VI

THE HAUNTER OF THE GULCHES

Gordon staggered to his feet, empty handed, glaring in hypnotic fascination at the black ring that was the rifle muzzle trained full upon him. Behind it a bearded face froze in a yellow-fanged grin of murder.

Then a hand dragged aside the barrel as the wall was lined with turbaned heads. The man who had struck up the rifle barrel laughed and pointed down the ravine, and the man with the gun hesitated, and then grinned malevolently. Gordon scowled up at the row of bearded faces that looked down at him, all grinning as if at a grim jest. Some laughed derisively, and others shouted replies to questions hurled by some unseen party.

Gordon stood motionless, unable to comprehend the attitude of his enemies. When he rose to face that rifle he had expected nothing but an instant blast of lead; but the warriors had not fired, and seemingly had no intention of firing.

Another countenance appeared above him — a blood-stained face, adorned with a black mustache. Konaszevski was rather pale under his dark skin, and his expression was no less malignant.

“Out of the frying pan into the fire, as you damned Americans say,” he laughed viciously. “Well, I had other plans for you” — he dabbed with a bit of silk at the cut on his chin — “but this suits me well enough. I leave you to your meditations. You are no longer important enough to take up my time, and I certainly have no intention of allowing you to be put out of misery with a merciful rifle-shot. Farewell, dead man!”

And with a brusk word to his followers, he disappeared. The turbans vanished from the parapet like apples rolled off a wall, and Gordon stood alone except for the dead man sprawling near his feet.

Gordon frowned as he looked suspiciously about him. He knew that the southern end of the plateau was cut up into a network of ravines, and obviously he was in one which ran out of that network to the south of the palace. It was a straight gulch, like a giant knife-cut, thirty feet in width, which ran out of a maze of gullies straight toward the city, ceasing abruptly at a sheer cliff of solid stone below the garden wall from which he had fallen. This cliff was fifteen feet in height and too smooth to be wholly the work of nature.

Ten feet from the end-wall, the ravine deepened abruptly, the rocky floor falling away some five feet. He stood on a kind of natural shelf at the end of the ravine. The side-walls were sheer, showing evidences of having been smoothed by tools. Across the rim of the wall at the end, and for fifteen feet on each side, ran a strip of iron with short razor-edged blades slanting down. They had not cut him as he fell over them, but anyone trying to climb the wall, even if he reached the rim by some miracle, would be gored to pieces trying to swarm up over them. The strips on the side walls overreached the edge of the shelf below, and beyond that point the walls were more than twenty feet in height. Gordon was in a prison, partly natural, partly man-made.

Looking down the ravine he saw that it widened and broke into a tangle of smaller gulches, separated by ridges of solid stone, beyond and above which he saw the gaunt bulk of the mountain looming up. The other end of the ravine was not blocked in any way, but he knew that his captors would not use so much care in safeguarding one end of his prison while allowing some avenue of escape at the other. But it was not his nature to resign himself to whatever fate they had planned for him. Obviously they thought they had him safely trapped; but other men had thought that before.

He pulled the knife out of the Kurd’s carcass, wiped off the blood and went down the ravine.

A hundred yards from the city-end, he came to the mouths of the smaller ravines, selected one at random, and immediately found himself in a nightmarish labyrinth. Channels hollowed in the almost solid rock meandered bafflingly though a crumbling waste of stone. Mostly they ran roughly north and south, but they merged with one another, split apart, and looped in crisscross chaos. Most of them seemed to begin without reason and to go nowhere. He was forever coming to the ends of blind alleys which, if he surmounted them, it was only to descend into another equally confusing branch of the insane network.

