THE NATIONAL DEBT

In which the Saint disguises himself as a dusty professor in order to save a lovely damsel from the clutches of a sinister conspiracy.

THE MAN WHO COULD NOT DIE

In which the Saint's well known sensitivity to the adventurous possibilities of any situation lead him to pursue the current fortunes of the extraordinary Miles Hallin, a seemingly unimpeachable man about whom it has been said that if Miles Hallin could have walked a tight rope he would have walked a tight rope stretched across the crater of Vesuvius as a kind of appetizer before breakfast.

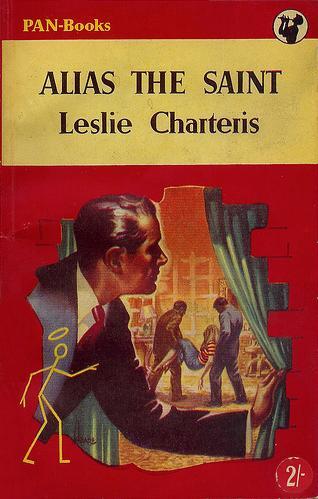

Alias The Saint

LESLIE CHARTERIS

THE NATIONAL DEBT

1

On a certain day in November three men sat over the remains of dinner in the Italian Roof Garden of the Elysion Restaurant.

Outside, a thin drizzle of sleet and rain was falling. It lay like glistening oil on the streets, and made the hurrying throngs of pedestrians turn up the collars of their coats against the cold, and huddle numbed hands deep into their pockets. But in the Roof Garden all was warmth and light and colour. In the high dim glass roof overhead, softly tinted lights gleamed like bright artificial stars; and an artificial moon shone in the centre of the dome. Vine-decked loggias surrounded the room, and the whole of one wall was covered with a beautifully executed fresco of a Mediterranean panorama, bathed in sunshine. The Elysion had a reputation for luxury, and its Italian Roof Garden was the most elaborately comfortable of all its restaurants.

The three men sat at dinner in an alcove. The curtains of the window beside them were drawn, and they could look onto Piccadilly Circus, a striking contrast to the sybaritic warmth of the room in which they were, with gaily coloured electric sky-signs flashing and scintillating through the wet.

The meal was over; and in front of each man were a cup of a coffee and a glass of the 1875 brandy of which the Elysion is justly proud, served in the huge-bowled bottle-necked glasses which such a brandy merits. They smoked long, thin, expensive cigars.

The man at the head of the table spoke.

"By this time," he said, "you are justly curious to discover how many of my promises I have fulfilled. It gives me great satisfaction to be able to tell you that I have fulfilled them all. Every inquiry has been made, and every necessary item of information is docketed here." He tapped his forehead with a thin forefinger, "My plans are complete; and now that you have tasted the brandy, which I trust you find to your liking, and your cigars are going satisfactorily, I should like your attention while I outline the details of my project."

He was tall and spare, with a slight stoop--you would have taken him at first glance for a retired diplomat, or a university professor, with his thin, finely cut face and mane of gray hair. He looked to be about fifty-five years of age, but the very pale blue eyes under the shaggy white eyebrows were the eyes of a much younger man.

"I'm waiting to hear the story, Professor," said the man on his left.

He was squat, bull-necked, and blue of chin; and his ready-made evening clothes seemed to cause him considerable discomfort.

The third man signified his readiness to listen by a silent expressive gesture with the hand that held his cigar. This third man was small and perky, his hair muddily gray and in the state tactfully described by barbers as "A little thin on top."

A long, scraggy neck protruded from a dress collar three sizes too large.

"It is quite simple," said the man who had been addressed as "Professor"; and leaned forward.

The other two instinctively drew closer.

He spoke for three quarters of an hour, and the other two listened in an intent silence which was broken only by an occasional staccato query, a request for a repetition, or a demand for more lucid explanation of a point which arose in the recital. The Professor dealt smoothly with each question, speaking in a low, well-modulated voice; and at the end of the forty-five minutes, he knew that the alert brains of the other two had grasped the essential points of his plan and adjudged it for what it was--the scheme of a genius.

"That is the method I propose to adopt," he concluded simply. "If either of you has any criticism to make, you may speak quite freely"

And he leaned back with a slight smile, as though he were convinced that-there could not possibly be any valid criticism.

"There's one thing you haven't told us," said the man on his right. "That is--where are we going to get hold of the stuff?"

"It cannot be bought," answered the Professor. "Therefore we shall make it."

The man appeared to continue in doubt.

"That's easy to say," he remarked, "Now consider it practically. Neither Crantor nor I know anything about chemistry. And you're clever in many ways, I know, but I don't believe even you can do that."

"That is quite true," said the Professor. "can't."

"A chemist must be bought," said Crantor.

The Professor shook his head.

"No chemist will be bought," he said. "We cannot afford to buy anybody. Bought men are dangerous. The man who can be bought by one party can be bought by another if the price is big enough, and I never take risks of that sort. We will compel a chemist to do what we require, and it will be so arranged that we shall be insured against betrayal. I have already selected the agent. Her name is Betty Tregarth. She is very young, but she has taken a degree with honours, and she is a fully qualified analytical chemist. At present she is on the staff of Coulter's, the artificial silk people. I have made all the necessary inquiries, and I know that. she, has all the qualifications for the task."

The man with the long neck turned, and took his cigar out of his mouth.

"Do you mind telling us how you are going to make her do it. Professor?" he asked.

"Not at all, my dear Marring," answered the Professor, and proceeded to do so.

This plan also they were unable to criticize, but Gregory Marring remained dissentient on one point.

"It oughtn't to have been a woman," he declared with conviction. "You never know where you are with women."

The Professor smiled.

"That remark only demonstrates the crudity of your intelligence," he said. "My contention is that with a woman one can always be fairly certain where one is, but men are liable to be obstinate and difficult."

The point was not argued further.

"I may take it, then," suggested the Professor, "that we are prepared to start at once,"

"There's nothing to stop us," said Marring.

"Thasso," said Crantor.

The Professor turned and gazed thoughtfully out of the window. It looked very cold and bleak outside, but what he saw seemed to please him, for he smiled.

Three nights later, at about nine o'clock, Betty Tregarth was roused from the book she was reading by the ringing of the telephone.

"Is that Miss Betty Tregarth?"

"Yes. Who is that?"

"I am speaking for your brother, Miss Tregarth. My name is Raxel--Professor Bernhard Raxel. Your brother was knocked down by a taxi outside my house a little while ago, and he was carried in here to await the arrival of an ambulance. The doctors, however, have decided against moving him."

The girl's heart stopped beating for a moment.

"Is he--is he in danger?"

"I am afraid your brother is very seriously injured, Miss Tregarth, but he is quite conscious. Will you please come at once?"

"Yes, yes!" She was frantic now. "What address?"

Number seven, Cornwallis Read. It is onlya few hundred yards from your front door.'

"I know. I'll be round in five minutes. Goodbye."

She hung up the receiver and dashed for a' hat and coat.

Only an hour ago her brother had left the flat which they shared, having declared his intention of visiting a West End cinema. He would have passed down Cornwallis Road on his way to the tube station. She dared not think how bad his injuries might be. She knew the significance of these quietly ominous summonses, for her father had been fatally injured in a street accident only three years before.

In a few minutes she was ringing the bell of Number seven, Cornwallis Road, and almost immediately the door was opened by a butler.

"Miss Tregarth?" he guessed at once, for there was no mistaking her distress. "Professor Raxel told me to expect you."

"Where's my brother?"

The man threw open a door.

"If you will wait here, Miss Tregarth, I will tell the Professor that you have arrived."

She went in. The room was furnished as a waiting room, and she wondered what the professor's profession was. There were a couple of armchairs, a bookcase in one corner, and a table in the centre littered with magazines. She sat down and strove to possess herself in patience; but she had not long to wait.

In a few moments the door opened, and a tall, thin, elderly man entered. She sprang up.

"Are you Professor Raxel?"

