The Charmed Circle

I

There was no doubt in the minds of anyone who had seen the corpse that the word, the correct word, was murder. The way the pelt about the neck had bunched up, caked together like an improperly cleaned worker’s paintbrush; the raw amber hollow in the eye. The official story was that the doctor had broken a magnifying lens and stumbled against it, cutting an artery in the process—but nobody believed it.

The only one they could think of to ask, Ama Clutch, merely smiled when they came to visit, with handfuls of pretty yellowing leaves or a plate of late Pertha grapes. She devoured the grapes and chatted with the leaves. It was an ailment no one had ever seen before.

Glinda—for out of some belated apology for her initial rudeness to the martyred Goat, she now called herself as he had once called her—Glinda seemed to be stricken dumb before the fact of Ama Clutch. Glinda wouldn’t visit, nor discuss the poor woman’s condition, so Elphaba sneaked in once or twice a day. Boq assumed that Ama Clutch suffered a passing malady. But after three weeks Madame Morrible began to make sounds of concern that Elphaba and Glinda—still roomies—had no chaperone. She suggested the common dormitory for them both. Glinda, who would no longer go to see Madame Morrible on her own, nodded and accepted the demotion. It was Elphaba who came up with a solution, mostly to salvage some shred of Glinda’s dignity.

Thus it was that ten days later Boq found himself in the beer garden of the Cock and Pumpkins, waiting for the midweek coach from the Emerald City. Madame Morrible didn’t allow Elphaba and Glinda to join him, so he had to decide for himself which two of the seven passengers alighting were Nanny and Nessarose. The deformities of Elphaba’s sister were well concealed, Elphaba had warned him; Nessarose could even descend from a carriage with grace, providing the step was secure and the ground flat.

He met them, said hello. Nanny was a stewed plum of a woman, red and loose, her old skin looking ready to trail off but for the tucks at the corners of the mouth, the fleshy rivets by the edges of the eyes. More than a score of years in the badlands of Quadling Country had made her lethargic, careless, and saturated with resentment. At her age she ought to have been allowed to nod off in some warm chimney nook. “Good to see a little Munchkinlander,” she murmured to Boq. “It’s like the old times.” Then she turned and said into the shadows, “Come, my poppet.”

Had he not been warned, Boq wouldn’t have taken Nessarose as Elphaba’s sister. She was by no means green, or even blue-white like a genteel person with bad circulation. Nessarose stepped from the carriage elegantly, gingerly, strangely, sinking her heel to touch the iron step at the same time as her toe. Walking as oddly as she did, she drew attention to her feet, which kept eyes away from the torso, at least at first.

The feet landed on the ground, driven there with a ferocious intention to balance, and Nessarose stood before him. She was as Elphaba had said: gorgeous, pink, slender as a wheat stalk, and armless. The academic shawl over her shoulders was cunningly folded to soften the shock.

“Hello, good sir,” she said, nodding her head very slightly. “The valises are on top. Can you manage?” Her voice was as smooth and oiled as Elphaba’s was serrated. Nanny propelled Nessarose gently toward the hansom cab that Boq had engaged. He saw that Nessarose did not move well without being able to lean backward against a steadying hand.

“So now Nanny has to see the girls through their schooling,” said Nanny to Boq as they rode along. “What with their sainted mother in her waterlogged grave these long years, and their father off his head. Well, the family always was bright, and brightness, as you know, decays brilliantly. Madness is the most shining way. The elderly man, the Eminent Thropp, he’s still alive, and sensible as an old ploughshare. Survived his daughter and his granddaughter. Elphaba is the Thropp Third Descending. She’ll be the Eminence one day. As a Munchkinlander, you know about such things.”

“Nanny don’t gossip, it hurts my soul,” Nessarose said.

“Oh my pretty, don’t you fret. This Boq is an old friend, or as good as,” said Nanny. “Out in the swamps of Quadling hell, my friend, we’ve lost the art of conversation. We croak in chorus with what’s left of the froggie folk.”

“I intend to have a headache from shame,” said Nessarose, charmingly.

“But I knew Elphie when she was a small thing,” said Boq. “I’m from Rush Margins in Wend Hardings. I must’ve met you too.”

“Primarily I preferred to reside at Colwen Grounds,” said Nanny. “I was a mortal comfort to the Lady Partra, the Thropp Second Descending. But occasionally I visited Rush Margins. So I may have met you when you were young enough to run around without trousers.”

“How do you do,” said Nessarose.

“The name is Boq,” said Boq.

“This is Nessarose,” said Nanny, as if it were too painful for the girl to introduce herself. “She was to come up to Shiz next year, but we have learned there’s a problem with some Gillikinese minder going loopy. So Nanny is called to step in, and can Nanny leave her sweet? You see why not.”

“A sad mystery, we hope for improvement,” said Boq.

At Crage Hall, Boq witnessed the reunion of the sisters, which was warm and gratifying. Madame Morrible had her Grommetik thing wheel out tea and brisks for the Thropp females, and for Nanny, Boq, and Glinda. Boq, who had begun to worry about Glinda’s retreat into silence, was relieved to see Glinda cast a hard, appraising eye over the elegant dress of Nessarose. How could it be, he wondered if Glinda was wondering, that two sisters should each be disfigured, and should clothe themselves so unlike? Elphaba wore the humblest of dark frocks; today she was in a deep purple, almost a black. Nessarose, balanced on a sofa next to Nanny, who assisted by lifting teacups and crumpling buttery bits of crumpet, was in green silks, the colors of moss, emerald, and yellow-green roses. Green Elphaba, sitting on her other side and lending her support between the shoulders as she tilted her head back to sip her tea, looked like a fashion accessory.

“The whole arrangement is highly unusual,” Madame Morrible was saying, “but we don’t have unlimited room to accommodate peculiarities, alas. We’ll leave Miss Elphaba and Miss Galinda—Glinda is it now, dear? How novel—we’ll leave those two old pals as they are, and we’ll set you up, Miss Nessarose, with your Nanny in the adjoining room that poor old Ama Clutch had. It’s small but you must think of it as cozy.”

“But when Ama Clutch recovers?” asked Glinda.

“Oh, but my dear,” said Madame Morrible, “such confidence the young have! Touching, really.” She continued in a more steely voice. “You have already told me of the long-standing recurrence of this unusual medical condition. I can only assume this has deteriorated into a permanent relapse.” She munched a biscuit in her slow, fishy way, her cheeks going in and out like the leather flaps of a bellows. “Of course we can all hope. Not much more than that, I’m afraid.”

“And we can pray,” Nessarose said.

“Oh well yes, that,” said the Head. “That goes without saying among people of good breeding, Miss Nessarose.”

Boq watched Nessarose and Elphaba both blush. Glinda excused herself and went away. The usual pang of panic Boq felt at her departure was softened by knowing he would see her again in life sciences next week, for, with the new prohibitions on Animal hiring, the colleges had decided to give assembly lectures to all the students from all the colleges, at once. Boq would see Glinda at the first coeducation lecture ever held at Shiz. He couldn’t wait.

Though she had changed. She had surely changed.

2

Glinda was changed. She knew it herself. She had come to Shiz a vain, silly thing, and she now found herself in a coven of vipers. Maybe it was her own fault. She had invented a nonsense disease for Ama Clutch, and Ama Clutch had come down with it. Was this proof of an inherent talent of sorcery? Glinda opted to specialize in sorcery this year, and accepted it as her punishment that Madame Morrible didn’t change her roomie as promised. Glinda no longer cared. Beside Doctor Dillamond’s death, a lot of other matters now seemed insignificant.

But she didn’t trust Madame Morrible either. Glinda had told nobody else that stupid and extravagant lie. So now she would no longer allow Madame Morrible so much as a fingerhold into her life. And Glinda still didn’t have the nerve to confess her unintentional crime to anyone. While she fretted, Boq, that pesky little flea, kept zizzing around her looking for attention. She was sorry she had let him kiss her. What a mistake! Well, all that was behind her now, that trembling on the edges of social disaster. She had seen the Misses Pfannee et cetera for what they were—shallow, self-serving snobs—and she would have no more to do with them.

So Elphaba, no longer a social liability, had all the potential of becoming an actual friend. If being saddled with this broken doll of a baby sister didn’t interfere too much. It was only with prodding that Glinda had gotten Elphaba to talk at all about her sister, so that Glinda might be prepared for Nessarose’s arrival and the enlargement of their social circle.

“She was born at Colwen Grounds, when I was about three,” Elphaba had told her. “My family had gone back to Colwen Grounds for a short stay. It was one of those times of intense drought. Our father told us later, after our mother had died, that Nessarose’s birth had coincided with a temporary resurgence of well water in the vicinity. They’d been doing pagan dances and there was a human sacrifice.”

Glinda had stared at Elphaba, who sounded at once unwilling and offhand.