Sliding down a gaunt ridge his heel crunched something that broke with a dry crack. He had stepped upon the dried rib-bones of a headless skeleton. A few yards away lay the skull, crushed and splintered. He began to stumble upon similar grisly relics with appalling frequency. Each skeleton showed broken bones and a smashed skull. The action of the elements could not have had that destructive an effect. He went more warily, narrowly eyeing every spur of rock or shadowed recess. But he saw no tracks in the few sandy places where a track would have shown that would indicate the presence of any of the large carnivora. In one such place he did indeed come upon a partially effaced track, but it was not the spoor of a leopard, bear or tiger. It looked more like the print of a bare, misshapen human foot. And the bones had not been gnawed as they would have been in the case of a man-eater. They showed no tooth-marks; they seemed simply to have been crushed and broken, as an incredibly powerful man might have broken them. But once he came upon a rough out-jut of rock to which clung strands of coarse grey hair that might have been rubbed off against the stone, and here and there an unpleasant rank odor which he could not define hung in the cave-like recesses beneath the ridges where a beast — or man, or demon! — might conceivably curl up and sleep.

Baffled and balked in his efforts to steer a straight course through the stony maze, he scrambled up a weathered ridge which looked to be higher than most, and crouching on its sharp angle, stared out over the nightmarish waste. His view was limited except to the north, but the glimpses he had of sheer cliffs rising above the spurs and ridges to east, west and south, made him believe that they formed parts of a continuous wall which enclosed the tangle of gullies. To the north this wall was split by the ravine which ran to the outer palace garden.

Presently the nature of the labyrinth became evident. At one time or another a section of that part of the plateau which lay between the site of the present city and the mountain had sunk, leaving a great bowl-like depression, and the surface of the depression had been cut up into gullies by the action of the elements over an immense period of time. There was no use wasting time wandering about in the midst of the gulches. His problem was to make his way to the cliffs that hemmed in the corrugated bowl, and skirt them, to find if there was any way to surmount them. Looking southward he believed he could trace the route of a ravine which was more continuous than the others, and which ran in a more or less direct route to the base of the mountain whose sheer wall hung over the bowl. He also saw that to reach this ravine he would save time by returning to the gulch below the city wall and following another one of the ravines which debouched into it, instead of scrambling over a score or so of knife-edged ridges which lay between him and the gully he wished to reach.

With this purpose in mind he climbed down the ridge and retraced his steps. The sun was swinging low as he re-entered the mouth of the outer ravine, and started toward the gulch he believed would lead him to his objective. He glanced idly toward the cliff at the other end of the wider ravine — and stopped dead in his tracks. The body still lay on the shelf — but it was not lying in the same position in which he had left it — it did not seem so bulky, and the garments looked different. An instant later he was racing along the ravine, springing up on the shelf, bending over the motionless figure. The Kurd he had killed was gone; the man who lay there was Lal Singh!

There was a great lump, clotted with blood, on the back of his head, but the Sikh was not dead. Even as Gordon lifted his head, he blinked dazedly, lifted a hand to his wound, and stared blankly at Gordon.

“Sahib! What has happened? Are we dead and in Hell?”

“In Hell, perhaps, but not dead. Do you have any idea how you came here?”

The Sikh sat up dizzily, holding his head in his hands. He stared about him in amazement.

“Where are we?”

“In a ravine behind the palace. Do you remember being thrown in here?”

“No, sahib. I remember the fight in the palace; nothing thereafter. As I waited in the darkness on the hidden stair, the girl Azizun came in haste and said you had been confronted by a man who knew you. She led me to the chamber adjoining that one in which you were fighting, and I used your pistol to some advantage, as I remember. I was running to the outer door to join you — then something happened. I do not know. I do not remember anything.”

“A fedaui hiding among the tapestries knocked you in the head,” grunted Gordon. “Doubtless saw you enter the chamber and sneaked in after you and hid in a secret alcove. The palace seems to be full of them. He slugged you and pulled a rope to open a trap in the floor for you to fall through. I got over a garden wall and fell into this infernal ravine, with a dead Kurd. Evidently while I was exploring down the ravine they took his body out and threw you down here.

“Wait a minute, though! You weren’t thrown. You’d have broken bones, probably a broken neck. They might have come down on ladders, and hoisted the Kurd up, but they certainly wouldn’t take the trouble to ease you down gently. There’s only one alternative. They shoved you through some kind of door in the cliff somewhere.”

A few minutes careful searching disclosed the door whose existence he suspected. The thin cracks which advertised its presence would have escaped the casual glance. The door on that side was of the same material as the cliff, and fitted perfectly. It did not yield a particle as both men thrust powerfully upon it.

