D Group Days

In the world of British theater, “The London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art” is too much of a mouthful. They just call it LAMDA. When I enrolled there in 1967, LAMDA had been around for a while, but it still had the air of a breakaway, upstart institution. Situated in the unprepossessing neighborhood of Earls Court, the academy was crammed into a musty, three-story gray-brick building, referred to with wistful grandiosity as “The Tower House.” Today LAMDA boasts a sterling reputation with a long list of renowned alumni. But in those days it was the second choice for most young English applicants, far less prestigious than the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art (RADA), its venerable Bloomsbury rival. RADA, after all, had produced Gielgud, Finney, Courtenay, Caine, and Rigg. The best-known fact about the more proletarian LAMDA was that the boisterous Richard Harris had been kicked out of the school for unruly behavior and dirty fingernails.

But for aspiring American actors looking to travel to London for a heavy dose of British academy training, LAMDA was the place. LAMDA, you see, had the D Group. This was a special one-year program offered to fifteen “overseas students,” many of whom had already had a couple of years’ experience in the profession. In a typical year, a dozen of the fifteen D Group kids were Americans. Of that dozen, one actor and one actress were there on a Fulbright grant from the U.S. Government. And that year, I was the Fulbright actor.

The D Group year was a kind of British drama school horse pill. It was LAMDA’s entire three-year curriculum squeezed into one. Our group worked from nine to five every weekday, a regimen as taxing as preseason training in professional sports. Every morning, we would run a gauntlet of intensive classes and every afternoon we would rehearse for one of five productions, spaced out over the year. In my year we performed two plays by Shakespeare and one each by Shaw, Chekhov, and Congreve, directed by a mixed bag of staff teachers and veteran London actors.

Shakespeare, of course, was at the heart of our curriculum. And Shakespeare was spoon-fed to us by an extraordinary teacher named Michael MacOwan. Michael was our Yoda. He was in his late seventies, a stringy little man just over five feet tall, with a booming, gravelly voice seasoned by a lifetime of cigarettes. He was colorful and endearing but prone to crankiness and sudden inexplicable rages. Around the school his quirks and foibles were legendary. In recent years, he had occasionally forgotten where he had parked his car, angrily insisting that it had been stolen. He had been the longtime principal and guiding light of LAMDA, but by the time we arrived he was in semiretirement. His only students were the Shakespearean neophytes of the D Group.

Three times a week, Michael led us in an hour-long scene study class. His teaching method was simple but idiosyncratic. He would assign each of us a speech from Shakespeare. One by one, we would deliver our assigned speech, listen to him hold forth about it, then speak it again. He would grunt and grumble as we spoke, chuckling with pleasure when his notes bore fruit. His head would bob with palsy as he stared intently at each of us in turn, his dark-brown eyes magnified by horn-rimmed spectacles. In his rambling responses to the speeches, he would tease out the meaning, emotion, and music of the verse. He would sprinkle his talk with tales of fabled productions and performances, tossing off nicknames like Larry (Olivier) and Johnny G. (Gielgud) as if they were old friends (which they were). He would educate us in the vast range of Shakespeare’s knowledge, dissecting even the most obscure references, images, and metaphors. And on a Saturday in autumn soon after we started classes, he took us on a field trip to Penshurst, the grand manor house and gardens in Kent. On our way home in the late afternoon, he treated us to supper in a centuries-old country pub. He thrilled us with the fact (or possibly fiction) that the building had once been a hunting lodge belonging to Henry V himself. We arrived back in London after dark, his adoring disciples. The whole glorious day was Michael MacOwan’s notion of a young actor’s education. No one could truly understand Shakespeare, he said, without experiencing the gentle splendor of the English countryside.