"I am. And you, of course, are Miss Tregarth." He took her hand. "I am afraid you will not be able to see your brother for a few minutes, as the doctor is still with him, Please sit down again."

She sat down, struggling to preserve her composure.

"Tell me--what's happened to him?"

Before answering, the Professor produced a gold cigarette case and offered it. She would have refused, but he insisted.

"It doesn't take a professor to see that you are in a bad state of nerves," he said kindly. "A cigarette will help you."

She allowed him to light a cigarette for her, and then repeated her demand for information.

"It is difficult to tell you," said Raxel slowly, and suddenly she was terrified.

"Do you mean--"

He placed the tips of his fingers together.

"Not exactly," he said, "In fact, I have no doubt that your brother is in perfect health. I must confess, my dear Miss Tregarth, that I lured you here under false pretenses. I have not seen your brother this evening, but I have been told that he went out a little over an hour ago. There is no more reason to suppose that he has met with an accident to-night than there would be for assuming that he had met with one on any other night that he chose to go put alone."

She stared.

"But you told me--"

"I apologize for having alarmed you, but it was the only excuse I could think of which would bring you here immediately."

At first he had been geniality itself; but now, swiftly and yet subtly, a sinister element had crept into his blandness. She felt herself go cold, but managed somehow to keep her voice at its normal level.

"Then I fail to see, Professor. Raxel, why you should have brought me here," she remarked icily.

"You will understand in a moment," he said. He took a small automatic pistol from his pocket, and laid it on the table in front of her. She stared at it in amazement mingled with fear

"Please take it," he smiled. "I particularly want you to feel safe, because I am going to say something that might otherwise frighten you considerably."

She looked blankly at the gleaming weapon, but did not touch it.

"Take it!" insisted the Professor sharply. "You are here in my power, in a strange house, and I am offering you a weapon. Don't be a fool. I will explain."

Hesitantly she reached out and took the automatic in her hand. Since he had offered it she might as well accept it--there could be no harm in that; and, as he had remarked, it was certainly a weapon of which she might be glad in the circumstances. Yet she could not understand why, in those circumstances, he should offer it to her. Certainly he could i-not imagine that she would make use of it.

"Of course, it isn't loaded," she said lightly.

"It is loaded," replied the Professor. "If you don't believe me, I invite you to press the trigger."

"That might be awkward for you. A policeman might be within hearing, and he would certainly want to know who was firing pistols in this house."

The Professor smiled.

"You could shoot me, and no one would hear," he said. "I ask you to observe that there are no windows in this room. The walls are thick, and so is the door--the room is practically sound-proof. Certainly the report of that automatic would not be audible in the street. I can be quite positive about that because I have verified the statement by experiment."

"Then--"

"You may understand me better," said the Professor quietly, "if I tell you first of all that I intend to keep you here for a few hours."

"Really?"

She was becoming convinced that the man was mad, and somehow the thought made him for a moment seem less alarming. But there was nothing particularly insane about his precise level voice, and his manner was completely restrained. She settled back in her chair and endeavoured to appear completely unperturbed. Then she thought she saw a gleam of satisfaction light up in his eyes as she took another puff at the cigarette he had given her, and her fingers opened and dropped it suddenly as though it had been red hot.

"And I suppose the cigarette was doped?" she said shakily.

"Perhaps," said the Professor.

He rose and went quickly to a bell-push set in the wall beside the mantelpiece, and pressed it.

Betty Tregarth got to her feet feeling strangely weak.

"I make no move to stop your going," said Raxel quickly. "But I suggest that you should hear what I have to say first."

"And you'll talk just long enough to give the dope in that cigarette time to work," returned the girl. "No--I don't think I'll stay, thanks."

"Very well," said Raxel. "But if you won't listen to me, perhaps you will look at something I have to show you."

He clapped his hands twice, and the door opened. Three men came in. One was the butler who had admitted her, the other was a dark, heavy-jowled, rough-looking man in tweeds.

The third man they almost carried into the room between them. He was tall and broad-shouldered, and he was so roped from his shoulders to his knees that he could only move in steps of an inch at a time unaided. His face was divided into two parts by a black wooden ruler, which had been forced into his mouth as a gag, and which was held in position by cords attached to the ends, which passed round the back of his head.

"Does that induce you to stay?" asked Raxel.

"I think it means that I am induced to go out at once, and find a policeman," said the girl, and took two steps towards the door.

"Wait!"

Raxel's voice brought her to a stop. The command in it was so impelling that for a moment it was able to overcome the panicky desire for flight which was rapidly getting her in its grip.

"Well?" she asked, as evenly as she could.

"You are a chemist, Miss Tregarth," said Raxel, "and therefore you will be familiar with the properties of the drug known as bhang. The cigarette you half-smoked was impregnated with a highly concentrated and deodorized preparation of bhang. According to my calculations, the drug will take effect about now. You still have the automatic I gave you in your hand, and there, in front of you, is a man gagged and bound. Stand away, you two!"

The Professor's voice suddenly cracked out the order with a startling intenseness, and the two men who had stood on either side of the prisoner hurried into the opposite corner of the room and left him standing alone.

Betty Tregarth stared stupidly at the gleaming weapon in her hand, and looked from it to the bound man who stood stiffly erect by the door.

Then something seemed to snap in her brain, and everything went black; but through the whirling, humming kaleidoscope of spangled darkness that swallowed up consciousness, she heard a thousand miles away, the report of an automatic, that echoed and reechoed deliriously through an eternity of empty blackness.

She woke up in bed, with a splitting headache.

Opening her eyes sleepily, she grasped the general geography of the room in a dazed sort of way. The blinds were drawn, and the only light came from a softly shaded reading lamp by the side of the bed. There was a dressing table in front of the window, and a washstand in one corner. Everything was unfamiliar. She couldn't make it out at first-- it didn't seem like her room.

Then she turned her head and saw the man who sat regarding her steadily, with a book on his knee, in the armchair beside the bed, and the memory of what had happened, before the drug she had inhaled overcome her, returned in its full horror. She sat up, throwing off the bedclothes, and found that she was still wearing the dress in which she had left the flat. Only her shoes had been removed.

The effort to rise made the room swim dizzily before her eyes, and her head felt as if it would burst.

"If you he still for a moment," said Raxel suavely, "the headache will pass in about ten minutes."

She put her hand to her forehead and tried to steady herself. All her strength seemed to have left her, and even the terror she felt could not give her back the necessary energy to leap out of bed and dash out of the door and out of the house.

"You'll be sorry about this," she said faintly. "You can't keep me here for ever, and when I get out and tell the police--"

"You will not tell the police," said Raxel soothingly, as one might point out the fallacies in the argument of a child. "In fact, I should think you will do your best to avoid them. You may not remember doing it, but you have killed a man. What is more, he was a detective.

She looked at him aghast.

"That man who was tied up?"

"He was a detective," said Raxel. "This is his house. I may as well put my cards on the table, I am a criminal, and I had need of your services. The detective you killed was on my trail, and it was necessary to remove him. I killed two birds with one stone. We captured him in the North, and brought him back here to his own house in London, a prisoner. His housekeeper's absence had already been assured by a fake telegram summoning her to the deathbed of her mother in Manchester. I then brought you here, drugged you with bhang, and gave you an automatic pistol."

She was aghast at a sudden recollection.

"I heard a shot--just as everything went blank. ..."

"You fired it," said Raxel smoothly, "but you are unlikely to remember that part."

Betty Tregarth caught her breath.

"It's impossible!" she cried hysterically. "I couldn't--"

Raxel sighed.

"You will disappoint me if you fail to behave rationally," he said, "The ordinary girl might be pardoned for such an outburst; but you, with your scientific training, should not need me, a layman, to explain to you the curious effects that bhang has upon those who take it. A blind madness seizes them. They kill, not knowing whom they kill, or why. That is what you did. Your first shot was successful. Naturally, you fired first at the unfortunate Inspector Henley, because I had so arranged the scene that he was the first man you saw at the instant when the drug took effect. I might mention that we had some difficulty in overpowering you afterwards and taking the pistol away from you. Henley died an hour later."

