~17~

PRINCESS MINA AND

THE GOBLINS

By the time Max emerged from the well’s depths, the storm had long since disappeared. There was a nip in the air, but that air was clean and most welcome after his ordeal far below the earth. It was early morning, the specter of the full moon still visible in a dawn sky of pale peach. The farmhouse was still shuttered, but smoke was issuing from its squat chimney. Glancing at the waterlogged pen, Max saw that the sheep and goats had resumed their placid demeanor.

In the daylight, Max examined his wounds more closely. His neck was horribly stiff, and both his forearms were ringed with ugly sores, but already these seemed to be healing. There was no trace of the wound from Pietro’s knife. Although Max was exhausted, what he really desired was a bath so that he could remove every trace of the nauseating tunnels and the cavern’s rank pool. That would come; first he needed to check on Mina.

Something had been propped behind the broken door so that it could be secured into place. Max had to knock and call several times before he finally heard an angry hiss and the sound of furniture being dragged away. Wobbling on its remaining hinge, the door nearly fell in before Max caught it and looked upon the tired, anxious face of the young mother.

“Good morning,” he said.

“The—the monster?” she gasped, looking past him.

“The monster is dead.”

The woman put a trembling hand to her mouth and leaned heavily against the table. Motioning Max to enter, she turned and went to the bottom of the stairs, where she spoke too rapidly for him to follow the Italian. Walking inside, Max recoiled again at the greasy, soot-filled space.

“What is your name?” he asked, opening some nearby shutters to let in some fresh air.

“Isabella,” replied the woman, looking worried. “Pietro is drunk … sleeping. He can’t talk to you.”

“I don’t need to see him,” said Max, putting his sword and the salvaged papers on the table. “I need to see the children, Isabella. Right now.”

Nodding, Isabella went upstairs and soon returned with them in tow. To Max’s relief, he saw Mina among them, still wrapped in his woolen coat. None of the young ones met his gaze, but they obediently gathered around the fireplace while he pulled up a stool. The old woman also appeared, venturing halfway down the stairs to stare at him with black, calculating eyes.

While the children stood like zombies, Max explained that the monster was dead and that it could no longer hurt them. They barely reacted to the news, merely staring at Max. Max glanced at the oldest, a boy who looked to be in his early teens.

“What’s your name?”

The boy slumped as though forced to endure a lecture or scolding.

“You won’t get an answer from him,” said Isabella mildly. “He hasn’t spoken since he arrived. His name is Mario.”

“Mario,” said Max, shaking the limp, unresisting hand. “I’m Max. Can any of you share your names with me? I’m here to help you.”

A girl, perhaps eleven years old, looked at him with a pair of brilliant green eyes. “Is it really dead?” she whispered. “Are you sure?”

Max nodded.

“But how could you have killed such a monster?” asked Isabella.

Max shrugged and did his best to explain that he was trained for such things and had fought many battles. It was his job to protect people, and thus he needed to know why these children were here and living this way.

“Mind your own business!” hissed the old woman from the stairs.

“I will not,” replied Max calmly, turning to face her. “Are you responsible for sacrificing children to that monster?”

“There was nothing we could do!” she replied with an indignant scowl. “The vyes arrived one day and drove something into the well. Goblin carts came later with prisoners—children from the camps. We were told to leave one in the pen every full moon or the monster would come for us instead.”

“Why didn’t you simply leave?” asked Max. “Take the children and go elsewhere?”

The woman said nothing, merely shaking her head as though no answer would satisfy such an unreasonable inquisitor.

“The goblins control this valley,” explained Isabella. “Every few months, they bring more children and supplies.”

The old woman hissed at the younger woman, who coolly returned her stare.

Max stood and walked toward the crone, his anger quickening. “So, I’m to understand that you left children outside for a monster because you were too frightened to leave and you wanted the goblins to bring you things?”

“The goblins said we would be cursed if we left the monster untended,” said Isabella. “They said it was a demon and that we were bound to its care. They marked us with the well.…” Holding up her palm, she showed Max the same tattoos borne by Pietro—the seal of Astaroth followed by those of Prusias and the well. “The goblin said that the monster could always find us by this mark, that we could never escape.”

