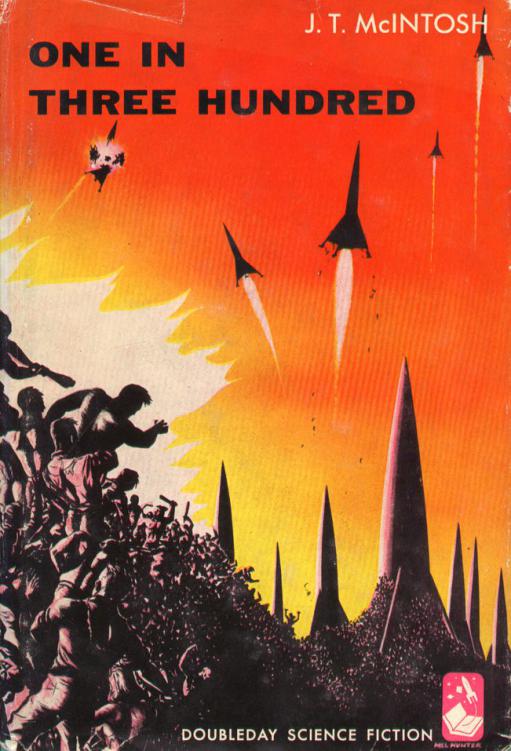

ONE IN THREE HUNDRED

Doubleday Science Fiction

One

in Three Hundred

J. T. McINTOSH

It would have been difficult to find a

more unremarkable man than Lieu-

tenant Bill Easson; straightforward,

conscientious . . . a nice guy. But in

Simsville he was God.

Earth was doomed. And just ten

people out of every 3000 were to he

chosen to start a new colony on Mars.

Each lieutenant hand-picked the ten

he was piloting through space in that

last struggle to survive. Each had not

only the power of life and death; his

choice also determined the kind of

colony that might survive. As the time

grew nearer, violent mobs released

the unbearable tension through may-

hem and murder, and the ten names

on Bill's list changed and changed

again.

Bill Easson knew he had to face

three problems: Stay alive when fa-

natics might destroy him -- their one

chance for life. Get his people out of

Simsville when 2990 men, women,

and children would be ready to kill

them in a last drive for seli-preserva-

tion. And, the most difficult, pilot

those people to Mars in an untested,

hastily built ship when he himself was

inexperienced. The authorities had

given him about a 60 per cent chance

JACKET DESIGN BY MEL HUNTER

BOOK CLUB

EDITION

One in Three Hundred

By J. T. McIntosh

One in Three Hundred

{logo}

Doubleday & Company, Inc.

Garden City, New York

ALL OF THE CHARACTERS IN THIS BOOK ARE FICTITIOUS,

AND ANY RESEMBLANCE

TO ACTUAL PERSONS, LIVING OR DEAD, IS PURELY COINCIDENTAL.

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 54-9186

COPYRIGHT, 1954, BY JAMES MACGREGOR

COPYRIGHT, 1953, 1954, BY FANTASY HOUSE, INC.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES

Contents

One Three Hundred 9

One in a Thousand 63

One Too Many 131

One in Three Hundred

1

I ignored the half-human thing that ran at my heels like a dog crying, "Please! Please! Please!" I ignored it, except when I had to strike its arm from mine, because that was the only thing to do.

I was twenty-eight, Lieutenant Bill Easson, and a more unremarkable young man it would have been difficult to find. But now, through no fault of my own, I was a god.

I'm not going to try to tell the whole story of those last three weeks. That would fill a library. So if you're looking for some big thing you know about and find it isn't even mentioned, or wonder how I'm going to explain this or that, and find I don't, remember I had a job to do and had no time to stand and stare.

When I reached the main street of Simsville (pop. 3261) I was soon rid of the poor wretch at my heels. Two loungers swept him away when they recognized me. I don't know what they did with him. I didn't ask. I never saw him again.

Pat Darrell joined me, automatically. She didn't even say, "Hullo."

A little over two weeks before, when I came to Simsville, she had been the first person to speak to me. "It's all right," she had assured me at once, "I'm just naturally friendly. I don't want what everyone else wants. At least, I don't expect to get it. So you can write that off, for a start."

Naturally I had been suspicious, believing this to be a new play for the same old stake. Everybody wants to live. And what I brought with me, no more and no less, was the power of life and death.

But I had found that Pat meant exactly what she said. She was the most sincere person I ever met. She had come to accept long since the fact that she just wasn't lucky. She never won anything. When she told me this I asked curiously, "Even beauty competitions?"

"Second," she murmured briefly, as if that explained everything. In a way it did.

As we walked, Fred Mortenson favored us with a jaunty wave from the other side of the street. Mortenson was Pat's opposite. He knew he was going to live; it wasn't worth even considering anything else. He had been lucky so often with so many things that there just couldn't be anything wrong this time, the most important of all.

Mortenson was right; so was Pat.

Our choice must be representative, they had told us. No one wanted a new world with everyone exactly the same age, so that in a few years' time there would only be people of forty and young children, and later only old people and youngsters just reaching nubility. So we had been instructed to pick out a representative selection of ten people who seemed to deserve to live.

Our instructions were as casual as that. Some people were never able to grasp the idea. They frowned and talked about psych records and medical histories, and started back in righteous horror when one of us told them what they could do with their records and histories. These people were back-seat drivers. They weren't doing the thing, but of course they knew how it should have been done.

I had decided on my list early, prepared to revise it as various things happened, as they no doubt would. It seemed the best way to work -- I could watch the people I had chosen and confirm their selection or change my mind. The list had changed rapidly in the first few days, but not much since then.

Mortenson was on it. Pat wasn't.

The Powells were on it too, though no one knew that but me. Naturally I kept my plans to myself. We saw the Powells just before we entered Henessy's, and stopped to pass the time of day.

Marjory Powell told me it was a nice day. I agreed gratefully. The Powells, Pat, and Sammy Hoggan were the only people in the village who could treat me as an ordinary human being. Jack Powell was one of those tall, quiet characters with an easy grin. Marjory, without being ugly, was so unbeautiful that she had been able to resign all claims of that kind long ago and concentrate on being a person.

Pat liked them, and so did I. We stood and talked contentedly, and only the knowledge that anyone I spent a lot of time with was marked out for active hatred and jealousy made me take Pat's arm after a few minutes and propel her into the bar.

The Powells didn't seem much affected by the shadow that hung over the world. Their outlook was that the thing was going to come anyway, and they might as well carry on with their usual occupations and hope for the best.

The atmosphere in Henessy's changed perceptibly when we went in. That happened everywhere.

Old Harry Phillips was there, and Sammy Hoggan, inevitably. They waved cheerfully to Pat and me. The others merely glowered, like children told to be on their best behavior and immediately thrown on their worst.

We joined Sammy. Though he had taken the disaster badly, there were a lot of worse ways he might have taken it. He never talked about it. He was going to be drunk for the rest of his life. He was the kind of drinker who merely sat without change of expression and pickled his kidneys.

"Hallo, friends," he said. "O tempora! O mores! Ave atque vale."

"I understood the first two words," Pat admitted cautiously.

"That's all my Latin, honey, so you'll understand anything else I may say."

I was going to buy him a drink, but he begged me not to. "I'm just hoping Henessy doesn't get some sense and realize money doesn't matter any more," he told us. "Because if he doesn't, I'll soon come to the end of this jag. I haven't much money left."

This wasn't surprising, the way he had been drinking ever since I arrived in town. But Pat frowned.

"You want to come to the end of the jag?" she repeated. "Then why don't you stop?"

"To the simple," Sammy sighed, "all things are simple." He killed his drink without noticing it. "No offense, honey. But it's like this. If I'd only had a few dollars on me four weeks ago, I'd only have been able to take a short dive into the rotgut. But I was out of luck. I had enough to keep me going for four weeks."

"Four weeks?" I demanded. "Then . . . ?"

It was seven weeks since it passed beyond doubt that the end of the world, which had been prophesied so often, was really fixed this time. Two weeks and two days since I started the job of picking out the ten people in Simsville who were to live.

