In "Carry Me Home, Sisters of Saint Joseph," a failed commercial writer moves into the basement of a convent and inadvertently discovers the secrets of the Sisters of Saint Joseph. A girl, hoping to talk her brother out of enlisting in the army, brings Bob Dylan home for Thanksgiving dinner in the quiet, dreamy "North Of." In “The Idea of Marcel,” Emily, a conservative, elegant girl, has dinner with the idea of her ex-boyfriend, Marcel. In a night filled with baffling coincidences, including Marcel having dinner with his idea of Emily, she wonders why we tend to be more in love with ideas than with reality. In and out of the rooms of these gritty, whimsical stories roam troubled, funny people struggling to reconcile their circumstances to some kind of American Ideal and failing, over and over.

The stories of are magical and original and help answer such universal and existential questions as: How far will we go to stay loyal to our friends? Can we love a man even though he is inches shorter than our ideal? Why doesn’t Bob Dylan ever have his own smokes? And are there patron saints for everything, even lost socks and bad movies?

All homes are not shelters. But then again, some are. Welcome to the home of Marie-Helene Bertino.

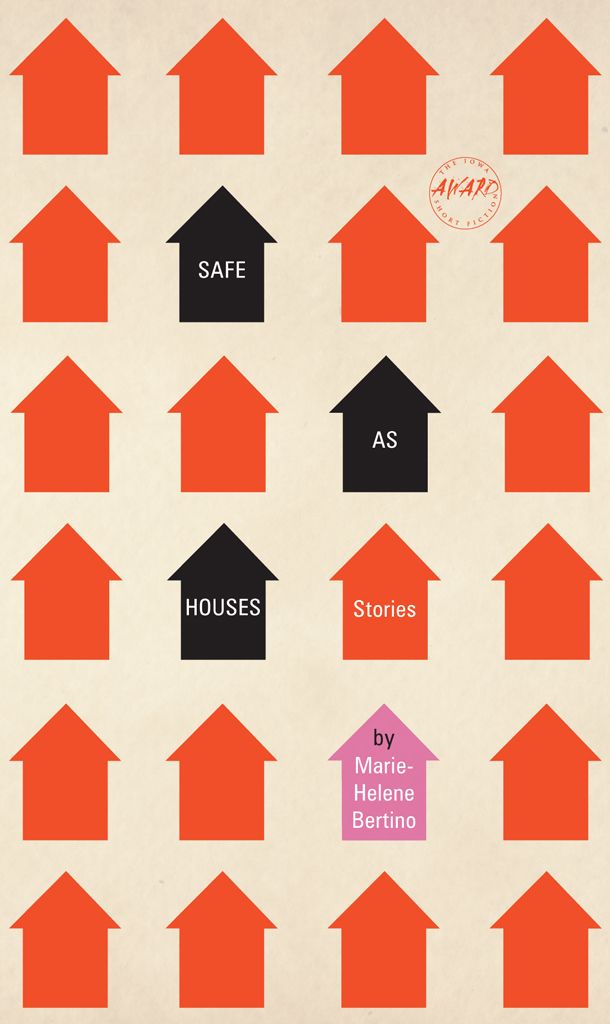

Marie-Helene Bertino

Safe as Houses

In memory of my grandfather Tony who taught me to dance and my grandmother Marie-Louise who signed all her letters

Yours truly,

Marie

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

When I was a little girl, on birthdays or any holiday on which I received a gift, I would become overwhelmed with gratitude. “Thank you” seemed too puny a phrase. So instead I would flush and stammer to the gift giver, “Happy birthday.” During the nine years I worked on these stories, so many people, schools, and organizations pitched in to help and, in doing so, kept me in love with the world. Again, I am overwhelmed with gratitude. Again, “thank you” seems puny. So to the following people, schools, and organizations, I say a heartfelt HAPPY BIRTHDAY:

Renee Zuckerbrot, who protected and clothed me; my inspiring friends in the Brooklyn Blackout Writers’ Group and the Imitative Fallacies — Amelia Kahaney, Elliott Holt, Adam Brown, Elizabeth Logan Harris, Mohan Sikka, and Helen Phillips, who set me up in Brooklyn’s cutest digs; and Mary Russell Curran and Judy Sternlight, who took such care with my work even when it was weird and raw.

Josh Henkin, Lou Asekoff, Ellen Tremper, and Michael Cunningham and Brooklyn College’s unparalleled MFA program; Noreen Tomassi and Kristin Henley at the Center for Fiction and my fellow fellows — Ted Bajek, Mitchell Jackson, Caleb Leisure, Genevieve Mathis, Elizabeth Shah-Hosseini, Mecca Jamilah Sullivan, and James Yeh; Mary Austin Speaker, who made a lovely cover; Hedgebrook Writer’s Residency, Jim McCoy, Charlotte M. Wright, and Allison T. Means at the University of Iowa, and Jim Shepard, who chose this book and gained a lifelong fan in me.

The editors of Mississippi Review, the very first literary magazine to give me a chance.

The beautiful tulips I had the honor of working with at One Story, with special thanks to Rebecca Barry, Karen Friedman, Adina Talve-Goodman, Chris Gregory, Pei-Ling Lue, Michael Pollock, Hailey Reissman, and Hannah Tinti and Maribeth Batcha, under whose wise tutelage I received my real-world MFA.

R.E.M., with thanks for thirty-one years, and Bob Dylan.

My literary soulmates Tsering Wangmo Dhompa, Jesse Hassenger, Tanya Rey, and Scott Lindenbaum; my wife, Cristina Moracho; Tom Grattan, David Ellis, and Anne Ray, the family my adult heart chose; the Fantastic Mr. Fox, Sophie, and Scat, who put their little paws on every submission except this one, funny enough, which was charmed by the paw of poet Ted Dodson, who has an important laugh.

The Glenside Posse, for whom I would take a bullet: Cindy Augustine, Tim Carr, Jessica Bender, Nicole Cavaliere, Jim Fry, Brendan Gaul, Charles Hagerty, Craig Johnson, PJ and Jenna Franceski Linke, Chris Pistorino, Sadie Nickelson Ray, Diana Waters, and Scott Wein, with special love to Ben Cohen and my sisters from another mister — Laura Halasa, Denise Sandole, Shawn-Aileen Clark, Ginger McHugh, Beth Vasil, and Dana Bertotti, who kept saying it was her turn to buy dinner when we both knew it wasn’t.

My brothers, who showed me how to write, with special thanks to Chip Bertino.

This book and anything I ever do is indebted to my mother, Helene Theresa Bertino, who has been called an angel walking around in a human’s body and who taught me to have grace, always.

Safe as Houses

Free Ham

Growing up, I have dreams that my father sets our house on fire. When our house actually does catch on fire, my first thought is, Get the dog out.

Then, because this is the first time our house has burned down and we don’t know what to do, my mother and I enlist the help of a firefighter to perform a Laurel and Hardy routine on the front lawn.

The firefighter begins. “Who was inside the house?”

We answer as a family. “We were.”

“Are you still inside the house?”

“No,” we say. “We’re here now.”

“Who did you think was inside the house?”

“The dog.”

The firefighter makes like he is going to run back in. “The dog is inside the house?”

“No!” We look down at Strudel, who looks back at us.

The firefighter is losing his patience. “Why did you think the dog was inside the house?”

“Sir,” my mother steps forward, her eyes as small as stars. “What is the right answer to this question?”

People drive by, their mouths in angel o’s, trying to make sense of the house with the fire in it. It is as absurd as a dinosaur, hurling its arms and legs through the eaves and gutters.

Two of the angels are a man and his daughter who float by in a car with a shiny hood ornament. He is hunched forward in a gentleman’s suit, and she is in a cotton candy coat. His hand reaches behind him to say, in one smooth gesture, Do not worry. When we get home, our house will not have a fire in it. I pick up a lemon-sized stone from the lawn and wonder whether to aim at the windshield or his face when a firefighter’s voice interrupts me.

“Why are you holding that alarm clock?”

Only then do I notice the small white box in my hand, its cord lost somewhere in the dark grass.

I shake it at him. “It’s mine.”

“You have to throw it out.”

“No, it’s fine.” I turn it over in my hands. It is gleaming.

He shakes his head. “You have no idea how deep that smell goes. Even something that small. You’ll wake up and your room will smell like fire. You’ll think it is happening again.”

I am the kind of person who worries about the feelings of a pudgy firefighter so I say, “I’ll throw it out,” even though I have no intention of doing so. “What can I expect in the upcoming weeks?” I say.

“Vivid dreams,” he says. “Absolute exhaustion.”

I say, “That doesn’t worry me.”

He and I watch the fire. It is so certain. Now and then it pauses to lick at something unseen or to shoot up a clot of red — a glowing, temporary heart.

“I can’t remember a thing,” I say. “Not one thing I had in there.”