It was true--what Raxel had said was an absolute scientific fact. Granted that she had been drugged as he said, she would easily have been capable of doing what he said she had done.

"The terrifying circumstances," Raxel went on unemotionally, "probably hastened your intoxication. Your immediate impulse was to escape from the room at all costs, and Henley was the one man who stood between you and the door. You shot your way out--or tried to. It is all quite understandable.

"O God!" said Betty Tregarth softly.

Raxel allowed her a full five minutes of silence in which to grasp the exact significance of her position, and at the end of that time the pain in her head had abated a little.

"I don't care," she said dazedly. "I'll see it through--I'll tell them I was drugged."

"That is no excuse for murder," said Raxel, "and taking drugs is, in itself, an offense."

"But I can tell them everything about it--how you brought me here. There's proof. You telephoned. The exchange can prove that."

"The exchange can prove nothing," said Raxel. "I did not telephone--I should be a very poor tactician to have overlooked such an obvious error. Your line was tapped, and the exchange has no record of the call. I must ask you to realize the circumstances. You will be taken away from here, and the house will be left exactly as we found it. The only fingerprints will be yours on the automatic you used. Nothing has been moved, and Inspector Henley will be found lying dead here when the police are summoned by his housekeeper on her return. We have treated him very gently during his captivity; and before we leave, the ropes that bound him will be removed, so that from an examination of his body it will be impossible to prove that he was not completely at liberty, in his own house--as any man, even a detective, has every right to be. The scene will be staged in such a way that the detectives, unless they are absolute imbeciles, will deduce that Henley was entertaining a woman here, and that for some reason or other she shot him. The woman, of course, will be you. But your finger-prints are not known to the police, and there will be nothing to incriminate you unless I should write and tell them, in an anonymous letter, where they scan find the owner of the fingerprints on the gun, I don't want to have to do that."

"Then what do you want?"

"Your loyal support," said Baxel. "To-morrow you will go to Coulter's and tell them that your doctor has advised you to take a rest cure, as you are in danger of a nervous breakdown. You will tell your brother the same story. Then you will go down with me to an inn in South Wales, which I have recently purchased, and in which I have installed an expensive laboratory. There you will work for me--and it will only be for three weeks. At the end of that time, if you have done your work satisfactorily, you will be free to go home and return to your job, and I will pay you a thousand pounds for your services. Incidentally, I can assure you that you will not be asked to do anything criminal. I required a qualified chemist on whose silence I could rely--that is all. Therefore I took steps to secure you. I do not think any jury would be likely to hang you, but you would certainly go to prison for a long time--if you were not sentenced to be detained at Broadmoor during His Majesty's pleasure--and fifteen years spent in prison would rob you of the best part of your life. As an alternative to such a punishment, I think you should find my suggestion singularly acceptable."

"And what am I supposed to do in this laboratory?

He answered her question in three brief sentences, and she gasped.

"Why do you want that?" she answered.

"That is no concern of yours," answered Raxel. "You will not be asked to associate yourself with my use of it, and so you need have no fear that you will be incriminating yourself. I promise you that when you have made a sufficient quantity for my ends, I shall ask nothing more of you. Nothing shall be done to stop your return home, and no one need ever know what you have been doing. You can, if you like, adopt me as your physician, and tell any inquirers that you are taking a cure under my personal supervision. We can arrange that. Also, I give you my word of honour that no harm shall come to you while you are in my employ."

He looked at his watch.

"It is half-past ten," he said. "You have hardly been unconscious an hour, though I expect you have been wondering how many days it has been. There is plenty of time for you to give me your answer and be back at the flat by the time your brother returns. And there is only one answer that you can possibly give."

2

Besides the huge flying Hirondel that was the apple of his eye, Simon Templar possessed another and much less conspicuous car which ran excellently downhill, and therefore he was able to descend upon Llancoed at a clear twenty miles an hour.

The car (he called it Hildebrand, for no reason that the chronicler, or anyone else in this story, could ever discover) was of the model known to the expert as "Touring," which is to say that in hot weather you had the choice of baking with the hood down, or broiling with the hood up. In wet weather you had the choice of getting soaked with the hood down, or driving to the peril of the whole world and yourself while completely encased in a compartment as impervious to vision as it was intended to be impervious to rain. It dated from one of the vintage years of Henry Ford, and the Saint had long ago had his money's worth out of it.

On this occasion the hood was up, and the side-curtains also, for it was a filthy night. The wind that whistled round the car arid blew frosty draughts through every gap in the so-called "all-weather" defenses seemed to have whipped straight out of the bleakest fastnesses of the North Pole. With it came a thin drizzle of rain that seemed colder than snow, which hissed glacially through a clammy sea mist, The Saint huddled the collar of his leather motoring coat up round his ears, and wondered if he would ever be warm again.

He drove through the little village, and came, a minute later, to his destination--a house on the outskirts, within sight of the sea. It was a long, low, rambling building of two stories, and a dripping sign outside proclaimed it to be the Beacon Inn, It was half-past nine, and yet there seemed to be no convivial gathering of villagers in any of the bars, for only one of the downstairs windows showed a light. In three windows on the first floor, however, lights gleamed from behind yellow blinds. The house did not look particularly inviting, but the night was particularly loathsome, and Simon Templar would have had no difficulty in choosing it even if he had not decided to stop at the Beacon Inn nearly twelve hours before.

He climbed out and went to the door. Here lie met his first surprise, for it was locked. He thundered on it impatiently, and after some time there was the sound of footsteps approaching from within. The door opened six inches, and a man looked out.

"What do you want?" he demanded surlily.

"Lodging for a night--or even two nights," said the Saint, cheerfully.

"We've got no rooms," said the man.

He would have slammed the door in the Saints face, but Simon was not unused to people wanting to slam doors in his face, and he had taken the precaution of wedging his foot in the jamb.

"Pardon me," he said pleasantly, "but you have got a room. There are eight bedrooms in this plurry pub, and I happen to know that only six of them are occupied."

"Well, you can't come in," said the man gruffly. "We don't want you."

"I'm sorry about that," said the Saint, still affably. "But I'm afraid you have no option. Your boss, being a licensed innkeeper, is compelled to give shelter to any traveller who demands it and has the money to pay for it. If you don't let me in, I can go to the magistrate to-morrow and tell him the story, and if you can't show a good reason for having refused me you'll be slung out. You might be able to fake up a plausible excuse by that time, but the notoriety I'd give you, and the police attention I'd pull down on you, wouldn't give you any fun at all. You go and tell your boss what I said, and see if he won't change his mind."

At the same time, Simon Templar suddenly applied his weight to the door. The man inside was not ready for this, and he was thrown off his balance. Simon calmly walked in, shaking the rain off his hat.

"Go on--tell your boss what I said," said the Saint encouragingly. "I want a room here to-night, and I'm going to get one."

The man departed, grumbling, and Simon walked over to the fire and warmed his hands at the blaze. The man came back in ten minutes, and it appeared at once that the Saint's warning had had some effect.

"The Guv'nor says you can have a room."

"I thought he would," said the Saint comfortably, and peeled off his coat. There were seventy-four inches of him, and he looked very lean and tough in his plus-fours,

"There's a car outside," he said. "Shove it in your garage, will you. Basher?"

The man stared at him.

"Who are you speaking to?" he demanded. "Speaking to you, Basher Tope," said the Saint pleasantly. "Put my car in the garage."

The man came nearer and scowled into Simon's face. The Saint saw alarm dawning in his eyes. "Who are you?" asked Tope hoarsely, "Are you a split?"

"I am," admitted the Saint mendaciously. "We wondered where you'd got to, Basher. You've no idea how we miss your familiar face in the dock, and all the wardens at Wormwood Scrubs have been feeling they've lost an old friend."

Basher's mouth twisted.

"We don't want none of you damned flatties here," he said. "The Guv'nor better hear of this."

