The Adventures of David Simple

Sarah Fielding

1744

Contents

I Introduction

II Preface

III BOOK I

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

VII

VIII

IX

X

XI

IV BOOK II

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

VII

VIII

X

IX

V BOOK III

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

VII

VIII

IX

VI BOOK IV

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

VII

VIII

IX

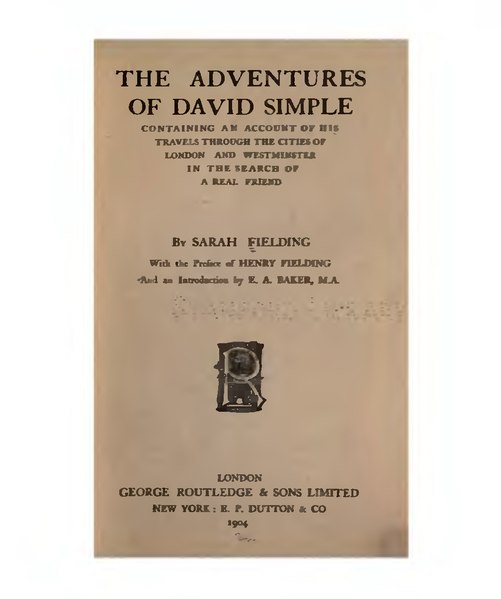

THE ADVENTURES

OF DAVID SIMPLE

CONTAINING AN ACCOUNT OF HIS

TRAVELS THROUGH THE CITIES OF

LONDON AND WESTMINSTER

IN THE SEARCH OF

A REAL FRIEND

By SARAH FIELDING

With the Preface of HENRY FIELDING

And an Introduction by E. A. Baker, M. A.

Part I

Introduction

BY E. A. BAKER, M. A.

It is possible that The Adventures of David Simple would have been far better known as a work of some importance in the early development of English fiction had the authoress’ name not been Fielding. To be the near relative of a great genius is by no means a passport to fame: a good many instances may be called to mind of its being altogether the reverse. Although Richardson himself complimented “Sally” upon her knowledge of the human heart, and quoted her saying of “a critical judge of writing,” perhaps Dr. Johnson, “that your late brother’s knowledge of it was not (fine writer as he was) comparable to yours,” and further, “his was but as the knowledge of the outside of a clockwork machine, while yours was that of all the finer springs and movements of the inside”; in spite of such eulogy from such a man, Sarah Fielding’s name has been completely overshadowed by that of her brother, and is now familiar only to special students of our eighteenth-century literature.

What little, furthermore, we know about herself has been gleaned mostly from the records of her brother’s life. She was born three years after him, in 1710, at East Stower at Dorsetshire. Her father was Lieutenant (afterwards General) Edmund Fielding, descendant of an old family that numbered the Earls of Denbigh in its elder branch, and in its younger, to which he belonged, the earls of Desmond in the peerage of Ireland. Her mother was Sarah, daughter of Sir Henry Gould. She died in 1718, leaving four (or five) children; one daughter had died in 1716. We can fill in the blanks of Sarah Fielding’s life only with the dates and titles of her works, all of which, with the exception of the first, are utterly dead and forgotten. “The Adventures of David Simple: containing an account of his travels through the cities of London and Westminster in the search of a real friend, by a Lady,” was published in 1744, and a second edition, with a preface by her brother Henry, was issued the same year. In 1747 was published a Collection of Familiar Letters between the Principal Characters in David Simple and some others, with preface by Henry Fielding, and containing five lengthy letters by him. A third volume of David Simple was published in 1752. Two years later, Miss Fielding collaborated with Miss Collier in the production of The Cry, a Dramatic Fable. Other works are: The Governess, 1749; Lives of Cleopatra and Octavia, 1757; a History of Ophelia, 1758; a History of the Countess of Dellwyn, 1759; and a translation of the Memorabilia, entitled Xenophon’s Memoirs of Socrates, with the Defence of Socrates before his Judges, 1762. Harris is said to have corrected her translation.

Miss Fielding was one of Richardson’s coterie of female friends, and several letters from each are included in his correspondence. The eulogy quoted above was probably called forth by her own effusive admiration for the author of Pamela; indeed, David Simple itself, in spite of the satirical character of the earlier half, is in the main a novel in the true style of the great sentimentalist. When she offers to act as Richardson’s amanuensis, she writes with transports of enthusiasm. She would have found, she says, “all my thoughts strengthened, and my words flow into an easy and nervous style; never did I so much wish for it as in this daring attempt of mentioning Clarissa; but when I read of her, I am all sensation: my heart glows—I am overwhelmed—my only vent is tears.” In middle age she went to Bath, to take the waters, and ultimately settled down there. A few casual references are extant of her life in that city of fashion, gaiety and culture, at the time when Beau Nash was “King,” and Ralph Allen of Prior Park was playing Maecenas to many an author in distress. Alien is said to have allowed her an annuity of a hundred pounds. She died at Bath in 1768, and a monument was erected to her in the Abbey Church, bearing an inaccurate inscription and the following verses by Dr. John Hoadley —

Her unaffected manners, candid mind,

Her heart benevolent, and soul resign’d;

Were more her praise than all she knew or thought,

Though Athens’ wisdom to her sex she taught.

It would be unfair to criticize David Simple on its literary merits alone, without taking into account its historical position as an early novel. It was published a year before Tom Jones. Richardson had written Pamela, but not Clarissa Harlowe. The Vicar of Wakefield was still a long way off in the future, and so were the novels of Fanny Burney. Sterne’s Tristram Shandy was not published till 1759, fifteen years ahead; and four years were to elapse before Smollett’s first book, Roderick Random, was to see the light. Few books, in truth, that could with any sense of propriety be called novels, were in existence at the time when Miss Fielding sat down to write. Certainly, the masterpieces of Swift and Defoe were not novels in our sense of the word. Addison’s Sir Roger de Coverley Papers had far more of the stuff of which the novel of the future was to be made. In Addison there is the delineation of real life, the kindly humour, the delicate portraiture of the individual, which were to be the finest characteristics of the English novel of manners. There was also the element of satire, and it is as a satirist and a censor of society in the Addisonian style that, I think, Sarah Fielding may be most favourably regarded.

Her theme is friendship. The sentiments which she has expressed in the adventures of David, Cynthia and Camilla, and in the tender episode of Stainvllle and Dumont are, says Henry Fielding, with brotherly patronage, “as noble and elevated as I have anywhere met with . . . Nay, there are some touches, which I will venture to say, might have done honour to the pencil of the immortal Shakespeare himself.” Professor Wilbur L. Cross has summarized the literary tendency of the period that began with Pamela and ended with the publication of Humphry Clinker, in the following admirable terms: — “The novels of this period which have become a recognized part of our literature, whether they deal in minute incident as in Richardson and Sterne, or in farce, intrigue and adventure as in Smollett and Fielding, have one characteristic in common: their subject is the heart. Moreover, underlying them, as their raison d’être, is an ethical motive. Richardson makes the novel a medium for Biblical teaching as it is understood by a Protestant precisian; Fielding pins his faith on human nature; Smollett cries for justice to the oppressed; Sterne spiritualizes sensation, addressing ‘Dear Sensibility’ as the Divinity whom he adores.” But David Simple, though it belongs of right to the period, appeared at too early a date, when the school was yet unformed. Miss Fielding had no definite model before her, and was without the constructive skill to invent a suitable one. To set forth the admirable philosophy that underlies her criticism of society, and to portray ideal sentiments and characters, she could hardly have chosen a more unfortunate plan than that of the picaresque story, with its loosely linked episodes and motley succession of characters, as fortuitous in arrangement as the faces we meet with in the street. Nothing can be more clumsy than her introduction of dialogue, with the names of the interlocutors formally prefixed as in a play; nothing more perplexing than her stories within the story, and then again the story told at second or third hand, but still in the first person, of brothers, lovers and acquaintances, amid whose long- protracted speeches we are apt to lose the thread altogether. Nevertheless, this method did very well up to a certain point. David Simple, it is noticeable, falls into two parts; the earlier is critical and satirical in spirit, the second half devoted to the portraiture of ideal virtues and sentiments. Henry Fielding’s preface, which does ample justice to his sister’s powers of drawing individual character and expressing lofty emotion, is reprinted here. Let us turn to the other side of the work.

