В книгу вошел упрощенный и сокращенный текст одного из самых известных романов американского писателя М. Рида «Всадник без головы». Помимо текста произведения книга содержит комментарии, упражнения на проверку понимания прочитанного, а также словарь, облегчающий чтение.

Предназначается для продолжающих изучать английский язык (уровень 3 – Intermediate).

Майн Рид. Всадник без головы / Mayne Reid. The Headless Horseman

Адаптация текста, составление упражнений, комментариев и словаря И. С. Маевской

© Маевская И. С., адаптация текста, упражнения, комментарии, словарь

© ООО «Издательство АСТ»

Chapter One

On the great plain of Texas, about a hundred miles southward from the old Spanish town of San Antonio de Bejar, the noonday sun is shedding his beams from a sky of cerulean brightness. Under the golden light appears a group of objects.

The objects in question are easily identified – even at a great distance. They are waggons. Slowly crawling across the savannah, it could scarce be told that they are in motion.

There’re ten large waggons, each hauled by eight mules; their contents are: plenteous provisions, articles of costly furniture, live stock in the shape of coloured women and children; the groups of black and yellow bondsmen, walking alongside; the light travelling carriage in the lead, drawn by a span of Kentucky mules, and driven by a black Jehu.

The train[1] is the property of a planter who has landed at Indianola, on the Gulf of Matagorda; and is now travelling overland.

In the cortège that accompanies it, riding at its head, is the planter himself – Woodley Poindexter – a tall thin man of fifty, with a slightly sallowish complexion, and aspect proudly severe. He is simply though not inexpensively dressed. His features are shaded by a broad-brimmed hat.

Two horsemen are riding alongside – one on his right, the other on the left – a stripling scarce twenty, and a young man six or seven years older. The former is his son – a youth, whose open cheerful countenance contrasts, not only with the severe aspect of his father, but with the somewhat sinister features on the other side, and which belong to his cousin.

There is another horseman riding near. The keel-coloured “cowhide” clutched in his right hand, and flirted with such evident skill, proclaim him the overseer.

The travelling carriage, which is a “carriole”,[2] has two occupants. One is a young lady of the whitest skin; the other a girl of the blackest. The former is the daughter of Woodley Poindexter – his only daughter. The latter is the young lady’s handmaid.

The emigrating party is from the “coast” of the Mississippi – from Louisiana. The planter is not himself a native of this State. Woodley Poindexter is a grand sugar planter of the South; one of the highest of his class.

The sun is almost in the zenith. Slowly the train moves on. There is no regular road. The route is indicated by the wheel-marks of some vehicles that have passed before – barely conspicuous, by having crushed the culms of the shot grass.

Notwithstanding the slow progress, the teams are doing their best. The planter hopes to reach the end of his journey before night: hence the march continued through the mid-day heat.

Unexpectedly the drivers are directed to pull up, by a sign from the overseer; who has been riding a hundred yards in the advance, and who is seen to make a sudden stop – as if some obstruction had presented itself.

“What is it, Mr Sansom?” asked the planter, as the man rode up.

“The grass is burnt. The prairie’s been afire.”

“Been on fire! Is it on fire now?” hurriedly inquired the owner of the waggons. “Where? I see no smoke!”

“No, sir – no,” stammered the overseer, becoming conscious that he had caused unnecessary alarm; “I didn’t say it is afire now: only that it has been, and the whole ground is as black as the ten of spades.”[3]

“What of that? I suppose we can travel over a black prairie, as safely as a green one? What nonsense of you, Josh Sansom, to raise such a row about nothing!”

“But, Captain Calhoun,” protested the overseer, in response to the gentleman who had reproached him; “how are we to find the way?”

“Find the way! What are you talking about? We haven’t lost it – have we?”

“I’m afraid we have, though. The wheel-tracks are no longer to be seen. They’re burnt out, along with the grass.”

“What matters that? I reckon we can cross a piece of scorched prairie, without wheel-marks to guide us? We’ll find them again on the other side. Whip up, niggers!” shouted Calhoun, spurring onwards, as a sign that the order was to be obeyed.

The teams are again set in motion; and, after advancing to the edge of the burnt tract, are once more brought to a stand.

Far as the eye can reach the country is of one uniform colour – black. There is nothing green!

In front – on the right and left – extends the scene of desolation. Over it the cerulean sky is changed to a darker blue; the sun, though clear of clouds, seems to scowl rather than shine.

The overseer has made a correct report – there is no trail visible. The action of the fire has eliminated the impression of the wheels hitherto indicating the route.

“What are we to do?”

The planter himself put this inquiry, in a tone that told of a vacillating spirit.

“What else but keep straight on, uncle Woodley? The river must be on the other side? If we don’t hit the crossing, to a half mile or so, we can go up, or down the bank – as the case may require.”

“Well, nephew, you know best: I shall be guided by you.”

The ex-officer of volunteers with confident air trots onward. The waggon-train is once more in motion.

A mile or more is made, apparently in a direct line from the point of starting. Then there is a halt. The self-appointed guide has ordered it. He appears to be puzzled about the direction.

“You’ve lost the way, nephew?” said the planter, riding rapidly up.

“Damned if I don’t believe I have, uncle!” responded the nephew, in a tone of not very respectful mistrust. “No, no!” he continued, reluctant to betray his embarrassment as the carriole came up. “I see now. We’re all right yet. The river must be in this direction. Come on!”

Once more they are stretching their teams along a travelled road – where a half-score[4] of wheeled vehicles must have passed before them. And not long before: the hoof-prints of the animals fresh as if made within the hour. A train of waggons, not unlike their own, must have passed over the burnt prairie!

Like themselves, it could only be going towards the Leona. In that case they have only to keep in the same track.

For a mile or more the waggon-tracks are followed. The countenance of Cassius Calhoun, for a while wearing a confident look, gradually becomes clouded. It assumes the profoundest expression of despondency, on discovering that the four-and-forty wheel-tracks he is following, have been made by ten Pittsburgh waggons, and a carriole – the same that are now following him, and in whose company he has been travelling all the way from the Gulf of Matagorda!

***

Beyond doubt, the waggons of Woodley Poindexter were going over ground already traced by the tiring of their wheels.

“Our own tracks!” muttered Calhoun on making the discovery.

“Our own tracks! What mean you, Cassius? You don’t say we’ve been travelling—”

“On our own tracks. I do, uncle; that very thing. That’s the very hill we went down as we left our last stopping place. We’ve made a couple of miles for nothing.”

Embarrassment is no longer the only expression upon the face of the speaker. It has deepened to chagrin, with an admixture of shame. He feels it keenly as the carriole comes up, and bright eyes become witnesses of his discomfiture.

There is a general halt, succeeded by an animated conversation among the white men. The situation is serious: the planter himself believes it to be so. He cannot that day reach the end of his journey – a thing upon which he had set his mind.

How are they to find their way?

Calhoun no longer volunteers to point out the path.

A ten minutes’ discussion terminates in nothing. No one can suggest a feasible plan of proceeding.

Another ten minutes is spent in the midst of moral and physical gloom. Then, as if by a benignant mandate from heaven, does cheerfulness resume its sway. The cause? A horseman riding in the direction of the train!

An unexpected sight: who could have looked for human being in such a place? All eyes simultaneously sparkle with joy; as if, in the approach of the horseman, they beheld the advent of a saviour!

“A Mexican!” whispered Henry, drawing his deduction from the habiliments of the horseman.

“So much the better,” replied Poindexter, in the same tone of voice; “he’ll be all the more likely to know the road.”

“Not a bit of Mexican about him,” muttered Calhoun,” excepting the rig. I’ll soon see. Buenos dias, cavallero! Esta V. Mexicano?” (Good day, sir! are you a Mexican?)

“No, indeed,” replied the stranger, with a protesting smile. “I can speak to you in Spanish, if you prefer it; but I dare say you will understand me better in English: which, I presume, is your native tongue?”

“American, sir,” replied Poindexter. Then, as if fearing to offend the man from whom he intended asking a favour, he added: “Yes, sir; we are all Americans – from the Southern States.”

“That I can perceive by your following.” An expression of contempt showed itself upon the countenance of the speaker, as his eye rested upon the groups of black bondsmen. “I can perceive, too,” he added, “that you are strangers to prairie travelling. You have lost your way?”

“We have, sir; and have very little prospect of recovering it, unless we may count upon your kindness to direct us.”

