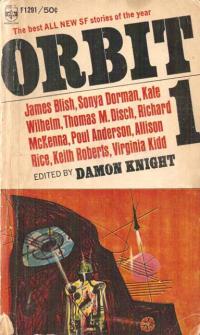

Orbit 1

By Damon Knight

Scanned & Proofed By MadMaxAU

Introduction

Here are the nine best new science fiction stories I could find in eight months of reading manuscripts. I did not know when I started what kind of stories I was looking for: all I had in mind was to try to put together a collection of unpublished stories good enough to stand beside an anthology of classic science fiction.

As this collection grew, I discovered what I was looking for by finding it. These are stories by master craftsmen. They are about something; they are not the sort of stories you forget as soon as you have read them. They are as entertaining as any story written “purely to entertain”—but they do more than that. Every one is a voyage of discovery into strange places of the universe and of the human psyche. Every one has that quality of unexpected tightness that marks a really good story. By my count, there are three brand-new ideas in this collection, and six brilliant variations on old themes, from the Earth colony on another planet (“The Disinherited”) to the arrival of aliens on Earth (“Kangaroo Court”).

In the normal course of things, if there had never been an Orbit 1, I believe you would have seen these stories in anthologies anyhow — after magazine publication, in three or four years. But why should you have to wait? Here they all are, now, fresh and new, in one book.

DAMON KNIGHT

KATE WILHELM’S first science fiction story, “The Mile-Long Spaceship,” has been reprinted three times in the nine years since it was written. Here is one which I think will prove equally durable. It’s a very human story, even though its hero is tentacled and shaped like a tulip.

STARAS FLONDERANS

By Kate Wilhelm

The great ship had picked up an uneven coating of space debris. Her once silver sides were scabrous with the detritus of ancient collisions and explosions: planetary, stellar, galactic rubble that had been hurled out from high-velocity impacts, or from the even more furious paroxysms of novas and supernovas to hurtle through space until the minute gravitational field of the ship netted speeding dust motes and drew them to her sides. A gaping rent on one side of her, and many dents and scars, told of blind passage through the littered reaches. The ship was spinning erratically, not on her own axis to give interior gravity, but with a lopsided, over-her-left-shoulder tumble. There was still enough silver left for her to reflect some of the starlight when the patrol boat first sighted her visually.

She had been a blip on the scanner a long time before she was close enough to view on the screen. The three men watching her were silent while she tumbled twice; they were satisfied that she was the dead ship they were after. A luxury liner had first spotted her. The captain had made no attempt to board, but had plotted her course and filed a report.

“She’s right on schedule,” Conly said. His voice was harsh and abrupt. He was big, more than six feet tall, two hundred pounds or more, with bold features — a too-large nose, square thrusting chin, ears that stood away from his shaved head, a high heavy forehead, and wide gray eyes that gave him a false look of feline cruelty. He was in command of the Fleet scout craft.

As Conly turned from the screen, Malko, the second man watching, whistled softly between his teeth. Shorter than Conly, he was more massive, with a great heavily muscled chest, bulging biceps and leg muscles, spatulate fingers. His legs, arms and chest were covered with black curly hair. He had a curling beard and heavy, black eyebrows. His eyes were dark blue; there were many crinkle lines of laughter on his face, about his eyes.

The third man was not a human. He was Staeen, the Chlaesan observer. He, also, turned from the screen and watched Conly take his place before the controls. Staeen was much shorter than either of his companions, although, if he chose to, he could elongate himself to their height. Staeen drew his mantle closer about his body and flowed toward his own couch. He was shaped like an inverted tulip when he gathered his mantle about him. The mantle looked like dark gray leather. Under it his body parts were soft and pink; his brain was encased in more leathery covering, as were his tentacles. His eyes were close to his body now, but they could extend; the eyeballs had transparent protectors over them. His upper half served as a sense organ, like an ear, with the inner parts complex mazes of tubes, membranes, chambers. The organ allowed him to feel vibrations well above and below the human range of hearing. Staeen knew that his human companions were considered handsome among their own kind; he was beautiful in the eyes of his people. When he got to his couch he flowed up onto it, then let himself settle down to a slightly raised mound of leather. He sealed the mantle.

“Ready?” Conly asked. They would accelerate to approach the derelict, lock onto her and investigate from her stem to her stern.

Malko grunted, and Staeen said, “Let’s go.” Under his mantle there was a small two-way radio that had been modified so that it amplified his chest vibrations and translated them into sounds that were intelligible to the humans.

Conly brought the small scout closer to the great ship, matching her speed until they were side by side. The slow tumble of the crippled ship caused her to wobble as she turned over. She had passed through a region of heavy dust and rocks; the damage done to her was extensive, with several holes in the forward section where the engine room and controls were located. Conly cursed harshly. Malko grunted, glanced at Staeen and said, “Lifeboat pods are empty. She’s abandoned, all right.”

“They left her on manual,” Conly said. “If she’d been on automatic, the computer would have dodged all that junk. She must be hotter than hell.”

He began the approach maneuver, guiding the scout toward the rear of the big ship, away from the engine section and the radioactivity. Malko and Conly made a good team. Staeen felt wave after wave of worry come from Malko, while Conly sent nothing during the difficult approach. It took skillful handling to bring the small boat to the right place, but he edged in, first a foot at a time, then inch by inch until it seemed they could reach out and touch the other ship. Staeen watched with admiration as the ship started to come nearer them, her tumbling motion completing the maneuver. Conly adjusted the controls, lifting the scout slightly, and when the two met, the jar was so slight that it might have been imagined rather than felt.

“That’s that,” Conly said, locking the scout in place magnetically. “Let’s eat first, then board her and see what’s what.”

While the two humans prepared and ate their rations, Staeen turned from them to gaze out the port. Unlike species most often preferred not to watch one another partake of food, or perform other bodily functions. He knew his mouth parts were disgusting to the humans. Under his mantle his tentacles fed capsules into the pink mouth parts that moved rhythmically, and he stared with delight at the unwinding scene passing before his eyes. The tumble of the ship that they now shared seemed gone; all motion had been imparted to the stars about them, but it was a curious motion. It was as if a black velvet cloth were being carried past him, making a slow twist, then settling very slowly downward. It was all very unhurried and leisurely. It was a new way of looking at space.

His people had known space for thousands of years, so long that they no longer regarded it as a thing to be conquered. They were almost as much at home in space as they were on the surface of their worlds, or in the depths of their oceans. Evolution, in fashioning their mantles, had adapted them to any environment, even, for short lengths of time, to a vacuum. Because they always adapted themselves rather than their surroundings, and because of their generosity and open good will, they were much loved by the various races of the galaxy.

When the Flonderans had come to Chlaesan, they had been greeted with friendliness and amusement. So eager, so impulsive, so childlike. The name Earthmen was rarely used for them; they remained the Flonderans, the children. It amused Staeen to think that when they had still been huddling in caves, more animal than man, his people already had mapped the galaxy; when they had been floundering with sails on rough seas, engrossed in mapping their small world, his people already had populated hundreds of planets, light-years away from one another.

When the Flonderans had burst on the Galactic scene, enthusiastic, vocal, boisterous even, they had been welcomed as children. Suspicious, prepared for rejection, for animosity, warfare, they had been met with patience and love. The Chlaesans loved the little Flonderans. The Chlaesans pitied the intelligent, short-lived Flonderans who had neither the longevity to learn from and enjoy what they found, nor the collective cooperation of a colonial organism that could ultimately share fully every experience felt by any part of itself.

It was doubly amusing to consider that the mathematicians and philosophers had proved that a race so short lived, so individually contained as the race of Flonderans could not possibly have been viable, and being viable could not possibly have advanced to the degree of intelligence that permitted space travel.

Blithely the Flonderans pushed on and out, oblivious to the dangers of space, to the improbability of their being in space. They went wearing guns, but they seldom had occasion to use them. This sector of the galaxy was peaceful, had been peaceful for thousands of years.

“Staeen,” Malko said suddenly, “haven’t your people ever come across a derelict like this?”

