31

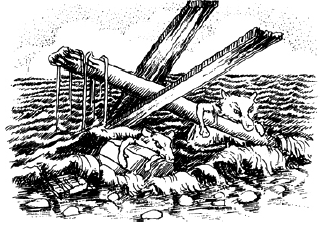

Dawn broke hot and warm over a sheltered inlet on the northwest coast of Sampetra. The ebbing tide had thrown up some flotsam from the vessel Bloodkeel. Still intact, the rudder and tiller lay among the shells and seaweed festooning the tideline. Lashed to it by a heaving line were Rasconza the fox and his steersrat Guja. Pounded and battered by the seas, they coughed up salt water as they extricated themselves from the ropes, tiller and rudder that had kept them alive for almost two days on the ocean. The pair dragged themselves painfully over the shore, into the shadow of a rock overhang at the foot of a hill. There they found fresh water.

Greedily the two corsairs lapped at the tiny rivulet of cold, crystal-clear liquid that threaded thinly and dripped from the mossy underside of their shelter. Rasconza picked salt rime from his eye corners, gazing beyond the cove, out to where the deep ocean glimmered and shimmered in early morn.

The fox’s voice was rasping and painful, bitter and vengeful. “A full crew, matey, an’ we’re the only two left alive t’tell the tale!”

Guja had scraped some of the damp moss off with his dagger. He chewed it until there was no more moisture or nourishment left, then spat it out viciously. “Aye, Cap’n, all our shipmates, either drowned or eaten by the big fishes, every beastjack o’ them slain by Mad Eyes’ treachery!”

Rasconza unbuckled the saturated belt that held his daggers, and laid the weapons out one by one on the grass. Selecting his favorite blade, he began honing it on a piece of rock. “Mark my words, Guja, the worst day’s work Ublaz ever did was to leave me alive. Though he don’t know it, his dyin’ day is near!”

As Chief Trident-rat, it was Sagitar’s duty to report to her Emperor morning and night. As she entered the pine marten’s throne room, Sagitar could see that Ublaz was in a foul mood. He slumped on his throne staring at the lifeless form of Grall, his messenger gull. The great black-backed bird had died of exhaustion bringing news back to its master.

Ublaz touched the limp wing feathers contemptuously with his footpaw. “Hah! Grall was the only one of my gulls to make it back, and now look at him—useless bundle of birdflesh!”

In the silence that followed, Sagitar shuffled nervously. Feeling it her duty to make some comment, she enquired meekly, “Did the bird bring good news of your pearls, Sire?”

Ublaz rose and, stepping over the dead gull, he stared out of the wide chamber window at the ocean beyond. “Lask Frildur and Romsca are sailing back to Sampetra. They didn’t get the pearls. Instead they’re bringing the Father Abbot of Redwall Abbey as a hostage—the Tears of all Oceans are to be his ransom. What d’you think of that?”

Sagitar’s voice was apprehensive as she answered, “Well, at least you have something to bargain with, Sire . . .”

Ublaz whirled upon her, his eyes blazing angrily. “Bargain? I am Ublaz, Emperor of Seas and Oceans. I take! Twice my creatures have failed me. Twice! If I had gone after the pearls myself in the first place I would have them now, set in my new crown! There will be no more bargaining or playing of games. When that ship drops anchor here, we will sail again back to the land of Mossflower and Redwall Abbey—all of my ships and every creature on this island. That way there will be none left behind to seize power and plot behind my back. I will lead everybeast, Monitors, Trident-rats and corsairs, against Redwall. I will smash it stone from stone and rip those pearls from the wreckage. The ruins of that Abbey will remain as a marker to the deadbeasts that lie beneath them—the ones who tried to defy the might of Ublaz!”

Romsca ushered Abbot Durral into her cabin. With a few swift slashes of her sword she released him from his rope shackles. The corsair ferret sat Durral upon her bunk, issuing him with a beaker of seaweed grog and some hard ship’s biscuit.

The old mouse sipped at the fiery liquid, squinting without his eyeglasses as he stared curiously at Romsca.

“Why are you helping me like this, my child?”

Romsca sheathed her cutlass blade firmly. “I ain’t yore child, I keep tellin’ yer, an’ I ain’t doin’ this to ’elp you. ’Tis more fer my benefit you be kept alive. We’re sailin’ into bad cold weather, you wouldn’t last a day out on deck. Sit tight in ’ere an’ keep the door locked, d’ye hear?”

Abbot Durral smiled warmly at the wild-looking corsair. “You are a good creature, Romsca. What a pity you chose the life of a corsair.”

Romsca stood with one paw on the doorlatch. “It ain’t none o’ yore business wot I chose ter be,” she said harshly. “’Tis a long hard story ’ow I come t’be wot I am. Any’ow, I likes bein’ a corsair an’ I ain’t ashamed o’ my life. Now you stay put, ole Durral, an’ don’t open this door to none but me. I don’t trust that Lask Frildur no more, he’s got a crazy look in ’is eyes of late.”

Slamming the cabin door, Romsca went aft. The weather was cold and the seas a slate gray. She faced for’ard and peered anxiously; the wind was dropping, a deep fogbank was looming up, and ice was beginning to form on the rigging. Turning, she looked aft, scanning the waters in the ship’s wake. Somewhere out along the eastern horizon Romsca thought she saw a small dark dot. She blinked and looked again, but she had lost the location of the dot owing to the ship’s movement on the oily waveless swell. A slithering sound behind Romsca caused her to turn swiftly, paw on swordhilt. Lask Frildur was standing there watching her. Though he looked cold and seasick there was a crafty glimmer in the Monitor General’s eyes.

