Black Hawk Down

Mark Bowden

BLACK HAWK DOWN

A Story of Modern War

CHAPTER 1

Hail Mary, Then Doom

STAFF SGT. Matt Eversmann’s lanky frame was fully extended on the rope for what seemed too long on the way down. Hanging from a hovering Blackhawk helicopter, Eversmann was a full 70 feet above the streets of Mogadishu. His goggles had broken, so his eyes chafed in the thick cloud of dust stirred up by the bird’s rotors.

It was such a long descent that the thick nylon rope burned right through the palms of his leather gloves. The rest of his Chalk, his squad, had already roped in. Nearing the street, through the swirling dust below his feet, Eversmann saw one of his men stretched out on his back at the bottom of the rope.

He felt a stab of despair. Somebody’s been shot already! He gripped the rope hard to keep from landing on top of the guy. It was Pvt. Todd Blackburn, at 18 the youngest Ranger in his Chalk, a kid just months out of a Florida high school. He was unconscious and bleeding from the nose and ears.

The raid was barely under way, and already something had gone wrong. It was just the first in a series of worsening mishaps that would endanger this daring mission. For Eversmann, a five-year veteran from Natural Bridge, Va., leading men into combat for the first time, it was the beginning of the longest day of his life.

Just 13 minutes before, three miles away at the Ranger’s base on the Mogadishu beach, Eversmann had said a Hail Mary at liftoff. He was curled into a seat between two helicopter crew chiefs, the knees of his long legs up around his shoulders. Before him, arrayed on both sides of the sleek UH-60 Blackhawk helicopter, was Eversmann’s Chalk, a dozen men in tan, desert camouflage fatigues. He had worried about the responsibility. Twelve men. He had prayed silently during Mass at the mess hall that morning. Now he added one more.

…Pray for us sinners, now, and at the hour of our death. Amen.

It was midafternoon, Oct. 3, 1993. Eversmann’s Chalk Four was part of a company of U.S. Rangers assisting a commando squadron that was about to descend on a gathering of Habr Gidr clan leaders in the heart of Mogadishu, Somalia. This ragtag clan, led by warlord Mohamed Farrah Aidid, had challenged the United States of America.

Today’s targets were two top Aidid lieutenants. Commandos, the nation’s elite commando unit, would storm the target house and capture them. Then four helicopter loads of Rangers, including Eversmann’s men, would rope down to all four corners of the target block and form a perimeter. No one would be allowed in or out.

Waiting for the code word to launch, which today was “Irene,” they were a formidable armada. The helicopter assault force included about 75 Rangers and 40 Commando troops in 17 helicopters. Idling at the airport was a convoy of 12 vehicles with soldiers who would ride three miles to the target building and escort the Somali prisoners and the assault team back to base.

The swell of the revving engines had made the earth tremble. The Rangers were eager for action. Bristling with grenades and ammo, gripping the well-oiled steel of their weapons, they felt their hearts race under their flak vests. They ran through last-minute mental checklists, saying prayers, triple-checking weapons, rehearsing their choreographed moves. They had left behind canteens, bayonets, night-vision devices (NODs)—anything they felt would be dead weight on a fast daylight raid.

It was 3:32 p.m. when the lead Blackhawk pilot, Chief Warrant Officer Michael Durant, announced:

“F-in’ Irene.”

And the swarm of black copters lifted up into an embracing blue vista of Indian Ocean and sky. They eased out across a littered strip of white sand and moved low and fast over the breakers.

Mogadishu spread beneath them in ruins. Five years of civil war had reduced the once-picturesque African port to a post-apocalyptic nightmare. The few paved avenues were crumbling and littered with mountains of trash and debris. Those walls and buildings that still stood in the heaps of gray rubble were pockmarked with bullet scars and cannon shot.

In his bird, code-named Super 67, Eversmann silently rehearsed the plan. When his Chalk Four touched the street, the boys would already be taking down the target house, arresting the Somalis inside. Then the Americans and their prisoners would board the ground convoy and roll back for a sunny Sunday afternoon on the beach.

It was the unit’s sixth mission since coming to Mogadishu in late August. Now Maj. Gen. William F. Garrison, their commander, was taking a calculated risk in sending them in daylight into the Bakara Market area, a hornet’s nest of Aidid supporters.

The commandos rode in on MH-6 Little Birds, choppers small enough to land in alleys or on rooftops. In the bigger Blackhawks, Rangers dangled their legs from the doorways. Others squatted on ammo cans or sat on flak-proof panels laid out on the floor. They all wore flak vests and helmets and 50 pounds of gear and ammo.

Stripped down, most Rangers looked like teenagers (their average age was 19). They were products of rigorous selection and training. They were fit and fast. With their buff bodies, distinct crew cuts—sides and back of the head shaved clean—and grunted Hooah greeting, the Rangers were among the most gung-ho soldiers in the Army.

Inside Super 67, Eversmann was anxious about being in charge. He’d won the distinction by default. His platoon sergeant had been summoned home by an illness in his family, and the guy who replaced him had suffered an epileptic seizure.

Now, as they approached the target site, he felt more confident. They had done this dozens of times.

By the time the Blackhawks had moved down over the city, the Little Birds with the Commando troops were almost over the target. The mission could still have been aborted. But the only threat spotted was burning tires on a nearby street. Somalis often burned tires to summon militia. These, it was determined, had been set earlier in the day.

“Two minutes,” came the voice of the Super 67 pilot in Eversmann’s earphones.

Two advance AH-6 Little Birds armed with rockets then made their “bump,” or initial pass over the target. It was 3:43 p.m.

Cameras on spy planes and orbiting helicopters relayed the scene back to commanders at the Joint Operations Center on the beach. They saw a busy Mogadishu neighborhood, in much better shape than most. The landmark was the Olympic Hotel, a five-story white building, one of the few large structures still intact in the city. Three blocks west was the teeming Bakara Market.

In front of the hotel ran Hawlwadig Road, a paved, north-south avenue crossed by narrow dirt alleys. At the intersections, drifting sand turned rust-orange in the afternoon sun.

One block up from the hotel, across Hawlwadig, was the target house. It was flat-roofed with three rear stories and two front stories. It was shaped like an L, with a small courtyard enclosed by a high stone wall. In front moved cars, people and donkey carts.

Conditioned to the noise of the copters by months of overflights, people below did not stir as two Little Birds made a first swift pass, looking for trouble. Seeing none, the four Commando Little Birds zoomed down to Hawlwadig Road, disappearing into swirling dust as the commandos leaped from their helicopters and stormed the house. Next came the Blackhawks with the Rangers.

Eversmann’s copter hovered just above the brown storm. Waiting for the three other Blackhawks, it seemed to the sergeant that they hung there for a dangerously long time. A still Blackhawk was a big target. Even over the sound of the rotor and engines the men could hear the pop of gunfire.

The 3-inch-thick nylon ropes were coiled before the doors. When they were finally pushed out, one dropped down on a car. This delayed things further. The pilot nudged his aircraft forward until the rope dragged free.

“We’re a little short of our desired position,” he told Eversmann. They were going in a block north of their assigned corner. Still, that wasn’t crucial. The sergeant thought it would be a lot safer on the ground.

“No problem,” he said.

“We’re about 100 meters short,” the pilot warned.

Eversmann gave him a thumbs-up. He would be the last man out.

When it was his time to jump, the strap on his goggles broke. Flustered, he tossed them and sprung for the rope, forgetting to take off his earphones. He jumped, ripping the earphone cord from the ceiling.

In the excitement, time slowed. All his movements became very deliberate. He hadn’t realized how high they were. The slide down on the rope was far longer than any they’d done in training. Then, on his way down, Eversmann spotted Todd Blackburn splayed out on the street at the end of the rope.

Eversmann’s feet touched down next to the fallen Ranger, and the crew chiefs in the copter released the rope. It fell twisting to the road. As the Blackhawk moved up and away, the noise eased and the dust settled. The city’s musky odor bore in.

Pvt. 2 Mark Good, Chalk Four’s medic, was already at work on Blackburn. The kid had one eye shut. Blood gurgled from his mouth. Good inserted a tube down Blackburn’s throat to help him breathe. Sgt. First Class Bart Bullock, a Commando medic, started an IV. Blackburn hadn’t been shot, he’d fallen. He’d somehow missed the rope and plummeted.

He was still alive, but unconscious. He looked pretty busted up. Eversmann stepped away. He took a quick count of his Chalk.

His men had peeled off as planned against the mud-stained stone walls on either side of the street. That left Eversmann in the middle of the road with Blackburn and the medics. It was hot, and sand was caked in his eyes, nose and ears. They were taking fire, but it wasn’t very accurate. Oddly, it hadn’t even registered with the sergeant. You would think bullets clipping past would command your attention, but he’d been too preoccupied.

