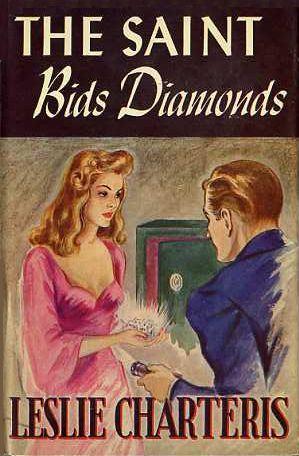

Leslie Charteris

The Saint Bids diamonds

To

Bobbie

who went on the picnic

I

How Simon Templar took exercise,

and Hoppy Uniatz quenched his thirst

1

Simon Templar yanked the hand brake back into the last notch as the huge cream-and-red Hirondel shot past the little knot of struggling men, and stood up while the tires were still screaming for a hold on the cobblestones. The Hirondel rocked to a shuddering standstill just beyond the other car that was pulled in to the side of the road; and Simon sat on the back of the seat and swung long, immaculately trousered legs over the side. From under the jauntily tilted brim of his hat he gazed back at the inspiring scene with a glimmer of reckless delight beginning to dawn in gay blue eyes which should have seemed entirely misplaced in a man who was better known as the Saint than by any other name.

In the seat beside him, Hoppy Uniatz screwed his head round on his thick neck and also surveyed the scenery, with the strain of intense thought creasing its unmistakable contortions into the rugged contours of what, from its geographical situation rather than anything else, must reluctantly be called his face. Somewhere inside him an awe — inspiringly lucid deduction was struggling for delivery.

"Boss," said Mr Uniatz, with growing conviction, "dat looks like a fight."

"It is a fight," said the Saint contentedly, and dropped lightly to the ground.

He had made the deduction several seconds earlier than Mr Uniatz, and with much less difficulty. From the moment when the headlights of the Hirondel swept round the bend and caught the group of writhing figures in their sudden blaze of illumination, it had been comparatively obvious that the nocturnal peace of the road up to La Laguna from Santa Cruz de Tenerife was being vigorously disturbed by physical dissension and all manner of mayhem — so obvious, in fact, that the Saint was treading on the brake pedal and flicking the gear lever into neutral almost as soon as the spectacle met his eyes. He had only paused for that one brief instant to decide whether the fight was merely an ordinary vulgar brawl, or whether it possessed any features which might make it interesting to a connoisseur. And, while he perched up there on the back of his seat, he had seen the vague mass of seething bodies split up into two component nuclei. In one section, two burly males were apparently trying to hammer the insides out of a third whose hair gleamed silver under the dim light; and in the other section, which more or less clinched the matter, a girl who had been trying to help him was being dragged away, fighting like a wildcat, by another of the strong — arm deputation.

Either because the combatants were so absorbed in their own business that they hadn't noticed the stopping of his car, or else because they proposed to continue operations in defiance of any casual interference, the tempo of the conflict showed no signs of slowing up as the Saint drew nearer; and a gentle and rather speculative smile shaped itself on his lips. The man who was wrestling with the girl had one hand over her mouth, and just at that moment her teeth must have managed to find one of his fingers, for his hand moved quickly and he let out a hoarse profanity which was cut off by her sharp scream for help. The Saint's smile became even gentler.

"Not so loud, lady," he murmured. "Help has arrived."

She had a face which was definitely worth fighting for, Simon realised as the man swung her round as a shield between them; and the artistic perfection of the discovery sent blissful anthems carolling through his soul. That was just as it should be — beauty in distress, and repulsive blackguards to punch firmly in the eye…

The latter ingredient struck Simon's imagination as being particularly sound. The desire to prove whether it was as satisfactory in practice as in theory became almost simultaneously irresistible. The Saint saw no reason to resist it. He shot out an exploratory fist that whizzed past the girl's ear like a bullet, and felt his knuckles smash terrifically into something crispy-soft which could have been nothing else but the desired objective in the pan of the man behind her.

The jolt ran up his arm and spread itself throughout his body in a warm tingle of ineffable beatitude. He had not been mistaken. The sensation left nothing to be improved on. It lifted up the heart and made the world a brighter and rosier place. It was the works.

"Lend me your other eye, brother," said the Saint.

The man let go the girl and kicked at him viciously; but the Saint had learnt most of his fighting in places where there were no referees, and the savagely rearing foot that would probably have crippled anyone else, hissed harmlessly past him as he stepped smoothly aside. The foot swung on upwards under its undischarged momentum, and Simon cupped his hand under the heel and helped it enthusiastically on its way. The kicker's other leg slipped from under him and he went crashing down on his back; and the Saint trod on his face and assisted the back of his head to collide with the pavement a second time, to remove all doubt.

He took the trembling girl's hand for a moment in a cool grip.

"Get along to my car," he said. "The red-and-yellow one. I'll collect Uncle."

She stared at him for a second or two, hesitantly and, it seemed, fearfully, as if she still couldn't realise that he had helped her, and as if she was terrified of a trap. The Saint turned his head so that the light fell on his face; and there must have been something in his smile that answered her doubts, for she nodded and turned obediently away.

The Saint moved on.

Three or four paces from him the other two members of the tough brigade had made good use of their time. The old man was out, out of the fight for keeps, as Simon had known he must be after a few minutes of the treatment he had been taking. He lay sprawled on the ground like a rag doll, with his head fallen limply back over the edge of the curb. One of his opponents was kneeling on his chest; and the other turned round from the diverting pastime of kicking him in the ribs to meet the Saint's approach with a rush of savagely swinging fists.

The Saint side-stepped like a dancer, blocked one blow, ducked another, and slid in with the same movement to catch him in the exact centre of his stomach with a blow that doubled him up as if he had stepped into the path of a runaway pile driver. After which something happened that the victim could never afterwards quite believe, and was inclined to attribute to the dizziness induced by the maltreatment of his solar plexus. But in the fog of agonising nausea which numbed his brain, it felt exactly as if two hands of incredible strength took hold of him at the waist and swept him high in the air, and a voice laughed softly and mockingly before the hands let him go. After which he had a feeling of floating gracefully through the air for one or two short pulsebeats before the earth rose up and hit him a frightful blow in the back that almost shattered his spine…

Simon Templar relaxed his muscles and drew a long, deep breath of sheer content. Even viewed purely in the light of healthy exercise, the dull mechanical movements which less — adventurous souls employed to develop impressive bulges on every limb were not in the same street. This, undoubtedly, as he had always been convinced, was what the doctor ordered. This was the real McCoy. And he laughed again, softly and almost inaudibly, as the last man leapt at him.

He was the largest of them all, with shoulders like an ox, though the Saint topped him in height by a couple of inches; and he came in a swerving charge that gave him the space to jerk something dark and glistening from his hip pocket. The Saint saw it and lunged like a flash of lightning for the wrist behind it. He found it and fastened on it with a grip like iron, swinging the gun out of the line of his body. The man tried to wrench free, impatiently, as he might have done from the interference of a child; and a queer look of amazement spread over his broad face when his arm stayed riveted where it was held, as if it had been pinioned in solid rock. The Saint's teeth flashed white in the gloom, and his free fist pistoned up and cracked under the other's out — thrust jaw like a gunshot. It should have dropped the large man in his tracks, but he only grunted and shook his head and hit back. Simon slipped under the punch, and they grappled breast to breast. And then there was another sharp thud, and the big man went unexpectedly limp.

Simon let him slide to the ground; and as he folded up he revealed, like an unveiled monument, the homely but supremely happy features of Hoppy Uniatz standing behind him with an automatic in his hand. For a second the Saint's memory flashed backwards in a spurt of sobering alarm, searching for a more precise definition of the timbre of the sharp thud which had preceded his opponent's collapse.

"You didn't shoot him, did you?" he asked anxiously.

"Chees no, boss," Hoppy reassured him. "I just pat him on de roof wit' de end of my Betsy. He ain't hoit."

Simon breathed again.