"You can tell the Guv'nor anything you like after you've attended to me," said the Saint languidly. "My bag's in the car. Fetch it in. Then bring me the register, and push the old bus round to the garage while I sign. Then, when you come back, bring me a pint of beer. After that, you can run away and do anything you like."

It is interesting to record that Simon Templar got his own way. Basher Tope obeyed his injunctions to the letter before moving off with the obvious intention of informing his boss of the disreputable policeman whom he was being compelled to entertain. Of course, Basher Tope was prejudiced about policemen; and it must be admitted that the Saint used menaces to enforce obedience. There was the little matter of a robbery with violence, for which Basher Tope had been wanted for the past month, as the Saint happened to know, and that gave him what many would consider to be an unfair advantage in the argument,

Left alone with a tankard of beer at his elbow, the register on his knee, a cigarette between his lips, and his fountain-pen poised, Simon read the previous entries with interest before making his own. The last few names were those which particularly occupied his attention:

A.E. Crantor Bristol British

Gregory Marring London British

E. Tregarth London British

Professor Bernhard Raxel Vienna Austrian

All these entries were dated about three weeks before, and none had been made since.

Simon Templar smiled, and signed directly under the last entry;

Professor Rameses Smith-Smyth-Smythe..

Timbuctoo, Patagonian

"And still," thought the Saint, as he carefully blotted the page, "the question remains--who is E. Tregarth?"

3

The saint went to bed early that night, and he had not seen any of the men he hoped to find. That fact failed to trouble him, for he reckoned that the following day would give him all the time he needed for making the acquaintance of Messrs. Raxel, Marring, and Crantor.

He got up early the next morning and went out to have a look round. The mist had cleared, and although it was still bitterly cold the sky was clear and the sun shone. Standing just outside the door of the inn, in the road, he could see on his left the clustered houses of the village of Llancoed, of which the nearest was about a hundred yards away. On the other side of the road was a tract of untended ground which ran down to the sea, two hundred yards away. A cable's length from the shore, a rusty and disreputable-looking tramp steamer, hardly larger in size than a sea-going tug, rode at anchor. A thin trickle of black smoke wreathed up into the still air from her single funnel, but apart from that she showed no signs of life.

Simon returned to the inn and discovered the dining room.

It contained only three tables, and only one of these was laid. In the summer, presumably, it catered for the handful of holiday makers who were attracted by the quietness of the spot, for there were green-painted chairs and tables stacked up under a tarpaulin outside; but in December the place was deserted except for the villagers, and those would be likely to eat at home. The table was laid for four. The Saint chose the most comfortable of the selection of uninviting chairs that offered themselves, and thumped on the table with the handle of a knife to attract attention. It was Tope who answered.

"Breakfast," said the Saint laconically. "Two boiled eggs, toast, marmalade, and a pint of coffee."

Tope informed him that the table he occupied was engaged, and Simon mildly replied that he was not interested.

"It's the only table that looks ready for use," he pointed out, "and I want my breakfast. You can be laying a table for the other guys while I eat. Jump to it. Basher, jump to it!"

Basher Tope muttered another uncomplimentary remark about interfering busies what thought they owned the earth, and went out again. The Saint waited patiently for fifteen minutes, and at the end of that time Tope reentered, bearing a tray, and banged eggs, toast rack, and coffee pot down on the table in front of him.

"Thank you," said the Saint. "But you don't want to be so violent, Basher. One day you'll break some of the crockery, and then your boss will be very angry. He might even call you a naughty boy, Basher, and then you'll go away into a quiet corner and weep, and that would be very distressing for all concerned."

Basher Tope was moved to further criticisms of the police force and their manners, but Simon took no further notice of him, and after glaring sullenly at the detective for some moments. Tope turned on his heel and shuffled out again.

The Saint was skinning the top of his second egg when the door opened and a girl came in. She was wearing a plain tweed costume, and Simon thought at once that she must be the loveliest thing that had ever walked into that sombre room. He rose at once.

"Good-morning," he said politely. "I'm afraid I've pinched part of your table, but the cup smasher who attends to these things couldn't be bothered to lay another place for me."

She come up hesitantly, staring at him in bewilderment. She saw a tall, broad-shouldered young man, with twinkling blue eyes, smooth dark hair, and the most engaging smile she had ever seen in her life. Simon, modestly realizing that her amazement at seeing him was pardonable, bore her scrutiny without embarrassment.

"Who are you?" she asked at length,

The Saint waved her to a chair, and she sat down opposite him. Then he resumed his own seat and the assault on the second egg.

"Me? . . . Professor Smith, at your service. If you want to call me by my first name, it's Rameses. The well-known Egyptian Pharaoh of the same label was named after me."

"I'm sorry," she said at once. "I must have seemed awfully rude. But we--I mean, I wasn't expecting to see a stranger here."

"Naturally," agreed the Saint conversationally. "One's never expecting to see strangers, is one? Especially of the name of Smith. But I'm the original Smith. Look for the trade-mark on every genuine article, and refuse all imitations."

He finished his egg, and was drawing the marmalade towards him when he noticed that she was still looking at him puzzledly.

"Now you'll be thinking I'm rude," said Simon easily. "I ought to have noticed that you weren't being attended to. The service is very bad here, don't you think?"

He banged the table with his knife, and presently Tope came to answer.

"The lady wants her breakfast," said the Saint, "Jump to it again, Basher, and keep on jumping until further notice."

The door closed behind the man, and Simon began to clothe a slice of toast with a thick layer of butter.

"And may one ask," he murmured, "what brings you to this benighted spot at such a benighted time of year?"

His words seemed to bring her back to earth with a jerk. She started, and flushed; and there was a perceptible pause before she found her voice.

"Couldn't one ask the same thing about you?" she countered.

"One could," admitted the Saint genially. "If you must know, I shall be strenuously occupied for the next few days with the business of being Professor Rameses Smith."

"The famous charlatan, humbug, and imitation humorist?" she suggested.

Simon regarded her delightedly.

"None other," he said. "How did you ever guess?"

She frowned.

"You were so obviously that sort."

"True," said the Saint, unabashed. "But in my spare time I am also a detective."

He was watching her closely, and he saw her go pale. Her hands suddenly stopped playing with the fork which she had picked up and with which she had been toying nervously. She sat bolt upright in her chair, absolutely motionless, and for the space of several seconds she seemed even to have stopped breathing.

"A--detective?"

"Yes." Simon was unconcernedly providing his buttered toast with an overcoat of marmalade. "Of course, I was sitting down when you came in, so you wouldn't have noticed the size of my feet."

She said nothing. Tope came in with a tray and began unloading it, and Simon Templar went on talking in his quiet flippant way without seeming to notice either the girl's agitation or the other man's presence.

"Being a detective in England," he complained, "has its disadvantages. In America you can always prove your identity by clapping one hand to your hip and using the other to turn back the left lapel of your coat, thereby revealing your badge. It's a trick that always seems to go down very well---that is, if you can judge by the movies."

The colour was slowly ebbing back into the girl's face, but her hands were trembling on the table. She seemed to become conscious of the way they were betraying her, and began twisting her fingers together in a fever. In the silence that followed, Tope shambled out of the room, but this time he did not quite close the door. The Saint had no doubt that the man was listening outside, but he could see no reason why Basher Tope should be deprived of the benefits of a strictly limited broadcasting service. As for the girl, it was plain that the Saint's manner had started to convince her that he was jollying her, but he couldn't help that.

"Is there any reason," he asked, "why I shouldn't be a detective? The police force is open to receive any man who is sufficiently sound of mind and body. I grant you I have a superficial resemblance to a gentleman, but that's the fault of the way I was brought up."

She had no time to frame a reply before there came the sound of voices approaching outside, and a moment later the door swung open and three men came in.

Simon Templar looked up with innocent interest at their entry, but he also spared a glance for the girl. Obviously she was one of their party; but she did not strike Simon as being the sort of girl he would have expected to find in association with the men he was after, and he had some hopes of getting a clue to her status with them by observing the way in which she greeted their arrival. And he was not unpleasantly surprised to find that she looked up furtively--almost, he would have said, in terror.