Now he noticed. Passing bullets made a snapping sound, like cracking a stick of dry hickory. Eversmann had never been shot at before. As big a target as he made at 6-foot-4, he figured he’d better find cover. He and the two medics grabbed Blackburn under his arms, and, trying to keep his neck straight, dragged him to the edge of the street. They squatted behind two parked cars.

Good looked up at Eversmann. “He’s litter urgent, Sarge. We need to extract him right now or he’s going to die.”

Eversmann shouted to his radio operator, Pvt. Jason Moore, and asked him to raise Capt. Mike Steele on the company radio net. Steele, the Ranger commander, had roped in with two lieutenants and the rest of Chalk One to the block’s southeast corner.

Minutes passed. Moore shouted back to say he couldn’t get Steele.

“What do you mean you can’t get him?” Eversmann asked.

Neither man had noticed that a bullet had severed the wire leading to the antenna on Moore’s radio. Eversmann tried his walkie-talkie. Again Steele didn’t answer, but after several tries Steele’s lieutenant, Larry Perino, came on the line.

The sergeant made a particular effort to speak slowly and clearly. He explained that Blackburn had fallen and was badly injured. He needed to come out. Eversmann tried to convey urgency without alarm.

So when Perino said, “Calm down,” it really burned Eversmann. This is one hell of a time to start sharpshooting me.

Fire was getting heavier. To officers watching on screens in the command center, it was as if their men had poked a stick into a hornet’s nest. It was an amazing and unnerving thing to view a battle in real time. Cameras on the surveillance aircraft circling high over the fight captured crowds of Somalis erecting barricades and lighting tires to summon help. People were pouring into the streets, many with weapons. They were racing from all directions toward the spot where orbiting helicopters marked the fight. There wasn’t much the Joint Operating Command could do but watch.

Eversmann’s men had fanned out and were shooting in every direction except south toward the target building. He saw crowds of Somalis way up Hawlwadig to the north, and others, closer, darting in and out of alleys, taking shots at the Rangers. They were coming closer, wary of the Americans’ guns.

The Rangers had been issued strict rules of engagement. They were to shoot only at someone who pointed a weapon at them, but already this was getting unrealistic. Those with guns were intermingled with women and children. The Somalis were strange that way. Whenever there was a disturbance in Mogadishu, people would throng to the spot: men, women, children—even the aged and infirm. It was like some national imperative to bear witness. And over this summer, the Ranger missions had stirred up widespread hatred.

Things were not playing out according to the script in Eversmann’s head. His Chalk was still in the wrong place. He’d figured they could just hoof it down Hawlwadig, but Blackburn’s falling and the unexpected volume of gunfire had ruled that out.

Time played tricks. It would be hard to explain to someone who wasn’t there. Events seemed to happen twice normal speed, but from inside his personal space, the place where he thought and reacted and watched, every second seemed a minute long. He had no idea how much time had gone by. It was hard to believe things could have gone so much to hell in such a short time.

He kept checking back to see if the ground convoy had moved up. He knew it was probably too soon. It would mean that things were wrapping up. He must have looked a dozen times before he saw the first humvee—the wide-bodied vehicle that replaced the jeep as the Army’s all-purpose ground vehicle—round the corner three blocks down. What a relief! Maybe the boys are done and we can roll out of here.

He radioed Lt. Perino.

“Listen, we really need to move this guy or he’s going to die. Can’t you send somebody down the street?”

“No, the humvees, could not move to his position.“

“Good,” the medic, spoke up: “Listen, Sarge, we’ve got to get him out.”

Eversmann summoned two of Chalk Four’s sergeants, rock-solid Casey Joyce and 6-foot-5 Jeff McLaughlin. He addressed McLaughlin, shouting over the escalating noise of the fight.

“Sergeant, you need to move him down to those humvees, toward the target.”

They unfolded a compact litter, and with Joyce and McLaughlin in front and medics Good and Bullock in back, they took off down the street. They ran stooped. Bullock was still holding the IV bag connected to the kid’s arm. McLaughlin didn’t think Blackburn was going to make it. On the litter he was dead weight, still bleeding from the nose and mouth. They were all yelling at him, “Hang on! Hang on!” but, by the look of him, he had already let go.

They would run a few steps, put Blackburn down, shoot, then pick him up and carry him a few more steps, then put him down again.

“We’ve got to get those humvees to come to us,” Good said finally. “We keep picking him up and putting him down like this and we’re going to kill him.”

So Joyce volunteered to fetch a humvee. He took off running on his own.

* * *

AFTER THE HELICOPTER force had moved out over the beach, Staff Sgt. Jeff Struecker had waited several minutes in his humvee with the rest of the ground convoy at the base. His was the lead in a column of 12 vehicles. They were to drive to a point behind the Olympic Hotel and wait for the D-boys to wrap things up in the target house, which was just a five-minute drive from the base.

Struecker, a born-again Christian from Fort Dodge, Iowa, knew Mogadishu better than most guys at the compound. His platoon had driven out on water runs and other details daily. The stench was what hit him first. Garbage was strewn everywhere. People burned trash on the streets. They were always burning tires. They burned animal dung for fuel. That added to the mix.

In this African city people spent their days lounging outside their shabby rag huts and tin shacks. There were gold-toothed women in colorful robes and old men in loose, cotton skirts and worn, plastic sandals. When the Rangers searched the men, they would often find wads of the addictive khat plant they chewed to get high. When they grinned their teeth were stained black and orange. In some parts of town the men would shake their fists at the Rangers as they drove past.

It was hard to imagine what interest the United States of America had in such a place. But Struecker was just 24, a soldier, and it wasn’t his place to question such things. Today his job was to roll up in force on Hawlwadig Road, load up Somali prisoners, the Commando teams and the Rangers, and bring them back out.

He had three men in his vehicle: Spec. Derek Velasco, Spec. Tim Moynihan and a company favorite, Sgt. Dominick Pilla. Dom Pilla was a big, powerful kid from Vineland, N.J.—he had that Joy-zee accent—who used his hands a lot when he talked. Pilla was just born funny. He loved practical jokes. He had bought tiny charges that he stuck in guys’ cigarettes. They’d explode with a startling Pop! about halfway through a smoke. Most people who tried that kind of thing were annoying, but people laughed along with Pilla. His cutting impression of Capt. Steele was a highlight of the little skits the Rangers sometimes put on in the hangar.

Struecker and the rest of the column timed their departure so they wouldn’t arrive at the hotel before the assault on the target house had begun. Then they immediately got lost. Struecker, who was leading the convoy, took a wrong turn and watched with alarm as the rest of the vehicles drove in a different direction. He’d found his way back, but only after the rest of the vehicles had already moved up to the target house to load prisoners.

One of the humvees in the column held a group of Commando soldiers and Navy SEALs, that service’s elite commando unit. They raced on ahead of the convoy to join the assault force, which had found 24 Somalis in the house and were handcuffing them. As this humvee approached the house, SEAL John Gay heard a shot and felt a hard impact on his right hip. He cried out. Master Sgt. Tim “Grizz” Martin, a commando in Gay’s humvee, tore open Gay’s pants and examined his hip, then gave Gay good news. The round had hit smack on the SEAL’s knife. It had shattered the blade, but the knife had deflected the bullet. Martin pulled several bloody fragments of blade out of Gay’s hip, and bandaged it. Gay limped out, took cover, and began returning fire.

In the mounting gunfire, they were startled to see a Ranger running toward them down Hawlwadig Road. It was Casey Joyce. He quickly explained Blackburn’s condition, and pointed back to where the others were waiting. He jumped into the humvee, and they drove up a block to where the young private waited on the litter with Sgt. McLaughlin and the two medics.

They set Blackburn in the back of the SEAL humvee and got permission to take him back to the base immediately.

Struecker and his companion humvee had just found their way back to the main convoy and were ordered to escort the SEAL humvee. It had no big gun on top. Struecker’s had a 50-caliber machine gun, and his companion humvee had a Mark 19, which could rapidly fire big, grenade-like rounds. The three-vehicle column began racing back to base through streets now alive with gunfire and explosion.

This time Struecker knew which way to go. He had mapped a return route that was simple. Several blocks south of Hawlwadig was a main road that would take them all the way down to the beach, where they could turn right and drive straight into the base.

But things had worsened. Armed street fighters were sprinkled into the crowds of civilians. Roadblocks and barricades had been erected. The humvees drove around and through them, with Struecker in the front vehicle and Blackburn in the middle humvee. Good, the medic, was holding up the IV bag for him with one hand while firing his rifle with the other.

