This is a dark age, a bloody age, an age of daemons

and of sorcery. It is an age of battle and death, and of the

world's ending. Amidst all of the fire, flame and fury

it is a time, too, of mighty heroes, of bold deeds

and great courage.

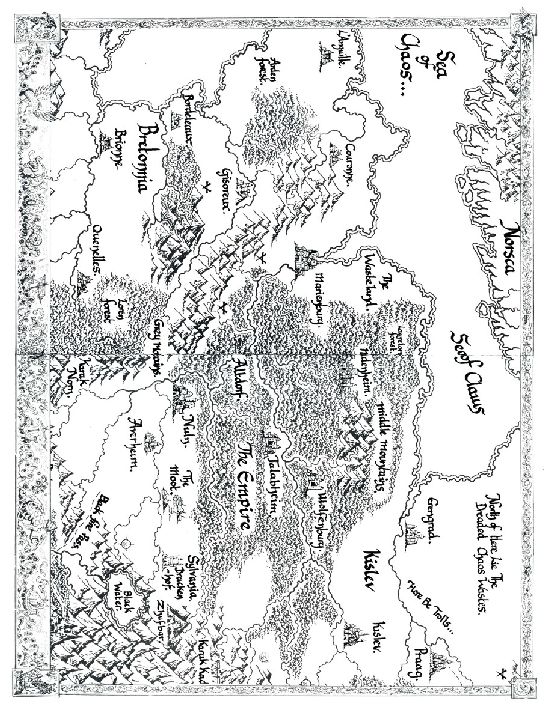

At the heart of the Old World sprawls the Empire, the

largest and most powerful of the human realms. Known for

its engineers, sorcerers, traders and soldiers, it is

a land of great mountains, mighty rivers, dark forests

and vast cities. And from his throne in Altdorf reigns

the Emperor Karl-Franz, sacred descendant of the

founder of these lands, Sigmar, and wielder

of his magical warhammer.

But these are far from civilised times. Across the length

and breadth of the Old World, from the knightly palaces

of Bretonnia to ice-bound Kislev in the far north, come

rumblings of war. In the towering World's Edge Mountains,

the orc tribes are gathering for another assault. Bandits and

renegades harry the wild southern lands of

the Border Princes. There are rumours of rat-things, the

skaven, emerging from the sewers and swamps across the

land. And from the northern wildernesses there is the

ever-present threat of Chaos, of daemons and beastmen

corrupted by the foul powers of the Dark Gods.

As the time of battle draws ever

near, the Empire needs heroes

like never before.

Kar Odacen knew that the lightning bolt he had waited his entire life for would strike the mountain long before it split the sky. A mighty peal of thunder rolled across the heavens, the rain falling in an unending torrent, as though the seas of the world had been carried into the sky by the gods and now flooded forth in an attempt to drown all the lands of men.

He could feel the power of the lightning seething above him, summoned to the land below by the magicks he and every shaman of the Iron Wolves before him had drawn to these mountains since time before memory.

The jagged peak above him was a dark spike against the flickering sky, the gods battling in the clouds casting their ghostly lights across the highlands of the World's Edge Mountains. He felt the hairs on his scarred and becharmed arms stand erect as he passed a column of bleached skulls, fully as tall as the greatest warrior of the Wolves, the tip of the copper pole they were impaled upon protruding a span above the topmost skull. Ripples of blue fire danced along the length of the column of bone, flickering within the empty eye sockets of the grinning skulls, imparting them with a malicious anime. Hundreds of such tribute poles ringed the peak of the mountain, a sign to the Old One who slept beneath the world that he was remembered; that the warriors and shamans of the Iron Wolves had not forgotten him. These mountains were old when the world was young and the Iron Wolves had never dared forget their duty to them.

The High Zars of the Iron Wolves had laid a thousand times a thousand skulls from a hundred lifetimes of war at their shamans' feet and, as the centuries passed, each generation would add more skulls on their copper poles to the mountain. In preparation for his attack into Kislev, the High Zar of the Iron Wolves, Aelfric Cyenwulf himself, had bade his shaman raise countless skulls in honour of the Dark Gods.

Kar Odacen passed one such tribute pole, a sense of fearful anticipation growing within his breast. He had awoken from a dream in which packs of the ravenous, black-furred wolves of the north chased a solitary white wolf across the heavens. Upon the shimmering white wolfs back was a mighty-thewed warrior clad in furs who wielded a great warhammer, and though this wolf was powerful, it could not outpace its hunters. The white wolf turned at bay atop a tall peak of ice-slick rock and together it and the rider fought the snapping packs of northern wolves. Man and wolf fought hard and well, spilling the blood of hundreds of their foes, but even as they took heart in their slaughter, the dark wolves changed to become a roiling storm cloud of impenetrable darkness, pierced only by lava-hot spears of lightning that opened great gashes in the flesh of both man and wolf.

Though he could not see within the cloud, Kar Odacen's dream-self knew that something unimaginably ancient and monstrously evil lay at its heart. And even he, who had sent his spirit into the realm of the daemonkin, knew to dread its power.

Without warning the dark storm suddenly swelled to swallow the man and his wolf whole and Kar Odacen had woken knowing that the night his distant predecessors had prophesied had finally come. He had set off into the darkness, climbing breathlessly for hours as the rain pounded like hammer blows on his shaven, tattooed head and his feet were torn bloody by razor-sharp rocks.

Another boom of thunder, like the gods' footsteps on the world, rolled across the sky, but Kar Odacen did not bother to look up, knowing in his bones that it was not yet time.

He reached a plateau of sheared rock, two hundred yards or more below the peak, his breath like hot smoke in his lungs, and dropped to his knees with arms raised above him in praise of this most holy night. Even over the unceasing roar of the rain he could hear the crackling from the skull columns below him grow louder, feeling the heat of the fire that danced between them as it reached deep into the heart of the mountain.

The skies rumbled and the mountain shook, as though bracing itself for what must happen next and Kar Odacen felt a swelling of dark and terrible power. He looked up as the heavens split apart with a vast, incandescent sheet of lightning that struck the highest peak of the mountain, its brightness searing the sight from his eyes.

The mountaintop exploded, disappearing in a gigantic cloud of rubble and smoke. Rocks were hurled hundreds of yards into the air, tumbling down in an avalanche of blasted shale. Kar Odacen screamed the name of his Dark Gods as the rubble smashed down all around him, pulverising the slopes of the mountain, but, impossibly, leaving him unscathed. Blood dripped from his ears and he blinked the searing afterimage of the lightning from his eyes as he felt the hard rain cease and the deafening echoes of the thunder and explosion fade to nothing, leaving him swaying and alone on the smashed mountaintop.

Kar Odacen lowered his arms, feeling a tremor of dread run through the rock of the mountain. A similar feeling of fear and awe took him in its grip. The sudden silence of the mountains after the violence of the storm was more terrifying than anything he had known before.

A creeping horror slowly overtook him, rising languidly through his bones as the throat of something that had seen the birth of the world took its first breath in uncounted ages. Blinking away tears of rapture and terror, Kar Odacen saw a writhing column of impossibly black, lightning-hearted smoke rise from the smashed caldera of the mountaintop, its sapphire innards crackling with a horrifying, fiery urgency. Though no breath of wind disturbed the night, the smoke gathered itself together, and slid down the mountainside like a dark slick upon the air.

The mountain shuddered with the tread of something magnificent and terrible, rocks crushed to powder beneath its weight and power. The baleful glow from the smoke's innards grew fiercer as it approached the paralysed shaman, the horror concealed there pausing to regard him with as much interest as a man might pay an ant before continuing on its thunderous journey towards the new world below.

Kar Odacen shivered and let out a juddering breath, shaking like a newborn foal.

'The End Times are upon this world...' he whispered through trembling lips.

I

Built atop the Gora Geroyev, the city of Kislev was an impressive sight. High walls of smooth black stone were topped with sawtoothed ramparts and constructed with the practicality common to its northern inhabitants. Tall towers jutted from either side of the thick timber gate and enfilading cannon positions covered the road leading towards the city with their bronze muzzles.

The tops of tall buildings reared above the walls, as if daring an attacker to try and sack them, and the tips of the spears carried by the fur-clad soldiers who walked the ramparts glittered in the low, evening sun. Surrounding the base of the walls were thousands of refugees, people driven from their homes in the north of the country by the warriors of High Zar Aelfric Cyenwulf, a bloodthirsty war leader of the Kurgan tribes.

A sprawling canvas city housing thousands - tens of thousands - gathered around the city, clinging to the walls as though seeking safety by virtue of their proximity.

