4

4

Well, if I was in disgrace, I was also in good health, and that’s what matters. I might have been one of the three thousand dead, or of the shattered wounded lying shrieking through the dusk along that awful line of bluffs. There seemed to be no medical provision—among the British, anyway—and scores of our folk just lay writhing where they fell, or died in the arms of mates hauling and carrying them down to the beach hospitals. The Russian wounded lay in piles by the hundred round our bivouacs, crying and moaning all through the night—I can hear their sobbing “Pajalsta! pajalsta!” still. The camp ground was littered with spent shot and rubbish and broken gear among the pools of congealed blood—my stars, wouldn’t I just like to take one of our Ministers, or street-corner orators, or blood-lusting, breakfast-scoffing papas, over such a place as the Alma hills—not to let him see, because he’d just tut-tut and look anguished and have a good pray and not care a damn—but to shoot him in the belly with a soft-nosed bullet and let him die screaming where he belonged. That’s all they deserve.

Not that I cared a fig for dead or wounded that night. I had worries enough on my own account, for in brooding about the injustice of Raglan’s reproaches, I convinced myself that I’d be broke in the end. The loss of that mealy little German pimp swelled out of all proportion in my imagination, with the Queen calling me a murderer and Albert accusing me of high treason, and The Times trumpeting for my impeachment. It was only when I realized that the army might have other things to think about that I cheered up.

I was feeling as lonely as the policeman at Herne Bay14 when I loafed into Billy Russell’s tent, and found him scribbling away by a storm lantern, with Lew Nolan perched on an ammunition box, holding forth as usual.

“Two brigades of cavalry!” Nolan was saying. “Two brigades, enough to have pursued and routed the whole pack of ’em! And what do they do? Sit on their backsides, because Lucan’s too damned scared to order a bag of oats without a written order from Raglan. Lord Lucan? Bah! Lord bloody Look-on, more like.”

“Hm’m,” says Billy, writing away, and glanced up. “Here, Flash—you’ll know. Were the Highlanders first into the redoubt? I say yes, but Lew says not.15 Stevens ain’t sure, and I can’t find Campbell anywhere. What d’ye say?”

I said I didn’t know, and Nolan cried what the devil did it matter, anyway, they were only infantry. Billy, seeing he would get no peace from him, threw down his pen, yawned, and says to me:

“You look well used up, Flash. Are you all right? What’s the matter, old fellow?”

I told him Willy was lost, and he said aye, that was a pity, a nice lad, and I told him what Raglan had said to me, and at this Nolan forgot his horses for a minute, and burst out:

“By God, isn’t that of a piece? He’s lost the best part of five brigades, and he rounds on one unfortunate galloper because some silly little ass who shouldn’t have been here at all, at all, gets himself blown up by the Russians! If he was so blasted concerned for him, what did he let him near the field for in the first place? And if you was to wet-nurse him, why did he have you galloping your arse off all day? The man’s a fool! Aye, and a bad general, what’s worse—there’s a Russian army clear away, thanks to him and those idle Frogs, and we could have cut ’em to bits on this very spot! I tell you, Billy, this fellow’ll have to go.”

“Come, Lew, he’s won his fight,” says Russell, stroking his beard. “It’s too bad he’s set on you, Flash—but I’d lose no sleep over it. Depend upon it, he’s only voicing his own fears of what may be said to him—but he’s a decent old stick, and bears no grudges. He’ll have forgotten about it in a day or so.”

“You think so?” says I, brightening.

“I should hope so!” cries Nolan. “Mother of God, if he hasn’t more to think about, he should have. Here’s him and Lucan between ’em have let a great chance slip, but by the time Billy here has finished tellin’ the British public about how the matchless Guards and stern Caledonians swept the Muscovite horde aside on their bayonet points—”

“I like that,” says Billy, winking at me. “I like it, Lew; go on, you’re inspiring.”

“Ah, bah, the old fool’ll be thinking he’s another Wellington,” says Lew. “Aye, you can laugh, Russell—tell your readers what I’ve said about Lucan, though—I dare ye! That’d startle ’em!”

This talk cheered me up, for after all, it was what Russell thought—and wrote—that counted, and he never even mentioned Willy’s death in his despatches to The Times. I heard that Raglan later referred to it, at a meeting with his generals, and Cardigan, the dirty swine, said privately that he wondered why the Prince’s safety had been entrusted to a common galloper. But Lucan took the other side, and said only a fool would blame me for the death of another staff officer, and de Lacy Evans said Raglan should think himself lucky it was Willy he had lost and not me. Sound chaps, some of those generals.

And Nolan was right—Raglan and everyone else had enough to occupy them, after the Alma. The clever men were for driving on hard to Sevastopol, a bare twenty miles away, and with our cavalry in good fettle we could obviously have taken it. But the Frogs were too tired, or too sick, or too Froggy, if you ask me, and days were wasted, and the Ruskis managed to bolt the door in time.

What was worse, the carnage at Alma, and the cholera, had thinned the army horribly, there was no proper transport, and by the time we had lumbered on to Sevastopol peninsula we couldn’t have robbed a hen-roost. But the siege had to be laid, and Raglan, looking wearier all the time, was thrashing himself to be cheerful and enthusiastic, with his army wasting, and winter coming, and the Frogs groaning at him. Oh, he was brave and determined and ready to take on all the odds—the worst kind of general imaginable. Give me a clever coward every time (which, of course, is why I’m such a dam’ fine general myself).

So the siege was laid, the French and ourselves sitting down on the muddy, rain-sodden gullied plateau before Sevastopol, the dismalest place on earth, with no proper quarters but a few poor huts and tents, and everything to be carted up from Balaclava on the coast eight miles away. Soon the camp, and the road to it, was a stinking quagmire; everyone looked and felt filthy, the rations were poor, the work of preparing the siege was cruel hard (for the men, anyway), and all the bounce there had been in the army after Alma evaporated in the dank, feverish rain by day and the biting cold by night. Soon half of us were lousy, and the other half had fever or dysentery or cholera or all three—as some wag said, who’d holiday at Brighton if he could come to sunny Sevastopol instead?

I didn’t take any part in the siege operations myself, not because I was out of favour with Raglan, but for the excellent reason that like so many of the army I spent several weeks on the flat of my back with what was thought at first to be cholera, but was in fact a foul case of dysentery and wind, brought on by my own hoggish excesses. On the march south after the Alma I had been galloping a message from Airey to our advance guard, and had come on a bunch of our cavalry who had bushwacked a Russian baggage train and were busily looting it.16 Like a good officer, I joined in, and bagged as much champagne as I could carry, and a couple of fur cloaks as well. The cloaks were splendid, but the champagne must have carried the germ of the Siberian pox or something, for within a day I was blown up like a sheep on weeds, and spewing and skittering damnably. They sent me down to a seedy little house in Balaclava, not far from where Billy Russell was established, and there I lay sweating and rumbling, and wishing I were dead. Part of it I don’t remember, so I suppose I must have been delirious, but my orderly looked after me well, and since I still had all the late Willy’s gear and provisions—not that I ate much, until the last week—I did tolerably well. Better at least than any other sick man in the army; they were being carted down to Balaclava in droves, rotten with cholera and fever, lying in the streets as often as not.

Lew Nolan came down to see me when I was mending, and gave me all the gossip—about how my old friend Fan Duberly was on hand, living on a ship in the bay, and how Cardigan’s yacht had arrived, and his noble lordship, pleading a weak chest, had deserted his Light Brigade for the comforts of life aboard, where he slept soft and stuffed his guts with the best. There were rumours, too, Lew told me, of Russian troops moving up in huge strength from the east, and he thought that if Raglan didn’t look alive, he’d find himself bottled up in the Sevastopol peninsula. But most of Lew’s talk was a great harangue against Lucan and Cardigan; to him, they were the clowns who had mishandled our cavalry so damnably and were preventing it earning the laurels which Lew thought it deserved. He was a dead bore on the subject, but I’ll not say he was wrong—we were both to find out all about that shortly.

For now, although I couldn’t guess it, as I lay pampering myself with a little preserved jellied chicken and Rhine wine—of which Willy’s store-chest yielded a fine abundance—that terrible day was approaching, that awful thunderclap of a day when the world turned upside down in a welter of powder-smoke and cannon-shot and steel, which no one who lived through it will ever forget. Myself least of all. I never thought that anything could make Alma or the Kabul retreat seem like a charabanc picnic, but that day did, and I was through it, dawn to dusk, as no other man was. It was sheer bad luck that it was the very day I returned to duty. Damn that Russian champagne; if it had kept me in bed just one day longer, what I’d have been spared. Mind you, we’d have lost India, for what that’s worth.

