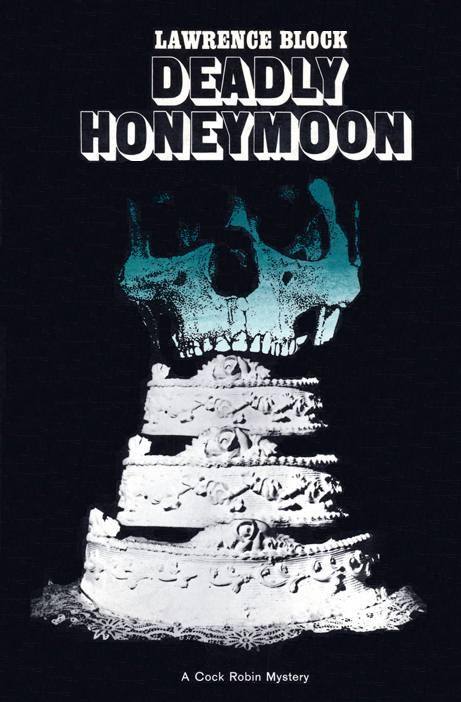

Lawrence Block

Deadly Honeymoon

For Don Westlake

Chapter 1

Just east of the Binghamton city limits he pulled the car off the road and cut the motor. She leaned toward him and he kissed her. He said, “Good morning, Mrs. Wade.”

“Mmmm,” she said. “I think I like my new name. What are we stopping for, honey?”

“I ran out of gas.” He kissed her again. “No, they gimmicked the car. Shoes and everything. You didn’t notice?”

“No.”

He got out of the car and walked around the back. Four old shoes trailed from the license-plate mounting. On the lid of the trunk someone had painted JUST MARRIED in four-inch white letters. He got down on one knee and picked at the knots in the shoelaces. They were tight. The car door opened on her side and she got out and came back to watch him. When he looked up at her she was starting to laugh softly.

“I didn’t even notice it,” she said. “Too busy ducking rice. I’m glad we got married in church. Dave, imagine driving all through Pennsylvania with the car like that! It’s good you noticed.”

“Uh-huh. You don’t have a knife handy, do you?”

“To defend my honor? No. Let me get it. I have long fingernails.”

“Never mind.” He straightened up, the shoes in hand. He grinned at her. “Those crazy guys,” he said. “What are we supposed to do with these?”

“I don’t know.”

“I mean, is it good luck to keep them?”

“If the shoe fits—”

He laughed happily and tossed the shoes into the underbrush at the side of the road. He unlocked the trunk, hauled out a rag, and wiped at the paint on the trunk lid. It wouldn’t come off. There was an extra can of gasoline in the trunk, and he uncapped it and soaked the rag with gas. This time the paint came off easily. He wiped the trunk lid dry with a clean rag to protect the car’s finish, then tossed both rags off to the side of the road and slammed the trunk shut.

She said, “I didn’t know you were a litterbug.”

“You can’t carry them in the trunk, not soaked with gas. They could start a fire.”

“That’s grounds for an annulment, you know.”

“Starting a fire?”

“Concealing the fact that you’re a litterbug.”

“Want an annulment?”

“God, no,” she said.

She had changed from her wedding dress to a lime-green sheath that was snug on her big body. Her hair was blond, shoulder length, worn pageboy style with the ends curled under. Her eyes were large, and just a shade deeper in color than the dress. He looked at her and thought how very beautiful she was. He took a step toward her, not even conscious of his own movement

“Dave, we’d better get going.”

“Mmmm.”

“We’ve got three weeks. We waited this long, we can wait two more hours. And this is an awfully public place, isn’t it?”

Her tone was not quite as light as her words. He turned from her. Cars passed them on the highway. He grinned suddenly and got back into the car. She got in on her side and sat next to him, close to him. He turned the key in the ignition and started the car and pulled back onto the road.

