CHAPTER 5

REAL ESTATE INVESTMENT TRUSTS

Real estate investing, even on a very small scale, remains a tried and true means of building an individual’s cash flow and wealth.

Robert T. Kiyosaki, Businessman and internationally known investor

Are you wondering if investing in real estate is right for you? If you own a house, you may be thinking that you’re already investing in real estate. However, a house is a consumption good, not an investment, especially when you finance it with a mortgage loan. Instead of generating current income, it requires regular mortgage interest, real estate taxes, insurance payments, and maintenance costs. For many intelligent investors throughout history, real estate has been an excellent way to increase wealth and build fortunes because it fulfills a basic need. In fact, American industrialist John D. Rockefeller once said, “The major fortunes in America have been made in land.” When you invest in real estate, you’re buying physical land or property. That is, you’re investing in a real, tangible asset. Real estate is generally considered as an alternative investment to more traditional asset classes such as stocks, bonds, and cash.

Real estate is at the core of almost every business, and it’s certainly at the core of most people’s wealth. In order to build your wealth and improve your business smarts, you need to know about real estate.

Donald Trump

Directly investing in real estate offers various benefits. Historically, an important benefit of real estate as an asset class in a portfolio is that it offers diversification. You also have greater control over your investment. Rental properties can produce positive cash flow and appreciate in value. You can use other people’s money to gain leverage and potentially enhance your return. Additionally, real estate investments can provide tax benefits because no double taxation of income occurs.

Despite its advantages, direct ownership of real estate has its drawbacks. Real estate as an investment has barriers to entry. For example, real estate is costly and difficult to buy, sell, and operate. Managing property and tenants isn’t for everyone given the responsibilities and challenges that must be assumed. Getting financing can also be a hassle. You must also have a good understanding of details involving such areas as titles, insurance, and negotiation. Real estate investing requires patience, careful cost analysis, and hands-on work. Compared to traditional investments, real estate is generally less organized and efficient and sometimes has lower liquidity. That is, when you have a direct investment in real estate, you can’t jump in and out quickly and convert the asset into cash in a hurry. Changing tax codes can reduce or eliminate tax benefits. Measuring the relative performance of real estate can also be challenging given that it doesn’t actively trade. Finally, markets can be fickle and lead to losses when times or circumstances go bad. The bottom line is that investing in real estate involves many risks. Thus, if you’re highly risk-averse, investing in single properties may not be for you.

Wouldn’t it be nice to keep many of the benefits of investing in real estate but to avoid some of its drawbacks? Fortunately, you can “have your cake and eat it too.” That is, you can have two good things happen at the same time, by investing in real estate through a real estate investment trust (REIT). As a “hands-off” passive investment, REITs offer the benefits of owning real estate without having to acquire and manage the property.

REITs began in the United States when President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed into law the REIT Act of 1960. Congress created REITs to provide all investors, especially small investors, with more liquid access to a professionally managed portfolio of real estate assets. Although the first REIT – American Realty Trust – was created in 1961, individual investors initially didn’t strongly embrace REITs. The popularity of REITs increased when investors faced low-interest rates, forcing them to look beyond bonds for income-producing investments, and the advent of mutual funds and exchange-traded funds (ETFs) focusing on real estate. Before the financial crisis of 2007–2008, US investors had an insatiable appetite to own real estate and other tangible assets. Although more than 35 countries have REITs, the majority of the laws governing REITs mirror the US approach to REIT-based real estate investment.

Everyone can invest in average opportunities; wealth is built by investing in the greatest opportunity the economy presents.

Giovanni Fernandez

This chapter provides an overview of REITs to help you gain an appreciation of the role that REITs can play in a portfolio. Whenever the chapter uses the generic term REIT, it refers to publicly (exchange) traded REITs in the United States unless otherwise specified. The chapter is intended to help you more toward becoming a savvy investor in REITs.

5.1. WHAT IS A REIT?

A real estate investment trust (REIT) is an entity that invests directly in income-producing real estate in a range of property sectors or indirectly by providing construction loans and buying real estate mortgages. One goal of a REIT is to generate stable and sustainable income distributions. If you hold REIT shares, you don’t directly own the properties, the REIT does. These professionally managed properties range from office buildings and shopping centers to hotels and apartments, even timber-producing land. Some REITs invest in a single region or metropolitan area whereas others invest throughout the country or the world. From a risk-return perspective, REITs occupy a middle-ground between stocks and bonds, providing you with a blend of income and growth.

A REIT pools money from investors and uses the capital to buy a portfolio of real estate properties or mortgages. Thus, REITs are another type of a pooled investment vehicle (PIV) that enables investors, especially individuals with limited funds, to buy real estate as a group that they might not otherwise be able to purchase individually. REITs earn a return from the properties they acquire by renting, leasing, or selling them. When you invest in a REIT, you become a shareholder, and each share usually entitles you to vote and to receive a portion of distributable income. Although trusts distribute a major portion of their income to investors, usually on a monthly or quarterly basis, these distributions aren’t guaranteed, may be reduced or suspended, and are carried out at the discretion of the REIT’s managers.

5.2. HOW DOES A REIT WORK?

In the United States, a REIT is formed by organizing an entity under the laws of one of the 50 states or the District of Columbia. However, most publicly traded REITs are formed either as trusts or corporations in Maryland. Maryland is such a popular state for incorporating REITs because Maryland law treats REITs somewhat advantageously.