Besides the gift of his wisdom, one day Michael did me an enormous favor. The favor was unsolicited and unintended. Indeed he was never even aware of it. A few years before, when he was still LAMDA’s principal, a certain acquaintance of mine had been a member of his teaching staff. This was none other than Tony Boyd, the crazed martinet who had made my life so miserable back in the States during the summer of The Great Road Players. When I learned of Boyd’s tenure at LAMDA, I disingenuously asked Michael about him. Michael wearily shook his head as he answered.

“Tony was a brilliant teacher,” he said. “Very energetic. Very original. The students loved him. But he was a difficult man—chippy and bull-headed. We had a few too many run-ins. It was a messy business. I’m afraid that in the end I had to let him go.”

At these words a wave of relief broke over me. In my mind, I had shouldered all the blame for the Tony Boyd fiasco for two long years. Michael had unwittingly unburdened me. He must have been considerably taken aback when I blurted out, “So did I!”

If Michael MacOwan’s Shakespeare tutorial was the heart of our LAMDA training, the rest of our classes provided its blood, bone, and gristle. These classes included movement, voice, diction, historical dance, choral singing, stage fighting, and even tumbling. Our half dozen teachers ranged across a broad spectrum of English eccentricity. At one end of this spectrum was Elizabeth Wilmer, the prim finishing-school headmistress of a certain age who spent an entire diction class teaching us the difference between the formation of the words “blow” and “blue.” At the other end was B. H. Barry, our furiously energetic young fight instructor (now one of the premier fight arrangers in American theater). In Barry’s class we learned to fence, box, fling each other to the floor, impale each other with knives, and deliver hideously convincing blows to the face, gut, and nape of the neck. Somewhere in the middle of this spectrum was Anthony Bowles, our choral singing teacher. Appropriately nicknamed “Ant,” he was a wiry, febrile little man with a mocking wit who, by some mysterious magic, coaxed sublime close-harmony madrigals from a chorus of young acting students that included not a single decent singing voice.

This wildly varied teaching crew shared a single coordinated mission: to tear us down and build us back up, and to do it with patience, kindness, and good humor. Layer by layer, they peeled away the facile habits and manners that I had accumulated in my short, packed career onstage. In performing Shakespeare I had long ago fallen into a tight, singsong imitation of John Gielgud, probably the result of listening a few times too many to a scratchy LP recording of his Ages of Man. My LAMDA teachers were determined to put an end to this. In voice class I learned to completely relax from my waist up, to reflexively fill up my diaphragm with air, to loosen the tense tangle of muscles in my neck and throat, and to produce an easy, natural sound, more Lithgow than Gielgud. On account of my height I had always tended to unconsciously slouch to the eye level of whomever I was acting with. This question-mark posture constricted not just my body but my voice as well. In movement class, I learned to straighten my spine and stand up to my full height, to vocally stand and deliver.

Finally there was the deceptively simple business of making dramatic sense of what I was saying. Gielgud’s Shakespearean speech favored music over meaning. For all its glories, it was a throwback to a much earlier, near-operatic stage tradition. Under Michael MacOwan’s penetrating gaze, I learned to tilt the balance back toward meaning, to fall a little less in love with the sound of my own voice. He was teaching me lessons that I had spent the last several years ignoring. In his patient prodding, I occasionally heard echoes of my father’s voice back home:

“Just speak the words.”

I loved the D Group. It remains the only formal acting training I’ve ever had. The months I spent in LAMDA classrooms and London theaters were challenging, exciting, formative, and fun. But the LAMDA experience had its distinct drawbacks. It saddled me with two heavy burdens that I would carry with me like twin millstones when I finally joined the American acting profession.

First of all, I became far too English. I had thought that studying acting in the company of a dozen other Yanks would inoculate me from this curious affliction. I thought I could take what I needed from English academy training and then go home with my red-blooded American actor’s identity intact. I was wrong. Osmosis, it turns out, is a powerful thing. I came home with a fruity British accent that I didn’t even realize I had acquired, complete with lilting inflections and arch locutions. Old friends would look at me askance when I’d chirp “Bob’s your uncle,” “spend a penny,” or “a bit how’s yer father.” My own sister Robin wouldn’t speak to me until I dropped “that awful English accent!”

