Ragnar Benson

RAGNAR’S URBAN SURVIVAL

A Hard-Times Guide to Staying Alive in the City

Warning

Technical data presented here, particularly data on ammunition and on the use, adjustment, and alteration of firearms, inevitably reflect the author’s individual beliefs and experiences with particular firearms, equipment, and components under specific circumstances that the reader cannot duplicate exactly. The information in this book should therefore be used for guidance only and approached with great caution. Neither the author, publisher, nor distributors assume any responsibility for the use or misuse of information contained in this book.

Preface

I am frequently asked if city survival is similar to survival in the country or wilderness. Answering that question is a major premise of this book. Since what many people consider wilderness survival actually refers to recreational activities—frequently practiced by elitist yuppies in SUVs—we must set these practices aside before we can answer the question: Is city survival different from rural survival?

The short answer is that city survival is very much like rural survival, only different. It is identical in that the same basic Rule of Threes applies in either place, and that the Rule of Survival Thermodynamics also is still in force. (You’ll learn about these rules soon.) None of these basics has been repealed.

A great many cities have been the scene of vicious battles already in the 20th century. It is foolish not to plan for such in the 21st century.

We also know that caching and storage remain cornerstones of any survival program. The same is true of the rule about avoiding falling into refugee status.

Hunting and gathering skills are still necessary in the city, however, these skills will be adapted to the city environment. Renewable sources of food can be established, but again, they will be much different from their rural counterparts.

Shelter is perhaps initially easier to find in the city, but the dangers of theft, bullying, and depredation will be much greater. Understanding the need for secrecy while living among large numbers of people is very important.

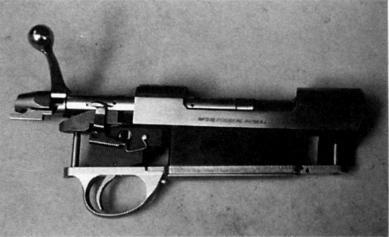

Rural survivalists can, in my opinion, make do without guns. Some notable 20th century survivors, such as Bill Moreland—who survived alone for 13 years in Idaho’s rugged Clearwater National Forest—did without guns for an extended period of years. In the city it’s an entirely different matter. Not only are firearms vital, at least some must be silenced. We had better know how to make and deploy effective silencers.

As a boy in post-World War I Germany, my father walked 3 miles per day carrying two 25-liter (approximately 5 gallon) cans to the river and back. There was a group of revolutionary German soldiers continually trying to shoot anyone—especially kids—out on the street; the reason why is lost in history. Logic suggests that poison gas from incessant warfare continually swirling around them would have poisoned the water, but no one died from the water. Finding potable water in a city survival situation can be an incredible problem. Without advance preparation, the situation could be terminal.

With a shortage of water, irrigating a garden will be a challenge and may violate the Rule of Survival Thermodynamics. But city gardens are still possible. They are being raised successfully even as I write, although they are too often of an ornamental or hobby nature.

City survivors frequently neglect planning for caching and food storage till it is too late. Raised, or perhaps more accurately, managed, livestock as a renewable source of food is also possible. These activities are not intuitive, and those who try to learn after the flag goes up will become casualties.

What about energy in the city? It’s required to cook, preserve food, heat, and provide light. It’s necessary for travel and communications, as well. City survivors have more options regarding energy, but these must entail extremely clever procurement and deployment strategies—much more so than in rural situations. My experts who have been there and done that will speak to this issue.

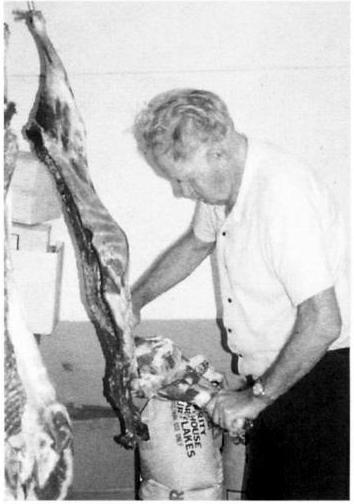

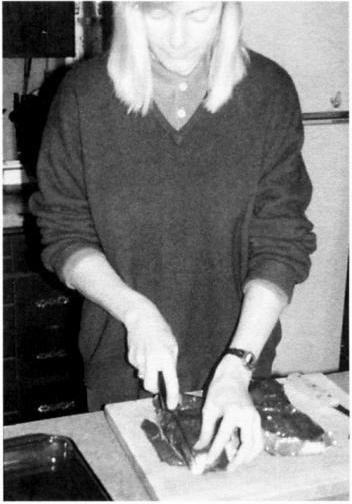

Food in the city, no matter how it’s procured, arrives in a great rush. At harvest time, fruits and vegetables must be quickly dealt with before they spoil. Where livestock is available, city dwellers will need to learn all the survival tricks of slaughtering, butchering, storing, and preserving meat.

One thing that will be dramatically different for people used to city life is the extent to which survivors must band together for mutual protection and specialization. Voluntary specialization is a characteristic of any free, successful economy. For everyone’s benefit, people must be free to do whatever they do best and to trade for their best price. Without these mechanisms, the wrong goods are produced in the wrong quantity and quality Survivors, unskilled in certain areas, are forced to spend precious hours doing for themselves what other, more skilled people could do better, quicker, and cheaper for them. Every society moves to specialization, either under the table or on the table. Unless specialization occurs fairly quickly, there won’t be enough hours in the day to get everything done. Survival is not an activity for the lazy.

Resourceful, learned scrounging has always played a major role in any city survival program. We need to think about these skills now

In this volume I will share what I’ve learned about surviving in the city—that is my commitment to readers. Because as many others have learned the hard way, the need for these skills can occur with lightning-like suddenness.

Introduction

Open space between our cities seems to be disappearing, often with a puzzling intensity and speed. What was just a few short years ago raw countryside filled with idyllic little farms, quaint, remote villages, and gravel roads has been developed into government office complexes, apartment complexes, cinema complexes, and parking complexes.

As young men growing up on the farm, we understood that we made up the 12 percent of the nation’s citizens who provided the rest of the country’s food and fiber. Eighty-acre family farms were not only common, but—much more surprising—economically viable. Ours was a most humble existence, but it provided sufficient goods on which to live.

Then farm efficiency increased, decreasing what we spent on food, and we farmers diminished to 4 percent of the population. There was a hue and cry throughout the land to save the family farm. Speaking personally, I do not know if we really wanted to be saved to the down-and-dirty existence small-farm life provides when our brothers and sisters could more easily go to town and prosper. In any event, the vast majority of us could not put the necessary capital and expertise together required to continue to farm in a modern environment.

Currently, I am informed, less than 2 percent still till the nation’s soil. Farm field and demonstration days I still attend reflect this situation. They are a mere shadow of former times

The era of the family farm has passed.

Our military recognizes this widening urban development. FM 90-10-1: An Infantryman’s Guide to Urban Combat points out that in the past 20 years, cities have spread dramatically. They are “losing their previously well-defined boundaries and are extending into the countryside. Highways, canals, and railroads have been built to connect population centers.”

FM 90-10-1: An Infantryman’s Guide to Urban Combat contains an analysis of the modern landscape.

Even rural areas that manage to retain some of their farm village-like character are now interconnected by vast networks of all-weather secondary roads. This is a bureaucratic way of saying that even if an area looks like a rural farm community, we can quickly turn it into a tank park when the need arises.

Contending governments maneuvering opposing armies historically selected wide-open areas in which to operate, but the 20th century has already proved to be the century of city conflict. Major battles are fought in cities now, not out in open country.

Cities are viewed by modern militaries as having three terrain features—underground, grade level, and high-rise—similar to those of open country.

Cities are perceived to be vital because they are the places of politics, propaganda, transportation, storage, commerce and industry, and culture. Soviet Field Marshal Georgi Zhukov, for instance, had no illusions regarding the strategic value of Berlin at the conclusion of World War II. Militarily, Berlin had little actual value; but from a propaganda standpoint Berlin was vital. Instead of retreating to the more easily defended south of Germany, the Nazis were sucked into this Soviet subterfuge, defending the city down to the last plane, tank, and Hitler Youth member.

More of us are living in built-up areas characterized by row upon row of apartments.

