19

“It Has Come!”

Of course Dr. Craven had been sent for the

morning after Colin had had his tantrum. He was always sent for at

once when such a thing occurred and he always found, when he

arrived, a white shaken boy lying on his bed, sulky and still so

hysterical that he was ready to break into fresh sobbing at the

least word. In fact, Dr. Craven dreaded and detested the

difficulties of these visits. On this occasion he was away from

Misselthwaite Manor until afternoon.

“How is he?” he asked Mrs. Medlock rather irritably

when he arrived. “He will break a blood-vessel in one of those fits

some day. The boy is half insane with hysteria and

self-indulgence.”

“Well, sir,” answered Mrs. Medlock, “you’ll

scarcely believe your eyes when you see him. That plain sour-faced

child that’s almost as bad as himself has just bewitched him. How

she’s done it there’s no telling. The Lord knows she’s nothing to

look at and you scarcely ever hear her speak, but she did what none

of us dare do. She just flew at him like a little cat last night,

and stamped her feet and ordered him to stop screaming, and somehow

she startled him so that he actually did stop, and this

afternoon-well, just come up and see, sir. It’s past

crediting.”

The scene which Dr. Craven beheld when he entered

his patient’s room was indeed rather astonishing to him. As Mrs.

Medlock opened the door he heard laughing and chattering. Colin was

on his sofa in his dressing-gown and he was sitting up quite

straight looking at a picture in one of the garden books and

talking to the plain child who at that moment could scarcely be

called plain at all because her face was so glowing with

enjoyment.

“Those long spires of blue ones-we’ll have a lot of

those,” Colin was announcing. “They’re called Del-phin-iums.”

“Dickon says they’re larkspurs made big and grand,”

cried Mistress Mary. “There are clumps there already.”

Then they saw Dr. Craven and stopped. Mary became

quite still and Colin looked fretful.

“I am sorry to hear you were ill last night, my

boy,” Dr. Craven said a trifle nervously. He was rather a nervous

man.

“I’m better now-much better,” Colin answered,

rather like a Rajah. “I’m going out in my chair in a day or two if

it is fine. I want some fresh air.”

Dr. Craven sat down by him and felt his pulse and

looked at him curiously.

“It must be a very fine day,” he said, “and you

must be very careful not to tire yourself.”

“Fresh air won’t tire me,” said the young

Rajah.

As there had been occasions when this same young

gentleman had shrieked aloud with rage and had insisted that fresh

air would give him cold and kill him, it is not to be wondered at

that his doctor felt somewhat startled.

“I thought you did not like fresh air,” he

said.

“I don’t when I am by myself,” replied the Rajah;

“but my cousin is going out with me.”

“And the nurse, of course?” suggested Dr.

Craven.

“No, I will not have the nurse,” so magnificently

that Mary could not help remembering how the young native Prince

had looked with his diamonds and emeralds and pearls stuck all over

him and the great rubies on the small dark hand he had waved to

command his servants to approach with salaams and receive his

orders.

“My cousin knows how to take care of me. I am

always better when she is with me. She made me better last night. A

very strong boy I know will push my carriage.”

Dr. Craven felt rather alarmed. If this tiresome

hysterical boy should chance to get well he himself would lose all

chance of inheriting Misselthwaite; but he was not an unscrupulous

man, though he was a weak one, and he did not intend to let him run

into actual danger.

“He must be a strong boy and a steady boy,” he

said. “And I must know something about him. Who is he? What is his

name?”

“It’s Dickon,” Mary spoke up suddenly. She felt

somehow that everybody who knew the moor must know Dickon. And she

was right, too. She saw that in a moment Dr. Craven’s serious face

relaxed into a relieved smile.

“Oh, Dickon,” he said. “If it is Dickon you will be

safe enough. He’s as strong as a moor pony, is Dickon.”

“And he’s trusty,” said Mary. “He’s th’ trustiest

lad i’ Yorkshire.” She had been talking Yorkshire to Colin and she

forgot herself

“Did Dickon teach you that?” asked Dr. Craven,

laughing outright.

“I’m learning it as if it was French,” said Mary

rather coldly. “It’s like a native dialect in India. Very clever

people try to learn them. I like it and so does Colin.”

