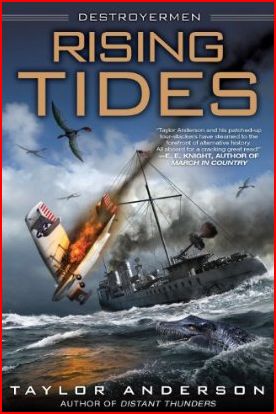

Rising Tides

Taylor Anderson

CHAPTER 1

The atmosphere in the wardroom of the old Asiatic Fleet “four-stacker” destroyer USS Walker (DD-163) was no longer animated; it was more… subdued and sickened than anything else. The sultry, rotting breeze off the unknown atoll to windward entered the portholes and swirled in the cramped compartment, resuscitating an all-pervading aroma of mildew and sweat. beings sat stiffly, tiredly, uncomfortably behind the green linoleum-topped wardroom table, facing aft, waiting for the final prisoner to be brought before them. It had been a long day, in many ways, and the fiery, righteous passions that had inflamed the earlier proceedings had finally dwindled to mere disgusted embers of their former selves. The aversion, horror, and anger the “court” felt toward the prisoners they’d judged was still very real and palpable, but it had become an exhausted, mechanical thing by now, and everyone-the judges, prosecutors, and even the defense-just wanted the whole thing over at last.

Captain Matthew Reddy, High Chief of the American Clan, and Commander in Chief (by acclamation) of all Allied Forces united under the Banner of the Trees, stared through the porthole at battered Achilles, anchored alongside. They’d nearly lost the Imperial steam frigate to damage sustained in the battle against the “Company” ships. She’d suffered even more sorely in a vicious little storm that brewed up shortly after, before they made this unexpected landfall that afforded some protection while she and the rest of the little fleet performed emergency repairs. Now the two “prizes” that Achilles and Walker had taken intact-the HNBC (Honorable New Britain Company) flagship Ulysses and the pressed Imperial frigate Icarus -were already practically ready for sea. Ulysses had fled the action and been only lightly damaged, and Icarus had been wrested from her Company commanders by loyal sailors and hadn’t participated in the fight. Achilles was mauled by HNBC Caesar, but ultimately sent her to the bottom. Even Walker, with her comparatively long-range guns, had taken a beating, and throughout the court sessions her old iron hull had reverberated with the sound of clanging blows from inside and out, as punctured plates were replaced (they could do that now, at least) or heated, bent back in place, and reriveted.

Walker wasn’t new anymore by any possible definition, but after her resurrection and rebuilding, she’d at least looked almost new for a while in her fresh, darker shade of gray that the Bosun finally approved. Her appearance had certainly been a far cry from the shattered, half-sunken wreck she’d been after the Battle of Baalkpan. Herculean work had been accomplished to return her to duty and, ultimately, to ready her for this particular mission. It was really a miracle that she’d ever floated again, much less steamed so far, fought yet another battle, and arrived safely at this place. Sometimes, when Matt gazed at her, he had difficulty believing she had.

Neither Matt nor the Bosun had participated in her refloating and rebuilding; they’d both been off aboard Donaghey, leading the Singapore Campaign. They hadn’t witnessed the unending hours of wrenching labor, ingenuity, and tireless dedication that resulted in her gradual but almost complete restoration. They’d returned home from the war in the west prepared to embark on literally anything available to chase the Company criminal Walter Billingsley, who’d abducted Princess Rebecca, Sandra Tucker, Sister Audry, Dennis Silva, and Abel Cook. Kidnapping the princess was bad enough. She and her “lizard” friend Lawrence-who’d also been taken-were heroes of the Alliance and the Lemurians held them to their hearts. But Sandra’s abduction was even worse, if that was possible. Not only was she a much-beloved heroine who’d saved literally thousands of lives with her own hands and her medical and organizational skill, she was the woman Matthew Reddy loved. They weren’t married or even officially engaged, but that made no difference to the Lemurian “ ’Cats.” To them, she was their Supreme Commander’s “mate.” Nothing, not even the all-important war, could or should interfere with his pursuit of her captors.

There was genuine concern for the other hostages too. Sister Audry had few detractors, despite her heretical teachings. Quite a number had even converted to her church. She was considered by all to be an honest, pious female, if just a bit odd. Abel Cook wasn’t well-known, but he was “one of theirs.” Dennis Silva was a genuine hero, and though unqualifiedly deranged, he’d almost come to symbolize the human Americans in some indefinable way as far as the Lemurians were concerned. He was big, noisy, and irreverent, but in an almost childlike, inoffensive manner. He was brave to the point of recklessness, but tender with younglings. He’d sacrificed much for a people and cause he barely knew, simply because it was right -and he was capable of unparalleled violence toward anything that posed a threat to his new friends. His ongoing affairs with human nurse Pam Cross, as well as the equally rambunctious Lemurian Risa-Sab-At, were also a source of much gossip and amusement among the Allied ’Cats, even though-and perhaps because-the affair seemed to cause such consternation among his “own” people.

For whatever reason, the Lemurians wanted all “their people” back, and therefore, somehow, they and a smattering of Matt’s own destroyermen, who’d been left in charge of salvaging his ship, not only did so but had her ready for him when he needed her most. Matt rubbed his eyes. It had been a miracle, sure enough. But he’d almost begun to expect miracles where the Lemurians and his destroyermen-all his People-were concerned.

He shook his head. Time to get back to business. Despite his misgivings, he’d agreed to serve as President of the Court at Commodore Jenks’s request. His ship had been attacked without warning and he knew he couldn’t be entirely objective, but Jenks had argued that his was the only ship without either a Company or an Imperial Navy presence aboard. Since all the Company and Imperial Navy crews and officers were potential defendants, prosecutors, or witnesses to the primary charge of “Knowingly and Deliberately Attempting the Foul Murder of Princess Rebecca Anne McDonald,” heir to the Governor-Emperor’s throne, in the false certainty that she was aboard Matt’s ship, the trial would conclude if the accused were guilty of high treason, not a deliberate act of war against a sovereign state-or USS Walker. Attacking Walker was merely the means by which they’d demonstrated their treason. Matt’s crew was aggrieved that the guilty wouldn’t hang for murdering the shipmates that had been lost, but as long as they hung for something, the crew was partially mollified.

Again, because they’d agreed that no Imperial personnel should sit on the court, Matt had been forced to choose the other two judges himself. On the surface, Bosun’s Mate 2nd (and Captain of Marines) Chack-Sab-At was an easy choice. The young Lemurian’s honor and integrity were beyond question, as were his physical courage and sense of justice. Of all the ’Cats Matt had come to know, Chack was, in many ways, the most remarkable. He’d literally been a pacifist before the war against the Grik, but he’d since become a consummate, skilled, and resourceful… Marine. He always reverted to his “old” status of bosun’s mate aboard Walker, the ship he now fully considered his Home, but he’d become much, much more.

That was part of the problem. The young Lemurian, once able to take such innocent and childlike joy from the grand adventure of life, had become a virtual killing machine. Fighting the Grik was one thing, however. He’d been able to keep that separate, apart. He’d built a wall between his soul and the things he’d done to save his people. The battle they’d been forced to fight against other humans had apparently loosened a few of the stones in that wall. He clearly didn’t understand it, and he was confused. Lemurians simply didn’t fight other Lemurians-with a few notable exceptions. He’d known and accepted from the start that humans did fight other humans, and he’d even helped fight the Japanese humans who aided the Grik. But These humans, these “Imperials,” were the very descendants of the ancient “tail-less ones” who once came among his people and gave them so much in terms of technology, culture, and even knowledge of the Heavens. Essentially, Matt supposed Chack felt as if he’d met the ancient saints of his people and discovered they weren’t saints after all.

Matt knew Chack’s feelings weren’t unique. The very voyage they were embarked on had done much to undermine some fundamental tenets of Lemurian dogma. Even the fact that they’d traveled this far without falling off the world had been sufficient to do that to a degree. Lemurians knew the world was round, but apparently only those now aboard USS Walker really understood the simple truth that gravity pulled down, no matter where you went. This didn’t come as a basic physics lesson to Walker ’s now predominantly Lemurian crew; it challenged many fundamental “laws of things” as far as they were concerned, including such mundane things as where the water came from that fell as rain from the Heavens.

Chack-and all his people, ultimately-had a lot of stuff to sort out, and as essential as it had become for them to enter the “modern world,” Matt felt a profound sadness as he watched Chack’s and the Lemurian people’s… innocence… drain away.