“Not much kindness in that. By chance I came upon your trail, as I was crossing the prairie. I saw you were going astray; and have ridden this way to set you right.”

“It is very good of you. We shall be most thankful, sir. My name is Woodley Poindexter, of Louisiana. I have purchased a property on the Leona river, near Fort Inge. We were in hopes of reaching it before nightfall. Can we do so?”

“There is nothing to hinder you: if you follow the instructions I shall give.”

On saying this, the stranger rode a few paces apart; and appeared to scrutinise the country – as if to determine the direction which the travellers should take.

A blood-bay[5] steed, such as might have been ridden by an Arab sheik. On his back a rider – a young man of not more than five-and-twenty – of noble form and features, dressed in the picturesque costume of a Mexican rancher[6]. Thus looked the horseman, upon whom the planter and his people were gazing.

Through the curtains of the travelling carriage he was regarded with glances that spoke of a singular sentiment. For the first time in her life, Louise Poindexter looked upon that – hitherto known only to her imagination—a man of heroic mould.[7] Proud might he have been, could he have guessed the interest which his presence was exciting in the breast of the young Creole.[8]

“By my faith!” he declared, facing round to the owner of the waggons, “I can discover no landmarks for you to steer by. For all that, I can find the way myself. You will have to cross the Leona five miles below the Fort; and, as I have to go by the crossing myself, you can follow the tracks of my horse. But you may not be able to distinguish them”, said the horseman after a pause, “the more so, that in these dry ashes all horse-tracks are so nearly alike.”

“What are we to do?” despairingly asked the planter.

“I am sorry, Mr Poindexter, I cannot stay to conduct you, I am riding express, with a despatch for the Fort. If you should lose my trail, keep the sun on your right shoulders: so that your shadows may fall to the left, at an angle of about fifteen degrees to your line of march. Go straight forward for about five miles. You will then come in sight of the top of a tall tree – a cypress.[9] Head direct for this tree. It stands on the bank of the river; and close by is the crossing.”

The young horseman, once more drawing up his reins, was about to ride off; when something caused him to linger. It was a pair of dark lustrous eyes – observed by him for the first time – glancing through the curtains of the travelling carriage.

He perceived, moreover, that they were turned upon himself – fixed, as he fancied, in an expression that betokened interest – almost tenderness!

He returned it with an involuntary glance of admiration, which he made but an awkward attempt to conceal.

“You are very kind, sir,” said Poindexter; “but with the directions you have given us, I think we shall be able to manage. The sun will surely show us —”

“No: now I look at the sky, it will not. There are clouds looming up on the north. In an hour, the sun may be obscured – at all events, before you can get within sight of the cypress. It will not do. Stay!” he continued, after a reflective pause, “I have a better plan still: follow the trail of my lazo!”

While speaking, he had lifted the coiled rope and flung the loose end to the earth – the other being secured to a ring in the pommel. Then raising his hat in graceful salutation – more than half directed towards the travelling carriage – he gave the spur to his steed.

The lazo, lengthening out, tightened over the hips of his horse; and, dragging a dozen yards behind, left a line upon the cinereous surface.

Answer the following questions:

1) Who is the owner of the train? Where is he from? Where is he going to?

2) Who accompanies the planter?

3) Why is it hard to find the way?

4) Why did the overseer stop? Who becomes a new guide?

5) Who had left those wheel-tracks that Cassius Calhoun decided to follow?

6) Why did Calhoun’s confident look become clouded?

7) Who helped the travellers find the way? How did he do it?

8) Why didn’t the horseman stay with the travellers to conduct them?

Chapter Two

“An exceedingly curious fellow!” remarked the planter, as they stood gazing after the horseman. “I ought to have asked him his name?”

“An exceedingly conceited fellow, I should say,” muttered Calhoun; who had not failed to notice the glance sent by the stranger in the direction of the carriole, nor that which had challenged it.

“Come, cousin Cash,” protested young Poindexter; “you are unjust to the stranger. He appears to be educated – in fact, a gentleman.”

During this brief conversation, the fair occupant of the carriole was seen to bend forward; and direct a look of evident interest, after the form of the horseman fast receding from her view.

To this, perhaps, might have been traced the acrimony observable in the speech of Calhoun.

“What is it, Loo?” he inquired, riding close up to the carriage, and speaking in a voice not loud enough to be heard by the others. “You appear impatient to go forward? Perhaps you’d like to ride off along with that fellow? It isn’t too late: I’ll lend you my horse.”

The young girl threw herself back upon the seat – evidently displeased, both by the speech and the tone in which it was delivered. A clear ringing laugh was her only reply.

“So, so! I thought there must be something – by the way you behaved yourself in his presence. You looked as if you would have relished a tete-a-tete with this despatch-bearer. No doubt the letter carrier, employed by the officers at the Fort!”

“A letter carrier, you think? Oh, how I should like to get love letters by such a postman!”

“You had better hasten on, and tell him so. My horse is at your service.”

“Ha! ha! ha! What a simpleton you show yourself! Suppose, I did have a fancy to overtake this prairie postman! It couldn’t be done upon that dull steed of yours: not a bit of it! Oh, no! he’s not to be overtaken by me, however much I might like it; and perhaps I might like it!”

“Don’t let your father hear you talk in that way.”

“Don’t let him hear you talk in that way,” retorted the young lady, for the first time speaking in a serious strain. “Though you are my cousin, and papa may think you the pink of perfection,[10] I don’t! I never told you I did – did I?” A frown, evidently called forth by some unsatisfactory reflection, was the only reply to this interrogative.

“You are my cousin,” she continued, “but you are nothing more – nothing more – Captain Cassius Calhoun! You have no claim to be my counsellor. I shall remain mistress of my own thoughts – and actions, too – till I have found a master who can control them. It is not you!”

The closing curtains indicated that further conversation was not desired.

***

The travellers felt no further uneasiness about the route. The snake-like trail was continuous; and so plain that a child might have followed it.

Cheered by the prospect of soon terminating a toilsome journey – as also by the pleasant anticipation of beholding his new purchase – the planter was in one of his happiest moods. The planter’s high spirits were shared by his party, Calhoun alone excepted.

However this joyfulness should was after a time interrupted by causes and circumstances over which they had not the slightest control.

“Look, father! don’t you see them?” said Henry in a voice that betokened alarm.

“Where, Henry – where?”

“Behind the waggons. You see them now?”

“I do – though I can’t say what they are. They look like – like – I really don’t know what.”

Against the northern horizon had suddenly lifted a number of dark columns – half a score of them – unlike anything ever seen before. They were constantly changing size, shape, and place.

In the proximity of phenomena never observed before – unknown to every individual of the party – it was but natural these should be inspired with alarm.

A general halt had been made on first observing the strange objects: the negroes on foot, as well as the teamsters, giving utterance to shouts of terror. The animals – mules as well as horses, had come instinctively to a stand. The danger, whatever it might be, was drawing nearer!

Consternation became depicted on the countenances of the travellers. The eyes of all were turned towards the lowering sky, and the band of black columns that appeared coming on to crush them!

At this crisis a shout, reaching their ears from the opposite side, was a source of relief – despite the unmistakable accent of alarm in which it was uttered.

Turning, they beheld a horseman in full gallop – riding direct towards them.

The horse was black as coal: the rider of like hue, even to the skin of his face. For all that he was recognised: as the stranger, upon the trail of whose lazo they had been travelling.

“Onward!” he cried, as soon as within speaking distance. “On – on! as fast as you can drive!”

“What is it?” demanded the planter, in bewildered alarm. “Is there a danger?”

“There is. I did not anticipate it, as I passed you. It was only after reaching the river, I saw the sure signs of it.”

“Of what, sir?”

“The norther.”[11]

“I never heard of its being dangerous,” interposed Calhoun, “except to vessels at sea. It’s precious cold, I know; but—”

“You’ll find it worse than cold, sir,” interrupted the young horseman, “if you’re not quick in getting out of its way. Mr Poindexter,” he continued, turning to the planter, and speaking with impatient emphasis, “I tell you, that you and your party are in peril. A norther is not always to be dreaded. Those black pillars are nothing – only the precursors of the storm. Look beyond! Don’t you see a black cloud spreading over the sky? That’s what you have to dread. You have no chance to escape it, except by speed. If you do not make haste, it will be too late. Order your drivers to hurry forward as fast as they can!”

The planter did not think of refusing compliance, with an appeal urged in such energetic terms. The order was given for the teams to be set in motion, and driven at top speed.

