As they rode through town, bulbous-eyed Faceless lined the road, popping their scrolled fingers in what might have been their version of applause. Parchment houses lined the streets, along with a large building that Kara took to be a library. A circle of stones, now cocooned in paper, held the memory of meditative reading and quiet conversation. Long ago, before grimoires and Spellfires and Whisperers, this had been a pretty place.

They came to a sudden stop on the outskirts of town. Good thing it wasn’t far, Kara thought, for hanging upside down off the side of the rustle-foot had already begun to make her head feel heavy and strange. She twisted her neck to take stock of their new location but could see only the backs of tightly pressed bodies. Most were Faceless, but there were a small collection of red-robed witches as well. They gave Kara a cursory glance and then returned their attention to something beyond her view.

Using a hooked spear, a short Faceless—perhaps no more than a child—cut Kara’s hands and feet free and pulled her to the ground like shoddy cargo. Kara’s wrists were only chafed, but her feet had gone completely numb during the journey. She pushed herself into a sitting position and rubbed feeling into them.

“Why’s it so crowded?” Kara asked.

“These particular witches have all gotten paper strips recently,” Grace said, her hands shaking slightly as she undid the bow in her hair and then retied it neatly in place. “They’ve been brought here to witness what will happen if they don’t fall in line. As for the Faceless . . . they always congregate when a Change takes place, like the way the villagers back home gathered together to celebrate a new birth.”

Grace tried to stand, but without a staff to lean on she was forced to place all her weight on her good leg and wobbled as she rose. Taff slid to his right so that she could use his shoulder for support. Neither one acknowledged the assistance, though Kara thought she saw the slightest glint of gratitude in Grace’s eyes.

“How did they know we were coming?” Kara asked.

“They’re not here for us, though I’m sure they’ll stay now that they’ve made the journey,” Grace said. She pointed past the crowd. “See? We’re not the first ones being sent into the Changing Place today.”

Though her feet were still prickling her with pins and needles, Kara managed to rise.

Past the crowd, Kara saw a woman being led up a short flight of stairs to a dark tunnel. Faceless kept pace to either side of her, but the woman did not seem likely to resist; she walked with the resigned footsteps of one who had long ago accepted her fate. Behind her a train of paper strips dragged along the steps. She turned back to the crowd, as though wanting to see the world through her own eyes one last time, and then vanished into the darkness.

“Landra,” Kara said, recognizing the old woman they had seen on the barge. “I guess she got her final strip.”

The guards made their way to the base of the steps and stood with spears held across their chests, though there seemed little point; no one had any desire to follow the unfortunate woman. Time, which always passed so strangely in the Well, squeezed to a trickle. All was silent. Kara did, however, catch some of the witches’ thoughts skittering along the ground: Let’s see if she takes longer than Karin to Change. I’ll never let this happen to me. Whatever they want, whatever they want, whatever they want . . .

The Faceless shed no thoughts at all.

Taff gripped her wrist.

“The turtle!” he gasped.

“What?”

“Look at the building! Look at it!”

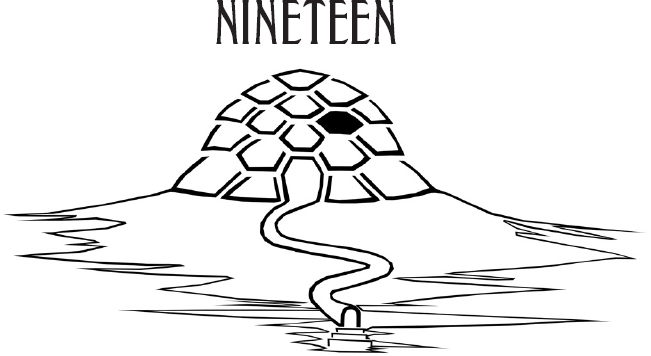

Kara craned her neck to see past the milling witches to the building beyond them. From the main entrance a long paper tunnel, like the comb of a giant wasp nest, curved along the ground to a small dome in the distance. Its paper roof was the same color as the sky except for a stubborn hexagonal tile, shockingly green against all that sameness.

With a sharp intake of breath, Kara remembered the drawing in Sordyr’s letter.

“The queth’nondra,” she said.

“The who?” asked Grace.

“A long time ago, the Well of Witches used to be part of a school for magic,” Kara said. “That building was where students took their final test. Those who passed became full wexari.”

But this is the Changing Place. The source of all the Faceless. How could such a good place become so evil? Or is that the point? The greater the good, the greater it can be corrupted?

“What’s a wexari?” Grace asked.

Kara shook her head. “Never mind.” Looking at the building again, she couldn’t help but smile. “It does look like a turtle.”