They started taking fire. A Ranger in Blackburn’s humvee shot down two Somali gunmen who ran right up to the rear of the vehicle as they moved past an alley. At every intersection came a hail of rounds. People were shooting from rooftops and from windows and from all directions.

Up in Struecker’s humvee, he instructed his M-60 gunner, Dom Pilla, to concentrate all his fire to the right, and to leave everything to the left to the 50-caliber. They didn’t want to drive too fast, because a violently bumpy ride couldn’t do Blackburn any good.

Pilla wheeled his gun toward a Somali standing on the street just a few feet away. They both fired at the same time, and both fell. A round tore into Pilla’s forehead and the exit wound blew blood and brain out the back of his skull. His body flopped over into the lap of Spec. Tim Moynihan, who cried out in horror.

“Pilla’s hit!” he screamed.

Just then, over the radio, came the voice of Sgt. First Class Bob Gallagher, leader of the vehicle platoon.

How things going?

Struecker ignored the radio, and shouted back over his shoulder at Moynihan.

“Calm down! What’s wrong with him?” Struecker couldn’t see all the way to the back hatch.

“He’s dead!” Moynihan shouted.

“How do you know he’s dead? Are you a medic?” Struecker asked.

Struecker turned for a quick look over his shoulder and saw that the whole rear of his vehicle was splattered red.

“He’s shot in the head! He’s dead!” Moynihan screamed.

“Just calm down,” Struecker pleaded. “We’ve got to keep fighting until we get back.”

To hell with driving carefully. Struecker told his driver to step on it, and he hoped the others would follow. They were close to National Street, a main east/west highway. Struecker saw rocket-propelled grenades flying across the street now. It seemed as if the whole city was shooting at them. They drove wildly now, shooting at both sides of the street.

Inside Struecker’s humvee, Sgt. Gallagher’s voice came across the radio again.

How’s it going?

“I don’t want to talk about it,” Struecker said into the radio.

Gallagher didn’t like that answer.

You got any casualties?

“Yeah. One.”

Struecker tried to leave it at that. So far nobody on their side had been killed, as far as he knew, and he didn’t want to be the one to put news like that on the air. Men in battle drink up information as if downing water; it becomes more important than water. Unlike most of these guys, Struecker had been to war before, in Panama and the Persian Gulf, and he knew soldiers fought a lot better when things were going their way. Once things turned, it was real hard to reassert control. People panic. It was happening to Moynihan and the other guys in his humvee right now. Panic was a virus.

Who is he and what’s his status? Gallagher demanded.

“It’s Pilla.”

What’s his status?

Struecker held the microphone for a moment, debating with himself, and then reluctantly answered:

“He’s dead!”

At the sound of that word, all radio traffic stopped. For many long seconds afterward, there was silence.

CHAPTER 2

Dazed, Blood-Spattered and Frantic

WITH BADLY INJURED Pfc. Todd Blackburn on board, the little convoy sped out of the treacherous side streets of Mogadishu to a wide road, and for a stretch the firing abated. As they approached the sea, well south of the target building, the road was mobbed with Somalis. In the lead humvee, Staff Sgt. Jeff Struecker’s heart sank. How was he going to get his three humvees back to base through all these people?

His driver slowed to a crawl and leaned on the horn. Struecker told him to keep moving. He threw out loud but harmless flash-bang grenades. Then he told his 50-gunner to open up over people’s heads.

The sound of the big gun scattered most of the people, and the column sped up again. They may have run over some people. Struecker didn’t look back to see.

About three miles north, near the Olympic Hotel, the commandos had 24 Somalian prisoners handcuffed and ready for loading on the main ground convoy. Among them were the primary targets of the raid, two Somalian clan leaders.

Struecker’s three-vehicle convoy had left to get emergency treatment for Blackburn, a young Ranger who had fallen out of a helicopter. On the way they’d been badly shot up. In the back of Struecker’s humvee, Sgt. Dominick Pilla had been shot dead.

Now they came up behind a slow-moving pickup truck with people hanging off the back. It would not pull over, so Struecker told his driver to ram it. A man with his leg hanging off the back screamed as the humvee hit. As the truck veered off the road, the man curled into the back bed, clutching his leg.

They passed through the gates of the beachfront American compound with a tremendous sense of relief and exhaustion. They had run the gauntlet. Dazed and blood-splattered, they piled out. Struecker had expected to find the calm safety of the home base. Instead, the scene was frantic. People were racing around on the tarmac. He heard a commander’s voice on the speaker box, shouting, “Pay attention to what’s going on and listen to my orders!”

It smelled like panic. Something had happened.

The medical people ran to the middle humvee to get Blackburn, who was on his way to a long and difficult recovery. They didn’t know about Pilla.

Struecker grabbed one as he went past.

“Look, there’s a dead in the back of my vehicle; you need to get him off.”

BACK IN THE CITY, at Staff Sgt. Matt Eversmann’s intersection, things continued to go wrong for Chalk Four. First Blackburn had fallen out of the helicopter. Then they had roped in well off target. And now they were pinned down on Hawlwadig Road, a block north of their proper position at the northwest corner of the target block.

Two of Eversmann’s men, Sgt. Scott Galentine and Sgt. Jim Telscher, were crouched behind cars across the street. For some reason, the steady gunfire didn’t frighten Galentine. It turned him giddy. He was goofing with Telscher, making faces and grinning, as rounds kicked up dirt between them, shattering the windows and blowing out the tires of the cars. Telscher was a sight. He had blood smeared on his face, having accidentally smacked himself with his rifle coming down the fast rope.

Galentine was a 21-year-old sergeant from Xenia, Ohio, who had gotten bored working at a rubber plant. Now he was pointing his M-16 at people down the street, aiming at center mass, and squeezing off rounds. People would drop, just like silhouettes at target practice.

When they started catching rounds from a different direction, Galentine and Telscher ran to an alley. There, Galentine came face to face with a Somalian woman. She was staring up at Galentine and trying to open a door. His first instinct had been to shoot. The woman’s eyes were wide with terror. It startled him, that moment. It cut through his silliness. This wasn’t a game. He had been very close to killing this woman. She got the door open and stepped inside.

Galentine took cover behind another car, his gun braced against his shoulder. He was picking targets out of the hundreds of Somalis moving toward them.

As he fired, he felt a painful slap on his left hand that knocked his weapon so hard it spun completely around him. His first thought was to right his gun, but when he reached out he saw that his left thumb was lying on his forearm, attached by a strip of skin.

He picked up his thumb and tried to press it back to his hand.

Telscher called to him. “You all right, Scotty? You all right?”

Sgt. Eversmann had seen it, the M-16 spinning and a splash of pink by Galentine’s left hand. He had seen Galentine reach for the thumb, then look across the road at him.

“Don’t come across!” Eversmann shouted. There was withering fire coming down the road. “Don’t come across!”

Galentine heard the sergeant but started running anyway. He seemed to be getting nowhere, as if in a dream. His feet seemed heavy and slow. He dived the last few feet.

The sergeant was still contending with the crowd. Men would dart out into the street and spray bursts from their AK-47s, then take cover. Eversmann saw the flash and puff of smoke of rocket-propelled grenades being launched their way. The grenades came wobbling through the air and exploded with a long splash of flame and a pounding concussion. The heat would wash over and leave the odor of powder.

At one point, such a great wave of fire from Somalis tore down the road that it created a shock wave of noise and energy that Eversmann could actually see coming. They had expected some resistance on this raid, but nothing like this.

When one of the big Blackhawks flew over, Eversmann stood and stretched his long arm to the north, directing them to the Somalian gunmen. He watched the crew chief in back, sitting behind his minigun, and then saw the gun spout lines of flame at targets up the street. For a few minutes, all shooting from that direction stopped.

To Eversmann’s left, Pvt. 2 Anton Berendsen was prone on the ground and firing his M203, a rifle with a grenade-launching tube under the barrel. Seconds after Galentine had dived in, Berendsen turned and grabbed his shoulder.

“Oh, my God, I’m hit,” Berendsen said. He looked up at Eversmann.

Berendsen scooted over against the wall next to Galentine with one arm limp at his side, picking small chunks of debris from his face.

Eversmann squatted next to both men, turning first to Berendsen, who was still preoccupied, looking down the alley.

“Ber, tell me where you’re hurt,” Eversmann said.

“I think I got one in the arm.”

With his good hand, Berendsen was fumbling with the breech of his grenade launcher. Eversmann impatiently reached down and opened it.

“There’s a guy right down there,” Berendsen said.

As Eversmann struggled to lift Berendsen’s vest and open his shirt to assess the wound, the private shot off a 203 round one-handed. The sergeant could see the fist-sized round spiraling toward a tin shack 40 meters away. When it hit, the shack vanished in a great flash of light and smoke.