"I'm not quite sure whether he'd agree with you about that," he remarked. "Although I suppose it's better than being dead… But it looked like the makings of a good fight before you butted in."

He gazed around him somewhat regretfully. The high peak of vivacity in the proceedings seemed to have gone by, leaving a certain atmosphere of anticlimax. The man with the damaged face was trying to get blindly to his feet. The man who had made the short but exciting flight through the air was leaning against the back of the sedan, holding his stomach and looking as if he would like to die. The man whose roof had been patted with the end of Mr Uniatz' Betsy appeared to sleep. What with one thing and another, a shroud of appalling tranquillity had settled upon the scene.

The Saint sighed. And then he grinned vaguely and clapped Hoppy on the shoulder.

"Anyway," he said, "let's see what we fished out of the pot."

He went over to where the old man still lay with his head in the gutter, and picked him up as if he was a child. Whatever else might develop, a strategic withdrawal from the field of victory was the first indicated move. Simon carried the old man over to the Hirondel, dumped him in the tonneau, where he told Hoppy to look after him, and opened the front door for the girl.

She hesitated with one foot on the running board; and again he glimpsed that cloud of suspicion darkening her eyes.

"Really — you needn't bother… We can walk—"

"Not with Uncle," said the Saint firmly. "He doesn't feel like walking." Without waiting for her, he slid in behind the wheel and touched the starter. "Besides, your sparring partners might start walking too — they still have some life left in them—"

Crack!

The shot whined over his head and smacked into the wall beyond, and the Saint smiled as if it amused him. He caught the girl's wrist, dragged her down into the seat beside him, slammed the door and let in the clutch more quickly than the separate movements can be described. A second shot crashed harmlessly into the night; and then Mr Uniatz' Betsy answered. Then a side turning caught the Saint's eye, and he spun the wheel and sent the Hirondel screaming round in a skidding right angle. In another moment they were coasting smoothly down into the outskirts of Santa Cruz.

A little later, he heard far behind him a ragged fusillade which puzzled him for the next twelve hours.

2

But the general aspect of the affair met with his complete approval. He had no fault to find with it — even if it had temporarily interrupted the urgent and fascinating business that brought him to the Canary Islands. Adventure was still adventure, and there was always room for more — that was the fundamental article of faith which had blazed the Saint's trail of debonair outlawry through all the continents and half the countries of the world. Besides which, there were points about this adventure which were beginning to make it look more than ordinarily interesting…

He glanced at the girl again as they turned out into the wide, open space fronting the harbour.

"Where do you live?" he enquired; and his tone was as casual as if he had been driving her home from a dance.

"Nowhere!" she said quickly. And then, as if the word had come out before she realised what a ridiculous answer it was and how many more questions must inevitably follow it, she said: "I mean — I don't want to give you any more trouble. You've been awfully kind… but you can drop us anywhere around here, and we'll be quite all right."

Simon turned the car slowly round into the Plaza de la Republica and tilted his head significantly towards the tonneau.

"I'm sure you will," he agreed patiently. "But I have to keep on reminding you about Uncle. Or will you carry him?"

"Is he all right?"

She turned round quickly, and the Saint also looked back as he brought the Hirondel to a stop outside the Hotel Orotava. The only person visible in the back seat was Hoppy Uniatz, who did not seem to have fully grasped his obligations as an administrator of first aid. Mr Uniatz was lighting a large cigar; and, for all the evidence to the contrary, he might have been sitting on his patient.

"Sure, de old buzzard is okay, miss," said Mr Uniatz cheerfully. "He just took a bit of massage, but dat's nut'n. You oughta seen what de cops done to me one time when dey had me in de kitchen."

Simon saw the pain in her eyes.

"We must take him to a doctor," she said.

"By all means," he assented amiably. "Who is your doctor?"

She passed a hand shakily over her forehead.

"I'm afraid I don't know one—"

"Nor do I. And from what I do know about Spanish doctors, if he's not dead yet they'll soon find a way to finish him off. I could look after him much better myself. Why not let's take him in here and see about fixing him up?"

"I don't want to go on bothering you."

The Saint chuckled and reached back to open the rear door.

"Take him inside, Hoppy," he ordered. "Pretend he's passed out, and get him up to my room — you'd better act a bit squiffy yourself to complete the picture. We'll follow in a few minutes so it won't look too much like a party."

Mr Uniatz nodded and hauled the patient out like a sack. As he started across the pavement, he lifted up his unmelodious voice in a song of which the distinguishable words made the Saint mildly thankful that no English — speaking residents were likely to be within earshot.

Again the girl made an involuntary movement of protest; but Simon took her by the arm.

"What's on your mind?" he asked quietly; and she shrugged helplessly.

He could feel the tenseness of her under his touch.

"Let me look at you," she said.

He took off his hat and turned towards her. Her eyes searched his face. They were brown eyes, he noticed, and her hair shone copper — brown under the lamplight. He realised that if her mouth had been happy it would have been very happy, a soft, red, full-lipped mouth that would have tantalised the imagination of any man whose impulses were human.

She saw a face coloured with the warm tan of unwalled horizons and lighted with the clearest blue eyes that she had ever seen. It was a face that might have leapt to life from the portrait of some sixteenth-century buccaneer; a face that managed to harmonise a dozen strange contradictions between the firm chin and finely chiselled lips and the broad artist's forehead, and yet altogether cast in such a gay and reckless mould that it took all contradictions in its stride and made them insignificant. It was the face of a poet with the dare-devil humour of a cavalier, the face of an unrepentant outlaw with the calm straightforwardness of an idealist. It was the sort of face that she thought Robin Hood might have had — and did not know then that a thousand newspapers had unanimously named its owner the Robin Hood of modern crime.

But Simon Templar opened his face for inspection in the main square of Santa Cruz without a twinge of anxiety even for the two guardias who were strolling by; though he knew that photographic reproductions of it were to be found in the police archives of almost every civilised country in the world. For at that particular time the Saint was not officially wanted by the police of any country — a fact which many citizens who had met him in the past had reason to regard with grave indignation.

"I'm just — rather upset," she said, as if she was satisfied with the result of her scrutiny.

"That's only natural," said the Saint lightly. "Getting beaten up by a bunch of toughs isn't what they usually recommend for soothing the nerves. Now let's go and see what we can do for Uncle."

He got out and opened the door for her; and the music that was still lilting through the depths of his being opened itself up and sent its rapturous diapasons warbling towards the moon. He knew now that his inspiration must be right.

Somewhere in the vicinity of Santa Cruz there was the material for even more fun and games than he had optimistically expected — and he had come there in the definite expectation of a good deal. And he had tumbled straight into it within a few hours of getting off the boat. Which was only the normal course of events, for him. If there was trouble brewing anywhere, he tumbled into it: it was his destiny, the sublime compensation for all the other things that his outlawry might have denied him.

It never occurred to him to doubt that it had happened again. Otherwise, why had the three toughs been so very determined to beat up the old man whom he had rescued? And why, when he interfered, did they fight to the last man for the privilege of going on with the job? And why, when he had dealt with them once, had they brought their artillery into play to try and start the fight over again? And why was the girl still so afraid even of her rescuer, still suspicious of him even after he had indicated which side he was on in no uncertain manner? And why, most intriguing point of all, hadn't she volunteered one single word of explanation about how the fight started, as anyone else would automatically have done? The whole episode fairly bristled with questions, and none of them could be satisfactorily answered by the circumstances of commonplace highway robbery.

"You know," Simon burbled genially on, "these things always make me wonder for a bit whether it's safe to look a policeman in the eye for the next few days. I remember the last time anything like this happened to me — it was in Innsbruck, but it was almost exactly the same sort of thing. A friend of mine and myself horned in on a scrap where one harmless-looking little bird was getting the hide pasted off him by three large, ferocious-looking thugs. We laid them out and heaved them into the river, and it started no end of trouble. You see, it turned out that the harmless-looking little bird was carrying a bag full of stolen jewels, and the three ferocious-looking thugs were perfectly respectable detectives trying to arrest him. It only shows you how careful you have to be with this knight-errant business. - Is anything the matter?"