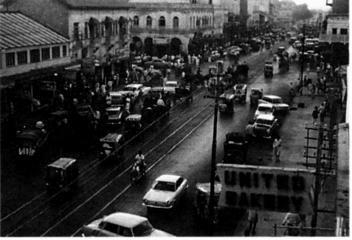

At least 34 major battles have been fought in large metropolitan areas during the past 100 years. It’s a long list, including such notable places as Madrid (if you don’t understand the Spanish Civil War, no war in the 20th century can be understood), Warsaw (the unbelievably horrible Warsaw Ghetto comes to mind), Seoul (four times trounced in the brief Korean War), Saigon (symbolically drawing the curtain on U.S. involvement in southeast Asia), and Beirut (from which much information for this manual is drawn).

Rather than on farms, we will be living in housing complexes when crises hit.

We tend to think of guerrilla warfare as being a product of the countryside, as with Maj. Gen. Orde Wingate’s Chindits, who operated in northern Burma during World War II, or Mao’s and Stalin’s statements that counterrevolutions start on the farm.

This is not true today. Wise military people prepare to fight the next war, not to refight the last. Today our military trains to fight urban guerrillas in built-up areas.

This volume does not directly relate to urban warfare. It does recognize the truth that most of us will likely live in cities, because cities are mostly what there are now. The volume also fully recognizes the survival truth that refugees are never survivors. In its most modern interpretation, survival is living free of government control. Refugees certainly do not fit this definition, probably explaining why they die in such large numbers.

Because contending governments like to fight in cities and because it would be folly to leave our familiar places in cities, we must learn to survive in cities. Like the romantic image of great, sweeping cavalry charges run across grass-carpeted rolling hills, we must face the fact that rural survival is something of a nostalgic notion. Even if wilderness survival was ever really a practical device, it isn’t viable today. We don’t live in rural areas, and rural areas are not where battles will be fought.

Lightning-fast surprise attacks determined to seize enemy urban strongpoints are a cornerstone of warfare in built-up places. Simply put, we could instantly find ourselves engulfed in an urban conflict, neither of our choosing nor of our doing. Such an action would instantly require deployment of survival supplies and superb survival skills. This is perhaps more true in Europe and Asia, but this world is a shrinking place.

Those who rely on the government will probably end up dead.

As a direct result of the 20th century’s being the century of urban warfare and survival, we have a tremendous body of experts who have learned how to live off the land in the city. “Been there, done that” is their motto.

Ranging from my father, who survived World War I in Kassel, Germany, to the many Lebanese exchange students currently attending our land grant colleges, there are experts to call on. Many grew up believing there was no other way of life.

When starting this volume, I vividly recalled the comments made by a senior editor of a large magazine chain that, ironically, included a survival magazine. Force of habit, custom, family, and job-related issues kept her in New York City. Admittedly, it’s one of the world’s truly tough places to survive under even good circumstances.

“When the flag goes up,” she very seriously explained, “people like me are all going to die. People in the country will live, but I have no chance.”

This is not true. We now know with certainty that residents of Beirut, Berlin, and Madrid survived in great numbers under absolutely brutal conditions. They did not have the benefit of prior experience, a survival philosophy, or any special advance preparation. We can have all these in place, as the reader will quickly discover.

Chapter 1

Basic Survival Philosophy

“When it is extremely important that your pants stay up, use both a belt and suspenders, along with buttons on your shirttails,” a Russian proverb says. This basic homily echoes the Golden Rule of Survival, known as the Rule of Threes.

The Pacific Northwest Nez Perce Indians probably deserve the most thanks for refining this rule into a genuinely workable survival plan. Most likely this plan became part of their culture in about 1730 with arrival of their first horses. The Nez Perce were the only tribe of North American Indians who learned to selectively breed their stock, leading to development of the famous Appaloosa warhorse.

The Nez Perce were unique in several other regards. They were the only tribe that did not routinely starve every winter. They had a lifesaving survival plan that soon became an integral part of their culture.

It was a model of simplicity, explaining in large part its great success. The Nez Perce discovered that for everything really, truly important to life, three separate and distinct methods of supply must be developed. As it evolved through the years, this Rule of Threes proved to be extremely wise. Obviously the Nez Perce applied this rule to their life in the country, but experienced city survivors have found that it works equally well for them.

Nez Perce Indians lived well as a result of their survival philosophy.

The system’s corollary proved equally profound. The Nez Perce found—especially in the short run—it does not take very much in an absolute sense to stay alive. Elements of basic survival were simply seen as food, water, energy, shelter, and possibly articles of personal encouragement. In our culture these personal items might be art, music, or perhaps a Bible. One woman I know believes this should include a hot shower once a week. Because these items are so absolutely necessary, positive provision for their supply must be made. Twentieth-century experience suggests that we must include medications, clothing, and self-defense in this list. But we also now know passive defense systems—such as simply laying low and hiding—are often as effective as active ones.

First contact with Europeans for the Nez Perce came on September 20, 1805, when Lewis and Clark rode down out of the mountains into their remote area of what is now the state of Idaho. At that time the Nez Perce already owned six modern (for that era) rifles! These had been bartered from the Mandans and Hidatsa, who had bought them from French and British traders. Because their Appaloosa horses were so valuable, the Nez Perce were able to trade for equally valuable items such as rifles, powder, and balls. Another rule of survival comes into view

Even before firearms, the Nez Perce were able to survive using their Rule of Threes. Later on, having a few figurative trade dollars in their pouches allowed them to survive in much better style. It’s still true today—those with their financial houses in order will survive better and more easily than those who are forced to live under more basic conditions. Those with money for guns and ammo, especially in cities, have a far better chance at survival.

While the basic Rule of Threes works in a day-to-day, practical sense in the city or country, it can also be deployed by those who are into recreational nuts-twigs-and-berries primitive survival. The rule gently draws all of us into a workable plan. People don’t have to leave their current homes for mice-infested, drafty cabins in the hills in order to live.

FOOD

Employing the Rule of Threes, we know that when food is vital for you and your family’s survival, you should develop at least three separate and distinct sources of supply. No one source can in any way be dependent on the other for its implementation. Each on its own should be capable of feeding you and your family during an emergency.

My father and his family in post-World War I Germany, for example, relied on the rabbits and pigeons they tended, the garden vegetables they raised, and wild edibles they found in the fields and city parks, as well as what they bartered for with surrounding farmers. They lived in the center of a large city.

In a more modern context, city dwellers can expect to rely on their domestic rabbits, their gardens, and scrounged edibles gathered from surrounding fields, parks, and rivers, as well as consumption of stocks of previously stored supplies as needed.

The other vital rule is the Rule of Survival Thermodynamics. This means that you must never put more energy into a survival activity than is taken out. Those who fail to heed this warning quickly become casualties.

This generally rules out sport hunting and fishing, but opportunistic shooting of critters for the pot in the course of other survival-related activities probably would not violate this precept. Keep in mind that in Indian cultures, most edible critters were caught in snares or deadfalls. Theories of fair chase and conservation did not enter the equation.

Survivors who have adequately prepared can expect to go to the food shelf to resupply.

Rabbits are ideal food animals for city survivors. They eat virtually anything green and are extremely prolific.

Gardening as a survival technique may also be impractical for many people who haven’t gardened before in their specific area. However, survivors who are already practiced in their city-based gardening skills can probably see a net gain for their efforts.

Foraging in the city can also yield food, but it is difficult. Our early Indians learned to properly treat acorn meat (washing out the tannic acid), hunt wild bees, dig edible flower bulbs, and collect cattails and many other edible plants. Today, in the city or country, the only foraging technique that practically qualifies for most Americans involves gathering cattails. Other edibles are sparse, hard to recognize, of little food value, and generally unavailable in winter. As a practical matter, collecting nuts, berries, and twigs generally makes little survival sense.

But the good news for city dwellers is that cattails are every where. My old, old account regarding cattails with which many survivors are already familiar, involves the time I was riding in a taxi from National Airport at Washington, D.C., (now Ronald Reagan National Airport) into town with a skeptical newspaper reporter anxious to discredit all survivors. We passed acre upon acre of cattails growing wild along the Potomac River. My point about these being an excellent survival food that was commonly available in an emergency was instantly made.

Even when very large game is targeted, sport fishing and hunting is not usually viable for survivors.

Only opportunistic game shooting done while undertaking other jobs is a viable survival technique.

During the fall and winter, cattail roots can be sliced and boiled, substituting for potatoes. In spring and summer, tender shoots can be harvested and steamed for the table. In season, cattail pollen is relatively easy to collect, substituting for flour as much as 50 percent by volume in biscuits. Green cattail flowers are also nutritious and abundant when collected and eaten before they mature and brown. Most important, easily identified cattails grow everywhere in the United States in great abundance. Nothing else looks like a cattail and they are never toxic. The danger is, of course, that over time, many city survivors will obliterate limited city cattail beds, but so far this has not happened. Despite my best efforts at promotion, few people seem to know about and use cattails!