With the occasionally uncanny directness of the very drunk, Sammy read my thoughts. "You think I'm drinking because the world's coming to an end?" he asked. He burst out laughing. "God, no. Let it end any time it wants to. Four days now, isn't it? Suits me."

He could talk clearly and soberly when he was sitting down, and raise his glass steadily. But as he got up he was at once obviously very drunk. He staggered away to take some of the weight off his kidneys.

Henessy brought our drinks indifferently. He had no hopes of being one of the ten. He looked on his profession with gloomy disdain. Who would take a bartender to Mars? So, like the Powells, he went on in his own way: business as usual. But I liked the Powells. For some reason I couldn't like Henessy.

Harry joined us. Harry was notable for his craggy features, his fatalistic philosophy, his imperturbability, and his beautiful granddaughter. Bessie Phillips, at eight, was such a lovely child and had such a sunny nature that I hadn't been able to keep her off my list. I couldn't condemn Bessie to death. If I'd been asked to justify every selection (but I wouldn't be), Bessie was the only one I'd have to rationalize about. I could produce reasons, just as anyone else rationalizing can produce reasons, but the real one was simply that I wanted to take Bessie and I could. Some other lieutenant would include an old lady because she looked like his mother. Someone else would have good reasons to explain why he was taking along one particular fourteen-year-old boy and not one of thirty or forty others; the last he'd produce, if he had to produce any, would be that the boy reminded him of the kid brother who died under the wheels of a truck.

Wrong? Sure, if you're still laboring under the idea that the way to do this was selection on the basis of psych records and medical histories, or that the chance of survival should be thrown open to competitive examination.

"Say, Harry," I said. "You know Sammy Hoggan well?"

Harry knew everybody. He nodded, very serious. He knew that whatever he said to me, whatever anyone said to me, might mean life or death for someone. So it was a solemn business talking to me.

It had probably never crossed his mind that he might be one of the ten. When you really came down to it, there were a surprising number of people who took it for granted that they had no right to live, if only a few could survive.

"What's the matter with him?" I asked.

"Thought you knew. His girl left him."

"That all?"

"Son," said Harry seriously, "I've lived a bit longer than you, even if you're the most important man around just now. Never say, 'That all?' about someone's reasons for doing anything. That's only your reaction to the circumstances as you know them, and it means next to nothing."

"Okay," I said. "What was the girl like?"

"No good."

"Because she left Sammy?"

"That among other things. Sammy's a good boy, Bill. You'd like him. It's a pity you've no chance now of knowing what he's like."

Unexpectedly, Pat said something coarse and regrettably audible. One of the unfortunate things about Pat was that she could get completely drunk on a thimbleful of whisky.

One of the others, though it ill becomes me to say it, was that when people called her the unpleasant things people so often call beautiful, reckless girls, they were for once perfectly right.

2

After we'd had another drink or two I decided to go to Havinton, five miles over the hill. Pat wanted to come, but I liked her better sober. She got drunk easily and sobered easily. By the time I got back she'd be all right.

Something was going to happen that afternoon that I wasn't going to like. I had put it off as long as I could. For a while I had thought I was going to be able to put it off until it was too late.

When I first came to Simsville Father Clark came to see me. I'd been told that if I was to co-operate with anyone it should be with ministers of all faiths. We were pretty free; we had little or nothing to do with the police, and nothing at all with other local authorities. But the job the ministers were doing, strangely enough, linked up quite well with ours.

Father Clark was one of those people who are transparently sincere and so humble that you can't help being uncomfortable in their presence and glad to get away. When he said he and Pastor Munch and the Reverend John MacLean would like to have a meeting with me as soon as possible and discuss a few things, I had been vague and managed to avoid fixing a date. There was a solemnity about working together with clergymen of three faiths that reminded me, when I didn't want to be reminded, that I wasn't just Bill Easson any more.

The three men of God were so busy that it was easy for me to keep stalling. Sure, I was shirking my responsibilities. My only excuse was that that was the only responsibility I was consciously shirking. Other lieutenants would have other things to square with their consciences. Men with color prejudices would have to face up to the idea that the catastrophe wasn't a special dispensation to remove all but pure whites from the human race; some lieutenants whose blood crawled at the thought would pick colored men to go to Mars, knowing that if they didn't they would never know peace again. Men who hadn't noticed children for years would realize that there was such a thing as responsibility to young people; the intelligent would discover responsibility for the stupid; and of course all of us were adjusting ourselves to the idea that a baby just out of the womb, a dreamy, clear-skinned boy of eight, a beautiful girl of seventeen, a man in the prime of life, and an old toothless woman were all units in the fantastic new numerology we were using.

Anyway, this responsibility had caught up with me. I was to see the three clergymen later that afternoon. Meantime I'd had enough of being important, so I went to Havinton. In Havinton I was just a man among men. The gods there were Lieutenants Britten, Smith, Schutz, and Hallstead. From which it might be gathered that Havinton was about four times the size of Simsville.

It's difficult to say how much warning we had of the end of the world. The first concrete thing was certainly Professor Clubber's article in the Astronomical Journal two years earlier, in which he said that if and if and if, the sun was going to fry at least the four nearest planets to crisps very soon. But who reads the Astronomical Journal ?

No, it was a year before the possible end of the world was publicized even enough for crackpot cults to spring up -- and God knows that doesn't take much publicity.

The trouble was, at first it was more or less all-inclusive. Not only Earth but Mercury, Venus, Mars, and the asteroids as well. That was as far as any spaceship from Earth had gone so far. Someday someone would land on one of the satellites of the bigger worlds, but not in time to affect this problem. So at first there was no question of any refuge. No preparations were made -- there was nothing to prepare for. And priceless months were wasted.

The sun wasn't going to become a nova, or anything like that. It was only going to burn a little brighter for a while, like an open fire suddenly collapsing on itself and shooting out spurts of flaming hydrogen. Astronomers on distant worlds, if there were any, would have to be advanced indeed before they would change Sol's brightness index as a result of any observations they might be making.

It was such a tiny change, astronomically speaking, which the sun was going to make that one could understand why cults like the Sunlovers started. The first I heard of this group, it was a thousand strong. When I checked on the figure it was three million. A week later there were over a hundred million members of an international Sunlovers' Association.

What the Sunlovers were going to do was just get used to the change before it came. They flowed to the tropics. They found the hottest spots on Earth. The SunA embraced sun bathing, primitivism, nudism, Egyptology, swimming, anything remotely connected with the sun. The SunAs, as they called themselves (pronounced Sunays), soon had a routine in which clothes were ceremoniously torn to pieces and the body was offered to the sun.

Well. But don't let's be hard on the SunAs. Fully ninety-five per cent of them were sane, sensible people -- it was only the extremists who carried out those stunts like walking through fires and burning ice factories and giving birth to children out in the blazing sun and publicly branding their breasts with the SunA sign by sunrays focused though giant magnifying glasses.

Most of the SunAs were people who thought that if they took the step of converting their environment from, say, fur-clad Alaska to bathing-suited Bermuda they would have gone part of the way to being ready for the admittedly tiny increase in radiated solar energy. They didn't get up before dawn to pay their respects to the sun; or if they did, it was out of politeness, not to the Sun God, but to the more fervid SunAs around them.

What the SunAs couldn't or wouldn't understand was that astronomical temperatures, even solar-system temperatures, ranged from -273° C. to 20,000° C., and humanity was only comfortable between 10° and 30°. Certainly people could exist at below-zero and above-blood-heat temperatures. But while nobody wanted to claim accuracy to a degree or two, there was unquestionably going to be no place left on the surface of Earth where water would remain liquid.

Then there were the Trogs, who weren't so much going to get used to the new conditions as run away from them. Basically, if the aim of all the Trog societies must be reduced to its simplest terms, they were going to dig holes in the ground. Oh, certainly some of the Trogs were scientists genuinely planning on survival in a 250°-500° C. world. They were working on a basis of shelter, to equalize temperatures; refrigeration, to convert the energy of heat to the task of keeping a few cubic feet cool; hydroponics, for food and water -- all the obvious things. The only thing was, it was like trying to move a mountain with a wooden spade. It wasn't going to work. Undoubtedly some Trogs were going to live longer than anyone else when the heat really came on, but that was all -- minutes, hours, or days. There just wasn't time to find out how to make a bubble which one could never leave in a 300° C. world and keep it at what had once been normal Earth temperature. Our science was a caveman technology -- we knew about lighting fires and staying warm, but our only solution when there was too much heat was to go somewhere else.