“Not just like this,” Staeen said. “Not just left empty. There have been ships with plague, accidents, other-life aboard, but not one where they simply left it.”

“This is the second for us,” Conly said. “This is how they found the first one — lifeboats gone, ship damaged by space after the crew left.” His voice sounded brutal. “Staeen, why don’t you stay here? This is our problem.”

Staeen was not made for smiling, and they could not feel the sympathy he was sending. He said, “Your problems are our problems now, Conly.” Affection-waves washed over him and his pink parts under the mantle glowed red with pleasure.

Malko made a deep throat noise that was untranslatable. “Stay with us, you hear? Between us. We don’t know what we might find in there. You understand?”

Staeen understood. They wanted to protect him. He quivered with pride and happiness. He said, “I am under your orders. Whatever you say.”

“Okay,” Conly said. “We suit up and go in through the airlock. We’ll have to put the rad-suits on. Some of the ship’s hotter than hell.” He looked doubtfully at Staeen. It made them uneasy that the Chlaesans needed no spacesuits. “Will you know when you should get the hell out?”

“I’ll know,” Staeen said, his voice gentle through the apparatus that sent the sound to the two men. While they suited up he thought of the comparative lifetimes of the two species. He had been fully adult when Rome was building an empire, and now thousands of years later, the Flonderans, who could expect to die in what was to him a flicker of a tentacle, were being solicitous of him. They were born, matured, died in less time than it took for his world to make one swing around its sun. Malko called him; they were ready.

They left the scout and floated along the big ship’s hull toward the airlock. Conly was familiar with her design and he led them through the outer door to the first of three chambers. The outermost one had been damaged, but the other two were functioning perfectly, and the radiation from space dropped to normal by the time they had gone through the last.

The ship was a standard transport-passenger model, discontinued seventy years ago. The emphasis had been on transport with this model; the corridor was narrow and closely lined with oval doors, some of them open to show cramped sleeping quarters, three hammocks to a cubicle. In some rooms television screens were uncovered, as if the watchers had only stepped out for a beer. Papers on a tabletop drew Conly: an unfinished letter to a girl-friend. In the mess hall the tables were set, waiting for the crew. The feeling of overcrowding persisted.

The tumble of the ship caused a slight pull of centrifugal force so that the men were constantly shifting their positions, now having one of the door-lined walls “down,” now the floor, then the ceiling. They went in single file with Staeen between them. Conly led them through the ship, corridor after corridor of the oval doors, up stairs when they found that the elevators were not working, more corridors. Everything they saw appeared in perfect order, neat and clean, except for one or two places near portholes, where Malko picked up a chess piece and a plasti-book. Only where meteorites had struck and entered, some lodging, some passing through and out again, was there actual disorder.

Finally they approached the control room. Conly’s radiation detection unit clicked angrily. “Malko, keep watch. I’ll go in,” he said.

“And I,” Staeen said. He could not see either of their faces, but they were sending washes of courage and bewilderment. He wished he had hands with which to pat and soothe them. He caught a wave of regret from Malko who pushed himself backward to hang, drifting gently, away from the hot area of the door.

Conly motioned to Staeen to follow and passed through the doorway into the control room. Staeen could feel the radiation like a warm yellow sun against his mantle; presently there was a change in the makeup of the covering and he could no longer feel anything through it.

“What the—?” Conly muttered. A fire had raged through the control room. Black dust dotted the space they moved through, the flakes stirring when they were touched. Conly studied the control panel that was left, cursing under his breath. “Like I thought,” he said. “The sons of bitches didn’t even set it on automatic, just walked away from it. None of the safeties operative. . damn fools. Explains the radiation in here.”

Staeen floated from him toward the next door that led into a safety corridor surrounding the engine room. He was stopped by another flow of radiation. The change in his mantle was longer in coming this time, the feeling of sun-warmth stronger. Conly followed him.

“No,” Staeen said, “it is too hot even for the suit.”

Conly worked a panel back from the wall and they both looked through the thick window that had been bared, through the corridor and into the engine room. A large meteorite lay in the corridor, lodged between the two walls; smaller ones had hit in the engine room. The ship turned, and one of the rocks slid from its resting place, moving very slowly to stop against the ruined machinery of the engines. Staeen felt a flare of warmth as it hit. He touched Conly gently with his rippling mantle, and they backed away from the window together.

* * * *

Three days later, after their fifth trip inside the ship, as Staeen relaxed in his special cubicle where a five percent saline-ammonia mist played over his mantle, he listened to Conly and Malko talking.

“You can put it together,” Conly said. “Something happened and they left, just ran out, leaving everything exactly as they were using it. No safeties on, no automatic controls, nothing. The ship was empty when the meteorite hit the engine. The alarm system went off, but no one was there to do anything. It’s still in alert condition. Another meteorite knocked out the controls for it, shorted the wiring and caused the fire in the control room.”

Staeen sighed. A layer of his mantle sloughed off and was flushed away. He turned off the mist then and joined the Flonderans. He felt very well and healthy. His mantle was shiny-black now.

“You okay?” Conly asked. He was standing at the port; he turned when Staeen came in, and at Staeen’s affirmative ripple of his mantle, he again directed bitter eyes toward space as if hoping to see the answer there. “Why? Why would the captain order the ship abandoned? Did he order it even? Not a sign of attack. No weapon out..”

“Capture of the entire crew?” Staeen said.

Conly shrugged again. “They would have put up resistance. You’ve read our psychology books, and our histories. You’ve been out on five recon missions with Malko and me. Do you think Earthmen are cowards?”

Staeen knew they were not. Fear, if present, would beat against him like a storm tide on an open shore. No such waves emanated from them.

“If they had been threatened, they would have fought,” Malko said. “If they had to outrun something, why the lifeboats? Why not the ship itself? There was nothing wrong with it! Nothing! All that damage was done after they left, because they left.”

Conly returned to his contour seat, kicked it and then let himself drop to it. He stared at the control panel and said heavily, “Let’s give her one more going over, then we turn back.”

Malko grunted; his fingers combed through his beard abstractedly. Staeen could feel their disappointment and restlessness. Like children, he thought again. If they could not have the answer, they did not want the question. Unlike his people who loved paradoxes and puzzles for their own sake, the Flonderans merely grew annoyed with unanswered questions. It was because of their short lives, he decided. They knew they could not afford the thousands of years it sometimes took to find the answers.

“How many small craft were aboard the mother ship?” he asked.

Conly shifted to stare at him. His voice was a snarl when he said, “We should have thought of that! They took every lifeboat, scout, landing craft, everything! There were eighteen to twenty lifeboats and half a dozen other miscellaneous craft aboard. They knew they couldn’t last more than four days in the landing craft….”

“Even the repair boats,” Malko said. “They’re gone. Six hours, eight at the most in space in one of those. .”

Staeen looked at the hairy man and felt waves of dread coming from him. Six to eight hours in space, then death from anoxia. He shuddered inside his mantle.

Brusquely Conly said, “Okay, let’s get back. This time we split up and go through the private quarters. Try to find a note, a scrap of paper, a scrawl on the wall, anything that might give us a clue. Staeen—”

“I too can search,” Staeen said.

* * * *

Alone inside the great ship, Staeen let himself go, let it come to him. Hanging in a corridor lined with the oval doors, he thought of nothing, not even the sensations he received. He looked like a black shadow unanchored to reality as he hung there, shiny black slowly changing to a duller shade as his mantel adapted to the radiation. From a distance he felt echoes of doubts and apprehensions: Malko’s waves.

From another direction came fainter wafts of determination mixed with the same doubts, and perhaps even a touch of fear, formless and unnamed as yet. For a brief time he was one with the ship: unguided, unmanned, alone in space on a course that would take it beyond the galaxy to the nothingness that lay between the oases of life. He shuddered with the ship, feeling the vibrations of the metal under impacts from meteorites, sharp-edged bits of metallic ores set loose in space to roam forever until captured, or destroyed.