“Well, well,” he said. “If it amuses you perhaps it

won’t do you any harm. Did you take your bromideae

last night, Colin?”

“No,” Colin answered. “I wouldn’t take it at first

and after Mary made me quiet she talked me to sleep—in a low

voice-about the spring creeping into a garden.”

“That sounds soothing,” said Dr. Craven, more

perplexed than ever and glancing sideways at Mistress Mary sitting

on her stool and looking down silently at the carpet. “You are

evidently better, but you must remember—”

“I don’t want to remember,” interrupted the Rajah,

appearing again. “When I lie by myself and remember I begin to have

pains everywhere and I think of things that make me begin to scream

because I hate them so. If there was a doctor anywhere who could

make you forget you were ill instead of remembering it I would have

him brought here.” And he waved a thin hand which ought really to

have been covered with royal signet rings made of rubies. “It is

because my cousin makes me forget that she makes me better.”

Dr. Craven had never made such a short stay after a

“tantrum”; usually he was obliged to remain a very long time and do

a great many things. This afternoon he did not give any medicine or

leave any new orders and he was spared any disagreeable scenes.

When he went downstairs he looked very thoughtful and when he

talked to Mrs. Medlock in the library she felt that he was a much

puzzled man.

“Well, sir,” she ventured, “could you have believed

it?”

“It is certainly a new state of affairs,” said the

doctor. “And there’s no denying it is better than the old

one.”

“I believe Susan Sowerby’s right—I do that,” said

Mrs. Medlock. “I stopped in her cottage on my way to Thwaite

yesterday and had a bit of talk with her. And she says to me,

‘Well, Sarah Ann, she mayn’t be a good child, an’ she mayn’t be a

pretty one, but she’s a child, an’ children needs children.’ We

went to school together, Susan Sowerby and me.”

“She’s the best sick nurse I know,” said Dr.

Craven. “When I find her in a cottage I know the chances are that I

shall save my patient.”

Mrs. Medlock smiled. She was fond of Susan

Sowerby.

“She’s got a way with her, has Susan,” she went on

quite volubly. “I’ve been thinking all morning of one thing she

said yesterday. She says, ‘Once when I was givin’ th’ children a

bit of a preach after they’d been fightin’ I ses to ’em all, ”When

I was at school my jography told as th’ world was shaped like a

orange an’ I found out before I was ten that th’ whole orange

doesn’t belong to nobody. No one owns more than his bit of a

quarter an’ there’s times it seems like there’s not enow quarters

to go round. But don’t you—none o’ you—think as you own th’ whole

orange or you’ll find out you’re mistaken, an you won’t find it out

without hard knocks.” What children learns from children,’ she

says, ‘is that there’s no sense in grabbin’ at th’ whole

orange—peel an’ all. If you do you’ll likely not get even th’ pips,

an’ them’s too bitter to eat.’”

“She’s a shrewd woman,” said Dr. Craven, putting on

his coat.

“Well, she’s got a way of saying things,” ended

Mrs. Medlock, much pleased. “Sometimes I’ve said to her, ‘Eh!

Susan, if you was a different woman an’ didn’t talk such broad

Yorkshire I’ve seen the times when I should have said you was

clever.’ ”

That night Colin slept without once awakening and

when he opened his eyes in the morning he lay still and smiled

without knowing it—smiled because he felt so curiously comfortable.

It was actually nice to be awake, and he turned over and stretched

his limbs luxuriously. He felt as if tight strings which had held

him had loosened themselves and let him go. He did not know that

Dr. Craven would have said that his nerves had relaxed and rested

themselves. Instead of lying and staring at the wall and wishing he

had not awakened, his mind was full of the plans he and Mary had

made yesterday, of pictures of the garden and of Dickon and his

wild creatures. It was so nice to have things to think about. And

he had not been awake more than ten minutes when he heard feet

running along the corridor and Mary was at the door. The next

minute she was in the room and had run across to his bed, bringing

with her a waft of fresh air full of the scent of the

morning.

“You’ve been out! You’ve been out! There’s that

nice smell of leaves!” he cried.