To obtain its initial capital, a publicly traded REIT engages in an initial public offering (IPO), just like any other stock offered to the public. Some REITs are closed-end, which means that they can only issue shares to the public once unless they obtain shareholder approval to issue additional shares. Others are open-end and can issue new shares and redeem shares at any time. The external funds raised enable the REIT to buy real estate, develop, and manage it to generate profits. A REIT can be managed either internally by its officers and employees or externally by a manager who receives a flat fee and an incentive fee for managing the REIT’s portfolio of assets. Investors who buy IPOs are investing in real estate, which is managed like a stock portfolio. Shares of a publicly traded REIT are traded in the secondary market, also called the aftermarket, which is the financial market where previously issued shares are bought and sold.

REIT shareholders elect a board of directors whose members are normally real estate professionals. The board is responsible for selecting the REIT’s investments and hiring the management team, which is responsible for handling daily operations.

The business model of most REITs involves leasing space and collecting rent on the real estate. The company generates income that it distributes to shareholders in the form of dividends. Although REITs must pay out at least 90% of their taxable income to shareholders, most pay out a much higher percentage. To maintain its status as a pass-through entity, a REIT must deduct distributed dividends from its corporate taxable income. As a pass-through entity, a REIT isn’t required to pay corporate federal or state income tax. Instead, it passes the responsibility of paying these taxes onto its shareholders. REITs avoid double taxation, which involves paying taxes at both the corporate and individual levels. However, tax laws don’t permit them to pass tax losses through to investors.

As long as you have more cash flowing in than flowing out, your investment is a good investment.

Robert T. Kiyosaki

5.3. WHAT CRITERIA MUST A COMPANY MEET TO QUALIFY AS A REIT?

To qualify as a REIT, a company must comply with various provisions within the Internal Revenue Code.

- Be structured as a corporation, business trust, or similar association.

- Be managed by a board of directors or trustees.

- Offer fully transferable shares.

- Have at least 100 shareholders.

- Pay dividends of at least 90% of the REIT’s taxable income each year.

- Have no more than 50% of its shares held by five or fewer individuals during the last half of each taxable year.

- Hold at least 75% of total investment assets in real estate.

- Have no more than 20% of its assets consist of stocks in taxable REIT subsidiaries.

- Derive at least 75% of gross income from rents from real property, interest on mortgages financing real property, or sales of real estate.

5.4. WHAT ARE THE FORMS OF A REIT DISTRIBUTION?

For tax purposes, dividend distributions are allocated to ordinary income, a return of capital, and capital gains when a REIT sells the property or another asset. Each of these distributions may have different tax rates. Thus, your return depends on the composition of the distributions for tax purposes, which may vary over time. A REIT sometimes distributes amounts higher than the income it could theoretically distribute. In such cases, the surplus distribution may be considered a return of capital, which reduces the cost basis of your shares for tax purposes. In other words, if you sell your shares, you pay capital gains tax on the difference between the selling price and the adjusted cost basis at the time of sale. This difference is called a deferred tax. The trust may use income not distributed to acquire other properties or to provide a reserve for maintaining distributions in lean years. The REIT must pay taxes on the amounts retained.

5.5. WHAT ARE THE MAIN TYPES OF REITS?

Not all REITs are the same. Instead, they come in several varieties with differing attractions and risks. REITs are normally classified by their type of holdings – equity or mortgage. REITs generally own real property or interests in real property and loans secured by real property or interests in real property.

- Equity REITs (eREITs). As the most common type of REIT, eREITs acquire, manage, and develop income-producing properties (hard assets) in such areas as office and industrial, retail, and residential among many others. eREITs are attractive for long-term investing because they earn dividends from rental income as well as capital gains from the sale of properties. These REITs generally have relatively low volatility and consistent income. However, they may use leverage (borrowed money) to increase the percentage return on investment and value of the REIT shares, which increases risk. REITs tend to use moderate levels of debt in their capital structures. In fact, the average REIT debt ratio has been below 55% for much of the last decade. However, the REIT industry is less leveraged than at any point in the past two decades. The National Association of Real Estate Investment Trusts (NAREIT) reports 181 eREITs at the end of 2017. For example, American Tower (NYSE:AMT) is a global REIT that owns and operates communications towers. Equity Residential (NYSE:EQR) is an apartment REIT that owns more than 300 properties

- Mortgage REITs (mREITs). mREITs invest indirectly in real estate by providing financing for the income-producing real estate by purchasing or originating mortgages and mortgage-backed securities (MBS) and earning income from the interest on these investments. mREITs use considerable leverage in order to generate high dividends for shareholders. They generate income by borrowing money at low short-term rates and investing in longer-dated mortgages that pay higher interest rates. mREITs can be a good speculative investment if interest rates are expected to drop because the interest on the mortgage loans is often “locked in” at a higher rate. However, increasing interest rates can quickly erode profits. Thus, the chief risk facing mREIT investors is interest-rate fluctuations. NAREIT reports 41 mREITs at the end of 2017. For example, Annaly Capital Management (NYSE:NLY) is the largest, and perhaps best known of the mortgage REITs. Starwood Property Trust (NYSE:STWD) is the largest commercial mortgage REIT in the United States.