Yes, it was a pity we worked on wrong premises for so long. Until well on in July there was still room for doubt; but then two things were shown conclusively. One was that life would cease on Earth on or about September 18; the other was that Mars, instead of sharing in the disaster, would almost certainly be more habitable after the solar change than before.

It was a double blow. Before that, people could refuse to believe that the world was in any danger. After it, there was the knowledge that some people would live. The law of survival became Mars at Any Price.

A few people who moved quickly enough actually gave themselves life simply by booking passages to Mars. But very soon the survival of the human race was organized. The planners and statisticians got to work. And about their deliberations and premises I know nothing.

The edict was that 1 in 324.7 people could go to Mars. That was pretty damn good, we were told. It could be achieved only by having every machine plant that could possibly be used for the job feverishly producing anything that could prise itself off Earth before it was too late.

Pretty damn good it might be, but it meant that 324 out of every 325 people all over Earth were going to die.

Somehow one person out of every three hundred or so had to be picked out for a chance to live on a strange world. And the job had been given, rightly or wrongly, to the men who were actually to take them to their new home.

There wasn't much time for argument. Friday, September 18, was deadline. For a few hours after noon on Friday the real spaceships, the ships properly built before the heat was on, would be landing and taking away extra cargoes of human beings. But by noon Friday all the rush jobs, the lifeships made in desperate haste for one trip only, would have to be clear of Earth. Otherwise they might as well stay where they were.

So they sent us out -- us, the men and women who happened to be able to handle a ship -- to collect the ten people who would go with each of us.

See what I mean about needing a library for the whole story? The details of how agreement was reached on that point would make a book.

We weren't anything special, the newly appointed gods who had to pick ten people out of 3250 or so. It just so hap- pened that the way to get most people off the Earth was to build thousands of tiny ships into which eleven people could be packed. A little more time, and perhaps mighty ships could have been built, and a different method of selection employed.

Anyone who had any hope of being able to handle a lifeship was given a command. I had been a radio officer on an expeditionary spaceship. At that I had a better background than some of the men and women who were going to try to take lifeships to Mars. Mary Homer, the stewardess on the exploration ship, had a command, I knew.

In the end, of course, the real shortage wasn't of lieutenants but of lifeships. Otherwise they'd have had training schools set up to turn out space pilots in a hurry (normally, it only took five years).

I had been given Simsville, which was just big enough to supply a lifeship complement and no more. I'd never been there before, of course. Lieutenants were invariably sent where they knew nobody.

And four days before takeoff, I had my list of people who were to live.

The Powells. They were Mr. and Mrs. America, Jr. Fred Mortenson, the brash, clean-limbed young hero-to-be. Harry Phillips, who wasn't quite sure it was right for people to go dashing away from the world that had given them life, merely because it was now going to bring them death. Little Bessie Phillips, who didn't know what it was all about (who did?). Miss Wallace, a schoolteacher and a good one. People like her would be needed. The Stowes, Mr. and Mrs. America, Sr., and Jim, their son. Leslie Darby.

Because Leslie was going, Pat would stay. Don't allow for what you think the rest of you are going to do, I'd been told, with all the other lieutenants of lifeships. But it was difficult to escape the idea that there would be plenty of young and beautiful girls on the list for Mars. So I had only one in my ten.

I had only three things to worry about now.

One: staying alive till I left Simsville. There were fanatics now; later there would be disappointed, angry, terrified people who would sink themselves in a mob.

Two: getting my ten away from Simsville. That wouldn't be easy, despite what I'd been told and the arrangements which had been made.

Three: getting my lifeship to Mars. But that, the most difficult and important, was the one which worried me least. That was me and an untested, hastily built ship against space. The others were me against my fellow men.

3

The three clergymen were met together at Father Clark's house when I arrived back in Simsville from my brief holiday in Havinton. As Father Clark ushered me in there was that uneasy silence that comes when a group's frank discussion of someone is interrupted by the arrival of the someone.

The Reverend John MacLean was heavy and blunt. "Let's waste no time, Lieutenant Easson," he said. "You probably think your time's valuable, and I know I think mine is. Will you start the ball rolling, or shall I?"

I sat down and tried to feel at home. "You, I think," I said. "Why do you want to see me, anyway?"

"First," said MacLean briskly, "let's get one thing cleared up. We don't expect -- "

"I know. You don't expect to go, but . . . But what?"

"Isn't that a little unnecessary?" asked Father Clark gently. "I know you must have found it necessary to adopt a defensive, even a suspicious attitude, Lieutenant Easson, but -- "

"Sorry," I said. "Trouble is, it seems years since I could talk to anyone in a straightforward way." I had a good look at them. Cynically I had half expected that they would be squabbling among themselves, but I could see no sign of that.

"That's part of our reason for wanting to talk to you," said Pastor Munch. He was one of those little men with astonishingly deep voices. The room seemed too small to contain his vibrating organ tones. One was inclined not to notice what he said, so fascinating was the sound of it. "You see," he went on, "the three of us here, Lieutenant Easson, feel we are responsible for Simsville. That is our success and our failure. We are not big enough to be responsible for the whole world. We must limit our sphere to be effective. I'm purposely not talking theology -- my point is simply that anything that happens to the people of Simsville happens to us. And anything that is going to happen we must carefully examine and test and if necessary explain to our people."

"Exactly," said MacLean briskly. "You are an instrument of God. Sometimes the phrase has been used as an excuse. Instrument of a higher power. A shrug of the shoulders. Nothing can be done but accept."

He leaned forward and tapped firmly on the arm of my chair. "That attitude is apathy," he declared. "And apathy is anti-God. We feel, all three of us, that it is up to us to examine and test and if necessary explain, as my colleague says, this instrument of God. We can help or impede. Or we can guide."

MacLean's blunt though not unfriendly approach demanded frankness. "You mean," I said, "you can help or impede or guide me .

"There is no question," said Father Clark quickly, "of impeding."

Munch murmured assent, the rumble of a distant avalanche. MacLean said nothing, staring back at me.

"I didn't want this meeting," I admitted, "and I delayed it as long as I could. That was because I was prepared to promise nothing."

MacLean nodded. "You came with your mind made up, in fact," he said.

I nodded too. "Half made up, anyway.

Father Clark almost wrung his hands. He was too kindly to like this kind of plain speaking.

"What did you think," asked MacLean, "that we might ask you to promise?"

"To take all the saints," I said bluntly, "and leave the sinners."

I hadn't noticed Munch's eyes before. They were very soft, brown, very sincere. They met mine and I wasn't quite happy. "Of course you will take the saints," he said, "and leave the sinners. But you did not think, did you, that we should insist that only we knew the difference?"

"I shall take whom I like," I said flatly, "on the basis of my own conscience."

Pastor Munch nodded. "That is what I meant."

MacLean nodded too. "I don't think you've been thinking straight, young man," he told me. "On your main job, yes. Perhaps you have. On the part we would play, no. How could we possibly dictate to you in any way what you should do? It's a waste of time for us to decide what we would have done if things had been different. I've heard about you. I've seen you once or twice. I know you're going to do your best. Therefore you're the best possible instrument, and if I'd had anything to do with your selection I'd have chosen you."

I tried to swallow the lump in my throat, unreasonably ashamed of it. Munch met my eyes again, and his own softened still more.

"We understood your burden," he told me, "but we weren't quite certain that you did. I am glad you do. You must realize its weight before it begins to lighten."

More was said, and I think there were handshakes and blessings and promises of any help I needed. But I don't want to go into that.

These three were not only priests of God; they were good men.

4

I stepped straight from peace into hell.

I had seen signs that made it plain there was going to be trouble in Havinton. For that matter there was going to be trouble everywhere. But in Simsville, with only three thousand population, I had thought I was lucky. A crowd in Simsville -- even a mob, if it became that -- could only contain three thousand people. A mob in Havinton could be thirteen thousand strong -- and that's pretty strong.

