KIM

WILKINS

THE

RESURRECTIONISTS

For Elaine and Stella:

angels earthly and heavenly

In the bleak midwinter, frosty wind made moan, Earth stood hard as iron, water like a stone; Snow had fallen, snow on snow, snow on snow, In the bleak midwinter, long ago.

Christina Rossetti

The dead have exhausted their power of deceiving. Horace Walpole

Contents

Dedication

Epigraphs

In the bleak midwinter, frosty wind…

The dead have exhausted…

Prologue

The smell of decay and the cold…

Chapters 1

On the first Thursday in November…

2

Maisie felt as though she had been traveling…

3

Though he was loath to admit it, Reverend Fowler …

4

Adrian was a good singer and he knew it…

5

Maisie found herself anxiously peering…

6

Tuesday at around two p.m. Maisie…

7

And so, little book, prepare to become…

8

Maisie placed the little book in her lap…

9

Though far from being a blissful New Bride…

10

Maisie sat back to contemplate what…

11

Damp hair trailing about her face, Maisie…

12

Maisie and Cathy sat in a cramped corner…

13

Charlotte lies next to me, bleeding…

14

Yes, it is true I have not written…

15

My husband is still ill, and I begin to despair…

16

Maisie put the diary carefully aside…

17

The train slid into King’s Cross station…

18

Maisie tried not to worry about wax dripping…

19

“Morning, Reverend. I’ve got that number…

20

With the fire at her back, with Tabby curled up…

21

Gloomy morning didn’t dawn at all.

22

What a relief not to have to think of spells…

23

Adrian put off calling Janet as long as he could. 24

When the bell began to toll Maisie realised…

25

Virgil is much improved. His colour…

26

Another long silence from me…

27

***** too cold to leave the house.

28

Maisie bit her lip and blinked back tears.

29

Dawn was still a half hour…

30

A bus was leaving for Whitby just as Maisie…

31

She couldn’t keep her hands off him.

32

The heat of the afternoon hit Adrian …

33

Because I cannot starve, because I have a child…

34

A week in relative Comfort has made me lazy…

35

I wonder, do houses have memories?

36

Maisie stopped reading and looked up.

37

Mila left in a flurry of apologies and promises…

38

The beach was dirty with sludgy…

39

Maisie dreaded leaving behind the warm…

40

She slept through Sunday and most of Monday. Acknowledgments

From the author

Credits

Copyright page

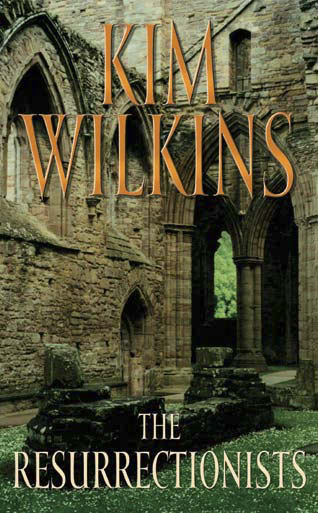

Front Cover

About PerfectBound

PROLOGUE

SEPTEMBER

The smell of decay and the cold caress of a shadow, and the old woman knew how this would end. After all, she had read the story. She had never been afraid of crossing over: death was life’s last great adventure, and at eighty-three years of age she’d be foolish to harbour fears still. But could she make the crossing if she died like this?

She gasped for air, her heart thudding in her chest. Bang, bang, bang. Her joints, worn and stiff with years, could not hold out for much longer. The ground was uneven and rough beneath her bare feet, her toes were frozen, her thick dress only dulled the edge of the biting autumn wind. The bells on the church were ringing Sunday night’s service out. If she left the world now, then nobody could stop him. Nobody would know.

“Please,” the old woman cried, panting, hands on her knees, running no more. Her back curved over, open to attack. “Please.” She didn’t know why she was saying please. Please meant nothing. Especially not to this kind of being. She tried to gather herself, but the agony of ripped flesh raced up her back in one hard, hot stroke. Dark arms enveloped her, choking her. Her blood felt hot as it ran over her legs. She did not struggle, using her energy instead to project herself out of her body as she had done so many times in her practice. Don’t feel the pain. Die quietly, peacefully. Don’t look at it. But curiosity was burning in her. The ache of ruptured skin pulled her back and kept her pinned inside. Stiff, hard fingers crushed into each arm, turning her around. She dropped her head, closed her eyes. Felt life ebbing from her. Go across, Sybill, she told herself. Jump the chasm. Don’t look at it. Don’t die in fear. Resist, resist. Slowly she lifted her head, opening her eyes. Her scream could be heard as far away as Solgreve Abbey.

In a warm dark bedroom, oceans away, the old woman’s granddaughter awoke with a sense of dread, billowing nausea churning deep in her stomach. She barely made it to the bathroom in time. Fifteen minutes of violent retching mercifully blurred the memory of the dream. All she could recall later, in the solicitous light of dawn, was that she had touched a nightmare, and that the nightmare had somehow reached out to touch her in return.

CHAPTER ONE

On the first Thursday in November, Maisie Fielding watched as her boyfriend murdered a woman in a fit of jealous passion, but her mind was elsewhere. Verdi’s score rolled on around her, Desdemona – a chunky soprano at least fifteen years older than her leading man – died with all due drama, and the audience gradually fell in love with the handsome young tenor who had only been Otello’s understudy until three o’clock that afternoon. It was the biggest break of Adrian’s career, but Maisie was preoccupied with her lie.

And it was a big lie. It involved imaginary consultations with imaginary doctors, feigned tears and feigned winces of pain, and a reluctant acceptance of the fictional diagnosis – three months’ break from playing the cello, for fear of permanent injury. Her mother had pressed her perfectly formed pianist’s hand to her perfectly glossy black hair – still not a streak of grey – and moaned, yes, moaned, in distress. Your career, Maisie, your future.

But damn it, she had been in an arranged marriage with the cello since she was four. It was time for a trial separation.

She glanced over at her mother who sat next to her, eyes soft with tears of pride. She loved Adrian. Everybody loved Adrian, he was eminently lovable. It was entirely her mother’s own fault that she got lies instead of the truth. There was no question of Maisie approaching her and confessing that she needed a break from the orchestra, to try something different, to be someone different. Nobody ever argued with Janet Fielding, or at least, nobody ever won.

As if she knew her daughter was thinking of her, Janet reached out and touched Maisie’s right hand, the injured hand. Her caress was gentle, almost reverent. Maisie realised she would never know for sure if the touch was meant for her, or just for the body part. She turned her hand over and squeezed her mother’s in return. Everybody on stage was soon dead or lamenting a death, and the final curtain fell to rapturous applause.

“I think Adrian’s going to be a star,” Janet said, raising her voice over the din.

Maisie smiled. “He always has been. Now

everybody else will know.”

They met Adrian, wig-free and scrubbed of his make-up, one hour later at a cafe on Boundary Street. In the meantime, while they waited, Maisie had carefully steered conversation away from the lie, encouraging her mother instead to reminisce over a bottomless pot of Earl Grey tea. Past glory was always a favourite topic of conversation for Janet Fielding. When Adrian walked into the room, blond hair glinting like a halo, everyone – men and women –

looked up and appraised him. He had that kind of presence, and Maisie wondered for the zillionth time what he had ever seen in a neurotic, black-haired, black-eyed girl with bitten fingernails and too-straight eyebrows. She hoped it wasn’t just her pedigree –

Maisie’s mother had been a renowned concert pianist before her surprise pregnancy at forty-two. Her father was a conductor with an international reputation. He had rarely been at home through most of her childhood. Now nearly seventy and semi-retired, Roland Fielding was the one who had introduced Maisie to Adrian four years ago.

Janet took up nearly half in hour in euphoric praise of Adrian’s performance, and all the while he sat there beaming with the kind of self-pleasure which borders on vanity. But finally, as Maisie knew it would, the conversation turned elsewhere.

“I expect you haven’t heard Maisie’s bad news yet,” Janet said, her mouth turning down in faint disapproval.

“Maisie?” Adrian turned to her with steady grey eyes.

“Ah . . . yes. The final specialist’s report came back this afternoon. I have to take a break, at least three months.”

Adrian nodded his understanding. “I thought a break might be the best way to handle your condition.”

He knew the truth, of course. He knew that Maisie’s condition was not about ligaments or muscles or carpal tunnels. Instead, it was about a vague but allencompassing dissatisfaction with her life, a non-specific longing which started way down in her toes and tickled like spider’s feet in her solar plexus. Janet shook her head. “I’ve been playing piano for more than fifty years, and I’ve never had to take a break.”