Gordon marshalled his scraps of knowledge concerning the architecture of the palace, and his eyes narrowed at the conclusion he reached, though he said nothing to the Sikh. He believed that they were looking on the outer side of that curiously decorated door beneath the palace against which Azizun had warned him. The door to Hell! Then he and Lal Singh were in “Hell,” and those splintered bones he had seen lent a sinister confirmation to the legend of a djinn which devoured humans — though he did not believe the owners of those bones had been literally devoured. But something inimical to human beings haunted that maze of ravines. He abandoned all thought of breaking in the door, as he remembered its heavy, metal-bound material and powerful bolts. It would take a company of men with a battering ram to shake that door.

He turned and looked down the gully toward the mysterious labyrinth, wondering what skulking horror its mazes hid. The sun had not yet set, but it was hidden from the gulches; the ravine was full of shadows, though visibility had not yet been appreciably affected.

“The walls are high here,” muttered the Sikh, pressing his hands to his throbbing head. “But they are higher further along the ravine. If you stood on my shoulders and leaped —”

“I’d cut my hands off on those blades.”

“Oh!” The cobwebs were clearing from the Sikh’s brain. “I did not notice. What shall we do, then?”

“Cross that maze of gulches and see what lies beyond it. You know nothing of what became of Azizun, of course?”

“She was running ahead of me until we came to the chamber whence I fired your pistol. I supposed she followed me as I rushed past her into that chamber. But I did not see after I entered it.”

“The fedaui who slugged you must have grabbed her and shoved her into some secret compartment,” growled Gordon, veins swelling slightly on his neck. “Damn them, they’ll torture and kill her — we’ve got to get out of here. Come on.”

A mystical blue twilight hovered over the gulches as Lal Singh and Gordon entered the labyrinth. Threading among winding channels they came out into a slightly wider gully which Gordon believed was the one he had seen from the ridge, and which ran to the south wall of the bowl. But they had not gone fifty yards when it split on a sharp-edged spur into two narrower gorges. This division had not been visible from the ridge, and Gordon did not know which branch to follow. He decided that the two branches merely ran past the narrow spur, one on each side, and joined again further on. When he spoke his belief to the Sikh, Lal Singh said: “Yet one may be but a blind alley, instead. You take the right branch, and I will take the left, and we will explore them separately.”

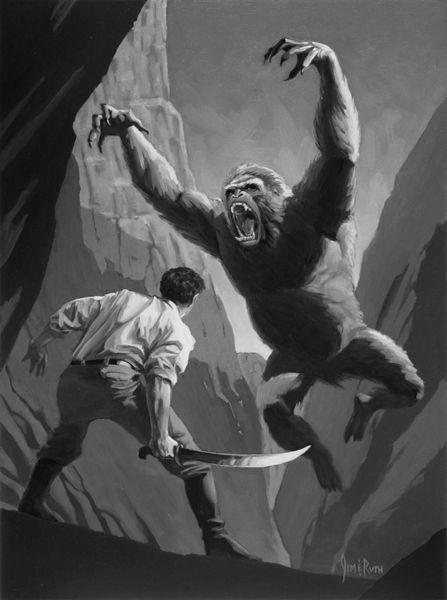

And before Gordon could stop him, he was off, half-running down the left hand ravine, and passed out of sight almost instantly. Gordon started to call him back, then stiffened without shouting. Ahead of him, on the right, the mouth of a yet narrower ravine opened into the right-hand gorge, a well of blue shadows. And in that well something moved. Gordon tensed rigidly, staring unbelievingly at the monstrous man-like being which stood in the twilight before him.

It was like the embodied spirit of this nightmare country, a ghoulish incarnation of a terrible legend, clad in flesh and bone and blood.

The creature was a giant ape, as tall on its gnarled legs as a gorilla. But the shaggy hair which covered it was of a strange ashy grey, longer and thicker than the hair on a gorilla. Its feet and hands were more man-like, the great toes and thumbs more like those of the human than of the anthropoid. It was no arboreal creature, but a beast bred on great plains and barren mountains. The face was gorilloid in general appearance, but the nose-bridge was more pronounced, the jaw less bestial, though there was no chin. But its man-like features merely served to increase the dreadfulness of its aspect, and the intelligence which gleamed from its small red eyes was wholly malignant.

