What if a Siberian Joan of Arc had rescued the White Armies at a critical point of the Russian Civil War in 1919?

MAID OF BAIKAL offers an alternative outcome to that war through the intervention of Zhanna Dorokhina, a young woman from the shores of Siberia’s Lake Baikal.

Like the historical Maid of Orleans in medieval France, better known as Joan of Arc, Zhanna displays a charisma and military prowess that win her command of an army to defend her homeland against the Bolshevik Terror.

MAID OF BAIKAL is a richly imagined speculation on the Russian Civil War that vividly portrays its violence, bitterness, and hardship, while telling the inspirational story of a determined young woman who perseveres in the face of overwhelming obstacles and who dies for her beliefs, not knowing whether her dreams will be realized.

Preston Fleming

MAID OF BAIKAL

A SPECULATIVE HISTORICAL NOVEL OF THE RUSSIAN CIVIL WAR

Author’s Introductory Note

Maid of Baikal tells the story of how the White Russian Armies might have deserved to win the Russian Civil War, and thus might have won, in a better world than ours. For despite the Whites’ manifold sins, the best among them strived mightily to achieve a free and democratic Russia, and most of these suffered a worse fate than what they deserved.

List of Characters

*An asterisk indicates a character who is an actual historical personage.

*Barrows, Col. David Prescott

Deputy Chief of Staff for Intelligence, U.S. Army, AEF/Vladivostok

Borisov, Boris Viktorovich (Paladin)

Standard Bearer to the Maid of Baikal

*Buckner, Col. Edmund G.

Chief Lobbyist for the DuPont Company

Buckner, Corinne

Daughter of Col. Buckner

*Chapayev, Maj. Gen. Vasily

Division Commander, Fourth Red Army

*Denikin, Gen. Anton Ivanovich

Commander, Armed Forces of South Russia (White)

*Dieterichs, Gen. Mikhail Konstantinovich

Military Advisor to Admiral Kolchak

Dorokhin, Stepan Petrovich

Father of Zhanna, Maid of Baikal

Dorokhina, Zhanna Stepanovich

Maid of Baikal

du Pont, Capt. Edmund (Ned)

U.S. Army, RRSC, AEF/Vladivostok

*du Pont, Pierre Samuel

President, E. I. du Pont de Nemours & Co.

*Embry, John

U.S. Consul, Omsk

*Frunze, Gen. Mikhail Vasilyevich

Commander, Southern Army Group, Eastern Front, Red Army

Fyodor (Bishop Fyodor)

Judge at the Maid’s trial in Ryazan

*Gaida, Major General

Commander, Northern Army, Siberian Armed Forces

*Graves, Gen. William S.

Commander, U.S. Army, AEF/Vladivostok

*Guins, Georgi (George) Konstantinovich

Assistant to Admiral Kolchak/Finance Minister

Holt, Col. Charles

Staff Officer, U.S. Army, War Department

Ivashov, Staff Capt. Igor Ivanovich

Staff Officer, General Staff, Siberian Armed Forces

*Kappel, Gen. Vladimir Oskarovich

Division Commander, Western Army, Siberian Armed Forces

*Khanzin, Gen. Mikhail V.

Commander, Western Army, Siberian Armed Forces

*Knox, Maj. Gen. Alfred A.W. T.

Chief, British Military Mission to Siberia

*Kolchak, Admiral Alexander Vasilyevich

Supreme Ruler, Commander in Chief, Provisional Siberian Government

Kostrov, Kirill Matveyevich

Zhanna’s uncle, brother of her deceased mother

*Lebedev. Maj. Gen. Dimitry Antonovich

Chief of Staff, Siberian Armed Forces

*Lenin, Vladimir Ilyich

Bolshevik Party Leader, Premier of the Soviet Union

Leo, (Father Leo)

Chief Examiner at Zhanna’s trial

*Lloyd George, David

British Prime Minister

McCloud, Mark Evans

American syndicated journalist in Russia

*Morris, William

U.S. High Commissioner to Siberia

*Neilson, Lt. Col. John

Intelligence officer, British Military Mission at Omsk

Nestor (Father Nestor)

Deputy Examiner at Zhanna’s trial

Panin, Colonel

Staff Officer, Western Army, Siberian Armed forces, at Ufa

*Preston, Sir Thomas

British Consul at Omsk

Rawlings, Lt. Col.

Intelligence officer, British Military Mission at Ufa

*Regnault, Eugene

French High Commissioner to Siberia

*Reilly, Sidney (aka Zhelezin)

Russian-born intelligence operator for Great Britain

Ryumin, Father Timofey Makarovich

Russian Orthodox priest

*Savinkov, Boris Viktorovich

Russian Socialist Revolutionary Party leader

*Sukin, Ivan

Minister of Foreign Affairs (Acting), Siberian Provisional Government

Sweeney, Jake

American Red Cross official in Siberia

*Sylvester (Archbishop Sylvester)

Russian Orthodox Archbishop of Omsk

*Timiryova, Anna Vasilyevna

Mistress of Admiral Kolchak

*Tolstov, Gen. Vladimir Sergeyevich

Commander, Ural Cossack Host

*Trotsky, Leon

Chairman of Supreme Military Council, Red Army, Politburo Member

*Volkov. Gen. Vyacheslav Ivanovich

Governor-General of Irkutsk Province

*Ward, Colonel John

Commander, Middlesex Regiment, British Military Mission at Omsk

*Wilson, Thomas Woodrow

President of the United States of America

*Wrangel, Gen. Pyotr Nikolayevich

Commander, Caucasus Volunteer Army (White)

*Yudenich, Gen. Nikolay Nikolayevich

Commander, White Russian Forces in Northwestern Russia

*Yurovsky, Yakov Mikhailovich

Senior Cheka official responsible for the Maid’s trial at Ryazan

Yushkevich, Yulia Yekaterinovna

Widowed owner of Beregovoy estate near Omsk and mistress of Capt. Ned du Pont

Musical Themes by Chapter

To enhance the reader’s enjoyment, I have created a musical score for Maid of Baikal, consisting of selections by Russian composers of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Each selection is intended to evoke the emotions of the chapter to which it is assigned.

For maximum enjoyment, I recommend listening to the chapter’s musical selection before reading. Each piece is available (with free sampling) on iTunes, and most can be downloaded without cost at Classic Cat or Wikipedia.

Chapter 1: Spartacus & Phrygia, Adagio, by Aram Khachaturian

Chapter 2: The Seasons, Op. 67, Summer, by Alexander Glazunov

Chapter 3: Valse-Fantasie in B Minor, by Mikhail Glinka

Chapter 4: Ballet Suite No. 4, I. Prelude, by Dmitri Shostakovich

Chapter 5: Masquerade Suite, IV. Romance, by Aram Khachaturian

Chapter 6: The Seasons, Op. 67, Autumn, Adagio, by Alexander Glazunov

Chapter 7: Lieutenant Kijé, Symphonic Suite, Op. 60, II. Romance, by Sergei Prokofiev

Chapter 8: Prelude in G Minor, Op. 23, No. 5, by Sergei Rachmaninoff

Chapter 9: Serenade in C Major for String Orchestra, Op. 48, Pezzo in Forma di Sonatina: Andante Non Troppo, Allegro Moderato, by Igor Stravinsky

Chapter 10: Prelude in C-Sharp Minor, Op. 3, No. 2, by Sergei Rachmaninoff

Chapter 11: Romeo and Juliet, Act I, Scene XIII, Dance of the Knights, by Sergei Prokofiev

Chapter 12: Zaporozhye Cossacks, Op. 64, Introduction, by Reinhold Glière

Chapter 13: Symphony No. 5 in D Minor, Op. 47, IV. Allegro Non Troppo, by Dmitri Shostakovich

Chapter 14: Pictures at an Exhibition, No. 10, The Great Gate at Kiev, by Modest Mussorgsky

Chapter 15: Jazz Suite No. 2, 6. Waltz II, by Dmitri Shostakovich

Chapter 16: Pictures at an Exhibition, No. 9, Baba Yaga or The Hut on Fowl’s Legs, by Modest Mussorgsky

Chapter 17: Masquerade Suite, I. Waltz, by Aram Khachaturian

Chapter 18: Mlada Suite, Procession of the Nobles, by Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov

Chapter 19: The Rite of Spring, Sacrificial Dance, by Igor Stravinsky

Chapter 20: Pictures at an Exhibition, No. 8, Catacombs, by Modest Mussorgsky

Chapter 21: Symphony No. 2 in E Minor, Op. 27, I. Largo, Allegro Moderato, by Sergei Rachmaninoff

Chapter 22: Romeo and Juliet, Act IV, Epilog, Juliet’s Funeral, by Sergei Prokofiev

Chapter 23: Novorossiysk Chimes (The Fires of Eternal Glory), by Dmitri Shostakovich