He felt the weight of the galaxy resting on himself as bits and pieces of space debris hit the ship and clung, giving it added mass. He knew that one day there would be enough mass so that planetoids could be captured, and under the pressure the ship at the core would be crushed and finally molten. It would sweep the path of its trajectory and its gravitational field would reach out farther and farther, insatiably then, and in a million years, or one thousand million, it would be caught by a hungry sun. Resisting for a while the end of its freedom in space, it would refuse a stable orbit, but in time it would become a captive like all planets. Staeen wondered if it would give birth to creatures who would pose questions of cosmology, wondering at the earth below them, at its origin, its eventual death.

Staeen continued to hang in the corridor, and now sensations too faint to be identified drifted into him. The temptation to strain to receive them better was great, but he resisted; it would be like straining too hard to hear a whisper only barely within hearing range. One either heard it, or did not. He let the feelings enter him without trying to sort them.

Emotions had been expressed with every footstep, with every grasp of a door handle, every yank on a drawer, with every shout and curse uttered by the men preparing to abandon the ship. The ship had vibrated with a different tempo of the emotions, and some of the vibrations still echoed along the molecules. Staeen intercepted them with his body and, after a long time without movement, he stirred, his mantle rippling slightly as he shifted his position. A great sadness filled him because he knew the answer he had found could not be accepted by the Flonderans. In the madness of fear the crew had left the ship.

What, or whom, had they feared to the point of insanity?

Staeen pondered that as he started to investigate the rooms assigned to him. He expected to find nothing, but his search was methodical. He had offered to help to the best of his ability and would do so.

He found nothing in any of the rooms he searched. Now and again a stronger wave of the same crawling, irrational fear bathed him when he opened a door that had been closed since the ship was abandoned, but there was nothing to indicate its source.

Malko and Conly were depressed and irritable when they returned to the scout. Staeen soaked in his mist of salt, ammonia and water blissfully while the Flonderans unsuited and decontaminated their suits. The three gathered in the cabin afterward.

“I’m going to call it a bust,” Conly said, running his hand over his shaved head. He looked tired and dejected.

Malko simply nodded. Scowl lines cut into his dark face and his deep eyes were shadowed. “Read about ocean ships being found like that,” he said. “It looked like everyone just quit whatever he was doing and jumped over the side. No explanation ever given, far’s I know.”

“We’ll make our independent reports as usual then,” Conly said. He looked at Staeen. “Will you add whatever impressions you got from her?”

Staeen agreed. He gazed from the port at the ship, an unsteady pad beneath the small scout. She would sail on, not worth salvaging, keeping her wobbling course toward the rim of the galaxy, and her mystery would go with her beyond recall.

Two days later the scout was streaking back toward her port when a blip appeared on the scanner screen. Malko, at the controls, decelerated and he and Conly watched the blip.

“Shouldn’t be one of ours,” Conly said. “This is a hell of a long way off course for any place we’d want to go.” He kept his eyes on the growing blob of light on the screen. The object was almost close enough now for a visual sighting. “How about your people, Staeen? Any reason for them to man a ship and come out here?”

Staeen wriggled his tentacles with excitement. “It must be the regular visit of the Thosars,” he said, his voice cracking with emotion. “I was a boy during their last visit. They come bringing news of the galaxy, exchanging new ideas. They make a regular sweep of the galaxy every twelve thousands of your years. .”

Malko and Conly stared at him. Neither had seen him so excited before. His mantle rippled uncontrollably and his tentacles were a blur of rosy motion.

“And are they friendly?” Conly asked. A grin broke out on his face even as he asked. Staeen’s pleasure was so undisguised that to imagine the Thosars as other than friendly was ridiculous.

Throughout the next hours the ship drew nearer to them, changing on the screen from a blob of light to a pale blue, wheel-shaped ship that was bigger than anything yet made by the Flonderans. Staeen radiated such joy and happiness at the approaching visit that the Flonderans echoed it and the small scout fairly hummed with the vibrations. Conly and Malko gaped at the size of the wheel; it had a diameter of seven miles. They demanded Staeen tell them everything he could about the Thosars.

“Just like you, like Flonderans, only bigger, much bigger,” Staeen said happily, staring at the wheel rolling through space toward them. “When they come, they visit everyone simultaneously, they have so many ambassadors. Every city, every hamlet, all receive them together. There is a festival, a party that lasts until they depart once more. Their scientists and ours share future dreams; they share discoveries concerning space, as we do with them. . ” He couldn’t continue. Silence fell within the small craft.

The blue wheel drew closer, occulting star after star with its approach. Conly returned to his contour seat and watched the radar. “They’re going to smash us,” he said nervously.

“It fills the sky,” Staeen said joyously. “A blue ring in the sky, and then the force fields like silver balls. .”

“It’s stopped now,” Conly said, cutting in. He adjusted a dial. “Two miles away.”

An opening appeared in the nearest rim of the wheel and three silver globes glided away from it.

“When they get closer you can see inside them,” Staeen said. “They can’t board us, you know. Too big. They’ll pull abreast, invite us to enter their ship.” He wished the two men could share his happiness, could partake of the ecstasy that was rippling his mantle. To be a passenger in the legendary blue wheel of the Thosars! The globes drew closer, dancing through space, circling one another, bounding apart, leap-frogging. Soon they would be close enough for the Thosars within them to be seen. Staeen did not breathe during the last seconds. Even his vibrations stopped. He saw them first; they were signaling.

Conly’s voice jarred him. “They’re only seventy-five feet away!”

“It is as I said,” Staeen cried. “They wish to take us aboard, let us return to Chlaesan with them. Conly, blink our lights-”

One of the Thosars, clearly visible now behind the screen of energy, reached out and touched the scout. It turned. Another of them swam slowly past the port. He was as long as the three-man scout craft. His pale golden body glowed, the magnificent center eye studied them benignly, the great mouth curved in a welcoming smile. He arched away and back again, as a great fish turns in water, lazily, without effort. His face pressed against the port, filling it, too large for it.

Staeen turned triumphantly toward Malko at his side.

“See, just like you, only bi—” He stopped, wracked with pain. There was insane horror on Malko’s dark face; his eyes were bulging, his mouth partially open.

Staeen was hit by slamming, staggering waves of terror such as he never had felt before. He cried out under it, but his cry was not heard. Malko screamed hoarsely, and before he could get to his contour seat, before Staeen knew what was happening, the scout shot forward with a brutal acceleration.

Malko crashed to the floor. Staeen fell also, and writhed in pain, his own and Malko’s. Malko had hit his head against the metal floor and was unconscious, but his brain was sending out urgent pain messages. The pain waves were on a level apart from the mounting, smothering, thundering waves of fear. The g’s increased and Conly lost consciousness. The paralyzing waves of fear diminished. Still the scout accelerated.

Staeen knew they would be killed by the continuing acceleration. Whimpering softly, he started to pull himself across the floor to the control panel. His body had flattened to a six-inch mound and moving was agony. As he passed Malko he saw blood trickling from his nose and mouth. Staeen was leaving a trail of blood behind him. There had been no time to prepare for the sudden acceleration; small ruptures had opened before he could adjust. He blanked out all of his thoughts then except the one guiding him to the control panel. He got to his own seat and was unable to crawl up into it. Conly was stretched out, his face smashed-looking, bleeding. Slowly Staeen dragged himself up Conly’s legs until he could reach the controls. He decelerated. Moments later Conly awakened.

The fear came back, stronger than ever. Conly hissed something at him and tried to push him aside. Staeen flowed over the control panel, blocking Conly’s attempt to accelerate again.

“I’ll kill you!” Conly said hoarsely, sobbing the words. He was oblivious of the blood streaming freely from his nose, seemed unaware of the pain in his chest and stomach when he moved. Staeen felt it more strongly than he did. He lunged at Staeen, who flowed away from the clutching fingers. On the floor Malko stirred. Before he opened his eyes he started to scream.

Conly lurched across the scout and grabbed suits from the storage compartment. He let one of them drop on Malko and started to climb into the other one. Malko, sobbing violently, both with pain and fear, began pulling the suit over his legs. He was shaking so hard that his feet missed the openings several times.

