This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either products of the author’s imagination or, if real, are used fictitiously.

Text copyright © 2010 by Rosemary Wells

Illustrations copyright © 2010 by Bagram Ibatoulline

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, transmitted, or stored in an information retrieval system in any form or by any means, graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, taping, and recording, without prior written permission from the publisher.

First electronic edition 2010

The Library of Congress has cataloged the hardcover edition as follows:

Wells, Rosemary.

On the Blue Comet / Rosemary Wells ; illustrated by Bagram Ibatoulline.

— 1st ed.

p. cm.

Summary: When the Depression hits in Cairo, Illinois, and Oscar Ogilvie’s father must sell their home and vast model train set-up to look for work in California, eleven-year-old Oscar is left with his dour aunt, where he befriends a mysterious drifter, witnesses a stunning bank robbery, and is suddenly catapulted onto a train that takes him to a different time and place.

ISBN 978-0-7636-3722-4 (hardcover)

[1. Space and time — Fiction. 2. Railroad trains — Fiction.

3. Single-parent families — Fiction. 4. Depressions — 1929 — Fiction.

5. Adventure and adventurers — Fiction.

6. California — History — 1850–1950 — Fiction.

7. Illinois — History — 20th century — Fiction.]

I. Ibatoulline, Bagram, ill. II. Title.

PZ7.W46843Om 2010

[Fic] — dc22 2009051358

ISBN 978-0-7636-5419-1 (electronic)

Candlewick Press

99 Dover Street

Somerville, Massachusetts 02144

visit us at www.candlewick.com

Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

If

If you can keep your head when all about you

Are losing theirs and blaming it on you,

If you can trust yourself when all men doubt you,

But make allowance for their doubting too;

If you can wait and not be tired by waiting,

Or, being lied about, don’t deal in lies,

Or, being hated, don’t give way to hating,

And yet don’t look too good, nor talk too wise;

If you can dream — and not make dreams your master;

If you can think — and not make thoughts your aim,

If you can meet with Triumph and Disaster

And treat those two impostors just the same;

If you can bear to hear the truth you’ve spoken

Twisted by knaves to make a trap for fools,

Or watch the things you gave your life to broken,

And stoop and build ’em up with worn-out tools;

If you can make one heap of all your winnings

And risk it on one turn of pitch-and-toss,

And lose, and start again at your beginnings

And never breathe a word about your loss;

If you can force your heart and nerve and sinew

To serve your turn long after they are gone,

And so hold on when there is nothing in you

Except the Will which says to them: “Hold on”;

If you can talk with crowds and keep your virtue,

Or walk with kings — nor lose the common touch;

If neither foes nor loving friends can hurt you;

If all men count with you, but none too much;

If you can fill the unforgiving minute

With sixty seconds’ worth of distance run,

Yours is the earth and everything that’s in it,

And — which is more — you’ll be a Man, my son!

Rudyard Kipling

We lived at the end of Lucifer Street, on the Mississippi River side of Cairo, Illinois. Black spruces lined our sandy road. My heart quickened as I watched my dad lope home over the fallen needles. Bouncing along on his shoulder was a red cardboard box labeled LIONEL COMPANY, ROCHESTER, NEW YORK. In that box was my birthday present, the Blue Comet. The Blue Comet was the queen of all trains.

I waited for him under the porch light. The forty-watt yellow bulb made a Grand Central Station for flapping moths and zizzing june bugs above my head. In the kitchen, our dinner was warm and fragrant on the stove.

The house at the end of Lucifer Street had been my mama’s great joy. She fixed it up so pretty when I was just a baby, all yellow curtains and shiny white trim. We have a lone portrait, its edges curled, of me, Dad, and Mama. I was just a skinny, freckled little boy of three in that Brownie camera snapshot, with a cowlick pointing straight up out of the top of my head.

Mama was the bookkeeper in the Lucifer Fireworks plant until one day a bolt of walking lightning shot right through the shipping-room window, stopping the clock and sizzling into a box of Roman candles near her chair. Everyone would say afterward she had not known or felt a thing in that half-second explosion. All I remember seeing was a fire truck out the window of our kitchen and my aunt Carmen, who had appeared from nowhere, covering my eyes with her hands.

What was left of the Lucifer factory was declared unsafe and closed down soon after. You might think my dad would want to move away from Lucifer Street and the terrible reminders of the accident. But in the end he could not bear to leave the yellow curtains and white trim that Mama had painted herself. He certainly did not wish to move into the Chateaux Apartment Village as Aunt Carmen, his in-town sister, suggested. Aunt Carmen was always telling Dad what he ought to do.

“Get your life back on the tracks and find a good woman, Oscar,” Aunt Carmen whispered loudly to Dad every time she had the littlest chance. “The boy needs a mother, and you need a wife to keep your hair short and make you some casserole dinners.”

“That goes double, Carmen,” my dad always replied. Aunt Carmen lived alone in a little house full of bisque figurines. Squirrel silhouettes were cut into the house’s shutters. It was explained to me that Aunt Carmen had never married because the Great War had taken the lives of so many young men that there were not enough to go around.

“A good man is a darn sight harder to find than a good woman,” Aunt Carmen always answered my dad with a sniff.

Oftentimes a picture floated through my mind of the wife that Aunt Carmen had in mind for us. She looked like the lady on the Coca-Cola calendar, black hair parted on the side, dress with the stripes going across diamond-wise, big red lips showing off her white teeth.

“I will never be so lucky again as to find anyone like your mother,” Dad said. “A new wife would make trouble and get in the way.” What he meant was she would have gotten in the way of the trains in our basement.

Instead Dad and I lived a peaceful life, with me, Oscar Jr., in charge of cooking just as soon as I could reach the stove. In second grade, I was big enough, standing on a sturdy chair, to flip our Sunday pancakes and fry our breakfast sausage. Our weekly menu was casserole-free.

This is what it looked like:

Monday: Lamb chops and fried potatoes

Tuesday: Fried chicken, canned green beans, fried potatoes

Wednesday: Hamburger, fried potatoes, and tomatoes

Thursday: Hot dogs and beans

Friday: Beefsteak and carrots

Saturday: Pork chops and cabbage

Sunday: Ham and gravy with pineapple rings

The menu never changed from week to week because it satisfied. There was just enough variety to keep us from getting bored but nothing like liver or spinach to scare us away.

I bought all our groceries at Rubin’s Market after school, charging them to our account. Then I walked the groceries home, set them on the counter, and began to prepare our evening meal.

We did just fine on our own, Dad and me. Dad had a steady job with the John Deere Company, selling tractors to the farmers. He even had a telephone installed right in the front hall, much to the dismay of Aunt Carmen. For my part, I kept my shoes shined, and my homework was always finished. Dad and I agreed: we had no need whatever of a new wife. So that wife never did happen. It was just as well. A wife would have been putting on her lipstick all the time and giving me cod-liver oil.

In the beginning, Dad had set up our first layout to pull himself out of the widower doldrums. It was a simple one-looper. He made the station out of basswood, painted pumpkin yellow just like the real railway station in downtown Cairo. He cut eight little signs and painted them white with CAIRO in blue, just as it was on the real signs. I hung them off the eaves of the station’s shingled roof with chrome-beaded key chains. We laid eastward tracks and westward tracks. The track beds were made of carefully dribbled bird gravel on a layer of carpenter’s glue.

Then Dad ordered signals and an electrically operated gate out of the Lionel catalog to go with our first train, a standard work train. Dad took a sable brush that had maybe six hairs to it. He painted SOO LINE HAPPY WARRIOR on the side of the engine in red paint, exactly like on the real Soo Line. Our Happy Warrior had a lumber car with logs as long as cigarillos, two cattle cars, a coaler, a caboose, and a refrigerator car that had small cubes of glass ice inside, each no bigger than one of my Parcheesi dice.

The Warrior was followed by a commuter train, which we called the South Shore Special. We ran it from Chicago to the dunes of Indiana and back. The passenger cars were rigged with real electric lights inside. We put together three stop stations on that commuter express. They came from the Ives Company, which made the most detailed stations.

Then Dad bought us the biggest steam engine in the catalog. It was a 260 series with marker lights on each side, one red, one green. There was a red light underneath the boiler that made the coals glow. The trim was copper and brass, the wheels had spoked drivers with nickel rims. It carried freight cars and three passenger Pullmans. We named it the Choctaw Rocket of the Rock Island Line. Our first tabletop layout was now too small. We began constructing the mountains of the west, lumping up their foothills out of stiff window screening. We layered plaster of paris on top of that, and then we painted it granite gray. This was sprinkled with sand, glue, and a green mystery powder provided by the Cairo druggist, Hop Shumway.

“You’re not going to swallow this stuff, are you, Oscar?” Hop Shumway asked my dad, pushing a box of the green powder across the drugstore counter.

“On the contrary, Hop,” Dad answered. “We’re going to make the Transcontinental Railroad,” and we did.