Berendsen’s injury did not look severe. Eversmann turned to Galentine, who looked wide-eyed, as if he might be lapsing into shock. His left thumb was hanging down below his hand.

Eversmann grabbed the thumb and placed it in the dazed sergeant’s palm.

“Scott, hold this,” he said. “Just put your hand up and hold it, buddy.”

Galentine gripped the thumb with his fingers.

Sgt. First Class Glenn Harris came running up to tend the wound. When he saw Galentine’s thumb, he dropped the field dressing to the ground. Galentine reached into Harris’ kit with his good hand, removed a clean dressing, and handed it to him. His injured hand stung. It felt the way it did on a cold day when you hit a baseball wrong.

“Don’t worry, Sgt. Galentine, you’re going be OK,” Berendsen said.

With Berendsen hurt, Eversmann had only Spec. Dave Diemer covering the alley to the east with his SAW (squad automatic weapon). Diemer was a boisterous 22-year-old from Newburgh, N.Y., and the company’s arm-wrestling champ. Eversmann kneeled beside Diemer behind a car and fired his M-16. It occurred to Eversmann that this was the first shot he’d fired.

It was hectic. Eversmann tried to stay calm. This was his first time in charge. He had three Rangers injured, one critically, and he’d managed to get him out. Neither Galentine’s nor Berendsen’s wounds were life-threatening.

Glass shattered and showered on Eversmann and Diemer. A Somali had run out to the middle of Hawlwadig Road, just a few yards away, and opened up on the car. Diemer dived down behind the rear wheel on the passenger side and shot him with a quick burst. The Somali fell over backward in a rumpled heap.

Eversmann radioed to First Lt. Larry Perino, the Chalk One commander, that he had taken two more casualties.

From across the street, Sgt. Telscher shouted, “Sgt. Eversmann! Snodgrass has been shot!”

Spec. Kevin Snodgrass, the machine gunner, had been crouched behind a car hulk and a round had evidently skipped off the car or ricocheted up from the road. Eversmann saw Telscher stoop over Snodgrass to tend to the wound. The machine gunner was not screaming. It didn’t look too dire.

“Sarge?”

Eversmann turned wearily to Diemer.

“A helicopter just crashed.”

CHAPTER 3

A Terrifying Scene, Then a Big Crash

ABDIAZIZ ALI ADEN heard the American helicopters coming in low, so low that the big tree that stood in the central courtyard of his stone house was uprooted and knocked over. Aden was 18 but looked five years younger, a slip of a man with thick, bushy hair.

Aden rushed outside when the helicopters passed over. He heard shooting to the west, near Hawlwadig, the big road that passed before the Olympic Hotel three blocks west. Aden ran toward the noise. The sky was dark with smoke.

The air around Aden sizzled and cracked with gunfire. Above him were helicopters, some with lines of flame spitting from their guns. He ran two blocks with his head down until he saw several big American trucks and humvees, with machine guns mounted on them, shooting everywhere.

The Rangers wore body armor and helmets with goggles. Aden could see no part of them that looked human. They were like futuristic warriors from an American movie. People were running madly, hiding from them. There was a line of Somalian men in handcuffs being loaded onto big trucks. On the street were dead people and a dead donkey splayed out in front of its water cart.

The scene terrified Aden. As he ran back to his house, one of the Blackhawk helicopters flew over him at rooftop level. It made a rackety blast, and wash from its rotors swept over the dusty alley like a violent storm. Through this dust, Aden saw a Somalian militiaman carrying a rocket-propelled grenade launcher—an RPG—step into the alley and drop to one knee.

The militiaman waited until the copter had passed overhead. Then he leaned the RPG up and fired at the aircraft from behind. Aden saw a great flash from the back end of the launcher and then saw the grenade explode into the rear of the helicopter, cracking the tail.

The body of the aircraft started to spin, so close to Aden that he could see the pilot inside struggling at the controls. The pilot could not hold it, and the helicopter started to flip. It was tilted slightly toward Aden when it hit the roof of his house with a loud, crunching sound, and then slammed on its side into the alley with a great, scraping crash in a thick cloud of dust and rock and smoke.

The helicopter had destroyed part of Aden’s house; he feared his family had been killed. He ran to the crash and found his parents and eight brothers and sisters trapped under a big sheet of tin roof. They had stepped outside and were standing against the west wall when the helicopter hit and the roof came down on them. They were not badly hurt. Aden worked his way past the crashed helicopter, which had fallen to the alley sideways so that the bottom of it faced him. He helped pull the roof off his parents and brothers and sisters. Afraid that the helicopter would explode, they all ran across a wide, rutted dirt road to a friend’s house three doors up. There they waited.

There were no flames and no explosion. Soon Aden came back to guard his house. In Mogadishu, if you left your house open and undefended, it would quickly be looted.

Smoke had stopped rising from the helicopter when he returned. He ran into his house and stood in the courtyard by the uprooted tree and saw that the wall where the helicopter had crashed was gone; it was just a heap of stones and dusty mortar.

Then, standing inside his house, Aden saw a wounded American soldier climb out of the crumpled machine, and then another American with an M-16. Aden turned and ran back out a side door and hid behind an old white Volkswagen on the dirt street. He slipped down and crawled under it, curling himself up into a ball, trying to make himself small.

When the American with the gun rounded the corner he saw Aden under the car. Seeing that Aden had no weapon, the soldier moved on. But first he stopped alongside the car—Aden could have reached out and touched the soldier’s boots—and pointed his gun at a Somalian man armed with an M-16 across the street from the car.

The two men fired at the same time but neither fell. They went to shoot again but the Somali’s gun jammed and the American didn’t shoot. He ran closer, over to a wall across the road, then fired. The bullet made a hole in the Somali’s forehead, and he toppled. The American ran over and shot him three more times as he lay there.

Then a big Somalian woman came running from a narrow alley, right in front of the soldier. Startled, he quickly fired his weapon. The woman fell face forward, dropping like a sack, without putting out her arms to break the fall.

More Somalis came now, with guns, shooting at the American. He dropped to one knee and shot many of them, but the Somalis’ bullets also hit him.

Then a helicopter landed right on Freedom Road, the street in front of Aden’s house. It seemed impossible that a helicopter could fit in so narrow a street. It was a Little Bird, the Americans’ fast, tiny and highly maneuverable copter. Its rotor blades were just inches from the walls of Aden’s house and the house directly across the road. The roar of the helicopter was deafening, and dust swirled around. Aden couldn’t breathe. Then the shooting got worse.

One of the airmen was leaning out of the helicopter and aiming his gun up the street behind where Aden was hiding. Another airman ran from the helicopter toward the Blackhawk that had crashed. The shooting got even worse then. It was so loud that the sound of the helicopter and the guns was just one continuous explosion. Bullets were hitting and rocking the old car that was shielding Aden. He curled himself into a ball and wished he was someplace else.

AT THE JOINT OPERATIONS Center next to the airport, cameras on three surveillance helicopters had captured close-up and in color the crash of the helicopter, code-named Super 61. Maj. Gen. William F. Garrison and his command staff had watched it live: pilot Cliff Wolcott’s black chopper moving smoothly, then a shudder and puff of smoke near the tail rotor, then an awkward counter-rotation as Super 61 fell, making two slow turns clockwise, nose up until its belly bit the top of a stone building and its front end was cast down violently, rotors snapped and flying, its fuselage smashing into a narrow alley on its side against a stone wall in a cloud of smoke, dust and debris.

There wasn’t enough time for anyone to consider all the ramifications of that helicopter’s sudden end, but the sick, sinking feeling that came over officers watching on screen went far beyond the immediate fate of the six men on board.

America’s 10-month mission to Somalia, handed off by one president to another, the latest symbol of the nation’s commitment to a New World Order, had just taken a crippling hit. The ambitious nation-building hopes of United Nations bureaucrats were lying in a twisted hunk of smoldering metal, plastic and flesh in an alley in northern Mogadishu.

CHAPTER 4

An Outgunned but Relentless Enemy

AFTER ROPING DOWN from their Blackhawk, the Rangers on Chalk One fanned out around the southeast corner of the target house in Mogadishu.

As far as Chalk One knew, things were going well. The mission had been quieter for them than for the Rangers one block west on Hawlwadig Road. But now gunfire was picking up, and in a matter of minutes Cliff Wolcott’s Blackhawk would be shot down just five blocks away.

The Chalk One men were hunkered down, taking cover from Somalis at an intersection of dirt alleys. Both alleys were deeply rutted and littered with debris.