The three men, as the Saint might have foreseen, showed no surprise at finding him at their table. They came straight over and ranged themselves before him, and Simon rose with his most charming smile.

"Good-morning," he said.

The tallest of the three bowed.

"Our table, I think, Professor Smith?"

"Absolutely," agreed the Saint." I've just finished, and you can step right in"

"You are very kind."

Simon screwed up his napkin, dropped it on the table, and took out his cigarette case. His eyes focused thoughtfully on the man who stood on the left of the tall man who appeared to be the leader.

"Mr. Gregory Marring, I believe?"

"Correct. ''

"Six months ago," said the Saint, "a special messenger left Hatton Garden for Paris, with a parcel of diamonds valued at twenty thousand pounds. He travelled to Dover by the eleven o'clock boat-train from Victoria. He was seen to board the cross-Channel packet at Dover, but when the ship arrived at Calais he was found lying dead in his cabin with his head beaten in, and the diamonds he carried have not been heard of since. I don't want you to think I am making any rash accusations, Marring, but I just thought you might be interested to hear that I happen to know you travelled on that boat."

His leisurely gaze shifted to the man on the extreme right.

"Mr. Albert Edward Crantor?"

"Thasso."

"The Court of Inquiry could only find you guilty of culpable negligence," Said the Saint, "but the Special Branch haven't forgotten the size of the insurance, and they're still hoping that it won't be long before they can prove you lost your ship deliberately. The case isn't ready yet, but it's tentatively booked for the next Sessions. I'm just warning you."

The man in the centre smiled.

"Surely, Professor Smith," he remarked, "you aren't going to leave me out of your series of brief biographical sketches?"

"For the moment I prefer to," answered the Saint steadily. "At any moment, however, I may change my mind. When I do, you'll hear from me soon enough. Good-morning, my lovely ones."

. He turned his back on them and walked quietly to the door; but he opened the door with an unexpectedly sudden jerk, and the movement was so quick that Basher Tope had no time to recover his balance and fell sprawling into the room. Simon caught him by the collar and yanked him to his feet.

"This reminds me," said the Saint, turning. "There was another man skulking around when I came down this morning. I know him, too."

The other three were plainly surprised.

"Everyone here of importance is presently in this room," said Raxel. "You must be suffering from a delusion."

"The man I saw was no delusion," Smith replied. "His name is Duncarry. He's a much-wanted American gun artist who's come to England for his health. We still don't know how he slipped into the country, but he's one of the men I'm taking back to London with me when I go. There's a seat reserved for him in the hot chair at Sing Sing, and if you see him loafing around here again you can tell him I said so!"

With that parting shot he left them, and as he closed the door softly behind him he began to whistle.

"Now I guess I've rubbed the menagerie right on the raw!" Simon Templar thought cheerfully. "If my after-breakfast speech doesn't make those gay birds hop, I wonder what will?"

4

Simon spent the morning reading and drinking beer. The three men and the girl sat late over breakfast, and he guessed that his arrival had been the occasion for a council of war. When they came out of the dining room, however, they walked straight past him without speaking, and ignored his existence. They went upstairs, and none of them even looked back.

They did not appear again for the rest of the morning; but at about twelve o'clock Detective Duncarry was ushered upstairs by Basher Tope. He was there twenty minutes, and when he came down again he was peeling off his coat and generally conveying the impression of being here to stay. Simon shrewdly surmised that the congregation of the ungodly was now increased by one, but Basher Tope took no notice of the Saint, and led Duncarry round in the direction of the public bar without speaking a word. It must be recorded that Simon Templar took a notably philosophic view of this sudden passion for ignoring his existence.

He lunched early, and Basher Tope returned exclusively monosyllabic replies to the cheerfully aimless conversation with which Simon rewarded his ministrations. After about the fourth unprofitable attempt to secure the observation of the conversational amenities, the Saint sighed resignedly and gave it up as a bad job.

After lunch he put on his hat and went out for a brisk walk, for he had decided that there was nothing he could do in broad daylight as long as the whole gang were in the house. With characteristic optimism, he refused to consider what particular form of unpleasantness they might be preparing for his entertainment that night, and devoted himself whole-heartedly to the enjoyment of his exercise. He covered ten miles at a brisk pace, and ended up with a ravenous appetite at the only other ina which the village boasted.

The proprietor and his wife were clearly surprised by his demand for a meal, but after first being met with the information that they were not prepared to cater for visiting diners, he successfully contrived to blarney them into accommodating him. The Saint thought that that was only a sensible precaution to take, for by that time no one could tell what curious things might be happening to the food at the Beacon.

He ate simply and well, stood the obliging publican a couple of drinks, and went home about ten o'clock.

As he approached the Beacon he took particular note of the lighting in the upstairs windows. Lights showed in only two of them, and these were two of the three that had been lighted up on the night he arrived. There were few lights downstairs--since the change of management, the Beacon had become very unpopular. The Saint had gathered the essential reasons for this from his conversation with the villagers in the rival tavern. The new proprietor of the Beacon was clearly running the house not to make money but to amuse himself and entertain his friends, for visitors from outside had met with such an uncivil welcome that a few days had been sufficient to bring about a unanimous boycott, to the delight and enrichment of the proprietor of the George on the other side of the village.

The door was locked, as before, but the Saint hammered on it in his noisy way, and in a few moments it was opened.

"Evening, Basher," said the Saint affably, walking through into the parlour. "I'm too late for dinner, I suppose, but you can bring me a pint of beer before I go to bed."

Tope shuffled off, and returned in a few moments with a tankard.

"Your health. Basher," said the Saint, and raised the tankard.

Then he sniffed at it, and set it carefully down again.

"Butyl chloride," he remarked, "has an unmistakable odour, with which all cautious detectives make a point of familiarizing themselves very early in their careers. To vulgar people like yourself, Basher, it is known as the knockout drop, and one of the most important objections that I have to it is that it completely neutralizes the beneficial properties of good beer."

"There's nothing wrong with that beer," growled Basher.

"Then you may have it," said the Saint generously. "Bring me a bottle of whisky. A new one--and I'll draw the cork myself."

Basher Tope was away five minutes, and at the end of that time he came back and banged an unopened bottle of whisky and a corkscrew down on the table.

"Bring me two glasses," said the Saint.

Basher Tope was back in time to witness the extraction of the cork; and Simon poured a measure of whisky into each glass and splashed water into it.

"Drink with me, Basher," invited the Saint cordially, taking up one of the glasses.

Tope shook his head.

"I don't drink."

"You're a liar, Basher," said the Saint calmly. "You drink like a particularly thirsty fish. Look at your nose!"

"My nose is my business," said Tope truculently.

"I'm sorry about that," said Simon. "It must be, rotten for you. But I want to see you have a drink with me. Take that glass!"

"I don't want it," Tope retorted stubbornly.

Simon put his glass down again.

"I thought the lead cap looked as if it had been taken off very carefully, and put back again," he said. "I just wanted to verify my suspicions. You can go. Oh, and take this stuff with you and pour it, down the sink."

He left Basher Tope standing there and went straight upstairs. The fire ready-laid in his bedroom tempted him almost irresistibly, for he was a man who particularly valued the creature comforts, but he felt that it would be wiser to deny himself that luxury. Anything might happen in that place at night, and Simon decided that the light of a dying fire might not be solely to his own advantage.

He undressed, shivering, and jumped into bed. He had locked his door, but he considered that precaution of far less value than the tiny little super-sensitive silver bell which he had fixed into the woodwork of the door by means of a metal prong.

He had blown out the lamp, and he was just dozing when the first alarm came, for he heard the door rattle as someone tried the handle. There followed three soft taps which he had to strain to hear.

With a groan, Simon flung off the bedclothes, lighted the lamp, and pulled on his dressing gown. Then he opened the door.

The girl he had met that morning stood outside, and she pushed past him at once and closed the door behind her. The Saint seemed shocked.