'Precious little protection to be had here,' whispered Kaspar von Velten, ambassador of the Emperor Karl-Franz, pulling his cloak tighter about himself as a blast of freezing air whipped across the packed hillside. The Tzarina had been forced to bar the gates to prevent further refugees from entering the already overcrowded city. When the High Zar's army came south, as soon it must, the city would quickly starve should the entirety of the fleeing populace be given sanctuary within its walls.

'No.' agreed Kurt Bremen, leader of the group of Knights Panther who rode with Kaspar. 'It will be a slaughter.'

'Perhaps.' said Kaspar. 'Unless Boyarin Kurkosk can stop the Kurgans north of here.'

'Do you think he can?'

'It's possible.' allowed Kaspar. 'I'm told the boyarin is a great warrior and he gathers nearly fifty thousand men to his banner.'

'For these people's sake, let us hope he is a great leader of men as well as a great warrior. The two are not always the same thing.'

Kaspar nodded, guiding his horse along the frozen, rutted roadway between twin rows of makeshift campsites and riding towards the gates of the city. Cold, frightened people glanced up as he and his knights passed, but their misery was too complete for them to pay much attention to them. He felt his heart go out to them, brutalised as they were by months of war and hardship, and wished he could do more to help them.

The gates of the city groaned open as his weary group approached, crowds of desperate people gathering what meagre belongings they had managed to carry from their stanistas and hurrying towards the gates, pleas for entry pouring from every mouth.

Kossars in long, padded coats and green tabards emerged from within and blocked the gateway with long-hafted axes and shouted oaths. Fierce-looking men with helms of bronze and long, drooping moustaches, they pushed the wailing refugees back without mercy and Kaspar had to fight the urge to shout at them. These were their own people they were condemning to the freezing temperatures, but the part of Kaspar that had once been a general in the Emperor's armies knew that they were only obeying orders that he himself would have given were he in charge of the city's defences.

He eased his silver-maned steed, Magnus, through the yelling crowds, turning as a weeping woman pulled at his snow-limned cloak. She wore a threadbare pashmina over a coarse black dress and thrust a swaddled babe towards him, pleading with him in snatches of rapid Kislevite.

Kaspar shook his head, 'Nya Kislevarin, Nya.'

The woman fought off the kossars' attempts to pull her away from Kaspar, screaming and fighting to place the baby in his arms. Even as she was finally dragged away, Kaspar could see that her efforts had been in vain: the child was long-dead, blue and frozen.

Fighting back his sadness, he rode through the cold darkness of the gateway, pathetically grateful to emerge into the cold, miserable confines of the winter-gripped city. The scene inside the walls was little better, the streets lined with gaunt, fur-wrapped people, huddled together and shuffling aimlessly and fearfully along the city streets.

Though he knew his actions in Kislev over the last few months had already saved many lives, having stopped a corrupt Empire merchant from profiteering from stolen supplies destined for the people of Kislev, Kaspar felt fresh resolve to do more.

His personal guard of Knights Panther, mighty armoured knights atop enormous Averland destriers, were weary after nearly two weeks spent out in the frozen wilderness of Kislev. They followed him inside, all visibly struggling with the idea of leaving these people outside the walls.

In the centre of the Knights Panther rode Sasha Kajetan, once the most beloved and heroic figure in Kislev, a swordsman beyond compare and leader of one of the Tzarina's most glorious cavalry regiments. Kajetan was now a broken man, virtually catatonic and skeletally thin after his flight into the oblast.

Kajetan's hands were bound before him, his true nature as a brutal murderer having only recently come to light when he had killed Kaspar's oldest friend, before abducting and torturing his physician.

But Kajetan was now captured and though the feared Chekist would surely want him hung, Kaspar was determined to delay the swordsman's fate for as long as possible to try and fathom what had driven the man to such murderous extremes.

Kajetan caught Kaspar's look and nodded weakly in acknowledgement. Kaspar was surprised; it was the first human gesture the swordsman had made since they had fought their way through the Kurgan scouting party in the oblast nearly a week ago.

Kaspar watched as the gates closed, pushed shut by nearly a score of kossars and barred with thick spars of hardened timber.

'Sigmar forgive us...' he whispered, turning his horse and riding along the Goromadny Prospekt towards Geroyev Square in the centre of the city.

During the summer and spring months, the square was traditionally the site of a thriving market, thronged with trappers selling their wares, horse traders and all manner of merchants. When Kaspar had first come to Kislev, enthusiastic crowds had gathered, yelling and cursing around a corral of plains ponies, the bidding spirited and lively, but now the square was packed to capacity with innumerable campsites, clusters of tents and sputtering cookfires covering every inch of ground.

It was a sight typical around Kislev, a city in which there were many wide boulevards lined with hardy evergreens - most of which had long since been cut down for firewood. The hulking iron statues of long-dead tzars watched over their people's misery impassively, powerless to aid them in their time of need.

The Winter Palace of the Ice Queen dominated the far side of the square, its white towers and gleaming marble walls of ice glittering like glass in the low evening sunlight.

'The Ice Queen left the gates open too long,' observed Kurt Bremen. 'There are too many people within the walls. Many of them will starve to death when Kislev comes under siege.'

'I know, Kurt, but these are her people, she could not leave them all to die. She would save her city, but lose her people,' replied Kaspar, riding along the edge of the square towards the Temple of Ulric and the Empire embassy that lay behind it.

'Unless there is some better news from the Empire, she may lose it anyway. With Wolfenburg gone, it is doubtful the Emperor will send his armies north when there are enemies within our own lands.'

'They will come, Kurt.' promised Kaspar.

'I hope you are right, ambassador.'

'Have you ever met the Emperor?' asked Kaspar, turning in the saddle to face the knight.

'No, I have not had that honour.'

'I have, and Karl-Franz is a man of courage and honour.' said Kaspar. 'He is a warrior king and I have fought alongside him on more than one occasion. Against orcs, Norse raiders and the beasts of the forests. He has sworn to aid Kislev and I do not believe he will forsake that oath.'

Kurt Bremen smiled. 'Then I too will believe it.'

Both ratcatchers were so inured to the reek of shit that neither now paid it any mind. Hundreds of tonnes of human and animal waste flowed through the sewers below the streets of Kislev, carried through the oval tunnels dug through the rock and earth of the Gora Geroyev to empty far downriver into the Urskoy.

Commissioned by Tzar Alexis and designed by the ingenious Empire engineer, Josef Bazalgette, the tunnels below Kislev were amongst the greatest engineering marvels of the north, effectively eliminating the scourge of cholera from the Kislevite capital. Mile upon mile of twisting tunnels extended in a labyrinthine maze beneath the streets like the tunnels beneath the Fauschlag of Middenheim; though these tunnels were formed of bricks and mortar rather than from the natural rock.

A pair of small dogs padded before the two ratcatchers along the ledge that ran alongside the foaming river of effluent, their tails erect and ears pressed flat against their skulls. The rushing of the sewage echoed from the glistening brick walls, keeping conversation to a minimum.

Both men were clad in stiffened leathers, crusted with age and filth, and high, hobnailed boots. They wore thin metal helmets, padded with matted fur and scarves around their mouths and noses. Though they barely noticed the smell any more, they wore the protective scarves through force of habit. Each man carried a long pole over one shoulder, a single rat dangling by its tail from each of them.

'A poor day, Nikolai, a poor day.' said the shorter of the two ratcatchers with a weary shrug that made the rat on his pole dance in an imitation of life.

'Aye, Marska, few vermin to catch today.' agreed his apprentice, Nikolai, casting an irritated glance at the two dogs. 'What shall we eat tonight?'

'I think we shan't be presenting these sorry specimens to the city authorities for a copper kopek.' sighed Marska. 'I fear we may be dining on rat again, my friend.'

'Perhaps tomorrow will be better. We could sell some to the refugees?'

'Aye, maybe we can.' said Nikolai doubtfully.

Winter's icy grip and the bloodthirsty ravages of a Kurgan barbarian war leader, whose armies were even now closing on the city, had displaced thousands of people from their homes on the steppe and many now huddled, cold and frightened, around the walls of the northern capital. It was true that the refugees who flocked to the camps outside the city walls were willing to eat pretty much anything and there had been some nice money in selling rat meat to them. But that had been before the cold had killed most of the rats and the few emaciated creatures they had managed to trap were the only food that they themselves could expect to see for some time.