I had been up a day or two, riding a little up to the Balaclava Plain, and wondering if I was fit enough to look up Fan Duberly, and take up again the attempted seduction which had been so maddeningly frustrated in Wiltshire six years before. She’d ripened nicely, by what Lew said, and I hadn’t bestrode anything but a saddle since I’d left England—even the Turks didn’t fancy the Crim Tartar women, and anyway, I’d been ill. But I’d convalesced as long as I dared, and old Colin Campbell, who commanded in Balaclava, had dropped me a sour hint that I ought to be back with Raglan in the main camp up on the plateau. So on the evening of October 24 I got my orderly to assemble my gear, left Willy’s provisions with Russell, and loafed up to headquarters.

Whether I’d exerted myself too quickly, or it was the sound of the Russian bands in Sevastopol, playing their hellish doleful music, that kept me awake, I was taken damned ill in the night. My bowels were in a fearful state, I was blown out like a boiler, and I was unwise enough to treat myself with brandy, on the principle that if your guts are bad they won’t feel any worse for your being foxed. They do, though, and when my orderly suddenly tumbled me out before dawn, I felt as though I were about to give birth. I told him to go to the devil, but he insisted that Raglan wanted me, p.d.q., so I huddled into my clothes in the cold, shivering and rumbling, and went to see what was up.

They were in a great sweat at Raglan’s post; word had come from Lucan’s cavalry that our advanced posts were signalling enemy in sight to the eastward, and gallopers were being sent off in all directions, with Raglan dictating messages over his shoulder while he and Airey pored over their maps.

“My dear Flashman,” says Raglan, when his eye lit on me, “why, you look positively unwell. I think you would be better in your berth.” He was all benevolent concern this morning—which was like him, of course. “Don’t you think he looks ill, Airey?” Airey agreed that I did, but muttered something about needing every staff rider we could muster, so Raglan tut-tutted and said he much regretted it, but he had a message for Campbell at Balaclava, and it would be a great kindness if I would bear it. (He really did talk like that, most of the time; consideration fairly oozed out of him.) I wondered if I should plead my belly, so to speak, but finding him in such a good mood, with the Willy business apparently forgotten, I gave him my brave, suffering smile, and pocketed his message, fool that I was.

I felt damned shaky as I hauled myself into the saddle, and resolved to take my time over the broken country that lay between headquarters and Balaclava. Indeed, I had to stop several times, and try to vomit, but it was no go, and I cantered on over the filthy road with its litter of old stretchers and broken equipment, until I came out on to the open ground some time after sunrise.

After the downpour of the night before, it was dawning into a beautiful clear morning, the kind of day when, if your innards aren’t heaving and squeaking, you feel like a fine gallop with the wind in your face. Before me the Balaclava Plain rolled away like a great grey-green blanket, and as I halted to have another unsuccessful retch, the scene that met my eyes was like a galloping field day. On the left of the plain, where it sloped up to the long line of the Causeway Heights, our cavalry were deployed in full strength, more than a thousand horsemen, like so many brilliant little puppets in the sunny distance, trotting in their squadrons, wheeling and reforming. About a mile away, nearest to me, I could easily distinguish the Light Brigade—the pink trousers of the Cherrypickers, the scarlet of Light Dragoons, and the blue tunics and twinkling lance-points of the 17th. The trumpets were tootling on the breeze, the words of command drifted across to me as clear as a bell, and even beyond the Lights I could see, closer in under the Causeway, and retiring slowly in my direction, the squadrons of the Heavy Brigade—the grey horses with their scarlet riders, the dark green of the Skins, and the hundreds of tiny glittering slivers of the sabres. It was for all the world like a green nursery carpet, with tiny toy soldiers deployed upon it, and as pretty as these pictures of reviews and parades that you see in the galleries.

Until you looked beyond, to where Causeway Heights faded into the haze of the eastern dawn, and you could see why our cavalry were retiring. The far slopes were black with scurrying ant-like figures—Russian infantry pouring up to the gun redoubts which we had established along the three miles of the Causeway; the thunder of cannon rolled continuously across the plain, the flashes of the Russian guns stabbing away at the redoubts, and the sparkle of their muskets was all along the far end of the Causeway. They were swarming over the gun emplacements, engulfing our Turkish gunners, and their artillery was pounding away towards our retreating cavalry, pushing it along under the shadow of the Heights.

I took all this in, and looked off across the plain to my right, where it sloped up into a crest protecting the Balaclava road. Along the crest there was a long line of scarlet figures, with dark green blobs where their legs should be—Campbell’s Highlanders, at a safe distance, thank God, from the Russian guns, which were now ranging nicely on the Heavy Brigade under the Heights. I could see the shot plumping just short of the horses, and hear the urgent bark of commands: a troop of the Skins scattered as a great column of earth leaped up among them, and then they reformed, trotting back under the lee of the Causeway.

Well, there was a mile of empty, unscathed plain between me and the Highlanders, so I galloped down towards them, keeping a wary eye on the distant artillery skirmish to my left. But before I’d got halfway to the crest I came on their outlying picket breakfasting round a fire in a little hollow, and who should I see but little Fanny Duberly, presiding over a frying-pan with half a dozen grinning Highlanders round her. She squealed at the sight of me, waving and shoving her pan aside; I swung down out of my saddle, bad belly and all, and would have embraced her, but she caught my hands at arms’ length. And then it was Harry and Fanny, and where have you sprung from, and all that nonsense and chatter, while she laughed and I beamed at her. She had grown prettier, I think, with her fair hair and blue eyes, and looking damned fetching in her neat riding habit. I longed to give her tits a squeeze, but couldn’t, with all those leering Highlanders nudging each other.

She had ridden up, she said, with Henry, her husband, who was in attendance on Lord Raglan, although I hadn’t seen him.

“Will there be a great battle to-day, Harry?” says she. “I am so glad Henry will be safely out of it, if there is. See yonder”—and she pointed across the plain towards the Heights—“where the Russians are coming. Is it not exciting? Why do the cavalry not charge them, Harry? Are you going to join them? Oh, I hope you will take care! Have you had any breakfast? My dear, you look so tired. Come and sit down, and share some of our haggis!”

If anything could have made me sick, it would have been that, but I explained that I hadn’t time to tattle, but must find Campbell. I promised to see her again, as soon as the present business was by, and advised her to clear off down to Balaclava as fast as she could go—it was astonishing, really, to see her picnicking there, as fresh as a May morning, and not much more than a mile away the Russian forces pounding away round the redoubts, and doubtless ready to sweep right ahead over the plain when they had regrouped.

The sergeant of Highlanders said Campbell was somewhere off with the Heavy Brigade, which was bad news, since it meant I must approach the firing, but there was nothing for it, so I galloped off north again, through the extended deployment of the Lights, who were now sitting at rest, watching the Heavies reforming. George Paget hailed me; he was sitting with one ankle cocked up on his saddle, puffing his cheroot, as usual.

“Have you come from Raglan?” cries he. “Where the hell are the infantry, do you know? We shall be sadly mauled at this rate, unless he moves soon. Look at the Heavies yonder; why don’t Lucan shift ’em back faster, out of harm’s way?” And indeed they were retiring slowly, it seemed to me, right under the shadow of the Heights, with the Russian fire still kicking up the clods round them as they came. I ventured forward a little way: I could see Lucan, and his staff, but no sign of Campbell, so I asked Morris, of the 17th, and he said Campbell had gone back across the plain, towards Balaclava, a few minutes since.

Well, that was better, since it would take me down to the Highlanders’ position, away from where the firing was. And yet, it suddenly seemed very secure in my present situation, with the blue tunics and lances of the 17th all round me, and the familiar stench of horse-flesh and leather, and the bits jingling and the fellows patting their horses’ necks and muttering to steady them against the rumble of the guns; there were troop horse artillery close by, banging back at the Russians, but it was still rather like a field day, with the plain all unmarked, and the uniforms bright and gay in the sunlight. I didn’t want to leave ’em—but there were the Highlanders drawn up near the crest across the plain southward: I must just deliver my message as quickly as might be, and then be off back to head-quarters.

So I turned my back to the Heights, and set off again through the ranks of the 17th and the Cherrypickers, and was halfway down the plain to the Highlanders on the crest when here came a little knot of riders moving up towards the cavalry. And who should it be but my bold Lord Cardigan, with Squire Brough and his other toadies, all in great spirits after a fine comfortable boozy night on his yacht, no doubt.

I hadn’t seen the man face to face since that night in Elspeth’s bedroom, and my bile rose up even at the thought of the bastard, so I cut him dead. When Brough hailed me, and asked what was the news I reined up, not even looking in Cardigan’s direction, and told Brough the Ruskis were over-running the far end of the Heights, and our horse were falling back.