“A friend of theirs, a Quadling glassblower. The crowd, incited by some rabble-rousing pfaithers and a prophetic clock, fell on him and killed him. A man named Turtle Heart.” Elphaba had pressed the palms of her hands over the high uppers of her stiff black secondhand shoes, and kept her eyes trained on the floor. “I think that was why my parents became missionaries to the Quadling people, why they never went back to Colwen Grounds or Munchkinland.”

“But your mother died in childbirth?” said Glinda. “How could she have been a missionary?”

“She didn’t die for five years,” said Elphaba, looking at the folds of her dress, as if the story were an embarrassment. “She died when our younger brother was born. My father named him Shell, after Turtle Heart, I think. So Shell and Nessarose and I lived the lives of gypsy children, slopping around from Quadling settlement to settlement with Nanny and our father, Frex. He preached, and Nanny taught us and raised us up and kept house such as we ever had, which wasn’t much. Meanwhile the Wizard’s men began draining the badlands to get at the ruby deposits. It never worked, of course. They managed to chase the Quadlings out and kill them, round them up in settlement camps for their own protection and starve them. They despoiled the badlands, raked up the rubies, and left. My father went barmy over it. There never were enough rubies to make it worth the effort; we still have no canal system to run that legendary water from the Vinkus all the way cross-country to Munchkinland. And the drought, after a few promising reprieves, continues unabated. The Animals are recalled to the lands of their ancestors, a ploy to give the farmers a sense of control over something anyway. It’s a systematic marginalizing of populations, Glinda, that’s what the Wizard’s all about.”

“We were talking about your childhood,” said Glinda.

“Well that’s it, that’s all part of it. You can’t divorce your particulars from politics,” Elphaba said. “You want to know what we ate? How we played?”

“I want to know what Nessarose is like, and Shell,” said Glinda.

“Nessarose is a strong-willed semi-invalid,” said Elphaba. “She’s very smart, and thinks she is holy. She has inherited my father’s taste for religion. She isn’t good at taking care of other people because she has never learned how to take care of herself. She can’t. My father required me to baby-sit her through most of my childhood. What she will do when Nanny dies I don’t know. I suppose I’ll have to take care of her again.”

“Oh, what a hideous prospect for a life,” said Glinda, before she could stop herself.

But Elphaba only nodded grimly. “I can’t agree with you more,” she said.

“As for Shell—” continued Glinda, wondering what fresh pain she might tread upon.

“Male, and white, and whole,” she said. “He’s now about ten, I guess. He’ll stay at home and take care of our father. He is a boy, just as boys are. A little dull, maybe, but he hasn’t had the advantages we’ve had.”

“Which are?” prompted Glinda.

“Even for a short time,” said Elphaba, “we had a mother. Giddy, alcoholic, imaginative, uncertain, desperate, brave, stubborn, supportive woman. We had her. Melena. Shell had no mother but Nanny, who did her best.”

“And who was your mother’s favorite?” said Glinda.

“Can’t tell that,” said Elphaba casually, “don’t know. Would have been Shell, probably, since he’s a boy. But she died without seeing him so she didn’t even get that small consolation.”

“Your father’s favorite?”

“Oh, that’s easy,” said Elphaba, jumping up and finding her books on her shelf, and getting ready to run out and stop the conversation in its tracks. “That’s Nessarose. You’ll see why when you meet her. She’d be anyone’s favorite.” She skidded out of the room with no more than a brief flurry of green fingers, a good-bye.

Glinda wasn’t so sure she favored Elphaba’s sister. Nessarose seemed so demanding. Nanny was overly attentive, and Elphaba kept suggesting adjustments in their living arrangements to make things perfect. Hitch the drapes to this angle instead of that, to keep the touch of the sun off Nessarose’s pretty skin. Can we have the oil lamp turned up high so Nessarose can read? Shhh, no chatting after hours; Nessarose has retired and she is such a light sleeper.

Glinda was a bit awed by Nessarose’s freaky beauty. Nessarose dressed well (if not extravagantly). She deflected attention from herself, though, by a system of little social tics—the head lowered in a sudden onslaught of devotion, the eyes batting. It was especially moving—and irritating—to have to wipe away a trickle of tears brought on by some epiphany in Nessarose’s rich inner spiritual life of which bystanders could have no inkling. What did one say?

Glinda began to retreat into her studies. Sorcery was being taught by a louche new instructor named Miss Greyling. She had a gushing respect for the subject but, it soon became apparent, little natural ability. “At its most elemental, a spell is no more than a recipe for change,” she would flute at them. But when the chicken she tried to turn into a piece of toast became instead a mess of used coffee grounds cupped in a lettuce leaf, the students all made a mental note never to accept an invitation to dine with her.

In the back of the room, creeping with pretend invisibility so that she might observe, Madame Morrible shook her head and clucked. Once or twice she could not stop herself from interfering. “No dab hand in the sorcerer’s parlor I,” she would protest, “yet surely Miss Greyling you’ve omitted the steps to bind and convince? I’m merely asking. Let me try. You know I take a special pleasure in our training of sorceresses.” Inevitably Miss Greyling sat on what was left of a previous demonstration, or dropped her purse, collapsing into a heap of shame and mortification. The girls giggled, and didn’t feel that they were learning much.

Or were they? The benefit of Miss Greyling’s clumsiness was that they were not afraid to try for themselves. And she didn’t stint at enthusiasm if a student managed to accomplish the day’s task. The first time Glinda was able to mask a spool of thread with a spell of invisibility, even for a few seconds, Miss Greyling clapped her hands and jumped up and down and broke a heel off her shoe. It was gratifying, and encouraging.

“Not that I have any objection,” said Elphaba one day, when she and Glinda and Nessarose (and, inevitably, Nanny) sat under a pearlfruit tree by the Suicide Canal. “But I have to wonder. How does the university get away with teaching sorcery when its original charter was so strictly unionist?”

“Well, there isn’t anything inherently either religious or nonreligious about sorcery,” said Glinda. “Is there? There isn’t anything inherently pleasure faithist about it either.”

“Spells, changings, apparitions? It’s all entertainment,” said Elphaba. “It’s theatre.”

“Well, it can look like theatre, and in the hands of Miss Greyling it often looks like bad theatre,” admitted Glinda. “But the gist of it isn’t concerned with application. It’s a practical skill, like—like reading and writing. It’s not that you can, it’s what you read or write. Or, if you’ll excuse the play on words, what you spell.”

“Father disapproved mightily,” Nessarose said, in the dulcet tones of the unflappably faithful. “Father always said that magic was the sleight of hand of the devil. He said pleasure faith was no more than an exercise to distract the masses from the true object of their devotion.”

“That’s a unionist talking,” said Glinda, not taking offense. “A sensible opinion, if what you’re up against is charlatans or street performers. But sorcery doesn’t have to be that. What about the common witches up in the Glikkus? They say that they magick the cows they’ve imported from Munchkinland so they don’t go mooing over the edge of some precipice. Who could ever afford to put a fence on every ledge there? The magic is a local skill, a contribution to community well-being. It doesn’t have to supplant religion.”

“It may not have to,” said Nessarose, “but if it tends to, then have we a duty to be wary of it?”

“Oh, wary, well, I’m wary of the water I drink, it might be poisoned,” said Glinda. “That doesn’t mean I stop drinking water.”

“Well, I don’t even think it’s so big an issue,” said Elphaba. “I think sorcery is trivial. It’s concerned with itself mostly, it doesn’t lead outward.”

Glinda concentrated very hard and tried to make Elphaba’s leftover sandwich elevate outward over the canal. She only succeeded in exploding the thing in a small combustion of mayonnaise and shredded carrot and chopped olives. Nessarose lost her balance laughing, and Nanny had to prop her up again. Elphaba was covered in bits of food, which she picked off herself and ate, to the disgust and laughter of everyone else. “It’s all effects, Glinda,” she said. “There’s nothing ontologically interesting about magic. Not that I believe in unionism either,” she protested. “I’m an atheist and an aspiritualist.”

“You say that to shock and scandalize,” said Nessarose primly. “Glinda, don’t listen to a word of her. She always does this, usually to make Father irate.”

“Father’s not around,” Elphaba reminded her sister.

“I stand in for him and I am offended,” said Nessarose. “It’s all very well to turn your nose up at unionism when you have been given a nose by the Unnamed God. It’s quite funny, isn’t it, Glinda? Childish.” She looked spitting angry.

“Father’s not around,” said Elphaba again, in a tone that verged on the apologetic. “You needn’t rush to public defense of his obsessions.”

“What you term his obsessions are my articles of faith,” she said with a chilly clarity.

“Well you’re not a bad sorceress, for a beginner,” said Elphaba, turning to Glinda. “That was a pretty good mess you made of my lunch.”