Every novelist of that period thought it was incumbent on him to have a moral purpose in his work, and most of them were pronouncedly and deliberately didactic. Richardson taught his morality directly, with a heavy seriousness; Fielding preferred the lighter and more ambiguous method of the satirist. His sister halted between the two courses. Her satire is lacking in the right spirit of comedy. It is rather the satire of the moral essayist than of the dramatist or the story-writer. But her wit, at its best, is wonderfully sane, discriminating, and caustic. She belongs to that highest type satirist who sees things not merely as related the fashions, mannerisms and prejudices of his own time and place, but in the dry light of abstract intelligence and perfect sanity. Let the following extracts, culled at haphazard and miscellaneous in subject, speak for themselves. Their insight into human nature, as her brother pointed out, is the more remarkable if we consider the narrowness of her experience.

“I never yet knew a man who did not hate the person who seemed not to have the same opinion of him as he had of himself; and, as that very seldom happens, I believe it is one of the chief causes of the malignity mankind have against one another.”

“He reflected that the customs and manners of nations relate chiefly to ceremonies, and have nothing to do with the hearts of men.”

“He took a new lodging every week, and always the first thing he did was to inquire of his landlady the reputation of all the neighbourhood: but he never could hear one good character from any of them; only every one separately gave very broad hints of their own goodness, and what pity it was they should be obliged to live amongst such a set of people.”

“And there for some time I will leave him to his own private sufferings—lest it should be thought I am so ignorant of the world, as not to know the proper time of forsaking people.”

“In short, from morning till night, they did nothing but quarrel; and there passed many curious dialogues between them, which I shall not here repeat: for, as I hope to be read by the polite world, I would avoid everything of which they can have no idea.”

“For, if by taking pains to bridle his passions, he could gain no superiority over his companions, all his love of rectitude, as he calls it, would fall to the ground. So that his goodness, like cold fruits, is produced by the dung and nastiness which surround it.”

“She spent some time in the deepest melancholy, and felt all the misery which attends a woman who has many things to wish, but knows not positively which she wishes most.”

“If he had but sighed, and been miserable for the loss of her, she could have married her old man without any great reluctance: but the thought that he had left her first was insupportable!”

“He never once reflected on what is perhaps really the case, that to prevent a husband’s surfeit or satiety in the matrimonial feast, a little acid is now and then very prudently thrown into the dish by the wife.”

“If, indeed, her reputation had been lost, and she had conversed long enough with a man to have worn out her youth and beauty, and had been left in poverty, and all kinds of distress, without any hopes of relief, her folly would have then been so glaring, he could by no means have owned her for his child.”

“John’s coldness and neglect; nay, his liking other women better than his wife, which no virtuous woman can possibly bear.”

“Lucretia herself (whose chastity nothing but the fear of losing her reputation could possibly have conquered).”

“The words genius, and no genius; invention, poetry, fine things, bad language, no style, charming writing, imagery, and diction, with many more expressions which swim on the surface of criticism, seemed to have been caught by those fishers for the reputation of wit, though they were entirely ignorant what use to make of them, or how to apply them properly.”

“He was not of the opinion, that the more ignorant a man is of any subject, the more necessary it is to talk of it.”

Her satire of the amateur critic is always keen. One of the most entertaining chapters in the book is that relating the conversation of a number of fine ladies on the subject of pathos on the stage. It is amusing to find that some literary historians have not perceived the irony of the passage, and so have done less than justice to Miss Fielding’s critical acumen.

“Fourth Lady. There is nothing so surprising to me as the absurdity of almost everybody I meet with; they can’t even laugh or cry in the right place. Perhaps it will be hardly believed, but I really saw people in the boxes last night, at the tragedy of Cato, sit with dry eyes, and show no kind of emotion, when that great man fell on his sword; nor was it at all owing to any firmness of mind, that made them incapable of crying neither, for that I should have admired: but I have known those very people shed tears at George Barnwell.

“A good many Ladies speak at one time. Oh, intolerable I cry for an odious apprentice-boy, who murdered his uncle at the instigation too of a common woman, and yet be unmoved, when even Cato bled for his country.

Old Lady. That is no wonder, I assure you, ladies; for I once heard my Lady Know-all positively affirm George Barnwell to be one of the best things that ever was wrote: for that nature is nature in whatever station it is placed; and that she could be as much affected with the distress of a man in low life, as if he was a lord or a duke. And what is yet more amazing is, that the time she chooses to weep most, is just as he has killed the man who prays for him in the agonies of death; and then only, because he whines over him, and seems sensible of what he has done, she must shed tears for a wretch whom everybody of either sense or goodness, would wish to crush, and make ten times more miserable than he is.”

I conclude with two remarkable analyses of types of character, that would have done honour to Addison. The second, moreover, is charming, and warrants the saying of some person who replied to the objection that David Simple could not possibly be the work of a woman, by retorting that no man could have written it.

“You are to know, sir, there are a set of men in the world, who pass through life with very good reputations, whose actions are in the general justly to be applauded, and yet upon a near examination their principles are all bad, and their hearts hardened to all tender sensations. Mr. Orgueil is exactly one of those sort of men; the greatest sufferings which can happen to his fellow-creatures, have no sort of effect upon him, and yet he very often relieves them; that is, he goes just as far in serving others as will give him new opportunities of flattering himself; for his whole soul is filled with pride, he has made a god of himself, and the attributes he thinks necessary to the dignity of such a being, be endeavours to have. He calls all religion superstition, because he will own no other deity; he thinks even obedience to the Divine Will, would be but a mean motive to his actions; he must do good, because it is suitable to the dignity of his nature; and shun evil, because be would not be debased as low as the wretches he every day sees.”

“Thus ended this dialogue; in which vanity seemed to have had a fair chance of gaining the victory over love; or, in other words, where a young lady seemed to promise herself more pleasure from the purse than the person of her lover, And I hope to be excused by those gentlemen who are quite sure they have found one woman, who is a perfect angel, and that all the rest are perfect devils, for drawing the character of a woman who was neither; for Miss Nanny Johnson was very good-humoured, had a great deal of softness, and had no alloy to these good qualities, but a great share of vanity, with some small spices of envy, which must always accompany it. And I make no matter of doubt, but if she had not met with this temptation, she would have made a very affectionate wife to the man who loved her: he would have thought himself extremely happy, with a perfect assurance that nothing could have tempted her to abandon him. And when she had had the experience, what it was to be constantly beloved by a man of Mr. Simple’s goodness of heart, she would have exulted in her own happiness, and been the first to have blamed any other woman for giving up the pleasure of having the man she loved for any advantage of fortune; and would have thought it utterly impossible for her ever to have been tempted to such an action; which then might possibly have appeared in the most dishonourable light: for to talk of a temptation at a distance, and to feel it present, are two such very different things, that everybody can resist the one, very few people the other.”

Ernest A. Baker.