From Binghamton they rode south on 81, the new Penn-Can Highway. Jill had a state map spread open on her lap and she studied it from time to time but it was hardly necessary. He just kept the car on the road and held the speed steady between sixty and sixty-five. The car was a middleweight Ford, the Fairlane, last year’s model. It was the second week in September now and the car had a shade less than fifteen thousand miles on it.

They crossed the Pennsylvania state line a few minutes after noon. At twelve-thirty they left Route 81 at a town called Lenox and cut southeast on 106 through Carbondale and Honesdale. The new road was narrower, a two-laner that zigzagged across the hills. They pulled into an Esso station in Honesdale and Jill had a chicken sandwich at a diner two doors down from the station. He had a Coke and left half of it.

A few miles further on, at Indian Orchard, they left 106 and continued south on U.S. 6. They were at Pomquit by a quarter to two. Pomquit was at the northern tip of Lake Wallenpaupack, and their lodge was on the western rim of the lake, half a dozen miles south of the town. They found it without stopping for directions. The lodge had a private road. They followed its curves through a thick stand of white pine and parked in front of a large white Victorian house bounded on three sides by a huge porch. They could see the lake from where the car was parked. The water was very still, very blue.

Inside, in the office, a gray-haired woman sat behind a desk drinking whiskey and water. She looked up at them, and Dave told her his name. The woman shuffled through a stack of four-by-six file cards and found their reservation.

“Wade, David. You wanted a cabin, is that right?”

“That’s right.”

“Honeymooners, I guess, and I don’t blame you. Wanting a cabin, that is. Rooms in the lodge are nice but you don’t get the privacy here you would be getting in a cabin. It’s an old house. Sounds carry. And privacy is important, God knows. On a honeymoon.”

Jill was not blushing. The woman said, “You picked a good time of the year now. What with the lake and the mountains it stays pretty cool here most of the time, but this year July and August got pretty hot, pretty hot. And on a honeymoon you don’t want it to be too warm. But it’s cooled off now.”

She passed the card to him. On a dotted line across the bottom he wrote, “Mr. and Mrs. David Wade,” writing the double signature with an odd combination of pride and embarrassment. The woman filed the card away without looking at it. She gave him a key and offered halfheartedly to show them where the cabin was. He said he thought they could find it themselves. She told him how to get there, what path to take. They went back to the car and drove along a one-lane path that skirted the edge of the lake. Their cabin was the fourth one down. He parked the Ford alongside the cabin and got out of the car.

Their suitcases — two pieces, matching, a gift from an aunt and uncle of his — were in the back seat. He carried them up onto the cabin’s small porch, set them down, unlocked the door, carried them inside. She waited outside, and he came back for her and grinned at her.

“I’m waiting,” she said.

He lifted her easily and carried her over the threshold, crossed the room, set her down gently on the edge of the double bed. “I should have married a little girl,” he said.

“You like little girls?”

“I like big blondes the best. But little girls are easier to carry.”

“Oh, they are?”

“It seems likely, doesn’t it?”

“Ever carry any?”

“Never.”

“Liar,” she said. Then, “That drunken old woman has a dirty mind.”

“She wasn’t drunk, just drinking. And her mind’s not dirty.”

“What is it?”

“Realistic.”

“Lecher.”

“Uh-huh.”

He looked at her, sitting on the edge of the bed, their bed. She was twenty-four, two years younger than he was, and no man had ever made love to her. He was surprised how glad he was of this. Before they met he had always felt that it wouldn’t matter to him what any woman of his had done with other men before their marriage, but now he knew that he had been wrong, that he did care, that he was glad no one had ever possessed her. And that they had waited. Their first time would be now, here, together, and after the wedding.

He sat down next to her. She turned toward him and he kissed her, and she made a purring sound and came up close against him. He felt the sweet and certain pressure of her body against his.