“That’s typical,” he says.

…

We are allowed back in to the house at midnight to drag flashlight beams over the charred humps of our possessions. The firefighters assure us we lost everything. But explain the ceramic cat doorstop, arranged in an uncomfortable position yards away from any door and bizarrely intact. “Thank god,” I say. “The doorstop made it.”

My mother swallows something that won’t stay down. Her mouth twitches. Is she laughing or crying? I think laughing. “I don’t have any doors for it to stop,” she says.

Yes, laughing.

…

Great-Aunt Sonya won’t accept rent, but every weekend my mother chauffeurs her to supermarkets all over the city. Sonya gets to use her coupons and ask the salespeople extensive questions about warranties and expiration dates. My mother gets bored waiting, so she fills out entry forms for various contests, only she uses my name.

I am half-sleeping as I hear the woman from Holiday Grocers on Great-Aunt Sonya’s answering machine. The woman trills through a list of acceptable photo IDs I can present when I claim my free ham: driver’s license, social security card, student ID.

I fall into a hard sleep.

…

It is my aunt’s kitchen, or the kitchen of the house we rented one summer. The counters are wide and smooth. On the one near the refrigerator, a chorus line of hams. Flanks flashing! Limbs to the rafters! Decapitated pink!

“Get ’em up there, ladies!” I have a cigar and a stopwatch. I am a coach?

I wake up hysterical, laughing.

…

Because I am in a family, I go to see my father.

His name is Sam so my name is Sam. People ask me if it’s short for something. I say it’s long for “Sa.” I say, His name is Sam so my name is Sam.

There is a beagle on the front lawn of his complex and it is no coincidence that, upon entering his family room, I find him studying a book on beagles, binoculars by his left hand.

I begin. “Hi.”

My father reacts to my voice not unlike people react to car alarms. “Why are you here?”

“I left my jacket in your car last time,” I say.

“So?”

“So it’s not my jacket. It’s my friend’s jacket.”

He throws me the keys. “One of the losers you hang out with.”

“That’s right.” I try to catch and miss. “Even losers get cold in the winter.”

It is my jacket. For some reason I think I have less chance of getting it back if I am honest.

He positions himself in his easy chair. “How’s staying at Aunt Sonya’s?”

“Good, fine.” I nod.

“She getting on your nerves?”

I shrug, lean against the wall. “It’s temporary.”

“Temporary,” he says.

His apartment has not changed since the last time I visited. Maybe a few more dog portraits on the wall. A new frame for the only picture in the room not of a dog. It is a picture of my birth. Pulled like a skinned cat from my mother’s uterus, I am handed to my father, who before he even hears the whirring of the Polaroid makes this face: I have no idea what to do with this thing.

“You still working in that office?” he says.

“No. It was a temporary position.”

“Temporary again,” he says.

“Temping is an extended interview,” I say. I wonder if it’s true.

He doesn’t look at me. “In the meantime, you’ll have no insurance. You’re a real genius, Sam. The decisions you’ve made this year, hell, I’d hire you.”

We play a game, he and I. He says something like, The next time I see you, I am going to back over you with my car, and I sputter around the living room, knocking over framed pictures of Silky Terriers, American Mastiffs.

“Forget the jacket,” I say.

The game goes on, even after I leave. On the train ride home I lock a little boy in my stare. I say, You’re such a bad driver, you’d probably miss.

At home to the dark wall in Great-Aunt Sonya’s spare bedroom, I practice. You’re such a bad driver, you’d probably miss. Sometimes I laugh and laugh.

…

My mother and I spend a day dunking items worth saving into buckets of soapy water. In the end nothing makes it, and we are covered in soot. Soot smells sweet, like syrup. We drive to a diner on the boulevard.

“Smoking or non?” says the hostess.

…

When it is not filled with Christmas trees, it is a parking lot for a movie store, a dentist’s office, and a bakery. A man who works there breathes into his hands, says to the woman standing next to him that it is cold as balls and we should all take a train to Mexico.

As she charges through the makeshift aisles, my mother calls to me. “Are you sure they said free ham and not DVD player?”

“She said, Present photo ID to claim your free ham.”

“Damn. We entered you for a DVD in that one I think.” She pulls a tree from a dark mass, making a small sound of effort. “We have you in so many it’s hard to remember.” She lets the tree fall back into its pile.

I say, “Why didn’t you just enter yourself?”

“What would I do with a free ham? Give it to Strudel?” Strudel, our dog, would have no idea what to do with a free ham.

My mother halts at a ten-foot arrow of an evergreen. She calls to the man who thinks we should all take a train to Mexico.

“Do you have any with less of this?” She fluffs the lower boughs of the tree. “Less of this?”

“Less what?” he says. “Branches?” He counts a wad of money that appears to be all one-dollar bills.

“Yes,” she says.

He is still counting as he leads us to another tree about two-thirds as full. He thrusts his forehead at it by way of presentation.

My mother clicks her tongue. “No. Less. I don’t need all of that. Don’t you have any skinny ones?”

He pulls a tree from a dark pile, more skinny than full but still full.

“No,” she says. “Anything else?”

The man stops counting, a look on his face I’ve seen many times on people who try to talk to my mother.

“We have some dead ones in the back.”

“Now we’re talking!” She claps her hands together.

“I’m kidding,” he says. “They’re all dead. The rotten ones we throw in there.”

My mother looks into the extended yawn of the incinerator. Someone has painted a mouth and fangs on it. “Ouch,” she says. “Don’t you have a place where you put all the trees that people don’t want?”

He jerks his thumb back to the incinerator.

It is my turn. “My mom wants one that looks like a Charlie Brown tree. You know, from the Charlie Brown Christmas special.”

The man exhales a foul-smelling cloud.

“What the feck is that?”

This is too much for my mom and me. It is the end of a long day and we have never heard anything as funny. I slump against a wall of cut trees, wincing. She holds on to my arm as her shoulders shake.

He is a big man, embarrassed. “I couldn’t decide whether to say ‘fuck’ or ‘heck.’” He tries to get us back on task, but we are already gone. My mom and I hold each other and shake. I wipe my eyes with the back of my hand.

“Feck,” I say.

…

Over the next few days I receive messages from area supermarkets; I have won a five-minute shopping spree, a bag of candy, and a hand massage. Finally, the woman from Holiday Grocers calls when I am home. She wants to know if I intend to claim my ham.

“Is that anything like claiming a child?” I am giving Strudel a bath and cooking spaghetti.

The ham lady is confused. “Sorry?”

“It sounds serious. Has my ham done anything wrong?”

“Ma’am, we’re open every day from 8 A.M. to 9 P.M. You’ll have to present a photo ID when you come.”

“I know,” I say. “Passport okay, or do you need my birth certificate?”

…

The first time I understood a wrench I was five, kneeling in the backyard. The lawn gleamed with metal parts that, the box promised, if fit together correctly would yield a bike. My father, holding his ever-present cup of coffee, came to check my progress. I was taking too long or making a racket. He broke the handle off the cup when he threw it. That’s why my right eyebrow takes a break halfway through.

The bike was in the fire. The cup was in the fire.

My father studies different breeds of dogs and watches every dog show on television but has never owned an actual dog. Too messy. Too much to clean up. He and I have had the following conversation more than fifty times.

“You should get a dog.”

“Too messy. Too much to clean up.”

“But a dog might make you happy.”

“A lot of things might make me happy, Sam. That doesn’t mean I want them crapping in my house.”

Sometimes I say, “But a dog would be a good companion.” And he says, “A hooker would be a good companion. That doesn’t mean I want one crapping in my house.” We mix it up, he and I.

…

Now the manager of Holiday Grocers is trying to find me. He has left two messages, no longer mentioning the free ham. Instead, he is encouraging me to pick up a “special prize.” As if I have no memory. As if I am that dumb. I, who was too smart for college. I, who own no material good.

…

I know it is my home because all of my things are there. They are in a parade, a joyous, clanking thing moving endlessly past me. Look, there is my mother’s collection of jelly jars, tin lids raised at attention, and over there my grandmother’s handkerchiefs like starfish tumbling by. Roaring, the tiger’s head with a twanging rubber band held in place over my seventh Halloween. Playing cards, relish spoons, a float of motley tools — flatheads, jigsaws, pipe fitters. Who brings up the rear but my most cherished of all cherished friends, chest to the sun, extending one long leg to the sky and then the other. Kermit doll, you rascal, you green green green. Lovely indispensable things! I remember you.

…

“Read this for me.” Great-Aunt Sonya squints and hands me a can.

“$3.95.”

“Ah.” She hurls it back to the shelf.

“How ’bout this one?” She hands me a can of peaches.

“$2.50.”

“Better,” she says. “For what?”

“Peaches.”

She makes an angry spitting sound. “I hate peaches.”

“Go try down there.” My mother points. “I saw a sign saying two for one.”