“Ya-as,” says Cardigan to his toadies, “it is the usual foolishness. There are the Wussians, so our cavalry move in the other diwection. Haw-haw. You, there, Fwashman, what does Word Waglan pwopose to do?”

I continued to ignore him. “Well, Squire,” says I to Brough, “I must be off; can’t stand gossiping with yachtsmen, you know,” and I wheeled away, leaving them gaping, and an indignant “Haw-haw” sounding behind me.

But I hadn’t time to feel too satisfied, for in that moment there was a new thunderous cannonade from the Russians, much closer now; the whistle of shot sounded overhead, there was a great babble of shouting and orders from the cavalry behind me, the calls of the Lights and Heavies sounded, and the whole mass of our horse began to move off westward, retiring again. The cannonading grew, as the Russians turned their guns southward, I saw columns of earth ploughed up to the east of the Highlanders’ position, and with my heart in my mouth I buried my head in the horse’s mane and fairly flew across the turf. The shot was still falling short, thank God, but as I reached the crest a ball came skipping and rolling almost up to my horse’s hooves, and lay there, black and smoking, as I tore up to the Highlanders’ flank.

“Where is Sir Colin?” cries I, dismounting, and they pointed to where he was pacing down between the ranks in my direction. I went forward, and delivered my message.

“Oot o’ date,” says he, when he had read it. “Ye don’t look weel, Flashman. Bide a minute. I’ve a note here for Lord Raglan.” And he turned to one of his officers, but at that moment the shouting across the plain redoubled, there was the thunderous plumping of shot falling just beyond the Highland position, and Campbell paused to look across the plain towards the Causeway Heights.

“Aye,” says he, “there it is.”

I looked towards the Heights, and my heart came up into my throat.

Our cavalry was now away to the left, at the Sevastopol end of the plain, but on the Heights to the right, near the captured redoubts, the whole ridge seemed to have come alive. Even as we watched, the movement resolved itself into a great mass of cavalry—Russian cavalry, wheeling silently down the side of the Heights in our direction. They’ve told me since that there were only four squadrons, but they looked more like four brigades, blue uniforms and grey, with their sabres out, preparing to descend the long slope from the Heights that ran down towards our position.

It was plain as a pikestaff what they were after, and if I could have sprouted wings in that moment I’d have been fluttering towards the sea like a damned gull. Directly behind us the road to Balaclava lay open; our own cavalry were out of the hunt, too far off to the left; there was nothing between that horde of Russians and the Balaclava base—the supply line of the whole British army—but Campbell’s few hundred Highlanders, a rabble of Turks on our flank, and Flashy, full of wind and horror.

Campbell stared for a moment, that granite face of his set; then he pulled at his dreary moustache and roared an order. The ranks opened and moved and closed again, and now across our ridge there was a double line of Highlanders, perhaps a furlong from end to end, kneeling down a yard or so on the seaward side of the crest. Campbell looked along them from our stance at the right-hand extremity of the line, bidding the officers dress them. While they were doing it, there was a tremendous caterwauling from the distant flank, and there were the Turks, all order gone, breaking away from their positions in the face of the impending Russian charge, flinging down their arms and tearing headlong for the sea road behind us.

“Dross,” says Campbell.

I was watching the Turks, and suddenly, to their rear, riding towards us, and then checking and wheeling away southward, I recognized the fair hair and riding fig of Fanny Duberly. She was flying along as she passed our far flank, going like a little jockey—she could ride, that girl.

“Damn all society women,” says Campbell. And it occurred to me, even through the misery of my stomach and my rising fear, that Balaclava Plain that morning was more like the Row—Fanny Duberly out riding, and Cardigan ambling about haw-hawing.

I looked towards the Russians; they were rumbling down the slope now, a bare half-mile away; Campbell shouted again, and the long scarlet double rank moved foward a few paces, with a great swishing of their kilts and clatter of gear, and halted on the crest, the front rank kneeling and the second standing behind them. Campbell glanced across at the advancing mass of the Russian horse, measuring the distance.

“Ninety-third!” he shouted. “There is no retreat from here! Ye must stand!”

He had no need to tell me; I couldn’t have moved if I had wanted to. I could only gape at that wall of horsemen, galloping now, and then back at the two frail, scarlet lines that in a moment must be swept away into bloody rabble with the hooves smashing down on them and the sabres swinging; it was the finish, I knew, and nothing to do but wait trembling for it to happen. I found myself staring at the nearest kneeling Highlander, a huge, swarthy fellow with his teeth bared under a black moustache; I remember noticing the hair matting the back of his right hand as it gripped his musket. Beyond him there was a boy, gazing at the advancing squadrons with his mouth open; his lip was trembling.

“Haud yer fire until I give the wurr-rd!” says Campbell, and then quite deliberately he stepped a little out before the front rank and drew his broadsword, laying the great glittering blade across his chest. Christ, I thought, that’s a futile thing to do—the ground was trembling under our feet now, and the great quadruple rank of horsemen was a bare two hundred yards away, sweeping down at the charge, sabres gleaming, yelling and shouting as they bore down on us, a sea of flaring horse heads and bearded faces above them.

“Present!” shouts Campbell, and moved past me in behind the front rank. He stopped behind the boy with the trembling lip. “Ye never saw the like o’ that comin’ doon the Gallowgate,” says he. “Steady now, Ninety-third! Wait for my command!”

They were a hundred yards away now, that thundering tide of men and horses, the hooves crashing like artillery on the turf. The double bank of muskets with their fixed bayonets covered them; the locks were back, the fingers hanging on the triggers; Campbell was smiling sourly beneath his moustache, the madman; he glanced to his left along the silent lines—give the word, damn you, you damned old fool, I wanted to shout, for they were a bare fifty yards off, in a split second they would be into us, he had left it too late—

“Fire!” he bellowed, and like one huge bark of thunder the front-rank volley crashed out, the smoke billowed back in our faces, and beyond it the foremost horsemen seemed to surge up in a great wave; there was a split-second of screaming confusion, with beasts plunging and rearing, a hideous chorus of yells from the riders, and the great line crashed down on the turf before us, the men behind careering into the fallen horses and riders, trying to jump them or pull clear, trampling them, hurtling over them in a smashing tangle of limbs and bodies.

“Fire!” roars Campbell above the din, and the pieces of the standing rank crashed together into the press; it seemed to shudder at the impact, and behind it the Russian ranks wheeled and stumbled in confusion, men screaming and going down, horses lashing out blindly, sabres gleaming and flying. As the smoke cleared there was a great tangled bloody bank of stricken men and beasts wallowing within a few yards of the kneeling Highlanders—they’ll tell you, some of our historians, that Campbell fired before they reached close range, but here’s one who can testify that one Russian, with a fur-crested helmet and pale blue tunic rolled right to within a foot of us; the swarthy Highlander nearest me didn’t have to advance a step to plunge his bayonet into the Russian’s body.

A great yell went up from the Ninety-third; the front rank seemed to leap forward, but Campbell was before them, bawling them back. “Damn your eagerness!” cries he. “Stand fast! Reload!”

They dropped back, snarling like dogs, and Campbell turned and calmly surveyed the wreckage of the Russian ranks. There were beasts thrashing about everywhere and men crawling blindly away, the din of screaming and groaning was fearful, and a great reek that you could literally see was steaming up from them. Behind, the greater part of the Russian squadrons was turning, reforming, and for a moment I thought they were coming again, but they moved off back towards the Heights, closing their ranks as they went.

“Good,” says Campbell, and his sword grated back into its scabbard.

“Ye niver saw a sight like that goin’ back up the Gallowgate, Sir Colin,” pipes a voice from somewhere, and they began to laugh and cheer, and yell their heathenish slogans, shaking their muskets, and Campbell grinned and pulled at his moustache again. He saw me—I hadn’t stirred a yard since the charge began, I’d been so petrified—and walked across.

“I’ll add a line to my message for Lord Raglan,” says he, and looks at me. “Ye’ve mair colour in yer cheeks now, Flashman. Field exercises wi’ the Ninety-third must agree wi’ ye.”

And so, with those kilted devils still holding their ranks, and the Russians dying and moaning before them, I waited while he dictated his message to one of his aides. Now that the terror was past, my belly was aching horribly and I felt thoroughly ill again, but not so ill that I wasn’t able to note (and admire) the carriage of the retreating Russian cavalry. In charging, I had noticed how they had opened their ranks at the canter and then closed them at the gallop, which isn’t easy; now they were doing the same thing as they retired towards the heights, and I thought, these fellows ain’t so slovenly as we thought. I remember thinking they’d perhaps startle Jim the Bear and his Light Brigade—but most of all, from that moment of aftermath, I can still see vividly that tangled pile of Russian dead, and sprawled out before them the body of an officer, a big grey-bearded man with the front of his blue tunic soaked in blood, lying on his back with one knee bent up, and his horse standing above him, nuzzling at the dead face.

