The saint, whose real name is Simon Templar, is back, in some very special adventures that will captivate his TV fans and fascinate all lovers of good mystery fiction.

Violence and murder among students, hippies and members of the “youth culture” involve. The Saint this time. An arch-black-mailer, a psychological experiment that involves students in a “murder game” that turns into the real thing these are some of the far-out ingredients in this boiling cauldron of homicidal happenings.

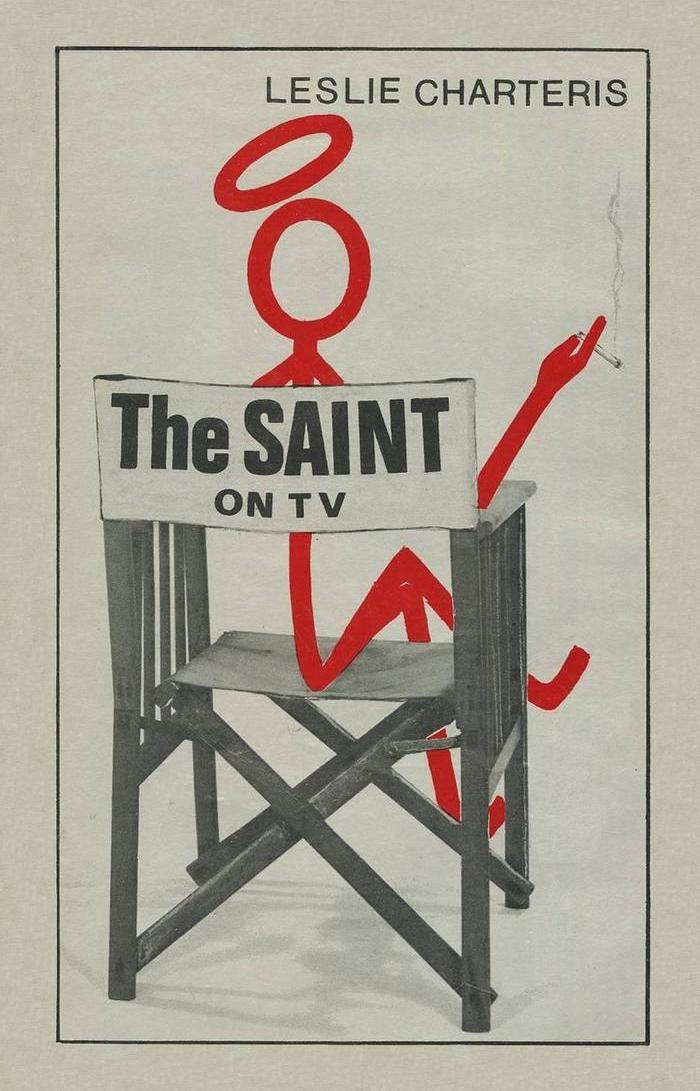

Leslie Charteris

The Saint on TV

Foreword

When, after many years of noble and lofty-minded resistance, I finally broke down and sold the Saint to the Philistines of Television, I fear that I must have added one more argument to the armory of the cynics who maintain that every man has his price, because I certainly got mine. It must have been a shattering blow to the countless millions who until then had thought I was perfect, even though I myself had never made that claim.

However, I did have enough remnants of probity to limit his period of bondage to two years, knowing full well the voracity of the mills which grind out the fodder for what I still regard as the mini-medium of mini-minds, and figuring that in that time, at the relentless pace of one show a week, they would have devoured the entire product of a not inactive writing lifetime, or anyway as much of it as was suitable for adaptation to filmlets of about 50 minutes without the commercial “messages” and the pauses for what is hilariously called “station identification.” I was resigned to the expectation that my stories would be considerably garbled and mutilated to conform either with the puerile tabus of unwritten censorships or the congenital megalomania of all movie-makers who can never resist “improving” any literary creation that falls into their power, or both; but it had never occurred to me to allow the Saint to be projected into plots that had absolutely no connection whatsoever with anything I had ever written, and in fact any such liberties were specifically prohibited in my first contract.

Despite all the distortions and emasculations which shook up a probable majority of hitherto faithful readers of the Saint books, that first TV series was a big hit in Britain (where it was made) and many European countries, and was even fairly successful in the United States although presented in most areas at such impossible hours that only chronic insomniacs, night watchmen, or veritably fanatic fans would have caught it. Indeed, the American success was remarkable enough for NBC to become interested in putting the show on their full network, in color, and in what is called “prime time” — promotion which had never before been offered to any series previously established in syndication.

The interesting situation then was that the British TV producers could not thumb out this possible plum without making a new deal with me, which would necessarily include the right to create original scripts.

Well, the cynics will recognize it as the same old story. After you’ve succumbed once, it is so much easier to succumb again. Especially when the bribe can be made so much fatter. And I have never pretended that I chose a career in writing without the most powerful mercenary motives.

So, after many hesitations and much tough bargaining, and not without very grave misgivings, I eventually consented.

The rest is history, of a sort. Many of the results, fulfilling my worst forebodings, were lamentable. But many of the so-called “adaptations” of my own cherished stories were no less lamentable, after the weird wizardries of television production got through with them. Some of those “adaptations,” in defiance of every contractual safeguard, had been almost unrecognizable anyhow. Some of the new original scripts were not much worse. Some were passable. And a few, to my pleasant surprise, were quite good.

Enter, next, three other Tempters: The Saint Magazine, which in 137 issues had just about exhausted the reservoir of Saint material, in spite of all the additions I had myself been able to make to the Saga during its existence, and my book publishers in America and Britain (to put them in alphabetical order) who had labored so stoutly for me in my rising years but had long since been bemoaning the indolence of success, and who were perpetually pleading with me to give them new Saint books which, they guaranteed, would be hungrily lapped up by hordes of starved aficionados throughout the British Empire and the United States (to put them in alphabetical order). Why not, they conjointly urged, extend the Saga to include readable versions of some of the best of the televised inventions — subject, of course, to my own final editing?

The idea was interesting, and by no means unique in literature. Even aside from the notable “Solar Pons” pastiches by August Derleth (of which several first appeared in The Saint Magazine) Sherlock Holmes himself had been perpetuated far beyond the range of Conan Doyle in several movies and innumerable radio series episodes based merely on the character and retailing episodes that Doyle never dreamed of. Barry Perowne, by arrangement with the estate of the late E. W. Hornung, continued the adventures of Raffles into modern times in a considerable number of stories (many of which were also first published in The Saint Magazine). Even while I was thinking it over, I heard that the heirs to the Ian Fleming copyrights were contemplating a continuation of the James Bond mythology — arrangements for which have since been concluded. If such a process could be tolerated by such a distinguished range of fictional characters, why should I reject it for the Saint?

If I had turned it down, there would still have been nothing I could do, so far as I know, to enjoin my own heirs from buying the same proposition some day — or, worse still, to prevent it being done without even any benefit to them by some later larcenist taking advantage of the privileged piracy sanctioned by the iniquitous concept of “public domain.” But by permitting it now, besides enjoying some of the financial fruits myself, I would have one privilege which was denied to all the other authors I have cited: I could personally watch over and to a great extent control the desecration.

These original scripts, after all, were by agreement first submitted to me as synopses, on which I was permitted to make criticisms and suggestions, even if the producers did not invariably adopt them. The resulting scripts were again submitted to me, and again subjected to my comments, even though these were not always embodied in the final films. Now I would be in a position to choose, first, the scripts which did least violence to my own concept of a Saint story. Furthermore, the story-form adaptations would be made under my own direct and absolute supervision, permitting me to change and improve on the basic material in any way I thought desirable, in a possibly unique reversal of the usual system under which the producer takes it upon himself to improve on the author. Finally, I would personally revise every page of the adaptations, making an honest effort to ensure that in style and phrase they were as fair a facsimile of my own writing as could be achieved without my doing all the work.

What you are about to read, therefore, is an interesting and perhaps unprecedented experiment in team work. It is not, in any sense, a ghosted job, because I do not pretend to be the outright author. For these first offerings (and if they are well received there will be more) I have chosen story lines by John Kruse, whom I rate as easily the best TV scripter who has worked on the show, and the novelizations are by Fleming Lee, a promising young writer who I think will presently make a name of his own. I have done the back-seat driving, and added a few typical flourishes of my own. Obviously, the composite result is not even now exactly the way it might have been if I had written it all myself. But it is as close as any imitation is ever likely to get.