“Not everybody is built the same way,” Adrian replied gently.

“What will you do with your time, Maisie?” her mother asked. “Adrian will be touring over Christmas, and at summer school for most of January. I hope you aren’t going to mope about at home while I’m trying to teach.”

Maisie weighed up how to word her answer.

However she said it, it was going to hurt Janet. Sometimes Maisie felt her circumstances had too quickly slipped from possibilities into inevitabilities. She had never made a conscious choice to be a musician; her parents being who they were, it was expected she would learn music, but she had never displayed her father’s brilliance or her mother’s fiery genius. Just a clear-eyed grasp of the skill, an aptitude that was little more than intellectual, probably little more than genetic. Increasingly, she had begun to wonder if there was something else out there for her, something for which she would feel the pangs of obsession that Adrian said he felt for his work. To sort it out properly she needed space, air, perspective, none of which she could find in her parents’ sterile house during the endless subtropical summer. She cleared her throat, ventured a few words: “I thought I might go on a little trip away.”

“Where?”

Adrian squeezed her hand under the table. The two of them had already had this conversation in private.

“I thought I might go look up my grandmother.”

“Grandma Fielding? She’s ninety-five and

practically –”

“No. Not Dad’s mother. Your mother. In Yorkshire.”

Silence. Janet pushed her lips together.

“Mum?” Maisie asked.

Janet shook her head. “Are you trying to upset me?

Is that why you’re doing this?”

“But Mum . . . I’ve never met her. You and Dad never talk about her.”

“For a reason, Maisie.”

“What reason?”

Janet picked up a spoon and stirred her halffinished tea vigorously. “She’s a crazy old . . . she’s mad. She could even be dangerous.”

“I’m sure she’s not. It would be perfect, Mum. To stay with her out on some windswept moor while I recover.”

“Forget it.”

“I don’t need your permission.”

Janet fixed her with an icy glare. “But you do need her address. You don’t even know her name.”

Maisie feigned indifference as a ward against her mother’s temper. “Whatever. Just think about it.”

“I don’t need to think about it.”

“Sleep on it. Please.” She looked around. The waitress was stacking chairs on top of tables. “I think they’re about to close. We should go.”

“I’ll get the bill,” Adrian volunteered. Maisie watched him move up to the counter then turned to look expectantly at her mother.

“The answer is no,” Janet said.

And so the first battle began.

***

Maisie booked a flight first thing Monday morning.

“She’s going to go nuts,” Adrian said as Maisie threw the airline ticket on the bed between them with a flourish. They lived together in a downstairs bedroom in Maisie’s parents’ house, a little cramped and cluttered, but it had its own ensuite bathroom and a separate entrance. Sometimes they could almost pretend they lived alone.

“She hasn’t objected to me going to England, just going to Yorkshire. In fact, she’s hardly spoken two words to me since Thursday night. I guess she thinks if she doesn’t get into a conversation with me I can’t bring it up again.”

“Do you even know where your grandmother lives?

How are you going to find her?”

“I know this much. She lives near the seaside and her surname is probably Hartley – that’s Mum’s maiden name. I’ll find her if it takes me all summer.”

“Winter. It’s winter over there don’t forget. You’ll freeze.”

“It’s better than waiting here all alone while you gallivant around the country being an opera star.”

Maisie fell back amongst the pillows. “I’m looking forward to it. Like an adventure.”

“Like finding a needle in a haystack.” Adrian lay beside her. “I’ll miss you.”

“You would have hardly seen me anyway.”

“It’s the distance. You’ll be on the other side of the world.”

Maisie shrugged. “We should get used to it. When my adventure is over I guess I’ll have to go back to playing in the orchestra, and you’ll be off all over the world without me.” She groaned and covered her eyes.

“I don’t want to think about it. I don’t want to think about having to go back to the orchestra.”

“You’re crazy. I can’t imagine a better job.”

Maisie laughed. “God, you sound just like her. There’s a whole world out there, Adrian. There are millions of people who don’t even know there’s more than one Bach.” She uncovered her eyes and looked up at him. “Do you think my mother dyes her hair?”

“I don’t know. Why?”

“There’s not a glimmer of grey and she says she doesn’t dye it.”

“Perhaps it’s natural.”

“She’s such an enigma. She’s so full of secrets.”

Maisie rolled over and picked up her airline ticket.

“This time she’s not going to win. I’m going to find my grandmother.”

Reverend Linden Fowler felt the cold more than most people. His bony body needed to be wrapped in four or five layers before he would venture into the church office most mornings, and even then he had to turn the radiator up to full and drink two hot cups of tea before he could think clearly enough to work. November was the worst time of the year with winter approaching and a wind which seemed to come direct from the Arctic roaring off the sea. As he walked the narrow path between his house and the church every morning in the chill air, he dreamed of tropical climes and sunny skies. He had no choice, however, but to remain here on the north Yorkshire coast. Solgreve’s tiny community needed him; it was a matter of Faith. Reverend Fowler was surprised on this morning to find Tony Blake, the stout village constable, waiting in his office. Rather than his uniform, the constable was wearing denim pants and a musty woollen pullover. The Reverend noted that he looked rather more stupid and slack-jawed without his crisp black and a badge to impress.

“Good morning, Reverend,” Tony said with a dip of his head.

“Tony. Is there some problem?” He went to the radiator and turned the dial up to the last notch, then hung his scarf and hat on a hook by the old bookcase.

“Could be. I saw a man snooping around Sybill Hartley’s cottage yesterday. Asked him what his business was, and he told me he’s a solicitor. Works on behalf of Mrs Hartley’s inheritors.”

“She had family?”

“In Australia, Reverend.”

Reverend Fowler released his trapped breath. “Oh. Well, that’s a long way off. Perhaps they’re just finding out how much it’s worth. If we’re lucky they’ll order the old place knocked down.” He shook his head. “The last thing we need in Solgreve is new people, Tony.”

“You don’t need to tell me that.”

“Did you get this solicitor’s name?”

“I got his business card.” Tony handed over a white square of card. The solicitor’s name was Perry Daniels and he kept offices in York.

“Awful warm in here, Reverend,” Tony said.

The Reverend waved a hand in dismissal. “I’ll take care of this. Keep an eye on the place, won’t you?”

“Of course. Of course I will.”

Tony closed the door quietly behind him as he left. The Reverend paced his office, studying the card. It was a habit of his to pace, and the beige carpet was worn in a path from door to bookcase. His office was not lush and tidy. Rather, the furniture was built of that chunky amber-toned wood that was popular in the sixties, his desk scarred and ink-stained, the curtains and other fittings a sickly olive green. He came to rest near the window, looking out over the vast expanse of Solgreve cemetery, the sea a grey-blue streak beyond it under a slate sky. No, he wouldn’t call Perry Daniels in York. It would only make the solicitor curious, and curiosity was best deflected away from Solgreve. The cottage was old and rundown, and the chances were that the solicitor was inspecting it merely to estimate the property’s value. Who would come to a remote, freezing village like Solgreve and want to live in a centuries-old stone house with a sagging roof and rising damp? He was quite sure Solgreve would remain safe from the eyes of the world. Adrian was halfway up the stairs, under orders from Maisie to get tea for them both, when he heard Janet and Roland Fielding engaged in heated discussion in the lounge room above him. This was one of the hazards of living with his girlfriend’s parents: the unbearable discomfort of witnessing the occasional family argument. He was about to turn and go back to their room when he realised they were talking about Maisie’s trip. Guiltily, he paused to listen.

“We can’t stop her going, Janet,” Roland was saying. “She’s a grown woman and she can go on a holiday to England if she wants.”

“But we can’t let her go up to Yorkshire.”

“I think you’re being foolish. What your mother did was no great sin.”

“Not once, Roland, but twice. Twice they caught her.”

“She was old and bewildered. Perhaps even senile.”

“Never. Not my mother. You forget that I know her. I know about her foolish ideas, and I know about her stupid obsessions. And you, no matter how lapsed a Catholic you claim to be, you ought to be appalled at the idea of your daughter being part of that world.”

There was a short silence. Possibilities started to race through Adrian’s mind. Was Maisie’s grandmother some kind of criminal?

“Even if there was any danger in Maisie meeting her grandmother, Janet, that danger has now passed. You know that.”