Gordon knew it for what it was: the monster whose existence even he had refused to credit, the beast named in myth and legend of the north — the Snow-Ape, the Desert Man of forbidden Mongolia. He had heard rumors of its existence many times, in wild tales drifting down from a lost, bleak plateau-country of the Gobi never explored by white men. Tribesmen had sworn to the stories of a man-like beast which had dwelt there since time immemorial, adapted to the famine and bitter chill of the northern uplands. But Gordon had never seen a man who could prove he had seen one of the brutes.

But here was indisputable proof. How the nomads who served Othman had managed to bring the monster from Mongolia Gordon could not guess, but here was the djinn which haunted the ravines behind mysterious Shalizahr.

All this flashed through Gordon’s mind in the moment the two stood facing each other, man and beast, in menacing tenseness. Then the rocky walls of the ravine echoed to the ape’s deep sullen roar as it charged, low-hanging arms swinging wide, yellow fangs bared and dripping.

Gordon did not shout to his companion. Lal Singh was unarmed. Nor did he try to flee. He waited, poised on the balls of his feet, craft and long knife pitted against the brute strength of the mighty ape.

The monster’s victims had been given to it broken and shattered from the torture that only an Oriental knows how to inflict. The semi-human spark in its brain which set it apart from the true beasts had found a horrible exultation in the death agonies of its prey. This man was only another weak creature to be torn and twisted and dismembered, even though he stood upright and held a gleaming thing in his hand.

Gordon, as he faced that onrushing death, knew his only chance was to keep out of the grip of those huge arms which could crush him in an instant. The monster was clumsy but swift, as it rolled over the ground, and it hurled itself through the air for the last few feet in a giant grotesque spring. Not until it was looming over him, the great arms closing upon him, did Gordon move, and then his shift would have shamed a striking catamount.

The talon-like nails only shredded his shirt as he sprang clear, slashing as he sprang, and a hideous scream ripped the echoes shuddering through the ridges; the ape’s arm fell to the ground, shorn away at the elbow. With blood spouting from the severed stump the brute whirled and rushed again, and this time its desperate lunge was too lightning-quick for any human thews wholly to avoid.

Gordon evaded the disembowelling sweep of the great misshapen hand with its thick black nails, but the massive shoulder struck him and knocked him staggering. He was carried to the wall with the lunging brute, but even as he was swept backward he drove his knife to the hilt in the great belly and ripped up in the desperation of what he believed was his dying stroke.

They crashed together into the wall, and the ape’s great arm hooked terribly about Gordon’s straining frame; the roar of the beast deafened him as the foaming jaws gaped above his head — then they snapped spasmodically in empty air as a great shudder shook the mighty body. A frightful convulsion hurled the American clear, and he bounded up to see the ape thrashing in its death throes at the foot of the wall. His desperate upward rip had disembowelled it and the tearing blade had ploughed up through muscle and bone to find the fierce heart of the anthropoid.

Gordon’s corded thews were quivering as if from a long-sustained strain. His iron-hard frame had resisted the terrible strength of the ape long enough to permit him to come alive out of that awful grapple that would have torn a weaker man to pieces; but the terrific exertion had shaken even him. Shirt and undershirt had been ripped from him and those horny-taloned fingers had left bloody marks deep-grooved across his back. He was smeared and stained with blood, his own and the ape’s.

“El Borak! El Borak!” It was Lal Singh’s voice lifted in frenzy, and the Sikh burst out of the left-hand ravine, a rock in each hand, and his bearded face livid.

His eyes blazed at the sight of the ghastly thing at the foot of the wall; then he had seized Gordon in a desperate grasp.

“Sahib! Are you slain? You are covered with blood! Where are your wounds?”

“In the ape’s belly,” grunted Gordon, twisting free. Emotional display embarrassed him. “It’s his blood, not mine.”

Lal Singh sighed with gusty relief, and turned to stare wide-eyed at the dead monster.