—Leslie Charteris

The death game

1

“Hello, dahling,” the voice from the telephone said. “Zis is Zsa Zsa Gabor”

Simon Templar, his face freshly shaven, dark hair newly brushed, his clean shirt half buttoned, was not expecting a call from Zsa Zsa Gabor. He did not know Zsa Zsa Gabor, and he had no reason to believe that the actress with the often mimicked voice was any better acquainted with him.

“I’m sorry,” he said with hesitation. “I’m afraid you have the wrong number. This is Captain Kidd.”

While his formerly gushing caller hesitated, experiencing the disconcerting vertigo of rapidly turning tables, Simon admired his own psyche’s impromptu choice of a pseudonym: it was fairly appropriate for a man who had often been called — among more censorable things — the twentieth century’s brightest buccaneer. Most assuredly, had Simon Templar’s rakishly piratical face been exposed to the world three or four hundred years sooner, it would have been found on the poop of some white-winged marauder. As it was, his present day forays against the gold and jewel laden galleons of the Ungodly had brought him at least as much fame and perhaps even more fortune than in earlier tunes when heroism and daring were more common and less denigrated qualities on the face of the earth.

“You are kidding wiz me, dahling,” said the alleged embodiment of all things good in bed. “You are ze man zey call ze Saint.”

“That’s also a possibility,” said the Saint. “Now if you’ll tell me who you are we’ll be almost even.”

“I’ve told you, you funny man.” Her voice took on a sudden urgency. “But I have no time to argue any more. I am in trouble and I...”

“Perhaps,” Simon interrupted helpfully, “you’d better speak to your family doctor.”

It was impossible to tell definitely whether his caller snickered or suppressed a sigh of exasperation. At any rate she went on a moment later in the same desperate tone.

“I am told zat you are ze only one who can help me. Please, it is most important. I must see you. If you will meet me at...”

Simon, as she went on unnecessarily detailing a route by which he could arrive at a certain street corner not far from the British Museum, glanced at his watch and then out the window of his bedroom. Though it was only six in the evening, a heavy fog enveloped the autumn streets of London, and it was almost as dark as it would be at midnight.

“Listen,” he said, having no intention of refusing to accept the gauntlet which was being so charmingly flung at him, “I’m dressing for dinner now, and it just happens that I have no engagements for this evening. Why don’t you meet me at the White House at seven and...”

“White House?”

“It’s a restaurant, darling. No relation to the Birds’ Nest in Washington. Meet me there at seven and we can discuss your difficulties over the most delicious...”

“I couldn’t It... it must be later, and...”

“Then how about here at my house when it suits you? You know where I am, no doubt, since you have my number.”

“Yes, I think so. Upper Berkeley Mews. But...”

“And a charming spot it is, too,” Simon said nostalgically. “I lived here years ago and just found that the old place was available again. And I can’t think of a better partner for a housewarming than you.”

His Zsa Zsa or pseudo-Zsa Zsa was beginning to sound pressed.

“No,” she said. “It’s impossible. I beg you. Meet me where I said. At ten o’clock. Please.”

Whatever nefarious intentions she or someone she represented might have, her insistence on choosing her own ground assumed a naivete on Simon’s part which implied an almost unbelievable naivete on hers. Still, there was one inducement to go along with the proposal: if someone was out to ensnare him in some way, the Saint would not have chosen the venue but he would know where and when to be on guard — which advantage was several cuts above not being fore-warned at all.

“If you insist,” he said pleasantly. “But it’s only fair to tell you that I don’t believe for a moment that you are Zsa Zsa Gabor I’m just curious enough to want to know what the gag is — and it’d better be good, or you may find yourself getting spanked.”

“Oh, zank you for coming. It will be worth your while.”

“I’m sure it’s intended to be worth someone’s while — but just whose is the question that fascinates me.”

The fascination stayed with him as he finished dressing, cast a fond glance over the walls and refurbishings of his old haunt, and piloted his car off into the mist. It added a special piquancy to a meal which was as relaxed and fine as he had anticipated, but which without the earlier phone call would have turned his thoughts more toward relaxation and eventual sleep than toward the expectation of excitement. The voice, even if spurious, had had a timbre of genuine sexiness which he recognized in the same way that a connoisseur recognizes the scent of a good wine; and it was an article of his faith that adventure never came to those who sat at home in fear of making a mistake.

A little before ten he drove to the appointed area and circled through the almost deserted streets, always keeping a block’s distance between himself and the corner his Zsa Zsa had mentioned. He saw nothing to change his mind about keeping the date. Then he zigzagged deviously through several blocks to confuse any possible observers, and parked a full five minutes’ long-striding walk from his destination. He did not think, under the peculiar circumstances, that there was any taint of paranoia in his desire to arrive in as discreet a way as he could.

Of course it was possible — just barely possible — that the much photographed form of Miss Gabor would come drifting toward him out of the dampness like a Magyar mermaid. She had been reported in London, and only the day before he had read one of the usual idiotic newspaper interviews with her. That could also have inspired a joker whose calendar had stuck at the first of April to use her name for a stupid hoax, even more probably than that the real Zsa Zsa would have had any reason or inclination to call him. But stranger things than that had happened in his incredible life, and he could never have slept peacefully again if he had not given this one at least a sporting chance to surprise him. And yet at the same time, even while logical skepticism was resignedly prepared for a pointless jape, the conditioned reflexes of a lifetime still found themselves tautening to respond to anything more sinister than either of those simple alternatives. As he was about to emerge from an alley half a block from the trysting spot, he stopped and listened. The neighborhood, composed of small shops all closed in the evening, seemed absolutely deserted, and the more distant sounds of the city were muffled by mist. He looked along the street, both ways. Visibility was held down to barely a block, but it was obvious that within that area, at least, there was no one waiting for him.

He moved around the corner, out of the narrow passage, and went along the sidewalk. Then, almost like an echo of the sound of his own shoes on the dimly gleaming pavement, he heard the other steps. He went quickly around the comer of the block, where he was supposed to meet Zsa Zsa, and stood still to listen. The footsteps continued, drawing closer, from the direction of the alley he had just vacated.

As he heard them, swiftly analyzed their character, compared them with footsteps in general, the Saint felt the hairs prickle icily on the back of his neck. For the footsteps were not those of a woman — nor of a man either. Certainly of no animal. With mechanical steadiness they came on, accompanied now by a faint whining sound like that begun by a cuckoo clock just before the bird pops out to announce the hour.

Simon looked, and the unknown — which had aroused such aboriginal stirrings of his body fur — became the ridiculously familiar.

A metal toy soldier about twelve inches in height was marching along the sidewalk, its tin rifle on its shoulder, its wide painted eyes staring sightlessly straight ahead.

The Saint, feeling it safe to assume that the clockwork man has not happened along at just that moment by sheer accident, watched its progress as it passed him by and walked straight off the curb, falling on its face in the gutter. From that unmilitary position it continued its stiff movements, going nowhere, until finally, with some sporadic dying ticks, it lay still and totally silent.

Only after that did Simon venture a close approach to the thing. He rolled it over with his foot, then knelt to pick it up. For a second or two after he took it into his hands, searching it for a sign of its purpose — it seemed more the vehicle for a joke than for anything serious — nothing happened. Then it almost soundlessly emitted, from the barrel of its rifle, a single puff of black smoke.

The Saint flung it away from him and backed off, covering his mouth and nose with his handkerchief. But even though a little of the smoke had found its way into his nostrils he was suffering no ill effects beyond a mild and easily satisfied urge to sneeze.

The next event, however, was less harmless. There was a swift hiss over his head, and he turned to see an arrow, shaft fractured by its impact with the brick side of the building, clatter to the sidewalk at his feet.

The angle of the arrow’s flight told him the approximate place of its source and at the same time the location where he would be most safe. Out in the open, taking pot shots into the fog, he might very well receive, during the next few seconds, an unwelcome steel-tipped addition to his already quite adequately equipped anatomy.

In three strides he achieved the shelter of the nearest doorway and waited, automatic in hand, for some further charming manifestation from his rendezvous. It was not long in coming. A car barely poked its nose around the next corner, a red MG convertible with the top up, and from its blacked-out interior came a quick drum-roll of faint popping noises that matched the closer thudding of lead slugs pocking the brickwork on either side of the entranceway.