“But Maisie’s like her, she always has been. Being in that environment might . . . I don’t know . . . stir things up. Besides, for all we know the house could be ready to fall down around her.”

“It’s not,” Roland said. “I sent your mother’s solicitor up there. He says it’s a bit rundown, but still livable.”

“You did what? Behind my back?” Adrian

recognised that tone. Janet’s frighteningly icy indignation was rare, but unnerving. It was the reason everybody avoided fighting with her.

“Now don’t lose your temper.”

“Don’t lose my . . . you contacted my mother’s solicitor without telling me?”

“She’s determined to go, Janet.”

“I’ve told her she can’t, so she won’t.”

“Perhaps we should get her up here so we can all discuss this rationally.”

Adrian realised now would be a good time to head back to his room. He turned and started down the stairs just as Roland rounded the corner. At precisely that moment Maisie opened the door of their bedroom.

“Hey, where’s my cup of tea?” she asked.

“I . . .”

“Maisie,” her father said. “Can we have a word with you?”

Janet was suddenly at Roland’s shoulder. “Adrian!

You must talk some sense to her.”

Adrian stood trapped between them all on the stairs.

“What are you talking about, Mum?” Maisie

asked, her black eyes narrowing.

“Adrian, please. It’s for her own good. You wouldn’t want her to be in any danger, would you?”

Roland shook his head. “Janet. There is no danger any more.”

“There is!” Janet cried, stamping her foot like a small girl. “I know my mother and I know that if Maisie goes there she’ll be in trouble.”

The top of the stairs was barred by Janet and Roland. Maisie stood at the bottom looking furious. Adrian hated conflict; he was sure it was bad for his voice. Stress created digestive problems. Digestive problems created throat problems.

“This is not about your mother,” Maisie said, spitting the words out. “This is about you. This is about you having to control everything that I do. Now I’ve left the orchestra, you can’t bear to think of me doing something that you aren’t totally in control of.”

“Maisie, that’s not true.” Janet’s eyes started with tears and Adrian glanced politely away.

“I am going. And if you don’t help me find her, then I’ll find her by myself.”

“Maisie, no. Adrian, talk to her.”

“I . . .”

“Don’t bring him into it, Janet,” Roland admonished.

“Nobody ever listens to me!” Janet cried. Her face was flushed and a strand of her normally smooth hair had escaped and clung to her cheek.

“Everybody always listens to you,” Maisie shot back. “Everybody always has to do what you say or you behave like this . . . like a child.” Maisie turned her back and marched away. The bedroom door slammed behind her.

Janet turned on Roland. “Look at all the trouble you’ve caused. Why can’t you support me on this?” She too stormed off, and another door slammed somewhere within the house. Roland and Adrian stood looking at each other.

“I’m sorry about that,” Roland said.

Adrian shrugged. “I’d better go . . .” He indicated towards their room.

“Yes.” Roland glanced over his shoulder, then back to Adrian. “Yes, me too.”

“It’s not true, is it? I mean, Maisie won’t be in any kind of . . . danger from her grandmother?” It sounded almost laughable, but he kept a straight face.

“No. Any chance of that has . . . passed.”

Adrian felt a surge of relief. “Thanks. Good luck with Janet.”

Roland gave a small, strained smile. “She’ll come round. She has to.”

Four days before she was due to leave, Maisie sat alone in her bedroom reading a Lonely Planet guide and highlighting bed-and-breakfast hotels in Yorkshire. Adrian was at rehearsal for a series of Christmas concerts which would take him touring around the country throughout December. She already hated letting him out of her sight, knowing only a short time remained before they then wouldn’t see each other for months. They had been apart before, but usually it was Adrian going away for master classes and tours. It felt strange to be leaving him behind for a change. A brief knock sounded at the door and her mother came in. Maisie looked up in surprise. Janet had been icy towards her for weeks, not venturing down here once.

“Mum?”

Janet had strained lines around her mouth. She sat on the edge of the bed and ran a hand over her smooth hair. In her other hand she clutched something, so tightly her knuckles were almost white.

“Maisie, I have to say something to you.”

“What is it?”

A deep breath. “My mother and I . . .” She paused, turning her dark eyes downwards. Maisie realised, with embarrassment, that her mother was about to cry.

“My mother and I did not get along,” Janet

continued. “We had some fundamental differences of opinion which drove us apart. And I . . .” A tear skidded down her pale cheek. “I regret that a very great deal.”

Her words trailed off into little more than a breath. Maisie tentatively reached out a hand, but her mother withdrew, standing and facing the small window instead. “I don’t want that to happen with us,” she said, matter-of-fact.

“It won’t,” Maisie said, not sure if it were true. There was a long silence. Maisie watched Janet’s back. The quiet beat hard in her ears.

“Mum. You can still make it up with your mother.”

A shake of the head, but no reply.

“You could come with me,” Maisie suggested, guilty that she couldn’t imbue her voice with more sincerity. “It’s not too late. We’ll go find her together. You can . . . make amends.” Not apologise. Janet Fielding did not apologise.

That silence again, longer. This time Janet’s back trembled, as though she were trying to stop herself from crying.

“It is too late,” she said finally, quietly.

“No, it’s not. Come with me,” Maisie said, even though having to share her holiday with her mother filled her with sick disappointment. It wasn’t really escaping, it wasn’t really running away if her mother came with her.

Janet turned, face stony, held out her hand and dropped something on the bed. Maisie looked down. A set of keys.

“Mum?”

“The keys to her cottage. Saint Mary’s Lane, Solgreve.”

Maisie picked up the keys and looked at them in astonishment.

“And whatever you find there, whatever you find out about her . . . try to be sensible. Try to remember . . . who you are. What I’ve brought you up to be.”

“I don’t understand. Have you spoken with her?

Does she know I’m coming?”

Janet shook her head. “She’s dead. She’s been dead since September.”

“Dead.” Maisie’s heart went cold. “Why didn’t you tell me?”

But Janet was already out the door, closing it firmly behind her, leaving Maisie holding the keys, cool in her palm.

CHAPTER TWO

Maisie felt as though she had been travelling forever –

one long, endless night, broken only by a few glimmers of daylight through foggy windows and heavy eyelids. The unbearable, wriggling discomfort of the plane from Brisbane to Heathrow, the zombie-like hour waiting at King’s Cross Station for the train to York, cursing herself for not arranging to stay in London for a few days to recover. And then from York the connecting bus direct to Whitby, but the service which ran through Solgreve – infrequent at the best of times –

wasn’t running today. By then she was so close to the end of the journey that it made a weird kind of sense to jump into a taxi and pay whatever it cost to ride the twenty-three miles to Solgreve.

So she now sat in the back of an overheated taxi calculating that she had been travelling for nearly thirty-five hours. Apart from two blissful hours on the bus from York, when the seat next to her had been empty and she’d been able to put her head down to sleep, she had been either wide awake or in a desperate half-doze which wasn’t restful because it was so anxiously taken. She admitted to herself that she had never before fully understood what was meant by

“dead tired.” What she wanted, more than anything in the world, was a soft, warm bed.

“This is the turn-off to Solgreve,” the taxi driver was saying. “Do you have any idea where you’re going from here?”

Maisie roused herself out of her jet-lagged stupor.

“Yes. Yes, I have a map.” She fished in her bag for the hand-drawn map which Perry Daniels, the solicitor, had faxed her – was it only the previous day? It seemed like a lifetime ago – and gave it to the taxi driver. He pulled over and studied it.

“Right,” he said, handing back the map. “I think I know where that is. I don’t come out here much.”

“I don’t know how accurate it is,” Maisie said. “It seems a bit out of proportion.”

“No, it’s about right,” the taxi driver replied as he pulled back into the street.

Maisie looked at the map. “But the cemetery . . .”

“One of the biggest in Yorkshire. It’s Solgreve’s only claim to fame. That and the fact that nobody here is very friendly.”

Maisie didn’t reply.

“Sorry. I didn’t mean to offend you. You have family here, don’t you?”

“Oh, no. I’m not offended. I’m just very tired.”

“This is the main street,” the taxi driver said. “The bus stop is over there, opposite the church. But the service only comes through three times a week.”

Maisie peered out the window. Even though it wasn’t quite four o’clock in the afternoon, the light was fading. On her left was a rusty sign with a picture of a bus on it. On her right was a little stone church. Behind the church were three pillars and a crumbling Gothicstyle wall.

“That’s the old abbey. They built the new church on the same foundations. It’s been a sacred site for centuries.”

“I see,” said Maisie.

