TWO

Beginning with

an Ending

George

The month the persecutions stop marks the twentieth anniversary of Shapurji Edalji’s appointment to Great Wyrley; it is followed by the twentieth—no, the twenty-first—Christmas celebrated at the Vicarage. Maud receives a tapestry bookmark, Horace his own copy of Father’s Lectures on St. Paul’s Epistle to the Galatians, George a sepia print of Mr. Holman Hunt’s The Light of the World with the suggestion that he might hang it on the wall of his office. George thanks his parents, but can well imagine what the senior partners would think: that an articled clerk of only two years’ standing, who is trusted to do little more than write out documents in fair copy, is hardly entitled to make decisions about furnishing; further, that clients come to a solicitor for a specific kind of guidance, and might well find Mr. Hunt’s advertisement for a different kind distracting.

As the first months of the new year pass, the curtains are parted each morning with the increased certainty that there will be nothing but God’s shining dew upon the lawn; and the postman’s arrival no longer causes alarm. The Vicar begins to repeat that they have been tested with fire, and their faith in the Lord has helped them endure this trial. Maud, fragile and pious, has been kept in as much ignorance as possible; Horace, now a sturdy and straightforward sixteen-year-old, knows more, and will privately confess to George that in his view the old method of an eye for an eye is an unimprovable system of justice, and that if he ever catches anyone tossing dead blackbirds over the hedge, he will wring their necks in person.

George does not, as his parents believe, have his own office at Sangster, Vickery & Speight. He has a stool and a high-top desk in an uncarpeted corner where the access of the sun’s rays depends upon the goodwill of a distant skylight. He does not yet possess a fob watch, let alone his own set of law books. But he has a proper hat, a three-and-sixpenny bowler from Fenton’s in Grange Street. And though his bed remains a mere three yards from Father’s, he feels the beginnings of independent life stirring within him. He has even made the acquaintance of two articled clerks from neighbouring practices. Greenway and Stentson, who are slightly older, took him one lunchtime to a public house where he briefly pretended to enjoy the horrible sour beer he paid for.

During his year at Mason College, George paid little attention to the great city he found himself in. He felt it only as a barricade of noise and bustle lying between the station and his books; in truth, it frightened him. But now he begins to feel more at ease with the place, and more curious about it. If he is not crushed by its vigour and energy, perhaps he will one day become part of it himself.

He begins to read up on the city. At first he finds it rather stodgy stuff, about cutlers and smiths and metal manufacture; next come the Civil War and the Plague, the steam engine and the Lunar Society, the Church and King Riots, the Chartist upheavals. But then, little more than a decade ago, Birmingham begins to shake itself into modern municipal life, and suddenly George feels he is reading about real things, relevant things. He is tormented to realize that he could have been present at one of Birmingham’s greatest moments: the day in 1887 when Her Majesty laid the foundation stone of the Victoria Law Courts. And thereafter, the city has arrived in a great rush of new buildings and institutions: the General Hospital, the Chamber of Arbitration, the meat market. Money is currently being raised to establish a university; there is a plan to build a new Temperance Hall, and serious talk that Birmingham might soon become a bishopric, no longer under the see of Worcester.

On that day of Queen Victoria’s visit, 500,000 people came to greet her, and despite the vast crowd there were neither disturbances nor casualties. George is impressed, yet also not surprised. The general opinion is that cities are violent, overcrowded places, while the countryside is calm and peaceable. His own experience is to the contrary: the country is turbulent and primitive, while the city is where life becomes orderly and modern. Of course Birmingham is not without crime and vice and discord—else there would be less of a living for solicitors—but it seems to George that human conduct is more rational here, and more obedient to the law: more civil.

George finds something both serious and comforting in his daily transit into the city. There is a journey, there is a destination: this is how he has been taught to understand life. At home, the destination is the Kingdom of Heaven; at the office, the destination is justice, that is to say, a successful outcome for your client; but both journeys are full of forking paths and booby traps laid by the opponent. The railway suggests how it ought to be, how it could be: a smooth ride to a terminus on evenly spaced rails and according to an agreed timetable, with passengers divided among first-, second- and third-class carriages.

Perhaps this is why George feels quietly enraged when anyone seeks to harm the railway. There are youths—men, perhaps—who take knives and razors to the leather window straps; who senselessly attack the picture frames above the seats; who loiter on footbridges and try to drop bricks into the locomotive’s chimney. This is all incomprehensible to George. It may seem a harmless game to place a penny on the rail and see it flattened to twice its diameter by a passing express; but George regards it as a slippery slope which leads to train wrecking.

Such actions are naturally covered by the criminal law. George finds himself increasingly preoccupied by the civil connection between passengers and the railway company. A passenger buys a ticket, and at that moment, with consideration given and received, a contract springs into being. But ask that passenger what kind of contract he or she has entered into, what obligations are laid upon the parties, what claim for compensation might be pursued against the railway company in case of lateness, breakdown or accident, and answer would come there none. This may not be the passenger’s fault: the ticket alludes to a contract, but its detailed terms are only displayed at certain main-line stations and at the offices of the railway company—and what busy traveller has the time to make a diversion and examine them? Even so, George marvels at how the British, who gave railways to the world, treat them as a mere means of convenient transport, rather than as an intense nexus of multiple rights and responsibilities.

He decides to appoint Horace and Maud as the Man and Woman on the Clapham Omnibus—or, in the present instance, the Man and Woman on the Walsall, Cannock & Rugeley Train. He is allowed to use the schoolroom as his law court. He sits his brother and sister at desks and presents them with a case he has recently come across in the foreign law reports.

“Once upon a time,” he begins, walking up and down in a way that seems necessary to the story, “there was a very fat Frenchman called Payelle, who weighed twenty-five stones.”

Horace starts giggling. George frowns at his brother and grips his lapels like a barrister. “No laughter in court,” he insists. He proceeds. “Monsieur Payelle bought a third-class ticket on a French train.”

“Where was he going?” asks Maud.

“It doesn’t matter where he was going.”

“Why was he so fat?” demands Horace. This ad hoc jury seems to believe it may ask questions whenever it likes.

“I don’t know. He must have been even greedier than you. In fact, he was so greedy that when the train pulled in, he found he couldn’t get through the door of a third-class carriage.” Horace starts tittering at the idea. “So next he tried a second-class carriage, but he was too fat to get into that as well. So then he tried a first-class carriage—”

“And he was too fat to get into that too!” Horace shouts, as if it were the conclusion to a joke.

“No, members of the jury, he found that this door was indeed wide enough. So he took a seat, and the train set off for—for wherever it was going. After a while the ticket collector came along, examined his ticket, and asked for the difference between the third-class fare and the first-class fare. Monsieur Payelle refused to pay. The railway company sued Payelle. Now, do you see the problem?”

“The problem is he was too fat,” says Horace, and starts giggling again.

“He didn’t have enough money to pay,” says Maud. “Poor man.”

“No, neither of those is the problem. He had money enough to pay, but he refused to. Let me explain. Counsel for Payelle argued that he had fulfilled his legal requirements by buying a ticket, and it was the company’s fault if all the train doors were too narrow for him except the first-class ones. The company argued that if he was too fat to get into one kind of compartment, then he should take a ticket for the sort of compartment he could get into. What do you think?”

Horace is quite firm. “If he went into a first-class compartment, then he has to pay for going into it. It stands to reason. He shouldn’t have eaten so much cake. It’s not the railway’s fault if he’s too fat.”

Maud tends to side with the underdog, and decides that a fat Frenchman comes into this category. “It’s not his fault he’s fat,” she begins. “It might be a disease. Or he may have lost his mother and got so sad he ate too much. Or—any reason. It wasn’t as if he was making someone get out of their seat and go into a third-class compartment instead.”

“The court was not told the reasons for his size.”

“Then the law is an ass,” says Horace, who has recently learned the phrase.

“Had he ever done it before?” asks Maud.

“Now that’s an excellent point,” says George, nodding like a judge. “It goes to the question of intent. Either he knew from previous experience that he was too fat to enter a third-class compartment and bought a ticket despite this knowledge, or he bought a ticket in the honest belief that he could indeed fit through the door.”

“Well, which is it?” asks Horace, impatiently.