The third member of the tribunal had been a slightly controversial selection. Courtney Bradford had been a civilian employee of Royal Dutch Shell before the strange Squall brought them to this world. An Australian, he’d been a petroleum engineer and self-styled naturalist. Quirky and brilliant, the man was also a moderately reliable pain in the ass in an unintentional, exuberantly oblivious sort of way. Despite his personality, Matt considered him an obvious choice for the assignment because not only was he Minister of Science of the Allied powers; he also enjoyed the dubious and well-deserved, if slightly nerve-racking, title of Plenipotentiary at Large.

Matt had been genuinely surprised when Commodore Jenks himself raised an objection to Courtney’s appointment on the grounds that this was to be a military trial and no civilian could sit in judgment of a military man. Matt countered with a simple question: “How many navies does the Empire have?” Jenks had been flustered, as if the question had never occurred to him before. Perhaps it hadn’t. He finally, thoughtfully, admitted there was only one Imperial Navy, and “Company” ships weren’t part of it. That being established, he readily, almost eagerly, agreed that it was perfectly appropriate for a civilian to sit in judgment over what were, ultimately, civilian pirates. As prosecutors, Jenks and his exec, Lieutenant Grimsley, had pursued and stressed the treasonous pirate theme throughout the trial, and Matt suspected they were practicing an argument that Jenks intended to lay before the Lord High Admiral of the Imperial Navy in regard to the actions of the “Honorable” New Britain Company as a whole.

Matt’s own exec, Francis “Frankie” Steele, reluctantly but competently presided over the defense, with Lieutenant Blair of the Imperial Marines to assist him. Despite their reservations, both men took their duties seriously and were scrupulously, almost torturously fair, but the preponderance of the evidence and the vast numbers of witnesses for the prosecution left them relying almost entirely on “reasonable doubt,” which was recognized by the Empire. Unfortunately for most of their “clients,” there wasn’t any doubt at all.

The trials were finally over, and this day had been dedicated to summoning the prisoners to hear their fate. A total of fifty-one HNBC officers and Company officials had been charged and tried. Of those, thirty-one had been found guilty of the capital crime they were accused of. According to the Imperial trial procedures and Articles of War that Matt had agreed were appropriate under the circumstances, there was only one possible sentence for them: death by hanging. Even now, the condemned men were being ferried across and hoisted, one at a time, to the tip of the main yard of Ulysses. Thirteen were guilty of arguably lesser crimes, for which they would be imprisoned at the first Imperial settlement they reached. Six were actually found not guilty of anything, as far as even Jenks could tell, other than being Company toadies who’d mistreated the naval personnel placed under their authority. They hadn’t had any idea what the true nature of their mission was.

Still staring at Achilles through the porthole, Matt was glad Ulysses was out of sight. He had no concern that they might be hanging innocent men, but he’d seen so much death in all its forms over the last couple of years, the cold-blooded, methodical hanging of men was not a mental image he needed to add to the album of his troubled dreams. Not while he was attempting to remain as objective as possible and trying very hard not to hate the Empire as a whole for what some of its people had done. Not while he thought he might enjoy the hangings a little too much… He glanced at the other “judges” beside him and sighed.

“Let’s get this over with,” he murmured quietly.

“Forgive me, Captain Reddy… Captain Chack. You as well, Mr. Bradford,” Jenks said apologetically. “I knew I was asking a lot of you. Of you all. But this… process… was utterly necessary, I’m afraid. We still have a long voyage ahead, and an unknown situation awaiting us when we arrive. We haven’t caught up with Ajax and Commander Billingsley, nor had any of the ships we fought sighted or spoken them. With this delay to make repairs and the delay we must endure a little farther along while we await your replenishment squadron, I fear we may not catch Billingsley at all. We must assume he will reach New Britain, or one of the other main islands before us, and we must be prepared to counter his version of events. That assumes, of course, that he makes his presence known when he arrives. We have no conception of his agenda or how the Company means to use its possession of the princess-not to mention the other hostages. Taking the princess will have been bad enough, once known, but taking the other hostages, your people-” He stopped, knowing full well one of those “people” was the woman Matt loved. “That has made this an international incident,” he ended at last.

“It was an act of war!” Matt reminded him. “Besides the hostages he took, he destroyed Allied property and killed people when he did it!”

“Rest assured, Captain Reddy, I shan’t forget. It will be our business, yours and mine, to convince the proper people-hopefully the Governor-Emperor himself-just how significant an act that was, not only from the perspective of avoiding conflict between our peoples, but how that might affect our future cooperation against the Grik.” He frowned. “Trust me in this-having seen and fought those vicious buggers, I’m quite a fervent convert to your assertion that they pose a monstrous threat not only to our way of life but to all life on this world.” He gestured around at the compartment and, by implication, the proceedings underway. “This unpleasant business will have been expected of us, and not to put too fine a point upon it, many of these traitorous scum will actually escape the hangman if the Company is allowed to take a hand. In that case, not only will justice never be served, but we might find ourselves in the dock facing a-I believe you call it a ‘stacked deck.’ If we hope to accomplish anything when we reach New Britain, ours must be the official, legal, indisputable account of the events that have transpired.”

There came a knock on the passageway bulkhead beyond the beautifully embroidered curtain that had replaced the vile, stained pea green curtain that had hung there when Matt first took command of USS Walker a lifetime ago. The new curtain was still green so as not to clash with the cracked and bulging green linoleum tiles on the deck, but some Lemurian artist had lovingly embroidered the U.S. Navy seal and “USS Walker, DD-163” in gold and colored thread. The thing was beautiful, and in stark contrast to the spartan interior of the wardroom.

“Enter,” said Matt after a slight hesitation.

Juan Marcos, the bold, inscrutable little Filipino steward who had, by force of will alone, established himself as Matt’s personal steward/ butler/secretary, moved the curtain aside with a grim expression. The final prisoner to come before them was none other than the captain of Ulysses, the flagship of the Company squadron that had attacked them and then fled so ignominiously in the face of Walker ’s vengeful salvos. As flagship, Ulysses carried the greatest weight of metal and the most powerful guns. She had most likely been the ship that fired those first unexpected broadsides that damaged Matt’s ship and killed several of her crew. The Company captain’s later protestations of innocence and remorse only added to the contempt in which Walker ’s crew held him. He was a murderer and a coward. Currently, only his cowardice was on display. When the ’Cat Marines practically carried him into the compartment and he saw his own sword laid upon the table, its point arranged in his direction, he already knew the verdict and began to blubber. Any sympathy Matt might have felt toward the man evaporated, and his voice was harsh when he spoke.

“Captain Moline, it is the judgment of this court that you are not a naval officer and are therefore not subject to punishment for certain infractions of the Imperial Articles of War of which you have been accused-even though it’s my understanding you did swear, upon receiving your HNBC commission, that you’d abide by those articles. That being the case, this court has no choice but to find you not guilty of the crimes specified under articles two, three, four, twelve, thireen, fifteen, seventeen, eighteen, nineteen, and twenty-seven of which you’ve been charged.”

Matt had never considered himself a cruel man, but he couldn’t stop himself from pausing, ever so slightly. Just long enough to see the first rays of hope begin to bloom in Captain Moline’s eyes. He abruptly continued, in the same harsh tone.

“However, even as a civilian, you’re still subject to certain specifications within those military articles, and of course you’re entirely subject to numerous civil charges as they exist for the protection and punishment of non-military subjects of Imperial law. No provincial Assize court or Home Circuit being in the vicinity, it’s my understanding that, according to Imperial law, this court must assume the duties normally prescribed for them. If you were being tried by a civil court, you’d certainly face at least the charges of high treason against your sovereign and nation, piracy, and attempted murder of a member of the Imperial family. I could add other charges, but there’d be no point. Any of these are capital crimes, and this court finds you guilty of all specifications.”

“But…” Moline floundered desperately. “I was following orders! The orders of a representative of the Prime Proprietor’s personal factor!”

Matt paused and took an exasperated breath. He glanced at his notes. “Yes. You testified that a ‘Mr. Brown’ presented you with sealed orders that were to be opened in the event you sighted this ship-a ‘dedicated steamer with four funnels,’ you said. You also said these orders directed you to lure the described steamer as close as possible and destroy it without warning.”

“Despicable orders, but orders nevertheless!” pleaded Moline.

Matt continued relentlessly. “Orders you did not question? Commodore Jenks assures me that even masters of Company vessels are free… are required to question orders they consider criminal or immoral-it’s in your charter!”