The two men trudged on in silence for some time until Nikolai nudged Marska as he saw the two dogs suddenly stiffen and draw their jowls back over sharp teeth. Neither dog made a sound, their vocal chords having long since been cut, but their bowstring-taut posture told both ratcatchers that they had sensed something they didn't like. Ahead, Marska knew the passage widened into a high-domed chamber where a number of divergent effluent tunnels converged before heading out to the Urskoy.

Marska unhooked a small hand crossbow from his belt and eased back the string, wincing when the mechanism clicked as it caught. But to keep the weapon cocked would lose the tension in the string and reduce the power in the bolt. The weapon was an indulgence; most ratcatchers could only ever afford a sling and pebbles for shot, but one glorious summer, Marska had discovered a body floating in the sewers with a purse bulging with gold coins. He had hidden the coins about his person for many months before daring to spend them. Nikolai slipped a rounded pebble into his sling and eased himself past the two dogs, his footsteps silent for such a big man.

Ahead, Marska could hear voices, muffled and obscured, but years of working below the streets of Kislev had given him a good ear for picking out sounds that wouldn't normally be expected here.

Nikolai turned and gestured quizzically along the length of the tunnel to a sprawling pile of debris, bricks and mud that lay on the ledge that ran alongside the effluent. The rubble looked for all the world as though it had been pushed from the wall and Marska wondered who in their right mind would want to tunnel into a sewer. The dogs padded along silently, stopping as they reached the tumble of debris, dipping their heads to sniff at something on the ledge.

Marska ghosted forwards and crouched beside the mud that had spilled from the hole in the wall. Tracks, but tracks that didn't make any sense. They were smudged and deep, as though whoever or whatever had made them had been carrying something heavy, but that wasn't the first thing Marska noticed that was odd. It was hard to be sure, but the prints looked as though they only had four toes on each foot, and from the conical depression a little beyond each toe, it appeared as though they were clawed...

It was obvious that whatever had made the tracks walked on two legs, but what manner of man had only four toes and claws? An altered perhaps, or one of the beasts of the dark forests come down from the north? Marska felt a flutter of fear race up his spine at the thought of one of these hideous creatures loose down in his sewers. As a child, he had seen such a beast when a band of Ungol horsemen had ridden through his stanista with the corpse of one of these monstrous, horned creatures and Marska remembered the terror he had felt at the size of the beast.

The voices came again, thrown from far away by the curve of the tunnel. Only fragments of conversation echoed back towards the ratcatchers, but Marska knew that they must be talking about something important. After all, people did not meet in the sewers to discuss the latest harvest or the weather.

As a member of the Guild of Ratcatchers, Marska was also part of the network of informers who worked for Vassily Chekatilo, the ruthless killer who controlled everything illegal in Kislev, a dangerous man who traded in stolen goods, narcotics and flesh. Part of his power came from knowing things that he should not know and the ratcatchers were an important part of that, for who paid any attention to the filthy peasant covered in shit who cleared your house of vermin?

Taking great care to tread silently, the two ratcatchers crept forward, at last reaching the edge of the fallen pile of brickwork. Now that they were closer, Marska could see that the hole in the wall disappeared into the darkness for some way.

Moving slowly so as not to draw the eye of any observers, Marska and Nikolai eased their heads above the level of the rubble.

The domed chamber echoed with the lapping sewage, ripples of reflected light dancing on the vaulted ceiling. A circular ledge, some six feet wide, ran around the circumference of the chamber and eight, half submerged pipes disgorged their filthy cargo into the central reservoir that drained downriver. On the far side of the chamber stood four figures beside a ramshackle cart, like that used by the collectors of the dead. An apt choice of conveyance, thought Marska, seeing a bronze coffin sealed with a number of rusted padlocks atop the cart. Two figures dressed in rippling robes that appeared to change colour stood closer to the wall of the chamber, while another pair stood beside the cart.

These last two figures were smaller than the others, hunched over, and even over the reek of the sewers the stench emanating from the nearest was overpowering. Dressed in excrement-smeared rags and bound around the arms and chest with weeping bandages, it was bent almost double by a collection of thick, brass edged books tied to its back. A cracked bell hung from a rope belt around its waist and its face was, thankfully, obscured by its patchwork hood. Its companion was hidden in the shadow; so well that Marska had very nearly missed him. Swathed from head to foot in black robes the figure clutched what appeared to be a long-barrelled musket of some kind, though it was festooned with brass fittings, coils and pipes whose purpose escaped Marska.

The tallest of the figures in the multi-coloured robes took a hesitant step forward, holding a metal box, some six inches square. The filth-smeared figure beside the bronze coffin raised its head, as though scenting the air, its head darting quickly from side to side. Marska watched as the lid of the box was opened and a soft, pulsating emerald-green light radiated from inside it, bathing the chamber in a fearful, sickly glow.

'Your payment.' said the figure holding the box, its voice smoky and seductive.

The filthy hunchback snatched the box with a squeal of pleasure, almost quicker than the eye could follow, and stared deep into the glowing depths, as though inhaling the scent of whatever lay within.

'And this is what you bring me?' asked the former owner of the box, reaching out a delicate hand to touch the coffin.

A blur of motion, black on black, and a clawed hand snatched out and grabbed the hand reaching for the coffin. Marska was amazed; without seeming to move, the black robed figure with the musket had darted from the shadows to intercept the hand reaching for the coffin. No man could move that fast; it was inhuman.

The filthy book-carrier shook its head slowly and the hand was withdrawn.

Marska turned and cupped his hands around Nikolai's ear, whispering, 'Nikolai, get back to the surface. Chekatilo will want to hear of what's happening down here.'

'What about you?' hissed Nikolai.

'I want to see if I can hear anything else, now go!'

Nikolai nodded, and Marska could see that his young apprentice was glad to be leaving. He didn't blame him, but he had to stay. If Chekatilo found out - and he would - that he had seen these events and not learned all he could, he might as well slit his throat now.

As Nikolai slipped away, Marska turned his attention back to the drama unfolding before him in time to hear the rotten, bandaged figure reply to an unheard question, hissing a single word that sounded as though it came from a mouth never meant to speak the tongues of men.

'Eshhhiiiiin...' it said, bobbing its head, pointing to the figure dressed in black. As it did so, Marska saw what looked like a long, fat worm waving in the air behind it. His lip curled in distaste before he realised that he was not looking at some serpent as people were often wont to claim dwelled in the sewers, but a tail. A pink tail, hairless save for a few mange-ridden patches of coarse, wiry fur.

Revolted, he drew in a sharp breath, and in that moment knew he had doomed himself as the figure in black's head snapped in his direction.

'No...' he hissed, pushing himself to his feet to sprint away. He had barely risen when a flurry of silver flashed through the air and struck him in his chest. He grunted in pain, turning to run, but his legs wouldn't obey him, and the ground rushed up to slam into his face as his limbs spasmed violently. Marska rolled onto his back, seeing a trio of jagged discs of metal with dripping blades protruding from his chest. Where had they come from, he wondered, as he felt his muscles jerk and his lungs fill with froth?

He tried to move, but was helpless, dying.

With the last ounce of his strength he yelled, 'Run, Nikolai, run! They're coming!' as a dark shadow enveloped him, darker even than that pressing in on his eyes.

Marska looked into the face of his killer and realised that Death had a sense of irony after all.

The Goromadny Prospekt was busy despite the late hour. People with no homes to call their own wandered the streets, rightly fearing that to lie down in the cold snow would be to die. Snow drifted up the sides of buildings, the central thoroughfare of the city trodden to brown slush. Those few taverns with any wares left to sell burned what fuel they had to keep the worst of the cold at bay, but it was a futile gesture against the aching, marrow-deep cold of Kislev.

Families huddled together for shared warmth in doorways, fur blankets pulled tight around them, yet still shivering in cold and fear.

Harsh times had come to Kislev, but worse was yet to come.

The scrape of metal on stone was the first hint that something out of the ordinary was happening, but most folk ignored it, too cold and hungry to pay any mind to matters beyond their concern.

A rusted iron manhole slid through the snow, grating on the cobbles, bloodied hands reaching up from below the street. A man, covered in muck and screaming in terror hauled himself from the sewers, jerking like a marionette as he rolled in the slush.

Something fell from his dirty clothing, a short-bladed dagger with a curved blade; a blade that had caught in the folds of his leather tabard and nicked the surface of his skin.

The man thrashed upon the ground, desperately trying to put as much distance between himself and the entrance to the sewers. His back arched as he convulsed and his screams of agony moved even the hardest hearts to pity.