Staeen did not know how either man could move after the ordeal their bodies had undergone. He dared not open the blanking inhibitions he had imposed on his own body. Conly was almost finished when his hand closed on the short-nosed laser gun all Flonderans wore when they went out in space. He stared at it wildly, saw Staeen and fired, screaming obscenities at him. Staeen sealed off the injured part and dropped to the floor. He tried to speak to them, but could not. His voice box had been destroyed when he was flattened by the acceleration.

He was shuddering uncontrollably; he tried to blank out the fear waves, and failed. He gathered his mantle about him and sealed himself within it, then waited. The Flonderans had both gone mad, beyond reach. All he could do was wait. He thought of the thousands of eggs he still retained; carefully, not attracting the attention of the madmen, he deposited them on the underside of the contour seat

Neither man spoke, but occasionally one or the other made an animal noise deep in his chest. The noises filled Staeen with dread.

Their actions were wholly automatic as they fumbled with the suits, driven by their glands and not their brains now. Before Conly pulled on his helmet and face mask, his eyes swept the cabin: they were animal eyes, maddened by fear, all traces of the rational submerged. The crazed eyes saw Staeen and Conly’s hand groped for his gun. He had dropped it. He snarled and started to cross the cabin toward Staeen. The fear waves crashed against Staeen. Malko was reaching for his laser. They would kill him, maybe destroy the eggs on the bottom of the seat.

Staeen moved toward the airlock. Malko’s hand dropped away from the gun. Both men yanked their helmets in place and stumbled to the airlock.

Malko opened the outer hatch; he held Staeen’s mantle with his hand and jumped, pulling Staeen after him. Staeen caught a brief glimpse of the other human tumbling alone in space, then he was gone. The scout flashed away from them, like the great silver ship, streaking away toward the black that lay between the galaxies. Staeen felt the radiation from space like a warm sun on his mantle, then it was gone as he made the necessary adjustment. Malko held him several minutes before he released his hold, and, firing his belt rockets, left Staeen.

For a long time Staeen drifted without thought. He caught no glimpse of the Thosars, or their pale blue ship, nor of the scout. He did not expect to catch a glimpse of either of the two men. Scattered, he thought, in three different directions, the little boat in the fourth. He rested and thought alternately until he knew what the missing bits and pieces were. He was not built for smiling, but if he had been his smile would have been sad and understanding.

He recalled the psychology books of the Flonderans, so full of categorical statements, so certain of the rightness of the theories that guided them in their daily lives. It was said in those books that Earthmen had no innate response mechanisms.

Staeen fluttered his tentacles under the mantle that was slowly turning dull. He felt very stupid; he should have guessed at the start. He recalled the text, and the experiments with chickens raised for many generations with no exposure to chicken hawks, only to have the tenth generation, or the fifteenth generation react with the same blind panic when exposed to the bird as its distant ancestors had. Had anyone ever tried them after four hundred eighty generations? That was how many had passed since the last visit of the Thosars to the poor Flonderans huddling in their caves, panicked to insanity by the giants descending from the sky. Panicking, scattering. . The Thosars would not have pursued them, naturally. They were far too civilized to give chase, to intrude where they were not welcomed. They would have departed, hoping for a more advanced civilization on their next visit. Probably they were quite bewildered by the swift departure of the ships encountered in space during the past two years, but again, they would not have given chase. It was not their way. They would hope to contact the government. .

Staeen closed off the outer parts of himself until there was only a spark of intelligence left, and eyes to see with, and he drifted in space, now and again shuddering from an impact with a grainlike bit of space debris. Eventually the eyes were covered with the detritus of space and there was only the spark of intelligence. It amused him to think that one day, a million years, or a thousand million years in the future, he might be in the heart of a planet. There were no regrets in the thought. He had lived many thousands of years. This was one more great adventure.

For long periods of time his mind dwelled on the fate of the eggs he had left in the scout. They would survive. Practically indestructible, they would lie dormant until conditions were right, then they would ripen and swell with life, and his seed would do what his people had not done: inhabit another galaxy.

He let his mind go out to the Flonderans and their crowded world where the Thosars probably already had landed. Eventually the Thosars would relate the incident to the Chlaesans, and eventually they would arrive at the answer to the question. Eventually they would decondition the Flonderans, if there were any remaining by then.

Staras eku Flonderans, he thought. Poor, short-lived Earthmen.

RICHARD McKENNA spent more than twenty years in a life he hated, that of an enlisted man in the U. S. Navy. He looked like the Hollywood stereotype of a tough Irish machinist’s mate, but he was the most gentle man who ever walked the earth. Somehow he had escaped growing the callouses on his mind and heart that most people acquire in becoming adult. When he died in 1964, he left behind an unfinished novel that might have been better than The Sand Pebbles, and half a dozen unpublished short stories, including this one.

THE SECRET PLACE

By Richard McKenna

This morning my son asked me what I did in the war. He’s fifteen and I don’t know why he never asked me before. I don’t know why I never anticipated the question.

He was just leaving for camp, and I was able to put him off by saying I did government work. He’ll be two weeks at camp. As long as the counselors keep pressure on him, he’ll do well enough at group activities. The moment they relax it, he’ll be off studying an ant colony or reading one of his books. He’s on astronomy now. The moment he comes home, he’ll ask me again just what I did in the war, and I’ll have to tell him.

But I don’t understand just what I did in the war. Some-times I think my group fought a death fight with a local myth and only Colonel Lewis realized it. I don’t know who won. All I know is that war demands of some men risks more obscure and ignoble than death in battle. I know it did of me..

It began in 1931, when a local boy was found dead in the desert near Barker, Oregon. He had with him a sack of gold ore and one thumb-sized crystal of uranium oxide. The crystal ended as a curiosity in a Salt Lake City assay office until, in 1942, it became of strangely great importance. Army agents traced its probable origin to a hundred-square-mile area near Barker. Dr. Lewis was called to duty as a reserve colonel and ordered to find the vein. But the whole area was overlain by thousands of feet of Miocene lava flows and of course it was geological insanity to look there for a pegmatite vein. The area had no drainage pattern and had never been glaciated. Dr. Lewis protested that the crystal could have gotten there only by prior human agency.

It did him no good. He was told he’s not to reason why. People very high up would not be placated until much money and scientific effort had been spent in a search. The army sent him young geology graduates, including me, and demanded progress reports. For the sake of morale, in a kind of frustrated desperation, Dr. Lewis decided to make the project a model textbook exercise in mapping the number and thickness of the basalt beds over the search area all the way down to the prevolcanic Miocene surface. That would at least be a useful addition to Columbia Plateau lithology. It would also be proof positive that no uranium ore existed there, so it was not really cheating.

That Oregon countryside was a dreary place. The search area was flat, featureless country with black lava outcropping everywhere through scanty gray soil in which sagebrush grew hardly knee high. It was hot and dry in summer and dismal with thin snow in winter. Winds howled across it at all seasons. Barker was about a hundred wooden houses on dusty streets, and some hay farms along a canal. All the young people were away at war or war jobs, and the old people seemed to resent us. There were twenty of us, apart from the contract drill crews who lived in their own trailer camps, and we were gown against town, in a way We slept and ate at Colthorpe House, a block down the street from our head-quarters. We had our own “gown” table there, and we might as veil have been men from Mars.

I enjoyed it, just the same. Dr. Lewis treated us like students, with lectures and quizzes and frightened reading. He was a fine teacher and a brilliant scientist, and we loved him.

He gave us all a turn at each phase of the work. I started on surface mapping and then worked with the drill crews, who were taking cores through the basalt and into the granite thousands of feet beneath. Then I worked on taking gravimetric and seismic readings. We had fine team spirit and we all knew we were getting priceless training in field geophysics. I decided privately that after the war I would take my doctorate in geophysics. Under Dr. Lewis, of course.

In early summer of 1944 the field phase ended. The contract drillers left. We packed tons of well logs and many boxes of gravimetric data sheets and seismic tapes for a move to Dr. Lewis’s Midwestern university. There we would get more months of valuable training while we worked our data into a set of structure contour maps. We were all excited and talked a lot about being with girls again and going to parties. Then the army said part of the staff had to continue the field search. For technical compliance, Dr. Lewis decided to leave one man, and he chose me.