“Much of what is in the charter has no meaning now,” Moline moaned. “Questioning orders is no longer encouraged or even allowed!”

“The charter reflects Imperial law. It does not supersede it!” Jenks accused. “Neither do the orders of rogue Company officials! Regardless of what the Company might or might not encourage or allow, you are still subject to Imperial law!”

Moline looked at Jenks and his eyes grew dull. “You have been gone a long time, Commodore. Who are you to say what supersedes what?”

Jenks jumped to his feet. “Honor supersedes treachery!” he practically shouted. “Duty to the Governor-Emperor supersedes any conceivable ‘duty’ to a Company… creature… in the office of the Prime Proprietor!” With a visible force of will, he composed himself. When he continued, his voice was dry and emotionless.

“If your ‘Mr. Brown’ had not been so conveniently killed in the exchange of shot with this ship, perhaps some of what you say might be verified and your own guilt mitigated to a slight degree, but not enough to save you from a rope.” He glanced at his own notes. “You testified that these ‘sealed orders’ were destroyed as soon as you were acquainted with them, so clearly even ‘Mr. Brown’ recognized their criminal nature. It has been established by numerous witnesses that Ensign Parr, whom I dispatched aboard Agamemnon, duly reported to the first authorities he met-Company officials!-the survival and rescue of the princess, as well as her intention to take passage on this ship. Numerous witnesses-virtually Agamemnon ’s entire original crew!-also report that they were transferred and sequestered aboard Icarus, a less powerful and capable ship, before they could report to any naval or Imperial authorities. Finally, both Icarus and Agamemnon were pressed into Company service! Imperial Navy ships and crews were illegally seized by, and placed into the service of, Company pirates bent on committing high treason! Regardless of any ‘sealed orders,’ these acts were no secret to you. That you continued in command of Ulysses is abundant proof that you made no objection to these other crimes at least, and obviously made no attempt to thwart them! Even if you are as utterly stupid as you would have us believe, you are at the very least guilty of being an accessory to a blatant act of piracy!”

Jenks paused, catching himself. His voice had begun to rise again and his fury toward not only Captain Moline but the HNBC itself threatened to overwhelm him. Matt suspected Jenks’s emotions were stirred by terror as well: not physical terror-he knew Jenks was no coward-but a growing terror of what they might discover his precious Empire had become in his absence. Matt could identify with that kind of terror: he felt it at the edge of his consciousness every moment of every day. He somehow managed to function and perform his duties-he had no choice-but he was genuinely terrified for the safety of one Nurse Lieutenant Sandra Tucker, who even now was still in the maniacal hands of the Company minion, Walter Billingsley… as far as they knew.

Matt cleared his throat. “Further demonstrations, protestations, or even admonitions are pointless at this stage. As previously stated, Captain Moline, you’ve been found guilty of the crimes described by Commodore Jenks. It is therefore the order of this court that you be taken from this place to the deck of the pirate prize Ulysses, where, according to the customs of your service, you will be bound hand and foot and hanged by the neck until you’re dead.” Matt glanced from the frozen form of the prisoner to the two Marines. “Get this bastard out of my sight.”

Brad “Spanky” McFarlane scrutinized the toil underway in the crew’s forward berthing space with a critical but generally satisfied eye. Standing in the steamy compartment where hardly anyone ever actually slept, he struck his trademark pose-hands on his skinny hips, his absolute authority over everything in his domain radiating from his diminutive but powerfully wiry frame. Before him, a party of’Cats adjusted shoring timbers while two men held torches against a warped steel plate, heating it to a dull reddish orange. Radiant heat from the torches and the steel they played against only added to the stifling temperature of the berthing space, even with the portholes open. Absently, Spanky wondered again what kind of idiot designed this ship and so many like her with the portholes in the forward berthing space so close to the waterline that they could almost never be opened-at least not in any kind of sea, or while the ship was underway. If it hadn’t been for the meager light they provided in daytime, he probably would’ve plated over them during the reconstruction.

Periodically, the smoking timbers were pounded against the plate, pushing it a little closer to where it had been before the large roundshot bent it inward. It was the last one; all the others that had been displaced nearby had already been reformed. The racket of the sledges against the timbers in the confined space was terrific.

“Almost there, Lieuten-aant McFaar-lane,” cried a ’Cat between blows. Spanky nodded. He was far more than a mere lieutenant now, he was “Minister of Naval Engineering,” or something like that, but he didn’t care. Usually he couldn’t even remember whether his “official” Navy rank was lieutenant commander or commander, but it couldn’t have mattered less to him. Nobody would try to tell him what to do when it came to his area of expertise, and right now, aboard USS Walker, doing what he was doing, he was the ship’s engineering lieutenant, and that was it. As far as he could recollect, he and the Skipper were the only officers currently on the ship still performing their “old jobs.”

Spanky and Chief Bosun’s Mate Carl Bashear were inspecting the final touches on the repairs to Walker ’s hull. They’d already fixed several similar perforations acquired during the sharp action with the Company traitors. The hole that opened up the forward engine room had been the worst, not only puncturing the hull-right at a frame-but also knocking a double hole through one of the saddle bunkers. They’d salvaged most of the fuel, pumping it into bunkers they’d already run dry. They even saved most of what leaked into the bilge, just in case, but fixing that damage had been their most critical and difficult repair. They had found the roundshot that made the holes-and nearly took Brian Aubrey’s head off-rolling around in the bilge. Jenks identified it as a thirty-pounder. This struck everyone odd, since the Grand Alliance had sort of based its shot sizes on the old British system, and its closest equivalent was a thirty-two-pounder. The Brits themselves seemed to have abandoned the very system they brought with them-or adopted another. Oh, well, that wasn’t Spanky’s concern beyond the proof it provided concerning who’d shot it into them. Ulysses carried thirty-pounders. Even now, unless he missed his guess, her skipper was swinging for it.

“Nice to be able to fix something right for a change,” Bashear rumbled. It was a positive statement, but still came out with a tone of complaint.

“Yeah. Havin’ enough guys for a job makes a difference-not to mention havin’ somethin’ to do it with.”

Their labor pool and equipment list were far better than they’d ever been when they’d attempted similar repairs in the past; they had spare plate steel, rivets, and plenty of acetylene-even if it popped and sputtered-and Walker ’s crew was actually somewhat over complement for a change too. Almost two-thirds of that crew was Lemurian now, but they took up less space and more would fit. Many were Chack’s Marines, who had shipboard duties as well. Spanky was generally satisfied with the growing professionalism and competency of all their “new” ’Cats, and he’d long been pleased with the “old hands,” who’d signed on as cadets when Walker first dropped anchor in Baalkpan Bay, but there was just no way he’d ever get used to certain aspects of this new navy they’d created.

He sneezed. Lemurians sweated more like horses than men, kind of “lathering up.” They also panted. Bradford said they’d developed this somewhat unique method of heat exchange due to their environment. They also shed like crazy, and Spanky was allergic to the downy filaments that floated everywhere belowdecks when they were hard at work.

“C’mon, Carl,” he said. “These apes and snipes are working together so well it turns my stomach.” There were grins at that. “I don’t think we need to keep starin’ at them to keep them away from each other’s throats.”

“I just don’t understand it,” Bashear commiserated. “Whatever happened to tradition? Where’s the pride? You’d almost think they like each other, to look at ’em get on so. Ain’t natural.”

Spanky chuckled. The old rivalry between the deck (apes) and engineering (snipes) divisions still existed, but it had been “tamed down” a little without the caustic presence of Dean Laney aboard. He’d been of the “old school,” in which duties were strictly defined in an almost labor union-like fashion. The Bosun wasn’t much different, but he’d adjusted to the new imperatives. Laney hadn’t. It hadn’t been so bad when Chief Donaghey had ridden herd on the man, but after Donaghey’s death, Laney became a tyrant. There just wasn’t room for that on something as small as Walker anymore. On this mission, Laney had remained behind to supervise the production of heavy industry-something his obnoxious personality was well suited for. And besides, the running-mostly-joke was that if somebody “accidentally” dropped something big and heavy on him, the world would be a better place.