Her face had gone as white as milk, and she was leaning back against the side of the lift, staring at him.

"It's nothing," she said. "Just — all these other things."

"I know."

The lift stopped at his floor, and he opened the doors for her and followed her out.

"I've got a bottle of vintage lemonade that'll have you turning cartwheels again in no time," he remarked as they walked round the passage. "That is, if Hoppy hasn't drunk it all to try and revive the invalid."

"I hope you'll turn him inside out if he has," she answered; and he was amazed by the sudden change in her voice.

She was still pale, pale as death, but the terror had gone far from her eyes as if a mask had been drawn over them. She smiled up at him — it was the first time he had seen her smile, and he couldn't help noticing that he had been right about her mouth. It was turned up to him in a way that at any other time would have put irresistible ideas into his head, and she slipped a hand through his arm as they came to the door of his room. Her small fingers moved over his biceps.

"You must be terrifically strong," she said; and the Saint shrugged.

"I can usually manage to get a glass to my mouth."

A queer ghostly tingle touched the base of his spine as he opened the door and let her into the room. It wasn't anything she had said: coming from most women, her last remark would have made him wince, but she had a fresh young voice that made it seem perfectly natural. It wasn't even the new personality which she had started to take on, for that fitted her so perfectly that it was hard to imagine her with any other. The feeling was almost subconscious, a stirring of uncompleted intuition that gave him an odd sensation of walking blindfold along the edge of a precipice; and again he knew, beyond all doubt, that he was nowhere near the end of the consequences of that night's work.

The old man lay motionless on the bed, exactly as Mr Uniatz must have dumped him. Hoppy himself, as the Saint had feared, had started the work of resuscitation on himself, and half the contents had disappeared from a bottle of Haig that had been unopened when Simon left it on the table. He arrived just in time, for Mr Uniatz had the bottle in his hand when Simon opened the door and he was on the point of repeating his previous experiments. Simon took it away from him and replaced the cork.

"Thank God for non-refillable bottles," he said fervently. "They pour so slowly. If this had been the ordinary kind there wouldn't have been a drop left by now."

He went to the bed and unbuttoned the old man's coat and shirt. His pulse was all right, making due allowances for his age, and there were no bones broken: but his body was terribly bruised and his face scratched and swollen. Whether he had internal injuries, and what the effects of shock might be, would have to be decided when he recovered consciousness. He was breathing stertorously, with his mouth hanging open, and for the moment he seemed to be in no imminent danger of death.

Simon went to the bathroom and soaked a towel in cold water. He began to bathe the old man's face and clean it up as well as he could, but the girl stopped him.

"Let me do it. Will he be all right?"

"I'll lay you odds on it," said the Saint convincingly.

He left her with the towel and went back to the table to pour out some of the whiskey which he had rescued. She held up the old man's head while he forced some of it between the puffed and bleeding lips. The old man groaned and stirred weakly.

"That ought to help him," murmured Simon. "You'd better have the rest yourself — it'll do you good."

She nodded, and he gave her the glass. There were tears in her eyes, and while he looked at her they welled over and ran down her cheeks. She drank quickly, without a grimace, and put the glass down before she turned back to the old man. She sat on the bed, holding him with his head pillowed on her breast and her arm round him, rocking a little as if she were cradling a child, wiping his grimed and battered face with the wet towel while the tears ran unheeded down her cheeks.

"Joris," she whispered. "Joris darling. Wake up, darling. It's all right now… You're all right, aren't you, Joris? Joris, my sweet…"

The Saint was on his way back to the table to pour a drink for himself, and he stopped so suddenly that if she had been looking at him she must have noticed it. For a second or two he stood utterly motionless, as if he had been turned to stone; and once again that weird uncanny tingle laid its clammy touch on the base of his spine. Only this time it didn't pass away almost as quickly as it had begun. It crept right up his back until the chill of it crawled over his scalp; and then it dropped abruptly into his stomach and left his heart thumping to make up for the time it had stood still.

To the Saint it seemed as if a century went by while he stood there petrified; but actually it could have been hardly any time at all. And at last he moved again, stretching out his hand very slowly and deliberately for the bottle that he had been about to pick up. With infinite steadiness he measured a ration of whiskey into his glass, and unhurriedly splashed soda on top of it.

"Joris," he repeated, in a voice that miraculously managed to be his own. "That's rather an unusual name… Who is he?"

The fear that flashed through her eyes was suppressed so swiftly this time that if he had not been watching her closely he would probably have missed it altogether.

"He's my father," she said, almost defiantly. "But I've always called him Joris."

"Dutch name, isn't it?" said the Saint easily. "Hullo — he seems to be coming round."

The old man was moving a little more, shaking his head mechanically from side to side and moaning like a man recovering from an anaesthetic. Simon returned to the bedside, but the girl waved him away.

"Please — leave him with me for a minute."

The Saint nodded sympathetically and sauntered over to a chair. The first breath — taking shock was gone now, and once again his mind was running as cool and clear as an alpine stream. Only the high-strung tension of his awakened nerves, a pulse of vivid expectation too deeply pitched and infinitesimal in its vibration to be perceptible to any senses but his own, remained to testify to the thunderbolt of realisation that had flamed through his brain.

He slipped a cigarette from his case, tapped it, set it between his lips without a tremor in his hands, and lighted it without haste. Then he opened his wallet and took out a folded piece of blue paper.

It was a Spanish telegram form; and he read it through again for the twentieth time since it had come into his possession, though he already knew every word of it by heart. It had been sent from Santa Cruz on the twenty-second of December, and it was addressed to a certain Mr Rodney Felson at the Palace Hotel, Madrid. The message ran:

MUST REPLACE JORIS IMMEDIATELY CAN YOU SECURE SUBSTITUTE VERY URGENT

Simon folded the sheet and put it carefully away again, but the words still danced before his eyes. He drew the smoke of his cigarette deep into his lungs and let it trickle out towards the ceiling, "What's the rest of the name?" he enquired, as if he was merely making idle conversation.

A moment passed before she answered.

"Vanlinden," she said, in the same half-defiant way; and then the Saint knew that he had been right in the wild hunch that had come to him five nights ago in Madrid and sent him driving recklessly through the night to Cadiz to catch the boat that left for Tenerife the next day.

Simon looked up and realised that the scarecrow physiognomy of Mr Uniatz was becoming convulsed with the same sort of expression that might have been found on the face of a volcano preparing to erupt — if a volcano had a face. His eyes were bulging out of his head like a crab's, and his whole face was turning purple with such an awful congestion, that anyone who did not know him well might have thought that he was being strangled. The Saint, who was not in that innocent category, knew in a flash that these horrible symptoms were only the outward and visible signs of the dawning of a Thought somewhere in the dark unfathomed caves of Mr Uniatz' mind. His eyes blazed a warning that would have paralysed a more sensitive man; but all the sensitiveness in Mr Uniatz would have made a rhinoceros look like a wilting gazelle. Besides, Hoppy's cerebrations had gone too far to be suppressed: he had to get them out of his system or asphyxiate.

"Boss," he exploded, "dijja hear dat? Joris Vanlinden! Ain't dat de guy — "Yes, Hoppy, of course that's the guy," said the Saint soothingly.

He went quickly over to the bed and sat down facing the girl. It was a moment when he had to act faster than he could think, before Hoppy's blundering feet blotted out every trace of the fragile bridge that he had been trying to build. He held out his hand and smiled disarmingly into her eyes.

"Lady," he said solemnly, "this is a great moment. Will you shake?"

Her fingers met his almost immediately.

"But why?" she said.

"Just to keep me going till I can shake hands with Joris himself. I've always wanted to meet one of the boys who pulled off that job at Troschman's — it was one of the classics of the century."

"I don't think I know what you're talking about."

He was still smiling.

"I think you do. I said your father had an uncommon name, but I knew I'd heard it before. Now it's all come back to me. I knew I should never forget it."

And he was speaking nothing but the most candid truth, though she might not understand it.