Great-Aunt Sonya scuffles down the aisle and my mother turns to face me.

“You still haven’t picked it up? They are going to give it away.”

“I don’t really need a ham.”

My mother makes a motion like she is waving off flies.

“Sam, it’s a free ham.” She says this like she has said the names of several things I am not interested in — college education, marriage, career position. “Go and pick it up before they give it to someone else.”

Great-Aunt Sonya returns with more cans. “Why aren’t you wearing a coat?”

“It must be in the car,” I say.

She turns to my mom. “Why doesn’t she have a coat?”

My mom shrugs and shakes her head.

“Here, hold these.” Great-Aunt Sonya hands me the cans and tries to shake herself out of the arms of her coat. “You’ll take mine.”

“No.” I turn to my mom. “Please tell her no.”

Aunt Sonya insists. “Tell her to take my coat. She can’t walk around with no coat on.”

My mother’s eyes have red in them. “Take it.”

Great-Aunt Sonya cannot shake herself out of her coat. Her sweater is being pulled off in the struggle, revealing the small knot of her shoulder. She pulls while my mother pushes. The thought of taking her coat is more than I can handle. I drop one of the cans and bend to pick it up.

Finally, the coat is off. As my mother hands it to me, she whispers, “She wants you to take the coat so take the coat.”

“I have to run an errand.” I give Great-Aunt Sonya a quick kiss.

My mom panics. “On Christmas Eve? What errand?”

“I’ll meet you back at the house.”

Great-Aunt Sonya waves at me. As I reach the end of the aisle I hear her say, “I’ll bet she is going to meet a boy.”

…

This Christmas, I have done the unthinkable. Out of insurance money I have written a check for four hundred dollars and have received in exchange an earnest-looking dachshund. The dog has small inconsequential feet and a long brown torso. I bring it to my father’s apartment on Christmas Eve afternoon.

He is already tense and complains about his sweater scratching the back of his neck as he answers the door.

The dog takes one look at the apartment and begins hurtling itself against the walls and doorjambs.

My father holds up his cup of coffee as the dog runs laps around our ankles. “What is that?”

“For someone who reads so much about dogs, you sure don’t know too much. It’s a dog.”

“What is it doing here?”

“Running around.”

His television is on.

“I told you I didn’t want a dog. Don’t you listen?”

“I guess not.”

“You get that from your mother. Sure as hell don’t get it from me. There are no dropouts on my side of the family.”

The dog ceases its assault on my father’s apartment. The look it gives me is clear: Get a load of this guy.

My father scratches at his neck. “I can’t believe you brought this thing into my house. You have no head. Where is your head? You’re just like your mother. Stupid. Where did all my smarts go? Where did they go?”

“Don’t know,” I say.

“Something must have translated.”

The dog stabs at its paw with a soft-looking tongue. I cannot think of why I brought it. I want to make a bed where it can sleep. I want to watch it eat. My father glares at the dog with such acute hatred it makes me tired.

“I’m pretty sure any anger I have comes from you, if it makes you feel any better,” I say.

“What’s that supposed to mean?”

“Look, I’ll just take the dog back.”

“What’s that supposed to mean?” he says again.

He clenches his fist into a hard knot and places it in front of my face, shows it to me. I am not thinking. I open my mouth. He winds up and strikes. White for a moment. Then I taste tin blood.

“You can’t help what your parents give you. You hear that?”

“Speaking of,” I am slurring as I slip into my coat. “I have to run.”

“I oughtta pop you in the mouth for bringing this thing here.” His anger has blurred events in his mind; he thinks he hasn’t hit me yet. “You hear me? I should smash you in the face.”

I fix him in my stare so tight he can’t move.

“You’re such a bad driver,” I say. “You’d probably miss.”

…

I make sure I lean over the stretchy-necked microphone.

“I’m here to claim my free ham.”

“Jesus.” The woman behind the counter is startled out of her magazine. “Do you have photo ID?”

“I think you’ll find everything in order.” I hand her my passport.

Her eyes narrow at the sight of a tanner me smiling into the camera. “I remember you.”

She disappears into the back to, I assume, gather my ham’s suitcase.

The sun slides down the oversized windows, dying. If you believed the sky, you would think it was warm outside, but it is cold. It is cold as balls.

Through the windows, I see a girl in a pink coat on a mechanical car pumping her fists and laughing. The man standing next to her is also pumping his fists. It is the same pair from the fire. I see them everywhere. They are so excited about the mechanical car that I feel my head coming apart. My head is coming apart. It will fall off in chunks like wood in fire. The ham lady will emerge and scramble for the phone. Managers will scurry down the aisle from the half-moon room above the cashiers and they will clutch themselves.

I look at my reflection for validation and am surprised at what I see: a small girl in her Great-Aunt Sonya’s coat whose head is decidedly intact. I touch my ears, my hair.

The ham lady returns with a vacuum-sealed mass of pink flesh that looks like it couldn’t do a decent grand jeté.

“This is it?” I am the kind of person who worries about the feelings of a puny dead pig so I soften my tone, but I am not happy. “Why didn’t you just give this to the runner-up?”

“What runner-up?” She punches in a few keys of the cash register. “You’re the only one who entered.”

There is a wordless moment in which we exchange control and she ends up looking smug.

“Oh well.” I lean over again. “I claim this free ham.”

She slides the microphone away from me. “Anything else?”

I look out the oversized windows, over the heads of the man and his daughter, to a point beyond my sight where a dachshund is no doubt chewing the interior of my car. “One more thing.”

I plead with her, I beg, but the ham lady wants to shoulder the ten-pound bag of dog food and will not take no for an answer. They hurt me, these small, brutal kindnesses. She holds the dog food and I hold the ham as we move toward my car. The parking lot is quiet. The sun has died, throwing up a feeble wrist of orange.

The dachshund jumps up in the window and startles the ham lady. “What is that?”

For the second time that day I say, “It’s a dog.”

“What’s its name?”

“Stanley,” I say and then realize, Stanley. Stanley because I don’t know anyone named Stanley. Because it doesn’t mean rise from the ashes, or anything, in Latin.

The ham lady holds the ham so I can reach my keys. A sweet smell hits us as I open the door.

“Eee-oo,” she says. “What is that?”

I heave the dog food in. “It’s fire.”

On my way to Great-Aunt Sonya’s, I park in front of our new/old house. In the backseat on an underweight ham sleeps Stanley, the world’s least identifiable dog. The workers are gone but have left cigarette butts and coffee cups like place markers on the lawn. The doors we picked pose smartly along the back fence. They will have different shuts and knocks in them. The experience of entering the house through these doors will sound new. I will have to get used to it. The innards of our house are exposed; the bathtub is in the driveway, the sink is on the porch. Everything that is supposed to be inside is outside, but the parts are beginning to look like something — home, maybe.

Sometimes You Break Their Hearts, Sometimes They Break Yours

I am like everyone else — good at some things, bad at others. I am good at eating clementines. I am bad at drawing straight lines. I am good at drinking coffee. I would be bad at building a house. If someone asked me to build them a house, I would have to say no. Or I would say yes and worry they would not like the house I built. Why is the kitchen made of coffee filters, they’d say? Why are there no floors? And I’d say, I wish you hadn’t asked me to build you a house.

I am bad at telling stories. For example, this one is about Christmas lights and here is the first time I’m mentioning them. A person who knew how to tell a story would start with, This is a story about Christmas lights I finally got around to putting up last night and the miracle that happened afterward. You know how it is at a party when someone tells an absolute gripper that juggles different characters and lands on a memorable line and everyone holds their stomachs and looks at each other in shocked amazement, a line people repeat on car rides home so they can laugh again? I am not that person. I am the one asking the host what kind of cheese it is I’m eating.

The name of the planet I’m from does not have an English equivalent. Roughly, it sounds like a cricket hopping onto a plate of rice. I am here to take notes on human beings. I fax them back to my superiors. We have fax machines on Planet Cricket Rice. They are quaint retro things, like vintage ice-cube trays.

Human beings, I fax, produce water in their eyes when they are sad, happy, or sometimes just frustrated. Water!

I work as a receptionist for Landry Business Solutions. I have no idea what we do. When people ask I say, When businesses have problems, we have solutions. If they press me, I say it involves outsourcing. A monkey could do my job better and with more hilarious results. I answer the phone, keep the candy jar filled, and monitor the bathroom key. Ten minutes out of my twenty-minute training were candy jar — related. The other ten consisted of bathroom key shakedown tactics. People are always losing the bathroom key, and the receptionist before me must have gotten frustrated because she hot-glued it to a twelve-inch ruler. I have no friends at Landry Business Solutions. I assume they are too busy outsourcing and thinking of solutions. They don’t bother me and, unless they receive a FedEx package, I don’t bother them.