As curious onlookers cautiously approached, the man screamed, 'The rats! The rats! They're here, they've come to kill us all!'

People shook their heads in weary understanding, now seeing the man's ratcatching apparel, guessing that he had simply spent too long below ground and thus fallen prey to lunacy. It was sad, but it happened, and there was nothing they could do. They had troubles of their own.

As the onlookers dispersed, no one noticed the venomous yellow eyes that stared out from the blackness below, or the clawed hand that reached up to slide the manhole back in place.

If Kaspar had been grateful to see the spires of Kislev as they rode from the oblast, it was nothing compared to his relief at returning to the Imperial embassy. Snow clung to its walls and long daggers of ice drooped from the high eaves, but a warm homely glow spilled into the night from the shuttered windows and smoke spiralled lazily from the chimneys. He and his knights rode up to the iron, spike-topped gates, blue and red liveried guards eagerly opening them and welcoming their fellow countrymen back.

A tutting farrier took the bridle of Kaspar's horse and he dismounted, wincing as the stiffness of two weeks in the saddle pulled at his aged muscles. The wound he had received from the leader of a Kurgan scouting party pulled tight, the stitches Valdhaas had pierced his flesh with still raw beneath a fresh bandage.

The door to the embassy opened and Kaspar smiled as Sofia Valencik strode along the path towards him, a heartfelt smile of relief creasing her handsome features. The physician's long, auburn hair was pulled in a tight ponytail and she wore a green dress with a red, woollen pashmina wrapped around her shoulders.

'Kaspar.' she said, throwing her arms around him, 'it's so good to see you.'

'And you, Sofia.' replied Kaspar, returning the embrace and holding her tight. He was pleased Sofia was on her feet again; the last time he had seen her, she had been confined to bed, recovering from her brutal kidnapping by Sasha Kajetan. Her left hand was still bound with bandages where he had severed her thumb.

Thinking of the captured swordsman, Kaspar opened his mouth to speak.

'Sofia-' he began, but she had already seen her former captor being pulled from the saddle by one of the Knights Panther. He felt her go rigid in his arms.

'We were able to capture him, Sofia, as you wanted,' said Kaspar softly. 'I've sent word to Pashenko that we'll bring him to the Chekist building tomorrow and-'

But Sofia appeared not to be listening, pulling free of Kaspar's arms and marching stiffly towards Sasha. Kaspar made to follow her, but Kurt Bremen gripped his arm and shook his head slowly.

Sofia hugged her arms tightly about herself as she neared Kajetan, the swordsman's emaciated frame held aloft by two knights. Kaspar could see how much courage it took her to face her abuser and felt his admiration for Sofia soar once more. Hearing her steps, Kajetan turned and Kaspar saw the swordsman shudder in... what? Fear, guilt, pity?

Kajetan met the woman's eyes for as long as he could before dropping his head, unable to endure the cold heat of her accusing gaze any longer.

'Sasha,' she said softly, 'look at me.'

'I can't...' whispered Kajetan. 'Not after what I did to you.'

'Look at me,' said Sofia again, this time with steel in her voice.

Slowly Sasha's head rose until once again their eyes met. Tears streamed down Kajetan's cheeks and his eyes were violet pools of sorrow.

'I'm sorry,' he choked.

'I know you are,' nodded Sofia. And slapped him hard across the face.

Kajetan didn't flinch, the red imprint of her hand bright and vivid against the ashen pallor of his face. He nodded and said, 'Thank you.'

Sofia said nothing, wrapping her arms around herself once more as the knights led Kajetan to the cell beneath the embassy. Kaspar moved to stand behind Sofia as the Knights Panther attended to their mounts and the embassy guards closed the gates once more.

'Why did you bring him here?' asked Sofia without turning.

'I wasn't about to hand Sasha over to Pashenko before getting some assurances that he wouldn't hang him the minute my back was turned,' explained Kaspar.

Sofia nodded and turned to face him once more. 'I am glad you are home safely, Kaspar, I really am, and I'm happy that you managed to bring Sasha back alive. It was just a shock to see him there like that.'

'I understand, and I'm sorry. I should have sent word ahead.'

'It brought it all back, the terrible things he did to me. I almost couldn't move, but...'

'But?' asked Kasper when Sofia's words trailed off.

'But when I saw what had become of him, I knew that I wasn't about to let what he'd done beat me. I'm stronger than that and I had to show him that, even if it was just for my own sake.'

'You are stronger than you know, Sofia,' said Kaspar.

Sofia smiled at the compliment and linked her arm with Kaspar's, turning him around and walking back to the embassy with him.

'Come on, let's get you into a hot bath, you must be frozen to the marrow,' said Sofia playfully. 'I don't know, a man of your age gallivanting outside in the middle of winter like you're some kind of young buck.'

'You're starting to sound like Pavel,' chuckled Kaspar, his grin fading as he saw Sofia's face darken at the mention of his old comrade in arms.

'What's the matter?'

Sofia shook her head as they entered the embassy and shut the door behind them. Kaspar immediately felt the warmth of the building envelop him as one of the embassy guards helped him off with his frosted cloak and muddy boots.

'It is not my place to say,' said Sofia archly.

'But I can see you're going to anyway.'

'Your friend is nekulturny,' she said. 'He spends all his time drinking cheap kvas, and falling into the blackest of moods. He hasn't been sober since you left to go after Sasha.'

'He's that bad?'

'I don't know what he was like before, but he seems intent on drinking himself into the Temple of Morr as soon as he can.'

'Damn it,' swore Kaspar. 'I knew something was wrong before I left.'

'I don't know what's the matter,' confessed Sofia, 'but whatever it is, he needs to sort it out soon. I don't want to have to stitch a shroud for him.'

'Don't worry,' growled Kaspar. 'I'll get to the bottom of it, that's for damn sure.'

V

Vassily Chekatilo threw a handful of thin branches onto the crackling fireplace and took a drink of kvas from a half-drained bottle, enjoying the comfortable warmth filling his chambers at the rear of the brothel. His establishment was busy tonight - as it had been for the last few months since the refugees had begun streaming south - and several whores sprawled on chaise-longues in various states of undress and narcotic oblivion, waiting to be called back to the main chambers.

Most of them had once been pretty. Chekatilo only employed pretty ones, but they were now shadows of their former selves, the rigours of their profession and the escape of weirdroot soon robbing them of whatever beauty they might have possessed. Once, he had thought that having such nubile creatures around his chamber gave it an air of exotica, but now they merely depressed him.

Though sumptuously furnished with many fittings and furniture he had extorted from the previous ambassador from the Empire, Andreas Teugenheim, his chambers were nevertheless assembled with the taste of a peasant. His criminal enterprises had garnered him great wealth and many fine things, but there was no escaping his humble origins.

'A piece of shit in a palace is still a piece of shit.' he said with a smile, watching a pair of black-furred rats gnaw on something unidentifiable in the corner of the room.

'Something funny?' asked Rejak, his flint-eyed assassin and bodyguard, who had entered the room without knocking.

'No,' said Chekatilo, masking his annoyance by turning and drinking some more kvas. He offered the bottle to Rejak, but the assassin shook his head, circling the room and unashamedly ogling the naked women sprawled around the room. As he reached the chamber's corner, his sword flashed from its scabbard and stabbed downwards. A pair of squeals told Chekatilo that the two feasting rats were dead. Trust Rejak to find something to kill.

'Did you see the size of those creatures?' asked Rejak. 'I swear the damn things are getting bigger every day.'

'Wars are always good for vermin,' said Chekatilo.

'Aye,' agreed Rejak. 'And ratcatchers, well, except for the poor bastard they pulled from below the Goromadny Prospekt today.'

'What are you talking about?'

'Oh, just something that happened earlier tonight. One of the guild ratcatchers who sometimes feeds me information was hauled off to the Lubjanko screaming that the rats were coming to kill us all. They say he climbed from the sewers like all the daemons of Chaos were after him and started acting like a lunatic. I think he hit some people before the watch came and dragged him away.'

Chekatilo nodded, filing the information away as Rejak wiped his sword on a dark rag before sheathing it and slumping into a chair before the fire. Chekatilo sat opposite his assassin and stared into the fireplace, enjoying the simple act of watching the flames dance and listening to them devour the new wood in the grate. He sipped the kvas, waiting for Rejak to speak.

'Damn, but it's cold out there,' said Rejak, shifting his sword belt and holding his hands out to the fire.

Chekatilo bit back a retort and said, 'What news from the north? What are people saying?'

Rejak shrugged. 'The same as they've been saying for weeks now.'