“None of that justifies what you’ve done,” muttered Max, disgusted with the whole business. He stared hard at Isabella, who faltered and looked away. “Are Pietro and this woman your parents?”

“No,” she said. “My husband was killed during the war. I fled the city and found this place. Ana and Pietro took me in, helped me birth my daughter. You mustn’t be too angry with them. Pietro wept whenever a stone was picked.”

Max remembered back to the piece of quartz lying on the table.

“No,” he snapped. “That wasn’t a stone—that was a child. They weren’t picking stones, Isabella. They were picking children to be left outside.”

“We are not soldiers like you!” spat Ana from the stairs. “And these are not our children! They were dropped on the doorstep. We had no choice.”

“Well,” said Max, “you have lots of choices now—you’re free to go any direction you choose.”

“What do you mean?” asked Ana.

“You will pack and leave,” said Max. “You cannot stay here anymore. This is the children’s home.”

At this announcement, Ana’s chin jutted forward, revealing a row of yellowed teeth. “Nonsense!” she hissed. “This is our house—we found it!”

“No,” said Max. “This was your house. It belongs to the children now—they’ve more than paid for it. You can either live down in the well or you can travel elsewhere. You have until midday to decide.”

“But there are goblins,” objected Ana. “Hobgoblins! We are defenseless!”

“Not defenseless,” said Max, walking over to the ancient spear that lay near the dozing spaniel. Picking it up, he thumbed its point and leaned it against the doorjamb. “This is more of a defense than you gave Mina. And if it’s just hobgoblins out in the wild, you’ll stand a chance.”

“It’s murder,” spat Ana.

“No,” Max replied. “It’s exile.”

“Are Gianna and I to go, too?” asked Isabella.

Glancing at her baby, Max shook his head. “I’m not sending a nursing mother away.”

With that, Max climbed the stairs and searched the rooms until he found Pietro sprawled in a snoring heap on a filthy mat. There was a bucket of water nearby, and Max dumped it onto the sleeping man, who promptly sputtered and peered drunkenly at him. Questions ensued, confused, mumbling inquiries that Max simply ignored as he helped Pietro to his feet and led him downstairs to where Ana was hunched near the doorway like a gargoyle.

While the children watched, Max explained the situation to the older man. Angry protests followed, with Pietro and Ana damning Max to eternity—how dare he drive them out into the wild! Had he no heart? At this, Max merely pointed to the pile of discarded shoes and began raiding the pantries and larders.

When he had packed some food, Max tossed the satchels at Ana’s feet and placed the spear in Pietro’s hand.

“I’d go west,” he advised. “I came from that direction and met no trouble. There are many springs, and the walking is not too hard. You are never to come here again or speak of this place. If you do, I’ll put a curse on you myself.”

As Max said these last words, he held forth his hands so that bluish witch-fire sprang from each. The flames danced across his fingers before rising into the air and splitting into several crackling bolts that ringed and orbited the bewildered pair.

“Daemona!” shrieked Pietro, clutching at his wife.

“Call me what you like,” said Max, leaning close and catching the sparks, which raced back to his hand. “But remember the curse, Pietro. Not a word about this place, these children, or me.”

It was a mere bluff, of course. Max didn’t know how to invoke anything as complex as a true curse. He doubted the goblins did either, but their threat had been sufficient to frighten Pietro and Ana so Max guessed a bit of pyrotechnics would be more than sufficient to ensure the couple’s silence. The last thing he wanted was for anyone to broadcast his whereabouts in Blys.

“Goodbye and good luck,” said Max, ushering them firmly out the door.

After a heated debate, the couple did not go west. Instead, they chose to travel northeast. They made a beggarly spectacle as they departed, Ana waddling beneath her mound of belongings and Pietro leaning on the old spear and prodding the dog. Had their crimes been less atrocious, Max might have been moved to let them stay. But they were murderers, he reminded himself, just as guilty and pitiable as the monster in the well.

“They will be all right,” said Isabella, bouncing her baby, who was cooing at her. “I think they’re off to Nix and Valya.”

“Who are they?” Max asked.

“Another couple who lives across the valley. They visit sometimes, bring the children presents.”

“Aren’t they afraid of the goblins?” asked Max, curious.

“They must be,” replied Isabella, “but they’ve lived in the valley a long time and seem to know its ways.” If the departure of Pietro and Ana had upset Isabella, she masked it well.

