Chapter 4

The Love-Death

I. Eros, Agapē, and Amor

I find it impossible to understand how anyone who had really read both the literature of Gnosticism and the poetry of Gottfried could suggest — as does a recent student of the psychology of amor — that not only Gottfried but also the other Tristan poets, and the troubadours as well, were Manichaeans.Note 1 The period of their flowering, it is true, was that of the Albigensian heresy. It is also true that the cult of amor, with its guiding light, the “Fair Lady of Thought,” was in principle both adulterous and not directed to reproduction. Moreover, the consecration of this love was not an ecclesiastical affair of bell, book, and clergy, but a matter, purely, of the character and sentiments of the couple involved. And finally, the mad disciplines to which a lover might, in the name of love, subject himself, sometimes approached the lunacies of a penitential grove.

There is an account of one who bought a leper’s gown, bowl, and clapper from some afflicted wretch and, having mutilated a finger, sat amidst a company of the sick and maimed before his lady’s door, to await her alms. The poet Peire Vidal (c. 1150–c. 1210?), in honor of a lady named La Loba, “The She-Wolf,” had himself sewn into the skin of a wolf, and then, provoking a shepherd’s dogs, ran before them until pulled down, nearly dead — after which the countess and her husband, laughing together, had him doctored until well.Note 2 Sir Lancelot leapt from Guinevere’s high window and ran lunatic in the woods for months, clad only in his shirt.Note 3 Tristan too went mad. Such lovers, known as Gallois, seem to have been, if not common, at least not rare, in the days when knighthood was in flower. There were some who undertook the discipline called in India the “reversed seasons,” where the penitent, as the year became warmer, piled on more and more clothing until by midsummer he was an Eskimo, and, as the season cooled, peeled away, until in midwinter he was, like Lancelot, in his shirt.Note 4 One is reminded of the childlike contemporary of these poets, Saint Francis (1182–1226), who, conceiving of himself as the troubadour of Dame Poverty, begged alms with the lepers, wandered in hair shirt through the winter woods, wrote poems to the elements, and preached sermons to the birds.

However, the first point to be remarked in connection with the Albigensian charge is that, whereas according to the Gnostic-Manichaean view nature is corrupt and the lure of the senses to be repudiated, in the poetry of the troubadours, in the Tristan story, and in Gottfried’s work above all, nature in its noblest moment — the realization of love — is an end and glory in itself; and the senses, ennobled and refined by courtesy and art, temperance, loyalty and courage, are the guides to this realization. Like a flower potential in its seed, the blossom of the realization of love is potential in every heart (or, at least, every noble heart) and requires only proper cultivation to be fostered to maturity. Hence, if the courtly cult of amor is to be catalogued according to its heresy, it should be indexed rather as Pelagian than as Gnostic or Manichaean, for, as noticed in Occidental Mythology,Note 5 Pelagius and his followers absolutely rejected the doctrine of our inheritance of the sin of Adam and Eve, and taught that we have finally no need of supernatural grace, since our nature itself is full of grace; no need of a miraculous redemption, but only of awakening and maturation; and that, though the Christian is advantaged by the model and teaching of Christ, every man is finally (and must be) the author and means of his own fulfillment. In the lyrics of the troubadours we hear little or nothing of the fall and corruption either of the senses or of the world.

Moreover, in contrast to the spirit of the indiscriminate Love Feast, whether of the orgiastic Phibionite variety or the charitable church-supper type, the address of amor is personal. It follows the lead and allure, as we have said, of the senses, and in particular of the noblest sense, that of sight; whereas the whole point of the Love Feast, and the very virtue of communal love, is that its aim is indiscriminate. “Love thy neighbor as thyself.”Note 6 Selectivity, the prime function of the eye and heart, is in the agapē methodically abjured. The lights go out, so to say, and whatever is at hand, one loves — either in the angelic way of charity or in the orgiastic, demonic way of a Dionysian orgy; but in either case, religiously: in renunciation of ego, ego judgment, and ego choice.

It is amazing, but our theologians still are writing of agapē and eros and their radical opposition, as though these two were the final terms of the principle of “love”: the former, “charity,” godly and spiritual, being “of men toward each other in a community,” and the latter, “lust,” natural and fleshly, being “the urge, desire and delight of sex.”Note 7 Nobody in a pulpit seems ever to have heard of amor as a third, selective, discriminating principle in contrast to the other two. For amor is neither of the right-hand path (the sublimating spirit, the mind and the community of m an), nor of the indiscriminate left (the spontaneity of nature, the mutual incitement of the phallus and the womb), but is the path directly before one, of the eyes and their message to the heart.

There is a poem to this point by a great troubadour (perhaps the greatest of all), Guiraut de Borneilh (c. 1138–1200 ?):

So, through the eyes love attains the heart:

For the eyes are the scouts of the heart,

And the eyes go reconnoitering

For what it would please the heart to possess.

And when they are in full accord

And firm, all three, in the one resolve,

At that time, perfect love is born

From what the eyes have made welcome to the heart.

Not otherwise can love either be born or have commencement

Than by this birth and commencement moved by inclination.

By the grace and by command

Of these three, and from their pleasure,

Love is born, who with fair hope

Goes comforting her friends.

For as all true lovers

Know, love is perfect kindness,

Which is born — there is no doubt — from the heart and eyes.

The eyes make it blossom; the heart matures it:

Love, which is the fruit of their very seed.Note 8

We have here attained, I would say, new ground: such ground as in the whole course of our long survey of the world’s primitive, Oriental, and Occidental traditions has not been encountered before. It is the ground, unique and new, on which stands the modern self-reliant individual — in so far, at least, as he has yet been able to mature, to show himself, and to hold his gained ground against the panic weight in opposition of the old and new mass and tribal thinkers. In the nineteen lines of this troubadour poem, in fact, there already comes to view a prospect of that world of Renaissance man which in art was presently to be typified in the rules, the objectively discovered principles, of Renaissance (linear) perspective: the organization of a selected or imagined field from an individual point of view, along lines going out toward a vanishing point from the locus of a living pair of eyes — according to the impulse, moreover, of the individual’s private heart. The world is now showing itself in its own sweet light and form, at last, to men and women of sense, who are daring to look, to see, and to respond. The system of problems of the controlling religious tradition is in principle disregarded, and the individual standpoint becomes decisive. And so, although it is true that in the century of the troubadours there was rampant throughout Europe a general Manichaean heresy, and that many of the ladies celebrated in the poems are known to have been heretics — just as others were practicing Christians, and the poets themselves communicants of one tradition or the other — in their character as artists and in their poetry and song the troubadours stood apart from both traditions. The whole meaning of their stanzas lay in the celebration of a love the aim of which was neither marriage nor the dissolution of the world. Nor was it even carnal intercourse; nor, again — as among the Sufis — the enjoyment, by analogy, of the “wine” of a divine love and the quenching of the soul in God. The aim, rather, was life directly in the experience of love as a refining, sublimating, mystagogic force, of itself opening the pierced heart to the sad, sweet, bittersweet, poignant melody of being, through love’s own anguish and love’s joy.

One thinks here of the Japanese courtly gallants and their loves in Lady Murasaki’s Tale of Genji, and there is indeed a common sentiment in the Mahāyāna Buddhist “awareness of the pity of things” (Japanese: mono no awarē wo shiru);Note 9 however, as remarked in Oriental Mythology, the ambience of religion hangs there over all, whereas in the love lyrics of the troubadours, even where analogies to certain religious motifs would seem to be obvious, mythological references are ignored and the poem remains frankly and wholly secular, with the poet as the devotee of his lady, who is radiant and potent not by analogy, but with a brilliance and grace of her own that is sufficient for life in this world. Let me cite, for example, three stanzas from a celebrated poem known as “The Joy of Being in Love,” by another of the greatest of the Provencal masters of this art, Bernart de Ventadorn (fl. c. 1150–1200 ?):

It is no marvel, that I should sing

Better than any other singer;

For my heart more draws me toward

Love, And I am likelier made to her command.

Heart and body, wisdom and wits,

Strength and power, have I wagered:

The bridle so draws me toward

Love That I attend to nothing else.

This love smites me so gently

At heart and with such sweet savor!

Of grief do I die one hundred times a day,

And of joy revive, again a hundred.

My malady, indeed, is of excellent kind;

More worth, this malady, than any other good:

And since my malady is so good for me,

Good, after the malady, will be its cure.

Noble Lady, nothing do I ask of thee

But that thou shouldst take me for thy servant.

I would serve as one serves a good lord,

Whatever reward I might gain.

Behold, I am at thy command:

Sincere and humble, gay and courteous.

Neither bear nor lion art thou,

To kill me, as I here to thee surrender.Note 10

From the courts of Provence this poetry passed to Germany, where it was reattuned to the language and spirit of the Minnesingers, the singers of minne (amor); and among these the leading master, wandering from court to court, was Walther von der Vogelweide (c. 1170–c. 1230), who brought to his lyrics a typically German tone of moral depth and fervor, threaded with a new strain of sympathy for the rustic and the natural against the artificialities of fashion. The morality of this Christian poet was of a type, however, not preached in church; for, as Henry Osborn Taylor has remarked of his blithe little “Under the Linden”: “Marvelously, it gives the mood of love’s joy remembered — and anticipated too. The immorality is complete … and rendered most alluring by the utter gladness of the girl’s song — no repentance, no regret; only joy and roguish laughter.”Note 11

The pretty runs of rhyme and the charming sense of innocence of the medieval language I find impossible to rerender, but the sense of fresh young delight, I think, comes through:

Under the linden,

On the heath,

There was our bed for two;

There you will find,

Gently arranged,

Broken flowers and grass.