In the meantime, the Lemurian apes and snipes on Walker got along much better. None of the ’Cats liked the Imperial term “Ape Folk,” even if, as far as anyone knew, they’d never seen an ape; they understood it was derogatory and condescending. In contrast, the “deck apes” didn’t mind that term at all. It was occupational… and almost fraternal. They embraced it just as the engineering divisions accepted the title of “snipes” in much the same way. There were still pranks and jokes, and a competitive spirit existed between them, but they’d all been through far too much together to lose sight of the fact that they were all on the same side, part of the same clan, living on the same Home. Spanky, who’d had a little college before joining the Navy as a mere recruit and rising as a “mustang,” was reminded of guys from different college fraternities who played on the same football team. In spite of his remarks to Carl Bashear-remarks expected of him-he liked it this way.

“Where’re we goin’?” Bashear asked as they left the repair detail to their work and moved aft.

“Something I gotta do, then I’ll go topside with you and have a look at that winch. You say it ain’t blowin’ steam?”

Carl shook his head. “Nope. Nothin’ blows steam around here ’cept the fellas now and then.” He shook his head. “That ain’t natural either. That gasket stuff Letts came up with works almost too good. No, there’s something else, and I gotta get it fixed. The Skipper wants Mr. Reynolds to fly tomorrow, or the next day, when we get underway.” He pointed in the general direction of land. “According to our charts, that thing’s not even supposed to be there. The Brit charts don’t show it either, for that matter, but they do show a lot of stuff a little farther along that ain’t right.” Bashear scratched his head. “So far, west of here, everything seems about the same. Nothing too out of the ordinary that different sea levels wouldn’t account for, other than the occasional volcanic island that ain’t where it’s supposed to be. What’s the deal with these atolls and stuff?”

Spanky shrugged. “Ask Mr. Bradford. He knows all that stuff. From what I gather though, these pissant desert islands and atolls pile up on old coral reefs or something. Kind of random. No reason they had to show up the same place they were ‘back home,’ since there was no real reason them other ones formed where they did. Just luck that the first coral pod-or whatever they are-took root where it did. The islands are in the same basic area, but no reason they should be exactly the same either.”

Bashear looked at him skeptically. “Well, either way, the Skipper wants Reynolds to fly.” He chuckled. “Now that he’s fixed all the holes in his plane. You heard one of the holes was ‘self-inflicted’?”

“I heard,” said Spanky, “and you ought to cut the kid some slack. Most of the holes weren’t self-inflicted and there were a lot of’em. All he had to shoot back with was a pistol, for Crissakes. So he got a little fixated on his target. Happens all the time. Just think how many observers prob’ly shot their own planes to pieces back in the Great War.” He grinned. “Think how many times those battlewagon boys blew their own observation planes over the side just in exercises, before the war! You get ’em in a real fight, they’d probably blast their own damn ship!”

“Well, any way,” Bashear continued as they worked their way aft, “Skipper wants him to chart shoals and such from the air so we’ll know if we can ever get something big through here, like a ’Cat flattop. I can’t lift the plane without the winch.”

“Right,” Spanky replied, and left it at that. Reynolds had taken a lot of ribbing for shooting his own plane, but the kid had guts. Once he’d finally decided what to do with himself, he’d become a good pilot for one of the tiny, rickety-looking “Nancys,” or prototype seaplanes Ben Mallory had designed. Spanky wouldn’t have gone up in one of the things, and he respected anyone willing to do something he wouldn’t.

Together, he and Bashear cycled through the air lock into the forward fireroom. ’Cats looked up as they passed, nodding respectfully but remaining at their posts. The number two boiler was lit. Cycling through to the aft fireroom was almost like passing through another Squall to a different world all over again. In contrast to the peaceful routine they’d just left, the aft fireroom was a scene of chittering excitement, shouted commands, and almost frantic activity. Black soot floated in the air along with the downy filaments of Lemurian undercoats. Spanky sneezed again and blew his nose into his fingers. He no longer slung the snot at the deck plates as he once had, but wiped his fingers on a rag hanging from his pocket. Somehow, slinging snot at Walker just didn’t seem right anymore.

“Tabby!” He had to shout to be heard over the commotion in the fireroom.

Tab-At, or “Tabby” as the original “Mice” (a pair of extraordinarily insular and unusual firemen who actually looked quite a bit like small rodents) had christened her before she became one of the Mice herself, looked up from where she stood, striking a pose similar to the one Spanky himself often used. Her hands rested on admittedly shapelier, disconcertingly feminine hips, even though she belonged to an entirely different species. The tail that twitched beneath her abbreviated kilt at Spanky’s shout undermined the image to some degree, but oddly, not too much. As usual, whenever Spanky encountered her, she wasn’t wearing a shirt either. This time at least, she probably hadn’t been doing it just to get his goat, since her silky gray fur was lathered with sweat and covered with soot. Even so, Spanky had to take a deep breath and force himself not to bellow at her for being out of “uniform” once again. Her beguilingly… human… well-rounded breasts were the very reason he’d dictated that every fireman must wear at least a T-shirt on duty. None of the firemen in the aft fireroom had T-shirts on now, because for this task he’d given special dispensation. That didn’t mean Tabby or the several other female “firemen” they now had were included in that dispensation. Spanky had thought that was understood. Apparently it wasn’t. ’Cats could be very literal-minded-especially when they wanted to be.

“Tabby,” he repeated, “get over here!”

Bashear looked at Spanky curiously, wondering what this was about. That he hadn’t thrown an instant fit over the lack of T-shirts was strange enough. His opinion on that was common knowledge and a source of some amusement. None of the female deck apes (and there were a lot more of them) had to wear shirts for special duties that anyone else might remove theirs to perform. But Spanky McFarlane had bent as far as he intended to just by letting females of any sort into his engineering spaces. If they were going to be down there, they were going to wear clothes! Tabby tormented him constantly, but he was torn by his own personal axiom: if somebody does something that bothers you, either pretend it doesn’t or make them stop. In Tabby’s case, he couldn’t figure out how to do the second, so he tried unsuccessfully to do the first. He wasn’t fooling anybody.

Oddly, instead of undermining his authority, his… predicament probably strengthened it. Early on, he was viewed by many ’Cats as some sort of omniscient, unapproachable wizard. They now knew he wasn’t, but although they weren’t terrified of him anymore, they were amazed that a mere mortal such as they (albeit without a tail) could be so knowledgeable about machines. Wizards and magicians didn’t have to know things, or so the tales of younglings said. They just cast spells and things occurred. Spanky couldn’t cast spells; he actually knew things, and he’d come by all that knowledge the hard way: he’d learned it the same way everyone else had to, and they respected him immensely for that.

Tabby hopped over the ’Cats on the deck plates that were hauling debris from within the number three boiler with a hoe-shaped tool on their hands and knees. Others gathered the stuff up and put it in heavy canvas bags to be taken topside. Amazingly, Tabby snatched a T-shirt from a valve wheel as she approached and pulled it over her head.

“You wanna see me, sir?” she asked.

“Uh, yeah.” Spanky gestured back at the work. “That bad, eh?”

She shrugged. “Whoever overhauled that boiler did a piss-poor job on the firebrick. Waadn’t me. I guess with the hurry we were in, somebody got sloppy.”

“Probably so. You were supposed to tell me if you wound up having to tear it down and rebrick it, though.”

“We be done by tomorrow,” she assured him. “I didn’t think it was worth buggin’ you about.”

Spanky took a breath. “Now you listen to me,” he said in a low, intense tone. “Anything that affects this ship’s readiness to steam at a moment’s notice-anything the Skipper needs to know before he can make a decision based on that readiness-is always worth buggin’ me about, no matter how trivial it seems. Last I heard, you were planning on replacing a few firebricks, and I specifically told you to let me know if you had to do more. I didn’t hear from you, so I came in here thinking we still had three boilers, in a pinch. Right now, the Skipper thinks he has three boilers, but he doesn’t, does he? All he’s got is two-with a lot of crap in the way of one of’em. What if a squadron of them Brit, Imperial, Company-whatever-frigates suddenly shows up on the horizon? The Skipper’ll be deciding what to do based on his certain knowledge he’s got three boilers! Don’t ever just jump up and crack this deep into something without telling me first! Is that understood?”

Tears welled in Tabby’s large amber eyes.

Spanky was stunned. “Goddamn!” he managed. “Are you fixin’ to cry ?” His voice was incredulous. His own eyes went wide when Tabby’s tears gushed out and coursed down her furry cheeks.

“I… I so sorry!” Tabby practically moaned. As usual when she was upset or excited, she lost her careful drawl. “You got so much.. . so much other stuff; I just want to not bother you with more! I sorry, Spaanky! Please no be maad! I never, ever do nothing you no tell me! I wear shirt all the time! Just please no be maad at me!”