“Thank you,” Glinda said. “I didn’t mean to pelt you with it. But I am getting better, aren’t I? And out in public.”

“A shocking display,” Nessarose said. “That’s exactly what Father would have deplored about sorcery. The allure is all in the surface.”

“I agree, it still tastes like olives,” Elphaba said, finding a clump of black olive in her sleeve and holding it out on the tip of her finger to her sister’s mouth. “Taste, Nessa?”

But Nessarose turned her face away and lost herself in silent prayer.

3

A few days later Boq managed to catch Elphaba’s eye at the break of their life sciences class, and they met up in an alcove off the main corridor. “What do you think of this new Doctor Nikidik?” he asked.

“I find it hard to listen,” she said, “but that’s because I still want to hear Doctor Dillamond and I can’t believe he’s gone.” On her face was a look of gray submission to impossible reality.

“Well that’s one of the things I’m curious about,” he said. “You told me all about Doctor Dillamond’s breakthrough. Do you know if his lab has been cleared out yet? Maybe there’s something there worth finding. You took the notes for him, couldn’t they be the basis of some proposal, or at least some further study?”

She looked at him with a wiry, strong expression. “Do you think I’m not way ahead of you?” she asked. “Of course I went tramping through there the day his body was found. Before anyone could lace up the door with padlocks and binding spells. Boq, do you take me for a fool?”

“No, I don’t take you for a fool, so tell me what you found,” he said.

“His findings are well hidden away,” she said, “and though there are colossal holes in my training, I am studying it on my own.”

“You mean you’re not going to show me?” He was shocked.

“It was never your particular interest,” she said. “Besides, until there’s something to prove, what’s the point? I don’t think Doctor Dillamond was there yet.”

“I am a Munchkinlander,” he answered proudly. “Look, Elphie, you’ve more or less convinced me what the Wizard is up to. The confining of Animals back onto farms—to give the dissatisfied Munchkinlander farmers the impression he’s doing something for them—and also to provide forced labor for the sinking of useless new wells. It’s vile. But this affects Wend Hardings and the towns that sent me here. I have a right to know what you know. Maybe we can figure it out together, work to make a change.”

“You have too much to lose,” she said. “I’m going to take this on myself.”

“Take what on?”

She only shook her head. “The less you know the better, and I mean for your sake. Whoever killed Doctor Dillamond doesn’t want his findings made public. What kind of a friend would I be to you if I put you at risk too?”

“What kind of friend would I be to you if I didn’t insist?” he retorted.

But she wouldn’t tell him. When he sat next to her during the rest of the class and passed her little notes, she ignored them all. Later he thought that they might have developed a genuine impasse in their friendship had the odd attack on the newcomer not occurred during that very session.

Doctor Nikidik had been lecturing on the Life Force. Entwining around each wrist the two separate tendrils of his long straggly beard, he spoke in falling tones so that only the first half of each sentence made it to the back of the room. Hardly a single student was following. When Doctor Nikidik took a small bottle from his vest pocket and mumbled something about “Extract of Biological Intention,” only the students in the front row sat up and opened their eyes. For Boq and Elphaba, and everyone else, the patter ran—“A little sauce for the soup mumble mumble, as if creation were an unconcluded mumble mumble mumble, notwithstanding the obligations of all sentient mumble mumble mumble, and so as a little exercise to make those nodding off in the back of the mumble mumble mumble, behold a little mundane miracle, courtesy of mumble mumble mumble.”

A frisson of excitement had woken everyone up. The Doctor uncorked the smoky bottle and made a jerky movement. They could all see a small puff of dust, like an effervescence of talcum powder, jostle itself in a swimming plume in the air above the neck of the bottle. The Doctor rowed his hands a couple of times, to start the air currents eddying upward. Keeping some rare sort of spatial coherence, the plume began to migrate upward and over. The ooohs that the students were inclined to make were all postponed. Doctor Nikidik held a finger out to them to shush them, and they could tell why. A vast intake of breath would change the pattern of air currents and divert the floating musk of powder. But the students began to smile, despite themselves. Above the stage, amid the standard ceremonial stags’ horns and brass trumpets on braid, hung four oil portraits of the founding fathers of Ozma Towers. In their ancient garb and serious expressions they looked down on today’s students. If this “biological intention” were to be applied to one of the founding fathers, what would he say, seeing men and women students together in the great hall? What would he have to say about anything? It was a grand moment of anticipation.

But when a door to the side of the stage opened, the mechanics of the air currents were disturbed. A student looked in, puzzled. A new student, oddly dressed in suede leggings and a white cotton shirt, with a pattern of blue diamonds tattooed on the dark skin of his face and hands. No one had seen him before, or anyone like him. Boq clutched Elphaba’s hand tightly and whispered, “Look! A Winkie!”

And so it seemed, a student from the Vinkus, in strange ceremonial garb, coming late for class, opening the wrong door, confused and apologetic, but the door had shut behind him and locked from this side, and there were no nearby seats available in the front rows. So he dropped where he was and sat with his back against the door, hoping, no doubt, to look inconspicuous.

“Drat and damn, the thing’s been shabbed off course,” said Doctor Nikidik. “You fool, why don’t you come to class on time?”

The shining mist, about the size of a bouquet of flowers, had veered upward in a draft, and it bypassed the ranks of long-dead dignitaries waiting an unexpected chance to speak again. Instead it cloaked one of the racks of antlers, seeming for a few moments to hang itself on the twisting prongs. “Well, I can scarcely hope to hear a word of wisdom from them, and I refuse to waste any more of this precious commodity on classroom demonstrations,” said Doctor Nikidik. “The research is still incomplete and I had thought that mumble mumble mumble. Let you discover for yourselves if mumble mumble mumble. I should hardly wish to prejudice your mumble.”

The antlers suddenly took a convulsive twist on the wall, and wrenched themselves out of the oaken paneling. They tumbled and clattered to the floor, to the shrieking and laughing of the students, especially because for a minute Doctor Nikidik didn’t know what the uproar was about. He turned around in time to see the antlers right themselves and wait, quivering, twitching, on the dais, like a fighting cock all nastied up and ready to go into the ring.

“Oh well, don’t look at me,” said Doctor Nikidik, collecting his books, “I didn’t ask for anything from you. Blame that one if you must.” And he casually pointed at the Vinkus student, who was cowering so wide-eyed that the more cynical of the older students began to suspect this was all a setup.

The antlers stood on their points and skittered, crablike, across the stage. As the students rose in a common scream, the antlers scrabbled up the body of the Vinkus boy and pinned him against the locked door. One wing of the rack caught him by the neck, shackling him in its V yoke, and the other reared back in the air to stab him in the face.

Doctor Nikidik tried to move fast, and fell to his arthritic knees, but before he could right himself two boys were up on the stage, out of the front row, grabbing the antlers and wrestling them to the ground. The Vinkus boy shrieked in a foreign tongue. “That’s Crope and Tibbett!” said Boq, jouncing Elphaba in the shoulder, “look!” The sorcery students were all jumping on their seats and trying to lob spells at the murderous antlers, and Crope and Tibbett found their grips and lost them and found them again, until at last they succeeded in breaking off one driving tine, then another, and the pieces, still twitching, fell to the stage floor without further momentum.

“Oh the poor guy,” said Boq, for the Vinkus student had slumped down and was volubly weeping behind his blue-diamonded hands. “I never saw a student from the Vinkus before. What an awful welcome to Shiz.”

The attack on the Vinkus student provoked gossip and speculation. In sorcery the next day Glinda asked Miss Greyling to explain something. “How could Doctor Nikidik’s Extract of Biological Intention or whatever it was, how could it fall under the heading of life sciences when it behaved like a master spell? What really is the difference between science and sorcery?”

“Ah,” said Miss Greyling, choosing this moment to apply herself to the care of her hair. “Science, my dears, is the systematic dissection of nature, to reduce it to working parts that more or less obey universal laws. Sorcery moves in the opposite direction. It doesn’t rend, it repairs. It is synthesis rather than analysis. It builds anew rather than revealing the old. In the hands of someone truly skilled”—at this she jabbed herself with a hair pin and yelped—“it is Art. One might in fact call it the Superior, or the Finest, Art. It bypasses the Fine Arts of painting and drama and recitation. It doesn’t pose or represent the world. It becomes. A very noble calling.” She began to weep softly with the force of her own rhetoric. “Can there be a higher desire than to change the world? Not to draw Utopian blueprints, but really to order change? To revise the misshapen, reshape the mistaken, to justify the margins of this ragged error of a universe? Through sorcery to survive?”

At teatime, still awed and amused, Glinda reported Miss Greyling’s little heartfelt speech to the two Thropp sisters. Nessarose said, “Only the Unnamed God creates, Glinda. If Miss Greyling confuses sorcery with creation she is in grave danger of corrupting your morals.”

