9. The Episode of the Malevolent Medium

“He’s dead all right,” said Fen, who was bending over the body. “Bullet in the neck—something like an express rifle, I should think. Blackmailers do occasionally end up this way. Better him than us anyway.”

Cadogan was not even relieved at their miraculous deliverance; he interpreted this, rightly, as being due to the fact that he had never really believed he going to be killed. But Fen gave him little opportunity to meditate on these matters.

The shot entered horizontally,” he said, ‘which means it must have come from the upper windows of the house opposite. In fact, our friend will just be leaving there. Let’s go across.” He picked up his gun and took the key of the office door from Mr. Rosseter’s pocket.

“Oughtn’t we to phone the police?”

“Later. Later,” said Fen, dragging Cadogan from the room. “It’ll be a fat lot of good phoning the police if the murderer gets away.”

“But of course he’ll get away.” Cadogan tripped on a stair-rod and nearly fell. “You don’t think he’s standing over there waiting for us, do you?” But to this question he got no reply.

The lights at Carfax were holding up the traffic in one direction, so they crossed the Cornmarket without delay. They wasted some minutes, however, in searching for the entrance to the flat opposite, and when found in an alley behind the shops, it proved to be locked.

“If this belongs to Miss Alice Winkworth too,” said Fen, “I shall scream.” He really looked as if he might.

A constable standing on the opposite pavement was watching their antics with some curiosity, but Fen was so oblivious of this important fact that he had opened a window and was climbing in before Cadogan could stop him. The constable hastened across to them and addressed himself to Fen’s disappearing form with some indignation.

“Here! Here!” he called. “What do you think you’re doing?”

Having succeeded in getting in at the window, Fen now turned round and leaned out of it again. He spoke rather like a cleric addressing his congregation from the pulpit.

“A man has just been shot dead in the flat opposite,” he answered. “And he was shot from here. Is that sufficient season for you?”

The constable stared at Fen in much the same way as Balaam must have stared at his ass.“’Ere, are you joking?” he said.

“Certainly I am not joking,” said Fen implacably. “Go and see for yourself, if you don’t believe me.”

“Holy God,” said the constable, and hastened back across the Cornmarket

“He’s a simple fellow,” Cadogan commented. “You might be robbing this flat, for all he knows.”

“It’s empty, you fool,” Fen rejoined; and disappeared. In a very short time he was back at the window.

“There’s no one about,” he said. “But there’s a fire-escape leading down to a little green place round the corner, and the window beside it has been forced. Heaven knows where the rifle is—anyway, I haven’t time to search for it now.”

“Why not?”

Fen climbed through the window and dropped on to the pavement beside Cadogan. “Because, you old malt-worm, I don’t want to get delayed giving evidence to that constable. We should have to go down to the station, and that would mean an hour at least.”

“But look here, isn’t it about time the police took over this business altogether?”

“Yes,” said Fen frankly. “It is. And if I were a public-spirited citizen that’s what I should let them do. But I’m not a public-spirited citizen, and anyway I consider this business is our party. The police wouldn’t believe us when we put the thing to them in the first place; we’ve done all the investigation and we’ve run all the risks. I consider we’ve a perfect right to go on and finish the business in our own way. In fact, my blood’s up. There’s something romantic about me,” he added reflectively. “I’m an adventurer manqué: born out of my time.”

“What nonsense.”

“Well, you keep out of it if you like. Go on, run and talk to the police. They”ll put you in the can, anyway, for stealing those groceries.”

“You seem to forget that I’m ill.”

“All right,” said Fen, with elaborate unconcern. “Do what you like. It doesn’t matter to me. I can manage without you.”

“It’s ridiculous to take this attitude—”

“My dear fellow, I quite understand. Say no more about it. you’re a poet, after all, and it’s to be expected.”

“What is to be expected?” said Cadogan furiously.

“Nothing. I didn’t mean anything. Well, I must go before that policeman comes back.”

“Of course if you insist on behaving like a child of two, I shall feel compelled to go with you.”

“Oh? Will you? I dare say you’d only be a hindrance.”

“Not at all.”

“You’ve only been a hindrance so far.”