Campbell put a folded paper into my hand and stood, shading his eyes with a hand under his bonnet-rim, as he watched the Russian horse canter up the Causeway Heights.

“Poor management,” says he. “They’ll no’ come this way again. In the meantime, I’ve said to Lord Raglan that in my opeenion the main Russian advance will now be directed north of the Causeway, and will doubtless be wi’ artillery and horse against our cavalry. What it is doin’ sittin’ yonder, I cannae—but, hollo! Is that Scarlett movin’? Hand me that glass, Cattenach. See yonder.”

The Russian cavalry were now topping the Causeway ridge, vanishing from our view, but on the plain farther left, perhaps half a mile from us, there was movement in the ranks of our Heavy Brigade: a sudden uniform twinkle of metal as the squadrons nearest to us turned.

“They’re coming this way,” says someone, and Campbell snapped his glass shut.

“Behind the fair,” says he, glumly—I never saw him impatient yet. Where other men would get angry and swear, Campbell simply got more melancholy. “Flashman—on your way to Lord Raglan, I’ll be obliged if you’ll present my compliments to General Scarlett, or Lord Lucan, whichever comes first in your road, and tell them that in my opeenion they’ll do well to hold the ground they have, and prepare for acteevity on the northern flank. Away wi’ ye, sir.”

I needed no urging. The farther I could get from that plain, the better I’d be suited, for I was certain Campbell was right. Having captured the eastern end of the Causeway Heights, and run their cavalry over the central ridge facing us, it was beyond doubt that the Russians would be moving up the valley north of the Heights, advancing on the plateau position which we occupied before Sevastopol. God knew what Raglan proposed to do about that, but in the meantime he was holding our cavalry on the southern plain—to no good purpose. They hadn’t budged an inch to take the retreating Russian cavalry in flank, as they might have done, and now, after the need for their support had passed, the Heavies were moving down slowly towards Campbell’s position.

I rode through their ranks—Dragoon Guards and a few Skins, riding in open order, eyeing me curiously as I galloped through—“That’s Flashman, ain’t it?” cries someone, but I didn’t pause. Ahead of me I could see the little knot of coloured figures, red and blue, of Scarlett and his staff; as I reined up, they were cheering and laughing, and old Scarlett waved his hat to me.

“Ho-ho, Flashman!” cries he. “Were you down there with the Sawnies? Capital work, what? That’s a bloody nose for Ivan, I say. Ain’t it, though, Elliot? Dam’ fine, dam’ fine! And where are you off to, Flashman, my son?”

“Message to Lord Raglan, sir,” says I. “But Sir Colin Campbell also presents his compliments, and advises that you should move no nearer to Balaclava at present.”

“Does he, though? Beatson, halt the Dragoons, will you? Now then, why not? Lord Lucan has ordered us to support the Turks, you know, in case of Russian movement towards Balaclava.”

“Sir Colin expects no further movement there, sir. He bids you look to your northern flank,” and I pointed to the Causeway Heights, only a few hundred yards away. “Anyway, sir, there are no longer any Turks to support. Most of ’em are probably on the beach by now.”

“That’s true, bigod!” Scarlett exploded in laughter. He was a fat, cheery old Falstaff, mopping his bald head with a hideously-coloured scarf, and then dabbing the sweat from his red cheeks. “What d’ye think, Elliot? No point in goin’ down to Campbell that I can see; he and his red-shanks don’t need support, that’s certain.”

“True, sir. But there is no sign of Russian movement to our north, as yet.”

“No,” said Scarlett, “that’s so. But I trust Campbell’s judgment, ye know; clever fella. If he smells Ruskis to our north, beyond the Heights, well, I dunno. I trust an old hound any day, what?” He sniffed and mopped himself again, tugging at his puffy white whiskers. “Tell you what, Elliot, I think we’ll just hold on here, and see what breaks cover, hey? What d’ye say to that, Beatson? Flashman? No harm in waitin’, is there?”

He could dig trenches for all I cared; I was already measuring the remaining distance across the plain westward; once in the gullies I’d be out of harm’s way, and could pick my way to Raglan’s head-quarters at my leisure. North of us, the ground sloping up to the heights through an old vineyard was empty; so was the crest beyond, but the thump of cannon from behind it seemed to be growing closer to my nervous imagination. There was an incessant whine and thump of shot; Beatson was scanning the ridge anxiously through his glass.

“Campbell’s right, sir,” says he. “They must be up there in the north valley in strength.”

“How d’ye know?” says Scarlett, goggling.

“The firing, sir. Listen to it—that’s not just cannon. There—you hear? That’s Whistling Dick! If they have mortars with ’em, they’re not skirmishing!”

“By God!” says Scarlett. “Well I’m damned! I can’t tell one from another, but if you say so, Beatson, I—”

“Look yonder!” It was one of his young gallopers, up in his stirrups with excitement, pointing. “The ridge, sir! Look at ’em come!”

We looked, and for the second time that day I forgot my gurgling aching belly in a freezing wave of fear. Slowly topping the crest, in a great wave of colour and dancing steel, was a long rank of Russian horsemen, and behind them another, and then another, moving at a walk. They came over the ridge as if they were in review, extended line after extended line, and then slowly closed up, halting on the near slope of the ridge, looking down at us. God knows how far their line ran from flank to flank, but there were thousands of them, hanging over us like an ocean roller frozen in the act of breaking, a huge body of blue and silver hussars on the left, and to the right the grey and white of their dragoons.

“By God!” cries Scarlett. “By God! Those are Russians—damn ’em!”

“Left about!” Beatson was yelling. “Greys, stand fast! Cunningham, close ’em up! Inniskillings—close order! Connor, Flynn, keep ’em there! Curzon, get those squadrons of the Fifth up here, lively now!”

Scarlett was sitting gaping at the ridge, damning his eyes and the Russians alternately until Beatson jerked at his sleeve.

“Sir! We must prepare to receive them! When they take the brake off they’ll roll down—”

“Receive ’em?” says Scarlett, coming back to earth. “What’s that, Beatson? Damned if I do!” He reared up in his stirrups, glaring along to the left, where the Greys’ advanced squadrons were being dressed to face the Russian force. “What? What? Connor, what are you about there?” He was gesticulating to the right now, waving his hat. “Keep your damned Irishmen steady there! Wild devils, those! Where’s Curzon, hey?”

“Sir, they have the slope of us!” Beatson was gripping Scarlett by the sleeve, rattling urgently in his ear. “They outflank us, too—I reckon that line’s three times the length of ours, and when they charge they can sweep round and take us flank, both sides, and front! They’ll swallow us, sir, if we break—we must try to holdfast!”

“Hold fast nothin’!” says Scarlett, grinning all over his great red cheeks. “I didn’t come all this way to have some dam’ Cossack open the ball! Look at ’em, there, the saucy bastards! What? What? Well, they’re there, and we’re here, and I’m goin’ to chase the scoundrels all the way to Moscow! What, Elliot? Here, you, Flashman, come to my side, sir!”

You may gather my emotions at hearing this; I won’t attempt to describe them. I stared at this purpling old lunatic in bewilderment, and tried to say something about my message to Raglan, but the impetuous buffoon grabbed at my bridle and hauled me along as he took post in front of his squadrons.

“You shall tell Lord Raglan presently that I have engaged a force of enemy cavalry on my front an’ dispersed ’em!” bawls he. “Beatson, Elliot, see those lines dressed! Where are the Royals, hey? Steady, there, Greys! Steady now! Inniskillings, look to that dressing, Flynn! Keep close to me, Flashman, d’ye hear? Like enough I’ll have somethin’ to add to his lordship. Where the devil’s Curzon, then? Damn the boy, if it’s not women it’s somethin’ else! Trumpeter, where are you? Come to my left side! Got your tootler, have you? Capital, splendid!”

It was unbelievable, this roaring fat old man, waving his hat like some buffer at a cricket match, while Beatson tried to shout sense into him.

“You cannot move from here, sir! It is all uphill! We must hold our ground—there’s no other hope!” He pointed up hill frantically. “Look, they’re moving sir! We must hold fast!”

And sure enough, up on the heights a quarter of a mile away, the great Russian line was beginning to advance, shoulder to shoulder, blue and silver and grey, with their sabres at the present; it was a sight to send you squealing for cover, but there I was, trapped at this idiot’s elbow, with the squadrons of the Greys hemming us in behind.

“You cannot advance, sir!” shouts Beatson again.