Cattails grow next to a housing development. This vegetable does not pick up surrounding pollution and, when well cleaned, is always safe and nutritious.

Another valuable food source available to city dwellers is rabbits and pigeons. Those who have never raised livestock before will find these animals fairly easy to raise. Rabbits are some of the best composters available, and they eat just about any cellulose at hand. After learning how to handle them, three females and a buck will produce enough meat for two rabbit-meat meals per week, while simultaneously fertilizing the garden. And they are good city animals. I recently discovered an extensive, mostly hidden, rabbit enterprise in a crowded English city.

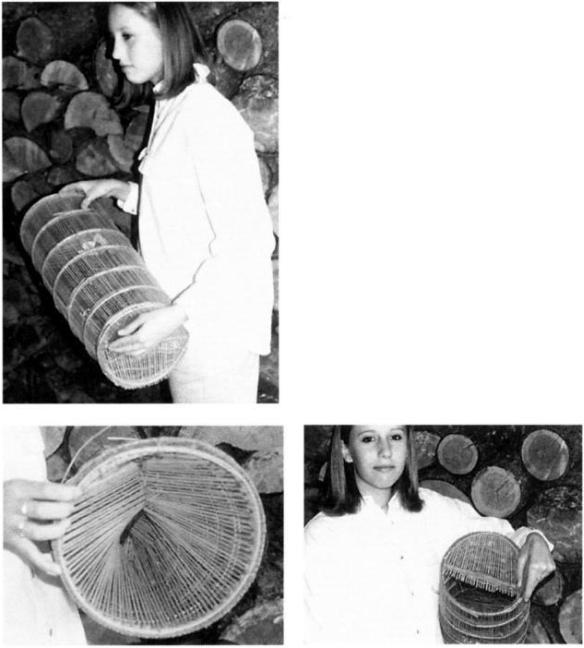

Members of this family raising rabbits in the heart of a large industrial English city are practicing survival skills and don’t even know it.

As a food source, common pigeons are another critter with great charm when raised in the city. They fly out to get their own food and water from a roost that can be established virtually anywhere. Fifteen adults easily produce sufficient meat for another two meals per week. There will be more about raising these critters in the city in subsequent chapters.

Game animals of all kinds from rabbits to carp are best trapped. Learning how isn’t difficult. Set out great numbers of traps, repeating what works. In cities, expect to catch cats, dogs, and rats; in the country, look for deer, rabbits, and geese. Trapping wild or semi-wild game is part of the Rule of Threes for both city and rural survival.

Survivors in a life-and-death setting must trap all of their game. Sport hunting and fishing risks using more calories than are earned.

Getting raw grain from farmers may not be practical or possible for city survivors.

Bartering with farmers and stockmen for edibles is another alternative. Those living near farms may be able learn how to preserve harvests themselves. Like country survivors, the city variety must be willing and able to preserve their own food.

CACHING AND STORING

Grain terminals, if they can be reached, have sufficient food for a city for a year. Fresh water is a plus.

Most city survivors will elect to make stockpiling a large part of their three-legged food survival program. Understanding how to effectively stockpile intimidates some folks. Here’s a simple way to determine what you’ll need: Instead of guessing about what you think you’ll need, just start buying doubles of all the essential items you normally purchase. For 8 months preceding the hour of need, start saving all these extra supplies in one set-aside survival area. Soon there will be more than enough lightbulbs, hand soap, sanitary napkins, coffee, and so on, to see you past an emergency.

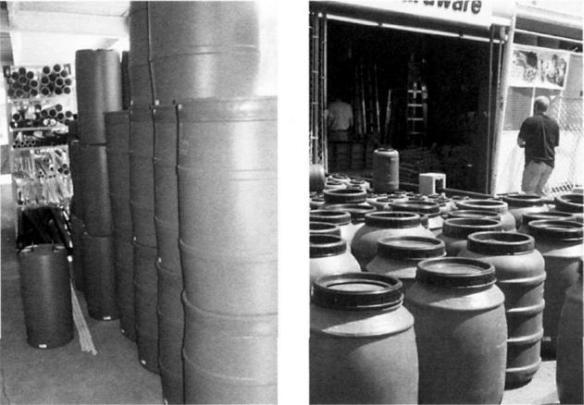

Plastic barrels can be used for deep, long-term hiding and caching of survival supplies.

WATER

Three sources of potable water are a must. One source could be the municipal pipe into your home, but is not a source you can count on. City dwellers might consider renting a shallow well auger to sink their own backyard well. It is not too early to think about the availability of pond, river, or lake water as part of one’s water Rule of Threes. You’ll also want to consider a rig to catch and store rainwater from house and building roofs. All that is needed to implement this collection storage plan in most city circumstances are some extra gutter, plastic tarp, and plastic storage barrels (which for some reason are most often blue). Other suggestions are to store water in bottles, bladders such as waterbeds, or fiberglass water tanks.

ENERGY

Planning three sources of energy is not tough once you overcome the realization that they probably all must be purchased well ahead of need or, within cities, actively scrounged up by creative survivors. I plan to use 1,000 gallons of stored fuel oil to run my generator and provide some heat, and 1,000 gallons of propane to cook, heat water, and perhaps warm the house. Large propane storage tanks may not be legal in cities, but I know of two current survivors who have 1,000-gallon propane tanks buried out of sight under their garage floor. My third energy source is 25 cords of scrap wood that I can replenish from abandoned buildings and storage areas as needed. I could heat, cook, and survive with scrap pallet wood alone.

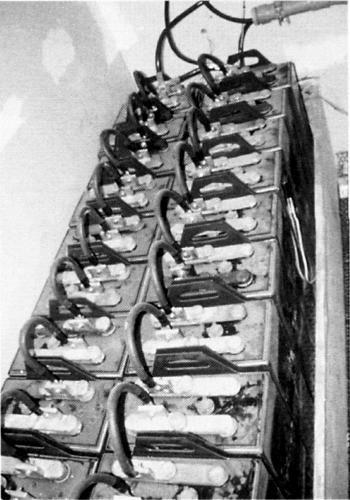

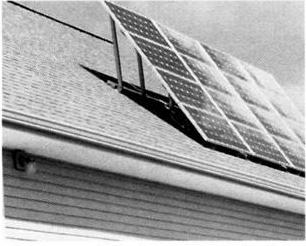

Depending on one’s specific circumstances, there are also coal, geothermal devices, solar cells, and fuel cells. Small, increasingly inexpensive fuel cells used for direct electrical conversion from LP (liquid propane) gas are coming on the scene. There are also very unconventional fuel sources. My father ran out every time a team of horses came by to scoop up any road apples, which were either dried for fuel or shoveled into the garden as fertilizer. Although road apples have gone the way of dinosaurs in most places, your city survival plan will eventually entail these sorts of improvisations.

SHELTER

Shelter in our list of threes also encompasses clothing and emergency medical supplies. Most people in our outdoor-oriented society have sufficient boots, jackets, and warm, woolly sweaters to wear when the place can’t be kept at 62 degrees. Emergency medical supplies are a complex, separate, and very philosophical issue that should be addressed by survivors as quickly as possible.

Shelter might be your present home or apartment. First backup can include an abandoned cellar, backyard dugout, a tent, or per haps a cooperative area, depending on risk levels. Others may have a travel camper, old bus body, or even an old warehouse in which to hide a shelter. You may make tentative plans to move in with your kids or back to your parents. Anything just so long as the Rule of Threes relative to shelters is addressed.

It’s tough advice for city people, but no matter what, never, never become a refugee. Survival rates among refugees with no control of their destinies are dismal. Refugees are totally the wards of government. If you believe the government does an adequate job of running the post office, Social Security, and the military, then you will probably be satisfied with the way it will run your life as a refugee. Effective hiding is an important part of city survival as it relates to the Rule of Threes.

Our technology is changing quickly. For this and reasons of personal circumstances, skills, and likes and dislikes, our personal survival plans are never final. Readers should include survival means that I have never dreamed of within their own Rule of Threes. A survivor in east Boise, Idaho, has his own private geothermal heat. well, for instance! We will miss opportunities unless we are constantly alert for them.

Russian survivors also postulated the Rule of Threes, but it didn’t maintain their Soviet Union.

A Russian flag flies over the old Soviet embassy in Bangkok. Russians’ use of the Rule of Threes often covers only social situations, e.g.: If you want your flag pole to stay up, set it in concrete and use doublestrength metal pipe and guy wires.