Once he had bathed his wounded limbs, Max ate and began to work. The children were still wary of him and merely watched as he set to lugging Pietro’s fermenting tub out of the house and dumping the rancid contents down the far slope. While the older boys and girls set about their chores, Max rummaged through the farmhouse and gathered what he needed.

He managed to scavenge some hundred nails, an old hammer, a saw, and a broom that was languishing within a crawl space. There were several unused buckets, some lye, and even a pot of red paint gathering dust upon a shelf. Of most immediate value was the shovel that Max discovered leaning against the house’s side. It was a rickety old thing but serviceable.

Throughout the day, Max made dozens of trips in and out of the house. With his shovel and a wobbly wheelbarrow, he carted away mounds of rotting hay, filthy laundry, and unconscionable mounds of waste. This he piled downwind from the house, whose windows stood open so that sunlight and cool air could rush into corners that had been moldering too long.

As the sun set, Max ignited the heaps of trash and watched the flames and smoke rise high into the spring twilight. The stars were beginning to twinkle, and the rich purples of the deepening sky reminded him of the long hikes he used to take with Nick when Nick had been a very young lymrill. He missed his charge dearly—not only for his snorting company, but also for his undeniable skills. The lymrill would have made short work of the rodents that no doubt infested the farmhouse.

When the piles finally burned to ash, Max walked wearily to the house, where firelight flickered from the windows. Far off, he heard a wolf’s mournful howl. It rose with the moon and trailed off to silence somewhere out in the dark valley.

Inside Isabella was making a stew using a freshly butchered lamb and some root vegetables that had escaped the rot of the wet cellar. Supper was held in relative silence. Max had decided to let the children adjust to the new circumstances in their own way. As the plates were cleared, he shuttered the windows and set the door back into place. At Max’s insistence, the filthy blankets had been gathered from upstairs and spread onto the floor before the fireplace. Everyone would sleep downstairs; the upstairs remained uninhabitable. Kicking off his boots, Max drowsed upon a chair and watched the golden firelight dance upon the walls while the children curled up on their blankets and drifted off to sleep.

As far as Max was concerned, it would be days—weeks, perhaps—until he could get the house in order and make his way north. That was his plan, as far as he had one. Somewhere to the north lay Vyndra’s lands, and Max was determined to find him.

* * *

The ensuing days were much the same. While the children went about their chores in the fields or animal pen, Max worked to make the house habitable. When all the trash had been removed and burned and the blankets washed and hung to dry, he set to scrubbing away the layers of dirt that had come to cover the walls, floor, and even the ceiling. It was wearisome work but quickly yielded appreciable results as soot gave way to clean stone, dark wood, and faded yellow paint.

As Max worked, he noticed that some of the younger children had taken to watching him. They stood in the doorway or lingered on the porch, thrusting tousled heads indoors as he repaired furniture, scrubbed baseboards, and scoured the kitchen until its tiles gleamed.

It was Claudia—a stout, inquisitive girl—who was the first to work alongside Max. She never said a word but simply picked up a nearby rag and helped him clean the fireplace and surrounding mantel. Marco soon joined them, followed by a mischievous boy named Paolo. Within the hour, eight of the children had ventured indoors and were scrubbing the walls alongside him.

Isabella watched this development with some amusement, but she said nothing as she looked after Gianna and supervised the work outside. Max’s disdain for her was evident; he had spared her exile only because of her baby and the fact that the children would need a caretaker after he had gone. Isabella seemed to sense this and was polite but reserved as she prepared meals from grain and whatever eggs the six hens produced.

At twilight, Max would wash his face and hands and hike far out over the hills, getting a better sense of the landscape and whether additional dangers lurked nearby.

It was stunning scenery, and as Max whipped the old estate into shape, he could envision what must have been a prosperous farm and influential family. But Max realized that, despite his efforts, those days were ancient history, and it would take much more than rags, water, mops, and brooms to restore the place to a thriving, secure home that could support these children.

Security was his primary concern. The monster from the well was dead, but he wondered if its presence had kept other things away. For now, all was quiet in the valley, but certain details continued to trouble him.