Something about its attenuated shadows both fascinated and unnerved her. But then, she was so tired she probably wasn’t thinking straight. Through its empty arches she glimpsed the sea.

To the north of the abbey an enormous cemetery was laid out to the cliff’s edge. On her other side were lichen-covered cottages, tiny shops, and narrow cobbled streets. She had started to feel weak and nauseous, and the closer they drew to her grandmother’s cottage, the more this seemed like the stupidest idea she had ever had in her life.

“Here we are, Saint Mary’s Lane. That must be the place you’re looking for.”

It was the only cottage on the lane. Overgrown lots lay empty beside it, and the road petered off to a dirt track leading to the cliffs beyond it. Between the house and the cliffs, trees grew wild for half a kilometre. The cottage itself was grey stone, a squat single storey with painted white sills, bars on the windows and a roof of motley tiles. It looked very old and very cold, and the low stone fence barely seemed able to defend it from the tangled wood which seemed to surround it, and the vast moors stretching out behind.

As the taxi pulled up, she felt in the side pocket of her bag for the keys, and clutched them in a trembling hand. The taxi driver was already out getting her suitcases from the boot. She climbed from the car on shaky legs and handed him the fare. The air was crisp and she shivered in her long-sleeved shirt. The smell of the sea was almost sharp in her nostrils, and she could hear it beating in the distance, late afternoon gulls calling to each other above.

“You know,” said the driver looking up at the front of the house, “I think I’ve been here before. I remember dropping off a real posh lady with lots of gold jewellery. Would have been about a year ago.”

“It might have been my grandmother,” Maisie said.

“No offence, love, but she wasn’t old enough to be anybody’s grandmother.” He turned back to her.

“Good luck.”

“Thank you,” she replied, feeling fairly sure that she would be calling him tomorrow to take her all the way back to somewhere warm and modern.

She walked up the front path, weighed down by suitcases, and paused at the front door. With surprise, she noticed that the garden around the house was immaculate. Her grandmother had been dead for nearly three months, but the grass wasn’t overgrown and the flower beds were weed-free. Surely the solicitor hadn’t been out here gardening?

Despite her shaking hand, she managed to get the keys into one, two, three locks – clearly, her grandmother had been security conscious – and she opened the front door. It was only marginally warmer inside. She kicked her suitcases ahead of her and closed the door, reaching around on the wall for a light switch. A dim, yellow light illuminated a grey hallway – it may have been white once – and a note on a hall table next to a coat rack. It was from Perry Daniels. She picked it up and moved further into the musty cottage. On the left of the hallway was a small lounge room and a dim kitchen. On her right was a bedroom and beyond that a bathroom with – god forbid – no shower, just a bath. Attached to the tap was a hose with a shower nozzle on the end. Maisie’s heart sank. Showers were one of life’s great joys. Behind the bathroom was a laundry with an aged washing machine, a brand new wallmounted dryer, and an old boiler which she turned on. It grumbled into life. The back door led out of the laundry. She didn’t open it. The grand tour could wait until tomorrow. The last room on the left was a half-size bedroom, without a bed. It was filled instead with stacks and stacks of books and papers. An old, brown wardrobe leaned violently to its left on bent chipboard legs. A desk, overflowing with papers, was crammed into a corner. Maisie backed away. Plenty of time to clean that up later. She returned to the bedroom. A radiator was mounted on the wall under the window and she cranked it up to high. Maisie looked at Perry Daniels’s note. He explained that he had had the telephone and electricity reconnected the previous week. Hurrah for Perry Daniels. Maisie turned slowly, gazing around her. More books and papers, a large chest and, most importantly, a big, soft bed. She kicked her shoes off and lay down – only for a minute, of course. Just while she read the solicitor’s note.

She yawned enormously and ran her eyes over the letter. Milk, bread and eggs in the kitchen. Forty pounds in the box on the mantelpiece in the lounge room. Did that mean there was a fireplace? That was something to get excited about; not that she knew how to light a fire. Call me if you have any problems. Regards, Perry Daniels. Good old Perry Daniels. Her only friend in the near vicinity. She could have wept. Instead, without making a conscious decision to do so, she dozed off.

When one of the locals dropped by that evening, she was fast asleep and dreaming about Adrian. Together they were trying to sort out reams and reams of sheet music that had become mixed up. She was trying to follow the lines of score from one page to the next but none of it was making any sense. Adrian had pulled out certain sheets and was pinning them to the wall of their bedroom, and he hammered each thumb tack in with the side of his fist. At some point she became aware that the knocking was not coming from her dream, but rather from outside it, and she woke, disoriented and dizzy in a strange bedroom.

Her grandmother’s house, that’s right. She was a million miles from home, and there had been that nightmare of travel in between. She checked her watch. Eight o’clock. And somebody was knocking at the door.

“Hang on,” she croaked, heaving herself up from the bed. The light was still on in the dirty hallway. She approached the door and at the last moment

remembered the bars on her grandmother’s windows. Was it safe to open the door at night?

“Who is it?” she called, trying to sound capable and strong.

“It’s the local Reverend.”

The Reverend? She opened the door and peered out. A short, pale man with watery blue eyes looked back at her. His overcoat was at least four sizes too big for him. She could just see his white collar peeking out from under the layers. He gave her a friendly smile, revealing a perfect set of false teeth, slightly ill-fitting. He was seventy if he was a day.

“Good evening. I’m Reverend Linden Fowler,” he said.

“Hello,” she said, smiling back. “I wasn’t expecting visitors just yet.” The air outside was frigid, and a fresh wind played with the treetops.

“Oh, you’ve only just arrived? I am sorry. I saw the light on and just wanted to check up on the place. It’s been empty since Sybill . . . passed.”

Sybill. Her grandmother’s name was Sybill. Her mother had responded to all Maisie’s questions with a standard “you’ll find out soon enough.” It was Janet’s way of punishing her. Maisie took a moment to think of the name. Sybill.

“Are you a relative of Sybill’s?”

Maisie looked up. He still had that friendly, crooked-denture smile on his face, and she found herself warming to him. “I’m her granddaughter, Maisie Fielding.” She extended her hand and he took it. His skin was very soft. “Please, come in out of the cold.”

He looked past her as though he longed to be inside, but he shook his head, withdrawing his hand.

“No, I won’t, thank you all the same. I’ve probably disturbed you sufficiently already. But feel free to drop by at the parish office if you like, and of course you’re welcome to come to a service. Though I don’t suppose you’ll be staying long.”

“I don’t know how long I’ll be staying.” Had she ever really thought three months away from home in this chilly, damp place a good idea?

“One week perhaps?”

“No, longer than that. But I’m not certain how much longer.”

“I’m sure this draughty house and our modest community wouldn’t interest someone like yourself for very long. No visitors ever stay for more than a week or so.”

Maisie, dazed and addled as she was, began to understand that the Reverend was anxious to know how long she would be here. She felt sorry for the little man, trying so hard to be polite and discreet.

“My original intention was to stay for the entire winter, sort out my grandmother’s things.”

He physically recoiled. “The entire winter. But . . . it’s so cold here,” he finished lamely.

Maisie considered him. She had thought he was concerned she would find his village unappealing and go home, but now she wasn’t sure what he was getting at. Her brain was too tired to process the information, so she just said, “I’m sorry, Reverend. I can’t tell you for certain. It could be that I’m ready to go home much sooner.”

He nodded and tried a smile again, but this time it was more strained. “Thank you for your time, Miss Fielding. I’d best be on my way.”

“Goodnight, then.”

“Yes, goodnight.” He had turned and headed up the path. She watched until he was on the road and then closed the door.

Maisie turned around and stood in the hall, looking from left to right. What next? More sleep? She wasn’t tired any more. Her stomach growled. Ah yes, food. She made her way down to the kitchen and opened the fridge door. It was an old-fashioned fridge, off-white with rust spots. Inside, along with a funny smell, was a carton of milk and nothing else. She closed the door and began opening cupboards. Bread, butter, eggs, teabags, sugar were all stacked together in one of the cupboards, cowering from the clutter of pots, pans and plastic containers. The kitchen was unfamiliar and the stove looked a century old, and nor could she find an electric kettle. She didn’t have the mental energy to figure out how to cook anything, so she made herself bread and butter and a glass of milk and sat down at the kitchen table to eat it. As she did, she looked around the kitchen and tried to imagine it tidied and painted. Here was a principal difference between her mother and grandmother: Janet Fielding was very particular about her home; Sybill, clearly, was not.