This is the overall guiding philosophy to survival. Obviously it applies to city survival. Commit to it and you will live. To gloss over parts of it is to suffer extreme consequences.

Chapter 2

Combat in Built-Up Areas

Warfare once took part largely over natural terrain, including mountaintops, rolling hills, jungles, and barriers such as rivers and lakes. However, most battles are now fought on urban terrain, which consists mostly of man-made features. Chiefly, these are tall buildings, rows of solidly built, difficult-to-breach concrete factory buildings, rows of flammable dwellings two stories high or less, wide open four-lane highways leading to places commanders don’t necessarily wish their infantry to go, and elaborate sewer and subway systems.

In the eyes of the military leader, city buildings provide cover and concealment to the enemy, block potential fields of fire, limit observation, and severely limit use of armor and artillery forces, which cannot elevate or depress their guns sufficiently to reach many targets. As a practical matter, only high-angle mortars are thought to be effective in city terrain, and even then three to five times as many of them are required.

Many buildings will be reduced to rubble in the course of urban combat.

In spite of this great disadvantage, arrogant commanders often order their troops and armor into cities when encirclement—trapping defenders in a city—might possibly be a wiser tactic. Cities have grown so large and of such strategic importance that commanders no longer have the advantage of starving them out, many experts claim. Grozniy in Chechnya is a good, fairly recent example; rebels there got more than 100 Russian armored vehicles before it was over. But, nevertheless, we often wonder at the bravado with which generals sacrifice their men and equipment engaging in city warfare.

Tall, imposing buildings will become like major high hills dominating an urban area. Commanders will likely use these for gun positions.

The end result for city survivors is about the same. Either they must avoid hostile attackers, or their own defenders might become hostile and create as many problems as the attacking infantry.

The North Vietnamese tunnel system and our tunnel rats got a lot of publicity, but starting as early as the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939) defenders actively used underground workings to either infiltrate or exfiltrate cities. Some people estimate that the defenders of the Warsaw Ghetto could have held out against the Nazis as many as 30 additional days by clever use of Warsaw’s extensive sewer system.

Underground works are currently one of the first places attacking soldiers attempt to secure. Unless completely walled off and cleverly camouflaged, interconnecting sewer works and utility tunnels are not places of choice for city survivors to take refuge. Modern urban soldiers with good leadership no longer make uninformed snap decisions regarding underground terrain. Reportedly, survey maps of the world’s major cities underground are part of our covert military information-gathering process. Saddam may be rightfully paranoid about our efforts to find out about Baghdad’s sewers.

Communications and helicopters will be important within contested cities, but their usefulness will be limited by the nature of the terrain.

City warfare is similar to warfare in the country in many regards. Modern, properly led infantry elements preparing to take a hill no longer line up at the base to receive a pep talk from their leaders, listen to martial bagpipe music, and then charge on up. Instead, a huge bomb is probably dropped on top of the hill and the infantry instantly helicoptered in for an assault from the top down. Urban combat is envisioned as being only slightly different.

Commanders will identify the tallest, most impressive high-rise building in the center of a contested city—one that is sufficiently stout to support rocket launchers, heavy machine guns, and mortars. Incredibly, modern urban warfare doctrine suggests that these prominent buildings should be taken by helicopter assault groups moving from the top down, often after high explosives placed on the top floors clear them of defenders.

When enemy fire and other considerations preclude helicopters, it is the current wisdom that attacking infantry forces first climb to the top of targeted buildings on fire escapes or inside stairs. Once on top, they begin their assault, fighting their way back down again. Defenders will no doubt attempt to hinder these assaults by placing barbed wire, antipersonnel mines, and other obstacles in stairwells to impede the progress of attacking forces.

Out in the country, high-profile hills are not good places to survive. The same is true in cities. The tallest buildings will likely be at the center of heavy fighting. Survivors should avoid these.

Radio communications between soldiers and commanders in cities are often poor, resulting in both good and bad conditions for city survivors—a soldier on his own may be easier to deal with, but on the other hand he is also unencumbered by his commander’s ethical directives.

Arrogant, inexperienced urban commanders often send their armor into situations where it cannot maneuver and is subsequently destroyed by defending citizens.

Incredibly, commercial phone systems—most of which operate through deeply buried conduit-encased lines—are seen as being more resistant to attack. Contending parties will each attempt to appropriate civilian phone service for their own use. Survivors near central telephone switch facilities may be subject to some rude treatment.

Groups of attacking infantry, as well as defenders, will quickly be splintered into small, isolated units, operating completely independently. Each will be responsible for its own decisions, many of which may not be wise or—at a minimum—may not fit into the big picture. The loss of a small group of infantry many not be immediately obvious. Exactly why it was lost, under what specific circumstances, may never ever come to light.

This brings us to realize that often within cities under attack, small groups of isolated infantry may possibly be taken out with no repercussions for the survivors. But the probability is that one never knows when this will be true: Battlefield communications capabilities are increasing dramatically. It is best not to count on this defense when other devices such as deep hiding are available.

City survivors who very cleverly hide their presence in unobtrusive, untargeted places often survive nicely. This will probably entail removing all signs of their retreat. They will have to learn the art of camouflaging and carefully hide all survival supplies—all signs of their presence—while simultaneously not participating in the war raging about them.

Small, individual actions fought with great intensity characterize urban combat.

Huge quantities of supplies will disappear during any urban combat situation. Survivors with their limited resources should think carefully before committing themselves to urban combat.

This is not easy. City survivors report that because of crowded living conditions, accompanied by great sanitary and disposal problems, retreats are frequently located by smell alone! Even cooking food among the smell of destruction can be an instant giveaway. Military targets in cities, when they are exposed, are most frequently visible at ranges of 100 meters or less. As a result, urban conflict tends to be low-tech. Infantry units will have to have some compelling reason to come into your immediate area; otherwise, your retreat may be completely overlooked.

Close, violent combat with light auto and semiauto weapons, flamethrowers, hand grenades, mines, and light antitank weapons (taking the place of artillery), is common in urban warfare. Obviously, many traditionally civilian weapons likely to be in the hands of urban survivors will work nicely in these situations. Defenders will not have to rely on standard military equipment to make an adequate showing. Knowing that the reliable, scope-sighted semiauto .22-caliber rifle could be used at the short ranges in cities to trump well-armed attackers is certainly a source of comfort.

Urban conflict is notorious for the vast, virtually disproportionate amount of munitions it chews up. Internal defenders without regular lines of resupply are at an advantage if they have enough prepositioned supplies. Theft of war materiel is a great concern for attacking forces, but since capturing enemy supplies is risky, experienced city fighters report that most of their stuff came from preexisting, internal stockpiles. Again, city survivors should only get involved if their most immediate area is compromised.

The rule of thumb in this case is that, again, city survivors should not get involved in battles. If they do, their precious private supplies will be quickly exhausted. Replacement by capture does not work and should not be part of a survival plan, experts claim.

This advice proved accurate in the reduction of Berlin and Beirut, but not so accurate in the Warsaw Ghetto. Certainly it’s a matter of how badly either side wants to continue to fight and what sorts of skilled manpower are available.

Modern cities have grown together, producing situations in which the military commanders will send their troops and equipment through buildings rather than down streets.

Armor used in cities can be decisive, but deployment always carries great risk.

City combat is different from combat in the countryside in some deadly regards. A veteran of World War II city fighting recalls that whenever a city had to be taken, he and his fellow soldiers never, never allowed themselves to be channeled down existing streets and roads when entering the city. Instead they used satchel charges, tank guns, and tanks as bulldozers to punch holes through lines of houses and through factories. By moving through the insides of existing structures they kept out of the enemy’s sight and out of his ambushes, he said.

The top of a partially destroyed building can provide excellent cover.

But predictions are tough. Houses along main thoroughfares were often targeted, while those behind were frequently spared. Attacking soldiers also avoided remote neighborhoods where no obvious resistance was organized, especially if barriers and minefields were in place. Another lesson for city survivors.

Fortunes of war are indeed fickle. Absolutely no one can really know ahead if they will end up in harm’s way. I think of the Englishman so disgusted by World War I he moved to a remote coaling station in the Pacific. Vessels had then begun to burn Bunker-C fuel, not coal, so “nobody will ever bother me here,” he reasoned. But, of course, Midway Island became a major battleground in World War II.