When some persons unknown got into Troschman's diamond fabriek down on Maiden Lane one rainy night in April, and cleaned out a safe that had held two hundred thousand dollars' worth of cut and uncut stones, the police were particularly interested in the fact that the raid could hardly have been better timed had the raiders been partners in the business. This was impossible, for Troschman had no partners; Troschman's was a small concern which employed only one permanent cutter, taking on other workers when they were needed. As a matter of fact, this cutter was the nearest approach to a partner that Troschman had, for he was acknowledged to be one of the finest craftsmen in the trade, and had been with Troschman ever since the business was started. So that it was natural for him to be given more confidence than an ordinary employee would have received; and when the stones were collected to fill the biggest order that Troschman had ever secured in his career, this cutter was the only other man who knew when the collection was complete. His name was Joris Vanlinden.

The only reason he was not arrested at once was because the police hoped that, by keeping watch on him, they might net the whole gang at one swoop. And then, three days later, he vanished as if the earth had swallowed him up; and the hue and cry which followed had sought him for four years in vain. Only in various police headquarters did his name and description remain on record, with appropriate instructions. In various police headquarters — and in the almost equally relentless memory of the Saint…

Simon Templar could have sat down and listed the authors of every important crime committed in the last fifteen years; and that list would have included a number of names that no police headquarters had on record, and a number of crimes that no police headquarters had even recognised as crimes. He could have told you when and where and how they were committed, the exact value of the boodle, and very often what had happened to it. He could have told you the personal descriptions of the participants, their habits, haunts, specialties, weaknesses, aliases, previous record and modus operandi. He had a memory for those details that would have been worth thirty years' seniority to any police officer; but to the Saint it was worth more than that. It was half the essentials of his profession, the broad foundations on which his career had been built up, the knowledge and research on which the plans for his amazing forays against the underworld were based; and again and again ingenious felons had thought themselves safe with their booty, only to wake up too late when that unparalleled twentieth-century privateer was already sailing into their stronghold to plunder them of all that they had, until there were countless men who feared him more than the police, and unnumbered places where his justice was known to be swifter and more deadly than the Law.

The Saint said nothing about that, though there was no native modesty in his make-up. He looked the girl in the eyes and kept that frank and friendly smile on his lips.

"Don't look so scared," he said. "You've nothing to worry about. I'm in the business myself."

"You aren't anything to do with the police?"

"Oh, I have lots to do with them. They're always trying to arrest me for something or other, but so far it hasn't been a great success."

She laughed rather hysterically, a sharp and some how jarring contrast to the panic that he had seen in her face a few moments before.

"So I needn't try to keep up my party manners any more."

She shook her head and rubbed a hand over her eyes with a sort of gasp; and then all at once she was serious again, desperately serious, with that queer sort of sob in her voice. "But it's not true! It isn't true! Joris didn't get anything out of it. He wasn't one of them, whatever they say."

"That doesn't sound like very good management."

"He — he wasn't one of them. Yes, he helped them. He told them what they wanted to know. He was hard up. He lost all his savings in the stock market — and more money that he couldn't pay. And there was me… They offered him a share, and he knew that Troschman's insurance was all right. But they cheated him… They took him away when they thought he'd break down if he was arrested. Besides, they could use him. They brought him out here. But they never gave him his share. There was always some excuse. The stones would take a long time to get rid of, or they couldn't find a buyer, or something. And all the time he had to go on working for them."

"That was Graner, I suppose?"

He was still holding her hand, and he could feel her trembling.

"Do you know him?"

"Not personally."

"Yes, that was Reuben Graner." She shuddered. "But if you don't know him you couldn't understand. He's — I can't tell you. Sometimes I don't think he's human… But how did you know?"

Simon took out his cigarette case and offered it to her. Her hand was still shaking, so that she could hardly keep the cigarette in the flame when he gave her a light. He smiled and steadied her hand with cool, strong fingers.

"Reuben isn't here now, anyway," he said quietly. "And if he does walk in, Hoppy and I will beat him firmly over the head with the wardrobe. So let's take things calmly for a bit."

"But how did you know?"

"More or less by accident. You see, I came here from Madrid." He saw the awakening of understanding in her eyes and nodded. "Rodney Felson and George Holby were there."

"Do you know them?"

"Not to talk to. But I know lots of people that I don't talk to. I just happened to see them. You know Chicote's Bar?"

"I've never been to Madrid."

"If you ever go there, look in and give Pedro my love. Chicote's is one of the great bars of the world. Everybody in Madrid goes there. So did Rodney and George. Rodney had a telegram. He talked it over with George — I wasn't near enough to hear what they were saying, but in the end they screwed it up and dropped it under the table. Which was careless of them, because when they went out I picked it up."

"You picked it up?"

He grinned shamelessly.

"I told you I was in the business myself. There may be honour among thieves, but I never saw very much. I knew that Rodney and George were one of the six cleverest pairs of jewel thieves at present operating in Europe, so I just naturally thought that anything they were interested in might interest me. It did."

He took out the telegram again and gave it to her. He watched her as she read it through, and saw a trace of colour burn for a moment in her cheeks — burn till it burnt itself out and left them white again.

"He sent it as soon as he heard," she whispered. "I thought it would be like that. I could feel it. He never meant to let Joris and me go away. Oh, I knew!"

He would have guessed her age at barely twenty-one; but when she raised her eyes again there was an age of weariness in them that tied a strange knot in his throat. He took the telegram from her and put it away again.

"Did you want to go away?" he asked gently.

She nodded without speaking.

"Joris was working at his old job, I suppose," he said.

"Yes. They made him work for them. He cut and polished all the stones that came from Troschman's. Sometimes they went out and stole more, and when they brought them back he had to re-cut them so that they couldn't be identified. He had to do what they told him, because they could always have sent him back to the police. And there was me — but I told him that that didn't matter, only he wouldn't believe me."

"And now they want to replace him."

She nodded again.

"That's what Graner called it. We thought we might go away, somewhere like South America, where nobody would know us and we could live and be happy. But I knew we couldn't. Graner never meant us to. So long as Joris was working for them, it was all right. But they couldn't let him go with all that he knew. He'd never have said anything, but they couldn't be sure of that. I knew they'd never let him go alive. They meant to kill him… Oh, Joris!"

Her arms tightened convulsively about the old man's frail shoulders, and the Saint saw her eyes shining again.

"Is that what they were trying to do when I butted in?" he asked doubtfully. "It didn't look quite like that to me. After all, they could have shot him in the first place, instead of keeping their guns in their pockets till we were driving away."

"I don't know. I don't know if they meant to kill him then—"

"But if they never let him have any money, you couldn't have got very far."

She looked at him with her lip quivering; and again he saw that oddly watchful uncertainty creep into her gaze. He knew at once that she was weighing her answer, and knew also that she was going to lie.

Then he happened to glance at the old man. Joris Vanlinden had sunk back into such a stillness, and for a time they had been so carried away by other things, that they had not been noticing him. But now Simon saw that the old man's eyes had opened, quite quietly, as if he had awakened out of a deep sleep.

Simon touched the girl's arm.

"Look," he said.

He stood up and went to pour some more whiskey; and Mr Uniatz watched the performance wistfully, chewing the extinct butt of his cigar. The greater part of the dialogue had passed harmlessly over Mr Uniatz' head, which was only equipped to assimilate short and simple speeches very carefully addressed to him in the more common words of one syllable; and he had long ago started to flounder out of his depth and eventually given up the effort, seeing no reason to exhaust himself with agonising mental labour when, in the fulness of time, everything that it was good for him to know would be duly explained to him by the Saint. Besides, there was a much more urgent problem which had been occupying all his attention for some time.

"Boss," said Mr Uniatz plaintively, as if pointing out an incomprehensible oversight, "ya left a told of de bottle."

"Okay," said the Saint resignedly. "You find a home for it."

He went back to the bedside. The old man was touching the girl's face and hair with nervously twitching fingers, speaking in a weak husky voice: "Where are we, Christine?… How did we get here?… What happened?"