“I don’t know. It doesn’t say in the report.”

“So what’s the answer?”

“Well, the answer here is a divided jury—one for each party. You’ll have to argue it out between you.”

“I’m not going to argue with Maud,” says Horace. “She’s a girl. What’s the real answer?”

“Oh, the Correctional Court at Lille found for the railway company. Payelle had to reimburse them.”

“I won!” shouts Horace. “Maud got it wrong.”

“No one got it wrong,” George replies. “The case could have gone either way. That’s why things go to court in the first place.”

“I still won,” says Horace.

George is pleased. He has engaged the interest of his junior jury, and on succeeding Saturday afternoons he presents them with new cases and problems. Do passengers in a full compartment have the right to hold the door closed against those on the platform seeking to enter? Is there any legal difference between finding someone’s pocketbook on the seat, and finding a loose coin under the cushion? What should happen if you take the last train home and it fails to stop at your station, thereby obliging you to walk five miles back in the rain?

When he finds his jurors’ attention waning, George diverts them with interesting facts and odd cases. He tells them, for instance, about dogs in Belgium. In England the regulations state that dogs have to be muzzled and put in the van; whereas in Belgium a dog may have the status of a passenger so long as it has a ticket. He cites the case of a hunting man who took his retriever on a train and sued when it was ejected from the seat beside him in favour of a human being. The court—to Horace’s delight and to Maud’s dissatisfaction—found for the plaintiff, a ruling which meant that from now on if five men and their five dogs were to occupy a ten-seated compartment in Belgium, and all ten were the bearers of tickets, that compartment would legally be classified as full.

Horace and Maud are surprised by George. In the schoolroom there is a new authority about him; but also, a kind of lightness, as if he is on the verge of telling a joke, something he has never done to their knowledge. George, in return, finds his jury useful to him. Horace arrives quickly at blunt positions—usually in favour of the railway company—from which he will not be budged. Maud takes longer to make up her mind, asks the more pertinent questions, and sympathizes with every inconvenience that might befall a passenger. Though his siblings hardly amount to a cross section of the travelling public, they are typical, George thinks, in their almost complete ignorance of their rights.

Arthur

He had brought detectivism up to date. He had rid it of the slow-thinking representatives of the old school, those ordinary mortals who gained applause for deciphering palpable clues laid right across their path. In their place he had put a cool, calculating figure who could see the clue to a murder in a ball of worsted, and certain conviction in a saucer of milk.

Holmes provided Arthur with sudden fame and—something the England captaincy would never have done—money. He bought a decent-sized house in South Norwood, whose deep walled garden had room for a tennis ground. He put his grandfather’s bust in the entrance hall and lodged his Arctic trophies on top of a bookcase. He found an office for Wood, who seemed to have attached himself as permanent staff. Lottie had returned from working as a governess in Portugal and Connie, despite being the decorative one, was proving an invaluable hand at the typewriter. He had acquired a machine in Southsea but never managed to manipulate it with success himself. He was more dextrous with the tandem bicycle he pedalled with Touie. When she became pregnant again, he exchanged it for a tricycle, driven by masculine power alone. On fine afternoons he would project them on thirty-mile missions across the Surrey hills.

He became accustomed to success, to being recognized and inspected; also to the various pleasures and embarrassments of the newspaper interview.

“It says you are a happy, genial, homely man.” Touie was smiling back at the magazine. “Tall, broad-shouldered and with a hand that grips you heartily, and, in its sincerity of welcome, hurts.”

“Who is that?”

“The Strand Magazine.”

“Ah. Mr. How, as I recall. Not one of nature’s sportsmen, I suspected at the time. The paw of a poodle. What does he say of you, my dear?”

“He says . . . Oh, I cannot read it.”

“I insist. You know how I love to see you blush.”

“He says . . . I am ‘a most charming woman.’ ” And, on cue, she blushed, and hurriedly changed the subject. “Mr. How says, that ‘Dr. Doyle invariably conceives the end of his story first, and writes up to it.’ You never told me that, Arthur.”

“Did I not? Perhaps because it is as plain as a packstaff. How can you make sense of the beginning unless you know the ending? It’s entirely logical when you reflect upon it. What else does our friend have to say for himself?”

“That your ideas come to you at all manner of times—when out walking, cricketing, tricycling, or playing tennis. Is that the case, Arthur? Does that account for your occasional absent-mindedness on the court?”

“I might have been putting on the dog a little.”

“And look—here is little Mary standing on this very chair.”

Arthur leaned over. “Engraved from one of my photographs—there, you see. I made sure they put my name underneath.”

Arthur had become a face in literary circles. He counted Jerome and Barrie as friends; had met Meredith and Wells. He had dined with Oscar Wilde, finding him thoroughly civil and agreeable, not least because the fellow had read and admired his Micah Clarke. Arthur now reckoned he would run Holmes for not more than two years—three at most, before killing him off. Then he would concentrate on historical novels, which he had always known were the best of him.

He was proud of what he had done so far. He wondered if he would have been prouder had he fulfilled Partridge’s prophecy and captained England at cricket. It was quite clear this would never happen. He was a decent right-hand bat, and could bowl slows with a flight that puzzled some. He might make a good all-round MCC man, but his final ambition was now more modest—to have his name inscribed in the pages of Wisden.

Touie bore him a son, Alleyne Kingsley. He had always dreamed of filling a house up with his family. But poor Annette had died out in Portugal; while the Mam was as stubborn as ever, preferring to stick in her cottage on that fellow’s estate. Still, he had sisters, children, wife; and his brother Innes was not far away at Woolwich, preparing for an army life. Arthur was the breadwinner, and a head of the family who enjoyed dispensing largesse and blank cheques. Once a year he did it formally, dressing as Father Christmas.

He knew the proper order should have been: wife, children, sisters. How long had they been married—seven, eight years? Touie was all anyone could possibly want in a wife. She was indeed a most charming woman, as The Strand Magazine had noted. She was calm and had grown competent; she had given him a son and daughter. She believed in his writing down to the last adjective, and supported all his ventures. He fancied Norway; they went to Norway. He fancied dinner parties; she organized them to his taste. He had married her for better for worse, for richer for poorer. So far there had been no worse, and no poorer.

And yet. It was different now, if he was honest with himself. When they had met, he had been young, awkward and unknown; she had loved him, and never complained. Now he was still young, but successful and famous; he could keep a table of Savile Club wits interested by the hour. He had found his feet, and—partly thanks to marriage—his brain. His success was the deserved result of hard work, but those themselves unfamiliar with success imagined it the end of the story. Arthur was not yet ready for the end of his own story. If life was a chivalric quest, then he had rescued the fair Touie, he had conquered the city, and been rewarded with gold. But there were years to go before he was prepared to accept a role as wise elder to the tribe. What did a knight errant do when he came home to a wife and two children in South Norwood?

Well, perhaps it was not such a difficult question. He protected them, behaved honourably, and taught his children the proper code of living. He might depart on further quests, though obviously not quests which involved the saving of other maidens. There would be plenty of challenges in his writing, in society, travel, politics. Who knew in what direction his sudden energies would take him? He would always give Touie whatever attention and comfort she could need; he would never cause her a moment’s unhappiness.

And yet.

George

Greenway and Stentson tend to hang about together, but this does not bother George. At lunchtime he has no desire for the tavern, preferring to sit under a tree in St. Philip’s Place and eat the sandwiches his mother has prepared. He likes it when they ask him to explain some aspect of conveyancing, but is often puzzled by the way they go off into secretive spurts about horses and betting offices, girls and dance-halls. They are also currently obsessed with Bechuana Land, whose chiefs are on an official visit to Birmingham.

Besides, when he does hang about with them, they like to question a fellow and tease him.

“George, where do you come from?”

“Great Wyrley.”

“No, where do you really come from?”

George ponders this. “The Vicarage,” he replies, and the dogs laugh.

“Have you got a girl, George?”

“I beg your pardon?”

“Some legal definition you don’t understand in the question?”

“Well, I just think a chap should mind his own business.”

“Hoity-toity, George.”

It is a subject to which Greenway and Stentson are tenaciously and hilariously attached.

“Is she a stunner, George?”

“Does she look like Marie Lloyd?”