The benchwork for the mountains, canyons, and bridges that ran between was constructed of wooden crossbeams, like the criss-cross supports of a roller coaster. A tunnel ran through the mountains. The river that coursed under the trestle bridge was painted blue over silvery tinfoil. The ripples were transparent lines of model airplane glue. The tracks shot down the length and a whole side of our basement. Soon we had two tables and three tunnels.

“You are stark raving crazy, Oscar,” Aunt Carmen said when she came to Thanksgiving dinner and asked what was in the basement that smelled of shellac. My cousin, Willa Sue, donkey’s years younger than me, gazed at the layout in bewilderment.

“Don’t touch anything. You might get electrocuted, Willa Sue,” said Aunt Carmen.

“I can show you how the trains run,” I said to Willa Sue encouragingly, even though I didn’t like her much. Willa Sue had come to Aunt Carmen from a sister who was almost never mentioned. Once I overheard that Willa Sue’s real mother might pull herself together one day and reappear, but this had never happened, and Willa Sue called Aunt Carmen Mama from day one. She was a cherub-mouthed girl and always had ahold of Aunt Carmen’s skirt with one hand. The thumb of her other hand hovered, nearing her mouth, just as Aunt Carmen, quick as a mousing cat, pounced on the thumb and pushed it back down.

“Keep your hands at home, Willa Sue, dear,” said Aunt Carmen.

“Girls don’t like trains,” whined Willa Sue. The thumb darted into the red bow mouth and stayed there a full thirty seconds while Aunt Carmen gave my dad a piece of her mind about his paycheck going down the drain on electric trains and throwing good money after bad on more and more electric trains.

“That’s the Transcontinental Railroad you’re talking about, Carmen,” said my dad with a chuckle in his voice and a hand steady and warm on the back of my shirt collar. Then Dad lit a Muriel panatela so that Carmen and Willa Sue would go upstairs again.

I, myself, could not decide if the summer or the winter evenings were my favorites. I was grateful to have both.

From April through September, we got the Cubs and Cardinals games on the radio. We caught the play-by-play down in the basement, while the trains ran their routes in the cool shadows.

If you looked up through the two high-up-the-wall windows, you could watch the long summer evenings fade slowly. When we needed air, we opened the windows and the hot wind of the central plains rushed in.

“You can smell the alfalfa all the way from Kansas on that wind,” Dad claimed, while he and I worked on switches, track repair, and new equipment installation.

In 1928, Dad sold a passel of tractors. And seldom did a week go by without a red box, or even two, arriving from the Lionel Company in Rochester, New York. Inside the train-set boxes was always a paper engineer’s cap with blue and white stripes and a set of printed Lionel tickets for the route of the train inside. I never wore the hats because I thought they were for babies, but the tickets were printed in color and looked like the real thing. I collected them and kept at least a dozen wadded in an elastic band in my wallet.

On winter evenings, the sun set before I came home from school and before Dad came home from John Deere. We had our supper and talked about the work lying ahead that evening. Then we turned out all the lights in the house and went downstairs. On moonless nights, you might not have known from standing on Lucifer Street that our house was there at all. The wind soughed through the lonely spruces, much as I reckoned an Alaska wind might blow. Deep in our basement Dad and I stood together, wrapped on all sides by trains racing this way and that way, their smoke pellets pouring smoke, headlights shining down their tracks.

“Listen to that whistle,” Dad told me many a time. “I hear that same whistle out in the farmland. The farmers hear it when they’re taking in their hay. It goes right straight across the prairie all the way to Lincoln and beyond. Good people and bad hear it from inside the churches and prisons alike just as if it were the voice of the wolf.”

“What is the voice of the wolf?” I asked.

Dad did not say.

Our Lionel trains corresponded exactly to the real trains in the big world. They were all modeled exactly on the genuine locomotive, freight cars, and Pullmans. Each was set up to stop at their stations, then to pull out and make their way up the Rocky Mountain ridges, over the Colorado River, and back through the tunnels to the South Side of Chicago. In the windless basement night, our transcontinental Golden State Limited crossed the plains from Los Angeles to Chicago and back. The station lights winked as each train came through and the striped gate slammed down at the crossings.

By 1929 we owned ten complete trains. My favorite of all was the Blue Comet. Dad also judged it to be the finest of all the great Lionel trains. Her engine was sapphire blue, with a blue tender behind. Her passenger cars bore brass plates with the names of famous astronomers Westphal, Faye, and Barnard. The roofs came off if you wanted. Inside there were hinged doors, interior illumination, swiveling seats, and lavatories with cathedral ceilings.

Dad and I added an observation car to the back of the train. Dad took tweezers and turned two little blue seats right under the arc of the Plexiglas dome so that they were in perfect viewing position. “Someday, Oscar,” my dad said, “we’ll go to New York City and board the big Blue Comet, and these are the seats we’ll reserve. The whole Atlantic shore will be spread before us, start to finish. We’ll get out at Atlantic City. Then we can have our portraits painted on the boardwalk, and we can eat Turkish Taffy by the sea. Maybe for your next birthday!”

My next birthday came and went, and Dad and I never did leave Cairo, but our imaginations took us up and down the continent and that was plenty enough for me. Sometimes I would place my head sideways, ear down, on the grass of the layout. “Are you sleepy, Oscar?” my dad always asked.

“No, just looking,” I always answered. “Just looking.”

What I was really doing was closing my bottom eye and staring with my top eye into the carriages of the passenger cars. The cars came complete with little cutout people, sitting in silhouette in each window. Here were two tiny tin women in hats, hands uplifted, chitchatting, both bent face to face. There a tin man read the newspaper. A tin boy ignored the porter, who stood above him with a tray, and gazed, two tiny pinholes for eyes, back out toward me. In this way, everything on the layout came to life, and I was no bigger than the people and the trains and buildings that stood in miniature before me. I truly believed that if I wanted to, I could have just walked right into the permagrass and onto a train. I could have dashed right up the steps of the Blue Comet and sped off into the wheaty night prairies with the Rocky Mountains looming just beyond.

Knowing I might be able to do this made me the happiest boy in the city of Cairo, even the state of Illinois. Me, Oscar Ogilvie Jr., in the dark safety of circling trains. Me, with my dad standing large beside me, working the central switches and the throttle, big as a car battery, that caused the trains to roar past, the signal lights to blink red and green, and made all things possible in the world.

The voice of the wolf howled a thousand miles to the east in the fall of 1929. Something had happened in the city of New York. People called it the Crash. I did not know what had fallen or crashed, since I was only nine years old at the time.

Dad read the Cairo Herald aloud to me. “Millionaires are jumping out of skyscraper windows in despair,” he reported. “Some of Wall Street’s biggest tycoons have sold off their diamond shirt studs. Now they’re peddling apples on the street corners.”

“Why?” I asked.

“They lost all their money,” said Dad.

The radio would not shut up about the crash. When it was explained to me, the words fell about my ears like raindrops but did not bother to go in.

“Gambling like card sharks on the stock market!” Aunt Carmen was heard to say. “It’s the work of the devil. Credit. Margin calls. Credit’s what ruins lives! They’re like fortune-tellers at the horse races, every last Wall Street tycoon!”

I did not ask what a card shark was, or margin calls for that matter. I had enough trouble on my hands. My problem was math. For me 1929 was the year of blinding math problems. When the teacher wrote the problems on the blackboard, my mind drifted everywhere, to the bugs on the window and the ticking of the wall clock. Our teacher never smacked us, but she did smack our desks plenty with her ruler. Each wrong answer got a wham! on the offending student’s desk. I got a lot of whacks and whams that year and an F in arithmetic.

Dad tried to teach me a quick way to solve the problems. He had a secret shortcut for fractions, but I could not bring Dad’s methods to class because the teacher did not approve of shortcuts.

In the year that followed the crash, my dad’s tractor orders began to fall short of what they had been. There was talk about layoffs at John Deere. Dad was worried about being laid off his job if he didn’t sell ten tractors a month.

Nineteen-thirty passed and things got worse. In the summer of 1931, Dad explained that all the money in the country had been sucked down the drain like soapsuds. President Hoover was no better than the Roman emperor Nero, violining away while Rome burned to a crisp. Money was no longer to be found in the pockets of the working people and farmers. Their savings were worthless.

Farm prices fell, and farmers stopped ordering tractors.

By August our menu changed. We dropped from beef to canned yams. From lamb chops we sank to Ham Stix. There were no more Muriel panetelas and no boxes from Rochester, New York. The catalog from Lionel still came in the mail, but now it tortured us with its pictures of the newest, sleekest trains.

One late-summer night, Dad found me deep in the pages of the catalog. I was looking at the “Brand-New Models for Christmas Giving!” page. There was a picture of a boy and his dad, pipe in mouth, glowing over their new trains on Christmas morning. Put a cigar where the pipe was, and it looked just like Dad and me.

Dad read the catalog advertisement over my shoulder. “She’s a beauty, isn’t she!” he whispered with a sigh. “The President.” It was a new silver model, streamlined like a rocket ship with every car named after a different president. It cost three times more than any other train.

“Boy, it would be perfect on our layout, Dad! And look. They put a girl in the window of the observation car.”