Sybill. Maisie wished she had asked the Reverend more about her grandmother. What kind of person was she? What did she look like? Had she been lonely living up here on a cliff-top by herself? What did she do with her time, given that she wasn’t cleaning the house? And most importantly, what was the secret that her mother was keeping from her? Maisie hadn’t found any headless bodies in the cupboards yet, but there were a lot of cupboards in this place. Knowing Janet, their falling-out was probably over something minor, something about which her mother would say “but it’s the principle”, as if principles were life rafts and she a drowning swimmer. Maisie rinsed her plate and glass and went to look for the telephone. She found it in the lounge room, but she found no radiator. She looked behind curtains and armchairs, then realised that the room had a fireplace –

no need for a radiator as well. Her problem now was that she had no clue how to light a fire. A stack of newspapers and a wire rack with a few logs on it sat next to the hearth, but she was too tired and homesick –

yes, that was the other feeling no matter how much she resisted it – to work it out. She just wanted to call Adrian, hear his voice and make contact with something resembling normality.

No dial tone. How irritating. She checked the connection and everything looked okay. Perry Daniels had lied to her. Perhaps it wasn’t his fault, perhaps it was British Telecom’s. In any case, she hoped Adrian wouldn’t worry that he hadn’t heard from her yet. She replaced the receiver and picked up a photograph in a frame that sat next to the phone, examined the people in the picture.

A white-haired lady in a red dress – too bright a red for a woman that age, really – smiled out of the photo. Maisie guessed this was Sybill. She had a nice face, perhaps looked like she didn’t take herself too seriously. She had her arm around a youngish man. Maisie wondered if he might be a long-lost cousin or something, as his hair was the same black as hers, his eyes the same dark, dark brown. But there was some kind of Eastern European aspect around his eyes and cheekbones, something a little exotic about his eyebrows. So her grandmother had friends. That was good.

Maisie stood and yawned. Was she tired enough to sleep again? She had a horrible feeling that if she did she would be awake at around three a.m. It hardly mattered really. So what if she was up at odd hours for a few nights? All she had to do here was sort out her grandmother’s clutter. This time she would turn out all the lights to discourage the visits of local Reverends. She was in the kitchen, her hand just falling away from the light switch, when she heard . . . what was it?

Footsteps? But light, gliding footsteps. Perhaps not footsteps at all. She froze where she was, her body tense as she listened. She had almost managed to convince herself that she had heard nothing when the sound came again. This time she could pinpoint it as being somewhere beyond the grotty laundry window.

“Now, Maisie,” she said, under her breath. “This is a new place – you don’t know what’s a normal noise and what isn’t.” It could be the wind. Or a cat. Or a . . . Suddenly, a scratch on the glass. Despite herself, she let out a little yelp of fright. She ran away from the noise, towards her grandmother’s bedroom, burrowed under the covers and tried to compose herself. So it was a spooky noise. It didn’t necessarily follow that it had a spooky cause. She remembered as a teenager a Danish exchange student had stayed with them for a month. On the first night he had freaked out and woken the whole household after hearing strange, light footsteps on the roof and a sinister growling. What he had imagined as a dark, diabolic figure running lithely from rooftop to rooftop in search of . . . souls?

children’s eyes? . . . was, in fact, the humble possum which had lived in their roof forever. This was just the Solgreve equivalent of a possum in the roof. And anyway, she found that with the covers over her ears, she could hear nothing but her breath and the beating of her own heart.

CHAPTER THREE

Though he was loath to admit it, Reverend Fowler was afraid of Lester Baines. The big man sat across from him, all meaty forearms and ill-fitting clothes, looking like a criminal. Which was exactly what he was.

“Rev, don’t worry. I have sources all over the place

– something will turn up soon.”

“But you mustn’t take unnecessary risks. Nobody must know.”

Lester twisted his lips into a kind of smile. “Hey, give me some credit. Haven’t I been doing this for you for ten years?”

That was true, taking away the short stretches Lester had spent in prison for various minor misdemeanours. But Reverend Fowler found it difficult to trust someone who could so blithely drive from one end of the country to the other with a body in the boot of his car.

Lester was on his feet now, looking around the office, picking up framed photographs and inspecting them. He always did this, and it always made Reverend Fowler nervous. The big man was just so confident, as if nothing frightened him. In contrast, the Reverend was painfully aware of his own physical weakness – he had ever been a small man – and of his own inability to be calm. He felt like a bird, tiny delicate heart beating frantically just in the business of living, while Lester was a deep-sea turtle. Which meant that in ordinary circumstances the crook would outlive him a hundredfold. But ordinary circumstances did not apply in Solgreve.

“You mind me asking something, Rev?”

He did mind. Lester always asked the same

question. “What is it?”

“Why is it a nice bloke like you . . . I mean, you’re a priest, yeah?”

Reverend Fowler shrugged, turned his palms

upwards.

Lester came back to his chair, leaned forward on the ugly desk and asked earnestly, “What do you do with the bodies?”

“Lester, you know I can’t tell you.”

“But you seem like such a nice geezer.”

“I am a nice . . . geezer. I’ve made a study of being so. It’s my job.”

“The two don’t go together – you being so soft and then paying me to snatch bodies from morgues.”

Even though nobody could hear them, Reverend Fowler felt the urge to shush him. If he had his way, they wouldn’t discuss the hows and whys of this project. Lester would come to him, take his money, then return in a week or two weeks with the necessary goods. But Lester was chatty, and the Reverend was too intimidated by him to try to shut him up. Another man might be able to be aloof, professionally cold, even arrogant. But Reverend Fowler was not that man.

“I serve a power greater than myself,” he said simply. “That is all I can say.”

Lester ran immense hands over his stubbly head.

“I’ll never understand you, Rev. Still, I like working for you.” He pulled his massive body up to its full height and yawned immodestly. “I’ll have something for you in a week or two, yeah?”

“Thank you, Lester. And I can count on your discretion?” One of his greatest fears was that Lester would gossip among his friends about the business here in Solgreve, about the kindly priest who ordered the occasional corpse.

Lester nodded. “Of course you can,” he said, patting his jacket pocket. “You’ve paid for it.”

Maisie was discovering the delights of attempting to shower under an alternately freezing gush or scalding trickle when the telephone rang the next morning. She quickly twisted off the taps, grabbed a towel, and dashed to answer it.

“Hello?”

“Good morning. It’s Perry Daniels.”

“Oh, hi.” She heard the nasal twang of her accent for the first time in comparison with Perry Daniels’s perfect English pronunciation.

“How was your trip?”

“Traumatic.”

“Yes, it’s a long way. But the phone is connected now, which is good. I tried to call once or twice last

K I M W I L K I N S

night without much luck. I do apologise. I had organised for it to be working when you arrived but these things can be unreliable.”

“It’s fine.” There it was again. Foine. How had she managed to get through her life so far talking like this?

She had to work on her vowel sounds.

“Now, do you know how long you’ll be staying?”

Maisie turned and looked around the untidy room. It could take years. “That depends on how homesick I get. I intend to sort out my grandmother’s stuff at least. My return flight is booked for the fourteenth of February, but I don’t know if I’ll make it that far.”

“If you stay that long, you’ll probably see some snow.”

Snow. Her mind filled with fairytale pictures of winter wonderlands. Perhaps that would be worth staying for, especially compared to the oppressive summer waiting for her back home.

“I’ll let you know in plenty of time when I’m going back to Australia.”

“Good, because we’ll have to decide what to do with the property. In any case, Maisie, enjoy your stay. Don’t hesitate to phone me if I can help you in any way.”

“Thanks. I will.”

She was slightly relieved to hang up on that posh voice. Back home she had always considered herself well-spoken. Don’t tell me I’m getting homesick already. She dialled Adrian’s number. At least not homesick for Brisbane. That would be too tragic.

“Hello?”

“Hello, is that Adrian Lapidea, the famous opera singer?” The name was a joke. Adrian’s real surname was Stone, but given that most opera stars were Spanish or Italian, she sometimes used the Latin translation to tease him.

“Maisie! God, I’m so glad you called. You’ve been gone for two days.”

“I tried to call last night – yesterday morning your time – but the phone hadn’t been connected.”

“Listen, I’ve got a rehearsal in twenty-five minutes. I’m literally just walking out the door.”

Maisie felt her heart sink. “But I haven’t spoken to you in so long.”

“I’ll phone when I get back around eleven. I have the number here from the fax the solicitor sent you.”