He discussed them with Isabella the following morning as she roasted old coffee beans in the fireplace. To date, Max had addressed Isabella only when absolutely necessary, and when he spoke, the children abruptly ceased in their chores to listen.

“The coffee,” said Max, gesturing at the burlap sack. “The tea and sugar. Those don’t grow here, Isabella. Where did you get them?”

“Nix and Valya brought them,” she explained, a tinge of caution in her voice. “On their visit before Yuletide.”

“Yuletide?” said Max, looking sharply at her and blowing on his tea. “Do you remember Yuletide, Isabella? Do you remember life before the demons? Before Astaroth?”

But Isabella would not answer this. She merely gazed at the fire, tossing the beans about in a long-handled metal basket thrust over the coals. Her mouth was grim, and Max perceived a growing sorrow in her eyes. Turning to the children, Max asked them to work outside so he could converse with Isabella alone. They obeyed, even Christopher, the most willful among them. When they had gone, Isabella removed the basket from the flames and went to check on her daughter.

“The past is too painful,” she said, adjusting the baby’s swaddle.

“Your past is your business,” said Max gently. “But there are others who visit this place—this Nix and Valya, for one. And you’ve mentioned goblins. I’m asking because I want to ensure that the children will be safe with you after I’m gone.”

Isabella’s shoulders stiffened. “Gone?” she exclaimed, turning to him. “But where are you going?”

“There will be a day when I leave this place,” said Max quietly. “I have business of my own.”

“Oh, but you can’t!” Isabella protested, plucking at her baby’s blanket. “You are an angel sent to protect us! I prayed and prayed for deliverance from the evil and here you came!”

“I’m not an angel,” said Max. “I’m just a boy from across the sea.”

“But you perform miracles,” she declared.

“Listen,” said Max. “I can’t stay here forever. I will help with the spring planting and finishing up the house, but the most important thing I can do is deal with the goblins. They will come here again, Isabella, with more prisoners for the monster. But that monster is dead. The goblins will eventually learn this. Do you think they will simply leave you be?”

“So what will you do?” she asked.

“Have a talk with them,” he said, eyeing the sword that hung upon the wall.

“But we need the goblins,” Isabella blurted. “They bring grain and livestock. We will die without them!”

Pacing about, Max mused upon this dilemma while Isabella began to methodically mix grains and milk for Gianna’s breakfast. At last he had an idea.

“When do the goblins visit here?” he asked.

“Every other month,” replied Isabella. “Around the quarter moon—they do not want to be near when the monster is active. They will be coming soon.”

Max nodded and stood up to stretch.

“What will you do?” she asked again nervously.

“Nothing to endanger you or cut off your supplies,” he said, putting on his boots and thrusting his hand out a window to gauge the chill. “Don’t mention this conversation to the children.”

But the children were particularly perceptive. If they had displayed a tendency to cluster around him before, they shadowed him with the same watchful diligence as Hannah’s goslings. They seemed to sense that Max might be leaving, and wished to keep him in their sight.

The children were not merely perceptive; they were resilient. Within days of the monster’s death and Pietro’s departure, Max heard them whispering to one another, studying him when they thought he was oblivious. Now they offered shy smiles at his approach, and the round lump of a six-year-old they called Porcellino had even taken to showing Max his muscle.

“Very impressive,” said Max, stooping to pinch the small, soft arm while its owner’s face blazed red with strain. “You’re going to be big and strong!”

Porcellino beamed while the others crowded around and followed suit, jostling one another aside to show Max their biceps or clamor for him to see the blackberry bushes or the stream where Claudia had caught a trout. When Max fashioned a crude soccer ball from old stuffing and shoe leather, any lingering reservations evaporated. Under Paolo’s precocious leadership, innumerable games and contests were hatched. Kicking games, throwing games, rolling games … Max was amazed at the ingenuity behind each and the enthusiasm that followed. Within days, Max’s ball was destroyed, and Isabella stayed up late one evening to craft another, sturdier version with triple stitching.

The only child who remained quiet and aloof was Mina. This was understandable. Of all the children, she alone had been left in the pen and had seen the monster, had heard it calling to her.

She worked alongside the others but still exhibited many of the dull, mechanical qualities that had marked the children when Max first met them. As the weather warmed, it broke his heart to see her linger indoors while all the rest played outside. Max took to bringing her with him on his chores, particularly those that would entice the little thing to get outdoors and soak up a little sunshine.