That was unusual. Lionel almost always featured boys, in, out, and on top of the model trains with their pipe-smoking dads. Never a girl.

“It’s an expensive train. Maybe next year,” said Dad.

“It’s okay, Dad,” I tried to assure him. “We’ve got plenty of trains!”

But even in our basement world, apart from the world above, Dad cracked his knuckles and frowned. He could not concentrate on the trains.

“Oscar,” he said one evening, “they are going to take the house.”

“House?” I asked. “What house?”

“Our house,” said Dad, looking at the wall behind my head.

“But it’s our house,” I argued. “It’s a free country. No one can take our house away.”

“The house is mortgaged, Oscar,” he answered. His eyes were open wide like the eyes of a sick man.

“What does that mean?”

“It means it’s owned by the First National Bank of Cairo. The president of the bank, Simon Pettishanks, came here in his big Bentley when you were at school. The bank will repossess the house by the end of the week.”

“But . . .” My mind raced in ridiculous circles.

“Aunt Carmen hasn’t got an extra dime for a cup of coffee,” he said. “There’s nothing for it, Oscar. We’re done.”

“But where will we live?”

“They say there’s work in California.”

“Will we take our layout there? All our trains?”

“Oscar,” he began, but he couldn’t finish.

“Yes, Dad?”

His face answered me before he opened his mouth to speak. “The trains will be sold along with the house.”

“What do you mean, sold?”

Dad winced as if I’d slapped him. “Oscar,” he said, “if I don’t have the extra cash from selling our trains, I’ll become a bum. It means I sneak onto a freight train at night when it’s on a siding and try not to get arrested by the railroad police. If I don’t get arrested, I sleep in the cattle car with the hobos and tramps and get my wallet and shoes stolen. Sell the trains and I can buy a respectable ticket on the Rock Island Line and shave my face with Barbasol.”

I didn’t like his “I.” I wanted to hear “we.”

Dad continued, his voice gravelly: “I guess the bank president’s son likes trains, Oscar. Pettishanks paid half price for ’em. It’ll buy me a ticket to California, Oscar, and a month’s money to live on while I try to find a job.”

I did not wait to hear that I would be parked with Aunt Carmen and Willa Sue. My dad held out his arm to haul me in against his side, but I yelled like a boy on fire. I ran upstairs and out into the night, slamming the screen door. Pell-mell I hurtled into the dark, as if the cool spruces of Lucifer Street could stop the burning. I had no doubt the wolf was watching me, red-eyed, from a broken window of the Lucifer Fireworks ruins.

Like a storm looming behind the farthest trees, Dad’s leaving waited in the wind before breaking over me. He wanted to work for John Deere, San Fernando Valley, but nobody knew what kind of work was to be had in California. Farming was different out there. Instead of alfalfa and wheat, they grew walnuts and oranges. “Out there” still overflowed with everything Californian, like Chinese food, palm trees, and Hollywood movie stars.

“Deere’s got two branch offices out there,” Dad said cheerfully. “I’ve just put in for a transfer.” You had to look on the sunny side, he assured me. But his voice had no sunniness in it.

It was always my impression that kids live in a fenced pasture, heavily guarded by grown-ups. We were not allowed out of the fence. We were told what was going to happen but seldom why. If we were told why, it almost never made sense. Not the kind of sense that makes sense when you are eleven.

September 1, 1931, Mr. Pettishanks and his deputy took the keys to our house and ownership of the trains.

I listened through a basement window to Mr. Pettishanks speaking to an assistant.

“Pack the trains and the equipment in cotton wool, Frank,” said Mr. Pettishanks to his deputy. “Get rid of this homemade layout. Get a couple of men to take it out and burn it. We need a clean basement to resell the house.”

I wanted to pummel Mr. Pettishanks with my fists. I wanted to poke him in the nose and pour sugar in the gas tank of his Bentley saloon. But I did none of these things. My dad found me on my sheetless bed an hour later.

“Time to go, Oscar,” he said. “Wash your face. You don’t want Willa Sue asking you embarrassing questions about why your eyes are red.”

Dad and I boarded the bus to Aunt Carmen’s house with our two suitcases of clothes and a case of Ham Stix.

“I’m going to hide the Ham Stix behind that water tank in Carmen’s basement,” said my dad. “It’ll be there for you, Oscar, when you can’t swallow another bite of sardine casserole.”

Dad wore his tie because he wanted to look sharp. The first leg of his trip was the 5:10 to Topeka.

“Don’t drag it out, Oscar,” said Aunt Carmen to my dad as he bent to say good-bye to me.

Dad squatted down. “I’ll write,” he whispered in my ear. “I’ll write lots of letters, and when I get a good job out there”— his eyes were all blurry —“you’ll come to me on the Golden State Limited. I’ll send you tickets, and I’ll meet you at the station in Los Angeles. I promise, Oscar.”

“I have something for you, Dad,” I whispered back.

“What?”

I had been holding it in my hand the whole time. Mr. Pettishanks had left it on the umbrella stand. Before he remembered where he left it, I had sneaked up and snatched it away, wrapping it in careful layers of toilet paper.

Dad unwrapped it. “Holy smokes, Oscar. It’s a Macanudo. A rich man’s panatela!” He held it to his heart. “I’ll keep it safe, and when I see you again, I’ll light it up!”

I waved him down the street, leaning as far out of the porch as I could, him walking backward, throwing kisses, and yelling, “The Golden State to Los Angeles, Oscar! Not long!” I held my fingers to my nose to smell the last of the Macanudo. I would never wash it away.

“Get busy with the kitchen chores, now, Oscar!” said Aunt Carmen when she found me still staring out from the front porch railing into the empty street.

“I never did see a grown-up man cry before,” remarked Willa Sue.

“Well, now you have,” I snapped at her. But evidently the sting in my voice clearly said, “Shut up, birdbrain!”

“In this household, Oscar, we keep our fingers busy and our tongues polite,” said Aunt Carmen. “Please wash your hands and get the smell of that disgusting cigar off them!”

She had gotten out a pound of blisteringly white margarine and had it waiting for me unwrapped in a bowl the moment Dad turned the corner of Fremont Street. The margarine, a snowy brick of soft fat, came wrapped in a waxy paper bag cheerfully labeled Butterine. In the middle of the fat was a tiny red button. I had to work that little scarlet dye pellet into the rest of the white lard, gradually diluting the intense red color until it spread out and turned the whole lump a revolting yellow.

“Dad buys butter,” I said.

“That’s exactly why he has gone and lost your house to the bank, young man,” answered Aunt Carmen. “Butter, trains, and cigars. It put him in the poorhouse! You’ll find us much thriftier here!”

Nothing was the same after that.

When I came home from school, the supper casserole was all cooked. It sat on the stove in its green ovenproof baking dish. I was not allowed near the stove. “Boys cooking! That’ll be the day!” said Aunt Carmen.

I went to bed when my homework was done, my feet scrubbed, and my prayers said in front of Aunt Carmen. As her footsteps receded down the hall, I got the stash of Lionel tickets out of my wallet that I had kept back from the sale of the train sets to Mr. Pettishanks.

I switched the Lionel Line Golden State ticket to the top. Of course it wouldn’t so much as get me onto a streetcar, but I loved seeing the words printed in gold letters:

With the toy ticket in my hand, I could sleep.

Aunt Carmen made her living teaching piano and declamation at the wealthier people’s houses after school hours. She had a regular route with once-a-week visits to each family.

I begged Aunt Carmen to leave me home. “I need to do my homework,” I explained. She examined my latest report card. “You flunked arithmetic, Oscar,” she said.

“I have trouble with long division and fractions.”

“Well, that grade’s simply going to have to improve,” she said.

“If you let me stay home, I promise I will do my homework. All my homework. I will do better. Please, Aunt Carmen?” I asked.

Aunt Carmen didn’t like being pleaded with. On the other hand, she didn’t like me flunking out of arithmetic.

Willa Sue jumped up and down for attention. “We get key lime pie on Wednesdays at the Merriweathers’ house,” she said in a singsong voice, “and we almost always get a nice piece of chocolate cake from the Baxters’ cook on Fridays.” She twirled a coil of her hair in her fingers. “If Oscar comes along to lessons, Mama, maybe they won’t give out so much pie and cake. Maybe we’ll just get smaller slices, or maybe they’ll even switch to Saltines crackers.”

Aunt Carmen did not appear to share Willa Sue’s worries about Saltines crackers. She frowned at my report card one more time and declared, “You are a boy of eleven, Oscar,” in just the voice she’d have used if she were reading out the list of sick parishioners in church. “You will be responsible for at least a C-plus on your next report. You will watch the house. If I catch you reading a novel from the library or making any other kind of trouble, it’s not going to be a pretty picture for you.”

“Thank you, Aunt Carmen,” I answered.

“The world is full of tramps and hobos,” said Aunt Carmen. “They are desperate men who get off and on the trains. They wander around town in filthy clothing. They sleep in the alleyways and look for handouts wherever they can find them.”

“Yes, ma’m,” I said steadily.