Human beings, I fax, fetishize no organ more than the heart. When they like someone they say, There’s a girl after my own heart. They will stand or sit very close to the person they love with their heart. When they are sad they say, My heart is broken. They will tell large groups of people things they don’t believe. But the heart is just a muscle with an important job. Just an area in the body.

Human beings with bad eyes, I fax, like to try on each other’s glasses. It’s because they want to imagine themselves as new people, not because they want to see out of someone else’s eyes. After the trade is made, one human being normally says, Wow, you are blind.

I am bad at asking for help. When you ask a human being for help, there is a chance they will say later, Remember when you asked for help? Can I have five dollars? That goes for medicine too. I don’t like asking help from pills in a bottle. I don’t want to be woken up at night by a tab of aspirin asking to borrow five dollars.

There’s a reason it’s called alien-ated. Because I am an alien, I am alone. When you are alone, there is no one to tell, “There is a bird whose call sounds like hoo where la hoo!” Or, “There’s a spider landing on your head.” So you tell yourself. There’s a spider landing on my head. I should move.

Of course there are good days. Days when the clementine skin pulls off whole, days I don’t see anyone in a wheelchair on my way to the train.

A week ago, my mother and I were chopping peppers and she said, Let them be big enough so each one is its own mouthful. I don’t like when she says words like mouthful, words that cannot be divorced from sex. Other words like that are suck, fingerhole, and cock. I asked her not to say mouthful anymore. She hopped up and down with the knife in her hand singing, Mouthful! When I got home the Christmas lights snarled at me from their ball on the couch. I ate a mouthful of ice cream and wondered how appliances can be programmed to turn themselves on. If a coffee maker can turn itself on, doesn’t that mean it is never truly off?

Human beings, I fax, spend their lives pretending their parents are people with no needs. They do not want their moms to talk about sex or die.

Human beings, I fax, did not think their lives were challenging enough so they invented roller coasters. A roller coaster is a series of problems on a steel track. Upon encountering real problems, human beings compare their lives to riding a roller coaster, even though they invented roller coasters to have fun things to do on their days off.

Human beings in America, I fax, are separated by how they pronounce the word draw. Draw. Drawr. Drawl, with an l at the end of it. The l is for Live your life. Live your life is what the tattoo said on the lady in line at the liquor store who, when I neglected to notice an open cashier, growled at me that we weren’t getting any younger. I had been daydreaming about drinking coffee, and when she growled I stared at the tattoo for a few seconds, snapping out of it. In not one of those seconds did either of us get any younger.

As a child on Planet Cricket Rice, I lay in bed trying to figure out a way I could know everyone on Planet Earth. America was easy, I could drive through it. Then I would send a letter to one person in every country and they could tell their friends and I could know everyone by association. But language was a problem and I didn’t know every country’s name and I used to get panicky and red-eyed about it.

I have other responsibilities at my job. I seat clients who have problems and are waiting for solutions. Sometimes the person with solutions is late. When people are late to meet me, I assume it’s because they lost track of time while planning my surprise birthday party. I worry; will they remember I like chocolate on chocolate? But most human beings don’t like when other people are late. They get frowny-faced and huffy. So I entertain the clients who wait for solutions. I make the candy jar talk or I tell them I have a friend who has vintage ice-cube trays. You pull a silver crank to release the cubes. I say, Would you like to own vintage ice-cube trays? Normally they say yes because, when they are waiting, human beings can be very participatory. Then I say, Not me! I don’t need getting ice to be a charming experience! I pretend to be very anti — vintage ice-cube tray. In this way I yank the tablecloth out from under the bottle of wine and candle of the conversation.

If you met me, you’d wonder why I do not look like aliens you’ve seen on TV. Why aren’t you green? You’d say, Why isn’t your head overlarge? To answer that I offer this: Landry Business Solutions had a Halloween costume party and Tammy came dressed for a regular day at work. She said, I am a serial killer. We look just like everyone else.

When you’re alone, you are in the right place to watch sadness approach like storm clouds over an open field. You can sit in a chair and get ready for it. As it moves through you, you can reach out your hands and feel all the edges. When it passes and you can drink coffee again, you even miss it because it has been loyal to you like a boyfriend.

If you need it to be about a boy, I’ll give you a boy. In a gas station at the end of the day, the fat owner or the skinny teenager he pays counts the drawer, fills the cigarette machine, and flips the closed sign. My ex was the closed sign. On that gas station or any store that closes. He used to make fun of me for answering questions with metaphors. He’d say, How was your day? And I’d say, If my day were a bug, I would crush it. He wanted me to say, My day was fine. He’s dead now, and by dead I mean dating a stripper. Strippers are girls who can say, My day was fine. Also, they’re very good with money. My exes do well after me. I’m like a lucky penny.

Cars, I fax, are not attached to anything. They are free to collide with other bodies whenever they want and wreck each other. This would not happen with my bumper car system. Cars would be attached to poles linked to an overarching mechanism, as they are in bumper cars. The worst that can happen in a bumper car is you make a strange face when you smash someone. A strange face that makes the other person think you are uglier than they thought and that maybe there are other ugly things they don’t know about you. But they forget in the next second when they are smashed by someone else. It doesn’t hurt, though, as much as real cars. It doesn’t hurt as much.

Here’s the thing about human beings: sometimes you smash their cars, sometimes they smash yours.

One time I got my nails done and the girl held my hands so softly I wondered if she knew me. She commented on the loveliness of my cuticles and she didn’t have to. She went out of her way, and human beings don’t like to go out of their ways. I said, I hope nothing bad ever happens to you.

Five days ago, the bathroom key went missing. Landry Business Solutions has a PA and I made an announcement over it. Why we have a PA is beyond me, since only twelve people work here and they sit in one room. I could have easily walked into that room and made a medium-volumed inquiry, but I don’t like to leave my desk. My announcement over the PA was this: WILL WHOEVER HAS THE BATHROOM KEY PLEASE RETURN IT! Three hours later Delilah slammed the key on my desk. The door had gotten stuck and she had been trapped in the bathroom for hours. No one heard her yelling. She missed a meeting and still no one thought to look for her. She heard my announcement in the bathroom where she sat, hating me. Someone from another office finally heard her and climbed through a heating duct to free her. Delilah, disoriented, left early. It’s a bad day when you realize how unimportant you are.

Human beings who are squeaky wheels, I fax, get everything they want. Quiet humans who don’t complain get nothing. Squeaky wheels will complain when they have an obstructed view of a movie screen until they get a better seat. In the better seat, they will find something else to complain about. The floor is sticky. The cup holder isn’t big enough for my deluxe soda. I have to believe quiet humans who don’t complain see half the screen but are happier. But maybe they’re not. Maybe they spend their lives sad because they can’t participate in conversations about movies. Harrison Ford was in that movie? They say, I had no idea.

It would be easier if it were a boy. Then I could say to Tammy or Grace at work, I feel lonely because of a boy. And they could say, Men are like trains; there’s one every five minutes. But if I say, I am an alien taking notes on human beings to fax to my superiors, they would have no arsenal of information from which to draw. They would not know what to say at all.

Two days ago they passed around a newspaper article at Landry Business Solutions and I realized I do everything wrong. I tie my shoes wrong and they are the wrong shoes. I breathe wrong. I walk wrong. The article was about a place far away whose inhabitants are so poor they have to eat dirt. There was a picture of a dirt-eating girl standing with a bicycle. The right thing to say was what everyone was saying, What a shame. Where’s my checkbook? But what I said was, How did she get her arms to look like that? Is it from the constant bike riding?

It’s not a boy or a job or a family or a house. It’s the world. There are so many people in it.

This is the part with the Christmas lights and the miracle.

Yesterday I stopped to collect a heads-up penny and was late for the train to work. I walked fast to catch it. People who walk fast look weird, and every time I’m walking fast I think how weird I must look. I still missed the train. The doors laughed at me. But trains are like men; there’s one every five minutes. So I got the next one. I wasn’t that late and no one noticed anyway. But the candy jar was empty and I couldn’t get to the store until noon and I smiled at Delilah and she did not smile back. The day was a slippery rock I couldn’t climb. Walking home I heard a couple arguing, and even though he was insisting I knew it was the end.

Then I saw two people in wheelchairs.

You’re not allowed to feel bad about anything when you are around people in wheelchairs, which is why I don’t like people in wheelchairs. You can say, Sometimes at night I wake up and my throat is filled with loneliness and I am choking. And they will say, I am in a wheelchair. And they will win. They are the human pain equivalent of a royal flush. Then I remembered that morning I had collected a heads-up penny and nothing lucky had happened to me. I felt swindled. Behind in the count. It was one of those days.