“That’s quite unjust… Look out, there’s that policeman again.”

The alley curved round behind the building and debouched at its further end in Market Street, which joined the Cornmarket more or less opposite Mr. Rosseter’s office. It was here that Fen and Cadogan cautiously emerged; the constable was for the moment out of sight.

“The Market,” said Fen tersely. And hurrying along the street, they turned in at an entrance on the right.

The Oxford Market is a large one, standing in the right angle formed by the High Street and the Cornmarket. Here they could hope to evade the attentions of the constable, should he choose to follow them, though as Fen remarked, he could scarcely do so until someone else arrived to keep an eye on Mr. Rosseter’s office. There were two main passages, lined with stalls selling meat, fruit, flowers, vegetables, and down one of these they strolled, buffeted by beetle-like housewives intent upon bargains. The air smelt delightfully of raw things and, after the sunlight outside, the great barn-like building was cool and dim.

“All I say,” Fen pursued, “is that this is our pigeon and no one else’s. It may be the glory of a law-abiding age that one doesn’t, literally, have to fight one’s own battles, but it makes life tame. As a matter of fact, we’re perfectly within our rights. We’ve detected a felony and are searching for the criminal, and if the police choose to get in the way it’s their bad luck.” He tired abruptly of these sophistries. “Not that I care a twopenny damn whether I’m within my rights or not. Here’s a café . Let’s go in and get some tea.”

The café was small and primitive, but clean. Cadogan drank his tea avidly and began to take a proper interest in things again. Fen meanwhile had departed to find a telephone and was talking to Mr. Hoskins in his own room.

“Mr. Spode left,” Mr. Hoskins was saying, “shortly after Cadogan and yourself—I don’t know where he was going, but he seemed a trifle uncomfortable, in the social sense, I mean. Sally and Dr. Wilkes are still here.”

“Good. you’ll be pleased to know that Rosseter has just been bumped off under our very noses. But he said he didn’t kill Miss Tardy.”

“Good Lord.” Mr. Hoskins was manifestly startled at this information. “Was he telling the truth, do you suppose?”

“I should think so. He was proposing to kill us at the end of it, so he hadn’t much reason for lying. Someone shot him with a rifle from the flat opposite—someone he was bl—Oh, my fur and whiskers.”

“Are you all right?” Mr. Hoskins asked.

“Physically, but not in the head. I’ve just realized something, and it’s too late now. Never mind, you shall hear all about it later. In the meantime, I wonder if you can possibly discover the identity of a suspect for me—Berlin? He’s a doctor, and uncommonly thin. It sounds easy, but in practice it may be rather awkward.”

“I’ll see what I can do. But I shall have to leave Sally. She says she ought to have gone back to the shop hours ago.”

“She must stay in my room. Wilkes will look after her. It’s a pity he’s so hale and susceptible in his dotage, but that’s a risk she”ll have to take.”

“Are you coming back now? Where can I get hold of you if I find the man?”

“I shall be at the ‘Mace and Sceptre’ about a quarter past six. Ring me there.” Fen lowered his voice and began to give instructions.

When he returned to the table Cadogan had finished the buttered scones and was eating a piece of angel-cake. “The Episode of the Guzzling Bard,” said Fen as he lit a cigarette. “You may kick me if you like… No,” he went on crossly. “don’t fool about, it’s only a figure of speech. I suppose senescence is clouding my brain.”

“What’s up?” said Cadogan with his mouth full.

“It’s surely not necessary for you to take such big bites at a time… It’s a question of where our homicidal friend went after he left the flat.”

“Well, where did he go?”

“Obviously to Rosseter’s office. Don’t you remember the information which would hang him was in Rosseter’s briefcase? There was no point in killing him unless the murderer got that. And I was so childishly excited that I left it there.”

“Lor’,” said Cadogan, impressed. “And we might have cleared the whole business up there and then.”

“Yes. Anyway it’s too late now. Either the murderer’s got it, or the police. A subsidiary point which interests me is how the murderer took his rifle away. I think it was only a small one—might even have been a ’22—but he’d have to have had something innocent-looking, like a golf-bag, to carry it away in.” Fen sighed profoundly.

“What do we do now?”