Now, if he wanted it. But it was the middle of the afternoon and sunlight streamed through the cabin windows. The first time should be just right, he thought. At night, under a blanket of darkness.

He kissed her once more, then stood up and crossed the small room to look out through the window. “The lake’s beautiful,” he said easily. “Want to swim a little?”

“I love you,” she said.

He drew the shades. Then he went outside and closed the door to wait on the porch while she changed into her bathing suit He smoked a cigarette and looked out at the lake.

He was twenty-six, two years out of law school. In a year or so he would be a junior partner in his father’s firm. He was married. He loved his wife.

A heavyset man waved to him from the steps of the cabin next door. He waved back. It was a good day, he thought. It would be a good three weeks.

Jill was a better swimmer than he was. He spent most of his time standing in cool water up to his waist, watching the perfect synchronization of her body. Her blond hair was all bunched up under her white bathing cap.

Later she came over to him and he kissed her. “Let’s go sit under a tree or something,” she said. “I don’t want to get a burn.”

“Jesus, no,” he said. “Sunburned on your honeymoon—”

“You sound like that drunken old woman.”

He spread a blanket on the bank and they sat together and shared a cigarette. Their shoulders were just touching. There were small woodland noises as a background, and once in a while the faraway sound of a car on the highway. That was all. He dried her back and shoulders with a towel and she took off her bathing cap and let her hair spill down.

Around five the man from the cabin next door, the one who had waved, came over to them carrying three cans of Budweiser. He said, “You kids just moved in. I thought maybe you’d have a beer with me.”

He was between forty-five and fifty, maybe thirty pounds overweight. He wore a pair of gray gabardine slacks and a navy-blue open-necked sport shirt. His forearms were brown from the sun. He had a round face, the skin ruddy under his deep tan.

They thanked him, asked him to sit down. They each took a can of beer. It was very cold and very good. The man sat down on the edge of their blanket and told them that his name was Joe Carroll and that he was from New York. Dave introduced himself and Jill and said that they were from Binghamton. Carroll said he had never been to Binghamton. He took a long drink of beer and wiped his mouth with the back of his hand. He asked them if they were staying long.

“Three weeks,” Dave said.

“You picked a good spot. We been having good weather, cooler now than it was, with sun just about every day. A little rain the week before last, but not too much.”

“Have you been here long, Mr. Carroll?” Jill asked.

“Joe. Yeah, most of the summer. I’m just here by myself. You can go crazy for somebody to talk to. You kids been married long?”

“Not too long,” Dave said.

“Any kids?”

“Not yet.”

Carroll looked off at the lake. “I never got married. Almost, once, but I didn’t. I’ll tell you the truth, I never missed it. Except for kids. Sometimes I miss not having kids.” He finished his beer, held the can in one hand and looked at it. “But what with business and all, you know, a man stays pretty busy.”

“You’re in business.”

“Construction.” He waved a hand in the general direction of the lake. “Out on Long Island, Nassau County, the developments. We built oh, a whole lot of those houses.”

“Isn’t this your busy season?”

He laughed shortly. “Oh, I’m out of it now, for the time being.”

“Retired?”

“You could call it that” Carroll smiled as if at a private joke. “I may relocate,” he said. “I might pull up stakes, find a better territory.”

They made small talk. Baseball, the weather, the woman who managed the lodge. Carroll said she was a widow, childless. Her husband had died five or six years back, and she was running the place on her own and making a fairly good thing of it. He said she was a minor-league alcoholic, never blind drunk but never quite sober. “The hell,” he said, “what else has she got, huh?”

He told them about a steak house down the road where the food wasn’t bad. “Listen,” he said, “you get a chance, drop over to my place. We’ll sit around a little.”

“Well—”

“There’s more beer, I got a hot plate for coffee. You know gin rummy? We could play a few hands and pass the time.”