'Which is?' said Chekatilo darkly. Finally catching his master's mood, Rejak said, 'More people are coming south every day. They say that the armies of the High Zar are getting bigger with every passing week, that each of the northern tribes he defeats he swears to his banner. And that his warriors leave nothing alive behind them.'

Chekatilo nodded. 'I feared as much.'

'What?' said Rejak. 'That the Kurgans are coming south? They've done that before and they'll do it again. Some peasants will get killed and once the fighting season is done, the tribes will return to the north with fat bellies, slaves and some plunder.'

'Not this time, Rejak,' said Chekatilo. 'I can feel it in my bones, and I've not lived this long without trusting them. This time it will be different.'

'What makes you say that?'

'Can't you feel it?' asked Chekatilo. 'I can see it in every desperate face that comes here. They know it too. No, Rejak, the High Zar and his warriors do not come for the plunder or rape, they come for destruction. They mean to wipe us from the face of the world.'

'Sounds like the kind of talk I hear in the gutter grog shops.' said Rejak. 'Old men telling anyone who'll listen that these are the End Times, that the world is a more wicked place than when they were younglings and that there is no strength here any more.'

'Perhaps they are right, Rejak, did you ever think of that?'

'No.' confessed Rejak, placing his hand over his sword's pommel. 'There is still strength in me and no bastard is going to kill me without a fight.'

Chekatilo laughed. 'Ah, the arrogance of youth. Well, perhaps you are right and I am wrong. It is a moot point now anyway.'

'You are still set upon leaving Kislev then?'

'Aye.' nodded Chekatilo, looking around his drab chamber, his eyes fastening upon another mangy rodent feasting upon the bodies of the dead rats in the corner. Rejak was right; these damned rodents were getting bigger.

He put the rats from his mind and said, 'This place will be no more soon, of that I am sure, and I have no desire to end my days spitted on a Kurgan blade. Besides, Kislev bores me now and I feel the need for a change of scenery.'

'Did you have anywhere in particular in mind?'

'I thought Marienburg would be an ideal destination for a man of my talents.'

'A long journey,' pointed out Rejak. 'Dangerous too. A man travelling with wealth would find it hard to reach his destination intact without protection.'

'Yes,' agreed Chekatilo, 'a hundred soldiers or more.'

'So where are you going to get a hundred soldiers? It's not as though the Tzarina is going to let you have a regiment of kossars or her precious Gryphon Legion.'

'I thought I might ask Ambassador von Velten.'

Rejak laughed. 'And you think he'll help you? He hates you.'

Chekatilo smiled, but there was no warmth to it. 'If he knows what's good for him, he will. Thanks to Pavel Korovic, the ambassador owes me a favour, and I am not a man to allow a debt like that to go unanswered.'

I

Despite the biting chill of the morning and the stiffness in his muscles from two weeks in the saddle and sleeping on the cold ground, Kaspar's spirits were high as he rode through the busy streets of the city. Last night he had enjoyed a long, hot bath to wash off the grime of his adventures in the desolate wilderness of the Kislev oblast, before retiring to bed and falling asleep almost before his head hit the pillow.

Awaking much refreshed, he had dressed and sent word to Anastasia that he would call upon her for an early breakfast. He looked forward to seeing her again, not least because it had been many years since he had been sharing his bed with an attractive woman, but also because she was a tonic for his soul. He found her playfulness and unpredictability fascinating; keeping him forever guessing as to her true thoughts. She was at once familiar and a mystery to him.

He wore his freshly cleaned and dried fur cloak over a long black frock coat with silver thread woven into the wide lapels, and a plain cotton undershirt. A tricorned hat with a silver eagle pinned to it sat atop his head, its design old fashioned, but pleasing to him. Four Knights Panther rode alongside him, clearing a path for the ambassador with their wide-chested steeds.

Word had spread to the people of the city that Kaspar had been instrumental in the apprehension of the Butcherman, and there was much doffing of hats and tugging of forelocks as he passed.

The streets widened as his journey took him into the wealthier parts of the city in the north-eastern quarter, though even here, there was no escaping the depredations of war. Families and scattered groups of Kislevite peasants huddled close to the walls, utilising their meagre possessions to fashion rough leantos and shelters from the worst of the cold winds that whistled through the city. He rode past cold and hungry groups of refugees towards the Magnustrasse and Anastasias house, turning into the wide, cobbled boulevard to find it similarly inhabited.

The stand of poplars opposite Anastasias house was gone, hacked stumps all that remained of them, and as Kaspar rode through the open gateway in the dressed ashlar walls of her home, he saw several hundred people camped within. Anastasia's home was tastefully constructed of a deep red stone, situated at the end of a long paved avenue that was lined with evergreen bushes - though Kaspar noticed that many of these were afflicted with a sickly discolouration of their greenery. Perhaps the cold was too severe even for these normally hardy plants, though the low temperatures did not seem to bother the darting rats that scurried through the undergrowth.

Dressed in a white cloak edged with snow leopard fur and with her long, jet-black hair spilling around her shoulders, Anastasia Vilkova was an unmistakable sight. Kaspar watched as she distributed blankets to those most in need.

She looked up at the sound of horses' hooves and as he drew nearer, Kaspar saw her face flicker before breaking into a smile of welcome.

'Kaspar, you're back,' she said.

'Aye,' nodded Kaspar. 'I promised you I'd come back safely, didn't I?'

'That you did,' agreed Anastasia.

He swung his leg over the saddle and dismounted, saying, 'Though two weeks in the oblast is more than enough for any man.'

Anastasia, still carrying an armful of blankets leaned up to kiss him as he handed Magnus's reins to a green-liveried stable boy.

He returned her kiss fiercely, revelling in the softness of her lips against his own until she pulled back with a wicked sparkle in her eyes.

'You have missed me, haven't you?' she laughed, turning away and handing out the last of the blankets to the people camped within her walls.

'You wouldn't believe how much,' nodded Kaspar, walking alongside Anastasia as they made their way towards her home. You seem to have a great many guests just now.'

'Yes,I have space within the grounds here, and it seemed to make sense to allow these poor people to make use of it.'

'Always trying to help others,' said Kaspar, impressed.

'Where I can.'

'Regrettably, people like you are rare.'

'I remember saying something similar to you once.'

Kaspar laughed, 'Yes, I remember, the first time I called upon you. Perhaps we are two of a kind then?'

Anastasia nodded, her jade eyes flashing with secret mirth, and said. 'I think you might be more right than you know, Kaspar.'

They reached the black, lacquered door to Anastasia's home and she pushed it open, saying, 'Come inside, it's cold out here, and I want to hear all about your adventures in the north. Was it hard? How silly of me, I suppose it must have been. To catch and kill a monster like Kajetan can't have been easy.'

Kaspar shook his head. 'It was hard, yes, but I didn't kill him.'

'Of course not, I suppose it was one of those brave knights who killed him.'

'No, I mean Sasha is not dead, we were able to take him alive.'

'What?' said Anastasia, her jaw dropping open and her skin turning the colour of a winter sky. 'Sasha Kajetan is still alive?'

'Yes,' said Kaspar, surprised at the sudden chill in Anastasia's tone. 'He's in a cell below the embassy and once our meal is over I shall be taking him to Vladimir Pashenko of the Chekist.'

'You didn't kill him? Kaspar, you promised! You promised you'd keep me safe!'

'I know, and I will,' said Kaspar, confused at the passion of her reaction. 'Sasha Kajetan is a shell of the man he once was, Ana, he won't be hurting anyone. I promised you I wouldn't let anyone hurt you again and I meant that.'

'Kaspar, you promised,' snapped Anastasia, her eyes filling with tears. 'You said you would kill him.'

'No,' said Kaspar firmly. 'I did not. I never said I would kill him. I wouldn't say such a thing.'

'You did, I swear you did,' cried Anastasia. 'I know you did. Oh, Kaspar, how could you fail me?'

'I don't understand,' said Kaspar reaching out to put his arms around her.

Anastasia took a step backwards, folding her arms and said, 'Kaspar, I think you should go, I don't think I can talk to you just now.'

Kaspar started to say that he would still keep her safe, but his words trailed off when he saw the frosty hostility in Anastasia's eyes and felt a flash of anger. What did she want of him? Had he not ridden into the depths of the harshest country imaginable for this woman?

'Very well,' he said, rather more sharply than he had intended. 'I will bid you good day then. Should you wish to see me, you know where to find me.'

Anastasia nodded and Kaspar turned on his heel, snapping his fingers at the stable boy to bring his horse. He would hand Kajetan over to the Chekist and that would be the end of the matter.