I got home and there were still the Christmas lights to hang. And it was time. It was not time to check how much sugar I had. It was not time to say the word rose over and over until I forgot what it meant. It was no time other than the time it was to hang the lights. So I got a ladder and a staple gun and climbed to the roof of the house I could not be trusted to build. And I hadn’t asked anyone the proper way to hang lights so I crawled around stapling haphazardly to the shingles, not a line but words. Two words to let my superiors know I was finished taking notes and to come and get me in their glorious spaceships. When I was done I climbed down and checked my work. In lights I had stapled, HELP ME.

I figured it was best to err on the side of honesty. I didn’t learn that on Earth, dear god, but I learned it.

I ate a forkful of cold noodles and went to bed. At 3 A.M. a commotion on my front lawn woke me. It sounded like an army of washing machines in their final cycles had congregated outside my window. My bed hummed. I looked out. Beams of ambitious light jackknifed through the yard. Aggressive angel light. Light that somersaulted and looked like sound. Red lights and white lights.

They were cars. More cars than I could count. The first ones pulled onto my lawn so the others would have room to park behind them. They held human beings who disembarked holding baskets with cloth over them. I recognized my mother, the manicurist, my ex, and the stripper he dates, Delilah. People filled my street and the street next to it and the cars were still coming. I could see headlights for miles. They were still coming.

I was down on my knees. One human being cannot withstand the force of that much kindness.

Do you know what I mean?

The Idea of Marcel

It had been three months since the breakup, and Emily was reclaiming relationship landmarks. She arranged to meet her date at what had been her and Marcel’s second favorite café. The forecast was rain. A pear-colored umbrella hung over the chair where Emily sat wearing a pear-colored skirt, drinking water, and watching two birds chase each other on a tree outside. It was a pursuit whose rules seemed to change at the end of each branch, when with short, pointed bleats the birds would halt and reverse, the chaser becoming the chased.

Next to her, a voice said, “Emily.”

She was still looking out the window, so it was to his reflection that she bid hello before turning to the actual man.

He held out a sleeve of daffodils. “These reminded me of you,” he said. “Cheerful.”

“Marcel.” She placed her nose amidst the yellow heads and breathed. “How considerate and thoughtful.” He was not wearing jeans. She looked at his pants where normally his cell phone perched like a glowing, dinging hip. “No phone?”

He pulled his suit jacket aside to reveal an unencumbered waistline. “I left it at work. Answering your phone at the table is classless.” He sat down. “Tell me about your day. Leave nothing out. Did you interview anyone who reminded you of a childhood memory you’d like to share?”

Emily was a writer for Clef, a magazine for classical music aficionados. She had spent the day learning how a cello is made. “Not unless I was a cello when I was young.”

Marcel’s smile cracked. “I don’t follow.”

“A joke,” she said.

“Fascinating.”

The waiter appeared. Marcel did not rush to order for himself but instead motioned to Emily. “What would you like, buttercup?”

She ordered quiche. He said what a great idea quiche was; then he ordered quiche.

Emily slid her hands over her head to smooth any stray hairs. “You’ve never called me buttercup.”

“Another realization: You are bright. Like a buttercup.” His smile opened. Not a grin, not biting. “I’ve decided to cut down my hours at the gallery. My job has made me careless and impatient. I would have been a better boyfriend had I considered you more. I looked in the mirror, buttercup, and I didn’t like what I saw. Do you think it’s possible to self-renovate? To self-correct?”

“Golly,” said Emily. “How I do.”

This Marcel did not put his hand between her legs. He did not glare at the family seated next to them, whose child had climbed onto the windowsill to yell, “Water!” and “Gladys!”

The quiche came. They ate the quiche. They made comments to each other about the quiche as they ate it.

He said, “Let’s have a farm of children.”

Emily’s mouth was full. “Load me up.”

“I’ll commute to the gallery. You’ll tend our brood. We’ll have Corgi Terriers. A farm of children and Corgis.”

Emily paused, midchew. “You said people today use their dogs like designer handbags.”

“I’ve been too judgmental about people and their dogs.”

Emily stabbed her quiche. “Food for thought, I guess.”

A woman passing their table said, “Emily?” It was Willa, a childhood friend. She beamed at Emily and then, noticing Marcel, blinked several times in shock. “What are the two of you doing here? Marcel, are you wearing a suit?”

Emily cleared her throat. “What brings you here?”

“Dropping off a table.”

“Another Willa gem, I’m sure,” said Marcel. “Someday you will teach me to restore furniture. Stripping an old bureau to uncover its original wood sounds like heaven.”

Willa looked confused. “You said it was glorified trash picking.”

Emily laughed. The child at the table next to them yelled, “Gladys!”

Willa said, “That kid must be driving you batty, Marcel.”

“On the contrary. Emily and I were discussing the farm of children we want to have.”

“Children?” said Willa.

Marcel said, “And Corgis.”

“Corgis?” Willa’s eyebrow jolted toward the ceiling. She turned to Emily. “Come see my table.”

“I don’t want to leave Marcel.”

“Buttercup. See the table.”

Emily followed her friend to the empty dining room in the back. When they were out of earshot, Willa turned and in a calm voice said, “Who the shit is that?”

“Marcel, of course.”

“I thought he defriended you!”

Emily winced.

“Marcel doesn’t wear suits,” Willa said.

“He looked in the mirror and he didn’t like what he saw.”

Willa’s mouth twisted as if it contained a piece of candy she didn’t trust. “Marcel doesn’t look in the mirror.”

“Pessimist,” Emily said. “Dour!”

“Butter,” Willa said, “cup?”

Emily faltered. “He’s more of an idea, I guess.”

“Emily! What are you doing? Having dinner with an idea?”

“I’m just eating quiche.”

Willa used Emily’s elbow to steer her to the door, where they could see Marcel hiding his face behind a napkin from the Gladys kid. He showed it, hid it, then showed it. The Gladys kid yelled, “Peekaboo!”

“That is not Marcel.” Willa’s voice was sad, as if it held a wounded bird. “Take it from someone in the business: some things can’t be refurbished.”

Emily cleared her throat. “Where is the table?”

“There is no table.”

They rejoined the Idea of Marcel. Emily sat down and Willa left.

“Everything copacetic, buttercup?”

Now the name seemed forced, childish. So did the flowers.

The quiche was gone and Emily did not want dessert, but he did not intuit her desire to leave. He ordered an after-dinner liqueur the color of turkey breast. As he sipped from it, she crossed her legs and recrossed them. “Where is the real Marcel tonight?”

He twisted his napkin. “Out and about?”

They sat for a moment in silence.

“He’s with another woman,” she said.

He nodded. The force of this upended her heart. It swiveled and came to rest.

Emily said, “She probably likes soccer more, and pubs.”

He did not seem to want to co-conspire. “Why are you with me if you still think about him?”

“Because I want to be with you. You.” Emily spoke with the aggression of someone who was no longer certain.

“I find talking about an ex during a date to be bad form.”

Emily thought of her first dinner with the real Marcel, here, at this table, in this café. He had told her about his previous girlfriend in such detail they both cried. He had been honest and vulnerable and ratty and present and fucked-up and attainable. He had told a joke about a gynecologist and pretended to use his fork as a headlamp.

The check came. The Idea of Marcel paid, and they sauntered to the street like first dates.

“I’ll walk you home,” he said. “I’ll follow you up the stairs to your immaculate and tasteful apartment. We’ll play jazz LPs and say our opinions about them. Let’s start now. John Coltrane versus Miles Davis: go.”

“Come off it,” she said. “You hate jazz.”

“Then I will call you tomorrow. I won’t be able to get through twenty-four hours without hearing your voice.”

It was a line that sounded better in her mind. “I feel like scrambled eggs,” she said.

He looked confused. “We just had quiche.”

“I mean my head feels like scrambled eggs. I’d like to go home, have a cup of tea.”

“Green tea with honey is my favorite,” he said.

“No,” she sighed. “It’s not.”

…

The rain fell so hard it made the leaves clap. Emily walked to where she knew he would be amidst the applause.

What was a friendship anyway? A pile of leaves and some twine. A dinner every so often. Every so often a long, shattering phone call. By defriending her, Marcel was saying, You are not worth my every so often. This bothered Emily more than the fact that she would never again smell like his soap.

She reached Café Diabolique, their favorite. Marcel and his date sat by the window. Emily was grateful for the camouflage of her umbrella so she could watch them from across the street. Seeing his face after months was as immediate as a pointed gun. He wore jeans and an Iron & Wine T-shirt. He had always listened to the music of a more sensitive man. She had let several relationship cruelties slide because of it.

The woman looked familiar. For a moment Emily mistook her for a mutual friend and prepared to get gorilla earthquake crazy. Then she realized who it was.

It was her. Her her. Emily her. Marcel’s Idea of Emily.

Emily said “ha” out loud. Proof: he still thought of her. She could go home now and sleep, eat, brush her teeth.

At first glance, the other woman was an exact replica. Yet as Emily looked closer, small differences emerged. This woman’s long hair was gathered in a loose ponytail. Soft strands fell into her face.