Photographs

Maps

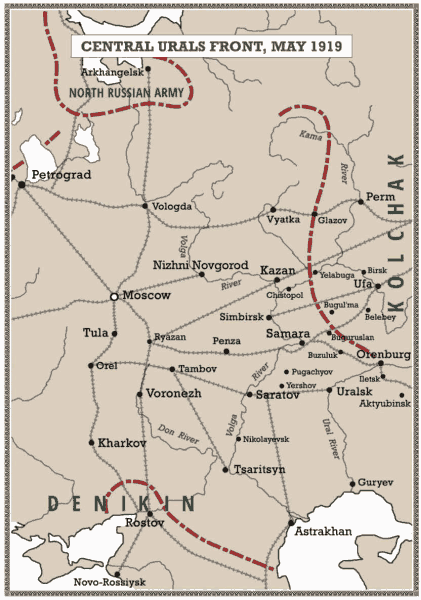

Former Russian Empire, May 1919

Russian Civil War Fronts, May 1919

Central Urals Front, May 1919

Chapter 1: Moro Rebellion

“Glory is fleeting but obscurity is forever.“

Musical Theme: Spartacus & Phrygia, Adagio, by Aram Khachaturian

NOVEMBER, 1916, MINDANAO, PHILIPPINE ISLANDS

First Lieutenant Edmund “Ned” du Pont led his U.S. Army horse platoon in single file through tangled swamp on the north coast of Mindanao Island. As the patrol slogged forward along the narrow path, the stench of rotting undergrowth filled the air. Off to the left, he noticed a dark-skinned Filipino native in mud-smeared black pantaloons emerge from the neck-high razor grass. The Filipino looked him straight in the eye, a broad smile on his face, one arm hidden behind his back and obscured by the tall grass.

Ned raised his rifle to cover the intruder, but as he did, a spear hurtled through the air from behind with a sinister whoosh, plunging through his left shoulder. Six inches of its long thin blade now protruded through the bloody front of his khaki tunic. He felt a surge of adrenalin-fed energy and, informed by years of training and hard-won experience, calculated how best to lead his men to defeat the ambush.

Suddenly a rifle shot rang out close beside him and he saw the Moro in pantaloons fall backward before he could swing his double-edged kris. Ned spurred his horse forward, shouting orders to direct the platoon’s fire at the dozen or more Moros lining the path, a motley assortment of bandits clad in loosely fitting trousers and jackets of black or brown, adorned with brightly colored sashes and chest armor of tightly woven rattan.

Most of the attackers wielded savage-looking knives or swords and only a few carried pistols or rifles. From experience, Ned knew that edged weapons were more dangerous than firearms in rebel hands, for while few Moros could shoot straight, nearly all were master swordsmen and superb athletes, easily capable of closing in fast to lop off a head or an arm before a soldier could raise his weapon to fire. And the rebels’ will to fight was rooted in a fervent belief that a devout Muslim warrior who took the life of an infidel would instantly go to heaven if killed while hacking and stabbing away at his enemies.

The Moro ambushers raced forward to attack but were quickly cut down by deadly rifle fire and close-range blasts from the Americans’ Model 1911 .45-caliber self-loading pistols, whose heavy copper-jacketed slugs were capable of stopping a charging horse in its tracks. Then, all at once, Ned felt a fresh stab of pain in his shoulder. He turned to find his platoon sergeant shouting at him to hold still as he attempted to withdraw the spear. Then, with the attack driven off and his men out of danger, Ned’s vision clouded, his strength ebbed, and he slumped slowly forward onto his horse’s sweat-drenched neck.

Chapter 2: Transbaikalia

“The good old rule,

Sufficeth them, the simple plan,

That they should take, who have the power

And they should keep who can.”

Musical Theme: The Seasons, Op. 67, Summer, by Alexander Glazunov

LATE NOVEMBER, 1918, IRKUTSK

Ned awoke with a gasp. In his nightmare, he had felt the pain of the Moro spear in his left shoulder, as he had scores of times in dreams since leaving the army hospital and returning to garrison duty in Manila. The skirmish had won him a decoration for bravery and a promotion to captain. But something inside him had changed. He wanted no more of guerrilla warfare, of the endless jungle hide-and-seek with an unseen enemy. Fighting these poor, ignorant devils was pointless. To subdue them would take decades, if it could be done at all. Not that he was battle-shy. No, he was ready to get back on horseback after falling off, but he wanted a different horse. He wanted a real war—a war like in Belgium and France. And, oddly enough, that desire was exactly what had landed him in Siberia, whose capital was roughly midway between Manila and Paris and more than three thousand miles from each.

In the light of a sputtering oil lamp, Ned looked around the rented dormitory room at the former girls’ school in Irkutsk. This was the temporary quarters where he and a dozen other Allied officers had slept on the floor for the past several nights while awaiting an American military train for the next leg of their journey to the Siberian capital at Omsk. The room’s crudely planked floor was covered with tightly packed bodies, most of them huddled around the blazing tile stove to stay warm. The air was filled with the odors of wet wool, stale sweat, alcoholic breath, and the reek of cheap Russian tobacco. Ned sat up in the gloom and rummaged in his rucksack for the evil-looking blue bottle of bootleg vodka he had bought in Chita. He took a long pull, gasped from the burning in his throat as it went down, stowed the bottle away again, and sank back into to a deep and dreamless sleep.

* * *

Ned awoke again shortly after dawn, with the sun barely above the horizon and shining diffusely through an overcast sky. By now, all but two of his fellow soldiers had departed. The last pair had staggered in after a drinking bout and had not stirred since. Ned sat up and felt a powerful itch at his wrists and ankles. In the next instant, he saw a fat louse fleeing from where he had intended to scratch. ”Lice are only lice. You don’t count them in the trenches,“ a veteran of the Spanish-American War had once told him. But lice carried typhus, and years of war had spread typhus epidemics all across Russia. Never mind, he would manage to stay healthy somehow. He had to, for he was alone in Siberia, far from any American hospital or military base. And that situation might not change until his mission was over.

Ned looked at his watch and realized that he had less than an hour to get ready before he was scheduled to meet his Russian liaison officer. Throwing on a fresh tunic, he packed his bedroll hastily, gathered his wash kit, and strode off to the lavatory to clean up for the day ahead. There would be just enough time to wolf down a bowl of kasha gruel with a mug of sweet black tea at the school’s canteen.

After breakfast, Ned sat on the stone stoop of the girls’ school dormitory and reviewed in his mind the description he had received of the man who was to be his closest companion over the coming months. Staff Captain Igor Ivanovich Ivashov[1] was two years older than Ned and, according to his file at American Expeditionary Force[2] (AEF) Intelligence Headquarters in Vladivostok, the Russian had fought against the German Army until the Imperial Russian Army’s collapse in 1917. After demobilization, Ivashov joined the centrist-liberal People’s Army in Samara, battling the Bolshevik Red Guards along the Volga until the People’s Army retreated to the Urals and he landed a staff post with the Siberian Army’s General Staff, or Stavka, at Omsk. But because of rivalries between the People’s Army and the more conservative Siberian Army, he was replaced soon after by a Siberian and shunted off to the largely ceremonial role of liaison to visiting British and American officers.

As Ned sat on the front stoop, his mind wandered and he tried to imagine what kind of man Ivashov might be. He dreaded the idea that the staff captain might be one of those overbred, foppish Russian staff officers who idled away their days behind desks while spending their nights drinking, gambling, and debauching women of the lower classes. On the other hand, remembering that Ivashov had spent years at the front fighting the Germans before taking on the Bolsheviks, Ned also feared the opposite, that Ivashov might be a stereotypical brooding Slav, prone to depression and alcoholism and ready to indulge every melancholy emotion and defeatist impulse.

Within moments, a horse-drawn droshky[3] pulled up at the school’s gate and a dark-haired officer of average height and wiry build strode into the courtyard, dressed in a fresh British uniform bearing green-and-white Siberian Army insignia. He had a lean, chiseled face with steel-gray eyes, and gave the impression of a seasoned combat officer who kept his thoughts to himself and held his emotions in check. Now this is the kind of colleague who might be useful, Ned thought, suppressing a smile as he watched the man approach.

“Captain du Pont?” the Russian inquired moments later in a surprisingly rich baritone, giving Ned’s surname a correct French pronunciation.

“Yes. Pleased to meet you,” Ned replied in passable Russian. “Staff Captain Ivashov, I presume?”

“At your service,” the Russian replied with a trace of a smile, perhaps relieved at finding that Ned, too, was an infantry officer of the battle-ready sort rather than an elite staff officer of the kind commonly found so far behind front lines.