Beside the woods in a dale,

Tandaraday!

Gently sang the nightingale.

I came a-walking

Toward the stream,

My lover had come before.

There was I greeted:

“My lady fair!”

So am happy now for evermore.

Did he kiss me? Full a thousand clips.

Tandaraday!

See how red now are my lips.

There he’d prepared,

Luxuriously,

A bedding place of flowers:

It would still bring a smile

Inwardly,

If one chanced along that way.

For by the roses one can see,

Tandaraday!

The pillow where my head would be.

That he lay beside me,

If anyone knew

(God forbid!), I’d be mortified.

But whatever he did with me,

No one shall ever

Know anything of that: only he and I

And a tiny little bird,

Tandaraday!

Who will never let fall a word.Note 12

The morality here is of Heloise in the first fair days of her love, and her courageous gospel can be heard again through many of Walther’s lines:

Whoever says that love is sin,

Let him consider first and well:

Right many virtues lodge therein

With which we all, by rights, should dwell.Note 13

“Woman will be ever woman’s noblest name, greater in worth than Lady!” Walther wrote.Note 14

“It took a German,” states Professor Taylor, “to say this.”Note 15 And again, it took a German to recognize in the world-transfiguring sentiment of love as minne, amor, an experience of that same transcendent, immanent ground of being, beyond duality, which Schopenhauer six centuries later was to celebrate in his philosophy. We have already taken note of Gottfried of Strassburg’s celebration of this mystery in his symbology of the love grotto with its crystalline bed in the place of the altar of the sacrament. A number of W alther’s poems, also, extend the revelation of the goddess Minne to a metaphysical depth beyond anything suggested either in the Provengal or in the Old French love poetry of his day:

Minne is neither male nor female,

She has neither a soul nor a body,

She resembles nothing imaginable.

Her name is known; her self, however, ungrasped.

Yet nobody from her apart

Merits the blessing of God’s grace.

She comes never to a false heart.Note 16

Now it is a matter of no small moment that in the period of this idyllic poetry the world of harsh reality should have been about as dangerous and unlikely a domicile for amor as the nightmare of history has ever produced. We have mentioned the devastation of southern France. The whole of Central Europe likewise was in a state of hideous turmoil. For with the death in the year 1197 of the Hohenstaufen Emperor Henry VI, surnamed the Cruel, the crown of the Holy Roman Empire had fallen to the ground and was rolling like a fumbled football for anyone to retrieve. And the armies battling to possess it — on one hand, of the allied English, papal, and Guelph contenders, and, on the other, of the German princes and incumbent Philip of Swabia — were everywhere pillaging towns and villages, devastating whole provinces, perpetrating the most brutal and revolting crimes;Note 17 which wanton work continued until about 1220, when the brilliant young nephew of the murdered Philip, Frederick II (1194–1250), was finally crowned Emperor in Saint Peter’s by a reluctant and uneasy Pope. Walther had been a witness to these horrors, and he wrote of them with unmitigated scorn:

I saw with my own eyes hidden things about men and women, heard and saw all they did and said. How Rome lied and betrayed two kings, I heard. And when the popes and laity had formed their contending parties, there took place the most terrible war that ever was or will ever be: the worst, because both the body and the soul were thereby slain.…Note 18

Ironic, is it not? In the name of love and of peace on earth to men of good will, treachery, arson, pillage, and massacre everywhere; and in such an age the elevation of the most glorious visions in radiant glass and carved stone of that peace and love fulfilled! Fulfilled, however, not on earth, but in a realm away from this vale of tears, to which the most blessed opener of the gate is that woman shining as the sun, to whom the cathedral itself is dedicate, earthly, yet the Mother of God — the Virgin Mary, Notre Dame. In the words of the long-cherished hymn “Salve Regina” composed by Abelard’s elder contemporary Adhemar de Monteil, Bishop of Le Puy (d. 1098), which is to this day engraved, with love, in the heart of every kneeling Catholic:

Hail, holy Queen, Mother of Mercy,

Our life, our sweetness, and our hope,

All hail!

To thee we cry, poor banished children of Eve;

To thee we sigh, weeping and mourning in this vale of tears.

Therefore, O our Advocate,

Turn thou on us those merciful eyes of thine;

And after this our exile,

Show unto us Jesus, the blessed fruit of thy womb.

O merciful, O kind, O sweet Virgin Mary!Note 19

The last three aspirations, “O merciful, O kind, O sweet Virgin Mary!” were added by Abelard’s exact contemporary and dangerous challenger in debate, the mighty Saint Bernard of Clairvaux (1091–1153), to whom Dante, in the Commedia, assigns the loftiest possible station, at the very feet of God. Throughout his lifetime this passionate preacher of transcendental euphoria strained every metaphor in the book of love to elevate the eyes of men from the visible women of this earth to the glorified form of that crowned Virgin Mother above, who is the Queen of Angels and of Saints — and Dante, in due time, followed suit. However, the troubadours, minnesingers, and epic poets of the century, in their celebration of amor, remained in Nietzsche’s sense “true to this earth,” this vale of tears where the devil roams for the ruin of souls. For in their view, not heaven but this blossoming earth was to be recognized as the true domain of love, as it is of life, and the corruption ruinous of love was not of nature (of which love is the very heart) but of society, both lay and ecclesiastical: the public order and, most immediately, its sacramentalized loveless marriages.

Among the verse forms of the troubadours, the song of the parting of lovers at dawn, at the warning of the watchman (the Alba, “Dawn Song,” or Aubade, which became the Tagelied of the minnesingers) rendered simply yet dramatically the sense of discontinuity between the two worlds, on one hand of love’s rapture, and on the other of the social order epitomized in the lady’s dangerous spouse, “the jealous one,” lo gilos. Here is a frequently quoted anonymous example:

In an orchard, under a hawthorn tree,

By her side the Lady clasps her lover,

Till the watchman calls that dawn has appeared.

O God! O God! this dawn! how quickly it comes!

“Would to God the night never had ended,

That my love might never depart from me,

Nor ever the watchman sight day or dawn.

O God! O God! this dawn! how quickly it comes!

“Sweet love, let us start anew our dear game

In the garden where the birds are warbling,

Till the watch sounds again his flageolet.”

O God! O God! this dawn! how quickly it comes!Note 20

In the Tristan romance King Mark is of course in the role of the jealous spouse; and his royal estate, Tintagel, with its elegant princely court, stands for the values of the day world — history, society, knightly honor, deeds, career and fame, chivalry and friendship — in absolute opposition to the grotto of the timeless goddess Minne, which is of the order of enduring nature, in the forest where the birds still sing. Set apart from all spheres of historic change, the Venus Mountain with its crystalline bed has been entered by lovers through all ages, from every order of life. Its seat is in the heart of nature — nature without and within — which two are the same. And its virtue, so, is of the species, not of this particular culture, nor of that: Veda, Bible, or Qu'ran; but of man pristine in the universe — which is something, however, that in this vale of tears is never to be seen, since we are each brought up (are we not?) in the ethnic sphere of this or that particular culture.

The immanent yet lost — but not forgotten — realm within us all is in Celtic mythology and folklore allegorized variously as the Land below Waves, the Land of Youth, the Fairy Hills, and, in Arthurian romance, that Never Never Land of the Lady of the Lake where Lancelot du Lac was fostered and from which Arthur received his sword Excalibur. In the earliest of the old chronicles of King Arthur — the Welsh monk Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia Regum Britanniae (ad 1136) — it is told that at the time of his great last battle with his traitorous son Mordred, “Arthur himself was wounded mortally and borne away, for the healing of his wounds, to the island Avalon.”Note 21 And in a later work, the Vita Merlini (c. 1145?), the same chronicler adds that the boat was steered by an old Irish abbot, Barinthus, and that in Avalon the wounded king was tended by Morgan la Fee and her sisters. The next we hear is from an old French verse chronicle by a Norman poet named Wace, the Roman de Brut (ad 1155), where it is added that “Arthur is still in Avalon and awaited by the Britons; for, as they say and believe, he will return from that place to which he passed and will again be alive.”Note 22 And then finally (c. 1200), an English country priest named Layamon not only transformed the old Irish abbot into something more romantic but let the wounded king himself announce the prophecy of his second coming. Arthur, we here read, had been wounded with no less than fifteen dreadful wounds, into the least of which one might have thrust two gloves, and to a young kinsman, dear to him, who stood by where he lay on the ground, he said these words with sorrowful heart:

“Constantine, thou wert Cador’s son: I here give to thee my kingdom. Defend my Britons ever in thy life; maintain for them all the laws of my days and all the good laws of the days of Uther. And I myself will go to Avalon, to the most beauteous of all women, to the queen Argante, an elf marvelously fair, and she will make my wounds all sound, make me whole with a healing drink. And anon I shall come again to my kingdom and dwell among the Britons in great joy.”

And even while he was speaking thus there approached from the sea a little boat, borne by the waves. There were therein two women of marvelous form, and they took Arthur and bore him quickly and laid him softly in the boat and sailed away.Note 23

We recall the telling line from Tennyson’s “Passing of Arthur,” in his Idylls of the King:

From the great deep to the great deep he goes,

when the wounded king in a dusky barge, wherein were three dark queens, passed to Avalon, “to be king among the dead.”