It hit me hard. It was like being flunked out unfairly. I thought he was heartlessly brusque about it.

“Take a jeep run through the area with a Geiger once a day,” he said. “Then sit in the office and answer the phone.”

“What if the army calls when I’m away?” I asked sullenly.

“Hire a secretary,” he said. “You’ve an allowance for that.”

So off they went and left me, with the title of field chief and only myself to boss. I felt betrayed to the hostile town. I decided I hated Colonel Lewis and wished I could get revenge. A few days later old Dave Gentry told me how.

He was a lean, leathery old man with a white mustache and I sat next to him in my new place at the “town” table. Those were grim meals. I heard remarks about healthy young men skulking out of uniform and wasting tax money. One night I slammed my fork into my half-emptied plate and stood up.

“The army sent me here and the army keeps me here,” I told the dozen old men and women at the table. “I’d like to go overseas and cut Japanese throats for you kind hearts and gentle people, I really would! Why don’t you all write your Congressman?”

I stamped outside and stood at one end of the veranda, boiling. Old Dave followed me out.

“Hold your horses, son,” he said. “They hate the government, not you. But government’s like the weather, and you’re a man they can get aholt of.”

“With their teeth,” I said bitterly.

“They got reasons,” Dave said. “Lost mines ain’t supposed to be found the way you people are going at it. Besides that, the Crazy Kid mine belongs to us here in Barker.”

He was past seventy and he looked after horses in the local feedyard. He wore a shabby, open vest over faded suspenders and gray flannel shirts and nobody would ever have looked for wisdom in that old man. But it was there.

“This is big, new, lonesome country and it’s hard on people,” he said. “Every town’s got a story about a lost mine or a lost gold cache. Only kids go looking for it. It’s enough for most folks just to know it’s there. It helps ‘em to stand the country.”

“I see,” I said. Something stirred in the back of my mind.

“Barker never got its lost mine until thirteen years ago,”

Dave said. “Folks just naturally can’t stand to see you people find it this way, by main force and so soon after.”

“We know there isn’t any mine,” I said. “We’re just proving it isn’t there.”

“If you could prove that, it’d be worse yet,” he said. “Only you can’t. We all saw and handled that ore. It was quartz, just rotten with gold in wires and flakes. The boy went on foot from his house to get it. The lode’s got to be right close by out there.”

He waved toward our search area. The air above it was luminous with twilight and I felt a curious surge of interest. Colonel Lewis had always discouraged us from speculating on that story. If one of us brought it up, I was usually the one who led the hooting and we all suggested he go over the search area with a dowsing rod. It was an article of faith with us that the vein did not exist. But now I was all alone and my own field boss.

We each put up one foot on the veranda rail and rested our arms on our knees. Dave bit off a chew of tobacco and told me about Owen Price.

“He was always a crazy kid and I guess he read every book in town,”Dave said. “He had a curious heart, that boy.”

I’m no folklorist, but even I could see how myth elements were already creeping into the story. For one thing, Dave insisted the boy’s shirt was torn off and he had lacerations on his back.

“Like a cougar clawed him.” Dave said. “Only they ain’t never been cougars in that desert. We backtracked that boy till his trail crossed itself so many times it was no use, but we never found one cougar track.”

I could discount that stuff, of course, but still the story gripped me. Maybe it was Dave’s slow, sure voice; perhaps the queer twilight; possibly my own wounded pride. I thought of how great lava upwellings sometimes tear loose and carry along huge masses of the country rock. Maybe such an erratic mass lay out there, perhaps only a few hundred feet across and so missed by our drill cores, but rotten with uranium. If I could find it, I would make a fool of Colonel Lewis. I would discredit the whole science of geology. I, Duard Campbell, the despised and rejected one, could do that. The front of my mind shouted that it was nonsense, but something far back in my mind began composing a devastating letter to Colonel Lewis and comfort flowed into me.

“There’s some say the boy’s youngest sister could tell where he found it, if she wanted,” Dave said. “She used to go into that desert with him a lot. She took on pretty wild when it happened and then was struck dumb, but I hear she talks again now.” He shook his head. “Poor little Helen. She promised to be a pretty girl.”

“Where does she live?” I asked.

“With her mother in Salem,” Dave said. “She went to business school and I hear she works for a lawyer there.”

Mrs. Price was a flinty old woman who seemed to control her daughter absolutely. She agreed Helen would be my secretary as soon as I told her the salary. I got Helen’s security clearance with one phone call; she had already been investigated as part of tracing that uranium crystal. Mrs. Price arranged for Helen to stay with a family she knew in Barker, to protect her reputation. It was in no danger. I meant to make love to her, if I had to, to charm her out of her secret, if she had one, but I would not harm her. I knew perfectly well that I was only playing a game called “The Revenge of Duard Campbell.” I knew I would not find any uranium.

Helen was a plain little girl and she was made of frightened ice. She wore low-heeled shoes and cotton stockings and plain dresses with white cuffs and collars. Her one good feature was her flawless fair skin against which her peaked, black Welsh eyebrows and smoky blue eyes gave her an elfin look at times.

She liked to sit neatly tucked into herself, feet together, elbows in, eyes cast down, voice hardly audible, as smoothly self-contained as an egg. The desk I gave her faced mine and she sat like that across from me and did the busy work I gave her and I could not get through to her at all.

I tried joking and I tried polite little gifts and attentions, and I tried being sad and needing sympathy. She listened and worked and stayed as far away as the moon. It was only after two weeks and by pure accident that I found the key to her.

I was trying the sympathy gambit. I said it was not so bad, being exiled from friends and family, but what I could not stand was the dreary sameness of that search area. Every spot was like every other spot and there was no single, recognizable place in the whole expanse. It sparked something in her and she roused up at me.

“It’s full of just wonderful places,” she said.

“Come out with me in the jeep and show me one,” I challenged.

She was reluctant, but I hustled her along regardless. I guided the jeep between outcrops, jouncing and lurching. I had our map photographed on my mind and I knew where we were every minute, but only by map coordinates. “The desert had our marks on it: well sites, seismic blast holes, wooden stakes, cans, bottles and papers blowing in that everlasting wind, and it was all dismally the same anyway.

“Tell me when we pass a ‘place’ and I’ll stop,” I said.

“It’s all places,” she said. “Right here’s a place.”

I stopped the jeep and looked at her in surprise. Her voice was strong and throaty. She opened her eyes wide and smiled; I had never seen her look like that.

“What’s special, that makes it a place?” I asked.

She did not answer. She got out and walked a few steps.

Her whole posture was changed. She almost danced along. I followed and touched her shoulder.

“Tell me what’s special,” I said.

She faced around and stared right past me. She had a new grace and vitality and she was a very pretty girl.

“It’s where all the dogs are,” she said.

“Dogs?”

I looked around at the scrubby sagebrush and thin soil and ugly black rock and back at Helen. Something was wrong.

“Big, stupid dogs that go in herds and eat grass,” she said. She kept turning and gazing. “Big cats chase the dogs and eat them. The dogs scream and scream. Can’t you hear them?” “That’s crazy!” I said. “What’s the matter with you?”. I might as well have slugged her. She crumpled instantly back into herself and I could hardly hear her answer.

“I’m sorry. My brother and I used to play out fairy tales here. All this was a kind of fairyland to us.” Tears formed in her eyes. “I haven’t been here since.. I forgot myself. I’m sorry.”

I had to swear I needed to dictate “field notes” to force Helen into that desert again. She sat stiffly with pad and pencil in the jeep while I put on my act with the Geiger and rattled off jargon. Her lips were pale and compressed and I could see her fighting against the spell the desert had for her, and I could see her slowly losing.

She finally broke down into that strange mood and I took good care not to break it. It was weird but wonderful, and I got a lot of data. I made her go out for “field notes” every morning and each time it was easier to break her down. Back in the office she always froze again and I marveled at how two such different persons could inhabit the same body. I called her two phases “Office Helen” and “Desert Helen.”