Without another word, Ivashov moved quickly to pick up the American’s haversack and carried it back to the droshky. Ned followed close behind. Once on board, the Russian officer draped himself in a capacious sheepskin, offered one to Ned, and ordered the driver to the railroad station.

“They say you are with the Russian Railway Service Corps,[4] yet you wear an American army uniform,” the staff captain observed once they were finally on their way. “Are you a soldier, then, or a railroad man?” he inquired.

“The former,” Ned replied. After a long moment he added, “I’m an infantryman and have spent the last six years fighting rebels in the Philippines and Mexico. But, here in Russia, I’m attached to the Railway Service Corps, in military communications. Does that answer your question?”

He knew it wouldn’t, unless Ivashov was already aware that Ned’s real work in Siberia was intelligence.

Ivashov gave his head a sudden shake, as if to rid it of cobwebs.

“Not completely,” the Russian answered with an amused expression. “So you are a communications expert?”

“Of a sort,” Ned answered, meeting Ivashov’s gaze with an enigmatic smile. “I’ve had some communications training, if that counts. But the main thing is that our combat troops aren’t allowed west of Lake Baikal, while the RRSC can go anywhere the railroad goes. So if I’m to work at Omsk at all, I have to go with the RRSC.”

At this, Ivashov relaxed visibly.

“You think like a Russian,” he commented, looking away absently. “That will make things easier for you. But Omsk is another matter entirely. It’s an utter madhouse.”

“How soon till we get there?” Ned asked with a smile.

“Not for a week at the earliest. Our train has been put back another day by brigands at Chita.”

Ned’s face fell, and Ivashov must have noticed, for he brightened at once and turned around to face the American.

“Never mind the delay. I have good news,” he announced. “One of my father’s friends, the merchant Dorokhin, has invited us to spend a day or two with his family at Verkhne-Udinsk,[5] less than a day’s journey east of here by rail. I think you will enjoy the excursion and the fine views of Lake Baikal along the way. If nothing else, it will give you a better idea of how we Siberians live. But even better, Stepan Petrovich can be relied upon to spread a fine table for his guests, even in these times of scarcity.”

The station was not far away and their carriage ride took only a few minutes. But owing to a track change, they had to sprint for nearly fifty yards along the congested platform to catch the little yellow and blue train before it pulled out of the station. Despite overcrowding in every class of carriage, Ivashov somehow found a conductor who led them to a vacant first-class compartment on the north-facing side of the train, which he said would afford them an excellent view of Lake Baikal, Siberia’s gem, the oldest and deepest body of fresh water on earth. Ned watched Ivashov slip a wad of banknotes into the conductor’s hand after the latter drew the curtains to offer privacy from the corridor. Then Ivashov quickly locked the door.

“I hear that you graduated from the Nikolayevsky Military Academy,” Ned began after they had settled in, an innocuous opening to a conversation that he hoped would let him take the measure of his companion. “Did you enjoy your time there?”

“It seems so long ago,” Ivashov replied absently, giving a vacant stare out the window. “War has a strange way of distorting time and memory. I scarcely remember my time there.”

“Of course,” Ned responded with a respectful nod. “I understand completely. When I was chasing rebels on jungle islands, West Point was absolutely the furthest thing from my mind. But now that you are at the Stavka, don’t you find it useful to have other academy graduates to talk to?”

“I might, but there are very few, and none at my rank,“ Ivashov noted with a shrug. “Nearly all the Stavka officers are Siberian Cossacks. Sadly, they and I have little in common.”

“I see,” Ned responded, noting the disparaging tone of Ivashov’s last comment. “And that is because…?”

“I don’t mean to belittle anyone,” the Russian answered with a tight-lipped smile. “But Russia is a vast land, and these Siberians know only their remote part of it. And they have never faced the Red Army–only the local Red Guards, whom the Czech Legion routed easily on their behalf.”

“You also fought in the war against Germany, didn’t you?” Ned added, changing the subject yet again. “Tell me, Igor Ivanovich, how does your experience against the Germans compare with fighting the Red Army on the Volga?”

“When one is in retreat, the experience is much the same,” the Russian commented acidly. “First, we retreated from Poland and the Ukraine, and then from the Volga. The difference is mainly one of scale. Today our gains and losses are all on a petty scale when compared with the German war. What we have now is a miserable little fight, but one that goes on and on. I think that one day I shall go back to the front, if only to see an end to it.”

“I know exactly how you feel,” Ned lied, having never experienced defeat. For that, he would need to have fought in America’s Civil War, or the early battles of its Revolutionary War, when American soldiers had felt the sting of defeat just as keenly as the Siberians did now. But there was no point in going on, he thought. Ivashov did not seem in the mood for conversation.

At last, Ned heard a pure three-noted whistle, almost like the fluting of orioles, and the train finally left the station. Within minutes, Ivashov rose from his seat to excuse himself. For the next hour or more, the Russian came and went from the compartment at irregular intervals but spoke little.

Making allowances for Ivashov’s reticence, Ned limited his conversation to innocuous remarks about Vladivostok and the Allied presence there, his travels across Manchuria to the Russian border at Manzhouli, and Allied successes in keeping the Trans-Siberian line running despite sporadic incursions by Bolshevik partisans and Japanese-backed warlords. Yet, rather than warm to the conversation, Ivashov asked no questions and gave laconic answers to those Ned posed to him. When not talking, both men stared idly out the window, staving off hunger from time to time by snacking on the brown peasant bread and tinned fish that Ivashov had brought from Irkutsk.

During one such interlude, Ned summoned the nerve to ask Ivashov again about his service on the Volga Front the summer before.

“What made you join the People’s Army, Igor Ivanovich? Why not the Volunteer Army, or some other White unit?”

“Because my mother’s family is from a village near Samara, on the Volga,” Ivashov replied between bites of bread, not looking up. “It was there that I landed in the spring of 1918, after demobilization.”

“And your family opposed the Bolsheviks, I presume?”

“Everyone in our village opposed them,” Ivashov answered, bluish sparks flaming up in his eyes before dying just as quickly. “Only in the cities and larger towns did the Reds have any following.”

“Then what happened when the Red Army captured Samara, and the People’s Army was forced to flee? Was your family able to escape?”

The Russian stopped chewing and put down his bread. A long moment followed before he swallowed. When he looked up, his face was ashen.

“They escaped, after a fashion,” he replied with a twisted smile and a voice devoid of emotion. “You see, my mother and my sister were killed when our house was hit by Red artillery. Mercifully, my mother died instantly, but my sister died alone nearly a week later, in a field hospital, suffering greatly from her wounds. I was on the front lines and could not go to her.”

“I’m so sorry,” Ned replied. “That must have been…”

“No, it’s not as you think,” Ivashov interrupted with a pained expression. “I believe their deaths were merciful, in a way. They were spared far worse.”

“So, when Samara fell, you traveled east and joined up with the Siberians?” Ned continued, unsure what to say next.

Ivashov stared out the window for a long moment before answering.

“It was not so easy to break free from the Reds. And when at last I did, I felt I had nothing left to live for. Oddly enough, the thought of revenge did not even enter my mind. But I am a Russian officer, and I swore an oath to defend my country. So my choice was a simple one: I resolved to fight on until Russia is free or I am dead.”

Before Ned could conjure up a response, Ivashov brushed the breadcrumbs from his trousers and rose to leave.

“I will be back after a while. I suggest you lock the door and let no one in but me.”

Ned gave the Russian a solemn nod and watched him go. After locking the door, he re-wrapped the remaining food and settled back for the ride. Suffering from a lack of sleep owing to his late arrival in Irkutsk the night before, he let the train wheels’ rhythmic clacking lull him to sleep.

When he awoke, he looked outside his window to find the train running alongside the Angara River, Lake Baikal’s only outlet, which flowed swift, clear and cold toward the mighty Yenisei River and from there to the Arctic Ocean. Before long, snow-clad mountains loomed high in the distance and were reflected back in the clear depths of the lake. From Slyudyanka to Kabansk, the railway traced the curving shoreline, its roadbed hugging Lake Baikal’s southern edge, sometimes within a niche carved into a series of rocky outcrops that plunged down to the lake’s limpid waters. Ned watched as a pillar of smoke and steam rose into the sky and trailed behind like an endless staircase.

The further east the train traveled, and the longer Ned remained alone, the more he brooded over his decision to come to this vast and unknown land, halfway around the globe from home, and now gripped by a debilitating civil war that most Americans considered irrelevant to their interests. For reasons that Ned was unable to fathom, the U.S. Government had sent some eight thousand of its soldiers off to Siberia, not to fight, but to maintain the railways, keep an eye on the Japanese, and facilitate safe passage home for some forty thousand Czech prisoners of war. And the one activity expressly forbidden the AEF was to join the Siberians in combat against the Red Army.