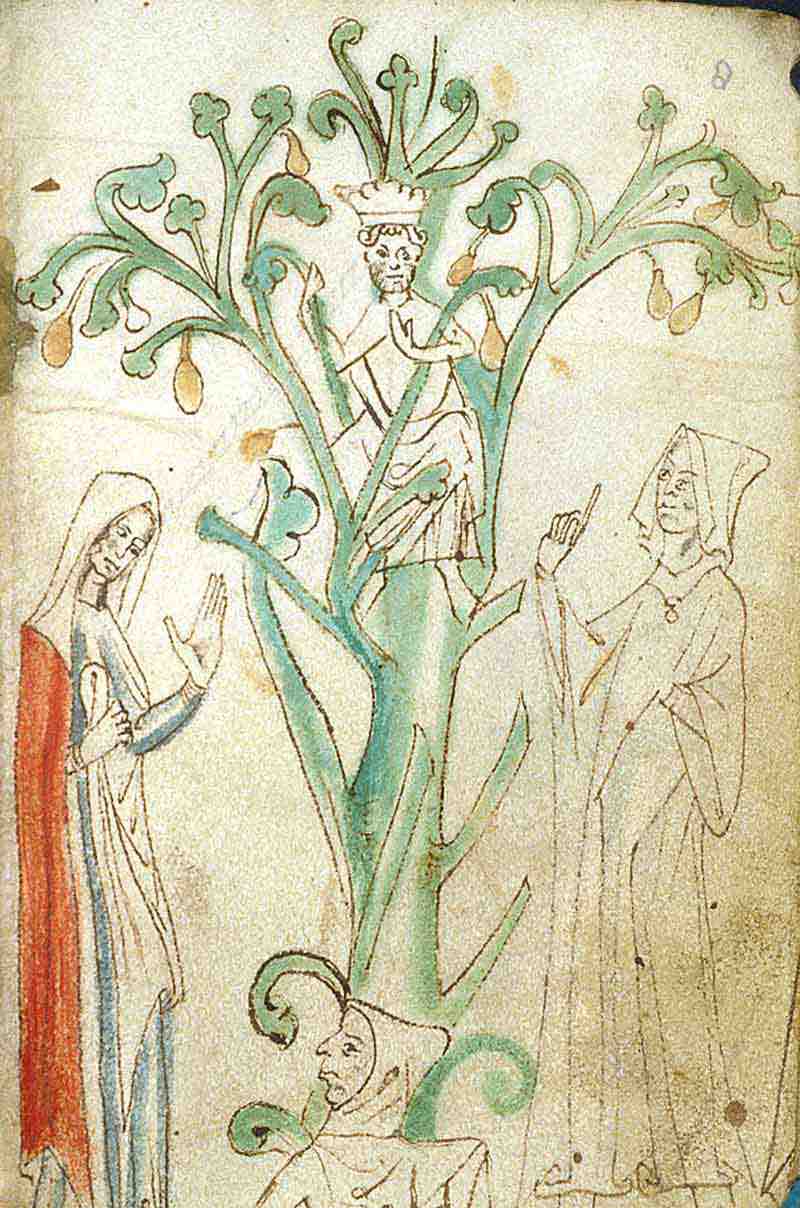

The name, Avalon, of that timeless land beyond the setting sun,

Where falls not hail, or rain, or any snow,

Nor ever wind blows loudly,

is cognate with the Welsh afallen, “apple tree” (from afal, “apple”), and so reveals the affinity of this Celtic Land below Waves with the Isle of the Golden Apples of the classical HesperidesNote 24 — and thereby with the entire complex of that garden of immortality of the Great Goddess of the two worlds of death and life to which so many pages of this study of the mythologies of mankind have been devoted. An echo of the same theme of the paradisial garden of the goddess, with its tree of immortal life, is to be recognized even in the first stanza of the alba quoted earlier, where the lady, under a hawthorn tree, clasps her lover to her side. The Christian figure of the pietà, the dead Savior on his mother’s knees, who will presently return alive, is also of this complex. Can it be accidental, then, that the king had fifteen wounds — the fifteenth day of the moon being that of the culmination of its waxing and beginning of its waning, toward death and, after three days’ dark, rebirth? Moreover, the mortally wounded Tristan’s first melancholy voyage to Isolt’s Dublin Bay, in a self-propelled coracle that bore him infallibly to her castle, is certainly but another variant and example of this same Land-below-Waves motif: so that Isolt, the Lady of the Lake, and the Goddess Mother of the pietà in their final sense are at one: opposed in every measure to the judgments of this day world of ours, of the Sons of Light.

II. The Noble Heart

As in the poetry of the troubadours, so in Gottfried’s Tristan, love is bom of the eyes, in the world of day, in a moment of aesthetic arrest, but opens within to a mystery of night. The point is first made in his version of the love tale of Tristan’s parents, Blancheflor and Rivalin. For there was in their case no potion at work, inspiring magically a premonition a priori of the course along which they were to be drawn through sensuous allure, from love’s meeting of the eyes, to love’s pain, love’s rapture, and on to death.

Figure

35. Blancheflor

(print, United States, 1905)

Beautiful, innocent Blancheflor, the sister of King Mark, was simply sitting among the ladies, watching the sort of tournament called a bohort, in which knights, jousting without armor, contend with only shields and blunt lances, when she began to hear those around her murmuring: “Look! What a heavenly man. How he rides!” And her eyes, searching, discovered Rivalin. “How well he handles that shield and lance!” they were all saying.

“What a noble head! What hair! Happy the woman who gets him!”

He was a youth who had arrived lately from his own estates in Brittany, drawn to her brother’s court by its fame. And when the game had broken up, this joy-giving knight came cantering Blancheflor’s way to salute courteously his host’s sister, in the kingdom of whose heart he had already won the crown. His eyes met hers. “May God bless you, beautiful lady!”

“Merci!” she answered kindly; and, though discomposed by his gaze, pressed on: “May the Blessed God, who makes all hearts blessed, give blessing to your heart and mind! I congratulate you heartily; yet I have a certain small complaint to plead.”

“Ah?” said he. “Sweet lady, what have I done?”

She answered: “Through a friend of mine, the best I ever had” — and she meant by that her heart.

“Good Lord!” he thought. “What tale is this?”Note 25

Gottfried’s analysis, from this point on, of the brooding of the stricken couple opens poignantly, through a tale of young romance, to the ominous love-death theme announced already in his Prologue (See Experience and Authority and The World Transformed.) and to be developed, ever mounting, through his handling of the legend of their son. As in the poem of the troubadour Borneilh, so in Gottfried’s work, love is born of the eyes and heart.

However, here there is a new interest brought to the stricken heart itself: what happens there, and to what end; for not every heart opens to love. Gottfried’s term is “the noble heart” (das edele herze); and as the most learned and discerning of his recent interpreters, Gottfried Weber, shows in a thoroughgoing two-volume total study of the romance,Note 26 this crucial concept is, in fact, the nuclear theme of the poet’s entire work. It opens inward toward the mystery of character, destiny, and worth, and at the same time outward, toward the world and the wonder of beauty, where it sets the lover at odds, however, with the moral order. The poet in his Prologue had already dedicated himself, his life and work, to those alone who could bear together in one heart “dear pain” as well as “bitter sweetness” ; and, as Professor Weber observes, it is just this readiness to embrace love’s pain along with its rapture that makes the noble heart exceptional. “Nor is the pain that is so endured,” he writes, “merely adventitious, overlaid from without upon a pleasure in love that is alone essential. The pain is implicit, rather, in the very delight by which it is complemented — to such a degree that the pleasure and pain are indissolubly interlaced, as commensurate components of one experience of existence. And in fact,” this perceptive critic concludes, “the poet’s intention to give verbal force to this idea is what justifies, both poetically and philosophically, his repeated use — already anticipatively in the Prologue — of the rhetorical device of the oxymoron.”Note 27

Now this classical rhetorical term, “oxymoron,” is defined in Webster’s Dictionary as “a combination for epigrammatic effect of contradictory or incongruous words (cruel kindness, laborious idleness).”Note 28 It is a term derived from the Greek ὀξύ-μωρος “pointedly foolish,” and denotes a mode of speech commonly found in Oriental religious texts, where it is used as a device to point past those pairs of opposites by which all logical thought is limited, to a “sphere that is no sphere,” beyond “names and forms” ; as when in the Upaniṣads we read of “the Manifest- Hidden, called ‘Moving-in-secret,’ which is known as ‘Being and Non-being’”:Note 29

There the eye goes not;

Speech goes not, nor the mind: Note 30

or when we open a Zen Buddhist work called The Gateless Gate and there read of “the endless moment” and “the full void”:

Before the first step is taken the goal is reached.

Before the tongue is moved the speech is finished.Note 31

Compare the language of the Buddhist texts of “The Wisdom of the Yonder Shore” (prajñā-prāmitā), discussed in Oriental Mythology:

The Enlightened One sets forth in the Great Ferryboat, but there is nothing from which he sets forth. He starts from the universe; but in truth he starts from nowhere. His boat is manned with all perfections; and is manned by no one. It will find its support on nothing whatsoever and will find its support on the state of all-knowing, which will serve as a non-support.Note 32

We term such speech “anagogical” (from the Greek verb ἀν-άγω, “to lead upward” ) because it points beyond itself, beyond speech. William Blake in the same wisdom of the yonder shore wrote of The Marriage of Heaven and Hell. Nicholas Cusanus (1401–1464) wrote in his Apologia doctae ignorantiae (“Apology for Learned Unknowing”) that “God is the simultaneous mutual implication of all things, even the contradictory ones,” and in this sense protested against what he called “the present predominance of the Aristotelian sect, which considers the coincidence of opposites a heresy, whereas its admission is the starting point of the ascension to mystical theology.”Note 33 Even Saint Thomas Aquinas states, in a sentence of mystical insight, that “then alone do we know God truly, when we believe that he is far above all that man can possibly think of God.”Note 34 And accordingly, in Gottfried, for whom the mode of divine manifestation in human life is love, the “pointedly foolish” oxymoron is the most appropriate stylistic signal of the mystery of which his work is the text.