“This is going to cost us a fortune in phone calls, isn’t it?”

“We’ll manage. One other thing – it was so weird, but on the way back from dropping you at the airport I stopped in town and I ran into Sarah Ellis. Do you remember her?”

“Was she one of those two sisters who were in the choir you used to sing with? The hippy girls?”

“Yes, that’s right.”

“What’s weird about seeing her?”

“Her sister, Cathy, the red-haired one, moved to York in September. She’s studying medieval

archaeology at the university there.”

“Really?”

“You liked her, didn’t you? I mean, they were both friendly enough girls.”

“She’s okay. Why?”

“I got her phone number for you, in case you get lonely. It seemed like too much of a coincidence not to exploit it. York’s not far from where you are and I’d be much happier if I knew you had some company.”

Maisie scratched around for a pen and paper. She doubted that she would actually call Cathy Ellis, but as Adrian had gone to the trouble of getting the number she may as well write it down. “Go ahead.”

Adrian dictated the number. “Sarah seemed to think she’d be happy to hear from you. Apparently she’s been a bit lonely.”

“Whatever. I might call her.”

“I have to go, darling. I love you.”

“I love you too.”

She was unprepared for how devastating the click at the other end of the phone could be. Tears sprung to her eyes. “Shit,” she said, “shit, shit, shit.” He was just so far away. She took a deep breath. She would not cry. Crying would solve nothing.

She took her towel back to the bathroom – whose idea had it been to paint the walls salmon pink with navy trim? – then went to the bedroom to get dressed and pack her things away. She found a tube of Pringles that she had bought while waiting at Kings Cross for the train, and they seemed just the thing to have for breakfast given she hadn’t found the toaster yet. Maisie crammed some chips into her mouth and pulled the wardrobe door open with a creak. As she had suspected, the wardrobe was overflowing with more clutter. About two dozen dresses hung there with four or five coats, old clothes folded up in the bottom, shoes crowded in anywhere. This was going to be more difficult than she thought. But then, if she had been close to or fond of her grandmother, she might feel obliged to keep everything. Instead, she could simply package it all up and take it to Oxfam. One by one she pulled down the dresses and piled them near the bedroom door. She hung up her own clothes and was so satisfied with her work that she started on the chest of drawers.

Sybill’s underwear, cardigans, wool blouses and skirts were haphazardly folded among what smelled like decades-old soap and perfumed drawer liners. Maisie pulled it all out. In the bottom drawer she found a small jewellery box: bits and pieces of junky jewellery and old keys. Maybe she should hold on to one or two of these things for her mother, as a keepsake. No, that made no sense. The animosity there was too old and too deep, and besides, Maisie wanted to get the place cleared of as much clutter as she could as soon as possible so that she could live here comfortably. In that respect she was the same as her mother – she liked things to be tidy. She kept what looked valuable and threw the rest on the pile. She filled the drawers with her own things, lined up her toiletries on top of the chest, then stopped to put on a bit of make-up when she saw how sickly she looked in the mirror. Jetlag was not a girl’s kindest fashion accessory.

As she was sliding her suitcases under the bed, an old hatbox edged out. Curious, Maisie opened it. It was full of half-written short stories, scraps of poetry, pencil sketches and designs. The few lines of poetry Maisie glanced at were desperately bad, but the drawings were excellent which surprised her; like her mother, Maisie was capable of drawing nothing more complex than stick figures.

Maisie closed the box and reorganised under the bed so her suitcases could fit. This was fun – she was learning about her grandmother. Sybill wore bright colours, she was creative, she had at least two friends –

a handsome young man and a rich lady who caught cabs from Whitby to see her – and she was very, very untidy. Already, Maisie was sensing that Sybill might be eccentric, which would go some of the way towards explaining why Janet was so at odds with her. Some of the way, but not all of the way.

Maisie stripped the linen off the bed and prepared to change it. Kind of creepy to think that her grandmother had slept among these sheets before she had died. In fact, Maisie couldn’t know for sure that the old woman hadn’t died in her bed and lain there for a few days before anyone had found her. Last night she had been too tired to worry about things like that, but now it seemed urgent, ghastly. She turned the mattress over and took the sheets, pillowslips and quilt cover to the laundry. At the foot of her bed was a large chest, where Maisie expected to find more linen. She flipped it open.

A layer of red silk covered the contents. Maisie lifted it back and was surprised to find no linen. Instead, a bizarre collection of objects. A bronze dish with scorch marks inside, a brass cup, an incense holder, spare sticks of incense wrapped in plastic, candles, a mortar and pestle, a silver-handled knife, a long, grey robe. As she moved further into the chest, she found books of moon and tide charts, tables listing elements, types of rocks and flowers, a mirror wrapped in black velvet, and pouches of white linen tied with string, holding stones, dried herbs, seeds. The tarot cards were merely the confirmation of her suspicion. Her grandmother was a practising witch.

Maisie laughed out loud. Was this it? Was this what her mother’s warning was about? Janet Fielding had always been suspicious of anything that she couldn’t see and bully into her service. Immediately, though, Maisie was overcome by a sense of sadness. Had Janet and Sybill really ended their relationship over this?

Surely the mother-daughter bond of love was stronger than superstition and prejudice.

But she knew Janet.

“Oh, Mum. What were you thinking?” she said as she rummaged further in the chest. She found an old exercise book and flipped it open. The pages were filled with more tables and lists. The date of the first page was June 1960, the last was just months ago in April, and four blank pages followed it. She had never managed to finish the book. Maisie flicked through it. No personal information, just

dispassionately noted magical properties and times. The final item in the chest was a large, inlaid, wooden box. It contained a collection of scrolls nestled in black velvet, with stones and herbs and dried petals accompanying them. Each scroll was made of homemade paper and tied with a black ribbon. She unrolled the scrolls one by one to read them. A simple line was inscribed upon each. All I need to know is disclosed to me.

Across the miles I touch her heart and tell her to come.

He is protected always by divine love.

And one which, after last night’s strange noises, laid a chill over Maisie’s heart. I call the black presence. What black presence? And who were the other people she had written about? Maisie sighed. She would never know, and she wasn’t even sure she believed in witchcraft – white or black. She carefully placed all the objects back in the chest the way she had found them, and decided her grandmother had no spare sheets. That made sense given the condition of the rest of the house. She was overcome by a vague, nauseous headache, so she lay down on the bare mattress.

She dozed for about half an hour before she was woken by a voice heard faintly through the double glazing. Sitting up, she looked towards the window, expecting to see people walking past on their way to the cliffs. Instead, through the gauzy curtains, she saw a dark-haired man standing in the front garden, calling to a fat ginger cat who was digging beneath one of her grandmother’s rosebushes.

“Tabby. Bad girl.”

An off-white van was parked at the end of the front path. Maisie rose and moved closer to the window to see if the man would leave now he had his cat. Then she noticed he had a wire basket containing a trowel, gardening gloves, and gardening fork. And, on closer inspection, the dark-haired man was not a stranger at all, but the young man who had posed for a

photograph with Sybill. She checked her appearance in the mirror, then went to the front door.

“Hello,” she called, as she stepped out into the cold, cloud-lit day. “Can I help you with something?”

He turned with a start. The cat, Tabby, began to run towards her.

“Tabby, no,” he said. But Tabby kept on running, straight past her and into the house.

“I’m sorry,” he said, approaching her. “She used to live here. I didn’t know there was anybody home.”

“She used to live here?”

“Yes, with the previous occupant,” he said. Some exotic accent lingered subtly around his r’s and o’s.

“Sybill.”

“My grandmother.”

“Oh. You’re Maisie. Nice to meet you.” He

extended a hand in greeting. “I’m Sacha Lupus.”

“She knew of me? She knew my name?”

He seemed surprised. “Oh yes. She spoke of you often, though I gathered that you had never met.” Up close Sacha Lupus looked as though he may have been Russian or Romanian or Polish. He was about a head taller than she, with dark, watchful eyes, clear skin and a full mouth.

“No, we hadn’t. In fact, I didn’t even know her name until I got here yesterday. My mother never talked about her.”

“That’s a shame. She would have loved to meet you. She was a special woman. I liked her very much.”

“Did you . . . find her?”

He shook his head. “No, no. I only discovered she was dead when I came to do the gardens a few days later. Reverend Fowler came up to tell me. She took sick one night and tried to get herself down to the village for help. They found her body about a quarter mile from here.”