Dirt popped up all around Ranger Sgts. Mike Goodale and Aaron Williamson, who were crouched behind the rusted hulk of a burned-out car. A Somali with an AK-47 leaned out from behind a corner and rattled a burst.

Goodale hopped and ran, but there was no safe place to hide. He dived behind a pipe protruding from the road. It was only 7 inches wide and 6 inches high. He felt ridiculous cowering behind it. When the shooting ceased momentarily, he rejoined Williamson behind the car, just as the Somali opened up again.

Goodale saw a spray of bullets walk up the side of the car and down the side of Williamson’s rifle, taking off the end of his finger. Blood splashed up on Williamson’s face and he began screaming and cursing.

“If he sticks his head out again I’m taking him,” he told Goodale.

Severed fingertip and all, Williamson coolly leveled his M-16 and waited, motionless. Bullets were still snapping around them.

When the shooter showed his face again, Williamson fired. There was a spray of blood, and the man fell over hard. With his uninjured hand, Williamson exchanged a high five with Goodale.

Moments later, another Somali sprinted away from them. As he ran, his loose shirt billowed out to reveal an AK-47, so Goodale and Williamson shot him. As the man lay on the street, Goodale asked Chalk One’s medic if they should check him out. The medic shook his head and said, “No, he’s dead.”

That startled Goodale. He had just killed a man. Only two years earlier, he had been partying hard at the University of Iowa, flunking out and joining the Rangers. His two years with the Rangers had been mostly a great time. Soldiering was fun. This was something else. The man had not actually been shooting at him when he fired, so was it right to shoot? Goodale stared at the man in the dirt, his clothes tangled around him, splayed awkwardly in the alley.

Across the alley, Chalk One’s commander, First Lt. Larry Perino, a stocky West Point man, was watching Somalian children walk right up the street toward his men, pointing out the Americans’ positions for a hidden gunman. His men threw flash-bang grenades, which scattered the children momentarily.

Perino sprayed rounds from his M-16 at their feet. They ran away again.

Then a woman began creeping toward Staff Sgt. Chuck Elliott’s M-60 machine gun, which the men called a “pig” because of the grunting sound it made when fired.

“Hey, sir, I can see there’s a guy behind this woman with a weapon under her arm!” Elliott shouted.

Perino told Elliott to fire. The 60-gun made its low, blatting sound. The man and the woman fell dead.

ONE BLOCK NORTH, at the northeast corner of the target block, were the Rangers in Chalk Two. Spec. Shawn Nelson, the unit’s 60-gunner, set up his “pig” at the crest of a slight rise in the road.

At 23, Nelson was a little older than his buddies. When the corporate training program he attended after high school in Atlanta abruptly folded, he had enlisted. He felt protective of his fellow Rangers, and not just because of his big gun. They were the first real family he had ever had.

He could see Somalis aiming guns at the southwest corner of the target block, where Chalk Three had roped in. One Somali, an old man with a bushy white afro, was so intent that he didn’t run like the others when Nelson fired.

“Shoot him, shoot him,” urged Nelson’s assistant gunner.

“No, watch,” Nelson said. “He’ll come right to us.”

Sure enough, the man practically walked up to them. He ducked behind a tree 50 yards up and was loading a new magazine in his weapon when Nelson put about a dozen rounds into him. The bullets went right through the man, chipping the wall behind him, but still he got up, retrieved his weapon, and fired again. Nelson was shocked. He squeezed another burst. The man managed to crawl behind the tree. This time he didn’t shoot back.

“I think you got him,” said his assistant gunner.

But Nelson could still see the afro moving behind the tree. He blasted another long burst. Bark splintered off the tree and the man slumped sideways. His body was quivering and he seemed to have at last expired. Nelson could not believe how hard it was to kill a man.

Taking cover next behind a small car, Nelson saw a Somali with a gun prone on the dirt between two kneeling women. He had the barrel of his weapon between the women’s legs, and there were four children actually sitting on him. He was completely shielded by noncombatants.

“Check this out, John,” Nelson told Spec. John Waddell.

“What do you want to do?” Waddell asked.

Nelson threw a flash-bang at the group, and they fled so fast the man left his gun.

Crouching nearby, Staff Sgt. Ed Yurek’s attention was called to a nearby tin-walled shed.

“Hey, we’ve got people in the shed!” shouted Chalk Two’s medic.

Yurek sprinted across the street, and, with the medic, plunged into the shed, nearly trampling a huddled mass of terrified children. With them was a woman, evidently their teacher.

“Everyone down!” Yurek shouted, his weapon ready.

The children wailed, and Yurek realized he needed to throttle things back.

“Settle down,” he pleaded. “Settle down!” But the wailing continued.

Slowly, Yurek stooped and placed his weapon on the ground. He motioned for the teacher to approach him. He guessed she was a young teenager.

“Lay down,” he told her, speaking evenly. “Lay down,” gesturing with his hands.

She lay down, hesitantly. Yurek pointed to the children, gesturing for them to do the same. They got down. Yurek retrieved his weapon and addressed the teacher, enunciating every word, vainly trying to bridge the language barrier. “Now, you need to stay here. No matter what you see or hear, stay here.”

She shook her head, and Yurek hoped that meant yes. As they left, Yurek told the medic to guard the door. He feared somebody would barge in shooting.

Up the alley, Nelson saw a man with a weapon ride out into the open—on a cow. There were about eight other men around the animal, some with weapons. Nelson didn’t know whether to laugh or shoot. In an instant, he and the rest of the Rangers opened fire. The man on the cow fell off, and the others ran. The cow stood stupefied.

Just then, a Blackhawk slid overhead and opened up with a minigun. The cow literally came apart. Great chunks of flesh flew up. Blood splashed. When the minigun stopped and the helicopter’s shadow passed, what had been the cow lay in awful, steaming pieces.

Those powerful guns overhead were deeply reassuring to the men on the ground. On the streets of a hostile city with bullets snapping past, where the smell of blood and burnt flesh mingled with the odor of garbage and dung, the thrum of the Blackhawks reminded them they were not alone.

As the helicopter moved off, yet another crowd of Somalis began to form. Nelson tried to direct his fire only at people with weapons, but those with guns were intermingled. He debated only momentarily before firing. The group dispersed, leaving bodies in the alleyway. Quickly another, larger group began to mass. People were closing in, just 50 feet up the road, some of them shooting.

Nelson wasn’t weighing issues anymore. He cut loose with the M-60, and his rounds tore through the crowd like a scythe. A Little Bird swooped in and threw down a flaming wall of lead. Those who didn’t fall fled. One moment there was a crowd, and the next instant it was just a bleeding heap of dead and injured.

“Goddamn, Nelson!” Waddell said. “Goddamn!”

CHAPTER 5

‘My God, you guys. Look at this!’

November 19, 1997

JUST AFTER he had leveled the Somalian crowd with his M-60, leaving the street strewn with bodies, gunner Shawn Nelson heard the approach of a Blackhawk. It was Super 61, Cliff Wolcott’s bird.

Chief Warrant Officer Wolcott was a funny guy whom everybody called Elvis because he affected the hair, walk and talk of his musical idol. There were guys in his unit who had known Elvis for years but would scratch their heads if you asked them about somebody named Cliff Wolcott. His exploits were legendary. He had flown secret missions behind enemy lines during the Persian Gulf war, refueling in flight, to knock out Saddam Hussein’s Scud missile sites in Iraq.

On this mission, Wolcott’s Super 61 had delivered a Chalk of Rangers and was now flying a low orbit over the target area in central Mogadishu. The bird’s two crew chiefs were blasting targets with their mounted miniguns, and two Commando snipers in the rear were picking off Somalian gunmen. Every time the sleek black copters moved overhead, it gave the guys on the ground a good, protected feeling the boys called “a warm and fuzzy.”

As Wolcott’s Blackhawk passed overhead, Nelson’s eye caught the distinctive flash and puff of an RPG—a rocket-propelled grenade. He saw the rocket climb into the helicopter’s path. Then came a thunderclap. The bird’s tail boom cracked, the rotor stopped spinning with an ugly grinding sound, and a chug-chug-chug coughing followed. The whole helicopter shuddered and started to spin—first slowly, then picking up speed.

“Oh, my God, you guys. Look at this!” Nelson said to the Rangers crouching with him. “Look at this!”

Wolcott’s bird moved directly over them, spinning faster now.

Pvt. John Waddell, gasped, “Oh, Jesus.” He fought the urge to just stand and watch the bird go down. He turned away to keep his eyes on his corner, watching for Somalian gunmen.

Nelson couldn’t stop watching. The helicopter started to tilt as it hit the top of a house, then flipped over as it crashed into an alley, on its side.

“It just went down! It just crashed!”