They ate at the steak house that Carroll recommended. It was just outside of Pomquit. The steaks were thick, the service fast, and the place had the atmosphere of a Colonial tavern, authentic without being intrusive. There was an old copper kettle hanging from a hook on one wall, and Jill wanted it. Dave tried to buy it but the manager said it wasn’t for sale. They stood outside for a few minutes after dinner and looked up at the moon. It was just a little less than full.

“Honeymoon,” she said. “Keep a-shining in June. But it’s September, isn’t it?”

“The drunken old woman said it’s better this way. You don’t want it too hot on a honeymoon.”

“Oh, no?”

“Now who’s the lecher?”

“I’m shameless,” she said. “Let’s go back to the cabin. I think I love you, Mr. Wade.”

On the slow ride home she said, “I feel sorry for him.”

“Who, Carroll?”

“Yes. He’s so lonely it’s sad. Why would he pick a spot like this to come to all alone?”

“Well, he said the fishing—”

“But all alone? There are livelier spots where the fishing must be just as good as it is here.”

“Listen, he just sold his business. Maybe he’s got problems.”

“He should have gotten married,” she said. She rolled down her window, let her arm hang out, tapped against the side of the Ford with her long fingernails. “Everybody should be married. Maybe he’ll marry the drunken old woman and she won’t drink any more and they can manage the lodge together.”

“Or tear it down and build up a tract of ugly little split-levels.”

“Either way,” she said. “Everybody should be married. Married is fun.”

“You’re incorrigible,” he said.

“I love you.”

He almost missed the turnoff for the lodge. He cut the wheel sharply to the left and the Ford moved onto the private road. He drove past the lodge itself and followed the path back to the cabin. The lights were on in Joe Carroll’s cabin. She said, “Mr. Carroll wanted us to stop in for coffee.”

“Some other time,” he said.

He parked the car and they walked slowly together up the steps to the cabin. He unlocked the door, turned on the light. They went inside and he closed the door and turned the bolt. She looked at him and he kissed her and she said, “Oh, God.” He turned off the light. The room was not completely dark. A little light came in, from the moon on one side, from Carroll’s cabin on the other.

He held her and she threw her arms around his neck and kissed him. She was a tall girl, a soft and warm girl. His. He found the zipper of her dress and opened it partway and rubbed her back with his fingers.

Outside, a car drew up slowly. The motor died and the car coasted to a stop.

She stiffened. “There’s somebody coming,” she said.

“Not here.”

“I heard a car—”

“Probably some friends of Carroll’s.”

“I hope it’s not some friends of ours,” she said, her voice almost savage. “I hope this isn’t some idiot’s idea of a joke.”

“They wouldn’t do that.”

“I just hope not.”

He let go of her. “Maybe I’d better check,” he said.

The bolt on the door was stuck. He wrestled it open, turned the doorknob, opened the door, and stepped outside onto the porch. Jill followed him, stood at his side. The car, empty now, was parked in front of their cabin by the side of the Ford. It was a big car, a Buick or an Olds. It was dark, and he couldn’t be sure of the color in the half-light. Maybe black, maybe maroon or dark green. The two men who had been in the car were walking toward Carroll’s cabin. They were short men and they wore hats and dark suits.

He turned to her. “See? Friends of Joe’s.”

“Then why didn’t they park at his cabin?” He looked at her. “They drove right past his cabin,” she said, “and they parked here, and now they’re walking back. Why?”

“What’s the difference?”

He took her arm and started to lead her inside again. But she shrugged and stayed where she was. “Just a minute,” she said.

“What’s the matter?”

“I don’t know. Wait a minute, Dave.”

They waited and watched. Carroll’s cabin was thirty or forty yards from theirs. The men covered the distance without making any noise. One of Carroll’s porch steps creaked, and just after the creak they could hear movement inside the cabin. The men did not knock. One of them yanked the door open and the other sprang inside. The man on the porch had something in his hand, something that light glinted off, as though it were metallic.