For a moment Spanky and Bashear were both speechless. Tabby sniffled loudly a few more times, then tried to collect herself. She began wiping the tears on her clean shirt, smudging it with wet soot and firebrick dust.

“I’ll swan,” Bashear said softly.

“Shut up, you!” Spanky growled. He turned back to Tabby. “Ah, lookie here,” he said clumsily. “No sweat. Just don’t do it anymore, see? ” Tabby nodded almost spastically. “All right, then.” He looked around, staring at anything but her for a few moments. If the work detail had heard or even paused in their labor, he couldn’t tell. They were still drawing the broken firebricks and passing them along to others, who dropped them into sacks. Finally Spanky looked back at Tabby. He was glad she’d apparently composed herself. He hadn’t come here to jump all over her; he actually had something else on his mind. Still, what he’d said was true and needed saying. Especially now.

“Look, Tabby, just get the job done, now you’ve started it. I’ll report the boiler’s down to the Skipper.” He gestured at the detail. “Things look well enough in hand.” He paused. “You’re doing a good job here in the firerooms. Those squirrelly Mice taught you all right, God knows how. I expect you know the old gal’s boilers as well as they do by now.” He paused again and took a breath. “Here’s the deal. I made Aubrey chief down here because he was a torpedoman. He knew turbines and steam plants, but he never was really all that good with the big stuff. Never should’ve used him like that. Should’ve left him working with Bernie Sandison back in Baalkpan.” He shook his head. “Well, Aubrey’s dead, and I’m going to split Engineering back into two divisions: steam plant and propulsion. Every fireman on this tub is a ’Cat now, and it would be stupid to take some guy off something else and put him in charge in here when you’d know more than he would, so as of right now, you’re chief of the boiler division, got that?”

Tabby’s surprised eyes began to fill again.

“But only if you don’t start cryin’ over it, for God’s sake!” Spanky added hastily. “There will be no cryin’ in the firerooms, clear? Not ever!”

Instead of answering, Tabby lunged forward and touched him on the cheek with her muzzle, tongue slightly extended. Spanky knew the gesture was a Lemurian version of a modest, chaste kiss. Passionate kissing involved much more licking. Even so, he was thunderstruck and didn’t have a chance to say anything before Tabby bolted back to the detail she was overseeing.

Bashear, uncertain how Spanky would respond, guided him back toward the air lock and they cycled through. “C’mon,” he said. “I still need you to look at that winch.”

“What the hell was that all about?” Spanky asked quietly, still torn between shock, fury, and… God knew what. “What the hell’s got into her? I had to chew her out about letting me know, but I figgered she’d make some crack and get back to work! Then she starts bawling! And that… whatever she did to me… Do you think she’s crackin’ up?”

“You really want to know what I think?” Bashear asked as they went through the forward air lock and headed for the companionway.

“Well… sure.”

“I think she’s sweet on you,” Bashear said seriously.

“Horsefeathers!”

“Sweeter than honey on a comb. I wonder how many engineers ever had sweethearts in the fireroom? Not many, I hope.”

Spanky turned on him. “Shut the hell up, you goddamn perverted, filthy-minded ape!” he said hotly.

“There!” Bashear said. “Now that’s more like it. Thought I’d never get a rise out of you!” His voice became serious. “She is sweet on you though, and it shows. A lot. What’re you gonna do? Turn Silva?” That was the increasingly accepted term for men suspected of having “taken up” with a Lemurian gal.

“She ain’t ‘sweet’ on me,” Spanky protested. “Sometimes she’s downright insubordinate!”

Bashear nodded sagely. “That’s always the first sign. ’Cats ain’t really all that different from us, you know. Once you get past the fur and ears-and, well, the tail.” They’d reached the weather deck and were passing under the amidships gun platform that served as a roof for the galley. Chief Gunner’s Mate Paul Stites was supervising a maintenance detail on the number three, four-inch-fifty. They were installing new oily leather bushings in the recoil cylinder. Below, Earl Lanier, the bloated cook, had left a heap of sandwiches on the stainless steel counter. Bashear snatched one. “Wimmen is all the same,” he continued. “Even ’Cat wimmen, I bet. They take to thinkin’ you belong to ’em and they start treatin’ you like dirt. Take advantage. I been married twice, so trust me, I know.” He looked at Spanky. “You want my advice?”

“No.”

“You can’t just ignore it,” Bashear advised anyway. “You treat her like a dog, pretend she ain’t there, it’ll just get worse. I don’t know what it is about ’em, but every time I try to get rid of a dame, they just try harder. You can’t chase ’em off.”

“Well… supposin’ you’re right-which you ain’t-how would you make Tabby get over her fit?”

“Easy,” Bashear said around a mouthful of sandwich. “Be nice to her. I never could keep a dame I really wanted. Nobody can. It’s the rules.”

CHAPTER 2

East Africa

“ General of the Sea” Hisashi Kurokawa strode slowly beside the immense, deep basin, lightly slapping his left boot at every step with a short, tightly woven whip. A wisp of dust drifted away from his striped pants leg with each strike. The handle of the whip was garishly ornate and the gruesome golden sculpture capping it appealed to his sense of mockery. It looked strikingly like a flattened Grik face. Beyond the basin, a hot wind blew swirling dust devils amid a sea of Uul workers swarming over the flat, denuded landscape that bordered the wide river, and the hazy orange sun blazed fiercely down from above. The wind reeked of rot, feces, and an untold number of partially cannibalized, festering corpses. Those scents were renewed each day as the defecating, dying thousands toiled, and the stench was almost unbearable. Yet bear it he did. To show weakness of any sort under the circumstances was tantamount to suicide in the great game he played.

Skeletal frameworks arose amid this teeming mass, erected by muscle power alone. Once again Kurokawa marveled at the discipline that could accomplish so much with such apparently mindless labor. Groups of Grik Uul performed many of the same functions as various machines in a factory. Some shaped massive timbers with a tool resembling an elongated adze-and that was all they did, while other groups were dedicated solely to moving the timbers to areas where still others set them in place. A little farther along, other “teams” did the same thing with an only subtly different timber. It was the most wondrous example of nonmechanized mass production he’d ever seen, and the scope and specialization of the endeavor surely put the construction of the Great Pyramids to shame.

There were overseers, to be sure, that served much the same purpose here as sergeants and officers might in battle. They orchestrated the timing and direction of every task. Some led bearers to the next mighty “skeleton” where their particular timber was required. Others lashed a continuous stream of bearers, burdened with massive tree trunks felled in the ever more distant forest, toward the timber shapers’ tools. Uul dropped from illness or exhaustion everywhere he looked, only to be trampled to death by those behind them. Some took quick, passing gobbets of flesh from the often still-moving dead.

Kurokawa was sickened, but enthralled. Such discipline! Such symmetry! Such simple, mechanical grace! Grik industry was driven by a living Grik machine. When a part broke down or wore out, it quickly and automatically replaced itself with another! He felt himself on the very cusp of some profound revelation concerning the most fundamental nature of things. He was a naval officer but also an engineer, and the complexity of machinery had fascinated him even as a child. Here, however, was a machine that appealed to him in an almost spiritual way, not because it was complex but because of its almost perfect simplicity. He still considered himself piously devoted to his emperor and had utter faith in Hirohito’s divinity, but he felt close to some sort of personal… reformation.

He paused a moment, peering into the immense basin. The labor underway down there was of another sort entirely, utilizing completely different materials and techniques. It was also, of necessity, using a lot of his own men. They were the overseers in this case, each with a team of translators and runners, but as miserable as the working conditions were on the expanding plain above, it was pure hell down in “the Hole.” Some of his precious men had actually died just from the heat! He didn’t consider them “precious” for their own sakes. As far as he was concerned, most were traitors. If that were not the case, he would still have the mighty battle cruiser Amagi at his disposal. They had failed in their duty to him and the emperor by allowing her destruction at the pathetic hands of-

He forcibly calmed himself, taking deep, flared-nostril breaths. He’d begun to realize that his tantrums accomplished little. They terrified and intimidated his men but had no effect on the Grik. Besides, he always felt drained after they ultimately ran their course. Better to hold the hatred in, let it help fuel him. In any event, what made the treachery of those who died of something as ridiculous as heat even more egregious was that Amagi ’s survivors were “precious” only as an irreplaceable resource. Their value was reckoned in respect to what they knew, by what they could do for him to elevate his prestige and secure his position. There were too few of them left as it was, and after the last “culling” following their defeat at Baalkpan, he had fewer than four hundred. He needed to use them sparingly, but he did need some for this… and other ambitious programs. He grimaced and resumed his leg-slapping stroll.

