, to complete the triad used in the Phrygian blessing. Since the numerical sequence Heis, Duo, Treis, ‘one, two, three’, corresponds in Greek, Latin and Old Goidelic with the H.D.T. letter sequence represented by the top-joints of the Dactyls used in this blessing, it is likely that the missing name begins with D and has a reference to the use or religious associations of the finger. The answer seems to be ‘Dascylus’. According to Apollonius he was king of the Mariandynians, and presided at the games at which Hercules killed Titias. For the forefinger is the index-finger and Dascylus means ‘the little pointer’ Greek didasco, Latin disco. Presidents at athletic contests use it for solemn warnings against foul play. The root Da- from which Dascylus is derived is also the root of the Indo-Germanic word for thunder, appropriate to D as the letter of the oak-and-thunder god. Dascylus was both father and son of Lycus (wolf); the wolf is closely connected with the oak-cult.

The argument can be taken farther. It has been mentioned in Chapter Four that Pythagoras was a Pelasgian from Samos who developed his doctrine of the Transmigration of Souls as the result of foreign travel. According to his biographer Porphyrius he went to Crete, the seat of the purest Orphic doctrine, for initiation by the Idaean Dactyls. They ritually purified him with a thunderbolt, that is to say they made a pretence of killing him with either a meteoric stone or a neolithic axe popularly mistaken for a thunderbolt; after which he lay face-downwards on the sea shore all night covered with black lamb’s wool; then spent ‘three times nine hallowed days and nights in the Idaean Cave’; finally emerged for his initiation. Presumably he then drank the customary Orphic cup of goat’s milk and honey at dawn (the drink of Cretan Zeus who had been born in that very cave) and was garlanded with white flowers. Porphyrius does not record exactly when all this took place except that Pythagoras saw the throne annually decorated with flowers for Zeus; which suggests that the twenty-eight days that intervened between his thunderbolt death and his revival with milk and honey were the twenty-eight-day month R, the death-month ruled by the elder or myrtle; and that Pythagoras was reborn at the winter solstice festival as an incarnation of Zeus – a sort of Orphic Pope or Aga Khan – and went through the usual mimetic transformation: bull, hawk, woman, lion, fish, serpent, etc. This would account for the divine honours subsequently paid him at Crotona, where the Orphic cult was strongly established; and also for those paid to his successor Empedocles, who claimed to have been through these ritual transformations. The Dactyls here are plainly the Curetes, the dancing priests of the Rhea and Cronos cult, tutoring the infant Zeus in the Pelasgian calendar-alphabet, the Beth-Luis-Nion; the tree-sequence of which had been brought to Greece and the Aegean islands from Paphlagonia, by way of Bithynian Mariandynë and Phrygia, and there harmonized with the alphabetic principle originated in Crete by ‘Palamedes’. For climatic reasons the canon of trees taught by the Cretan Dactyls must have differed from that of Phrygia, Samothrace and Magnesia – Magnesia where the five Dactyls were remembered as a single character, and where the Pelasgian Cheiron (‘the Hand’) son of Cronos and Philyra (Rhea), successively tutored Hercules, Achilles, Jason the Orphic hero, with numerous other sacred kings.

It seems however that Pythagoras,1 after mastering the Cretan Beth-Luis-Nion, found that the Boibel-Loth calendar, based on a year of 360 + 5 days, not on the Beth-Luis-Nion year of 364 + 1 days, was far better suited than the Beth-Luis-Nion to his deep philosophic speculations about the holy tetractys, the five senses and elements, the musical octave, and the Ogdoad.

But why was it necessary to alter the alphabet and calendar in order to make eight the important number, rather than seven? Simonides’s alphabet, it has been seen, was expanded to 3 × 8 letters; perhaps this was to fulfil the dark prophecy current in Classical Greece that Apollo was fated to castrate his father Zeus with the same sickle with which Zeus had castrated his father Cronos and which was laid up in a temple on the sickle-shaped island of Drepane (‘sickle’), now Corfu. In so far as the supreme god of the Druids was a Sun-god, the fulfilment of this prophecy was demonstrated every year at their ritual emasculation of the sacred oak by the lopping of the mistletoe, the procreative principle, with a golden sickle – gold being the metal sacred to the Sun. Seven was the sacred number of the week, governed by the Sun, the Moon and the five planets. But eight was sacred to the Sun in Babylonia, Egypt and Arabia, because 8 is the symbol of reduplication – 2 × 2 × 2. Hence the widely distributed royal sun-disc with an eight-armed cross on it, like a simplified version of Britannia’s shield; and hence the sacrificial barley-cakes baked in the same pattern.

Now to examine Diodorus’s famous quotation from the historian Hecateus (sixth century BC):

Hecateus, and some others, who treat of ancient histories or traditions, give the following account: ‘Opposite to the coast of Celtic Gaul there is an island in the ocean, not smaller than Sicily, lying to the North – which is inhabited by the Hyperboreans, who are so named because they dwell beyond the North Wind. This island is of a happy temperature, rich in soil and fruitful in everything, yielding its produce twice in the year. Tradition says that Latona was born there, and for that reason, the inhabitants venerate Apollo more than any other God. They are, in a manner, his priests, for they daily celebrate him with continual songs of praise and pay him abundant honours.

‘In this island, there is a magnificent grove (or precinct) of Apollo, and a remarkable temple, of a round form, adorned with many consecrated gifts. There is also a city, sacred to the same God, most of the inhabitants of which are harpers, who continually play upon their harps in the temple, and sing hymns to the God, extolling his actions. The Hyperboreans use a peculiar dialect, and have a remarkable attachment to the Greeks, especially to the Athenians and the Delians, deducing their friendship from remote periods. It is related that some Greeks formerly visited the Hyperboreans, with whom they left consecrated gifts of great value, and also that in ancient times Abaris, coming from the Hyperboreans into Greece, renewed their family intercourse with the Delians.