Now, having traveled thousands of miles from Washington to Vladivostok and Irkutsk, Ned found himself traveling not toward the Siberian capital, but away from it, through a silent wilderness of taiga forest. Hour after hour, the train clacked on toward a destination with no military significance whatsoever. With a start, Ned seized his haversack and rummaged through its neatly folded contents for the sinister blue vodka bottle, only to find it drained. He shook the last astringent drops onto his tongue and flung the empty bottle under his seat.

Unable to sleep now and without the means to get drunk, Ned settled back in the cushioned seat to watch Siberia roll by. Over the next seventy or eighty versts,[6] the train traveled through more than thirty tunnels. All along Lake Baikal’s southeastern shore, jagged mountains edged ever closer to the water. Before the train finally left the shoreline, the lake’s surface became a great shimmering mirror as the sun sank lower and lower and then dipped below the purple mountains, revealing a half-moon sailing serenely across the darkening sky.

The final stretch of rail from Kabansk to Verkhne-Udinsk followed the Selenga River through some fertile-looking but uninhabited valleys, rimmed with stands of pine just large enough to cut for timber. But the primary impression this left on him was of Russia’s infinite vastness, its disturbing strangeness, as if alive with primitive spirits, and the utter absurdity of anyone presuming to conquer such a land in any meaningful sense.

Just after five o’clock, Ivashov reappeared as the train reached the outskirts of Verkhne-Udinsk, a modest provincial city at the confluence of two great rivers, the Selenga and the Uda. The city center lay wrapped in a bluish moonlit haze, feebly lit by a mixture of gaslights and electric streetlamps, with coils of smoke from countless chimneys corkscrewing skyward. On arrival at the station, the two young officers waited in their compartment for the flood of humanity to drain onto the station platform before they descended into the breathtaking cold and jostled their way to the platform’s far end. There, an aged Buryat,[7] dressed in a peasant sheepskin coat, felt boots, fur cap and capacious leather driving gloves, greeted them from atop a sledge drawn by a pair of stocky Yakut horses, each cloaked in dense dun-colored hair.

Ivashov greeted the driver with a terse nod and led Ned to the rear of the sleigh, where he stowed their bags, and then to a bench behind the driver that lay buried under a pile of furs and sheepskins. A shallow layer of snow covered the frozen ground. As the sleigh edged forward, the snow scrunched crisply under its runners. From this sound, and from the dense clouds of steam pouring from the horses’ nostrils, Ned estimated that the temperature was at least twenty degrees below freezing. By the end of the ten-minute sleigh ride, Ned’s face was so numbed by the cold that soon he was barely able to speak.

On arrival at the Dorokhin estate, the sleigh passed through an arched entrance gate that swung into a pine-shaded compound resembling an Asiatic caravansary. Inside the high timber fence, and lit by weak electric lights, was a sprawling one-story house of Siberian style with a steeply pitched roof and windows framed by carved whitewashed shutters. The dwelling was constructed entirely of huge logs, while the exterior walls and eaves were decorated with elaborate scrollwork and wooden cutouts. Elsewhere within the compound stood workshops, storerooms, a carriage shed, a dairy, and neatly kept stables heaped with straw.

A portly man of about fifty awaited the travelers at the door. He wore a long collarless tunic of cream-colored linen that was buttoned at the throat and belted at the waist, along with loose-fitting trousers, high black leather boots, and a sheepskin cap and vest. Despite his rustic appearance, the man’s pale blues sparkled with intelligence and Ned felt immediately attracted to him.

“Don’t just stand there in the cold,” their host bellowed in a loud, jovial voice without introducing himself. “Come in and get warm. Dinner is ready soon!”

En route, Ivashov had described Stepan Petrovich Dorokhin as a respected member of the entrepreneurial class in Verkhne-Udinsk, a successful trader and the owner of a salt works, distillery, and grain mill. Dorokhin and his recently deceased wife had raised three grown sons and an adolescent daughter. He was accustomed to entertaining all manner of guests at his home, ranging from Mongolian camel drivers to high-ranking Russian and foreign officials.

Dorokhin brushed Ivashov’s cheeks twice with his bushy mustache in the local manner of greeting before doing the same for Ned. Then he led his visitors into a vestibule hung with sheets of thick felt to block the cold, and from there into a spacious hall lined with split-log benches. Everywhere the interior walls consisted of whitewashed logs, still rough where the axe had cut, and packed with straw and moss between the chinks. Faded velvet curtains covered the windows. On the polished floorboards lay wine-red Central Asian rugs of tribal design. Along the walls to left and right hung a series of Siberian landscapes painted in oil and several mounted stag heads. In a corner stood a polished walnut gun rack stacked with ancient and modern long guns.

But the most prominent feature of the room was the massive white tile stove along the far wall, a wood fire blazing within. Three guests were already seated in leather armchairs enjoying the warmth. Close by stood a tall sideboard laden with savory zakuski[8] and a steaming brass samovar and, at the center of the room, an oaken refectory table set for eight. In a distant corner, candles flickered before a silver cross and a gilded icon showing the tranquil visage of St. Vladimir.

Dorokhin led his two newest guests to the stove and offered them seats on cushions atop tile benches flanking the fire.

“Now we shall get to know one another!” their host declared, rubbing his hands with glee. “Allow me to introduce Staff Captain Igor Ivanovich Ivashov, the son of my dearest school friend, may God bless his soul, whose family hails from Irkutsk.”

Ivashov made a perfunctory bow and acknowledged each of the other men with a nod and a smile.

Now pointing to an elegantly suited Russian in one of the armchairs, Dorokhin added, “This is my brother-in-law, Kirill Matveyevich Kostrov, also of Irkutsk. He is the director of the Russo-Asiatic Bank here, though he grew up in St. Petersburg and cannot truly be considered Siberian.”

The banker, whose face was flushed and sweaty, rose unsteadily to his feet and greeted each of the two visitors with a limp handshake. At his elbow stood a half-filled bottle of Caucasian brandy and a nearly empty snifter atop a side table of cherry wood.

“Also with us tonight is Father Timofey Makarovich Ryumin, until recently our beloved parish priest, but now a man of the world, so to speak, having launched his own movement to foster a spiritual rebirth among the Siberian people. Father Timofey stems from the distinguished Ryumin family of Old Believers, who came to Siberia in the seventeenth century. The Ryumin family name is held in high respect by all in Transbaikalia except, perhaps, for the Bolsheviks.”

The latter comment brought a questioning smile to the long face of the priest, who looked about thirty years old and whose eyes blazed a deep lazuli blue. To Ned’s surprise, the cleric remained seated and Ned noticed no brandy glass beside his armchair. Even without rising to his full height, Father Timofey cut a striking figure, wearing an untrimmed black beard, long unkempt hair, and an ankle-length cassock of fine gray wool with black embroidery along its buttoned side flap and cuffs. As if suddenly noticing Ned’s attention, Timofey cast a questioning glance at the American and for a moment conveyed the impression of a panther crouched and ready to pounce.

Dorokhin continued.

“And I am honored to have as guests two distinguished Allied officers: Lieutenant Colonel John Neilson, of Her Majesty’s Middlesex Regiment, on assignment to Admiral Kolchak’s staff at Omsk; and Captain Edmund du Pont, of the American Expeditionary Force, who is traveling to Omsk with Staff Captain Ivashov. As always, we are deeply grateful to our foreign allies for their support against Bolshevism. So let us bring out the vodka and drink to the health of our guests!”

At this, Ned offered his host a respectful nod.

“Zhanna!” the Russian shouted down the corridor a moment later. “Can you hear me, girl? Come at once with a fresh bottle and glasses!”

Ned was exchanging greetings with Lieutenant Colonel Neilson, a tall, narrow-faced man whose eyes appeared unfocused and whose speech was slurred, when he heard the clink of glasses and a heavy bottle being deposited on the sideboard behind him. He turned to follow his host and came face to face with a slender teenaged girl, dressed modestly in a beige linen apron over a dark ankle-length woolen skirt and a long-sleeved pleated white blouse. Her face struck him as uncommonly handsome, with eyes wide apart and slightly protruding, a well-shaped nose, a resolute mouth with an ironic upturn at the corners, fair skin and thick jet-black hair that was pinned, twisted, and piled into a luxuriant roll atop her head. But there was something in her good looks that transcended mere form, for her violet-gray eyes conveyed such a childlike purity of spirit that, when she smiled at him and a blush rose to her pale cheeks, she exuded an effortless charm that put him instantly at ease.

“Ah, Captain du Pont, permit me to present my daughter, Zhanna,” Dorokhin stepped in. “She is my youngest, my infant, the only child living at home, now that her older brothers have left us for military service. In the spring, God willing, Zhanna will complete her studies and fill in for her brothers in the family business. A brighter girl you will not find in all of Siberia! When the war is over and her brothers return, God willing, they will have to look sharp or Zhanna will be the one giving the orders!”