The travelling carriage moved in front, as before. The stranger alone threw himself in the rear – as if to act as a guard against the threatening danger.

At intervals he was observed to rein up his horse, and look back: each time by his glances betraying increased apprehension.

Perceiving it, the planter approached, and asked him:

“Is there still a danger?”

“I am sorry to answer you in the affirmative,” said he: “Are your mules doing their best?”

“They are: they could not be driven faster.”

“I fear we shall be too late, then!”

“Good God, sir! is the danger so great? Can we do nothing to avoid it?”

The stranger did not make immediate reply. For some seconds he remained silent, as if reflecting – his glance no longer turned towards the sky, but wandering among the waggons.

“There is!” joyfully responded the horseman, as if some hopeful thought had at length suggested itself. “There is a chance. I did not think of it before. We cannot shun the storm – the danger we may. Quick, Mr Poindexter! Order your men to muffle the mules – the horses too – otherwise the animals will be blinded, and go mad. When that’s done, let all seek shelter within the waggons.”

The planter and his son sprang together to the ground; and retreated into the travelling carriage.

Calhoun, refusing to dismount, remained stiffly seated in his saddle.

“Once again, sir, I adjure you to get inside! If you do not you’ll have cause to repent it. Within ten minutes’ time, you may be a dead man!”

The ex-officer was unable to resist the united warnings of earth and heaven; and, slipping out of his saddle with a show of reluctance – intended to save appearances – he clambered into the carriage.

To describe what followed is beyond the power of the pen. No eye beheld the spectacle: for none dared look upon it. In five minutes after the muffling of the mules, the train was enveloped in worse than Cimmerian darkness[12].

In another instant the norther was around them; and the waggon train was enveloped in an atmosphere, akin to that which congeals the icebergs of the Arctic Ocean! Nothing more was seen – nothing heard, save the whistling of the wind, or its hoarse roaring.

For over an hour did the atmosphere carry this cinereous cloud.

At length a voice, speaking close by the curtains of the carriole, announced their release.

“You can come forth!” said the stranger. “You will still have the storm to contend against. But you have nothing further to fear. The ashes are all swept off.”

“Sir!” said the planter, hastily descending the steps of the carriage, “we have to thank you for – for—”

“Our lives, father!” cried Henry, supplying the proper words. “I hope, sir, you will favour us with your name?”

“Maurice Gerald!” returned the stranger; “though, at the Fort, you will find me better known as Maurice the mustanger”.[13]

“A mustanger!” scornfully muttered Calhoun, but only loud enough to be heard by Louise.

“For guide, you will no longer need either myself, or my lazo,” said the hunter of wild horses. “The cypress is in sight: keep straight towards it. After crossing, you will see the flag over the Fort. I must say goodbye.”

Satan himself, astride a Tartarean steed,[14] could not have looked more like the devil than did Maurice the Mustanger, as he separated for the second time from the planter and his party. But neither his ashy envelope, nor the announcement of his humble calling, could damage him in the estimation of one, whose thoughts were already predisposed in his favour – Louise Poindexter.

“Maurice Gerald!” muttered the young Creole, “whoever you are – whence you have come – whither you are going – what you may be – henceforth there is a fate between us! I feel it – I know it– sure as there’s a sky above!”

Answer the following questions:

1) What was the reason of the quarrel between Captain Calhoun and Louise?

2) What frightened Woodley Poindexter and his companions? How did they avoid the danger?

3) What is the horseman’s name? How is he known at the Fort? Why?

4) What is Louise’s attitude to Maurice?

Chapter Three

On the banks of the Alamo stood a dwelling, unpretentious as any to be found within the limits of Texas, and certainly as picturesque.

The structure was in shadow, a little retired among the trees; as if the site had been chosen with a view to concealment. It could have been seen but by one passing along the bank of the stream; and then only with the observer directly in front of it. Its rude style of architecture, and russet hue, contributed still further to its inconspicuousness.

The house was a mere cabin – with only a single aperture, the door – if we except the flue of a chimney. The doorway had a door, a light framework of wood, with a horse-skin stretched over it.

In the rear was an open shed, around this was a small enclosure.

A still more extensive enclosure, extended rearward from the cabin, terminating against the bluff. Its turf tracked and torn by numerous hoof-prints told of its use: a “corral”[15] for wild horses – mustangs.

The interior of the hut was not without some show of neatness and comfort. The sheeting of mustang-skins covered the walls. The furniture consisted of a bed, a couple of stools and a rude table. Something like a second sleeping place appeared in a remote corner.

What was least to be expected in such a place, was a shelf containing about a score of books, with pens, ink, and also a newspaper lying upon the table.

Further proofs of civilization presented themselves in the shape of a large leathern portmanteau, a double-barrelled gun, a drinking cup, a hunter’s horn, and a dog-call.

Upon the floor were a few culinary utensils, mostly of tin; while in one corner stood a demijohn,[16] evidently containing something stronger than the water of the Alamo.

Such was the structure of the mustanger’s dwelling – such its interior and contents, with the exception of its living occupants – two in number.

On one of the stools standing in the centre of the floor was seated a man, who could not be the mustanger himself. In no way did he present the semblance of a proprietor. On the contrary, the air of the servitor was impressed upon him beyond the chance of misconstruction.

He was a round plump man, with carrot-coloured hair and a bright ruddy skin, dressed in a suit of stout stuff. His lips, nose, eyes, air, and attitude, were all unmistakably Irish.

Couched upon a piece of horse-skin, in front of the fire was a huge Irish staghound,[17] that looked as if he understood the speech of the man.

Whether he did so or not, it was addressed to him, as if he was expected to comprehend every word.

“Oh, Tara, my jewel!” exclaimed the man fraternally interrogating the hound; “don’t you wish now to be back in Ballyballagh? Wouldn’t you like to be once more in the courtyard of the old castle! But there’s no knowing when the young master will go back, and take us along with him.

“I’d like a drop now,” continued the speaker, casting a covetous glance towards the jar. “No-no; I won’t touch the whisky. I’ll only draw the cork out of the demijohn, and take a smell at it. Sure the master won’t know anything about that; and if he did, he wouldn’t mind it!”

During the concluding portion of this utterance, the speaker had forsaken his seat, and approached the corner where stood the jar.

He took up the demijohn and drew out the stopper. After half a dozen “smacks” of the mouth, with exclamations denoting supreme satisfaction, he hastily restored the stopper; returned the demijohn to its place; and glided back to his seat upon the stool.

“Tara, you old thief!” said he, addressing himself once more to his canine companion, “it was you that tempted me! No matter, man: the master will never miss it; besides, he’s going soon to the Fort, and can lay in a fresh supply.

“I wonder,” muttered he, “what makes Master Maurice so anxious to get back to the Settlements. He says he’ll go whenever he catches that spotty mustang he has seen lately. I suppose it must be something beyond the common. He says he won’t give it up, till he catches it. Hush! what’s that?”

Tara springing up from his couch of skin, and rushing out with a low growl, had caused the exclamation.

“Phelim!” called a voice from the outside. “Phelim!”

“It’s the master,” muttered Phelim, as he jumped from his stool, and followed the dog through the doorway.

Phelim was not mistaken. It was the voice of his master, Maurice Gerald. As the servant should have expected, his master was mounted upon his horse.

The blood-bay was not alone. At the end of the lazo – drawn from the saddle tree – was a captive. It was a mustang of peculiar appearance, as regarded its markings; which were of a kind rarely seen. The colour of the mustang was a ground of dark chocolate in places approaching to black – with white spots distributed over it.

The creature was of perfect shape. It was of large size for a mustang, though much smaller than the ordinary English horse.

Phelim had never seen his master return from a horse-hunting excursion in such a state of excitement; even when coming back – as he often did – with half a dozen mustangs led loosely at the end of his lazo.

“Master Maurice, you have caught the spotty at last!” cried he, as he set eyes upon the captive. “It’s a mare! Where will you put her, master? Into the corral, with the others?”

“No, she might get kicked among them. We shall tie her in the shed. Did you ever see anything so beautiful as she is, Phelim – I mean in the way of horseflesh?”

“Never, Master Maurice; never, in all my life!

The spotted mare was soon stabled in the shed, Castro being temporarily attached to a tree.

The mustanger threw himself on his horse-skin couch, wearied with the work of the day. The capture of the spotted mustang had cost him a long and arduous chase – such as he had never ridden before in pursuit of a mustang.