“I wish Safi were here to see it,” Taff said. He looked down, perhaps wondering if he would ever see his friend again. Kara was on the verge of offering some comforting words when Landra exited the tunnel. Some of the witches gasped. There was even a single, quickly muffled scream. But the primary noise was from the Faceless, who popped their fingers in jubilation.

Landra’s face was a taut, flat parchment from which all features had been erased. She tottered down the steps where Faceless wrapped her almost tenderly with paper strips. These immediately adhered to her body like new skin. The Faceless fawned over the seven nubs protruding from Landra’s neck like parents over a baby’s smile.

I guess it takes longer to grow a mask-arm than erase a face, Kara thought. Despite the warm, stale air she felt as cold as ice.

That’s what’s going to happen to me. That’s what I’m going to become.

Two Faceless guards pushed through the crowd and headed in the children’s direction. At first Kara thought they were coming for her, but at the last moment they veered toward a different target. “Get off!” Grace screamed, clawing at their paper arms as they dragged her toward the stairs. “Not this! Please! I don’t want to Change! I don’t want to be a monster!” Taff tried to intervene but was tossed aside with little effort; the Faceless were far stronger than they looked. “Kara!” shouted Grace. “Kara! Please! I know you can stop them! You won’t let them do this to me! You’re good, Kara, good—”

The guards came to a sudden halt. In front of them, blocking the entrance to the queth’nondra, stood Redmask. It looked at Grace, shook its head, and pointed to Kara. The two guards exchanged a look, momentarily surprised by this change in routine, but when Redmask took a step toward them they quickly dropped Grace to the ground and started toward Kara.

“Don’t bother,” she said. “I’ll walk.”

Kara passed through the parted crowd. Taff tried to reach her but was restrained by a Faceless. “What are you doing?” he asked. “Kara!” She kept moving. It will only make it harder if I stop. And they’ll just drag me inside anyway. Whatever my fate might be, I’ll meet it standing.

Redmask stood at the bottom of the steps, arms crossed with smug satisfaction. Kara looked away as she passed; she refused to let the foul creature see the fear in her eyes. In the distance the Burngates had grown darker and begun to swell outward like warped boards. Three helixes had risen from the ground nearly high enough to touch the parchment sky. Kara could see tiny figures making their way up the narrow slopes.

The Burngates will open soon. After that, who knows how long it will be before another witch casts her Last Spell? I won’t get a second chance. I have to escape this place. I have to save Father.

She stepped forward into the tunnel and the world immediately turned black. Gelatinous air seemed to clutch at Kara, and a warm, slimy substance with the consistency of raw eggs slid up her nostrils and down the canals of her ears. Oxygen was reduced to a teasing dribble. Is this the stuff that makes people Faceless? Is it inside me now? Am I already changing? She kept moving forward, each footstep a struggle. Faded memories were drawn to the forefront of her thoughts like iron filings to a magnet. Images slid by at blinding speed: looking up at her parents from within the folds of a warm blanket, her first steps, Mother’s death, finding the grimoire, their flight from the villagers, the Thickety, the unghosts, Safi’s sacrifice, entering the tunnel just moments ago. Her life was sliced open and exposed, and Kara knew that she was not the only one watching. Something, some entity, studied every moment. She felt the weight of its regard like a face peering over her shoulder, learning every thought and experience, every fear and desire. By the end, it knew more about Kara than she knew about herself.

At which point she was spit out of the tunnel and sent tumbling across the ground. Kara ran her hands over her face, fearing that her fingers would meet only gruesome smoothness but feeling instead the familiar curves of eyes, nose, and mouth. She clutched her neck and was overjoyed to find it bereft of the knobby pieces of flesh that would grow into mask-arms.

I haven’t changed. I’m still me.

Kara placed her hands on the ground, intending to push herself to her feet, and felt something strange beneath her palms.

It can’t be!

Grass, lush and green, tickled her fingertips. Kara was not outside, however, but in a large room with a door set into the opposite wall. In the center of the room grew a beautiful tree dappled with orange and yellow leaves. Kara felt sunlight on her face. Looking up, she was surprised to find that the room had no ceiling—or no roof, for that matter. The walls simply opened up to a glorious blue expanse with fluffy clouds.

“Impossible,” Kara said.

“I’m surprised, Kara Westfall,” replied a man sitting against the opposite side of the tree. “After everything you’ve been through, I was certain you would have stricken that deceitful word from your vocabulary by now.”

Kara crossed the room until she was able to see him: a small man wearing a green robe with a dark birthmark that covered nearly half his face. He looked a little older than his portrait in Sablethorn, but not by much.

“Minoth Dravania,” Kara said.

“Indeed,” he replied. Minoth spoke with a strange accent Kara had never heard before, his voice as raspy as burlap. “How nice to hear my name spoken aloud after all this time. I was starting to wonder if I remembered it true.”

“How are you . . .”