When George does not reply, they put their heads together, tip their hats at an angle, and serenade him. “The-boy-I-love-sits-up-in-the-ga-ll-ery.”

“Go on, George, tell us her name.”

“Go on, George, tell us her name.”

After a few weeks of this, George can take no more. If that’s what they want, that’s what they can have. “Her name’s Dora Charlesworth,” he says suddenly.

“Dora Charlesworth,” they repeat. “Dora Charlesworth. Dora Charlesworth?” They make it sound increasingly improbable.

“She’s Harry Charlesworth’s sister. He’s my friend.”

He thinks this will shut them up, but it only seems to encourage them.

“What’s the colour of her hair?”

“Have you kissed her, George?”

“Where does she come from?”

“No, where does she really come from?”

“Are you making her a Valentine?”

They never seem to tire of the subject.

“I say, George, there’s one question we have to ask you about Dora. Is she a darkie?”

“She’s English, just like me.”

“Just like you, George? Just like you?”

“When can we meet her?”

“I bet she’s a Bechuana girl.”

“Shall we send a private detective to investigate? What about that fellow some of the divorce firms use? Goes into hotel rooms and catches the husband with the maid? Wouldn’t want to get caught like that, George, would you?”

George decides that what he has done, or has allowed to happen, isn’t really lying; it is just letting them believe what they want to believe, which is different. Happily, they live on the other side of Birmingham, so each time George’s train pulls out from New Street, he is leaving that particular story behind.

On the morning of February 13th, Greenway and Stentson are in skittish mood, though George never discovers why. They have just posted a Valentine addressed to Miss Dora Charlesworth, Great Wyrley, Staffordshire. This sets off considerable puzzlement in the postman, and even more in Harry Charlesworth, who has always longed for a sister.

George sits on the train, his newspaper unfolded across his knee. His briefcase is on the higher, and wider, of the two string racks above his head; his bowler on the lower, narrower one, which is reserved for hats, umbrellas, sticks and small parcels. He thinks about the journey everyone has to make in life. Father’s, for instance, began in distant Bombay, at the far end of one of the bubbling bloodlines of Empire. There he was brought up, and was converted to Christianity. There he wrote a grammar of the Gujerati language which funded his passage to England. He studied at St. Augustine’s College, Canterbury, was ordained a priest by Bishop Macarness, and then served as a curate in Liverpool before finding his parish at Wyrley. That is a great journey by any reckoning; and his own, George thinks, will doubtless not be so extensive. Perhaps it will more closely resemble Mother’s: from Scotland, where she was born, to Shropshire, where her father was Vicar of Ketley for thirty-nine years, and then to nearby Staffordshire, where her husband, if God spares him, may prove equally long-serving. Will Birmingham turn out to be George’s final destination, or just a staging post? He cannot as yet tell.

George is beginning to think of himself less as a villager with a season ticket and more as a prospective citizen of Birmingham. As a sign of this new status, he decides to grow a moustache. It takes far longer than he imagines, allowing Greenway and Stentson to ask repeatedly if he would like them to club together and buy him a bottle of hair tonic. When the growth finally covers the full breadth of his upper lip, they begin calling him a Manchoo.

When they tire of this joke, they find another.

“I say, Stentson, do you know who George reminds me of?”

“Give a chap a clue.”

“Well, where did he go to school?”

“George, where did you go to school?”

“You know very well, Stentson.”

“Tell me all the same, George.”

George lifts his head from the Land Transfer Act 1897 and its consequences for wills of realty. “Rugeley.”

“Think about it, Stentson.”

“Rugeley. Now I’m getting there. Hang on—could it be William Palmer—”

“The Rugeley Poisoner! Exactly.”

“Where did he go to school, George?”

“You know very well, you fellows.”

“Did they give everyone poisoning lessons there? Or just the clever boys?”

Palmer had killed his wife and brother after insuring them heavily; then a bookmaker to whom he was in debt. There may have been other victims, but the police contented themselves with exhuming only the next-of-kin. The evidence was enough to ensure the Poisoner a public execution in Stafford before a crowd of fifty thousand.

“Did he have a moustache like George’s?”

“Just like George’s.”

“You don’t know anything about him, Greenway.”

“I know he went to your school. Was he on the Honours Board? Famous alumnus and all that?”

George pretends to put his thumbs in his ears.

“Actually, the thing about the Poisoner, Stentson, is that he was devilish clever. The prosecution was completely unable to establish what kind of poison he’d used.”

“Devilish clever. Do you think he was an Oriental gentleman, this Palmer?”

“Might have been from Bechuana Land. You can’t always tell from someone’s name, can you, George?”

“And did you hear that afterwards Rugeley sent a deputation to Lord Palmerston in Downing Street? They wanted to change the name of their town because of the disgrace the Poisoner had brought upon it. The PM thought about their request for a moment and replied, ‘What name do you propose—Palmerstown?’ ”

There is a silence. “I don’t follow you.”

“No, not Palmerston. Pal-mers-town.”

“Ah! Now that’s very amusing, Greenway.”

“Even our Manchoo friend is laughing. Underneath his moustache.”

For once, George has had enough. “Roll up your sleeve, Greenway.”

Greenway smirks. “What for? Are you going to give me a Chinese burn?”

“Roll up your sleeve.”

George then does the same, and holds his forearm next to that of Greenway, who is just back from a fortnight sunning himself at Aberystwyth. Their skins are the same colour. Greenway is unabashed, and waits for George to comment; but George feels he has made his point, and starts putting the link back through his cuff.

“What was that about?” Stentson asks.

“I think George is trying to prove I’m a poisoner too.”

Arthur

They had taken Connie on a European tour. She was a robust girl, the only woman on the Norway crossing who wasn’t prostrate with seasickness. Such imperviousness made other female sufferers irritated. Perhaps her sturdy beauty irritated them too: Jerome said that Connie could have posed for Brünnhilde. During that tour Arthur discovered that his sister, with her light dancing step, and her chestnut hair worn down her back like the cable of a man-o’-war, attracted the most unsuitable men: lotharios, card-sharps, oleaginous divorcees. Arthur had almost been obliged to raise his stick to some of them.

Back home, she seemed at last to have fixed her eye on a presentable fellow: Ernest William Hornung, twenty-six years old, tall, dapper, asthmatic, a decent wicketkeeper and occasional spin bowler; well-mannered, if liable to talk a streak if in the least encouraged. Arthur recognized that he would find it difficult to approve of anyone who attached themselves to either Lottie or Connie; but in any case, it was his duty as head of the family to cross-examine his sister.

“Hornung. What is he, this Hornung? Half Mongol, half Slav, by the sound of him. Could you not find someone wholly British?”

“He was born in Middlesbrough, Arthur. His father is a solicitor. He went to Uppingham.”

“There’s something odd about him. I can sniff it.”

“He lived in Australia for three years. Because of his asthma. Perhaps what you can sniff are the gum trees.”

Arthur suppressed a laugh. Connie was the sister who most stood up to him; he loved Lottie more, but Connie was the one who liked to pull him up and surprise him. Thank God she had not married Waller. And the same went, a fortiori, for Lottie.

“And what does he do, this fellow from Middlesbrough?”

“He is a writer. Like you, Arthur.”

“Never heard of him.”

“He has written a dozen novels.”

“A dozen! But he’s just a young pup.” An industrious pup, at least.

“I can lend you one if you wish to judge him that way. I have Under Two Skies and The Boss of Taroomba. Many of them are set in Australia, and I find them very accomplished.”

“Do you just, Connie?”

“But he realizes that it is difficult to make a living from writing novels, and so he works also as a journalist.”

“Well, it is a name that sticks,” Arthur grunted. He gave Connie permission to introduce the fellow into the household. For the moment he would give him the benefit of the doubt by not reading any of his books.

Spring was early that year, and the tennis ground was marked out by the end of April. From his study Arthur would hear the distant pop of racquet on ball, and the familiar irritating cry made by a female missing an easy shot. Later, he would wander out and there would be Connie in flowing skirts and Willie Hornung in straw hat and peg-topped white flannels. He noted the way Hornung did not give her any easy points, but at the same time held back from a full weight of shot. He approved: that was how a man ought to play a girl.