But as I reached the town square on the way back to my hotel from Father Clark's house I found things could be pretty bad in Simsville too.

Our first riot was raging in the square. I stood and watched. I was safe, comparatively. No one but a madman was going to harm the one man who could give him life.

There was nothing to indicate the reason for the fight. Probably no one knew it. Frightened people are angry people; and if a man is angry enough, a remark that it might rain is enough to start a fight.

Watching it sickened me. If I'd had any real authority I'd have tried to stop it; but I was nothing, and nobody could stop it. I had no backing. The police were there in the fight -- whether as police or just as contestants I didn't know.

I'd never seen a really dirty brawl. I'd never seen men throw children aside, drag women about by the hair, kick unconscious men in the ribs and stomach, and tear at each other with their nails. I didn't want to see it. I moved to go, and then realized it was still my job to pick ten people out of this rabble. It was part of my job to watch.

Brian Secker had a man I didn't know on the ground and was battering his head on the concrete. That was manslaughter, or very soon would he. Could I take a man I knew to be a killer to Mars? Secker came off the list of improbables and went on the list of impossibles. That was the only punishment I could inflict, and he would never know.

Harry Phillips was in the fight but not of it. He was ignoring mere brutality and doing what little he could to stop anything worse. That was no surprise. I knew Harry. His place on the lifeship was confirmed.

I could see Mortenson on the other side of the battle, but he was fighting with a smile on his lips. To him a fight meant fun, not terror or torture. He fought men his own size. My gaze passed on.

It was a shock to see Jack Powell battering Al Wayman to a pulp. But then I saw Marjory lying unconscious beside them, and turned elsewhere.

I started toward Pat. She was almost hidden by three men. But past her I saw Leslie, trapped in a corner with half a dozen children she had gathered behind her for safety. I went to her instead. The three round Pat were only tearing her clothes, and that was to be expected.

But when I reached Leslie she screamed and pushed me toward Pat.

"They won't hurt her," I said. "She's -- "

"You fool!" Leslie shouted at me. "Look at them not hurting her. Naturally they'll hurt her -- kill her if they can. Haven't you the sense to see that?"

I turned, and then Leslie didn't have to urge me. They were using Pat as a punchball. People who can't defend themselves any more can very soon be punched to death. Particularly women.

I couldn't drag them off. I could only go and show them I was there. They could have killed me. But the knowledge that their only chance of life depended on me sobered them, and they slunk away. Pat was on the ground, unconscious.

I picked her up and took her to Leslie. She was breathing. She would live, no doubt. The children behind Leslie stared.

Pat opened her eyes. "God, what hit me?" she gasped. Then she saw the gaping children behind us. "Turn your backs, kids," she said. "You're too young for this kind of show."

She was hurt less seriously than anyone would have thought.

Leslie pulled her dress over her head and helped me to get it on Pat. "That makes you Exhibit A in the peepshow, Leslie," Pat observed. "Never mind, my need is greater than thine."

The fight was suddenly, for no apparent reason, all but over. People disappeared like snowflakes in the sun.

That was our first fight, and very nearly the worst. People hadn't realized, till then, what could happen when such a fight started among men and women who had only four days to live. They hadn't known that they themselves would be ready to kill, and others to kill them.

Pat couldn't walk, but she was very easy to carry. It was safe now to send the children home. They went with backward glances at us. Already, so little impression had the fight made on them, curious little sniggers passed among them.

As I picked Pat up, I half turned to Leslie, frowning. The kids were giggling as if at a dirty joke, not quite understood. Leslie was a schoolteacher, and perhaps precocious youngsters found prurient amusement in the sight of her dressed like a lurid magazine cover. But I had heard those sniggers before, when Leslie wasn't around.

She read my thoughts. "It's not me," she said with an embarrassed grin that made Pat leer up at me. "It's you."

"Me?" Just in time I stopped myself twisting to see if there was a hole in my pants or something.

"The schools were closed," said Leslie, "because it seemed silly to keep them open. Because teachers couldn't be bothered. Because parents wanted their children with them. But we weren't allowed to tell the children why the schools were closing."

"I know. Mad, of course -- why try to keep it a secret that the world's going to end on Friday?"

Leslie nodded. She was talking very quickly, trying to keep my attention on what she was saying and off her body, I suppose. She needn't have been ashamed of it. It was slight by most standards, but sweet.

"Yes, but don't you see?" she went on rapidly. "We're told not to tell them, so they learn about it from each other, in dark corners, as something shameful. Some parents, of course, are wise, and explain simply. But others run away from the problem and let their children learn the truth as a misty horror . . ."

I could work out the rest for myself. It was foolish to try to hide this new fact of life and death from children; but it was no surprise that people tried it. They forgot, or didn't realize, that while one could conceal facts from children one could never conceal tension. And it centered in me.

I was taking Pat to my hotel, which was quite close. I shrugged off the problem of the children -- I couldn't carry everything. But I remembered something else which had aroused my curiosity even in the middle of the riot.

"What did you mean, Leslie," I asked, "when you said naturally they'd hurt Pat and hadn't I the sense to see that?"

Leslie went red as I looked at her, but it wasn't a blush of embarrassment this time. She said irritably, "Don't be a fool, Bill." She was right. I was a fool. I should have known.

I looked down at Pat. "You know what she's talking about?" I asked, more to get her mind off her bruises than anything else. But Pat didn't know, and said so.

"They knew Pat was sure of a place on the lifeship," Leslie said suddenly, bitterly. "Naturally they wanted to kill her. I can even see their point of view myself."

Pat tried to laugh, but gave it up. "Tell her, Bill," she said weakly.

But it was important that no one should know he was going to Mars, or not going. People could become desperate when they knew there wasn't any chance. Even Pat, despite what she said.

So I said noncommittally, "Nobody's 'sure of his or her place, Leslie. Until Thursday night, when eleven of us leave here, no one knows that he'll go or stay. You can see it must be like that if you only think about it for a minute."

Leslie frowned. We were in the lounge of my suite. I set Pat down on a sofa. "But . . ." Leslie said.

Pat really laughed this time. "Still don't believe it, Leslie?" she said mockingly. "Listen. Bill and I have never discussed this, except when I told him, right away, I didn't expect to be one of the ten. I don't say I want to die -- who does? But if Bill won't tell you straight, I will. He wouldn't take a girl like me to Mars. If he did, he wouldn't be Bill. So I can just carry on being myself without trying to buy myself a place on the ship by being someone else. See?"

Leslie nodded, incredulously. "I'll go and call the doctor," she said. I threw out a shirt and a pair of slacks for her, without a word.

"I'd think more of her if she believed you," I said, frowning, when she had gone.

"Can you expect her to?" Pat asked wryly. "We're always together. We . . ."

But she found talking not worth the effort, and stopped. I thought Pat had come out of the affair better than Leslie, and the frown didn't come off my face. You could judge people by what they believed of others. Was I making a mistake?

Or was Pat, after all, putting up a magnificent bluff, for the highest stakes of all?

5

I had a caller next morning before I was properly awake. Pat, as I had suspected, was tough. She was up and moving about, in a green silk dressing gown of mine, ordering breakfast, and introducing the famous feminine touch to the suite.

She had stayed in the apartment. There was nothing in that. If desperate people wanted to kill her and only I could protect her, it was obvious that she should stay with me. But when I heard the knock I nodded toward the bathroom.

She shook her head definitely. "It's probably only Leslie," she said, without lowering her voice. "Besides, the less openly a thing's done, the more weight people give it. A whiff of my perfume -- and I use very strong perfume, haven't you noticed? -- no sign of me, and it would be settled beyond doubt. Everyone would know you were taking me along."

The truth of the matter was, she just didn't want to hide. She had crossed to the door as she spoke, and opened it.

It was Mortenson. The door hid him for a second or two, so I didn't see his reaction when Pat opened the door to him. By the time he was inside he was taking her presence for granted. Mortenson was never discomposed by anything.

"Say, Bill," he said in his easy, friendly manner. "After what happened yesterday, don't you think you could use some help? I mean, you're all on your own here. Pat doesn't count when the broken glass starts flying. Suppose I move in with you?"