And there were endless chores to do. In addition to repairing the main house and storage sheds, there remained the daily business of tending the livestock, preparing the fields for spring planting, gathering firewood, and innumerable other tasks whose difficulty was compounded by few tools of poor quality. During the rebuilding of Rowan, Max had learned a fair bit of carpentry and masonry and now he bemoaned the lack of a good hammer or plane or even nails that were straight and free of rust.

But they managed to make do with what they had, and as the sun set on a beautiful spring day, Max put the door back upon its hinges and applied the last dab of red paint. Isabella and the children gathered round to see this final touch, a cheerful splash of color upon the entrance of a large house whose rooms were swept and scrubbed. Clean water filled the barrels, fresh rushes lined the floor, and a cantankerous old goat was on the menu. Behind the proud assembly, the mountains loomed purple and the clouds drifted past like wisps of pipe smoke.

That night as the children sprawled on their blankets, Max told them a story. While the fire crackled, he paced about the great room, sharing the tale of a little girl who had fallen under an evil spell and forgotten who she was. Determined, she wandered the world to learn her identity. The girl was brave beyond measure and sought out all the forest’s creatures—the frogs and snakes and even the black bear deep in his den. But none could answer her, and so she sailed across the sea and spoke to the fish and the whales and the sleepy turtles that blinked from their hard green shells. But none could answer her questions. Undaunted, she strode off into the hills and climbed the snowy mountains until at last she stood at the highest peak and shivered in the cold. No animals lived at such a fearsome height, and the girl despaired that there was no one left to help her. But just at that moment, she noticed the stars twinkling in the night sky and stretched her hands toward their loveliness.

As Max told his tale, he conjured colorful images of creatures, from a bloated bullfrog to a great whale spouting a spectrum of lights from its blowhole. The children lay spellbound, every mouth agape. By the time the girl stood upon the mountaintop, little stars floated just above their heads, twinkling against the ceiling’s stout rafters.

With her hands outstretched, the girl asked the stars if they could answer her questions. Who was she? What was her name? As she waited in the cold, the stars seemed to come closer, as though they were as curious about this little girl as she was of them. Lower and lower they came until it seemed they were swarming all around her.

The children shrieked with delight as the sparkling lights descended lower like inquisitive pixies, zooming about the room and pausing periodically at each eager face. When they arrived at Mina, however, the lights lingered and began to orbit around her head like a crown.

Because the girl was brave and had climbed such fearsome heights, the stars would help her. The girl was royalty, they said, a beautiful princess who was wise and beloved by her people. They missed her terribly. Could she not guess her name?

At this, Mina’s impassive face gave way to a hesitant smile. “Is her name Mina?” she whispered. “Princess Mina?”

“That’s right,” said Max. “Princess Mina’s people missed her and needed her and have been searching for her all this time. Is she ready to go home?”

Isabella put down her needlework, and the children ceased their squirming. All eyes focused on Mina, who was nestled in the far corner. She glanced up at the stars orbiting her head and then across at Max, who repeated the question.

Was the little princess ready to go home?

Mina nodded, and her crown’s stars burst into tiny lights that zoomed about the room before rocketing up the chimney like a comet’s tail. It was a fitting finale, and the other children clapped and scooted aside to make a place for her in the center. Grinning shyly, Mina gathered up her blankets and joined them.

While Mina laughed and joked with the others, Max settled back into his chair and mused upon the show’s finale. It had been a truly dazzling conclusion to the tale, one that had required an accomplished Mystic’s talent and control. There was only one problem.

The Mystic had not been Max.

He pondered this in silence while the children fell asleep. When the room had been silent for some time, Isabella motioned for Max to follow her upstairs.

“That was a very good thing you did,” she said. “I did not think Mina would smile again. You did not know her, but she had so much life before that terrible night. It makes me happy to see her smile.”

“It’s nothing,” said Max, feeling awkward under Isabella’s close gaze.

“How old are you?” she asked, setting down her lantern.

The simple question stumped him. His birthday was the fifteenth of March, and he imagined it had recently passed without his noticing. By a conventional calendar, Max should have been fifteen, but he had spent many days in the Sidh, where time ebbed and flowed in mysterious ways. He could not be certain.

