3

He left Candor Mesa without a good-bye to anyone. His acquaintances there would understand; they often flew away themselves for a time. They would all be back someday, to soar over the canyons and then spend their evenings together on Shining Mesa. And so he left. Down into the immensity of Melas Chasma, then downcanyon again, east into Coprates. For many hours he floated in that world, over the 61 glacier, past embayment after embayment, buttress after buttress, until he was through the Dover Gate and out over the broadening divergence of Capri and Eos chasmas. Then above the ice-filled chaoses, the crackled ice smoother by far than the drowned land below it had been. Then across the rough jumble of Margaritifer Terra, and north, following the piste toward Burroughs; then, as the piste approached Libya Station, he banked off to the northeast, toward Elysium.

The Elysium massif was now a continent in the northern sea. The narrow strait separating it from the southern mainland was a flat stretch of black water and white tabular bergs, punctuated by the stack islands which had been the Aeolis Mensa. The North Sea hydrologists wanted this strait liquid, so that currents could make their way through it from Isidis Bay to Amazonis Bay. To help achieve this liquidity they had placed a nuclear-reactor complex at the west end of the strait, and pumped most of its energy into the water there, creating an artificial polynya where the surface stayed liquid year-round, and a temperate mesoclimate on the slopes on each side of the strait. The reactors’ steam plumes were visible to Nirgal from far up the Great Escarpment, and as he floated down the slope he crossed over thickening forests of fir and ginkgo. There was a cable across the western entrance to the strait, emplaced to snag icebergs floating in on the current. He flew directly over the bergjam west of the cable, and looked down on chunks of ice like floating driftglass. Then over the black open water of the strait— the biggest stretch of open water he had ever seen on Mars. For twenty kilometers he floated over the open water, exclaiming out loud at the sight. Then ahead an immense airy bridge arced over the strait. The black-violet plate of water below it was dotted with sailboats, ferries, long barges, all trailing the white Vs of their wakes. Nirgal floated over them, circling the bridge twice to marvel at the sight— like nothing he had ever seen on Mars before: water, the sea, a whole future world.

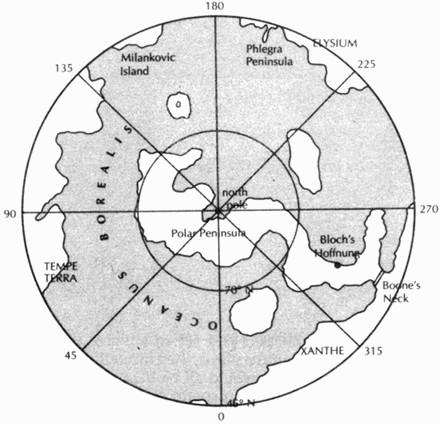

NORTH SEA POLAR PROJECTION

• • •

He continued north, rising over the plains of Cerberus, past the volcano Albor Tholus, a steep ash cone on the side of Elysium Mons. The much bigger Elysium Mons was steep as well, with a Fuji-esque profile that served as the label illustration for many agricultural co-ops in the region. Sprawled over the plain under the volcano were farms, mostly ragged at the edges, often terraced, and usually divided by strips or patches of forest. Young immature orchards dotted the higher parts of the plain, each tree in a pot; closer to the sea were great fields of wheat and corn, cut by windbreaks of olive and eucalyptus. Just ten degrees north of the equator, blessed with rainy mild winters, and then lots of hot sunny days: the people there called it the Mediterranean of Mars.

Farther north Nirgal followed the west coast as it rose up out of a line of foundered icebergs embroidering the edge of the ice sea. As he looked down at the expanse of land below, he had to agree with the general wisdom: Elysium was beautiful. This western coastal strip was the most populated region, he had heard. The coast was fractured by a number of fossae, and square harbors were being built where these canyons plunged into the ice— Tyre, Sidon, Pyriphlegethon, Hertzka, Morris. Often stone breakwaters stopped the ice, and marinas were in place behind the breakwaters, filled with fleets of small boats, all waiting for open passage.

At Hertzka Nirgal turned east and inland, and flew up the gentle slope of the Elysian massif, passing over garden belts banding the land. Here the majority of Elysium’s thousands lived, in intensively cultivated agricultural-residential zones, sloping up into the higher country between Elysium Mons and its northern spur cone, Hecates Tholus. Between the great volcano and its daughter peak, Nirgal flew through the bare rock saddle of the pass, flung like a little cloud by the pass wind.