Part II

Preface

BY THE AUTHOR OF “TOM JONES”

As so many worthy persons have, I am told, ascribed the honour of this performance to me, they will not be surprised at seeing my name to this preface; nor am I very insincere, when I call it an honour; for if the authors of the age are amongst the number of those who conferred it on me, I know very few of them to whom I shall return the compliment of such a suspicion.

I could indeed have been very well content with the reputation, well knowing that some writings may be justly laid to my change, of a merit greatly inferior to that of the following work; had not the imputation directly accused me of falsehood, in breaking a promise, which I have solemnly made in print, of never publishing, even a pamphlet, without setting my name to it: a promise I have always hitherto faithfully kept; and, for the sake of men’s characters, I wish all other writers were by law obliged to use the same method; but, till they are, I shall no longer impose any such restraint on myself.

A second reason which induces me to refuse this untruth, is, that it may have a tendency to injure me in a profession, to which I have applied with so arduous and intent a diligence, to compose anything of this kind. Indeed, I am very far from entertaining such an inclination; I know the value of the reward

which fame confers on authors, too well, to endeavour any longer to obtain it; nor was the world ever more unwilling to bestow the glorious, envied prize, of the laurel or bays, than I should now be to receive any such garland or fool’s cap. There is not, I believe (and it is bold to affirm) a single free Briton in this kingdom, who hates his wife more heartily than I detest the muses. They have, indeed, behaved to me like the most infamous harlots; and have laid many a spurious, as well as deformed production at my door: in all which, my good friends the criticks have, in their profound discernment, discovered some resemblance of the parent; and thus I have been reputed and reported the author of half the scurrility, bawdy, treason, and blasphemy, which these last few years have produced.

I am far from thinking every person who hath thus aspersed me, had a determinate design of doing me an injury; I impute it only to an idle, childish levity, which possesses too many minds, and makes them report their conjectures as matters of fact, without weighing the proof, or considering the consequence. But as to the former of these, my readers will do well to examine their own talents very strictly, before they are too thoroughly convinced of their abilities to distinguish an author’s style so accurately, as from that only to pronounce an anonymous work to be his: and, as to the latter, a little reflection will convince them of the cruelty they are guilty of by such reports. For my own part, I can aver, that there are few crimes of which I should have been more ashamed, than of some writings laid to my charge. I am as well assured of the injuries I have suffered from such unjust imputations, not only in general character; but as they have, I conceive, frequently raised m inveterate enemies, in persons to whose disadvantage I have never entertained a single thought; nay, in men whose characters, and even names, have been unknown to me.

Among all the scurrilities with which I have been accused (though equally and totally innocent of every one) none ever raised my indignation so much as the Causidicade: this accused me not only of being a bad writer, and a bad man; but with downright idiotism, in flying in the face of the greatest men of my profession. I take, therefore, this opportunity to protest, that I never saw that infamous, paultry libel, till long after it had been in print; nor can any man hold it in greater contempt and abhorrence than myself.

The reader will pardon my dwelling so long on this subject, as I have suffered so cruelly by these aspersions in my own ease, in my reputation, and in my interest. I shall, however, henceforth treat such censure with the contempt it deserves; and do here revoke the promise I formerly made; so that I shall now look upon myself at full liberty to publish an anonymous work, without any breach of faith. For though probably I shall never make any use of this liberty, there is no reason why I should be under a restraint for which I have not enjoyed the purposed recompense.

A third, and indeed the strongest reason which hath drawn me into print, is to do justice to the real and sole author of this little book; who, notwithstanding the many excellent observations dispersed through it, and the deep knowledge of human nature it discovers, is a young woman; one so nearly and dearly allied to me, in the highest friendship as well as relation, that if she had wanted any assistance of mine, I would have been as ready to have given it her, as I would have been just to my word in owning it: but, in reality, two or three hints which arose on the reading of it, and some little direction as to the conduct of the second volume, much the greater part of which I never saw till in print, were all the aid she received from me. Indeed, I believe there are few books in the world so absolutely the author’s own as this.

There were some grammatical and other errors in style in the first impression, which my absence from town prevented my correcting, as I have endeavoured though in great haste, in this edition: by comparing the one with the other, the reader may see, if he thinks it worth his while, the share I have in this book, as it now stands, and which amounts to little more than the correction of some small errors, which want of habit in writing chiefly occasioned, and which no man of learning would think worth his censure in a romance; nor any gentlemen, in the writings of a young woman.

And as the faults of this work want very little excuse, so its beauties want as little recommendation: though I will not say but they may sometimes stand in need of being pointed out to the generality of readers. For as the merit of this work consists in a vast penetration into human natures, a deep and profound discernment of all the mazes, windings, and labyrinths, which perplex the heart of man to such a degree, that he is himself often incapable of seeing through them; and as this is the greatest, noblest, and rarest, of all the talents which constitute a genius, so a much larger share of this talent is necessary, even to recognize these discoveries, when they are laid before us, than falls to the share of a common reader. Such beauties, therefore, in an author, must be contented to pass often unobserved and untasted; whereas, on the contrary, the imperfections of this little book, which arise, not from want of genius, but of learning, lie open to the eyes of every fool who has had a little Latin inoculated into his tail; but had the same great quantity of birch been better employed, in scourging away his ill-nature, he would not have exposed it in endeavouring to cavil at the first performance of one, whose sex and age entitle her to the gentlest criticism, while her merit, of an infinitely higher kind, may defy the severest. But I believe the warmth of ray friendship hath led me to engage a critick of my own imagination only, for I should be sorry to conceive such a one had any real existence. If, however, any such composition of folly, meanness, and malevolence, should actually exist, he must be as incapable of conviction, as unworthy of an answer. I shall, therefore, proceed to the more pleasing task of pointing out some of the beauties of this little work.

I have attempted, in my preface to Joseph Andrews, to prove, that every work of this kind is in its nature a comick epick poem, of which Homer left us a precedent, though it be unhappily lost.

The two great originals of a serious air, which we have derived from that mighty genius, differ principally in the action, which in the Iliad is entire and uniform; in the Odyssey, is rather a series of actions, all tending to produce one great end. Virgil and Milton are, I think, the only pure imitators of the former: most of the other Latin, as well as Italian, French, and English epick poets, chusing rather the history of some war, as Lucan, and Silius Italicus; or a series of adventures, as Ariosto, etc, for the subject of their poems.

In the same manner, the comick writer may either fix on one action, as the authors of Le Lutrin, the Dunciad, etc., or on a series, as Butler in verse, and Cervantes in prose, have done.

Of this latter kind is the book now before us; where the fable consists of a series of separate adventures, detached from and independent on each other, yet all tending to one great end: so that those who should object to want of unity of action here, may, if they please, or if they dare, fly back with their objection, in the face of even the Odyssey itself.

This fable hath in it these three difficult ingredients which will be found on consideration to be always necessary to works of this kind, viz. that the main end or scope be at once amiable, ridiculous, and natural.

If it be said, that some of the comick performances I have above mentioned differ in the first of these, and set before us the odious, instead of the amiable; I answer, that is far from being one of their perfections; and of this the authors themselves seem so sensible, that they endeavour to deceive their reader by false glosses and colours; and, by the help of irony at least, to represent the aim and design of their heroes in a favourable and agreeable light.

I might farther observe, that, as the incidents arising from this fable, though often surprising, are everywhere natural (credibility not being once shocked through the whole) so there is one beauty very apparent, which hath been attributed by the greatest of criticks to the greatest of poets; that every episode bears a manifest impression of the principal design, and chiefly turns on the perfection or imperfection of friendship; of which noble passion, from its highest purity to its lowest falsehoods and disguises, this little book is, in my opinion, the most exact model.