I considered it. There might be times when I'd be glad of Mortenson around. But I knew I was right in having as little as possible to do with the people I had already chosen. The case of Pat proved it, though I hadn't chosen her. Everyone about me was suspect. I didn't want Mortenson, the Powells, Leslie, and Harry Phillips to be found in an alley with knives in their backs.

"Smart, Fred," Pat remarked admiringly. "Just in case Bill hasn't had a chance to appreciate your sterling qualities, you want to hang around and give him the opportunity. You needn't worry. He knows what a great guy you are."

He admitted his motive without a trace of irritation. Mortenson was always easy, friendly, natural. "The thought had crossed my mind," he said. "How about it, Bill?"

"Better not," I said, and explained why, without telling him he was on the list. He nodded. "Reasonable," he admitted. "More than that, you're perfectly right. Announce the names of the ten people who're going with you, and it's the National Bank to one peanut not more than one of your ten would be alive the same night. Say, Pat, if Bill won't take my offer -- when you want to go out and Bill isn't around, give me a ring, will you? I don't pretend I'm crazy about you, but I'd hate to see you after that swan-white neck of yours had had an interview with a meat ax."

Pat shuddered. "You put things so realistically," she said.

Before he went Mortenson warned me that he wouldn't be the last caller I had that morning. "I came early to get in first," he said frankly. "I know Miss Wallace is coming to see you, and the Powells, and Sammy Hoggan -- "

"Sammy!" I exclaimed. "Can he walk?"

"I knew you'd underrate Sammy," said Mortenson, shaking his head. "Nearly twenty-four hours ago he went out flat. Now, apart from a head he'd be glad to sell if anyone would buy it, he's the old Sammy. Suddenly realized the girl wasn't worth it."

Knowing he couldn't leave a better impression by staying longer, he went out and closed the door quietly.

Mortenson was a puzzle -- which meant, of course, that I didn't quite understand him. I can't hope to convey the principal thing about him when you met him -- the impression he gave of being larger than life, of having done and seen everything. He was the man of ten talents. After he had gone one wondered what was so startling about what he had said and done; but one never wondered that at the time.

I looked at Pat quizzically. "You don't like him," I said.

"On the contrary," she retorted flippantly, "I've been in love with him for years. Now and then he's even acknowledged it in passing."

"You don't sound as if you loved him."

"Think hard, Bill. Can you imagine me sounding as if I were in love with anybody?"

That rang the bell. Pat had grown up in a school of life in which the first rule to be learned was: Show your feelings, and someone will slap you down for it.

"You wouldn't like to tell me about it, would you?" I asked.

"There's nothing to tell. What does a lady tell a gentleman about another gentleman?" She was very bitter over the words "lady" and "gentleman." I said nothing, hoping she would fill the silence with words. Presently she did.

"I threw myself at him," she said. "I didn't know any better. But it didn't matter, for he was kind and understanding. He caught me and put me down gently. That's all you can ask of anyone, isn't it? This was when I was seventeen. I tried again, and this time he didn't put me down gently. He held me for quite a while, and when he did put me down it wasn't exactly gentle. By this time he was a little bored with me. I was demanding, you see."

I could hardly imagine Pat being demanding. But maybe I was hearing about a different Pat. Most of us are a lot of different people in the course of our lives.

"Don't blame him," she went on. "Whatever you do, don't blame Fred. That would be unjust." I didn't know whether the irony in her voice was applicable to what she was saying at the time, or just to her life. Her whole life, I thought. "After all, did you duck? Well, the same thing went on happening over and over again. Exactly the same thing. Fred and I meet, as if for the first time, and play the same old broken record."

"Why?" I asked bluntly.

"Easy," she said lightly. "Because that's the nearest I can get to being happy. And because Fred isn't made of asbestos."

She had said all she was going to say on the subject, but I didn't need any more. It was one of those stories that begin: "Things would have been so different if . . ." Maybe they would; what always seems to me to matter is what things are, not what they might have been. But I couldn't help breaking my own rule and wondering if things would have been different if Pat and Sammy had got together, as they obviously never had.

"How come you didn't know about this girl of Sammy's?" I asked.

She shrugged. "Never had much to do with Sammy. He and I started off on the wrong foot a long time ago, I guess." She gave a hard laugh. "It happens with the nicest people sometimes."

We had just finished breakfast when the Powells arrived. They weren't in the least surprised to see Pat, but her presence seemed to bother them. So after a while she went into the back bedroom.

The Powells still had trouble coming to the point. I hoped they weren't going to break down and beg me to take them to Mars because Marjory was going to have a baby, or for any other second-feature reason.

It was Marjory who managed to tell me the reason for their visit at last, though not without more hedging. She was polishing her fingernails very carefully, stopping now and then to pull her perfectly straight skirt straight. "We didn't want to say anything about it," she said, "because we didn't think it would matter anyway, but all the same we felt we ought to -- you understand, don't you? Just in case. It's only fair."

I waited, knowing that anything I said would only be an excuse for more circumlocution -- they would explain in great detail that they didn't mean that.

"I said there wasn't any chance of your picking us," said Marjory, "but Jack said after all, you might. So we thought we'd better tell you not to. Not that it was likely, but -- "

"Why?" I asked bluntly. "You mean you want to die?"

"I mean I can't help it," said Marjory simply. "I'm too great a risk, Bill. I had a miscarriage once and the doctor told me another pregnancy would kill the child and me."

"You think only people who can have children should go?"

"It's more than that, Bill. It didn't seem to matter . . . I'm pregnant now."

"I see," I said.

"Of course you may think we had our nerve thinking you were going to pick us out," said Marjory quickly. "It's not that. It's just that you had to know, in case."

There was nothing for me to say. Could I tell them they had been on the list? Obviously not. Would it make them feel any better if I said they'd never been seriously considered? No. I could only murmur stupidly that I was sorry. It wasn't what I had expected, but it was still second-feature stuff.

Pat came back as soon as the Powells had gone. I told her about them and went on, "I wonder why everybody's chosen this morning to come and tell me these things?"

"Easy enough," Pat replied. "Five people died in the fight yesterday. Twenty-four more went to the hospital. Six were sent to the county jail, to come up in court next Monday. Only there probably isn't going to be a next Monday, so they won't see anything more in their lives but their cells. People suddenly realize that this isn't just a nightmare that will be over tomorrow morning. This is Tuesday. If they haven't convinced you by Thursday night that you ought to take them to Mars, they're going to die."

I was more interested in Pat than in what she said. I remembered that there were now two vacancies for Mars. There was no argument with what Marjory had said. I couldn't give one of those priceless places on my lifeship to someone who might die in a few months or, worse still, become on Mars an invalid who would have to be looked after.

I didn't want to see anyone else. I wanted to sit down and think. But the procession went on.

Miss Wallace had early lost all sign of youth and become ageless. I knew she was only thirty, but she could have passed for forty-five or fifty, if she set her mind to it.

The reason for her visit was to make a plea that Leslie Darby should go.

"You may think she's young and frivolous," said Miss Wallace earnestly (quite unnecessarily, for Leslie was obviously young and no one but Miss Wallace would have thought her frivolous), "but if you haven't seen her with children, take my word for it, she has a very special gift. That will be needed in a new world. Sometimes I'm afraid, Lieutenant Easson -- I hope you don't think this is presumptuous -- that you and other young men like you will build up a Spartan colony -- hard, brave men and women with no time for the softer things of life. Perhaps that is right. Only I feel that the children in such a world will grow up harder and braver still, and a new race will be born that will be cruel and ignorant and -- "

"I don't think any of us want that, Miss Wallace," I told her. I got rid of her soon afterward, for after all she was wasting her time and mine. Leslie was going. So was Miss Wallace, though she seemed to have no thought of that. Besides, I had an uncomfortable feeling her sincerity would weaken me and make me say something I might regret.

"Let's go out," said Pat. "Otherwise everybody in Simsville will come."

"Well, don't you think I ought to see them?"

"You're not their pastor."

"No, but I can give them life in the hereafter."

"That's almost blasphemous," said Pat. It surprised me. I wouldn't have credited her with a clear idea of what blasphemy was, and I'd certainly never have thought she'd be concerned about it.