“I think we seek out Miss Alice Winkworth.”

A woman sitting at a nearby table got up and came over to them. “You mentioned my name?” she said.

Cadogan jumped, and even Fen lost hold momentarily on his equanimity. The interruption went beyond logic; and yet, when all things were considered, there was no great reason why Miss Alice Winkworth should not be eating tea in the same café as themselves. To them it appeared odd; to her, no doubt, it appeared odd also; but an outsider would have been wholly unmoved by the coincidence.

She gazed down on them with manifest disapprobation. Her face was fat, yellow-complexioned, and moonlike, with a rudimentary black moustache, a pudgy nose, and small, suilline eyes—the face of a woman accustomed to exercising an egotistical authority. It was surmounted by greying hair coiled into buns over the ears, and a black hat sewn with a multitude of tiny red and purple beads. On the fourth finger of her right hand was an ostentatious diamond ring, and she wore an expensive but ill-fitting black coat and skirt.

“You were talking about me?” she repeated.

“Sit down,” said Fen amiably, “and let us have a chat.”

“I have no intention of sitting with you,” Miss Winkworth replied. “You, I suppose, are Mr. Cadogan and Mr. Fen. I hear from my employees that you have pestered them with questions about me, and that you, Mr. Cadogan, took it upon yourself to steal part of my property. Now that I have found you, I shall go straight to the police and inform them that you are here.”

Fen stood up. “Sit down,” he said again, and his tone was no longer amiable.

“How dare you threaten—”

“As you well know, a woman was murdered last night. We need some information which you can give us.”

“What nonsense: I deny—”

“She was murdered on your property and with your connivance,” Fen went on remorselessly, “and you benefit from her death.”

“You can prove nothing—”

“On the contrary I can prove a great deal. Rosseter has talked. He is also—as perhaps you know—dead. you’re in a very unfortunate position indeed. You’d do better to tell us what you know.”

“I shall see my lawyer. How dare you insult me in this way? I’ll have the pair of you in gaol for libel.”

“Let’s have no more of this foolery,” said Fen abruptly. “Go to the police if you like. You’ll be immediately arrested for conspiracy to murder, if not for the murder itself.”

Hesitation and fear were in the woman’s greedy little eyes.

“Whereas,” Fen continued, “if you tell us what you know it may be possible to keep you out of it altogether. I say it may: I don’t know. Now, will you take your choice?”

Suddenly, heavily, Miss Winkworth slumped down into a chair, pulling out a lavender-scented lace handkerchief with which she wiped the perspiration from her hands. “I didn’t kill her,” she said in a low voice. “I didn’t kill her. We never meant to kill her.” She looked round suddenly. “We can’t talk here.”

“I see no reason why not,” said Fen. And indeed, the café was almost empty. A single waitress leaned against a pillar by the door, her pale face vacant, a dish-cloth in her hand. The proprietor tampered inexpertly with his shining tea-urn.

“Now,” said Fen curtly. “Answer my questions.”

They had great difficulty in getting any connected story out of Miss Winkworth, but eventually the general outlines emerged with sufficient clarity. She confirmed Mr. Rosseter’s account of the intimidation plan, adding to it some unimportant detail; but asked if she knew the identities of the other two men involved, she shook her head.

“They were masked,” she said. “I was, too. We used the names the old woman gave us.”

“How did you come to meet Miss Snaith in the first place?”

“I’m a medium. A psychic medium. I have Powers. The old woman wanted to get in touch with the Beyond; she was afraid of dying.” A trace of slyness crept into the eyes and the corners of the mouth. “Of course, you can’t always get in touch when you want to, so I sometimes had to arrange things so that she wouldn’t be disappointed. Very comforting messages we got then—just the sort of thing she liked.”

“So the poor misguided creature left you money for faking ectoplasm. Go on. You own the shop in Iffley Road and the one in the Banbury Road, don’t you?”

“Yes.”

“Were you responsible for changing the stock?”

“Yes. I took the toys down from the Banbury Road to the Iffley Road in my car. It wasn’t very difficult. We put all the groceries into the back of the other shop and left the toys in their place. The blinds were down over both shops, so an outsider wouldn’t notice the change.”