“. . . still alive? Nothing special. Hardly even magic, really. I just forced my remaining years into this one specific spot instead of letting them spread willy-nilly all over the world. People would be surprised how far a few good years could last them if they weren’t so wasteful! Unfortunately, that means I cannot leave the shade of this tree without immediately perishing. A fair trade, I think. It’s a rather nice tree.”

Minoth gave her the faintest trace of a smile. Kara thought he might be having fun with her, but she wasn’t certain.

“How is it possible to see the sky from here?” Kara asked. “Have I left the Well of Witches?”

“Unfortunately not. This place is all I could save of the original Phadeen. The eye of the storm, if you will.” He traced his fingertips along the bark of the tree. “You should have seen it in its prime, Kara. My life’s work. Do you know what happened?”

Minoth watched her expectantly, and Kara straightened like a schoolgirl standing before the class.

“Evangeline’s Last Spell,” she said.

He tilted his hand from side to side, as though she had given a response that approached the answer without truly hitting the mark.

“It was indeed the princess who cast the spell,” he allowed. “Still, I’ve always found it hard to believe that one little girl could have been responsible for transforming a magnificent place like Phadeen into the Well of Witches.” He folded his hands in his lap and fixed Kara with a knowing stare. “You might want to think on that at some point. But today we have a more immediate concern. You’ve made it a long way without magic, my dear, and not without your share of travails. I’m quite impressed.”

Kara blushed at the unexpected praise.

“Thank you,” she said with reflexive politeness, before considering the implications of his comment. “Wait . . . how do you know all this? How do you even know my name?”

“In the tunnel, all that sticky stuff like blackberry jam? That was the mind of the queth’nondra learning everything it could about you.” Minoth twirled his thumbs together guiltily. “I confess I might have peeked a little. You’ve led an interesting life! Witch duels, tree monsters, shadow creatures . . . though it must have been a fearsomely hard thing to be Sundered like that.”

Kara recognized the word from Sordyr’s letter but did not understand how it applied to her. Minoth, seeing the confusion on her face, added, “What Rygoth did. Sundered you. Took away your magic. Speaking of which, how’d you like to get it back?”

For a few moments, Kara was too stunned to answer.

“I didn’t think it was possible,” she said quietly.

“It’s not. But that’s never stopped me before. So I’ll ask one more time: Would you like to be a witch again?”

Kara wondered when she had given up the possibility of regaining her powers. At the banquet table with Rygoth, perhaps? Or was it even earlier than that, as long ago as the Wayfinder? It didn’t matter now. Long-suppressed hope surged through her body, bringing tears to her eyes.

“Yes,” Kara said. “I would like that very much. Can you really do it?”

“I wish it were that easy, Kara,” Minoth said, with genuine regret in his eyes. “But even I cannot restore a wexari’s magic.” He indicated the door behind her. “Only the final chamber of the queth’nondra can do that. The good news is you’ve already walked your Sundering. All that remains is to answer the riddle without a question.”

Kara’s head spun.

“I’m a little lost here,” she said. “I know that the Sundering is some kind of test—”

“More than that, my dear. Much more. The Sundering was a rite of passage that could have lasted anywhere from a few months to several years. To start, a wexari’s powers were taken away—”

“On purpose?” Kara asked, shocked.

“It didn’t hurt,” Minoth said. “There was a potion. Or maybe an ointment. It’s been a long time and the details escape me. In either case, sundered wexari were sent out into the world, penniless and with only the clothes on their backs, to learn what life was like without magic. Some wandered. Some learned trades. Some—”

“But that doesn’t make any sense! Sablethorn was a school for magic! How can you teach someone how to be a wexari if you take away their power?”

“Sablethorn would have been a very poor school indeed if we focused only on how to use magic and spent no time on the when and why. In my day those with the gift were revered and admired from birth. They were exalted above all others. Imagine if you had been told your entire life that you were more important than other people. Something truly terrible might happen. You might start to believe it! You might begin thinking, ‘Why should I help any of these sheep around me?’ For those with true power, such thoughts are the first steps down a dark, dark path. That’s why it was crucial that students experience firsthand what it was like to be powerless, poor, downtrodden—to understand life from a different perspective. Nothing quells the dark temptations of power better than empathy. Do you understand?”

Kara gave a slight nod.

“It’s just—a world where people admired those who could use magic is hard for me to imagine,” she said.

Minoth patted the ground and Kara sat beside him. He smelled of mothballs and butterscotch.

“I saw how the people of your village treated you,” Minoth said, his lips clamped together with restrained anger. “An entire religion dedicated to the notion that magic was evil. I’ve never heard of such a ridiculous thing.”

“But are they so wrong?” Kara asked. “I’ve seen what grimoires do. They change people. Make them do bad things.”

Minoth’s face fell.