"It's all right, darling. Darling, it's all right. You've just got to rest."

The old man's eyes went back to the Saint, and his hand clutched at the girl's arm.

"Who are these people, Christine? I haven't seen them before. Who are they?"

"Lie still, darling." She was comforting him with a kind of motherly tenderness, as if he was a feverish child. "They won't hurt you, Joris. They came and saved you when the others were fighting you."

"Yes, they were fighting. I remember. I never could fight very much. You remember, Christine — that other time? Did they hurt you, Christine?"

"No, darling. Not a bit."

The old man's eyes closed again, and for a moment he relaxed, as if the strain of talking had been too much for him. And then, suddenly, his eyes opened again.

"Did they get it?" he asked hoarsely.

"Hush, Joris. You must be quiet."

"But did they get it?"

Vanlinden's voice was louder, and his eyes were staring. She tried to press him back on the bed, but he flung off her hands. He began to feel in his breast pocket, unsteadily at first, and then more wildly; then he was feeling in all his pockets, turning them out again and again, in a pitiful sort of frenzy.

"No, no," he muttered incoherently. "Not there. No. It's gone!" His voice rose and broke on something like a scream. "It's gone!" He stared at the Saint. "Did you take it?"

"Take what?" asked the Saint helplessly.

"My ticket!"

"Oh, a ticket. No, I haven't seen it. D'you mean your ticket for going away from here? I shouldn't worry about that. If you go and explain things to the shipping company or whatever it is—"

"No, no, not that!" Vanlinden's voice had a despairing shrillness that made the Saint's flesh creep. "My lottery ticket!"

"What?"

Christine got up suddenly from the bed. She faced the Saint like a tigress though her head barely reached his shoulder.

"Yes," she said fiercely. "Did you take it?"

"Me?" said the Saint blankly. He spread out his arms. "Search me and strip me if you want to. Take me apart and put me together again. I never saw his lottery ticket in my life."

She swung round and pointed at Hoppy Uniatz.

"He was sitting in the back of the car with Jon's all the time. Did he take it?"

"Did you take it, Hoppy?" snapped the Saint.

Mr Uniatz swallowed nervously.

"Yes, boss."

"You took it?" snapped the Saint incredulously.

Hoppy gulped.

"Yes, boss," he said apologetically. "I t'ought ya said I could take it." He pointed to the table. "Dey wasn't so much in de bottle, at dat."

"You immortal ass!" snarled the Saint. "We aren't talking about the whiskey!"

He turned back to the girl.

"Hoppy didn't take it," he said. "And neither did I.

If you don't believe us, you can go ahead and turn us inside out. I didn't even know Joris had a lottery ticket. How much was it worth?"

"You may as well know now," she said dully. "It was a ticket in the Christmas lottery. It won the first prize-fifteen million pesetas."

II

How Simon Templar conversed with a porter,

and a brace of guardias were happily reunited

1

The Saint stared at her, and then stared again at Joris Vanlinden.

He felt rather as if it was his own stomach, and not the receptacle of petrified leather which performed the same organic function for Mr Uniatz, that had absorbed the full effects of two thirds of a bottle of scotch. He knew all about the Christmas lottery, had bought tickets himself at various times, and shared the daydreams of almost every other man in Spain until the results were published. There is a Spanish national lottery three times every month; but the Navidad is the great event of the year, the time when nearly three million pounds sterling are distributed in prizes. Simon had read in the papers of men who had awakened to find themselves millionaires overnight; but he had never met one of them, and in his heart, like most other people, he could never quite convince himself that such things really did happen. The actual concrete proof of it, slapped right up in his face like that, made his head reel.

"Did Joris have the whole ticket?" he asked, trying to ease the shock. "He didn't just have a section?"

The girl shook her head. His blank and stunned bewilderment was so obvious that it must have satisfied her that he had been speaking the truth.

"No, he had it all. He must have been crazy, I suppose. I thought he was. But he said it was the only way. He saved up the little money they gave him now and again until he could buy it. And it won!"

Simon made a rapid mental calculation.

"Why hadn't it been paid yet?"

"Because we're in Tenerife."

He grinned wryly, half unconsciously.

"Of course, I'd forgotten that."

"The draw was on the twenty-first." She was speaking almost mechanically, and yet with an intense sort of eagerness, as if talking kept her mind from dwelling on other things. "The results were cabled here the next day. That was when Graner cabled to Madrid… But they don't pay on that. A few days ago they published a photographic reproduction of the official list; but they don't pay on that either. You could get a bank to discount it — they charge two per cent commission — but I don't suppose they could handle one of the big prizes. Otherwise you have to wait till the administration chooses to send a set of official lists here."

"It's a great piece of Spanish organisation, isn't it?" said the Saint aimlessly.

"The lists were supposed to be coming on the boat that got in today," she said.

Simon gazed at her for a moment longer; and then he lighted another cigarette from the butt of his last one and began to pace restlessly up and down the room, while Hoppy watched him with a kind of dog — like complacency.

It would be unfair to say that the primitive convolutions of what, on account of the limitations of the English language, can only be referred to as Mr Uniatz' brain were incapable of registering more than one idea at a time. To be accurate, they were capable of registering two; although it must be admitted that one of them was a more or less habitual and unconscious background to whatever else was going on. And this permanent and pervasive background was his sublime faith in the infallibility and divine inspiration of the Saint.

For the Saint, as Mr Uniatz had discovered, could think. He could concentrate upon problems and work them out without any perceptible signs of suffering. He could produce Ideas. He could make Plans. Mr Uniatz, a simple-minded citizen, whose intellectual horizons had hitherto been bounded by the logic of automatics and sub-machine guns, had, on their first meetings, observed these supernatural manifestations with perplexity and awe. When they met again in London, some years later, Mr Uniatz, who had been ruminating hazily about it ever since, had just reached the conclusion that if he could only hitch his wagon to such a scintillating star his life would hold no more worries.

Since it fitted in admirably with his plans at the time, Simon had let him do it. Whereupon Mr Uniatz had attached himself with a blind and unshakable allegiance from which, short of physical violence, it was impossible to pry him loose for more than a few weeks at a time. Left to himself, Hoppy would wander moodily about the earth, a spiritual Ishmael, until he could place his destiny once again in the hands of this superman, this invincible genius, who could find his way with such apparent ease through the terrifying and tormenting labyrinths of Thought. Whatever the problem in hand might be, then or at any other time, Hoppy Uniatz knew that the Saint would solve it.

He leaned forward and tapped Christine on the shoulder.

"It's okay, miss," he said encouragingly. "De boss 'll fix it. Wit' a nut like his, he could of bin a big shot in de States."

"I was a big shot," Simon retorted. "But there are limits."

He was beginning to get the finer details of the situation sorted out into a certain amount of order, but without making much difference to the dizzy turmoil into which his mind had been whirled. The more he thought about it, the more fantastic it became.

For a Spanish lottery ticket is a documento del portador, a bearer bond of the most comprehensive and undiscriminating kind in the world. Short of the most elaborate and irrefutable evidence to the contrary, combined with warrants and court orders and God knows how many other formalities, the ticket itself is the only legal claim under heaven to any prize which it may draw. There are not even any counterfoils to be retained by the original seller; so that, without that law, the administration of the lottery would be impossible. In other words, the piece of paper which Joris Vanlinden had lost, a folded sheet no more than seven inches long by four inches wide, with the thickness of the twenty sections into which a Navidad ticket is divided, was the strongest existing claim to a payment of fifteen million pesetas, two million dollars or four hundred thousand pounds at the most conservative rate of exchange — more than seven hundred pounds or thirty-five hundred dollars per square inch if you opened it out — one of the most compact and negotiable and untraceable concentrations of wealth that the world can ever have seen. The Saint had known boodle in almost every shape and form under the sun, had handled what everybody except himself would have called more than his fair share of it, but there was something about this new and hitherto unconsidered species of it that took his breath away.