Even though she hadn’t known Sybill, the story touched her. How cold and pathetic to die alone on the road like that. “Why didn’t she just phone for help?”

“I don’t know. Perhaps she panicked. In any case, I took Tabby with me, but maybe you’d like her for company. I’m sure she’d rather be here than in my tiny flat.”

“You live nearby?”

“I live at Whitby.”

“I’d love to have her, but I don’t know how long I’ll be staying. This isn’t permanent.”

“Take her. She’s a good mouser, and unfortunately there’s a problem here with mice. Just call me when you want me to come back for her. I’m in the phone book.” He fished in the pocket of his jeans. “Oh, and here are the spare keys. Sybill gave them to me in case, well . . . in the end somebody else found her.”

Maisie took the keys. “Thanks. And thank you for keeping the garden even though she’s gone.”

“It’s been my pleasure. I won’t bother you again. I’m very sorry if I gave you a fright.”

“Oh, please. Feel free to keep looking after the garden. I’ll pay you whatever Sybill was paying you.” The words left her lips before she had even thought about it. Just how was she going to pay him? She was already praying for the exchange rate to improve just so she could afford to send Adrian a decent Christmas present. Sacha grinned. “She didn’t pay me. It was a labour of love.”

“Oh. Then I won’t impose on you any further.”

He picked up his wire basket. “Well, I’ll see you when you need me to fetch Tabby then.”

“Yes, fine. Lupus was your surname right?”

“That’s right. L–u–p–u–s. I’ll see you.”

He turned and headed toward his van. She

desperately tried to think of a way to get him to stay. He knew stuff about her grandmother. He was fiercely attractive.

“Sacha,” she called just before he opened the van door.

He spun around. Was he glad she had called him back? No, that was just wishful thinking. “Yes?”

“I know you’ll think I’m a dope, but would you mind showing me how to light the fire?”

They sat in the lounge room, a healthy fire crackling in the grate, drinking coffee. Not only did he know how to start a fire, he knew how to find the kettle, the cups, even the cat food which Tabby was noisily crunching in the next room. She had watched him the whole time in the vague stupor of somebody besotted with beauty, musing all the while on the nobility of gardening as a profession. Imagine not going to university, not pursuing a glorious career, but spending all one’s working life with hands in the soil. It seemed beyond worthy.

“So, how long have you been a gardener?” she asked. He shook his head. “I’m not a gardener. I only did it for your grandmother. She and my mother were friends.”

“I see.” Not a gardener. A poet perhaps? A

sculptor?

“I work in a bakery.”

“Oh.” A baker.

“I serve behind the counter and sweep the floors.”

She didn’t know what to say. “That’s nice.”

“My mother and Sybill worked together for a short time in the eighties. Did you know your grandmother was a well-respected psychic?”

Maisie shook her head in astonishment. “No. Really? I found some witchy things in a chest, but I didn’t realise she was a psychic.”

“Yes. People used to travel miles to consult her. The police in York even got her to work on a couple of child disappearance cases.”

“The taxi driver said he remembered dropping a rich woman off here once.”

“It would have been a client. She was considered the best.”

“Wow. That’s amazing.”

Sacha finished his coffee and put the cup down. She felt a momentary anxiety. Would he leave now? “It’s why she wasn’t very popular around here,” he said.

“Not popular?”

“In Solgreve. Haven’t you noticed something about the residents?”

She shook her head. “I only arrived yesterday. I haven’t even looked in my back garden yet, let alone been to town.”

He laughed. “You’re in for a shock.”

“Why? What’s wrong with them?”

“It’s not that there’s something wrong . . . well, I don’t know. Perhaps I’m about to be offensive.”

“I don’t understand.”

“They’re all very religious.”

“Like fundamentalist looneys?”

“I think they’re just ordinary Anglicans, but yes, they act like fundamentalist looneys at times.”

“The whole town is like this?”

“Practically. There’s only three hundred and twelve people living here. Three hundred and thirteen counting you, and you can be sure that as soon as they know you’re here it will make them nervous.”

“They already know I’m here. Reverend Fowler came up to introduce himself last night.”

Sacha smiled. “I bet he didn’t just come to introduce himself.”

“Come to think of it, he did seem kind of anxious that I tell him when I’m leaving.”

Tabby trotted in to sit between them, delicately licked a paw.

“Sybill was particularly unpopular for doing her magic rituals out the back under the oak tree,” he said.

“They eventually asked her to stop.”

“And did she?”

“I think she just did it later at night, when she was sure nobody was watching.” He checked his watch.

“Would you like another coffee?” she asked, hopefully.

“No, thanks.” At least he didn’t say he’d better be going. At least he looked like he was happy to sit in her lounge a little longer.

“So when you say your mother used to work with Sybill . . .?”

“Fortune-telling. My mother is Romany.”

“A gypsy?” God, he was a gypsy. More exciting than a gardener or a baker by a long shot.

“Yes. My father was gad´zo. Upper class English, an anthropology professor. Sent me to a fancy school but I didn’t finish.”

So what if he didn’t finish school? He was a gypsy.

“That’s so interesting. Where is your mother now?”

He shook his head, clasped his hands between his knees. “I don’t know. Wandering around somewhere. We sometimes go for months without hearing from each other. Anyway, what about you? Why are you here?”

She felt so boring by comparison. “I came to find Sybill. Or at least to find her house and maybe learn a bit about her. Back home I’m a cellist with the City Symphony.”

“Really? Did you bring your cello?”

“No. I’m a bit sick of it at the moment.”

“I’ve never known a musician who could bear to be parted from her instrument before.”

“It wasn’t even what I wanted to do. My mother’s a famous pianist, my father’s a famous conductor. I kind of got pushed.”

“What would you have rather done?”

She leaned back in her chair and thought about it. Nobody had ever actually asked her that before. “I’m not sure. I always preferred the piano, actually, but Mum wasn’t too keen.”

“Jealous?”

Maisie shook her head. “No, I just wasn’t very good. Perhaps I could have studied history instead of music. I could have been a history teacher.”

“Sybill was interested in history. You can tell from her book collection.”

Maisie glanced up at the crowded bookshelf. “I guess the problem is I can’t imagine liking anything enough to want to do it for the rest of my life. I don’t like the idea of having to choose a career and stick by it. I’m twenty-four. If I’m lucky I’ll live another sixty years. It’s just too long to be doing the one thing.”

“I know what you mean.”

She got the sense very strongly that he did, in fact, know what she meant. It made her think of Adrian who never knew what she meant, and that made her feel guilty – entertaining a pretty boy in her lounge room while Adrian was so far away and missing her. He checked his watch. “Listen, I have to go,” he said gently, as if he anticipated the disappointment it might cause her.

“Oh, of course. I shouldn’t hold you up.”

“But I want you to feel free to phone me if you have any other questions about Sybill you think I might be able to answer.”

“Thanks. Thanks very much. And please drop by any time if you’re out this way.”

“I’m hardly ever out this way.”

“Well, if you want to check up on Tabby,” she said lamely, feeling like an overeager fool for asking him. He pulled himself to his feet and Maisie followed him to the door. “It was nice to meet you,” she said.

“Likewise. I’ll see you again.” In a minute he was starting his van. Tabby was rubbing against her ankles. Maisie waved him off then went back inside, half wishing their exchange could have lasted a little longer, and half wishing she wouldn’t hear from him again. She was lonely and vulnerable, and he was a gypsy. God, a gypsy.

“But he works in a bakery, Tabby,” she said to her new companion. “Sweeping floors. It’s not very noble, is it?” Of course, Tabby wouldn’t have cared. The ginger cat would have thought anybody who fed her was noble enough. She sighed and wished for the temperament of a housepet.

Maisie spent the afternoon cursorily tidying the kitchen while Tabby ran around getting underfoot and eagerly sniffing in cupboards for evidence of mice. Next time she checked her watch it was nearly three o’clock. It would be dark soon – she pulled Tabby out of a cupboard and closed it – and she still hadn’t been into the back garden or for a walk out to the cliffs. She grabbed her overcoat and her keys and went out the laundry door.

The wind had picked up since the morning, and the smell of the sea was heavy on the gusts that tangled in her hair. She walked down under a massive oak tree, between two rose beds, and then into the trees behind Sybill’s house, most of them made crooked by the years of insistent winds. The sky had come over dark grey and threatened rain. Maisie took deep, delirious breaths of the cold air. This was what she had imagined it might be like living here: stormy, windswept, exhilarating. Already she could hear the sea pounding the shore. She jammed her hands in her pockets, telling herself she should have worn gloves and a scarf.