Elysium’s east slope looked nothing like the west; it was bare rough torn rock, heavily sand-drifted, maintained in nearly its primordial condition by the rain shadow of the massif. Only near the eastern coast did Nirgal see greenery below him again, no doubt nourished by trade winds and winter fogs. The towns on the east side were like oases, strung on the thread of an island-circling piste.

At the far northeast end of the island, the ragged old hills of the Phlegra Montes ran far out into the ice, forming a spiny peninsula. Somewhere around here was where that young woman had seen Hiroko. As Nirgal flew up the western side of the Phlegras, it struck him as a likely place to find her; it was a wild and Martian place. The Phlegras, like many of the great mountain ranges of Mars, was the only remaining arc of an ancient impact basin’s rim. Every other aspect of that basin had long since disappeared. But the Phlegras still stood as witness to a minute of inconceivable violence— impact of a hundred-kilometer asteroid, big pieces of the lithosphere melted and shoved sideways, other pieces tossed into the air to fall in concentric rings around the impact point, with much of the rock metamorphosed instantly into minerals much harder than their originals. After that trauma the wind had cut away at things, leaving behind only these hard hills.

There were settlements out here, of course, as there were everywhere, in the sinkholes and dead-end valleys and on the passes overlooking the sea. Isolated farms, villages of ten or twenty or a hundred. It looked like Iceland. There were always people who liked such remote land. One village perched on a flat knob a hundred meters over the sea was called Nuannaarpoq, which was Inuit for “taking extravagant pleasure in being alive.” These villagers and all the others in the Phlegras could float to the rest of Elysium on blimps, or walk down to the circum-Elysian piste and catch a ride. For this coast in particular, the nearest town would be a shapely harbor called Firewater, on the west side of the Phlegras where they first became a peninsula. The town stood on a bench at the end of a squarish bay, and when Nirgal spotted it, he descended onto the tiny airstrip at the upper end of town, and then checked into a boardinghouse on the main square, behind the docks standing over the ice-sheeted marina.

In the days that followed, he flew out along the coast in both directions, visiting farm after farm. He met a lot of interesting people, but none of them was Hiroko, or anyone from the Zygote crowd— not even any of their associates. It was even a little suspicious; a fair number of issei lived in the region, but every one of them denied ever having met Hiroko or any of her group. Yet all of them were farming with great success, in rocky wilderness that did not look easy to farm— cultivating exquisite little oases of agricultural productivity— living the lives of believers in viriditas— but no, never met her. Barely remembered who she was. One ancient geezer of an American laughed in his face. “Whachall think, we got a guru? We gonna lead ya to our guru?”

After three weeks Nirgal had found no sign of her at all. He had to give up on the Phlegra Montes. There was no other choice.

• • •

Ceaseless wandering. It did not make sense to search for a single person over the vast surface of a world. It was an impossible project. But in some villages there were rumors, and sometimes sightings. Always one more rumor, sometimes one good sighting. She was everywhere and nowhere. Many descriptions but never a photo, many stories but never a wrist message. Sax was convinced she was out there, Coyote was sure she wasn’t. It didn’t matter; if she was out there, she was hiding. Or leading him on a wild-goose chase. It made him angry when he thought of it that way. He would not search for her.

Yet he could not stop moving. If he stayed in one place for more than a week, he began to feel nervous and fretful in a way he had never felt in his life. It was like an illness, with tension everywhere in his muscles, but concentrated in his stomach; an elevated temperature; inability to focus on his thoughts; an urge to fly. And so he would fly, from village to town to station to caravanserai. Some days he let the wind carry him where it would. He had always been a nomad, no reason to stop now. A change in the form of government, why should that make a difference in the way he lived? The winds of Mars were amazing. Strong, irregular, loud, ceaseless live beings, at play.

Sometimes the wind carried him out over the northern sea, and he flew all day and never saw anything but ice and water, as if Mars were an ocean planet. That was Vastitas Borealis— the Vast North, now ice. The ice was in some places flat, in others shattered; sometimes white, sometimes discolored; the red of dust, or the black of snow algae, or the jade of ice algae, or the warm blue of clear ice. In some places big dust storms had stalled and dropped their loads, and then the wind had carved the detritus so that little dune fields were created, looking just like old Vastitas. In some places ice carried on currents had crashed over crater-rim reefs, making circular pressure ridges; in other places ice from different currents had crashed together, creating straight pressure ridges, like dragon backs.