As long as they are tall, buildings that are not strategic and less than dominant can successfully be turned into protected fortress-type structures for use by city survivors. Beirut provides several excellent examples. Survivors there often occupied apartments of high-rise buildings whose top two or three floors had been reduced to rubble, either intentionally or by enemy artillery fire. Layers of ruin above provided excellent protection from artillery or mortar fire, while both giving the impression of being a dead building and giving defenders high ground among protective rubble. But there were other considerations.

Was the building dam aged to the point of near-collapse? Some residents lived in great danger in this type of rubble. Additionally, past six or eight floors, walking up to an apartment on a daily basis becomes a real chore (obviously no elevators ran). Survivors argue both ways. While hauling in food and water was difficult, these buildings offered high-rise inaccessibility in uncontested neighborhoods and provided great security.

Some movement out of the retreat will be unavoidable. Know ahead that leaving the retreat is accompanied by great danger and that this must be planned for. Sending a boy or girl out for essential food, water, or medicine often presents an unacceptable risk, because torture is a common and, many claim, necessary element of urban warfare. I have spoken with German women who lived in Berlin at the time of the Soviet occupation, who recalled that if they were caught out on the street they were raped often six or eight times before escaping and hiding again.

Rubble produced by enemy artillery and air strikes can hinder the movement of attacking infantry while simultaneously providing cover for defenders. Attacking commanders often attempt to minimize this problem by ordering their troops to torch cities. The success of this device depends entirely on the type of construction and nature of building contents. Under the wrong circumstances there is little to be done to save one’s city, urban survivors claim. Some survivors report having been able to remove combustibles while simultaneously putting out fires as they started. Others took shelter in fire-resistant buildings.

With the battle past, some even re-established living quarters in fire-gutted buildings. This doesn’t sound terribly practical, but many of these folks reported living through what seemed like horrible, large, citywide fires.

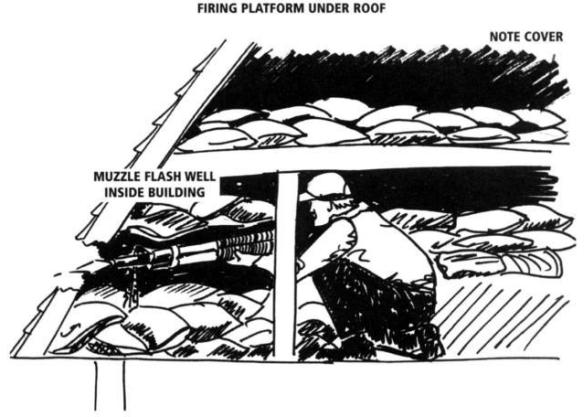

Sandbagged emplacements are recommended to control fire and to afford some protection from small-arms fire. These can be quite clever, including sandbagged overhead racks, frontal barriers, and floors. Often these structures take on the character of gun emplacements. While those who intend to fight with the urban guerrillas need to know the theory behind these, they are mostly unnecessary for city survivors and will not be covered here, except in passing.

Those interested can secure U.S. Army training manuals on urban warfare as reprints from Paladin Press or in their original form from military manual suppliers. Most military manuals are available in local university libraries where they can be freely copied. Look for anything on combat in built-up places.

Not only is warfare likely in cities where we live, it is also like ly that this warfare will be bitterly fought. Modern commanders know from past experience that a well-prepared and mutually supported position in a city can usually be defended by a small force. Attackers are likely to suffer heavy losses and perhaps even temporary defeat against a smaller defending force.

Small, portable weapons that give individuals great firepower will be a decisive factor in urban combat.

At one time wise commanders bypassed builtup areas, allowing defenders be gradually starved out. East of the Mississippi and in Europe, urban development is so extensive that this tactic is no longer considered practical.

In this and most other cases, survival has proven possible if we limit our defense to our own immediate area. Personal defense in cities, especially when the distinction between the military and police is blurred, is complex. More about this in subsequent chapters.

Urban warfare is old hat to some and terrifying to others. Recently some good friends in the militia movement argued at great length that because our military has studied warfare in builtup areas, it was planning to attack Citizen America. In that regard, the topic was terrifying to them. More likely our military studies this situation because it is the one that must be dealt with. We who plan to survive in cities also need to study it to know what lies ahead.

If anything, this situation demonstrates that successful city survival is the ability to remain flexible, creative, resourceful, and knowledgeable under city warfare conditions. It’s about knowing how urban warfare will most likely be undertaken and how to pick places least likely to be heavily affected. It’s not about banding together to engage in open, violent urban warfare against a common enemy. People surrounded, identified, and cut off will always eventually be destroyed.

Those reporting the greatest success claim that they husbanded and hoarded all their resources so that, after the enemy had passed, they had the necessary supplies to allow them to hunker down for the long haul—the real work of city survival.

Chapter 3

The Government’s View of Survivalists

“So, you define a modern, practical survivor as being an individual who is not dependent on government for any kind of help or assistance,” a reporter assigned to a nationally known modern men’s magazine quoted back somewhat skeptically.

“Yes,” says I, “but add in the fact that government help is always intervention, not help. They try to put a human face on things but look how many people have been manipulated, ruined, and even murdered by their own government in the 20th century alone.”

Governments never trust freedom-loving, independent citizens.

It seemed especially curious that he had called from New York—not an especially notorious center of freedom or survivalism or individual liberty.

Judging by the trite little collection of shallowness and trivia he eventually came up with for an interview, the fellow really didn’t get it. Even as brief as it was, his article was shot through with scorn and ridicule toward survivors or anyone who would ever dream of living free. It was the same day the Albanian refugee crisis hit the front page. People are being murdered en masse by their own government and he ridicules anyone who would think of living free from government “help.”

I asked which goods and services he personally depended on that came directly from central authorities.

He didn’t want to hear it, but Mao, Stalin, Lenin, and even Heinrich Himmler, director and early organizer of the Nazi Schutzstaffel (SS), fully recognized that counter-revolutions traditionally have started in the countryside. Himmler believed it could be a good revolution if it was kept entirely under his personal direction, philosophy, and control. Perhaps this is part of the origin of Mao’s and Stalin’s intense paranoia regarding rural freedom-loving survival-type individuals. Yet, keep in mind, Lenin predated any serious SS philosophy by at least 10 years. Why he really feared country folks and wanted to herd everyone into cities is probably lost in history Lenin said it was to industrialize the country. So they became worker bees in his own private hive!

We see it today in our own society. There are people who believe the government can solve problems and are willing to allow others to take control of their lives. There’s no question that the bureaucracy still believes that if it herds enough citizens into cities and provides enough essential services, the rank and file can be brought. under their control. Substantial amounts of propaganda regarding the indispensability and wisdom of government are a prime ingredient in this formula. Then those who wish to continue this feudal system under their own superior “leadership” can prevail over the rest of us.

This simple little concept in this brief chapter is the core of city survival: Those who are and/or will allow themselves to be wards of the government don’t have the slightest prayer of making it in a truly grinchy city-survival situation. In times past it was said, “Understand this concept and live free. Neglect it and become a slave.” In cities it’s life and death, not just freedom and slavery

The problem is that city survivors have a greater struggle in avoiding this evil trap. Providing essential goods and services to naturally independent, widely scattered, historically self-sufficient country people is so inefficient that governments that try quickly go broke. Currently few make the effort. There are just not enough people concentrated any place out in the country to be worth dealing with.

Observation and police helicopters will be used against city survivors.

Also, I strongly suspect that in our modern times, other than in a few remote and insignificant regions around the globe, there no longer are enough people in the country to carry out a successful counter-revolution.

This does not suggest that government officials are no longer paranoid in the finest Maoist-Stalinist tradition. Although it is not widely known or popularly understood outside certain regions, significant numbers of freedom-loving citizens in Washington state, Oregon, Idaho, and western Montana view current government Wild Lands proposals—which are plans to move people from their rural homes and into cities to allow the land to go back to nature—as being little more than a thinly disguised method of putting the people in the position of becoming wards of the government. The fact that Wild Lands proponents receive huge amounts of under-the-table government money in direct defiance of congressional oversight or approval—very similar to CIA funding during our Vietnam era—does little to calm citizen fears.

The modern Bradley fighting vehicle, often used to deliver a squad of infantry into built-up areas, has more firepower than World War II main battle tanks.

Yet changes in our society are occurring at a breathtaking rate. Our military recognizes this truth when it prepares to fight in cities. Unstoppable events, including dramatic advances in technology way beyond our control (and perhaps even our understanding), are pushing all of us into living in built-up areas. These areas are characterized by high population densities and large numbers of buildings, and put us in great danger of dependence on government for goods and services.