“Can’t I, by God!” roars Scarlett, throwing away his hat. “You just watch me!” He lugged out his sabre and waved it. “Ready, Greys? Ready, old Skins? Remember Waterloo, you fellas, what? Trumpeter—sound the…the thing, whatever it is! Oh, the devil! Come on, Flashman! Tally-ho!”

And he dug in his heels, gave one final yell of “Come on, you fellas!” and set his horse at the hill like a madman. There was a huge, crashing shout from behind, the squadrons leaped forward, my horse reared, and I found myself galloping along, almost up Scarlett’s dock, with Beatson at my elbow shouting, “Oh, what the blazes—charge! Trumpeter, charge! charge! charge!”

They were all stark, raving mad, of course. When I think of them—and me, God help me—tearing up that hill, and that overwhelming force lurching down towards us, gathering speed with every step, I realize that there’s no end to human folly, or human luck, either. It was ridiculous, it was nonsense, that old red-faced pantaloon, who’d never fired a shot or swung a sabre in action before, and was fit for nothing but whipping off hounds, urging his charger up that hill, with the whole Heavy Brigade at his heels, and poor old suffering Flashy jammed in between, with nothing to do but hope to God that by the time the two irresistible forces met, I’d be somewhere back in the mob behind.

And the brutes were enjoying it, too! Those crazy Ulstermen were whooping like Apaches, and the Greys, as they thundered forward, began to make that hideous droning noise deep in their throats; I let them come up on my flanks, their front rank hemming me in with glaring faces and glittering blades on either side; Scarlett was yards ahead, brandishing his sabre and shouting, the Russian mass was at the gallop, sweeping towards us like a great blue wave, and then in an instant we were surging into them, men yelling, horses screaming, steel clashing all round, and I was clinging like a limpet to my horse’s right side, Cheyenne fashion, left hand in the mane and right clutching my Adams revolver. I wasn’t breaking surface in that melee if I could help it. There were Greys all round me, yelling and cursing, slashing with their sabres at the hairy blue coats—“Give ’em the point! The point!” yelled a voice, and I saw a Greys trooper dashing the hilt of his sword into a bearded face and then driving his point into the falling man’s body. I let fly at a Russian in the press, and the shot took him in the neck, I think; then I was dashed aside and swept away in the whirl of fighting, keeping my head ducked low, squeezing my trigger whenever I saw a blue or grey tunic, and praying feverishly that no chance slash would sweep me from the saddle.

I suppose it lasted five or ten minutes; I don’t know. It seemed only a few seconds, and then the whole mass was struggling up the hill, myself roaring and blaspheming with the best of them; my revolver was empty, my hat was gone, so I dragged out my sabre, bawling with pretended fury, and seeing nothing but grey horses, gathered that I was safe.

“Come on!” I roared. “Come on! Into the bastards! Cut ’em to bits!” I made my horse rear and waved my sword, and as a stricken Russian came blundering through the mob I lunged at him, full force, missed, and finished up skewering a fallen horse. The wrench nearly took me out of my saddle, but I wasn’t letting that sabre go, not for anything, and as I tugged it free there was a tremendous cheering set up—“Huzza! huzza! huzza”—and suddenly there were no Russians among us, Scarlett, twenty yards away, was standing in his stirrups waving a blood-stained sabre and yelling his head off, the Greys were shaking their hats and their fists, and the rout of that great mass of enemy cavalry was trailing away towards the crest.

“They’re beat!” cries Scarlett. “They’re beat! Well done, you fellas! What, Beatson? Hey, Elliot? Can’t charge uphill, hey? Damn ’em, damn ’em, we did it! Hurrah!”

Now it is a solemn fact, but I’ll swear I didn’t see above a dozen corpses on the ground around me as the Greys reordered their squadrons, and the Skins closed in on the right, with the Royals coming up behind. I still don’t understand it—why the Russians, with the hill behind ’em, didn’t sweep us all away, with great slaughter. Or why, breaking as they did, they weren’t cut to pieces by our sabres. Except that I remember one or two of the Greys complaining that they hadn’t been able to make their cuts tell; they just bounced off the Russian tunics. Anyway, the Ruskis broke, thank heaven, and away beneath us, to our left, the Light Brigade were setting up a tremendous cheer, and it was echoing along the ridge to our left, and on the greater heights beyond.

“Well done!” shouts Scarlett. “Well done, you Greys! Well done, Flashman, you are a gallant fellow! What? Hey? That’ll show that damned Nicholas, what? Now then, Flashman, off with you to Lord Raglan—tell him we’ve…well, set about these chaps and driven ’em off, you see, and that I shall hold my position, what, until further orders. You understand? Capital!” He shook with laughter, and hauled out his coloured scarf for another mop at his streaming face. “Tell ye what, Flashman; I don’t know much about fightin’, but it strikes me that this Russian business is like huntin’ in Ireland—confused and primitive, what, but damned interestin’!”

I reported his words to Raglan, exactly as he spoke them, and the whole staff laughed with delight, the idiots. Of course, they were safe enough, snug on the top of the Sapoune Ridge, which lay at the western end of Causeway Heights, and I promise you I had taken my time getting there. I’d ridden like hell on my spent horse from the Causeway, across the north-west corner of the plain, when Scarlett dismissed me, but once into the safety of the gullies, with the noise of Russian gunfire safely in the distance, I had dismounted to get my breath, quiet my trembling heartstrings, and try to ease my wind-gripped bowels, again without success. I was a pretty bedraggled figure, I suppose, by the time I came to the top of Sapoune, but at least I had a bloody sabre, artlessly displayed—Lew Nolan’s eyes narrowed and he swore enviously at the sight: he wasn’t to know it had come from a dead Russian horse.

Raglan was beaming, as well he might be, and demanded details of the action I had seen. So I gave ’em, fairly offhand, saying I thought the Highlanders had behaved pretty well—“Yes, and if we had just followed up with cavalry we might have regained the whole Causeway by now!” pipes Nolan, at which Airey told him to be silent, and Raglan looked fairly stuffy. As for the Heavies—well, they had seen all that, but I said it had been warm work, and Ivan had got his bellyful, from what I could see.

“Gad, Flashy, you have all the luck!” cries Lew, slapping his thigh, and Raglan clapped me on the shoulder.

“Well done, Flashman,” says he. “Two actions today, and you have been in the thick of both. I fear you have been neglecting your staff duties in your eagerness to be at the enemy, eh?” And he gave me his quizzical beam, the old fool. “Well, we shall say no more about that.”

I looked confused, and went red, and muttered something about not being able to abide these damned Ruskis, and they all laughed again, and said that was old Flashy, and the young gallopers, the pink-cheeked lads, looked at me with awe. If it hadn’t been for my aching belly, I’d have been ready to enjoy myself, now that the horror of the morning was past, and the cold sweat of reaction hadn’t had a chance to set in. I’d come through again, I told myself—twice, no less, and with new laurels. For although we were too close to events just then to know what would be said later—well, how many chaps have you heard of who stood with the Thin Red Line and took part in the Charge of the Heavy Brigade? None, ‘cos I’m the only one, damned unwilling and full of shakes, but still, I’ve dined out on it for years. That—and the other thing that was to follow.

But in the meantime, I was just thanking my stars for safety, and rubbing my inflamed guts. (Someone said later that Flashman was more anxious about his bowels than he was about the Russians, and had taken part in all the charges to try to ease his wind.) I sat there with the staff, gulping and massaging, happy to be out of the battle, and taking a quiet interest while Lord Raglan and his team of idiots continued to direct the fortunes of the day.

Now, of that morning at Balaclava I’ve told you what I remember, as faithfully as I can, and if it doesn’t tally with what you read elsewhere, I can’t help it. Maybe I’m wrong, or maybe the military historians are: you must make your own choice. For example, I’ve read since that there were Turks on both flanks of Campbell’s Highlanders, whereas I remember ’em only on the left flank; again, my impression of the Heavy Brigade action is that it began and ended in a flash, but I gather it must have taken Scarlett some little time to turn and dress his squadrons. I don’t remember that. It’s certain that Lucan was on hand when the charge began, and I’ve been told he actually gave the word to advance—well, I never even saw him. So there you are; it just shows that no one can see everything.17

I mention this because, while my impressions of the early morning are fairly vague, and consist of a series of coloured and horrid pictures, I’m in no doubt about what took place in the late forenoon. That is etched forever; I can shut my eyes and see it all, and feel the griping pain ebbing and clawing at my guts—perhaps that sharpened my senses, who knows? Anyway, I have it all clear; not only what happened, but what caused it to happen. I know, better than anyone else who ever lived, why the Light Brigade was launched on its famous charge, because I was the man responsible, and it wasn’t wholly an accident. That’s not to say I’m to blame—if blame there is, it belongs to Raglan, the kind, honourable, vain old man. Not to Lucan, or to Cardigan, or to Nolan, or to Airey, or even to my humble self: we just played our little parts. But blame? I can’t even hold it against Raglan, not now. Of course, your historians and critics and hypocrites are full of virtuous zeal to find out who was “at fault”, and wag their heads and say “Ah, you see,” and tell him what should have been done, from the safety of their studies and lecture-rooms—but I was there, you see, and while I could have wrung Raglan’s neck, or blown him from the muzzle of a gun, at the time—well, it’s all by now, and we either survived it or we didn’t. Proving someone guilty won’t bring the six hundred to life again—most of ’em would be dead by now anyway. And they wouldn’t blame anyone. What did that trooper of the 17th say afterwards: “We’re ready to go in again.” Good luck to him, I say; once was enough for me—but, don’t you understand, nobody else has the right to talk of blame, or blunders? Just us, the living and the dead. It was our indaba. Mind you, I could kick Raglan’s arse for him, and my own.

