Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 140, Nos. 3 & 4. Whole Nos. 853 & 854, September/October 2012

Death of a Drama Queen

by Doug Allyn

Doug Allyn’s 2011 story “A Penny for the Boatman” was a standout not only for EQMM readers, who awarded it second place in the 2011 Readers Award vote, but for members of the Short Mystery Fiction Society, who nominated the story for a best novella Derringer Award. In December of 2011, for the first time, the Michigan author made one of his published short stories available in a stand-alone Kindle edition (see “The Christmas Mitzvah”).

“I’m pregnant,” Sherry said.

The background noise in the restaurant suddenly seemed to fade a bit. I began doing the math in my head... then stopped. It had been far too long.

“Well?” she prompted. “Say something.”

“Congratulations,” I said. “Or not. Which is it?”

“I’m still working that part out.” She looked away, glancing around the crowded dining room. The Jury’s Inn is a block from Hauser Center, the police station where I work. As a local TV reporter, Sherry spends a lot of time here. Everywhere she looked, people would smile at her and nod. She’s a petite blonde, strikingly attractive, and a northern Michigan celebrity.

“Is there a problem?” I asked.

“More than one. The biggest is my boss. Jack Milano.”

“The station manager? What about him?”

“He’s... every ambitious girl’s mistake, Dylan. We were at a convention, we were both a little buzzed and got carried away. He’s tried to follow up on it since, to make more of it than it was, but he’s married.”

“Have you told him about your situation?”

“I dropped it on him as soon as I found out,” she said, with the imp’s grin I remembered all too well. “I was hoping it would scare him off.”

“Did it?”

“I wish.” She sighed. “Instead, he started blathering about leaving his wife, starting a new life together. This could be a total disaster for me, Dylan. The network is cutting back. If it gets out that Jack and I were involved, New York would fire us both.”

“That is a problem.”

“And not the only one,” she said.

“Rob Gilchrist,” I said.

“What?”

“Rumor has it you’ve been seeing Rob.”

“Are you keeping tabs on me, LaCrosse? I’m flattered.”

“Valhalla’s a small town. People talk. And Rob is a major catch.”

“Now you’re being snide.”

“No, I mean it. You always wanted to be on top of the heap. The Gilchrists are old money. Lumber mills, paper mills, you name it, they own it.”

“My God, do you really think I’m that shallow?”

I almost said yes, but didn’t want to start an argument. Fighting with Sherry is no fun at all. She’s bright and perceptive, with a reporter’s instinct for the jugular. Her gibes can pierce you to the bone. She’s always sorry after a spat, always apologizes with tears, makeup sex, or both. But afterward, at three in the morning, the barbs fester under your skin like snakebites. Because they’re at least partly true.

“Okay, how can I help, Sherry?” I asked.

“I need some advice, Dylan.”

“Why me?”

“Because we may be over, love, but I think you still care about me a little. And I trust you. You were always terrific at keeping secrets. Especially your own. So? Can you help me out here? What should I do?”

“About Rob?”

“No, about my situation.”

“Ah.” I sipped my coffee, considering that one for a moment. For a split second it occurred to me she might be probing my feelings, hoping to restart our affair. Not likely. She said it herself. We were over. A part of me still regretted that.

“I know how you feel about your family, Dylan,” she said, leaning in, lowering her voice. “They’re terrific. But I grew up in foster care. And it wasn’t wonderful. Being a mother is an awesome responsibility. My mom, whoever she was, obviously wasn’t wired for it. Nor am I.”

“It sounds like you’ve already made up your mind.”

“I still want to know what you think. The truth.”

“Fair enough. I think that particular decision belongs to the woman who has to make it. Have you told the father?”

“No.”

There was something in her tone.

“Do you know who...?” I asked.

“No.” She shook her head miserably. “And don’t get all judgmental on me, LaCrosse.”

“I’m the last one who could throw stones, Sherry. But if you’re asking for advice, I think that should be your next move. You need to know.”

“Why?” she asked. “What’s the difference?”

“If it’s Rob, that’ll close the books on your boss, Milano... if that’s what you want. And it might convince Rob to marry you. If that’s what you want. And if you decide to lie—”

“Lie? About a thing like this? My God, Dylan, what kind of person do you think I am?”

“You wanted advice.”

“I also asked you a question.”

“And I’m saying that in affairs of the heart, the truth isn’t your only option. If a new love asks you how many lovers you’ve had before, you don’t necessarily owe him the truth, besides...” I paused a beat, waiting.

“You can’t handle the truth!” we said together, both of us doing our best Jack Nicholson, turning a few heads at nearby tables. And for a moment I remembered how much fun we used to have. Before we ran off the rails.

“Fair enough.” She nodded, smiling now. “Your advice is right on the money, as always, LaCrosse. Totally objective.”

That wasn’t quite true. When you care for someone a lot, you never really stop caring. Or at least I don’t. Sherry knew that. And she played on it sometimes.

“There is one more thing you could do for me,” she said, stirring her coffee. Avoiding my eyes.

“I thought there might be,” I said drily. “What is it?”

“Would you check into their backgrounds for me, Dylan? Let me know if there are any land mines I should avoid?”

“Hell, you’re a reporter, you can run a background check as easily as I can.”

“Reading the news on local TV doesn’t make me Diane Sawyer, LaCrosse. I can’t use station resources to check up on my boss, and I don’t have access to the Law Enforcement Information Net.”

My ears perked up. “The L.E.I.N. is for criminal suspects. I can’t use it for a personal situation. Why would their names be on it, anyway?”

“I hope they’re not, but...”

“Is there something you’re not telling me, Sherry?”

“No, but...”

“But what?”

She took a deep breath. “It’s... a little hard to explain, Dylan. You know my background. I grew up tough. I’m a newswoman, which makes me a realist, I think. But lately... I read a story in a college lit class once. ‘Something Wicked This Way Comes.’ Ray Bradbury, I think. That’s how I feel. Like something bad is coming.”

“Like what?”

“I don’t know. It’s probably just a case of raging hormones, but I’d feel better if you checked things out. I’ll pay for your time. I know how pathetic a cop’s salary is.”

“I’d work for food, but I’ve tasted your cooking.”

“Touché, love. Call me,” she said, rising to go. She paused for a moment, looking down at me.

“I miss us sometimes,” she said.

“Me too,” I admitted.

And for a moment, with her golden hair haloed against the Inn’s wagon-wheel candelabra, I felt a sharp pang of loss. Sherry was an exceptional woman, bright and fun and perky. And the neediest person I’d ever known.

Heads turned as she walked out of the restaurant. They always did.

We’d been wrong for each other, no question about that. Our affair had flared like a Roman candle, and burned out almost as quickly. But it had been intense while it lasted. For me, at least.

And now? We were less than lovers, but more than friends. The French probably have a phrase for it. Exes avec regrets? Something like that.

But when Sherry had spoken about feeling uneasy, there’d been none of the usual mischief in her eyes. That bothered me. Sherry was practically fearless. If she was worried about something, so was I.

Besides, I’d told her a half-truth. As a detective on the North Shore Major Crimes unit, there are legal restrictions on my ability to run background checks.

Plugging a name into the Law Enforcement Information Network requires a case number, a badge number, and my personal password. Every request is logged and filed for future reference.

But the L.E.I.N. isn’t the only way to get information. The Internet knows everything about everybody and it’s an open book if you know where to look. St. Mark Zuckerberg had it right: The Right to Privacy is like Santa Claus, a quaint little notion nobody really believes in anymore.

I ran background checks on Jack Milano and Rob Gilchrist, off the books. And I turned up a few interesting bits of information. I left a message on Sherry’s voicemail, but she didn’t call me back.

Ever.

She was already dead.

Six in the morning, I was toweling down after a shower when my cell phone gurgled. My partner, Zina Redfern.

“Dylan? Are you awake?”

“Sort of. What’s up?”

“We have a probable homicide and a major problem.”

“Who’s the victim?”

“Sherry Sinclair. The TV reporter.”

Dead air for a moment.

“Sweet Jesus,” somebody said. Me, I suppose. All the oxygen seemed to go out of the room. “I’ll be there in—”

“No! You stay right where you are. That’s an order.”

“You can’t—”

“It’s not coming from me, Dylan, it’s from Chief Kazmarek. You can’t work the case, and you know it.”

I wanted to argue, but didn’t. She was right.

“Okay. What the hell happened, Zee?”

“Her car went off the Beame Hill turnout west of Valhalla. It rolled down the embankment and went into the creek at the bottom, upside down. The body’s been removed, and the state police forensics unit is already working the crime scene.”

“What about the time line?”

“We aren’t sure yet. At least twenty-four hours ago.”

The twenty-four was a rough guess, the onset of her rigor mortis and its passing. “You said it was a probable homicide?”