‘It is also said that in this island the moon appears very near to the earth, that certain eminences of a terrestrial form are plainly seen in it, that Apollo visits the island once in a course of nineteen years, in which period the stars complete their revolutions, and that for this reason the Greeks distinguish the cycle of nineteen years by the name of “the great year”. During the season of his appearance the God plays upon the harp and dances every night, from the vernal equinox until the rising of the Pleiads, pleased with his own successes. The supreme authority in that city and the sacred precinct is vested in those who are called Boreadae, being the descendants of Boreas, and their governments have been uninterruptedly transmitted in this line.’

Hecateus apparently credited the pre-Belgic Hyperboreans with a knowledge of the 19-year cycle for equating solar and lunar time; which involves an intercalation of 7 months at the close. This cycle was not publicly adopted in Greece until about a century after Hecateus’s time. As a ‘golden number’, reconciling solar and lunar time, 19 can be deduced from the thirteen-month Beth-Luis-Nion calendar which contains fourteen solar stations (namely the first day of each month and the extra day) and five lunar stations. Probably it was in honour of this Apollo (Beli) that the major stone circles of the Penzance area in Cornwall consisted of 19 posts, and that Cornwall was called Belerium. There is evidently some basis for the story that Abaris the Hyperborean instructed Pythagoras in philosophy. It looks as if the Bronze Age people (who imported the Egyptian beads into Salisbury Plain from Akhenaton’s short-lived capital, the City of the Sun, at Tell Amarna about 1350 BC) had refined their astronomy on Salisbury Plain and even anticipated the invention of the telescope. Since, according to Pliny, the Celtic year began in his day in July (as the Athenian also did) the statement about the country producing two harvests, one at the beginning and one at the end of the year, is understandable. The hay harvest would fall in the old year, the corn harvest in the new.

The Lord of the Seven-day Week was ‘Dis’, the transcendental god of the Hyperboreans, whose secret name was betrayed to Gwydion. Have we not already stumbled on the secret? Was the Name not spelt out by the seven vowels of the threshold, cut with three times nine holy nicks and read sunwise?

Or in Roman letters: JIEVOAŌ

If so, the link between Britain and Egypt is evident: Demetrius, the first-century BC Alexandrian philosopher, after discussing in his treatise On Style the elision of vowels and hiatus, and saying that ‘with elision the effect is duller and less melodious’, illustrates the advantage of hiatus with:

In Egypt the priests sing hymns to the gods by uttering the seven vowels in succession, the sound of which produces as strong a musical impression on their hearers as if flute and lyre were used. To dispense with the hiatus would be to do away altogether with the melody and harmony of language. But perhaps I had better not enlarge of this theme in the present context.

He does not say what priests they were or to what gods they addressed themselves, but it is safe to guess that they were the gods of the seven-day week, comprising a single transcendent deity, and that the hymn contained the seven vowels with which Simonides provided the Greek alphabet and was credited with a therapeutic effect.

When the Name was revealed, Amathaon and Gwydion instituted a new religious system, and a new calendar, and new names of letters, and installed the Dog, Roebuck and Lapwing as guardians not of the old Name, which he had guessed, but of the new. The secret of the new Name seems to be connected with the substitution of the sacred numeral 7 by the sacred numeral 8, and with a taboo on the letters F and H in ordinary alphabetic use. Was it that the Name was given 8 letters instead of 7? We know from Hyginus’s account that Simonides added Omega (long O, and Eta (long E) to the original seven letters AOUEIFH, invented by the Fates, ‘or some say, by Mercury’, and that he also removed H aspirate from the alphabet by allotting its character to Eta. If he did this for religious reasons, the eight-fold Name of God, containing the Digamma F (V) and H aspirate – the Lofty Name which gave Gwion his sense of power and authority – was perhaps:

JEHUOVAŌ

but spelt, for security reasons, as:

JEBUOTAŌ

It certainly has an august ring, lacking to ‘Iahu’ and ‘Jahweh’, and if I have got it right, will be ‘the eight-fold City of Light’ in which the ‘Word’, which was Thoth, Hermes, Mercury and, for the Gnostics, Jesus Christ was said to dwell. But the Fates had first invented F and H; why?

JIEVOAŌ, the earlier seven-letter form, recalls the many guesses at the ‘blessed Name of the Holy One of Israel’ made by scholars, priests and magicians in the old days. This was a name which only the High Priest was allowed to utter, once a year and under his breath, when he visited the Holy of Holies, and which might not be committed to writing. Then how in the world was the Name conveyed from one High Priest to another? Obviously by a description of the alphabetical process which yielded it. Josephus claimed to know the Name, though he could never have heard it spoken or seen it written. The Heads of the Pharisaic academies also claimed to know it. Clement of Alexandria did not know it, but he guessed an original IAOOUE – which is found in Jewish-Egyptian magical papyri, ‘Zeus, Thunderer, King Adonai, Lord Iaooue’ – also expanded to IAOUAI and IAOOUAI. The disguised official formula, JEHOWIH, or JEHOWAH, written JHWH for short, suggests that by the time of Jesus the Jews had adopted the revised Name. The Samaritans wrote it IAHW and pronounced it IABE. Clement’s guess is, of course, a very plausible one because I.A.O.OU.E is the name spelt out by the vowels of the five-season year if one begins in the early winter, the opening of the agricultural year.1 The Name taught in the Academies is likely to have been a complicated one of either 42 or 72 letters. Both forms are discussed by Dr. Robert Eisler in the Jubilee volume for the Grand Rabbi of France in La Revue des Études Juives. The calendar mystery of 72 has already been discussed; that of 42 belongs to the Beth-Luis-Nion system.2

In Chapter Nine the first-century writer Aelian was quoted as having said that Hyperborean priests regularly visited Tempe. But if their business was with Apollo, why did they not go to the more important shrine of Delphi? Tempe, Apollo’s earlier home, lies in the valley of the Peneus between Mounts Ossa and Olympus and seems to have become the centre of a cult of a Pythagorean god who partook of the natures of all the Olympian deities. We know something about the mysteries of the cult because Cyprian, a third-century bishop of Antioch, was initiated into them as a youth of fifteen. As he records in his Confession, he was taken up on to Mount Olympus for forty days and there seven mystagogues taught him the meaning of musical sounds and the causes of the birth and decay of herbs, trees and bodies. He had a vision of tree-trunks and magical herbs, saw the succession of seasons and their changing spiritual representatives, together with the retinues of various deities, and watched the dramatic performances of demons in conflict. In an Egyptian magical papyrus published by Parthey in 1866, a close connexion between this Druid-like instruction and Essene mysticism is made in the following lines:

Come foremost angel of great Zeus IAO [Raphael]

And thou too, Michael, who holdest Heaven [rules the planets],

And Gabriel thou, the archangel from Olympus.