“Well,” said Glinda, thinking of Ama Clutch on the bed of mental pain Glinda had once imagined for her, “my morals aren’t in the greatest shape to start out with, Nessa.”

“Then if sorcery is to be helpful at all, it must be in reconstructing your character,” said Nessarose firmly. “If you apply yourself in that direction, I suspect it will be all right in the end. Use your talent at sorcery, don’t be used by it.”

Glinda suspected that Nessarose might develop a knack for being witheringly superior. She winced in advance, even while taking Nessarose’s suggestion to heart.

But Elphaba said, “Glinda, that was a good question. I wish Miss Greyling had answered it. That little nightmare with the antlers looked more like magic than science to me, too. The poor Vinkus fellow! Suppose we ask Doctor Nikidik next week?”

“Who ever would have the courage to do that?” cried Glinda. “Miss Greyling is at least ridiculous. Doctor Nikidik, with that lovable bumbling mumbling incoherent way he has—he’s so distinguished.”

At the life sciences lecture the following week, all eyes were on the new Vinkus boy. He arrived early and settled himself in the balcony, about as far from the lectern as he could get. Boq had the suspicion of nomads all settled farmers possessed. But Boq had to admit that the expression in the new boy’s eyes was intelligent. Avaric, sliding into the seat next to Boq, said, “He’s a prince, they say. A prince without a purse or a throne. A pauper noble. In his particular tribe, I mean. He stays at Ozma Towers and his name is Fiyero. He’s a real Winkie, full-blood. Wonder what he makes of civilization?”

“If that was civilization, last week, he must long for his own barbaric kind,” said Elphaba from the seat on the other side of Boq.

“What’s he wearing such silly paint for?” said Avaric. “He only draws attention to himself. And that skin. I wouldn’t want to have skin the color of shit.”

“What a thing to say,” said Elphaba. “If you ask me, that’s a shitty opinion.”

“Oh please,” said Boq. “Let’s just shut up.”

“I forgot, Elphie, skin is your issue too,” said Avaric.

“Leave me out of this,” she said. “We just had lunch, and you give me dyspepsia, Avaric. You and the beans we had at lunch.”

“I’m changing my seat,” warned Boq, but Doctor Nikidik came in just then, and the class rose to its feet in routine respect, then settled back noisily, chummily, chattering.

For a few minutes Elphaba waved her hand to get the Doctor’s attention, but she was sitting too far back and he was burbling on about something else. She finally leaned over to Boq and said, “At the recess I’ll change my seat and go forward so he can see me.” Then the class watched as Doctor Nikidik finished his inaudible preamble and beckoned a student to open the same door at the side of the stage that Fiyero had stumbled through the previous week.

In came a boy from Three Queens rolling a table like a tea tray. On it, crouched as if to make itself as small as possible, was a lion cub. Even from the balcony they could sense the terror of the beast. Its tail, a little whip the color of mashed peanuts, lashed back and forth, and its shoulders hunched. It had no mane to speak of yet, it was too tiny. But the tawny head twisted this way and that, as if counting the threats. It opened its mouth in a little terrified yawp, the infant form of an adult roar. All over the room hearts melted and people said “Awwwwww.”

“Hardly more than a kitten,” said Doctor Nikidik. “I had thought to call it Prrr, but it shivers more often than it purrs, so I call it Brrr instead.”

The creature looked at Doctor Nikidik, and removed itself to the far edge of the trolley.

“Now the question of the morning is this,” said Doctor Nikidik. “Picking up from the somewhat skewed interests of Doctor Dillamond, who mumble mumble. Who can tell me if this is an Animal or an animal?”

Elphaba didn’t wait to be called on. She stood up in the balcony and launched her answer out in a clear, strong voice. “Doctor Nikidik, the question you asked was who can tell if this is an Animal or an animal. It seems to me the answer is that its mother can. Where is its mother?”

A buzz of amusement. “Caught in the swamp of syntactical semantics, I see,” said the Doctor merrily. He spoke louder, as if having only now realized that there was a balcony in the hall. “Well done, Miss. Let me rephrase the question. Will someone here venture a hypothesis as to the nature of this specimen? And give a reason for such an assessment? We see before us a beast at a tender age, long before any such beast could command language if language were part of its makeup. Before language—assuming language—is this still an Animal?”

“I repeat my question, Doctor,” sang out Elphaba. “This is a very young cub. Where is its mother? Why is it taken from its mother at such an early age? How even can it feed?”

“Those are impertinent questions to the academic issue at hand,” said the Doctor. “Still, the youthful heart bleeds easily. The mother, shall we say, died in a sadly timed explosion. Let us presume for the sake of argument that there was no way of telling whether the mother was a Lioness or a lioness. After all, as you may have heard, some Animals are going back to the wild to escape the implications of the current laws.”

Elphaba sat down, nonplused. “It doesn’t seem right to me,” she said to Boq and Avaric. “For the sake of a science lesson to drag a cub in here without its mother. Look how terrified it is. It is shivering. And it can’t be cold.”

Other students began to venture opinions, but the Doctor shot them down one by one. The point being, apparently, that without language or contextual clues, at its infant stages a beast was not clearly Animal or animal.

“This has a political implication,” said Elphaba loudly. “I thought this was life sciences, not current events.”

Boq and Avaric shushed her. She was getting a terrible reputation as a loudmouth.

The Doctor dragged the episode out long after everyone had digested the point. But finally he turned and said, “Now do you think that if we could cauterize that part of the brain that develops language, we could eliminate the notion of pain and thus its existence? Early tests on this little tom lion show interesting results.” He had picked up a small hammer with a rubber head, and a syringe. The beast drew itself up and hissed, and then backed up and fell on the floor, and streaked toward the door, which had closed and locked from this side as it had the previous week.

But it wasn’t only Elphaba who was on her feet yelling. Half a dozen students were shouting at the Doctor. “Pain? Eliminate pain? Look at the thing, it’s terrified! It already gets pain! Don’t do that, what are you, crazy?”

The Doctor paused, visibly tightening his grip on the mallet. “I will not preside over such shocking refusal to learn!” he said, affronted. “You are leaping to harebrained conclusions based on sentiment and no observation. Bring the beast here. Bring it back. Young lady, I insist. I shall be quite cross.”

But two girls from Briscoe Hall disobeyed and ran out of the room carrying the clawing lion club in an apron between them. The room collapsed in an uproar and Doctor Nikidik stalked off the stage. Elphaba turned to Boq and said, “Well, I guess I don’t get to ask Glinda’s good question about the difference between science and sorcery, do I? We were definitely headed down a different path today.” But her voice was shaking.

“You felt for that beast, didn’t you?” Boq was touched. “Elphie, you’re trembling. I don’t mean this in an insulting way, but you’ve nearly gone white with passion. Come on, let’s sneak out and get a tea at the café at Railway Square, for old times’ sake.”

4

Perhaps every accidental cluster of people has a short period of grace, in between the initial shyness and prejudice on the one hand and eventual repugnance and betrayal on the other. For Boq it seemed that his summer obsession with the-then-Galinda made sense if only to usher in this following, more mature comfort with a circle of friends who had begun to feel inevitably and permanently connected.

The boys still weren’t allowed access to Crage Hall, nor the girls to the boys’ schools, but the city centre area of Shiz became an extension of the parlors and lecture halls in which they were allowed to mingle. On a midweek afternoon, on a weekend morning, they would meet by the canal with a bottle of wine, or in a café or student watering hole, or they would walk about and discuss the fine points of Shiz architecture, or they would laugh about the excesses of their teachers. Boq and Avaric, Elphaba and Nessarose (with Nanny), Glinda, and sometimes Pfannee and Shenshen and Milla, and sometimes Crope and Tibbett. And Crope brought Fiyero along and introduced him, which frosted Tibbett for a week or so until the evening that Fiyero said, in his shy formal way, “Of course—I have been married for some time. We marry young in the Vinkus.” The others were agog at the notion, and felt juvenile.

To be sure, Elphaba and Avaric needled each other mercilessly. Nessarose tried everyone’s patience with her religious rantings. Crope’s and Tibbett’s stream of saucy remarks got them dumped in the canal more than once. But Boq was relieved to find that his crush on Glinda was lifting somewhat. She sat on the edge of the picnic blanket with a look of self-reliance, and she diverted conversation away from herself. He had loved the girl who had loved the glamour in herself, and that girl seemed to have disappeared. But he was happy to have Glinda as a friend. Well, in a nutshell: he had loved Galinda and this now was Glinda. Someone he could no longer quite figure out. Case closed.

It was a charmed circle.

All the girls steered clear of Madame Morrible while they could. One cold evening, however, Grommetik came hunting for the Thropp sisters. Nanny huffed and wound the strings of a fresh apron around her waist, and prodded Nessarose and Elphaba downstairs toward the parlor of the Head.