“No one is allowed in the house. Do not talk to strangers. You may not use matches, waste electricity, or nibble on what is not yours to eat. Is that clear?”

“Yes, ma’am, and I can have the supper casserole nice and hot when you get home if you let me light the oven!”

Aunt Carmen looked at me curiously out of her true blue eyes. I guessed that few people offered to do anything for Aunt Carmen because she herself finished doing everything before anyone else could think of it.

All she said to my offer was, “We’ll see.” Aunt Carmen put on her hat and her white cotton gloves, and down the street she marched to the bus stop, Willa Sue in one hand and her bag of sheet music and Famous Speeches of Famous Men in the other.

Over her shoulder, Willa Sue burbled, “I’m bob-bob-bobbing like a red-red robin because it’s Monday! Monday is Betsy and Cyril Pettishanks day! They have cocoa with whipped cream! Sometimes marshmallows!”

“Pettishanks,” I growled under my breath. The Pettishankses were among Aunt Carmen’s piano and declamation clients. The Pettishanks boy was the one with my trains. Over the years, I had learned a few bad words on the playground at school. Now I strung them all together and said them out loud as soon as the bus had come and whisked Aunt Carmen and Willa Sue to River Heights, where the really big houses were.

I opened my book, Arithmetic for the Modern Child, and stared at the assignment. Fractions made me sleepy. I needed something to eat to keep me awake.

I padded carefully around Aunt Carmen’s kitchen and looked in the larder. She didn’t buy vanilla wafers or even cans of Vienna sausage the way I used to do at Rubin’s Market. She had a larder full of black-eyed peas and canned codfish cakes. The only answer was pancakes. Aunt Carmen might not notice that one egg, a cup of milk, a dab of margarine, and some flour was missing.

I ate my pancakes with molasses because Aunt Carmen did not spend money on syrup. For cooking, Aunt Carmen used Spry, pure fat in a can, but I could not even look at the Spry without gagging and used a sparing amount of Butterine instead.

My fifth-grade teacher, Mrs. Olderby, just loved problems. Before tackling thirteen seventy-fourths divided by two-thirds, then multiplied by seven-eighths, I washed up the pan and my plate so sparkling clean that no one would ever know what I had been up to. The smell of fresh pancakes would be lost in the smell of warming turnip and condensed milk casserole.

After the first week of pancakes and fractions, I struggled to a D instead of an F on one of Mrs. Olderby’s surprise quizzes. Watching Willa Sue and Aunt Carmen disappear on the number 17 bus and knowing my pancakes were ahead of me was as delicious as the hot pancakes themselves. I could not wait for this small adventure every afternoon. But then Mrs. Olderby suddenly jacked things up to decimals. Decimals in long division was a leap into the blackness of space. Arithmetic for the Modern Child contained the riddles of the Sphinx as far as I was concerned.

I looked at my homework:

Butcher Smith is selling pork at one dollar and fifty-one cents a pound and liver at two dollars and twenty-nine cents a pound. Butcher Jones is selling pork at two dollars and nine cents a pound and liver at ninety-nine cents a pound. Mrs. Brown wants two and a half pounds of pork and six pounds of liver. Which butcher should she buy from?

I was as lost as a child in the forest. Each problem was like trying to find the Northwest Passage, a route that did not exist. Dreaming out the window, I pictured butcher Smith and butcher Jones in their bloody aprons weighing meat. Who would want to eat that disgusting liver, anyway? Maybe Mrs. Brown liked one of the butchers better. Maybe butcher Smith winked at her across the hamburger meat. Who cared where she shopped, anyway? Not me!

I doubled my pancake recipe and worked on my homework from the glider on the front porch, using the daylight so as not to waste electric lights.

It was in the porch glider, on a brilliant October afternoon, that I sprawled with ten homework problems spread out on the seat around me.

If a rotor turns at the speed of 569,001.4562 an hour, how many turns will it make if its speed is reduced by .06%?

The nine problems that followed were much worse. My mind wandered to my trains. Where were they now? I closed my eyes and thought of my Blue Comet. Would I ever see it again? I knew I had as much chance of laying hands on my trains as flying to Mars.

“I can help you with that problem!” said a voice.

I looked up. A man stood at the edge of the porch, looking in on my spread-out papers. He was wearing horn-rimmed glasses and a snap-brim cap. He did not appear to be in filthy clothes or in danger of arrest. He had a pleasant smile, and he smelled of Barbasol shaving cream, like my dad. The grandfather clock had dinged four o’clock. There was still an hour and a half of afternoon before Aunt Carmen and Willa Sue alighted from the bus.

“My name’s Henry Applegate,” the man said, taking off his cap politely. “I was a math teacher once.” He replaced the cap and removed his glasses. “Raised three boys of my own! All grown,” he added as he polished the lenses on a tattered but clean handkerchief. He was well spoken. That was a good sign. He was carrying a fat book. Another good sign. I didn’t think tramps and hobos went around with heavy books under their arms.

He continued to introduce himself. “I taught algebra and geometry in the town high school of Searchlight, Texas. A year ago, Mr. Hoover’s recession hit Texas badly. Everybody upped and went away. They closed the school. I lost my job, so I came up here to see if there was any work.”

“Where do you live?” I asked.

“Got a room at the Y for twenty-five cents a day,” was his answer.

“My dad lost his job, too,” I said. “He went to California. He’s going to work for John Deere out there. Soon as he gets his job, he’s going to send me a ticket to go. He’s going to meet me at the station in Los Angeles.”

Mr. Applegate pointed to my paper with his pinky finger. He said, “The answer to the first question is five hundred sixty-eight thousand, six hundred sixty point oh five five, three times an hour. The answer to the second question is twenty million, four hundred ninety-six thousand, forty-one point oh nine, and the answer to the third question is six hundred million, nine hundred fifty thousand, four hundred seventy-eight point ten.”

“Come again?” I said, pencil stub furiously writing.

Without effort he reeled off the answers a second time. “Once upon a time, I was even a mathematics tutor at the University of Texas,” Mr. Applegate added by way of further explanation. I noticed him breathing in deeply and grinning. “Is that pancakes I smell?” he asked.

“Are you hungry?” I asked.

“I haven’t eaten but a box of raisins in two days,” said Mr. Applegate.

I retreated from the porch to the kitchen and made him a plate of pancakes all his own and covered them with molasses. I added to his lunch an apple, which was all I dared do for fear Aunt Carmen would notice something missing. I passed the plate out the window to him. When I turned away for a second, everything on Mr. Applegate’s plate was gone, and he thanked me. In another five minutes, my homework was completely done.

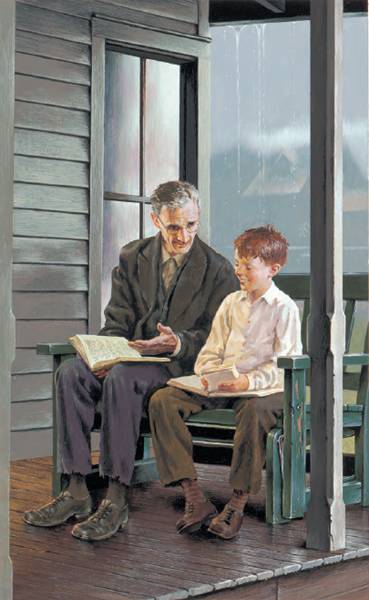

“I am going to explain how to do it,” said Mr. Applegate. “It’s no good you just having the right answers. You have to know how to get them. Then we’ll read a poem together.”

A little comprehension flickered in my mind as Mr. Applegate showed me how to do the work. He was certainly a better teacher than Mrs. Olderby. It had never occurred to me that one teacher might be better than another. Teachers just were. You got them, one after another, the way you got shoes.

After math, Mr. Applegate opened The Fireside Book of Poetry. We read, “The boy stood on the burning deck . . .” Tears sprang into my eyes when the father and then the noble son die on a fiery ship in the midst of battle. Mr. Applegate passed me his handkerchief.

Mr. Applegate stayed outside the kitchen window for the first week. He did all the problems from afar. But when it rained, I could not bear to see him all wet and dripping. I asked him to come under the eaves and sit in the glider on the porch. I showed him my postcards from Dad. He showed me how he did math in his head.

“You can train yourself, Oscar,” he assured me. “Just use the palm of your hand instead of paper. That way you feel the numbers as you write them with your fingernail, but you can’t see them. Makes you concentrate. You do that for a few weeks, and you’ll start doing math in your head just like me!”

Each afternoon we lightened Arithmetic for the Modern Child with The Fireside Book of Poetry. One afternoon Mr. Applegate recited a poem called “O Captain! My Captain!”

“It has another dead father in it!” I complained, my lip trembling. “This time he’s lying cold and dead on the deck!”

“Next time we will do a more uplifting poem,” said Mr. Applegate.

“I don’t want an uplifting poem!” I pleaded, serving him his plate of pancakes. “I want to turn myself into an arrow and fly to when I see my dad again.”

Mr. Applegate’s jaw dropped. “Now that is very interesting, Oscar,” he said, actually suspending his forkful of pancakes, midair over his plate, on the way to his mouth.