Flattening himself as deep into the alcove as possible while he was trying to decide where he could aim back most effectively against an invisible sniper with some kind of silenced automatic rifle who had to be in the rear part of the MG that was still mostly shielded by the corner building, Simon felt the door that he had his back to yield slackly to his pressure. His change of purpose was faster than thought; he was outgunned, and he knew it, and anything was better than his present exposed position. In a flash he was inside, slamming the door behind him.

The shooting stopped. There was no further sound.

The Saint took advantage of the lull and his new temporary security to survey what he could of his surroundings. His pocket flashlight, combined with the glow of streetlamps filtered through the transom from outside, showed that he was in the entrance hall of an obviously vacant building. Ahead of him was a staircase whose landing had been appropriated by spiders. The target shapes of their webs, stretching from bannister to wall, had an unpleasant association for him: he did not like being a target himself, a tin duck in somebody’s shooting gallery — especially a somebody who was probably insane as well as an incompetent marksman.

There was a closed door near the base of the stairs, facing the street entrance, and on the right was an open door, leading into a room which had to overlook the street. Since the Saint did not want to signal his position with the beam of his torch, he put it back into his pocket before leaving the hall.

The front room showed even more signs of decrepitude and neglect than had the staircase. Its only furnishings, aside from the marbleized bowl which covered its ceiling bulb, were a sagging table and a three-legged chair. The naked windows gave a full view of the street, but Simon could not see the MG, or any other assailant. The toy soldier lay dented where it had fallen in line of duty. Fog veiled everything else.

Then Simon’s fantastic reactions, in the blinding fragment of time which followed, sent him to his knees by the wall even before his conscious mind had been able to register what was happening. Only then did he realize that the overhead light in the center of the room had flashed on, though no one stood by the wall switch. Immediately afterward there had been a sound like that of a firecracker exploding.

Now, down from the light fixture drifted a long black rectangle of silk, attached at the top to the marbleized bowl, unfurling to its full length of a yard or more, so that its vivid scarlet lettering became perfectly legible.

BOOM, it said.

Simon, preferring invisibility to the continued opportunity of admiring the artful banner, shot out the light. He did not even care if the report of his gun brought Chief Inspector Claud Teal himself scurrying over from Scotland Yard. Indeed for once he might have welcomed Inspector Teal’s presence, if for no other reason than to have an independent witness corroborate the nightmarish ballet macabre in which he had been caught up.

A click and a humming noise came from the part of the room where the chair lay near the rickety table. Then a muffled voice began speaking.

“You have been gassed by a toy soldier, been shot through the head with an arrow, been mowed down with a submachine gun, and been blown up by a plastic bomb hidden in a light fixture. This is your killer speaking. You, the once famous Mr Simon Templar, are dead.”

Another click signaled the end of what was obviously a recording, and the Saint, feeling unamused but somewhat more at ease, decided that he was simply the victim of one of the most extreme practical jokes ever perpetrated. That realization, however, did not diminish by one erg his earnest desire to discover the identity of his persecutor. Using his pocket light again, he went to the table, opened the drawer, and looked in at a small battery-operated tape recorder which by means of some clever Japanese mechanism had turned itself on and then turned itself off again.

He closed the drawer. The recorder might carry fingerprints, or the comedian might come back to get it. And then Simon realized that there might be no need on his part for the tracing of identities or the setting of traps: a most faint sound had just reached his ears — a sound which, if noted at all by an ordinary man, would have been passed off as the inevitable creaking of antique lumber. But if the Saint had not possessed senses discriminating enough to prevent him from assuming such things, he would never have survived so long to enjoy the material rewards of his adventures.

What he was hearing, after the creak, was the stealthy approach of stockinged feet from behind him. Either his assailant had not been content with four types of mayhem and was about to attempt to add a fifth, or some new character was taking the stage.

The Saint waited for him, his back turned as bait, reasonably certain that any violent move would be presaged by a warning noise beyond that of foot-filled woolen material padding on old boards. Besides, any really serious killer would not have passed up his chance with a goodly proportion of the weapons in the human arsenal only to engage Simon Templar, of all people, in face-to-face combat.

So the Saint waited those few breathless seconds — breathless at least on the part of the stalking individual behind him. Simon’s lungs continued operating at the same easy pace they would have kept during the annual radio reading of Dickens’ Christmas Carol. And then, when the moment was exactly right, and he could somehow feel the presence of another body at just the proper position, he moved.

For the stalker turned victim, it must have been an astonishing sensation. At one moment his cautious feet were on the floor; an instant later he was in the air, experiencing the delightful but short-lived astronautical sensation of weightlessness without any effort at all on his part; and then he was forcibly reminded of the persistence of those natural laws which make apples fall and keep pigs out of the paths of soaring hawks. Then he knew nothing. He was flat on his back, unconscious.

Simon, using his pocket torch, found only one thing surprising about his sleeping adversary: the man was scarcely a man. He could not have been much over twenty — thin, brown-haired, neatly dressed in turtle-neck sweater and slacks, with a kind of intelligence in the molding of his face which one would not expect to find in the countenance of any ordinary young back-alley bandit.

He was carrying a single weapon: a string necktie, one of whose ends was still wrapped around his left hand. With that, in traditional commando fashion, he had apparently intended to throttle the Saint — or to pretend to throttle him, if his use of the strangling cord was to conform with the mock attacks that had already taken place.

Out in the hall, from the vicinity of the base of the stairs, a door opened. This time there was no attempt at silence. The door not only opened quite noisily, but was kicked back against the wall, and the footsteps which followed were completely uninhibited.

The hall bulb was flicked on, flooding the larger room with light, but by that time the Saint had already flattened himself against the wall just inside the door. He was ready for almost anything except what happened.

A very pretty young blonde walked in, carrying a tray on which were arranged a tea pot, three cups, a pitcher of milk, and a bowl of sugar. On the young lady herself were arranged, with much greater effectiveness, a very tight little sweater, a very short little skirt, and a pair of fashionable white boots. As she entered and saw the prone figure on the floor just beginning to groan and stir, she stopped and said to him in the mildly exasperated tone of a housewife whose husband has just failed to bring the swatter down directly on the fly, “Oh, Grey, you didn’t get him!”

2

Simon, who had planned a startling and entirely physical greeting for the newcomer before he got a look at her, decided that even without her hands full of tea things she would have posed about as much threat to him as a gladiola bulb.

“For heaven’s sake, don’t drop it,” he said softly.

The girl gasped, turned quickly, but did not drop the tray, even when she saw Simon’s automatic aimed at her middle.

“Oh, Mr. Templar, you frightened me.”

“And that’s only the beginning. Why don’t you set that stuff on the table over there and put your hands very high over your head until I can check over your few available hiding places for knives, bombs, and mustard gas grenades.”

The girl giggled as she freed her hands of the tray and raised them over her head.

“But I’m not even playing,” she said.

“Neither am I,” said Simon. “I hope you’re not going to be mad at us.”

“That’s the chance you have to take when you ambush people,” the Saint replied. “Now I shall shoot both of you and be on my way.”

The girl’s ingenuous green eyes became a little rounder.

“Wouldn’t it be awful,” she said, “if you took this seriously and really did kill us?”

“Oh, I am going to kill you,” Simon said casually. “The only thing that’s stopping me is a question of etiquette. Does the old business about ladies going first apply when one’s performing an execution?”

The girl blinked, and her high spirits were visibly lowered. Her accomplice was sitting up on the floor now, rubbing his face with both hands in an apparent effort to restore the clarity of his eyesight.

“Grey,” the girl said tentatively. “Grey? I think he’s angry at us. Why must you always overdo things?”

The young man managed to focus his eyes on the Saint.

“I’m Grey Wyler,” he said, pushing strands of hair out of his face, “and this is Jenny Turner.”

Simon nodded, and the little imps of humor which had beat a temporary retreat reappeared in the clear blue of his eyes.

“It’s safe to say the pleasure is all yours,” he remarked. “But curiosity may move me to spare your lives if you’ll tell me what this is all about.”

“We’re psychology students,” Grey Wyler began.

“At the bottom of the class, no doubt,” said Simon.

Wyler did not seem to share any of the light-heartedness of his female companion. His whole manner reflected an inner tension, and there was an unrelieved seriousness in the tone of every word he spoke which made the Saint feel an instinctive distrust and antagonism. The humorlessness showed the kind of lack of perspective which so easily verges over into insanity — and certainly nothing which had happened during the evening so far gave him any assurance as to the mental stability of his playmates.