As to the characters here described, I shall repeat the saying of one of the greatest men of this age, “That they are as wonderfully drawn by the writer, as they were by nature herself.” There are many strokes in Orgueil, Spatter, Varnish, Le Vif, the Balancer, and some others, which would have shined in the pages of Theophrastus, Horace, or La Bruyere. Nay, there are some touches, which I will venture to say, might have done honour to the pencil of the immortal Shakespeare himself.

The sentiments are in general extremely delicate; those particularly which regard friendship, are, I think, as noble and elevated as I have anywhere met with: nor can I help remarking, that the author had been so careful in justly adapting them to her characters, that a very indifferent reader, after he is in the least acquainted with the character of the speaker can seldom fail of applying every sentiment to the person who utters it. Of this we have the strongest instance in Cynthia and Camilla, where the lively spirit of the former, and the gentle softness of the latter, breathe through every sentence which drops from either of them.

The diction I shall say no more of, than as it is the last and lowest perfection in a writer, and one which many of great genius seem to have little regarded, so I must allow my author to have the least merit on this head: many errors in style existing in the first edition, and some, I am convinced, remaining still uncured in this; but experience and habit will most certainly remove this objection; for a good style, as well as a good hand in writing, is chiefly learned by practice.

I shall here finish these short remarks on this little book, which have been drawn from me by those people, who have very falsely and impertinently called me its author; I declare I have spoken no more than my real sentiments of it, nor can I see with any relation or attachment to merit should restrain me from its commendation.

The true reason why some have been backward in giving this book its just praise, and why others have sought after some more known and experienced author for it, is, I apprehend, no other, than an astonishment how one so young, and in appearance unacquainted with the world, should know so much both of the better and worse part, as is here exemplified: but, in reality, a very little knowledge of the world will afford an observer, moderately accurate, sufficient instances of evil; and a short communication with her own heart will leave the author of this book very little to seek abroad of all the good which is to be found in human nature.

Henry Fielding.

Dramatis Personae

David Simple, elder son and rightful heir of Daniel Simple, mercer of Ludgate Hill.

Daniel Simple, his wicked brother.

John and Peggy: two servants suborned by Daniel to witness the forged will disinheriting his brother.

Mr. Johnson, a jeweller.

His elder daughter, who marries a rich Jew.

Nancy, his second daughter, who jilts David and marries Mr. Nokes

Betty Trusty, her maid.

A Carpenter, who extols his ugly and lazy spouse as the best wife in the world.

Another man, with a patient and industrious wife, whom he abuses.

Mr. Orgueil, the censorious critic, who introduces David to the various sorts of life in London.

Mr. Spatter, who introduces David to the fashionable coteries, and pulls to pieces, ridicules and abuses all the people they meet with.

Mr. Varnish, who sings the praises of everybody, and has ”the appearance of good-nature, but is not at all affected with the sufferings of others.”

Lady_________Cynthia’s tyrannical protectress.

Cynthia, an unfortunate young lady, loved by David. “After being hated by her family as a wit (she) is insulted as a fool by her patroness.”

The Earl of_________Lady_________’s nephew, who proposes to Cynthia.

Valentine, an unfortunate young man. befriended by David.

Camilla, his more unfortunate sister, whom David loves.

Mr._________, their father, deceived by Livia.

Livia, his second wife, whose beauty belies her odious disposition, and who drives Valentine and Camilla from their father’s house by her remorseless persecution.

A Clergyman, An Atheist, A Butterfly “as he had neither profession nor characters, I know not what other name to give him”, Cynthia’s fellow-travellers in the coach.

The Marquis of Stainville, a chivalrous French gentleman.

Isabelle, another unfortunate young lady, his sister.

Julie, her friend, a passionate girl, who dies of a broken heart.

Monsieur Le Buisson, who loves Isabelle, and is loved by Julie.

The Chevalier Dumont, a French Adonis, irresistible to the ladies, but of invincible virtue; Stainville’s friend.

Monsieur Le Neuf, a villainous friend of Stainville and Dumont.

Dorimene, Stainville’s wife, who falls uncontrollably in love with Dumont.

The Comte de_________, her father.

Vieuville, Dorimene’s brother. He is madly in love with Isabelle, but fortunately falls still more madly in love with some one else.

Pandolph, an old servant of Stainville’s.

Sacharissa and Corinna Two English young ladies at Paris, whose contrasts of character point the moral of Cynthia’s story.

Monsieur Le Vive, a man who always acts according to his passions.

The Balancer, a man who finds every act in life as difficult as an abstruse mathematical problem.

Part III

BOOK I

I

THE BIRTH, PARENTAGE, AND EDUCATION OF MR. DAVID SIMPLE

Mr. David Simple was the eldest son of Mr. Daniel Simple, a mercer on Ludgate Hill. His mother a downright country woman, who originally got her living by plain work; but being handsome, was liked by Mr. Simple. When or where this couple met, or what happened to them during their courtship, is foreign to my present purpose, nor do I really know. But they were married, and lived many years together, a very honest and industrious life; to which it was owing, that they were able to provide very well for their children. They had only two sons, David and Daniel, who, as soon as capable of learning, were sent to a public school, and kept there in a manner which put them on a level with boys of a superior degree, and they were respected equally with those born in the highest station. This indeed their behaviour demanded; for there never appeared anything mean in their actions, and nature had given them parts enough to converse with the most ingenious of their school-fellows. The strict friendship they kept up was remarked by the whole school; who ever affronted the one, made an enemy of the other; and while there was any money in either of their pockets, the other was never to want it: the notion of whose property it was, being the last thing that ever entered into their heads. The eldest, who was of a sober, prudent disposition, had always enough to supply his brother, who was much more profuse in his expenses; and I have often heard him say (for this history is all taken from his own mouth) that one of the greatest pleasures he ever had in his life, was in the reflections he used to make at that time, that he was able to supply and assist his dear brother; and whenever he saw him but look as if he wanted anything, he would immediately bring out all the money he had, and desire him to take whatever he had occasion for. On the other hand, Daniel was in some respects useful to him; for although he had not half the real understanding or parts, yet he was what the world calls a much sharper boy; that is, he had more cunning, and consequently being more suspicious, would often keep his brother from being imposed on; who, as he was too young to have gained much experience, and never had any ill designs on others, never thought of their having any upon him. He paid a perfect deference to his brother’s wisdom; from finding, that whenever he marked out a boy as one that would behave ill, it always proved so in the end. He was sometimes, indeed, quite amazed how Daniel came by so much knowledge; but then his great love and partiality to him easily made him impute it to his uncommon sagacity, and he often pleased himself with the thoughts of having such a brother.

Thus these two brothers lived together at school in the most perfect unity and friendship, till the eldest was seventeen, at which time they were sent for from school, on their father’s being seized with a violent fever. He recovered of that distemper, but it weakened him so much, that he fell into a consumption, in which he lingered a twelvemonth, and then died. The loss of so good a father was sensibly felt by the tender-hearted David; he was in the utmost affliction, till by philosophical considerations, assisted by a natural calmness he had in his own temper, he was enabled to overcome his grief, and began again to enjoy his former serenity of mind. His brother, who was of a much gayer disposition, soon recovered his spirits; and the two brothers seemed to be getting into their former state of happiness, when it was interrupted by the discovery of something in Daniel’s mind, which to his fond brother had never appeared there before; and which, whoever thinks proper to read the next chapter, may know.