“Sixteen,” he guessed. “Maybe seventeen? It’s hard to say.”

Isabella nodded at this, then unlatched the shutters to peer out the window at the windy evening.

“Do you still think I’m such an evil person?” she asked.

“I never did,” replied Max. “I thought you made an evil choice.”

“Sometimes every choice is bad,” she said.

Max thought back to past conversations with Ms. Richter and Nigel. They were good people. What sacrifices might Ms. Richter make on behalf of Rowan, or Nigel on behalf of his unborn child? Had Mrs. Bristow already given birth? Max wondered at this and at many things. In his heart, he knew that Isabella was a good person. Max was not a parent; he could not imagine the choices he might have made in her position.

“I’m not angry at you, Isabella,” he said wearily. “There’s no point to it.”

“Thank you,” she murmured. “Before, I did not care so much. But now I do.”

An awkward silence ensued and Max fidgeted. He did not know where this was going or why Isabella needed to have this conversation so far from the sleeping children.

“The goblins will come,” she said hastily. “It has been nearly two months and the moon is right. They will visit tonight or tomorrow.”

“Then I need to get ready,” said Max, relieved. “Where do they usually come from?”

“There,” Isabella said, thrusting her arm out the window. Max’s gaze followed her outstretched finger to the dark road that ran toward the mountains.

“I don’t know,” said Isabella. “Pietro would go out and speak with them. I tried to spy, but I was too frightened to get very close.”

Max nodded and began piecing together his plan.

“What will you do?” Isabella asked cautiously.

“Go out and wait for them,” he said simply.

“Please be careful,” she said, clutching his sleeve. “If they know the monster is dead … I’ve heard terrible stories of the goblins! Th-they’ll make you a prisoner and take you away!”

“Goblins are dumb, Isabella,” said Max, “but they’re not that dumb.…”

As the moon rose higher in the spring night, Max waited in the boughs of a sycamore whose budding branches overhung a bend in the road. There was wind in the valley. It rustled the leaves but not so loudly that Max would be unable to hear the sound of wheels. As he watched the bats skim and dart in search of food, he tried to recall everything he knew about goblins and their ilk.

Goblins in all their forms were miserable creatures—cruel, tyrannical, and bullying whenever they could manage the upper hand. The dryads hated them and would not live in groves near a goblin den. These dens were usually underground or in deep mountains where clans formed a loose confederacy under the absolute rule of a chieftain, who was often chosen by virtue of his size. In many ways, the all-male goblins and all-female hags shared a common culture, and Max wondered if the two species were not distant kindred. Unlike hags, however, there was considerable variety in goblin size and appearance. While some of the smaller hobgoblins might stand a mere three feet, a true goblin chief might look a grown man in the eye and exceed three hundred pounds. With his rope and his sharp sword, Max was prepared for either.

Goblins were active traders and were liable to have considerable news of other creatures—or even demons—that resided in the surrounding area. Based on the farmhouse’s basic supplies and livestock, these goblins were both wealthy and active. They would know of any trade routes and might even have a map to share if Max could be persuasive.

It was very late when he finally heard the clopping of hooves. Blinking the sleep away, he peered into the darkness as a team of mules and a wagon pulled into view, followed by a small herd of sheep. Atop the wagon sat five squatty goblins, the largest snapping the reins and barking at the mules. Their eyes shone through the darkness, tiny pinpricks of light that peered from beneath the wide brims of their oversized hats.

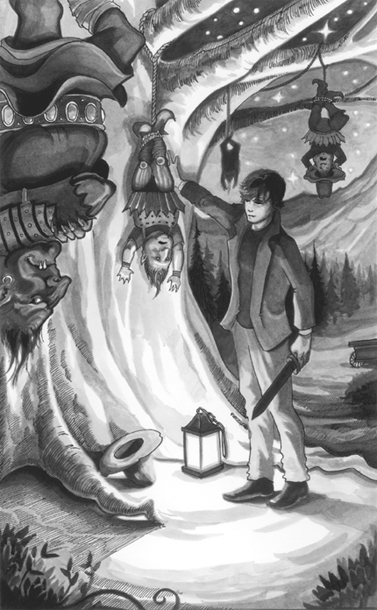

When the cart had nearly reached the sycamore, Max dropped from the branches and stepped into the road.