Notwithstanding that he had spent several days in the saddle – the last three in constant pursuit of the spotted mare – he was unable to obtain repose. At intervals he rose to his feet, and paced the floor of his hut, as if stirred by some exciting emotion.

For several nights he had slept uneasily till not only his henchman[18] Phelim, but his hound Tara, wondered what could be the meaning of his unrest.

At length Phelim determined on questioning his master as to the cause of his inquietude.

“Master Maurice, what is the matter with you?”

“Nothing, Phelim – nothing! What do you mean?”

“What do I mean? Why, that whenever you close your eyes and think you are sleeping, you begin palavering! You are always trying to pronounce a big name that appears to have no ending, though it begins with a point!”

“A name! What name?”

“I can’t tell you exactly. It’s too long for me to remember, seeing that my education was entirely neglected. But there’s another name that you put before it; and that I can tell you. It’s Louise that you say, Master Maurice; and then comes the point.”

“Ah!” interrupted the young Irishman, evidently not caring to converse longer on the subject. “Some name I may have heard – somewhere, accidentally. One does have such strange ideas in dreams!”

“In your dreams, master, you talk about a girl looking out of a carriage with curtains to it, and telling her to close them against some danger that you are going to save her from.”

“I wonder what puts such nonsense into my head? But come! You forget that I haven’t tasted food since morning. What have you got?”

“There’s only the cold venison and the corn-bread. If you like I’ll put the venison in the pot”.

“Yes, do so. I can wait.”

Phelim was about stepping outside, when a growl from Tara, accompanied by a start, and followed by a rush across the floor, caused the servitor to approach the door with a certain degree of caution.

The individual, who had thus freely presented himself in front of the mustanger’s cabin, was as unlike either of its occupants, as one from the other.

He stood fall six feet high, in a pair of tall boots, fabricated out of tanned alligator skin. A deerskin undershirt, without any other, covered his breast and shoulders; over which was a “blanket coat,” that had once been green. He was equipped in the style of a backwoods hunter. There was no embroidery upon his coarse clothing. Everything was plain almost to rudeness.

The individual was apparently about fifty years of age, with a complexion inclining to dark, and features that, at first sight, exhibited a grave aspect.

It was Zebulon Stump, or “Old Zeb Stump,” as he was better known to the very limited circle of his acquaintances.

“Kentuckian, by birth and raising,”—as he would have described himself, if asked the country of his nativity. The hunter had passed the early part of his life among the forests of the Lower Mississippi; and now, at a later period, he was living and hunting in the wilds of south-western Texas.

The behaviour of the staghound told of a friendly acquaintance between Zeb Stump and Maurice the mustanger.

“Evening!” laconically saluted Zeb.

“Good evening, Mr Stump!” rejoined the owner of the hut, rising to receive him. “Step inside, and take a seat! On foot, Mr Stump, as usual?”

“No: I got my old creature out there, tied to a tree.”

“Let Phelim take her round to the shed. You’ll have something to eat? Phelim was just getting supper ready. I’m sorry I can’t offer you anything very dainty. I’ve been so occupied, for the last three days, in chasing a very curious mustang, that I never thought of taking my gun with me.”

“What sort of a mustang?” inquired the hunter.

“A mare; with white spots on a dark chocolate ground – a splendid creature!”

“That’s the very business that’s brought me over to you. I’ve seen that mustang several times out on the prairie, and I just wanted you to go after her. I’ll tell you why. I’ve been to the Leona settlements since I saw you last, and since I saw her too. Well, there has come a man that I knew on the Mississippi. He is a rich planter, his name is Poindexter.”

“Poindexter?”

“That is the name – one of the best known on the Mississippi from Orleans to Saint Louis. He was rich then; and, I reckon, isn’t poor now – seeing as he’s brought about a hundred niggers along with him. Beside, there’s his nephew, by name Calhoun. He’s got the dollars, and nothing to do with them but lend them to his uncle – the which, for a certain reason, I think he will. Now, young fellow, I’ll tell you why I wanted to see you. That planter has got a daughter, she’s fond of horses. She heard me telling her father about the spotted mustang; and nothing would content her there and then, till he promised he’d offer a big price for catching the creature. He said he’d give a couple of hundred dollars for the animal. So, saying nothing to nobody, I came over here, fast as my old mare could fetch me.”

“Will you step this way, Mr Stump?” said the young Irishman, rising from his stool, and proceeding in the direction of the door.

The hunter followed, not without showing some surprise at the abrupt invitation.

Maurice conducted his visitor round to the rear of the cabin; and, pointing into the shed, inquired—

“Does that look anything like the mustang you’ve been speaking of?”

“Dog-gone my cats, if it’s not the same! Caught already! Two hundred dollars! Young fellow, you’re in luck: two hundred, – and the animal’s worth every cent of the money! Won’t Miss Poindexter be pleased!”

Answer the following questions:

1) How does Maurice’s dwelling characterize its owner? Describe it.

2) Who is Phelim?

3) Who is Maurice’s new captive?

4) Why was Maurice unable to obtain repose? What did he talk about in his dreams?

5) Who is Zeb Stump? What did he come for?

Chapter Four

The estate, or “hacienda,”[19] known as Casa del Corvo, extends along the wooded bottom of the Leona River. A structure of superior size whose white walls show conspicuously against the green background of forest with which it is half encircled. It is the newly acquired estate of the Louisiana planter and his family.

Louise Poindexter flung herself into a chair in front of her dressing-glass, and directed her maid Florinda to prepare her for the reception of guests. It was the day fixed for the “house-warming,”[20] and about an hour before the time appointed for dinner to be on the table.

Soon they loud voices were heard in the courtyard.

“Oh, Mr Zebulon Stump, is it you?” exclaimed a silvery voice, followed by the appearance of Louise Poindexter upon the verandah.

“I didn’t expect to see you so soon,” continued the young lady, “you said you were going upon a long journey. Well – I am pleased that you are here; and so will papa and Henry be. Pluto! go instantly to Chloe, the cook, and see what she can give you for Mr Stump’s dinner.

Zeb told Louise that he had come to talk to her father about the spotted mustang that he’d promised to purchase for her. She asked who caught it, and the hunter told her it was a mustanger.

“His name?”

“Well, as to the name of his family, I’ve never heard it. He’s known up there about the Fort as Maurice the mustanger.”

The old hunter was not sufficiently observant to take note of the tone of eager interest in which the question had been asked, nor the sudden deepening of colour upon the cheeks of the questioner as she heard the answer. Neither had escaped the observation of Florinda.

“Miss Looey!” exclaimed the latter, “that’s the name of the brave young white gentleman – that saved us in the black prairie?”

“Yes!” resumed the hunter, relieving the young lady from the necessity of making reply. “He told me of that circumstance this very morning, before we started. That’s the very fellow as has trapped the spotty; and he is trotting the creature along at this identical minute, in company with about a dozen others. He ought to be here before sundown. I pushed my old mare ahead, to tell your father the spotty was coming, and let him get the first chance of buying. I thought of you, Miss Louise!”

Lightly did Louise Poindexter trip back across the corridor. Only after entering her chamber, did she give way to a reflection of a more serious character, that found expression in words low murmured, but full of mystic meaning —

“It is my destiny: I feel – I know that it is! I dare not meet, and yet I cannot shun it – I may not – I would not – I will not!”

***

On that same evening, after the dining-hall had been deserted, the roof, instead of the drawing-room, was chosen as the place of re-assemblage.

The company now collected to welcome the advent of Woodley Poindexter on his Texan estate, were the elite of the Settlements – not only of the Leona, but of others more distant.

His lovely daughter Louise – the fame of whose beauty had been before her, even in Texas – acted as mistress of the ceremonies – moving about among the admiring guests with the smile of a queen, and the grace of a goddess.

To say that Louise Poindexter was beautiful would only be to repeat the universal verdict of the society that surrounded her. A single glance was sufficient to satisfy any one upon this point – strangers as well as acquaintances.

She was the cynosure of a hundred pairs of eyes, the happiness of a score of hearts, and perhaps the torture of as many more.

But mingling in that splendid crowd was a man who, perhaps, more than any one present, watched her every movement; and endeavoured more than any other to interpret its meaning. It was Cassius Calhoun.

At intervals, not very wide apart, the young mistress might have been seen to approach the parapet, and look across the plain, with a glance that seemed to interrogate the horizon of the sky.