II

IN WHICH ARE SEEN THE TERRIBLE CONSEQUENCES WHICH ATTEND ENVY AND SELFISHNESS

It will perhaps surprise the reader as much as it did poor David, to find that Daniel, notwithstanding the appearance of friendship he had all along kept up with his brother, was in reality one of those wretches, whose only happiness centres in themselves; and that his conversation with his companions had never any other view, but in some shape or other to promote his own interest. To this was owing his endeavour to keep David from being imposed on, lest his generosity should lead him to let others share his money as well as himself: from this alone arose his character of wisdom; for he could easily find out an ill-disposed mind in another, by comparing it with what passed in his own bosom. While he found it for his benefit to pretend to the same delicate way of thinking and sincere love which David had for him, he did not want art enough to affect it; but as soon as he thought it his interest to break with his brother, he threw off the mask, and took no pains to conceal the baseness of his heart.

From the time they came from school, during the old gentleman’s illness, Daniel’s only study was how he should throw his brother out of his share of his father’s patrimony, and engross it wholly to himself. The anxious thoughts he appeared continually in, on this account, were imputed by his good-natured friend to a tender concern for a parent’s suffering; a consideration which much increased his love for him. His mother had a maid, whom Mr, Daniel had a great fancy for; but she being a virtuous woman (and besides having a sweet-heart in her fellow-servant, whom she liked much better) resisted all his solicitations, and would have nothing to say to him. But yet he found she could not refuse any little presents he made her; which convinced him she was very mercenary, and made him think of a scheme to make her serve his designs of another kind, since she would not be subservient to his pleasures. He knew his father had given a sealed paper to his brother, which he told him was his will, with strict orders not to open it till after his death; and as he was not ignorant where David had put it, he formed a scheme to steal away the real will, and to put a forged one in its place. But then he was greatly puzzled what he should do for witnesses; which, as he had slily pumped out of an ingenious young gentleman his acquaintance, who was a clerk to an attorney, were necessary to the signing a will. He therefore thought, if he could bribe this girl and her sweetheart for this purpose, he should accomplish all he desired; for, as the same learned lawyer had told him, two witnesses were sufficient, where the estate was only personal, as that of his father’s was. This young woman was one of those sort of people who had been bred up to get her living by hard work; she had been taught never to keep company with any man, but him she intended to marry; nor to get drunk, or steal; for if she gave way to those things (besides that they were great sins), she would certainly come to be hanged; which, as she had an utter aversion to, she went on in an honest way, and never intended to depart from it.

Our spark, when first he thought of making use of her, was very much afraid, lest she should refuse, and betray him. But when he reflected how impossible it would be for him to refuse anything he thought valuable, though he was to be guilty of ever so much treachery to obtain it, he resolved boldly to venture on the trial. When he first spoke to her about it, he offered her fifty pounds, but she was so frightened at the thoughts of being accessory to a forgery, that she declared she would not do it for the whole world; for that she had more value for her precious soul than for anything he could give her; that as to him, he was a schollard, and might think of some way of saving himself; but as she could neither write nor read, she must surely be d—d. This way of talking so thoroughly convinced Daniel of her folly that he made no doubt of soon gaining her to his purpose. He, therefore, made use of all the most persuasive arguments he could think of; and, amongst the rest, he told her that by this means she might marry the man she liked, and live with him in a very comfortable manner. He immediately perceived this staggered all her resolutions; and as soon as he saw she could moved did not fear succeeding. He pulled out his pocket a purse with a hundred guineas, and told them out before her (for the sight of money is much more prevalent than the idea of it), and assured her, that he would be better than he had promised her; for if she would comply with his request, the whole sum she had seen should be hers, and that she and her lover by this means would be enabled to live in a manner much above all the maids she used to converse with. The thoughts of being set above her acquaintance quite overcame her; and, as she had never been mistress of above forty shillings at a time, a hundred guineas appeared such an immense sum, that she easily conceived she could live very well, without being obliged to work any more. This prospect so charmed her, that she promised to do whatever he would have her. She did not doubt but she could make her sweetheart comply, for he had never refused her anything since their acquaintance began. This made Daniel quite happy, for everything else was plain before him. He had no scruple on the fellow’s account; for, once get the consent of a woman, and that of a man (who is vulgarly called in love with her) consequently follows; for though a man’s disposition is not naturally bad, yet it is not quite certain he will have resolution enough to resist a woman’s continual importunities.

Daniel took the first opportunity (which quickly offered, everything being common between him and his brother) of stealing the will. As it was in his father’s hand, he could easily forge it, for he wrote very like him; when he had done this, he had it witnessed in form, placed it in the room of the other, and then went away quite satisfied in the success of his scheme.

The real affliction of David, on the old gentleman’s death, prevented his immediate thinking of his will. And Daniel was forced to counterfeit what he did not feel, not daring to be eager for the opening it, lest when the contents were known the truth should be suspected. But as soon as the first grief was a little abated, and the family began to be calmed, David desired his mother and brother to walk upstairs; then went to his bureau, and took out the will; and read it before them. The contents were as follows: Daniel was left sole executor; that out of £11,000 which was the sum left, he should pay his mother £60 per annum, and that David should have £500 for his fortune. They all stood speechless for some time, staring at each other. At last David broke silence, and embracing Daniel, said, “I hope my dear brother will not impute my amazement to any concern I have, that he has so much the largest share of my father’s fortune. No, I do assure you, the only cause of my uneasiness is fearing I have done anything to disoblige my father, who always behaved with so much good nature to me, and made us both so equal in his care and love, that I think he must have had some reason for this last action of leaving me so small a matter, especially as I am the eldest.”

Here Daniel interrupted him, and began to swear and bluster. He said that his father must have been told some wicked lies of his brother, and he was resolved to find out the vile incendiary. But David begged him to be pacified, and assured him he thought of it without concern; for he knew him too well to suspect any alteration in his behaviour, and did not doubt that everything would be in common amongst them as usual: nay, so tenderly and affectionately did he love Daniel, that he reflected with pleasure how extremely happy his life must be in continually sharing with his best friend the fortune his father had left him. Thus would he have acted, and his honest heart never doubted but that his brother’s mind was like his own. Daniel answered him with asseverations of his always commanding everything equally with himself. The good old woman blessed herself for having two such sons, and they all went downstairs in very good humour.

Daniel had two reasons for allotting his mother something; one was that nothing but a jointure could have barred her coming in for thirds the other was, that if no notice had been taken of her in the will, it might have been a strong motive for suspicion; not that he had any great reason for caution, as nothing less than seeing him do it could have made David such confidence had he in him) even suspect he could be guilty of such an action.

The man and maid were soon married; and as they had long lived in the family, David gave them something to set up with. This was thought very lucky by the brother, as it might prevent any suspicions how they came by money. Thus everything succeeded to Daniel’s mind, and he had compassed all his designs without any fear of a discovery.

The two brothers agreed on leaving off their father’s business, as they had enough to keep them; and as their acquaintance lay chiefly in that neighbourhood, they took a little house there. The old gentlewoman, whose ill-health would not suffer her to live in London, retired into the country, and lived with her sister.