“I hate that Grommetik thing,” said Nessarose. “However does it work, anyway? Is it clockwork or is it magicked, or some combination of the two?”

“I always imagined a bit of nonsense—that there was a dwarf inside, or an acrobatic family of elves each working a limb,” said Elphaba. “Whenever Grommetik comes around, my hand gets a strange hunger for a hammer.”

“I can’t imagine,” Nessarose said. “Hand hunger, I mean.”

“Hush, you two, the thing has ears,” Nanny said.

Madame Morrible was glancing through the financial papers, making a few marks in the margin before she deigned to acknowledge her students. “This won’t take but a moment,” she said. “I’ve had a letter from your dear father, and a package for you. I thought it kindest to deliver the news myself.”

“News?” said Nessarose, blanching.

“He could have written to us as well as to you,” said Elphaba.

Madame Morrible ignored her. “He writes to ask of Nessarose’s health and progress, and to tell you both that he is going to undertake a fast and penance for the return of Ozma Tippetarius.”

“Oh, the blessed little girl,” said Nanny, warming to one of her favorite subjects. “When the Wizard took over the Palace all those years ago and he had the Ozma Regent jailed, we all thought that the sainted Ozma child would call down disaster upon the Wizard’s head. But they say she’s been spirited away and frozen in a cave, like Lurlina. Has Frexspar got the mettle to melt her—is now her time to return?”

“Please,” said Madame Morrible to the sisters, with a sour glance at Nanny, “I haven’t asked you here so that your Nanny could discuss this contemporary apocrypha, nor to slander our glorious Wizard. It was a peaceful transition of power. That the Ozma Regent’s health failed while under house arrest was a mere coincidence, nothing more. As to the power of your father to raise the missing royal child from some unsubstantiated state of somnolence—well, you’ve as much as admitted to me that your father is erratic, if not mad. I can only wish him health in his endeavors. But I feel it my duty to point out to you girls that we do not smile on seditious attitudes at Crage Hall. I hope you have not imported your father’s royalist yearnings into the dormitories here.”

“We assign ourselves to the Unnamed God, not to the Wizard nor to any possible remnant of the Royal Family,” Nessarose said proudly.

“I have no feeling on the matter at all,” muttered Elphaba, “except that Father loves lost causes.”

“Very well,” said the Head. “As it should be. Now I have had a package for you.” She handed it to Elphaba, but added, “It is for Nessarose, I think.”

“Open it, Elphie, please,” said Nessarose. Nanny leaned forward to look.

Elphaba undid the cord and opened the wooden box. From a pile of ash shavings she withdrew a shoe, and then another. Were they silver?—or blue?—or now red?—lacquered with a candy shell brilliance of polish? It was hard to tell and it didn’t matter; the effect was dazzling. Even Madame Morrible gasped at their splendor. The surface of the shoes seemed to pulse with hundreds of reflections and refractions. In the firelight, it was like looking at boiling corpuscles of blood under a magnifying glass.

“He writes that he bought them for you from some toothless tinker woman outside Ovvels,” said Madame Morrible, “and that he dressed them up with silver glass beads that he made himself—that someone had taught him to make?—”

“Turtle Heart,” said Nanny darkly.

“—and”— Madame Morrible flipped the letter over, squinting—“he says he had hoped to give you something special before you left for university, but in the sudden circumstances of Ama Clutch’s sickness . . . blah blah . . . he was unprepared. So now he sends them to his Nessarose to keep her beautiful feet warm and dry and beautiful, and he sends them with his love.”

Elphaba drove her fingers through the curlicues of shavings. There was nothing else in the box, nothing for her.

“Aren’t they gorgeous!” Nessarose exclaimed. “Elphie, fix them on my feet, would you please? Oh, how they sparkle!”

Elphaba went on her knees before her sister. Nessarose sat as regal as any Ozma, spine erect and face glowing. Elphaba lifted her sister’s feet and slipped off the common house slippers, and replaced them with the dazzling shoes.

“How thoughtful he is!” said Nessarose.

“Good thing you can stand on your own two feet, you,” muttered Nanny to Elphaba, and put her old hand patronizingly on Elphaba’s shoulder blades, but Elphaba shrugged it away.

“They’re just gorgeous,” said Elphaba thickly. “Nessarose, they’re made for you. They fit like a dream.”

“Oh, Elphie, don’t be cross,” Nessarose said, looking down at her feet. “Don’t ruin my small happiness with resentment, will you? He knows you don’t need this kind of thing . . .”

“Of course not,” said Elphaba. “Of course I don’t.”

That evening the friends risked breaking curfew by ordering another bottle of wine. Nanny tutted and fretted, but as she kept downing her portion as neatly as anyone else, she was overruled. Fiyero told the story of how he had been married at the age of seven to a girl from a neighboring tribe. They all gawped at his apparent lack of shame. He had only seen his bride once, by accident, when they were both about nine. “I won’t really take up with her until we are twenty, and I’m now only eighteen,” he added. With the relief of imagining he might still be as virginal as the rest of them, they ordered yet another bottle of wine.

The candles guttered, a small autumnal rain fell. Though the room was dry, Elphaba drew her cloak about her as if anticipating the walk home. She had gotten over the sting of being overlooked by Frex. She and Nessarose began to tell funny stories about their father, as if to prove to themselves and to everyone else that nothing was amiss. Nessarose, who wasn’t much of a drinker, allowed herself to laugh. “Despite my appearance, or maybe because of it, he always called me his beautiful pet,” she said, alluding to her lack of arms for the first time in public. “He would say, ‘Come here, my pet, and let me give you a piece of apple.’ And I would walk over as best I could, tilting and tottering if Nanny or Elphie or Mother wasn’t around to support me, and fall into his lap, and lean up smiling, and he’d drop small pieces of fruit into my mouth.”

“What did he call you, Elphie?” asked Glinda.

“He called her Fabala,” interrupted Nessarose.

“At home, at home only,” Elphaba said.

“True, you are your father’s little Fabala,” crooned Nanny, almost to herself, just outside the circle of smiling faces. “Little Fabala, little Elphaba, little Elphie.”

“He never called me pet,”’ said Elphaba, raising her glass to her sister. “But we all know he told the truth, as Nessarose is the pet in the family. Hence those splendid shoes.”

Nessarose blushed and accepted a toast. “Ah, but while I had his attention because of my condition, you captured his heart when you sang,” she said.

“Captured his heart? Hah. You mean I performed a necessary function.”

But the others said to Elphaba, “Oh, do you sing? Well then! Sing, sing, you must! Another bottle, another glass, push back the chair, and before we leave for the night, you must sing! Go on!”

“Only if the others will,” said Elphaba, bossily. “Boq? Some Munchkinlander spinniel? Avaric, a Gillikinese ballad? Glinda? Nanny, a lullaby?”

“We know a dirty round, we’ll go next if you go,” said Crope and Tibbett.

“And I will sing a Vinkus hunting chant,” said Fiyero. Everyone chortled with pleasure and clapped him on the back. So then Elphaba had to stand, push her chair aside, clear her throat and sound a note into her cupped hands, and start. As if she were singing for her father, again, after all this time.

The bar mother slapped her rag at some noisy older men to shush them, and the dart players dropped their hands to their sides. The room quieted down. Elphaba made up a little song on the spot, a song of longing and otherness, of far aways and future days. Strangers closed their eyes to listen.

Boq did too. Elphaba had an okay voice. He saw the imaginary place she conjured up, a land where injustice and common cruelty and despotic rule and the beggaring fist of drought didn’t work together to hold everyone by the neck. No, he wasn’t giving her credit: Elphaba had a good voice. It was controlled and feeling and not histrionic. He listened through to the end, and the song faded into the hush of a respectful pub. Later, he thought: The melody faded like a rainbow after a storm, or like winds calming down at last; and what was left was calm, and possibility, and relief.

“You next, you promised,” cried Elphaba, pointing at Fiyero, but nobody would sing again, because she had done so well. Nessarose nodded to Nanny to wipe a tear from the corner of her eye.

“Elphaba says she’s not religious but see how feelingly she sings of the afterlife,” said Nessarose, and for once no one was inclined to argue.

5

Early one morning, when the world was hoary with rimefrost, Grommetik arrived with a note for Glinda. Ama Clutch, it seemed, was on her way out. Glinda and her roommates hurried to the infirmary.

The Head met them there, and led them to a windowless alcove. Ama Clutch was thrashing about in the bed and talking to the pillowcase. “Don’t put up with me,” she was saying wildly, “for what will I ever do for you? I will abuse your good nature, duckie, and rest my oily locks upon your fine close weave and I will be picking with my teeth at your lacy appliquéd edge! You are a stupid nuisance to allow it, I say! I don’t care about notions of service! It’s all bunk, I tell you, bunk!”