“What is interesting?” I asked.

“Well most people would say I want to fly to where, not I want to fly to when. Flying to when is a very complicated mathematical concept. Perhaps only a handful of people on earth really understand it. It is the theory that time and place are one thing, not different things, discovered by Professor Einstein. He believes that time is like a river. All times are present at once along its banks. Everything future and everything past is happening right now at some point in that river. If we were strong enough and fast enough to get across the current, we could reverse course and go back around the last bend in the stream. We might see the Battle of Gettysburg and find Mr. Lincoln in the White House.”

“We could?” I asked. “Then we could warn President Lincoln not to go out to the theater ever again!”

“Yes, we could, but if we did, every event ever after that would change, too. Who knows, Oscar? A new chain of history would fall into place like cogs turning on a billion sprockets. Herbert Hoover might not be our president today if Lincoln had not been assassinated. On the other hand, you and I might never have been born. It would be a foolish thing to go back in time and make changes. Not to mention, Oscar, that it would take a very fast rocket ship to go into the past. It would have to go so fast that it would disintegrate, and all its passengers would disintegrate with it.”

“But how about forward? Could somebody like me go forward from now, just a little bit?” I asked. “Maybe just enough to find my dad?”

“Oh, forward is part of the concept, too, according to Professor Einstein,” answered Mr. Applegate.

I answered Mr. Applegate with a puzzled look.

He explained more, if explain is the right word — I couldn’t make sense of a single particle of his thinking. “Oscar, if you wanted to go into the future, you would have to travel more slowly than time itself. You would have to use the principle of negative velocity. Time would simply pass you by.”

“Did Professor Einstein invent a way of doing it?” I asked.

“Alas, Oscar,” answered Mr. Applegate, eating his pancakes now, “Professor Einstein is just a mathematician, not an inventor.”

“There’s always a catch,” I said, and looked down at my first problem of the day.

A train leaves Station A at two p.m. It arrives in Station B three hours, four minutes, and thirty seconds later. Station B is 75.6 miles away from Station A. How fast is the train going?

“Who cares?” I moaned. “Who cares about the stupid train, the butchers, or liver prices?”

Every day Mr. Applegate ate with the speed of a hungry German shepherd. Every day he told me of his job-hunting progress. One week he raked leaves for the city park for twenty-five cents an hour. Another day he changed oil, lying on the floor under the cars in the Mobilgas garage. There was no regular work to be had.

The no-work stories frightened me. I was afraid the same thing was happening to my dad way out in California. Were Dad’s cheerful postcards from this town and that just a mask over hopelessness? Were my dad’s handkerchiefs tattered? Were there worry pouches sunk below his eyes, like Mr. Applegate’s?

“Poetry gets you through the hardest times, Oscar. It’s like a tonic,” Mr. Applegate told me. “The world has forgotten poetry and how it heals the soul and body, too.”

Mr. Applegate finished his pancakes, sat back in his chair, and out of his mouth came a stream of verses. It was a righteous theme, a moral Sunday-school kind of poem, but it had a kick to it and it made little goose bumps go down my back and lift the tiny hairs along my spine.

“I liked that one, Mr. Applegate!” I told him.

“It’s a very famous one called ‘If,’ Oscar, and it was written by Rudyard Kipling. Come June, some unlucky kid in every school in America has to recite that chestnut on graduation day. Preachers love it; teachers love it! Weepy old army officers love it! But, darn it, when the blues come over me, I set myself right by reciting ‘If.’”

“How can you remember so many lines of it?” I asked.

“There’s a trick to learning things by heart. A secret code.”

“Wow!” I said. “Could you teach me how to do it?”

“Nothing easier,” said Mr. Applegate. He flipped open The Fireside Book of Poetry to K for Kipling. I scanned the poem “If.” With a pencil, Mr. Applegate made tiny red underlines on certain words in the first verse.

If you can keep your head while all about you

Are losing theirs and blaming it on you,

If you can trust yourself when all men doubt you,

But make allowance for their doubting too;

If you can wait and not be tired by waiting,

Or, being lied about, don’t deal in lies,

Or, being hated, don’t give way to hating,

And yet don’t look too good, nor talk too wise . . .

“Now try to remember those key words in order,” said Mr. Applegate.

“I can’t possibly,” I answered.

“The code works just the way ‘Every Good Boy Does Fine’ lets you remember the notes E, G, B, D, F in music,” Mr. Applegate explained. “Keep blaming yourself. Your allowance can wait. Lies and hating don’t look too good! Repeat it a couple of times, Oscar. Now can you recall your anchor words?”

The first verse of “If” flowed into my mind as easily as “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star.” Each afternoon Mr. Applegate and I got more of the poem down to memory.

One day we had run out of milk and eggs. I did not dare open a can of substitute turkey hash or even tinned cod cheeks in case Aunt Carmen found it missing. Then the idea came to me.

“You know what!” I said to Mr. Applegate. “There’s a whole carton of Ham Stix hidden in the basement. My dad brought ’em from our house. I reckon those Ham Stix are legally mine.” I made Mr. Applegate a nice hot Ham Stix sandwich on toast. He loved it. He said it gave him energy.

“Let me see your last test paper from Mrs. Olderby,” he said. “Let’s go over those answers.”

We worked from three-thirty to five o’clock each day as the days grew short and cold. Aunt Carmen never questioned the missing pieces of bread. She never discovered about Dad’s carton of Ham Stix behind the water tank.

Aunt Carmen did not exactly smile, nor did she offer any praise, but, lips pursed, she did say, “Oscar, your grades in arithmetic are more respectable than they were.”

I beamed, but then Aunt Carmen soured it by tacking on, “It seems as if you have a better sense of numbers than your father. Your father is terrible with numbers and money. That’s why he invested in those foolish trains and put himself in the poorhouse.”

“I hope to get a B soon, ma’am,” I allowed casually.

“Hard work will achieve it, Oscar,” she said. “I hope your father is able to find some hard work for himself.”

There had been nine postcards from my dad. Each one featured a picture of a new city in a new state. He had gone from Topeka to Little Rock, and from there to New Mexico, Arizona, then Fresno, California. There were no jobs, and I guessed his cash was beginning to run out. I had no address to write him at. I felt frozen in my half of our correspondence because I could not answer his cards.

My eyes prickled and nearly burst into embarrassing tears when I thought of him at dinner or in school. So instead I tried to imagine Los Angeles, City of Angels. In my mind’s eye it was a city of temples and oranges, grander than any of the seven wonders of the ancient world. In the middle was the train station. In its fabulous halls my dad ran down a gold speckled marble platform to meet my train and melt the ice that cramped my heart.

On November 18, it sleeted all afternoon. I was afraid Mr. Applegate would not come in the bad weather, but he showed up all the same. It was too cold to sit outside on the glider. Nervously I looked at the clock. Still two hours before Aunt Carmen and Willa Sue would trundle up the street from the number 17 bus that pulled in at 5:51.

“We can sit inside for a while,” I said. “I don’t reckon they’ll ever be the wiser.”

I made Mr. Applegate a cup of cocoa to go with his Ham Stix sandwich. He was grateful. “I don’t know what I’d do without you, Oscar,” he said, wiping his mouth on his sleeve. “The food gives me strength. I’ve got a job tonight. Pays a dollar an hour. Shoveling slush and ice at some rich fellow’s party up in River Heights. His driveway’ll be full of fancy cars, and those folks don’t like to slip and slide. One of the gardeners said the boss might even have a regular indoor job for me downtown. We’ll see.”

“What kind of job?” I asked.

But Mr. Applegate didn’t know. His nose was running, and he blew it stuffily into his handkerchief. “My shoes have holes,” he explained nasally. “I caught a chill.”

I wished I had even a dry pair of socks for Mr. Applegate. I had nothing to give him. Aunt Carmen had darned my socks five times, heel and toe, but they were too small for a grown man.

“I don’t understand,” I told him. “One day everything in the world was fine. Dad and I had lamb chops and ice cream. The farmers farmed and bought tractors and the teachers like you had jobs teaching, then suddenly, bingo! It was over. My dad is gone, and now we’re lucky to have cold turnips for supper. How could it happen?”

“Greed,” said Mr. Applegate. “Greedy Wall Street profiteers pushing their luck like high rollers betting right over the top. They stacked the stock market like a house of playing cards. They bet way over their heads, couldn’t back up their spending, and it all came tumbling down.”

I knew well enough from Our Lady of Sorrows Sunday School about greed. I wasn’t sure if the money changers greased people’s palms in the Temple, or the Tower of Babel, but it didn’t matter. Sure as shooting, there were greaseballs and gamblers in the Bible, and their descendants had clearly been at work on Wall Street in October 1929.

Mr. Applegate and I solved the day’s arithmetic problems, going through the hoops of show-your-work on each one. “You’re not dreamin’ about your train set, now, Oscar,” Mr. Applegate prodded me gently whenever my eyes glazed over.

I looked up at the kitchen clock for a moment. It was exactly 4:15. I glanced out the window. “Holy mackerel!” I said. “There they are! Getting off the bus. They’re early! You’ll have to go out the back door!”