“Misch-misch!” hissed the driver, pulling hard on the reins. The other goblins sat up to peer at Max, who stood calmly in the road.

“Hrunta, e nugluk a brimboshi? Ilbrya shulka nuv klunkle,” hiccupped the smallest goblin.

His comrades laughed at this, but the driver scowled and leaned over to snatch away the speaker’s flask.

“Where is Pietro?” croaked the driver, removing his hat to scratch his head.

“Pietro is gone,” Max replied. “I’m in charge now.”

“Did you hear that?” exclaimed the goblin, turning to his companions. “He said he’s in charge! Tell us, maggot, what exactly are you in charge of?”

“I’m in charge of this farm,” Max explained. “And that lake and this valley and the mountains beyond. I would rule the sky, too, but that is beyond my reach.”

“He must be a drunk like Pietro,” chuckled the goblin, his eyes glittering. “Enough with this drivel—we are already late. Unload the cart and be gone before we peel your skin for sport!”

“Yes, sir,” said Max, snapping off a salute. Trotting around to the back of the cart, he found three children bound there, along with several crates. Untying their bonds, Max asked if they were able to walk. The eldest—a girl of eleven or twelve—nodded, and Max told her to herd the flock up to the farmhouse and knock on the door. She should call for Isabella and then ask Mario and Claudia for help with the animals. Could she manage that? She could. The younger children, siblings judging by their similar appearance, then helped Max unload the crates before following the girl up the hill.

“That’s the spirit!” laughed the driver, waving his whip at Max. “Put ’em to work before they go down the well!”

Max shrugged. “Actually, they need to carry the things because I need to speak with you. Your delivery’s incomplete.”

“What’s he talking about, Hrunta?” hissed one of the goblins to the driver.

“We brought the usual,” Hrunta grumbled, “and I don’t like your tone.”

“My tone is the very least of your worries.”

At this insolence, Hrunta raised the whip and cracked it down at Max like a thunderbolt. But the goblin was far too slow. Sidestepping the blow, Max caught the whip, wrapping it twice around his hand and promptly wrenching Hrunta from the driver’s seat. The goblin landed with a crumpling thump on the road, his legs kicking in the air like an upturned beetle. His companions merely gaped, stunned.

At Rowan, every student receives a book, a compendium detailing the habits and behaviors of known enemies. Even a First Year knew that goblins hate to be turned upside down—it could induce a panic so severe that they abandoned all resistance. It was the only way to handle them humanely. Quick as a flash, Max tied the whip around Hrunta’s ankle and threw the loose end over a stout sycamore branch. A second later, Max hoisted up the puffing, protesting goblin so that he dangled upside down like an enormous, leather-clad pear.

“Kill him!” barked the outraged goblin, flailing his stubby arms at his fear-stricken comrades.

Max turned as one of the goblins lobbed a dagger. In his haste, however, the young goblin had neglected to remove the sheath, and it thudded weakly against Max’s shoulder.

“What’s your name?” said Max, casually addressing the guilty party, whose spindly arm remained frozen in the act.

“Eh … Skeedle, my lord.”

“Do you think that was wise, Skeedle?”

“No.” The mortified creature blinked. “No, I don’t.”

“Come here,” said Max, beckoning the goblin forward.

“Do I have to?” moaned Skeedle, showing five sharp teeth in a grimace that displayed his revulsion.

“Yes,” said Max, measuring out a length of rope. “I’m afraid so.”

A minute later the juvenile goblin dangled upside down alongside his commander, who cursed and swatted at him in vain. As Max secured the rope’s hitch, he heard the clink-clink-clink of iron-soled shoes as the remaining goblins fled the scene.

Max was acquainted with goblins, having encountered some in Germany the previous year. But those had been wilder, and not so quick to flee at the first sign of real trouble. The present company was of a more genteel variety—similarly cruel but more articulate and uncommonly fat and soft from feasting. Max almost pitied the fleeing trio as he ran them down and bound them to one another in a wriggling bunch that was soon hoisted up into the tree.