“Ama Clutch, Ama Clutch, it’s me,” said Glinda. “Listen, dear, it’s me! It’s your little Galinda.”

Ama Clutch turned her head from side to side. “Your protest is insulting to your forebears!” she went on, rolling her eyes toward the pillowcase again. “Those cotton plants on the banks of Restwater didn’t allow themselves to be harvested so you could lie down like a mat and let any filthy person slobber all over you with night drool! It don’t make a lick of sense!”

“Ama!” Glinda wept. “Please! You’re raving!”

“Aha, I see you have nothing to say to that,” said Ama Clutch with satisfaction.

“Come back, Ama, come back, one more time before you go!”

“Oh sweet Lurline, this is dreadful,” Nanny said. “Darlings, if I ever get like this, poison me, will you?”

“She’s going, I can see it,” Elphaba said. “I saw it enough in Quadling Country, I know the signs. Glinda, say what you need to say, quickly.”

“Madame Morrible, may I have privacy?” Glinda said.

“I will stay by your side and support you. It’s my duty to my girls,” said the Head, settling her hamlike hands determinedly on her waist. But Elphaba and Nanny got up and elbowed her out of the alcove, down the hall, and through the door and closed it and locked it. Nanny clucked all the while, saying, “Now, isn’t that nice of you, Madame Head, but no need. No need at all.”

Glinda gripped Ama Clutch’s hand. Beads of white sweat were forming like potato water on the servant’s forehead. She struggled to pull her hand away but her strength was going. “Ama Clutch, you’re dying,” Glinda said, “and it’s my fault.”

“Oh stop,” Elphaba said.

“It is,” Glinda said fiercely, “it is.”

“I’m not arguing that,” said Elphaba, “I just mean cut yourself out of the conversation; this is her death, not your interview with the Unnamed God. Come on. Do something!”

Glinda grabbed the hands, both hands, even tighter. “I am going to magick you back,” she said between gritted teeth. “Ama Clutch, you do as I say! I’m still your employer and your better, and you have to obey me! Now listen to this spell and behave yourself!”

The Ama’s teeth gnashed, the eyes rolled, and the chin twisted knobbily, as if trying to impale some invisible demon in the air above her bed. Glinda’s eyes shut and her jaw worked, and a thread of sound, syllables incoherent even to herself, came spooling out from her blanched lips. “Hope you don’t explode her like a sandwich,” muttered Elphaba.

Glinda ignored this. She hummed and worked, she rocked and panted. Ama Clutch’s eyelids moved so frantically over the closed eyes that it looked as if her eye sockets were chewing her own eyes. “Magicordium senssus ovinda clenx,” Glinda concluded out loud, “and if that doesn’t do it, I give up; even the smells and bells of a full kit wouldn’t help, I think.”

On the straw pallet Ama Clutch fell back. A little blood ran from the outer edge of each eye. But the wild turning motion of the focus had shuttered itself down. “Oh my dear,” she murmured, “so you’re all right then, or am I dead now?”

“Not yet,” said Glinda. “Yes, dear Ama, yes, I’m fine. But sweetheart, I think you’re going.”

“Of course I am, the Wind is here, can’t you hear it?” Ama Clutch said. “No matter. Oh there’s Elphie, too. Good-bye, my ducks. Stay out of the Wind until the time is right or you’ll be blown in the wrong direction.”

Glinda said, “Ama Clutch, I have something to say to you—I have to make my apology—”

But Elphaba leaned forward, cutting Glinda off from Ama Clutch’s line of sight, and said, “Ama Clutch, before you go, tell us who killed Doctor Dillamond.”

“Surely you know that,” Ama Clutch said.

“Make us sure,” Elphaba said.

“Well, I saw it, I mean nearly. It had just happened and the knife was still there”—Ama Clutch worked for breath—“smeared with blood that hadn’t had a chance to dry.”

“What did you see? This is important.”

“I saw the knife in the air, I saw the Wind come to take Doctor Dillamond away, I saw the clockwork turn and the Goat’s time stop.”

“It was Grommetik, wasn’t it,” Elphaba murmured, trying to get the old woman to speak the words.

“Well, that’s what I’m saying, duckie,” said Ama Clutch.

“And did it see you, did it turn on you?” cried Glinda. “Did that make you ill, Ama Clutch?”

“It was my time to be ill,” said Ama Clutch gently, “so I couldn’t complain. And it is my time to die, so leave me be. Just hold my hand, dear.”

“But the fault is mine—” began Glinda.

“You would do me more good if you hushed, sweet Galinda, my duck,” said Ama Clutch gently, and patted Glinda’s hand. Then she closed her eyes and breathed in and out a couple of times. They sat there in a silence that seemed peculiarly servant-class-Gillikinese, though it was hard, later on, to explain why. Outside, Madame Morrible moved up and down the floorboards, pacing. Then they imagined they heard a Wind, or an echo of a Wind, and Ama Clutch was gone, and the overly subordinate pillowcase took a small spill of human juice from the edge of her slackened mouth.

6

The funeral was modest, a love-her-and-shove-her affair. Glinda’s close friends attended, filling two pews, and in the second tier of the chapel a flock of Amas made a professional coterie. The rest of the chapel was empty.

After the corpse in its winding sheet slid along the oiled chute to the furnace, the mourners and colleagues retired to Madame Morrible’s private parlor, where she proved to have sanctioned no expense in the refreshments. The tea was ancient stock, stale as sawdust, the biscuits were hard, and there was no saffron cream or tamorna marmalade. Glinda said reprovingly to the Head, “Not even a small bowl of cream?” and Madame Morrible answered, “My girl, I try to protect my charges from the worst of the food shortages by judicious shopping and by going without myself, but I am not wholly responsible for your ignorance. If only people would obey the Wizard absolutely, there would be abundance. Don’t you realize that conditions verge on famine and cows are dying of starvation two hundred miles from here? This makes saffron cream very dear in the market.” Glinda began to move away, but Madame Morrible reached out a raft of cushiony, bulbous, bejeweled fingers. The touch made Glinda’s blood run cold. “I should like to see you, and Miss Nessarose, and Miss Elphaba,” said the Head. “After the guests leave. Please wait behind.”

“We’re nabbed for a lecture,” whispered Glinda to the Thropp sisters. “We have to be yelled at.”

“Not a word about what Ama Clutch said—or that she came back,” said Elphaba urgently. “Got that, Nessa? Nanny?”

They all nodded. Boq and Avaric, making their good-byes, said that the group was reconvening at the pub in the Regent’s Parade. The girls agreed to meet them there after their interview with the Head. They would manage a more honest memorial service for Ama Clutch at the Peach and Kidneys.

When the small crowd had dispersed, only Grommetik clearing away the cups and crumbs, Madame Morrible herself banked up the fire—a gesture of chumminess lost on no one—and sent Grommetik away. “Later, thingy,” she said, “later. Go lubricate yourself in some closet somewhere.” Grommetik wheeled away with, if it was possible, an offended air. Elphaba had to repress an urge to kick it with the tip of her stout black walking boot.

“You too, Nanny,” Madame Morrible said. “A little break from your labors.”

“Oh no,” Nanny said. “Nanny doesn’t leave her Nessa.”

“Yes Nanny does. Her sister is perfectly capable of caring for her,” said the Head. “Aren’t you, Miss Elphaba? The very soul of charity.”

Elphaba opened her mouth—the word soul always provoked her, Glinda knew—but closed it again. She made a wincing nod toward the door. Without a word, Nanny got up to leave, but before the door closed behind her Nanny said, “It’s not my place to complain, but really: no cream? At a funeral?”

“Help,” said Madame Morrible when the door closed, but Glinda wasn’t sure if this was a criticism of servants or a bid for sympathy. The Head rallied herself by arranging her skirts and the vents and braids of her smart parlor jacket. In orangey copper sequins she looked like a huge, upholstered, upended goldfish goddess. How ever did she get to be Head? Glinda wondered.

“Now that Ama Clutch has gone to ash, we shall, nay, we must move bravely on,” Madame Morrible began. “My girls, may I first ask you to recount the sad story of her last words. It is essential therapy in your recovery from grief.”

The girls didn’t look at one another. Glinda, in this situation the spokesperson, took a breath and said, “Oh, she spewed nonsense to the last.”

“No surprise, the dotty old thing,” said Madame Morrible, “but what nonsense?”

“We couldn’t make it out,” said Glinda.

“I had wondered if she talked about the death of the Goat.”

Glinda said, “Oh the Goat? Well I could hardly tell—”

“I suspected that, in her deranged condition, she might return to that critical moment. The dying often try to make sense, at the last possible moment, of the puzzles of their lives. Useless effort, of course. No doubt Ama Clutch was puzzled by what she came across, the Goat’s body, the blood. And Grommetik.”