“You know,” Fen said to Cadogan, “there’s something richly comic in the thought of these criminal lunatics lugging toys and groceries about at dead of night. I agree with Rosseter—one can scarcely imagine a more childish scheme.”

“It worked, didn’t it?” said the woman venomously. The police wouldn’t believe your friend here when he talked about his precious toyshop.”

“It didn’t work for long. A toyshop that stays where it is is an unsuspicious object enough, but one that moves… Good heavens! The thing cries out for investigation. By the way, how did you hear about Cadogan and the police?”

“Mr. Rosseter found out. He rang up and told me.”

“I see. Who was responsible for getting the toys back to the other shop afterwards?”

“Whoever got rid of the body.”

“And that was—?”

“I don’t know,” said the woman surprisingly. “They drew lots for it.”

“What?”

“I’ve told you: they drew lots. It was a dangerous job, and no one would volunteer. They drew lots.”

“This goes from comedy to farce,” said Fen drily. ‘Not that there isn’t a grain of sense in it. And who got the fatal card?”

“They weren’t to say. I don’t know. Whoever did it was to take back the toys as well. I left my car, and the keys of both shops. The car was to be left in a certain place—I found it this morning—and the keys returned to me by registered post. Then I went away. I don’t know who stayed behind.”

“What time was this?”

“I suppose I left about half past midnight.”

“Ah,” said Fen. He turned to Cadogan. “And you blundered in medias res shortly after one. You must have given the body-snatcher a nasty shock.”

“He gave me one,” Cadogan grumbled.

They stopped talking as the waitress came over to clear away the tea things and give them their bill. When she had departed again:

“And who precisely was involved in this thing?” Fen asked.

“Me and Mr. Rosseter and the two men called Mold and Berlin.”

“What were they like?”

“One of them was—well, undersized; the other was very thin. That one—the one we called Berlin—was a doctor.”

“All right.” Fen tapped the ash from his cigarette into a convenient saucer. “Now let’s hear precisely what happened.”

Miss Winkworth was sullen. “I’m not going to tell any more. You can’t make me.”

“No? In that case, We’ll go along to the police. They”ll make you, all right.”

“I’ve got my rights—”

“A criminal has no rights in any sane society.” Cadogan had never known Fen so harsh before; it was a new and unfamiliar aspect of his character. Or was it merely an expedient pose? “Do you think that after your filthy little conspiracy to murder a deaf, helpless woman anyone is going to trouble himself about your rights? You’ll do better to keep out of the way—and not put them to the test.”

Miss Winkworth put her handkerchief to her pudgy nose and blew. “We didn’t mean to murder her,” she said.

“One of you did.”

“It wasn’t me, I tell you!” The woman raised her voice, so that the proprietor of the café stared.

“I’ll be the judge of that,” said Fen. “Talk more quietly if you don’t want the whole world to know about it.”