I sat up there on the Sapoune crest, feeling bloody sick and tired, refusing the sandwiches that Billy Russell offered me, and listening to Lew Nolan’s muttered tirade about the misconduct of the battle so far. I hadn’t much patience with him—he hadn’t been risking his neck along with Campbell and Scarlett, although he no doubt wished he had—but in my shaken state I wasn’t ready to argue. Anyway, he was fulminating against Lucan and Cardigan and Raglan mostly, which was all right by me.

“If Cardigan had taken in the Lights, when the Heavies were breaking up the Ruskis, we’d have smashed ’em all by this,” says he. “But he wouldn’t budge, damn him—he’s as bad as Lucan. Won’t budge without orders, delivered in the proper form, with nice salutes, and ‘Yes, m’lord’ an’ ‘if your lordship pleases’. Christ—cavalry leaders! Cromwell’d turn in his grave, bad cess to him. And look at Raglan yonder—does he know what to do? He’d got two brigades o’ the best horsemen in Europe, itchin’ to use their sabres, an’ in front of ’em a Russian army that’s shakin’ in its boots after the maulin’ Campbell an’ Scarlett have given ’em—but he sits there sendin’ messages to the infantry! The infantry, bigod, that’re still gettin’ out of their beds somewhere. Jaysus, it makes me sick!”

He was in a fine taking, but I didn’t mind him much. At the same time, looking down on the panorama beneath us, I could see there was something in what he said. I’m not Hannibal, but I’ve picked up a wrinkle or two in my time, about ground and movement, and it looked to me as though Raglan had it in his grasp to do the Russians some no-good, and maybe even hand them a splendid licking, if he felt like it. Not that I cared, you understand; I’d had enough, and was all for a quiet life for everybody. But anyway, this is how the land lay.

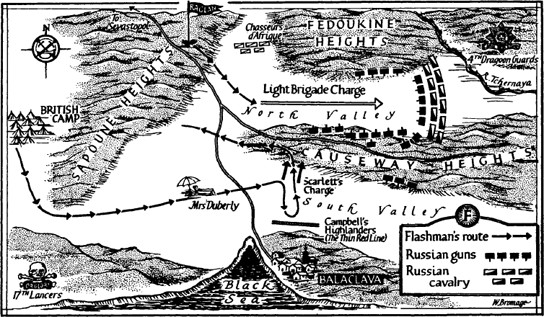

The Sapoune, on which we stood, is a great bluff rising hundreds of feet above the plain. Looking east from it, you see below you a shallow valley, perhaps two miles long and half a mile broad; to the north, there is a little clump of heights on which the Russians had established guns to command that side of the valley. On the south the valley is bounded by the long spine of the Causeway Heights, running east from the Sapoune for two or three miles. The far end of the valley was fairly hazy, even with the strong sunlight, but you could see the Russians there as thick as fleas on a dog’s back—guns, infantry, cavalry, everything except Tsar Nick himself, tiny puppets in the distance, just holding their ground. They had guns on the Causeway, too, pointing north; as I watched I saw the nearest team of them unlimbering just beside the spot where the Heavies’ charge had ended.

So there it was, plain as a pool table—a fine empty valley with the main force of the Russians at the far end of it, and us at the near end, but with Ruskis on the heights to either side, guns and sharpshooters both—you could see the grey uniforms of their infantry moving among their cannon down on the Causeway, not a mile and a half away.

Directly beneath where I stood, at the near end of the valley, our cavalry had taken up station just north of the Causeway, the Heavies slightly nearer the Sapoune and to the right, the Lights just ahead of them and slightly left. They looked as though you could have lobbed a stone into the middle of them—I could easily make out Cardigan, threading his way behind the ranks of the 17th, and Lucan with his gallopers, and old Scarlett, with his bright scarf thrown over one shoulder of his coat—they were all sitting out there waiting, tiny figures in blue and scarlet and green, with here and there a plumed hat, and an occasional bandage: I noticed one trooper of the Skins binding a stocking on to the forefoot of his charger, the little dark-green figure crouched down at the horse’s hooves. The distant pipe of voices drifted up from the plain, and from the far end of the Causeway a popping of musketry; for the rest it was all calm and still, and it was this tranquillity that was driving Lew to a frenzy, the bloodthirsty young imbecile.

Well, thinks I, there they all are, doing nothing and taking no harm; let ’em be, and let’s go home. For it was plain to see the Ruskis were going to make no advance up the valley towards the Sapoune; they’d had their fill for the day, and were content to hold the far end of the valley and the heights either side. But Raglan and Airey were forever turning their glasses on the Causeway, at the Russian artillery and infantry moving among the redoubts they’d captured from the Turks; I gathered both our infantry and cavalry down in the plain should have been moving to push them out, but nothing was happening, and Raglan was getting the frets.

“Why does not Lord Lucan move?” I heard him say once, and again: “He has the order; what delays him now?” Knowing Look-on, I could guess he was huffing and puffing and laying the blame on someone else. Raglan kept sending gallopers down—Lew among them—to tell Lucan, and the infantry commanders, to get on with it, but they seemed maddeningly obtuse about his orders, and wanted to wait for our infantry to come up, and it was this delay that was fretting Raglan and sending Lew half-crazy.

“Why doesn’t Raglan make ’em move, dammit?” says he, coming over to Billy Russell and me after reporting back to Raglan. “It’s too bad! If he would give ’em one clear simple command, to push in an’ sweep those fellows off the Causeway—oh, my God! An’ he won’t listen to me—I’m a young pup green behind the ears. The cavalry alone could do it in five minutes—it’s about time Cardigan earned his general’s pay, anyway!”

I approved heartily of that, myself. Every time I heard Cardigan’s name mentioned, or saw his hateful boozy vulture face, I remembered that vile scene in Elspeth’s bedroom, and felt my fury boiling up. Several times it had occurred to me on the campaign that it would be a capital thing if he could be induced into action where he might well be hit between the legs and so have his brains blown out, but he’d not looked like taking a scratch so far. And there seemed scant chance of it today; I heard Raglan snapping his glass shut with impatience, and saying to Airey: “I despair almost of moving our horse. It looks as though we shall have to rely on Cambridge alone—whenever his infantry come up! Oh, this is vexing! We shall accomplish nothing against the Causeway positions at this rate!”

And just at that moment someone sang out: “My lord! See there—the guns are moving! The guns in the second redoubt—the Cossacks are getting them out!”

Sure enough, there were Russian horsemen limbering up away down the Causeway crest, tugging at a little toy cannon in the captured Turkish emplacement. They had tackles on it, and were obviously intent on carrying it off to the main Russian army. Raglan stared at it through his glass, his face working.

“Airey!” cries he. “This is intolerable! What is Lucan thinking of—why, these fellows will clear the guns away before our advance begins!”

“He is waiting for Cambridge, I suppose, my lord,” says Airey, and Raglan swore, for once, and continued to gaze fretfully down on the Causeway.

Lew was writhing with impatience in his saddle. “Oh, Christ!” he moaned softly. “Send in Cardigan, man—never mind the bloody infantry. Send in the Lights!”

Good idea, thinks I—let Jim the Bear skirmish into the redoubts, and get a Cossack lance where it’ll do most good. So you may say it was out of pure malice towards Cardigan that I piped up—taking care that my back was to Raglan, but talking loud enough for him to hear:

“There goes our record—Wellington never lost a gun, you know.”

I’ve heard since, from a galloper who was at Raglan’s side, that it was those words, invoking the comparison with his God Wellington, that stung him into action—that he started like a man shot, that his face worked, and he jerked at his bridle convulsively. Maybe he’d have made up his mind without my help—but I’ll be honest and say that I doubt it. He’d have waited for the infantry. As it was he went pale and then red, and snapped out:

“Airey—another message to Lord Lucan! We can delay no longer—he must move without the infantry. Tell him—ah, he is to advance the cavalry rapidly to the front, to prevent the enemy carrying off the guns—ah, to follow the enemy and prevent them. Yes. Yes. He may take troop horse artillery, at his discretion. There—that will do. You have it, Airey? Read it back, if you please.”