- Hybrid REITs (hREITs). hREITs own a combination of equity and mortgage REITs. Thus, they both own property and make loans to real estate owners and operators. Hence, hREITs earn money both through rents and interest. In practice, hREITs tend to be more heavily weighted to one type of investment than the other and are relatively rare. Two Harbors Investment Corp. (NYSE:TWO) is a hREIT that invests in residential mortgage-backed securities, residential mortgage loans, residential real properties. and other financial assets.

5.6. HOW DO PUBLICLY TRADED AND NON-TRADED REITS DIFFER?

Although the most common way of investing in a REIT is to buy one on a major stock exchange, non-traded public and private REITs are also available.

- Publicly traded REITs. Exchange-traded REITs are

registered with the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC),

and their shares trade on major stock exchanges. The shares of most

large REITs are listed with 190 REITs trading on the New York Stock

Exchange (NYSE). Publicly traded REITs are usually self-advised and

actively managed.

– Pros. These REITs are generally large and diversified, simple to buy or sell through a brokerage account with a minimum of one share, make regular financial disclosures, and offer great liquidity and ability to track their performance.

– Cons. Running a publicly traded fund involves additional expenses that can reduce your dividends. Market conditions can affect share prices leading to volatility.

- Public non-listed REITs. Non-listed REITs are subject

to the same SEC requirements as publicly traded REITs but don’t

trade on national stock exchanges. You must meet the minimum net

worth or liquidity guidelines. These REITs are designed to be held

for a certain period, usually between five and seven years, and pay

a pre-declared (set) dividend. They are typically externally

advised and managed.

– Pros. Public non-listed REITs have a fixed price that provides some insulation from market fluctuations (volatility) because they don’t trade on a daily basis, make regular financial disclosures, and often offer higher dividends and greater appreciation at the end of the holding period. They may also offer higher returns than other fixed-income investments such as bonds but with higher risks.

Look at market fluctuations as your friend rather than your enemy; profit from folly rather than participate in it.

Warren Buffett

– Cons. Compared to publicly traded REITs, shares of public non-listed REITs are more difficult to buy and sell, generally much less liquid, offer less transparency of fund operations, and are more expensive due to front-end fees as much as 15% of the per share price paid to the sponsor and its affiliates. The share price and dividends aren’t guaranteed despite being “set.” The lack of a public trading market also creates valuation and illiquidity complexities. These REITs may offer limited annual redemption programs to provide some liquidity to you. Early redemption is often restricted due to minimum holding requirements and may be expensive. Diversification can be limited and properties may not be specified. Public non-listed REITs normally require an initial investment of $1,000 to $2,500.

- Private REITs. A private REIT, or private-placement

REIT, is an offering that is generally exempt from SEC

registration and whose shares don’t trade on an exchange. In the

United States, private REITs are generally sold to institutional

investors and “accredited investors,” generally defined as

individuals with a net worth of at least $1 million (excluding

primary residence) or with income exceeding $200,000 over the two

previous years ($300,000 with a spouse). Private REITs are usually

externally advised and managed.

– Pros. Private REITs are potentially tax-advantageous vehicles for private investment funds.

– Cons. Private REITs carry substantial risks to you because they are hard to value and trade and aren’t subject to the same disclosure requirements as public non-traded REITs. Transaction costs in terms of upfront charges can be high. You can pay up to 12% in marketing fees and commissions to the brokers who sell them. Additionally, private REITs generally underperform public REITs. No public or independent source of performance data is available for tracking private REITs. Private REITs that are designed for institutional or accredited investors generally require a high minimum investment, such as $1 million.

Given the additional complexities and risks associated with non-listed REITs either public or private, they aren’t as popular as publicly traded REITs. Private REITs may be an appropriate vehicle for real estate investments by pension funds, hedge funds, or private equity funds but not for inexperienced investors.

5.7. WHAT ARE THE MAJOR REIT SECTORS?

REITs represent an intricate ecosystem of sectors that touches every corner of the economy, including retail, residential, infrastructure, healthcare, office, industrial, data centers, self-storage, lodging/resorts, timberlands, mortgage, and others. The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) has approved REIT status for businesses not traditionally associated with the REIT structure, such as billboards, data centers, cell tower companies, and private correctional facilities. The economic conditions that drive performance often differ from one sector to another. The most popular sector is retail focusing on large regional malls, outlet centers, grocery-anchored shopping centers, and big-box retailers. Although REITs often focus on a particular property type, some hold multiple types of properties in their portfolios.

If you’re not going to put your money into real estate, where else?

Tamir Sapir

5.8. HOW DO INVESTORS BUY AND SELL REITS?

You can own REITs directly or access them through REIT mutual funds, ETFs, and closed-end funds (CEFs). The most common method is to buy and sell REITs traded on public exchanges, making the shares liquid and the holdings transparent. Thus, anyone can easily buy and sell shares in them. Some REITs, however, are non-listed or private and unavailable to the general public. Such REITs are sold by brokers but are much less liquid. Non-listed and private REITs have other severe downsides. For example, their prices may be set by the REIT sponsor or based on a net asset value (NAV) as determined by independent valuation firms. Private REITs typically require a much larger minimum investment than required to buy a single share of a publicly traded REIT. Private REITs also are usually open only to accredited investors, which the SEC defines as those who meet certain minimum criteria for net worth, income, and investment knowledge (see https://www.sec.gov/files/review-definition-of-accredited-investor-12-18-2015.pdf). Thus, private REITs are generally sold to institutional investors. Given that they are non-exchange-traded, getting out of these investments can be difficult. Furthermore, private REITs are often not as diversified as publicly traded REITs and have no track records. As a consequence, private REITs are an investment choice that individual investors should usually avoid.