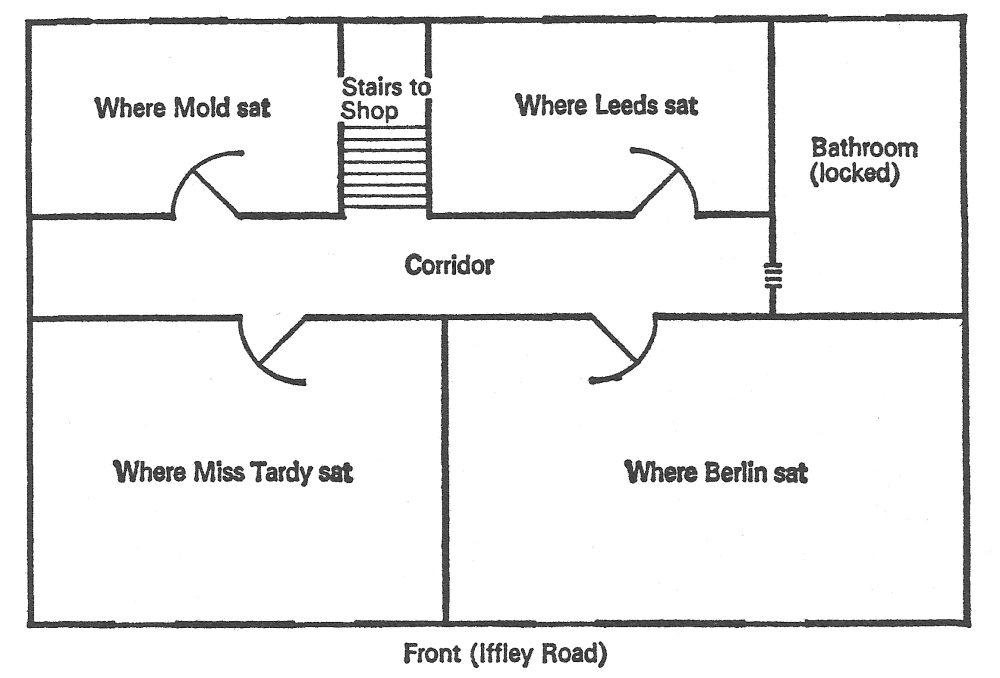

“I—I—You won’t let me get into trouble, will you? I didn’t mean any harm. We weren’t going to hurt her.” The voice was a small, poisoned whine. “I—I think it was about a quarter past ten when we finished arranging the shop. Then we all went upstairs. Mr. Rosseter and Mold and me went into one of the back rooms, and the man called Berlin stayed out to meet the old woman. He’d got bandages round his face, so he wouldn’t be recognized again. Mr. Rosseter was in charge of everything—he said he’d tell us what to do and how to do it. We were paying him money to help us.”

In memory, Cadogan was back in that dark, ugly little place; the linoleum-floored passage with the rickety table where he had left his torch, the two bedrooms at the back, the two sitting-rooms at the front; steep, narrow, uncarpeted stairs; the smell of dust and the gritty feel of it on the fingertips; the curtained windows, the cheap sideboard and leather armchairs; the sticky warmth and the faint smell of blood and the blue, puffy face of the body on the floor…

Then the girl brought in the woman and went away again—or so we thought. We heard the man called Berlin talking to the woman for a bit, and then he came back to us. Then Mr. Rosseter said he’d need to talk to the woman, and we must wait. I thought that was funny, because he wasn’t wearing a mask, but I didn’t say anything at the time. Before he went out he told us we’d better separate and wait in different rooms. The man called Mold asked why—he’d been drinking and he was aggressive—but the other one told him to be quiet and do what he was told; he said he’d discussed the whole thing with Mr. Rosseter, and it was essential to the plan. I thought Mr. Rosseter looked a bit surprised at that, but he nodded. Berlin went into the other room at the front, and I stayed where I was, and Mold went into the second bedroom. Then after a while Berlin came in and joined me, and a bit later Mr. Rosseter—”

“Just a moment,” Fen interposed. “Where was Rosseter all this time?”

“He was with the woman. I saw him go in.”

“Was she alive when he came out?”

“Yes. I heard her voice, saying something to him as he closed the door.”

“Did anyone else go in while he was there?”

“No. I had the door open and I could see.”

“And when he left he came straight back to your room?”

“That’s right. He told Berlin and me it was going to be a job to frighten her, and he and Berlin argued for a bit about something, and I said if they didn’t shut the door she’d hear them. So they shut it.”

“Then Sharman must have murdered her,” Cadogan interposed.

“Hold on a moment,” Fen said. ‘What were they arguing about?”

“It was something legal, about witnessing and so on. I didn’t understand it Then about five minutes after, the other man—Mold—came in and said he thought there was someone prowling round the shop, and we’d better keep quiet for a bit, and we did. I wondered if the woman wouldn’t get away in the meantime, but Mr. Rosseter whispered it was all right, because she wasn’t frightened yet and that he’d told her he had some papers to prepare which might take a certain time. Well, we stayed quiet for quite a time, and I remembered towards the end of it hearing one of the town clocks strike a quarter to twelve. Finally, Mr. Rosseter and Berlin began arguing again, and said it was all a false alarm, and Mr. Rosseter gave the man Mold a gun and a legal paper and told him to go and get on with it.”

“Just a minute. you’d all been together in that room from the time Mold came in and told you someone was prowling around?”