Mr. Applegate grabbed his tattered overcoat and vanished out of our kitchen like a rabbit in the night.

They noticed nothing amiss. Luckily the pot and cocoa cup were clean; the Wonder bread was tucked neatly in its wrapper in the bread box. The frying pan was hanging from its hook, brightly polished, all traces of Ham Stix gone, and the empty Ham Stix tin lay sunken beneath Aunt Carmen’s coffee grounds in the very bottom of the trash barrel. The kitchen smelled of my lima bean casserole.

I looked up from my arithmetic. “You’re early!” I said as calmly as I possibly could.

Aunt Carmen removed her hat. “The Merriweathers have chicken pox,” she announced as if chicken pox were a personal shortcoming. “They had a big yellow quarantine sign up, right next to the front door. Not a living soul is allowed in or out on account of the chicken pox. So that took care of Mary-Louise’s ‘Yankee Doodle’ practice and the Patrick Henry speech that her brother was rehearsing. We went all the way out to East Cairo for nothing, and of course, I can’t bill them for today.”

“And no key lime pie, either,” grumped Willa Sue. “I was all looking forward, and then here come the dumb yellow quarantine signs and no pie!”

There had been many a time that my dad had encouraged Aunt Carmen to get a telephone. “I’ll call you up, Carmen, and pass the time of day with you!” Dad always said. “Then you can talk to me and not have to put up with the cigars!”

Aunt Carmen always pointed out that telephones, like electric trains, were expensive gadgets. They were a luxury for those who could afford them, not ordinary folks like us.

This did not stop me from saying to Aunt Carmen, “If we had a telephone in the house, Mrs. Merriweather could have called —”

“What’s this?” interrupted Willa Sue. She hefted The Fireside Book of Poetry over the table to Aunt Carmen. “This book’s soaking wet!” Her voice began the singsong teasing of the playground. “Oscar’s left the ho-use! Oscar’s been to the library in the ra-in and ruined the bo-ok, and he’s in big tro-uble!”

Aunt Carmen opened the clammy covers of The Fireside Book of Poetry. The book fell open where it had been bookmarked to Kipling’s “If.”

“Whose book might this be, Oscar?” asked Aunt Carmen.

“I don’t know!” came tumbling out of my mouth. Willa Sue snorted from across the room.

Aunt Carmen flipped to the inside back cover, where the library glued its card envelope and stamped the return dates for each book as it was checked out. She tapped the column of stamped dates with her fingernail.

“Let’s see,” she said. “It seems this book was checked out today, November eighteenth, Oscar!”

My mind was flying in circles of explanations, but none were needed.

Aunt Carmen squinted again at the stack of date stamps. “Interesting!” she said. “This book, The Fireside Book of Poetry, has been checked out of the Cairo Public Library every week since early fall this year. Hmm! Not one checkout before that for ten years. Early fall is when I began leaving you alone in this house. This must be your favorite book, Oscar. ‘If’ must be your favorite poem!”

I shook my head no and nodded my head yes both at the same time. I could not control turning as red as a beetroot.

“Oscar,” said Aunt Carmen, shutting the cover of the book, “did you leave this house without permission and go across town to the library today?”

“No, ma’am,” I mumbled.

“In that case, explain this soaking wet book, checked out of the library today, please, Oscar!” she said, looking up at me with her true blue eyes.

For all it mattered to Aunt Carmen, I could have appendicitis and a broken leg, but she would never leave me home alone again. She did not trust me not to let riffraff into the house, endangering myself, her bisque figurine collection, and everything else she owned in the world. “Steal, steal, steal! Is what those tramps do,” she told me during my dressing-down. “And you let him in, Oscar! A common scallywag as if he were a man of the cloth!”

There was no telling Aunt Carmen that Mr. Applegate was anything but a common scallywag.

As a punishment for letting a stranger into the house, I had to write Rudyard Kipling’s “If” ten times in my notebook every night until Christmas. I was not alone. In the world of declamation, Rudyard Kipling’s “If” was a hot number. It was Aunt Carmen’s clients’ hands-down first choice. Everyone wanted their son to recite it. Nearly all her unlucky students had to memorize all thirty-two lines of it, standing straight as ramrods while they spoke.

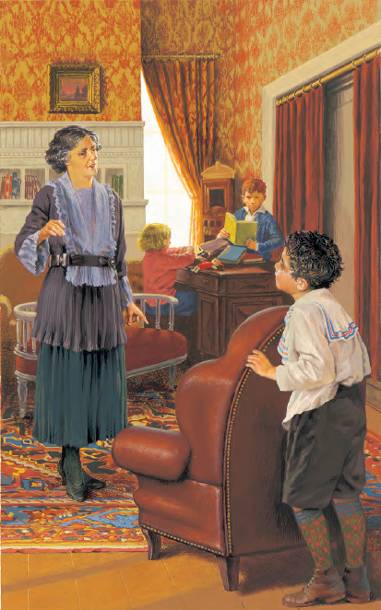

From that day forward, I had to come along to the piano and declamation lessons and do my homework in whatever house we happened to find ourselves spending the afternoon.

The bus took us to the wealthier parts of Cairo. The lessons brought us into the homes of families who could afford to have Aunt Carmen teach their little girls to play the “Moonlight Sonata” and their sons to give George Washington’s Farewell. These were the children of our patricians, the Cairo Country Club families, every last one of them. They had cooks, gardeners, and driveways with cars in them. They possessed telephones without party lines and the telephones had whole rooms of their own. Their houses were furnished with glowing cherrywood antique cupboards and tables smelling of lemon-oil furniture polish. Their parlors contained thick oriental carpets and deeply upholstered easy chairs. The rich buttery smells from their kitchens were not the same as those that wafted out of Aunt Carmen’s parsimonious oven.

Aunt Carmen kept one suspicious eye on me as I did my homework at strange dining tables and in unfamiliar inglenooks. If I tried to sink into one of the deep-as-your-elbow upholstered sofas, I was told to sit in a hard wooden chair instead.

Willa Sue brought her dolls to these lessons. She dressed and undressed them and took them for walks. She played endless games with the dolls. It embarrassed me to even be in the same room with her. Mothers and cooks thought Willa Sue had cherub lips just like Shirley Temple and found her charming. They gave Willa Sue choice slices of pie and cake. They looked at me and my arithmetic book as if I were a stray cat. Sometimes they’d give me a piece of gum, which Aunt Carmen made me spit out the moment they were not looking.

I endured. The only house I could not bear was the Pettishankses’. Betsy Pettishanks was a terrible little pianist. She burst into tears when Aunt Carmen made her start from the beginning every time she messed up on the second bar of the “Moonlight Sonata.” Betsy was meant to be in a first-grade recital, and her mother wanted her to get the prize. Mrs. Pettishanks, in her fashionable dress with silk-covered buttons and linen collar, would drift into the living room just when Betsy was playing. She pretended to arrange and then rearrange vases of flowers or bowls of fruit. Encouragingly Mrs. Pettishanks hummed the “Moonlight Sonata” as if it might help Betsy through the trouble spots. Every time Betsy missed that second bar, Mrs. Pettishanks would startle a little as if a tooth hurt her. Aunt Carmen said privately that Betsy needed to be switched back to “Yankee Doodle” before advancing to the “Moonlight Sonata.” Privately Aunt Carmen did not think Betsy had a snowball’s chance on a griddle of getting a prize, but she said nothing about any of that to Mrs. Pettishanks.

On seeing me for the first time, Mrs. Pettishanks, wife of the train thief, had donated a pile of her son Cyril’s cast-off clothing to Aunt Carmen for me to wear. “So much more personal than giving them to the church bazaar!” is what Mrs. Pettishanks had said to Aunt Carmen.

I was a shrimp. The push weight on the doctor’s scale barely held at fifty pounds when I stood on it. Aunt Carmen took in Cyril’s waistbands and turned up his sleeves and pant legs. I would grow into them one day. “In the meantime we don’t have to take you down to Sears Roebuck for new clothes, and that’s a plus for the household budget, young man.” It was the greatest shame of my days to have to appear in front of Cyril Pettishanks dressed in his own hand-me-down clothes.

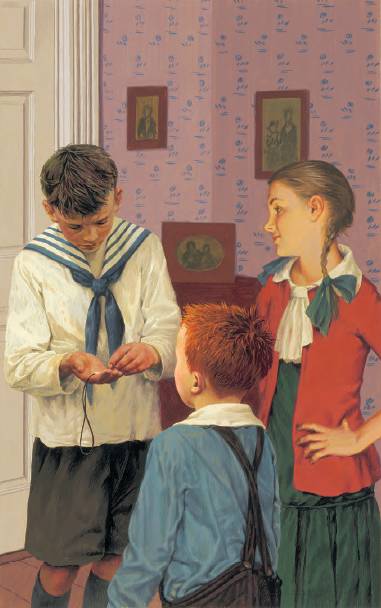

Cyril Pettishanks was in the fifth grade just like me, but I had never laid eyes on him before because he went to River Heights Academy instead of the public school. Cyril’s father wanted Cyril to be on the debating team at Harvard one day. In order to prepare for this, Cyril had to memorize the great speeches of great men. According to Willa Sue, Mr. Pettishanks required a huge dose of Kipling, which, he said, “cleared the mind and soul.”