Sounds came from the cabin, sounds that were hard to make out. Then Joe Carroll walked out of the cabin and the man who had remained outside said something to him in a low voice. They could see what he had in his hand now. It was a gun. The other man came out behind Carroll and he was holding a gun in Carroll’s back.

They stayed on the porch and they stayed quiet. It wasn’t real — that was all he could think, that it was not real, that it was a play or a movie and not something happening before them.

They heard Carroll’s voice, crystal clear in the still night air. “I’ll make it good,” he said. “I swear to God I’ll make it good. You tell Lublin I’ll make it good, Jesus, just tell him.”

The man behind him, the one jabbing him in the back with the gun, began to laugh quietly. It was unpleasant laughter.

“Oh, sweet Jesus,” Carroll said. His face was awful. “Listen, please, just a chance, just give me a chance—”

“Crawl,” the man in front said.

“What do you want me to—”

“Get down on your knees and beg, you bastard.”

Carroll sank to his knees. There were fallen leaves on the ground, and pine needles. He was saying something over and over again in a weak voice but they couldn’t quite make it out.

The man in front stepped forward and put the muzzle of his gun against Carroll’s head. Carroll started to whine. The man shot him in the center of the forehead and he shook from the blow and pitched forward on his face. The other man moved in and shot Carroll four times through the back of his head.

Jill screamed.

It wasn’t much of a scream. It broke off in no time at all, and it was neither very loud nor very high-pitched. But the two men in the dark suits heard it. They heard it and they looked up at the porch of the Wade cabin.

And came forward.

They stood, the four of them, in Carroll’s cabin. The small room was as neat as if no one had ever lived in it. There was a hot plate on an oak table, with a large jar of Yuban instant coffee beside it and a half-finished cup of coffee off to one side. The bed was neatly made.

The taller of the two men was called Lee. They knew this, but they did not know whether it was his first name or his last name. He was the one who had made Carroll crawl, the one who had killed him with the first shot in the forehead. Lee had large brown eyes and thick black eyebrows. There were three or four thin scars across the bridge of his nose. His mouth was a thin line, the lips pale. He was holding a gun on them now while the other man, whose name they had not heard yet, was systematically going through Carroll’s dresser drawers, taking everything out piece by piece, throwing everything on the floor.

“Nothing,” he said finally. “Just what was in the wallet.”

Lee didn’t say anything. The shorter man turned around and nodded toward Dave and Jill. He was heavier than Lee, with a thick neck and a nose that had been broken and imperfectly reset. He looked as though he might have played guard or tackle on some college’s junior varsity.

Now he said, “What about them?”

“They didn’t see a thing. They aren’t going to talk.”

“What if they do?”

“So? They don’t know a thing.”

“We won’t make any trouble,” Dave said. His voice sounded odd to him, as though someone else were pulling strings that moved his lips, as though someone else were talking for him.

They didn’t seem to have heard him. Lee said, “If they talk, it doesn’t matter. They talk to some hick cop and he writes it all down and everybody forgets it. They put it in some drawer.”

“We could make sure.”

“Just let us alone,” Dave said. Jill was next to him, breathing heavily. He looked at the gun in Lee’s hand and wondered whether they were going to die, now, in this cabin. “Just let us live,” he said.

“We kill ’em,” Lee said, “it makes too much stink. Him out there, that’s one thing, but you kill a couple of kids—”

“Leave ’em alone then?”

“Yeah.”

“Just like that?”

“I don’t like killing nobody without I get paid for it,” Lee said. “I don’t like throwing any in for free.”

The man with the broken nose nodded. He said, “The broad.”

“What about her?”

“She’s nice. Stacked.”

Dave said, “Now listen—”

They ignored him. “You want her?”

“Why not?”

The man called Lee smiled brutally. He stepped up to Jill and stuck the gun into her chest just below and between her breasts. “How about that,” he said. “You don’t mind a little screwing just to keep you alive, now, do you?”