In the progress of his legend the steadily mounting tension of the polarities of joy and sorrow, love against honor, death-life, light and darkness, can be read as a gradually deepening and expanding realization of the nature of that mighty goddess beyond the male-female polarity who was celebrated by the Minnesinger Walther: the same represented in the center of the Orphic Pietroasa bowl (Figure 5), between the two lords of the light and the great dark, the eye and heart, Apollo and the god of the abyss; or again, of whom the Graces and the Muses are the manifest allure (Figure 20) — dancing in tripody before the eye of heaven, while yet, with silent Thalia, immobile in the earth.

One cannot help thinking also, in this connection, of the modern finding in the realm of atomic physics of the “principle of indeterminacy, or complementarity,” according to which, in the words of Dr. Werner Heisenberg, “the knowledge of the position of a particle is complementary to the knowledge of its velocity or momentum. If we know the one with high accuracy we cannot know the other with high accuracy; still we must know both for determining the behavior of the system. The space-time description of the atomic events is complementary to their deterministic description.”Note 35

Apparently in every sphere of human search and experience the mystery of the ultimate nature of being breaks into oxymoronic paradox, and the best that can be said of it has to be taken simply as metaphor — whether as particles and waves or as Apollo and Dionysus, pleasure and pain. Both in science and in poetry, the principle of the anagogical metaphor is thus recognized today: it is only from the pulpit and the press that one hears of truths and virtues definable in fixed terms. In Gottfried’s world there was no tolerance of “the Ass Festival” (as Nietzsche named it) of those who would make thinkable the unthinkableness of being. “Life itself,” wrote Nietzsche, “confided to me this secret: ‘Behold,’ it said, ‘I am what must always overcome itself.’”Note 36 And in Gottfried’s world as well, the self-surpassing power of life, which is experienced in love when it wakes in the noble heart, brings pain to the entire system of fixed concepts, judgments, virtues, and ideals of the mortal being assaulted.

Rivalin’s spiritual plight, after his first brief exchange, eye to eye, with the beauty of Blancheflor, the poet likens to the agony of a bird that has come down on a limed twig: “When it becomes aware of the lime, it lifts to fly, still held by its feet, and spreading wings, makes to go; but then wherever it brushes the twig, however lightly, it is caught tbe more, and made fast.”Note 37 The noble youth presently realized that he was trapped. “And yet,” as the poet warns,

even now that sweet Love had brought his heart and mind to her will, it was still unknown to him what a keen torment love was to be. Not until he had pondered in all detail, from end to end, the destiny [aventiure]* that was now his in his Blancheflor — her hair, her brow, her temples, cheeks, mouth and chin, the joyful Easter Day that couched laughing in her eyes — did True Love [diu rehte minne] come, that infallible fire lighter, who set going a fever of desire. And the flame that then fired his heart and incinerated his body let him know in full force what piercing pain and yearning anguish are.… Silence and a mien of melancholy were the best he could show the world, and what had formerly been his gaiety now turned to a yearning need.

Nor did the languishing Blancheflor escape a like history of pining. She was laden, through him, with the same weight of sorrow as he, through her; for Love, the Tyrant [diu gewaltaerinne Minne], had invaded her senses too, somewhat too tempestuously and taken from her by force the best part of her composure. In her demeanor she was no longer at one — as she had used to be — with herself and with the world. Whatever pleasures she had been accustomed to, whatever pastimes she had enjoyed, they all displeased her now. Her life took shape as the very image of the need so close to her heart; and of nought that she was suffering from this yearning had she any understanding whatsoever. Never had she experienced such heaviness and heart’s need. “O Lord God,” she said to herself, time and time again, “what a life I lead!”Note 38

The power of free choice, and even of conceiving of any end or joy beyond the destiny to which the tyrant-goddess Love (diu gewaltaerinne Minne) had consigned them, had been taken from this helpless couple. On a tide beyond their knowledge or control they were to be carried to the work — the destiny of surpassing themselves — to which they were assigned; and the occasion occurred as though arranged for them — and yet apparently only by accident — when the brave young earl, doing battle for his host in a war begun by a neighboring king, was run through by a lance and carried from the battlefield on the very point of death.

As Gottfried tells:

Many a noble woman wept for him, many a lady mourned for his life; indeed, all who had seen him lamented the misfortune. But no matter how sorrowful they, for his wounding, it was alone his Blancheflor — the pure maid, gentle and gracious — who with unrelenting fervor, moaned and wept with eyes and heart for the dear pain of her heart.Note 39

Her old nurse, therefore, made anxious for the young thing’s life, took thought and, reasoning, “What harm can it be with the man already half dead?” contrived to admit her delicate charge, alone, to the quiet chamber where the young earl lay wounded on a couch. And the anxious girl, beholding him there, approached gingerly in fright and, perceiving how close he lay to death, fairly swooned. She bent to study him, tenderly brought her cheek to his, and then swooned indeed. So that now the two lay together on that couch, unconscious and quite still, her cheek to his cheek, as though both were dead. And they remained so for some time.

Whereafter [as we next learn] Blancheflor, reviving a little, took her darling in both arms and, placing her mouth to his, in a very short space of time had kissed him one hundred thousand times; which activity so fired his senses and informed his zeal for love that [as Gottfried further relates] he strained that glorious woman to his half-dead body, ardently and closely, until, before long, their mutual desire was realized and from his body that sweet woman received a child. The man was nearly dead — both from the woman and from love; and never would have recovered had God not stayed him in his need. But he did recover, since so it was to be.…

And thus Blancheflor was healed of her heart’s anguish; but what she carried thence was death. She had been freed of her need when love came, but it was death she conceived with her child. Of the child and death within her, she knew not, but of love and the man, she knew well. For he was hers and she was his; she was he and he was she: there were they — and there was true love.Note 40

The rest can be shortly told.

News arrived of an invasion of Rivalin’s own estates and, with his Blancheflor, he sailed to Brittany, to be slain there in a battle. And when the girl, now big with child, received that grievous news, her tongue froze and her heart became stone; she uttered neither “Oh!” nor “Alas!” but sank to the earth and, four days later, in pain, gave birth and died.

“But look! The little son lives!”Note 41

To protect the name of the dead parents of this little nephew of King Mark, his father’s loyal marshal, Rual li Foitenant, with his wife raised him as their own son, letting no one — even the boy himself — know the story of his birth. They named him Tristan, as they said, because triste means “sorrow,” and in sorrow Tristan had been born. When he was seven, they sent him off with a tutor named Curvenal (Wagner’s Kurvenal) to learn languages abroad; and he mastered in short course more books than any youngster since or before. He learned, too, to hunt, to ride with shield and lance, to play every known stringed instrument, and at fourteen, still with Curvenal, returned home.

However, he then was kidnaped to sea by merchantmen, who, when struck by a storm that tossed their ship for eight days, set him ashore alone in Cornwall, where the waif, arriving at Tintagel, so impressed the good King Mark with his skills that he became his unrecognized uncle’s chief huntsman, harpist, and companion. So it chanced — or rather, seemed to have chanced — that, as Gottfried, our poet, concludes this portion of his tale, “Tristan, without knowing it, arrived home yet thought himself astray; and noble, splendid Mark, the unsuspected ‘father,’ behaved to him right nobly.… Mark held him dear to his heart.”Note 42

III. Anamorphosis

The universally popular mythological theme known to folklore scholarship as infant exile and return carries in the legend of Tristan’s boyhood, as wherever it occurs, the inherent suggestion of a destiny unfolding — like a seed into flower — ineluctably, in the incidents of a life. In the love story of Tristan’s parents, on the other hand, there is no such evident mythic strain. Events are there presented in the manner of a naturalistic novel, as though determined only by chance. The unfoldment of the destinies follows — or at least appears to follow — upon the fall of outer circumstance. Yet we know that there, as here, all was predetermined in the author’s mind, and that what was read as substantial event was actually but a veil, a tissue of circumstance, conjured forth for the realization of a plot already formed.

Might the same be said of the circumstances of our lives?

As Schopenhauer cautions in his wonderful paper “On an Apparent Intention in the Fate of the Individual”: “Everything about such thoughts is questionable: the problem itself is questionable — let alone its resolution.”

Yet, as he then goes on to remark:

Everyone, during the course of his lifetime, becomes aware of certain events that, on the one hand, bear the mark of a moral or inner necessity, because of their especially decisive importance to him, and yet, on the other hand, have clearly the character of outward, wholly accidental chance. The frequent occurrence of such events may lead gradually to the notion, which often becomes a conviction, that the life course of the individual, confused as it may seem, is an essential whole, having within itself a certain self-consistent, definite direction, and a certain instructive meaning — no less than the best thought-out of epics.Note 43

On the naturalistic plane of Gottfried’s romance of Blancheflor and Rivalin, the self-consistent plot of the two lives that in their fate and meaning were at one became known, both to the reader and to the characters themselves, only a posteriori — through what appeared to be chance event; whereas in such a romance as that of Tristan and Isolt, resting frankly on symbolic, mythological forms, which emerge with increasing force as the narrative proceeds, the sense communicated is rather of the force of destiny in the shaping of a life, or, to use the old Germanic term, of wyrd (See The Word Behind Words here and here.).