“There’s some damage to the trunk of her car, Dylan. Like it was pushed over the embankment. But there’s no sign of a second vehicle, and the EMT said her throat was bruised. The airbags deployed. He doubts she was killed in the crash.”

I absorbed that. “What else?”

“You know what else. By North Shore standards Sherry Sinclair was a celebrity, and it’s common knowledge you two were involved at one point. That puts you on the suspect list, Dylan. You know the drill, so let’s get you cleared. When did you see her last?”

“Last week. Friday. We met for coffee, at the Jury’s Inn.”

“Socially? Romantically?”

“Socially. We’ve been over for a while, but we stayed friends.”

“With benefits?”

“Sexually, in other words?”

“In exactly those words.”

“No, we haven’t been involved in that way for nearly a year.” I’m pregnant, Sherry said. And I began doing the math... Zee was saying something.

“I’m sorry,” I said. “You lost me. What did you say?”

“As soon as we have a time of death, I’ll need an alibi statement. Chief

Kazmarek has ordered me to take the lead on the case. Van Duzen will back me up. In the meantime, you have to stay clear of this, Dylan. Are we gonna have a problem?”

I didn’t say anything.

“Dylan?”

“I’m thinking.”

“Don’t think. You know the chief’s right.”

I didn’t say anything.

“Damn it, LaCrosse—”

“Okay, okay,” I said. “I promise I won’t put you in a situation.”

“You’ll stay out of it?”

“I won’t put you in a situation,” I repeated. Which wasn’t quite the same thing. And we both knew it.

It was Zina’s turn to go silent.

“I can live with that,” she sighed. “So. Now that you’re officially sitting on the sidelines, what have you got for me?”

“For openers, you’re not looking at one homicide,” I said. “You’re probably looking at two.”

As soon as I hung up, I threw on jeans and a leather jacket, scrambled into my Jeep, and headed straight for the Beame Hill turnout. I hadn’t promised to stay away, and Zee knew better than to expect it.

Michigan’s North Shore counties are a study in contrasts. Along the lakefront, real estate is sky high, posh condos and hotels are sprouting like anthills, funded by Internet money. Newcomer money.

Ten miles inland you’re in much rougher country, rolling, timbered hills, sparsely populated with blink-and-you’ve-missed-it villages with ramshackle houses scattered along the edges of the Huron State Forest, an untracked territory bigger than half the nations in the U.N.

Northern police jurisdictions are a patchwork quilt as well. The state police cover the freeways, and share coverage of the interior with the sheriff’s departments and the Department of Natural Resources. Murder and mayhem fall to the North Shore Major Crimes unit based in Valhalla. My unit. As second in command, I should have been leading this investigation. But there was nothing ordinary about this case.

It was late October, and a fairy dusting of early snow was drifting down as I rolled up on the crime scene. A state police cruiser was pulling out as I pulled over to park on the gravel shoulder. A Vale County sheriff’s prowlie was blocking the turnout, with a deputy waving gawkers past. Bergmann.

He shot me with his finger as I trotted past. I didn’t shoot back.

Zina Redfern was halfway down the embankment, scanning the tire tracks. Below her, the frame and tires of Sherry’s Mustang were visible above the shallow creek. State-police evidence techs were searching the banks, though I doubted they’d find much. Most of the evidence would be in the car.

Zee Redfern glanced up, saw me coming, then went back to studying the tread marks. We’ve been partners since she transferred up to the North Shore force from Flint. We’re good friends, a good team.

Zee’s Native American, Anishnabeg, but she grew up in Gangland, on Flint’s north side. Doubly tough for a sidewalk Indian girl on her own. I asked her once how she stayed out of the crews.

“I didn’t. I took Police Science courses at Mott J.C., became an auxiliary officer, then hired on to the Flint force on my nineteenth birthday. Cops wear colors, pack iron, and you’re blue till you die. Sounds like a gang to me.”

A short, squared-off woman with raven hair, she takes the term “plainclothes officer” seriously. She was wearing her usual Johnny Cash black, a bulky nylon POLICE parka over black jeans, a black watch cap pulled down around her ears.

Even her combat boots are the real deal. LawPro Pursuits with steel toes. She packs a Fairbairn fighting knife strapped to one ankle, a Smith Airweight .38 on the other. You’d think she’d clank when she walks. She doesn’t.

She didn’t look surprised to see me, but she wasn’t happy either.

“Am I going to have a problem with you?” she asked, straightening up.

“I promised I wouldn’t put you in a situation, and I won’t. But Sherry was a friend and there’s no way I can just stand aside. So? Let’s trade. Tell me what you’ve got, I’ll swap you what I know. Then I’ll get out of your hair.”

“You first.”

“Fine. There’s no way Sherry got run off this turnout accidentally. She lives in Briarwood a few miles up the road. It’s a gated community, guests have to sign in and out. This place is a lovers’ lane. Handy if you want to meet somebody on the quiet.”

“Somebody like you, for instance?”

“We parked here once. When we broke up. A year ago. Your turn.”

“The car was spotted by a hiker, upside down in the creek at the bottom of the ravine. It didn’t hit hard, and the airbags would have absorbed most of the impact. She could have gotten out if she was conscious. The pathologist’s best guess is, she was already dead when the car went in.”

“On the phone you mentioned her throat was bruised?”

“It didn’t look like strangulation, but there was a livid mark and the hyoid was crushed. Maybe a judo strike to the larynx. You had hand-to-hand training in the service, right?”

“Along with a million other guys. The same course you had at the Academy. Was she assaulted?”

“There was no evidence of that, no bruises or torn clothing. Whose idea was it to break off your relationship?”

“Mine.”

“Why?”

“That’s... a bit complicated.”

“It always is. Give me a DD-5 version, Dylan.”

I mulled that over for a moment. How to condense a serious slice of my life into a police report? Straight up. Tear the damn bandage off.

“My last year in the Air Force, I came home on leave from Iraq. Sherry interviewed me for the station, a local interest story.”

“And sparks flew?”

“Something like that. It started as an overnight fling. But after I went back, we stayed in touch. E-mailed almost every day, hooked up whenever I could get leave.”

“So the affair was... serious?”

“It was for me. I bought a ring.”

“Wow.” Zee’s eyebrows went up. “What happened?”

“I got posted T.D.Y. to Barksdale Air Base in Louisiana—”

“T.D.Y.?”

“Temporary duty. I was an investigator with the Air Police. They flew me in to teach a course on crime scenes. The base is just up the road from New Orleans, and it was Mardi Gras week. Sherry flew down to party. I planned to pop the question over the weekend.”

“And did you?”

“Not quite. Three in the morning, we were in a disco in the French Quarter when the DJ announced the next tune would be topless. Sherry stripped off her blouse and kept right on dancing with the rest of the wild girls. Half naked in a room full of strangers and she never missed a step. And every doubt I had about our relationship came into focus.”

“Just because she flashed for a song?” Zee asked doubtfully. “Why? You’re no prude.”

“Not a bit. It was Mardi Gras. The whole scene was totally hot. People were making love in the streets.”

“Then what? It bothered you that she went overboard?”

“That’s just it, she didn’t. It wasn’t a lapse. She needed to be out there in front of that crowd. That’s what bothered me. Sherry grew up in the foster-care system, never knew her family. Maybe that’s where the hunger came from.”

“What hunger?”

“Down deep, Sherry was... a drama queen, I suppose. She came alive in the spotlight. She was desperate to be the center of attention. All the time. Wanted to be recognized, wanted people to know her name. And I realized the things she cared the most about meant nothing at all to me. And the things I care about, my family, living in the north, weren’t important to her. I could make her smile, we had some great times, but I could never make her sparkle the way she did in front of a camera.”

“So you ended it?”

“Not then. Things... wound down on their own. Most love affairs have chemistry in the beginning, but unless there’s more to it, an affair’s all it will ever be. That’s all it was for us. A month after Mardi Gras, we were over. No Famous Final Scene, no tears, no hard feelings. I went on the Detroit force after the service and we lost touch for a while, but when I transferred up here, we hooked up again. Went out a few times.”

“Rekindling the old flame?”

“More like auld lang syne. We were over and we both knew it.”

She looked down the ravine. A wrecker was winching the sedan out of the water. “You said you saw her last week?”

“She called me. We met for coffee.”

“Why?”

“Just to say hi, touch base.”

She glanced at me sharply. “You said this was a double homicide. I’m assuming she was pregnant?”

“We talked about that,” I admitted.

“Was it yours?”

“No. No chance.”

“Whose then?”

“I don’t know.”

“Did she know?”

“She didn’t say.”

“Did she sleep around?”

“She was twenty-six and single. She wasn’t a nun. Beyond that, you’re asking the wrong guy.”