Dave stepped out and swung at him. He threw a left, hard, not thinking, just reacting. The man called Lee stepped back and let the punch go over his shoulder. He reversed the gun in his hand and laid the side of the gun butt across Dave’s forehead. Dave took one more little step, a half-step, really, and fell to the floor.

His head was spinning. He got to one knee. The shorter man was pushing Jill toward Carroll’s bed. She was crying hysterically but was not fighting very hard. There was the sound of cloth ripping, Jill’s shrill scream above the tearing of the dress. He pushed himself up and rushed toward the bed, and Lee stuck out a foot and tripped him. He went sprawling. Lee stepped in close and kicked him in the side of the rib cage. He moaned and fell flat on his face.

“You better take it easy,” Lee said.

He got up again. He stood, wavering, and Lee set the gun down on the table. He moved as if he had all the time in the world. Dave stood there, staring dead ahead, and Lee moved in front of him and hit him in the pit of the stomach. He doubled over but he didn’t go down. Lee waited, and he straightened up, and Lee hit him twice in the chest and once in the stomach. This time he went down again. He tried to get up but he couldn’t. It was as though someone had cut all his tendons. He was awake, he knew what was happening, he just couldn’t move.

Jill had stopped crying. The shorter man finished with her and came over to them. He asked Lee whether Dave had tried to be a hero. Lee didn’t say anything. Then the shorter man said, “She was cherry. You believe that?” And he said it as though he had not known virgins still existed.

Lee said, “She ain’t now.” And took off his jacket and went to take the shorter man’s place with Jill.

She didn’t scream. She lay there, motionless, and Dave thought that they must have killed her. This time his legs worked, this time he got up. The shorter man hit him with the gun and pain split his skull in half. He went down. The world turned gray, and the gray darkened quickly to black.

Chapter 2

He never remembered going back to the cabin. He had vague memories of walking and falling down, walking and falling down, but they were as dim as vanished dreams. When he did come out of it, he was in their own cabin. He was lying on the bed and Jill was sitting in a chair looking down at him. She was wearing a beige skirt and a dark-brown sweater. Her face was freshly scrubbed, her lipstick unmarred, her hair neatly combed. There was a moment, then, when nothing made sense — the whole thing, Carroll and the two men and the beating and the violation of his wife, none of this could have happened.

But then he felt the pain in his own body and the dull ache of his head and he saw the discoloration over her right eye, masked incompletely by makeup. It had all happened.

“Don’t try to talk yet,” she said. “Take it easy.”

“I’m all right.”

“Dave—”

“I’m all right,” he said. He sat up. His head was perfectly clear now. The pain was still there, and strong, but his head was perfectly clear. He remembered everything up to the blow that knocked him out. The return from Carroll’s cabin to their own, that was lost, but he remembered all the rest in awful reality.

“We’ve got to get you to a doctor,” he said.

“I’m all right.”

“Did they—”

“Yes.”

“Both of them?”

“Both of them.”

“You’ve got to see a doctor, Jill.”

“Tomorrow, then.” She took a breath. “I think the police are over in... in the other cabin. I heard a car, someone must have called them. It took them long enough.”

“What time is it?”

“After ten. They’ll be coming over here, won’t they?”

“The police? Yes, I think so.”

“You’d better clean up. I tried to wash your face. Your head is cut a little. In two places, on top and behind your ear there.” She touched him, her hand light, cool. “How do you feel?”

“All right.”

“Liar,” she said. “Wash up and change your clothes, Dave.”

He went into the tiny bathroom and stripped down. There was no tub, just a shower. It was one of those showers in which you had to hold a chain down in order to keep the water running. He showered very quickly and thought about the two men and Carroll and about what they had done to Jill. At first his mind clouded with fury, but he stayed in the shower and the water rained down upon him, and he thought about it, forced himself to think about it. The fury did not go away. It stayed, but it cooled and changed its shape.