Open water was black, or the various purples of the sky. There was a lot of it— polynyas, leads, cracks, patches— perhaps a third of the sea’s surface now. Even more common were melt lakes lying on the surface of the ice, their water white and sky-colored both, which at times looked a brilliant light violet but other times separated out into the two colors; yes, it was another version of the green and the white, the infolded world, two in one. As always he found the sight of a double color disturbing, fascinating. The secret of the world.

Many of the big drilling platforms in Vastitas had been seized by Reds and blown up: black wreckage scattered over white ice. Other platforms were defended by greens, and being used now to melt the ice: large polynyas stretched to the east of these platforms, and the open water steamed, as if clouds were pouring up out of a submarine sky.

In the clouds, in the wind. The southern shore of the northern sea was a succession of gulfs and headlands, bays and peninsulas, fjords and capes, seastacks and low archipelagoes. Nirgal followed it for day after day, landing in the late afternoons at little new seaside settlements. He saw crater islands with interiors lower than the ice and water outside the rim. He saw some places where the ice seemed to be receding, so that bordering the ice were black strands, raked by parallel lines running down to ragged drift errata of jumbled rock and ice. Would these strands flood again, or would they grow wider still? No one in these seaside towns knew. No one knew where the coastline would stabilize. The settlements here were made to be moved. Diked polders showed that some people were apparently testing the newly exposed land’s fertility. Fringing the white ice, green crop rows.

North of Utopia he passed over a low peninsula that extended from the Great Escarpment all the way to the north polar island, the only break in the world-wrapping ocean. A big settlement on this low land, called Boone’s Neck, was half-tented and half in the open. The settlement’s occupants were engaged in cutting a canal through the peninsula.

A wind blew north and Nirgal followed it. The winds hummed, whooshed, keened. On some days they shrieked. Live beings, at war. In the sea on both sides of the long low peninsula were tabular ice shelfs. Tall mountains of jade ice broke through these white sheets. No one lived up here, but Nirgal was not searching anymore— he had given up, very near despair, and was just floating, letting the winds take him like a dandelion seed: over the ice sea, shattered white; over open purple water, lined by sun-bright waves. Then the peninsula widened to become the polar island, a white bumpy land in the sea ice. No sign of the primeval swirl pattern of melt valleys. That world was gone.

Over the other side of the world and the North Sea, over Orcas Island on the east flank of Elysium, down over Cimmeria again. Floating like a seed. Some days the world went black and white: icebergs on the sea, looking into the sun; tundra swans against black cliffs; black guillemots flying over the ice; snow geese. And nothing else in all the day.

Ceaseless wandering. He flew around the northern parts of the world two or three times, looking down at the land and the ice, at all the changes taking place everywhere, at all the little settlements huddling in their tents, or out braving the cold winds. But all the looking in the world couldn’t make the sorrow go away.

• • •

One day he came on a new harbor town at the entry to the long skinny fjord of Marwth Vallis, and found his Zygote crèche mates Rachel and Tiu had moved there. Nirgal hugged them, and over a dinner and afterward he stared at their oh-so-familiar faces with intense pleasure. Hiroko was gone but his brothers and sisters remained, and that was something; proof that his childhood was real. And despite all the years they looked just like they had when they were children; there was no real difference. Rachel and he had been friends, she had had a crush on him in the early years, and they had kissed in the baths; he recalled with a little shiver a time when she had kissed him in one ear, Jackie in the other. And, though he had almost forgotten it, he had lost his virginity with Rachel, one afternoon in the baths, shortly before Jackie had taken him out into the dunes by the lake. Yes, one afternoon, almost accidentally, when their kissing had suddenly become urgent and exploratory, a matter of their bodies moving outside their own volition.

Now she regarded him fondly— a woman his age, her face a map of laugh lines, cheery and bold. She may have recalled their early encounter as little as he did— hard to say what his siblings remembered of their shared bizarre childhood— but she looked like she remembered. She had always been friendly, and she was again now. He told her about his flights around the world, carried by the ceaseless winds, diving slowly against the blimp’s buoyancy down to one little habitation after another, asking after Hiroko.

Rachel shook her head, smiling ironically. “If she’s out there, she’s out there. But you could look forever and never find her.”

Nirgal heaved a troubled sigh, and she laughed and tousled his hair.

“Don’t look for her.”

That evening he walked along the strand, just uphill from the devastated berg-strewn shoreline of the northern sea. He felt in his body that he needed to walk, to run. Flying was too easy, it was a dissociation from the world— things were small and distant— again, it was the wrong end of the telescope. He needed to walk.