Gabriel, it has been shown, was the Hebrew counterpart of Hermes, the official herald and mystagogue of Mount Olympus.

Was Stonehenge the temple of Apollo the Hyperborean? The ground plan of Stonehenge suggests a round mirror with a handle – a round earthwork, entered by an avenue, with a circular stone temple enclosed. The outer ring of stones in the temple once formed a continuous circle of thirty arches, built of enormous dressed stones: thirty posts and thirty lintels. This circle enclosed an ellipse, broken at one end so that it resembled a horseshoe, consisting of five separate dolmens, each of two posts and a lintel, built of the same enormous stones. Sandwiched between the circle and the horseshoe stood a ring of thirty much smaller posts; and within the horseshoe, again, stood another horseshoe of fifteen similar small posts, arranged in five sets of three to correspond with the five dolmens.

Perhaps ‘horseshoe’ is wrong: it may well have been an ass-shoe from its narrowness. If Stonehenge was Apollo’s temple and if Pindar, in his Tenth Pythian Ode, is referring to the same Hyperboreans as Hecateus it must have been an ass-shoe; for Pindar shows that Apollo was worshipped by the Hyperboreans in the style of Osiris or Dionysus, whose triumph over his enemy Set the ass-god was celebrated by the sacrifice of a hundred asses at a time. But it is clear that by the middle of the fifth century BC, the connexion between Greece and the Hyperboreans had long been broken, presumably by the seizure of the approaches to Britain by the Belgic tribes.

Pindar is demonstrably wrong in his Third Olympian Ode when he makes Hercules go to the springs of the Ister to bring back wild olive to Olympia from the servants of Apollo, the Hyperboreans. We know from other sources that he fetched back the white poplar, not the olive which had been cultivated in Greece centuries before his time and which is not native to the upper Danube; the connexion of poplar with amber, which came from the Baltic by way of the Danube and Istria, and which was sacred to Apollo, has already been noted. Pindar’s mistake derives from a confusion of the Hercules who fetched the poplar from Epirus with the earlier Hercules who fetched the olive from Libya to Crete. He writes in the Tenth Pythian Ode:

Neither by ships nor by land can you find the wonderful road to the trysting-place of the Hyperboreans.

Yet in times past, Perseus the leader of his people partook of their banquet when he entered their homes and found them sacrificing glorious hecatombs of asses in honour of the God. In the banquets and hymns of that people Apollo chiefly rejoices and laughs as he looks upon the brute beasts in their ramping lewdness. Yet such are their ways that the Muse is not banished, but on every side the dances of the girls, the twanging of lyres and sound of flutes are continually circling, and with their hair crowned with golden bay-leaves they make merry…yet avoid divine jealousy by living aloof from labour and war. To that home of happy folk, then, went Danaë’s son [Perseus] of old, breathing courage, with Athena as his guide. And he slew the Gorgon and returned with her head.

Pindar seems to be wrong about the Gorgon and about the bay-leaves, sacred to Apollo only in the South; and since he does not tell us at what season the sacrifice took place we cannot tell what leaves they were. If at mid-winter, they may have been elder-leaves; at any rate, asses are connected in European folk-lore, especially French, with the mid-winter Saturnalia, which took place in the elder month, and at the conclusion of which the ass-eared god, later the Christmas Fool, was killed by his rival. This explains the otherwise unaccountable connexion of asses and fools in Italy as well as in Northern Europe: for asses are more intelligent animals than horses. That there was an ass-cult in Italy in early times is suggested by the distinguished Roman clan-names Asina and Asellus, which were plebeian, not patrician; the patricians were an immigrant horse-worshipping aristocracy from the East who enslaved the plebeians. The use of holly at the Italian Saturnalia supports this theory: holly was the tree of the ass-god, as the oak was the tree of his wild-ox twin who became paramount in patrician Rome.

Plutarch in his Isis and Osiris writes: ‘Every now and then at certain festivities they (the Egyptians) humiliate the broken power of Set, treating it despitefully, to the point of rolling men of Typhonic colouring in the mud and driving asses over a precipice.’ By ‘certain festivities’ he must mean the celebration of the divine child Harpocrates’s victory over Set, at the Egyptian Saturnalia. So Set, the red-haired ass, came to mean the bodily lusts, given full rein at the Saturnalia, which the purified initiate repudiated; indeed, the spirit as rider, and the body as ass, are now legitimate Christian concepts. The metamorphosis of Lucius Apuleius into an ass must be understood in this sense: it was his punishment for rejecting the good advice of his well-bred kinswoman Byrrhaena and deliberately meddling with the erotic witch cult of Thessaly. It was only after uttering his de profundis prayer to the White Goddess (quoted at the close of Chapter Four) that he was released from his shameful condition and accepted as an initiate of her pure Orphic mysteries. So also, when Charitë (‘Spiritual Love’) was riding home in chaste triumph on ass-back from the robbers’ den, Lucius had joked at this as an extraordinary event: namely, that a girl should triumph over her physical desires, despite all dangers and assaults. The Orphic degradation of the ass explains a passage in Aristophanes’s Frogs, which, as J. E. Harrison points out, is staged in a thoroughly Orphic Hell. Charon shouts out ‘Anyone here for the Plains of Lethe? Anyone here for the Ass Clippings? For Cerberus Park? Taenarus? Crow Station?’ Crow Station was evidently Set-Cronos’s infernal seat to which Greeks consigned their enemies in the imprecation ‘To the Crows with you!’; and the Ass Clippings was the place where criminals shaggy with sin were shorn to the quick. The horse was a pure animal for the Orphics, as the ass was impure, and the continuance of this tradition in Europe is shown most clearly in Spain where caballero ‘horseman’, means gentleman and where no gentleman’s son is allowed to ride an ass, even in an emergency, lest he lose caste. The ancient reverence of unchivalrous Spaniards for the ass appears perversely in the word carajo, the great mainstay of their swearing, which is used indiscriminately as noun, adjective, verb or adverb; its purpose is to avert the evil eye, or ill-luck, and the more often it can be introduced into an oath, the better. Touching the phallus, or an amulet in phallus form, is an established means of averting the evil eye, and carajo means ‘ass’s phallus’; the appeal is to the baleful God Set, whose starry phallus appears in the Constellation Orion, to restrain his anger.