Touie sat to one side in a deckchair, warmed less by the frail sun of early summer than by the heat of young love. Their laughing chatter across the net and their shyness with one another afterwards seemed to delight her, and Arthur therefore decided to be won over. In truth, he rather liked the role of grudging paterfamilias. And Hornung was proving himself a witty fellow at times. Perhaps too witty, but that could be ascribed to youth. What was that first jest of his? Yes, Arthur had been reading the sporting pages, and remarked upon a story in which a runner was credited with completing the hundred yards in a mere ten seconds.

“What do you make of that, Mr. Hornung?”

And Hornung had replied, quick as a flash, “It must be a sprinter’s error.”

That August, Arthur was invited to lecture in Switzerland; Touie was still a little weak from the birth of Kingsley, but naturally accompanied him. They visited the Reichenbach Falls, splendid yet terrifying, and a worthy tomb for Holmes. The fellow was rapidly turning into an old man of the sea, clinging round his neck. Now, with the help of an arch-villain, he would shrug his burden off.

At the end of September, Arthur was walking Connie up the aisle, she pulling back on his arm for striking too military a pace. As he handed her over symbolically at the altar, he knew he should be proud and happy for her. But amid all the orange blossom and backslapping and jokes about bowling maidens over, he felt his dream of an ever-increasing family around him taking a knock.

Ten days later, he learned that his father had died in a Dumfries lunatic asylum. Epilepsy was given as the cause. Arthur had not visited him in years, and did not attend the funeral; none of the family did. Charles Doyle had let down the Mam and condemned his children to genteel poverty. He had been weak and unmanly, incapable of winning his fight against liquor. Fight? He had barely raised his gloves at the demon. Excuses were occasionally made for him, but Arthur did not find the claim of an artistic temperament persuasive. That was just self-indulgence and self-exculpation. It was perfectly possible to be an artist, yet also to be robust and responsible.

Touie developed a persistent autumn cough, and complained of pains in her side. Arthur judged the symptoms insignificant, but eventually called in Dalton, the local practitioner. It was strange to find himself transformed from doctor to mere patient’s husband; strange to wait downstairs while somewhere above his head his fate was being decided. The bedroom door was closed for a long time, and Dalton emerged with a face as dismal as it was familiar: Arthur had worn it himself all too many times.

“Her lungs are gravely affected. There is every sign of rapid consumption. Given her condition and family history . . .” Dr. Dalton did not need to continue, except to add, “You will want a second opinion.”

Not just a second, but the best. Douglas Powell, consulting physician at the Brompton Hospital for Consumption and Diseases of the Chest, came down to South Norwood the following Saturday. A pale, ascetic man, clean-shaved and correct, Powell regretfully confirmed the diagnosis.

“You are, I believe, a medical man, Mr. Doyle?”

“I rebuke myself for my inattention.”

“The pulmonary system was not your speciality?”

“The eye.”

“Then you should not rebuke yourself.”

“No, the more so. I had eyes, and did not see. I did not spot the accursed microbe. I did not pay her enough attention. I was too busy with my own . . . success.”

“But you were an eye doctor.”

“Three years ago I went to Berlin to report on Koch’s findings—supposed findings—about this very disease. I wrote about it for Stead, in the Review of Reviews.”

“I see.”

“And yet I did not recognize a case of galloping consumption in my own wife. Worse, I let her join me in activities which will have made it worse. We tricycled in every weather, we travelled to cold climates, she followed me in outdoor sports . . .”

“On the other hand,” said Powell, and the words briefly lifted Arthur’s spirits, “in my view there are promising signs of fibroid growth around the seat of the disease. And the other lung has enlarged somewhat to compensate. But that is the best I can say.”

“I do not accept it!” Arthur whispered the words because he could not bellow them at the top of his voice.

Powell took no offence. He was accustomed to pronouncing the gentlest, courtliest sentence of death, and familiar with the ways it took those affected. “Of course. If you would like the name—”

“No. I accept what you have told me. But I do not accept what you have not told me. You would give her a matter of months.”

“You know as well as I do, Mr. Doyle, how impossible it is to predict—”

“I know as well as you do, Dr. Powell, the words we use to give hope to our patients and those near to them. I also know the words we hear within ourselves as we seek to raise their spirits. About three months.”

“Yes, in my view.”

“Then again, I say, I do not accept it. When I see the Devil, I fight him. Wherever we need to go, whatever I need to spend, he shall not have her.”

“I wish you every good fortune,” replied Powell, “and remain at your service. There are, however, two things I am obliged to say. They may be unnecessary, but I am duty-bound. I trust you will not take offence.”

Arthur stiffened his back, a soldier ready for orders.

“You have, I believe, children?”

“Two, a boy and a girl. Aged one and four.”

“There is, you must understand, no possibility—”

“I understand.”

“I am not talking to her ability to conceive—”

“Mr. Powell, I am not a fool. And neither am I a brute.”

“These things have to be made crystal clear, you must understand. The second matter is perhaps less obvious. It is the effect—the likely effect—on the patient. On Mrs. Doyle.”

“Yes?”

“In our experience, consumption is different from other wasting diseases. On the whole, the patient suffers very little pain. Often the disease will proceed with less inconvenience than a toothache or an indigestion. But what sets it apart is the effect upon the mental processes. The patient is often very optimistic.”

“You mean light-headed? Delirious?”

“No, I mean optimistic. Tranquil and cheerful, I would say.”

“On account of the drugs you prescribe?”

“Not at all. It is in the nature of the disease. Regardless of how aware the patient is of the seriousness of her case.”

“Well, that is a great relief to me.”

“Yes, it may be so at first, Mr. Doyle.”

“What do you mean by that?”

“I mean that when a patient does not suffer and does not complain and remains cheerful in the face of grave illness, then the suffering and the complaining has to be done by someone.”

“You do not know me, sir.”

“That is true. But I wish you the necessary courage nonetheless.”

For better, for worse; for richer, for poorer. He had forgotten: in sickness and in health.

The lunatic asylum sent Arthur his father’s sketchbooks. Charles Doyle’s last years had been miserable, as he lay unvisited at his grim final address; but he did not die mad. That much was clear: he had continued to paint watercolours and to draw; also to keep a diary. It now struck Arthur that his father had been a considerable artist, undervalued by his peers, worthy indeed of a posthumous exhibition in Edinburgh—perhaps even in London. Arthur could not help reflecting on the contrast in their fates: while the son was enjoying the embrace of fame and society, his abandoned father knew only the occasional embrace of the straitjacket. Arthur felt no guilt—just the beginnings of filial compassion. And there was one sentence in his father’s diary which would drag at any son’s heart. “I believe,” he had written, “I am branded as mad solely from the Scotch Misconception of Jokes.”

In December of that year, Holmes fell to his death in the arms of Moriarty; both of them propelled downwards by an impatient authorial hand. The London newspapers had contained no obituaries of Charles Doyle, but were full of protest and dismay at the death of a non-existent consulting detective whose popularity had begun to embarrass and even disgust his creator. It seemed to Arthur that the world was running mad: his father was fresh in the ground, and his wife condemned, but young City men were apparently tying crepe bands to their hats in mourning for Mr. Sherlock Holmes.

Another event took place during this morbid year’s end. A month after his father’s death, Arthur applied to join the Society for Psychical Research.

George

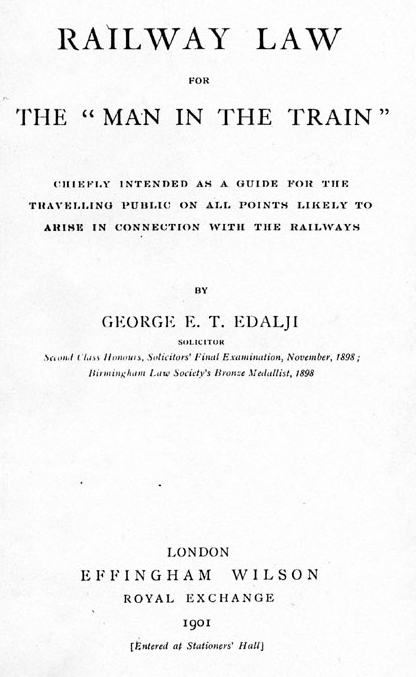

In the Solicitors’ Final Examinations George receives Second Class Honours, and is awarded a Bronze Medal by the Birmingham Law Society. He opens an office at 54 Newhall Street with the initial promise of some overflow work from Sangster, Vickery & Speight. He is twenty-three, and the world is changing for him.