“Get a barrette!” Emily said.

This woman wore a black T-shirt with a band’s insignia that Emily stepped in a puddle attempting to read.

Marcel was telling a story. He was no doubt expounding on his favorite topic — negative space, how what was not there was as important as what was there. The other woman listened with what looked like rapt attention.

The check came. Marcel in the restaurant and Emily on the street said, “We didn’t order this!” The other Emily laughed like it was funny. She produced a credit card, but Marcel wouldn’t hear of it; this was obvious in his wagging head, hand slicing through the air, no!

So there is a woman on earth he will pay for. Emily sniffed. This woman is nothing like me! I would never wear a band T-shirt on a date! Me, she reminded herself. This me. In front of her, the streetlight clicked to green. It hit her: Marcel was not having dinner with his Idea of Emily but the Emily he wished she was. His Ideal Emily.

Rain slipped off her umbrella and landed at her feet in large gasps. She envied her umbrella because it knew its job and because it felt no pain. Because it had never dated Marcel and because it didn’t have to go around being human, pricing produce, and feeling emotions. Because it had never fallen in love with the South.

Marcel was from Louisiana, so for four years Emily had been southern by association. She insisted on Lynchburg Lemonades. She scheduled interviews around the Gators. She championed gentility. Anyone at a dinner party who thought they could tell a joke making fun of the region encountered a faceful of Emily, quick and ferocious as a convert, as a woman who loved a man.

Emily now had no claim to the South. The region and its interests would proceed without her. Same went for Swiss cheese, drafting tables, being hypoglycemic, the movie Breakin’ and all of its sequels.

She looked back to the couple in time to see a picture she recognized — Marcel before a kiss. He straightened his shoulders and drummed his knees.

The real Emily’s breath halted in her throat. She reached for anything that would stop the moment, a button to summon the walk signal. She pushed and pushed.

Marcel leaned over the table to kiss the (walk!) woman who also leaned in and (walk!), before their lips met (walk! walk! walk!), pulled away.

“Ha,” he said. A word easily gleaned through glass.

Emily narrowed her eyes. “Tease.”

The Ideal Emily anchored her falling hair behind her ear again in, Emily had to admit, a charming way. This woman laughed with her whole body. She made funny faces. Here was a girl you nickname — a soft fruit or a petite flying insect.

The moment was over. Marcel and the woman stood and vanished into the restaurant.

How dare he, thought Emily, invent this dime-store version of me in a band T-shirt! Emboldened by misdirected anger the origin of which was muddy at best, Emily decided to cross the street and confront the couple.

Ironically, the light was red. She waited for the walk signal.

Marcel and the other woman reappeared, pushing through the front door of the restaurant. The rain had downgraded to a measly drizzle. Marcel held out his hand to test. Emily was halfway across the street. She was about to call out when the Ideal Emily jogged in place, yelled “Catch me if you can!” and took off.

Marcel took off after her.

“Ballstein,” Emily said. Since everyone was running, she ran too.

“Emily!” Marcel cried.

“Marcel!” Emily answered, but her voice was lost in the sound of a passing truck.

The Ideal Emily set a fast pace, legs pumping and toned, ponytail beating behind her. The air was thick. The real Emily struggled to breathe, run, and hold her umbrella at the same time. How was chain-smoking, donut-eating Marcel doing it? She could hear his phone clacking against his hip a block away.

As she ran, Emily wondered what it would be like to have a slim pair of scissors as legs. She thought: hummingbird, dragon-fly, peach, pear, mango.

The three-person chase moved down, then up the street.

Finally, simultaneous Don’t Walk lights. The Ideal Emily, the real Marcel, and the real Emily stopped on three different corners. Cars flew by. The real Emily, stooping to catch her breath, heard someone yell, “Buttercup!”

A block away, the idea of Marcel was waving the forgotten sleeve of daffodils and working himself up to a jog.

“I can’t wait until tomorrow!” he said. “I must know your opinions on jazz!”

“Double Ballstein,” Emily said.

All lights turned green. All parties ran.

Emily, now pursued by the Idea of Marcel, chased after the real Marcel chasing after the Ideal Emily.

“Emily!” cried Marcel.

“Marcel!” cried Emily.

“Coltrane!” cried the Idea of Marcel.

The only silent party was the Ideal Emily, jogging beautifully, breasts bouncing in a compelling way.

Wasp nest, horsefly, rotted, maggot-ridden banana.

The Idea of Marcel yelled, “Buttercup! I will catch you if it takes all night!”

Like most strong women, Emily longed for a man to chase after her, screaming epithets of love. However, the Idea of Marcel ran like a giraffe, and his words sounded like they had been translated into Japanese and back to English.

“Exhilarate!” he said. “Brilliant chase!”

Running, Emily rolled her eyes.

Ahead, holding the slim bar of a baby carriage, a mother waited to cross the street. The Ideal Emily ran past, cleanly. The mother pushed her carriage into the path of the real Marcel, who jockeyed around it, lost his footing, yelled, “Fuck, lady!” and kept running. The mother, disoriented, wheeled around into the face of the real Emily. Each dodged right, then left, then right before Emily was able to shake her. She called out apologies as she sprinted away. When he reached the woman, the Idea of Marcel halted, escorted mother and baby across the street, then double-ran to rejoin the pursuit.

“Children,” he cried. “Glorious safety!”

Finally, after reaching some personal landmark of fantastic, the Ideal Emily stopped, pivoted, and performed a pretty jog-in-place while Marcel caught up. A few moments later, Emily caught up, then the Idea of Marcel, who, misjudging his stopping time, hit Emily, who jostled the real Marcel, who looked up and with disbelief said, “Emily?”

The Idea stretched his right leg on a streetlight. “Capital night for a chase.”

“Who the hell is that?” Marcel said.

“Who the hell is that?” Emily pointed to the other woman, who extended her hand. “I’m Emily.”

“I’m Emily,” Emily corrected her.

“We have the same name!” said the woman. “Isn’t that bizarre?”

Marcel looked back and forth. Emily inspected her replacement, starting with the T-shirt. “Fuck a duck. Led Zeppelin?”

“I adore getting the Led out!” cried the woman.

“Why does she talk like an exclamation point?” Emily said.

Marcel lit a cigarette.

“I adore the smell of smoke!”

Emily’s eyes widened. “You made me dumb.”

Marcel said, “Sometimes you were a lot to handle.”

“This lady is weird!” said the Ideal Emily.

Emily sucked in air. “Is that an accent?”

“I’m from Charlotte, North Carolina!” She made Carolina into an eight-syllable word: Ca-o-ro-ah-li-ah-na-uh. Then she raised a knee to her chest and held it. “If you slowpokes are going to argue all night, I’m leaving without you!” With that, she took off again, jogging at a fast clip on a street that ascended in full view, so they could watch her run for what seemed to Emily like a long time.

On an inhale Marcel said, “She was a track star in college. She quit to pursue modeling.”

“She can really haul,” Emily agreed.

“You don’t deserve her,” the Idea of Marcel advanced and stood next to his doppelganger. To Emily’s surprise, the Idea was inches taller. “She deserves someone who appreciates her reticence to try new things. Who thinks experimentation in bed is overrated. Someone…,” he made a dramatic pose with his chin, “who will floss with her. Someone…,” he made fists and showed them to Marcel, “who will fight for her.”

Marcel squinted — his expression when he, mid-sell, stepped away from a painting to feign disinterest. “Is he serious?”

The Idea of Marcel wound up and landed a punch on Marcel’s gut. Marcel cried out in pain and looked to where he had been hit. He threw his cigarette into the street and rose to his tallest height, five feet eight in boots. A moment passed. The mother and baby rolled by, one of the wheels on the carriage wonky, making a cackling sound. After they passed, Marcel lunged at the Idea, who reacted like a rag doll and was thrown around as such. They ended up on their knees on the sidewalk, batting against each other like crabs.

Good gravy, thought Emily. Neither one can fight.

“Bad thinking!” The Idea said. “Assistance, buttercup!”

Emily was torn. She had always wanted Marcel to fight for her. To land a single, grounding punch on a sleaze at a bar. To be resolute and irrational on her behalf. However, enacted in front of her, it seemed dramatic and unnecessary.

She said, “Stop?”

The Idea of Marcel released the real Marcel with a final shove. “Anything you say, buttercup.”

“Buttercup?” Marcel rubbed his arm in pain. “Shows what you know. She hates nicknames.”

“You never tried,” said Emily. “And my name is so good for nicknames!”

“Em-press,” said the Idea. “Em and Em, Em-dash, Em-sixteen.

Emily said, “Shut the fuck up, Marcel.”

Marcel added, “Dickweed.”