The great dolmens of Stonehenge, all of local stone, look as if they were erected to give importance to the smaller stones, which were placed in position shortly after they themselves were, and to the massive altar stone lying in the centre. It has been suggested that the smaller ones, which are known to have been transported all the way from the Prescelly Mountains in Pembrokeshire, were originally disposed in another order there and rearranged by the people who erected the larger ones. This is likely, and it is remarkable that these imported stones were not dressed until they were re-erected at Stonehenge itself. The altar stone has also been transported from the same region, probably from Milford Haven. Since this transportation was done over a thousand years before the Belgic invasion it is clear at least that Gwydion was not responsible for the building.

The plan of the five dolmens corresponds exactly with the disc alphabet, since there is a broad gap between the two standing nearest to the avenue (like the gap which contains the five holy days of the Egyptian, or Etruscan, year) and between the gap and the avenue stood a group of four smaller undressed stones, corresponding with the groups of three stones in the inner horseshoe, but with a gap in the middle; and far back, in the avenue itself, the huge undressed ‘Heel’ stone made a fifth and central one. This is not to assume that Stonehenge was built to conform with the disc-alphabet. The calendar may have anteceded the alphabet by some centuries. All that seems clear is that the Greek alphabetic formula which gives the Boibel-Loth its letter-names is at least a century or two earlier than 400 BC when the Battle of the Trees was fought in Britain.

The formula is plain. The Sun-god of Stonehenge was the Lord of Days, and the thirty arches of the outer circle and the thirty posts of the inner circle stood for the days of the ordinary Egyptian month; but the secret enclosed by these circles was that the solar year was divided into five seasons, each in turn divided into three twenty-four-day periods, represented by the three stones of the dolmens, and each of these again into three ogdoads, represented by the three smaller posts in front of the dolmens. For the circle was so sited that at dawn of the summer solstice the sun rose exactly at the end of the avenue in dead line with the altar and the Heel stone; while, of the surviving pair of the four undressed stones, one marks the sun’s rising at the winter solstice, the other its setting at the summer solstice.

But why were the altar stone and the uprights transported all the way from South Wales? Presumably to break the religious power of the Pembrokeshire Death-goddess – the pre-Celtic Annwm, as we have seen, was in Pembroke – by removing her most sacred undressed stones and reerecting them, dressed, on the Plain. According to Geoffrey of Monmouth, this was done by Merlin. Geoffrey, who mistakenly dates the event to the time of Hengist and Horsa, says that Merlin obtained the stones from Ireland, but the tradition perhaps refers to the Land of Erin – Erin, or Eire or Eriu, being a pre-Celtic Fate-goddess who gave her name to Ireland. ‘Erin’, usually explained as the dative case of Eriu’s name, may be the Greek Triple Fate-goddess ‘Erinnys’ whom we know as the Three Furies. The amber found in the barrows near Stonehenge is for the most part red, not golden; like that found on the Phoenician coast.

Seventy-two will have been the main canonical number at Stonehenge: the seventy-two days of the midsummer season. Seventy-two was the Sun’s grandest number; eight, multiplied ninefold by the fertile Moon. The Moon was Latona, Hyperborean Apollo’s mother, and she determined the length of the sacred king’s reign. The approximate concurrence of solar and lunar time once every nineteen years – 19 revolutions of the Sun, 235 lunations of the Moon – ruled that Apollo should be newly married and crowned every nineteenth year at the Spring solstice, when he kept a seven months’ holiday in the Moon’s honour. The number 19 is commemorated at Stonehenge in nineteen socket-holes arranged in a semicircle on the South-east of the arched circle.1 The fate of the old king was perhaps the hill-top fate of Aaron and of Moses, darkly hinted at in Exodus, and the fate of Dionysus at Delphi: to be disrobed and dismembered by his successor and, when the pieces were gathered together, to be secretly buried in a chest with the promise of an eventual glorious resurrection.

Stonehenge is now generally dated between 1700 and 1500 BC and regarded as the work of broad-skulled Bronze-Age invaders. The stones are so neatly cut and jointed that one responsible archaeologist, G. F. Kendrick of the British Museum, suggests that they were not placed in position until Belgic times; but the more probable explanation is that the architects had studied in Egypt or Syria.