Rationally, as Schopenhauer suggests,

The apparent plan of the course of a life might be explained, to some extent, as founded on the unchangeability and continuity of inborn character, as a consequence of which the individual is being continually brought back to the one track. For each recognizes so certainly and immediately whatever is appropriate to his own character that, as a rule, he hardly even brings it into reflective consciousness, but acts directly and, as it were, on instinct.…

However, if we now consider the mighty influence and immense power of outer circumstance, our explanation in terms of inner character will seem hardly strong enough. Furthermore, that the weightiest thing in the world — which is to say, the life course of the individual, won at the cost of so much effort, torment and pain — should receive its outer complement and aspect wholly from the hand of blind Chance — Chance without significance or regulation — is scarcely believable. Rather, one is moved to believe that — just as in the cases of those pictures called anamorphoses, which to the naked eye are only broken, fragmentary deformities but when reflected in a conic mirror show normal human forms — so the purely empirical interpretation of the course of the world resembles the seeing of those pictures with naked eyes, while the recognition of the intention of Fate resembles the reflection in the conic mirror, which binds together and organizes the disjointed, scattered fragments.Note 44

I should like to fix in mind here this analogy of the anamorphosis (the word is from the Greek μορφόω, “to form,” plus ἀνα “again”: ἀναμορφόω, “to form anew”). For it is a thought that will clarify much in the fields of modern literature and art — as, for example, James Joyce’s title Ulysses for a novel about the wanderings of a Jewish advertising broker round and about Dublin. The casual, chance, fragmentary events of an apparently undistinguished life disclose the form and dimension of a classic epic of destiny when the conic mirror is applied, and our own scattered lives today, as well, are then seen, also, as anamorphoses. Like Shakespeare’s mirror held up to nature, the symbols of myth bring forward into view that informing Form of forms which, through apparent discontinuity, is “manifest,” as the Upaniṣads declare, “yet hidden: called ‘Moving-in-secret.’” Primitive and Oriental thought is full of presentiments of this kind: on the crudest level, in the sentiment of magic and its force; more subtly, in the recognition of the force of dream and vision in the shaping of a life; and, most majestically, in such intuitions of a support not alone of the individual life, but of all things together, as in the following from the Muṇḍaka Upaniṣad:

That on which heaven, earth, and the space between are woven;

The mind, also, with the breath of life:

That alone know as the one spirit. All other

Talk dismiss. That is the bridge to immortality.Note 45

And in the Occident too we find such thoughts; as, for instance, in the romantic poet William Wordsworth’s celebrated “Lines Composed a Few Miles above Tintern Abbey, on Revisiting the Banks of the Wye During a Tour. July 13, 1798”:

For I have learned

To look on nature, not as in the hour

Of thoughtless youth; but hearing oftentimes

The still, sad music of humanity,

Nor harsh nor grating, though of ample power

To chasten and subdue. And I have felt

A presence that disturbs me with the joy

Of elevated thoughts; a sense sublime

Of something far more deeply interfused,

Whose dwelling is the light of setting suns,

And the round ocean and the living air,

And the blue sky, and in the mind of man:

A motion and a spirit, that impels

All thinking things, all objects of all thought,

And rolls through all things.Note 46

The sense experienced by lovers, already at the first meeting of the eyes, of having discovered in the world without the perfect complement of their own truth, and so of a marvelous coincidence thereby of destiny and chance, inner and external worlds, may, in the course of a lifetime flowering from such love, conduce to the poetic conviction of an accord universal of the seen and the unseen.

But of course, on the other hand, to those upon whom neither love, nature, nor symbol has ever bestowed any conic mirror, such romanticism is moonshine. Furthermore, as Schopenhauer states in his ruminating paper: “The view of an ordering Fate can always be countered by comparing the orderly design that we may imagine ourselves to have recognized in the scattered facts of our lives to the mere unconscious work of our own organizing and schematizing fantasy when we look at a spotted wall and see there, clearly and distinctly, human figures and groups — ourselves introducing the orderly connections into a field of spots scattered by blind chance.”Note 47

The modern reader will think of the Rorschach Test, with its inkblots in which different people see different forms, symptomatic of the psychology of their own fantasizing minds. And the world itself, it is said by some, is such an ink-blot, into which people read their own minds: the ordered universe, the great course of history and evolution, the norms of human life. There is a passage to this effect in Ulysses, in the scene where Stephen, in the library, is arguing a point with John Eglinton. “We walk,” Stephen states, “through ourselves, meeting robbers, ghosts, giants, old men, young men, wives, widows, brothers-in-love. But always meeting ourselves.”

Stephen Dedalus, in this conversation, has just quoted a line from Maeterlinck: “‘If Socrates leave his house today he will find the sage seated on his doorstep. If Judas go forth tonight it is to Judas his steps will tend.’” And he has applied the lesson of this solipsism to an interpretation of Shakespeare’s art, suggesting in turn that such creativity by projection is analogous to God’s creation of the world: “He found in the world without as actual what was in his world within as possible.”Note 48 In the micro-macrocosmic dream-novel Finnegans Wake, Joyce drops the plane of vision from the level of individuated consciousness to the unconscious — of the race: an interior “Land below Waves,” such as in one transformation or another, according to local influence, is common to mankind. However, in Ulysses, up to the moment, at least, of the great spell-dispelling thunderclap that occurs just halfway through the bookNote 49 (after which the two apparently distinct universes of Leopold Bloom and Stephen Dedalus gradually open to each other and display their common strains), the plane and point of view is strictly that of our common twentieth-century day-world of separate, self-preserving, self-assertive individuals; each the fragment of a general anamorphosis, to which none has found the conic mirror.

For, in fact, do we not have among us in abundance today a species even of philosophers who (maintaining in their own way the biblical notion of nature as corrupt) cannot discover in the nature either of man or of the universe any sign of inherent order? — to say nothing of a congruence of the two worlds, inside and out! Consider, for instance, Jean-Paul Sartre’s complaint that he “finds it extremely embarrassing that God does not exist; for there disappears with Him all possibility of finding values in an intelligible heaven.… Everything is indeed permitted if God does not exist, and man is in consequence forlorn; for he cannot find anything to depend upon either within or outside himself.… We are left alone, without excuse. That is what I mean when I say that man is condemned to be free.”Note 50

But on the other hand, at the opposite pole, there are those who believe that they know, can act upon, and can even teach — absolutely — the order in the mind of God for all mankind. They have learned it from the Bible or Qu'ran or, more passionately, through some hysterical “leap of faith” and pentecostal “decision” of their own. So, for example, in the journal of Søren Kierkegaard (1813–1855), just a century before Sartre:

The most tremendous thing that has been granted to man is: the choice, freedom. And if you desire to save it and preserve it there is only one way: in the very same second unconditionally and in complete resignation to give it back to God, and yourself with it.… You have freedom of choice, you say, and still you have not chosen God. Then you will grow ill, freedom of choice will become your idée fixe, till at last you will be like the rich man who imagines that he is poor, and will die of want: you sigh that you have lost your freedom of choice — and your fault is only that you do not grieve deeply enough or you would find it again.…

There is a God; his will is made known to me in Holy Scripture and in my conscience. This God wishes to intervene in the world. But how is he to do so except with the help of, i.e. per, man?Note 51

Between these two contending camps of uncompromising guessers, with their leaps and acts of faith in one direction or the other, there are those of a less dogmatic cast who are willing — like Schopenhauer and Wordsworth — to concede that, though one may indeed, in the contemplation of nature and one’s life, be filled, like Wordsworth, with “a sense sublime of something far more deeply interfused,” it is well and proper to remember that “everything in such thoughts is questionable,” and, as Schopenhauer states further: “decisive answers, consequently, are [in such matters] the last things to be expressed.”

Is a complete misadjustment possible [he asks], between the character and the fate of an individual? Or is every destiny on the whole appropriate to the character that bears it? Or, finally, is there some inexplicable, secret determinator, comparable to the author of a drama, that always joins the two appropriately, one to the other?

But this [he then goes on to reply] is exactly the point at which we are in the dark. And in the meantime we go on imagining ourselves to be, at every moment, the masters of our own deeds. It is only when we look back over the completed portions of our lives and review the unluckier steps together with their consequences that we marvel at how we could have done this, or have failed to do that; and it then may seem to us that an alien power must have guided our steps. As Shakespeare says:

Fate, show thy force; ourselves we do not owe;

What is decreed must be, and be this so!Note 52

Or as Goethe says in Götz von Berlichingen (Act V): “We men do not guide ourselves; wicked spirits are given power over us,

to work their naughtiness to our destruction.” And again, in Egmont (Act V, last scene): “Man imagines himself to be conducting his own life; and irresistibly his inmost being is drawn to its fate.” — Yes, and it was said already by the prophet Jeremiah: “A man’s deeds do not rest in his power; it rests in no man’s power, how he moves or directs his way” (1 0 :2 3) . Compare Herodotus I. 91 [“It is impossible even for a god to escape the decree of destiny”] and IX. 16 [“It is not possible for man to avert what God has decreed shall occur”]; see also Lucian’s Dialogues of the Dead X IX and XXX.