“What a blow! You ripped him wide open so his guts fell out! Not ten men now alive in the world could strike such a blow. It is the djinn of which the girl warned us! And an ape! The beast the Mongols call the Desert Man.”

“Yes. I never believed the tales about them before. Scientific expeditions have tried to find them, but the natives in that part of the Gobi always ran the white men out.”

“Perhaps there are others,” suggested Lal Singh, peering sharply about in the gathering dusk. “It will soon be dark. It will not be well to meet such a fiend in these dark ravines after nightfall.”

“I don’t think. His roars could have been heard all through these gulches. If there had been another, it would have come to his aid, or sounded an answering roar, at least.”

“I heard the bellowing,” said Lal Singh fervently. “The sound turned my blood to ice, for I believed it was in truth a djinn such as the superstitious Moslems speak of. I did not expect to find you alive.”

Gordon spat, aware of thirst.

“Well, let’s get moving. We’ve rid the ravines of their haunter, but we can still die of hunger and thirst if we don’t get out. Come on.”

Dusk masked the gullies and hung over the ridges, as they moved off down the right-hand ravine. Forty yards further on the left-hand branch ran back into its brother, as Gordon had believed to be the case. As they advanced, the walls were more thickly pitted with cave-like lairs, in which the rank scent of the ape hung strong. Gordon scowled and Lal Singh swore at the numbers of skeletons which littered the gulch, which evidently had been the monster’s favorite stamping ground. Most of them were of women, and as Gordon viewed those pitiful remnants, a relentless and merciless rage grew redly in his brain. All that was violent in his nature, ordinarily held under iron control, was roused to ferocious wakefulness by the realization of the horror and agony those helpless women had suffered, and in his own soul he sealed the doom of Shalizahr and the human fiends who ruled it. It was not his nature to swear oaths or vow loud vows. He did not speak his mind even to Lal Singh; but his intention to wipe out that nest of vultures in the interests of the world at large took on the tinge of a personal blood-feud, and his determination fixed like iron never to leave the plateau until he had looked upon the dead bodies of Ivan Konaszevski and the Shaykh Al Jebal.

The loom of the mountain was now above them, in tiers of giant cliffs, rising precipitously above the rim of the bowl which enclosed the sunken labyrinth. The ravine they were following ran into a cleft in the wall of this bowl, beneath the mountain. It became a tunnel-like cavern, receding under the mountain like a well of blackness. There was despair in the Sikh’s voice as he spoke.

“Sahib, it is a prison from which there is no escape. We can not climb the rim that hems in this depression of gulches. And this cave —”

“Wait!” Gordon’s iron fingers bit into the Sikh’s arm in sudden excitement. They were standing in utter darkness, some yards inside the cave-mouth. He had glimpsed something far down that black tunnel — something that shone like a firefly. But it was steady, not intermittent. It cut through the blackness like a stationary spark of light.

“Come on!” Releasing the Sikh’s arm Gordon hurried down the cavern, chancing a plunge into a pit or a meeting in the dark with some grim denizen of the underworld. He knew what he saw was a star, shining through some cleft in the mountain wall.

As they advanced a faint light illuminated the darkness ahead of them, and presently they saw the cave ended at a blank wall; but in that wall, some ten feet from the floor, there was hole and through it they saw the star and a bit of velvet night-sky. Without a word the Sikh bent his back, gripping his legs above the knees to brace himself, and Gordon climbed onto his shoulders and stood upright, his fingers grasping the rim of the roughly circular cleft. It was four or five feet long, and just big enough for a man to squeeze through. The ape might conceivably have reached it, but he could not have forced his great shoulders through it. Gordon did not believe the masters of Shalizahr knew of that opening.

He wriggled to the other end of the tunnel-like cleft, and peered over the rim. He was looking down on the western flank of the mountain. The hole was a crevice in a cliff which sloped down for three hundred feet, broken by rocks and ledges. He could not see the plateau; a marching row of broken pinnacles rose gauntly between it and his point of vantage. Crawling back, he dropped down inside the cave beside the eager Sikh.

“Is it a way of escape, sahib?”