"Anyway, I'd like to know what's bothering Sammy," I said. "I'm curious to see him sober. I wonder what he wants."

Pat grunted cynically. "He wants a chance to see Mars, of course," she said. "Now that he's wakened up in a world in which he has only three days to live, he's coming to crawl on his belly in front of you."

I didn't like her to speak like that. One moment she had me on the point of giving her Marjory Powell's place. The next she confirmed my belief that that would be a mistake.

Perhaps I took my job too seriously. Perhaps I thought I really was a god.

6

I'd never have guessed in a hundred years why Sammy Hoggan wanted to see me. What had happened to him often happens to people after a hard drinking bout. Suddenly it is all over, they feel like hell, but their brains are ice-cold and emotionless. I've known scientists in such circumstances to come up suddenly, disinterestedly, with the answer to problems that had been bothering them for years.

He came in, walking carefully, as if his head was balanced on a single pin. He was a different Sammy. He looked at me, then at Pat, then back at me.

"I wonder if I should say what I came to say, he murmured.

"Let's hear it."

"Maybe I should keep it to myself, since it doesn't seem to have occurred to anyone else. But it's a disturbing thought, and you might be able to settle it for me. If you can't, I think I'll go back to the rye, for another reason."

"Everybody's evasive," I complained. "Spit it out."

"Can I ask you a few questions?" He lowered himself carefully into a chair. "How long does it take to build a regular spaceship?"

"Nearly a year.

"How many people could the regular ships have taken off while there's still time?"

"I don't know. A few hundred. About one in five million people. What are you getting at?"

"Where's your life ship being built? Have you seen it?"

It should have been obvious what he was thinking, but I didn't see it. Pat did. She caught her breath and looked at Sammy with horror.

"At Detroit. With thousands of others. The whole place has been evacuated and made into a military reservation. Like Philadelphia and Phoenix and Birmingham and Berlin and Omsk and Adelaide. But you know about that. Yes, I've seen the lifeships. They won't be ready until a few hours before takeoff. No trials. Plenty of them won't get near Mars. Is that what you mean? It's not publicized, but anyone who knows the first thing about interplanetary flight can work that out for himself. So?"

"Suppose only one in five million people had a chance of life. What would have happened on Earth?"

"It's not a pleasant thought," I admitted. "That riot yesterday was nothing to what we'd have had, all day and every day, all over the world. But human beings are pretty ingenious when the heat's on. It didn't take long to draw up plans for ships that could be made in eight weeks, when it was really necessary. So what you're visualizing didn't happen."

"Yes," said Sammy quietly. "It didn't happen. Because, as you say, human beings can be pretty ingenious."

I saw at last what he meant, and laughed. He had had me worried.

"You mean that knowing what would happen if only one in five million people could be taken to safety, the high-ups instituted a hoax, to keep the world quiet," I said. "One in three hundred is different. It's an appreciable chance. People won't throw it away. They'll be very careful until they know they've lost it. That's it, isn't it?"

I laughed again. "If there were any real point in it," I went on, "I might begin to believe it. But where's the gain? What would it matter if people all over the world fought and pillaged and looted and murdered? It'll all be the same when the mercury shoots out of the top of all the thermometers."

"There might even be a point," said Sammy. "Who's going in the regular ships? Groups carefully selected -- not by pro tem lieutenants whose only qualification is that they know one end of a spaceship from the other. The real ships are taking the essential people, the equipment, the supplies -- "

"Naturally, when the lifeships are such a gamble."

"More natural still if none of the lifeships are expected to arrive. Perhaps not even to leave Earth. Don't you see what I'm afraid of? The high-up officials knew that if they told the truth everything would be chaos. Mobs would destroy the ships that wouldn't take them to Mars. They'd kill anyone suspected of being chosen to go. When a ship landed, anywhere, a million people would be swarming around it before the ports opened.

"Now see the way it is. The top officials of all governments can carefully, quietly select the people for the colonies, take them to the spaceports, and get them aboard the ships. There may be incidents, but people don't go wild for fear they might lose their chance of a place on a lifeship. See what a smart, hellish scheme it is? The people who are really going to Mars can prepare quietly, without being disturbed, while a third of the population of Earth is occupied building useless lifeships, and the other two thirds are busy behaving themselves and trying to catch some tinpot lieutenant's eye."

Pat was worried. I felt a great respect for her and Sammy. I knew -- I didn't know how, but I knew they were concerned, not for themselves, for neither expected to go to Mars, but for the duped millions who thought they had a chance when (according to Sammy's theory) they had none.

No use to point out that even if it were true there might be something to be said for that method of ensuring that as many as possible of the right people should be taken to the new colony. Pat and Sammy were overcome by the horror of a world kept quiet by a cruel lie. I couldn't see it quite the same way, though it concerned me more than them.

I put my arm around Pat's shoulders.

"I won't argue with your theory, Sammy," I said, "though I could. I'll just say this. When you got that idea -- had you ever been lower in your life? Weren't you miserable, in despair, half dead? Would you admit anything but the blackest, gloomiest thoughts?"

He grinned wryly. "You may have something there."

"Then suppose you get yourself feeling a little happier about things, and then have another look at this idea. It may look a little different."

"Pat wasn't feeling low," Sammy retorted. "And she seems to think there might be something in it."

"Pat thinks there's something in everything. On the surface she refuses to believe anything. But that often hides romanticism and imagination. And who said she isn't feeling low? She thinks she's made a mess of her life. She thinks she has no right to go to Mars. She wishes -- "

Pat jammed her hand against my mouth, hard. I caught her wrists and scuffled mildly with her. She seemed to feel better after that.

Even Sammy almost smiled.

7

While Sammy was still with us the phone rang. Pat took it. She seemed determined that everyone should know she was with me -- though what good that would do her I couldn't see. Quite the reverse. But people who set a lot of store on being honest and outspoken are often honest and outspoken when it does no good and a lot of harm.

The call was for Pat. She listened, slammed down the phone, and turned to us angrily. "Well, what do you know about that!"

"Nothing," said Sammy patiently, "until you tell us."

"That was my aunt. Somebody got into my room last night and destroyed everything -- clothes, books, furniture, letters. The whole shooting match. Imagine anyone doing a thing like that!"

Sammy took the practical view. "Their usefulness has only been shortened by a day or two, anyway," he remarked. "Why should you care?'

"But -- "

"It's just spite," I said. "Why be surprised, Pat? You're cynical about so many things -- it should be no shock that when people hate you they take any small revenge they can."

Pat grinned involuntarily. "No, it isn't really," she admitted. "And as Sammy says, it hardly matters now. But it's pretty petty, isn't it?"

"What an odd juxtaposition," Sammy murmured. "Pretty petty. Pretty petty. Pretty petty."

Pat said she was going over to have a look around. I offered to take her, but surprisingly Sammy stood up and said he'd go with her. He put it neatly, using precisely the words that made any other arrangement impossible. In fact he cut me out. He must have been feeling a whole lot better than when he came in and talked despondency.

There was a knock on the door so soon after they had gone that I thought they had come back. I threw the door open casually, so sure it was Pat and Sammy that anyone else would have surprised me.

But I certainly didn't expect the melodrama of three masked men who brushed past me and shut the door.

I wasn't perturbed. Nothing could happen to me. I wouldn't have been so sure of one stranger, for individuals can be mad enough to kill the only man who can save them. But three -- they couldn't be as mad as that, in the same way, all at once.

"Now what?" I asked. "More particularly, why?"

They all carried guns. The leader drew his and gestured with it, like a schoolboy.

"We mean to go to Mars, Easson," he said, his voice deliberately muffled. "If you get that clear for a start, we'll understand each other better."

"Then you'd better get out before I recognize any of you," I told them. "Otherwise it's very sure none of you will."

"One of us is going to stick beside you until takeoff. We figure that'll make a difference. We -- "

His talking like a cowboy irritated me. For all I knew they might be kids playing a game.

"Get to hell out of here," I told diem, "before I tear your masks off. What kind of a fool do you think I am?"