"Don't you know this is most irregular?" he demanded reprovingly.

"I haven't come here to be funny," she flashed back, in a low voice. "Listen to me---were you talking nothing but nonsense this morning?"

"Not altogether," replied Simon cautiously. "Although I don't mind admitting--"

"You're a detective?"

"Er--occasionally," said Simon modestly.

The girl bit her lip.

"Whom are you after?" she asked.

Simon's eyebrows went up.

"I'm after one or two people," he said. "Marring and Crantor, for instance, I hope to include in the bag. But the man I'm really sniping for is Bunnywugs.''

"You mean Professor Raxel?"

"That's what he's calling himself now, is it? I've heard him spoken of by a dozen different names, but he's best known as the Professor. He has a certain reputation."

The girl nodded.

"Well," she said, "you gave the gang some pretty straight warnings at breakfast. Now I'm warning you. If the Professor's got a reputation, you can take it from me he's earned it. You've bitten off a lot more than you can chew, Smith, and if you go on playing the fool like this it'll choke you!"

"Rameses is rather a mouthful, I grant you, so my friends usually call me Simon," said the Saint wistfully.

The girl stamped her foot.

"You can be funny at breakfast to-morrow, if you live to eat it," she shot back. "For God's sake-- can't you see what danger you're in?"

"Now I come to think of it," murmured the Saint, "you must have a name, too."

"Tregarth's my name," she told him impatiently.

"It must have been your father's," said the Saint, with conviction. "Tell me--what else do the family call you to distinguish you from him?"

"Betty Tregarth.

Simon held out his hand.

"Thanks, Betty," he said seriously. "You're rather a decent kid. I'm sorry you're mixed up in this bunch of bums.''

"I'm not!" she began hotly, and then suddenly fell silent, her face going white, for she realized how impossible it would be to tell him the true circumstances.

And the realization cut her like a knife, for Simon Templar was smiling at her in a particularly nice way; and she knew at once that if there was one man in the whole world whom she might have trusted with such a story as hers, it was the smiling young man with the hell-for-leather blue eyes who stood before her arrayed in green pajamas and a staggering silk dressing gown that would have made Joseph's coat look like a suit of deep mourning. And by the cussedness of Fate it had had to so happen that he was also one of the few men in the world in whom she could not possibly confide. She felt hot tears stinging her eyelids--tears that she longed to shed, and could not.

"Shake, Betty," said the Saint gently, and she took his hand.

He looked down at her, still smiling in that particularly nice way.

"Thanks for coming," he said. "But it's ho use, though--I'm staying here as long as the job takes. If you'll adopt me as a sort of honorary uncle and take my advice, you'll get out of this as quick as you can. Pack your bag to-night, and hike for the station first thing to-morrow morning. That's a straight tip. And if you do decide to get out, and the other tumours cut up queer, just blow me the wink and I'll see you through. That's a promise."

He opened the door for her, and he had to let go her hand to do it.

"Good-night," said the Saint.

"Good-night," she said, with quivering lips and an ache in her throat.

He closed the door on her, and she heard the key turn in the lock.

5

He rolled back into bed again, blew out the lamp, snuggled down, and was asleep in a few minutes, The prospect of being the object of the attentions of other nocturnal visitors not so kindly disposed towards him failed to disturb his slumbers for he knew exactly how far he could trust his powers of sleeping as lightly as he wished to.

His confidence was justified; for when, three hours later, the door began to swing open under the impulse of a stealthy hand, the almost inaudible ting! of the little bell he had attached to it was sufficient to rouse him, and in an instant he was wide awake

He pushed back the blankets and slid soundlessly out of bed, taking with him the electric torch and automatic pistol which were under his pillow.

The room was in pitchy darkness. The Saint waited a moment until he judged that the intruder was right inside the room, and then switched on his torch. It picked up the figure of Basher Tope, advancing cat-footed towards the bed, and in Basher Tope's right hand was the instrument which had won him his nickname--a wicked-looking black-jack.

"Hullo, Basher!" said the Saint brightly. "Come to hear a bedtime story from Uncle Rameses?"

For answer Tope leaped, swinging his bludgeon, but the blinding beam of light that concentrated in his eyes was extinguished suddenly, and he struck empty air. He felt his way round cautiously, and found the bed empty. Then he heard a mocking laugh behind him, and spun round. The torch was switched on again, and focused him from the other side of the room.

"Blind man's buff," said the Saint's cheery voiced, out of the darkness. "Isn't it fun?"

Then Simon heard a sound from the door on his left, and whirled the beam round. The door had opened and closed again, and now Professor Bernhard Raxel stood with his back to it, and in his hand was an automatic pistol with a silencer screwed to the muzzle.

Raxel fired six times all round the light, and if was quite certain that in whatever contorted position Simon Templar had been holding that torch one of the bullets would have found its mark. But Templar was not holding the torch at all; and when Raxel's automatic was empty Simon struck a match and revealed himself in the opposite corner of the room--revealed, also, the electric torch lying on its side on the table where he had put it down.

"That's a new one on you, I'll bet!" said the Saint.

He lighted the lamp, put on his dressing gown, and ostentatiously dropped his gun into a pocket. Tope looked inquiringly at the Professor, and Taxel shook his head.

"You can go, Basher."

"You can go also, Raxel," said the Saint "It's two o'clock in the morning, and I want to get some sleep. Run away, and save up your little speech for breakfast,"

Raxel inclined his head.

"To-night was intended to be a warning to you," he said. "It was purely on the spur of the moment that I resolved to turn the warning into a permanent prohibition. It was clever of you to think of leaving your torch on the table. It is even flattering to remember that you did me the honour of crediting me with having heard before of the time-honoured device of holding the torch at arm's length away from you. But next time I may be a little cleverer than you."

"There won't be a next time" said the Saint. "You ought to know that it was a fool thing to do, to come to my room and try to put me out to-night, but it was no more than I expected. Now be sensible about it, sonny boy. I've got a little more to learn about you yet, and so you can carry on until I've learned it. But you can't kill me, and you needn't think I'm afraid of being killed. You made a bad break when you overlooked the railway ticket to Llancoed in Henley's wallet. That makes you hop!"

"You're talking in riddles," said Raxel coldly.

"You know the answer to 'em," said Simon. "I could run you in now for attempted murder, but I'm not going to because I want you for something much bigger. I'm going to give you just enough rope to hang yourself. Meanwhile, you will leave me alone. Everyone at Scotland Yard knows that I'm here and you're here, and if I happen to die suddenly, or do a mysterious disappearance, they'd have you in about two shakes of a sardine's trailing edge. Now get out--and stay out."

Raxel went to the door.

"And finally," Simon called after him, as a parting shot, "tell Basher not to put any more butyl in my beer. It kind of takes the edge off my thirst!"

The Saint breakfasted alone the next morning, but he waited about the inn for some time afterwards in the hope of seeing the girl. Crantor and Marring came down, and the cheerful "Good-morning" with which he greeted each of them was replied to in a surly mutter. Raxel followed, and remarked that it was a nice day. The Saint politely agreed. But the girl did not come down, and half an hour later he saw Basher bearing a tray upstairs, and gave it up and went out. His walk did not seem so satisfying to him that morning as it had the previous afternoon, for he was honestly worried about his first visitor of the night before. He made a point of being late for luncheon, but although the three men were sitting at their usual table (the Saint found that a separate table had been prepared for himself) the girl was not with them. He took his time over the meal, having for the moment no fear that his food might have been tampered with, and sat on for an hour after the other three had left, but Betty Tregarth failed to make an appearance.

When he had at last been compelled to conclude that she was lunching as well as breakfasting in her room, he went upstairs to his own room to think things out. There, as, soon as he opened the door, a scene of turmoil met his eye. The suitcase he had brought was open on the floor, empty, and all its contents were strewn about the place in disorder. The search had been very comprehensive--he noticed that even the lining of the bag had been ripped out.

"Life is certainly very strenuous these days," sighed the Saint mildly, and began to clear up the mess.