The disbelief in Nelson’s voice echoed the feelings of every soldier on the corner.

“What happened?” called First Lt. Tom DiTomasso, the Chalk Two leader, who came running.

“A bird just went down!” Nelson said. “We’ve got to go. We’ve got to go right now!”

He knew the six men inside the Blackhawk needed help immediately—before Somalis got to them.

Word spread wildly over the radio, voices overlapped with the bad news. There was no pretense now of the deadpan calm of radio transmissions, the mandatory military monotone that said everything was under control. This was dreadful shock. Voices rose with surprise and fear:

“We got a Blackhawk going down! We got a Blackhawk going down!”

“We got a Blackhawk crashed in the city! Sixty-one!”

“Sixty-one down!”

It was more than a helicopter crash. It was a blow to the sense of invulnerability in all the young men on the ground. The Blackhawks and Little Birds were their trump cards. The helicopters, even more than the Rangers’ rifles and machine guns, were what kept gunmen at a distance.

Nelson saw smoke and dust rising from the crash three blocks east. He saw crowds of Somalis running in that direction, and guns poking out of windows nearby. He spotted two boys running toward him, one with something in his hand. He dropped to one knee and felled them both with a burst from his M-60. One had been holding a stick. The other got up and limped for cover.

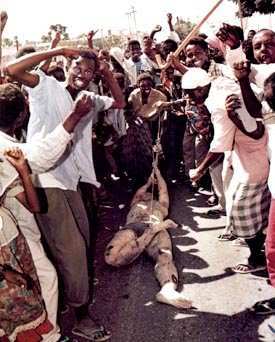

Nelson’s buddy Waddell was feeling the same urge to run toward the crash. When another unit’s Blackhawk had gone down two weeks earlier, the dead crew members were mutilated by the crowds. In the hangar the Rangers had talked about it. They were determined that such a thing would never happen to their guys.

But now they had to get permission on the radio from Capt. Mike Steele, the Ranger commander. Steele understood the urge to go help, but if Chalk Two left, the security perimeter around the target building would break down. He tried to get on the command network, but the calls were coming so thick and loud now he couldn’t be heard.

“We need to go!” Nelson shouted at DiTomasso. “Now!”

Nelson started running at the same moment Steele called back. The captain had decided to authorize it himself.

DiTomasso ordered half of Chalk Two to stay at the target house. He took the other half—eight men—with him to the Blackhawk crash, running full trot to catch up with Nelson.

IT HAD TAKEN Chief Warrant Officer Keith Jones, piloting a Little Bird with the call sign Star 41, a few minutes to find the crash. Chief Warrant Officer Mike Goffena, piloting Blackhawk Super 62 above him, had helped guide him.

“Two hundred meters. One hundred meters. You are coming over it right and low. Just passed it.”

Jones banked hard left and then flew in. Landing in the big intersection closest to the downed Blackhawk would have been easier, but he didn’t want to sit down where he would make a fat target from four different directions. So he’d eased his copter onto the street called Freedom Road and set it down on a slope between two stone houses.

Jones saw dark smoke choking the interior of the downed Blackhawk, and he knew just looking at it that his friends Elvis and Donovan “Bull” Briley, the copilot, were probably dead.

Somalis were coming at them. Both Jones and his copilot, Karl Maier, fired with handguns. Then Sgt. Jim Smith, a Commando sniper who had climbed out of the Blackhawk wreckage, appeared alongside Jones’ window. It was Smith who had encountered Abdiaziz Ali Aden, the slender Somalian teenager who had hidden inside the old car nearby.

Now, over the din of the helicopter, Smith mouthed the words: “I need help.” Smith had been shot in the meaty part of his left shoulder. The wounded sniper had dragged his injured Commando buddy, Staff Sgt. Daniel Busch, from the wreckage and positioned him against the wall with his weapon. While propped there, Busch had been shot again.

Jones hopped out and followed Smith to the downed Blackhawk, leaving Maier to control the Little Bird and provide cover up the alley.

Seconds after Jones left, Lt. DiTomasso rounded the corner and came upon the Little Bird. Maier nearly shot him. When Maier lowered his weapon, the startled lieutenant tapped his helmet, indicating he wanted a head count on casualties. Maier didn’t know.

Nelson and the other Rangers behind DiTomasso went after Jones and Smith. They saw that Busch, the gung-ho commando everybody called “Rambusch,” had a bad gut wound. His SAW (squad automatic weapon) was on his lap and a .45-caliber pistol was on the ground in front of him. Busch, a devoutly religious man, had told his mother before leaving for Somalia: “A good Christian soldier is just a click away from heaven.”

Nelson found three Somalian bodies beside Busch. There was a woman and two men. One of the men was still breathing and trying to move, so Nelson pumped two finishing rounds into him. He then got down behind the bodies for cover while Jones and Smith pulled Busch uphill to the Little Bird. Nelson picked up Busch’s pistol and stuck it in his pocket.

The rest of the squad fanned out to form a perimeter. Jones and Smith were having trouble dragging Busch, so Jones stooped and lifted him with both arms, and placed him in the small back door of the Little Bird. Then he helped the wounded Smith into the helicopter.

Jones examined Busch. He had been shot in the belly, just under his armor plate. His eyes were gray and rolled up in his head. He was still alive, barely, but Jones knew there was nothing he could do for him. He needed a doctor immediately. Jones climbed back into his pilot seat. On the radio he heard the command from the bird overhead.

“Forty-one, come on out. Come out now.”

With intensifying fire, there was a real risk that the Little Bird would be damaged and get stranded on the ground. Smith and Busch needed doctors. The pilots would have to leave the rest of the Super 61 crew and hope the Rangers could hold on until more help arrived.

Jones grabbed the stick and told Maier, “I have it.”

Jones told the command network: “Forty-one is coming out.”

CHAPTER 7

Another Grenade, Another Chopper Hit

November 22, 1997

PILOT MIKE GOFFENA was moving his Blackhawk up behind Mike Durant’s bird when the grenade hit. The two helicopters were supposed to be opposite each other in orbit over the target area in Mogadishu, but Durant’s Super 64 hadn’t been in the formation long enough to get in sync. Durant was still struggling to take the spot vacated by Cliff Wolcott’s Super 61, which lay smoldering on the ground after being shot down minutes earlier.

Goffena, flying Super 62, was closing in fast from behind when he saw the hit to Durant’s gearbox. The grenade blew off a chunk of it. Goffena saw all the oil dump out of the rotor in a fine mist, but the bird stayed intact, and everything seemed to still be functioning.

“Sixty-four, are you OK?” Goffena radioed to Durant.

The Blackhawk is a big aircraft. Durant’s chopper weighed 16,000 pounds with crew and gear, and the tail rotor was a long way from where he sat. Goffena’s radio call came before Durant had even sorted out what had happened. He heard Goffena explain that he had been hit by an RPG fired by Somalis, and that there was damage to the tail area.

“Roger,” Durant radioed back, coolly.

He didn’t feel anything unusual about the Blackhawk at first. He did a quick check of his instruments and saw that all the readings were OK. His crew in back, Staff Sgt. Bill Cleveland and Sgt. Tommy Field, were unhurt. So after the initial shock, he felt relief. Everything was fine. Goffena told him he had lost his oil and part of the gearbox on the tail rotor, but the sturdy Blackhawk was built to run without oil for a time if necessary, and it was still holding steady.

Durant had faith in the aircraft, but it had absorbed a strong impact. The air mission commander, Lt. Col. Tom Matthews, who had seen the hit from the command-and-control helicopter circling above, told him to put the bird on the ground. Super 64 was out of the fight.

Durant pulled out of his left-turning orbit and pointed back to the Americans’ airfield, about a four-minute flight southeast. He could see it off in the distance against the coastline. He noted, just to be safe, that there was a big green open area between him and the airfield, so if he had to land sooner, he had a place to put his helicopter. But the bird was flying fine.

Durant was the calm, collected type—a true pro. He had been with the secretive 160th SOAR (Special Operations Aviation Regiment), the Night Stalkers, long enough to be a veteran of dangerous, low-flying, night missions in the Persian Gulf war and the invasion of Panama.

He had learned to conduct himself with such discipline that many of his neighbors in Tennessee, near the Night Stalkers’ base in Fort Campbell, Ky., didn’t even know what he did for a living. His own family often didn’t know where he was. In fact, he’d been given just two hours’ notice of his assignment to Somalia. There had been just enough time to drive home and spend 15 minutes with his wife, Lorrie, and his baby son, Joey, and to explain that he would have to miss the child’s first birthday three days later.

Sometimes it seemed that all he did was fly missions, or train for them. Practice defined the lives of the Night Stalker pilots. They practiced everything, even crashing. Their moves in the electronic maze of their cockpits were so well-rehearsed they had become instinctive.