David was very happy in the proofs he thought he had of his brother’s love; and as it was his nature to be easily contented, he gave very little trouble or expense to the family. Daniel hugged himself in his ingenuity, and in the thoughts how impossible it would have been for him to have been so imposed on. His pride (of which he had no small share) was greatly gratified in thinking his brother was a dependant on him; but then he was resolved it should not be long before he felt that dependance, for otherwise the greatest part of his pleasure must be lost. One thing quite stung him to the quick, viz., that David’s amiable behaviour, joined to a very good understanding, with a great knowledge which he had attained by books, made all their acquaintance give him the preference: and as envy was very predominant in Daniel’s mind, this made him take an utter aversion to his brother, which all the other’s goodness could not get the better of, for as his actions were such as he could not but approve, they were still greater food for his hatred; and the reflection that others approved them also, was what he could not bear. The first thing in which David discovered an alteration in his brother, was in the behaviour of the servants; for as they are always very inquisitive, they soon found out by some means or other, that Daniel was in possession of all the money, and was not obliged to let his brother share it with him. They watched their master’s motions, and as soon as they found that slackening in their respect to David would not be displeasing to the other, it may easily be believed they were not long in doubt whether they should follow their own interest: so that at last, when David called them, they were always going to do something for their master—truly, while he wanted them, they could not wait on any body else! Daniel took notice of their behaviour, and was inwardly pleased at it. David knew not what to make of it: he would not mention it to his brother, till it grew to such a height he could bear it no longer; and when he spoke of it to Daniel, it was only by way of consulting with him how to turn them away. But how great was his surprize, when Daniel, instead of talking in his usual style, said, that for his part he saw no fault in any of his servants! that they did their duty very well, and that he should not part with his own conveniencies for anybody’s whims! If he accused any of them of a fault, he would call them up, and try if they could not justify themselves. David was at first struck dumb with amazement; he thought he was not awake, that it was impossible it could be his brother’s voice which uttered these words: but at last he recollected himself enough to say, “What, is it come to this? Am I brought to a trial with your servants, (as you are pleased to call them?) I thought we had lived on different terms. Oh! recall those words, and don’t provoke me to say what perhaps I shall afterwards repent!” Daniel knew, that although his brother was far from being passionate for trifles, yet that his whole frame would be so shaken from any ill usage from him, he would not be able to command himself: he resolved, therefore, to take this opportunity of aggravating his passion, till it was raised to an height, which, to the unthinking world, would make him appear in the wrong; he therefore very calmly answered, “You may do as you please, brother; but what you utter appears to me to be quite madness; I don’t perceive but you are used in my house as well as I am myself, and cannot guess what you complain of. If you are not contented, you best know how to find a remedy; many a brother, in your case, I believe, would think himself very happy to meet with the usage you have, without wanting to make mischief in families.” This had the desired effect, and threw David into that inconsistent behaviour, which must always be produced in a mind torn at once by tenderness and rage. That sincere love and friendship he had always felt for his brother made his resentment the higher, and he alternately fired into reproaches, and melted into softness; till at last he swore he would go out of the house, and never more visit the place, which was in the possession of so unnatural a wretch.

Daniel had now all he wanted; from the moment the other’s passion grew loud, he had set open the door, that the servants might hear how he used him, and be witnesses he was not in fault. He behaved with the utmost calmness; which was very easy for him to do, as he felt nothing. He said, his brother should be always welcome to live in his house, provided he could be quiet, and contented with what was reasonable; and not be so mad as to think, while he insisted only on the management of his own family, he departed from that romantic love he so often talked of. Indeed, it must be confessed, that if David would have been satisfied to have lived in his brother’s house in a state of dependency; to have walked about in a rusty coat, and an old tye-wig, like a decayed gentleman, thinking it a favour to have bread, while every visitor at the house should be extolling the goodness of his brother for keeping him; I say, could he have been contented with this sort of behaviour, he might have stayed there as long as he pleased. But Daniel was resolved he should not be on a level with him, who had taken so much pains to get a superior fortune; he therefore behaved in this manner, with design either to get rid of him, or make him submit to his terms. This latter it was impossible ever to accomplish: for David’s pride would not have prevented his taking that usage from a stranger, but his love could by no means suffer him to bear it from his brother. Therefore, as soon as the variety of passions he struggled with would give him leave, he told him, that since he was so very different from what he had always thought him, and capable of what he esteemed the greatest villainy, he would sooner starve than have anything more to say to him. On which he left him and went up to his own chamber, with a fixed resolution to leave the house that very day, and never return to it any more.

It would be impossible to describe what he felt when he was alone: all the scenes of pleasure he had ever enjoyed in his brother’s company rushed at once into his memory; and when he reflected on what had just happened, he could not account for such a difference in one man’s conduct. He was sometimes ready to blame himself, and thought he must have been guilty of something in his passion (for he hardly remembered what he had said) to provoke his brother to such a behaviour: he was then going to seek him to be reconciled to him. But when he considered the beginning of the quarrel, and what Daniel had said to him concerning the servants, he concluded he must be tired of his company, and from some motive or other had altered his affection. Then several little slights came into his head, which he had overlooked at the time of their happening; and from all these reflections, he concluded he could have no further hopes from his brother. However, he resolved to stay in his room till the evening, to see if there yet remained tenderness enough in Daniel to induce him to endeavour the removing his present torment. What he felt during that interval, is not to be expressed or understood, but by the few who are capable of real tenderness; every moment seemed an age. Sometimes, in the confusion of his thoughts, the joy of being again well with his brother appeared so strong to his imagination, he could hardly refrain going to him; but when he found it grew late, and no notice was taken of him, not even so much as a summons to dinner, he was then certain any condescension on his side would only expose him to be again insulted; he therefore resolved to stay there no longer.

When he went downstairs, he asked where his brother was, and was told, he went out to dinner with Mr. _________, and had not been at home since. He was so struck with the thought that Daniel could have so little concern for him, as to go into company and leave him in such misery, he had hardly strength enough left to go any farther; however, he got out of the house as fast as he was able, without considering whither he was going, or what he should do; for his mind was so taken up, and tortured with his brother’s brutality, that all other thoughts quite forsook him. He wandered up and down till he was quite weary and faint, not knowing whither to direct his steps. When he first set out, he had but half-a-crown in his pocket, a shilling of which he gave away in his walk to a beggar, who told him a story of having been turned out of doors by an unnatural brother: so that now he had but one shilling and sixpence left, with which he went into a public house, and got something to recruit his worn-out spirits. In his situation, anything that would barely support nature, was equal to the greatest dainties; for his mind was in so much anxiety it was impossible for him to spend one thought on any thing but the cause of his grief. So true is that observation of Shakespeare’s, “When the mind is free, the body is delicate”; that those people know very little of real misery (however the sorrow for their own sufferings may make them imagine no one ever endured the like) who can be very solicitous of what becomes of them. But this was far from being our hero’s case, for when he found himself too weak to travel farther, he was obliged to go into a public house; for being far from home, and an utter stranger, no private house would have admitted him. As soon as he got into a room, he threw himself into a chair, and could scarce speak. The landlord asked him, what he would please to drink; but he not knowing what he said, made answer, he did not choose any thing. Upon which he was answered in a surly manner, if he did not care for drinking, he could have no great business there, and would be very welcome to walk out again. This treatment just roused him enough to make him recollect where he was, and that he must call for something; therefore he ordered a pint of beer to be brought, which he immediately drank off, for he was very dry, though his griefs were so fixed in his mind, he could not feel even hunger or thirst. But nature must be refreshed by proper nourishment, and he found himself now not so faint, and seemed inclined to sleep; he therefore enquired for a bed; which his kind landlord (on his producing money enough to pay for it) immediately procured for him; and being perfectly overcome with fatigue and trouble, he insensibly sunk to rest.

In the morning when he waked, all the transactions of the preceding day came fresh into his mind; he knew not which way to turn himself, but lay in the greatest perplexity for some time; at last, it came into his head he had an uncle, who, when he was a boy, used to be very kind to him; he therefore had some hopes he would receive and take care of him. He got up, and walked as well as he was able to his uncle’s house. The good old man was quite frightened at the sight of him; for the one day’s extreme misery he had suffered, had altered him as much as if he had been ill a twelve-month, His uncle begged to know what was the matter with him; but he would give him no other answer, but that his brother and he had had a few words (for he would not complain); and he desired he would be so kind to let him stay with him a little while, till matters could be brought about again. His uncle told him, he should be very welcome. And there for some time I will leave him to his own private sufferings— lest it should be thought I am so ignorant of the world, as not to know the proper time of forsaking people.