When he had finished, he lighted the fire and sat down in a chair beside it to smoke a cigarette and review the situation.

He ended up exactly where he had started, for everything there was to say had been said at two o'clock that morning. His entry had been staged with a deliberate eye to its effect--it would have been practically impossible to pretend to be an entirely innocent tourist for long, in any case, even if the first man he met had not put into his head the old trick of posing as a detective. And if he had to introduce himself flatly as a detective, the obvious course was to do it with a splash, and the Saint was inclined to congratulate himself on having made a fairly useful splash, as splashes go. But there it ended. Having made his splash he could only sit tight and wait.

Simon Templar was prepared to back himself against all comers in a patient-waiting competition. That decided, he raked some magazines out of his bag and sat down to read.

At half-past seven he washed, brushed his hair carefully, and went down to dinner full of hope, But once again he was unrewarded by a glimpse of the mysterious Betty Tregarth.

He sat out the other three, but they rose and left the table at last, and the girl had not joined them. The Saint stopped Raxel as he passed on his way to the door.

"I hope you have not suffered a bereavement." he said solicitously.

Raxel seemed puzzled,

"Miss Tregarth," explained the Saint,

"You mean my secretary?" said Raxel. "No, she has not been with us today."

A flicker of hope fired up deep down inside Simon Templar.

"Unfortunately," volunteered Raxel smoothly, "she has been indisposed. Nothing serious--a severe cold, with a slight temperature--but in this weather I thought it advisable to keep her in bed."

Simon watched the three men go with mixed feelings. The Professor had been just a little too aggressively plausible. His manner had indicated quite clearly that whether Simon Templar chose to believe that Betty Tregarth was indisposed or not, his interest in her was not appreciated and would be discouraged.

Not that that worried the Saint. When he went up to bed that night he made a careful search of the more obvious hiding places in his room, and found what he had expected to find, tucked into the pocket of his pajama-coat. It was a rough plan of the upper part of the house, and each room was marked to indicate the occupant. One room was marked with a cross, and against this was a scrawled note:

Kept locked. R., M., and C. go in occasionally. T. is there nearly all day.

The Saint studied the plan until all its details were indelibly photographed on his brain, and then dropped it on the fire and watched it burn. Then he went to bed.

He woke up at four o'clock, got up, and dressed. He slipped his automatic into his hip pocket, took his torch in his hand, opened the door silently, and stole out into the corridor.

6

His first objective was the room which had been marked T on the plan. Trying the handle with elaborate precautions against noise, he found, as he had expected, that the door was locked. But the locks on the doors were old-fashioned and clumsy, as he had discovered by some preliminary experiments in his own room, and it only took him a moment to open the lock with a little instrument which he carried. He passed in, and closed the door softly behind him. The ray of his torch found the bed, and he stole across and roused the girl by shining the light close to her eyes. She stared, and the Saint switched out the light and clapped a hand swiftly over her mouth.

"Don't scream!" he whispered urgently in her ear. "It's only me--Smith."

She lay still, and Simon took his hand from her lips and switched on the torch again.

"Talk in a whisper," he breathed, and she nodded understandingly. "Listen--have you really been ill?"

She shook her head.

"No. They're keeping me here--I was caught coming back from your room last night. How did you get in?"

Simon gave her a glimpse of the skeleton key which he had spent part of the afternoon twisting out of a length of stout wire.

"Have you thought of getting away?" he asked. "I"ll smuggle you out now, if you care to try it."

"It's no good," she said.

Simon frowned.

"You're being kept here a prisoner, and you don't want to escape?" he demanded incredulously. ^ "I'm not a prisoner," she replied. "It's just that they found out I'd got enough humanity in me to risk something to save you. If you went away I'd be free again at once."

"And you'd rather stay here?"

"Where could I go?" she asked dully.

Instantly he was moved to pity. She seemed s absurdly young, like a child, lying there.

"Haven't you any--people?"

"None that I can go back to," she said pitifully, desperately. "You don't know how it is."

"I guess I do," said the Saint gently, even if he was wrong. "But maybe I could find you some friends who'd help you."

She smiled a little.

"It wouldn't help," she said. "It's nice of you, but I can't tell you why it's impossible. Go on with what you've got to do, if you're too reckless to get out while there's time. Don't think anything more about me, Mr. Smith."

"Simon."

"Simon."

"I never knew how revolting 'Mr. Smith' sounded until you said it just now," he remarked lightly, but he was not thinking of trivialities.

Presently he said:

"There's another room I was meaning to visit tonight, but maybe you can save me the trouble. I'm told it's kept locked, but you spend the best part of the day there. What's inside?"

Her eyes opened wide, and she shrank away from him.

"You can't go in there!"

"I hope to be able to," said the Saint. "The little gadget that let me in here--"

"You can't! You mustn't! If Raxel knew that you knew what's in there he'd take the risk--he'd kill you!"

"Raxel need not know," said the Saint. "I shall try not to advertise the fact that I'm going in there, and I shan't talk to him about it afterwards--unless what I find in there is good enough to finish up this little excursion. Anyhow," he added, watching her closely, "what can there be in that room that you can spend every day with, and yet it would be fatal for me to see it?"

"I can't tell you . . . but you mustn't go!"

Simon looked straight at her.

"Betty," he said, "as I've told you before, you're heading for trouble. I've heard of real tough women who looked like angels, but I've never really believed in them. If you're that sort, I'll eat the helmet off every policeman in London. I don't know why you're in this, but even if you are as free as you say, you don't seem to be enjoying it. I'm giving you a chance. Tell me everything you know, help me all you can, and when the crash comes I'll guarantee to see you through it. You can take that as official."

She moved her head wearily.

"It's useless."

"You mean Raxel's got some sort of hold over you?"

"If you like."

"What is it?"

"I can't tell you," she said hopelessly.

The Saint's mouth tightened.

"Very well," he said. "On your own head be it. But remember my offer--it stays open till the very last moment."

He rose, and found her hand clutching his wrist.

"Where are you going?" she asked frightenedly.

"To unlock that door, and find out what's in this mysterious room," said the Saint, a trifle grimly. "I Ji^think I told you that before,"

"You can't. These locks are easy, but there's a special lock on that door."

"And right next door is an empty room, and there's nobody else but myself on that side of the house. Also, there's plenty of ivy, and it looks pretty strong to me. I don't think the window will keep me waiting outside for long,"

He disengaged her hand, and stepped away a little so that she could not grab him again.

"I'll lock your door when I go out," he said.

He went out, and she had not tried to call him back. It was the work of a few moments only to relock the door from the outside, and then he stole across the corridor to the door of the room which he had marked down because of its window, which was separated by no more than a couple of yards from the window of the locked room.

The ivy, as he had guessed, was strong; and as he had said, there was no one but himself sleeping on that side of the house, so that the noise he made was of no consequence. Better still, the Professor, when fitting the special lock to the door of the mystery room, had clearly overlooked the possibilities that the ivy-covered walls presented to an active young man, and the catch of the window was not even secured.

Simon slid up the sash cautiously and slithered over the sill. Then he switched on his torch, and his jaw dropped.

The centre of the room was occupied by a rough wooden bench, and on this was set up a complicated arrangement of retorts, condensers, aspirators, and burners. They seemed to form a connected chain, as if they were intended for the distillation of some subtle chemical substance which was submitted to various processes of blending and refinement during the course of its passage through the length of the apparatus. The chain terminated in a heavy cylinder such as oxygen is supplied in.

Simon studied the arrangement attentively; but he was no chemist, and he could make nothing of it. In his cautious way, he decided not to touch any of the components, for he appreciated that any chemical process which had to be surrounded with so much secrecy might possibly be pregnant with considerable danger for the ignorant meddler, and the association of Bernhard Raxel with the mystery would not have encouraged anyone to imagine that all those elaborate precautions had been taken to protect the secret of the manufacture of some new kind of parlour fireworks to amuse the children. But the Saint did take the liberty of peering closely at the apparatus, and the result was somewhat startling--so startling that it was some time before he was in a condition to pass on to the examination of the rest of the room.