“This is what’s called the Death Game,” Wyler went on. “It’s a hunters and victims kind of thing. Nobody really gets hurt, of course, but...”

“May I put my hands down?” Jenny interrupted.

“First step over this way and let’s see what sort of armaments you’re packing,” Simon said.

Jenny obeyed, keeping her arms up while the Saint checked over her from neck to knees with a gentle but not-entirely discreet hand.

“Oh, Mr Templar,” she murmured. “It’s such a thrill meeting you in person.”

“Same to you, Zsa Zsa. You can put your hands down now.”

The girl laughed.

“How’d you know it was me?”

“It took some very high class reasoning — the first step of which is that your boyfriend’s voice is about an octave and a half too low for the job.”

Jenny looked at him admiringly.

“You’re funny, too,” she said, “and better looking in person than your pictures. Don’t you think he’s better looking than his pictures, Grey?”

Wyler made a noncommittal noise and got to his feet.

“How about pouring us some tea before it gets cold?” he said. “Mr Templar?”

“No, thank you. My nine lives have just about been used up tonight, and I can’t afford the chance of drawing a tea bag with a skull and crossbones on it.”

“Game’s over,” Jenny said, serving. “No more killing tonight. Sorry you have to stand up, but this place belongs to my Dad and he’s trying to sell it. At least the kitchen was still in working order.”

Simon allowed himself to be talked into taking a cup.

“Now,” he said, “what is this Death Game?”

“It’s a bit kinky, but terribly in,” said Jenny. “Grey gets slightly carried away — he does with everything — but most people take it as a joke. Milk?”

“Please.”

Grey Wyler took over the explanation.

“The players are divided into hunters and victims.”

“They doing it in universities all over the place,” Jenny interrupted.

Wyler looked at her with cold irritation.

“If you’ll let me tell it.”

Jenny shrugged and moved to stand nearer Simon, watching him with an intensity that bordered on worshipfulness.

“Sometimes the hunters and victims are paired by lot,” Wyler said. “In our department at the college here we use a computer. There’s an instructor, Bill Bast, who works the game in as part of the educational process. Dr Manders, our department head, encourages it too.”

Wyler had pronounced the words “educational process” with a subtle sarcastic sneer which the Saint soon realized was one of his most persistent mannerisms. It was the boy’s way of making it clear that in his vast superiority he could not risk being identified with or associated with anything on the common earthly plane. Someday, Simon thought, he would fit in very well as a professor.

“At any rate,” Wyler continued, “the hunters are told who their victims are, and the victims are told only that they are on somebody’s death list. Whose, of course, they don’t know. Then the hunter proceeds to try to ‘kill’ his assigned victim in the most ingenious way possible.”

“And as many times as possible, apparently,” the Saint said. “Tonight’s the first I’ve ever seen mass murder performed on one man — assuming your attempts on me would have worked if you’d been serious.”

Wyler again demonstrated his lack of humor by narrowing his eyes and looking almost venomously indignant.

“You deny that I could have succeeded?”

Simon studied the boy for a few seconds and decided that an argument over hypothetical murder was not worth his own time.

“I’ll let you be the judge of that,” he said.

“It’s the scoring Grey’s worried about,” Jenny explained. “Just killing somebody won’t get you much. Like if you shoot him in the back or something while he’s getting out of his car it’s only worth a couple of points.”

“But something like the toy soldier with the poison gas,” Wyler put in, “would be worth four or five.”

“On the other hand,” Jenny said, “if you kill an innocent bystander you get docked three points.”

“The first person to accumulate ten points is named a decathlon winner,” said Wyler.

“And gets a prize,” added Jenny.

Simon gazed at her with fascination.

“It beats tiddlywinks,” he conceded finally.

“Groovy, isn’t it?” Jenny bubbled. “We’re all just absolutely wild about it.”

“Meaning that the whole student body is buzzing with homicidal ingenuity?” Simon asked.

“That’s about it,” Wyler answered.

“And just how did I get involved?” the Saint asked.

“My psychology advisor, Bill Bast, bet me ten pounds I couldn’t kill the great Simon Templar,” Grey said. “Frankly, I thought it would be much more difficult.”

It took some unusual adherence to the qualities implicit in his nickname for the Saint to avoid an overt demonstration of his feelings about Grey’s puppy haughtiness.

“Assuming, since it’s only a game, that you did kill me tonight,” he said, “I have to remind you that you weren’t playing fair.”

“In what way?”

“You didn’t notify me that I was a victim.”

Grey Wyler tensed.

“The circumstances were... It wasn’t practical. Bast knew I couldn’t let you know. It was part of the bet. We assumed that someone like you would always be on his guard.”

“They were afraid you wouldn’t go along with it,” Jenny said. “And besides, old Maunders would’ve hit the ceiling if he’d known they were going after somebody outside the university. I almost think he takes this more seriously than the students do.”

“Old Maunders being some recalcitrant bulwark of professorial tradition?” Simon asked.

“Exactly,” Wyler said. “But you’ll meet him in a few minutes. Now that I’ve won I don’t give a damn what he knows or thinks.”

“I’ll meet him?”

“At the party,” Jenny said. “End of the term — and the Death Game winners get prizes and everything.”

“Having passed the age for student pranks,” Simon said, “and having been killed several times over, I think I’ll just retire to my cozy den and try to summon up forgiveness for those who lured me out of it in the first place.”

His refusal instantly brought from Jenny some of the most ingenuous persuasion to which he’d ever had the pleasure of being subjected. First she gave a little squeal of dismay, and then she flung both her arms around one of his arms, pressing herself against him and fairly jumping up and down.

“Oh, you just can’t disappoint us! I told everybody you were coming — and you’re supposed to pass out the prizes, and everything, and if...”

“The Death Game prizes?” Simon asked, intrigued at the prospect of getting to know more about this college fad that was so much like the game he had played, for real life and death stakes, during most of his existence.

“Oh, yes,” Jenny exclaimed, seeing her opening. “And the winners tell about their kills. You’ll love it. You’ve been such a great sport so far. Just string along a little longer, won’t you, please?”

“Jenny,” he said, “you’re more than I can resist. I’m yours to command.”

Jenny’s car was parked a block from the building where Simon had met his imaginary doom. It was, of course, the red MG from which the shots had been fired. They all squeezed in, as far as the place where Simon had left his own car, and then he followed them out of the deserted neighborhood of shops to the university district half a mile away. The college, forced to expand in the heart of a crowded city, had done so by occupying already existent structures in the area surrounding its original core. The only things distinguishing the academic buildings from nearby apartment houses, book dealers, and purveyors of technical supplies were modest identifying plaques beside each entrance door.

The MG stopped in front of a building labeled PSYCHOLOGY AND SOCIOLOGY. It was dark except for a single row of lighted windows on the ground floor.

“Party’s not here,” Jenny called as Simon left his car and joined her and Wyler, “but Bill Bast is. We’ll run in and see him first, then go over to the club.”

“Looks practically deserted around here,” the Saint commented as they went through the door and entered a corridor smelling strongly of age and floor wax and mildly of unidentifiable chemicals.

“End of term,” Jenny explained. “Most people have left. In fact just the ones who really took an interest in the Death Game are still here. They aren’t all in psychology, of course. Here we are.”

She opened the door to the very large, long room whose windows had helped to illuminate the street outside. Two rectangular tables surrounded by chairs ran down the center. Along the walls were a number of smaller tables, some desks, built-in storage cabinets, and cages of drowsy mice. At the far end was a computer, and beside it a tall almost skinny man of thirty or so wearing a white laboratory smock over his street clothes. The care he did not lavish on the crease of his trousers or the shine of his shoes was apparently devoted to experimental work.

“We got him!” Jenny called as she took a proprietary grip on Simon’s arm and led him between the tables. “This is Bill Bast, our assistant lecturer in psychology. Of course he knows who you are.”

Bast turned from the computer, smiling, and offering the Saint his hand.

“It’s a privilege to meet you,” he said. “I’ve been looking forward to this very much.”

Wyler did not contribute to the general good-feeling.

“You owe me ten pounds,” he said in a flat tone that emphasized his arrogance. “It was at least a five point killing, and every step went just as I planned.”