Despite being a child of the Vicarage, despite a lifetime of filial attention to the pulpit of St. Mark’s, George has often felt that he does not understand the Bible. Not all of it, all of the time; indeed, not enough of it, enough of the time. There has always been some leap to be made, from fact to faith, from knowledge to understanding, of which he has proved incapable. This makes him feel a sham. The tenets of the Church of England have increasingly become a distant given. He does not sense them as close truths, or see them working from day to day, from moment to moment. Naturally, he does not tell his parents this.

At school, additional stories and explanations of life were put before him. This is what science says; this is what history says; this is what literature says . . . George became adept at answering examination questions on these subjects, even if they had no real vivacity in his mind. But now he has discovered the law, and the world is beginning finally to make sense. Hitherto invisible connections—between people, between things, between ideas and principles—are gradually revealing themselves.

For instance, he is on the train between Bloxwich and Birchills, looking out of the window at a hedgerow. He sees not what his fellow passengers would see—a few intertwined bushes blown by the wind, home to some nesting birds—but instead a formal boundary between owners of land, a delineation settled by contract or long usage, something active, something liable to promote either amity or dispute. At the Vicarage, he looks at the maid scrubbing the kitchen table, and instead of a coarse and clumsy girl likely to misplace his books, he sees a contract of employment and a duty of care, a complicated and delicate tying together, backed by centuries of case law, all of it unfamiliar to the parties concerned.

He feels confident and happy with the law. There is a great deal of textual exegesis, of explaining how words can and do mean different things; and there are almost as many books of commentary on the law as there are on the Bible. But at the end there is not that further leap to be made. At the end, you have an agreement, a decision to be obeyed, an understanding of what something means. There is a journey from confusion to clarity. A drunken mariner writes his last will and testament on an ostrich egg; the mariner drowns, the egg survives, whereupon the law brings coherence and fairness to his sea-washed words.

Other young men divide their lives between work and pleasure; indeed, spend the former dreaming of the latter. George finds that the law provides him with both. He has no need or desire to take part in sports, to go boating, to attend the theatre; he has no interest in alcohol or gourmandising, or in horses racing one another; he has little desire to travel. He has his practice, and then, for pleasure, he has railway law. It is astonishing that the tens of thousands who travel daily by train have no useful pocket explicator to help them determine their rights vis-à-vis the railway company. He has written to Messrs. Effingham Wilson, publishers of the “Wilson’s Legal Handy Books” series, and on the basis of a sample chapter they have accepted his proposal.

George has been brought up to believe in hard work, honesty, thrift, charity and love of family; also to believe that virtue is its own reward. Further, as the eldest child, he is expected to set an example to Horace and Maud. George increasingly realizes that, while his parents love their three children equally, it is on him that expectation weighs the heaviest. Maud is always likely to be a source of concern. Horace, while in all respects a thoroughly decent fellow, has never been cut out for a scholar. He has left home and, with help from a cousin of Mother’s, managed to enter the Civil Service at the lowest clerical level.

Still, there are moments when George catches himself envying Horace, who now lives in diggings in Manchester, and occasionally sends a cheery postcard from a seaside resort. There are also moments when he wishes that Dora Charlesworth really did exist. But he knows no girls. None comes to the house; Maud has no female friends he might practise acquaintance on. Greenway and Stentson liked to boast experience in such matters, but George was often dubious of their claims, and is glad to have left those two behind. When he sits on his bench in St. Philip’s Place eating his sandwiches, he glances admiringly at young women who pass; sometimes he will remember a face, and have yearnings for it at night, while his father growls and snuffles a few feet away. George is familiar with the sins of the flesh, as listed in Galatians, chapter five—they begin with Adultery, Fornication, Uncleanness and Lasciviousness. But he does not believe his own quiet hankerings qualify under either of the last two heads.

One day he will be married. He will acquire not just a fob watch but a junior partner, and perhaps an articled clerk, and after that a wife, young children, and a house to whose purchase he has brought all his conveyancing skills. He already imagines himself discussing, over luncheon, the Sale of Goods Act 1893 with the senior partners of other Birmingham practices. They listen respectfully to his summary of how the Act is being interpreted, and cry “Good old George!” when he reaches for the bill. He is not sure exactly how you get to there from here: whether you acquire a wife and then a house, or a house and then a wife. But he imagines it all happening, by some as yet unrevealed process. Both acquisitions will depend upon his leaving Wyrley, of course. He does not ask his father about this. Nor does he ask him why he still locks the bedroom door at night.

When Horace left home, George hoped he might move into the empty room. The small desk fitted up for him in Father’s study when he first went to Mason College was no longer adequate. He imagined Horace’s room with his bed in it, his desk in it; he imagined privacy. But when he put his request to Mother, she gently explained that Maud was now judged strong enough to sleep by herself, and George wouldn’t want to deprive her of that chance, would he? It was now too late, he realized, to put in evidence Father’s snoring, which had got worse and sometimes kept him awake. So he continues to work and sleep within touching distance of his father. However, he is awarded a small table next to his desk, on which to place extra books.

He still retains the habit, which has now grown into a necessity, of walking the lanes for an hour or so after he gets back from the office. It is one detail of his life in which he will not be ruled. He keeps a pair of old boots by the back door, and rain or shine, hail or snow, George takes his walk. He ignores the landscape, which does not interest him; nor do the bulky, bellowing animals it contains. As for the humans, he will occasionally think he recognizes someone from the village school in Mr. Bostock’s day, but he is never quite sure. No doubt the farm boys have now grown into farm-hands, and the miners’ sons are down the pit themselves. Some days George gives a kind of half-greeting, a sideways raising of the head, to everyone he meets; at other times he greets no one, even if he remembers having acknowledged them the day before.

His walk is delayed one evening by the sight of a small parcel on the kitchen table. From its size and weight, and the London postmark, he knows immediately what it contains. He wants to delay the moment for as long as possible. He unknots the string and carefully rolls it round his fingers. He removes the waxed brown paper and smooths it out for reuse. Maud is by now thoroughly excited, and even Mother shows a little impatience. He opens the book to its title page:

He turns to the Contents. Bye-Laws and Their Validity. Season Tickets. Unpunctuality of Trains, etc. Luggage. The Carriage of Cycles. Accidents. Some Miscellaneous Points. He shows Maud the cases they considered in the schoolroom with Horace. Here is the one about fat Monsieur Payelle; and here the one about Belgians and their dogs.

This is, he realizes, the proudest day of his life; and over supper it is clear that his parents allow a certain amount of pride to be justifiable and Christian. He has studied and passed his examinations. He has set up his own office, and now shown himself an authority upon an aspect of the law which is of practical help to many people. He is on his way: that journey in life is now truly beginning.

He goes to Horniman & Co. to get some flyers printed. He discusses layout and typeface and print run with Mr. Horniman himself, as one professional to another. A week later he is the owner of four hundred advertisements for his book. He leaves three hundred in his office, not wishing to appear vainglorious, and takes a hundred home. The order form invites interested purchasers to send a Postal Order for 2/3—the 3d to cover postage—to 54 Newhall Street Birmingham. He gives handfuls of the flyer to his parents, with instructions that they press them upon likely looking Men and Women “In the Train.” Next morning he gives three to the stationmaster at Great Wyrley & Churchbridge, and distributes others to respectable fellow passengers.

Arthur

They put the furniture into store and left the children with Mrs. Hawkins. From the fog and damp of London to the clean, dry chill of Davos, where Touie was installed at the Kurhaus Hotel under a pile of blankets. As Dr. Powell had predicted, the disease brought with it a strange optimism; and this, combined with Touie’s placid nature, made her not just stoical but actively cheerful. It was perfectly clear that she had been transformed within a few weeks from wife and companion to invalid and dependant; but she did not fret at her condition, let alone rage as Arthur would have done. He did the raging for both of them, in silence, by himself. He also concealed his blacker feelings. Each uncomplaining cough sent a pain, not through her, but through him; she brought up a little blood, he brought up gouts of guilt.