“Who should I be asking?”

I mulled that one over. “She said she was seeing Rob Gilchrist.”

“I’ve already heard that. Anyone else?”

This time I didn’t answer. Zee knew I was holding out, but she let me off the hook. For now.

“Do you have any idea what Sherry was doing out here, Dylan?”

“Meeting a source? Meeting a lover? Your guess is as good as mine.”

Which wasn’t quite true. If she’d wanted to have it out with her married boss, Jack Milano, this might be exactly the place. He couldn’t risk signing in the gate of her condo or being spotted out on the town. Their involvement would be a firing offense.

Sherry’d asked me to check Milano out, and I’d taken my sweet time about it. If I’d been faster, she might not be in a body bag, headed for Grayling. I’d been too slow. But I was definitely revved up now.

Zee was staring at me.

“What?” I asked.

“Is there anything else you want to tell me, Dylan?”

“Not a thing.” I was lying to her face now. She knew it. And didn’t like it.

“You’d better go home, LaCrosse. If Kaz finds you hanging around here, we’re gonna have trouble.”

“I’ve already got trouble,” I said.

Even by North Shore standards, Jack Milano’s lake-front home was a mansion. A Beaux-Arts brick estate with tall, ornately framed windows and multiple mansard roofs, it was isolated on its own personal peninsula. Definitely pricey. I guessed five mil, maybe more. Definitely more than a station manager could afford.

I checked my watch as I trotted up to the front door. It was nearly eight. Zee would be stuck at the crime scene at least another hour. With luck, I could ambush Milano before he left for work.

I pressed the buzzer.

No answer.

I was angry enough to kick the damned door in. I leaned on the buzzer, holding it down.

An overhead speaker crackled to life. “Who is it?” A woman’s voice.

“Police, ma’am. Sergeant LaCrosse. Is Mr. Milano in?”

A pause. “Wait, please. I’ll be right down.”

She opened the door a moment later. A tall, spare woman in an azure dressing gown. Silk, I think. She was fortyish, ash blond and elegant. And a bit myopic. She peered at me through thick glasses in designer frames. Ordinarily I would have been in a sport coat and dress shirt over jeans. North-country business chic. My black leather jacket suited my mood.

“Did you say police?” she asked.

“Sergeant LaCrosse, ma’am. North Shore Major Crimes.” I held up my ID folder.

“My husband is in New York, at a conference,” she said, squinting at my badge. “Perhaps I can help. This is about Miss Sinclair, isn’t it?”

I stared at her.

“We have constant Internet contact with the station,” she said, standing aside, waving me in. “Her death is headline news. I’m having coffee, Sergeant... LaCrosse, is it? Join me.”

She wheeled and stalked off toward the breakfast bar without waiting for an answer. She was used to being obeyed.

I followed her through the expansive living room, gleaming hardwood floors, overstuffed leather furnishings. Five wide-screen TV monitors were stacked in the living room, running live video feeds from the station. One had a schedule breakdown, a second the current programs on air. The rest showed breaking stories from the other networks. Sherry’s face stared out at me from two of them, her smile frozen in place. I looked away.

The kitchen was worthy of a five-star chef, burnished copper pots suspended over black granite countertops wide enough to land a plane on. I doubted Mrs. Milano had ever cooked in her life. The coffee maker was a PrimaDonna 6600. Top of the line. It hissed as she poured two cups. The aroma was exquisite.

“You said your husband is in New York?” I asked, taking a stool at the breakfast counter that divided the kitchen from the dining room. “When did he leave?”

“Jack’s been in the city all week.” She took the seat facing me across the bar and slid my cup over. “A conference at corporate headquarters. Meetings all day, every day.”

“Do you have a number for him there? We really do need to talk to him.”

“It won’t do you any good,” she said, eyeing me across the brim of her coffee cup. “My husband fields questions for a living, Sergeant, and I doubt he’ll be cooperative. You won’t get anything useful from him. Perhaps I can be of more help.”

“How so?”

“Jack will lie, trying to conceal his affair with Miss Sinclair,” she said bluntly. “I won’t.”

Surprised, I leaned back in my chair, scanning her face. It was a good face, fine bones, wide-set eyes. She met my stare straight on.

“So... you knew that Miss Sinclair and your husband were involved?”

“It’s not the first time this situation has come up. Jack’s an alpha male, an ambitious and attractive man. That’s why I married him. But — what was that phrase Hilary Clinton used? He’s always been a hard dog to keep on the porch? That’s why I insisted on an ironclad pre-nup before we married. My family has substantial assets. Jack has always worked for wages. It limits his options.”

“I’m not sure I’m following you, Mrs. Milano.”

“Call me Tess, please. We are discussing dark family secrets. My point is, that Jack’s affair with Miss Sinclair isn’t a secret, Sergeant, not from me, anyway. I met with Sherry last week. Frankly, I thought she might be trying to steal my husband. I intended to warn her off. To have her fired, if necessary.”

“How did it go?”

“We came to a meeting of the minds,” Tess Milano said drily. “Sherry was a very ambitious young woman. She said she had a job offer from a bigger station downstate and that it might be best for all concerned if she simply moved on.”

“And that was it?”

“Not quite. She did mention that moving is terribly expensive nowadays.”

“So instead of scaring her off, you wound up paying her off?”

“It was the simplest solution.”

“Did you tell your husband about it?”

“Of course. Jack was furious, at first. He probably had visions of eloping with his latest lady-friend, he often does. But eventually he faces the reality of living on half his salary in a shrinking job market, and comes to his senses.”

“And comes back to you?”

“He never actually leaves.” She sighed. “Girls like Sherry are a recurring fantasy, like running away to join the circus. I know my husband, Detective, and this may sound odd to you, but in spite of his faults, I love him dearly. In some ways, he’s like the child we never had. What do they call that syndrome? Boys who never grow up?”

“Peter Pan,” I said.

“That’s Jack, my eternal teenager. I’m sorry about what happened to Miss Sinclair, Detective, but my husband was not involved, nor was I. If you could keep our problems out of the press, I would be very grateful.”

The stress on very raised my eyebrows.

“A scandal could cost Jack his job and his work is terribly important to him. If any expenses come up, I’ll be happy to cover them.”

“I’ll see what I can do, Mrs. Milano. If I run into any expenses, I’ll let you know. Thanks for your time.”

She walked me to the door. I half expected her to slip me a tenner, like a bellhop.

Under ordinary circumstances, I would have been annoyed at being offered a payoff. Not this time. If she hadn’t offered, I would have asked.

I wanted that particular door left open. If it turned out that I wanted to meet her husband in some secluded spot, collecting a bribe would be a useful excuse.

But I didn’t think I’d need it. Lying is a social skill that requires practice. Tess Milano was a handsome woman born to a family with money. She was used to giving orders and seeing people jump. She probably didn’t lie often enough to get good at it.

She’d told me her story straight out, no signs of evasion. Didn’t echo questions, look away, or stammer. Her hands were rock steady. I was fairly sure she’d told me the truth.

Or what she believed the truth to be.

Sherry wasn’t a problem for the Milanos because Tess bought her off. Would Sherry have taken the money? In a heartbeat.

A quick check of her bank account would confirm the story, but I didn’t doubt it much. Milano wasn’t the man Sherry wanted in her life, and if she could cash out while getting rid of him, all the better.

Not the Milanos, then.

As I walked out, Sherry’s face was on all three screens. And it occurred to me that for the first time, she was exactly where she’d always wanted to be. Right in the middle of things.

But not like this. Not like this.

If Milano was out of the picture, that moved Rob Gilchrist directly into my sights. A trickier business. I’d been able to beat Zina to the Milanos because I had inside information and Milano wasn’t an obvious suspect. But as Sherry’s current boyfriend, Rob would be at the top of the suspect list. Approaching him openly could get me suspended, maybe fired, and I didn’t want that. Not yet, anyway.

The problem solved itself. Rob found me first.

I was in my office at Hauser Center when I got a buzz from the corporal on the front desk.

“Sergeant LaCrosse? You’ve got a visitor, says he’s an old friend. A Mr. Gilchrist?”

“Rob Gilchrist? Send him up.”

Calling us friends was a little strong. Robbie Gilchrist was a local legend. Two years ahead of me in Valhalla High School, he was a basketball star, a deadeye shooting guard. I played hockey. Our sports shared the same season, so we passed in the locker room and hit some of the same parties. We weren’t pals, but I knew who he was.

Everybody knew who Rob was. The Gilchrists are old Valhalla lumber money. They arrived with the timber trains that harvested the virgin forest like a field of wheat.

My people, the Metis, showed up around the same time, fleeing a failed rebellion against the Canadian government. In Canada, we’d been woodsmen, trappers, and traders. Voyageurs.