If then the God of Stonehenge was cousin to Jehovah of Tabor and Zion, one would expect to find the same taboos on the eating or killing of certain animals observed in Palestine and ancient Britain, taboos being far more easily observable than dogma. This proposition is simply tested by inquiring whether the edible but tabooed beasts in Leviticus which are native to both countries were ever tabooed in Britain. There are only two such beasts, the pig and the hare; for the ‘coney’ of Leviticus is not the British coney, or rabbit, but the hyrax, an animal peculiar to Syria and sacred to the Triple Goddess because of its triangular teeth and its litters of three. Both hare and pig were tabooed in ancient Britain: we know of the hare-taboo from Pliny; and that the hare was a royal animal is proved by the story of the hare taken by Boadicea into battle. The Kerry peasants still abominate hare-meat: they say that to eat it is to eat one’s grandmother. The hare was sacred, I suppose, because it is very swift, very prolific – even conceives, Herodotus notes, when already pregnant – and mates openly without embarrassment like the turtle-dove, the dog, the cat or the tattooed Pict. The position of the Hare constellation at the feet of Orion suggests that it was sacred in Pelasgian Greece too. The pig was also sacred in Britain, and the pig-taboo survived until recently in Wales and Scotland; but as in Egypt, and according to Isaiah among the Canaanites of Jerusalem, this taboo was broken once a year at mid-winter with a Pig-feast, the feast of the Boar’s Head. The fish-taboo, partial in Leviticus, was total in Britain and among the Egyptian priesthood and must have been most inconvenient. It survived in parts of Scotland until recent times. The bird-taboos, already mentioned in the lapwing context as common to Britain and Canaan, are numerous. The porpoise (mistranslated ‘badger’) whose skins made the covering for the Ark of the Covenant has always been one of the three royal ‘fish’ of Britain, the others being the whale – the first living thing created by Jehovah, and ‘whale’ includes the narwhal – and the sturgeon, which does not occur in the Jordan but was sacred in Pelasgian Greece and Scythia. According to Aelian, fishermen who caught a sturgeon garlanded themselves and their boats; according to Macrobius it was brought to table crowned with flowers and preceded by a piper.

The Hebrews seem to have derived their Aegean culture, which they shared with the descendants of the Bronze Age invaders of Britain, partly from the Danaans of Tyre and the Sabians of Harran, but mostly (as has already been suggested in Chapter Four) from the Philistines whose vassals they were for some generations; the Philistines, or Puresati, being immigrants from Asia Minor mixed with Greek-speaking Cretans. Those of Gaza brought with them the cult of Zeus Marnas (said to mean ‘virgin-born’ in Cretan) which was also found at Ephesus, and used Aegean writing for some time after the Byblians had adopted Babylonian cuneiform. The Philistine city of Ascalon was said by Xanthus, an early Lydian historian, to have been founded by one Ascalos, uncle to Pelops of Enete on the Southern Black Sea Coast, whose king was Aciamus, a native of the same region. Among the Philistines mentioned in the Bible are Piram and Achish, identifiable with the Trojan and Dardanian names Priam and Anchises; the Dardanians were among the tribes under Hittite leadership that Rameses II defeated at the Battle of Kadesh in 1335 BC. It is probable that the Levitical list of tabooed beasts and birds was taken over by the Israelites from the Philistines: and perhaps written down in the ninth century BC, which is when the Lycian tale of Proetus, Anteia and Bellerophon was inappropriately incorporated in the story of Joseph – Anteia becoming Potiphar’s wife.

Avebury undoubtedly dates from the end of the third millennium BC. It is a circular earthwork enclosing a ring of one hundred posts and these again enclosing two separate temples, all the stones being unhewn and very massive. The temples consist of circles of posts, of which the exact numbers are not known because so many have been removed and because the irregular size of the remainder makes calculation difficult: but there seem to have been about thirty in each case. Within each of these circles was an inner circle of twelve posts: one of them containing a single altar post, the other three.

One hundred months was the number of lunations in the Pelasgian Great Year, which ended with an approximation of lunar and solar time, though a much rougher one than at the close of the nineteen-year cycle. The twin kings each reigned for fifty of these months; which may account for the two temples. If in one temple the posts of the outer circle numbered twenty-nine, and in the other thirty, this would represent months of alternately twenty-nine and thirty days, as in the Athenian calendar – a lunation lasting for 29½ days. On the analogy of the story in Exodus, XXIV, 4 we may assume that the inner circles represented the king and his twelve clan-chieftains, though in one case the central altar has been enlarged to three, perhaps in honour of the king as three-bodied Geryon.

A serpentine avenue enters the Avebury earthwork from the south-east and south-west and encloses two barrows, one of them heaped in the shape of a phallus and the other in the shape of a scrotum. To the south, beyond these, rises Silbury Hill, the largest artificial mound in Europe, covering over five acres, with a flat top of the same diameter as that of New Grange but thirty feet higher. I take Silbury to be the original Spiral Castle of Britain, as New Grange is of Ireland; the oracular shrine of Bran, as New Grange was of The Dagda. Avebury itself was not used for burials.

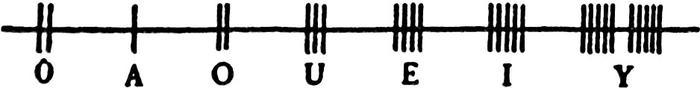

An interesting subject of poetic speculation is: why the Beth-Luis-Nion order of vowels, A.O.U.E.I., which is an order phonetically expressive of the progress and retreat of the year, with U as its climax, was altered in the Cadmean and Latin alphabets to A.E.I.O.U. The clue lies perhaps in the numerical values known to have been assigned in mediaeval Irish literature to the vowels, namely A, one; E, two; I, three; O, four. The numerical value five was assigned to B, the first consonant of the alphabet, which suggests that it originally belonged to U, the remaining vowel, which had no numerical value in this system, but which is the character that expresses the Roman numeral 5. If the vowels are regarded as a seasonal sequence, with A for New Year, O for Spring, U for Summer, E for Autumn and I for Winter, the original numerical values make poetic sense. A had One, as the New Year Goddess of origin; E had Two, as the Autumn Goddess of rutting and combat; I had Three, as the Winter Goddess of Death, pictured as the Three Fates, or the Three Furies, or the three Graeae, or the three-headed Bitch; O had Four, as the Spring Goddess of increase; U had Five, as the Summer Goddess, the leafy centre of the year, the Queen of the whole Pentad. It follows speculatively that the original numerical value of the Pelasgian vowels – A, One; E, Two; I, Three; O, Four; U, Five – suggested to the makers of the Cadmean alphabet that the vowels should be logically arranged in simple arithmetical progression from One to Five.