Why she did so no one could tell. No one presumed to conjecture, except Cassius Calhoun. He had thoughts upon the subject – thoughts that were torturing him.

When a group of moving forms appeared upon the prairie, emerging from the light of the setting sun – when the spectators pronounced it a drove of horses in charge of some mounted men – the ex-officer of volunteers had a suspicion as to who was conducting that cavalcade.

“Wild horses!” announced the major commandant of Fort Inge, after a short inspection through his pocket telescope. “Some one bringing them in,” he added, a second time raising the glass to his eye. “Oh! I see now – it’s Maurice the mustanger. He appears to be coming direct to your place, Mr Poindexter.”

“I am sure of it,” said the planter’s son. “I can tell that horseman to be Maurice Gerald.”

The cavalcade came up, Maurice sitting handsomely on his horse, with the spotted mare at the end of his lazo. The mustanger looked splendid, despite his travel-stained habiliments. His journey of over twenty miles had done little to fatigue him.

“What a beautiful creature!” exclaimed several voices, as the captured mustang was led up in front of the house.

“Surely,” said Poindexter, “this must be the animal of which old Zeb Stump has been telling me?”

“Ye-es, Mister Poindexter; the identical creature – a mare,” answered Zeb Stump, making his way towards Maurice with the design of assisting him.

“I shall owe you two hundred dollars for this,” said the planter, addressing himself to Maurice, and pointing to the spotted mare. “I think that was the sum stipulated for by Mr Stump.”

“I was not a party to the stipulation,” replied the mustanger, with a significant but well-intentioned smile. “I cannot take your money. She is not for sale. You have given me such a generous price for my other captives that I can afford to make a present – what we over in Ireland call a `luckpenny.’ It is our custom there also, when a horse-trade takes place at the house, to give the douceur, not to the purchaser himself, but to one of the fair members of his family. May I have your permission to introduce this fashion into the settlements of Texas?”

“Oh, certainly, Mr Gerald!” replied the planter, “as you please about that.”

“This mustang is my luckpenny; and if Miss Poindexter will condescend to accept of it, I shall feel more than repaid for the three days’ chase which the creature has cost me.”

“I accept your gift, sir; and with gratitude,” responded the young Creole – stepping freely forth as she spoke. “But I have a fancy,” she continued, pointing to the mustang – at the same time that her eye rested on the countenance of the mustanger—”a fancy that your captive is not yet tamed? She may yet kick against the traces, if she find the harness not to her liking; and then what am I to do – poor I?”

“True, Maurice!” said the major, widely mistaken as to the meaning of the mysterious speech, and addressing the only man on the ground who could possibly have comprehended it; “Miss Poindexter speaks very sensibly. That mustang has not been tamed yet – any one may see it. Come, my good fellow! give her the lesson. She looks as though she would put your skill to the test.”

“You are right, major: she does!” replied the mustanger, with a quick glance, directed not towards the captive quadruped, but to the young Creole.

It was a challenge to skill – to equestrian prowess[21]—and he proclaimed his acceptance of it by leaping lightly out of his saddle, resigning his own steed to Zeb Stump, and exclusively giving his attention to the captive.

It was the first time the wild mare had ever been mounted by man. With equine instinct, she reared upon her hind legs, for some seconds balancing her body in an erect position. Twice or three times the mustang tried to throw off her rider, but the endeavours were foiled by the skill of the mustanger; and then, as if conscious that such efforts were idle, the enraged animal sprang away from the spot and entered upon a gallop.

Conjectures that the mustanger might be killed, or, at the least, badly “crippled,” were freely ventured during his absence; and there was one who wished it so. But there was also one upon whom such an event would have produced a painful impression – almost as painful as if her own life depended upon his safe return.

Soon Maurice the mustanger came riding back across the plain, with the wild mare between his legs – no more wild – no longer desiring to destroy him.

“Miss Poindexter!” said the mustanger, gliding to the ground, “may I ask you to step up to her, throw this lazo over her neck, and lead her to the stable? By so doing, she will regard you as her tamer; and ever after submit to your will.”

Without a moment’s hesitation – without the slightest show of fear – Louise stepped forth from the aristocratic circle; as instructed, took hold of the horsehair rope and whisked it across the neck of the tamed mustang.

Answer the following questions:

1) What was Louise preparing for?

2) What news did Zeb Stump bring?

3) Read this extract again:

Conjectures that the mustanger might be killed, or, at the least, badly “crippled,” were freely ventured during his absence; and there was one who wished it so. But there was also one upon whom such an event would have produced a painful impression – almost as painful as if her own life depended upon his safe return.

Who are these two?

4) Did Maurice sell the spotted mustang? What did he do with it?

Chapter Five

The first rays of light, saluting the flag of Fort Inge, fell upon a small waggon that stood in front of the “officers’ quarters”. A party of somewhat different appearance commenced assembling on the parade-ground. They were preparing for a picnic. Most, if not all, who had figured at Poindexter’s dinner party, were soon upon the ground.

The planter himself was present; as also his son Henry, his nephew Cassius Calhoun, and his daughter Louise – the young lady mounted upon the spotted mustang.

The affair was a reciprocal treat – a simple return of hospitality; the major and his officers being the hosts, the planter and his friends the invited guests. The entertainment about to be provided was equally appropriate to the time and place. The guests of the cantonment were to be gratified by witnessing a spectacle – a chase of wild steeds! The arena of the sport could only be upon the wild-horse prairies – some twenty miles to the southward of Fort Inge.

The party was provided with a guide – a horseman completely costumed and equipped, mounted upon a splendid steed.

“Come, Maurice!” cried the major, on seeing that all had assembled, “we’re ready to be conducted to the game. Ladies and gentlemen! this young fellow is thoroughly acquainted with the haunts and habits of the wild horses. If there’s a man in Texas, who can show us how to hunt them, it is Maurice the mustanger.”

***

“To the saddle!” was the thought upon every mind, and the cry upon every tongue when a drove of wild mares was seen in the distance. Before a hundred could have been deliberately counted, every one, ladies and gentlemen alike, was in the stirrup.

By this time the wild mares appeared coming over the crest of the ridge. They were going at mad gallop, as if fleeing from a pursuer – some dreaded creature that was causing them to snort! They were chased by donkey, almost as large as any of the mustangs.

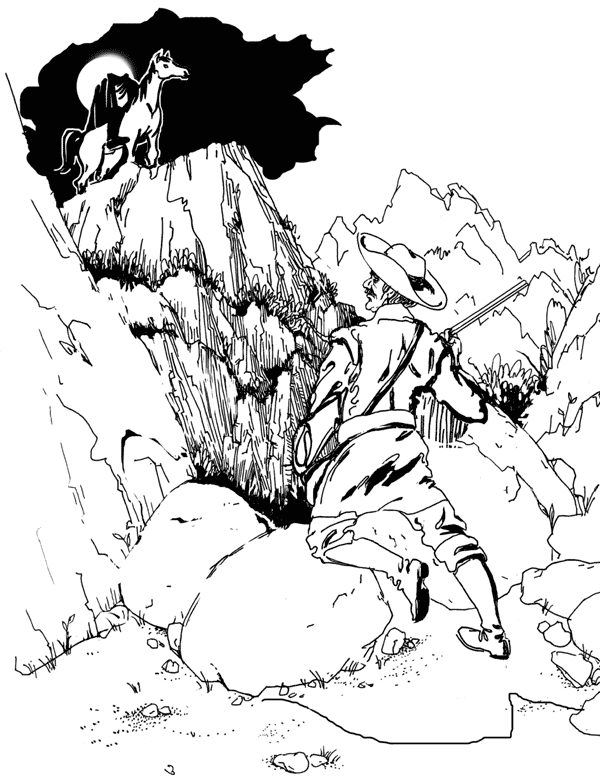

“I must stop him!” exclaimed Maurice, “or the mares will run on till the end of daylight.”

Half a dozen springs of the blood bay, guided in a diagonal direction, brought his rider within casting distance; and like a flash of lightning, the loop of the lazo was seen descending over the long ears. Then the animal was seen to rise erect on its hind legs, and fall heavily backward upon the grass.

The incident caused a postponement of the chase. All awaited the action of the guide, when he suddenly sprang to his saddle with a quickness that betokened some new cause of excitement.

The cause for the eccentric change of tactics was that Louise Poindexter, mounted on the spotted mustang, had suddenly separated from the company, and was galloping off after the wild mares!