Now Durant steered his crippled Blackhawk southeast over Mogadishu, toward the Indian Ocean and the base. His friend Goffena made a quick decision to follow him. Goffena’s Super 62 had been providing cover for the target building and the crash site, where the Super 61 Blackhawk piloted by Cliff Wolcott had gone down from an RPG hit. Goffena had seen a rescue team rope in at Wolcott’s downed bird, and the forces around the target building were getting ready to leave. Prioritizing quickly, he decided he would see his four friends in Durant’s crippled bird at least part of the way safely home.

Goffena followed Super 64 for maybe a mile, to a point where he felt confident it would make it back. He was preparing to turn around when Durant’s tail rotor, the whole assembly—the gearbox and two or three feet of the vertical fin assembly—just turned into a blur and evaporated.

Inside Super 64, Durant and his copilot, Ray Frank, felt the airframe begin to vibrate rapidly. They heard the accelerating, high-speed whine of the dry gear shaft in its death throes. Then came a very loud bang. With the top half of the tail fin gone, a big weight was suddenly dropped off the airframe’s back end, and its center of gravity pitched forward.

As the nose lunged down, the big bird began to spin. After a decade of flying, Durant’s reactions were instinctive. To make the airframe swing left meant pushing gently on the left pedal. He now noticed he had already jammed his left pedal all the way to the floor and his craft was still spinning rapidly to the right. The rotation of the big rotor blades wanted to make the airframe spin that way, and without a tail rotor there was no force to stop it.

The spin was faster than Durant ever imagined it could be. Details of earth and sky blurred, the way patterns do on a spinning top. Out the windshield he saw only blue sky and brown earth.

They were about 75 feet above ground when Goffena saw the Blackhawk spin 10 or 15 times in the seconds before it hit. It all happened too fast. Durant was trying to do something with the flight controls. Frank, in the seat next to him, somehow had the presence of mind to do exactly the right thing.

In crash simulators, pilots are taught to eliminate torque by shutting off the engines. But the controls for the engines were on the roof of the cockpit, so Frank had to fight the spin’s strong centrifugal force to raise his arms. In those frantic seconds he managed to flip one engine switch to idle and turn the other halfway off.

Durant shouted into his radio: “Going in hard! Going down!”

He screamed his copilot’s name: “Raaaay!”

Goffena was amazed to see the plummeting helicopter’s spin rate suddenly slow. And just before impact, the nose of the bird came up. Whether for some aerodynamic reason or something Durant or Frank did inside the cockpit, the falling chopper leveled off.

With the spin rate down to half what it had been, and with the craft fairly level, the Blackhawk made a hard but flat landing.

Coming down flat was critical. It meant there was a chance the four men inside Super 64 were alive.

CHAPTER 8

A Second Crash, And No Escape

November 23, 1997

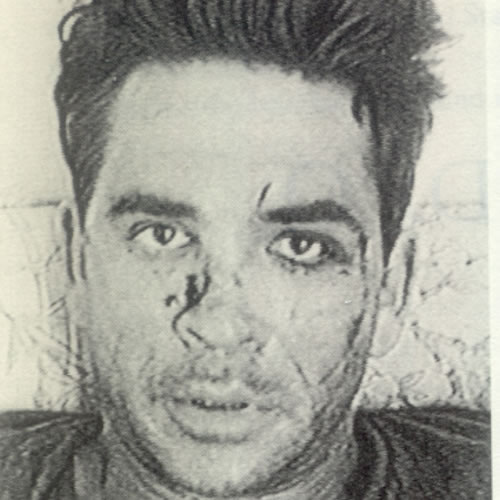

The crew of Super 64 a month before the battle. From left: Tommy Field, Bill Cleveland, Ray Frank and Mike Durant.

CIRCLING IN HIS HELICOPTER over Mike Durant’s downed Blackhawk, pilot Mike Goffena saw that Durant had been lucky. His helicopter had crashed not into one of the many stone buildings in central Mogadishu, but into a warren of flimsy tin huts.

The chopper hadn’t hit anything hard enough to flip it over. A Blackhawk is built with shock absorbers to withstand a terrifically hard impact, so long as it lands in an upright position. And Durant’s Super 64 Blackhawk was indeed upright.

In other ways, Durant and his three crew members were less fortunate. The crash site was about a mile from the commandos and Rangers on the ground near the downtown target site. Durant had been shot down while taking the place of Cliff Wolcott’s Blackhawk, which had crashed only a few blocks from the American troops.

The only airborne search-and-rescue team had already fast-roped down to Wolcott’s bird, so there would be no easy way to reinforce Durant’s crash site. If there had been an irremediable flaw in this mission, it was this lack of a second rescue force. Nobody had taken seriously the prospect of two helicopters going down. From above, Goffena could already see Somalis spilling into alleyways and footpaths, homing in on the newly downed bird.

Goffena flew a low pass and caught a glimpse of Durant in the cockpit, pushing at a section of tin roof that had caved in around his legs. Goffena was relieved to see that his friend was alive.

He flew close enough to catch the frustrated look on the face of Durant’s copilot, Ray Frank. Frank had been in a tail-rotor crash like this one on a training mission several years before. It had broken his leg and crunched his back, and he had been involved in a legal battle over it ever since. To Goffena, the look on Frank’s face down there said, I can’t believe this has happened to me again!

Then, in the back of the crumpled Blackhawk, Goffena saw movement. This told him that at least one of the crew chiefs, either Bill Cleveland or Tommy Field, was still alive.

At this point, 4:45 p.m., command conditions were on overload. Most of the Rangers and Commandos inserted at the target building were moving to the site of Wolcott’s downed helicopter, where the air-rescue team had already roped in.

The situation report from the command helicopter sounded beleaguered.

“We are getting a lot of RPG fire. There’s a lot of fire. We are going to try to get everyone consolidated at the northern site [Wolcott’s crash] and then move to the southern site [Durant’s crash].”

In the back of Blackhawk Super 62, Goffena had, in addition to his two crew chiefs, three commandos: snipers Randy Shughart, Gary Gordon and Brad Hallings. With Somalis closing in, he knew Durant’s downed crew wouldn’t last long. They were an air crew, not professional ground fighters like the boys.

Goffena’s crew gunners and the snipers were now picking off armed Somalis. Goffena would drop down low, and the wash of his propellers would force the thickening crowds back. But the men with RPGs were slower to take cover, and his snipers were picking them off.

Goffena also noticed that every time he dropped down now, he was drawing more fire. He heard the ticking of bullets poking through the thin metal walls of the airframe. A couple of times he saw a glowing arc where a round would hit one of his rotor blades, which would spark and trace a bright line as the blade moved.

Goffena’s Blackhawk and other helicopter gunships were holding the crowds back. Goffena and the other circling pilots worked the radio, pleading for immediate help. They were repeatedly assured that a rescue by the hurriedly assembled ground convoy was imminent.

But Goffena’s air commander, realizing that it was taking too long to get the new column up and moving, approved Goffena’s request to put two of his helicopter’s three commandos on the ground. The idea was for them to give first aid, set up a perimeter, and help Durant and his crew hold off the Somalis until the arrival of a rescue force.

This was not a hopeless mission. One or two properly armed, well-trained soldiers could hold off an undisciplined enemy indefinitely. Shughart and Gordon were experts at killing and staying alive. They were career soldiers trained to get hard, ugly things done. Gordon had enlisted at 17; his wife and children lived near Fort Bragg, N.C. Shughart was an outdoorsman from Western Pennsylvania who loved his Dodge truck and his hunting rifles.

When the crew chief gave Gordon the word that he and Shughart were going in, Gordon grinned and gave an excited thumbs-up. Goffena made a low pass at a small clearing, using his rotor wash to knock down a fence and blow away debris. He held a hover at about five feet, and the two boys jumped.

Shughart got tangled on the safety line connecting him to the chopper and had to be cut free. Gordon took a spill as he ran for cover. Shughart stood motioning with his hands, indicating their confusion. They were crouched in a defensive posture in the open.

Goffena dropped the copter down low and leaned out the window, pointing the way. A crew chief popped a small smoke marker out the side in the direction of Durant’s helicopter. Shughart and Gordon ran to the smoke. The last thing the crew chiefs saw as the Blackhawk pulled away was both men signaling thumbs-up.

MIKE DURANT CAME TO and felt something was wrong with his right leg. He had been knocked cold for at least several minutes. He was seated upright in his seat, leaning slightly to the right. The windshield of his Blackhawk was shattered, and there was something draped over him, a big sheet of tin.