But back in New York on the phone with the men’s magazine reporter, my question was, “What absolutely vital goods and services necessary to daily existence do you rely on that are provided by the government?”

His answer was a no-brainer in more ways than one. “Absolutely nothing,” he quickly thundered back. That these people are all cut from similar cloth should not be a surprise. He was now had by the ears, but he didn’t quite know it. Sounded familiar.

“Oh,” says I, affecting my best innocence, “then you can own a firearm of some sort, thereby taking personal responsibility for your own immediate security?” Keep in mind it was New York on the line, where personal responsibility for security has been lost for decades.

“Why would I even dream of owning a gun? I don’t want to attack anyone,” was his instant response. Obviously he was from one of those new touchy-feely type of men’s magazines that wouldn’t touch articles about guns, cockfighting, cigars, or bear hunting on a bet.

There are those among us who believe that our president’s cur rent tirade against gun owners is not really about diverting attention from his many other shortcomings, but rather a thinly disguised attempt to make average citizens more dependent on government. This theory gains credibility when we realize again that our police forces have no binding legal responsibility to protect us! Citizens have repeatedly tried to sue for damages when they were denied permission to own a gun for self-protection and were subsequently attacked. Suits for damages against their police departments got nowhere.

An actual Soviet tank used by Fidel Castro to crush insurgents.

It’s true that Thomas Jefferson believed Americans should own firearms as a final last resort against government officials who oppress them. But in this era of wall-to-wall cities, it may be more than that. There is also the matter of government ownership and distribution—either through direct ownership or indirectly through licensing—of electricity, heat, water, communications (radio, phone, and TV), transportation, and postal services. But self-protection is even more at the core than these.

Numerous experts have pointed out that Stalin could never have murdered and carried out deportations in the Ukraine, Mao in northern China, Pol Pot in Cambodia, or England in Scotland (during their 18th-century war of independence) had average citizens been even modestly well armed.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, author and philosopher, believes the Russian people could have even successfully resisted the secret police and going to the gulags with little more than resolute application of axes, butcher knives, harvesting tools, and meat hooks. Sounds like lots of resoluteness, but his idea is duly noted.

The reporter never did admit to seeing the connection between private firearms and freedom, but he seemed to warm to the idea that official provision of sewer, garbage, and water service could quickly lead to significant control. “Fact is,” he said, “I vividly recall our garbage strike and what an incredible mess that turned out to be,” he finally admitted.

Governments in most places handle waste and garbage. Disposal of these can be a weak link for hiding city survivors.

He did weasel a bit by claiming garbage service was private in New York. “Yes, private, but maintained by a government-enforced monopoly,” I suggested. “All they have to do is threaten to pull the company’s permit and your garbage collectors will do whatever the bureaucracy wants. You cannot legally go into any business in New York without official sanction,” I reminded him.

Downtown Havana, Cuba, where compliant citizens are herded into places of complete subjection.

Water is extremely important to city survivors. Failure of supply could be as serious as going without personal protection, and could arguably be as vital or more vital than personal gun ownership. But to claim that garbage is more important than guns is just that.

Other than electric utilities being government-controlled monopolies, is the electrical system in very many big cities in America still directly owned and controlled by the government? During the 1920s and ’30s many small, more rural cities developed their own electrical systems—mostly small-scale hydro projects. Currently, even when utility companies are not collectively owned, the authorities can throw their considerable weight around, denying service to anyone they wish. This is exactly how it works in Cuba, where average citizens don’t receive enough power each day to successfully run a refrigerator!

Wise city survivors had best look at their own situations now, before the crisis. What essentials to your life do your central authorities provide? Can they arbitrarily and capriciously cut you off, forcing you into becoming a ward of the state?

Forms of government dependence are not all obvious and may vary in priority according to a person’s philosophy Service may vary from city to city, and from country to country. In Britain and Canada, for example, citizens must go hat in hand to the bureaucracy for permission to have a vasectomy; a hernia repair, or knee surgery A close friend flew his mother to the United States for a hip replacement because she was too old to receive one in Canada! Bypass surgery is not done in Cuba past the age of 50 because recipients do not have sufficient working life left to give to the state. The United States is headed in that direction. More distressing, some people really believe this is a good thing!

In Beirut, shortly after the very bleak days, private mail courier services sprang up. Again, we must keep our eye on the ball. Establishment of private medical care might be very important. But is mail delivery on our list of absolutes required to sustain life?

On one occasion a woman told my daughter, only half in jest, that she could not envision life without her daily soaps (low-grade melodramatic entertainment). Possession of a functional TV cable, satellite dish, or computer connection might possibly be a requirement for her life. That is certainly not a judgment I wish to make.

Like any other survivors, city survivors must start planning now if they hope to provide their own services. It’s very important to note that, on close inspection, we often find many of these services are provided by central authorities. Anne Frank, the young Jewish girl in World War II Holland, almost survived. She wrote that at times a chronic lack of sewage/waste disposal actually threatened their sanity, security, and immediate health.

Personal responsibility and self-reliance require great attention to detail. An unlicensed private nursery in Salem, Oregon, for example, was discovered and summarily shuttered when authorities were tipped off to its existence by the quantity of disposable diapers found in their trash. This is not city survival, but a down-home example of the length to which bureaucrats will go to maintain their control.

Citizens squashed by enemy armor at a watering area.

My list of vital services that may be controlled by the government and for which city survivors should make other arrangements includes the following:

• Sewage systems

• Garbage collection and disposal

• Communications including radio, television, phone, mail, and Internet access

• Fuel

• Medical services

• Utilities such as gas and electric power

• Transportation

• Water

• Food

• Self-defense/security

• Shelter

Of these, only food, water, shelter, and self-defense are definitely on the list of must-haves needed to survive. Others may also be there, depending on one’s personal circumstance. My advice is to never, never rely on people who don’t give a damn—such as government officials—for something really important.

Chapter 4

Water

“Successful city survivors will have to drink lots of brown and green water.”

After hearing this a second and third time from survivors of Berlin and Beirut, it was obvious that this was going to be a very nasty chapter.

It’s akin to the social structure in socialistic economies. Everyone is equal, but some comrades are more equal than all the others. Supplies of water are like that! All absolute elements of survival will lead to death when denied, but depending on weather, workload, and physical condition of the survivor, water is the most immediate. Without it you die quickly and cruelly.

The Rule of Threes is an iron rule in the case of city survivors and water.

But there is great cause for hope. In a very few cases, water continues to run from the pipe. It may not be usable without further treatment, but it is something to work with. For purposes of this chapter, though, tap water is not a consideration. Few experienced been there, done that city survivors mention using it.

It isn’t an accident of history that many cities in the world were built around natural waterways. Easier transportation using boats and barges in the early days led to that. Cities grew around profitable commerce. Securing adequate potable water may simply be a matter of laying in securely covered, easily filled and cleaned plastic buckets, a carrying yoke, filter racks, purification chemicals, and larger retreat-type storage tanks to be used to haul, treat, and store water from rivers and ponds running through or lying around our cities.

City survivors must creep unseen into public areas to fill their containers with water from ponds, marshes, and streams.

In real life it is seldom that easy. Survival is never particularly easy or convenient. It is not a game for lazy folks who cannot or will not plan ahead.

COLLECTING WATER

Getting to and from a pond, canal, swamp, lake, stream, spring, or any other natural water source may be dangerous. It may not be practical or even possible. Many city survivors recall hauling water over as much as 3 miles one way once a day. Figure that on your return trip, weighed down with water, it’ll take you twice as long to cover the same ground. On the return haul, slow-moving, heavily laden water carriers may fall under observation, suspicion, and perhaps enemy fire. Great care and extreme caution are definitely in order.

Cities, especially the shot-up variety, provide great opportunity for cover and concealment. At times, large numbers of people will be milling about, providing even greater confusion. This can be a type of cover and concealment itself. City survivors obligated to haul water from great distances had best pick their route and an emergency alternative, as well as time of day with care, lest they compromise themselves and all the others at the retreat. World War II city survivors in occupied countries were in constant danger of the Gestapo and many instances are on record of food or water gatherers simply disappearing. Like smoke in the wind, no trace was ever seen of them again.

How to keep out of enemy clutches? Here are some suggestions from our been there, done that folks: Plan to leave the retreat at a time of the day when surrounding activity is minimal. Travel by a route that does not cross enemy lines and is least likely to lead to exposure, even if this is a very long, circuitous route. Leave the retreat by a route hidden from view.