“Wot acksnt?” I asked, puzzled.

She refused to answer.

I was . . . well, gobsmacked.

For my first year back in the States, I emanated Englishness like cheap cologne. At the end of that year I was subjected to a kind of radical therapy that finally purged it from my system. I was cast as Andy in Neil Simon’s trifling sixties comedy The Star-Spangled Girl, in a summer-stock production at the Bucks County Playhouse in New Hope, Pennsylvania. I have long since forgotten the name of the show’s director, an unsurprising memory lapse since he barely directed it at all. But during rehearsals he taught me an invaluable lesson. I failed to appreciate it at the time. Indeed, I bridled against it. But it was just what I needed.

In the play, Andy is a sanitized, Simonized hippie, the youthful editor of a radical San Francisco magazine. The boy is an American—“an American, dammit!”—and my director was determined to rid me of any trace of an English accent in the role. As we rehearsed, he sat behind a table with a tiny bell in front of him. Every time he heard the slightest English inflection from me he would ring the bell. In the first few days of work he was ringing that damned bell every ten seconds. It was absolutely infuriating. I couldn’t believe that, a year after coming back from England, I still sounded that English. But by the last rehearsal, the bell had stopped ringing. The show was godawful and I was pretty dreadful in it. But I was an American again. I was cured.

The second problem was not so easily remedied. LAMDA turned me into an insufferable Shakespeare snob. Until I went off to England, American productions of Shakespeare’s plays had suited me just fine. I had loved to act in them and I had loved to watch them. They were my birthright, after all, and my father’s abiding passion. I had adored their reckless energy, broad comedy, and high spirits. By the late 1960s, the American style was virtually defined by Joseph Papp’s free Shakespeare at the outdoor Delacorte Theater in New York’s Central Park. I had always savored every visit to the Delacorte, a pastoral oasis in the midst of a clamorous city. My heart had swelled at the populist spirit of those shows, with their raucous, grateful audiences and their tossed salad of acting styles, accents, and ethnicities. The crowds never seemed to understand half of the lines (and, for that matter, neither did a lot of the actors). But it didn’t matter. This was Shakespeare at its most joyful and exuberant.

England dulled my enthusiasm for it. My taste was now defined by everything I had seen and done over there. For me, the bar had been set impossibly high. Oh, certainly I had seen plenty of bad Shakespeare in London and Stratford. Some productions were stagey and predictable, some woefully misconceived. But the good ones had been amazing—Peter Brook’s Lear and Midsummer Night’s Dream, John Barton’s panoramic Troilus and Cressida, Clifford Williams’ daring all-male As You Like It. And no matter how good or bad the productions were, the standard of acting had always been uniformly high. There are at least a dozen characters in every Shakespeare play, so every production requires at least that many actors capable of handling the particular challenge of Shakespearean speech. To my overly trained ear, half the actors in every American production of Shakespeare were either miscast or inept.

This was ridiculous, of course. English actors were just as judgmental of their own countrymen as I was of mine (remember my snotty friend’s contempt for Lord Olivier?), and they tended to be far more tolerant than I of Americans playing Shakespeare. Shortly after I returned to the States, CBS televised A. J. Antoon’s brilliant Central Park production of Much Ado About Nothing, set in Teddy Roosevelt’s small-town America. When the BBC aired the show in England, it caused a sensation. All those Brits were delighted to see that old Shakespearean chestnut completely reimagined, with all the freshness, energy, and innocence of its all-American cast.