Whatever his fault, whatever his negligence, it was done, and there was only one course of action: a violent attack on the accursed microbe which was intending to consume her vitals. And when his presence was not required, only one course of distraction: violent exercise. He had brought his Norwegian skis to Davos, and took instruction in their use from two brothers called Branger. When their pupil’s skill began to match his brute determination, they took him on the ascent of the Jacobshorn; at the summit he turned, and saw far below him the flags of the town being lowered in acclamation. Later that winter the Brangers led him over the 9,000-foot Furka Pass. They set off at four in the morning and arrived in Arosa by noon, Arthur thus becoming the first Englishman to cross an Alpine pass on skis. At their hotel in Arosa, Tobias Branger registered the three of them. Next to Arthur’s name, in the space for Profession, he wrote: Sportesmann.

With Alpine air, the best doctors, and money, with Lottie’s nursing help and Arthur’s tenacity in wrestling down the Devil, Touie’s condition stabilized, then began to improve. By the late spring, she was judged strong enough to come back to England, allowing Arthur to depart for an American publication tour. The following winter they returned to Davos. That initial sentence of three months had been overturned; every doctor agreed that the patient’s health was somewhat more secure. The next winter they spent in the desert outside Cairo at the Mena House Hotel, a low white building with the Pyramids looming behind. Arthur was irritated by the brittle air; but soothed by billiards, tennis and golf. He foresaw a life of annual winter exiles, each a little longer than the previous one, until . . . No, he must not let himself think beyond the spring, beyond the summer. At least he could still manage to write during this jerky existence of hotels and steamers and trains. And when he couldn’t write he went out into the desert and whacked a golf ball as far as it would fly. The whole course was in effect nothing but one vast sand-hole; wherever you landed, you were in it. This, it seemed, was what his life had become.

Back in England, however, he ran into Grant Allen: like Arthur a novelist, and like Touie a consumptive. Allen assured him that the disease could be resisted without recourse to exile, and offered himself as living proof. The solution lay in his postal address: Hindhead, Surrey. A village on the Portsmouth road, almost halfway, as it happened, between Southsea and London. More to the point, a spot with its own private climate. It was high up, sheltered from the winds, dry, full of fir trees and sandy soil. They called it the Little Switzerland of Surrey.

Arthur was immediately convinced. He thrived on action, on having an urgent plan to implement; he loathed waiting, and feared the passivity of exile. Hindhead was the answer. Land must be bought, a house designed. He found four acres, wooded and secluded, where the ground dropped away into a small valley. Gibbet Hill and the Devil’s Punchbowl were close at hand, Hankley Golf Course five miles away. Ideas came to him in a rush. There must be a billiards room, and a tennis ground, and stables; quarters for Lottie, and perhaps Mrs. Hawkins, and of course Woodie, who had now signed up for the duration. The house must be impressive yet welcoming: a famous writer’s house, but also a family house and an invalid’s house. It must be full of light, and Touie’s room must have the best view. Every door must have a push-pull knob, as Arthur had once tried to calculate the amount of time lost to the human race in turning the conventional kind. It would be quite feasible for the house to have its own electricity plant; and given that he had now attained a certain eminence, it would not be inappropriate to have his family arms in stained glass.

Arthur sketched a ground plan and handed the work over to an architect. Not just any architect, but Stanley Ball, his old telepathic friend from Southsea. Those early experiments now struck him as appropriate training. He would be taking Touie to Davos again, and would communicate with Ball by letter and, if necessary, telegram. But who knew what architectural shapes might not flit sympathetically between their brains, while their bodies were hundreds of miles apart?

His stained-glass window would rise to the full height of a double-storey hallway. At the top the rose of England and the thistle of Scotland would flank the entwined initials ACD. Below there would be three rows of heraldic shields. First rank: Purcell of Foulkes Rath, Pack of Kilkenny, Mahon of Cheverney. Second rank: Percy of Northumberland, Butler of Ormonde, Colclough of Tintern. And at eye level: Conan of Brittany (Per fess Argent and Gules a lion rampant counterchanged), Hawkins of Devonshire (for Touie) and then the Doyle arms: three stags’ heads and the red hand of Ulster. The true Doyle motto was Fortitudine Vincit; but here, beneath the shield, he placed a variant—Patientia Vincit. This is what the house would proclaim, to all the world and to the accursed microbe: with patience he conquers.

Stanley Ball and his builders saw little but impatience. Arthur, having set up headquarters at a nearby hotel, would constantly drive over and badger them. But at last the house took recognizable shape: a long, barn-like structure, red-bricked, tile-hung, heavy-gabled, lying across the neck of the valley. Arthur stood on his newly laid terrace and cast an inspecting eye on the broad lawn, recently rolled and seeded. Beyond it the ground fell away in an ever narrowing V to where the woods took over. There was something wild and magical about the view: from the first moment Arthur had found it evocative of some German folk tale. He thought he would plant rhododendrons.

On the day the hall window was hoisted into place, he took Touie with him to witness the unveiling. She stood before it, her eye passing over the colours and the names, then coming to rest on the house’s motto.

“The Mam will be pleased,” he observed. Only the slight pause before her smile made him realize something might be awry.

“You are right,” he said immediately, though she had still not uttered a word. How could he have been such a dunderhead? To put up a tribute to your own illustrious ancestry and forget your very mother’s family? For a moment he thought of ordering the workmen to take the whole damn window down. Later, after guilty reflection, he commissioned a second, more modest window for the turning of the stair. Its central panel would hold the overlooked arms and name: Foley of Worcestershire.

He decided to call the house Undershaw, after the hanging grove of trees beneath which it lay. The name would give this modern construction a fine old Anglo-Saxon resonance. Here life might continue as before, if cautiously and within limits.

Life. How easily everyone, including himself, said the word. Life must go on, everyone routinely agreed. And yet how few asked what it was, and why it was, and if it was the only life or the mere amphitheatre to something quite different. Arthur was frequently baffled by the complacency with which people went on with . . . with what they insouciantly called their lives, as if both the word and the thing made perfect sense to them.

His old Southsea friend General Drayson had become convinced of the spiritualist argument after his dead brother spoke to him at a seance. Thereafter, the astronomer maintained that the continuance of life after death was not just a supposition but a provable fact. Arthur had politely demurred at the time; even so, his list of Books To Be Read that year included seventy-four on the subject of Spiritualism. He had despatched them all, noting down sentences and maxims which impressed him. Like this from Hellenbach: “There is a scepticism which surpasses in imbecility the obtuseness of a clodhopper.”

Until Touie’s illness announced itself, he had everything the world assumed necessary to make a man contented. And yet he could never quite shake off the feeling that all he had achieved was just a trivial and specious beginning; that he was made for something else. But what might that something else be? He returned to a study of the world’s religions, but could no more get into any of them than he could into a boy’s suit. He joined the Rationalist Association, and found their work necessary, but essentially destructive and therefore sterile. The demolition of antique faiths had been fundamental to human advancement; but now that those old buildings had been levelled, where was man to find shelter in this blasted landscape? How could anyone glibly decide that the history of what the species had for millennia agreed to call the soul was now at an end? Human beings would continue to develop, and therefore whatever was inside them must also develop. Even a clodhopping sceptic could surely see that.

Outside Cairo, while Touie was breathing deep the desert air, Arthur had read histories of Egyptian civilization and visited the tombs of the pharaohs. He concluded that while the ancient Egyptians had indubitably raised the arts and sciences to a new level, their reasoning power was in many ways contemptible. Especially in their attitude to death. The notion that the dead body, an old, outworn greatcoat which once briefly wrapped the soul, should be preserved at any cost was not just risible; it was the last word in materialism. As for those baskets of provisions placed in the tomb to feed the soul upon its journey: how could a people of such sophistication be so emasculated in their minds? Faith endorsed by materialism: a double curse. And the same curse blighted every subsequent nation and civilization that came under the rule of a priesthood.

Back in Southsea, he had not found General Drayson’s arguments sufficient. But now psychic phenomena were being vouched for by scientists of high distinction and manifest probity, like William Crookes, Oliver Lodge and Alfred Russel Wallace. Such names meant that the men who best understood the natural world—the great physicists and biologists—had also become our guides to the supernatural world.