Bast’s acknowledging glance at Grey was not marked by affection.

“Congratulations,” he said coolly, digging into his pocket for a pair of notes which Wyler took without thanks.

“It was nothing,” he said.

Bill Bast turned again to the Saint.

“I take it Grey and Jenny have filled you in on the Death Game?”

Simon nodded.

“It sounds like good clean fun.”

“We think it may have a real psychological value, too,” Bast said. “Just a second, I’ll cut off the computer and we can talk.”

“This machine is what pairs hunters and victims?” Simon asked.

“That’s only a sideline for it,” Bast replied. “It’s used primarily for much more important things — all kinds of data-comparing functions.”

“As a matter of fact,” Jenny said, “I’m surprised old Manders lets us use it for the game at all.”

“Dr. Manders is the head of the Psychology Department,” Bast explained, and it was immediately obvious that a subject had been broached which was disturbing to him.

“He’s a good man,” Jenny said. “Not many of these scholarly types would go along with something like this. I think he’d like to pitch right in himself if it wasn’t beneath his dignity.”

Bast seemed to feel increasingly uncomfortable as the discussion of his superior went on.

“Shouldn’t you kids be getting on over to the party?” he asked, looking at his watch.

“Right,” Jenny said. “I promised to help touch up the decorations. Will you bring Mr Templar? Don’t be late, though. Prize giving’s at midnight sharp.”

“What other time could it be?” Simon said.

“You’re absolutely groovy. It’s right around the corner — basement of the University Club, and...”

“I’ll see that he makes it,” Bast assured her, recovering enough of his former good mood to laugh and shake his head as she and Grey went out.

“Quite a girl,” Simon remarked. “Does she ever slow down?”

“Never. But Mr Templar, there’s something I must talk to you about,”

Simon did not miss Bast’s sudden reversion to an apprehensive tone.

“Yes?”

“In fact, I have to admit that wanting to involve you in this — to give myself an opportunity of talking with you — was one of my motives in making the bet with Grey Wyler.”

“It does seem a little touchy, attacking strangers on the streets, even in fun. They might fight back — with real bullets. Or lawsuits.”

“I know. You were the first one. Outside the college, I mean.”

The Saint was growing a little impatient with Bast’s reluctance to get to the point.

“Well,” he said, glancing at his watch, “just what is it that’s bothering you?”

Bill Bast hesitated once more and finally got it out.

“I’m afraid that the Death Game... is becoming something more than a game.”

3

But that was as much enlightenment as the Saint was to receive just then on the subject of Bill Bast’s worries. The unannounced entrance of a third party cut off his words as abruptly as if a guillotine had cut off his head. Simon himself was almost startled by the entrance, which was so entirely unheralded that there was something suspect about it. The sound of a walking man should have been audible for some distance through the almost deserted building, and yet there had been no sound at all until the door opened and a short, round-headed, balding man stepped in, his middle-aged portly frame invested with more dignity than it probably deserved by the black folds of an academic gown. He spoke with what might have been either ungraceful surprise or ill-concealed irritation.

“Ah, Bast... not at the party?”

“Dr. Maunders,” Bast said. “We weren’t expecting you here.”

“I trust not.”

“This is Mr Templar. Mr Templar, this is Dr Maunders, head of the Psychology Department.”

Dr Maunders gathered enough aplomb to grant Simon a soggy handshake and a limp rendition of a smile. Even those improvements, however, failed to put him anywhere near the category of people whom the Saint found charming at first sight. The only things intriguing about Dr Maunders — who otherwise seemed as spiritually weak as his handshake and as characterless as the bald expanse of his forehead — were his unhappy effect on Bill Bast and his peculiar ability to approach doors without making any noise.

“How do you do?” said Simon, realizing even as he spoke that certain groups of synapses were meshing beneath Dr Maunders’ hairless cranium, bringing cloudy recognition to the Grey lenses of his eyes.

“Could it be Simon Templar, the Saint, by any chance?” he asked.

Simon nodded.

“I confess. My halo’s in need of some repairs, though, after my contact with your students.” Maunders looked puzzled.

“I didn’t know you were acquainted with any of them.” He put down the book he had been carrying when he entered, at the same time trying to suppress the annoyance which had crept again into his face. “But of course there’s no reason for me to know the details of my students’ and associates’ private lives.”

“Mr Templar was brought into the Death Game,” Bast said, reminding Simon of a ludicrously overgrown George Washington confronting his father beside the cherry tree. “By Grey Wyler.”

Maunders’ irritation broke the surface entirely.

“Wyler? Brought in a non-student? There could be serious trouble from something like that. I really must say...”

“He had my permission,” Bast said.

Possibly it was a well-formed habit of coming to the rescue which prompted Simon to interpose himself.

“Not that he’d need anyone’s permission necessarily,” he put in. “I assume that what students do with their time outside the college is their own business. I can’t say I was delighted to have my hair parted by your prize pupil’s arrow, but I wouldn’t hold anyone responsible but Wyler himself.”

Whatever gratitude the Saint’s intervention earned from Bill Bast was more than balanced by the obvious hostility he seemed to provoke in Dr Maunders.

“I’m pleased that you take such a broadminded view,” said the professor acidly. “On the other side of the situation, however, is the fact that the Death Game is so closely associated with my department here at the university that any public unpleasantness that grew out of it would reflect very seriously on me.”

Bast was holding himself in a state of controlled rigidity. His tone was stiffly correct but not obsequious.

“I didn’t expect you’d be quite so upset. Now that it’s done there’s nothing I can say except that it won’t happen again, as far as I have any control over it.”

“There’s no harm done,” Simon said. “And the fad will probably pass after a few more weeks anyway. Why don’t we just forget it and go see how the new generation enjoys itself in between mock murders?”

Bast looked at his watch and began pulling off his laboratory smock.

“You’re right. We should be getting along.” He paused and then gave Dr Maunders’ sensitivity another inevitable tweak. “They’ve asked Mr Templar to give out the prizes.”

Manders turned away abruptly to busy himself with some charts on a nearby table.

“Oh, really?”

“You don’t mind, I hope?”

“I assumed... It doesn’t matter.”

“Dr Manders,” Simon said, “if I’m interfering with any plans of yours I’d be more than willing to withdraw.”

Manders looked up pettishly from his charts and performed another of his flaccid smiles, making only too clear the effort it cost him.

“Not at all, Mr Templar; the students will be thrilled to have such a... celebrity at their bash. Go right ahead, please. I’ll join you there in a few minutes.”

“Pleasant chap,” Simon remarked when he and Bast had left the laboratory. “Sort that makes you love the human race.”

Bast, his gangling stride emphasizing his eagerness to get away from the awkwardness they had just experienced, shook his head.

“He wasn’t always like that. A year ago he was a different man. Jolly almost. Then...”

“Hullo there, Mr Bast! They’re waiting.”

Two young men had appeared from around the corner as Bast and Simon came out onto the sidewalk, evidently a search party from the student assemblage, and any more private conversation was impossible.

A couple of blocks’ walk through the clammy mist brought them to a large brick building whose staid facade bore the modest legend, lettered on a small wooden plaque, THE UNIVERSITY CLUB.

The basement of the Club — or at least that one moderately sized room of it which had been commandeered for the night’s social affair — was anything but staid. Jammed with thirty or forty students from wall to wall, unlighted except for candles, it gave the immediate impression of a tin of anchovies viewed from the inside. On closer inspection, it became apparent that the students were sharing the confined space with a half dozen round tables covered with red and white checkered tablecloths, with a mercifully silent juke box, with a small dais near the door, and with a striking assortment of strange or macabre decorations: strings of onions with black ribbon bows on them, skull and crossbone pennants, ketchup-stained rubber daggers, and hangmen’s nooses.

Simon could not inventory much more in the general turmoil, before Jenny Turner came shoving through the crowd, waving and shouting to him.

“Oh, Simon, I’m so glad to see you. What about the old Death Game motif? Great, huh? I did almost all of it.”

Simon was amused to find that she had already put him on a first name basis, but of all the young women he’d seen for some time he could not think of any to whom he would have been more willing to permit such familiarity. In fact, what Jenny Turner’s lushly curved shape did for her short skirt and sweater would have guaranteed a desire for intimacy in any even semi-sentient male.

“It’s lovely,” said the Saint. “Are these spiders on the tables hors d’oeuvres or guests?”

She laughed.