Humans can walk at a rate of from 3 to 4 miles an hour. Send two water carriers out together, allowing switching of the heavy return load while still maintaining maximum speed and alertness. When not carrying, the other should act as a slightly forward lookout. Survival is about not being lazy or inattentive to details. Don’t pick the shortest route unless it is also safe. Always pick the safest route. At the first sign of danger, abandon hauling equipment to run off and hide.

Undertake haulage in 4- to 5-gallon covered cans balanced on a shoulder pole assembly. Carrying heavy buckets long distances over rough terrain by using only hands and arms is not practical.

Precipitation

Collecting rain and its close cousins, snow and ice, is another good, practical, city-survival water-gathering technique. One observer said that he saw it often in Beirut and even in Karachi, Pakistan. I have personally observed many rainwater collection systems in several Yugoslavian cities.

Modern technology helps loads. But just as water from ponds and rivers must be filtered and purified, so must precipitation be treated. And collecting it is just as risky for city survivors as hauling water.

To catch and funnel falling water we have large sets of plastic tarps strung in almost tent-like fashion. It doesn’t take a Phi Beta Kappa to realize that someone is around maintaining and using the device.

Those who plan ahead can put together a system to collect rainwater from roofs and gutters.

Collecting water from rooftops that would normally gush down a drainpipe into a storm sewer is also possible. Use plastic sheets and pipe to direct this water into your holding tanks. No precipitation in a city is particularly sanitary. Catching from rooftops that people may walk on and that may also catch dirt and debris is especially unsanitary. Clean collected precipitation similarly to the way you would treat water from ponds, swamps, rivers, and lakes by using a sand filter rack and bleach.

Except in some particularly sodden parts of the world, rain falls infrequently. Bountiful quantities must be stored when it arrives from the heavens. Plastic barrels weighing about 450 pounds when full are ideal. Do most readers realize how absolutely awful water stored over the long term can become? Thank God few people have to drink out of cisterns these days.

There’s a lot of work to be done here. Try to filter and purify precipitation stored in the blue plastic barrels as soon as possible. Let’s not even talk about water stored 3 or 4 weeks in hot climates that hasn’t already been filtered and chlorinated.

At the first sign of trouble, purchase twice as many large plastic tarps, plastic barrels, and plastic pipes and gutters as you expect to need. All of this is very inexpensive, so there’s no need to skimp or cut corners.

Been there, done that people report that out-in-the-open, obvious water collection systems on roofs, in parks, or in parking lots are virtually as much of a threat to survivor security as sending the young men out with buckets. These collection devices are easily spotted by members of the enemy forces, who quickly learn what this is all about. Many really don’t like it.

Expect them to respond by posting sentries or by tearing up the collection system, if they can reach it. The end result is often predictable, especially when no backup collection supplies are available. You die from lack of water.

City parks with ponds and streams are found in most cities in the United States.

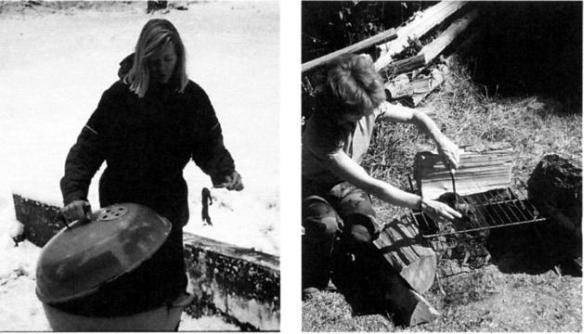

Ice and snow are sometimes sources of water for city survivors. Just hope you also have an excellent energy supply. Ice and snow as sources of drinking water are not as effective as we might wish. Very few examples of using ice and snow are on record as sources of supply for city survivors. Once melted, snow and ice water should be treated the same as any other scrounged surface water. Great quantities of often scarce energy are required to melt ice. Humans cannot normally pack in enough calories to continually exist on ice water thawed in the mouth. Ice has to be melted first or users sucking on it for hydration will risk hypothermia. Cold-weather native survivors can only use solid ice when they are on an extremely high-calorie diet of mostly animal fat.

It may be green and stale, but little ponds nestled in parks in our cities can be a source of drinkable water.

PURIFYING WATER

At the retreat, allow any surface water to stand and settle quietly in covered containers for at least 12 hours. This isn’t always possible, but it is recommended. Is it necessary to mention that water should be brought from an area of as little pollution and contamination as possible?

When the storm sewer discharge is south and north is just as safe, go north. Yet don’t be surprised when this isn’t practical. Even though this may be a time of great exposure, fill each container in as sanitary and chunk-free a manner as possible. Our practical objective is a supply of drinking water. It is nice if it has as few big brown lumps and stringy green things as possible, but the objective is life-giving water. Obviously not much water ends up hauled by the fellow who tarries overlong and is shot.

Great numbers of really slick little water purification gizmos are available, mostly from stores selling to recreational survivors, backpackers, skiers, and cyclists. All work nicely, but are expensive and not really designed for long-term city survival requiring purification of hundreds of gallons.

Using a Sand Filter

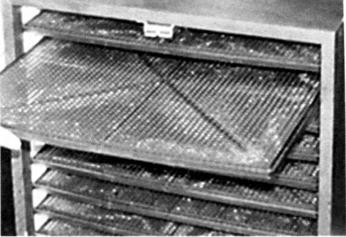

For practical survival use, we’ll need a sand filter rack. After the water has settled for 12 hours, carefully pour the top 90 percent of the water through a sturdy fine-weave cloth and then into the sand filter rack. Discard any really scummy settlings. Thoroughly clean the cloth and bucket, setting them out in the wind and sun for a day or two to purify.

Construct sand filter racks by building a box out of 2-x-10 lumber or something equivalent. Fill with coarse or fine sand. Either will work, but of course they will have much different speeds of filtration. Place the sand-filled rack directly over a seamless plastic sheet. Fastening a piece of screen from an old-fashioned screen door makes the process a bit easier and more convenient. This screen must be replaced every 60 days or so. Let’s hope the trouble doesn’t last that long.

The sand-filled rack, which could weigh almost 300 pounds, is placed on a slight angle. The plastic collection sheet slopes down into a clean collection bucket. Water poured through the 10-inch-deep sand gradually seeps through to the sheet and runs into the clean storage bucket.

Several additional maintenance chores are in sight here. Unless survivors have an endless supply of clean, new sand with which to replace that in the rack, they will have to empty the filter once a week to spread the sand in a thin layer out in the sun to purify. Sand in heavily used filters will get disgustingly grody very quickly, especially in humid, warm climates or where first settling is rushed or not done at all. Placing very many green and brown chunks in the filter degrades it faster. Carefully clean and dry the underlying plastic sheet.

There is great discussion about specific water purification methods and chemicals. True enough, most survival stores have material that can kill more little water critters than bleach. If you are so inclined, lay in a large to huge supply of this chemical now Most people, however, are going to have to use common household bleach because that is what is available and what they can afford and find.

Using Bleach

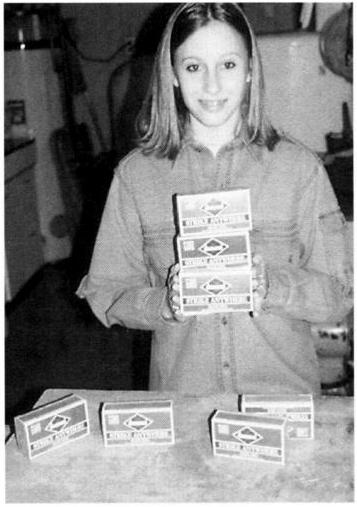

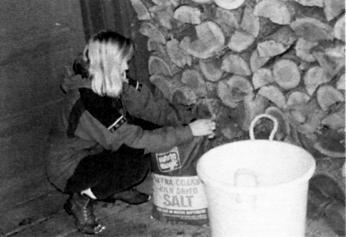

Common chlorine bleach is in a category with pickling salt for city survivors. At the first sign of trouble, clean out your local store of all you can afford, carry home, and store. It is an essential material. Any excess easily becomes trading stock.

Calcium hypochlorite, available in powder form from most plumbing and hot-tub suppliers, is also a valuable chemical for water treatment. Makers of homemade explosives are already familiar with this stuff. You need add only 1 ounce of calcium hypochlorite per 325 gallons of filtered water to purify it. The cost is about $5 per pound or 31 cents per ounce. But, cost aside, it doesn’t keep as well as the laundry bleach. The only way I know to store calcium hypochlorite is to seal it in a heavy plastic bag and then again in a wide-mouth plastic bottle. The best storage life I can get is about 18 months; after that, it swells and is neutralized as a result of sucking humidity out of the air.