Still he flew. As he flew, however, he looked more closely at the land. Heath, moor, streamside meadows. A creek falling directly into the sea over a short drop, another one crossing a beach. Salt creeks into a fresh ocean. In some places they had planted forests, to try to cut down on dust storms that originated in this area. There were still dust storms, but the trees of the forest were saplings still. Hiroko might be able to sort it out. Don’t look for her. Look at the land.

• • •

He flew back to Sabishii. There was still a lot of work to be done there, clearing away burned buildings and then building new ones. Some construction co-ops were still accepting new members. One was doing reconstruction but was also building blimps and other fliers, including some experimental birdsuits. He talked with them about joining.

He left his blimpglider in town with them, and took long runs out onto the high moors east of Sabishii. He had run these uplands during his student years. A lot of the ridge runs were familiar still; beyond them, new ground. A high land, with its moorish life. Big kami boulders stood here and there on the rumpled land, like sentinels.

One afternoon, running an unfamiliar ridge, he looked down into a small high basin like a shallow bowl, with a break opening to lower land to the west. Like a glacial cirque, though more likely it was an eroded crater with a break in its rim, making a horseshoe ridge. About a kilometer across— quite shallow. Just a rumple among the many rumples on the Tyrrhena massif. From the encircling ridge the horizons were far away, the land below lumpy and irregular.

It seemed familiar. Possibly he had visited it on an overnighter in his student years. He hiked slowly down into the basin, and still felt like he was on top of the massif; something about the dark clean indigo of the sky, the spacious long view out the gap to the west. Clouds rolled overhead like great rounded icebergs, dropping dry granular snow, which was chased into cracks or out of the basin entirely by the hard wind. On the circling ridge, near the northwest point of the horseshoe, there was a boulder sitting like a stone hut. It stood on four points on the ridge, a dolmen worn to the smoothness of an old tooth. The sky over it lapis lazuli.

Nirgal walked back down to Sabishii and looked into the matter. The basin was untended, according to the maps and records of the Tyrrhena Massif Areography and Ecopoesis Council. They were pleased he was interested. “The high basins are hard,” they told him. “Very little grows. It’s a long project.”

“Good.”

“You’ll have to grow most of your food in greenhouses. Potatoes, however— once you get enough soil, of course—”

Nirgal nodded.

They asked him to drop by the village of Dingboche, the one nearest the basin, and make sure no one there had plans for it.

So he drove back up, in a little caravan with Tariki and Rachel and Tiu and some other friends who had gathered to help. They drove over a low ridge and found Dingboche, set on a little wadi that was now being farmed, mostly in hardscrabble potato fields. There had been a snowstorm, and all the fields were white rectangles, divided by low black walls of stacked stones. A number of long low stone houses, with plate-rock roofs and thick square chimneys, were scattered among the fields, with several more clustered at the village’s upper end. The longest building in this cluster was a two-storied teahouse, with a big mattress-filled room to accommodate visitors.

In Dingboche as in much of the southern highlands the gift economy still predominated, and Nirgal and his companions had to endure a near potlatching when they stayed for the night. The locals were very happy when he inquired about the high basin, which they called variously the little horseshoe, or the upper hand. “It needs looking after.” They offered to help him get started.

So they went up to the high cirque in a little caravan, and dumped a load of gear on the ridge near the house boulder, and stuck around long enough to clear a first little field of stones, walling it with what they cleared. A couple of them experienced in construction helped him to make the first incisions into the ridge boulder. During this noisy drilling some of the Dingboche locals cut away at the exterior of the rock, carving in Sanskrit lettering Om Mani Padme Hum, as seen on innumerable mani stones in the Himalayas, and now all over the southern highlands. The locals chipped away the rock between the fat cursive letters, so that the letters stood out in raised relief against a rougher, lighter background. As for the boulder house itself, eventually he would have four rooms hacked out of the boulder, with triple-paned windows, solar panels for heat and power, water from a snowmelt pumped up to a tank placed higher on the ridge, and a composting toilet and graywater facility.

Then they were off. Nirgal had the basin to himself.

He walked around on it for many days without doing anything but looking. Only the tiniest part of the basin would be his farm— just some small fields inside low stone walls, and a greenhouse for vegetables. And a cottage industry, he wasn’t sure what. It wouldn’t be self-sufficient, but it would be settling in. A project.

And then there was the basin itself. A small channel already ran down the opening out to the west, as if to suggest a watershed. The cupped hand of rock was already a micro-climate, tilted to the sun, slightly sheltered from the winds. He would be an ecopoet.