Indeed, the ancients never tire of insisting, in verse and in prose, on the power of fate and the comparative impotence of man. One can see everywhere that this was their overpowering conviction, and that they suspected a more secret, deep continuity in things than is evident on the clearly empirical surface. Hence the great variety of terms, in Greek, for this idea: πότμος [“that which befalls one”], ἆισα [“the divine dispensation of one’s lot”], εἱμαρμένη [“what is allotted”], εἱμαρμένη [“what is foredoomed”], μοῖρα [“one’s portion”], Ἀδράστεια [a name of the goddess Nemesis, goddess of divine retribution], and perhaps, also, many more. The word πρόνοια [“foresight, foreknowledge”], on the other hand, displaces our understanding of the matter: for it is derived from νοῦς [“mind, a thought, an act of mind”], which is the secondary factor, and though it makes everything clear and comprehensible, is superficial and false. — And this whole enigmatic circumstance is a consequence of the fact that our deeds are inevitably the product of two factors: one, our intelligible character, which stands unchangeably established, yet becomes known to us only gradually, a posteriori; and two, our motivations, which come to us from without, are supplied inevitably from the tides of world event, and with almost machinelike determinacy work upon our given character in terms of the limits and possibilities of its permanent constitution. — But then, finally, our ego judges the resultant event. In its role as the mere subject of knowledge, however,, it is distinct from both character and motivation and so is no more than the critical observer of their effects. No wonder if it sometimes marvels!

However, once one has grasped the idea of a transcendent fatality and has learned to contemplate the individual life from this point of view, one can have the sense, at times, of attending the most marvelous of all theatrical productions — in the contrast between the obvious, physical, accidental aspect of a situation and its moral-metaphysical necessity: the latter, however, never demonstrable and perhaps even, only imagined.Note 53

IV. The Music of the Land below Waves

In the context of the Tristan legend, the symbolic forms and motifs through which the intimation is communicated of a moving destiny and alien power (which, paradoxically, is a function of the character of the motivated individual) were derived—as we have seen—from the pagan Celtic lore of Ireland, Cornwall, and Wales. Inherent in them, consequently, was the old, generally pagan message of the immanent divinity of all things, and of the manifestation of this hidden Being of beings particularly in certain heroic individuals, who thus stand as epiphanies of that “manifest-hidden” which moves and lives within us all and is the secret of the harmony of nature. Such a figure was the Christ of the Gnostics. Such a figure was Orpheus with his lyre (Figure 3). The Celtic myths and legends are full of tales of the singers and harpers of the fairy hills whose music has the power to enchant and to move the world: to make men weep, to make men sleep, and to make men laugh. They appear mysteriously from the Land of Eternal Youth, the Land within the Fairy Hills, the Land below Waves; and though taken to be human beings — odd and exceptional, indeed, yet as self-contained, after all, as you or I (or, at least, as we suppose ourselves to be) — they are not actually so, but open out behind, so to say, toward the universe.

The Irish mythological trickster Manannan Mac Lir was a figure of this kind. Actually a sea-god — after whom the Isle of Man is named — it was he, we are told, who through his magic concealed from human eyes those fairy hills, the Sídhe (pronounced “shee”), within which the Celtic gods of old, the Tuatha Dé Danann, are feasting to this day on the inexhaustible flesh of his divine swine, washed down with his ale of immortality. Like the classical water-god Proteus, M anannan was an adroit shape-shifter; and he is recorded to have appeared in various deluding forms even as late as the sixteenth century, as, for instance, at a famous feast in Ballyshannon, where the host was the historical Black Hugh O’Donnell (d. 1537).

From nowhere, as it were, the wild old sea-god appeared at that feast in the semblance of a kern, or churl, wearing narrow stripes: “the puddle-water plashing in his brogues and a moiety of his sword’s length naked sticking out behind his stern, while in his right hand he bore three limber javelins of hollywood with firehardened tips.” The javelins three suggest the trident of Poseidon and the puddle-water in his brogues is another significant sign. Having challenged each of the four cunning harpers at the feast (who played, each and all, we are told, such harmonious, delectable, smooth-flowing airs that with the fairy spell of their minstrelsy men might well have been lulled to sleep), this kern cried out that, by Heaven’s graces three, such dissonance he had never heard this side the smoke-wrapped ground-tier of Hell, where the Devil’s artists, and Albiron’s, with their sledgehammers ding the iron. “And with that,” our document continues, “taking up an instrument, he made symphony so gently sweet, and in such wise wakened the dulcet pulses of the harp, that in the whole world all women laboring of child, all wounded warriors, mangled soldiers, and gallant men gashed about — with all in general that suffered sore sickness and distemper — might with the witching charm of this his modulation have been lapped in stupor of slumber and of soundest sleep. ‘By Heaven’s grace,’ exclaimed O’Donnell, ‘since first I heard the fame of them that within the hills and under the earth beneath us make the fairy music, that at one and the same time make some to sleep, and some to weep, and others again to laugh, music sweeter than thy strains I never have heard: thou art in sooth a most melodious rogue!’ ‘One day I’m sweet another I’m bitter,’ replied the kern.” And thereafter, presently, once again taking the instrument, he made melody of such kind and so befuddled the company, that all in fury arose in wrath and began to do battle with each other — when he disappeared.Note 54

Figure

36. Isolt Taught by Tristan to Harp

Figure 36 is another of the series of tiles from Chertsey Abbey, of a date about 1270. It is of the young Tristan teaching the maid Isolt to harp on the occasion of his first visit to Ireland: with the same harp and same music by which he had spellbound his uncle (Figure 4).

“Tristan, listen!” King Mark had said. “You have all the talents I yearn for. You do everything I wish I could do: hunt, speak languages, harp. Let us be companions: you, mine; I, yours. We shall ride hunting by day and by night enjoy courtly diversions — harping, singing, fiddling — here at home. You do all these things so well! Do them now for me. And for you I shall play the tune / know, for which perhaps your heart already yearns: magnificent clothes and horses. All that you want I shall give you, and with these serenade you well. See, my comrade, to you I confide my sword, my spurs, my crossbow and my golden drinking horn.”Note 55

Born of a widow, beyond the sea, who expired on giving him birth, Tristan had come, as it were, from nowhere. Tossed ashore from the storming waters, he had been born as from the womb of nature itself: the boy brought ashore by the dolphin, the pig of the sea. Miraculously, as it were, he had appeared with the power and glory of a god, yet in the character of a boy. Furthermore, the vessel in which he had been abducted from his birthplace beyond the waters (the yonder shore) had been a merchantman (ein kaufschif). Hermes, the guide of souls to rebirth, was the lord and patron of merchants — also of thievery and cunning.

The tale is to be recalled at this point of Hermes’ fashioning of the lyre when but an infant a couple of hours old. Conceived of Zeus, he had been born of a night-sky nymph named Maia (meaning “old mother, grandmother, foster-mother, old nurse, or midwife”; but also a certain large kind of crab). In a cave he had been born, at dawn; and toddling forth from his cradle before noon, he had chanced — or had seemed to chance — at the entrance of the cave upon a tortoise (an early animal symbol of the universe), which he broke up and fashioned into a lyre, to which at noon he beautifully sang. That evening he stole Apollo’s cattle, and to appease the god gave him the lyre, which Apollo passed to his own son Orpheus (Figure 3 and Figure 11). And, as the whole world knows, the sound of that lyre in Orpheus’s hands stilled the animals of the wilderness, moved trees and rocks, and even charmed the lord of the netherworld when the lover descended alive to the abyss to recover Eurydice, his lost bride.

Now, as already remarked in relation to the old Celtic god of the boar of Figure 23, Figure 27, and Figure 29, the ultimate roots of the tree of Celtic folklore and mythology rest deep in that megalithic culture stratum of Western Europe that was contemporary and in trade contact with the pre-Hellenic seafaring civilizations of Crete and Mycenae of which Poseidon was a mighty god, and from which the basically non-Homeric, Dionysian-Orphic strains of classical myth and ritual derived.Note 56 There is therefore an actual, archaeologically documented, family relationship to be recognized between the mythic harpists of the Celtic otherworld and those of the Orphic and Gnostic mysteries. Furthermore, as remarked in Primitive Mythology,Note 57 there is evidence as well of a generic kinship of the classical mystery cults not only with the grandiose Egyptian mythic complex of that dying god Osiris and the Mesopotamian of Tammuz, but also with those widely distributed primitive myths and rites of the sacrificed youth or maiden (or, more vividly, the young couple ritually killed embracing in a sacramental love-death),Note 58 whose flesh, consumed in cannibal communion, typifies the mystery of that Being beyond duality that lives partitioned in us all. The same idea is expressed mythologically in the Indian account, quoted in Oriental Mythology, of the first being, the Self, which, in the beginning, swelled, split into male and female, and so, begetting on itself all the creatures of this world, became this world.Note 59

The Indian god who is equivalent to Poseidon, and so to the Irish sea-god Manannan, is Śiva, who, as already seen, bears in his right hand the trident and in the Christian version of the netherworld is the Devil. He is known as the “Lord of Beasts” (paśupati),Note 60 also as the “Player of the Lyre” (viṇa-dhara); is, moreover, a phallic god and, as lord of the liṅgaṃ-yonī symbol, often shown united in one body with his goddess, she the left side, he the right. Gottfried’s metaphor of Tristan-Isolt as the two whose being is one is thus in India a familiar icon of the mystery of non-duality. Hermes, too, is both lord of the phallus and male and female at once. The word “hermaphrodite” (Hermes-Aphrodite) points to this secret of his nature. And with the goddess Aphrodite, of course, the inevitable associate is her child, the winged huntsman with his very dangerous bow: Roman Cupid, Greek Eros — the boy on the dolphin. Aphrodite too was born of the sea. And she is the consort, furthermore, of the ever-dying, ever-reborn god gored by the boar, whose celestial sign is the waning and waxing moon: the lord of the magic of night. So that Tristan, master of the arts of the hunt, as well as of music and all tongues, carried with him to Cornwall the powers of these gods.