The Idea stumbled backward from the force of their synchronized rebuke. “I just want to self-renovate! What’s happening to my arms?” He held one up. It was dematerializing from the elbow to his fingers: one, two, three, four, five. He held up the other, which was exiting the same way.

“Corgis!” he cried, as his thighs and belly vanished. His legs called it quits into the air. His neck sayonara-ed.

He was just lips. “Buuuuutttttteeeeerrrrrcccccuuuuup.” This went on for an awkward amount of time. Finally, he was gone.

Marcel and Emily stared at the empty spot.

She said, “This world is fucking crackers.”

Marcel grinned. “I missed your mouth.” He pointed up the street to where the Ideal Emily, still jogging to nowhere, flickered. A truck drove by. Her specks dispersed. Her long ponytail winked, the last to go.

The Idea and the Ideal were dead, leaving two real people on the street.

Marcel pointed to Emily’s umbrella. “You don’t need that anymore.”

She folded it. “There are disturbing psychological elements afoot tonight.”

“You can say that again,” he said. “I just fought myself and lost.”

Emily did not say it again.

“I would never wear a suit like that,” Marcel said.

He made a mean face. She made a mean face. This was something they used to do.

He said, “I call you by your name. The name your parents gave you. Because I like the name Emily, Emily.”

She said, “If your ideal is…,” she pointed up the street to where her replacement had vanished, “and I am…,” she showcased herself with her hands, “and my idea of you is…,” she raised her hand to indicate a height level, “but you are actually…,” she lowered her hand a few inches, “then doesn’t that mean…” She sat on the curb and covered her face with her hands. “I’m tired,” she said. “I feel like scrambled eggs.”

Marcel sat next to her. “Teatime.”

She uncovered her face. He looked at her.

“You are,” he said, “the genuine article.”

Emily said, “Why do parents bring their kids to restaurants if they’re just going to let them run wild?” She had wanted to ask him all night.

He sighed. “I hate kids.”

“Yes,” she said. “You do.”

…

Emily, alone, walked home. The rain had let up, earthworms and homeless people were back on the street. She handed a quarter to a woman who wagged her digits through fingerless gloves.

“You’re an angel,” the woman said.

Emily said, “I’m just another person on the street.”

Emily passed the first café where, four years earlier, she and the real Marcel had their first date. This night’s reality felt so loose and carbonated that she was certain if she peeked in she’d see them then, four years younger, bent over a piece of cake. He’d be holding his fork out, in the middle of a joke. She’d be wondering if the metal clasp on his jeans was a button or a snap. Would it require wrenching or just a quick, satisfying yank?

Let them talk, this Emily thought. She walked by.

A shattering inside and dull laughter.

Light over the trees, a few stars.

North Of

There are American flags on school windows, on cars, on porch swings. It is the year I bring Bob Dylan home for Thanksgiving.

We park in front of my mom’s house — my mom, who has been waiting for us at the door, probably since dawn. Her hello carries over the lawn. Bob Dylan opens the car door, stretches one leg and then the other. He wears a black leather coat and has spent the entire ride from New York trying to remember the name of a guitarist he played with in Memphis. I pull our bags from the trunk.

“You always pack too much,” I say.

He shrugs. His arms are small in his coat. His legs are small in his jeans.

“Hello hello,” my mother says as we amble toward her.

“This is Bob,” I say.

My mother was married with a small son in the sixties and wouldn’t recognize the songwriter of our time if he came to her house for Thanksgiving dinner. She has been cooking all morning, and all she wants to know is whether somewhere in his overstuffed Samsonite my friend Bob has packed an appetite.

He has. “We’re starving,” I say.

The vestibule is charged with the cold we have brought in. She puts her finger to her lips and points to the dark family room. I can make out a flannel lump on the couch. “Your brother is sleeping. We’ll go into the kitchen.”

The kitchen is bright with food — cheeses, meats, heads of cauliflower, casserole dishes. My mother wipes her hands on an apron she’s had for years. “I wanted him to have his favorite foods before he leaves. For Iraq.” She pronounces it like it’s something you can do. I run, I walk, I raq. “Bob,” she says, “Do you know how to behead a string bean?”

She arranges Bob Dylan at the counter with a knife and a cutting board. I excuse myself.

The downstairs bathroom is lit by a candle. Over the toilet seat, an American flag.

When I return, there is a new voice in the kitchen. I am in time to hear my mother say, “He came with your sister,” referring to Bob, who has amassed a sorry pile of gnarled beans.

“Jeeeeesus.” My brother recognizes him immediately. “It’s nice to meet you.” They shake hands. “Wow, man, wow.”

My brother’s face is blurred with nap but in his eyes grows an ambitious light. It is a spark that could vanish as quickly as it came or succeed in splitting his face open into reckless laughter. I know it can go either way.

I make my voice soft. “Hi there.”

“Hey.” My brother turns, lifts his nose, and sniffs. His smile recedes. “Still smoking?”

I nod. I say, hopefully, “You met Bob.”

He nods.

“Can you beat that?” I say.

“I didn’t know it was a contest.” His smile is gone.

My mother leans over Bob, to reexplain how much of the string bean is “end.”

“I thought you would like to meet him,” I say.

He shrugs. “I thought it would just be family.”

…

I can tell when Bob Dylan needs a cigarette. We excuse ourselves before dinner to the backyard, where everything is dead. In the corner near the fence is a pile of lawn ornaments my mom will put up in the spring. She’s had everything for years. The newest thing is the dining room table, a mahogany affair, and even that is only allowed in the house two days a year, Thanksgiving and Christmas.

Bob Dylan never has his own cigarettes. I thought this was charming at first.

“We’re going to get you a pack today, buddy.” I hit mine against the inside of my wrist and unwind the plastic. I brought Bob here to remind my brother how he used to be, before American flags and Iraq. I thought at least it would give us something to talk about. I give myself the length of a cigarette to admit it; my plan is not going to work.

Bob and I smoke on the edge of the yard. There are no lights on at the Monahans’ house, our neighbors. They normally go to a cousin in New Jersey’s for Thanksgiving.

The grass is frozen. Every so often I stamp on it to hear the crunching sound. Then, without speaking, Bob Dylan and I have a contest. He expels a line of smoke clear to the middle of the yard. “Damn,” I say when mine dies not three feet in front of me. He exhales again, this time surpassing mine by yards. “Damn,” I say. He is good at this, but he has years on me.

We go back in.

“Isn’t it wonderful?” my mother says. “The whole family around the table.”

My brother is wearing new clothes. I am spooning mashed potatoes onto my plate when I ask, “When do you leave?”

“Two weeks.”

“Isn’t it wonderful?” my mother says again. “They let him have a good Thanksgiving dinner before he goes.”

The presence of Bob Dylan seems to make my brother anxious. Our dinner conversation is punctuated by his glares toward Bob, as if I have brought him here as another fuck you: Look at the friends I have made in New York City. Thankfully, Bob is oblivious, admiring each string bean on all sides before plunging it into his mouth.

Later, there is an argument. There is something my brother wants me to admit and I won’t. Bob Dylan ends up with a busted lip.

My mother wants us to sit back down and eat the turkey. She is trying to hold a bowl of corn and pull me back into my chair.

I say, “Bob, let’s get out of here.”

…

It is cold but there is sun. Bob Dylan and I drive through dead trees and I point out personal landmarks that make this Not Just Any Neighborhood. This is where I got my first kiss; this is where I worked that summer; this is where I went to school.

There’s the hospital where I was born. Small and curled like a comma, smears of mustard-colored hair, there’s the hospital where I was born. My brother was at home on the stoop, passing out candy cigarettes to the other six-year-olds.

My car rattles on an overpass. Under Bob Dylan and me sweep the arms of the turnpike. Over our left shoulders, north of the city, nothing.

“You used to be able to see the Vet from here,” I say, as if I’m narrating. “Great times had at the Vet. Years ago on opening day, a big fight broke out on the seven hundred level. The Daily News got a picture of my brother.”

A curious train runs next to my car. It ducks me, reveals to me its silver flanks through the trees, and ducks me again. It plunges farther into the crunch as I turn off. The sky is blue.

I stop at a red light on the Boulevard. A man on the median is breathing into his cupped hands. He is selling roses.

Someone in the car in front of me calls to him. It is my brother, ten years ago.

He is fighting with my mom and I am in the backseat, caught up in being eleven, ignored and ignoring. My mom’s cheeks are wet.

…

He asks how much the red ones are.

“On second thought, it doesn’t matter,” he interrupts himself and buys twelve. They are wrapped in plastic and smell like exhaust, but it ends the fight.

This happened years ago. He is a good son. My brother is a good son.

The light changes to green. I make the turn.

…

On one of the lawns facing the Little League field, an older couple is hauling leaves to the curb in a quilt that is too nice to be used in this way. Their progress is slow but they couldn’t have asked for a better day. It is cold, but there is sun lighting up my windshield, warming me at red lights. The sky is blue. The turkey is steaming on its plate.