I often talked with old Dave on the veranda after dinner.

One night he cautioned me.

“Folks here think Helen ain’t been right in the head since her brother died,” he said. “They’re worrying about you and her.”

“I feel like a big brother to her,” I said. “I’d never hurt her, Dave. If we find the lode, I’ll stake the best claim for her.”

He shook his head. I wished I could explain to him how it was only a harmless game I was playing and no one would ever find gold out there. Yet, as a game, it fascinated me.

Desert Helen charmed me when, helplessly, she had to uncover her secret life. She was a little girl in a woman’s body. Her voice became strong and breathless with excitement and she touched me with the same wonder that turned her own face vivid and elfin. She ran laughing through the black rocks and scrubby sagebrush and momentarily she made them beautiful. She would pull me along by the hand and some-times we ran as much as a mile away from the jeep. She treated me as if I were a blind or foolish child.

“No, no, Duard, that’s a cliff!” she would say, pulling me back.

She would go first, so I could find the stepping stones across streams. I played up. She pointed out woods and streams and cliffs and castles. There were shaggy horses with claws, golden birds, camels, witches, elephants and many other creatures. I pretended to see them all, and it made her trust me. She talked and acted out the fairy tales she had once played with Owen. Sometimes he was enchanted and some-times she, and the one had to dare the evil magic of a witch or giant to rescue the other. Sometimes I was Duard and other times I almost thought I was Owen.

Helen and I crept into sleeping castles, and we hid with pounding hearts while the giant grumbled in search of us and we fled, hand in hand, before his wrath.

Well, I had her now. I played Helen’s game, but I never lost sight of my own. Every night I sketched in on my map whatever I had learned that day of the fairyland topography. Its geomorphology was remarkably consistent.

When we played, I often hinted about the giant’s treasure. Helen never denied it existed, but she seemed troubled and evasive about it. She would put her finger to her lips and look at me with solemn, round eyes.

“You only take the things nobody cares about,” she would say. “If you take the gold or jewels, it brings you terrible bad luck.”

“I got a charm against bad luck and I’ll let you have it too,” I said once. “It’s the biggest, strongest charm in the whole world.”

“No. It all turns into trash. It turns into goat beans and dead snakes and things,” she said crossly. “Owen told me. It’s a rule, in fairyland.”

Another time we talked about it as we sat in a gloomy ravine near a waterfall. We had to keep our voices low or we would wake up the giant. The waterfall was really the giant snoring and it was also the wind that blew forever across that desert.

“Doesn’t Owen ever take anything?” I asked.

I had learned by then that I must always speak of Owen in the present tense.

“Sometimes he has to,” she said. “Once right here the witch had me enchanted into an ugly toad. Owen put a flower on my head and that made me be Helen again.”

“A really truly flower? That you could take home with you?”

“A red and yellow flower bigger than my two hands,” she said. “I tried to take it home, but all the petals came off.”

“Does Owen ever take anything home?”

“Rocks, sometimes,” she said. “We keep them in a secret nest in the shed. We think they might be magic eggs.”

I stood up. “Come and show me.”

She shook her head vigorously and drew back. “I don’t want to go home,” she said. “Not ever.”

She squirmed and pouted, but I pulled her to her feet.

“Please, Helen, for me,” I said. “Just for one little minute.”

I pulled her back to the jeep and we drove to the old Price place. I had never seen her look at it when we passed it and she did not look now. She was freezing fast back into Office Helen. But she led me around the sagging old house with its broken windows and into a tumbledown shed. She scratched away some straw in one corner, and there were the rocks. I did not realize how excited I was until disappointment hit me like a blow in the stomach.

They were worthless waterworn pebbles of quartz and rosy granite. The only thing special about them was that they could never have originated on that basalt desert.

After a few weeks we dropped the pretense of field notes and simply went into the desert to play. I had Helen’s fairyland almost completely mapped. It seemed to be a recent fault block mountain with a river parallel to its base and a gently sloping plain across the river. The scarp face was wooded and cut by deep ravines and it had castles perched on its truncated spurs. I kept checking Helen on it and never found her inconsistent. Several times when she was in doubt I was able to tell her where she was, and that let me even more deeply into her secret life. One morning I discovered just how deeply.

She was sitting on a log in the forest and plaiting a little basket out of fern fronds. I stood beside her. She looked up at me and smiled.

“What shall we play today, Owen?” she asked.

I had not expected that, and I was proud of how quickly I rose to it. I capered and bounded away and then back to her and crouched at her feet.

“Little sister, little sister. I’m enchanted,” I said. “Only you in all the world can uncharm me.”

“I’ll uncharm you,” she said, in that little girl voice. “What are you, brother?”

“A big, black dog,” I said. “A wicked giant named Lewis Rawbones keeps me chained up behind his castle.while he takes all the other dogs out hunting.”

She smoothed her gray skirt over her knees. Her mouth drooped.

“You’re lonesome and you howl all day and you howl all night,” she said. “Poor doggie.”

I threw back my head and howled.

“He’s a terrible, wicked giant and he’s got all kinds of terrible magic,” I said. “You mustn’t be afraid, little sister. As soon as you uncharm me I’ll be a handsome prince and I’ll cut off his head.”

“I’m not afraid.” Her eyes sparkled. “I’m not afraid of fire or snakes or pins or needles or anything.”

“I’ll take you away to my kingdom and we’ll live happily ever afterward. You’ll be the most beautiful queen in the world and everybody will love you.”

I wagged my tail and laid my head on her knees. She stroked my silky head and pulled my long black ears.

“Everybody will love me,” She was very serious now. “Will magic water uncharm you, poor old doggie?”

“You have to touch my forehead with a piece of the giant’s treasure,” I said. “That’s the only onliest way to uncharm me.”

I felt her shrink away from me. She stood up, her face suddenly crumpled with grief and anger.

“You’re not Owen, you’re just a man! Owen’s enchanted and I’m enchanted too and nobody will ever uncharm us!”

She ran away from me and she was already Office Helen by the time she reached the jeep.

After that day she refused flatly to go into the desert with me. It looked as if my game was played out. But I gambled that Desert Helen could still hear me, underneath somewhere, and I tried a new strategy. The office was an upstairs room over the old dance hall and, I suppose, in frontier days skirmishing had gone on there between men and women. I doubt anything went on as strange as my new game with Helen.

I always had paced and talked while Helen worked. Now I began mixing common-sense talk with fairyland talk and I kept coming back to the wicked giant, Lewis Rawbones. Office Helen tried not to pay attention, but now and then I caught Desert Helen peeping at me out of her eyes. I spoke of my blighted career as a geologist and how it would be restored to me if I found the lode. I mu’sed on how I would live and work in exotic places and how I would need a wife to keep house for me and help with my paper work. It disturbed Office Helen. She made typing mistakes and dropped things. I kept it up for days, trying for just the right mixture of fact and fantasy, and it was hard on Office Helen.

One night old Dave warned me again.

“Helen’s looking peaked, and there’s talk around. Miz Fowler says Helen don’t sleep and she cries at night and she won’t tell Miz Fowler what’s wrong. You don’t happen to know what’s bothering her, do you?”

“I only talk business stuff to her,” I said. “Maybe she’s homesick. I’ll ask her if she wants a vacation.” I did not like the way Dave looked at me. “I haven’t hurt her. I don’t mean her any harm, Dave,” I said.

“People get killed for what they do, not for what they mean,” he said. “Son, there’s men in this here town would kill you quick as a coyote, if you hurt Helen Price.”

I worked on Helen all the next day and in the afternoon I hit just the right note and I broke her defenses. I was not prepared for the way it worked out. I had just said, “All life is a kind of playing. If you think about it right, everything we do is a game.” She poised her pencil and looked straight at me, as she had never done in that office, and I felt my heart speed up.

“You taught me how to play, Helen. I was so serious that I didn’t know how to play.”

“Owen taught me to play. He had magic. My sisters couldn’t play anything but dolls and rich husbands and I hated them.”

Her eyes opened wide and her lips trembled and she was almost Desert Helen right there in the office

“There’s magic and enchantment in regular life, if you look at it right,”I said. “Don’t you think so, Helen?”