Take Wallace. The co-discoverer of the modern theory of evolution, the man who stood at Darwin’s side when they jointly announced the idea of natural selection to the Linnaean Society. The fearful and the unimaginative had concluded that Wallace and Darwin had delivered us into a godless and mechanistic universe, had left us alone upon the darkling plain. But consider what Wallace himself believed. This greatest of modern men maintained that natural selection accounted only for the development of the human body, and that the process of evolution must at some point have been supplemented by a supernatural intervention, when the spirit’s flame was inserted into the rough developing animal. Who dared claim now that science was the enemy of the soul?

George & Arthur

It was a cold, clear February night, with half a moon and a heavenful of stars. In the distance the head gear of Wyrley Colliery stood out faintly against the sky. Close by was the farm belonging to Joseph Holmes: house, barn, outbuildings, with not a light showing in any of them. Humans were sleeping and the birds had not yet woken.

But the horse was awake as the man came through a gap in the hedge on the far side of the field. He was carrying a feed-bag over his arm. As soon as he became aware that the horse had noticed his presence, he stopped and began to talk very quietly. The words themselves were a gabble of nonsense; it was the tone, calming and intimate, that mattered. After a few minutes, the man slowly began to advance. When he had made a few paces, the horse shook its head, and its mane was a brief blur. At this, the man stopped again.

He continued his gabble of nonsense, however, and continued looking straight towards the horse. Beneath his feet the ground was solid after nights of frost, and his boots left no print on the soil. He advanced slowly, a few yards at a time, stopping at the least sign of restiveness from the horse. At all times he made his presence evident, holding himself as tall as possible. The feed-bag over his arm was an unimportant detail. What mattered were the quiet persistence of the voice, the certainty of the approach, the directness of the gaze, the gentleness of the mastery.

It took him twenty minutes to cross the field in this way. Now he stood only a few yards distant, head on to the horse. Still he made no sudden move, but continued as before, murmuring, gazing, standing straight, waiting. Eventually, what he had been expecting took place: the horse, reluctantly at first, but then unequivocally, lowered its head.

The man, even now, made no sudden reach. He let a minute or two pass, then crossed the final yards and hung the feed-bag gently round the horse’s neck. The animal kept its head lowered as the man proceeded to stroke it, murmuring all the while. He stroked its mane, its flank, its back; sometimes he just rested his hand against the warm skin, making sure that contact between the two of them was never broken.

Still stroking and murmuring, the man slipped the feed-bag from the horse’s neck and slung it over his shoulder. Still stroking and murmuring, the man then felt inside his coat. Still stroking and murmuring, one arm across the horse’s back, he reached underneath to its belly.

The horse barely gave a start; the man at last ceased his gabble of nonsense, and in the new silence he made his way, at a deliberate pace, back towards the gap in the hedge.

George

Each morning George takes the first train of the day into Birmingham. He knows the timetable by heart, and loves it. Wyrley & Churchbridge 7:39. Bloxwich 7:48. Birchills 7:53. Walsall 7:58. Birmingham New Street 8:35. He no longer feels the need to hide behind his newspaper; indeed, from time to time he suspects that some of his fellow passengers are aware that he is the author of Railway Law for the “Man in the Train” (237 copies sold). He greets ticket collectors and stationmasters and they return his salute. He has a respectable moustache, a briefcase, a modest fob chain, and his bowler has been augmented by a straw hat for summer use. He also has an umbrella. He is rather proud of this last possession, often taking it with him in defiance of the barometer.

On the train he reads the newspaper and tries to develop views on what is happening in the world. Last month there was an important speech at the new Birmingham Town Hall by Mr. Chamberlain about the colonies and preferential tariffs. George’s position—though as yet no one has asked for his opinion on the matter—is one of cautious endorsement. Next month Lord Roberts of Kandahar is due to receive the freedom of the city, an honour with which no reasonable man could possibly quarrel.

His paper tells him other news, more local, more trivial: another animal has been mutilated in the Wyrley area. George wonders briefly which part of the criminal law covers this sort of activity: would it be destruction of property under the Theft Act, or might there be some relevant statute covering one or other particular species of animal involved? He is glad he works in Birmingham, and it will only be a matter of time before he lives there too. He knows he must make the decision; he must stand up to Father’s frowns and Mother’s tears and Maud’s silent yet more insidious dismay. Each morning, as fields dotted with livestock give way to well-ordered suburbs, George feels a perceptible lift in his spirits. Father told him years ago that farm boys and farm-hands were the humble whom God loved and who would inherit the earth. Well, only some of them, he thinks, and not according to any rules of probate that he is familiar with.

There are often schoolboys on the train, at least until Walsall, where they alight for the Grammar School. Their presence and their uniforms occasionally remind George of the dreadful time he was accused of stealing the school’s key. But that was all years ago, and most of the boys are quite respectful. There is a group who are sometimes in his carriage, and by overhearing he learns their names: Page, Harrison, Greatorex, Stanley, Ferriday, Quibell. He is even on nodding terms with them, after three or four years.

Most of his days at 54 Newhall Street are spent in conveyancing—work he has seen described by one superior legal expert as “void of imagination and the free play of thought.” This disparagement does not bother George in the slightest; to him such work is precise, responsible and necessary. He has also drawn up a few wills, and recently begun to obtain clients as a result of his Railway Law. Cases involving lost luggage, or unreasonably delayed trains; and one in which a lady slipped and sprained her wrist on Snow Hill station after a railway employee carelessly spilt oil near a locomotive. He has also handled several running-down cases. It appears that the chances of a citizen of Birmingham being struck by a bicycle, horse, motor car, tram or even train are considerably higher than he would ever have anticipated. Perhaps George Edalji, solicitor-at-law, will become known as the man to call in when the human body is surprised by a reckless means of transportation.

George’s train home from New Street leaves at 5:25. On the return journey, there are rarely schoolboys. Instead, there is sometimes a larger and more loutish element whom George views with distaste. Remarks are occasionally passed in his direction which are quite unnecessary: about bleach, and his mother forgetting the carbolic, and enquiries about whether he has been down the mine that day. Mostly he ignores such words, though if a young rough chooses to make himself especially offensive, George might be obliged to remind him who he is dealing with. He is not physically brave, but at such times he feels surprisingly calm. He knows the laws of England, and knows he can count on their support.

Birmingham New Street 5:25. Walsall 5:55. This train does not stop at Birchills, for reasons George has never been able to ascertain. Then it is Bloxwich 6:02, Wyrley & Churchbridge 6:09. At 6:10 he nods to Mr. Merriman the stationmaster—a moment that often reminds him of His Honour Judge Bacon’s 1899 ruling in the Bloomsbury County Court on the illegal retention of expired season tickets—and positions his umbrella over his left wrist for the walk back to the Vicarage.

Campbell

Since his appointment to the Staffordshire Constabulary two years previously, Inspector Campbell had met Captain Anson on several occasions, but never before been summoned to Green Hall. The Chief Constable’s house lay on the outskirts of town, among the water meadows on the farther side of the River Sow, and was reputed to be the largest residence between Stafford and Shugborough. As he walked up the gravel drive off the Lichfield Road and the size of the Hall gradually revealed itself, Campbell found himself wondering how big Shugborough must be. That was in the possession of Captain Anson’s elder brother. The Chief Constable, being merely a second son, was obliged to content himself with this modest white-painted mansion: three storeys high, seven or eight windows wide, with a daunting entrance porch supported by four pillars. Over to the right there was a terrace and a sunken rose garden, with beyond it a summer house and a tennis ground.

Campbell took all this in without breaking stride. When the parlourmaid admitted him, he tried to suspend his natural professional habits: working out the likely probity and income of the occupants, and committing to memory items worth stealing—in some cases, items perhaps already stolen. Deliberately incurious, he was nonetheless aware of polished mahogany, white panelled walls, an extravagant hall stand, and to his right a staircase with curious twisted balusters.