His breath misted before him, the thin blanket his gaolers had given him doing little to prevent the cold of the cell penetrating him to the marrow. Sasha Kajetan sat on the thin mattress that, save for the night-soil bucket, was the only furnishing within the small cell beneath the embassy. He shivered, the pain of his many wounds dulled by the numbing cold.

His upper body was crisscrossed by freshly stitched scars - wounds taken in battle with Kurgan tribesmen - though his greatest wound was to his thigh, where the ambassador had driven his sword after denying him the death he knew he deserved.

Sasha wished that Ambassador von Velten had killed him. The woman who had slapped him - the woman he had once believed was his beloved matka - had promised him that the ambassador would help him, but she had lied. The ambassador had not helped him to die, but had spared him, prolonging the agony of his existence and he wept bitter tears of frustration, knowing that he was too weak to end his life himself and hearing the mocking laughter of the trueself as a hollow echo in the depths of his mind.

The trueself was still there, lurking like a sickness, though instead of swallowing him whole as it had done for so long, it gnawed and worried at the frayed ends of his sanity. He held his shaking hands out before him, the blackened tips of his fingers raw where exhuming his mothers corpse from the frozen ground and frostbite had claimed them.

There was nothing he could do to atone for what he had done, though he had hoped that the ambassadors blade would grant him the absolution he craved. He knew that the Chekist would hang him for his crimes and, while he welcomed the oblivion the hangman's rope promised, he was tormented by the suspicion that death would not be enough of a punishment. Why the ambassador had not killed him, he did not know. Surely someone he had wronged so terribly should have cut him down like the animal he was?

But he had not and Sasha was consumed with the need to know why.

With a clarity borne of the acceptance of death, Sasha understood that his and the ambassadors fates were still intertwined, that there were dramas yet to unfold between them.

Von Velten had not killed him and as he felt the trueself continue to erode his reason, Sasha Kajetan just hoped that the ambassador did not live to regret that clemency.

Pavel Korovic opened his eyes and let out a huge belch, his mouth gummed with dried saliva. Bright spears of light streamed through the high window, stabbing through his eyes, and he groaned as the hammer blows of a crushing headache began to build.

'By Tor, my head...' he mumbled, rubbing the heel of his hand against his forehead. Gingerly, he rose from his bed, grimacing as the headache worsened and he felt his stomach lurch in sympathy.

Pavel smelled the stench of himself, stale sweat and cheap kvas, and saw that he had fallen asleep in his clothes again. He didn't know when he had last bathed and felt the familiar sense of shame and self-loathing wash over him as his memories swam to the surface of his mind through the haze of alcoholic fog. He needed to eat something, though he doubted if he could keep anything down.

He swung his legs from the bed, knocking over a trio of empty bottles of kvas, which shattered on the stone floor. The fire in the grate had long since burned to ash and the cold knifed through his clothing as he pushed himself upright, careful to avoid the pile of broken glass.

Where had he gone last night? He couldn't remember. Some darkened, backstreet drinking den no doubt, where he could lose himself once more in the oblivion of kvas.

The guilt was easier to deal with that way; the guilt of what Vassily Chekatilo had forced him to do - many years ago and recently - did not eat away at him when he could barely remember his own name.

Though it had been six years ago, Pavel could still remember the murder he had committed for Chekatilo. He could still hear the sickening crack as he had brought the iron bar down on Anastasia Vilkova's husband's skull; see the brains that had spilled onto the cobbles and smell the blood that gathered like a red lake around his head.

The killing had shamed him then, and it shamed him still.

But to Pavel, the worst betrayal had been at his own accord when he had knowingly placed Kaspar, his oldest and truest friend, in debt to Chekatilo. He told himself it was to help the ambassador find Sasha Kajetan, but that was only partly true...

By trying to erase one mistake, he had made a greater one and now it wasn't just him who would pay for it.

How could he have let himself sink so low?

The answer came easily enough. He was weak; he lacked the moral fibre that made men such as Kaspar and Bremen such honourable figures. Pavel put his head in his hands, wishing he could undo the pathetic waste of his life.

Despite the vile taste in his mouth, the headache and the roiling sensation in his belly, he wanted a drink more than anything. It was a familiar sensation, one that had seized him every day since he had gone to Chekatilo's brothel and sold what shreds of his dignity and self-respect remained to a man he hated.

He pushed his giant frame from the bed, swaying unsteadily and feeling his legs wobble under him. His grey beard was matted with crumbs and he brushed it clear of the detritus of long ago meals, stumbling over to a polished wooden chest sitting in the corner of the room.

Pavel dropped to his knees before the chest and lifted the lid, hunting through his possessions for the bottle of kvas he knew lay within.

'Looking for this?' said a voice behind him.

Pavel groaned, recognising the icy tones of Sofia Valencik. He turned his head to see her standing beside his open door, an upturned and very empty bottle of kvas held in her hands.

'Damn you, woman, that was my last bottle.'

'No it wasn't, but don't bother looking for the others, I emptied them too.'

Pavel's shoulders slumped and he slammed the lid of the chest down before standing and turning to face the ambassador's physician.

'Now why would you go and do that, you damned harpy?' snapped Pavel.

'Because you are too stupid to see what it is doing to you, Pavel Korovic,' retorted Sofia. 'Have you seen yourself recently? You look worse than the beggars on the Urskoy Prospekt and smell worse than a ratcatcher who's fallen in the sewer.'

Pavel angrily waved her words away and returned to his bed, reaching down to lift his boots from the floor. He sat on the edge of the bed, dragging them on and fighting down the urge to vomit.

'Where are you going now?' asked Sofia.

'What business is it of yours?'

'It is my business because I am a physician, Pavel, and it is not in my nature to stand by while another human being attempts to destroy himself with alcohol, no matter how stubborn and pig-headed he may be.'

'I am not trying to destroy myself,' said Pavel, though he could see that Sofia didn't believe him.

'No? Then go back to bed and let me get you something to eat. You need sleep, some food and a wash.'

Pavel shook his head. 'I can't sleep and I don't think I could eat anything anyway.'

'You have to, Pavel,' said Sofia. 'Let me help you, because you'll die if you carry on like this. Is that what you want?'

'Pah! You are exaggerating. I am a son of Kislev, I live for kvas.'

'No,' said Sofia, sadly, 'you will die for kvas. Trust me, I know what I'm talking about.'

'I don't doubt it,' said Pavel, rising from the bed and pushing past Sofia, 'but before you try and save someone, make sure that they want to be saved.'

A fog had descended upon Kislev by the time Kaspar returned to the embassy, wrapping the city in a muffling blanket of icy mist. The cold was worse than Kaspar could ever remember, even in the far north when they had pursued Kajetan into the wilderness.

The Knights Panther had prepared Kajetan for his journey to the Chekist gaol, wrapping him in furs and a hooded cloak to obscure his features. It had now become common knowledge around the city that the Butcherman murders had been committed by Sasha Kajetan, and Kaspar was taking no chances that a lynch mob would take the law into their own hands to administer vigilante justice on the swordsman.

The fog would help also, and as he tightened the saddle on Magnus, he watched Valdhaas help Kajetan onto the back of a horse, since, with his wrists and ankles bound, the swordsman was forced to ride sidesaddle. Kajetan looked up, as though sensing Kaspar's gaze and gave him a vacant look, utterly devoid of human emotion that chilled Kaspar worse than the cloying scraps of fog.

Kaspar shuddered, sensing the hollow emptiness of Kajetan's soul. The man was a void now, drained of emotion and humanity. The swordsman had been unresponsive and lethargic when they had taken him from his cell, and Kaspar feared that he would learn little of whatever twisted fantasies had driven him to murder so many people.

'We're ready to go, ambassador,' said Kurt Bremen, startling Kaspar from his reverie.

'Good,' nodded Kaspar. 'The sooner he's gone from here the happier I'll be.'

'Aye,' agreed Bremen. 'I have lost good men thanks to him.'

'Very well then, let's get this over with, I'm sure Vladimir Pashenko is eager to get his hands on the Butcherman.'

'Do you think he will keep his word and not hang Kajetan the first chance he gets?'

'I don't know.' admitted Kaspar. 'I do not like Pashenko, but I believe he is a man of his word.'

Bremen gave him a sceptical look, but nodded and turned to accept the reins of his horse from his squire. 'What is it you hope to gain by keeping Kajetan alive anyway?'