“Where have you hidden the Abbotmouze, Romzca?” he hissed.

Romsca drew her cutlass and circled until the lizard was backed to the stern rail. She pointed the blade at him. “Never you mind about the Abbot, I’m takin’ charge o’ him. Keep yore distance, Lask, or I swear I’ll spit yer on this blade!”

Lask flicked his tongue at the corsair ferret. “Lzzzt! Food iz running low, weather iz growing colder, you have got uz lozt again.”

Romsca stared contemptuously at the Monitor. “Vittles is as short fer me’n’my crew as they are fer you an’ yore lizards. As fer the weather—well, it’ll get colder afore we’re out o’ these waters, an’ if you think I’ve got ye lost then yore welcome to navigate fer yerself. Other than that, you stay out o’ my way an’ don’t start any trouble that y’can’t finish.”

Lask stayed leaning on the rail, shivering, but still smiling slyly. “When I ztart trouble, Romzca, you will be the firzt to know!”

The longboat with the outriggers on either side of it bobbed and swayed as Welko the shrew slid down from the masthead. Grath helped him to the narrow deck.

“Well, was it the corsair ship you saw to the west?” she asked.

Welko drew his cloak against the cold. “I’m not sure. I thought I saw a sail, then I lost sight of it. There could be fog ahead, mayhap she’s sailed into it.”

Clecky was seated aft, guarding a small cooking fire he had made on a bed of sand surrounded by slate. The lanky hare had taken to being very nautical. “Ahoy there, me heartychaps, grub—er, vittles are about ready,” he called out to everyone. “I say, Plogg old cove, nip over into the larboard shrewboat an’ dig out a few apples, will you, there’s a good ol’ barnacle, wot?”

The two shrewboats that served as outriggers to the longboat were loaded with supplies; Martin had made space in the starboard one for Bladeribb, their searat captive. The searat stared sullenly at Plogg as the latter climbed across to the far logboat. The shrew rummaged through the ration packs before calling back to Clecky, “There’s not many apples left!”

Grath glared across at Bladeribb. “Have you been sneakin’ across at night an’ stealin’ apples?”

Martin patted Grath’s broad back. “No, he’s been right there all along, I’ve kept my eye on him. Clecky, you haven’t been pinching the odd half-dozen apples, have you?”

The hare’s ears stood up with indignation. “Er, d’you mind belayin’ that statement, ol’ seamouse, I haven’t touched a single apple. Hmph! Bally cheek of some crewbeasts. Take a proper look over there, I’m sure you’ll find heaps of jolly ol’ apples rollin’ about somewheres, wot!”

Plogg began turning the packs over and checking them. Suddenly he gave a shout of alarm as he rolled back a crumpled canvas cover. Drawing his sword, Martin leapt aboard the logboat, only to find Plogg wrestling with a kicking, screaming Viola bankvole.

Martin caught her sharply by the ear. “What in the name of thunder are you doing here, miss? I told you to go back to the Abbey. You could have been drowned or injured or . . . or . . . How did you manage to stow away on this logboat, and what happened to Jesak and Teno?”

Viola wriggled free of the warrior’s grasp and skipped nimbly over to the longboat, where she hid behind Clecky, shouting, “I gave them the slip and doubled back and stole aboard while you were all drinking and naming the boat. I wasn’t drowned or injured, see! Told you I was going to help rescue Father Abbot, didn’t I! Well, what’re you going t’do now? You can’t turn back or throw me overboard!”

Grath Longfletch grinned and winked at the volemaid. “Yore right there, young ’un. My, yore a peppery one an’ no mistake. Looks like we’re stuck with you.”

Clecky looked over his shoulder, viewing the stowaway sternly. “You’re lucky we aren’t searats or those corsair bods, m’gel, or we’d have chucked you overboard to the fishes just t’save feedin’ you, wot!”

Martin shook his head in despair as he gazed at the defiant volemaid. “Think of the distress you’ve caused Mother Auma and all your friends back at the Abbey. They probably think you’re still a prisoner aboard that ship with the Abbot. If you’d gone back to Redwall as I told you, it would have saved a load of worry for everybeast who cares what happens to you, miss!”

The sudden realization of what she had done caused tears to flood down Viola’s cheeks, and she hung her head in shame.

Martin could not bear to see a young creature so unhappy. He patted the volemaid’s head gently. “There, there, now, don’t cry. Your motives were good and I know you were only trying to help. Welcome aboard, Viola. Come on, smile, and we’ll try to make the best of it.”

They dined on toasted cheese and hot shrewbread, half an apple apiece and some oat and barley cordial. Martin carried a plateful across to Bladeribb; the searat was quite comfortable, wrapped in a cloak and a blanket.

The warrior once again questioned his captive. “Could that have been the vessel Waveworm that Welko sighted earlier? Are we on the right course?”

The searat grabbed his plate of food, nodding. “Aye, that’ll be ’er. You’ll be sailin’ into wintry seas now, cold an’ dangerous, fog an’ ice. If’n we gets through it you’ll prob’ly sight ’er agin in the good weather. She’ll be ’eaded due west toward the settin’ sun, like I told yer.”

Martin caught the searat’s paw as he was about to eat. “Play me false just once, Bladeribb, and I’ll slay you. Is that clear? Steer us true if you want to stay alive.”

The searat shrugged. “I’m bound t’die sooner or later, if not by your paw, then it’ll either be Lask Frildur or Ublaz Mad Eyes for allowin’ meself t’be taken captive.”