In Michigan, we became loggers, axe men, saw men, top men. The LaCrosses and our kin did the grueling, dangerous work that made the Gilchrists rich. When the timber was gone, the Metis stayed on, doing whatever work came to hand.

Merchants, mechanics, carpenters.

Cops.

I hadn’t seen Robbie in a few years. Tall and blond, he was a golden boy, blessed with looks and the money to dress well. He didn’t flaunt it, though. He was wearing a lambskin sport coat over a blue chambray shirt, fashionably faded jeans, no tie. North-country high fashion.

In school, he’d been a party animal, but it hadn’t marked him much. Only his eyes had changed. They were wary now. Haunted. Maybe by Sherry’s death. Maybe something else.

“Dylan,” he said curtly. We shook hands and he dropped into the chair facing my desk.

“I’ve got a huge problem,” he said. “Can we talk off the record?”

“That depends. Are we talking about Sherry?”

He nodded. “I could use some help.”

“What kind of help?” I kept my tone casual. “Did you have anything to do with that?”

“No. Hell no!” He stiffened in his chair. “Sherry was a great kid. One of the best friends I’ve ever had.”

“More than a friend, I think.”

“No,” he said, meeting my eyes dead-on. “That’s my problem. We weren’t.”

“I’m not following you, Rob.”

He took a deep breath. “How much do you know about my family, Dylan?”

“The basics, I guess. Old money. One way or another, a third of the county probably works for you.”

“Not for me, pal. Not even for my father. My grandfather Asa totally controls the finances. Eighty years old and bedridden, the old bastard won’t let go.”

He waited for a comment. I didn’t make one.

“The thing is, the old man’s got this... obsession about our family tree, Dylan. He wants to live forever. He thinks a part of him will continue on after he’s gone. Through us.”

“Maybe he’s right. So what?”

“He’s been pushing me hard to get married, have a family of my own. Not my two sisters, mind you, just me. I’m the one with the name. He liked Sherry a lot. Used to watch her do the TV news every night. She’s pretty, she’s smart. He thought we were a perfect match.”

“But you didn’t?”

Rob took a deep breath, then faced me squarely. “The truth is, if I wanted a mate, you’d be closer to my type than Sherry was.”

I didn’t say anything. Just stared. “But you always dated girls. Stone foxes...” I broke off. Getting it. “My God. Sherry was a front for you, wasn’t she? They all were.”

“She was the best of them,” he admitted. “When we were together, everybody focused on her. Thought I was the luckiest guy in the world. We had an arrangement. I paid for her apartment, plus some pocket money. My grandfather thought I was keeping her.”

“I guess you were.”

“But it was strictly business,” he said, leaning forward intently. “It kept the old man pacified, kept my inheritance intact, saved Sherry the rent. Win, win, all around.”

“Why all the drama, Rob? Nobody hides in the closet anymore.”

“You think because the army takes gays now, everything’s so different?”

“The army always had gays.”

“Not my grandfather’s army. We can march down main street in Frisco or New York, but in wood-smoke country? You grew up here, Dylan. Ten miles inshore, it might as well be nineteen twelve. Or maybe eighteen twelve. You know it’s true.”

“In some ways it is,” I conceded. “Did you know Sherry was pregnant?”

“She told me. And before you ask, the answer is no. There was no chance I was the father.”

“How did that affect your arrangement?”

“Actually, I thought it might make things even better. We talked about getting married. I mean, why not? Our arrangement could stay basically the same, my grandfather would come across with my inheritance and die happy. A quiet divorce later on. Sherry and the kid would be set for life.”

“What did she say?”

“She said there were limits to her hypocrisy, but she didn’t rule it out. Women in my family don’t work, and Sherry loved her job. That was a problem, and it wasn’t the only one. When I told my grandfather about the kid, I thought he’d be over the moon. He was. But since we weren’t married...”

“He wanted her to get tested,” I finished.

Rob nodded. “He insisted. I thought there might be a way to fake the test. Sherry said she’d look into it and that’s where we left it. Until this morning.”

I was staring at him.

“What?” he asked.

“You’ve told me a lot more than you had to, Rob. You could have backed off, taken cover behind your lawyers. Why didn’t you? What do you want from me?”

“I need your help, Dylan,” he said, leaning in. “I know I’m going to be a suspect. The boyfriend always is. I need you to know I had no wish at all to harm Sherry, nor any reason to.”

“You want me to control the investigation, to make sure your private life stays... private.”

“I understand I’m asking for special treatment,” he said carefully. “I don’t expect anything for free. Give me a number.”

“Wow. Everybody’s trying to buy me off today,” I said. “It’s a damned shame.”

“What is?”

“If you’re clear of this thing, Rob, I’ll keep your arrangement quiet to protect Sherry. No charge. But if you’re involved in any way at all? It doesn’t matter how much money you’ve got. It won’t be enough.”

After Rob Gilchrist left, I sat at my desk, staring at the wall. Not seeing it. Not seeing anything, really.

I’ve probably worked a hundred homicides. I lost count in Detroit. For the most part, murder is about love, money, or drugs. Domestic abusers blow up, a drug deal goes bad. Violence can cook for years or explode in an instant. But none of the usual elements seemed to apply here.

Sherry asked me to check out the men in her life, so I assumed one or the other might be involved. But Milano had a solid alibi and Rob had every reason in the world to want her alive and well.

According to him.

Could Sherry have been blackmailing him about their setup? Not a chance. If he’d killed her to keep the secret, why would he tell me about it?

No matter how I worked the facts, I couldn’t make ’em compute. Rob was telling the truth. He hadn’t done this. Maybe I’d been working the wrong track. Maybe Sherry’s death had nothing to do with her love life at all.

What did that leave? A story she was working on? I had a huge roadblock there. Zee would already be working that angle. She’d have access to any hate mail or threats Sherry had received. Trying to get access to them through channels could get me suspended. If I went after them directly.

But there might be another way.

I had an inside connection at the station. Not family exactly, but not far from it.

A Metis.

The first Frenchmen, the voyageurs, began arriving in the lake country around 1540. They came for the fur trade. They mapped the land, built outposts, and then homes. They brought no women with them, but human nature being what it is, a new race of beige babies was soon playing along the lakeshore.

We are the Metis (May-tee). Dark-haired people with natural tans and hybrid genes. Born survivors.

Max Gillard isn’t a relative, but he’s Metis. He served in Kuwait with my Uncle Armand and they’re still poker buddies. In the north, that’s enough of a bond to earn me a favor.

After the war, Max hired on to WNTB-TV as a technician. He’s a head cameraman and de facto news director now. A busy man.

He agreed to meet me for coffee in the station cafeteria, a brightly lit room with metal chairs, stainless-steel fixtures. We took a table in the corner, away from the other staffers.

Max is my uncle’s age, but the years have been harder on him. He looked hollow-eyed, burned-out.

But still formidable. He’s built like a blacksmith: blunt fingers, a square face, sideburns going silver. He was dressed in a white shirt and tie, but his sleeves were rolled up, revealing powerful wrists.

“We need to keep this short,” Max said, glancing around uneasily. “Milano called the station from New York. Says he’ll have the balls of anybody talks to the police without clearing every word with him.”

“My uncle says you used to run straight into shellfire to get a picture, Max. Don’t tell me you’re afraid of a city-boy suit like Milano?”

I’d hoped to josh him along, but the glare I got was no joke. He eyed me like a stranger.

“You don’t know, do you? About my wife?”

“Margo? What about her?”

He glanced away, taking a breath. “She’s got MS, Dylan. Multiple sclerosis. She’s bedridden most of the time now. The bills are killing me. I’m working double shifts to keep from losing the house.”

“Damn. I’m sorry, Max, I didn’t know. What about your insurance? Doesn’t it—?”

“It covers ninety percent,” he said flatly. “Which sounds terrific until you total up what an overnight stay in the hospital costs these days. So, yeah, I do worry about a puffed-up city boy like Milano. I need my damn job, Dylan. What do you need?”

“Nothing,” I said, rising to go. “I didn’t mean to put you in the middle of—”

“Sit down, damn it,” he growled. “I’m not so spooked I can’t help a buddy’s favorite nephew. You probably want to know about threats? Stuff like that?”

“Did she get any?”

“By the bale. Every station gets a steady stream nowadays. Any twit with a laptop can flame us, fire off an e-mail that would bring down the FBI if they were on paper. The problem is, there’s so much of it, nobody takes it seriously. I’ve already bundled the top twenty from the past few months. I gave ’em to Redfern. Didn’t she tell you?”

I didn’t say anything.

Max cocked his head, eyeing me. “I wondered if Chief Kazmarek knew about you and Sherry.” He nodded. “You’re not assigned to this case, are you?”

“I’m working it off the books.”