The helicopter seemed remarkably intact. The rotor blades had not flexed off. Durant’s seat, which was mounted on shock absorbers, had collapsed down to the floor. It had broken in the full down position and was cocked to the right. He figured that was because they were spinning when they hit. The shocks had collapsed, and the spin had jerked the seat to the right.

It must have been the combination of the jerk and the impact that had broken his femur. The big bone in his right leg had snapped in two on the edge of his seat.

The Blackhawk had flattened a flimsy hut. No one had been inside, but in the next hut a 2-year-old girl, Howa Hassan, lay unconscious and bleeding. A hunk of flying metal had taken a deep gouge out of her forehead. Her mother, Bint Abraham Hassan, had been splashed with something hot, probably engine oil, and was severely burned on her face and legs.

The dazed pilots checked themselves over. Ray Frank’s left tibia was broken. Durant did some things he later could not explain. He removed his helmet and his gloves. Then he took off his watch. Before flying he always took off his wedding ring because there was a danger it could catch on rivets or switches. He would pass the strap of his watch through the ring and keep it there during a flight. Now he removed the watch and took the ring off the strap, and set both on the dashboard.

He picked up his weapon, an MP-5K, a little German automatic rifle that fired 9mm rounds. The pilots called them “SPs,” or “skinny-poppers,” a reference to the nickname “skinny” the soldiers had bestowed on the wiry Somalian militiamen.

Frank was trying to explain what happened during the crash.

“I couldn’t get them all the way off,” he told Durant, explaining his struggle to turn off the engines as the helicopter plummeted. Frank said he had reinjured his back. Durant’s back hurt, too. They both figured they had crushed vertebrae.

Durant could not pull himself out of the wreckage. He pushed the piece of tin roof away and decided to defend his position through the broken windshield.

Durant saw that Frank was about to push himself out. That was the last time he saw him. And just as Frank disappeared out the doorway, Shughart and Gordon, the commandos, showed up.

Durant was startled by their arrival. He didn’t know either man well, but he recognized their faces. He knew they were the boys. He felt an enormous sense of relief. He didn’t know how long he had been unconscious, but it had evidently been long enough for a rescue team to arrive.

His ordeal was over. He had been thinking about getting the radio operating, but now, with his rescuers at hand, there was no need.

Shughart and Gordon were calm. They reached in and lifted Durant out of the craft gently, one taking his legs and the other grabbing his torso, as if they had all the time in the world. They set him down by a tree.

He was not in great pain. Durant was in a perfect position to cover the whole right side of the aircraft with his skinny-popper. Behind him the front of his aircraft was wedged tightly against a tin wall, closing off any easy approach from that side.

He could see that his crew chiefs had taken the worst of the crash. They didn’t have the shock absorbers in back. He watched them lift Bill Cleveland from the fuselage. He had blood all over his pants, and was talking but making no sense.

Then Gordon and Shughart moved to the other side of the helicopter to help Tommy Field, the other crew chief. Durant couldn’t see what was happening. He assumed they were attending to Field and setting up a perimeter, or looking for a way to get them out, or perhaps looking for a place where another helicopter could set down and load them up.

Somalis were starting to poke their heads around the corner on Durant’s side of the copter. He squeezed off a round, and they dropped back. His gun kept jamming, so he would eject the round, and the next time it would shoot properly. Then it would jam again.

He could hear more shooting from the other side of the airframe. It still hadn’t occurred to him that Shughart and Gordon were the entire rescue force. There was no big rescue team—other than the emergency ground convoy, which was still forming at the airport base two miles away.

Durant also did not know, none of them did, that only 110 yards or so away, pilots Keith Jones and Karl Maier were waiting. The same team that had set the Little Bird down near the first crash site to help Cliff Wolcott’s downed crew had now set their helicopter down again—to help Durant and his crew.

Jones and Maier were aiming their weapons at alleyways leading to the clearing, expecting a crowd of Somalis to show up any second, and hoping that Shughart and Gordon would arrive with Durant and his crew. They were eager to load everybody up and hustle out of there.

Goffena, circling overhead, had seen Shughart and Gordon lift Durant and then Cleveland and Field out of the fuselage. He knew they weren’t going to be able to carry them to where Jones’ Little Bird was waiting.

He got on the radio and explained to Jones and Maier that the boys had set up a perimeter around Durant’s Blackhawk. They had badly wounded crew members. They could not make it to the Little Bird. They were going to have to hang on until the ground force arrived.

After waiting on the ground about five minutes, Maier and Jones reluctantly asked for permission to leave and refuel. The Little Bird was running low, and they were vulnerable. They lifted off, leaving the Americans at crash site two to their fate.

DURANT’S BLACKHAWK had crashed in Wadigley, a crowded neighborhood just south of where Yousuf Dahir Mo’Alim lived on a street of rag huts and tin-roofed shanties. Mo’Alim was an armed bandit and gunman for hire, but on this day he had thrown his entire gang of 26 street fighters into the citywide effort to fight off the American invaders.

The instant Durant’s helicopter hit the ground, Mo’Alim saw everyone around him reverse direction. Moments before, the crowd on the streets and the fighters had been moving north, over to where the first helicopter had crashed. Now everyone was running south. Mo’Alim ran with them, a goateed veteran soldier waving his weapon and shouting.

“Turn back! Stop! There are still men inside who can shoot!”

Some listened to Mo’Alim, for he was known as a militia leader. Others ran on ahead. Ali Hussein, who managed a pharmacy near where the helicopter crashed, saw many of his neighbors grab guns and run toward the wreck. He caught hold of the arm of his friend Cawale, who owned the Black Sea restaurant. Cawale had a rifle. Hussein grabbed him by both shoulders.

“It’s dangerous. Don’t go!” he shouted at him. But there was the smell of blood and vengeance in the air. Cawale wrestled away from Hussein and joined the running crowd.

Minutes later, as Mo’Alim and his men reached the second crash site, they saw Cawale sprawled dead in the dirt, just four paces in front of the helicopter. The ground all around was littered with the bodies of Somalis. As Mo’Alim had expected, the Americans around the crashed helicopter were still very capable of fighting.

He tried to hold the crowd back, but they were angry and brazen. He wanted to find a way for his militiamen to get clear shots at the Americans, but it was difficult to approach the small clearing where the helicopter lay. The Americans had every approach covered with deadly automatic-weapons fire.

Mo’Alim waited for more of his men to catch up so that they could mount a coordinated attack.

DURANT STILL THOUGHT things were under control. His leg was broken but it didn’t hurt. He was on his back, propped against a supply kit next to a small tree, using his weapon to keep back the occasional Somali who poked his head into the clearing.

He could hear firing on the other side of the helicopter. He knew Ray Frank, his copilot, was hurt but alive. And somewhere were the two boys and his crew chief, Tommy Field. He wondered if Tommy was OK. He figured it was only a matter of time before the ground vehicles showed up to take them out.

Then he heard one of the guys—it was Gary Gordon—shout that he was hit. Just a quick shout of anger and pain. He didn’t hear the voice again.

The other guy, Randy Shughart, came back around to Durant’s side of the bird.

“Are there weapons on board?” he asked.

The crew chiefs carried M-16s. Durant told him where they were kept, and Shughart stepped into the craft, rummaged around and returned with both rifles. He handed Durant Gordon’s weapon, a CAR-15 automatic rifle loaded and ready to fire. He didn’t say what had happened to Gordon.

“What’s the support frequency on the survival radio?” Shughart asked.

It was then, for the first time, that it dawned on Durant that they were stranded. He felt a twist of alarm in his gut. If Shughart was asking how to set up communications, it meant he and Gordon had come in on their own. They were the entire rescue team. And Gordon had just been shot!

Durant explained standard procedure on the survival radio to Shughart. He said there was a channel Bravo, and he listened while Shughart called out. Shughart asked for immediate help, and was told that a reaction force was en route. Then Shughart took the weapons and moved back around to the other side of the helicopter.

Durant felt panic closing in now. He had to keep the Somalis away. He could hear them talking behind a wall, so he fired in that direction. It startled him because he had been firing single shots, but this new weapon was set on burst. The voices behind the wall stopped. Then two Somalis tried to climb over the nose end of the copter. He fired at them, and they jumped back. He didn’t know whether he had hit them.

A man tried to climb over the wall, and Durant shot him. Another came crawling from around the corner with a weapon, and Durant shot him, too.

Suddenly there was a mad fusillade on the other side of the helicopter that lasted for about two minutes. He heard Shughart shout in pain. The shooting stopped.

High overhead in the surveillance helicopters, worried commanders were watching on video screens.

“Do you have video over crash site number two?”

“Indigenous personnel moving around all over the crash site.”

“Indigenous?”

“That’s affirmative, over.”

The radio fell silent.