5.9. HOW DO REITS AND THEIR INVESTORS MAKE MONEY?

REITs characteristically own and/or manage income-producing commercial real estate, either the properties themselves or the mortgages on those properties. Thus, eREITs make money from the properties they buy by renting, leasing, or selling them. mREITs deal in investment and ownership of property mortgages. They loan money for mortgages to owners of real estate or buy existing mortgages or MBS. mREITs primarily generate revenues by the interest that they earn on the mortgage loans. You make money on REITs through dividends and share price appreciation.

Rule No. 1: Never Lose Money. Rule No. 2: Never Forget Rule No. 1.

Warren Buffett

5.10. WHAT ARE THE ADVANTAGES OF OWNING A REIT?

REITs offer many advantages to investors.

- Ease and cost of acquisition. You can buy and sell a

listed REIT, just like any other public stock. By owning a REIT,

you avoid the costs and hassles of finding, financing, and managing

the property. Your liability is also limited to the extent of

investment in the REIT. Most REITs enable those who may have only a

small amount of capital to participate in investments otherwise

available only to sophisticated or institutional investors. For

example, Fidelity Real Estate Investment (FRESX) has a minimum

investment of $2,500 and Vanguard Real Estate Index Investor

(VGSIX) requires a minimum investment of $3,000.

The beauty of diversification is it’s about as close as you can get to a free lunch in investing.

Barry Ritholtz

- Portfolio diversification. REITs can be a good portfolio diversifier for several reasons. First, REITs invest in multiple properties, so one underperforming property won’t ruin your portfolio. Second, the correlation of listed REIT stock returns with the returns of other equities and fixed-income investments is relatively low. In simple terms, REIT returns tend to “zig” when those of other investments “zag.” This characteristic helps to dampen a portfolio’s overall volatility and improve its returns for a given level of risk. Because REITs must annually distribute almost all of their rental and capital income as dividends to shareholders, such distributions can reduce portfolio volatility. Investing in international REITs also provides tangible diversification benefits. Thus, REITs can be an important part of a well-diversified portfolio.

- Transparency. Publicly traded REITs are highly transparent investment vehicles. Trading on major exchanges enables market participants to determine their historical return characteristics and to compare them with other investments. The severe restrictions on possible investments and dividend payout also contribute to their transparency. REITs provide audited financial reports and other disclosures as required by the SEC. Various parties such as analysts and financial media monitor the performance and outlook of listed REITs.

- Taxes. As a pass-through entity, a REIT doesn’t have

to pay corporate federal or state income tax as long as it

maintains its tax-qualified status by paying out 90% of its net

income to common shareholders. Instead, shareholders bear the

responsibility of paying these taxes. Thus, REITs offer

tax-efficient exposure to the real estate market by avoiding the

double taxation of income and have greater profits from which to

pay shareholder dividends. However, REITs still face corporate

taxation on any retained income and you’re taxed at your individual

tax rate for the ordinary income portion of the dividend.

It’s not how much money you make, but how much money you keep.

Robert T. Kiyosaki

- Competitive long-term performance. Historically, REITs have provided relatively stable dividend yields. Why? REITs must pay out at least 90% of their income as dividends. Additionally, many REITs generate income from commercial properties with long lease periods. Investors interested in yield have usually done better investing in REITs than fixed-income securities and S&P 500 stocks. For example, in May 2018 the yield on FTSE NAREIT All Equity REITs was 4.11% compared with 1.95% on the S&P 500 index.

- Inflation protection. REITs can serve as a natural inflation hedge if their growth and value increase at a higher rate than inflation. eREITs are somewhat resistant to inflation because they can adjust rental incomes in line with the cost of living. REITs may also experience growth of their underlying assets and an increase in share prices, especially during periods of inflation. Historically, REIT dividends have usually outpaced inflation as measured by the Consumer Price Index (CPI). REITs offer dividend growth and provide a reliable stream of income even during inflationary periods. Rental income in public REITs may provide a partial hedge against inflation, but the price component of REITs is highly correlated with stocks. A 2018 study conducted by NAREIT shows that returns on REITs exceeded the inflation rate during 68% of the six-month periods when inflation was relatively high since 1978.

- Liquidity. Publicly traded REITs are more liquid than other real estate investments because you can buy and sell your shares quickly on the major stock exchanges.

- Professional management and corporate governance. Publicly traded REITs are professionally managed and follow the same corporate governance principles applicable to all major public companies. REITs have become increasingly sensitive to corporate governance developments, and many REITs have adopted important governance enhancements.

5.11. WHAT ARE THE DISADVANTAGES OR DRAWBACKS OF REIT OWNERSHIP?

REITs have various disadvantages.

- Fees and costs. REITs can involve numerous fees and

costs, including management fees, trustee fees, legal fees,

administration fees, audit fees, transaction fees, and even

brokerage fees for the sale and purchase of these REITs. Compared

to publicly traded REITs, those that are non-publicly traded often

have higher management and transaction fees that can lead to lower

payouts for shareholders.

There is always risk. Your job is to learn to manage risk rather than avoid it.