Ned fixed his gaze on the girl, prompting her to blush even more deeply than before. Then she offered him a smile so bold and confident that she seemed to have grown inches taller.

“I am most pleased to meet you, captain,” the girl replied with a quick curtsey before removing from the sideboard the lacquered tray she had brought in.

“But not as much as I,” Ned replied, bowing politely. “Your father is indeed blessed.”

“You speak Russian well,” the girl observed, facing him again, her eyes showing a flicker of curiosity. “How did you come to learn it? Do they teach Russian in your schools as they teach French and English in ours?”

“My sister and I had a Russian nanny when we were children,” he answered, feeling self-conscious that his command of the language remained rusty despite practice and too-frequent resort to an English-Russian military dictionary. “Olga was like a second mother, though she was not much older than you when she came to America.”

“Oh, what an adventure that must have been!” Zhanna exclaimed, raising herself on tiptoes with enthusiasm.

“Study well, Zhanna, and you, too, may have the opportunity to travel abroad when the war is over!” her father added proudly. “A modern woman’s place is no longer at the hearth, I always say.”

Then, as if by an afterthought, Dorokhin seized the bottle of pale pink rowanberry-infused vodka his daughter had placed on the sideboard, uncorked it, and sniffed its vapors eagerly.

“Ah, the finest! Now, let us be seated. The time has come to break bread and drink.”

Dorokhin stood at the head of the table and directed each guest to his seat, with Neilson, Ned, and Zhanna to his right and Kostrov, Father Timofey, and Ivashov to his left. The seat at the foot of the table remained empty, though the place was set, perhaps in the hope that one of Dorokhin’s sons might appear at the last moment. Once all were seated, Dorokhin said a brief prayer of thanks, and then proceeded to pour a glass of vodka for himself and his immediate neighbors before passing the bottle down the table. While the vodka was making its rounds, Zhanna rose to assist the family’s middle-aged housekeeper in relaying more platters of food from kitchen to sideboard to table. As the girl passed by, Ned could not resist casting an idle glance at the well-turned ankles that popped out from beneath her skirt.

Such an abundance of delectable food Ned had seldom seen, even at his wealthy relatives’ houses in Wilmington. Having become accustomed to tinned beef and biscuits aboard the troop ship from Manila, and to the simple fare of tea, kasha gruel, boiled eggs, watery broth, and black bread at the various cheap restaurants and railroad buffets he had frequented to date in Russia, Dorokhin’s table was a most welcome sight. For laid before him were platters of roast duck filled with apple-and-bread stuffing, pan-fried sturgeon from Lake Baikal, tinned salmon roe, stuffed cabbage, tiny meat dumplings in broth, boiled beets and carrots in butter, sautéed wild mushrooms, steamed fiddlehead ferns, loaves of freshly baked white and brown bread, and all manner of pickled vegetables.

When all but Timofey and Zhanna had a glass of vodka before them, the host rose.

“Let us drink to the health of our visitors, binding us in our common desire to win freedom and self-determination for the Russian people!”

Ned poured the chilled vodka straight down his throat in the Russian manner, scarcely tasting it. The sensation was not at all unpleasant, but knowing how many glasses of the stuff would likely follow before the night was over, he reached for the stuffed cabbage and began loading his plate. To eat heartily while drinking, he had learned, was the best defense against vodka’s pernicious side effects.

Silence prevailed while the guests piled their plates high with food. What followed was a leisurely and enjoyable meal, in which the heady vapors of vodka assisted to break down barriers of language, class, and culture. Soon each person began to ask his neighbor questions without waiting for answers, and to answer questions without waiting for them to be asked.

As if in response to a string of compliments from his guests about the quality and abundance of the food set before them, Dorokhin launched into an extended monologue about the myriad war-related shortages that had developed since the Great War, the February and October Revolutions of 1917, and the outbreak of civil war between Bolsheviks and Whites. And following all those, he explained, came the drought and catastrophic crop failure that struck Transbaikalia in the summer of 1918.

“Yes, we have enough to eat today in Verkhne-Udinsk,” the host went on between spoonfuls of broth. “But even we feel shortages coming on. Before long, I fear, we may even face famine. The war with Germany disrupted everything, and then the Reds made it all worse. And now, the new Siberian government wants us to drop everything to fight the Bolsheviks!”

At this, Kostrov, Father Ryumin and Ivashov offered grave nods, while Neilson stared darkly into his vodka glass and Zhanna squirmed uncomfortably while picking at her food.

“You see,” Dorokhin continued, “in a country of such enormous distances, the vital question is transport: how to move goods from areas of plenty to areas of want. And only by superhuman effort has Russian distribution been able to compensate for its worst deficiencies. Since 1914, a creeping paralysis has struck Russian economic life owing to the strangulation of freight.”

To Ned’s left, Neilson poured himself another glass of vodka while Father Timofey and Ivashov busied themselves with their food. Ned guessed that all had heard some version of the lecture before. Suddenly Dorokhin paused to stare straight at Ned.

“I understand that you are a railway expert, Captain du Pont. Is that correct?”

“I serve with the Railway Service Corps, but I am not a railroad man by profession,” Ned replied guardedly, laying down his knife and fork. “My specialty is communications: telegraph and wireless, which the railroads need in order to function. And it appears that communications across Siberia are in no better shape than the rail lines.”

“Then improving transport is not simply a matter of more locomotives and rolling stock?” the banker Kostrov inquired, fork in hand, looking up from his heavily laden dinner plate.

Ned hesitated and felt relief when their host stepped in to answer.

“Shortages of locomotives and carriages are only a symptom,” Dorokhin asserted, setting his vodka glass on the table for emphasis. “You see, most of our Russian locomotives are antiques, fit only for a museum. Presently, Russia possesses only one quarter of the number of locomotives that in 1914 was barely sufficient to maintain her railways in an abysmal state of inefficiency.”

“Surely you exaggerate, Stepan Petrovich,” Kostrov interrupted. “Could it truly be that bad, Captain du Pont?”

All eyes turned to Ned. At that moment, he was taking a drink of water and nearly choked on it.

“You’re both right,” he answered guardedly, setting down his glass and assuming an authoritative air. “That’s why the Railway Service Corps is bringing in so many new locomotives and freight cars. A completely new American train is en route here from Vladivostok even as we speak.”

“Aha! But locomotives aren’t the half of it!” the elder Dorokhin went on, unwilling to be placated. “It’s been four years since the fighting began, and all across Siberia our rails and roadbeds are in a dreadful state, the lathes and machinery needed to make repairs are totally worn out, and the skilled workmen to carry out the repairs have been killed or conscripted by the thousands.”

Ned looked across the table and saw that Neilson and Ivashov had put down their forks and were listening with renewed interest. Ned did the same.

“You see, my dear captain,” Dorokhin resumed with an appreciative smile, “before the war with Germany, Russia imported vast quantities of agricultural implements from abroad: not just large combines and machines, but simple tools like axes, sickles shovels and scythes. By the time of our revolutions in 1917, domestic production of such tools ceased almost entirely. All over Russia, spades are worn out, men plow with burnt wooden staves rather than plowshares, and axes and saws are so worn out as to be useless.”

Now even Father Timofey came back to life, furrowing his brow with heartfelt concern for the Siberian peasant. And Zhanna appeared close to tears. Ned’s look met hers for a fleeting moment and, before she turned away, her violet eyes seemed to convey the limitless compassion of youth.

“But things are so much better here in Transbaikalia than in Omsk and Yekaterinburg,” Neilson pointed out in a skeptical tone. “Here you have a wide variety of foods at a fraction of the price in Omsk. Yet you fear famine?”

“Well, perhaps not for the moment,” Dorokhin conceded, resting his thick hands on his hard round belly. “The Transbaikalian peasant eats rather more today than he did during the war with Germany. But he has no matches, no salt, no new boots or clothing. Worse still, in the cities, there is no fuel or medicine, no soap or cloth. Houses fall into disrepair for lack of paint and plaster. Offices are without paper and pencils. And the trickle of goods entering the stream of commerce is diverted immediately from factories and co-operatives to the front.”

“You paint a dismal picture, Stepan Petrovich,” Dorokhin’s brother-in-law answered at last, all eyes now centered on the banker. “But what is to be done? We can’t simply stop the war and let the Bolsheviks take control. The Cheka[9] and the Red Guards would kill every last one of us! My cousin arrived here last week after escaping from Petrograd.[10] He told me the canals there are clogged with the decomposing bodies of merchants and nobles executed during the Red Terror. In the past month alone, he said, the city’s population has declined by one hundred thousand souls. One hundred thousand! No, dear brother, our only hope is to battle on to victory, whatever the cost.”