On another bench, against one wall, was a row of glass bottles, unlabelled, containing an assortment of crystals, powders, and liquids, none of which had an appearance with which the Saint was familiar.

This, then, was the secret. A comprehensive tour revealed nothing more, and Simon, his objective accomplished, prepared to go. He lighted a cigarette and hesitated over his departure for a few moments, but he could think of nothing that a longer stay might achieve, and presently he accepted the inevitable with a shrug. Yet that delay had certain consequences--he was so absorbed with his problem that he did not visualize those consequences that night.

He returned to his own room as stealthily as he had left it, but the house remained shrouded in unbroken silence. The Saint's careful and expert examination had revealed a neat and inconspicuous burglar alarm attached to the door of the locked room. This, he had divined immediately, worked a buzzer under Raxel's own pillow, and therefore Raxel would have no fear that the Saint would be able to make an attempt to discover his secret without automatically calling the attention of the whole house to his nocturnal prowling. In which comfortable belief Professor Bernhard Raxel was beautifully and completely wrong.

Simon climbed into bed, and for the first time in his life failed to fall asleep immediately. He wanted to know what sinister secret lay behind the mysterious laboratory in that house, and most of all he wanted to know why Betty Tregarth should spend most of her time there. Betty Tregarth wasn't likely to be a willing associate of a man like the Professor --he was ready to swear to that. Was it possible that she had some special knowledge of chemistry, and had been blackmailed or coerced into assisting the Professor? . . . And then Simon Templar suddenly remembered the curious feeling that had come over him when he was peering at the apparatus in the locked room, and gasped aloud in a blinding blaze of understanding.

7

He was up early next morning, and the first thing he did was to go down to the village post office. He got a call through to London, to a friend who could help to answer some of the questions that were bubbling through his brain. And what he heard fascinated him.

It was on his way back to the Beacon that he suddenly recalled a detail of his delay the previous night, and therefore the immediate development failed to surprise him.

He had just finished breakfast when Raxel, Marring, and Crantor entered the dining room, and Simon saw at once from their bearing that they had already made an interesting discovery. Raxel came straight over to his table and the other two followed.

'' Good-morning,'' said the Saint, in his cheerful way.

"Good-morning, Mr. Smith," said the Professor. "I am sorry to hear that you walk in your sleep."

Simon looked blank.

"So am I," he said. "Do I?"

"I think so," said the Professor, and an automatic pistol showed in his hand. "Please put your hands up, Mr. Smith--I have just seen your cigarette ash on the floor of the laboratory."

Simon rose, yawning, with his arms raised.

"Anything to oblige," he murmured. "Have you put it under the microscope and discovered the brand of tobacco?"

"That is not what is puzzling me just now," said the Professor blandly. "Search him, Marring. We have already ransacked your room, Mr. Smith, and the letter which I was expecting to find was not there, so that if you have written it, it is likely to be on your person."

Simon submitted to the search without protest, and smiled at the look of savagely restrained consternation that broke momentarily through Raxel's mask of suavity when the search proved fruitless.

"Rather jumping to conclusions, weren't you?" the Saint suggested mildly.

Basher Tope stood in the doorway.

"I saw him go out before breakfast," said Tope clamorously. "He went down to the village. He must have used the telephone."

For a moment Simon thought Raxel would shoot, and keyed himself up for a desperate grab at the gun the Professor carried. But with a tremendous effort the man controlled himself, and the Saint

smiled again.

"That's where you're stung, isn't it, dear one?" he drawled. "And now let me tell you the tragic story of the mutilated onion, which never fails to melt the iciest eye. Or are tears a tender subject with you?"

The Professor shrugged, and bowed gracefully, but his eyes were flaming with fury.

"It is certainly your point, Mr. Smith," he said in an icily level voice.

Without another word he turned and went on to his own table, the other two following, and then Simon knew that the hours in which he would be able to bet on remaining at the Beacon in safety were numbered.

Immediately the three men were seated, a buzz of low-voiced guttural argument broke out. Both Crantor and Marring seemed to be advancing suggestions. They spoke in a language which was included in the Saint's extensive repertoire, and he could follow the whole of their discussion. From the glances of baffled hate that were flung in his direction from time to time, he reckoned that he had been more popular in his day than he was at that moment.

Raxel listened to the incoherent babbling of the other two men for some time with ill-concealed impatience; and then he silenced them with a wave of his hand.

"Horen Sie zu," he said, with a note of incontestable command in his voice, and spoke a few rapid, decisive sentences.

Out of these sentences Simon caught one word. The word was toten, and it did not require a German scholar to grasp the general idea. "Wir mussen ihn toten," Raxel had said, or words to that effect.

"So at last they've decided to kill me," thought the Saint, eating toast and marmalade. "Presumably my demise will be arranged at the earliest possible opportunity. Well, that means I've got them on the hop at last!" '

However, the thought failed to disturb him visibly, and in a few moments he rose and left the room. Betty Tregarth had not put in an appearance, but he had not expected that, and so he was not disappointed. The venomous eyes of the ptber three men followed him out.

In the parlour he found a tall, lean-limbed man wielding a broom.

"Morning, Dun," said the Saint.

The man turned a leathery face towards him and grinned.

"Morning, Saint."

"How are things?"

Duncarry grinned.

"O.K. so far. I haven't heard or seen anything to speak of--I don't think they're sure of me yet. You told me to lie low, so I haven't been nosing around at all."

"That's right," said the Saint. "Keep on being quiet. I've done all the nosing that need be done. But keep your eyes skinned. There's going to be trouble coming to me soon, I gather, and it's coming good and fast. So long!"

He drifted away.

There seemed to be no point in hanging about the inn that morning, and he decided to walk down to the George and have a drink. In the bar he remembered the ship which was anchored opposite the Beacon, and mentioned it to the proprietor.

"I think it belongs to one of the gentlemen up the road," that mine of local gossip informed him. "Gentleman of the name of Crantor. It came in here about a fortnight ago, and the crew all drove away in a car. I don't think there's anybody on board now.

"There's smoke comes up from her funnel," Simon pointed out, "You can't keep a fire going without somebody to look after it."

"Maybe there's a man or two just looking after the ship. Anyway, half a dozen men drove away with Crantor the day the ship came in, and he came back alone. One of the boys did ask what the ship was for--we don't get ships like that in here so often that people don't talk about it. That was in the days when some of the boys used to go up to the Beacon for their drinks, before the new boss there got so rude to them that nobody could stand it any longer. I think it was Bill Jones who asked what the ship was doing. Mr. Raxel said they were working on a new invention--a new sort of torpedo or something--and they were going to use the ship for trying it out at sea. That might easily be true, because about a month ago a lorry came in and delivered a lot of stuff at the Beacon, and the drivers had a drink here on their way out of the village. Chemistry apparatus it was, they said, and Raxel ordered it."

The Saint nodded vaguely; and then suddenly he stiffened. The proprietor also listened. That sort of thing is infectious.

Simon went over and looked out of the window. His ears had not misled him--a rickety Ford truck was crashing down the street. It stopped outside the door of the George, and two men came in and walked up to the counter.

"Couple o' quick halves, mate," ordered one of them.

They were served. The drinks were swallowed quickly. They seemed to be in a hurry.

"Got a rush order," one of them explained. "A couple of boxes to get to Southampton to catch a boat that's sailing to-morrow morning, and all luggage has got to be on board to-night. Can you tell us where the Beacon is?"

"Drive on to the end of the road, and turn to your right," said the Saint. "You'll find it on your right, about three hundred yards up. What ship are these boxes going to?"

"Couldn't tell you, mate. All I know is that we've got to get them to Southampton by nine o'clock tonight. Cheerio!"

They went out, and after that the publican felt that he had lost his audience, for the Saint was noticeably preoccupied.

Half an hour later, the lorry clattered past the window again, and Simon followed its departure with a thoughtful eye.