But how brisk, how thrilling this kind of cold was. She wove through the trees. Most had lost their foliage apart from a few resolute yellow leaves clinging here and there to fine, bare branches. Moss grew in thick patches upon them. Sodden leaves formed a spongy carpet beneath her feet. The waves grew louder as she approached the cliffs. Finally, she emerged on the other side of the wood, and followed a dirt path down to the cliff’s edge.

Under the lowering sky, the steel-grey sea and the curve of the headland spread out before her: to the north, ragged cliffs and a rocky outcrop; to the south, the cliffs becoming steeper, the cemetery laid out right to the edge, grey stones stained with black moss and leaning this way and that. Patches of long yellow grass grew here and there, spots of bright colour against the deep wet green. And below her, crashing over and over on to the black rocks, the ever-mobile sea. Her teeth were chattering against each other, but she felt she had never seen anything more beautiful in her life. Suddenly, it seemed worth coming all this way. After following the path that ran along the cliff’s edge for about half an hour, she was desperate to get inside to the heating. Her ears ached and her fingers felt like icy sticks. Still, she dreaded the long evening ahead. Daylight was already dissolving around her and would not emerge again for fifteen hours – longer, if the rain set in. She headed back through the wood and returned to the garden. In a gust of wind, the enormous oak tree shook some brown leaves down upon her, and upon the mossed roof of the cottage. She rested her hand upon the tree trunk, trying to imagine her grandmother performing magic rituals here. Was it possible one could grow fond of a person one had never met? Because that’s how she was starting to feel towards Sybill. Eccentric, psychic, creative Sybill. Her grandmother.

“And for all those years you were kept from me,”

she said softly.

She turned slowly towards the house, then froze in astonishment. A dark shape, a hooded figure, shifted a shadowy reflection in the glass of the laundry window. Worse, it looked as though it were standing just behind her right shoulder. She spun round to check but could see nothing, and when she turned back to the laundry window the apparition was gone. Her heart sped a little, her skin shivered, but she remained rooted to the spot.

What if somebody was in the house? But no, the windows were reflective, not transparent, especially now night had fallen.

Perhaps – perhaps it was the spectre of her grandmother in her ritual cloak. But she had seen the cloak and it was grey, not that dirty brown. And there had been no sense of a warm or eccentric old woman about that apparition. Rather, something elongated and sinister.

No, she must be imagining things. She was still tired, disoriented. It was probably just the reflection of an oak branch bowing in the wind. She walked up to the house and let herself into the laundry. Tabby sat on the washing machine looking at her.

“Was it you, Tabby? Were you trying to frighten me?”

Maybe the cat, maybe a tree, maybe just the product of an overstimulated, overtired mind. It didn’t matter. The house was warm and Tabby needed to be fed. And tonight she would watch television, drink hot tea, listen to the wind buffet the window panes, and enjoy her solitude, her time and space to think about life. And when ten o’clock came and she was tired enough to sleep and had forgotten (almost) about the thing she thought she had seen, she looked up towards the end of the house and saw Tabby sitting on the washing machine, gazing out the laundry window into the back garden. And, just as she did when she guarded a mouse-hole, the cat swished her tail back and forth idly.

As though she were watching for something.

CHAPTER FOUR

Adrian was a good singer and he knew it, but he also knew he was a bad mathematician, which was why he was embarrassed but not surprised when his phone call to Maisie woke her up.

“It’s one in the morning,” she said, and from the other side of the world he heard her yawn.

“I thought it was nine p.m.”

“You have to add two hours then change a.m. to p.m.”

“Ah. I must have subtracted.”

“It doesn’t matter. I’m just glad to hear your voice. It seems like years since I spoke to you.”

He stretched out on the bed. “So, tell me

everything.”

Which she did. About her grandmother the witch, the local Reverend coming to visit, the gardener who told her to beware the tight-knit religious community, her new cat, the view out along the cliff-tops and the vast Solgreve cemetery.

“And are you happy,” he asked, “or are you

homesick?”

“A bit of both. But I’m not coming home. I’m going to tough it out.”

“I know. You can’t let Janet think she’s won.”

“I’m not just here to piss my mother off, Adrian. I’m not that shallow.”

“Sorry.” He changed ears. “Anyway, there

wouldn’t be much point in your coming home just yet. The tour starts next Wednesday, and I’ll be gone until January.”

“You’ll have a wonderful time.”

“I’m sure I will.” There was nothing he loved more than performing in front of an audience, travelling from place to place, being treated like somebody important. Which was the case more and more since the Otello incident.

“I have other news,” he said. “First, the Sydney Morning Herald are interviewing me for the cover of their Good Weekend magazine.”

“Oh, Adrian! That’s fantastic. Make sure you send me a copy.”

“There’s more. Churchwheel’s want me.”

“You’re kidding.”

“Not kidding.” Churchwheel’s was the most

prestigious opera company in the country, a privately run organisation which toured throughout

Australasia and quite often beyond. “I’m looking over the contracts at the moment. I’ll probably be signing up to start with them in February. Can you believe it?”

“Of course I can believe it,” Maisie said. “You’re the best. God, I wish I was there so I could give you a hug. You’re so far away.”

“Too far.” He sighed and rolled over, looked at the picture of them together at her Bachelor of Music graduation three years ago. Her hair had still been long then, all wild black ringlets. He had almost wept the day she cut it all off. “It’s all a bit flat without you here.”

“If you’re joining Churchwheel’s, we’d better get used to being apart.”

“I suppose. Though I could put in a good word for you. Who knows, the next time they need a cellist . . .”

“I don’t want to think about that now. Perhaps I’ll have a change of career when I come back.”

“But what would you do?”

“I don’t know. That’s what I’m here figuring out. I’m supposed to be finding myself.” She yawned. “Though I haven’t the faintest idea where to start looking.”

“I should let you go back to sleep,” he said gently.

“I miss you so much,” she said.

“Me too. Want me to call again tomorrow?”

“Would you? Would you call every day until you go away?”

“Sure,” he said. “I love you, Maisie.”

“I love you too. Bye.”

The phone clicked. He hung up and lay back, looking at the ceiling and daydreaming of crowded concert halls.

“We’re a special community,” Constable Tony Blake was saying to Lester Baines as they leaned against the boot of his car. “We have special needs.”

The Reverend hurried up to them. He had expected to arrive first, but it was taking him longer and longer to get out of bed and dressed at this time of night. It frightened him a little, because it made him aware of how old he grew. He hated being outside in this weather: the black sky, the black icy wind coming off the sea, and the distinctive emptiness of three a.m. lying over the streets.

“Tony,” the Reverend said in what he hoped was a stern voice.

“Reverend,” Tony replied, stepping back from Lester and looking chastened. He was under orders not to get into conversation with the crook. Lester asked so many questions, and the Reverend knew Lester had the kind of mind which could figure things out eventually, given enough snippets of information.

The Reverend turned to Lester. “This is very quick work.”

“I got a call just after I’d seen you. This one’s from Manchester.”

“Well, let’s get him to his final destination, shall we?”

“Her. It’s a lady.”

The Reverend nodded, hoping his distaste wasn’t apparent. A lady. He didn’t like it when the bodies were female. A male body was generic, such a known quantity that he did not think about identity. But a female body was a mystery, full of variables. It made him wonder who she had been.

Lester opened the boot of his car. She was in a bag, but the Reverend could still make out the mounds of her breasts as he peered over the top of the open boot.

“You two get her to the door of the abbey. I’ll have to take her the rest of the way.”

Tony and Lester took an end of the corpse each and lifted simultaneously. It was a sight to make a social worker smile, the crook and the police constable working in such happy co-operation. The Reverend followed as his two assistants carried the body to the iron door which was inset into the remains of one of the abbey spires. It led down into the foundations. He pulled out his keys and unlocked the door, and Tony and Lester took the body in and laid it by the rusty trapdoor. They helped the Reverend to get the trapdoor up, and then turned to observe him expectantly, and, in Lester’s case, curiously.

“Do you put them down there because it’s cold?”

Lester asked, even though he’d asked exactly the same question a dozen times before and never got an answer.

The Reverend ignored the question. “Thank you for your help.”

“Can you manage alone?” Tony asked, sizing up the body against the Reverend’s tiny frame. Clearly the Reverend’s conviction that he was growing old was shared by his colleague.

“Yes. I have to. Tony, pay Mr Baines what he’s due.”