Do they hope to clear the lawn of every leaf before the kids arrive? This is one of those unrealistic expectations parents have. That their children will be smarter than they are or will like each other, that no Thanksgiving dinner will ever be interrupted by the hard sound of someone upending a chair.

There are too many leaves. Bob Dylan and I both know: they will never get all of them cleared in time.

There are American flags on buses, on coats, on bandanas tied around the necks of Golden Retrievers. Hanging from every tree, reflected in every window.

Bob Dylan is upbeat. His lip has stopped bleeding and he wants to know, Do I consider myself to be an American Daughter?

I have been vaulted from the Thanksgiving table. What’s more American than that? How many people have left their steam-filled homes to drive around and think about old things? I pass car after car.

…

Outside the Slaughterhouse Bar, the pay phone hangs from its cord. There I am six years ago, an unimpressive fifteen. No breasts, arms and legs beyond my control, making a phone call to my brother in the middle of the night.

“Stay right there,” he says. “Don’t do anything stupid.”

I walk in place to stay warm. Every so often a car drives by and hurls its lights at me. Ten minutes later he pulls up, brakes sharply.

“I ran away and I’m never going back.” I am crying.

He waits for me to fix the long strap over my shoulder before he pulls away.

I look at him, then the road, then at him.

“Are you going to yell at me?”

“Do you know what tape this is?” he says.

I listen. There is music playing.

“No.”

“It’s The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan.”

“Oh,” I say. “What’s that?”

“Bob Dylan.”

“Right.”

We watch the road in silence.

“Are you going to take me home?”

“More people should listen to Bob Dylan,” he says.

He drives to the Red Lion diner. We sit in the big plastic seats and give the waitress our order. He buys me a bowl of French onion soup.

“I’ll take you home tomorrow,” he says. “You can stay at my place tonight.”

Then it is a new, dangerous night, one that will not end with me at my mother’s house. I give him a sloppy, generous smile. He glares at me.

A man at the counter says to the waitress, “I hear they’re talking about exploding it and putting up two new stadiums.”

The waitress seems impressed. “Yeah?”

“No,” the man says. “Not exploding. What is it when it goes in instead of out?” He makes a motion with his hands, lacing his fingers into one another over and over.

My brother smiles at me. “Imploding,” he says.

“That’s it.” The man swivels to look at us. “Imploding. They’re gonna sell tickets. Get a load of that.”

My brother takes a large bite of his cheeseburger. He puts a finger up, to signal to the man, the waitress, and me to wait. “They’ll never fucking do that,” he says, when he has the meat in his mouth under control.

The man isn’t convinced, hacks into his hand. “That’ll be a Philadelphia event. All of us tailgating to watch a stadium implode.”

My brother is certain. “No fucking way they’ll do that. This city is nothing without the Vet.”

The man shrugs. “They’ve already done it. They signed contracts and everything.”

“Who are you, the mayor?”

They both laugh. My brother’s teeth are stained with meat.

The door slams and rattles the ketchup bottles. A tall girl stands in the doorway of the diner unwinding a scarf. Then she seems to make her way toward our table.

My brother scrambles to make room for her in the booth. “I’m glad you came,” he says.

“No problem.” She sits down and is face to face with me. I don’t know where to look.

He gestures as if I am a mess on the floor. “My sister.”

“Nice to meet you. I’m Genevieve.” She pulls her scarf from her neck and I am able to see how red her hair is. It is the closest I have ever been to someone who looks like they could be famous.

“Genevieve and I work together.” My brother is having a hard time swallowing. “I have to take a leak,” he says.

When he is gone, she looks at me and I look at my soup. Her perfume smells like Vanity Fair magazine.

“I heard you ran away,” she says.

I nod.

She drags one of my brother’s French fries through a hill of ketchup. “I ran away once. I got all the way to Wanamaker’s. I got scared and called my mom.”

“Was she mad?”

“Oh boy. She was so mad, she sent my dad to come get me. He bought me a slice of pizza.”

She has impressive eyebrows. What could I say that would mean anything to her? I decide on an idea I had been toying with since the ride was over, the beginning of a line of thinking.

“You were freewheeling.” I am careful to laugh after I say it like I don’t mean it, in case she rolls her eyes.

“That’s right,” she laughs. “Like Bob Dylan.”

“Oh. Do you like him?” I say it like, Nothing much to me either way, toots.

“Are you kidding?” she says. “He’s my favorite.”

“He’s mine too,” I say. I am not lying.

“You should talk to your brother,” she tilts her pretty eyebrows toward the men’s room. “As of last week, he had barely even heard of Bob Dylan.”

I chew a piece of cheese and she arranges a stack of creamers. “Are you my brother’s girlfriend?”

When she opens her mouth, I can see all of her teeth. “You’d have to ask him,” she says.

My brother returns from the bathroom, wiping his hands on his jeans. His hair is wet.

“Let’s go,” he says. “Saturday Night Live is on.”

He lives in a crumble of an apartment next to the diner. Trucks turn in to the parking lot and light up his front room, waking up whichever one of his friends is sleeping there. We sit in his basement and he howls through the entire show. I look back at him and he wipes tears from his eyes. After it is over, he throws a pillow at me. He and Genevieve go upstairs. “Night, squirt.”

I sleep on the couch in his front room. The headlights from the trucks scan me in my sleep.

The next day, he drops me off at our mother’s house.

“Kiddo,” he calls me back to the car.

“What?”

“Don’t ever fucking do that again.”

His face is twisted. I assume with concern.

“Don’t worry about me,” I say. “You don’t have to protect me. I can take care of myself.” I throw open my arms to take on the neighborhood, the world.

He spits. “Come here.”

I lean into the car and he lays his hand on my arm, no trace of expression around his eyes or mouth.

“I mean,” he says, “don’t ever fucking do that to Mom again.”

I go inside. My mother pulls at her hair and weeps in a slow collapse against the wall of the kitchen.

…

This is my high school. This is my first play. Here are the good grades, the medals, and the prom. This is the scholarship to the private college and here is the field where, in my cap and gown, I hugged my teachers good-bye. There were no friends. My father was fifteen years dead. My brother was the man in my life.

“So long,” I tell him. “I’m going to New York City.”

This is the gas station where my brother worked until he and the owner had a “difference of opinion.” This is the hardware store where my brother worked until he told the manager to fuck himself. This is the auto parts store that gave him a job because he and the owner went to the same high school. Philadelphia is a network of my brother’s buddies. He doesn’t stay unemployed for long.

The first year I live in New York, I find a job I still have. He calls every so often to ask if I have seen any celebrities.

…

If the people at the convenience store on Bloomingdale Road are surprised to see the bloated Voice of a Generation using the candy display to scratch the low part of his back, they keep it to themselves. Bob Dylan has been looking for Tootsie Rolls for ten minutes. He’s wild over them, but they appear to be out.

I leave him to it. I am happy to be with the people on Thanksgiving, albeit the ones who do not think ahead. There is something reassuring about being among strangers on a national holiday. In the cereal aisle, the mood is decidedly last-minute.

“Can you use Corn Flakes instead of bread crumbs?” A man in slippers asks his bored-looking teenager. “I feel like you can but I don’t want Mommy yelling at us when we get home. Go ask the cashier.” The son shuffles off.

Bob is grouchy and empty-handed when he returns to me.

Seeing him, the man with the canister of Corn Flakes asks himself a question I cannot hear. Then he says to Bob, “Oh, jeez. Aren’t you Vincent Price?”

This has been a problem before. I pray Bob hasn’t heard but the man says it again, louder, as if remembering Vincent Price is deaf. He taps Bob’s shoulder a couple times and calls for his son. “Get a load of Vincent Price!” he says.

This is all Bob needs. First his lip is busted, then no Tootsie Rolls, now this. He screws his hand into a punch and lurches toward the man, who almost as an afterthought performs a delicate side step. Bob’s momentum hits the candy display and he falters, swiping at the ground with his feet. Trout-sized chocolate bars slither down his faded coat.

The teenage boy is back. “What happened, Dad?”

The man is dumbstruck, joyous. “Vincent Price just tried to punch me and he missed!”

Someone got us while we were sleeping, so this Thanksgiving is the year of the American flag. There are American flags on overpasses, on tricycles. There are American flags printed on condoms at the counter of this convenience store; America will screw you hard.

Bob Dylan mopes in the car. I feel saddled with him now. He was supposed to create some sort of lather, and he barely summoned enough energy to behead a pile of string beans. I buy him a magazine, a Liberty Bell key chain, Band-Aids shaped like pieces of bacon, and a pack of Camel reds. They are parting gifts. In line, I try to catch his eye through the window, but he is sulking and won’t look up. Bob Dylan can be a real baby.

…

My brother’s car is gone when I pull in to my mother’s driveway.