The numerical values given by the Irish to the remaining letters of the 13-consonant Beth-Luis-Nion are as follows:

B Beth Five L Luis Fourteen N Nion Thirteen F Fearn Eight S Saille Sixteen H Uath No value D Duir Twelve T Tinne Eleven C Coll Nine M Min Six G Gort Ten P Peth Seven R Ruis Fifteen

Exactly why each of these values was assigned to its consonant may De debated at length; but obvious poetic reasons appear in several cases. For example, Nine is the number traditionally associated with Coll, the Hazel, the tree of Wisdom; Twelve is the number traditionally associated with the Oak – the Oak-king has twelve merry men; Fifteen is the number of Ruis, the last month, because it is the fifteenth consonant in the complete alphabet. The numbers Eight and Sixteen for the consonants F and S which follow on the Spring vowel O, or Four, make obvious sense in the context of increase. That H and U are denied numerical values suggests that they were kept out of the sequence for religious reasons. For U was the vowel of the Goddess of Death-in-Life, whom the Sun-god deposed; H was the consonant of Uath, the unlucky, or too holy, May month.

If this number system is of Apollonian origin and belongs to the period when the Irish had come under Greek influence, it is likely that P has been given seven, and L fourteen, and N thirteen as their values, in honour of Apollo. For the assignment of these values to the consonants of his seven-lettered Greek name turns it into a miniature calendar: P, the seven days of the week; LL, the twenty-eight days of a common-law month; N, the thirteen common-law months of the year. The vowel values complete the table: A, the single extra day; O, the four weeks of the common-law month; long O, the two halves of the year: APOLLŌN.

This sort of ingenious play with letters and numerals was characteristic of the Celtic poets. What fun they must have had in their forest colleges! And such restorations of their lore as can still be made from surviving records are more than quaint historical curiosities; they illustrate a poetic method of thought which has not yet outlasted its usefulness, however grossly abused by mystical quacks of the intervening centuries.

Consider, for instance, the Bird-ogham and Colour-ogham in the Book of Ballymote. The composers of these two cyphers had to bear in mind not only the initial of every word but its poetic relation to the already established letter-month. Thus no migratory bird appears in the list of winter months, and samad (sorrel) is not applied to the S-month, as one might have expected, because the sorrel plant goes sorrel-colour only in the late summer. The lists could have been made more nearly poetic if the initials had allowed; thus the Robin would doubtless have led in the year, had he begun with a B, not an S (spidéog), and there was no word for Owl that could be used for the Ng-month when owls are most vocal.

I can best make my point by glossing the cyphers in imitation of the style used in the Book of Ballymote itself, drawing on bardic lore in every case.

*

Day of the Winter Solstice – A – aidhircleóg, lapwing; alad, piebald. Why is the lapwing at the head of the vowels?

Not hard to answer. It is a reminder that the secrets of the Beth-Luis Nion must be hidden by deception and equivocation, as the lapwing hides her eggs. And Piebald is the colour of this mid-winter season when wise men keep to their chimney-corners, which are black with soot inside and outside white with snow; and of the Goddess of Life-in-Death and Death-in-Life, whose prophetic bird is the piebald magpie.

Day of the Spring Equinox – O – odorscrach, cormorant; odhar, dun.

Why is the Cormorant next?

Not hard. This is the season of Lent when, because of the Church’s ban on the eating of meat and the scarcity of other foods, men become Cormorants in their greed for fish. And Dun is the colour of the newly ploughed fields.

Day of the Summer Solstice – U – uiseóg, lark; usgdha, resin-coloured.

Why is the Lark in the central place?

Not hard. At this season the Sun is at his highest point, and the Lark flies singing up to adore him. Because of the heat the trees split and ooze resin, and Resin-coloured is the honey that the heather yields.

Day of the Autumn Equinox – E – ela, whistling swan; erc, rufous-red.

Why is the Whistling Swan in the next place?

Not hard. At this season the Swan and her young prepare for flight. And Rufous-red is the colour of the bracken, and of the Swan’s neck.

Day of the Winter Solstice – I – illait, eaglet; irfind, very white.

Why is the Eaglet in the next place?

Not hard. The Eaglet’s maw is insatiable, like that of Death, whose season this is. And Very White are the bones in his nest, and the snow on the cliff-ledge.

* * *

Dec. 24-Jan. 21 – B – besan, pheasant; bàn, white.

Why is the Pheasant at the head of the consonants?

Not hard. This is the month of which Amergin sang: ‘I am the Stag of Seven Tines’; and as venison is the best flesh that runs, so Pheasant is the best that flies. And White is the colour of this Stag and of this Pheasant.

Jan. 22-Feb. 18 – L – lachu, duck; liath, grey.

Why is the Duck in the next place?

Not hard. This is the month of floods, when Ducks swim over the meadows. And Grey is the colour of flood-water and of rainy skies.

Feb. 19-Mar. 18 – N – naescu, snipe; necht, clear.

Why is the Snipe in the next place?

Not hard. This is the month of the mad March Wind that whirls like a Snipe. And Clear is the colour of Wind.

Mar. 19-Apr. 15 – F – faelinn, gull; flann, crimson.

Why is the Gull in the next place?

Not hard. In this month Gulls congregate on the ploughed fields. And Crimson is the colour of the glain, the magical egg which is found in this month, and of alder-dye, and of the Young Sun struggling through the haze.

Apr. 16-May 13 – S – seg, hawk; sodath, fine-coloured.

Why is the Hawk in the next place?

Not hard. Amergin sang of this month: ‘I am a Hawk on a Cliff.’ And Fine-coloured are its meadows.

The same – SS – stmolach, thrush; sorcha, bright-coloured.

Why is the Thrush joined with the Hawk?

Not hard. The Thrush sings his sweetest in this month. And Bright-coloured are the new leaves.