While he was drying himself off the bathroom door opened and Jill brought him clean clothes. After she had left he realized, oddly, that she had just seen him naked for the first time. He shrugged the thought away and dressed.

When he came out of the bathroom, the police were there. There were two tall thin men, state troopers, and there was one older man from the Sheriff’s Office in Pomquit. One of the troopers took their names. Then he removed his hat and said, “A man was murdered here tonight, Mr. Wade. We wondered if you knew anything about it.”

“Murdered?”

“Your neighbor. A Mr. Carroll.”

Jill drew in her breath sharply. Dave looked at her, then at the trooper. “We met Mr. Carroll just this afternoon,” he said. “What... happened?”

“He was shot four times in the head.”

Five times, he thought. He said, “Who did it?”

“We don’t know. Did you hear anything? See anything?”

“No.”

“Whoever killed him must have come in a car, Mr. Wade. We found tire tracks. There was a car parked right next to yours outside. That is your car, isn’t it? The Ford?”

“Yes.”

“Did you hear a car drive up, Mr. Wade?”

“Not that I remember.”

The man from the Sheriff’s Office said, “You would have heard it — it was right outside your window. And the shots, you would have heard them. Were you here all night?”

Jill said, “We went out for dinner.”

“What time?”

“We left about seven,” she said. “Seven or seven-thirty.”

“And got back when?”

“About... oh, half an hour ago, I guess. Why?”

The man from the Sheriff’s Office looked over at the troopers. “That would do it, then,” he said. “Carroll’s been dead at least an hour, the way my man figures it. Closer to two hours, probably. They must have gotten back just before we got the call, must have come right in without seeing the body. You wouldn’t see it from where the car’s parked, anyway. Just been back half an hour, Mr. Wade?”

“It may have been longer than that,” he said.

“As much as an hour?”

“I don’t think so. Maybe forty-five minutes at the outside.”

“That would do it, then. I guess you didn’t see anything, then, Mr. Wade. Mrs. Wade.”

He turned to go. The troopers hesitated, as though they wanted to say something but hadn’t figured out the phrasing yet. Dave said, “Why was he killed?”

“We don’t know yet, Mr. Wade.”

“He was a very pleasant man. Quiet, friendly. We sat outside this afternoon and had a beer with him.”

The troopers didn’t say anything.

“Well,” Dave said, “I don’t want to keep you.”

The troopers nodded shortly. They turned, then, and followed the man from the Sheriff’s Office out of the cabin.

It was midnight when the last earful of police was gone. They sat quietly for five or ten minutes. He stood up then and said, “We’re getting out of here tonight. You’d better start packing.”

“We’re leaving tonight?”

“You don’t want to stay here, do you?”

“God, no.” She reached out a hand. He gave her a cigarette, lit it for her. She blew out smoke and said, “They won’t be suspicious?”

“Of what?”

“Of us, if we leave so quickly. Without staying the night.”

He shook his head. “We’re newlyweds,” he said. “Newlyweds wouldn’t want to spend their wedding night next door to a murder.”

“Newlyweds.”

“Yes.”

“Wedding night. God, Dave, how I planned this night. All of it.”

He took her hand.

“How I would be sexy for you and everything. How I wouldn’t mind if it hurt because I love you so much.

Oh, and little tricks I read in one of those marriage manuals, I was going to try those tricks. And surprise you with my ingenuity.”

“Stop it.”

He got the suitcases and spread them open on the bed. They packed their clothes in silence. He put the clothes she had worn earlier and his own dirty clothes in the trunk and loaded the two suitcases in the back seat. She got in the car, and he went to the cabin and closed the door and locked it.

As they drove past the lodge, she said, “We didn’t pay. The old woman would want to be paid, for the one night.”

“That’s too fucking bad,” he said.

He turned left at the main road and drove to Pomquit. He passed through the town and took a road heading north. “It’s late and I don’t know the roads,” he said. “We’ll stop at the first motel that looks decent.”