“I’ve covered stories with Redfern a few times,” he said. “She seemed plenty sharp to me.”

“Zina’s a good cop, and she’s thorough,” I said. “She’ll track down every name you gave her. But you’re a local, Max. You know which threats were from flakes and which were serious. I want the short list. Who should I be looking at?”

Max looked away, chewing on the corner of his lip.

“I can’t do this, Dylan,” he said, glancing around, making sure he wouldn’t be overheard. “If Milano finds out about it, he’ll have my ass.”

“Got it. No problem,” I said, rising again. “It was good to see you, Max. I’m sorry about your trouble.”

“It’s a sorry situation all around,” he said. Jotting a quick note on his napkin, he slid it across the table to me. I palmed it without reading it.

“No comment means no comment,” he called after me, making sure the other staffers in the snack bar heard him. “Next time bring a damn warrant. Officer.”

I didn’t read the napkin until I was in my car.

Two names were on it. Pudge Macavoy and Emmaline Gauthier.

I knew both names. All too well.

Macavoy was a local bad boy, late twenties now, in trouble since he could walk. I remembered seeing him on TV when Sherry did a piece on domestic abusers. Shirtless, he was standing in the door of his double-wide screaming obscenities at her.

Was Macavoy crazy enough to go after Sherry? Absolutely.

But he hadn’t.

A quick check of the Enforcement Net turned up Pudge’s name. He was already in custody. He’d been busted in Petoskey for his third DUI. Too broke to make bail, he’d been cooling in a cell for the past ten days. He was probably guilty of at least fifty felonies. But not this one.

The Gauthiers were another matter. There was a small army of them, a dozen families related by blood or marriage. They’re wood-smoke folks, a catchall term for blue-collar types who live in isolated cabins and double-wides in the northern interior. Their homes are heated with free wood gleaned from the state forest, and the scent of smoke lingers on their clothes like musk. I’m a wood-smoke boy myself, and not ashamed of it, but it’s not a term you toss around casually. Some newcomers consider it a synonym for white trash. If you call somebody wood-smoke, you’d best smile.

The Gauthier clan has a dozen branches, but one has been top dog since I was a boy. Miss Emmaline, mama to seven boys, grandmother to a roughneck militia. She could give the Mafia lessons in organized crime, backwoods style.

I could have hauled in half of the Gauthier clan on one beef or another, but it would have been a waste of time. Wood-smoke people never talk to the law. Ever. If one of them had a problem with Sherry Sinclair, there was only one person I could ask.

The drive into the back country is a bit like time travel, back to my childhood. The October hills were already dressed in gold and autumn orange, the forest floor carpeted in leaves in a thousand colors, dusted with white snow doilies here and there.

The Gauthier clan owns small holdings scattered around the edge of the state forest, some adjoining, some not. Subsistence farms, for the most part, twenty acres here, forty there. None larger. But total them up and they cover a lot of territory.

A generation ago, they ran truck gardens, poached venison and small game year round, lived off the land as they had for a hundred years.

But times change. The DNR is tougher on out-of-season hunting now, and you can make a lot more money growing reefer than raising vegetables.

Emmaline’s farm rests atop a long rise, with a magnificent view of the rolling, forested hills with a silvery sliver of the big lake glinting on the horizon. From her front porch, she can watch the morning sun rise, and then see it set again at the end of the day. She can also see anyone approaching a good half-hour before they pull into her yard.

She watched me come, sitting on her porch in a white-pine rocker hand carved by one of her sons. Or perhaps her great-grandfather. Time is measured differently in the back country.

As I pulled up in front of the house, she was knitting, waiting for me. If she was concerned, she gave no sign. She appeared to be alone, but across the clearing I noticed the hayloft door of her barn was slightly ajar. Someone was watching me from the shadows. Probably had me in the crosshairs. Welcome to wood-smoke country.

I kept my hands in plain sight as I walked up the steps to the broad front porch of her ranch house. The October air was brisk, but the sun was warm on the weathered wood.

It wasn’t a suburban ranch-style home; the rambling clapboard cabin could have been teleported from the Great Plains, along with its owner.

Emmaline Gauthier had one of those old-timey faces you see in tintypes: weathered, hawkish, carved from oak. Ice-blue eyes that looked right through you. Her clothes probably came from Goodwill: faded flowered dress, a threadbare sweater over an apron.

“Good afternoon, Miz Gauthier.” I nodded as I reached the top step, “I’m—”

“Claudette LaCrosse’s boy,” she finished, glancing up from her knitting. “You’d be Dylan, right? How’s your mother?”

“She’s fine, ma’am.”

“Yes, she is. Most folks in town aren’t kind. Store clerks pretend they don’t see me, snotty brats snicker at my clothes. But when I visit your mother’s antiques shop, she offers me coffee. Shows me some of her nice pieces. We chat about the old days. Once in a while I’ll buy some trinket, but not often. We both grew up in the back country, your ma and me. She ain’t wood-smoke no more, but she ain’t forgot her roots. Have you?”

“I’m not here to talk about my ma, Miss Emmaline.”

“Then maybe I should call my lawyer. Sergeant.”

“That’s your right, if you think you need one.”

“Oh, I expect I can handle any trouble you got, sonny. I’d offer you cider, but I doubt you’ll be here that long. What’s this about?”

“Sherry Sinclair,” I said, watching her face.

“That girl from TV?” She frowned. “I heard about what happened to her. As I recall, you two were keeping company awhile back. So are you here on police business? Or on your own hook?”

“Both,” I said.

She glanced up at me, her gray eyes as sharp as lasers. “No, I don’t think so. It’s mostly personal, ain’t it.” It wasn’t a question.

“It doesn’t matter what it is,” I said. “I understand you had some kind of dust-up with Sherry. I need to know about that.”

“We had us a few problems,” she admitted. “The girl ambushed me. I’m comin’ out of WalMart with a cartload of groceries. Sherry runs over and shoves a microphone in my face with a cameraman filmin’ the whole thing like I was on COPS TV. Girl had sand, I’ll give her that.”

“What did she want?”

“Same thing you people always want. She’d heard a lot of ugly rumors and gossip—”

“And checked your clan’s police records,” I put in.

“That too, maybe,” Emmaline conceded with a wry smile. “She said she was planning a story on the wood-smoke outlaws.”

“Starring your family?”

“That was the plan.” She shrugged. “You know my boys, LaCrosse. There’s so many Gauthiers in this county, somebody’s always jammed up over some beef or other. Nephews, cousins, shirttail kin. If you go by the numbers, we can look a little shady. That girl had it in her head that wood-smoke country is the Wild West, and I’m Jesse James.”

“More like Calamity Jane,” I said. “What happened?”

“We made a trade, like in the old days.” Emmaline shook her head, smiling at the memory. “I invited her out here to the house for a visit. No cameras, no mikes, just us. She came, too. Girl wasn’t afraid of nothin’. We had us a talk, nose to nose, worked things out.”

“Worked them out how, exactly?”

“The way it usually works. I bought her off.”

“I don’t believe that.”

“Everybody’s got a price, young LaCrosse, even you, I expect. The key to a good trade is to figure what that price is. Sherry didn’t care much about money. Robbie Gilchrist was keepin’ her and if I had his money, I’d burn mine.”

“Then what was her price?”

“I offered to swap her a better story.”

“What story?”

She hesitated, reading my eyes. “I wonder how far I can trust you, young LaCrosse?”

I wasn’t sure how to answer that, so I didn’t.

“I knew your daddy,” she said, resuming her rocking. “He was a handsome man, but a little thick, I always thought. You favor your mother, I believe. There may be hope for you.” Reaching into the pocket of her print apron, she came out with a cellophaned brick of white powder and tossed it to me.

I caught it and hefted it. It felt like a pound. “Sweet Jesus, lady, what—?”

“That’s half a key of crystal meth,” she said calmly. “Pure glass. Ounce for ounce, it’s worth about the same as gold.”

“It’s also worth twenty years for possession.”

“Then it’s a lucky thing I just handed it over to the law, ain’t it?”

“I don’t understand.”

“I’m making you the same offer I gave your girlfriend, LaCrosse. The state forest is bigger than a lot of countries. Reefer grows wild in the woods, always has. Now and again my boys harvest a few plants, sell a pound or two downstate, like we have for a hundred years.

“But lately we’ve been finding a lot more than reefer out there. They’ve been coming across campers and motor homes stashed in the big timber. They ain’t there on no vacation.”

“Meth labs,” I said.

She nodded. “Crank crews from downstate are moving into our territory. We’ve already had some trouble. The fellas that cooked up that packet you got in your hand took a shot at one of my boys.”

“What happened?”

“I just told you,” she said coolly, “they shot at my boy. What do you think happened? Lucky they were city boys who couldn’t shoot for squat. A bad mistake.”