“For you. Lal Singh, you’ve got to go and meet Yar Ali Khan and the Ghilzai. I’m gambling on the chance that he reached Khor and will be back at the outer gates of Shalizahr by sunrise tomorrow. According to my estimate there are at least five hundred fighting men in Shalizahr. Baber Khan’s three hundred can’t take the city in a direct attack. They might surprize the guard at the cleft as I did, might even force their way up the Stair. But to cross the plateau on foot, in the teeth of five hundred rifles under Ivan’s command, would be suicide.

“You’ve got to meet them before they get to the plateau. I think you can do it. When you’ve squirmed through this hole and climbed down the slope outside, you’ll be outside the ring of crags which surrounds Shalizahr. The only way through those crags is by the cleft through which we came to the plateau. The Ghilzai will come through that cleft. You’ll have to stop them in the canyon the Assassins call the Gorge of the Kings, if at all. To get there you’ll have to skirt the ring of crags, and follow around their western slopes until you hit the canyon. It’ll be rough going, and you may have trouble getting down the cliffs that wall the canyon when you get there. But you’ll have all night to make the trip in.”

“And you, sahib?”

“I’m coming to that. If you get to the Gorge of the Kings before the Ghilzai come, hide and wait for them. If they’ve already passed through the cleft — you can read their sign — follow them as fast as you can. In any event, see that Baber Khan follows this plan of action: let him take fifty men and make a demonstration against the Stair. If they can climb the ramps and take cover in the boulders at the head of the Stair, so much the better. If not, let them climb the surrounding crags and start shooting at everything in sight on the plateau. The idea is to create a diversion to attract the attention of the men in the city, and if possible to draw them all to the Stair. If they advance down into the canyon, let Baber Khan and his fifty retreat among the crags.

“Meanwhile, do you and Yar Ali Khan lead the rest of the Ghilzai back the way you’ll traverse in reaching the Gorge of Kings. Bring them up that slope and through this cleft and down that ravine where the door in the rock opens into the dungeons under the palace.”

“But what of you?”

“My part will be to open that door for you — from the inside.”

“But this is madness! You can not get back into the city; and if you did, they would flay you alive. But you can not open that door.”

“Another will open it for me. That ape didn’t eat the wretches thrown to him. He wasn’t carnivorous. No ape is. He had to be fed vegetables, or nuts, or roots or something. You saw a man open that door and throw something out. Undoubtedly, it was a bundle of food. They fed it through that door, and they must have fed it regularly. It wasn’t gaunt, by any means.

“I’m gambling that door will be opened tonight. When it opens, I’m going through it. I’ve got to. They’ve got Azizun somewhere in that hellish palace, and only Allah knows what they’re doing to her. Now you go in a hurry. When you get back into the bowl with the Ghilzai, hide them among the gulches and come down the ravine to the door with three or four men. Tap a few times on it with your rifle-butt. That door will be opened whether I’m alive or dead — if I have to come back from Hell and open it. Once in the palace, we’ll make a shambles of Othman and his dogs.”

The Sikh lifted his hand in protest and opened his mouth — then shrugged his shoulders fatalistically and silently acquiesced.

Gordon squatted and the Sikh climbed on his shoulders and stood upright, steadying himself with outstretched hands against the wall. Gordon gripped his ankles with both hands and rose to an upright posture without the aid of his arms, using only his leg muscles to lift himself and the tall man on his shoulders — a feat impossible to most men besides trained acrobats.

In the cleft Lal Singh turned and looked down at his friend.

“What if none comes with food for the beast, and the door is not opened tonight?”

“Then I’ll cut off the ape’s head and throw it over the wall. They’ll open the door then, to see why I’m still alive. Maybe they’ll take me into the palace to torture me when they learn I’ve killed their goblin. Once let me get in there, even if in chains, and I’ll find a way to trick them.

“Here!” Gordon tossed up the long knife. “You may need this.”

“But if you wish to cut off the ape’s head —”

“I’ll saw it off with a sliver of sharp rock — or gnaw it off with my teeth! Get going, confound it!”

“The gods protect you,” muttered the Sikh, and vanished. Gordon heard a clawing and scrambling that marked his course through the cleft, and then pebbles began rattling down the sloping cliff outside.