Kaspar planted a foot in his stirrup cup and hauled himself onto the back of his horse, adjusting his cloak over the animal's rump and tightening his pistol belt.

'I want to know why he killed all those people, and what could make a man do such vile, unthinkable things. Something made him the way he is and I want to know what.'

'I remember asking you on the oblast if you were sure you really wanted to know the answer to that. The question still stands.'

Kaspar nodded, guiding his horse to the embassy gates.

'More than ever, Kurt. I don't know why, but I feel that much depends on knowing those answers.'

Bremen raised his mailed fist and the knights set off, with Kajetan riding in their midst, a ring of steel preventing the swordsman's escape or his murder by a vengeful mob.

Kaspar and Bremen led the way, walking their horses along the street that led to Geroyev Square, the fog so thick that they could barely see the walls to either side of them.

The solemn procession emerged into the square, the fog deadening sounds and forcing them to keep to the edges of the square for fear of losing their bearings. The jingle of the horses' harnesses and their muffled steps through the snow the only sounds that disturbed the eerie silence that had descended upon the city.

They passed shadowy outlines of small encampments of refugees and saw the occasional glow of cooking fires, but even with these touchstones, the silence and sense of isolation were unnerving, especially in a city so thronged with people. People moved like ghosts in the fog, drifting in and out of sight as they moved from the horsemen's path.

Eventually Kaspar and Bremen reached the Urskoy Prospekt, the great triumphal road that led to the Tzarina's Winter Palace and housed the Chekist building. Named for the great reliquary at its end that housed the remains of Kislev's greatest heroes, the wide boulevard was also strangely quiet as they rode along its length, though, looking up, Kaspar could see the weak rays of the sun finally beginning to penetrate the fog.

Ahead, Kaspar could see the grim outer walls of the Chekist building emerge from the mist, a pair of armed men in black armour standing before the imposing black gates. He twisted in the saddle, pulling on the reins and drawing level with Sasha Kajetan. The swordsman glanced up as Kaspar rode alongside him, but said nothing, returning his gaze to the snow.

'Sasha?' said Kaspar.

The swordsman did not reply, lost in whatever thoughts were echoing within his tormented soul.

'Sasha,' repeated Kaspar. 'Do you know where we're going? I am taking you to Vladimir Pashenko of the Chekist. Do you understand?'

Kaspar thought he was going to have to repeat himself again, but almost imperceptibly, Kajetan nodded.

'They will hang me...' whispered the swordsman.

'Eventually, yes, they will,' said Kaspar.

'I am not ready to die. Not yet.'

'It is too late for that, Sasha. You killed a great many people and justice must be done.'

'No,' said Kajetan, 'that's not what I mean. I know I deserve to die for things I have done. I meant that there are things I have yet to do.'

'What do you mean? What kind of things?'

'I know not yet,' admitted Kajetan, raising his head and fixing Kaspar with his dead-eyed stare. 'But know that it involves you.'

Kaspar felt a thrill of fear slick across his skin. Was the swordsman threatening him with violence? Unconsciously, his hand slipped towards his pistol, his thumb hovering over the flint, as he realised just how far away the Knights Panther were from him. It was a few feet at best, but it might as well have been a mile, for Kaspar knew how quick and deadly Kajetan could be. Had Kajetan simply feigned docility so that he might now escape and continue his grisly work?

But it seemed that Kajetan did not have violence in mind, his head drooped again and Kaspar let out a long breath, his eyes narrowing and his brow knitting in puzzlement as he saw something peculiar.

A flickering glow of green light wavered on Kajetan's stomach. Kaspar watched as it slowly eased up his body until it settled in the centre of his chest.

Mystified, Kaspar could see a pencil-thin line of green light, a light that would surely have been invisible but for the fog, tracing an arrow-straight course from Kajetan's chest upwards into the mist.

He waved his hand through the light, feeling a tingling warmth through his thick gloves as he broke its beam. He tried to follow the line of the green light. He soon lost it in the fog. As a breath of wind parted the murk for an instant, he saw a dark, hooded shape atop one of the redbrick buildings of the prospekt silhouetted against the low sun, holding what looked like one of the long rifles made famous by the sharpshooters of Hochland.

Kaspar's heart raced and he reached for one of his flintlocks as he realised what he was seeing.

'Knights Panther!' he yelled, reaching out and dragging Kajetan from his saddle as he heard a sharp crack from above. Instinctively, Kajetan twisted free of Kaspar's grip and the two men tumbled to the snow as something slashed past Kaspar's head and exploded against the wall behind them, blasting bricks and mortar to powder.

Kaspar rolled, the wound in his shoulder flaring as the stitches tore open. He flailed against Kajetan as the swordsman sprang to his feet.

'Kurt! On the roof! Across the street!' shouted Kaspar as the Knights Panther hurriedly wheeled their horses and closed on the struggling pair. Another bang echoed along the prospekt and Kaspar watched horrified as the closest knight was spun from his feet, his shoulder blown out in a shower of red. The knight fell screaming and, behind him, Kaspar could see a smudge of greenish smoke from where the shots had been fired.

He clambered to his feet and took hold of Kajetan as the knights formed a protective cordon of armoured warriors around them. Valdhaas lifted the downed knight to his feet as Kaspar drew his pistol and hurriedly aimed at the rooftop across the prospekt. The chances of hitting anything were negligible, but he fired anyway, the pistol bucking in his hand and further obscuring his view.

'Ambassador! shouted Kurt Bremen. 'Are you hurt?'

'No, I'm fine, but we need to get off the street! Now!'

Bremen nodded, shouting orders to his knights and the group made its halting, stumbling way towards the Chekist building. Kaspar half carried, half dragged Kajetan onwards, the bindings on his ankles limiting the speed at which he could move considerably.

'Pashenko! Vladimir Pashenko!' bellowed Kaspar. 'Open the gates! This is Ambassador von Velten! For the love of Sigmar, open the gates!'

The black armoured soldiers Kaspar had seen standing before the gates emerged from the mist, cudgels at the ready, and, as they saw the desperate group of Imperial knights hurrying towards them, turned to open the gates behind them.

Kaspar knew a disciplined handgunner could load and fire between three and four aimed shots a minute, but a long rifle took somewhat longer, with its finer powder and more exacting preparations. Exactly how much longer, he didn't know and as each second passed, he kept waiting for another shot to pitch one of their number to the snow.

But no shots came and they gratefully hurried through the thick gates of the Chekist building, emerging into a wide, cobbled courtyard before the fortress-like headquarters of Kislev's feared enforcers. Two Chekist hurriedly shut the heavy gate behind them as Kaspar pushed Kajetan to the ground. He took out his other pistol and pointed it at the swordsman, lest he use the confusion of the attack to make his escape. But the prisoner merely knelt in the snow with his head bowed.

Valdhaas lowered the screaming knight to the ground, hurriedly unbuckling his breastplate and shoulder guards to get to the wound. Blood steamed in the cold air as it sheeted down the man's armour. Chekist were running from the building's main door and Kaspar could see Vladimir Pashenko amongst them.

'Is anyone else hurt?' shouted Bremen.

No one else was, and Kaspar felt himself relax a fraction when another crack echoed and a portion of the gateway was blown to splinters as something smashed through. A man screamed and Kaspar saw a Chekist in front of him drop, a bloody hole blasted through his chest. Knights and Chekist alike threw themselves to the ground, horrified that anything could have penetrated the thick timbers of the gateway.

'Everyone inside!' yelled Kaspar, rolling aside and finding himself face to face with Pashenko.

The head of the Chekist nodded and helped Kaspar drag Kajetan towards the doors of the building. The knights and Chekist soldiers backed towards the entrance, anxiously scanning the tallest rooflines for the would-be assassin.

Pashenko kicked open the door and Kaspar fell through it, collapsing in a heap with his back to a corridor wall. Kajetan rolled onto his back, moving out of the way of the open door.

Kaspar did likewise as the last of the knights entered the safety of the building and Pashenko slammed the door shut. He threw heavy iron bolts across before sliding down the wall to rest on his haunches.

'Ursun's blood, what just happened here?' said Pashenko, his face a mask of fury.

'I don't know exactly,' said Kaspar. 'We were riding along the Urskoy Prospekt when someone started shooting at us.'

'Who?' asked Pashenko.

'I didn't see him clearly, just a dark shape, maybe with a hood, on the rooftop.'

'What in Ursun's name was he firing? It penetrated nearly a span of seasoned timber with enough power left to kill one of my men. Save a cannon, what manner of weapon could do such a thing?'