“How bad?” I asked.

She met my eyes for a moment. Her face showed nothing at all. She didn’t expand. Didn’t have to.

“We found that crystal in their rig after they... departed. But that was just one lab. There’s a half-dozen setups out there, and more on the way unless we do somethin’ about it. It could turn into a shootin’ war. Folks could get killed.”

I suspected they already had, but let it pass.

“You told Sherry about this?” I asked.

“We made a trade. She drops the story about a few wood-smoke boys growin’ weed, goes after the big-city gangs that are cookin’ up poison on state land. She shines a light on ’em, they’ll scatter like the cockroaches they are.”

“Or maybe they break her neck and roll her car down a ravine.”

“I’ve been thinkin’ on that since I heard.” She sighed. “I liked that girl. She was pretty, she had grit. If I thought one of them cookers... But I doubt it was them, Dylan. We hadn’t closed no deal yet. I had the boys make up a map that shows where the labs are now. They move the rigs after every second batch, never stay more than a week or two in one spot. We’ve been keeping tabs on ’em, and they’re all still in place. If they thought they’d been burned—?”

“They’d be in the wind,” I agreed. “I want that map, Emmaline.”

“And I’d dearly love to wake some mornin’ in Brad Pitt’s bunk. We’ll both have to settle for what we can get. I’m offering you the same deal I gave Sherry. The map will aim you straight at them crank labs, but in return, you leave me and mine be for a while. If your people come across a reefer patch in the woods, you blink your eyes and keep right on walkin’. Deal?”

I didn’t say anything.

“It’s the right thing, Dylan. The weed grows wild in the woods. It can soothe your spirit, ease your pain. Meth’s an abomination that rots out your mouth and steals your damned soul. I won’t tolerate it, you understand? You move that scum off my ground, or by God we’ll put ’em under it.”

“Deal,” I said grudgingly. “You give me the map, we’ll cut you some slack. But tell your people to stand down. No more shootouts in the woods. You leave them to the law.”

She spat in her hand, we shook, and that was it. Done deal. No contracts, no lawyers. In wood-smoke country, your word is all that matters. And it damned well better.

“I’m real sorry about that girl, Dylan. Tell her family—”

“She had no family, Miss Emmaline. She was a foster child. Grew up in the system.”

“No family?” she echoed. “Not even...? No people at all?”

Emmaline Gauthier frowned off into the distance, as if searching the hills for answers. Her extended clan was her whole life. I doubt she could even conceive of a world without blood ties.

“My God, Dylan, that’s... godawful sad, ain’t it.”

“Yes, ma’am,” I said. “It is.”

Driving out of the hills, I sorted through what Miss Emmaline had told me. And what she hadn’t.

She’d lied about one thing. Not all of her clan were Robin Hood back-to-nature types, growing weed, living off the land like their forefathers. Two of her punk nephews had been caught on video downstate, buying up pseudoephedrine, a key element in cooking crank. Some of the Gauthiers were involved in the meth trade, and if they were, she knew about it.

Which made the rest of what she said more likely to be true. She’d given me a map of the sites of the meth labs in the state forest, partly because they were operating on land she considered her personal turf.

Partly because they were her competition.

Still, the pound of crank in my pocket proved some of her story was true. Downstate gangs were operating on our ground and with deer season only weeks away, half a million hunters would soon be invading the north. If they stumbled across the crank labs, it could turn into World War Three. A disaster.

Especially for the Gauthiers. The last thing Emmaline wanted was an army of cops in the state forest. The enemy of my enemy is my friend. That made us allies. For now, anyway.

Had she offered the same deal to Sherry? Probably. Emmaline wouldn’t have wanted her family name in the news. Trading up to a bigger story worked for both sides. It’s a deal Sherry would have jumped at. Her ticket to the big time.

But had her eagerness gotten her killed?

Miss Emmaline thought not, because they hadn’t closed their deal. She hadn’t given Sherry the map with the lab coordinates so she wasn’t a danger to anyone yet. I didn’t think so either, but for a different reason. Sherry wouldn’t have gone to that lonely turnout to meet anyone she didn’t know. Certainly not a Gauthier or anyone connected to downstate gangs. Whoever she’d met there was someone she trusted.

My phone buzzed, breaking into my thoughts. I checked the screen. It was a text, from Zee. Sherry’s apartment. We need to talk. Now.

I knew the way.

Sherry’s condo is part of a new, ultramodern complex built on the bones of an old lumber baron’s mansion, a block from Old Town, the original heart of Valhalla. The place felt like a rabbit warren to me, too many people packed into hyper-efficient little boxes. Sherry said she liked hearing her neighbors fighting at night or gargling in the morning. Said it made her feel like she was part of a family.

To me, the place was a glorified motel with yuppie transients for tenants. It would only feel homey to a foster child who couldn’t tell the difference.

The front door was ajar. I eased in, then stopped, frozen by a sudden flood of memories. The faint scent of Sherry’s perfume. The bland, beige IKEA furniture that had come with the place, and would soon pass to someone else. Sherry should have been sitting at the Swedish birch-and-glass desk, scanning her laptop for breaking stories.

But now she was the story. And my partner Zina Redfern was at her desk, riffling through her papers. The laptop was gone, probably being analyzed in the basement lab at Hauser Center.

Zee swiveled in the chair to face me. She wasn’t happy.

“I called the office,” she said. “The desk sergeant said Rob Gilchrist talked to you, then you disappeared. Without saying where.”

“Gilchrist didn’t know anything useful. He’s not the guy.”

“Damn it, that’s not your call, Dylan. You shouldn’t have talked to him at all—”

“You could have chewed me out over the phone and saved me a trip, Zee. What have you got?”

“Officially, the investigation is progressing. Off the record, you’d better take a look at this.” She handed me a thin sheaf of papers.

I glanced through them. Colored bar graphs and percentages. The business heading on the front page was BetaPhase Genetics. “What is this?”

“A DNA test, of sorts,” Zee said, watching my face. “It’s not for paternity. It’s for genealogy.”

“I don’t understand.”

“Sherry apparently learned she was pregnant about ten days ago, and had her doctor administer this test. For paternity, you have to supply DNA from the father. For genealogy, nucleotides from the fetus are enough to do the trick.”

“I still don’t—”

“The test can determine the father’s ethnic heritage without his cooperation,” Zina continued. “It’s obvious what she was looking for. Gilchrist is Nordic. Apparently the other candidate wasn’t. The test results are at the bottom of the page.”

I checked it. It was a ragged bar graph, a mix of northern and southern European. The only bar that stood out was Native American, 24 %.

“That would be you, right?” Zee said.

I stared at the graph, didn’t say anything.

“The baby’s ethnicity was Native American to the twentieth percentile, so the father would be roughly double that. Forty percent, give or take. That means he’s almost certainly Metis, Dylan. You’d better talk to me.”

I still didn’t say anything. I felt like I’d been kicked in the belly.

“Look, this test isn’t definitive,” Zee pressed, “but a paternity test will be. If something happened with you two, you need to get in front of it—”

“Nothing happened.”

It was her turn for silence. “So... this isn’t you?” she said. “Is that what you’re telling me?”

“Did you find anything else?” I asked.

“Sherry had an appointment with her OB/GYN for Thursday.”

“For a checkup?”

“More than that. Her doctor pleaded patient confidentiality, but I bluffed her. Off the record, Sherry was scheduled to terminate her pregnancy. That’s what I’ve got. What have you got?”

I thought about lying to her again but knew I’d make a hash of it. I walked out, instead. So enraged, my whole world seemed to be bleeding red around the edges.

Every cop has a neutral look, a mask we wear on duty. It’s called a cop face. It’s supposed to conceal emotions, from fear to fury. Mine must have slipped as I pulled into Max Gillard’s driveway.

He was raking a few errant leaves from his bedraggled front lawn as I rolled up. His welcoming smile turned cautious as he walked over to greet me. He glanced around to be sure the neighbors weren’t watching — then he pulled an ugly brute of a revolver from the small of his back, aiming it straight at my head.

“Get out of the car, Dylan.” He tossed the rake aside.

“What are you doing, Max?”

“It’s game over and we both know it. Now get out, walk ahead of me into the garage. Don’t do anything sudden. Or stupid.”

He eased the hammer back to full cock to underscore the point. A quick read of his eyes changed my mind about trying to bluff him. The gun muzzle gaped wide as a railroad tunnel.

I marched ahead of him into the garage. He hit a button, the garage door closed, then it was just the two of us in an empty box of a room. A tool bench along one wall, a concrete floor. A dangerous place.

Desperate men often kill themselves in garages, a final courtesy to their families. Easier for the survivors to clean up the mess.

The same would be true for a murder.

I turned to face Max.