Nobody moved. So I explained the obvious. "If I die, nobody from Simsville goes to Mars," I said, a little more patiently. "They won't send another lieutenant now. So that won't help you. If you stick beside me as you say, it can only last until we get to Detroit, and then we'll be split. You won't be able to do anything about that. Then I can have you thrown into a cell somewhere and that's that. If you get me to promise anything -- which would be very easy, for I'll say anything you like -- it will last only till I know I'm safe. Then the program's as before. Is that clear?"

I looked from one to another of them. "Okay," I said. "You know where the door is. You just came in.

They went. As easily as that. I gave them credit for having realized before they came that that was probably what would happen. I couldn't really blame them for trying. I might have been weak enough and stupid enough to fall in with their plans. But it was a poor effort.

I'd had enough of my room. I went out to go to Henessy's. I saw the Stowes out with Jim and waved to them. They waved back tentatively. They belonged to the small group who still cared a great deal about what people would think. They didn't want anyone to say they were fawning on me, begging for what everyone wanted.

I saw Betty Glessor and Morgan Smith, who haven't been mentioned so far because I never thought of them. I had exchanged about ten words with them. But they were next on the list to the Powells.

That's what it came to in the end. The more I learned about people, the more likely they were to come off my list. Perhaps Smith was a drinker and a doper and a sadist and a killer -- I hadn't time to find out. I didn't know he was any of these things, so I could take him to Mars.

Tentatively I scratched out the Powells and marked in Smith and Glessor.

Still looking after them, I almost ran into Leslie. She had no job, now that school was closed. She grinned. I stopped, having nothing to say, but no reason to walk past her when she seemed to want to talk.

"What are you doing?" she asked -- a silly question if ever I heard one.

"Just killing time," I said.

"Like me to help you?"

"If you have any bright ideas."

She knew a little place down the valley I hadn't had a chance to see. She said it was a good place to think of when remembering Earth.

It was curious, I'd never thought of that. Perhaps because I'd lived in three country districts and four cities before I was ten, I had never felt any duty to any one place. I hadn't thought much about leaving Earth forever. I had realized vaguely that Harry Phillips would do so with a pang; but if everybody left on Earth was going to die, I was going to leave it without any regrets. What was Earth, anyway? Just a place. Define planets generically, and you had Mars and no loss on the deal that technology couldn't make up in a hundred years or so.

But as Leslie spoke I understood that no other planet would ever be made the same as Earth.

We stopped about two miles from Simsville, and there was no sign anywhere of mankind. Two hills folded in on us, hills thickly wooded. A stream meandered one way, then the other, in its search for lower ground. The clouds were very white and still against an almost tropical blue sky.

I found for the first time that though I had no eye for beauty I could let it sink in and something in me appreciated

Leslie was wearing a watered-silk blue dress, and I could appreciate that too. It darkened her fair hair. I had always liked blue and gold.

"I wish . . ." said Leslie.

We had sat down in the shade, and she was leaning forward, her legs drawn up in front of her, pulling at her ankles.

"What do you wish?" I asked obligingly.

She seemed to have forgotten. "Why was it done like this?" she demanded.

I was disappointed. I had hoped I was getting away from Simsville and my job and its responsibility.

"How can one person get to know over three thousand people in fourteen days?" she went on. "You know you can't. You haven't tried. Oh, I don't say you aren't conscientious. I think you are. If you could have arranged the method of selection, all over the world, how would you have done it?"

I shrugged. "Phone book, I guess."

"How do you mean?"

"Every three hundred and twenty-fifth name."

Leslie caught her breath as if I'd suggested setting fire to a cathedral. "You couldn't!" she exclaimed. "That would be horribly callous."

"Why? It would be fair."

"But this way . . . at least there's a chance. The good, the wise, the clever, the beautiful may come through . . ."

"For God's sake!" I ejaculated, shocked by her lack of understanding. "Do you think that's what we're supposed to do? Take all the crowned heads in our thousands of little arks and ignore the rabble? Intellectual or artistic snobbery is no better than social snobbery. If I had Beethoven and Michelangelo and Napoleon and Madame Curie and Shakespeare and Helen of Troy and St. Peter here in Simsville, do you think I'd pick them?"

"Wouldn't you?" She had lost her horror, and in its place was a vast surprise.

"Suppose I did, what would happen to John Doe? Sure, if Simsville had a genius, I'd consider him. There aren't too many geniuses. But when it's one out of three hundred, we're not going to blot out the average man and woman by taking only the people who would come out at the head of a competitive examination in something or other. I . . ."

I didn't have the eloquence I needed. I knew I was right. I wanted her to see it. But how could I tell her that outstanding people, after all, were only clever dogs that had learned new tricks, and that John Smith was worth quite as much to himself as Shakespeare?

"Let's talk of something else," I said helplessly. "Or better still, not talk at all."

She nodded, hesitated, and then with sudden resolution put her hand to her throat.

Perhaps I was to blame as much as she was. I watched stupidly as she did things to her dress, and then became angry when there was no reason to be. After all, what was wrong in wanting to live? Why shouldn't people try anything and everything?

I knew too much about her, and not enough. If it had been Pat . . . well, if it had been Pat it would have been quite different. All I knew was that Leslie wasn't the kind to give herself casually to a near stranger. And that, instead of improving things, made them worse.

"You brought me here for this?" I asked furiously.

"Suppose I did?" she said defiantly.

I was wildly, unreasonably angry. I was also, quite irrationally, disappointed. "You think you could buy any lieutenant that way?" I demanded. "We could all of us have screen stars and princesses and models every night, no obligation, without having to bother about small-town teachers. What I should do is take you, and strike you off the list."

She became very still. It was all melodramatic, cheap, and stupid. She had been very clumsy in her effort to seduce me, not knowing how it was done. If she had known how to pretend to be in love with me, or at least attracted by me, the cheapness would have gone. But only someone who was ashamed of herself could make the horrible mess Leslie made of it.

"Hadn't you even the sense to see," I said bitterly, "that any of us could have any woman we wanted? Don't you think I've had enough silly offers and proposals? People who promise to do everything I say on Mars, who offer me the equivalent of ten years' salary in whatever currency we use out there, if they have to sweat for twenty years to pay it . . . men who contract to do my killing for me in the colony, help me to set up a state of my own. Damn it, Leslie, isn't it obvious that I must have decided long ago on the only possible thing to do about such proposals -- and that's to leave the people who make them behind?"

"You said . . . something that implied you'd picked me to go."

"Yes, I had."

Her head came up sharply and she laughed in my face. "I heard the same thing often when I was a child," she retorted. "'I was going to give you something, but now I won't.' We all said it. It . . ."

I lunged away from her, back to Simsville. The blue silk dress still lay about her as if she were sitting in a sparkling pool.

8

It was hours, not days now. Very soon the ten who were going with me would be told. Whether they ever reached Mars would depend, among other things, on how well they could conceal their knowledge.

There was another fight in the square. I saw it from my window this time, keeping well hidden, for I didn't want it too definitely known where I was. Nobody wanted to fight, but nobody could help it. Everybody in the town was going to die, except eleven. The temperatures all over Earth were still normal, and the sun looked the same. It seemed incredible that there was nothing to see, hear, or feel.

I looked down from the sun to the square just in time to see Jack Powell die. Someone got him down and crushed his neck with his boot. With a sick feeling I saw it was Mortenson. Mortenson! In that moment something clicked into place and I began to understand Mortenson.

Favored. Fortunate. Strong, good-looking, healthy. He had so many things, how could he help but have everything he wanted? Like the beautiful girl who told him, in effect, and went on telling him, "Do what you like with me -- I love you." People would forgive him for anything. Men liked him, women loved him.

He had hurt Pat. I had known that, but hadn't made any real effort to understand it. She had only talked once about her relations with Mortenson. Of course he had hurt Pat. She had asked for it -- the whole world asked for it. Everybody was ready with forgiveness, eager to pardon the magnificent Mortenson.

In four words: he had too much. He had more than he could handle. Overnurtured, he had gone bad.

I didn't care about the rights and wrongs of the fight, or what had led to Mortenson's snuffing out Jack Powell's life. I would always remember the picture of Mortenson stamping on a man's neck, howling with joy. Mortenson was finished, as far as I was concerned.