He stopped walking and looked at Vanlinden again. The old man, shivering with nervous reaction and clinging pathetically to his daughter's hand, had sunk back exhausted on to the pillow. His weak, tired eyes stared mutely up at the Saint; but even he must have been convinced that Simon knew nothing, for the fire had died out of them and left only the anguish.

Simon turned to the girl.

"If Graner's idea was what you say it was, why did he let you go at all?"

"He didn't. He said he was going to, but I never, believed him. Every day I was terrified that something — something would happen to Joris. When I knew that the official lists were supposed to arrive tonight, I was… I was sure they… they would see that something happened to Joris before he woke up tomorrow."

"So you decided to make a dash for it."

She nodded.

"We said we were going to bed early and we got out of a window. Graner hadn't let the dogs out then…"

"There are dogs, are there?"

He heard her catch her breath.

"Yes. But they weren't out… We got away, and we ran. But they must have missed us. They came after us and caught us on the road. That was when you arrived."

The Saint blew two smoke rings, very carefully putting the second through the middle of the first.

"So they took the ticket," he said. "But they didn't have to kill Joris. Or did they?" His eyes pinned her again, very clear and level and bright like sapphires. "Does anything strike you about that?"

She pushed her fingers through her disordered hair.

"My God," she said, "how can I think?"

"Well, doesn't anything strike you? They may have wanted to put Joris away because he knew too much. But there may have been another reason. If he was running about loose after they'd pinched his ticket, he might make a fuss about it. It wouldn't be easy, but I suppose he could make a fuss. People don't buy a whole two-thousand-peseta Navidad ticket all to themselves so often, especially in a place like this, that the shop wouldn't be likely to remember him. If he was dead, anybody could say they bought it off him; but if he was alive and raising hell—"

"How could he? He couldn't go near the police—"

"That's a matter of opinion. Admittedly he'd be getting himself into trouble at the same time; but anyone who turns state's evidence can usually count on a good deal of leniency, and Joris has a lot less to lose than the others have. Just looking at it theoretically, when a bloke is in Joris' position, and a miracle has tossed him up within a finger's length of getting everything he wants most in the world, and then somebody snatches it away from him at the last moment and shoves him back again, it's liable to make him crazy enough to do anything for revenge. I don't know what sort of a psychologist Reuben Graner is, but I'd be inclined to look at it that way if I were in his place. What do you think, Hoppy?"

The unornamental features of Mr Uniatz marshalled themselves into an expression of reproachful anguish. Even in their moments of most undisturbed serenity, they tended to resemble something which an amateur sculptor had beaten out of a lump of clay with a large hammer, in the vain hope that his most polite friends would profess to recognise it as a human face; but when twisted out of repose they looked even more like an unfortunate essay in ultrafuturistic art, and could probably have commanded a high price from an advanced museum. Mr Uniatz, however, was not concerned about his beauty. A man of naive and elemental tastes, there was something about the mere sound of the word "think" which made him wince.

"What — me?" he said painfully.

"Yes, you."

Mr Uniatz bit another piece off the end of his cigar and swallowed it absent-mindedly.

"I dunno, boss," he began weakly; and then, with the Saint's clear and accusing blue eye fixed on him, he returned manfully to his torment. "Dis guy Graner," he said. "Is he de guy wit' de oughday?"

"We were hoping he had some."

"De guy wit' de ice?"

"That's right."

"De guy ya tell me about in Madrid?"

"Exactly."

"De guy we come here to take?"

"The same."

"De lottery guy?" said Hoppy, leaving no stone unturned in his anxiety to make sure of his ground before committing himself.

Simon nodded approvingly.

"You seem to have grasped some of it, anyway," he said. "I suppose you could call Graner the lottery guy for the present. Anyway, he's got the ticket. So the question is — what happens next?"

"Dat looks like a cinch," said Mr Uniatz airily; and the Saint subsided limply into a chair.

"One of two things has happened to you for the first time in your life," he said sternly. "Either the whiskey has had some effect, or an idea has got into your head."

Mr Uniatz blinked.

"Sure, it's a cinch, boss. All we gotta do is, we go to dis guy an' say 'Lookit, mug; eider you split wit' us on your racket, or we toin ya in to de cops.' Sure, he comes t'ru. It's a pipe," said Mr Uniatz, driving home his point.

The Saint gazed at him pityingly.

"You poor fathead," he said. "It isn't a racket. This is the Spanish official lottery. It's perfectly legal. Graner isn't running it. He's simply got the ticket that won it."

Mr Uniatz looked unhappy. The Spanish government, he felt, had done him a personal injury. He brooded glumly.

"I dunno, boss," he said at length, reverting to his original platform.

"It looks plain enough to me," said the Saint.

He sprang up again. To Christine Vanlinden, watching him, fascinated, there was an atmosphere of buoyant and invincible power about him like nothing she had ever felt about a man before. Whether he could be trusted or not, whatever scruples he might or might not have, his personality filled the room and absorbed everyone in it. And yet he was smiling, and his gesture had the faint half-amused swagger which was inseparable from every movement he made.

"Graner has got the ticket," he said. "But we've got Joris. So long as Joris is out of sight and an unknown quantity, I think Graner will be afraid to risk trying to cash the ticket. He'll try to get hold of Joris again to find out exactly how he stands. He can afford to wait a few days, and meanwhile he'll probably be trying to figure out some other way to get round the difficulty. But I don't think he'll be on the doorstep of the lottery agent first thing in the morning asking for the prize. So we hold exactly half the stakes each. And while Graner is trying to fill his hand, we can be trying to fill ours. Therefore, the next move from our side is to go and have a talk with Reuben."

He saw the quick pressure of white teeth on her lip.

"Talk to Graner?" she gasped. "You can't do that—"

"Can't I?" said the Saint grimly. "He's expecting me!"

2

Her eyes widened.

"You?"

"Yours sincerely. We got off the boat late, and then they didn't have any proper tackle to land the car. Every time they rigged up some gimcrack contraption the ropes broke, and then they all stood around waving their arms about and telling each other why it didn't work. When we did get off, I had to hang around for the other half of the day trying to get the carnet stamped. Tenerife again. After that was all over we came and fixed ourselves up here, and what with one thing and another we seemed to need a few drinks and a spot of food before we plunged into any more excitement. So we had them. Eventually we did make some enquiries about Graner, and after six people had given us sixteen different directions, we were on our way to try and find him when we met you." The Saint smiled. "But Reuben is expecting me all right!"

"Why?"

Simon looked at his watch.

"Do you know that it's just about midnight?" he said. "I think there are a few other things to be done before we talk any more. Joris needs some rest, if nobody else does." He took another quick turn up and down the room, and came back. "What's more, I don't think we'd better make any noise about having him here — the first thing Graner's crowd will do is to beat around the hotels. Hoppy brought him in as a drunk, and the night man doesn't know who's staying here and who isn't. So Hoppy had better keep him for tonight without any advertisement, and maybe tomorrow we'll think of something else to do with him. Is that okay with you, Hoppy? You can sleep on the floor or put yourself in the bath or something."

"Sure, boss," said Mr Uniatz obligingly. "Anyt'ing is jake wit' me."

"Good." Simon smiled at the girl again. "In that case, I'll just toddle down and organize a room for you."

He left the room and ran briskly downstairs. After Waking more noise than half-a-dozen inexperienced burglars trying to enter the hotel by knocking the front door down with a battering-ram, he finally succeeded in rousing the night porter from his slumbers and explained his requirement.

The man looked at him woodenly.

"Mañana," he said, with native resourcefulness. "Tomorrow, when there is someone who knows about rooms, you will be able to arrange it."

"Tomorrow," said the Saint, "the Teide may start to erupt, and the inhabitants of this God-forsaken place may move quickly for the first time in their lives. I want a room tonight. What about going to the office and looking at the books?"

" 'Stá cerrado," said the other pessimistically. "It is shut."

The Saint sighed.

"It is for a lady," he explained, attempting an appeal to the well — known Spanish spirit of romance.

The man continued to gape at him foggily. If it was a senorita, he appeared to be thinking, why should there be so much fuss about getting her a room?