“I know it!” she said. She turned pale and dropped her pencil. “Owen was enchanted into having a wife and three daughters and he was just a boy. But he was the only man we had and all of them but me hated him because we were so poor.” She began to tremble and her voice went flat. “He couldn’t stand it. He took the treasure and it killed him..”Tears ran down her cheeks. “I tried to think he was only enchanted into play-dead and if I didn’t speak or laugh for seven years, I’d uncharm him.”

She dropped her head on her hands. I was alarmed. I came over and put my hand on her shoulder.

“I did speak.” Her shoulders heaved with sobs. “They made me speak, and now Owen won’t ever come back.”

I bent and put my arm across her shoulders.

“Don’t cry, Helen. He’ll come back,” I said. “There are other magics to bring him back.”

I hardly knew what I was saying. I was afraid of what I had done, and I wanted to comfort her. She jumped up and threw off my arm.

“I can’t stand it! I’m going home!”

She ran out into the hall and down the stairs and from the window I saw her run down the street, still crying. All of a sudden my game seemed cruel and stupid to me and right that moment I stopped it. I tore up my map of fairyland and my letters to Colonel Lewis and I wondered how in the world I could ever have done all that.

After dinner that night old Dave motioned me out to one end of the veranda. His face looked carved out of wood.

“I don’t know what happened in your office today, and for your sake I better not find out. But you send Helen back to her mother on the morning stage, you hear me?”

“All right, if she wants to go,” I said. “I can’t just fire her.”

“I’m speaking for the boys. You better put her on that morning stage, or we’ll be around to talk to you.”

“All right, I will, Dave.”

I wanted to tell him how the game was stopped now and how I wanted a chance to make things up with Helen, but I thought I had better not. Dave’s voice was flat and savage with contempt and, old as he was, he frightened me.

Helen did not come to work in the morning. At nine o’clock I went out myself for the mail. I brought a large mailing tube and some letters back to the office. The first letter I opened was from Dr. Lewis, and almost like magic it solved all my problems.

On the basis of his preliminary structure contour maps Dr.

Lewis had gotten permission to close out the field phase. Copies of the maps were in the mailing tube, for my information. I was to hold an inventory and be ready to turn everything over to an army quartermaster team coming in a few days. There was still a great mass of data to be worked up in refining the maps. I was to join the group again and I would have a chance at the lab work after all.

I felt- pretty good. I paced and whistled and snapped my fingers. I wished Helen would come, to help on the inventory. Then I opened the tube and looked idly at the maps. There were a lot of them, featureless bed after bed of basalt, like layers of a cake ten miles across. But when I came to the bottom map, of the prevolcanic Miocene landscape, the hair on my neck stood up.

I had made that map myself. It was Helen’s fairyland. The topography was point by point the same.

I clenched my fists and stopped breathing. Then it hit me a second time, and the skin crawled up my back.

The game was real. I couldn’t end it. All the time the game had been playing me. It was still playing me.

I ran out and down the street and overtook old Dave hurrying toward the feedyard. He had a holstered gun on each hip.

“Dave, I’ve got to find Helen,” I said.

“Somebody seen her hiking into the desert just at daylight,” he said. “I’m on my way for a horse.” He did not slow his stride. “You better get out there in your stinkwagon. If you don’t find her before we do, you better just keep on going, son.”

I ran back and got the jeep and roared it out across the scrubby sagebrush. I hit rocks and I do not know why I did not break something. I knew where to go and feared what I would find there. I knew I loved Helen Price more than my own life and I knew I had driven her to her death.

I saw her far off, running and dodging, I headed the jeep to intercept her and I shouted, but she neither saw me nor heard me. I stopped and jumped out and ran after her and the world darkened. Helen was all I could see, and I could not catch up with her.

“Wait for me, little sister!” I screamed after her. “I love you, Helen! Wait for me!”

She stopped and crouched and I almost ran over her. I knelt and put my arms around her and then it was on us.

They say in an earthquake, when the direction of up and down tilts and wobbles, people feel a fear that drives them mad if they can not forget it afterward. This was worse. Up and down and here and there and now and.then all rushed together. The wind roared through the rock beneath us and the air thickened crushingly above our heads. I know we clung to each other, and we were there for each other while nothing else was and that is all I know, until we were in the jeep and I was guiding it back toward town as headlong as I had come.

Then the world had shape again under a bright sun. I saw a knot of horsemen on the horizon. They were heading for where Owen had been found. That boy had run a long way, alone and hurt and burdened.

I got Helen up to the office. She sat at her desk with her head down on her hands and she quivered violently. I kept my arm around her.

“It was only a storm inside our two heads, Helen,” I said, over and over. “Something black blew away out of us. The game is finished and we’re free and I love you.”

Over and over I said that, for my sake as well as hers. I meant and believed it. I said she was my wife and we would marry and go a thousand miles away from that desert to raise our children. She quieted to a trembling, but she would not speak. Then I heard hoofbeats and the creak of leather in the street below and then I heard slow footsteps on the stairs.

Old Dave stood in the doorway. His two guns looked as natural on him as hands and feet. He looked at Helen, bowed over the desk, and then at me, standing beside her.

“Come on down, son. The boys want to talk to you,” he said.

I followed him into the hall and stopped.

“She isn’t hurt,” I said. “The lode is really out there, Dave, but nobody is ever going to find it.”

“Tell that to the boys.”

“We’re closing out the project in a few more days,” I said.

“I’m going to marry Helen and take her away with me.”

“Come down or we’ll drag you down!” he said harshly.

“We’ll send Helen back to her mother.”

I was afraid. I did not know what to do, “No, you won’t send me back to my mother!”

It was Helen beside me in the hall. She was Desert Helen, but grown up and wonderful. She was pale, pretty, aware and sure of herself.

“I’m going with Duard,” she said. “Nobody in the world is ever going to send me around like a package again.”

Dave rubbed his jaw and squinted his eyes at her.

“I love her, Dave,” I said. “I’ll take care of her all my life.”

I put my left arm around her and she nestled against me.

The tautness went out of old Dave and he smiled. He kept his eyes on Helen.

“Little Helen Price,” he said, wonderingly. “Who ever would’ve thought it?” He reached out and shook us both gently. “Bless you youngsters,” he said, and blinked his eyes. “I’ll tell the boys it’s all right.”

He turned and went slowly down the stairs. Helen and I looked at each other, and I think she saw a new face too.

That was sixteen years ago. I am a professor myself now, graying a bit at the temples. I am as positivistic a scientist as you will find anywhere in the Mississippi drainage basin. When I tell a seminar student “That assertion is operationally meaningless,” I can make it sound downright obscene. The students blush and hate me, but it is for their own good. Science is the only safe game, and it’s safe only if it is kept pure. I work hard at that, I have yet to meet the student I can not handle.

My son is another matter. We named him Owen Lewis, and he has Helen’s eyes and hair and complexion. He learned to read on the modern sane and sterile children’s books. We haven’t a fairy tale in the house, but I have a science library. And Owen makes fairy tales out of science. He is taking the measure of space and time now, with Jeans and Eddington. He cannot possibly understand a tenth of what he reads, ill the way I understand it. But he understands all of it in some other way privately his own.

Not long ago he said to me, “You know, Dad, it isn’t only space that’s expanding. Time’s expanding too, and that’s what makes us keep getting farther away from when we used to be.”

And I have to tell him just what I did in the war. I know I found manhood and a wife. The how and why of it I think and hope I am incapable of fully understanding. But Owen has, through Helen, that strangely curious heart. I’m afraid. I’m afraid he will understand.

JAMES BLISH has more scars and dignity than he had twenty years ago, but inside he is still the same irreverent, alertly interested, hungry young man. This story is crammed with his voracious interests, from microbiology to poetry; the cramming makes it all hang together as one gorgeous, multicolored, fluttering rag.