Robert T. Kiyosaki

- Risks. REITs have the same risks as stocks but with additional emphasis on interest-rate risk. Because REITs generally offer a higher dividend yield than stocks, they can be more sensitive to interest-rate movements. REITs also have investment risk, which is the level of uncertainty of achieving the returns based on the investor’s expectations. Real estate slumps or financial crises could negatively affect occupancy rates and revenues leading to declining share prices when property values fall. Hence, no assurance exists that a REIT will be profitable. You can lose money. However, all REITs aren’t created equal. Some are in a better position to survive economic downturns and market upheavals than others. Like other sectors, the real estate rental market is cyclical, with periods of growth and downturn. Given the higher costs associated with non-publicly traded REITs, these REITs must take greater risks to achieve the same return as publicly traded REITs.

- Lack of diversification. Although some REITs own different classes of property in various geographic locations, many REITs specialize in a single property type. Thus, investing in a REIT that focuses on a single type of property could leave you vulnerable to a particular economic weakness. To lessen the risk associated with a decrease in income, some REITs diversify not only the types of real estate properties held in their portfolios but also geographically.

- Taxes. You must pay taxes on the distributions you receive from a REIT. These distributions to investors keep their original form. For instance, if a REIT distributes what it originally received as rental income, you’re taxed as though you had received rental income. The composition of these distributions for tax purposes may change over time, thereby affecting your after-tax returns. Unfortunately, REITs don’t pass tax losses and other expenses, when they exceed operating income, through to their shareholders.

- Limited growth. Given that REITs must pay at least 90% of income to investors, little remains to reinvest in the business, which could limit growth. As a result of high dividend payouts, management could decide to take on additional debt to expand its real estate holdings.

5.12. WHY DO TRADITIONAL METRICS NOT WORK WELL WHEN EVALUATING REITS?

Traditional metrics such as earnings per share (EPS), price-to-earnings (P/E), and price-to-book (P/B) are often unreliable when applied to REITs. Why? Businesses must depreciate tangible assets such as plant and equipment in accordance with IRS rules about how and when the deduction may be taken. For most businesses, the purpose of recording depreciation as an expense is to spread the initial cost of the asset over its useful life. As a result, the asset’s book value decreases over time. However, real estate differs from most investments in plant and equipment because property loses value infrequently and often appreciates. Therefore, net income, a measure reduced by depreciation, is an unreliable measure of performance. As a result, evaluating REITs should rely on other metrics.

5.13. WHAT ARE THE COMMON METRICS USED TO ASSESS REITS?

The following are useful metrics in evaluating REITs.

- Funds from operations. REIT professionals often use funds from operations (FFO) to measure a REIT’s operating performance. FFO is calculated by adding the expenses or losses, which aren’t actually incurred from the operations, such as depreciation, amortization, and any losses on the sale of assets, to net income, and then subtracting any gains on the sale of assets and interest income. It is sometimes quoted on a per share basis. FFO can provide a more accurate picture of the REIT’s cash performance than net income (earnings), which includes non-cash items such as depreciation that isn’t an actual cash outflow. Unfortunately, prescribing a specific percentage of distributions to FFO is difficult because circumstances differ among REITs.

- Adjusted funds from operations (AFFO). AFFO is another measure of a REIT’s cash flow generated by operations and ability to pay dividends. AFFO is generally equal to the REIT’s FFO with adjustments made for recurring capital expenditures used to maintain the quality of the REIT’s underlying assets. Because the methods used to calculate AFFO may vary among REITs, this method isn’t ideal to compare one REIT to another.

- Net asset value. NAV is calculated as the actual value of a REIT’s properties based on an assessment of properties’ market value minus its debt or mortgage liabilities. However, this subjective measure is only as good as the analyst’s assessment of each REIT holding. Dividing the REIT’s NAV by the number of shares outstanding provides the intrinsic value per share. In this context, intrinsic value refers to the real or actual value of a REIT. In theory, a REIT’s price should equal its intrinsic value, but in practice, this relation doesn’t always hold. Comparing a REIT’s share price to its intrinsic value indicates whether its shares trade at a premium (share price exceeds the intrinsic value) or at a discount (intrinsic value exceeds the share price). A positive price minus intrinsic value indicates that you could purchase all of the REIT’s properties more cheaply outside of the REIT itself, suggesting it is overvalued. If the price minus intrinsic value is negative, the properties are worth more outside the REIT, making it undervalued by the market.

- Net operating income (NOI). NOI is a calculation used to analyze real estate investments that generate income. NOI is the annual income generated by an income-producing property after taking into account all income collected from operations and deducting all expenses incurred from operations.

- Capitalization rate. The capitalization rate, also called the cap rate, is a rate that helps in evaluating a real estate investment. The cap rate is calculated by dividing NOI by the property’s purchase price. For example, if a property recently sold for $1,000,000 and had an NOI of $100,000, then the cap rate would be $100,000/$1,000,000, or 10%. The cap rate indicates a real estate investment’s potential rate of return. The higher the cap rate, the better is the annual return on the investment. That is, you want to have a high cap rate, meaning the property’s value or purchase price is low.

- Leverage. Leverage refers to the amount of

debt a firm uses to finance its assets. Numerous measures of

leverage are available, such as the debt ratio and debt-to-equity.