“I made them out of dyed pipe cleaners.”

Bast was opening a pack of cigarettes preparatory to further enriching the already dense atmosphere of the cellar.

“A highly developed originality quotient has our Jenny.”

“Among other things,” Simon said appreciatively.

If he expected a maidenly blush and lowered eyelids he had for once miscalculated. The girl gave him a bold gaze, and the half-smile that lingered on her lips took on a tinge of expectancy and invitation. Far from turning shyly aside, she drew her shoulders further back as if to make it impudently clear that she knew quite well what he was referring to.

“It’s almost eleven,” Bill Bast said. “If we don’t want a riot on our hands we’d better get on with the prize giving.”

As the young lecturer led the way to the dais, Jenny leaned towards Simon.

“Where’s Dr Manders?”

“Sulking in his tent,” said the Saint in a low voice. “I’m afraid he’s not only upset about you people attacking strangers on the streets, but also because you’ve giving me the spot he should have had.”

“He’s acting like an old sourpuss. Who cares? Come on.”

She took his hand and led nun to Bill Bast’s side as the din of chattering and laughing died away.

“Tonight,” Bast said, “we’re very fortunate to have with us a gentleman who — if even half the legends about him are true — has been through much more in reality than we’ve ever dreamed of in our Death Game.”

The speaker went on in the same vein for several minutes, working in some humorous comments about the game in general. Dr Manders came into the basement, avoided meeting Simon’s eyes, and took up a station next to the wall on the other side of the room, sucking his cold pipe as if it were his thumb. Jenny, who had seen fit not to relinquish her warm grasp on Simon’s hand, squeezed his fingers and looked up at him with something uncomfortably close to adoration as Bast concluded his remarks.

“Now,” he said, “I’m very pleased to introduce Mr Simon Templar, who will give out the prizes for the three highest scores in the Death Game.”

Bast started to step aside as applause filled the low ceilinged room, but then he had an afterthought.

“And let’s hope this too shall pass, and in the next term we can stop dreaming up ways to kill one another and get back to our white mice and mazes.”

He said it without a smile, and Simon thought it doubtful that many of the students even heard him, since most had begun clapping enthusiastically to welcome the Saint. But it probably did not matter to Bast whether they heard him or not. He had addressed himself directly to the sullen Dr Manders.

Simon was given a piece of paper with the citations on it, and Bast briefly explained the procedure to him. Then it was his turn to take the stand.

“As one whose bones tend to creak with boredom at the mere thought of anyone lecturing me on any subject whatever for a period of more than three and a half minutes,” he said, “I’m going to spare you all the funny cracks and solemn thoughts and get on with the prizes. I’ll just say that it’s quite a novel experience to be here — even though my invitation did arrive on the nose of a bullet — and that I truly appreciate this unique opportunity to see how the world’s leaders of tomorrow are spending their time today.”

There was laughter and more applause. Simon looked at his script by the light of a candle which Jenny held for him.

“Now for the Death Game first prize. Will Alastair Davidson stand, please? He’s one of the dead ones.”

A tall, blond, sheepish-looking boy raised himself halfway from his chair, grinned, and sat back down.

“Mr Davidson’s hunter was the winner of the prize for the highest accumulated score. And I must say that after my experience with him this evening I can testify to his homicidal skills: Grey Wyler.”

As Wyler got to his feet with a lazy, contemptuous nod, it was apparent that the applause he was receiving was not really what he would have expected for a first-prize winner. And to anyone who had spent ten seconds in Grey’s arrogantly chilly presence the reason for the lack of popular enthusiasm would also have been predictable.

“We’ll ask the champion to describe his prize-winning murder for us,” Simon said.

“Rather simple, actually,” Wyler said, letting it be known with his expression and tone that he found the whole business of public acclaim slightly boring. “Alastair has ambitions to be a writer.”

Alastair squirmed as Wyler paused to let his unspoken but completely obvious evaluation of his victim’s literary potential impress itself on the group. Then Wyler continued.

“I knew he had an electric typewriter and that he spent a couple of hours every night writing his fictional productions. I wired the typewriter space bar to a pen light concealed under the machine. As soon as Alastair started to type the pen light turned on. But it wasn’t a pen light. It was a laser beam. In two seconds it had burned through his vital organs to his spine, rendering him quite dead... and depriving the world, I’m sure, of a quantity of artistic outpourings second only to the works of Tobias Smollett.”

Grey sat down amid grudging chuckles and a new round of applause.

“Congratulations,” the Saint said dryly. “It seems you won’t get your prize until the other announcements have been made.” He looked at his paper and then out over the crowd. “Would Eleanor Knight please stand?”

In the dim light Eleanor Knight was not much more than a plump ghost with long dark hair and an apologetic smile.

“She doesn’t look dead,” Simon said gallantly, “but according to these notes she is. And the one who killed her is certainly one of the most lovely murderesses I’ve ever met: Jenny Turner.”

Jenny, still holding the candle, told her story. Unlike Grey Wyler, she was more giggly than blase about her accomplishment.

“I gave Eleanor a can of hair spray for her birthday. When she pressed the button the first time, out came a blast of spray, the top popped off, and there was a note that said, ‘Congratulations. You have just been instantly killed by prussic acid gas. Many happy returns of the day. From your hunter, Jenny Turner.’ ”

The next victim introduced by the Saint was almost invisible at his crowded table in the darkest recesses of the room.

“Now David Green’s hunter, the third prize winner, Bill Bast.”

Bast, like Jenny, treated the whole thing as a joke — emphasizing even more Grey Wyler’s seriousness about the whole thing.

“I wrote David a letter commenting on his work,” Bast said. “On college stationery. All very official. But at the end I put something like this: ‘For the last minute you have been handling paper impregnated with a deadly contact poison, phenylhydrazine. This is spreading through your system. By the time you finish reading this, you will be dead.’ ”

As the applause subsided, Simon gratefully concluded his own part in the program.

“The nature of the prizes has been kept secret. I’m told that Dr Manders will make the announcement.”

Manders managed to suppress the more obvious signs of his peevishness as he mounted the dais. Simon supposed that all men who spent a great deal of time lecturing must develop some skill as actors. Manders, while hardly enchanting, at least arranged his face into a pleasant mask.

“The prizes have been kept secret because of their nature,” he said. “And I think the news of that nature will come as a surprise to all of you — who perhaps expected something on the order of a fountain pen or a cheap chess set. You will be very pleased, I think, to hear that a special grant has been made to me by the British Foundation for the Advancement of Psychological Research — five hundred pounds worth, to be exact.”

When the oos and ahs abated, Manders went on.

“This, along with certain anonymous private donations, will be used to send our three victorious young murderers to an international conclave of Death Game prize winners... for a week’s holiday on Grand Bahama Island.”

At that point, which might have set loose an uproar, the audience seemed too stunned to move.

“I have the air tickets, which I shall now distribute. Grey Wyler, Jenny Turner, and Bill Bast will be flying across the Atlantic to the Bahamas tomorrow.”

As Manders stepped down, pulling an envelope from his jacket pocket, the response delayed from the first moment of the announcement broke with full force. Simon kept to the relative safety of the wall as students milled among the tables talking excitedly and trying to shake the hands of the prize winners. Manders had opened his envelope and was holding the tickets over his head, making his way into the center of the tumult.

Bill Bast emerged from the melange of bodies like a particle compensatorily discharged because of the entry of Dr Manders’ greater mass. He wore anything but the expression one might expect to see on the face of a man who has just been awarded a free trip to a West Indian island.

“You don’t seem very pleased,” Simon volunteered, to give Bast another chance to resume his interrupted confidences.

“I... I’m not. This is even worse — or maybe I should say stranger than I expected.”

“I gather you want to tell me about it, so I don’t think I’m prying if I suggest that you speak up. The suspense is beginning to get me.”

“Not here,” Bast said, glancing into the crowd. “You leave now while they’re all worked up and not noticing anything. I’ll join you in a couple of minutes.”

The Saint nodded agreeably. He knew now that his instinct had not been at fault. The night was definitely not going to have been wasted.

4

In the space of a few welcome lungfuls of comparatively unpolluted smog, the Saint found his way back to the psychology building. He entered the main hallway without any difficulty, but found the door to the laboratory locked. He did not have to wait long, however, before Bast appeared, a lanky figure loping along the hall like a worried giraffe.