"You have a room," he pointed out.

"I know," said the Saint patiently. "I've seen it. Now I want another. Haven't you got a list of the rooms occupied, so that you know how many people you have to check in before you lock up?"

"There is the list," admitted the porter cautiously.

"Well, where is it?"

The man rummaged behind his desk and finally produced a soiled sheet of paper. Simon looked at it.

"Now," he said, "does it occur to you that the rooms which are not on this list will be empty?"

"No," said the porter, "because they do not always put all the numbers on the list."

Simon drew a deep breath.

"Are you waiting for anybody else to come in?"

"Only number fifty-one," said the man, who apparently had his own clairvoyant method of checking the homing guests.

"Then the other keys in those boxes belong to empty rooms," persisted the Saint, whose association with Hoppy Uniatz had made him more than ordinarily skilful at making his points with pellucid clarity.

The porter sullenly acknowledged that this was probably true.

"Then I'll have one of them," said the Saint.

He reached over and helped himself to the key which hung in the box numbered forty-nine, which was the next number to his own. Then he opened the doors of the automatic elevator and got in. He pressed the button for the top floor. Nothing happened.

"No funciona," said the porter, with a certain morose satisfaction; and Simon heard him snoring again before he had climbed the first flight of stairs.

He recovered his good humour on the way back, partly because his mind was too taken up with other things to brood for long over the deficiencies of the Canary Island character. He had more things to think about than he really wanted, and already he began to feel the beginnings of a curious dread of the time which must come when certain questions could no longer be postponed…

"You ought to stay here and settle down, Hoppy," he remarked, as he re-entered the bedroom. "Compared with the natives, you'd look such a genius that they'd probably make you mayor. All the same, I got a room,"

He went over to the bed and felt Vanlinden's pulse again.

"Do you think you could walk a little way?" he said.

"I'll try."

Simon helped him up and kept an arm round him.

"Give me five minutes to get him undressed and into bed," he said to Christine, "and then Hoppy can bring you along."

Hoppy's room was two doors along the passage, with the room Simon had taken for Christine in between. Nearly all Vanlinden's emaciated weight hung on the Saint's strong arm.

"Don't you think I could look after myself?" he said when they got there; and the Saint dubiously let him go for a moment.

The old man started to take off his coat. He got one arm out of its sleeve; and then he stood still, and a queerly childish perplexity crinkled over his face, "Perhaps I'm not very well," he said huskily, and sat down suddenly on the bed.

Simon undressed him. Stripped naked, the old man was not much more than skin and bones. Where the skin was not raw or starting to turn black and blue, it was very white and almost transparent, with characteristic soft creases round the neck and shoulders that told their own story. Simon examined him again and treated his more obvious injuries with deft and amazingly gentle fingers. Then he wrapped him up in a suit of Mr Uniatz' eye-paralysing silk pajamas, and had just tucked him up when Hoppy and Christine arrived. Simon went back to his own room then returned to the bedside with a couple of tiny white tablets and a glass of water.

"Will you take these?" he said. "They'll help you to rest."

He supported the old man's head while he drank the water, and laid him gently back. Vanlinden looked up at him.

"You've been kind," he said. "And I am tired."

"Tomorrow you'll be crowing like a fighting cock," said the Saint.

He took Hoppy by the arm and drew him out of the room; but as soon as he turned away from the bed, the cheerfulness went out of his face. There was no doubt that Joris Vanlinden was an old man, old not only in body but also in mind; and Simon knew that, in that subtle process which is called growing old, the hopelessness of the last four years must have played more than their full part. What would be the effect of that night's beating on the old man's ebbing vitality? And how much more would the crowning blow of the stolen ticket drain from his failing strength?

Simon sat on the rail of the veranda and smoked down half an inch of his cigarette, quietly considering the questions. They were still unanswered when he forced his mind away from them. He pointed to the room.

"When you go back in there, Hoppy," he said, "lock the door and put the key in your pocket and keep it there. Don't let anybody in or out till I come round in the morning — not even yourself, unless you have to call me during the night."

"Okay, boss."

Mr Uniatz struck a match and relighted as much of his cigar as he had not yet eaten. He looked at the Saint with an expression which in anyone else might have been called reflective.

"Dis lottery ticket," he said. "It must be woit plenty."

"It is, Hoppy. It's worth two million dollars."

"Chees, boss—" Mr Uniatz counted on his fingers. "What I couldn't do wit' five hundred grand!"

Simon frowned at him.

"What do you mean — five hundred grand?"

"I t'ought ya might make dat my end, boss. De last time, ya cut me in two bits on de buck. Half a million for me an' one an' a half for you. Or is dat too much?" said Hoppy wistfully.

"Let's work it out when we get it," said the Saint shortly; and then the door opened and Christine came out.

She nodded in answer to his question.

"He's asleep already," she said. And then: "I don't see why I should turn your friend out of his bed. I can sleep in a chair and keep an eye on Joris quite easily."

"Good Lord, no," said the Saint breezily. "Hoppy can sleep anywhere. He sleeps on his feet most of the day. You can't even tell the difference until you get used to him. If Joris wants anything, Hoppy will fix it; and if Hoppy can't fix it he'll call me; and if it's anything serious I'll call you. But you need all the rest you can get, the same as Joris."

He pushed Hoppy gently but firmly away towards his vigil and unlocked the other room with the key he had taken from downstairs. He switched on the lights and followed her in, locking the door after him and taking the key out to give to her.

"Keep it like that — just in case of accidents. It's not so much for tonight as for tomorrow, in case Graner and company get up early. You can lock the communicating door on your side."

He unlocked it and went through into his own room to rake a dressing gown out of his suitcase. When he turned round she had followed him. He hung the robe over her arm.

"It's the best I can do," he said. "I'm afraid my pajamas would be a bit loose on you, but you can have some if you like. Can you think of anything else?"

"Have you got a spare cigarette?"

He took a packet off the dressing table and gave it to her.

"So if that's all we can do for you—"

She didn't make a move to go. She stood there with her hands in the pockets of her light coat and the dressing gown looped over her arm, looking at him with dried eyes that he suddenly realised might be impish. The light picked the burnished copper out of the curls on her russet head. Her coat was belted at the waist, and thrown open under the belt; under it the thin dress she wore flowed over slender curves that would have been disturbing to watch too closely.

"You didn't tell me why Graner's expecting you," she said.

He sank on to the end of the bed.

"That's easy. You see, I answered his telegram."

"You did?"

"Naturally. I knew Felson and Holby were jewel thieves. I recognised the name of Joris as… Well, frankly, it was associated with a rather famous job of jewel borrowing. And an unknown Mr Graner seemed to be tied up with the whole party. So I figured that Comrade Graner would be worth looking at. I wired him 'Know very man. Have phoned him. Says he will leave immediately' — and signed it 'Felson.'"

"You mean you were going to work for him?"

"I never cut a diamond in my life, darling. And I don't work with anybody. I just thought it might pay a dividend if I got to know Reuben a little better. Reuben would pay the dividend — but not for services rendered."

"I see." There was a quirk of humour in her straightforward brown eyes. "You thought you could blackmail him."

His fine brows slanted up at her in a line of gay, unscrupulous mockery.

"I shouldn't put it like that myself. It probably wouldn't even be literally true. I'm an idealist. You could call me an adjuster of unjust differences. Why should Graner have such a lot of diamonds when I haven't any? If he's anything like what he sounds like from the way you talk about him, it's almost a sacred duty to adjust him. Hence my telegram."

"But suppose Rodney wired him something different?"

The Saint smiled.

"I don't think either Rodney or George is sending any wires just now," he said carefully. "After I picked up the telegram I followed them out of Chicote's to keep an eye on them. As soon as they got outside, a couple of birds in plain clothes flashed badges at them, and then they all got into a taxi and drove away. From the smug expressions of the badge merchants and the worried looks of Rodney and George, I gathered that whatever they were doing in Madrid must have sprung a leak. Anyway, it was good enough to take a chance on."