For example, the debt ratio is calculated by taking a

REIT’s amount of total debt over its total assets. A REIT with a

lower debt ratio has less debt, is more conservative, and is less

vulnerable to market fluctuations. Higher leverage doesn’t

necessarily mean that a REIT is a poor investment, but that it

takes on more debt and risk to achieve potential growth.

You really don’t need leverage in this world much. If you’re smart, you’re going to make a lot of money without borrowing.

Warren Buffett

- Coverage ratio. The coverage ratio measures the ability to pay the property’s mortgage payments from the cash generated from renting the property. It can be calculated in several ways. One method is to divide the property’s annual NOI by its annual debt payments, which include the principal and accrued interest. Thus, a coverage ratio of 4 to 1 indicates that for every dollar of debt payments, the REIT generates $4 in NOI. A high coverage provides a cushion that the REIT can pay its debt even during bad economic conditions. A coverage ratio of at least 4 serves as a good guideline. Another method of calculating debt coverage used by NAREIT is to divide earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA) by interest expense. During 2017, the FTSE NAREIT Equity REIT Index had debt coverage of 4.6 times.

- Occupancy rates. The occupancy rate is the ratio of rented or used space for the total amount of available space. What constitutes a good occupancy rate depends on the rental market in a specific location. As a general guideline, an occupancy rate of 95% is good for landlords, and rents are likely to increase. Thus, higher occupancy rates or lower vacancy rates are better and lead to a more stable income.

- Yield and growth. Another method of choosing REITs is to compare their dividend yields to those of other asset classes, such as corporate bonds. Comparing them allows you to gauge how the market values the yields for each. A higher yield suggests that you’re getting the dividend stream for a lower price. Dividend yield is calculated by dividing the end-of-period dividend by the beginning-of-period stock price on a per share basis. A REIT that can steadily grow its income and dividends per share over time is more attractive than one whose dividend payouts fluctuate widely. Thus, a good sign of continued good REIT health is a steadily rising distribution rate. Another yield measure uses a REIT’s FFO. To obtain the yield, divide the dividend per share by the FFO per share. Higher yields are usually better.

- Property yield. Property yield is the amount of income a REIT can generate from a property divided by the value of the property. Although higher property yields are better, you should prefer a REIT’s property yield that is stable or rising over time.

5.14. WHAT GENERAL FACTORS SHOULD INVESTORS CONSIDER WHEN EVALUATING A REIT?

If you’re considering investing in REITs, here are several guidelines to consider.

- Types and quality of assets held. Investors build

portfolios around a set of objectives and constraints. Thus, if

you’re considering adding REITs to your portfolio, the types of

assets in which a REIT invests should be consistent with your

objectives and constraints. eREITs invest in real estate

properties; mREITs focus on mortgages and construction loans; and

hybrid REITs invest in a combination of the two. Each type of REIT

has its own risks. Your risk tolerance should be consistent with

the higher risk associated with REITs using leverage. If not, you

should avoid riskier REITs. REITs often specialize in a certain

sector, which affects their riskiness. If you’re considering

investing in a non-traded REIT, you could end up holding shares for

at least five years before seeing a return of principal. You want

to make sure you can handle this potential lack of liquidity.

Quality also counts, so invest in REITs with great properties and

tenants.

– eREITs. eREITs are generally a safer option than mREITs due to their relatively low volatility and consistent income. Additionally, property values can increase over time. Thus, eREITs offer a combination of income and property appreciation, which can produce strong total returns with relatively low risk. Consequently, eREITs tend to appeal to more conservative investors. However, the variation in annual performance at the REIT subsector level can be substantial.

– mREITs. mREITs attract investors who are willing to take greater levels of risk in search of high returns. mREITs are subject to a host of risks. The biggest is interest-rate risk, which is the inverse relation between interest rates and value. Thus, as interest rates rise, older securities that pay less lose value. mREITs also suffer from prepayment risk, or a loss of expected income. If mortgage rates fall, homeowners often refinance, using new loans to pay off the old ones. As a result, an mREIT that owns mortgages no longer gets interest payments from those homeowners. Instead, an mREIT receives principal payments that it re-invests in new mortgages that provide lower yields than the previous ones.

– hREITs. hREITs offer investors a blend of the characteristics of eREITs and mREITs. They can provide relatively balanced exposure to the economic factors that drive real estate valuations. As a result, hREITs more closely track the performance of the broader REIT indexes.

- Level of diversification. REITs often specialize in a specific sector, which affects their riskiness. For example, REITs holding retail shopping centers in a weak economy carry greater risk than high-end apartments in a major metropolitan area. Other REITs focus on investing locally rather than in a broad geographic area, which tends to be riskier.

- Management quality. Although strong management is important, evaluating management quality isn’t a straightforward process. However, one indicator of quality is to have an experienced management team. The REIT’s long-term performance can also be an indicator of management quality. A well-run REIT relies on its operations to pay for expenses and dividends.

- Performance and future expectations. As with all financial investments, the past performance of REITs doesn’t necessarily predict their future performance. Factors to consider involving future expectations are interest rates, demand, and residential and commercial rental prices. In guiding your choice, you should consider a strong total return rather than just high dividend yield.