“They think I left something behind here,” Bast said, as he unlocked the door. “They don’t know you’re with me, so I’ll try to explain fast,”

When they were inside the big room he relocked the door behind them and looked furtively around as if expecting some spy to be hiding among the fragrant cages of drowsy mice which occupied the lower part of one wall.

“If you’re worried,” Simon said, “I’m fairly certain nobody followed me.”

Bast motioned Simon to one of the wooden chairs arranged around a central table.

“I feel like an idiot, carrying on like this,” he said. “But I know it’s not my imagination. Or at least I think I know. Maybe I’m manufacturing a big dramatic fantasy out of almost nothing.”

“The psychologist speaking,” Simon said. “Let’s not worry about the epistemology of it and get on with the facts. What’s on your mind?”

Bast took a deep breath and perched on a stool with all the relaxation of a praying mantis on the head of a pin.

“I don’t have a clue as to how this Death Game started,” he said, “but it wasn’t here in London. Six months ago nobody’d ever heard of it. All of a sudden students all over the world were playing it.”

Simon shrugged.

“Stranger things have happened. Hula hoops, marathon dancing, the frug. You think there was something ominous involved?”

“Not necessarily in the beginning. As I say, I don’t know. It’s what’s happened since — here — that bothers me and makes me wonder if the whole thing really did start merely as some kind of spontaneous student fad.”

“Well, what has happened?”

“To begin right now instead of at the beginning, the British Foundation for the Advancement of Psychological Research didn’t give Dr Manders any grant of five hundred pounds.”

“So you think Manders is lying?”

“I know he is.”

“You checked with the foundation, I suppose,” Simon said.

“I couldn’t,” Bast answered. “I couldn’t even find the foundation.”

“It doesn’t exist?”

Bast fulfilled the threat of his nervous posture and took off for a fast lap around the long table.

“Oh, it exists all right — on paper. But try to find out anything about it. They’ve got a post office box and somebody who sends out vague answers to queries, and that seems to be it. They claimed they were a branch of the International Foundation for the Advancement of Psychological Research, with headquarters in Vienna, but when I inquired at that address — by mail, of course — I got no answer at all.”

“Well,” the Saint said, “so long as they’re passing out funds for worthy causes — like holidays for you in the Bahamas — I wouldn’t rock the boat. Some of the few millionaires left in this drearily democratized world choose strange ways of arranging their tax deductions.”

“I don’t think the gift comes without strings attached,” Bast said earnestly. “And I think there’s something fishy at the bottom of it. All Manders’ talk about the value of the Death Game as a research device... nonsense! There aren’t enough controls. There aren’t enough opportunities for observation — under the present setup, I mean. And who the hell would choose to donate five hundred pounds for transatlantic vacations when the department’s crying for a... well, for a better computer, for instance.”

“Maybe some millionaires just aren’t mad about computers,” Simon hazarded. “But that isn’t positive evidence of skullduggery.”

“There’s more, and this is what really got me worked up about this thing in the first place. About a month ago I was at Manders’ house one evening. We used to be on quite good terms back... before he started changing. You might say we were getting together for old times’ sake — after a faculty meeting. Anyway, he went out to the kitchen to get a bottle of whiskey. I happened to notice a letter on the floor, and I picked it up. I think the breeze may have flipped it off a stack of other papers. It was very short, so even with a glance I got the idea. It told Manders — as if it were from somebody who had a perfect right to give him orders — to send a full report on Death Game activities. The whole thing was so strange that I took another look at the signature. It was typed in under an initial ‘T’ sploshed on with one of those splurgy felt-tipped pens: Kuros Timonaides.”

The expression that appeared on Simon’s face reflected the combined feelings of recognition and distaste of a man who, after being bothered for some time by mystifying noises in his home, has just discovered a rat under the bed.

“You’ve heard of him?” asked Bill Blast.

“Haven’t you?”

“Just vaguely before I saw that letter. Mostly because he entertains film stars and titled people quite a lot and gets his name in the papers because of them. Since I saw the letter I’ve tried to find out more about him, but nothing much has been written, as far as I can tell.”

“I’m sure he likes it that way,” Simon said. “He’s one of those characters who becomes less endearing in direct proportion to the amount you know about him.”

“I can tell I picked the right person when I helped to get you mixed up in this. I’ve heard you have more in your head about the underworld than Scotland Yard has in its files.”

Simon stretched out his long legs and gave Bast a deprecating smile.

“Possibly,” he said. “More that matters, anyway. But before I share my treasure trove of knowledge about the life and good times of Kuros Timonaides, let’s hear the rest of your side of the story.”

“Just one more thing — and this is all I’ve been able to find out. Twenty-four students are flying to the Bahamas tomorrow, from all over the world. Until the party, or whatever you want to call it, tonight, I didn’t know where they were going, but I managed to find out by contacting friends at different universities that something like this was coming up. And all financed by that phony-sounding International Foundation. The only trouble is, everybody has the same reaction you had at first .. .”

“Don’t look a gift horse in the mouth?”

“Exactly.”

The Saint stood up and paced across the room to the window, by completely automatic force of habit positioning himself so that he could see out without being easily seen.

“In Timonaides’ case I’d make an exception,” he said. “I’d have any gift horse of his inspected by the most highly qualified dentist I could get — and I expect I’d find I’d just been given the world’s first stallion with three-inch tiger fangs.”

Bast grinned.

“Quite a hybrid.”

“That’s Timonaides for you: a real hybrid. Traitor, patriot, philanthropist, thief. Friend one month and blackmailer the next. But the fact that he’s not in jail, or dead, shows how skillful he’s been at keeping his head above the legal waters. Unless you can prove something — for instance that Manders is breaking the law, or that fraud is involved, or somebody’s being bilked, you won’t get much but sympathetic shrugs.”

“I have something more concrete,” Bast said.

He stood there hesitating, and the Saint gave him an encouraging nod.

“Yes?”

“I hate to admit... that I stole it.”

Simon smiled.

“What fun would it be if the bad guys had a monopoly on such grand old methods? Where is it, whatever it is?”

“Here.”

Bast plunged his hand into his jacket, pocket and drew out, his fingers trembling with nervousness, a folded sheet of stationery. Simon took it and began to read. As he scanned the typed lines his expression changed from one of tolerant interest to intense concentration.

Manders:

Enclosed, 5000 for expenses. In answer to your first question, we realize that you cannot control winners of competitions at your school, but we emphasize again the extreme importance of discovering and encouraging properly oriented students. In answer to your second question, regarding suspicions of colleagues, we hold you entirely responsible in such matters and remind you of our earlier warnings. It may be necessary to eliminate B. and if so you need no further authorization.

The letter was signed by brush-point pen with an ornate capital T.

Simon looked at Bast with his lips thoughtfully compressed.

“Well, B., I don’t blame you for feeling nervous. I don’t suppose I need to ask if Manders might have somebody else with the same initial in mind.”

Bast shook his head.

“No. He’s realized I was watching him for some time. I can tell, and I know I’m not a very subtle spy. But of course I can’t take seriously this business about eliminating anybody. Manders isn’t the sort to...”

“I wouldn’t be overconfident about that. Remember, Timonaides is today’s greatest living proof of the power of unscrupulous money. Blackmail and bribes can turn a worm into a snake. You...”

The telephone rang and Bast automatically turned to answer it.

“Bill Bast...”

He glanced at Simon, puzzled.

“Doesn’t seem to be anybody there,” he muttered. “Hullo? Hullo?”

He frowned, and held the earpiece just slightly away from his ear.

“Sounds like somebody’s whanging a bloody tuning fork...”

That was the last thing Bill Bast ever heard, except perhaps for one unearthly eternal instant of shattering thunder as the telephone receiver exploded with the noise of a shotgun shell and blasted away the side of his head.

When Simon reached him he had already stopped writhing. A final twitching spasm passed through the long body, and it lay as dead and meaningless as the slaughtered carcass of a cow or the car-smashed body of a rabbit.

5

The Saint had spent his life in the tangled jungles of violence, but he was not so inured to the spectacle of death that he could see a man destroyed directly in front of him, even one who could not yet have been called a friend, and not feel a powerful compulsion to guarantee personally that the same fate would be dealt to the murderer. He knew now that whatever plans he might have made for the next few days would have to wait until he had played out his own part in the Death Game that had not remained a game.