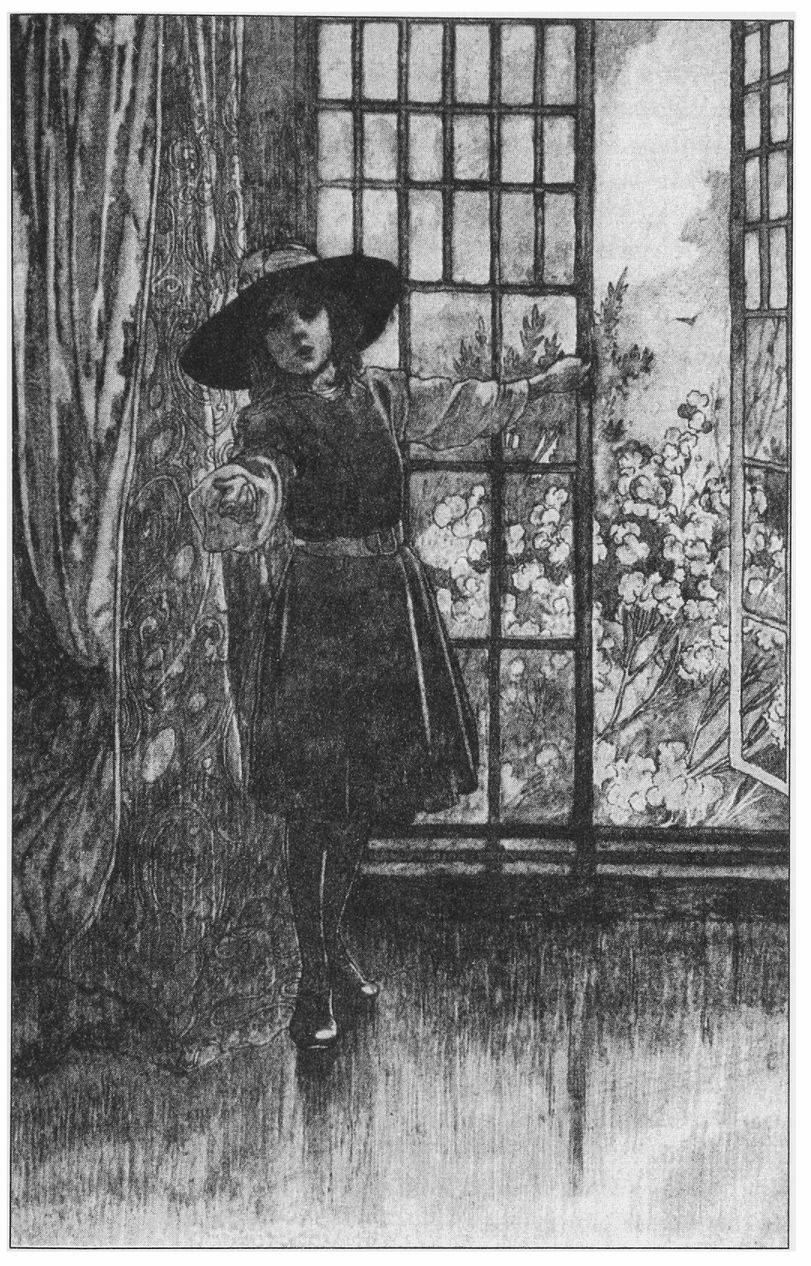

She had been running and her hair was loose and

blown and she was bright with the air and pink-cheeked, though he

could not see it.

“It’s so beautiful!” she said, a little breathless

with her speed. “You never saw anything so beautiful! It has come!

I thought it had come that other morning, but it was only coming.

It is here now! It has come, the Spring! Dickon says so!”

“Has it?” cried Colin, and though he really knew

nothing about it he felt his heart beat. He actually sat up in

bed.

“Open the window!” he added, laughing half with

joyful excitement and half at his own fancy. “Perhaps we may hear

golden trumpets!”

And though he laughed, Mary was at the window in a

moment and in a moment more it was opened wide and freshness and

scents and birds’ songs were pouring through.

“That’s fresh air,” she said. “Lie on your back and

draw in long breaths of it. That’s what Dickon does when he’s lying

on the moor. He says he feels it in his veins and it makes him

strong and he feels as if he could live forever and ever. Breathe

it and breathe it.”