That unexpected start could scarcely be an intention – except on the part of the spotted mustang? Maurice had recognised the drove, as the same from which he had himself captured it: and, no doubt, with the design of rejoining its old associates, it was running away with its rider!

Stirred by gallantry, half the field spurred off in pursuit. But few, if any, of the gentlemen felt actual alarm. All knew that Louise Poindexter was a splendid equestrian. There was one who did not entertain this confident view. It was he who had been the first to show anxiety – the mustanger himself.

The sun, looking down from the zenith, gave light to a singular tableau. A herd of wild mares going at reckless speed across the prairie; one of their own kind, with a lady upon its back, following about four hundred yards behind; at a like distance after the lady, a steed of red bay colour, bestridden by the mustanger, and apparently intent upon overtaking her; still further to the rear a string of mounted men.

In twenty minutes the herd gained distance upon the spotted mustang; the mustang upon the blood bay; and the blood bay – ah! his competitors were no longer in sight.

For another mile the chase continued, without much change.

“What if I lose sight of her? In truth, it begins to look queer! It would be an awkward situation for the young lady. Worse than that – there’s danger in it – real danger. If I should lose sight of her, she’d be in trouble to a certainty!”

Thus muttering, Maurice rode on: his eyes now fixed upon the form still flitting away before him; at intervals interrogating, with uneasy glances, the space that separated him from it.

At this crisis the drove disappeared from the sight both of the blood-bay and his master; and most probably at the same time from that of the spotted mustang and its rider.

The effect produced upon the runaway[22] appeared to proceed from some magical influence. As if their disappearance was a signal for discontinuing the chase, it suddenly slackened pace; and the instant after came to a standstill!

“Miss Poindexter!” Maurice said, as he spurred his steed within speaking distance: “I am glad that you have recovered command of that wild creature. I was beginning to be alarmed about—”

“About what, sir?” was the question that startled the mustanger.

“Your safety – of course,” he replied, somewhat stammeringly.

“Oh, thank you, Mr Gerald; but I was not aware of having been in any danger. Was I really so?”

“Any danger!” echoed the Irishman, with increased astonishment. “On the back of a runaway mustang – in the middle of a pathless prairie!”

“And what of that? The thing couldn’t throw me. I’m too clever in the saddle, sir.”

“I know it, madame; but suppose you had fallen in with—”

“Indians!” interrupted the lady, without waiting for the mustanger to finish his hypothetical speech. “And if I had, what would it have mattered?”

“No; not Indians exactly – at least, it was not of them I was thinking.”

“Some other danger? What is it, sir? You will tell me, so that I may be more cautious for the future?”

Maurice did not make immediate answer. A sound striking upon his ear had caused him to turn away. They heard a shrill scream, succeeded by another and another, close followed by a loud hammering of hoofs.

It was no mystery to the hunter of horses.

“The wild stallions!” he exclaimed, in a tone that betokened alarm. “I knew they must be among those hills; and they are!”

“Is that the danger of which you have been speaking?”

“It is. At other times there is no cause to fear them. But just now, at this season of the year, they become as savage as tigers, and equally as vindictive.”

“What are we to do?” inquired the young lady, now, for the first time, giving proof that she felt fear – by riding close up to the man who had once before rescued her from a situation of peril. “Why should we not ride off at once, in the opposite direction?”

“‘It would be of no use. There’s no cover to conceal us, on that side – nothing but open plain. The place we must make for – the only safe one I can think of – lies the other way. You are sure you can control the mustang?”

“Quite sure,” was the prompt reply.

***

It was a straight unchanging chase across country – a trial of speed between the horses without riders, and the horses that were ridden. Speed alone could save the riders.

“Miss Poindexter!” the mustanger called out to the young lady. “You must ride on alone.”

“But why, sir?” asked she, bringing the mustang almost instantaneously to a stand.

“If we keep together we shall be overtaken. I must do something to stay those savage animals. For heaven’s sake don’t question me! Ten seconds of lost time, and it’ll be too late. Look ahead yonder. Do you see a pond? Ride straight towards it. You will find yourself between two high fences. They come together at the pond. You’ll see a gap, with bars. If I’m not up in time, gallop through, dismount, and put the bars up behind you.”

“And you, sir?”

“Have no fear for me! Alone, I shall run but little risk. For mercy’s sake, gallop forward! Keep the water under your eyes. Let it guide you. Remember to close the gap behind you.”

***

He overtook her on the shore of the pond. She was still seated in the saddle, relieved from all apprehension for his safety, and only trembling with a gratitude that longed to find expression in speech.

The peril was passed.

No longer in dread of any danger, the young Creole looked interrogatively around her.

“What is it for?” inquired the lady, indicating the construction.

Maurice explained to her that they were in a mustang trap – a contrivance for catching wild horses.

“The water attracts them; or they are driven towards it by a band of mustangers who follow, and force them on through the gap. Once within the corral, there is no trouble in taking them.”

“Poor things! Is it yours? You are a mustanger? You told us so?”

“I am; but I do not hunt the wild horse in this way. I prefer being alone. My weapon is this – the lazo.”

“I wish I could throw the lazo,” said the young Creole. “They tell me it is not a lady-like accomplishment.”

“Not lady-like! Surely it is as much so as skating? I know a lady who is very expert at it.”

“An American lady?”

“No; she’s Mexican, and lives on the Rio Grande; but sometimes comes across to the Leona – where she has relatives.”

“A young lady?”

“Yes. About your own age, I should think, Miss Poindexter.”

“Size?”

“Not so tall as you.”

“But much prettier, of course? The Mexican ladies, I’ve heard, in the matter of good looks, far surpass us plain Americans.”

“I think Creoles are not included in that category,” was the reply. “Perhaps you are anxious to get back to your party?” said Maurice, observing her abstracted air. “Your father may be alarmed by your long absence? Your brother – your cousin-”

“Ah, true!” she hurriedly rejoined, in a tone that betrayed pique. “I was not thinking of that. Thanks, sir, for reminding me of my duty. Let us go back!”

Again in the saddle, she gathered up her reins, and plied her tiny spur – both acts being performed with an air of reluctance, as if she would have preferred lingering a little longer in the “mustang trap.”

Answer the following questions:

1) Who organized the picnic? What entertainment was provided?

2) What happened in the prairie? Was Louise scared?

3) Who saved her and how?

4) What lady did Maurice tell Louise about?

Chapter Six

In the incipient city springing up under the protection of Fort Inge, the “hotel” was the most conspicuous building.

The hotel, or tavern, “Rough and Ready,” though differing but little from other Texan houses of entertainment, had some points in particular. Its proprietor was a German – in this part of the world, as elsewhere, found to be the best purveyors of food. Oberdoffer was the name he had imported with him from his fatherland; transformed by his Texan customers into “Old Duffer.”

There was one other peculiarity about the bar-room of the “Rough and Ready,” though it was not uncommon elsewhere. The building was shaped like a capital T; the bar-room representing the head of the letter. The counter extended along one side; while at each end was a door that opened outward into the public square of the city.

With the exception of the ladies, almost every one who had taken part in the expedition seemed to think that a half-hour spent at the “Rough and Ready” was necessary as a “nightcap”[23] before retiring to rest.

One of the groups assembled in the bar-room consisted of some eight or ten individuals, half of them in uniform. Among the latter were the three officers: the captain of infantry, and the two lieutenants.

Along with these was an officer older than any of them, also higher in authority. He was the commandant of the cantonment.

These gentlemen were conversing about the incidents of the day.

“Now tell us, major!” said lieutenant Hancock: “you must know. Where did the girl gallop to?”

“How should I know?” answered the officer appealed to. “Ask her cousin, Mr Cassius Calhoun.”

“We have asked him, but without getting any satisfaction. It’s clear he knows no more than we. He only met them on the return”

“Did you notice Calhoun as he came back?” inquired the captain of infantry.

“He did look rather unhappy,” replied the major; “but surely, Captain Sloman, you don’t attribute it to—?”

“Jealousy. I do, and nothing else.”

“What! of Maurice the mustanger? impossible – at least, very improbable.”

“And why, major?”

“My dear Sloman, Louise Poindexter is a lady, and Maurice Gerald—”

“May be a gentleman—”

“A trader in horses!” scornfully exclaimed Crossman; “the major is right – the thing’s impossible.”