'No blackpowder weapon capable of being carried by a man, that's for sure,' said Kaspar. 'Even the contraptions designed by the College of Engineers in Altdorf are not that powerful.'

'Trouble has a habit of following you,' observed Pashenko.

'Aye, don't I know it,' agreed Kaspar, as two Chekist soldiers lifted Kajetan and led him towards the cells below.

'I would suggest you remain here for a while, ambassador.' said Pashenko, picking himself up and straightening his uniform. 'At least until my men ensure that whoever attacked you is not still lurking and waiting for you to emerge.'

Kaspar rose to his feet and nodded, though as he watched Kajetan's disappearing back, he had the strong impression that whatever the purpose of this attack had been, he had not been the intended target.

V

Nights in the brothel were always busy, filled with men afraid to die affirming that they were alive in the most primal way possible. Chekatilo did not usually trouble himself to visit the main floor, but for reasons he could not fathom, he had decided to drink and smoke amongst the common herd tonight. Most people here had come from the north and would not even know his name, let alone be fearful of him, though the imposing figure of Rejak, standing behind his chair, left no one in any doubt that he was a man not to trifle with.

Chekatilo watched the crowd, seeing the same sick desperation in every face. He saw a young boy, probably barely old enough to need a razor, enthusiastically coupling with a woman draped in red silks and furs. He was watched by a similarly-featured man, old enough to be his father. Chekatilo guessed that this was a fathers last gift to his son: that if he were to die, it would be as a man and not a boy.

Such pathetic scenes were played out throughout the brothel: old men, perhaps desiring one last memory to take to the next life, young men for whom their existence was one long indulgence and those who had already resigned themselves to the fact that life had nothing more to offer them.

'This places reeks of defeat.' muttered Chekatilo to himself. 'The sooner the Kurgan burn it to the ground the better.'

Watching the parade of human misery before him made him all the more sure that he was making the right decision to leave Kislev. He had no great love for his country, and its dour, provincial nature was suffocating for a man of his ambition. Marienburg, with its bustling docks and cosmopolitan nature, was the place for him. He had made a great deal of money in Kislev, but no matter how much he possessed, he would never escape his birth. Respect and esteem were for those of high birth, not for a filthy peasant who had managed to haul himself out of the gutters and fields.

In Marienburg, he would never have to worry about freezing winters and raiding northmen. In Marienburg, he could live like a king, respected and feared.

The thought made him smile, though as Rejak had pointed out, it was a long way to Marienburg - through Talabheim, on to Altdorf and finally westwards to the coast. He would need help to get there safely, but knew exactly how to get it.

The door to the brothel opened and Rejak said, 'Well, well, look who's back again.'

Chekatilo looked up and smiled as he saw Pavel Korovic enter, shivering and stamping his heavy boots free of snow.

'Pavel Korovic, as I live and breathe,' laughed Chekatilo. 'I would have thought he'd had enough of this place to last a lifetime.'

'Korovic?' said Rejak. 'No, ever since he came begging for you to help the ambassador, he's been coming here, swilling bottle after bottle of kvas till dawn before somehow managing to stumble out the door.'

Chekatilo saw Korovic notice him, and blew a smoke ring as the big man nodded curtly before making his way to the bar and tossing a handful of coins to its surface. Korovic snatched the bottle of kvas the barman brought and retreated to an unoccupied table to drown his sorrows. Chekatilo toyed with the idea of going over and speaking to him, but dismissed the thought. What did he have to say to him? Korovic knew his place and Chekatilo had no wish to bandy words with a drunkard.

He caught a flash of swift movement in the corner of the hall and jumped as something bristly rubbed against his leg. Startled, he looked down and saw a sleek, black-furred shape dart beneath his chair.

'Dazh's oath!' he swore disgustedly as another rat, this one the size of a small dog, joined the first. 'Rejak!'

Even as he shouted the name he saw more rats, dozens, scores, hundreds of them, boiling out from unseen lairs to invade his brothel. The screams started seconds later as the tide of vermin attacked, a swarming, squealing mass of furry bodies, pointed snouts and razor-sharp incisors that bit and clawed at exposed flesh.

Chekatilo surged from his chair, toppling it as Rejak stamped down on a rat and broke its spine. He stumbled backwards, horrified as he saw the young boy dragged down by the sheer weight of rats, his face a mask of blood as they ripped off long strips of his flesh. Men and women crawled across the blood-slick floor, unable to believe that this was happening to them as frenziedly biting rats clung to their bodies.

A naked man struggled with a pair of rats while yet more bit and clawed his lower body to the bone. He smashed one rat's skull to splinters against the wall, but another leaped from the stairs and fastened its teeth around his neck, biting out his throat with its powerful jaws. Bright arterial spray spattered the walls as the man collapsed and the scent of so much blood drove the swarming rats into an even greater frenzy.

'Come on!' yelled Rejak, pushing Chekatilo towards the door that led to the chambers at the back of the brothel. Screams and sobs of pain filled the air, mixed with the sounds of breaking glass, smashing furniture and squealing rats. Hundreds of darting black shapes sped through the rooms and corridors of the brothel, as if directed by a malign intelligence, snapping and squealing in a frenzied mass as they attacked with teeth that cut like knives.

A frantic woman, flailing at a rat caught in her hair and biting her neck and shoulders, knocked a lamp from its mounting on the wall. It fell and smashed on her head, spraying blazing oil across her and the floor. She screamed as the flames hungrily seized her clothing, blundering blindly through the brothel and igniting furnishings, spilled alcohol and other patrons as she went. Fire roared through the place with horrifying speed in her wake.

As Rejak pushed him towards safety, Chekatilo saw Pavel Korovic under attack from a dozen or more rats that were biting his legs and arms and raking his chest with their sharp claws. He slashed at them with a broken bottle and stamped on others as he backed towards a shuttered window. A pair of rats leapt towards the giant Kislevite, but he dropped the bottle and caught them in mid-air, slamming them together and dropping the limp corpses as he tore the window shutters from their hinges and leapt through the glass to the street.

Chekatilo yelled as he felt a sharp pain and forgot Pavel Korovic as a rat took a bite from his ankle. He reached down, grabbing the rat by its neck and tearing it from his flesh, ignoring the pain as blood poured from the wound.

The rat twisted and bit his hands, claws like razors drawing blood with every slash. Chekatilo wrung its neck as he saw Rejak sheath his sword and draw a short-bladed dagger, the longer weapon too large to wield effectively against such small, nimble opponents. He stabbed and slashed at any rats that approached, stamping and kicking at those he couldn't kill with his blade.

Rats were closing in around them and Chekatilo barged open the door to the back as another huge rat launched itself at him. He ducked and the rat slammed into the wall behind him. Before it could recover, he turned and hammered his boot down on its chest, hearing a satisfying crack as its ribs shattered.

Smoke, heat and flames filled the brothel as Rejak pushed him through the door, hauling it shut behind him as several heavy thumps slammed into it from the other side. The door shuddered in its frame as the rats hurled themselves at it. Chekatilo could hear splintering, scratching noises as they began gnawing their way through.

'Come on!' shouted Rejak, setting off up the corridor. 'The door won't hold them for long!'

Rejak ushered him into his chambers as he heard wood splinter and saw a pointed snout, wet with blood, push its way through the closed door. Giant teeth ripped the hole wider and Chekatilo watched in disbelief as an enormous rat pushed its wriggling body through. The creature landed on the floor and fixed him with its beady black eyes. It squealed in a high, child-like manner, spraying pink-flecked saliva, and the pounding and scratching noises from the other side of the door doubled in their intensity.

Chekatilo followed Rejak numbly, unable to believe the single-minded intelligence of the rats, and shut the door behind him. Who could believe that vermin would attack in such numbers and with such ferocity? He had never heard the like and could only shake his head at such madness.

He could hear the roaring flames crackling through the door, over the diminishing screams from the main hall, and knew that this place was finished. It was of no matter, he had other places and its loss would barely affect him.

But as he and Rejak made their escape from the burning brothel, he felt a chill in his blood over and above the horrors he had just witnessed. He thought back to the rat that had gnawed its way through the door and locked eyes with him. He had seen its feral intelligence and had been seized by a sudden unshakeable intuition.

He was sure the rat had looked at him with something other than hunger in its eyes.

It had been seeking him.

I

In the closing days of Uriczeit, word reached Kislev that Norscan raiders had sacked Erengrad. Hundreds of longships with sails bearing the marks of the old, northern gods had sailed into the port and disgorged thousands of berserk warriors who had swept through the city and killed thousands in their bloody rampage.