Another man carefully paced Kurokawa, trying to stay just slightly behind but close enough to hear any possible word that might pass his true commander’s lips. He was taller, slimmer, and unlike Kurokawa, who always wore the dark blue, increasingly elaborate uniform made by the finest Grik tailors, his was white, and still genuine Imperial Navy issue. The man’s name was Orochi Niwa, and he’d recently rocketed from the rank of a lieutenant of Amagi ’s small SNLF (Special Naval Landing Force) contingent to “General of Hunters” in the army of the Grik. Regardless of his new rank and the… army… he served, he was fully aware who-literally-owned his life. He had no illusions that Kurokawa liked him or even really trusted him; Kurokawa would sacrifice him without remorse if he perceived the slightest reason or advantage. The only purpose for his exalted status was that Kurokawa knew he himself couldn’t actually be everywhere at once, and he’d instituted far too many “projects” to personally oversee. Besides that, he also wanted-needed-a Japanese presence at the war councils of the Grik where tactics were discussed. Kurokawa attended those councils dedicated to grand strategy, and his input was now much appreciated, but he readily admitted he had no real knowledge of, or interest in, land warfare. Niwa did. Niwa had also made it abundantly clear that he was wholly aware of his “place.” Regardless of his Grik position, he still served Kurokawa, and through him, the Emperor.

“I suppose we should hurry.” Kurokawa seethed, picking up the pace. “Our ‘masters,’ ” he snorted, “will be waiting.” Niwa didn’t point out that the Grik High Command had probably been waiting for the better part of an hour. He didn’t say anything at all. Together, the two men strode more briskly among the yard workers, occasionally dodging groups fixated-almost like ants-upon their tasks. Finally, after they’d left the basin and the majority of the dust and stench behind, they joined a group relaxing under the shade of a crude wooden structure, taking their ease and enjoying elaborate bowls brimming with cool liquid. Niwa politely refused an offered bowl. He had no idea what was in it, but assumed it would be something vile and repulsive.

“You are late-as always,” growled General Esshk, standing to loom above them. Esshk was the most imposing Grik Niwa had ever seen; the mere sight of him always made Niwa cringe a little, at least inwardly. Esshk was First among Generals in the Army of the Grik, and he usually dressed the part. Bronze breastplate, greaves, and cuffs, along with a scarlet cape and kilt gave the vague impression of a Roman tribune. The tufted bronze helmet he held under his massive arm completed the ensemble. A smoky black crest rose slightly atop his head as he spoke.

“I have been inspecting the work,” Kurokawa said by means of explanation, not apology.

“How does it proceed?”

“Well enough on the… traditional vessels,” he replied. “Slower than I would like on the other.”

“What is lacking?”

Kurokawa shrugged. “Heavy equipment, cranes, pneumatic riveters, a steady supply of good iron instead of the useless cast plating you continue to force upon me. Qualified yard workers most of all.”

“The cast plating is what we can do. The same iron served well enough for cannons!”

“And it will shatter the first time a shot is fired against it!” Kurokawa stated, voice rising. “I have told you what is needed and how to make it, yet still you send me the same thing. Have you learned nothing?”

Esshk seethed. He knew Kurokawa was right. He was always right about such things. He’d even seen the plating shatter when a gun was tested against it. “The Celestial Mother grows impatient,” he temporized. “We stand on the brink of losing Regent Tsalka’s domain. We have withdrawn from contested lands as you suggested, despite the. .. difficulty… but Ceylon is important!”

“And I told you we would lose it before we could take it back,” Kurokawa replied, repeating an old argument.

“But that is precisely where much of your ‘steel’ is made!” Tsalka interjected, speaking up.

Kurokawa bowed to the Regent. “Indeed. So we must hold it long enough to produce and remove as much as possible before it falls. Complete the new foundries here, and it will be a lesser loss.”

“My own realm!” Tsalka almost wailed.

“This has been decided already,” Kurokawa flatly stated. “You will get it back. In the meantime, I must have true steel, not only for this project”-he waved at the basin-“but for others. There can be no ‘flying machines’ at all, for example, without steel.”

Esshk glanced at the newly appointed General Halik. Halik had been a mere “entertainment fighter,” basically a gladiator, for many seasons and had grown quite too old for that. That was precisely the reason he’d been “elevated” and tapped as a general. He seemed to have naturally developed an instinct for defensive fighting. It would still be a year or more before the first “defensive” forces were ready to deploy, and they’d be little more than hatchlings even then, but in this new kind of hunt, this “war,” much was being accomplished on the fly. Esshk was certain their enemies had many of the same issues to contend with, but most likely some were direct opposites. As prey, they needed to learn offensive tactics, while a whole new class of Grik that was capable of defense had to be grown.

In the meantime, Halik had sponsored the elevation of other warriors in whom he recognized certain traits, and hoped they would serve as a nucleus for his new cadre of junior officers. Esshk had a sinking feeling that war as his people knew it was changing forever. Perhaps their entire society would ultimately be unrecognizable, but he would accept that if it meant his very species might ultimately survive. Some didn’t yet recognize the threat and were not particularly supportive, but he’d gained the tentative support of the Celestial Mother, and that was all that mattered. He looked at Halik. “Is there nothing you can do?”

“In Ceylon?”

“Indeed.”

“I would have to go there and see for myself,” Halik said. His speech had improved amazingly over the last months. “A true ‘defense’ may not be possible, but spoiling attacks might slow the enemy advance. Grasp time.”

Tsalka was nodding, but Esshk was thoughtful. Halik represented much more to him than just another general. He might be their only hope.

“Very well. You will go there by the safest route. Do not allow yourself to be slain! That is a command! You still have much to do.” Esshk’s eyes turned to Niwa. “You have worked closely with General Halik. Perhaps you should accompany him. Together you will learn not only the… ‘tactics’ of the prey-” He caught himself. “I mean, the ‘enemy,’ but you may better learn how we might counter them during this… transitional period. General Niwa, you will learn about the Grik alongside the Grik. General Halik, you will learn more about the enemy from one who knows them better.”

“But General Esshk!” Kurokawa and Niwa protested at once. Niwa realized what he’d done and clamped his mouth shut. Kurokawa, on the other hand, continued. “You would deprive me of my own best counselor?”

Esshk peered at him. “I deprive myself of Halik, but then, I still have you. I have been given to understand you need no counsel.”

“Not at sea!” Kurokawa sputtered. “But I am no land general! I have never claimed to be. I do understand land strategy, and how it must be combined with that of the sea, but to fully appreciate that combination, I need my best land tactician.” Kurokawa paused and blinked, realizing Esshk had goaded him into admitting, for the first time, that he didn’t know everything. Damn him! Esshk might only now be learning the subtleties of modern war, but he had long been a chess master of debate and intrigue. Kurokawa had almost forgotten that. He had also forgotten, or finally learned, how important it was to have someone near him he could trust-somewhat-and even speak candidly with on occasion. Niwa, subservient and cowed as he was, was the closest thing to a “friend” Kurokawa had on this world. Now Esshk would deprive him of even that.

“Exactly,” said Esshk, and he drove the final nail. “General Niwa will be more valuable to us both after this experience. He will be General Halik’s Vice Commander, and the two of them will learn from each other and the enemy at the same time. At least one should survive to return with the tactical observations we desire.”

“Thank you, Noble First,” Halik said humbly, and it suddenly became clear to Kurokawa that Halik had requested this! Why? He looked at Niwa and saw his nervous expression. How can I use This? he thought. I stood up for Niwa and he will remember That. Niwa has an opportunity To gain Halik’s and even Esshk’s trust more fully Than I ever could. I will… miss… Niwa, but perhaps This might work To my advantage.

Kurokawa gave Niwa a small but significant nod. “Oh, very well,” he said. “It does make sense, I suppose. You may have him so long as I have your word he will not be required to ‘destroy himself ’ or any such nonsense if he and General Halik cannot save Ceylon.”

Esshk seemed surprised. “General of the Sea Kurokawa,” he exclaimed, “have I just seen you display concern for a member of your pack? How uncharacteristic!”

Kurokawa inwardly smoldered. He knew Esshk would take it that way and it exposed a vulnerability, but it was worth it to gain Niwa’s ultimate trust.

“I am concerned for both General Niwa and General Halik, as well as our cause. We cannot spare either of them.”