He was shown into a room directly to the left of the front door. Anson’s study, by the look of it: two high leather chairs on either side of the fireplace, and above it the looming head of a dead elk, or moose. Something antlered anyway; Campbell did not hunt, nor did he aspire to. He was a Birmingham man who had reluctantly applied for transfer when his wife grew sick of the city and longed for the slowness and space of her childhood. Fifteen miles or so, but to Campbell it felt like exile in another land. The local gentry ignored you; the farmers kept to themselves; the miners and ironworkers were a rough lot even by slum standards. Any vague notions that the countryside was romantic were swiftly extinguished. And people out here seemed to dislike the police even more than they did in the city. He’d lost count of the times he’d been made to feel superfluous. A crime might have been committed and even reported, but its victims had a way of letting you know that they preferred their own notion of justice to any purveyed by an inspector whose three-piece suit and bowler hat still smelt of Brummagem.

Anson bustled in, shook hands and seated his visitor. He was a small, compact man in his middle forties, with a double-breasted suit and the neatest moustache Campbell had ever seen: its sides seemed to be mere extensions of his nose, and the whole fitted the triangulation of his upper lip as if bought from a catalogue after precise measurement. His tie was held in place with a gold pin in the shape of the Stafford knot. This proclaimed what everyone already knew: that Captain the Honourable George Augustus Anson, Chief Constable since 1888, Deputy Lieutenant of the county since 1900, was a Staffordshire man through and through. Campbell, being one of the newer breed of professional policemen, did not see why the head of the Constabulary should be the only amateur in the force; but then much in the functioning of society appeared to him arbitrary, based more on antique prejudice than modern sense. Still, Anson was respected by those who worked under him; he was known as a man who backed his officers.

“Campbell, you will have guessed why I asked you to come.”

“I assume the mutilations, sir.”

“Indeed. How many have we now had?”

Campbell had rehearsed this part, but even so reached for his notebook.

“February second, valuable horse belonging to Mr. Joseph Holmes. April second, cob belonging to Mr. Thomas ripped in exactly the same fashion. May fourth, a cow of Mrs. Bungay’s similarly treated. Two weeks later, May eighteenth, a horse of Mr. Badger’s terribly mutilated, and also five sheep on the same night. And then last week, June sixth, two cows belonging to Mr. Lockyer.”

“All at night?”

“All at night.”

“Any discernible pattern to events?”

“All the attacks happened within a three-mile radius of Wyrley. And . . . I don’t know if it’s a pattern, but they all occurred in the first week of the month. Except for those of May eighteenth, which didn’t.” Campbell was aware of Anson’s eye on him, and hurried on. “The method of ripping is, however, largely consistent from attack to attack.”

“Consistently disgusting, no doubt.”

Campbell looked at the Chief Constable, unsure if he did, or didn’t, want the details. He took silence for regretful assent.

“They were ripped under the belly. Crosswise, and generally in a single cut. The cows . . . the cows also had their udders mutilated. And there was damage inflicted upon . . . upon their sexual parts, sir.”

“It beggars belief, Campbell, doesn’t it? Such senseless cruelty to defenceless beasts?”

Campbell pretended to himself that they were not sitting beneath the glassy eye and severed head of the elk or moose. “Yes, sir.”

“So we are looking for some maniac with a knife.”

“Probably not a knife, sir. I spoke to the veterinary surgeon who attended the later mutilations—Mr. Holmes’ horse was treated as an isolated incident at the time—and he was puzzled as to the instrument used. It must have been very sharp, but on the other hand it cut into the skin and the first layer of muscle and no further.”

“So why not a knife?”

“Because a knife—a butcher’s knife, say—would have gone deeper. At some point, anyway. A knife would have opened up the guts. None of the animals was actually killed in the attacks. Not at the time. They either bled to death or were in such a state when found that they had to be put down.”

“So if not a knife?”

“Something that cuts easily but shallowly. Like a razor. But with more strength than a razor. It could be a tool from the leather trade. Or a farm instrument of some kind. I would assume the man was accustomed to handling animals.”

“Man or men. A vile individual, or a gang of vile individuals. And a vile crime. Have you come across it before?”

“Not in Birmingham, sir.”

“No, indeed.” Anson gave a wan smile and fell briefly silent. Campbell allowed himself to think about the police horses in the Stafford stables: how alert and responsive they were, how warm and smelly and almost furry in their hairiness; how they twitched their ears and put their heads down at you; how they blew through their noses in a way that reminded him of a boiling kettle. What species of human could wish such an animal harm?

“Superintendant Barrett remembers a case some years ago of a wretch who fell into debt and killed his own horse for the insurance. But a murderous spree like this . . . it seems so foreign. In Ireland, of course, the midnight houghing of the landlord’s cattle is practically part of the social calendar. But then, little would ever surprise me of a Fenian.”

“Yes, sir.”

“It must be brought to a swift end. These outrages are blackening the reputation of the entire county.”

“Yes, the newspapers—”

“I do not give a fig about the newspapers, Campbell. I care about the honour of Staffordshire. I do not want it deemed the haunt of savages.”

“No, sir.” But the Inspector thought the Chief Constable must be aware of certain recent editorials, none of them complimentary, and some of them personal.

“I would suggest you look into the history of crime in Great Wyrley and its environs in the last years. There have been some . . . peculiar goings-on. And I suggest you work with those who know the area best. There’s a very sound Sergeant, can’t remember his name. Large, red-faced fellow . . .”

“Upton, sir?”

“Upton, that’s it. He’s a man who keeps his ear close to the ground.”

“Very well, sir.”

“And I am also drafting in twenty special constables. They can report to Sergeant Parsons.”

“Twenty!”

“Twenty, and damn the expense. It’ll come out of my own pocket if necessary. I want a constable under every hedge and behind every bush until this man is caught.”

Campbell was not concerned about the expense. He wondered how you disguised the presence of twenty special constables in an area where the least rumour travelled quicker than the telegraph. Twenty specials, most of them unfamiliar with the territory, against a local man who might just choose to stay at home and laugh at them. And in any case, how many animals could twenty constables protect? Forty, sixty, eighty? And how many animals were there in the district? Hundreds, probably thousands.

“Any further questions?”

“No, sir. Except . . . if I may ask a non-professional question?”

“Go ahead.”

“The porch outside. With the pillars. Do they have a name? The style, I mean?”

Anson looked as if this was the most extraordinary question a serving officer had ever asked. “Pillars? I wouldn’t have the slightest idea. It’s the sort of thing my wife would know.”

In the next days, Campbell reviewed the history of crime in Great Wyrley and its immediate purlieus. He found it much as he would have expected. A certain amount of theft, mostly of livestock; various cases of assault; some vagrancy and public drunkenness; one attempted suicide; a girl sentenced for writing abuse on farm buildings; five cases of arson; threatening letters and unsolicited goods received at Wyrley Vicarage; one indecent assault and two indecent behaviours. There had been no previous attacks on animals in the last ten years, as far as he could discover.

Nor could Sergeant Upton, who had policed the district for twice that time, recall any. But the question did remind him of a farmer, now passed on to a better world—unless, sir, it turned out to be a worse one—who was suspected of loving his goose too much, if you catch my meaning. Campbell cut off this parish-pump tittle-tattle; he had quickly marked Upton as someone left over from the time when Constabularies were happy to recruit almost anyone except the obviously halt, lame and half-witted. You might consult Upton about local rumours and grudges, but would hardly trust his hand upon a Bible.

“So, you worked it out then, sir?” the Sergeant wheezed at him.

“Is there something specific you have to tell me, Upton?”

“I wouldn’t say that. But takes one to know one. Set one to catch one. I’m sure you’ll get there in the end, Inspector. What with you being an Inspector from Birmingham. Oh yes, you’ll get there in the end.”

Upton struck him as a mixture of sly ingratiation and vague obstructiveness. Some of the farm-hands were exactly the same. Campbell felt more at ease with Birmingham thieves, who at least lied to you directly.

On the morning of June 27th, the Inspector was called to the Quinton Colliery, where two of the company’s valuable horses had been ripped during the night. One had bled to death, and the other, a mare which had suffered additional mutilation, was in the process of being destroyed. The veterinary surgeon confirmed that the same instrument—or, at least, one with precisely the same effects—had been used as before.

Two days later, Sergeant Parsons brought Campbell a letter addressed to “The Sergeant, Police Station, Hednesford, Staffordshire.” It had been posted from Walsall, and was signed by one William Greatorex.