Both calcium hypochlorite and sodium hypochlorite can be used to make bleach at home. Generally, survivors are best served who leave their excess hypochlorite supplies safely sealed in plastic bags and jars. But if your hypochlorite starts to go out of condition and/or there is lots of space in the old bleach bottles, consider using the chemical to top up your bleach supply.

Common bleach and hot-tub chlorinator found in many stores can be used to help purify water.

Most packets of hypochlorite purchased from plumbing or hot-tub suppliers will be about 65-percent strength. Here’s how to proceed to make bleach:

There are 128 ounces in a U.S. gallon. Two ounces of hypochlorite chemical in a gallon produces a 1-percent solution. This is not sufficiently strong—it has to be at least 3 percent. Add 6 ounces of chemical to a gallon of clean water, add the stopper, and let it sit overnight. Use this solution at the customary rate of 1 ounce per gallon to purify water. Eight ounces of hypochlorite will produce a 4-percent solution and 10 ounces produce a 5-percent solution.

Poorly filtered, dirty water requires higher quantities of bleach as well as more time to become purified. This explains why we take care to settle and filter our water. Because bleach will be difficult to impossible to replace, we will want to use as little as possible. To purify 1 gallon of water, add 1 ounce of liquid bleach (3- to 5-percent solution) and let it stand for at least 12 hours.

Some survivors I stayed with in northern Kenya rigged a large aquarium-type bubbler to aerate and purify their water. Without bleach it didn’t work well. Even with bleach, it is doubtful whether most city survivors could take advantage of this trick. When I lived in Africa, I regularly dreamed of standing in a fresh, flowing mountain stream drinking snowmelt water in cupped hands. After a few weeks of city survival, thoughts of clean, fresh-smelling, cool, untreated water will be in the category of vague dreams of a past life.

One ounce per gallon is a lot less bleach than most publications on the subject recommend. But conservation of scarce supplies is a primary goal here, and taking the time to let water settle is better than using higher quantities of bleach.

If anyone, especially the very young or elderly, acquires a dose of diarrhea, up the bleach a bit. Several M.D. types in our survival culture reckon that most Americans consume unrealistically pure foods and water. As a result, our guts are not immunized against real-world bacterial conditions. Foreign survivors who have built up an immunity have the edge on us in this instance. Don’t forget that under the best of circumstances, city survivors are going to drink lots of brown and green water. Its a given.

WELLS

For a brief time in World War I Germany, my father hauled his water from an obscure shallow well. The well was reasonably close as well as being sheltered from view Because the water was drawn from a depth of only about 20 feet, it probably contained contaminants and growies. At least these weren’t large, lumpy green and brown ones, and the family all lived through it. Then somebody stole the handpump. His mother traded for another. Somebody stole that one, too. The pump should have been taken off between uses, but it was too late. Now it was a long hike to the river.

I don’t know of a community well left in any large city anywhere in the world. In some places where there are larger, open spaces occupied by gardens, parks, backyards, or even median strips in roadways, it might be possible to drill, drive, or auger in private, shallow wells. When these are put in place, they usually provide sufficient water for a family I recently saw one not too far from the center of London. And a survivor from Atlanta wrote that he had produced a shallow well in his backyard behind a three-story apartment complex! These things do occur, but of course won’t unless survivors look for opportunities to put them in place before an emergency

Some survivors with backyards can install their own shallow wells and old-fashioned hand pumps.

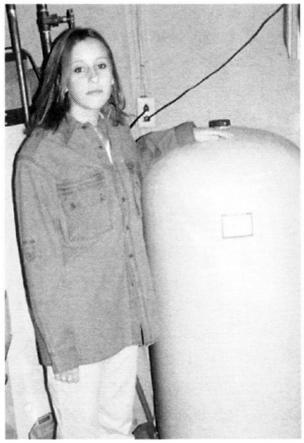

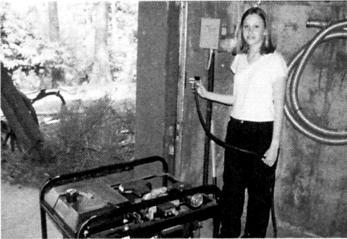

Controls and tanks for a do-it-yourself water system.

When much younger I used a gasoline engine power head that slowly turned a 2.5-inch auger shaft to drill shallow wells. It was OK technology for wells no deeper than 25 feet where the underlying material was sandy and rock free. How times have changed! Everything is more sophisticated, expensive, and certain. Deeprock Manufacturing, 2200 Anderson Road, Opelika, AL 36801, sells a small two- or three-man well-drilling outfit, complete with mud pump (to lubricate and flush out the hole) that will go down 200 feet! Other than those living in the and West, everyone is assured of water using one of these outfits. The cost is about $3,000 for their smallest model, #2000, which will even drill through solid rock. It takes two people about a day to drill their own private well. Frequently these rigs are available from rental shops. In areas where they are commonly used, a good resale market exists.

All well bores must be cased. For ease of operation and speed, use the smallest drill or auger possible that will also produce an adequate sized well hole. Bore a hole about 1 ½ to 2 inches larger than the well casing. The casing can be plastic if it will slip straight down easily. When additional pounding is required to set the casing, steel is a must. Plastic or steel, a pointed brass well screen is installed on the bottom end of all well casings. Install a well of a size on the very low end of what is common in your area—usually a 1.25-inch one.

Old-fashioned drill augers we used long ago did not have reverse. We quickly learned not to get into this business without a large, rugged set of pipe wrenches with which to back the auger out if stuck by a rock.

Standard power heads are available to rent just about anyplace in the United States. Contractors use them with 12-inch augers to dig postholes. With careful planning, it is possible to purchase 20 feet of 2-inch auger shaft that fits on these standard contractor-type power heads, allowing insertion of a standard 1.25-inch well casing.

How do you tell whether there is water at the bottom of the hole? Pour water into the hollow well pipe. If it rapidly flows away through the sand and gravel screen, there is water below.

Another detail that makes life easier for do-it-yourself well developers: Three or four 7- or 8-foot well-casing sections with appropriate connections are easier to place than trying to insert a single 20-foot length of pipe.

It ain’t easy, but shallow wells can also be driven down into sandy, rock-free ground by hand. The presence of tough clay or any coarse gravel or rock precludes using the following method, which is already so much work that I am reluctant to mention it.

The tools required are a 10-pound (or larger) steel maul, two 36-inch steel pipe wrenches, a 5-gallon water bucket, and some very sturdy boxes, logs, or scaffolds to build up a place to work from. Start with three 6-foot lengths of heavy, steel 1.25-inch well pipe. Special heavy-duty drive couplings needed to connect the pipe sections and a special drive cap to protect pipe threads while whacking away at the pipe end are also required. You will also need a special, heavy-duty well point screen made for this type of mauling. These fittings are not common, but all large plumbing shops I know of can order them. If not, try Lehman’s Hardware and Appliances, Inc., Box 41, Kidron, OH 44636. Their stuff is a bit price) but is of very good quality and fully guaranteed. Lehman’s sells predominantly to the Amish community and are very nice folks indeed to work with. I recommend paying up promptly, gladly, and without a whimper, no matter what the price.

Deploying three or four stout men, take turns pounding the point and pipe down into the ground. Two things make this marginally easier. Using the two pipe wrenches and a section of pipe over the handle, keep rotating the well pipe and point as it goes down. Keeping the pipe full of water is messy when it is hit, but will marginally lubricate the point as it goes down.

The maximum depth is 20 to 25 feet. Never assume that this will be easy, but in areas where surface water rises to within 20 feet of the ground and where there is no gravel or rock, it works like a champ. No expensive equipment is needed, there’s not much mess or fuss, and it can usually be undertaken in an afternoon. It’s all we had when I was a kid. Many wells of this type were driven right in our friends’ backyards in the middle of town.

Water can, theoretically, be pumped by hand from as deep as 200 feet using special handpumps. These and more practical shallow-well pitcher-and-stand pumps are available from Lehman’s Hardware.

What can you do if you have the opportunity to rope-haul fresh drinking water up from a steep canyon or perhaps a very deep abandoned well? Climbing down to the water may be impossible, so what to do?

Lehman’s sells a special 2-gallon bucket with a unique valve that opens when it hits the water, closing again automatically when the bucket is withdrawn. A rope the length of the drop is required. It’s lots of work using this method, but it may be the only game in town when the water cannot be otherwise reached.

Little cans or bottles of water are not practical for city survivors. The large quantity of trash they create may expose the survivors’ retreat.

STORING WATER