“There we are agreed,” Esshk said. “Fear not, the destruction of Uul warriors and their leaders is at an end. You were right regarding how wasteful it is. Even in defeat, not all are ‘made prey,’ and even those who are… provide a valuable service.”

Kurokawa wondered about that last comment, but shuddered slightly at what he thought it probably meant.

Esshk appeared satisfied with the proceedings thus far. He lapped at a bowl of… something, then looked expectantly at Kurokawa.

“Mmm,” Kurokawa said, looking at Niwa. “General Niwa, I believe you know General Halik?”

Niwa controlled an impulse to gulp. “Yes, Cap-General of the Sea.”

“Good. I will therefore accept your enthusiastic offer to participate in this important and glorious mission!” Kurokawa affected a false, grotesque smile.

“Uh… thank you, sir.” Niwa looked at Halik, who was staring back at him now.

“That’s the spirit!” Kurokawa beamed genuinely. “General Esshk?”

Esshk looked at Halik, then Niwa. “You will leave almost immediately with a significant escort of ships,” he said. “It is a dangerous sea. The escort will be loaded with supplies, but they well might be the last we send. Try to defend Ceylon as long as you can, and fill every homebound ship as full of ‘steel’ as possible. Those ships will likely not return to you.”

“Yes, First General,” Halik said.

“The two of you must defer to Vice Regent N’galsh, of course, but in reality you will command Ceylon and all of India. Every Hij and Uul there will obey you. Use them, but try not to waste them. Send me more like yourselves if you discover any.” Esshk stood. “Now, we all have much more to do than lounge about, enjoying the view.” Niwa almost coughed. “I suggest,” Esshk continued, “that Generals Halik and Niwa remain here a short while.” He looked at them. “Get to know one another better. Decide if you have any special requirements.”

The meeting broke up then. Even Kurokawa disappeared into the swirling dust that seemed to be growing worse, leaving Niwa and Halik alone under the increasingly dubious shelter.

“Why?” Niwa asked without preamble.

“You interest me, General Niwa,” Halik said. “I think I might learn much from you.”

“Like what?”

“Like how to survive when you are surrounded by enemies. I have learned to do that in the arena, but to do so every day… that is different.”

“What do you mean?”

Halik rasped a chuckle. “I think you know.” He paused, catching occasional glimpses of the horror in the dust. “We are warriors, you and I, accustomed to holding the sword in our hands. Our masters have never done that; they are not allowed, so they fight with their minds and words and barely know the feel of a sword. We are important to them because they think we can fight with our swords and minds.” Halik looked at Niwa, and Niwa would have sworn the Grik was excited! “We will leave this place! That cannot disappoint you. Then we will see if they are right!”

CHAPTER 3

Yap Island (Shikarrak)

Chief Gunner’s Mate Dennis Silva savagely hacked at the indifferent army of spiny, bamboo-like shoots standing before him like a shield wall of personal foes. The swath of “ bamboo” couldn’t be more than a mile wide at most-judging by the crummy “chart” Silva had, the whole island wasn’t much wider than that across this point-but it seemed endless, and the party’s progress through it had been excruciatingly slow. Even the mighty Dennis Silva was beginning to tire. Sweat glistened on his skin, collecting grime and fragments of the shredded flora, and the patch covering his ruined left eye was soggy and blotched with salt. He stopped for a moment to catch his breath and untwisted the canteen from the rope belt around his waist. Sloshing it experimentally, he unscrewed the cap and took a shallow swig.

“Now I know what a ant feels like,” he pronounced a little breathlessly. “ ’Cept I don’t guess ants have to gnaw their way through everything to get anywhere.”

The rest of the small party accompanying him was at least as tired as he was after swinging their decidedly inferior cutlasses to widen the path behind him. Silva was doing the lion’s share of the work, but the steel in his pattern of 1917 Navy cutlass was of infinitely better quality. In response to his statement, his companions could manage only a few gasping grunts. The heat was hellish and the humidity oppressive, but the sun didn’t bother Silva anymore. He was tanned so dark, his various smudged tattoos had become merely darker, unrecognizable discolorations on his skin. In contrast, his now longish hair, matted beard, and the light, curly hair that generally covered him from neck to feet had turned almost pure white. For clothing, he wore only his battered “chief ’s” hat the Bosun had given him, a pair of cut-off Lemurian-made dungarees, and “go-forwards” he’d fashioned for himself.

He was otherwise equipped with a large shooting pouch, slung over his shoulder, made from the almost indestructible hide of a rhino pig. It contained all the implements, components, and accessories necessary to keep the “Doom Whomper,” the. 100-caliber rifled musket he’d made from a Japanese anti-aircraft gun, fed, maintained, and happy. He’d given his pistol belt to Sandra Tucker-she knew how to handle a 1911 Colt-and there wasn’t much ammo for it anyway. She could use it if she needed it, but it was his job to keep that from happening. Instead of the 1911, Silva still carried his cutlass, and a long-barreled flintlock pistol he’d taken from the Company assassin Linus Truelove. Silva expected, with some satisfaction, that Truelove had been reduced to a few floating ashen specks, when Silva had contrived to blow up Ajax, but the pistol was a dandy. It would shoot only once before reloading of course, but they had plenty of ammo for it.

He took the opportunity to fish a whetstone from his pouch and run a few swipes down each side of his cutlass blade. He then offered the precious whetstone to the others, and when they took it, he watched keenly while it made its rounds before being returned. Dropping the stone back in his pouch, he carefully secured the flap. He took a deep breath and resumed his attack on the shoots. They continued moving slowly under the sweltering sun, through the rest of the morning and into the early afternoon. Eventually, finally, it appeared that the stalks were beginning to thin. After a little longer, Silva was sure of it, and he slew the final shoots like the helpless stragglers of a routed army.

Before him now stretched a virtual savanna, filled with long grasses of various types. Some looked like “normal” grass, like coastal Bermuda, but there were large, almost islandlike clumps of taller stuff that reminded him of kudzu, complete with blue and purplish foxtail blossoms congregated near the edges. Strange birds (real birds, it seemed) flitted and swarmed around the clearing on strange wings, almost like dragonflies. There were a few of the now ubiquitous lizard birds, which occasionally streaked in to snatch one of the inoffensive-looking things, but even the birds nearest the victims didn’t appear to give them any heed. Perhaps from within the apparent security of their multitudes, the weird little birds just didn’t notice.

“Every time I turn a corner on this goofed-up world, I see somethin’ even more goofed up,” Silva mumbled. He surveyed the expanse of the savanna for several moments, trying to divine if it represented a threat of any kind. There were few large animals on the island, and most of those behaved aggressively only within the bounds of their apparently single-minded desire to be left alone. They were retiring and extremely heavily armored in the manner of giant land tortoises, even if any physical resemblance was remote. The smaller ones could be killed, with the Doom Whomper at least, and their flesh was fat and wholesome, but they’d learned that killing anything on this island came with a dose of risk. They’d met an interesting variety of smaller predators and scavengers that were far more capable and dangerous than they appeared. All were smaller than a man and most were fairly skittish. Some were not, and those were usually more than happy to contest them for the meat.

So far, they’d encountered only one type of really large, dangerous animal during their brief, limited forays-and those didn’t exactly live there. Silva now knew from experience that they had to be particularly watchful for the occasional, early-arriving “shiksak.” He called them “shit-sacks”; of course, “shiksak” was a Tagranesi word and he tended to prefer his own names for things. No matter what anybody called them, the damn things gave him the creeps.

Once, if anybody had ever told him he’d run across anything scarier than a “super lizard” on land, he’d have called them a liar. Now he knew better. Shiksaks were almost as big as super lizards, and although generally slower moving, they were actually quicker in a sprint. Maybe “lunge” or “leap” was a better term. They struck him as kind of a twisted cross of a crocodile, an eel, and a frog. They had big, fat bodies with long swimming tails with a ridge or finlike arrangement beginning behind their heads that ran the length of their backs, all the way to the ends of their tails. Their forelegs were little more than stumpy, clawed “flippers,” but they had long, powerful hind legs with heavily webbed “feet” like those of a frog or toad. Add long, broad heads full of lots of teeth to the mix, and they even looked sort of comical in a way, like a giant pollywog that had swallowed most of an alligator. The young, towheaded Abel Cook, who’d once been fascinated with the dinosaurs of their “old” world, believed they were a type of mososaur that had evolved an amphibious capability to lay their eggs on shore, away from this world’s more treacherous seas. Maybe so. “Mosey-saurs” they may once have been, but Silva was only concerned with what they’d become.