“So, tell us, is the bad news all true?” Dorokhin pressed, gazing with dispirited eyes first upon Neilson and then Ivashov. “What hopeful news do you bring us from the front? What do you hear of Admiral Kolchak’s plans for a spring offensive?”

The British officer, as if having awaited such an opening, spoke up at once without bothering to look across the table to see if Ivashov wished to speak first.

“The matter is simple enough, gentlemen,” Neilson declared, putting down his vodka glass with an unsteady hand and scanning the faces of his audience through bloodshot eyes. “The White Army must defeat the Reds within a year or our side will almost certainly collapse, leaving all of Russia in Bolshevik hands and setting the stage for massacres, starvation, epidemics, and slavery on a scale not seen in modern times.”

Neilson paused to let his message sink in. The other men seemed to hold their breath for an instant, while Zhanna’s face turned a deathly white.

“The Reds, too, have their share of difficulties,” he went on, “but their advantages are many: they hold a territory with five times the population of that held by the Whites; they have moved swiftly to seize what remained of the tsar’s arsenals and arms industries; they have had at least six months longer than the Whites to build their armies; they possess interior lines of supply with a well-developed network of rail lines and waterways; and, most importantly, they are unified behind a single political and military program.”

Ned was impressed that a man so obviously in his cups could deliver so concise a summary. Rather than befuddle his wits, the vodka seemed to have sharpened his tongue. Even Father Timofey’s expression showed respect.

“But what of the Allied blockade and the food and fuel shortages in Red-held cities? And the outbreaks of cholera and typhus?” Kostrov shot back. “And, tell me this, how can the Red Army hope to win battles without a competent officer corps?”

Neilson let out a bitter laugh and swirled a scarred forefinger idly over the rim of his empty vodka glass.

“The Reds still have rail lines open southward to the Caucasus. And smugglers bring in food from Finland, Estonia, Poland, and the Ukraine. Even the epidemics play their part, killing off the aged and the weak, thus leaving more food and fuel for the able-bodied. As for officers, the Red Army learned this past summer not to entrust their divisions to amateurs, however politically reliable they might be. Since then, they have enticed or coerced thousands of former Imperial Army officers into leading Red Army units, with Chekists and political commissars hovering over their shoulders to thwart disloyalty.”

Neilson paused here and cast a meaningful glance toward Ivashov, who turned away.

“What he says is true,” Ivashov added after a moment, looking at Ned as if to justify himself. “Any imperial officer trapped last winter behind Red lines faced conscription or death. I nearly faced that fate myself…”

Ned recalled Ivashov’s comment on the train that it had not been so easy for him to break free from the Volga. But before Ivashov could say more, Neilson hammered home his point.

“As a result, my friends, the Red ranks abound with battle-tested enlisted men, sub officers and officers who are totally committed to the Red cause. Contrast that to the Siberian Army, which refuses to accept troops with war experience out of fear that they have been infected with the Bolshevik disease. As a result, the White officer corps is ridden with parasites and incompetents, while the soldiers under their command are mostly teenaged conscripts, untrained and unwilling to fight, who desert at the first sight of combat.”

“So, tell us, who will win?” Father Timofey asked leisurely, apparently unafraid to receive an honest answer from the British officer, who, after all, was not obliged to stay behind and bear the consequences if the Whites should lose.

“Maybe Lenin, maybe Kolchak, maybe neither,” Neilson answered with a shrug. “Russia is rapidly slipping into anarchy. What she needs is good honest leadership, the rule of law, land reform, and individual liberty. But neither the Bolsheviks nor the Old Guard will provide any of that. So, it comes down to the fortunes of war, my friends. One general will beat another on some far-flung battlefield, and the war will be decided in a manner no more just than a coin toss.”

Father Timofey let out an awkward laugh, which drew disapproving stares from his host and from Kostrov. Ivashov remained impassive during the exchange while young Zhanna stared at Neilson in open-mouthed shock.

“But surely, Lieutenant Colonel Neilson,” the priest challenged, “Admiral Kolchak is not a monarchist; he does not intend to turn Russia back over to the wealthy landlords and factory owners. We have all read his manifesto of last week, in which he promised as much to the nation. I can repeat to you the very words from his address: ‘I shall follow neither the reactionary path nor the path of party strife. My chief aims are the organization of a fighting force, the overthrow of Bolshevism, and the establishment of law and order, so that the Russian people may choose their own form of government.’ Surely those are not the words of a monarchist. Wouldn’t you agree?”

“They are the words of a dictator, Father Timofey,” Neilson replied gravely. “While he may be a fine, brave man, a patriotic Russian, and arguably the best one for the job, Kolchak leads a military dictatorship in Omsk and would not last a single night in that cesspool of intrigue if he did not maintain the loyalty of the officer class. And, if you will excuse my candor—for the vodka seems to have loosened my tongue—the officers who put him in power are monarchists, their leaders self-seeking and corrupt, while those officers under him who favor democracy face being purged if they dare raise their voices above a whisper.”

At this, Ned noticed Ivashov turn pale and, without waiting for another toast to be announced, refill his vodka glass to the brim. Ned couldn’t help but wonder if the staff captain might be one of those very democrats. He thought of Ivashov’s reticence aboard the train that afternoon and resolved to dig deeper into the man’s history.

By now the host had noticed that the bottle of spirits was empty and called for Zhanna to fetch another. The girl rose to leave, but not before giving her father a reproving look. Ned’s eyes followed her graceful figure as she headed for the door.

“No, Zhanna, our guests have certainly not had enough,” Dorokhin commented loudly before she left the room. “There are times when too much to drink is barely enough,” he added in an undertone after she had gone.

“Amen, Stepan Petrovich,” Kostrov added. “Vodka is the anesthetic by which we endure life’s painful operations. In times like these, may our supplies never run short!”

On Zhanna’s return, her father called for the new bottle to be uncorked and passed around. The girl cast a worried glance toward Ned, as if he might somehow delay the bottle’s progress, but before she had even set the bottle on the table, Ivashov swallowed hard and addressed Neilson in a clear and surprisingly sober-sounding voice.

“And what is to become of the democrats, Lieutenant Colonel Neilson?” Ivashov demanded. “Now that Admiral Kolchak has become Supreme Ruler with the blessing of our Western allies, what will be the fate of the Socialist Revolutionaries and Constitutional Democrats? After all, they won the Constituent Assembly elections in 1917, took up arms with the Czech Legion against the Bolsheviks, and joined forces with Omsk after being pushed back from the Volga and across the Urals. Now that Admiral Kolchak rules Siberia, what influence will men of the center have in his government?”

“The Socialist Revolutionaries?” Neilson scoffed. “Let me tell you about the Socialist Revolutionaries. I spent an evening in a railroad car with Mr. Avksentiev and company in September, and I can tell you this much: from what I saw of the S-R leaders during the old interim government, those dreamers would put Russia at no less risk than a band of out-and-out anarchists! Before Kolchak, crime was rampant in the streets of Omsk, murders and armed robberies a nightly occurrence, and the socialist-led municipal councils ruined everything they touched. I commend the Admiral’s forbearance in granting Avksentiev’s ilk safe passage into exile rather than shooting them down like dogs. In his place, I doubt I’d have been as forgiving.”

Ivashov’s eyes flashed with anger at Neilson’s tirade against the S-Rs. Ned also noticed that Father Timofey, who was seated beside Ivashov, twisted his fork in his hand and looked down at the table with clenched teeth. Even when Neilson went on to launch a new conversational thread, the staff captain could not let the matter rest.

“Lieutenant colonel, one more question, if you please,” Ivashov interrupted in a ringing voice. “Is it your considered opinion that Admiral Kolchak will ultimately defeat the Red Army and drive the Bolsheviks out of Russia?”

“That is still possible, but I wouldn’t lay odds on it,” Neilson replied with an audible sigh that seemed to acknowledge Ivashov’s annoyance.

“And will you tell us why?” Ivashov pressed.

“Yes. The reason is this,” the Briton answered, suddenly lowering his voice and regarding Ivashov with sympathetic eyes. “For all the Admiral’s virtues, he is a sailor: that is, a species of civilian. He is no field commander and has neither great leadership qualities nor a record of military victory. What the White Army requires at this critical stage is a commander in chief no less brilliant than a Caesar, or a Napoleon, or a Hannibal Barca.”

“Or perhaps a…” Father Timofey began.

At that moment, Ned happened to be staring in fascination at Zhanna’s delicate forearm, its shape altered subtly by the pressure of the table beneath. When he raised his head, he noticed the blushing girl shoot a reproachful glance at Timofey, as if he were about to betray a secret.

* * *

Dorokhin kept insisting that his guests eat until they were incapable of moving, and the men continued to down glass after glass of vodka, some as toasts and others by mere reflex, until their knees went weak. Despite having loaded up his stomach with fatty dishes early in the meal and diluted his vodka with water on occasion when no one was looking, Ned noted his words slurring, his memory for Russian words and phrases receding, and his mind becoming slowly paralyzed.