“He’s an Irishman, major, this mustanger; and if he is what I have some reason to suspect—”

“Whatever he is,” interrupted the major, looking at the door, “he’s there to answer for himself.”

Silently advancing across the sanded floor, the mustanger had taken his stand at an unoccupied space in front of the counter.

“A glass of whisky and water, if you please?” was the modest request with which he saluted the landlord.

The officers were about to interrogate the mustanger – as the major had suggested – when the entrance of still another individual caused them to suspend their design.

The new-comer was Cassius Calhoun. In his presence it would scarce have been delicacy to investigate the subject any further.

It could be seen that the ex-officer of volunteers was under the influence of drink.

“Come, gentlemen!” cried he, addressing himself to the major’s party, at the same time stepping up to the counter; “Drinks all round. What say you?”

“Agreed – agreed!” replied several voices.

“You, major?”

“With pleasure, Captain Calhoun.”

The whole front of the long counter became occupied – with scarce an inch to spare.

Apparently by accident – though it may have been design on the part of Calhoun – he was the outermost man on the extreme right of those who had responded to his invitation.

This brought him in juxtaposition[24] with Maurice Gerald, who alone was quietly drinking his whisky and water, and smoking a cigar he had just lighted.

The two were back to back – neither having taken any notice of the other.

“A toast!” cried Calhoun, taking his glass from the counter. “America for the Americans, and confusion to all foreign interlopers – especially the damned Irish!”

On delivering the toast, he staggered back a pace; which brought his body in contact with that of the mustanger – at the moment standing with the glass raised to his lips. The collision caused the spilling of a portion of the whisky and water; which fell over the mustanger’s breast.

No one believed it was an accident – even for a moment.

Having deposited his glass upon the counter, the mustanger had drawn a silk handkerchief from his pocket, and was wiping from his shirt bosom the defilement of the spilt whisky.

In silence everybody awaited the development.

“I am an Irishman,” said the mustanger, as he returned his handkerchief to the place from which he had taken it.

“You?” scornfully retorted Calhoun, turning round. “You?” he continued, with his eye measuring the mustanger from head to foot, “you an Irishman? Great God, sir, I should never have thought so! I should have taken you for a Mexican, judging by your rig.”

“I can’t perceive how my rig should concern you, Mr Cassius Calhoun; and as you’ve done my shirt no service by spilling half my liquor upon it, I shall take the liberty of unstarching[25] yours in a similar fashion.”

So saying, the mustanger took up his glass; and, before Calhoun could get out of the way, the remains of the whisky were “swilled” into his face, sending him off into a fit of alternate sneezing and coughing that appeared to afford satisfaction to more than a majority of the bystanders.

All saw that the quarrel was a serious one. The affair must end in a fight. No power on earth could prevent it from coming to that conclusion.

On receiving the alcoholic douche, Calhoun had clutched his six-shooter,[26] and drawn it from its holster. He only waited to get the whisky out of his eyes before advancing upon his enemy.

The mustanger, anticipating this action, had armed himself with a similar weapon, and stood ready to return the fire of his antagonist – shot for shot.

“Hold!” commanded the major in a loud authoritative tone, interposing the long blade of his his sabre between the disputants.

“Hold your fire – I command you both. Drop your muzzles; or by the Almighty[27] I’ll take the arm off the first of you that touches trigger!”

“Why?” shouted Calhoun, purple with angry passion. “Why, Major Ringwood? After an insult like that, and from a low fellow—”

“You were the first to offer it, Captain Calhoun.”

“Damn me if I care! I shall be the last to let it pass unpunished. Stand out of the way, major.”

“I’m not the man to stand in the way of the honest adjustment of a quarrel,” answered the major. “You shall be quite at liberty – you and your antagonist – to kill one another, if it pleases you. But not just now. You must perceive, Mr Calhoun, that your sport endangers the lives of other people, who have not the slightest interest in it. Wait till the rest of us can withdraw to a safe distance.”

Calhoun stood, with sullen brow, gritting his teeth; while the mustanger appeared to take things as coolly as if neither angry, nor an Irishman.

“I suppose you are determined upon fighting?” said the major, knowing that, there was not much chance of adjusting the quarrel.

“I have no particular wish for it,” modestly responded Maurice. “If Mr Calhoun apologises for what he has said, and also what he has done—”

“He ought to do it: he began the quarrel!” suggested several of the bystanders.

“Never!” scornfully responded the ex-captain. “Cash Calhoun isn’t accustomed to that sort of thing. Apologise indeed! And to a masquerading monkey like that!”

“Enough!” cried the young Irishman, for the first time showing serious anger; “I gave him a chance for his life. He refuses to accept it: and now, by the Mother of God, we don’t both leave this room alive! Major! I insist that you and your friends withdraw. I can stand his insolence no longer!”

“Stay!” cried the major. “There should be some system about this. If they are to fight, let it be fair for both sides. Neither of you can object?”

“I shan’t object to anything that’s fair,” said the Irishman.

***

It was decided that Cassius Calhoun and Maurice Gerald would go outside along with everybody and then enter again – one at each door.

The duellists stood, each with eye intent upon the door, by which he was to make entrance – perhaps into eternity! They only waited for a signal to cross the threshold. It was to be given by ringing the tavern bell.

A loud voice was heard calling out the simple monosyllable—

“Ring!”

At the first dong of the bell both duellists had re-entered the room. A hundred eyes were upon them; and the spectators understood the conditions of the duel – that neither was to fire before crossing the threshold.

Once inside, the conflict commenced, the first shots filling the room with smoke. Both kept their feet, though both were wounded – their blood spurting out over the sanded floor.

The spectators outside saw only a cloud of smoke oozing out of both doors, and dimming the light of the lamps. There were heard shots – after the bell had become silent, other sounds: the sharp shivering of broken glass, the crash of falling furniture, rudely overturned in earnest struggle – the trampling of feet upon the boarded floor – at intervals the clear ringing crack of the revolvers; but neither of the voices of the men. The crowd in the street heard the confused noises, and noted the intervals of silence, without being exactly able to interpret them. The reports of the pistols[28] were all they had to proclaim the progress of the duel. Eleven had been counted; and in breathless silence they were listening for the twelfth.

Instead of it their ears were gratified by the sound of a voice, recognised as that of the mustanger.

“My pistol is at your head! I have one shot left – an apology, or you die!”

At the same instant was heard a different voice from the one which had already spoken. It was Calhoun’s – in low whining accents, almost a whisper. “Enough, damn it! Drop your shooting-iron – I apologise.”

Answer the following questions:

1) What were the officers talking about in the bar-room?

2) How did the conflict begin?

3) Did anybody try to prevent a duel?

4) Where did the duel take place?

5) How did it end?

Chapter Seven

After the duel Maurice was compelled to stay within doors. The injuries he had received, though not so severe as those of his antagonist, nevertheless made it necessary for him to keep to his chamber – a small, and scantily furnished bedroom in the hotel.

How the ex-captain carried his discomfiture no one could tell. He was no longer to be seen swaggering in the saloon of the “Rough and Ready;” though the cause of his absence was well understood. He was confined to his couch by wounds, that, if not skilfully treated, might lead to death.

He could no longer claim this credit in Texas; and the thought harrowed his heart to its very core. To figure as a defeated man before all the women of the settlement – above all in the eyes of her he adored, defeated by one whom he suspected of being his rival in her affections was too much to be endured with equanimity.

He had no idea of enduring it. If he could not escape from the disgrace, he was determined to revenge himself upon its author; and as soon as he had recovered from the apprehensions entertained about the safety of his life, he commenced reflecting upon this very subject.

In the solitude of his chamber he set about maturing his plans. Maurice, the mustanger, must die! He did not purpose doing the deed himself. His late defeat had rendered him fearful of chancing a second encounter with the same adversary. He wanted an accomplice – an arm to strike for him. Where was he to find it?

Unluckily he knew the very man. There was a Mexican at the time living in the village – like Maurice himself – a mustanger; but one of those with whom the young Irishman had shown a disinclination to associate. It was Miguel Diaz – known by the nickname “El Coyote.”

Calhoun remembered having met him in the bar-room of the hotel. He remembered that he had been one of those who had carried him home on the stretcher; and from some expressions he had made use of, when speaking of his antagonist, Calhoun had drawn the deduction, that the Mexican was no friend to Maurice the mustanger.

The Mexican made no secret of his heartfelt hostility to the young mustanger. He did not declare the exact cause of it; but Calhoun could guess, by certain innuendos introduced during the conversation, that it was the same as that by which he was himself actuated – the same to which may be traced almost every quarrel that has occurred among men, from Troy to Texas – a woman!