“Oh, Kara,” he said. “You poor, poor child. Magic isn’t evil. It’s sick—and badly in need of healing.” He placed his dry fingertips against her forehead. “Let your mind whittle away at that for a time, and come back to it after it has taken shape. For now you need to understand the second purpose of the Sundering. Yes, wexari were meant to learn empathy and humility, but they were expected to meditate on their greatest fault as well. Everyone has one. Envy. Laziness. Greed. When they returned from the Sundering, students were required to enter the final chamber of the queth’nondra and prove that they understood this weakness, for recognizing our faults is the first step toward correcting them. Only then would their magic be restored.”

“But how can you prove such a thing?” Kara asked.

Minoth smiled.

“The riddle without a question,” he said. “It’s different for everyone. That’s why you must pass through the tunnel. The queth’nondra needs to learn everything about you in order to know what riddle to pose. If students gave the correct answer, their powers would return on the spot and they would graduate from Sablethorn as full-fledged wexari. If their answer was wrong, however . . .”

“They lost their magic forever and donned the green veil,” Kara said, remembering the painting in the dining hall of Sablethorn. “Just because students failed to solve a riddle, you made them hide their faces in shame and become servants? That was beyond cruel.”

Minoth’s face colored slightly.

“When I became headmaster I did try to abolish that particular rule, but the oldest traditions are hardest to change. And I found, quite to my surprise, that many students were relieved to fail the queth’nondra trial. Being a wexari is a dangerous life, not for everyone.”

“So instead you made them servants?” Kara asked, her voice rising. “They did nothing wrong. Why did they have to hide their faces behind—”

Kara gasped.

“That’s why the witches who enter this place are changed into Faceless. The queth’nondra is confused. It thinks anyone who steps through the tunnel is here to be tested, like back in the Sablethorn days, only these poor girls don’t know anything about that, so of course they fail. They don’t have a chance. Used to be they were only punished with a green veil, but now they’re punished with a different sort of mask, aren’t they?”

Minoth shifted uncomfortably.

“You are correct,” he said. “The queth’nondra was not totally immune to the corruptive influence of the Well. I warned the first witches who wandered in here that they should not enter the final chamber, but there’s no going back through the tunnel and no one ever heeds me anyway. When they failed the trial—as is inevitable for any who are not wexari—they should have simply been given green veils to cover their faces, but the queth’nondra, poisoned by darkness, grew confused and overzealous in its duties, and—”

“—took away their faces instead,” Kara said.

Minoth nodded. “You would have made a fine addition to Sablethorn. You have a quick mind.”

“You should meet my brother.”

Kara eyed the door set into the opposite wall. All of a sudden she wanted to get out of this room as quickly as possible.

“How can I solve a riddle when I don’t know the question?”

Minoth tsked.

“But the riddle is the question, my dear; figure that out and you’re halfway home. The general idea of the chamber is the same for each student, however. It will be filled with objects, and you must leave with only what you need to prove to the queth’nondra that you understand your greatest fault—what you must overcome in order to become a good wexari. Do that, and your powers shall be restored.”

“And if I’m wrong?” Kara asked.

Minoth met her eyes but did not answer. They both knew what would happen to her if she were wrong.

“What was your greatest fault?” Kara asked.

The old schoolmaster’s eyes widened in surprise.

“Interesting,” he said. “All these years, and no one has ever asked me that. I suppose I can tell you. As you can see, I’m an unusual-looking man. At this stage in my life I’ve grown quite accustomed to it, but when I was young I was sensitive and bristled at the slightest stare. I walked my Sundering for three years before I finally realized that my outward appearance was spectacularly unimportant. I left the chamber wearing a jester’s cap and shoes with tiny bells.”

“Which proved you didn’t care anymore if people mocked you for how you looked,” Kara said.

Minoth held his hands out to her, palms up: Now you get it.

“How do you know all this will still work?” Kara asked. “Like you said, the Well corrupted the queth’nondra, made it turn all those witches into monsters. Even if I answer the riddle correctly, are you sure it will still give me back my powers and not do something . . . less helpful?”

The smile slipped from Minoth’s face.

“No,” he said. “To tell you the truth, I’m really not sure what it will do. All you can do is believe. Are you ready to do that, Kara?”

“I hope so.”

“Do more than that. The queth’nondra does not take well to uncertainty. Make sure you’re positive before you leave the chamber. You’ll have great need of your powers in the coming days, Kara Westfall. As I said before, magic is sick. And I suspect you’re the one meant to heal it.”

Taking a deep breath, Kara faced the door and placed her hand on the curved handle. Though her lavender dress remained dry, her red cloak, covered with the sticky substance from her journey through the tunnel, had begun to stiffen. No sense trying to blend in with the other witches anymore, Kara thought. She shed the cloak like an unwanted skin and opened the door.