Mercifully, around that time Zhanna emerged from the kitchen with a layer cake topped with a confiture of bird cherries that grew wild along the riverbanks of Transbaikalia. While she busied herself serving a piece to each guest, her father fetched a bottle of Caucasian brandy from the sideboard, filled his empty snifter from it and passed the bottle to Neilson.

Ned waited for Zhanna to reach him and, when he was within the orbit of her scent, inhaled deeply, detecting notes of lilac over the kitchen smells permeating her apron and skirt. Upon taking a mouthful of the cake she gave him, he found it delicious, with a flavor oddly like chocolate.

On impulse, Ned rose from his seat, lifted his glass, and offered a toast.

“I shall always remember this night,” he began, “for the hospitality of our host, the beauty of the setting, the intelligent conversation of the guests, and the skill and grace of those who prepared and served us a meal beyond compare. Thank you, Stepan Petrovich—and Zhanna Stepanovna!” He offered a bow and a smile to Zhanna before raising his glass to his lips and downing the contents.

She returned his smile with a bashful look that set his heart pounding. Was it the vodka, or was he becoming infatuated with the girl? Of course, such a thing could not possibly lead anywhere, but all he knew at the moment was that he wanted to see more of Zhanna, to drink in her scent and peer into to those lavender eyes.

In the next instant, the housekeeper began clearing the table and Zhanna rose to help her. Meanwhile, Ned’s words had prompted a final long-winded toast from Dorokhin, at which the other guests rose unsteadily to their feet and polished off whatever vodka or brandy remained in their glasses. Afterward, the guests shook each other’s hands with exaggerated bonhomie and tottered out of the room.

Zhanna joined the handshaking and, as Ned filed past her, she extended a delicate hand. Upon taking it, Ned felt a small folded slip of paper pass from her palm to his and acknowledged it with a nod. Meeting his gaze, she slowly withdrew her hand and followed her father out the door.

* * *

The next morning, Ned awoke at first light with throbbing temples, an urge to vomit, and the sickly sweet odor of his own alcoholic sweat filling the small bedroom. With a mighty exertion of will, he swung his legs over the side of the bed and planted his feet on the floor to stop the room from spinning. After a moment, he drew a bucket of breath as if from a deep well, rose to his feet, and shuffled across the room to where he had laid his wristwatch, catching a glimpse of himself in the mirror.

He put his head up to the mirror to take a closer look. Though his eyes were bloodshot and his skin of sallow hue, his brain and body still functioned reasonably well and he knew he would have to move quickly if he was to be on time for his rendezvous with Zhanna. He made his toilet quickly, then dressed and set out for the dining room to greet his host and explain his incongruous desire to take a stroll outdoors before breakfast. He found Dorokhin seated at the dining table with Ivashov and Father Timofey. The first two seemed in remarkably good repair for men who had imbibed so much vodka the night before. Though the aroma of fried bacon and eggs from the sideboard made Ned’s gorge rise, he put on a brave grin and poured himself a cup of strong tea at the steaming samovar.

“Eat, my young friend!” the merchant urged. “It will drive out the evil spirits.”

Timofey, who had not touched alcohol the night before, let out a hearty laugh. “And if that doesn’t work, I can offer you my priestly blessing. Or perhaps, being American, you would prefer a dose of Mesmerism? I trained in it some years ago and have often achieved good results with men in your condition.”

Ned resented being treated like a drunken Russkie. To make matters worse, he considered Mesmer and his animal magnetism[11] a complete fraud. He was considering a sharp riposte when he thought of his rendezvous with Zhanna and forced a mirthless smile.

“Thank you, Father, but I think what I need at this moment to restore my appetite is fresh air and movement. If you’ll excuse me, I think I’ll take a short walk and rejoin you in a while.”

“I recommend the horse path behind the stables,” Dorokhin suggested as Ned downed his tea. “It runs to the edge of our property before joining the main road to town. Zhanna went off in that direction a short while ago. Perhaps you may come across her along the way.”

At that remark, their host exchanged glances with Ivashov and Father Timofey, winked, and suppressed a smile. But Ned had turned aside to dispose of his teacup and failed to notice.

The walk to the cedar grove, which occupied a rise at the edge of the Dorokhin estate, took less than a half hour. Once within the grove, Ned followed a set of fresh footprints to the foot of a massive cedar, where he found Zhanna seated cross-legged on a Buryat prayer rug laid upon the snow. Her eyes were closed but her lips moved as if she were praying. Not wanting to disturb her, he halted twenty feet away and watched.

Zhanna was dressed in a sheepskin coat, heavy wool trousers, thick felt boots, and a white rabbit-fur cap with long earflaps. Ned’s breath caught at the sight of her, for he had seldom beheld a face as serenely lovely. At that moment, Zhanna Dorokhina seemed too beautiful for this earth.

As if sensing his presence, the girl’s eyes opened and looked straight into his.

“I’m sorry I’m late,” he stammered. “I’m afraid I overslept. Your note said…”

“I’m so very happy you came,” she interrupted while removing her cap and fur mittens and laying them across her lap. Unlike the night before, her sleek black hair was tied behind her head in a long ponytail and shone in the pale sunlight. “Another hour of sleep might have suited you better, I expect. Thank you for not thinking me a silly schoolgirl.”

At a loss for words, Ned changed the subject.

“Were you dreaming just now?” he asked. “You seemed to be holding a conversation with someone.”

“I was,” she answered without hesitation.

“But nobody else is here.”

“Perhaps not in the usual sense, but my Voices are as real to me as you are. This is where I come to speak with them.”

Ned hesitated. To him, hearing disembodied voices was the definition of insanity. Yet, the girl seemed far from a lunatic. He ventured a polite response.

“Your Voices? Do they, well, have names?” he asked.

“Of course. You might already know them. Are you a Christian?”

“Not a very good one, I’ll confess,” Ned responded, stepping closer. “But I was raised an Anglican and read the Bible quite a bit as a boy.”

“Then perhaps you have heard of Saint Yekaterina of Alexandria? Or Saint Marina[12] of Antioch?” she asked with an expectant look.

“Their names don’t sound very familiar,” Ned answered. “Are they the ones who speak to you?”

“Yes, and the Archangel Michael, sometimes. But he is a newcomer,” she answered with a mischievous smile. “Saint Yekaterina has been with me since I was thirteen. Saint Marina for not as long; she comes and goes as she pleases.”

“What sort of things do they tell you?” Ned asked with genuine curiosity as he seated himself on the snow beside her.

“Oh, at first they told me to be a good girl and go to church,” she answered with a musical laugh.

“And later?”

“They gave me instruction in spiritual matters to help me prepare for the work that lay ahead,” she went on.

“And how can you be sure the voices really belong to saints and not to…”

“…my imagination?” she interrupted with a frown.

“Or impostors who might aim to deceive you.”

“Oh, my Voices could not be from the Deceiver,” the girl answered. “The Bible says one should judge a tree by its fruit, and nothing but good has ever come to me from my Voices. They have taught me so much that sometimes I fairly reel from it!”

“Well, what you say sounds innocent enough,” Ned conceded, not wanting to cast judgment on another person’s religion. “I am hardly fit to question it, since no saint has ever taken a personal interest in the likes of me. As a soldier, I doubt very much whether…”

“Oh, but there you are wrong!” she interrupted again. “Archangel Michael cares a great deal for soldiers. He says that before long I may become one. And that is something that strikes fear deep in my heart. Tell me, captain, have you ever fought in a war? Have you seen death at close hand?”

Ned let out a deep breath before answering.

“I have,” he answered in a flat voice. “In Mexico and the Philippines. And I have the scars to prove it.”

“Were you very afraid?” Zhanna asked eagerly, leaning forward with her elbows propped on her knees.

“Afraid of what?” he asked.

“Of dying. What else?”

“Of course,” Ned answered with a shrug. “I feared that, and being wounded, and the snakes and spiders, and getting lost in the jungle, and a lot more. I was afraid just about all of the time.”

“Then how could you go on fighting? Where did you find the courage? Why didn’t you flee, as many of our boys do?”

“One fights mainly because of the training, I suppose,” he said, idly picking up a handful of snow. “And to not let down one’s comrades. And sometimes conditions become so impossible to bear that death becomes a matter of indifference. When that happens, risking one’s life means very little.”

A look of incomprehension spread across the girl’s pale face.

“But why do you ask? And why me?” Ned probed. “Have you also asked this of Ivashov?”

“I ask you because you are a foreigner,” Zhanna answered with a grave expression that made her look older than her eighteen years. “I dare not ask a Russian man because they have certain ideas about women that will never change. And as for Staff Captain Ivashov, he is completely loyal to my father and uncle and would repeat anything I say right back to them.”