I loved that production too, but from my high horse I regarded it as the rare exception to the rule. In my view, American Shakespeare just didn’t cut it. In hindsight, I suspect that this arrogance was probably colored by an Oedipal reaction to my father’s long history with Shakespeare and by my unconscious desire to break free of it. True or not, it is an arrogance that has only slightly diminished over the years. It is one explanation for a surprising fact: after appearing in some twenty Shakespeare plays in my first twenty years, I appeared in only two in the following thirty-five. These two productions (the last in 1975) were arguably the worst shows of my professional career. This was all the evidence I needed to support my Anglophiliac bias. Over the years, I have turned down a long list of stupendous Shakespearean roles, among them Angelo, Bottom, Falstaff, Hamlet, Prospero, and Lear. Listing them fills me with wistfulness and regret. But I couldn’t help it. My snobbery made me do it.

Perhaps all of this will explain why I finally returned to Shakespeare a few years ago, at the age of sixty-two. After spurning all those job offers for three decades, I finally received an offer I couldn’t refuse. In the summer of 2007, the Royal Shakespeare Company invited me to come back to England and join them for three months at Stratford-on-Avon. They asked me to play Malvolio in Twelfth Night, to reprise the role I’d played as a teenager in Ohio all those years ago, in junior high school assemblies and National Forensic League meets. This was my chance to tread the very boards where I had seen Judi Dench as Hermione, Helen Mirren as Cressida, Kenneth Branagh as Berowne, and where, in its most recent season, Patrick Stewart had played Antony and Ian McKellen had unveiled his King Lear. Forty years after my full-immersion Shakespeare training, here was a chance to finally put it to work. And, more significantly, Malvolio at Stratford was the perfect way for me to memorialize my father, three years after his death.

I took the job in a heartbeat.

And so began my Twelfth Night adventure, the most intense déjà vu experience I’ve ever had. On a morning in mid-July, I showed up for London rehearsals at the RSC studios in South Clapham and entered a dreamlike time warp right out of science fiction. Forty years had wrought vast changes in me, but England in 2007 was far more similar than different. And so was the business of putting on plays. From the outset, I felt as if I were reliving an earlier chapter of my own life. The morning tube rides, the drafty rehearsal rooms, the yoga mats, the rehearsal skirts, the chatty green room, the sugary tea, the pints at the pub, and the impulsive evening dashes to West End shows—all of it brought back the sights, sounds, and smells of my days as a young drama student in London, unburdened by the humbling weight of years.

We rehearsed for six weeks in South Clapham before moving up to Stratford, led by our endearing, exotic, comfortably camp director, Neil Bartlett. The first several days of work were given over to exercises, theater games, and improvisations, many of them conducted by RSC voice teachers and movement coaches. For the first two weeks, barely a minute was spent on the play itself. The days virtually duplicated my old LAMDA regimen. It was as if I had never left the place. This was not exactly good news. I began to secretly wonder why I had ever taken the job—wasn’t I a little old for drama school? But if the rehearsals smacked of theatrical boot camp, none of the other company members seemed to mind. Most of them were terrifically talented young actors, willing and eager to try anything. But even the old-timers were game for whatever Neil threw at them. Bit by bit, they brought me around. Neil’s work started to pay off, and my doubts evaporated. I realized that this was exactly what I’d signed up for. Our cast evolved into a strong, sprightly, mutually responsive ensemble, worthy of the company that had hired us. And at last we were ready for Shakespeare.

Twelfth Night at Stratford was a glorious time for me. During the run of the show, I lived in a tiny row house in Stratford’s “New Town,” two blocks from Shakespeare’s burial place, in Holy Trinity Church. Every day I strolled around town, nostalgically retracing my footsteps from a dozen visits, forty years before. After every show I caroused with the cast at The Dirty Duck, the RSC’s traditional pub of choice. I rented an ancient Morris sedan and spent free afternoons idly exploring the quaint towns and rolling countryside of the English Midlands. I hosted friends, family, and Brit actor pals who trekked up to Stratford to see the play. I even engineered a sentimental sibling reunion with my brother and two sisters, complete with Cotswold picnics, midnight suppers, tipsy reminiscences, and maudlin toasts to our mother and to the memory of our dear, departed dad.