I see it so clearly still—Airey’s head bent over the paper, jabbing at the words with his pencil, as he read back (more or less in Raglan’s words, certainly in the same sense), Nolan’s face alight with joy beside me—“At last, at last, thank God!” he was muttering—and Raglan sitting, nodding carefully. Then he cried out: “Good. It is to be acted on at once—make that clear!”

“Ah, that’s me darlin’!” whispers Lew, and nudged me. “Well done, Flashy, me boy—you’ve got him movin’!”

“Send it immediately,” Raglan was telling Airey. “Oh, and notify Lord Lucan that there are French cavalry on his left. Surely that should suffice.” And he opened his glass again, looking down at Causeway Heights. “Send the fastest galloper.”

I had a moment’s apprehension at that—having started the ball, I’d no wish to be involved—but Raglan added: “Where is Nolan?—yes, Nolan,” and Lew, beside himself with excitement, wheeled his horse beside Airey, grabbed at the paper, tucked it in his gauntlet, smacked down his forage cap, threw Raglan the fastest of salutes, and would have been off like a shot, but Raglan stayed him, repeating that the message was of the utmost importance, that it was to be delivered with all haste to Lucan personally, and that it was vital to act at once, before the Ruskis could make off with our guns.18 All unnecessary repetition of course, and Lew was in a fever, going pink with impatience.

“Away, then!” cries Raglan at last, and Lew was over the brow in a twinkling, with a flurry of dust—showy devil—and Raglan shouting after him: “At once, Nolan—tell Lord Lucan at once, you understand.”

That’s how they sent Nolan off—that and no more, on my oath. And so I come to the point with which I began this memoir, with Raglan having a second thought, and shouting to Airey to send after him, and Airey looking round, and myself retiring modestly, you remember, and Airey spotting me and gesturing me violently up beside him.

Well, you know what I thought, of the unreasoning premonition that I had, that this would be the ultimate terror of that memorable day in which I had, much against my will, already been charged at by, and charged against, overwhelming hordes of Russians. There was nothing, really, to be agitated about, up there on the heights—I was merely to be sent after Nolan, with some addition or correction. But I felt the finger of doom on me, I don’t know why, as I scrambled aboard a fresh horse with Raglan and Airey clamouring at me.

“Flashman,” says Raglan, “Nolan must make it clear to Lord Lucan—he is to behave defensively, and attempt nothing against his better judgment. Do you understand me?”

Well, I understood the words, but what the hell Lucan was expected to make of them, I couldn’t see. Told to advance, to attack the enemy, and yet to act defensively. But it was nothing to me; I repeated the order, word for word, making sure Airey could hear me, and then went over the bluff after Lew.

It was as steep as hell’s half acre, like a seaside sandcliff shot across by grassy ridges. At any other time I’d have picked my way down nice and leisurely, but with Raglan and the rest looking down, and in full view of our cavalry in the plain, I’d no choice but to go hell-for-leather. Besides, I wasn’t going to let that cocky little pimp Nolan distance me—I may not be proud of much, but I fancied myself against any galloper in the army, and was determined to overtake him before he reached Lucan. So down I went, with the game little mare under me skipping like a mountain goat, sliding on her haunches, careering headlong, and myself clinging on with my knees aching and my hands on the mane, jolting and swaying wildly, and in the tail of my eye Lew’s red cap jerking crazily on the escarpment below.

I was the better horseman. He wasn’t twenty yards out on the level when I touched the bottom and went after him like a bolt, yelling to him to hold on. He heard me, and reined up, cursing, and demanding to know what was the matter. “On with you!” cries I, as I came alongside, and as we galloped I shouted my message.

He couldn’t make it out, but had to pluck the note from his glove and squint at it while he rode. “What the hell does it mean in the first place?” cries he. “It says here, ‘advance rapidly to the front’. Well, God love us, the guns ain’t in front; they’re in flank front if they’re anywhere.”

“Search me,” I shouted. “But he says Look-on is to act defensively, and undertake nothing against his better judgment. So there!”

“Defensive?” cries Lew. “Defensive be damned! He must have said offensive—how the hell could he attack defensively? And this order says nothin’ about Lucan’s better judgment. For one thing, he’s got no more judgment than Mulligan’s bull pup!”

“Well, that’s what Raglan said!” I shouted. “You’re bound to deliver it.”

“Ah, damn them all, what a set of old women!” He dug in his spurs, head down, shouting across to me as we raced towards the rear squadrons of the Heavies. “They don’t know their minds from one minute to the next. I tell ye, Flash, that ould ninny Raglan will hinder the cavalry at all costs—an’ Lucan’s not a whit better. What do they think horse-soldiers are for? Well, Lucan shall have his order, and be damned to them!”

I eased up as we shot through the ranks of the Greys, letting him go ahead; he went streaking through the Heavies, and across the intervening space towards the Lights. I’d no wish to be dragged into the discussion that would inevitably ensue with Lucan, who had to have every order explained to him three times at least. But I supposed I ought to be on hand, so I cantered easily up to the 4th Lights, and there was George Paget again, wanting to know what was up.

“You’re advancing shortly,” says I, and “Damned high time, too,” says he. “Got a cheroot, Flash?—I haven’t a weed to my name.”

I gave him one, and he squinted at me. “You’re looking peaky,” says he. “Anything wrong?”

“Bowels,” says I. “Damn all Russian champagne. Where’s Lord Look-on?”

He pointed, and I saw Lucan out ahead of the Lights, with some galloper beside him, and Nolan just reining up. Lew was saluting, and handing him the paper, and while Lucan pored over it I looked about me.

It was drowsy and close down here on the plain after the breezy heights of the Sapoune; hardly a breath of wind, and the flies buzzing round the horses’ heads, and the heavy smell of dung and leather. I suddenly realized I was damned tired, and my belly wouldn’t lie quiet again; I grunted in reply to George’s questions, and took stock of the Brigade, squirming uncomfortably in my saddle—there were the Cherrypickers in front, all very spruce in blue and pink with their pelisses trailing; to their right the mortarboard helmets and blue tunics of the 17th, with their lances at rest and the little red point plumes hanging limp; to their right again, not far from where Lucan was sitting, the 13th Lights, with the great Lord Cardigan himself out to the fore, sitting very aloof and alone and affecting not to notice Lucan and Nolan, who weren’t above twenty yards from him.

Suddenly I was aware of Lucan’s voice raised, and trotted away from George in that direction; it looked as though Lew would need some help in getting the message into his lordship’s thick skull. I saw Lucan look in my direction, and just at that moment, as I was passing the 17th, someone called out:

“Hollo, there’s old Flashy! Now we’ll see some fun! What’s the row, Flash?”

This sort of thing happens when one is generally admired; I replied with a nonchalant wave of the hand, and sang out: “Tally-ho, you fellows! You’ll have all the fun you want presently,” at which they laughed, and I saw Tubby Morris grinning across at me.

And then I heard Lucan’s voice, clear as a bugle. “Guns, sir? What guns, may I ask? I can see no guns.”

He was looking up the valley, his hand shading his eyes, and when I looked, by God, you couldn’t see the redoubt where the Ruskis had been limbering up to haul the guns away—just the long slope of Causeway Heights, and the Russian infantry uncomfortably close.

“Where, sir?” cries Lucan. “What guns do you mean?”

I could see Lew’s face working; he was scarlet with fury, and his hand was shaking as he came up by Lucan’s shoulder, pointing along the line of the Causeway.

“There, my lord—there, you see, are the guns! There’s your enemy!”

He brayed it out, as though he was addressing a dirty trooper, and Lucan stiffened as though he’d been hit. He looked as though he would lose his temper, but then he commanded himself, and Lew wheeled abruptly away and cantered off, making straight for me where I was sitting to the right of the 17th. He was shaking with passion, and as he drew abreast of me he rasped out:

“The bloody fool! Does he want to sit on his great fat arse all day and every day?”

“Lew,” says I, pretty sharp, “did you tell him he was to act defensively and at his own discretion?”

“Tell him?” says he, baring his teeth in a savage grin. “By Christ, I told him three times over! As if that bastard needs telling to act defensively—he’s capable of nothing else! Well, he’s got his bloody orders—now let’s see how he carries them out!”

And with that he went over to Tubby Morris, and I thought, well, that’s that—now for the Sapoune, home and beauty, and let ’em chase to their hearts content down here. And I was just wheeling my horse, when from behind me I heard Lucan’s voice.