He looked red-eyed and haggard, like he hadn’t slept in a month. Needed a shave. He was wearing a U of M T-shirt and faded jeans. Despite the weather, he was barefoot. I didn’t know what to make of that. But the weapon in his fist was rock steady, aimed at center mass. Military style. Any wound would be fatal at this range.

“I’ve covered enough crime scenes to know the drill,” he said, brushing his thinning hair back with his free hand. “I know the head games too, so skip the bushwa. I’m at the end of my rope, Dylan. I’ve got nothing left to lose. Clear?”

I nodded.

“Tell me what you know.”

“I know you killed Sherry, Max. I didn’t until I drove up, but I do now. I don’t know why.”

“It was a mistake. A bad one all around.”

“She was pregnant. It was your child, wasn’t it?”

“Another mistake,” he said grimly. “We weren’t really involved.”

“Apparently you were.”

“Not the way you think. We were on an out-of-town assignment, closed up the hotel bar, both of us pretty hammered. Maybe she felt sorry for me, I don’t know. It was all wrong, but I was so desperate...”

He waited for a comment. I didn’t say anything.

“It was never about sex with her, anyway,” he said. “It was just another way to be the center of attention. Even for a few hours on the road with a has-been cameraman. It didn’t mean a thing.”

“Until she turned up pregnant.”

“She called me at home, late. Asked me to meet her at the turnout. All very hush-hush and melodramatic.”

“She was being careful, Max, protecting you. If Milano found out, he’d can you in a New York second.”

“She shouldn’t have told me at all! I wouldn’t have known. It was all just a soap opera to her.”

“Maybe she thought you deserved to know.”

“To know what? That with my whole life falling apart, one small miracle happens and she was going to brush it off like a breadcrumb?”

“What did you expect her to do, Max? In her situation—”

“What about my situation! My wife is dying, I’m a quarter mil in the hole for medical bills, we’re losing the house—”

He looked away, swallowing hard, his jaw working. But the gun never wavered. He was on a tightrope, stretched taut across the abyss, only a word away from killing me. Or himself.

Or both of us.

“Just tell me what happened, Max. I need to know.”

“She said she was getting rid of it,” he said, looking away a moment. “She didn’t ask what I thought, or what I wanted to do. Everything is falling apart and — I snapped, I guess. Lashed out. I’ve never laid hands on a woman in my life.”

“You didn’t lay hands on her, Max,” I said, straining to keep my voice even. “You smashed her larynx with a kill strike.”

“Reflex from the army. A heartbeat later I would have cut my arm off to take it back. But I couldn’t. I can’t. There’s no going back now.”

“Or for me, Max. People know I’m here.”

“Actually, I’m counting on that,” he said, his eyes locking on mine.

“There’s no way out for me, I get that. But I can’t just quit, either. None of this is Margo’s fault, but if I go to jail, she’ll lose everything. She’ll die in some charity ward.”

I swallowed a surge of bile in the back of my throat. I knew where this was going. It was in his eyes.

“Somebody has to pay the tab for Sherry,” he continued. “That’s on me. But somebody has to see to Margo too. And I only know one way to do that.”

“To hell with you, Max! I won’t help you. It won’t work anyway.”

“Then we’ll both die for nothin’. I’ve already made my choice, Dylan. I thought it would be hard but it’s almost a relief. I’m already in the wind, almost gone. If I have to take you with me, I will.”

He fired a round. Point blank. The bullet ripped past my ear like a thunderbolt! I flinched, but managed to stand my ground. Max’s eyes were glittering with battle madness. He fired again! And then once more! Punching a hole through the wall, exploding a window behind me. And somehow I stood there. Didn’t move.

That’s three, I thought. He doesn’t want to kill me and he only has three rounds left—

But he was way ahead of me. Flipping the revolver’s cylinder open, he spun it hard and snapped it closed. Then he aimed straight at my head and pulled the trigger.

Click! The hammer fell on an empty chamber. My knees turned to water.

“Damn it, Dylan, you’ve the devil’s own luck!” he cackled. “Your odds—”

Pure reflex: I drew my weapon and fired two shots, a double tap to the torso, dead center. The impact sent Max stumbling backward into the tool bench, then he dropped to his knees.

I was so enraged I almost fired again. Probably should have. His gun was still in his fist. But he didn’t seem aware of it anymore.

Blood was bubbling from his mouth. He thrust his face upward, keening for a few final breaths. His eyes met mine and I could read his desperation.

Kneeling beside him, I took the gun out of his hand, grasping his shoulder to keep him from falling. He sighed, and I realized his eyes had lost focus, as though he were staring off into some immeasurable distance. Perhaps he was.

In the space of a single breath, he was gone.

I eased him gently to the concrete floor. A part of me hoped he choked all the way to hell. But he’d been a brave man once, a man who ran into shellfire to get a picture. With his world crashing around him, he’d lashed out in a moment of fury. And in that split second...?

God.

Whatever mistakes Sherry and Max had made, they’d paid a terrible price for them. And the worst of it was, it was for nothing.

Sherry died trying to save the career she wanted so desperately, and Max died trying to provide money for his wife’s care. It wouldn’t happen.

The syndrome is called suicide by cop. A desperate man provokes a shootout with police, hoping to go out in a blaze of glory. But insurance companies recognize it for what it is. And they don’t pay off for suicide. Period.

Max’s wife wouldn’t see a nickel. And Sherry would be dismissed as another ditzy blonde with a messy love life. Unless...

I rose slowly to my feet, looking around me, evaluating the garage as a crime scene. I could hear sirens in the distance. Valhalla isn’t Detroit. Gunfire in a quiet neighborhood triggers 911 calls. I had a few moments, not much more.

A minute later the first prowl car came howling down the street with lights and sirens. It screeched to a halt in the driveway. Two Valhalla patrolmen came boiling out with weapons drawn. I knew them both, but I stepped out of the garage very slowly anyway. Holding my badge in plain view, I placed my weapon on the ground. And then things started happening very quickly.

The shooting occurred inside Valhalla’s city limits, but with a local officer involved, the state police took over jurisdiction. I spent the rest of the day in a Hauser Center interrogation room with a tag team of detectives from downstate, Bendix and Coughlin.

I knew Dan Bendix from the winter hockey leagues. He played forward, liked to body check along the boards. Big and burly, with scars on his knuckles, he’s a genuinely tough guy. His questions were sharp, but fair. He had nothing to prove.

Coughlin was the opposite. A runty Irishman from Lansing, he had freckles, red hair, and an attitude to match. He’d gotten his gold shield a few months earlier and felt compelled to play bad cop. He tried too hard, shouting questions at me like I was some mutt off the street, sneering at my answers. He called me a liar. Twice. I let it pass.

He was right, actually. But his punk-ass attitude made lying to his face a lot easier.

I hated Max for what he had done, but none of it was his wife’s fault. He threw his life away to get the money for Margo’s care, and I made certain that she got it.

To do that, I had to eliminate any suspicion that his death had been a “suicide by cop.” And I did. By making him the villain of the piece.

With a vengeance.

A good man driven to crime is an old, familiar story, from Robin Hood to Breaking Bad. It wasn’t hard to sell.

Desperate for money, Max had gone into the drug trade. The brick of crystal meth the Staties found hidden in his garage was the proof. Working on a story about meth labs, Sherry discovered his involvement. She confronted him at the turnout, hoping he would give himself up.

Instead, he killed her. He admitted it all to me before dying in a desperate shootout. Resisting arrest isn’t suicide. If the two Staties had any doubts, they vanished when I showed them the map of the meth labs I’d recovered from Max’s body.

The story was a total crock, but it was plausible, and seamless. And they bought it.

The raids on the crank labs began at dawn the next day and continued through the week. The state police and DEA rolled up eight labs and a dozen cookers. It made national news. Which was the second point of the exercise.

Helping Margo collect the insurance money her man had died for wasn’t the only reason I sold the state police a bill of goods. It was my last chance to give Sherry what she’d always needed so desperately. More than anything in this world, she’d wanted to be a star.

By God, she went out as one.

My version of events conveniently omitted her complicated love life. Instead, Sherry died as a courageous newswoman hot on the trail of a big story.

I think Zee knew better, but by the time she wrapped up her own investigation, the raids were already underway and my fairy tale had gone viral in the media. On the Net, facts never get in the way of a good story.

Desperate for a heroine after the recent scandals, the national press turned Sherry into an instant icon. Overnight, her dream came true. Everyone knew her name. She was the center of attention.

It won’t last, of course. Andy Warhol set fame’s expiration date at fifteen minutes, and most of us never achieve that.

But Sherry got her share and then some. Her funeral was a media circus. Talking heads from the major networks and most of the minors covered it live from the cemetery, wearing somber faces and black armbands.