Now Marjory would die alone, in sorrow and fear and hate. I would never see her again.

Betty and Morgan appeared, saw what was going on, and ran off down a side street. That was good. They hadn't compelled me to strike them off the passenger list of my lifeship. Sammy was there. He had a gun. Could he have been one of the three masked men? No -- they were fools, and Sammy was no fool. Besides, he had been with Pat. Where was Pat?

I must have said it aloud, for she spoke behind me. "Come away from the window, Bill," she said. "It's like dope. It gets you in the end. You're not tough enough."

I brushed my hand over my eyes. She was right; I didn't really know what was going on. At least, I recorded it faithfully enough, but it didn't mean to me what it should have meant.

The list was complete. Mortenson out, the Powells out, Leslie out. She had done something, I forgot what it was, but I remembered that she was off the list. Miss Wallace, Harry Phillips, Bessie Phillips, the Stowes, Jim Stowe, Betty Glessor, Morgan Smith. But that was only eight. Oh yes, Sammy and Pat.

"Pat," I said. "Did I ever tell you? You're going to Mars."

She wasn't surprised, as I had half thought, and she certainly wasn't delighted. She was very calm and serious.

"You really mean that?" she said.

"Of course. I wouldn't joke about it."

"No. That's what I thought. It's not just that you . . ."

I didn't know what she meant, and probably she didn't either. "It's not just anything," I said. "Of the population of Simsville, I don't know anyone who has more right to live than you."

I hoped it was taken as calmly in each case. I wouldn't know. I wasn't going to tell any of them myself, except Sammy and Pat.

The fight seemed to have stopped, or at least moved somewhere else. There were no shouts or screams as I waited, wondering how the other eight were taking it.

Pastor Munch was visiting the Stowes. That, of course, was the way. I couldn't visit the people I had chosen, I couldn't write or phone or telegraph, and I couldn't send anyone who had been close to me. The three clergymen had offered to help, and this was the way in which they could. No one would interfere with them as they went about visiting people; and I had not been in touch with them often enough or publicly enough for anyone to guess that they were my messengers.

Munch only knew about the Stowes. He hadn't wished to know more.

Father Clark was taking care of Harry Phillips. Harry would be incredulous, I guessed. I had thought all along that, left to himself, he would refuse. But mention of Bessie would shut him up. He would be afraid that if he said anything about himself Bessie might lose her chance.

Miss Wallace was another who might be dumfounded. Father Clark would tell her too.

I didn't know how Betty Glessor and Morgan Smith would react when MacLean told them they were going. They were the gamble of the group. But when it came to couples, one had to gamble. It seemed unfair to give half the available places to one family, but families wouldn't be split. That meant either couples who hadn't started to have their children, like Betty and Smith, or couples with only one child, like the Stowes.

There would be plenty of children on Mars. There always were when life for a group began anew. I would marry, naturally. I looked at Pat.

"Can you tell me now who else is going?" she asked. I told her.

"You've done a good job," she said.

I was inordinately relieved. Pat would know. So I had picked on roughly the right people.

"But . . ." she said, suddenly frowning.

"But what?"

"What about Leslie?" she demanded.

"I always meant to take a cross section. It was always you or Leslie. Not both."

Now she did look surprised. "But why me?"

"Pat, you always had a low opinion of yourself. You were quite right. You're nothing to write home about. Except maybe for your looks. But the sad thing is, other people rate even lower than you. So you go."

"Lower than me?" she murmured, in strange humility. "That's a pity."

The commonplace nature of her comment seemed the funniest thing I had heard for months. I was close to hysteria, and I laughed until I was sore. A pity that people were such heels. A pity that the sun was going to radiate just the fraction more heat that meant the end of all life. A pity that only ten people from Simsville had a chance of life.

Sammy came in. I took control of myself.

"Glad to see you, Sammy," I said. "You're elected. You're going to Mars."

He nodded. He was another who wasn't surprised. "I thought that might happen," he admitted, "now Mortenson's dead."

"Dead?" I exclaimed.

"You didn't know? I thought you'd be watching from the window."

"Who killed him?"

"I did. If you didn't see what he was doing at the time, please don't ask me to describe it. I always had a weak stomach. And Pat?"

"She goes too."

He nodded again. But he was still thinking of Mortenson. "You wouldn't think that even something like this could change people so completely so quickly," he said.

Pat laughed, unaffectedly this time. "You should know better than that, Sammy," she said. "People don't change. Never. They may be changed, or they may reveal themselves, or we may have seen them wrong the first time. That's all."

"Never mind that," I said. "There isn't much time. Listen. You may have heard a rumor that a plane will pick up the selected people at the park."

Sammy nodded. "Well, there will be a plane," I said, "but that's only a blind. The plane is the escort for a helicopter that'll land here in the square about the same time. Everybody should be at the park. The people who mean to make trouble, anyway. The other eight who are going with us will know by now. They just have to get to the square, that's all. They should be safe so long as they don't give themselves away."

Sammy began to make objections, but I waved them aside rather petulantly. "Don't you think I've had time to see what's wrong with the plan in the last few weeks? It isn't mine. Anyway, what else could have been done? Nobody has more than a few hundred yards to go anyway, except the Stowes, and they'll come in their car. I know . . ."

Faintly but clearly we heard a plane.

"It's early," said Sammy.

"No. It's got to fly about and circle so that everyone believes it's the plane they've heard about, and they've only got to see where it lands -- in the park or anywhere else. There's going to be no trouble, Sammy, unless too many people are smart and realize they're being fooled."

"But they've got a pretty good idea where you are."

"That was always the difficulty. We can't do anything about that -- only hope the plane will be a greater attraction."

For long, tense minutes we waited. Then -- because there had to be a little time in reserve -- I got up. "Come on," I said.

The hotel had had no staff for a long time. The manager had no imagination at all, and he clung grimly to his job and his duties. There were no unauthorized people in the hotel.

We got down to ground level without seeing anyone. Naturally no one would come into the hotel, where they might miss us, when they only had to watch the exits.

The plane was still circling. Once or twice we heard it swoop to land, then climb again. The pilots of those planes had a big job. They had to be psychologists as well as heroes -- for, of course, theirs was liable to be a suicide job. Mobs wherever this plan was adopted would tear these pilots to pieces when they learned they were just decoys.

The point was, the people were pretty certain I was at the hotel. Would anything make them leave? Only the conviction that I had somehow eluded them. All I could do about that I had done -- have flares lit at the pavilion, flares that would be visible anywhere in Simsville, and would surely make people think that I was at the park, signaling to the plane. The suspense was the cruelest, most effective part of it. People who at first had been grimly determined to wait in the square in the belief that I must appear there must have felt that belief waver and diminish as the plane swooped and flares lit the sky and people hurried past on their way to the park. The grim watchers must have panicked at the thought: Some of these people must be going to Mars. And here we are watching them go!

We heard the plane actually land. That, I thought, must break the last resistance of anyone who must now guess he had no chance of life on Mars.

We stepped boldly into the square. It was getting dark -- deceptively dark. Even we, expecting it, didn't see the helicopter until it dropped in the square.

There were bodies in the square. It settled among them. I saw Mortenson lying outstretched, his hand straining for a gun he had never reached. He might have lived fifty years more, on another world.

Then shadows moved. We rushed for the helicopter, and I saw Harry Phillips carrying Bessie in his arms, Betty and Morgan running hand in hand.

Then Pat screamed.

Whether Mortenson had been all but dead or merely stunned didn't matter. He wasn't dead, and he had the gun. I saw Sammy go for his to make another try, and knew he would be just too late. Mortenson knew the time he had, and took careful aim. He could have had any of us -- Sammy, who had shot him; or me, without whom no one from Simsville would live, and all would be brought down with Mortenson, who couldn't go himself.

But he chose Pat. Something in his twisted mind made him go for the girl who had loved him.

Mortenson and Pat died together. They were both good, clean shots. There were no last-breath speeches. Pat fell and Mortenson lay still.

I can't explain what I did. I never thought of Pat at all. I merely worked out that Leslie wouldn't be watching the plane, but at home, and I darted across to a phone booth. I dialed and got her at once. "The square, quick," I said, and slammed the phone down. That was all.

9