Within thirty seconds after the explosion, an old and half blind but obviously not entirely deaf night watchman had arrived and departed to spread the alarm, cautioning Simon not to leave the scene of the crime. The aged guardian of taxpayers’ property showed his trust of the stranger he had found in the psychology lab by locking the door behind him as he ran out and went off skidding and stumbling down the freshly waxed hall.

Simon chose not to depart by one of the easily available windows, and instead spent his time of confinement searching through Manders’ files for further clues as to his more than scholarly interest in the Death Game and his contact with Kuros Timonaides. But he had found nothing when there was a renewed sound of running footsteps in the hall and a rattle in the lock of the door.

Dr Manders hurried in, key in hand, with Jenny Turner and Grey Wyler following. Behind them were several other students.

“The watchman...” Manders gasped.

Simon pointed.

“Oh, no...” somebody whispered.

It was to Jenny’s credit that she did not scream as girls do in the movies when confronted with terrible sights. She simply gasped and turned away, supporting herself on the side of the nearest table with her eyes closed. Manders looked palely sick, and for a moment Simon thought the man was going to faint, but he held himself up, mouth trembling, and his eyes seemed to dart around the room as if looking for a place where they could hide from the sight of the mutilated body.

Grey Wyler was the first who was able to say anything.

After an initial moment of shock he had begun to study the scene with the intense fascination of a strong-stomached biology student peering into the bowels of his first dissected cat.

“It’s real,” he murmured to himself. “It happened.”

He looked at Simon, who appeared to be the only person with sturdy enough nerves to hold up the other side of a conversation.

“It really worked,” said Wyler.

“Am I to take that as a confession?” asked the Saint.

Wyler ignored the question and bent down to inspect the blasted end of the telephone receiver without touching it.

“I invented the idea,” he said. “I used it to get Peter Collins several months ago. My first decathlon.”

“Oh, Grey,” Jenny said. “This is no time to...”

Wyler interrupted her.

“The beauty of it is, you can control the timing. There was... I suppose you wouldn’t know... a tuning fork used at the other end of the line?”

“He mentioned the sound of one,” said Simon.

“There,” Wyler announced triumphantly. “Exactly as I planned it. If the wrong person answers when you call to set off the blast, you don’t twang the tuning fork.”

“Ingenious,” Simon said with dry abhorrence. “You deserve something for that.”

He had the distinct feeling, as he watched Wyler babble enthusiastically about his deadly inventiveness, that he was in the presence not merely of a neurotic, but of a mind that was dangerously unbalanced. Wyler was reacting to the whole thing as an immodest author might react to fondling a copy of his first published book. That, more than any display of shock and sorrow could have, dispelled any thoughts the Saint might have had about Wyler’s responsibility for the killing. It was highly unlikely that a murderer would choose a mood so grotesquely akin to enthralled delight for the purpose of covering his guilt. More bizarre dramatics had been tried, but in Wyler’s case the abnormal reaction seemed genuine.

Within three minutes the first policeman arrived, with the ancient watchman panting at his heels. Dr Manders, who after a long period of silence had managed to recover control of his breath and quavering lips, chose that moment to address the Saint.

“I wouldn’t be so ready to accuse Wyler, if I were you,” he said hoarsely. “You were the only one here when... when Bast was killed.”

Simon had to wait for a predictable but none the less flattering response on the part of the policeman, who recognized him immediately, came to a sudden halt, and seemed ready to back out of the laboratory and run for reinforcements.

“Simon Templar,” the officer said, as if he had to hear it himself to believe it.

“And the top of the evening to you,” said the seraphically innocent cause of his discomposure, with a slightly exaggerated bow. “How are the wife and kiddies?”

“Quite well, thank you How’d you know about them?”

“You just have the look of a nice family man.”

The policeman swallowed and tried to recover a stern and authoritative air.

“Inspector Teal is on his way.”

To one unacquainted — if there are any such still squandering their impoverished lives in the backwaters of this planet — with the history of the relationship of Simon Templar with the upper echelons of Scotland Yard, the officer’s latter statement might have seemed irrelevant, even eccentric or inexplicable. But to the more enlightened multitudes of the earth it will be perfectly apparent that the cognomen of his chieftain — Chief Inspector Claud Eustace Teal, always bested and even more often outwitted by the Saint — was in spite of its connotations of defeat and frustration the nearest thing to a protective amulet or holy name which he could draw upon in these trying circumstances. He would let the gods and Titans fight their own battles. As for him, he would merely issue the customary warning against illicit departures from the scene of the crime and busy himself with writing down the names and addresses of those present in his official notebook.

Simon turned his attention back to Dr Manders.

“I believe you were accusing me of the murder when this efficient guardian of peace and tranquillity arrived on the scene.”

Much stronger men than Manders had quailed before the sharp blue penetration of the Saint’s eyes.

“No,” he said feebly, at the same time trying to insert a measure of defiance into his tone. “I merely stated that you were the only one with Bast when he was killed. Therefore if I were in your place I wouldn’t go around insinuating...”

“Dr Manders,” said the Saint coldly, “I am not in the habit of shooting people with telephones. And I defy anybody on earth — even Inspector Teal — to come up with an even remotely plausible reason why I should want to do away with a man I met only two hours ago and don’t know the first thing about.”

That last phrase, while slightly mendacious, might at least forestall any suspicions on Manders’ part that Bast had revealed his apprehensions before he was permanently silenced. It was no more than a hope, but there was no harm in trying.

Manders opened his mouth and thought better of it. He went over to one of the larger chairs at the end of one of the tables, sat down, and supported his elbow on the surface, morosely resting his cheek on his hand.

Wyler, having completed his inspection of the death scene and given his statement, turned superciliously back to the constable, who had begun to question one of the other students.

“I see no reason for our staying here,” he said. “The crime was done by remote control. Mr Templar couldn’t have done it, if he was here in this room when the shot went off, and the rest of us just happened to be the first to arrive after we got word about the explosion. You’ve got no more reason to suspect us than those people hanging around in the hall outside.”

“Nobody is allowed to leave,” said the policeman, as if quoting from some rule book, and he went back to writing his notes.

“We have to fly to the Bahamas tomorrow,” Wyler persisted, moving close to him, tilting back his head a little so he could look down his nose at a man approximately his own height. “We can’t stay up here all night when there’s no reason for it.”

“Nobody leaves,” said the constable grimly, taking a renewed stranglehold on his stub of a pencil.

“Surely we won’t be going,” Jenny said, finding her first words since she had entered the laboratory.

She looked questioningly at Dr Manders, but he had already made a slight but definite jerking movement of his head, as if her sentence carried a minor electrical charge.

“Of course you will,” he said. “We can’t let... this interfere with everything.”

Jenny glanced in the direction of Bast’s corpse and shuddered, looking quickly away again.

“I... I’m not sure I could. I mean, I don’t really feel like much of a...”

Simon’s mind had been working with a speed and efficiency that would have dazzled the computer at the end of the room and possibly made it blink its little rows of glowing red eyes with envy. His theories and plans were not fully formulated yet, but certain broad shapes were already emerging. He was enough ahead of the game to know that if Jenny pressed her point certain things he had in mind for the immediate future might be endangered.

“Dr Manders is right,” he said gently, but with a subtle undercurrent of pressure which he hoped the girl wouldn’t try to resist. “It’s all planned, and a trip is just what you could probably use right now.”

Manders looked approving, surprised, and vaguely suspicious. The Saint turned to him, still giving the impression that he was speaking to Jenny.

“And other people might be inconvenienced if you changed your plans. That wouldn’t be fair to them, would it?”

By the end of his words he had definitely focused his attention on Manders, who uncomfortably nodded agreement.

At that moment there was a bustling in the hall clearly attendant on the arrival of some important personage. An instant later the door was thrown open by a uniformed constable, and a plump pink-cheeked man in a belted overcoat marched ponderously in, his jaw working mercilessly on a wad of chewing gum entrapped somewhere in the vicinity of his left upper and lower second molars. When he saw the Saint — as he did almost immediately — the gum received a moment’s reprieve, for the man’s jaw promptly ceased its labors and fell slackly open. The massive self-confidence seeped out of him like water out of a muslin sack.

Simon affected a second or two of puzzlement, and then of delighted recollection. He rushed forward, his hands fraternally extended, his voice throbbing with emotion.

“Why, as I live and breathe, it’s Claud Eustace Teal! Claud, I thought you were dead.”