HOW BEAUTIFUL WITH BANNERS

By James Blish

1

Feeling as naked as a peppermint soldier in her transparent film wrap, Dr. Ulla Hillstrøm watched a flying cloak swirl away toward the black horizon with a certain consequent irony. Although nearly transparent itself in the distant dim arc-light flame that was Titan’s sun, the fluttering creature looked warmer than what she was wearing, for all that reason said it was at the same minus 316° F. as the thin methane it flew in. Despite the virus space-bubble’s warranted and eerie efficiency, she found its vigilance — itself probably as nearly alive as the flying cloak was — rather difficult to believe in, let alone to trust.

The machine — as Ulla much preferred to think of it — was inarguably an improvement on the old-fashioned pressure suit. Made (or more accurately, cultured) of a single colossal protein molecule, the vanishingly thin sheet of life-stuff processed gases, maintained pressure, monitored radiation through almost the whole of the electromagnetic spectrum, and above all did not get in the way. Also, it could not be cut, punctured or indeed sustain any damage short of total destruction; macroscopically it was a single, primary unit, with all the physical integrity of a crystal of salt or steel.

If it did not actually think, Ulla was grateful; often it almost seemed to, which was sufficient. Its primary drawback for her was that much of the time it did not really seem to be there.

Still, it seemed to be functioning; otherwise Ulla would in fact have been as solid as a stick of candy, toppled forever across the confectionery whiteness that frosted the knife-edged stones of this cruel moon, layer upon, layer. Outside — only a perilous few inches from the lightly clothed warmth of her skin — the brief gust the cloak had been soaring on died, leaving behind a silence so cataleptic that she could hear the snow creaking in a mockery of motion. Impossible though it was to comprehend, it was getting still colder out there. Titan was swinging out across Saturn’s orbit toward eclipse, and the apparently fixed sun was secretly going down, its descent sensed by the snows no matter what her Earthly sight, accustomed to the nervousness of living skies, tried to tell her. In another two Earth days it would be gone, for an eternal week.

At the thought, Ulla turned to look back the way she had come that morning. The virus bubble flowed smoothly with the motion and the stars became brighter as it compensated for the fact that the sun was now at her back. She still could not see the base camp, of course. She had strayed too far for that, and in any event, except for a few wiry palps, it was wholly underground.

Now there was no sound but the creaking of the methane snow, and nothing to see but a blunt, faint spearhead of hazy light, deceptively like an Earthly aurora or the corona of the sun, pushing its way from below the edge of the cold into the indifferent company of the stars. Saturn’s rings were rising, very slightly awaver in the dark blue air, like the banners of a spectral army. The idiot face of the gas giant planet itself, faintly striped with meaningless storms, would be glaring down at her before she could get home if she did not get herself in motion soon. Obscurely disturbed, Dr. ‘Hillstrøm faced front and began to unload her sled.

The touch and clink of the sampling gear cheered her, a little, even in this ultimate loneliness. She was efficient — many years, and a good many suppressed impulses, had seen to that; it was too late for temblors, especially so far out from the sun that had warmed her Stockholm streets and her silly friendships. All those null adventures were gone now like a sickness. The phantom embrace of the virus suit was perhaps less satisfying — only perhaps — but it was much more reliable. Much more reliable; she could depend on that.

Then, as she bent to thrust the spike of a thermocouple into the wedding-cake soil, the second flying cloak (or was it the same one?) hit her in the small of the back and tumbled her into nightmare.

2

With the sudden darkness there came a profound, ambiguous emotional blow — ambiguous, yet with something shockingly familiar about it. Instantly exhausted, she felt herself go flaccid and unstrung, and her mind, adrift in nowhere, blurred and spun downward too into trance.

The long fall slowed just short of unconsciousness, lodged precariously upon a shelf of dream, a mental buttress founded four years in the past — a long distance, when one recalls that in a four-dimensional plenum every second of time is 186,000 miles of space. The memory was curiously inconsequential to have arrested her, let alone supported her: not of her home, of her few triumphs or even of her aborted marriage, but of a sordid little encounter with a reporter that she had talked herself into at the Madrid genetics conference, when she herself was already an associate professor, a Swedish government delegate, a 25-year-old divorcee, and altogether a woman who should have known better.

But better than what? The life of science even in those days had been almost by definition the life of the eternal campus exile. There was so much to learn — or, at least, to show competence in — that people who wanted to be involved in the ordinary, vivid concerns of human beings could not stay with it long, indeed often could not even be recruited. They turned aside from the prospect with a shudder or even a snort of scorn. To prepare for the sciences had become a career in indefinitely protracted adolescence, from which one awakened fitfully to find one’s adult self in the body of a stranger. It had given her no pride, no self-love, no defenses of any sort; only a queer kind of virgin numbness, highly dependent upon familiar surroundings and unvalued habits, and easily breached by any normally confident siege in print, in person, anywhere — and remaining just as numb as before when the spasm of fashion, politics or romanticism had swept by and left her stranded, too easy a recruit to have been allowed into the center of things or even considered for it.

Curious, most curious that in her present remote terror she should find even a moment’s rest upon so wobbly a pivot. The Madrid incident had not been important; she had been through with it almost at once. Of course, as she had often told herself, she had never been promiscuous, and had often described the affair, defiantly, as that single (or at worst, second) test of the joys of impulse which any woman is entitled to have in her history. Nor had it really been that joyous. She could not now recall the boy’s face, and remembered how he had felt primarily because he had been in so casual and contemptuous a hurry.

But now that she came to dream of it, she saw with a bloodless, lightless eye that all her life, in this way and in that, she had been repeatedly seduced by the inconsequential. She had nothing else to remember even in this hour of her presumptive death. Acts have consequences, a thought told her, but not ours; we have done, but never felt. We are no more alone on Titan, you and I, than we have ever been. Basta, per carita! — so much for Ulla.

Awakening in the same darkness as before, Ulla felt the virus bubble snuggling closer to her blind skin, and recognized the shock that had so regressed her — a shock of recognition, but recognition of something she had never felt herself. Alone in a Titanic snowfield, she had eavesdropped on an…

No. Not possible. Sniffling, and still blind, she pushed the cozy bubble away from her breasts and tried to stand up. Light flushed briefly around her, as though the bubble had cleared just above her forehead and then clouded again. She was still alive, but everything else was utterly problematical. What had happened to her? She simply did not know.

Therefore, she thought, begin with ignorance. No one begins anywhere else. . but I did not know even that, once upon a time.

Hence:

3

Though the virus bubble ordinarily regulated itself, there was a control box on her hip — actually an ultra-short-range microwave transmitter — by which it could be modulated against more special environments than the bubble itself could cope with alone. She had never had to use it before, but she tried it now.

The fogged bubble cleared patchily, but it would not stay cleared. Crazy moirés and herringbone patterns swept over it, changing direction repeatedly, and, outside, the snowy landscape kept changing color like a delirium. She found, however, that by continuously working the frequency knob on her box — at random, for the responses seemed to bear no relation to the Braille calibrations on the dial — she could maintain outside vision of a sort in pulses of two or three seconds each.

This was enough to show her, finally, what had happened. There was a flying cloak around her. This in itself was unprecedented; the cloaks had never attacked a man before, or indeed paid any of them the least attention during their brief previous forays. On the other hand, this was the first time anyone had ventured more than five or ten minutes outdoors in a virus suit.

It occurred to her suddenly that insofar as anything was known about the nature of the cloaks, they were in some respect much like the bubbles. It was almost as though the one were a wild species of the other.

It was an alarming notion and possibly only a metaphor, containing as little truth as most poetry. Annoyingly, she found herself wondering if, once she got out of this mess, the men at the base camp would take to referring to it as “the cloak and suit business.”

The snowfield began to turn brighter; Saturn was rising. For a moment the drifts were a pale straw color, the normal hue of Saturn light through an atmosphere; then it turned a raving Kelly green. Muttering, Ulla twisted the potentiometer dial, and was rewarded with a brief flash of normal illumination which was promptly overridden by a torrent of crimson lake, as though she were seeing everything through a series of photographic color separations.

Since she could not help this, she clenched her teeth and ignored it. It was much more important to find out what the flying cloak had done to her bubble, if she were to have any hope of shucking the thing.