“But surely, a girl like you will never find herself on the battlefield. Have your Voices told you otherwise?”

“Not exactly,” Zhanna answered after a moment’s hesitation. “But they have a mission in mind for me, and I don’t know yet what dangers it may bring.”

“What sort of a mission?”

“They want me to travel without delay to Omsk to deliver a message to Admiral Kolchak. My father told me you plan to go there soon. I want you to take me with you. I can pay…”

Here Zhanna stopped short and watched for Ned’s response. He had expected some small, frivolous request that he could fulfill at little cost. But this request was preposterous. Still, there was something compelling about her that made him want to help.

“Ivashov and I travel to Omsk under official orders, on an American military train,” he answered respectfully, rubbing his icy hands together. “I’m afraid no sum of money can buy civilian passage on it. But tell me this: does your father know of your plan?”

“Yes. Father forbids it,” Zhanna answered without blinking.

“And you would defy him?” Ned challenged. “By what right?”

“Not by right, but by authority. My Voices command it, and their commands must be obeyed, for they come from God.”

Zhanna’s demeanor appeared so sane that Ned struggled for a counter-argument that did not take her for a fool or a madwoman. After all, the Russians were a devoutly religious people and, in desperate times, religion and ancient folkways often tightened their grip on the devout.

“And you have no doubt of this?” he demanded.

“Not a whit.”

“Then, what would you do once you reached the capital? These days Omsk is thronged with soldiers and refugees and Bolshevik agitators. It’s not a safe place for a country girl all on her own. And how would you gain an audience with the Admiral? He is protected by British bodyguards at all times and rarely ventures from his quarters except to visit the front lines.”

“Perhaps you could arrange an introduction,” she ventured in a quiet voice.

Ned laughed, not in a mocking way, but with the easy confidence that arose from knowing he held the upper hand. For while God might have given Zhanna an order, He had not presented her with a plan, and the task was plainly impossible.

“Would that I could,” he answered amiably. “But I have never met Admiral Kolchak, and I am no more likely to gain an introduction than you are.”

“I see,” Zhanna replied, biting her lower lip and wringing her fur gloves in her hands. “But you would help me if you could, wouldn’t you? My Voices assured me of that much.”

Ned laughed.

“Well, in that respect, your Voices are quite right. For if I could help you without any harm to you, or disgrace to your father, or neglect to my duties, I would most gladly come to your aid.”

This was an exaggeration, of course, but he would have been genuinely delighted to help her if the request were not so evidently absurd.

“Then I shall take up your offer in due time,” the girl answered with renewed confidence. “For my Voices tell me that you will return here before the winter is over. So if I do not travel with you now, I shall surely do so on your return.”

“And I would be most happy for the chance to see you again,” Ned replied, meeting her gaze with a weak smile.

“Then go with God, captain,” Zhanna added in a clipped voice as she rose to her feet. “And may we meet again soon. For I have but a year and a little more to do my work. By this time next year, Russia’s die will be cast, and so will mine.”

* * *

Stepan Petrovich and his guests spent that afternoon shooting grouse and quail amid the stubble of the harvested croplands, returning at dusk for a light meal washed down with nothing stronger than beer. Zhanna assisted with the cooking and serving, as she had the night before, but declined to join the men in the dining room, eating in the kitchen instead. Nor did she serve them food or drink later that evening while they played skat and whist by the tile stove.

The next morning, Zhanna rose early to help the housekeeper prepare breakfast but left for church before the men rose. She failed to return before Ned and Ivashov took leave of their host and set off for the railroad station. Clearly, Ned thought, the girl was avoiding him. Perhaps she was embarrassed at revealing her visions. Or perhaps she had second thoughts about appearing to lead him on, given that he was much older than she and a man of the world.

She was only a schoolgirl, after all, barely eighteen, and Ned did not want to show disrespect for her father or Ivashov by making improper advances. Perhaps it was a good thing that Zhanna had stayed away and that he would be leaving soon. If they were alone together again, and he touched her, he might not be able to stop himself.

He needed to shake this infatuation with the girl. It had taken him completely by surprise, catching fire like a spark in dry grass. After all, he had been without female companionship for four months. It was time he found a woman his own age, fraternization rules be damned. Once he was on his way to Omsk, the infatuation with Zhanna would burn out, and they would probably never cross paths again.

Only after he and Ivashov had settled into their private compartment and their train was clattering over the rails toward Irkutsk did Ned venture a comment on Zhanna’s absence all day and relate the odd story of his conversation with her among the cedars.

“Can you imagine a stranger story?” Ned asked.

Ivashov looked up from his newspaper and shrugged.

“I find it just as odd as you do. While I don’t doubt that she hears voices, I have no idea what they mean. Yet there is something special about the girl. And I expect we haven’t seen the last of her, for it’s clear that she won’t rest until she makes her way to Omsk.”

“And why do you say ‘we’, staff captain?”

“Because she made the same approach to me when I spoke with her yesterday before breakfast,” Ivashov answered with a hearty laugh. “And my response was no different from yours.”

* * *

Father Timofey was the last guest to leave the Dorokhins’ estate. Stepan Petrovich had already gone into town on business and Zhanna had not yet returned from church. Timofey was saddling his horse in the stable when he noticed Zhanna standing beside him.

“Back from prayer so soon?” he asked her with a kind smile.

But Zhanna’s face remained expressionless, almost brooding. Her hands were dug deep into the pockets of her heavy sheepskin coat.

“So they refused you?” he asked while he spread a thick saddle blanket across the horse’s back.

“Yes, both of them,” she answered in a monotone.

“Yet you’re certain theirs were the faces you saw in your visions?”

“Without a doubt.”

“Do you suppose they could be persuaded to change their minds?” the priest asked as he lifted the saddle onto the blanket.

“I don’t see how,” she answered dully, shuffling her feet idly in the hay. “You saw for yourself, they return to Omsk without me. How am I to ever get another chance with them?”

“Did you ask that question of your Voices?”

“Of course I did, Father.”

“And what did they say?”

“They said not to worry, that both men will come again. The time was not right, but it was necessary to try.” She stepped forward to hold the horse’s bridle and stroke the beast’s forehead.

“And what if one of these men does take you to Omsk, either now or later? What if you succeed in reaching the Admiral? What then?” the priest asked, giving her a sharp look with his deep blue eyes before letting the cinches and stirrup straps fall across the horse’s flanks.

“My saints say it’s not been decided,” she answered, looking away in frustration.

“Not decided whether you are to remain in Omsk or return here? Or might they send you to some other faraway place? In any case, who would look after you while you are away? How could your father possibly allow such a thing?”

“I don’t know,” the girl replied with downcast eyes.

“Did any of your saints or angels imply that one of these officers might become your guardian or protector beyond Omsk?” Timofey demanded, catching her eye before he turned away again to tighten the cinch. “Perhaps even your husband?”

“Certainly not the latter!” Zhanna bristled. “Yekaterina says I am to keep myself pure. There will be no bridegroom for me but Christ, at least until my mission is complete.”

“And how long is your mission to last?” Timofey asked in conclusion, as he turned to Zhanna with the reins in his hand.

“A year and a little more. It will not likely end at Omsk, and may take me to the front. Yet the longer I delay, the greater the peril when I go…”

The priest offered her a sympathetic nod.

“Patience,” he said, before leading his horse past her and out of the stable.

Chapter 3: Change of Plan

“Wherever the standard of freedom and Independence has been or shall be unfurled, there will be [America’s] heart, her benedictions and her prayers. But she goes not abroad in search of monsters to destroy. She is the well-wisher to the freedom and independence of all. She is the champion and vindicator only of her own.”

Musical Theme: Valse-Fantasie in B Minor, by Mikhail Glinka

FLASHBACK: EARLY AUGUST, 1918, WASHINGTON, DC

Ned had been to the State, War, and Navy Building before, but never on business of his own. He vaguely remembered being taken there as a boy to see his father decorated for his service in the Philippine Islands during the Spanish-American War. The massive cast-iron building, faced with stone, had been built in the 1880s in the Second French Empire style and stood just west of the White House on Pennsylvania Avenue. Ned recognized the massive skylights above the main stairwells that had impressed him during his first visit, and the elaborate decorative trim, including doorknobs with cast insignia representing the government department to which the door belonged.

He mounted the staircase and took the stairs two at a time until he reached the War Department’s offices on the third floor, where he was scheduled to meet with Colonel Charles Holt, an old friend of his father’s who had once been the latter’s fellow instructor at West Point. Ned found the office without difficulty and entered an anteroom. An orderly found Ned’s appointment in the calendar and led him to the colonel’s office, a spacious room brightly lit by morning sunshine streaming in through outsized south-facing windows.