III

IN WHICH IS SEEN THE POSSIBILITY OF A MARRIED COUPLE’S LEADING AN UNEASY LIFE

Mutual fondness, and the desire of marrying with each other, had prevailed with the two servants, who were the cause of poor David’s misfortunes, and the engines of Daniel’s treachery, to consent to an action which they themselves feared they should be d—n’d for; but this fond couple had not long been joined together in the state of matrimony, before John found out, that Peggy had not all those perfections he once imagined her possessed of; and her merit decreased every day more and more in his eyes. However, while the money lasted, (which was not very long, for they were not at all scrupulous of using it, thinking such great riches were in no danger of being brought to an end) between upbraidings, quarrels, reconciliations, kissing, and falling out, they made a shift to jumble on together, without coming to an open rupture. But the money was no sooner gone, than they grew out of all patience. When John began to feel poverty coming upon him, and found all he had got by his villainy was a wife, whom he now was heartily weary of, his conscience flew in his face, and would not let him rest. All the comfort he had left, was in abusing Peggy: he said she had betrayed him, and he should have been always honest, had it not been for her wheedling. She, on the other hand, justified herself, by alleging, nothing but her love for him could have drawn her into it; and if he thought it so great a crime, as he was a man, and knew better than her, he should not have consented, or suffered her to do it. For though I dare say this girl had never read Milton, yet she could act the part of throwing the blame on her husband, as well as if she had learned it by heart. In short, from morning till night, they did nothing but quarrel; and there passed many curious dialogues between them, which I shall not here repeat; for, as I hope to be read by the polite world, I would avoid every thing of which they can have no idea. I shall therefore only say in general, that between the stings of their consciences, the distresses from poverty, John’s coldness and neglect; nay, his liking other women better than his wife, which no virtuous woman can possibly bear; and Peggy’s uneasiness and jealousy; this couple led a life very little to be envied. But this could not last long; for when they found it was impossible for them to subsist any longer without working, they resolved to go into separate services: for they were now as eager to part, as they had formerly been to come together.

They were forming this resolution when they heard Mr. David was gone from his brother’s house on a violent quarrel. This separation had made a general discourse, and people said—it was no wonder, for it was impossible anybody could live in the house with him; for he was of such a temper that he fell out with his brother, for no other reason than because he would not turn away all his servants to gratify his humours! For although Mr. Daniel had all the money, yet he was so good to keep him; and sure, when people are kept upon charity they need not be so proud, but be glad to be contented without setting a gentleman against his servants! The old gentleman, his father, knew what he was, or he would have left him more!

When John heard all this he was struck with amazement and the wickedness he had been guilty of appeared in so horrible a light that he was almost mad. At first he thought he would find Mr. David out, and confess the whole truth: they had lived in the same house a great while and John knew him to be so mild and gentle that he flattered himself he might possibly obtain his forgiveness; but then the fear of shame worked so violently, that he despaired of mustering sufficient spirits to go through the story. The struggle in his mind was so great, he could not fix on what to determine; but the same person who had drawn him into this piece of villainy occasioned at last the discovery; for his wife intreated him with all the arguments she could think of not to be hanged voluntarily, when there was no necessity for it, for although the action they had done was not right, yet, thank God, they had not been guilty of murder. Indeed, if that had been the case there would have been a reason for confessing it, because it could not have been concealed, for murder will out; the very birds of the air will tell of that: but as they were in no danger of being found out it would be madness to run their necks into a halter.

John, who was ruined by his compliance with this woman while he liked her, since he was weary of and hated her, took hold of every opportunity to contradict her. Therefore, her eagerness to keep their crime a secret, joined to his own remorse, determined him to let Mr. David know it. However, he dissembled with her for the present lest she should take any steps to obstruct his designs.

He immediately began to inquire where Mr. David was gone, and when he was informed he was at his uncle’s he went thither and asked for him; but a servant told him Mr. David was indeed there but so ill he could not be spoke with. However, if the business was of great consequence, he would call his master, but disclosing it to himself would do as well. John answered what he had to say could be communicated to nobody but to Mr. David himself. He was so very importunate to see him that at last, by the uncle’s consent, he was admitted into his chamber. When the fellow came near poor David, and observed that wan and meagre countenance, which the great agitation of his mind (together with a fever, which he had been in ever since he came to his uncle’s) had caused, he was so shocked for some time, that he could not speak. At last he fell on his knees, and imploring pardon, told him the whole story of his forging the will, not omitting any one circumstance. The great weakness of David’s body, with this fresh astonishment and strong conviction of his brother’s villainy, quite overcame him, and he fainted away; but as soon as his spirits were a little revived, he sent for his uncle, and told him what John had just related. He asked him what was to be done, and in what manner they could proceed; for that he would on no account bring public infamy on his brother. His uncle told him, he could do nothing in his present condition; but desired him to compose himself, and have a regard to his health, and that he would take care of the whole affair, adding a promise to manage everything in the quietest manner possible.

Then the good-natured man took John into another room, examined him closely, and assured him, if he would act as he would have him, he would make interest that he should be forgiven; but that he must prevail with his wife to join her evidence with his. John said, if he pleased to go with him, he thought the best method to deal with her, was to frighten her to it. On which the old gentleman sent for an attorney, and carried one of his own servants for a constable, in order to make her comply with as little noise as such an affair could admit of. They then set out for John’s house, when David’s uncle told the woman, if she would confess the truth, she should be forgiven; but if she resolved to persist, he had brought a constable to take her up, and she would surely be hanged on her husband’s evidence. The wench was so terrified she fell a-crying, and told all she knew of the matter. The attorney then took both their depositions in form; after which, John and his wife went home with Mr. David’s uncle, and were to stay there till the affair was finished.

The poor young man, with this fresh disturbance of his mind, was grown worse, and thought to be in danger of losing his life; but by the great care of the old gentleman he soon recovered. The uncle’s next design was to go to Daniel, and endeavour by all means to bring him to reasonable terms, and to prevail on him to submit himself to his brother’s discretion. Daniel at first blustered, and swore it was a calumny, and that he would prosecute the fellow and wench for perjury: and then left the room, with a haughtiness that generally attends that high-mindedness which is capable of being detected in guilt. He tried all methods possible to get John and his wife out of his uncle’s house, in order to bribe them a second time; but that scheme could not succeed. He then used every endeavour to procure false evidence; but when the time of trial approached, his uncle went once more to him, and talked seriously to him on the consequences of being convicted in a court of justice of forgery, especially of that heinous sort: assuring him, he had the strongest evidence, joined to the greatest probability of the falseness of his father’s will. After he had discoursed with him some time, and Daniel began to find the impossibility of defending himself, he fell from one extreme to another (for a mind capable of treachery is most times very pusillanimous) and his pride now thought fit to condescend to the most abject submissions; he begged he might see his brother, and ask his pardon; and said, he would live with him as a servant for the future, if he would but forgive him. His uncle told him, he could by no means admit of his seeing David as yet, for he was still too weak to be disturbed; but if he would resign all that was left of his father’s fortune, and leave himself at his brother’s mercy, he would venture to promise that he should not be prosecuted. Daniel was very unwilling to part with his money; but finding there was no remedy, he at last consented.

His uncle would not leave him till he had got everything out of his hands, lest he should embezzle any of it; there was not above eight thousand pounds out of eleven left by his father, for he had rioted away the rest with women and sots.

When everything was secured, the old gentleman told David what he had done, who highly approved every step he had taken, and was full of gratitude for his goodness to him. And now in appearance all David’s troubles were over, and indeed he had nothing to make himself uneasy, but the reflecting on his brother’s actions; these were continually before his eyes, and tormented him in such a manner, it was some time before he could recover his strength. However, he resolved to settle on Daniel an annuity for life to keep him from want; and if he should ever by his extravagance fall into distress, to relieve him, though he should not know from whom it came; but he thought it better not to see him again, for he dared not venture that trial.