It was a spectacular, star-spangled sendoff. I only wish she could have seen it.

And maybe she did.

I’m not religious. The afterlife is a mystery to me. But I knew Sherry down to the bone. Knew her drive and her desperation.

No power in this world or the next could have kept her away from that show. In my heart, I know she saw that turnout, and warmed herself in the spotlight one last time.

And if you could ask her if it was worth it?

I know exactly what she’d say.

Copyright © 2012 by Doug Allyn

Gymnopédie No. 1

by Susan Lanigan

The short fiction of Irish author Susan Lanigan has appeared in a variety of publications, including The Stinging Fly, Southword, The Sunday Tribune, the Irish Independent, and The Mayo News. She has been shortlisted twice for the Hennessy New Irish Writing Award and has won several other awards. Nature magazine’s science-fiction section recently acquired two of her stories and her work is featured in the science-fiction anthology Music For Another World.

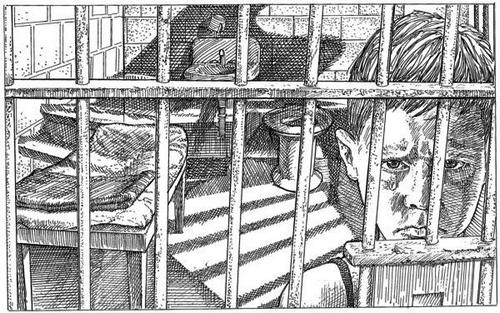

Once again, the sunset. To be precise, the bit I am allowed to see: parallel gold diagonals streaking across the edge of my bunk and hitting the door, while the sink and privy stay in the dark and the mirror reflects nothing. I prefer the shadow. Since they moved me here five years ago, a kindly promotion from the cell that faced the prison’s north wall, I have seen too many sunsets, each one leading back to the same memory: my mother, long dead now, playing the piano.

She always became more girlish when she played; even then I noticed the shy hesitant smile when she made the odd mistake. I was five then, standing in the doorway of the study in a manner, Dearbhla told me afterwards, of a child self-consciously trying to be “cute.” I have no idea whether Dearbhla told me this out of malice — whether she already detected a resentment I could find no words to express — or because she was genuinely amused. Anyway, she was not there to witness it firsthand. By the time she was there on a regular basis, my mother and her orange kaftans and hair tied back with a grubby chenille ribbon had gone, gone forever.

My mother had few pieces in her repertoire but since I, at the age of five, was her primary listener, it should not have mattered too much. Yet I recall, in flashes, how her head would jerk upwards when my father pushed the creaking gate of our little garden open. The look of strained hope that crossed her face as she pushed the open window full out and started a few bars of the same piece. She started in medias res, I believe, to fool my father into thinking that she had been playing on for hours, unaware of his presence, in some sort of creative trance. I don’t believe he fell for it. He would come to the door and wink at me as she fingered the keys like alien objects, her eyes self-consciously shut.

It was always the same piece, Satie’s Gymnopédie No. 1, and she was never able to get all the way through without making a mistake. To me now, that seems absurd; unlike Dearbhla, I never had a great talent for music, but even I could pick my way through something of that level with no great difficulty. But my mother’s mistakes were always so small — a missed note when it unexpectedly changed to F minor on the second repetition, an E instead of a D in the bass — that somehow I could always hear the soft chords transcending the little awkwardnesses. I remember (this must have been earlier, I must have been even younger then) hearing the muffled ripple of bass and right-hand chords through the timber of the shivering piano as I curled myself into a ball at my mother’s feet. I nearly fell asleep with my cheek touching the cold bronze of the una corda pedal, spittle drooling down my cheek. The evening sun was coming through the two-paned window, shafts of it warming the wood, and warming my mother’s orange kaftan and warming the pale brown carpet where I lay my head. The soft pedal remained cold, unmoving. I don’t know how long I lay there until I was picked up and brought to bed. It seemed like infinity, but then again this happened long ago, before I learned to measure time, each begrudging second, hour, and year of it.

She never quite got it right. Each rendition was a diamond with a different flaw. I didn’t mind. Like an idiot savant, I craved routine. The routine of sun falling on my mother and the Gymnopédie, the routine of drizzle soaking the unmown grass in our front garden and the Gymnopédie, the dying elm shedding its last leaves as the Dutch beetle gnawed away at it from the inside — and the Gymnopédie—

“I’ll get it,” my mother would call out, “I will, you’ll see.” Then she would fling her head back and laugh, and the light would catch the fine hairs on her neck, her neck that was able to arch so elegantly and make my father catch his breath. Dearbhla says I don’t remember properly, after all I was very young and children idealise things a lot, don’t they? But then again, rare things are easy to recall by virtue of their rareness — and happy memories of my childhood are rare indeed.

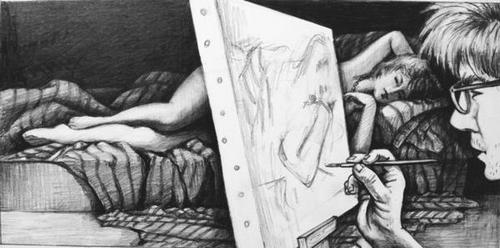

I don’t know why Dearbhla still visits me, week in, week out. I should be the last person she wants to see. She is a joy to look at through the Perspex panel: those tapering, gloved fingers are still beautiful, their clasp of the thin, unlit cigarette irreproachably filmic. They will never touch a piano again. But even in late middle age she retains the proud cheeks and prominent eyes that captivated her audience as much as the pieces she performed for them. The last time she came, she brought a letter in a vellum envelope. Typed, of course; she can hardly write by hand now. I haven’t read it yet. I want to hold off as long as possible to make the anticipation all the keener. Prison has taught me discipline, the ability to ration pleasure. She arrives again tomorrow: I will have read it by then.

She has forgiven me much, Dearbhla, or perhaps she visits me out of need: I am the only surviving witness of the great tragedy of her life. As long as she blames me, she is safe. She can duck responsibility for her one failure.

Perhaps she is correct. Perhaps it is my fault.

When Dearbhla first came to the house, the laughter was different. It was laughter that sounded as if it were trapped in a bad sitcom and never let out. It banged crossly against the china my mother brought out for her visitor and rat-tatted irritably against the walls.

Dearbhla sat on the edge of one of our armchairs, her eyes eager, hands holding her cup in a way that spoke pure elegance. My mother, her face white and strained, her hair still pulled back in the grubby ribbon, had lost her look of girlishness. Her belly rounded out a little and her neck no longer arched the way it used to. When my father propelled me forward to Dearbhla and boomed at me to say hello, I was crushed in silk and perfume and Dearbhla’s slightly harsh voice breathed affectionately in my ear, “Well, there’s the darling.”

Her presence unsettled me. It was as if something alien, wondrous, and scary had come into our little cottage, enveloping it with an aura I had never experienced before. When I had lain under my mother’s feet back then, I had felt such security, but in Dearbhla’s arms I sensed danger and excitement. Her embrace was too cloying and yet delightfully warm, her fingers wrapped around me and dug in like claws. I looked over to my mother’s fingers, which were lacing and unlacing each other in tension. I saw how short and spatulate they were. Fingers that would get lost playing the difficult octave spans that Dearbhla was to show me, though I could not know that at the time.

It was my father who first suggested that Dearbhla play something. She smiled, but looked uncomfortable at the suggestion. “Oh David. Should I, really?” I could tell from the tautness of her body, still holding mine, that she longed for it, but did not dare say yes. Not openly. Not yet.

But my father, his voice queer and rough, said, “Yes. Play. Play!” His command was heavy with a weird ache.

“Well,” Dearbhla said. “If you insist.”

My mother’s eyes widened. The pupils in them had shrunk into tiny black dots and they were all iris. She stood up in a jerky, unlovely movement, walked over to Dearbhla’s chair, and pulled me out of her arms. I squeaked with alarm.

“Oh, I’m sorry,” Dearbhla said good-humouredly, getting out of the chair.

I could tell my father was about to say something to my mother, but then Dearbhla sat down at the stool, her fingers running lightly over the keys without pressing them. I shuddered as they did so, imagining them clinging hard to me, even though her touch on the keyboard was delicate. I looked over at my father. His eyes were closed, lips parted open. Now it was he who looked as if he were in a trance.

“What shall I play?” Dearbhla asked gaily.

“Anything,” my father whispered.

I did not look at my mother.

After what seemed like an age, Dearbhla hit two black keys and then let loose. I was later to learn that the piece was a Fantasie-Impromptu in C sharp minor by Chopin, but at the time it was just a roaring tumble of notes, all pouring out sweetly and asynchronously into the air. The energy in the room changed as she played. Her eyes glazed over as left and right hand concentrated on maintaining the difficult cross signatures the composer demanded.