To Mark he was to be as the young year to the old, or as David to Saul (Figure 4). He was the young god destined to supplant the old in possession of the queen, who in the ritual lore of the old Bronze Age tradition was symbolic of the land, the realm, the universe itself, and in the language of the later Hellenistic mystery cults became the guide and symbol of the interior kingdom of the soul: that realm of the spirit which can be found and fertilized only through death, humiliation, and a submission of the solar principle of rational self-reliant consciousness to the song, the sleep-song, of the interior abyss where the two — the male and female — become one (Figure 5, at Station 11). We may think also of those bull-bodied harps that were found in the royal tombs of Ur, the music they sang of the harmony of the universe, and the love-death there celebrated of the goddess and god of the deep: Inanna and Dumuzi-absu, Ishtar and Tammuz.Note 61

There is the fragment of an episode from a lost, early version of the Tristan legend preserved in a Welsh triad, which opens a fresh prospect into the mythological background of Tristan in relation to Isolt, as follows:

Trystan son of Tallwch, disguised as a swineherd,

Tended the pigs of Marc son of Meirchyon

While the [true] swineherd went with a message to Esyllt.Note 62

One discovers here, first, that the father of the hero is named not Rivalin but Tallwch. Tracing the history of the legend back through its Breton, Cornish, Welsh, and Irish phases, the leading Celtic scholar of the last century, Dr. H. Zimmer (As noted in Occidental Mythology, H. Zimmer (1851–1910) is not to be confused with his son of the same name, the distinguished Sanskritist, Heinrich Zimmer (1890–1943), whom I have cited in Oriental Mythology. To prevent confusion, I designate the elder as H. Zimmer and the younger as Heinrich Zimmer.), discovered that in the Pictish marshlands of southern Scotland, from the sixth to ninth centuries a.d., there had actually been a reigning series of kings named Drustan alternating with a series named Talorc, of which the member reigning from 780 to 785 was the Drustan son of Talorc of the earliest — and now forever lost — version of our legend.Note 63 Drustan son of Talorc became, in Wales, Trystan son of Tallwch, and the name Rivalin was substituted only when the romance reached Brittany after c. 1000, where it received its final form.

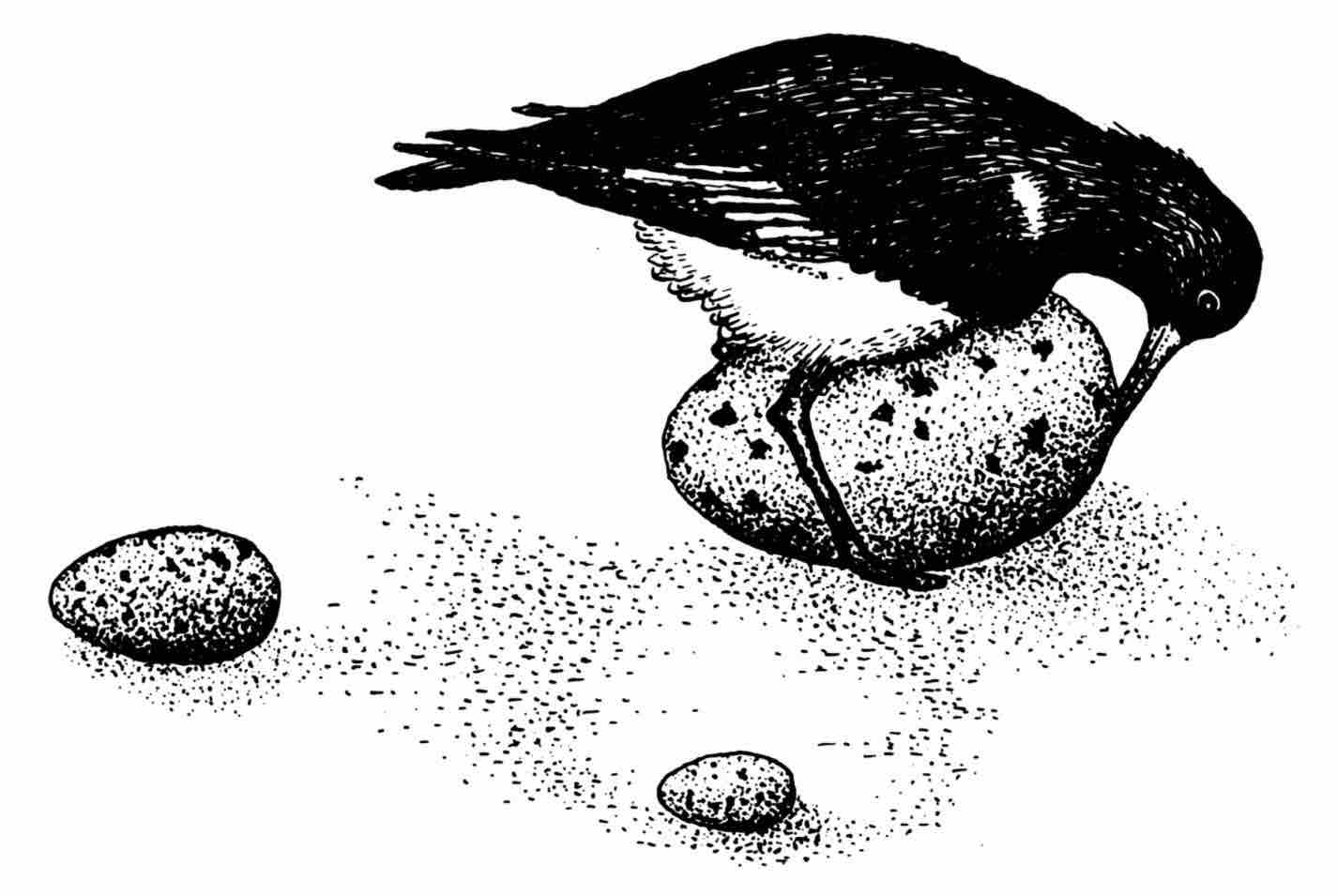

The episode of the lover, masquerading as Mark’s swineherd, sending his message by the real swineherd to Mark’s queen, which is otherwise unknown to the Tristan cycle, suggests very strongly the legend, registered in Primitive Mythology, of the abduction of Persephone to the netherworld by Hades, where it is told that a herd of swine went down too, when the earth opened to receive her.Note 64 Significantly, the name of the swineherd of that lost herd was Ebouleus, “Giver of Good Counsel,” an appellation of Hades himself; and, as Frazer in The Golden Bough points out, Persephone, in her animal aspect, was a pig.Note 65 Or again: in the Odyssey there is that episode of the magic isle of Circe, who, when she returned Odysseus’s men to their former shapes (and they were younger and fairer than before), took Odysseus to her bed, after which she led him to the netherworld, where he met and talked with — among others of the living dead — the male-female sage Tiresias (once again Figure 5, Station 11). In the general body of Celtic folklore the classical legend of the pig-goddess-guide to the mysteries beyond the plane of death is matched by the Irish folktale, retold in Primitive Mythology and noted a few pages back, of the Daughter of the King of the Land of Youth whose head was the head of a pig. When she appeared on earth and attached herself to Finn McCool’s son Ossian, he kissed the pig’s head away and became the King of the Land of Youth.Note 66

Gottfried’s vision of Tristan as a wild boar ravaging King Mark’s bed, the Welsh triad of his role as Mark’s pretended swineherd, and the legend of the scar on his thigh all point in the same direction: to his derivation ultimately from the Celtic-megalithic god of the boar with the eyes of the Great Mother engraved along either side (Figure 27), who, as lord of the wilderness, the underworld, and the vital force of nature, was also king of the Land below Waves and the music-master of its spell.

But, on the other hand, King Mark appears to have been associated with a totally different mythic context, as contrary as the day to night, or as the world of fine clothes and horses to that of harping, fiddling, singing, and the lore of love and the moon. For whereas Tristan, as we have just seen, was originally a Pictish, pre-Celtic king of a Bronze Age matrilineal folk — possibly with memories of ritual regicide not distant in its past — and whereas Queen Isolt, as a legendary daughter of pre-Celtic Ireland, of the breed somewhat of Queen Meave,Note 67 was likewise of a matriarchal line; King Mark — known also, in Wales, as Eochaid — seems to have been a Celtic king of Cornwall of about the period of Drustan/ Tristan (c. 780–785 a.d.), whose legend, on entering Wales some time before the year 1000, became combined with that of the other two — in a relation generally comparable to that of the Celtic warrior-prince Ailill to Queen Meave.

His name, Marc, is understood usually as an abridgment of the Latin Marcus, from the name of the war-god Mars. It may also bear some relation, however, to the Middle High German marc, meaning “war-horse,” Welsh march, old Irish more or margg, “stallion or steed”; and this alternative is supported by his other Celtic name, Eochaid, which is related to the old Irish ech, Latin equus, meaning “horse.” Moreover, in one old French version of the romance (by the continental Norman poet Beroul, c. 1195 — 1205 a.d.) we find the following startling statement:

Marc a orelles de cheval,

“Mark has horses’ ears.”Note 68 And with this we are suddenly dropped into an extremely suggestive vortex of both mythological and high historical associations.