The Mexican did not give the name; and Calhoun, as he listened to his explanations, only hoped in his heart that the woman who had slighted him might have won the heart of his rival.

***

Louise was standing upon the edge of the azotea[29] that fronted towards the east. Her glance was wandering, as if her thoughts went not with it, but were dwelling upon some theme, neither present nor near.

In contrast with the cheerful brightness of the sky, there was a shadow upon her brow.

“He may be dangerously wounded – perhaps even to death? I may not send to inquire. I dare not even ask after him. He may be in some poor place – perhaps neglected? Would that I could convey to him a message without any one knowing it! I wonder what has become of Zeb Stump?”

The young lady scanned the road leading towards Fort Inge. Zeb Stump should come that way. He was not in sight; nor was any one else. She looked at the plain in the opposite quarter and saw a horse stepping out from among the trees. He was ridden by one, who, at first sight, appeared to be a man, dressed in a sort of Arab costume; but who, on closer scrutiny, was unquestionably of the other sex – a lady.

The loosely falling folds of the lady’s scarf didn’t hinder the observer from coming to the conclusion, that her figure was quite as attractive as her face.

The man following upon the mule by his costume – as well as the respectful distance observed – was evidently an attendant.

“Who can that woman be?” was the muttered interrogatory of Louise Poindexter, as with quick action she raised the lorgnette to her eyes. “A Mexican, of course; the man on the mule her servant. Some grand senora, I suppose? A basket carried by the attendant. I wonder what it contains; and what errand she can have to the Port – it may be the village. It is the third time I’ve seen her passing within this week? She must be from some of the plantations below!”

There came a change over the countenance of the Creole, quick as a drifting cloud darkens the disc of the sun.

The cause could only be looked for in the movements of the scarfed equestrian on the other side of the river. An antelope had sprung up, out of some low shrubbery growing by the roadside. The woman with her scarf suddenly flung from her face, was seen describing, with her right arm, a series of circular sweeps in the air!

“What is the woman going to do?” was the muttered interrogatory of the spectator upon the house-top. “Ha! As I live, it is a lazo!”

The senora was not long in giving proof of skill in the use of the lazo – by flinging its noose around the antelope’s neck, and throwing the creature in its tracks!

It was at that moment – when the lazo was seen circling in the air – that the shadow had reappeared upon the countenance or the Creole. It was not surprise that caused it, but a thought far more unpleasant.

“I wonder – oh, I wonder if it is she! My own age, he said – not quite so tall. The description suits – so far as one may judge at this distance. Has her home on the Rio Grande. Comes occasionally to the Leona, to visit some relatives. Why did I not ask him the name? I wonder – oh, I wonder if it is she!”

It was a relief to Louise Poindexter, when a horseman appeared coming out of the chapparal;[30] a still greater relief, when he was recognised, through the lorgnette, as Zeb Stump the hunter.

“The man I was wanting to see!” she exclaimed in joyous accents. “He can bear me a message; and perhaps tell who she is. He must have met her on the road.”

“Dear Mr Stump!” called a voice, to which the old hunter delighted to listen. “I’m so glad to see you. Dismount, and come up here!”

Zeb was soon upon the housetop; where he was once more welcomed by the young mistress of the mansion.

She asked him about Maurice, and Zeb told her that the mustanger didn’t have any dangerous wounds and would be all right in a couple of days. When Louise learned that after the duel Maurice was staying at the hotel she said she wished to send something to him.

“Stay here, Mr Stump, till I come up to you again.”

The young lady lightly descended the stone stairway. Presently she reappeared – bringing with her a good-sized hamper; which was evidently filled with eatables.

“Now dear old Zeb, you will take this to Mr Gerald? It’s only some little things that Florinda has put up, such as sick people at times have a craving for. They are not likely to be kept in the hotel. Don’t tell him where they come from – neither him, nor any one else.”

“You may depend on Zeb Stump for that, Miss Louise. Though, for the matter of cakes and kickshaws, and all that sort of thing, the mustanger hasn’t had much reason to complain. He has been supplied with enough of them.”

“Supplied already! By whom?”

“Well, I can’t inform you, Miss Louise; Maurice doesn’t know it himself. I only heard they were fetched to the tavern in baskets, by some sort of a serving-man, a Mexican. I’ve seen the man myself. Fact, I’ve just this minute met him, riding after a woman. He had a basket just like one Maurice had got already.”

There was no need to trouble Zeb Stump with further cross-questioning. A whole history was supplied by that single speech. The case was painfully clear. In the regard of Maurice Gerald, Louise Poindexter had a rival – perhaps something more. The lady of the lazo was either his fiancée, or his mistress!

For the first time in her life Louise Poindexter felt the pangs of jealousy. It was her first real love: for she was in love with Maurice Gerald.

The mistress of Casa del Corvo could not rest, till she had satisfied herself on this score. As soon as Zeb Stump had taken his departure, she ordered the spotted mare to be saddled; and, riding out alone, she sought the crossing of the river; and thence proceeded to the highway on the opposite side.

Advancing in the direction of the Fort, as she expected, she soon encountered the Mexican senora on her return; no senora according to the exact signification of the term, but a senorita – a young lady, not older than herself.

Good breeding permitted only a glance at her in passing; which was returned by a like courtesy on the part of the stranger.

“Beautiful!” said Louise, after passing her supposed rival upon the road. “Yes; too beautiful to be his friend! I cannot have any doubt,” continued she, “of the relationship that exists between them – He loves her! – he loves her! It accounts for his cold indifference to me?

Answer the following questions:

1) How did Calhoun feel after his defeat? What plan was he maturing?

2) Who is Miguel Diaz? Why did he dislike Maurice Gerald?

3) Where did Maurice stay after the duel? Who supplied him with delicacies?

4) How did Louise feel after she’d learned who it was? Why?

Chapter Eight

During the three days that followed that unpleasant discovery, once again had she seen – from the housetop as before – the lady of the lazo, as before accompanied by her attendant with the basket.

She knew more now about her rival, though not much. The Dona Isidora Covarubio de los Llanos – daughter of a wealthy landowner, who lived upon the Rio Grande, and niece to another whose estate lay upon the Leona, a mile beyond the boundaries of her father’s new purchase. An eccentric young lady, as some thought, who could throw a lazo, tame a wild steed, or anything else excepting her own caprices.

One day Louise was upon the azotea, looking towards the quarter whence the senorita might have been expected to come.

On turning her eyes in the opposite direction, she beheld – that which caused her something more than surprise. She saw Maurice Gerald, mounted on horseback, and riding down the road!

On recognising him, she shrank behind the parapet.

The invalid was convalescent. He no longer needed to be visited by his nurse.

Cowering behind the parapet Louise Poindexter watched the passing horseman. She felt some slight gratification on observing that he turned his face at intervals and fixed his regard upon Casa del Corvo. It was increased, when on reaching a copse, that stood by the side of the road, and nearly opposite the house, he reined up behind the trees, and for a long time remained in the same spot, as if reconnoitring the mansion.

Then he rode on and became lost to view with the road upon which he was riding.

Where was he going? To visit Dona Isidora Covarubio de los Llanos?

***

As on the day before, Louise stood by the parapet scanning the road on the opposite side of the river; as before, she saw the mustanger ride past.

He was going downwards, as on the day preceding. Her heart fluttered between hope and fear. There was an instant when she felt half inclined to show herself. Fear prevailed; and in the next instant he was gone.

The jealous heart of the Creole could hold out no longer. In less than twenty minutes after, a steed was seen upon the same road – and in the same direction – with a lady upon its back.

She entered the chapparal where the mustanger had ridden in scarce twenty minutes before. She reached the crest of a hill which commanded a view beyond. There was a mansion in sight surrounded by tall trees. It was the residence of Don Silvio Martinez, the uncle of Dona Isidora. So much had she learnt already.

No one appeared either at the house, or near it.

Could the lady have ridden out to meet him, or Maurice gone in?

With such questions was the Creole afflicting herself, when the neigh of a horse broke abruptly on her ear. She looked below: for she had halted upon the crest, a steep acclivity. The mustanger was ascending it – riding directly towards her.

It was too late for Louise to shun him. The spotted mustang had replied to the salutation of an old acquaintance. Its rider was constrained to keep her ground, till the mustanger came up.