"But the others'll recognise you."

"I doubt it. It was pretty dark on the road. I wouldn't be too sure of recognising them, apart from the identification marks I left on them — and I had a hat pulled down over my eyes. That's good enough to take a chance on too."

He put out his cigarette and stood up. The movement brought them face to face; and he put his hands on her shoulders.

"Don't worry any more tonight, Christine," he said. "I know it's pretty hard to take your mind off it, but you've got to try. In the morning we'll do some more work on it."

"Joris said it," she answered; "you've been very kind."

"For only doing half a job?" Simon asked flippantly.

"For being so confident and practical. I needed pulling together. It seems quite different now, with you helping us. It must be something about you…"

Her face was turned up to his, and she was So close that he could almost feel the warmth of her body. His pulses beat faster, irresistibly, but his mind was cool. He smiled at her; and suddenly she turned away and went out of the room without looking back.

The Saint took another cigarette and lighted it with elaborately unhurried precision. For quite half a minute he stood still where she had left him, before he strolled over to the wardrobe mirror and examined himself with dispassionate interest.

"You're being seduced," he said.

Then he remembered that the Hirondel was still parked outside the hotel. It couldn't stay there all night; and a faint frown touched his forehead at the thought that perhaps it had stood out there too long already. But that couldn't be helped, he had had too many other things to think of before. Fortunately he had located a garage during the afternoon. He opened the door of his room very quietly and went downstairs again.

Already the square was almost deserted — Santa Cruz goes to bed early, for the convincing reason that there is nothing else to do. Simon got into the car and drove up the Calle Castillo. He drove slowly, feeling the effortless purr of the powerful engine soothing and smoothing out his mind, a cigarette slanting between his lips and his finger tips lightly caressing the wheel. The deep hum of the machine distilled itself into his senses, taking possession of him until it was as if the car led him on without any direction of his will. He had had no such thoughts when he left the hotel to put the car away… But there was a turning on the right which he should have taken to go to the garage… He passed it without a glance. The Hirondel droned on, up on to the La Laguna road — towards the house of Reuben Graner.

3

Simon Templar began to sing, a faint fragment of almost inaudible melody that harmonised with the soft undertones of the engine. The cool night air was refreshing on his face. He was smiling.

Possibly he was quite mad. If so, he always had been, and it was too late in life to worry about it. But it was his creed that adventure waited for no timetables, and everything he had ever done or ever would do was built up on that reckless faith. He was bound to visit Reuben Graner sometime. At the moment he felt as fresh and wide awake as if he had just got out of a cold bath; and the brief but breezy episode by the roadside a couple of hours before had only whetted his appetite. Why should he wait for some Spanish mañana to carry on with the good work?

Not that he had a single plan of campaign in his head. His mind was a clean slate on which impulse or circumstance or destiny might write anything that happened to amuse them. The Saint was broadmindedly prepared to co-operate in the business of being amused…

A gleam of reminiscent humour touched his eyes as he recognised the spot where Joris Vanlinden had introduced himself so appropriately into the general course of events; and then he trod suddenly on the brakes in time to save the lives of a pareja, or brace, of guardias de asalto who stepped out into the path of his headlights and waved to him to stop. Looking around him he discovered that the road was littered with guardias of all shapes and sizes. He saw the sheen of the black oilcloth napoleonic hats of guardias civiles and the dull glint of carbines. There are various species of guardias in Spain, intended between them to perform the various functions of police work; and it is popularity believed that the word has no singular, since they are only seen in parejas, or braces, as inevitably as grouse. Even allowing for that, it seemed an unusual concentration; and the Saint's gaze narrowed slightly as the pareja which had stopped him closed in on either side of the car. A torch flashed in his face.

"Where are you going?" asked half the brace curtly, in Spanish; and Simon answered in the same language: "To visit a friend. He's expecting me."

"Baje usted."

Simon got out. The other guardia came round the car and attached himself again to his comrade. It was like a reunion of Siamese twins. Half the brace kept him covered while the other half searched him rapidly.

The Saint remembered that since he had left the hotel with no nefarious intent he had not even troubled to take a gun. He had only one weapon — the slim razor — edged throwing knife strapped to his left forearm under his sleeve which he would not have exchanged for all the firearms in the world — but the search was not thorough enough to discover that.

"Su documentación?"

Simon produced his passport. It was examined and returned to him.

"Turista?"

"Si."

"Bueno. Siga usted."

The Saint scratched his head.

"What is this?" he inquired curiously.

"That does not concern you," replied the talking half of the brace uncommunicatively and stepped back.

Simon got into the car again and drove on thoughtfully. Certainly, now that he recollected it, the rescue of Joris Vanlinden had not been accomplished in complete silence; in fact, he remembered that one or two shots had been fired in the later stages which would doubtless have been audible for some distance; but the convention of guardias gathered on the spot seemed somewhat disproportionate to the occasion, even under an administration which has always been convinced that posting a herd of police on the scene of a past crime is an infallible method of preventing another crime being committed somewhere else. He puzzled over it for a few moments, trying to recall some other factor which seemed to have slipped his memory; and then he saw the long white wall which he had been told to look out for, and the sight temporarily diverted his mind from other problems.

He drove slowly past it, and a hundred yards farther on he came to a narrow side turning into which he backed the car. He switched off the engine, turned out the lights and returned on foot. In the middle of the wall there was a wide gateway, wide enough to admit a big car — which it probably did, for the sidewalk was cut away in front of it. The gates were solid wood, studded and bound with iron, and they filled the whole archway so that it was impossible to get a glimpse of the garden inside. In the lower part of one of the gates was a smaller door. Simon scanned it in the subdued beam of a flashlight no larger than a fountain pen, and spelled out the name on the tarnished brass plate — "Las Mariposas." It was Graner's house.

He walked on, along the wall; and when it ended he climbed over the rough wire fence of the adjoining field and worked along the other side. In this way he made a complete circuit of the property, and presently found himself in the road again. The wall ran all the way round it without a break, two feet over his head the whole time; and the Saint smiled with professional satisfaction. In the circumstances, the household seemed to have all the hallmarks of really well-organised villainy, and Simon Templar approved of well-organised villains. They made life so much more exciting.

The house itself stood in one angle of the square, so that one corner of the surrounding wall was actually formed by the walls of the house itself; but the only opening in those walls was formed by two or three barred windows on the top floor. Apart from those small apertures, the walls rose sheer from the ground for thirty feet without any break or projection that would have given foothold to a lizard. There was no hope of feloniously entering the property by that route.

He returned to the first field he had entered, and inspected the wall again from that side. He reached up to the top, and felt a closely woven mesh of barbed wire under his fingers — anyone a little shorter than himself would have had to make a jump for the grip, and would have collected a pair of badly lacerated hands for compensation.

Simon bent down and took off his shoes. He placed them side by side on top of the wall, hooked his fingers over them, and in that way drew himself up. In that way he discovered something else.

A fine copper wire ran along the top of the wall, stretched between brackets in such a way that it projected about eight inches from the wall itself and also leaned slightly towards the outside. It had been invisible until he almost put his face into it, and he only just stopped pulling himself up in time. If he had been even a little clumsy with placing his shoes on top of the wall he would have touched it. He studied it intently for a few seconds. And then he lowered himself carefully to the ground, pulled his shoes down after him, and put them on again.

Exactly what useful purpose that wire served he didn't know, but he didn't like the look of it. It certainly didn't seem strong enough to hold anyone back who intended to go through it, and it wasn't even barbed. But it was so placed that no one could even pull himself up sufficiently to see over the wall without touching the wire; certainly it was impossible to scramble over it without doing so. A ladder placed up against the wall would have touched it just the same.

It might have been connected with some system of alarms, it might even have carried a charge of high-voltage electricity, it might have fired guns or sent up rockets or played martial music; but the one certain thing of which the Saint was profoundly convinced was that it hadn't been put there for fun. He was beginning to acquire a wholesome respect for Reuben Graner which nevertheless failed to depress his spirits.