Well they’ve been so long

on Lonely Street they ain’t ever going to look back.

—Elvis Presley

TWO MONTHS EARLIER

My mother, Charlie, and I stood in a line, looking down at the small brass marker in the ground. The overly solicitous funeral director had shown us the plot, then backed away, telling us he’d be nearby if we needed anything.

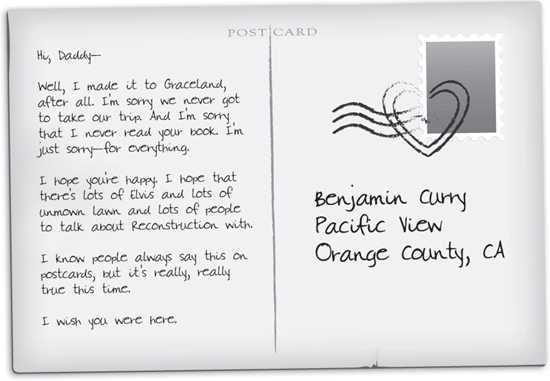

I couldn’t think of anything we’d need that he could provide, so I’d just glared at him while he talked, then felt bad about it as he left and waited a respectful distance away. The cemetery, Pacific View, was beautiful—we’d been informed on our drive up to the plot that John Wayne was buried there. But we were in Orange County, an hour and a half away from Raven Rock. And I didn’t like to think of my father alone out here, so far away from home.

I didn’t want to think about him at all, and it seemed impossible to me, as I looked down at the small brass marker—BENJAMIN CURRY. BELOVED HUSBAND, FATHER, AND EDUCATOR—that my father was in there. He had always been too tall for things, complaining about tiny movie theater and airplane seats. How could he fit below a marker the size of my hand? How was that possible? And as I looked at my mother and my brother, both staring down at the ground, nobody saying anything, the whole thing just felt wrong. We shouldn’t have been putting him in the cold, dark ground. We should have scattered his ashes in the Jungle Room or over the fields of Gettysburg or even on our lawn he loved so much. He shouldn’t have been in Orange County, surrounded by strangers, most of whom were probably old and had died peacefully of natural causes.

My mother cleared her throat, then looked at Charlie and me. I looked back at her, not wanting to, telling myself that I’d learned by now, but still waiting for her to say something. Or put her arms around us. Just to somehow make this better. But she turned and walked away, heading toward the funeral director. I looked at Charlie, who was still staring down at the ground. His eyes were red, and I actually had no idea what the cause was today. We were standing fairly close—I could have extended my arm and touched him—but it felt like we were miles apart. Why weren’t we talking about this? Why weren’t we reaching out to each other?

Charlie left as well, heading toward my mother, leaving me alone. Alone with the small piece of ground that held what was left of my father, I reached into my pocket and took out what I’d brought him. When I’d been in the 7-Eleven that morning, looking down at the candy display, I’d suddenly panicked, because I couldn’t remember what his favorite flavors were. Why hadn’t I paid more attention? Why hadn’t I realized that one day he wouldn’t be there to ask?

I’d finally gone with Butter Rum and Wint-O-Green. I took them out and placed them on top of the marker, where they rolled back until they hit the raised B of his name and stopped. It had always been my job to give him Life Savers. And now this was the only way I could do it. I looked at the candy, knowing it would be taken away, uneaten, when the flowers were thrown away every week.

Then I turned away too, leaving him all alone.