May 14-Jun. 10. - H – hadaig, night-crow; huath, terrible.

Why is the Night-crow in the next place?

Not hard. This is the month when we refrain from carnal pleasures because of terror, which in Irish is uath, and the Night-crow brings terror. Terrible is its colour.

Jun. 11-July 8 – D – droen, wren; dub, black.

Why is the Wren in the central place?

Not hard. The Oak is the tree of Druids and the king of trees, and the Wren, Drui-én, is the bird of the Druids and the King of all birds. And the Wren is the soul of the Oak. Black is the colour of the Oak when the lightning blasts it, and black the faces of those who leap between the Midsummer fires.

July 9-Aug. 5 – T – truith, starling; temen, dark-grey.

Why is the Starling in the next place?

Not hard. Amergin sang of this month: ‘I am a Spear that roars for blood.’ It is the warrior’s month, and the Starlings’ well-trained army will wheel swiftly and smoothly on a pivot, to the left or to the right, without a word of command or exhortation; thus battles are won, not by single feats and broken ranks. And Dark-grey is the colour of Iron, the warriors’ metal.

Aug. 6-Sept. 2 – C – [corr, crane]; cron, brown.

Why is the Crane in the next place?

Not hard. This is the month of wisdom, and the wisdom of Manannan Mac Lir, namely the Beth-Luis-Nion, was wrapped in Crane-skin. And Brown are the nuts of the Hazel, tree of wisdom.

The same – Q – querc, hen; quiar, mouse-coloured.

Why is the Hen joined with the Crane?

Not hard. When the harvest is carted, and the gleaners have gone, the Hen is turned into the cornfields to fatten on what she can find. And a Mouse-coloured little rival creeps around with her.

Sept. 2-Sept. 30 – M – mintan, titmouse; mbracht, variegated.

Why is the Titmouse in the next place?

Not hard. Amergin sang of this month: ‘I am a Hill of Poetry’; and this is the month of the poet, who is the least easily abashed of men, as the Titmouse is the least easily abashed of birds. Both band together in companies in this month, and go on circuit in search of a liberal hand; and as the Titmouse climbs spirally up a tree, so the Poet also spirals to immortality. And Variegated is the colour of the Titmouse, and of the Master-poet’s dress.

Oct. 1-Oct. 29 – G – géis, mute swan; gorm, blue.

Why is the Mute Swan in the next place?

Not hard. In this month he prepares to follow his companion the Whistling Swan. And Blue is the haze on the hills, Blue the smoke of the burning weed, Blue the skies before the November rain.

Oct. 29-Nov. 25 – Ng – ngéigh, goose; nglas, glass-green. Why is the Goose in the next place?

Not hard. In this month the tame goose is brought in from misty pasture to be cooped and fattened for the mid-winter feast; and the wild goose mourns for him in the misty meadows. And Glassy-green is the wave that thuds against the cliff, a warning that the year must end.

Nov. 26-Dec. 22 ;– R – rócnar, rook; ruadh, blood-red. Why is the Rook in the last place?

Not hard. He wears mourning for the year that dies in this month. And Blood-red are the rags of leaves on the elder-trees, a token of the slaughter.

* * *

The Pheasant was the best available bird for the B-month, bran the raven and bunnan the bittern being better suited to later months of the year. The author of the article on pheasants in the Encyclopaedia Britannica states that pheasants (sacred birds in Greece) are likely to have been indigenous to the British Isles and that the white, or ‘Bohemian’, variety often appears among pheasants of ordinary plumage.

It is possible that the original S-colour was serind, primrose, but that the primrose’s erotic reputation led to its replacement by the euphemism, sodath.

The omission of corr, the Crane, for the C-month is intentional; the contents of the Crane-bag were a close secret and all reference to it was discouraged. And what of Dec. 23rd, the extra day of the year, on which the young King, or Spirit of the Year, was crowned and given eagle’s wings, and which was expressed by the semi-vowel J, written as double I? Its bird was naturally the Eagle, iolar in Irish, which has the right initial. The Irish poets were so chary of mentioning this day that we do not even know what its tree was; yet that they regarded the Eagle as its bird is proved by the use of the diminutive illait, Eaglet, for the letter I: that is to say that if the extra day, double-I, had not been secretly given the cypher-equivalent iolar, there would be no need to express the preceding day, that of the Winter Solstice, namely single I, by illait, Eaglet – for E is not expressed by Cygnet, nor A by Lapwing-chick.

These cyphers were used to mystify and deceive all ordinary people who were not in the secret. For example, if one poet asked another in public: ‘When shall we two meet again?’ he would expect an answer in which elements of several cypher alphabets were used, and which was further disguised by being spelt backwards or put in a foreign language, or both. He might, for instance, be answered in a sentence built up from the Colour, Bird, Tree and Fortress oghams:

When a brown-plumaged rook perches on the fir below the Fortress of Seolae.

That would spell out the Latin CRAS – ‘tomorrow’.

Besides the one hundred and fifty regular cypher-alphabets that the candidate for the ollaveship had to learn, there were countless other tricks for putting the uninitiated off the scent; for example, the use of the letter after, or before, the desired one. Often a synonym was used for the tree-cypher word – ‘the chief overseer of Nimrod’s Tower’ for Beth, birch; ‘activity of bees’ for Saille, willow; ‘pack of wolves’ for Straif, blackthorn, and so on.

In one of the cypher-alphabets, Luis is given as elm, not rowan, because the Irish word for elm, lemh, begins with an L; Tinne is given as elder because the Irish word for elder, trom, begins with a T; similarly, Quert is given as quulend, holly. This trick may account for Ngetal, reed, being so frequently read as broom, the Irish of which is n’gilcach; but there is also a practical poetic reason for the change. The Book of Ballymote gives broom the poetic name of ‘Physicians’ Strength’, presumably because its bitter shoots, being diuretic, were prized as ‘a remedy for surfeits and to all diseases arising therefrom’. (A decoction of broom-flowers was Henry VIII’s favourite medicine.) A medical tree suited the month of November, when the year was dying and the cold winds kept well-to-do people indoors with little diversion but eating and drinking.