“Oh?” said Glinda faintly. The sisters beside her were careful not to stir.

“That terrible morning I was up early—at my spiritual meditations—and I noticed the light in Doctor Dillamond’s lab. So I sent Grommetik over with a cheering pot of tea for the old Goat. Grommetik found the Animal slumped over a broken lens; he’d apparently stumbled and severed his own jugular vein. Such a sad accident, born of academic zeal (not to say hubris) and a pitiful lack of common sense. Rest, we all need rest, the brightest of us need our rest. Grommetik in its confusion felt for a pulse—none to be found—and I surmise that is just when Ama Clutch arrived. To see dear Grommetik splashed with the spurts of a strong circulatory pulse. Ama Clutch arrived out of nowhere and none of her business, I might add, but let’s not malign the dead, shall we?”

Glinda gulped back new tears, and did not mention that Ama Clutch had mentioned seeing something unusual the evening before, and had wandered out to check.

“I did always think that the shock of all that blood might have been the final straw that sent Ama Clutch pitching back into her ailment. Incidentally, you see why I dismissed Grommetik just now. It’s still very sensitive and suspects, I believe, that Ama Clutch thought it responsible for the Goat’s slaughter.”

Glinda said waveringly, “Madame Morrible, you should know that Ama Clutch had never suffered such a disease as I described to you. I invented it. But I didn’t assign it. I didn’t commit it to her, or her to it.”

Elphaba looked at Madame Morrible steadily, keeping her interest modest. Nessarose’s eyelashes fluttered. If Madame Morrible knew Glinda’s news already, her face didn’t give her away. She looked as placid as a tethered rowboat. “Well, this only lends weight to my observations,” she allowed. “There is an imaginative, even a prophetic power in your pointed little society skull, Miss Glinda.”

The Head stood, her skirts rustling, wind through a field of wheat. “What I say now I say in strictest confidence. I expect my girls to obey my command. Are we agreed?” She seemed to take their stunned silence as assent. She looked down on them. That’s why she seems so like a fish, Glinda suddenly thought. She hardly ever blinks.

“By an authority vested in me that is too high to be named, I have been charged with a crucial task,” said the Head. “A task essential to the internal security of Oz. I have been working to fulfill this task for some years, and the time is right, and the goods are at my disposal.” She scrutinized them. They were the goods.

“You will not repeat what you hear in this room,” she said. “You will not want to, you will not choose to, and you will not be able to. I am wrapping each one of you in a binding cocoon as regards this very sensitive material. No”—she held up a hand at Elphaba’s protest—“no you have no right to object. The deed is already done and you must listen and be open to what I say.”

Glinda tried to examine herself to see if she felt wrapped, or bound, or spell-chilled. But she only felt frightened and young, which may be close to the same thing. She glanced at the sisters. Nessarose in her dazzling shoes was back in her chair, nostrils dilating in fright or excitement. Elphaba on the other hand looked as stolid and cross as usual.

“You live in a little womb here, a tight little nest, girl with girl. Oh I know you have your silly boys on the edge, forgettable things. Good for one thing only and not even reliable at that. But I digress. I must say that you know little or nothing of the state of the nation today. You have no sense of the pitch of unrest to which things have mounted. Setting communities on edge, ethnic groups against one another, bankers against farmers and factories against shopkeepers. Oz is a seething volcano threatening to erupt and burn us in its own poisonous pus.

“Our Wizard seems strong enough. Ah, but is he? Is he really? He has a grasp of internal politics. He’s no slouch at negotiating rates of exchange with the bloodsuckers of Ev or Jemmicoe or Fliaan. He rules the Emerald City with an industry and an ability that the decaying knob-jawed Ozma line never dreamed of. Without him we’d have been swept away in firestorm, years ago. We can but be grateful. A strong fist does wonders in a rotten situation. Walk softly but carry a bit stick. I see I offend. Well, a man is always good for the public face of power, no?

“Yes. But things are not always as they seem. And it has been clear for some time that the Wizard’s bag of tricks would not do forever. There are bound to be popular uprisings—the stupid, senseless kind, in which strong dumb people enjoy getting killed for the sake of political changes that’ll be rolled back within the decade. Adds such meaning to meaningless lives, don’t you think? One can’t imagine any other reason for it. At any rate, the Wizard needs some agents. He requires a few generals. In the long run. Some people with managing skills. Some people with gumption.

“In a word, women.

“I have called you three girls in here. You are not women yet, but the moment is closing in on you, faster than you might think. Despite my opinion as to your behavior, I have had to single you out. There is more in each one of you than meets the eye. Miss Nessarose, being the newest, you are the most hidden to me, but once you outgrow that fetching habit of faith you will display a ferocious authority. Your bodily disorder is of no significance here. Miss Elphaba, you are an isolate, and even in my binding spell you sit there stewing in scorn of every word I say. This is evidence of great internal power and force of will, something I deeply respect even when marshaled against me. You have shown no sign of interest in sorcery and I don’t claim you have any natural aptitude. But your splendid lone-wolf spit and spirit can be harnessed, oh yes it can, and you needn’t live a life of unfulfilled rage. And Miss Glinda: You have surprised yourself with the talents at sorcery you possess. I knew you would. I had hoped your inclinations might rub off on Miss Elphaba, but that they haven’t is only firmer proof of Miss Elphaba’s iron character.

“I see in your eyes you all question my methods. You think, somewhat wildly: Did Horrible Morrible cause that nail to pierce my Ama Clutch’s foot, making me have to room with Elphaba? Did she cause Ama Clutch to come downstairs and find the dead Goat, the better to get her out of the way and require Nanny and thus Nessarose to show up on the scene? How flattering that you even imagine I have such power.”

The Head paused and came near to blushing, which in her was something like the separating of cream on a flame set too high. “I am a handmaiden at the service of superiors,” she continued, “and my special talent is to encourage talent. In my own small way I have been called to a vocation of education, and here I make my little contributions to history.

“Now to be specific. I want you to consider your futures. I would like to name you, to baptize you as it were, as a trio of Adepts. In the long run I would like to assign you behind-the-scenes ministerial duties in different parts of the country. I am empowered to do this, remember, by those whose boot straps I am not worthy to lick.” But she looked smug, as if she thought herself quite worthy enough, indeed, of attention from these mysterious forces. “Let us say you will be secret partners of the highest level of government. You will be anonymous ambassadors of peace, helping to restrain the unruly element among our less civilized populations. Nothing is decided yet, of course, and you do have a say in the matter—a say to me, and not to each other nor anyone else, as the spell goes—but I would like you to think about it. I need—eventually—to place an Adept in Gillikin somewhere. Miss Glinda, with your middle-range social position and your transparent ambitions, you can slime your way into ballrooms of margreaves and still be at home in the pigsties. Oh, don’t squirm so, your good blood is only on one side and it’s not a terribly refined strain anyway. The Adept of Gillikin, Miss Glinda? Does it appeal?”

Glinda could only listen. “Miss Elphaba,” said Madame Morrible, “full of the teenage scorn of inherited position, you are nonetheless the Thropp Third Descending, and your great-grandfather, the Eminent Thropp, is in his dotage. One day you will inherit what is left of Colwen Grounds, that pretentious pile in Nest Hardings, and you could manage to be the Adept of Munchkinland. Your unfortunate skin condition notwithstanding—indeed, perhaps because of it—you have developed a feistiness and an iconoclasm that is just faintly appealing when it doesn’t nauseate. It will come in service. Believe me.

“And Miss Nessarose,” she went on, “having grown up in Quadling Country, you will want to return there with Nanny. The social situation in Quadling Country is such a mess, what with the decimation of the squelchy froglet population, but it may come back, in small measure, and there should be someone to oversee the ruby mines. We need someone to look after things in the South. Once you recover from your religious mania, it’ll be a perfect setting. You don’t expect a life of high society anyway, not without arms. After all, how can one dance without arms?

“As for the Vinkus, we don’t imagine we’ll need an Adept stationed there, at least not in your lifetimes. The master plans eradicate any appreciable population in that godforsaken place.”

Here the Head paused and looked around. “Oh, girls. I know you are young. I know this grieves you. You mustn’t think of it as a prison sentence, though, but an opportunity. You ask yourselves: How will I grow in a position, albeit a silent one, of prominence and responsibility? How may my talents flourish? How, my dears, how may I help my Oz?”

Elphaba’s foot twisted, caught the edge of a side table, and a cup and saucer fell to the floor and smashed.

“You’re so predictable,” said Madame Morrible, sighing. “That’s what makes my job so easy. Now girls, bound as you are to an oath of silence, I bid you to go away and think on what I have said. Please don’t even try to discuss it together as it’ll just give you a headache and cramps. You won’t be able to manage it. Sometime in the next semester I will call each of you in here and you can give me your answer. And if you should choose not to help your country in its hour of need . . .” She clasped her hands in a parody of despair. “Well, you are not the only fish in the sea, are you?”