V. Moon Bull and Sun Steed

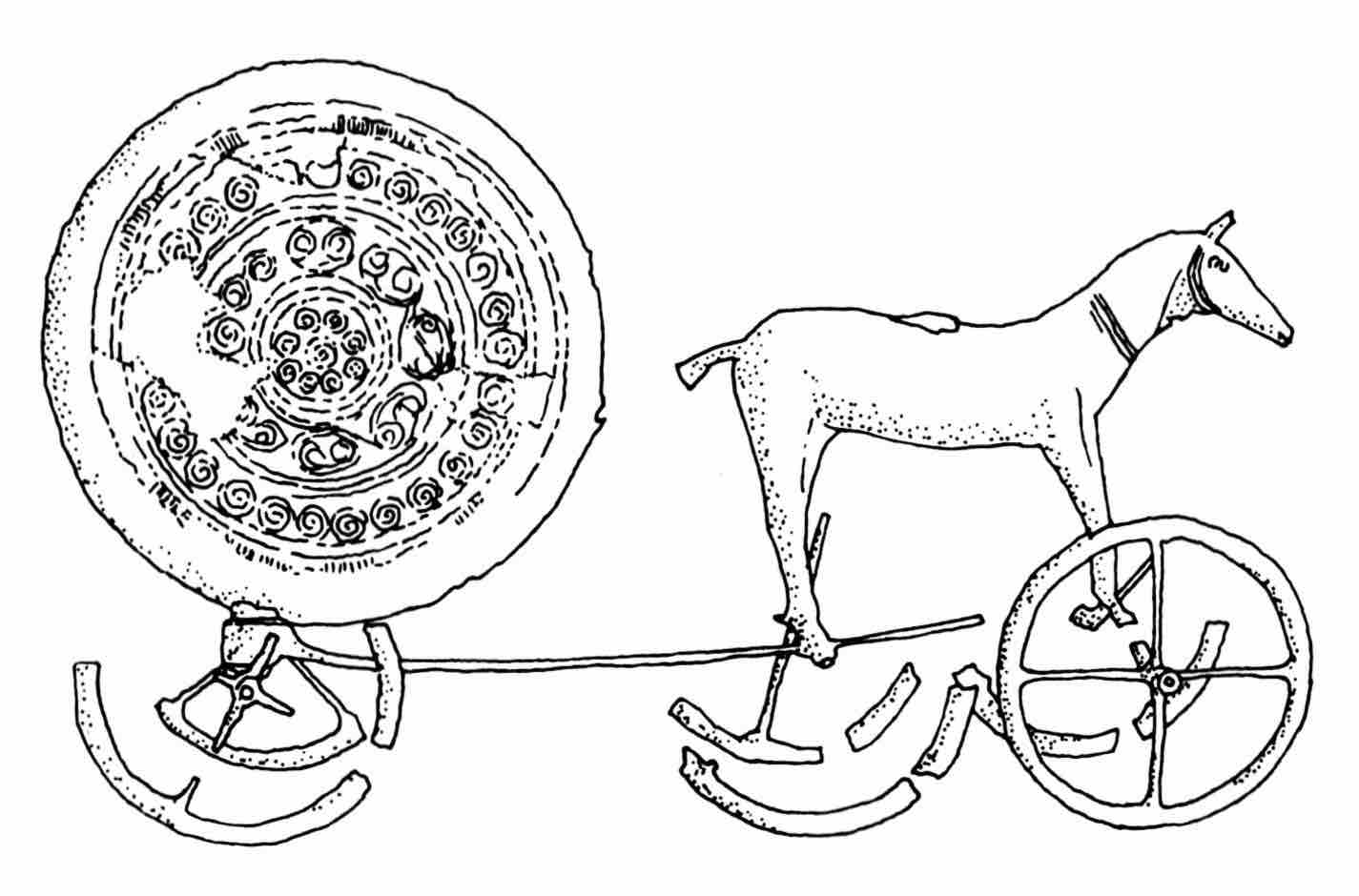

Figure

37. Bronze Solar Horse and Car (bronze, Denmark, c. 1000

b.c.)

Figure

38. Sun Steed and Eagle (silver, France, Gallo-Roman

Period)

We think first of the classical legend of King Midas, who had ass’s ears and whose touch turned everything, including his daughter, into gold, the metal of the sun; recall, too, that the leaders of the Anglo-Saxon invasion of Britain (c. 450 a.d.) were Hengest and Horsa, both of which names are from Germanic nouns meaning “horse.” Figure 37 is a bronze solar disk ornamented with a gold design of spirals, set on wheels of bronze, and with a bronze steed before it, found at Trundholm, Nordseeland, Denmark (whence Hengest and Horsa came), and usually dated c. 1000 b.c.; while in Figure 38 are a couple of late Gaulish coins showing horses, each with an eagle (sun-bird) on its back, and in one the horse has the head of a man. We know that annually in Rome in October a horse was sacrificed to Mars, and that at midsummer both Celts and Germans sacrificed horses. In Aryan India the high “horse sacrifice” (aśva-medha) was a rite reserved for kings, where, as seen in Oriental Mythology,Note 69 the noble animal was identified not only with the sun but also with the king in whose name the rite was to be celebrated; whose queen then had to enact in a pit a ritual of simulated intercourse with the immolated horse: all of which gave to her spouse the status of a solar king whose light should illuminate the earth. And, more remotely, there is the kindred legend of the birth of the beloved Japanese prince Shotoku (573–621 a.d.) while his mother was inspecting the palace precincts. “When she came to the Horse Department and had just come to the door of the stables, she was suddenly delivered of him without effort.”Note 70

It is almost certain, in the light of these facts, that the association of King Mark with a horse, and even horse’s ears, testifies to an original involvement of his image in a context of royal solar rites, the warrior rites of those Celtic Aryans who, with their maleoriented patriarchal order, overran in the course of the first millennium b.c. the old Bronze Age world of the Mother Goddess and mother-right. The composition of the coin of Figure 38 in which a human-headed horse leaps over a bull as the sun leaps over the earth suggests the relationship of the two orders of the conquerors and conquered in that early Celtic heroic age; and when these figures are compared with those of Pablo Picasso’s “Guernica” (Figure 39), where a horse and its rider lie shattered and a bull stands mighty and whole, the beginning and end are seen illustrated, in a remarkably consistent way, of the long majestic day in Europe of the conquering cavalier and his mount.

Oswald Spengler, in his final published work, Years of the Decision (published 1933), delineated in two bold paragraphs the whole reach of this great day, of which we are now in the twilight hour:

In the course of world history, there have been two great revolutions in the manner of waging war produced by sudden increases in mobility. The first occurred in the early centuries of the first millennium b.c., when, somewhere on the broad plains between the Danube and Amur rivers, the riding horse appeared. Mounted hosts were vastly superior to men afoot.* The riders could appear and disappear before a defense or pursuit could be assembled. It was in vain that populations, from the Atlantic to the Pacific, supplemented their foot forces with mounted contingents of their own: the latter were hindered in maneuvers by the footmen. Nor were the Chinese and Roman empires saved by the building of walls and moats: such a wall as can be seen to this day cutting half across Asia; or such as the Roman limes recently discovered in the Syro-Arabian desert. It was impossible to send an assembled army out from behind such barriers quickly enough to break up a surprise attack. The settled agrarian, peasant populations of the Chinese, Indian, Roman, Arabian, and West European spheres were, time and again, overwhelmed, in helpless terror, by swarms of Parthians, Huns, Scythians, Mongols, and Turks. Cavalry and peasantry, it is apparent, are in spirit irreconcilable. It was in this way, to their superior speed, that the hosts of Jenghis Khan owed their victories.

The second decisive transformation, we are witnessing at this very hour in the displacement of the horse by the “horse power” of our Faustian technology. As late as through the [First] World War there hung about the famous old West European cavalry regiments an atmosphere of knightly pride, daring adventure and heroism, which greatly surpassed that of any other military arm. These had been, for centuries, true Vikings of the land. They came to represent more and more — much more than the infantries of the general armies — the true sense of vocation of the dedicated soldier’s life and military career. In the future all this will change. Indeed, the airplane and tank corps have already taken their place, and mobility has been carried with these beyond the limits of organic possibility to the inorganic range of the machine: of (so to say) personal machines, however, which, in contrast to the impersonality of the machine-gun fire of the trenches of the [First] World War, now will again challenge the spirit of personal heroism to great tasks.Note 71

Figure

39. Adapted from Pablo Picasso: Guernica: 1937

In Picasso’s “Guernica,” the glaring electric bulb is the only sign of the new order of power and life by which the old is being destroyed: the old, of the barnyard bull and the warhorse, peasantry and cavalry. The shattered steed, the once conquering vehicle of the day of history now ending, appears to have been pierced by the lance of its own rider, as well as gored by the bull. The lance wound is a reference, obviously, to civil war: the Spanish Civil War of 1936–1939, during the course of which, in April 1937, the Basque town of Guernica was bombed. But the Basque race and language are pre-Aryan. They represent, thus, like Drustan’s Picts, a period of history antecedent to the day and people of the horse. They typify and represent even to this present hour the patient spirit of those long, toiling millenniums of the entry into Europe and establishment there of its basic peasant population: when the myths and rites of the sacrificial bull — symbolic of the everdying, self-resurrecting lord of the tides of life, whose celestial sign is the moon — were the life-supporting forms of faith and prayer. In the bull ring, from which Picasso took his imagery, the old wornout picador-horse is gored by the bull, but the bull itself is then slain by a solar weapon — the sword of the matador, who is clothed in a garment called “the garment of light.” In Picasso’s work there is no such avenger: the enigmatic bull still stands. The day of the cavalier is ended; and tracing back now through the centuries, to identify the symbolic moments of its beginning, culmination, climacteric, and dissolution, we may number the stages of this culture period as follows:

- The long, general period represented by the coins of Figure 38, of the pagan Aryan beginnings of what today is Occidental civilization: the centuries, first, of the Celtic (Hallstatt and La Tene) expansions, raids, and invasions, c. 900–15 b.c., and then, of the rise and world empire of pagan Rome, c. 400 b.c.–400 a.d.Note 72