5.15. WHO SHOULD INVEST IN REITS?

REITs are potentially attractive to a wide range of investors from individual investors to family offices, which are private wealth management advisory firms that serve ultra-high-net-worth investors, and also to institutional investors such as pension funds, endowments, foundations, insurance companies, and bank trust departments. Given their diversity, REITs are attractive to different investors and represent a good addition to a diversified portfolio. If you have a limited amount of capital to invest, the best way to hold real estate is through a REIT. In general, REITs are attractive investments for those planning to invest for stable, passive income. As a result of their tax advantages, REITs can offer investors higher returns with relative stability. mREITs are particularly attractive to dividend or yield-oriented investors because they offer an ongoing income stream that usually exceeds the yields on investment-grade bonds. However, savvy investors know that higher yields are associated with higher risks. Although eREITs also offer the potential of moderate long-term capital gains through share price appreciation, you have less incentive to hold the stock for capital gains as opposed to dividends. Hybrid REITs are total return investments because they provide high dividends plus the potential for moderate, long-term capital appreciation.

REITs are particularly attractive to retirement savers and for retirees requiring a continuing income stream to meet their living expenses. Because REIT dividends are taxed as ordinary income, they don’t qualify for a lower preferential rate due to the REIT not paying any corporate income tax. Hence, the high tax rate on dividends makes REITs preferable for retirement accounts such as Individual Retirement Accounts (IRAs) and other tax-deferred accounts.

5.16. HOW HAVE REITS PERFORMED OVER TIME, AND WHAT FACTORS DRIVE REIT PERFORMANCE?

Not surprisingly, REIT performance varies over time and by type and sector. Although various methods are available to evaluate performance, one approach is to use the FTSE NAREIT US Real Estate Index Series, which tracks the performance of the US REIT industry both at an industry-wide level and on a sector-by-sector basis. This index consists of 225 REITs. These data are available at https://www.reit.com/data-research/reit-indexes/ftse-nareit-us-real-estate-index-historical-values-returns. From the beginning of 1972, when the All US REITs Index was created, through the end of 2017, total return averaged 9.72% a year. The average annual industry performance for various periods ending in 2017 follow: five years (9.90%), 15 years (10.62%), 25 years (10.47%), 35 years (9.86%), and 45 years (9.69%). These data show that REITs have delivered reasonably steady returns over long periods.

In the business world, the rearview mirror is always clearer than the windshield.

Warren Buffett

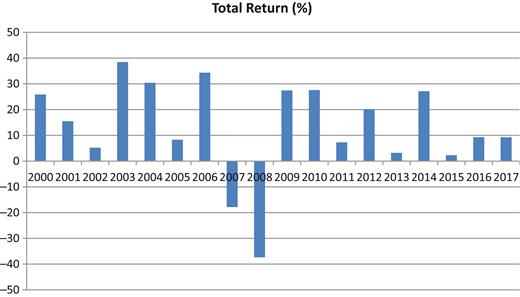

However, contrary to popular belief, REITs don’t deliver steady returns all the time. As Figure 1 shows, the annual returns of the FTSE NAREIT All REITs Index vary substantially on a yearly basis between 2000 and 2017. During this period, the FTSE NAREIT All REITs Index experienced negative returns only during the financial crisis of 2007–2008 with returns of −17.83% in 2007 and −37.34% in 2008. It began with a crisis in the subprime mortgage market in the United States in 2007 and developed into a full-blown international banking crisis, also called the global financial crisis.

Figure 1. Total Returns on the FTSE NAREIT All REITs Index.

Note: This figure shows the total

returns on the FTSE NAREIT All REITs Index between 2000 and

2017.

Source: Adapted from

https://www.reit.com/data-research/reit-indexes/annual-index-values-returns.

NAREIT provides a list of REITs funds containing the following information for each fund (https://www.reit.com/investing/reit-funds/table).

- Fund name

- Share class type

- Morningstar rating

- Performance overall year-to-date (YTD) (%)

- Performance overall 3-year (%)

- Performance overall 5-year (%)

- Expense ratio (%)

- Net assets ($ millions)

- Minimum investments

5.17. HOW CAN CHANGES IN THE LEVEL OF INTEREST RATES AFFECT PUBLICLY TRADED REITS?

One risk that can affect REITs is interest-rate risk, which is a risk that an investment’s value will change due to a change in the level of interest rates. Conventional wisdom suggests that rising interest rates can hurt profitability and share prices. As interest rates rise, asset prices often fall because investors perceive higher interest rates lead to a lower present value of an investment’s future cash flows. If future cash flows aren’t expected to rise, such as income from bonds, then an increase in interest rates would negatively affect their asset values. For eREITs using leverage, higher interest rates could lead to higher borrowing costs to acquire additional properties, which in turn can affect the REIT’s growth and cash flows. For mREITs, increasing interest rates reduce the purchasing power of the funds generated from the fixed interest from mortgages and construction loans. Additionally, rising interest rates could make other fixed-income securities such as Treasuries more attractive and draw funds away from REITs, resulting in lower share prices.

It’s sort of like a teeter-totter; when interest rates go down, prices go up.

Bill Gross

Although these scenarios are certainly possible, economic growth is often associated with rising interest rates. Economic growth can help drive earnings growth for eREITs, which in turn can lead to higher occupancy rates, stronger rent growth, increased FFO and NOI, and rising property values, higher dividend payments to investors, and risking share prices. Historical evidence by NAREIT shows that share prices of listed eREITs have more often increased than decreased during periods of rising interest rates. For example, according to NAREIT, REITs posted positive total returns in 87% of episodes of rising Treasury yields between 1992 and 2017 and also outperformed the S&P 500 index in more than half of the episodes of rising Treasury yields during that period. Thus, investor perceptions of the impact of rising interest rates on exchange-traded eREITs can differ from reality.