“Now,” said Max, pacing before the suspended, sputtering creatures. “I’d hate for this to take any longer than necessary. After all, I’ve seen wolves prowling about the valley.…”

The goblins made a whining noise in their throats and glanced at one another in an escalating panic. Goblins lived in mortal fear of wolves, which were known to hunt them with a savage enthusiasm.

“What do you want?” pleaded Hrunta.

“I’m going to ask questions,” said Max calmly. “And I want the truth. When I ask the question, you’ll all respond together. If one of you fails to answer, he stays up in the tree. If you’re the last to answer, you stay up in the tree. If one of you provides a different answer than the others, he stays up in the tree. See how this works? The answers must be quick and truthful or I will know.…”

The goblins cursed and thrashed about feebly before finally agreeing to Max’s proposal. For the next hour, Max peppered them with questions about their clan, their home, and the valley. He learned that they were of the Broadbrim clan, that their chieftain was the venerable Plümpka, and that the Broadbrims had driven off all the other goblins within the region. The exiled goblin clans—the Sourbogs, Blackbacks, and Greenteeth—had all taken refuge over the mountain. As Max guessed, there were no dryads nearby. But there were lutins, satyrs, and fauns in the southern glades and even a vicious troll in the northern passes where the goblins refused to hunt. The goblins knew of vyes that lived at the base of the mountains, but if an honest-to-goodness demon had claimed title over the region, it had yet to bother with the Broadbrims.

Max turned his questions toward other humans. To his disappointment, the goblins universally denied that there were any free humans living in the vicinity. Max recalled Isabella’s mention of two people named Nix and Valya, but he decided to keep those names to himself.

“No free humans,” Max clarified. “How many humans have the Broadbrims enslaved?”

“None!” protested Skeedle. “They’re already slaves when we get them. The traders bring them from the great city! We just deliver them here according to the contract.”

“Contract with whom?” asked Max.

“We don’t know,” replied Hrunta. “That’s Plümpka’s business.”

“Well, then,” said Max. “Where’s the ‘great city’?”

“South,” they squealed. “A fortnight’s journey south!”

“Is that where you get all your trade goods?”

“No,” they answered, and Max soon learned there were other markets and settlements. According to Skeedle (who was the most forthcoming), there was a trading post two days to the north and a fairly sizable village of various creatures due east over the mountains.

Max listened carefully to these and other details regarding who and what lived in the vicinity. When a wolf howled from down by the lake, the goblins broke into a chattering sweat.

“Now,” said Max, stooping to shine the goblins’ lantern in Hrunta’s eye. “That wolf sounds hungry and I want to wrap this up. Where’s the entrance to the Broadbrim caverns?”

Silence.

“Oh dear,” said Max, pausing to let the goblins hear the answering howls throughout the valley. “I think they know you’re here.… I’ll ask one more time. Where’s the main entrance to your home?”

“Between the red stones of the highest peak!” shrieked Skeedle, despite Hrunta’s glaring admonition. “It’s true! It’s true!”

“And the password?” asked Max. “I know there will be a password to move the guardstones.…”

“We can’t tell you that,” Hrunta insisted. “Plümpka’d eat us whole!”

“He doesn’t have to know.” Max shrugged. “And it’s that or the wolves, so let’s have it on the count of three. One … two …”

“Bitka-lübka-boo!”

The goblins spat the password out in unison just as several pairs of eyes loped into view. The mules snorted and stamped the ground, their flanks shivering as three gray timber wolves set their tongues a-wagging and began to growl.

“Back!” Max yelled, hurling a bolt of bright blue witch-fire that sent the wolves retreating into the dark forest. He turned to the goblins, which were now gibbering and pleading with Max to release them. One by one, Max untied the goblins and lowered them gently to the ground. They rolled to their feet, eyeing the nearby trees for any sign of the wolves.

“Now,” said Max, shepherding them back to their cart. “Just so we understand each other. I know where you live. I know the password. I know your leader’s name and the clans you’ve displaced. If you try to get sneaky or betray me, I can promise you that the Broadbrims will be visited by the Sourbogs, Blackbacks, Greenteeth, and maybe even that troll in the northern passes.…”

“Not the troll!” exclaimed Skeedle. “It’s the wildest thing in the valley!”

“No, Skeedle,” said Max, lifting the little goblin up into the cart. “I am.”