“Yes.”

“No one left it for even a moment?”

“No.”

“How long would you say you all waited there?”

“About twenty minutes.”

“All right. Go on.”

“This man Mold seemed to be the one they’d chosen to do the job. He said he’d call us in when we were needed, and then he went away. But after about a minute he came back and said there was no light in the room where the woman was. Someone had taken the bulb out. He thought the woman had gone, and he was groping about looking for a candle he knew was there when he fell over her, lying on the floor. We went back there with a torch and she was dead, all puffy with a string tied round her neck. The man called Berlin said he was a doctor, and bent down to look at her. Mr. Rosseter seemed all yellow and frightened. He said someone from outside must have done it, and we’d better look in the shop downstairs. Just as we were going down, we saw a girl who was hiding there. Mr. Rosseter showed her the body, and said something to her which frightened her, and sent her away. We didn’t like that, but he said we were masked, so she wouldn’t recognize us again, and she’d keep quiet for her own good. Berlin got up from the body and looked at us queerly and said suddenly: ‘No one here did this.’ Mr. Rosseter said: ‘Don’t be a damned fool. Who else could have done it? You’ll all be suspected if it ever comes out.’ Then Mold said: ‘We’ve got to keep it quiet,’ and I agreed. It was then they decided to draw lots about who should get rid of the body.”

Abruptly, the woman stopped. The recital had been, physically, a strain, but Cadogan saw no sign of any moral appreciation of the acts she had been recounting. She talked about murder as she might have talked about the weather—being far too selfish, thick-skinned, and unimaginative to see the implications either of that final, irrevocable act or of her own position.

“We get nearer the heart of things,” said Fen dreamily. “Personnel: Mold (equals our Mr. Sharman), Berlin (the doctor, unidentified), Leeds (this creature here), Ryde (Sally), and West—where does the enigmatical West come into it, I wonder? Did he claim his inheritance? Rosseter said nothing about him. The impression one gets is that there was a great deal of fumbling and failure all round—except in one instance, of course. God knows what nonsense Rosseter told Sharman and the doctor, or what their precious plan was; it’s of no importance now, anyway. I suppose it doesn’t really matter, either, how Rosseter proposed to contrive his murder and frame-up; that went astray, too. The real point is not who intended to kill the woman, but who did. I confess I shall be interested to discover what the doctor meant when he said no one there could have done it—it links up with Rosseter’s talk about an impossible murder.” He turned again to the woman, who was sniffing at a small yellow bottle of sal volatile; Cadogan noticed that her finger-nails were ringed with dirt. “Would it have been possible for anyone to have been hiding in the flat or the shop before you arrived?”

“No. It was locked, and, anyway, we had a good look round.”

“Could anyone have got through the window of the room Miss Tardy was in?”

“No, it was nailed up. They all were. I haven’t used the flat for a year.”

“Which lets West out,” said Fen “If anyone had come through the shop Sally would have said, and there’s no other way up to the flat except by the staircase from the shop, is there?”

“No.”

“No fire-escape, for instance?”

“No. It’s my belief,” said the woman suddenly, “that that girl did it.”

“As far as we’ve got at present, it’s quite possible,” Fen admitted. “Except,” he added to Cadogan, “that I don’t think she’d have been so ready to tell us things if she had. A bluff like that would have needed colossal nerve, and in any case it wasn’t necessary for her to say anything at all. We shall see.” He glanced at his watch. “Five-twenty—we must go. I want to make sure Sally’s all right, and then go on to the ‘Mace and Sceptre’ to wait for a message from Mr. Hoskins. We shall have to return by devious routes; if that constable’s done his job, half the police of Oxford will be running about looking for us by now.” He stood up.

“Listen,” said the woman urgently. “you’ll keep my name out of it, won’t you? won’t you?”

“Good heavens, no,” said Fen, whose habitual cheerfulness seemed to be restored. “Your evidence is far too important. You never really thought I should, did you?”

“You bastard,” she said. “You bloody bastard.”

“Language,” said Fen benevolently. “Language. don’t try to leave Oxford, by the way; you’ll only be caught. Good afternoon.”

“Listen to me—”

“Good afternoon to you.”