5.18. WHAT IS THE ECONOMIC IMPACT OF REITS?

REITs have an important impact on the economy, investor portfolios, and local communities. For example, US REITs have contributed to an estimated two million jobs in the economy. REITs own about 511,000 properties in the United States. mREITs have helped finance 1.8 million US homes. The US REIT industry has grown to a $1 trillion equity market capitalization representing nearly $3 trillion in gross real estate assets. More than $2 trillion of that total is from publicly listed and non-listed REITs and the remainder from privately held REITs. Currently, an estimated 80 million Americans have invested in REITs directly or through REIT mutual funds or ETFs. The inclusion of REITs in 2001 in the Standard & Poor’s Indexes underscores the importance of REITs in public capital markets and recognizes the integral role they play in the economy and diversified investment portfolios. About 32 REITs are members of the S&P 500 index.

5.19. WHAT FACTORS CONTRIBUTE TO REIT EARNINGS AND HOW ARE EARNINGS MEASURED?

REITs experience growth in earnings by generating higher revenues, reducing costs, and engaging in new business opportunities. The most direct way of achieving immediate revenue growth is by increasing occupancy and rental rates. Additionally, REITs can enhance their earnings through property acquisition and development programs as long as the economic returns from these investments exceed the financing costs. You can measure REIT earnings using net income supplemented with FFO.

5.20. HOW MUCH OF AN INVESTOR’S PORTFOLIO SHOULD BE REITS?

The answer to this question depends on the investor. No hard guideline is available concerning how much of a portfolio should be invested in REITs. For retail investors, 5% to 10% allocation is a reasonable starting point. According to NAREIT, studies reveal an optimal percentage between 5% and 15%. Ralph L. Block, the author of Investing in REITs, advocates more along the 15% to 20% line for an average investor portfolio.

5.21. WHAT QUESTIONS SHOULD INVESTORS ASK BEFORE INVESTING IN REITS?

Before investing in REITs, you should reflect upon the following questions:

- Why are you considering buying a REIT? That is, what makes REITs attractive to you?

- Is investing in a REIT consistent with your financial objectives and constraints?

- In what types of investments does the REIT invest?

- Does your portfolio have sufficient diversification?

- How will investing in a REIT affect your overall portfolio?

- What’s your investment timeframe?

- What specific risks are associated with the REIT you’re considering?

- What’s the REIT’s liquidity?

- How will your distributions be taxed?

- What’s the REIT’s expected total return in terms of dividend payout and potential capital appreciation?

- How will market forces likely affect your distributions?

- How much are the fees and costs associated with the investment?

- Does the REIT use leverage? If so, how much?

- What is the quality of the REIT’s management and corporate governance?

- What is the investment manager’s historical performance?

- What is the long-term outlook for this REIT?

5.22. WHAT ARE SOME ONLINE RESOURCES FOR REITS?

Here are several online resources for REITs.

- The NAREIT (http://www.reit.com) maintains an extensive website on REITs.

- The Securities and Exchange Commission (https://www.investor.gov/introduction-investing/basics/investment-products/real-estate-investment-trusts-reits) offers advice on REIT investing.

- The Financial Industry Regulation Authority (FINRA) (http://www.finra.org/investors/alerts/public-non-traded-reits-careful-review) provides an alert involving investing in public non-traded REITs.

- Dividends.com (http://www.dividend.com/dividend-stocks/reits-dividend-stocks.php) provides a list of individual REITs and REIT ETFs (http://etfdb.com/etfdb-category/real-estate/) including information about each type.

5.23. TAKEAWAYS

If you’re interested in investing in an income-generating alternative to buying property directly, REITs might be an attractive investment. During a low-interest-rate environment, investors often consider adding exposure to REITs to potentially improve the yield characteristics of their portfolio. However, you should not consider a REIT a fixed-income investment. As with any investment, you have no assurance about the profitability or growth in value when investing in a REIT. Therefore, you should do your homework or due diligence before investing.

Properly chosen REITs offer many benefits, including ongoing current income, potential long-term capital appreciation, and portfolio diversification. Although dividends are often relatively stable, they aren’t guaranteed. When you’re ready to invest in a REIT, don’t focus solely on the amount of its distributions. Instead, you should consider other factors such as earnings and dividend growth, the quality of its assets and management, costs, and new business opportunities.

REITs also have drawbacks. Some REITs have high management costs and fees. If held in taxable accounts, REITs provide dividends that are taxed as ordinary income. Yet, tax losses, which may result from depreciation and other expenses exceeding operating income, aren’t passed through to shareholders.

If you’re a nonprofessional investor, you should avoid investing in non-traded REITs, especially private REITs, due to their underperformance, high commissions and fees, illiquidity, and lack of transparency. Publicly traded REITs offer a safer playing field and tend to be less complex. If you’re a do-it-yourself investor, you need to clearly understand how specific REITs fit in your portfolio. Conducting due diligence is time-consuming and requires effort. Don’t invest in something that you don’t understand because it’s a recipe for disaster. You can also seek the advice of a trusted investment advisor or financial planner who understands the product in order to review it and can offer impartial advice before undertaking such an investment.