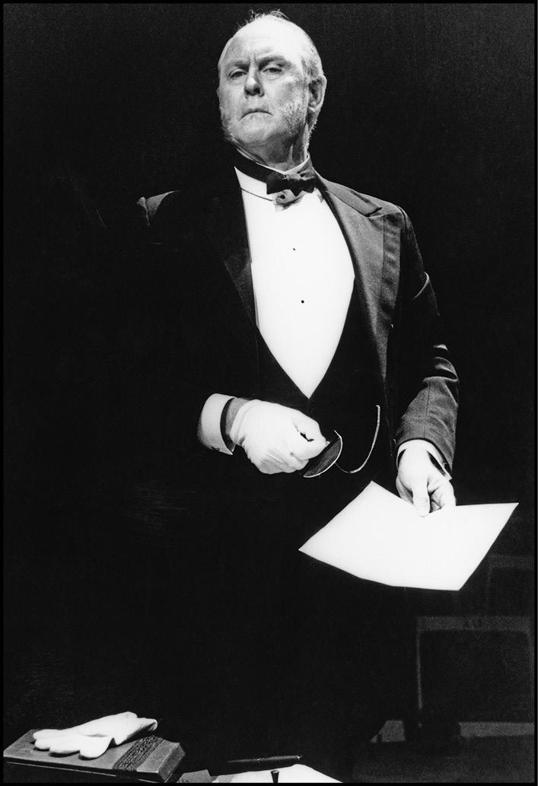

Malcolm Davies Collection © Shakespeare Birthplace Trust.

And the production itself? I was crazy about it. Neil had chosen to set Twelfth Night in a late-nineteenth-century Gosford Park kind of world. The severe black dresses, swallowtail coats, top hats, and starched collars of the period created an atmosphere of constriction from which the play’s sexual energy and drunken high jinks strained to break free. The comedy was there, of course, but it was shot through with anxiety and pain. As a result, the longing and melancholy of the characters had an unexpected depth. I loved working in these dark colors. Neil’s concept made Malvolio into a stern, dictatorial Edwardian butler, obsessed with protocol and coldly ambitious, a character torn from the pages of Trollope. I embraced this portrait wholeheartedly. My Malvolio was arrogant, judgmental, and sexually repressed, but with a prurient fantasy life. I had little trouble unearthing such strains, buried in my own Puritan nature. When Malvolio is gulled into giving vent to his fettered passions, the moment is wildly comic. But in our version, the joke went much too far. By the end, he had become a broken, vengeful creature, a figure of both pity and danger. Calibrating the stages of this complex comic story was, for me, a fascinating process with a thrilling payoff. After we opened, posters and ads for the production trumpeted a quote from Charles Spencer, the exacting critic from the Daily Telegraph. It proclaimed that “the American actor John Lithgow turns out to be one of the greatest Malvolios I have ever seen.”

Every actor savors a rave review, of course. But the Twelfth Night experience led to another tribute that I prize even more. By tradition, one of the rooms in The Dirty Duck is informally set aside for actors currently in residence at the RSC. Displayed on the walls of this room are fifty or sixty signed black-and-white photographs. These are portraits of the major actors and actresses who have performed with the company over the last few generations. The photos range from faded, yellowing shots of the young Michael Redgrave and Peggy Ashcroft to more recent glossies of Jeremy Irons, Miranda Richardson, and Ralph Fiennes. Toward the end of my run in Stratford, the owner of The Duck drew me aside and asked me for a signed picture to hang with the others. I was ecstatic. Next morning I urgently sent home for a photo. It arrived the day before we closed. I signed it and ran it over to the pub. I haven’t been back to Stratford since, but I’ve left my mark: mine is the only photograph of an American actor to grace the walls of the Actors’ Bar at The Dirty Duck.