The afternoon had turned glowery, with heaps of plum-colored clouds in the north, beyond the bluestone spires and steeples. The temperature had dropped twenty degrees since the morning, and the girls kept their shawls pulled close as they walked to the pub. Nanny, shivering in the dirty wind, cried, “And what did the old busybody have to say that I couldn’t be allowed to hear?”

But there was nothing they could say. Glinda couldn’t even meet the others’ eyes. “We’ll lift a glass of champagne for Ama Clutch,” said Elphaba finally, “when we get to the Peach and Kidneys.”

“I’d settle for a spoonful of real cream,” said Nanny. “How pinching that old sow is. No respect for the dead.”

But Glinda found that the binding spell was deeper, cut closer than she had even understood. It wasn’t merely that they couldn’t talk about it. Already she had begun—to lose the words about it, to falter in her thinking, to fail to commit the interview to memory. There was the proposal. It was a proposal, wasn’t it? Of some questionable proposition in (was it) the civil service? Doing some—some ballroom dancing, which didn’t make sense. Some laughing, a glass of champagne, a handsome man taking off his cummerbund and pressing his starched cuffs against her neck, nibbling the teardrop-shaped rubies at her ears . . . Talk softly but carry a bit stick. Or was it not a proposal but a prophecy? A little friendly encouragement about the future? And she had been alone, the others hadn’t been listening. Madame Morrible had spoken directly to her. A lovely testimony to Glinda’s . . . potential. The chance to rise. Walk softly but marry a big prick. A man draping his evening tie on a bedstead and rolling his diamond studs, nudging them with his nose, down the declivity of her superior neck . . . It was a dream, Madame Morrible couldn’t have said that! She must be dazed with grief. Poor Ama Clutch. It had only been a quiet word of condolence from the dear and self-effacing Head, who found it hard to speak in public. But a man’s tongue between her legs, a spoonful of saffron cream . . .

Nessarose said, “Catch her, I can’t, I’m—” and she sagged against Nanny’s bosom, and Glinda swooned at the same moment. Elphaba thrust out strong arms and scooped Glinda in mid-collapse. Glinda didn’t really lose consciousness, but the uncomfortable physical nearness of hawk-faced Elphaba after that undesired act of desire made her want to shiver with revulsion and to purr at the same time. “Steady on, girl, not here,” said Elphaba, “resist, come on!” Resist was just what Glinda didn’t want to do. But after all, in the shadow of an apple cart, on the edge of the market where merchants were selling the last fish of the day, cheap, well, this was hardly the place. “Tough, tough skin,” said Elphaba, appearing to pull words from the back of her throat. “Come on, Glinda—you’ve got better brains—come on! I love you too much, snap out of it, you idiot!”

“Well, really,” she said as Elphaba dumped her on a heap of moldy packing straw. “No need to be so romantic about it!” But she felt better, as if a wave of illness had just passed.

“You girls, I tell you, the faints, it comes from those tight shoes,” said Nanny, huffing and loosening Nessarose’s glamorous footwear. “Sensible folk wear leather or wood.” She massaged Nessarose’s insteps for a minute, and Nessarose moaned and arched her back, but began in a few moments to breathe more normally.

“Welcome back to Oz,” said Nanny after a while. “What goodies were you all snacking on, in there with the Head?”

“Come on, they’re waiting,” said Elphaba. “No sense dawdling. Anyway, I’m afraid it might rain.”

At the Peach and Kidneys, the rest of the gang had commandeered a table in an alcove several steps above the main floor. They were well into their cups by that point in the afternoon, and it was clear tears had been shed. Avaric sat slouched against the brick wall of the student den, one arm slung around Fiyero and his legs stretched out in Shenshen’s lap. Boq and Crope were arguing about something, anything, and Tibbett was singing an interminable song to Pfannee, who looked as if she wanted to drive a dart into the thick of his thigh. “Ahh, the ladies,” slurred Avaric, and made as if to rise.

They sang, and chattered, and ordered sandwiches, and Avaric plunked down an embarrassment of coins to demand a salver of saffron cream, in Ama Clutch’s memory. Money did wonders and the cream was found in the larder, which gave Glinda an uneasy feeling, though she didn’t know why. They spooned the airy mounds into one another’s mouths, sculpted with it, mixed it in their champagne, threw it in small gobbets at one another until the manager came over and told them to get the hell out. They complied, grumbling. They didn’t know it was the last time they would all be together, or they might have lingered.

A brisk rain had come and gone, but the streets were still noisy with runoff, and the lamplight glistened and danced in the silvery black curvetts of water caught among the cobbles. Imagining the possible brigand in the shadows, or the hungry wanderer lurking nearby, they stood close together. “I’ve got an idea,” said Avaric, putting one foot this way and the other that, as if he were as flexible as a man of straw. “Who’s man enough for the Philosophy Club tonight?”

“Oh, no you don’t,” said Nanny, who hadn’t had that much to drink.

“I want to go,” whined Nessarose, swaying more than usual.

“You don’t even know what it is,” said Boq, giggling and hiccuping.

“I don’t care, I don’t want to leave tonight,” Nessarose said. “We only have one another and I don’t want to be left out, and I don’t want to go home!”

“Hush Nessa, hush hush, my pretty,” said Elphaba. “That’s not the place for you, or me either. Come on, we’re going home. Glinda, come on.”

“I have no Ama now,” said wide-eyed Glinda, stabbing a finger toward Elphaba. “I am my own agent. I want to go to the Philosophy Club and see if it’s true.”

“The rest can do what they want but we’re going home,” said Elphaba.

Glinda veered over toward Elphaba, who was homing in on a very uncertain-looking Boq. “Now Boq, you don’t want to go to that disgusting place, do you?” Elphaba was saying. “Come on, don’t let the boys make you do something you don’t want.”

“You don’t know me,” he said, appearing to address the hitching post. “Elphie, how do you know what I want? Unless I find out? Hmmm?”

“Come with us,” said Fiyero to Elphaba. “Please, if we ask you politely?”

“I want to go too,” whined Glinda.

“Oh, come, Glinny-dinny,” said Boq, “maybe they’ll pick us. For old times’ sake, as never was.”

The others had awakened a slumbering cab driver and hired his services. “Boq, Glinda, Elphie, come on,” Avaric called from the window. “Where’s your nerve?”

“Boq, think about this,” Elphaba urged.

“I always think, I never feel, I never live,” he moaned. “Can’t I live once in a while? Just once? Just because I’m short I’m not an infant, Elphie!”

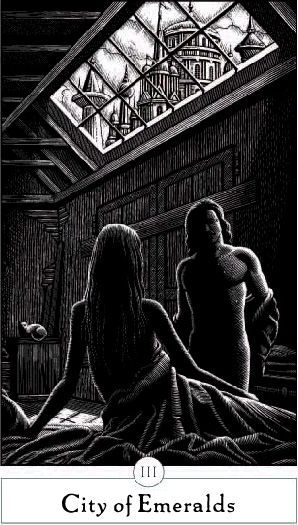

“Not till now,” said Elphaba. Rather smarmy tonight, thought Glinda, and wrenched herself away to climb into the cab. But Elphaba grabbed her by the elbow and pivoted her around. “You can’t,” she whispered. “We’re going to the Emerald City.”

“I’m going to the Philosophy Club with my friends—”

“Tonight,” hissed Elphaba. “You little idiot, we have no time to waste on sex!”

Nanny had led Nessarose away already, and the cabbie clucked his reins and the equipage lumbered away. Glinda stumbled and said, “What did you think you were just about to say? To say?”

“I already said it and I’m not saying it again,” said Elphaba. “My dear, you and I are going back to Crage Hall tonight only to pack a valise. Then we’re away.”

“But the gates’ll be locked—”

“It’s over the garden wall,” said Elphaba, “and we’re going to see the Wizard, come what may and hell to pay.”

7

Boq could not believe he was heading to the Philosophy Club at last. He hoped he wouldn’t vomit at a crucial moment. He hoped he would remember the whole thing tomorrow, or at least some kernel of it, despite the headache forming vengefully in the hollows at his temples.

The place was discreet, though it was the best known dive in Shiz. It hid behind a facade of paneled-up windows. A couple of Apes roamed the street in front, bouncing troublemakers ahead of time. Avaric counted the party carefully as they fell from the cab. “Shenshen, Crope, me, Boq, Tibbett, Fiyero, and Pfannee. Seven. Boy how’d we all fit in the cab, could hardly fit us I’d think.” He paid the cabbie and tipped him, in some obscure homage still to Ama Clutch, and then pushed to the front of the silent knot of companions. “Come on, we’re the right age and the right drunk,” he said, and to the shadowed face at the window, “Seven. Seven of us, good sir.”