Cyril was a handsome boy, if always a little damp. He had thick black eyelashes and a ruddy face. He was as bumptious as a Labrador retriever. Cyril wore a blue-and-red-striped tie because that was the River Heights Academy uniform, but the tie was knotted wildly and his shirt slewed out of his gray short pants.

In order to recite the Kipling, Cyril leaned forward against the back of a wing chair and rocked it. He took a deep breath, whipped a forelock of wavy black hair out of his face, and appeared to take the poem straight off the ceiling. “‘If you can keep your head up when all around you / Are losing their heads and blaming it on you —’”

“‘Keep your head,’ not ‘keep your head up,’” corrected Aunt Carmen. “And, Cyril, it’s ‘losing theirs,’ not ‘losing their heads.’”

“‘If you can trust yourself when, when . . .’” he faltered.

“The words are not written on the ceiling, Cyril,” said Aunt Carmen. “Look at your listeners. Gesture with one expressive hand as Kipling himself might have done. Picture Kipling in his pith helmet in the middle of the Indian jungle talking to the Punjabi natives! And Cyril, don’t slouch. You wouldn’t catch Mr. Rudyard Kipling slouching. Begin again, please.”

I half listened to Cyril struggle with the words as I struggled with math. Dust motes spun in the afternoon light. Somewhere in this house were my trains. I wanted to see them. Where would they be? Probably in Cyril’s room, wherever that was. I wanted to see my trains so badly that it hurt, so I muttered “Excuse me,” and left my homework on the dining-room table. I ambled down the hall as if to go to the bathroom. The lavatory was tucked away in a little nook underneath the stairs. I opened the door and closed it firmly so that Aunt Carmen could hear it. I figured it would take Cyril a full twenty minutes to get through the first verse of “If.”

Like a cat, I flew up the stairs and chanced a quick peek in each bedroom. Cyril’s room turned out to be the last in the upstairs hallway. I opened the ten-foot-high mahogany door carefully, minimizing the squeak. A crimson Harvard banner graced the wall over the bed. On the bed were piled footballs, baseballs, phonograph records, and a football helmet with an H on the side. He had tossed swords, a catcher’s mitt, and a bow and arrows in a pile on the floor. A catcher’s mask, chest protector, and shin guards took up the chair. Two tennis racquets lay on the radiator under a cowboy hat. Cyril owned an embossed chrome six-gun set. The holsters hung on the bedpost with their fake ammunition belt, red jewels sparkling on the gunstocks. Dirty socks lay everywhere, but there were no trains. Not a sign of trains or layouts anywhere.

I turned to race downstairs again when I noticed one of Cyril’s school notebooks on the bed. It was open to what seemed to be a book report. What I saw registered shock that dried my mouth. Cyril Pettishanks, born for Harvard, the First National Bank, and beyond, had flunked his fifth-grade book report. His handwriting was no better than a first-grader’s.

Apply yourself, boy! the teacher had written over the failing grade. It gave me the spiny all-overs.

The next Monday it was only a matter of time before Cyril was waist deep in the quagmire of the poem. He had particular trouble with

If you can dream — and not make dreams your master;

If you can think — and not make thoughts your aim,

If you can meet with Triumph and Disaster

And treat those two impostors just the same . . .

Which he got sort of sideways with “if you can be the master of your dreams” and “greet those two impostors.”

“It’s ‘meet with,’ not ‘meet up with,’ Cyril,” corrected Aunt Carmen. “And it’s treat, not greet!” Cyril rocked the wing chair so hard it fell over sideways.

More patient than his sister, Betsy, Cyril reversed and started over and over and over again without complaint. He stood on one foot and then the other. He put his hands in his pockets, which made Aunt Carmen tell him to get his hands out of his pockets because Rudyard Kipling was an English gentleman in the jungle and English gentlemen never put their hands in their pockets when they were in the jungle. “Project your voice. Don’t mumble, Cyril,” she prompted. “Start at ‘If you can make one heap of all your winnings.’”

I would have felt sorry for Cyril if it hadn’t been that he owned my trains out of no fault of mine or virtue of his. Once again I went to the bathroom. I opened the door and closed it firmly as Cyril stumbled, saying, “If you can heap up all your winnings.”

This time I flew through the kitchen and found the door to the basement. I flicked on the overhead light and dashed downstairs. Three entire suits of armor stood under the stairs; piles of furniture and numerous tarnished silver tea sets crammed the corners, but no trains. Along the wall, hundreds of old National Geographics had been stowed in sloppy stacks. There was a dressmaker’s dummy tangled in the antlers of an enormous moose, but no sign of my trains, or even the boxes that might have contained them.

It was two weeks before Christmas that I had a chance to try the Pettishankses’ attic. I waited for Cyril to bungle “If you can talk with crowds and keep your virtue, / Or walk with kings — nor lose the common touch,” which he changed to “If you can talk to crowds and keep on talking.”

“‘Keep your virtue’! Cyril, not ‘keep on talking.’ Begin again, please,” said Aunt Carmen.

I crept upstairs to the attic. Nothing in the attic but summer clothing in mothballed bags hanging everywhere. No trains. Where were they?

Downstairs, Cyril was having a particularly sticky time. I crept back into my homework position at the dining table. Today he only had gotten as far as “If you can force your heart and nerve and sinew,” which he kept fouling up as “heart and soul and sinew.”

“‘Heart and nerve and sinew,’ Cyril. Nerve, not soul. Start again with the beginning of that verse,” said Aunt Carmen.

Cyril did it again. Again he said “heart and soul.”

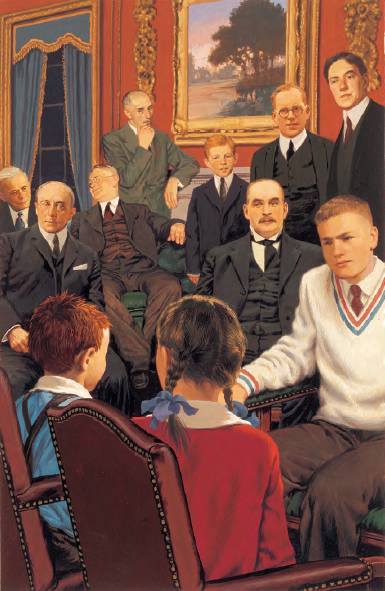

Mr. Pettishanks, Macanudo in hand, suddenly strolled into the room. He clipped off the tip of the cigar with a silver instrument from his pocket, lit it, and blew a long tail of azure smoke into the room.

“How are you doing, son?” he asked. “Have you got the Kipling poem by heart? Shouldn’t take long! When I was your age, I used to memorize thirty lines of Shakespeare a night!”

I stopped in the middle of my history homework. Even Willa Sue went quiet and put her dolls down.

“Let’s hear it, son,” ordered Cyril’s father. “And tuck in that shirt!”

Cyril began to sweat in great flowing beads. His ruddy face retreated to the color of unbaked bread. He inhaled as if for a high dive and sputtered, “‘If you can keep your head on when all around you are losing their heads and blaming . . .’” Cyril lurched through as far as “mastering your dreams and thoughts.” Then he braked on “meet up with Triumph and Disaster.”

A curtain of silence descended on the room. I had actually been rooting for Cyril as he stumbled through the words. I couldn’t help it. He was so afraid of his father, I thought he’d piss his pants. Without realizing it, I mouthed the words along with him, trying to get him to feel a rhyming code: master-disaster, fools and tools. I did not notice that Mr. Pettishanks’s eyes were on me.

“What are you doing, boy?” he asked me, blowing a few rings of smoke my way.

“I’m . . . sir, I was just . . . reciting along with Cyril. I didn’t mean any harm.”

Aunt Carmen’s eyes bored holes in me.

“Cyril, finish the poem!” ordered his father.

About you, doubt you; waiting and hating! My lips prepared to form each syllable for Cyril to follow half a beat later. But Cyril crumbled in a panic attack. I could almost hear his heart pound across the room. He turned and sprinted to the bathroom, where we all heard him sick-up loud and clear.

No one moved. Mr. Pettishanks tapped the ash of his cigar into a green marble ashtray with two bronze Irish setters on it. “Can you finish that poem, boy?” he asked me.

Could I finish Kipling’s “If”? I carried the master copy in the pocket of my coat, encoded for memory. If you can . . . walk with kings intruded on my dreams. If you can bear to hear the truth you’ve spoken came unwanted into the bathtub with me. At lunchtime, all two hundred and eighty-eight words of it were embedded in the very beans of my baked-bean sandwiches. Not only did I have to write the entire thing ten times a night; I had to listen to four other poor fools like Cyril battle through it five afternoons a week.

I stood up — in respect for either Mr. Pettishanks or Kipling, I did not know which.

“May I start at the beginning, sir?” I asked.