She was only repeating what Dickon had told her,

but she caught Colin’s fancy.

“‘Forever and ever’! Does it make him feel like

that?” he said, and he did as she told him, drawing in long deep

breaths over and over again until he felt that something quite new

and delightful was happening to him.

Mary was at his bedside again.

“Things are crowding up out of the earth,” she ran

on in a hurry. “And there are flowers uncurling and buds on

everything and the green veil has covered nearly all the gray and

the birds are in such a hurry about their nests for fear they may

be too late that some of them are even fighting for places in the

secret garden. And the rose-bushes look as wick as wick can be, and

there are primroses in the lanes and woods, and the seeds we

planted are up, and Dickon has brought the fox and the crow and the

squirrels and a new-born lamb.”

“That’s fresh air,” she said. “Lie on your

back and draw in long breaths of it”

And then she paused for breath. The new-born lamb

Dickon had found three days before lying by its dead mother among

the gorse bushes on the moor. It was not the first motherless lamb

he had found and he knew what to do with it. He had taken it to the

cottage wrapped in his jacket and he had let it lie near the fire

and had fed it with warm milk. It was a soft thing with a darling

silly baby face and legs rather long for its body Dickon had

carried it over the moor in his arms and its feeding bottle was in

his pocket with a squirrel, and when Mary had sat under a tree with

its limp warmness huddled on her lap she had felt as if she were

too full of strange joy to speak. A lamb—a lamb! A living lamb who

lay on your lap like a baby!

She was describing it with great joy and Colin was

listening and drawing in long breaths of air when the nurse

entered. She started a little at the sight of the open window. She

had sat stifling in the room many a warm day because her patient

was sure that open windows gave people colds.

“Are you sure you are not chilly, Master Colin?”

she inquired.

“No,” was the answer. “I am breathing long breaths

of fresh air. It makes you strong. I am going to get up to the sofa

for breakfast. My cousin will have breakfast with me.”

The nurse went away, concealing a smile, to give

the order for two breakfasts. She found the servants’ hall a more

amusing place than the invalid’s chamber and just now everybody

wanted to hear the news from upstairs. There was a great deal of

joking about the unpopular young recluse who, as the cook said,

“had found his master, and good for him.” The servants’ hall had

been very tired of the tantrums, and the butler, who was a man with

a family, had more than once expressed his opinion that the invalid

would be all the better “for a good hiding.”

When Colin was on his sofa and the breakfast for

two was put upon the table he made an announcement to the nurse in

his most Rajah-like manner.

“A boy, and a fox, and a crow, and two squirrels,

and a new-born lamb, are coming to see me this morning. I want them

brought upstairs as soon as they come,” he said. “You are not to

begin playing with the animals in the servants’ hall and keep them

there. I want them here.”

The nurse gave a slight gasp and tried to conceal

it with a cough.

“Yes, sir,” she answered.

“I’ll tell you what you can do,” added Colin,

waving his hand. “You can tell Martha to bring them here. The boy

is Martha’s brother. His name is Dickon and he is an animal

charmer.”

“I hope the animals won’t bite, Master Colin,” said

the nurse.

“I told you he was a charmer,” said Colin

austerely. “Charmers’ animals never bite.”

“There are snake-charmers in India,” said Mary;

“and they can put their snakes’ heads in their mouths.”

“Goodness!” shuddered the nurse.

They ate their breakfast with the morning air

pouring in upon them. Colin’s breakfast was a very good one and

Mary watched him with serious interest.

“You will begin to get fatter just as I did,” she

said. “I never wanted my breakfast when I was in India and now I

always want it.”

“I wanted mine this morning,” said Colin. “Perhaps

it was the fresh air. When do you think Dickon will come?”

He was not long in coming. In about ten minutes

Mary held up her hand.

“Listen!” she said. “Did you hear a caw?”

Colin listened and heard it, the oddest sound in

the world to hear inside a house, a hoarse “caw-caw”

“Yes,” he answered.

“That’s Soot,” said Mary. “Listen again. Do you

hear a bleat—a tiny one?”

“Oh, yes!” cried Colin, quite flushing.