Individually, they weren’t really that bad, he admitted to himself. A single shiksak wasn’t as scary as a single super lizard. Unlike super lizards, which seemed to possess a kind of creepy cunning, shiksaks apparently weren’t any smarter than pollywogs. Also, even if their thick, croclike skins made them practically bulletproof to the Imperial muskets, nothing was immune to his treasured Doom Whomper. No, so far the most pressing menace represented by the usually lethargic “early bird” shiksaks was that the sneaky bastards could change goddamn colors! That just wasn’t fair. They crept ashore, made a nest, and plopped down to lay their eggs. Sprawling there, in the dense Yap, or “Shikarrak ” Island jungle, they were difficult to see-and they would gulp down anything that came wandering by. Fair or not, even that wasn’t an insurmountable problem: be careful, watch where you’re going, and stay in pairs. Simple enough. The really big, scary problem-according to what they’d squeezed out of Lawrence (“Larry the Lizard”)-was that within a month the whole island would be working with the damn things like maggots in meat, and nothing that wasn’t armored like a tank, couldn’t climb a really big tree or squirm down a tiny hole, would survive.

No human or ’Cat would fit down a hole small enough that the shiksaks couldn’t dig it out, and the trees… would be full of other dangerous things. Larry had been here before when things got like that, during his “trial,” and he’d survived. That was the point of the trial-to test his wits. But he’d been all alone, with only himself to look after. Dennis Silva had to make sure nothing happened to Princess Rebecca, Lieutenant Tucker (the Skipper’s dame), the Lemurian Captain Lelaa, Sister Audry, and the gawky but gutsy Abel Cook. Maybe he would concern himself a little with a few of their Imperial companions who didn’t like him very much-or maybe not. As he saw it, his plate of responsibility was pretty damn full.

Larry hadn’t been willing to “blow” about the danger at first, even though he blamed himself for their presence there in the first place. He’d sworn an oath. He finally agreed to tell Rebecca and Miss Tucker, since no female was ever expected to undergo the trial. Even that might have been stretching things, but he just couldn’t bear to let his precious Rebecca face the dangers unprepared. Silva was still a little put out that Larry hadn’t just told him. He had to know the girls would blow. Oh, well, at least this way Silva got the word without Larry having to technically break his. One way or another, he’d learned what he was up against, as far as looking after the girls was concerned, and ultimately that was all that really mattered. Larry could look out for himself.

Dennis examined the tall grass a little longer, then shrugged. He couldn’t see anything dangerous, but that didn’t mean much. He thrust his cutlass into the scabbard tied to his belt and unslung the Doom Whomper. The big, heavy thing had been strapped diagonally across his back to keep it out of the way. “All right, fellas, come on out, I guess,” he said. “If there’s any boogers out there, I can’t see ’em. Just keep your eyes peeled.”

Abel Cook emerged first from the bamboo forest. He’d also secured his cutlass and was awkwardly carrying an Imperial musket in what he seemed to consider a proficient and vigilant manner. He managed a relieved, tired smile as he joined Silva. Midshipman Brassey of the Imperial Navy appeared next. The dark-haired boy was no older than Cook, and even if he was more accustomed to his cumbersome musket, he seemed just as relieved to escape the oppressive, confining thicket.

Captain Rajendra was close on the boy’s heels. He was the only one of the marooned survivors with skin darker than Silva’s, and whereas all the color had been bleached from Silva’s, Rajendra’s hair, bushy mustaches, and short, thick beard remained jet-black. In Rajendra’s case, it was probably racial, but Silva had never asked and didn’t care. Courtney Bradford might have been fascinated to learn more about Rajendra’s genealogy, but God knew where Bradford was now. He might be in Baalkpan or points west. He might even be ironically near, with the Skipper, searching for the castaways. It was ironic because even if that were true, they would never find them. The Skipper had no way of knowing that the survivors of Ajax had become castaways and Ajax herself had literally ceased to exist. Silva usually enjoyed irony to a certain degree, even if he’d only recently learned the word. He even managed to glean a small measure of amusement from it in the current situation. He recognized irony for the bitch she could be and tended to be philosophical about it when she turned around and bit him on the ass.

Rajendra didn’t appreciate irony at all, as far as Silva could tell. Apparently he didn’t appreciate much of anything. Even after all these weeks, he seemed able to summon only a scowl when his eyes fell upon Dennis. Silva was philosophical about that too. He’d saved the man’s life. He’d saved all their lives. But the way he’d gone about it

… He supposed it was inevitable there’d be a touch of resentment. Like the others, Rajendra went armed with a musket, but he also carried a brace of pistols and a sword. Occasionally, absently, Silva wondered if the man’s desire to use the weapons on him had waned at all. He didn’t lose sleep over it, but it could be distracting to know he really needed to watch his back as well as his front.

At least one other “person” looked after him besides the wellintentioned Abel Cook. Larry the Lizard may not have been willing to technically spill the beans about the island, but he was Silva’s friend. Larry was a Tagranesi, a species strikingly similar in appearance to the hated Grik. He was colored differently and not as big, but those distinctions hadn’t been particularly clear when they’d met.

There’s irony for you, Dennis thought, remembering that he’d actually shot Larry, thinking he was a Grik, but the little guy didn’t hold it against him. Hell of a lot more forgiving Than Rajendra. I didn’t even shoot him. Irony again. Of course, having now seen the Grik and participated in the Battle of Baalkpan, Larry understood why Dennis had shot him. That had been a different time. The “lizards” were the enemy. All the lizards. They now knew not all Grik-like beings on this world were Grik, and that added even more confusion to an already screwed-up situation. Just like folks, Dennis thought, hell, even Japs. There’s all different sorts. Things sure were a lot simpler back when. you could just kill ’em all without needin’ to sort ’em out first. Oh, well, those days were over and it was probably just as well. Even Silva never thought in quite such simple terms anymore. He was glad Larry liked him-and that he always seemed to bring up the rear when one of their Imperial co-castaways was behind Dennis in the bush.

Appearing last, as usual, Larry was also armed with a musket. The weapon didn’t really fit him-he just wasn’t built for it-but he’d probably had more practice with one than most of the Imperials on the island.

“There you are, you little runt,” Silva said. “I figgered I’d have to go find your lost ass… again. You been chasin’ butterflies or bugs or something? Find a worm to eat?”

“I not lost,” Lawrence grumped. “I thirsty, though.”

“Shouldn’t have drank all your water so fast then.”

“I ’ound ’ater. I al’ays do.”

“Even if it leaves you draggin’ ass along like a one-legged toad? ” Silva accused.

“I not draggin’ ass. You draggin’ ass. I go slow to stay ’ehind you. I don’t need to hack a hole to get giant, useless ass through here.”

“Mmm.” Silva looked at the Tagranesi, who stared back with his head cocked slightly to one side. According to Bradford, the young darkening and lengthening crest atop it meant he was nearing adulthood-if he hadn’t already reached it. Whether he was actually there or not, he increasingly acted like it, and joking aside, Dennis knew exactly what Lawrence had been up to. Oddly enough, his almost orange, tigerstriped, downy-furry hide afforded him considerable camouflage, even against the dark green, hazel, and almost bluish foliage of the dense jungle covering most of the island. As usual, he’d been hanging back to make sure he’d spot anything that went after the main party so he could give warning before it was upon them. He had a musket and he could shoot it, but his formidable claws and teeth were probably a better deterrent to anything sneaking up behind them.

“Well,” Dennis said when the group had gathered around him, “let’s see if we can get across that patch yonder in one piece.” Without waiting for comments, he started across the clearing, entering the ever-deepening grass. Behind him, Rajendra slung on his musket and pulled out his pistols-the better to engage close-up threats. Silva was mildly impressed that the usually puffed-up Imperial did something he approved of without being told.

“Mister Silva?” Abel asked. “I notice that you are avoiding the large clumps of colorful foliage.”

“Yep. If there’s any dangerous beasties out here, I’d expect ’em to live in the thicker crap.”

“May I approach one closer?”

Silva stopped. Abel was kind of Bradford’s protege, and was apparently just as interested in strange critters and bushes as the Australian “naturalist” was. “Well, I suppose,” he grumped. “You’re the next thing to grown-up, and I can’t nursemaid you forever. Just be careful.” He raised his voice. “Larry, Mr. Cook’s gonna gawk at them weeds. Keep an eye on him, will ya?”