David desired his uncle would let him live with him, that he might take care of him in his old age; and make as much return as possible for his generous, good-natured treatment of him in his distress. This request was easily granted; his company being the greatest pleasure the old man could enjoy.

David now resolved to live an easy life, without entering into any more engagements of either friendship or love; but to spend his time in reading and calm amusements, not flattering himself with any great pleasures, and consequently not being liable to any great disappointments. This manner of life was soon interrupted again by his uncle’s being taken violently ill of a fever, which carried him off in ten days’ time. This was a fresh disturbance to the ease he had proposed; for David had so much tenderness, he could not possibly part with so good a friend, without being moved: though he soothed his concern as much as possible, with the consideration that he was arrived to an age, wherein to breathe was all could be expected, and that diseases and pains must have filled up the rest of his life. At last he began to reflect, even with pleasure, that the man whom he had so much reason to esteem and value, had escaped the most miserable part of human life; for hitherto the old man had enjoyed good health; and he was one of those sort of men who had good principles, designed well, and did all the good in his power; but at the same time was void of those delicacies and strong sensations of the mind, which constitute both the happiness and misery of those who are possessed of them. He left no children; for though he was married young, his wife died within half a year, of the small-pox. She brought him a very good fortune; and by his frugality and care he died worth upwards of ten thousand pounds, which he gave to his nephew David, some few legacies to old servants excepted.

When David saw himself in the possession of a very easy, comfortable fortune, instead of being overjoyed, as is usual on such occasions, he was at first the more unhappy; the considerations of the pleasure he should have had to share this fortune with his brother continually brought to his remembrance his cruel usage, which made him feel all his old troubles over again. He had no ambition, nor any delight in grandeur. The only use he had for money was to serve his friends; but when he reflected how difficult it was to meet with a person who deserved that name, and how hard it would be for him ever to believe any one sincere, having been so much deceived, he thought nothing in life could be any great good to him again. He spent whole days in thinking on this subject, wishing he could meet with a human creature capable of friendship: by which word he meant so perfect a union oi minds, that each should consider himself but as a part of one entire being; a little community, as it were, of two, to the happiness oi which all the actions of both should tend, with an absolute disregard of any selfish or separate interest.

This was the phantom, the idol of his soul’s admiration. In the worship of which he at length grew such an enthusiast, that he was in this point only as mad as Quixote himself could be with knight-errantry; and after much amusing himself with the deepest ruminations on this subject, in which a fertile imagination raised a thousand pleasing images to itself, he at length took the oddest, most unaccountable resolution, that ever was heard of, viz., to travel through the whole world, rather than not meet with a real friend.

From the time he lived with his brother, he had led so recluse a life, that he in a manner had shut himself up from the world; but yet when he reflected that the customs and manners of nations relate chiefly to ceremonies, and have nothing to do with the hearts of men; he concluded, he could sooner enter into the characters of men in the great metropolis where he lived, than if he went into foreign countries; where, not understanding the languages so readily, it would be more difficult to find out the sentiments of others, which was all he wanted to know. He resolved, herefore, to take a journey through London; not as some travellers do, to see the buildings, the streets, to know the distances from one place to another, with many more sights of equal use and improvement; but his design was to seek out one capable of being a real friend, and to assist all those who had been thrown into misfortunes by the ill usage of others.

He had good sense enough to know, that mankind in their natures are much the same everywhere; and that if he could go through one great town, and not meet with a generous mind, it would be in vain to seek farther. In this project he intended not to spend a farthing more than was necessary; designing to keep all his money to share with his friend, if he should be so fortunate to find any man worthy to be called by that name.

IV

THE FIRST SETTING OUT OF MR. DAVID SIMPLE ON HIS JOURNEY; WITH SOME VERY REMARKABLE AND UNCOMMON ACCIDENTS

The first thought which naturally occurs to a man who is going in search of anything, is, which is the most likely method of finding it. Our hero, therefore, began to consider seriously amongst all the classes and degrees of men, where he might most probably meet with a real friend. But when he examined mankind, from the highest to the lowest, he was convinced, that to experience alone he must owe his knowledge; for that no circumstance of time, place, or station, made a man absolutely either good or bad, but the disposition of his own mind; and that good-nature and generosity were always the same, though the power to exert those qualities are more or less, according to the variation of outward circumstances. He resolved, therefore, to go into all public assemblies, and to be intimate in as many private families as possible, and to observe their manner of living with each other; by which means he thought he should judge of their principles and inclinations.

As there required but small preparation for his journey, a staff, and a little money in his pocket, being all that was necessary, he set out without any farther consideration. The first place he went into was the Royal Exchange. He had been there before to see the building, and hear the jargon at the time of high change; but now his curiosity was quite of a different kind. He could not have gone anywhere to have seen a more melancholy prospect, or with more likelihood of being disappointed of his design, than where men of all ages and all nations were assembled, with no other view than to barter for interest. The countenances of most of the people showed they were filled with anxiety: some, indeed, appeared pleased; but yet it was with a mixture of fear. While he was musing and making observations to himself, he was accosted by a well-looking man, who asked him, if he would buy into a particular fund. He said. No, he did not intend to deal. “Nay,” says the other. “I advise you as a friend, for now is your time, if you have any money to lay out; as you seem a stranger, I am willing to inform you in what manner to proceed, lest you should be imposed on by any of the brokers.” He gave him a great many thanks for his kindness; but could not be prevailed on to buy any stock, as he understood so little of the matter. About half an hour afterwards there was a piece of news published, which sunk this stock, a great deal below par. David then told the gentleman, it was very lucky he had not bought: “Aye and so it is,” replied he; “but when I spoke, I thought it would be otherwise. I am sure I have lost a great deal by this cursed news.” Immediately David was pulled by the sleeve by one who had stood by, and overheard what they had been saying; who whispered him in the ear, to take care what he did, otherwise the man with whom he had been talking would draw him into some snare. Upon which he told his new friend what had passed with the other, and how he had advised him to buy stock. “Did he?” said this gentleman. “I will assure you, I saw that very man sell off as much of that stock as he could, just before you spoke to him; but he having a great deal, wanted to draw you in to buy, in order to avoid losing; for he was acquainted with the news before it was made public.”

David was amazed at such treachery, and began to suspect everything about him of some ill design. But he could not imagine what interest this man could have in warning him of trusting tha other; till, by conversing with a third person, he found out, that he was his most inveterate enemy from envy; because they had both set out in the world together, with the same views of sacrificing everything to the raising of a fortune; and that, either by cunning or accident, the other was got rich before him. “This was the motive,” said he, ”of his forewarning you of the other’s designs: for that gentleman who spoke to you first, is one of the sharpest men I know; he is one of the long-heads, and much too wise to let any one impose on him; and, to let you into the secret, he is what we call a good man.”

David seemed surprised at that epithet; and asked how it was possible a fellow, whom he had just catched in such a piece of villainy, could be called a good man? At which words, the other, with a sneer at his folly, told him he meant that he was worth a plumb. Perhaps he might not understand that neither, (for he began to take him for a fool;) but he meant by a plumb, £100,000.

David was now quite in a rage: and resolved to stay no longer in a place where riches were esteemed goodness; and deceit, low cunning, and giving up all things to the love of gain, were thought wisdom.

As he was going out of the Change, he was met by a jeweller, who knew him by sight, having seen him at his uncle’s, where he used often to visit. He asked him several questions; and after a short conversation, desired he would favour him with his company at dinner, for his house was just by.