“Colonel Flashman!” He was sitting with Cardigan, before the 13th Lights. “Come over here, if you please!”

Now what, thinks I, and my belly gave a great windy twinge as I trotted over towards them. Lucan was snapping at him impatiently, as I drew alongside:

“I know, I know, but there it is. Lord Raglan’s order is quite positive, and we must obey it.”

“Oh, vewy well,” says Cardigan, damned ill-humoured; his voice was a mere croak, no doubt with his roupy chest, or over-boozing on his yacht. He flicked a glance at me, and looked away, sniffing; Lucan addressed me.

“You will accompany Lord Cardigan,” says he. “In the event that communication is needed, he must have a galloper.”

I stared horrified, hardly taking in Cardigan’s comment: “I envisage no necessity for Colonel Fwashman’s pwesence, or for communication with your lordship.”

“Indeed, sir,” says I, “Lord Raglan will need me…I dare not wait any longer…with your lordship’s permission, I—”

“You will do as I say!” barks Lucan. “Upon my word, I have never met such insolence from mere gallopers before this day! First Nolan, and now you! Do as you are told, sir, and let us have none of this shirking!”

And with that he wheeled away, leaving me terrified, enraged, and baffled. What could I do? I couldn’t disobey—it just wasn’t possible. He had said I must ride with Cardigan, to those damned redoubts, chasing Raglan’s bloody guns—my God, after what I had been through already! In an instant, by pure chance, I’d been snatched from security and thrust into the melting-pot again—it wouldn’t do. I turned to Cardigan—the last man I’d have appealed to, in any circumstances, except an extremity like this.

“My lord,” says I. “This is preposterous—unreasonable! Lord Raglan will need me! Will you speak to his lordship—he must be made to see—”

“If there is one thing,” says Cardigan, in that croaking drawl, “of which I am tolewably certain in this uncertain world, it is the total impossibiwity of making my Word Wucan see anything at all. He makes it cwear, furthermore, that there is no discussion of his orders.” He looked me up and down. “You heard him, sir. Take station behind me, and to my weft. Bewieve me, I do not welcome your pwesence here any more than you do yourself.”

At that moment, up came George Paget, my cheroot clamped between his teeth.

“We are to advance, Lord George,” says Cardigan. “I shall need close support, do you hear?—your vewy best support, Lord George. Haw-haw. You understand me?”

George took the cheroot from his mouth, looked at it, stuck it back, and then said, very stiff: “As always, my lord, you shall have my support.”

“Haw-haw. Vewy well,” says Cardigan, and they turned aside, leaving me stricken, and nicely hoist with my own petard, you’ll agree. Why hadn’t I kept my mouth shut in Raglan’s presence? I could have been safe and comfy up on the Sapoune—but no, I’d had to try to vent my spite, to get Cardigan in the way of a bullet, and the result was I would be facing the bullets alongside him. Oh, a skirmish round gun redoubts is a small enough thing by military standards—unless you happen to be taking part in it, and I reckoned I’d used up two of my nine lives today already. To make matters worse, my stomach was beginning to churn and heave most horribly again; I sat there, with my back to the Light Brigade, nursing it miserably, while behind me the orders rattled out, and the squadrons reformed; I took a glance round and saw the 17th were now directly behind me, two little clumps of lances, with the Cherrypickers in behind. And here came Cardigan, trotting out in front, glancing back at the silent squadrons.

He paused, facing them, and there was no sound now but the restless thump of hooves, and the creak and jingle of the gear. All was still, five regiments of cavalry, looking down the valley, with Flashy out in front, wishing he were dead and suddenly aware that dreadful things were happening under his belt. I moved, gasping gently to myself, stirring on my saddle, and suddenly, without the slightest volition on my part, there was the most crashing discharge of wind, like the report of a mortar. My horse started; Cardigan jumped in his saddle, glaring at me, and from the ranks of the 17th a voice muttered: “Christ, as if Russian artillery wasn’t bad enough!” Someone giggled, and another voice said: “We’ve ’ad Whistlin’ Dick—now we got Trumpetin’ Harry an’ all!”

“Silence!” cries Cardigan, looking like thunder, and the murmur in the ranks died away. And then, God help me, in spite of my straining efforts to contain myself, there was another fearful bang beneath me, echoing off the saddle, and I thought Cardigan would explode with fury.

I could not merely sit there. “I beg your pardon, my lord,” says I, “I am not well—”

“Be silent!” snaps he, and he must have been in a highly nervous condition himself, otherwise he would never have added, in a hoarse whisper:

“Can you not contain yourself, you disgusting fellow?”

“My lord,” whispers I, “I cannot help it—it is the feverish wind, you see—” and I interrupted myself yet again, thunderously. He let out a fearful oath, under his breath, and wheeled his charger, his hand raised; he croaked out “Bwigade will advance—first squadron, 17th—walk-march—twot!” and behind us the squadrons stirred and moved forward, seven hundred cavalry, one of them palsied with fear but in spite of that feeling a mighty relief internally—it was what I had needed all day, of course, like these sheep that stuff themselves on some windy weed, and have to be pierced to get them right again.

And that was how it began. Ahead of me I could see the short turf of the valley turning to plough, and beyond that the haze at the valley end, a mile and more away, and only a few hundred yards off, on either side, the enclosing slopes, with the small figures of Russian infantry clearly visible. You could even see their artillerymen wheeling the guns round, and scurrying among the limbers—we were well within range, but they were watching, waiting to see what we would do next. I forced myself to look straight ahead down the valley; there were guns there in plenty, and squadrons of Cossacks flanking them; their lance points and sabres caught the sun and threw it back in a thousand sudden gleams of light. Would they try a charge when we wheeled right towards the redoubts? Would Cardigan deploy the 4th Lights? Would he put the 17th forward as a screen when we made our flank movement? If I stuck close by him, would I be all right? Oh, God, how had I landed in this fix again—three times in a day? It wasn’t fair—it was unnatural, and then my innards spoke again, resoundingly, and perhaps the Russian gunners heard it, for far down the Causeway on the right a plume of smoke blossomed out as though in reply, there was the crash of the discharge and the shot went screaming overhead, and then from all along the Causeway burst out a positive salvo of firing; there was an orange flash and a huge bang a hundred paces ahead, and a fount of earth was hurled up and came pattering down before us, while behind there was the crash of exploding shells, and a new barrage opening up from the hills on the left.

Suddenly it was, as Lord Tennyson tells us, like the very jaws of hell; I realized that, without noticing, I had started to canter, babbling gently to myself, and in front Cardigan was cantering too, but not as fast as I was (one celebrated account remarks that, “In his eagerness to be first at grips with the foe, Flashman was seen to forge ahead; ah, we can guess the fierce spirit that burned in that manly breast”—I don’t know about that, but I’m here to inform you that it was nothing to the fierce spirit that burned in my manly bowels). There was a crash-crash-crash of flaming bursts across the front, and the scream of shell splinters whistling by; Cardigan shouted “Steady!”, but his own charger was pacing away now, and behind me the clatter and jingle was being drowned by the rising drum of hooves, from a slow canter to a fast one, and then to a slow gallop, and I tried to rein in that little mare, smothering my own panic, and snarling fiercely to myself: “Wheel, wheel, for God’s sake! Why doesn’t the stupid bastard wheel?” For we were level with the first Russian redoubt; their guns were levelled straight at us, not four hundred yards away, the ground ahead was being torn up by shot, and then from behind me there was a frantic shout.

I turned in the saddle, and there was Nolan, his sabre out, charging across behind me, shouting hoarsely, “Wheel, my lord! Not that way! Wheel—to the redoubts!” His voice was all but drowned in the tumult of explosion, and then he was streaking past Cardigan, reining his beast back on its haunches, his face livid as he turned to face the brigade. He flourished his sabre, and shouted again, and a shell seemed to explode dead in front of Cardigan’s horse; for a moment I lost Nolan in the smoke, and then I saw him, face contorted in agony, his tunic torn open and gushing blood from shoulder to waist. He shrieked horribly, and his horse came bounding back towards us, swerving past Cardigan with Lew toppling forward on to the neck of his mount. As I stared back, horrified, I saw him careering into the gap between the Lancers and the 13th Light, and then they had swallowed him, and the squadrons came surging down towards me.

I turned to look for Cardigan; he was thirty yards ahead, tugging like damnation to hold his charger in, with the shot crashing all about him. “Stop!” I screamed. “Stop! For Christ’s sake, man, rein in!” For now I saw what Lew had seen—the fool was never going to wheel, he was taking the Light Brigade straight into the heart of the Russian army, towards those massive batteries at the valley foot, that were already belching at us, while the cannon on either side were raking us from the flanks, trapping us in a terrible enfilade that must smash the whole command to pieces.