“Go ahead, boy!” answered Mr. Pettishanks. He propped a wing-tipped foot up on the seat of a dining chair and watched me like a buzzard. His eyes strayed to Aunt Carmen. Aunt Carmen sat motionless. I suddenly knew that she was, at that moment, a woman expecting execution. Her eyes sought only mine. In her face was equal measure of hope and fear, all bottled up in her wintery blue eyes.

In that instant I understood everything perfectly. Mr. Pettishanks wanted to know if his son’s failure was Cyril’s fault or Aunt Carmen’s fault. If Mr. Pettishanks decided it was Aunt Carmen’s fault that his son had flubbed the poem, she would be fired. If Aunt Carmen were fired by the Pettishankses, word would soon spread around the bridge tables in the River Heights Country Club that Aunt Carmen was a second-rate tutor, and she would lose all her River Heights clients. Mr. Pettishankses was not testing me. He was testing Aunt Carmen.

I did not read from the ceiling. I did not say “meet up with.” I stood straight as a poker and looked Mr. Pettishanks in the eye. I did not stumble over heap of all your winnings. I gestured with my right hand as Kipling might have done, smack in the middle of the Indian jungle. The words flew from my mouth as perfect as a song. I sailed on through all the way to

If you can fill the unforgiving minute

With sixty seconds’ worth of distance run,

Yours is the earth and everything that’s in it,

And — which is more — you’ll be a Man, my son!

without a single hesitation.

“Good,” said Mr. Pettishanks, drawing deeply on his cigar. “You’re a smart boy. I like smart boys. Here’s bus fare and a dime for your trouble. Go down to my bank and give the night watchman this package. Tell’m to put it in the head teller’s drawer.”

He turned to go. Cyril had crept into the room, wiping his mouth on his shirt cuff, his attention on his father as a mouse might eye an owl.

“Learn it, son,” Mr. Pettishanks ordered, his words boring holes into Cyril, “or you’ll find yourself at military prep school for next term. You can bet your bottom dollar they’ll drill some discipline into you starting at five o’clock in the morning!”

“Please, Father, no!” whimpered Cyril.

Mr. Pettishanks grabbed his son by the front of his sweaty shirt. He undid and retied Cyril’s necktie and drew the knot up tight to Cyril’s neck. In a spitting whisper that everyone in the room could hear, he said, “I was cum laude at Harvard. Your grandfather the same, and his father before him. My son is not going to be the first failure in this family. Do you hear me, Cyril?”

“Yes, sir,” said Cyril, his eyes flicking on me.

“It’s two weeks before Christmas. You get it by the first week of the new year, or you’ll find yourself in a cadet’s uniform, drilling on the parade ground at the military prep. Think about it, son. Ice-water showers morning and night. The parade ground has flint chips on the track. They call it The Grinder. They make you do push-ups on it.”

“Yes, sir,” said Cyril. His eyes were dull.

His father released Cyril’s shirt and gave his tie a small yank. “We can’t have the public-school boys creeping up on ya and grabbing your slot at Harvard.” Mr. Pettishanks eyed me and smiled without humor at his own joke.

Cyril tried his best to laugh. But when his father turned again to go, he snarled at me out of the side of his mouth, “You’re a little worm, Ogilvie. I’ll get you!”

“Do as Mr. Pettishanks asks, Oscar,” said Aunt Carmen as if nothing had happened. “Do not linger. Take the number seventeen bus home when your errand is complete.”

Out the front door I went, almost skipping with my sudden freedom. Free. Free as a sparrow in the sky for at least an hour. Unwatched and unremarked upon, I climbed aboard the streetcar and dropped my nickel fare into the slot just like all the free grown-up people. I might as well have joined life in Brazil. I turned my face upward to wherever God might be hiding. A tiny prayer of thanks blossomed in my heart, and I sent it skyward. Somehow I had pulled the lucky lever and got my dad instead of Mr. Pettishanks. Cyril would never learn that poem. With all his money and privilege, he was going to wind up in Missouri Military Prep, just over the river from Cairo. Everybody knew what went on there. Sometimes we could see them drill and hear them shouting on the wind. My dad said, “The Prep is supposed to be a school for troublesome boys, but it’s really a school for the boys of troublesome dads. The Prep spits those boys out four years later as nasty little cadets.”

The bus took twenty minutes to reach downtown Cairo and the intersection of Center Street and Washington Avenue. I alighted at the corner and went to the bronze filigreed doors of the bank. The First National was a heroic granite building. Ten fluted Greek columns held up the capital out in front. The bank’s name was chiseled in the marble for all Cairo and the surrounding world to read.

Bankers’ hours ended at three, but there was a bell on the side of the double doors, and I rang it. Waiting in the cold afternoon for the night watchman, I turned to the right to one of the darkened display windows. Suddenly spotlights flared on. All that was in the Christmas display window came to life. There was a layout of twenty different trains in a Christmas landscape. The Blue Comet whizzed by. It was my Blue Comet. Mr. Pettishanks had it running lakeside on the South Shore Line.

Before I could even take it in, the night watchman opened the bank door and saluted me with a smile.

“Mr. Applegate!” I shouted.

“Oscar,” said Aunt Carmen after grace and before supper that evening, “you are excused from writing any further copies of Mr. Kipling’s poem.” She gave me a frosty smile.

“Oh, thank you, ma’am,” I said. “That’s a relief !” A grin, exactly like my dad’s very own, widened across my face.

“You saved our bacon, Oscar,” piped up Willie Sue.

Aunt Carmen frowned at Willa Sue and put her finger to her lips.

“Mama, that’s what you said on the bus ’fore Oscar came home: ‘Oscar Ogilvie Jr. certainly saved our bacon today.’ I heard it with my own ears.”

“Oscar,” said Aunt Carmen, “you did remarkably well today.”

“Thank you, ma’am. I sure know that poem by heart.”

She asked me, “Did you know, Oscar, that the town of Cairo celebrates the Fourth of July with a fifth-grader reciting a speech from history? Each year one boy or girl is chosen from the schools. You might be the one selected if you practice. Perhaps we should prepare you for a few more recitations.”

“It would certainly make Mama look good,” said Willa Sue. “If you got to give the Fourth of July speech in front of the whole town, why, everybody’d know you were Mama’s nephew! We’d get lots more jobs and a pay raise. ’Course you’d have to do it without messing up!”

“Hush, Willa Sue,” said Aunt Carmen, but the cat was out of the bag.

“More speeches?” I asked. I stopped midspoon in my attack on the navy-bean-and-cod-cheek casserole. I knew all about the Fourth of July. Dad and I never missed the town picnic. We loved the band concerts. We marched in the parade. But when the hour came and some pasty-faced kid with glasses got up to deliver Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points, Dad said, “Let’s get out while the getting’s good!”

Aunt Carmen did not read the thoughts in my head. She plowed on informatively as she ate. “There’s Theodore Roosevelt’s Man in the Arena, of course. Then there’s George Washington’s Farewell. How about Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address? That’s a good one!” she said.

I felt the color drain from my cheeks and the sense from my mind. “Why don’t I . . . look some of them over,” I finally managed to suggest.

Famous Speeches of Famous Men was on my bedside table that night.

Aunt Carmen and I arrived at a bargain, without ever discussing a single detail of it out loud. She would allow me to visit my trains in the First National Bank in the afternoons after lessons. I would have Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address committed to memory by the next July Fourth.

“Well, howdy!” said Mr. Applegate when I pounded on the doors of the bank. He flipped the alarm switch off and swung open the fifteen-foot-high bronze doors to let me in. He showed me how to slip the dead bolt bar that relocked the doors and flip the alarm back on again.

“All we need, Oscar,” said Mr. Applegate, “is a false alarm. The cops’ll come swarming down here, sirens blazing, and we’ll be in trouble up to our keisters with old Pettishanks!”

Mr. Applegate made enough money from his new job as night watchman to buy a thermos bottle and hot chocolate to fill it. This we shared every afternoon before tackling the trains. In front of the massive lobby-wide layout was a small coin-operated box decorated with holly and red Christmas bows. The sign said

YOUNG SAVERS — JOIN THE FIRST NATIONAL’S CHRISTMAS CLUB!

EARN A DIME FOR EVERY DOLLAR SAVED.

ONE DIME RUNS THE TRAINS FOR FIVE MINUTES!

I did not have to join the Christmas Club. Mr. Applegate knew how to run the trains for free by using a dime glued to a string over and over again. I kept the dime hung around my neck along with my Holy Name medal.

Mr. Pettishanks had placed my Blue Comet train on the South Shore Commuter Line. It ran the round-trip from South Bend to Chicago. I watched it run several loops before taking my eyes off it. No question it was my own train. On the side of the engine was a small scrape that my dad had carefully sanded and afterward repainted with cobalt-blue enamel. In its observation car were the two seats Dad and I had adjusted just so for perfect viewing when we would go down the Jersey Shore and see the great Atlantic Ocean for the first time. The windows had always been kept polished by my dad with a chamois cloth, and the nickel-plated side rods along the engine gleamed like silver.