1 Homer says that Pharos lies a full day’s sail from the river of Egypt. This has been absurdly taken to mean from the Nile; it can only mean from the River of Egypt (Joshua, XV, 4) the southern boundary of Palestine, a stream well known to Achaean raiders of the thirteenth and twelfth centuries BC.

The same mistake has been made by a mediaeval editor of the Kebra Nagast, the Ethiopian Bible. He has misrepresented the flight of the men who stole the Ark from Jerusalem as miraculous, because they covered the distance between Gaza and the River of Egypt in only one day, whereas the caravan time-table reckoned it a thirteen days’ journey. The absence of prehistoric remains on the island itself suggests that all except the shore was a tree-planted sanctuary of Proteus, oracular hero and giver of winds.

1 Compare the equally mixed list given by Nonnus of Zagreus’s transformations: ‘Zeus in his goat-skin coat, Cronos making rain, an inspired youth, a lion, a horse, a horned snake, a tiger, a bull’. The transformations of Thetis before her marriage with Peleus were, according to various authors from Pindar to Tzetzes, fire, water, wind, a tree, a bird, a tiger, a lion, a serpent, a cuttlefish. The transformations of Tam Lin in the Scottish ballad were snake or newt, bear, lion, red-hot iron and a coal to be quenched in running water. The zoological elements common to these four versions of an original story, namely snake, lion, some other fierce beast (bear, bull, panther, or tiger) suggest a calendar sequence of three seasons corresponding with the Lion, Goat and Serpent of the Carian Chimaera; or the Bull, Lion and Serpent of the Babylonian Sir-rush. If this is so, fire and water would stand for the sun and moon which between them rule the year. It is possible, however, that the animals in Nonnus’s list, bull, lion, tiger, horse and snake, form a Thraco-Libyan calendar of five, not three, seasons.

1 Typhon’s counterpart in the Sanscrit Rig-veda, composed not later than 1300 BC, is Rudra, the prototype of the Hindu Siva, a malignant demon, father of the storm-demons; he is addressed as a ‘ruddy divine boar’.

1 The influence of Pythagoras on the mediaeval mystics of North-Western Europe was a strong one. Bernard of Morlaix (circa 1140) author of the ecstatic poem De Contemptu Mundi, wrote ‘Listen to an experienced man….Trees and stones will teach you more than you can learn from the mouth of a doctor of theology.’ Bernard was born in Brittany of English parents and his verse is in the Irish poetic tradition. His ecstatic vision of the Heavenly Jerusalem is prefaced by the line:

Ad tua munera sit via doctora, Pythagoraea.

‘May our way to your Pythagorean blessings be an auspicious one.’

For he was not a nature worshipper, but held that the mythical qualities of chosen trees and chosen precious stones, as studied by the Pythagoreans, explained the Christian mysteries better than Saint Athanasius had ever been able to do.

1 Clement is very nearly right in another sense, which derives from the suppression in the Phoenician and early Hebrew alphabets of all the vowels, except aleph, occurring in the Greek alphabet with which they are linked. The introduction into Hebrew script of pure vowel signs in the form of dots is ascribed to Ezra who, with Nehemiah, established the New Law about the year 430. It is likely that the vowels had been suppressed at a time when the Holy Name of the deity who presided over the year consisted of vowels only; and the proof that Ezra did not invent them but merely established an inoffensive notation for a sacred series long fixed in oral tradition lies in the order which he used, namely I.Ē.E.U.O.A.OU.Ō. This is the Palamedan I.E.U.O.A. with the addition of three extra vowels to bring the number up to eight, the mystic numeral of increase. Since the dots with which he chose to represent them were not part of the alphabet and had no validity except when attached to consonants, they could be used without offence. Nevertheless, it is remarkable that the consonants which compose the Tetragrammaton, namely yod, he and vav may cease to carry consonantal force when they have vowel signs attached to them; so that JHWH could be sounded IAŌOUĀ. This is a peculiarity that no other Hebrew consonant has, except ain, and ain not in all dialects of Hebrew. Clement got the last vowel wrong, E for Ā, perhaps because he knew that the letter H is known as He in Hebrew.

2 42 is the number of the children devoured by Elisha’s she-bears. This is apparently an iconotropic myth derived from a sacred picture of the Libyo-Thraco-Pelasgian ‘Brauronia’ ritual. The two she-bears were girls dressed in yellow dresses who pretended to be bears and rushed savagely at the boys who attended the festival. The ritual was in honour of Artemis Callisto, the Moon as Bear-Goddess, and since a goat was sacrificed seems to belong to the Midsummer festivities. 42 is the number of days from the beginning of the H month, which is the preparation for the midsummer marriage and death-orgy, to Midsummer Day. 42 is also the number of infernal jurymen who judged Osiris: the days between his midsummer death and the end of the T month, when he reached Calypso’s isle, though this is obscured in the priestly Book of the Dead. According to Clement of Alexandria there were forty-two books of Hermetic mysteries.

1 The number occurs also in two royal brooches – ‘king’s wheels’ – found in 1945 in a Bronze Age ‘Iberian’ burial at Lluch in Majorca, the seat of a Black Virgin cult, and dated about 1500 BC. The first is a disc of seven inches in diameter, made for pinning on a cloak and embossed with a nineteen-rayed sun. This sun is enclosed by two bands, the outer one containing thirteen separated leaves, of five different kinds, perhaps representing wild olive, alder, prickly-oak, ivy and rosemary, some turned clockwise, some counter-clockwise, and all but two of them with buds or rudimentary flowers joined to them half-way up their stalks. The inner band contains five roundels at regular intervals, the spaces between the roundels filled up with pairs of leaves of the same sort as those in the outer ring, except that the alder is not represented. The formula is: thirteen months, a pentad of goddesses-of-the-year, a nineteen-year reign.