“That’s the new-born lamb,” said Mary. “He’s

coming.”

Dickon’s moorland boots were thick and clumsy and

though he tried to walk quietly they made a clumping sound as he

walked through the long corridors. Mary and Colin heard him

marching—marching, until he passed through the tapestry door on to

the soft carpet of Colin’s own passage.

“If you please, sir,” announced Martha, opening the

door, “if you please, sir, here’s Dickon an’ his creatures.”

Dickon came in smiling his nicest wide smile. The

new-born lamb was in his arms and the little red fox trotted by his

side. Nut sat on his left shoulder and Soot on his right and

Shell’s head and paws peeped out of his coat pocket.

Colin slowly sat up and stared and stared—as he had

stared when he first saw Mary; but this was a stare of wonder and

delight. The truth was that in spite of all he had heard he had not

in the least understood what this boy would be like and that his

fox and his crow and his squirrels and his lamb were so near to him

and his friendliness that they seemed almost to be part of himself

Colin had never talked to a boy in his life and he was so

overwhelmed by his own pleasure and curiosity that he did not even

think of speaking.

But Dickon did not feel the least shy or awkward.

He had not felt embarrassed because the crow had not known his

language and had only stared and had not spoken to him the first

time they met. Creatures were always like that until they found out

about you. He walked over to Colin’s sofa and put the new-born lamb

quietly on his lap, and immediately the little creature turned to

the warm velvet dressing-gown and began to nuzzle and nuzzle into

its folds and butt its tight-curled head with soft impatience

against his side. Of course no boy could have helped speaking

then.

“What is it doing?” cried Colin. “What does it

want?”

“It wants its mother,” said Dickon, smiling more

and more. “I brought it to thee a bit hungry because I knowed tha’d

like to see it feed.”

He knelt down by the sofa and took a feeding-bottle

from his pocket.

“Come on, little ’un,” he said, turning the small

woolly white head with a gentle brown hand. “This is what tha’s

after. Tha’ll get more out o’ this than tha’ will out o’ silk

velvet coats. There now,” and he pushed the rubber tip of the

bottle into the nuzzling mouth and the lamb began to suck it with

ravenous ecstasy

After that there was no wondering what to say. By

the time the lamb fell asleep questions poured forth and Dickon

answered them all. He told them how he had found the lamb just as

the sun was rising three mornings ago. He had been standing on the

moor listening to a skylark and watching him swing higher and

higher into the sky until he was only a speck in the heights of

blue.

“I’d almost lost him but for his song an’ I was

wonderin’ how a chap could hear it when it seemed as if he’d get

out o’ th’ world in a minute—an’ just then I heard somethin’ else

far off among th’ gorse bushes. It was a weak bleatin’ an’ I knowed

it was a new lamb as was hungry an’ I knowed it wouldn’t be hungry

if it hadn’t lost its mother somehow, so I set off searchin’. Eh! I

did have a look for it. I went in an’ out among th’ gorse bushes

an’ round an’ round an’ I always seemed to take th’ wrong turnin’.

But at last I seed a bit o’ white by a rock on top o’ th’ moor an’

I climbed up an’ found th’ little ‘un half dead wi’ cold an’

clemmin’.”af

While he talked, Soot flew solemnly in and out of

the open window and cawed remarks about the scenery while Nut and

Shell made excursions into the big trees outside and ran up and

down trunks and explored branches. Captain curled up near Dickon,

who sat on the hearth-rug from preference.

They looked at the pictures in the gardening books

and Dickon knew all the flowers by their country names and knew

exactly which ones were already growing in the secret garden.

“I couldna’ say that there name,” he said, pointing

to one under which was written “Aquilegia,” “but us calls that a

columbine, an’ that there one it’s a snapdragon and they both grow

wild in hedges, but these is garden ones an’ they’re bigger an’

grander. There’s some big clumps o’ columbine in th’ garden.

They’ll look like a bed o’ blue an’ white butterflies flutterin’

when they’re out.”

“I’m going to see them,” cried Colin. “I am going

to see them!”

“Aye, that tha’ mun,” said Mary quite seriously.

“An’ tha’ munnot lose no time about it.”