“All right.”

“We’ll get an early start in the morning,” he went on. He was looking straight ahead at the road and he did not glance over at her. “An early start in the morning, figure out which route to take, all of that. They’re from New York, aren’t they?”

“I think so. Carroll said he was from New York. And they all had New York accents.”

He slowed the car. There was a motel off to the left, but the “No Vacancy” sign was lit He speeded up again.

“We’ll go to New York,” he said. “Well be there by tomorrow afternoon, Monday. We’ll get a room in a hotel, and we’ll find out who they are, the two of them. One of them is named Lee. I didn’t catch the other one’s name.”

“Neither did I.”

“We’ll find out who they are, and then we’ll find them and we’ll kill them, both of them. Then we’ll go back to Binghamton. We have three weeks. I think we can find them and kill them in three weeks.”

Up ahead, on the right, there was a motel. He slowed the car. As he pulled off the road he glanced at her face, quickly. Her jaw was set and her eyes were dry and clear.

“Three weeks is plenty of time,” she said.

Chapter 3

In the diner the waitress said, “Mondays, how I hate ’em. Give me any other day, but Monday, just never mind. Coffee?”

“One black, one regular,” he told her.

There were two men at the counter who looked like truckers and one who looked like a farmer. The waitress brought the coffee and he carried the two cups over to a table on the side. Some of the coffee in her cup spilled out onto the saucer. He took a napkin from the dispenser and wiped up the coffee. She added sugar, one level spoonful. He drank his straight black.

When the waitress came over he ordered toast and a side order of link sausages. Jill wanted a toasted English muffin, but the diner didn’t have any. The waitress said there would be some coming in around nine-thirty. Jill had a cheese Danish instead and managed to eat half of it.

He spread a road map on the table and studied it, marking a route with a pencil. She sipped her coffee and looked across the room while he traced the route they would take. By the time he was finished, she had drunk her coffee. He looked up and said, “This is how we’ll do it. We’re on 590 now. We take it to Ford — that’s just across the state line — and pick up 97. We go about five miles on 97 to Route 55. That’s at Barryville. Then 55 runs just about due north to something called White Lake, where we get 17B. Then we hook up with 17 at Monticello. That carries us all the way to the throughway at Exit 16, and then we just drive down into New York.”

“I never heard of those towns,” she said.

“Well, Monticello you’ve heard of.”

“I mean the others.”

He sipped his coffee, checked his watch with the electric clock over the counter. “Twenty to eight,” he said.

“Should we get going?”

“Pretty soon.” He got to his feet. “I’m having another cup of coffee,” he said. “How about you?”

“All right.”

He carried the two cups back to the counter. The waitress was busy telling one of the truckers what a terrible day Monday was. She was a heavyish woman with stringy hair. When she finished talking to the truck driver Dave got two fresh cups of coffee and carried them back to the table.

They passed through the town, a small one, and a sign told them to resume their normal speed. He bore down on the accelerator. The sun was bright on the road ahead. The sky had been overcast when they got up, but the clouds were mostly gone now.

“That was Forestine,” she said. “White Lake in three miles.”

“And then what?”

“Then right on 17B.”

He nodded. So far, in close to an hour of driving, they had talked only about the route and the road conditions. She had the road map open on her lap, the map with their route penciled in, and she told him when to slow down and where to turn. But most of the time passed in long silences. It was not for lack of things to say to each other, or because any distance had sprung up between them. Small talk did not fit and larger talk came hard.

The night before they had stayed at a motel called Hillcrest Manor. They slept in a double bed. After he checked in, they left their suitcases in the locked car and went inside. They undressed with the lights on, then he turned off the lights, and they got into the large bed. She took the side near the windows, and he had the side nearer to the door. He waited, and she came to him and kissed him once, on the side of the face. Then she went back to her side of the bed. He asked her if she thought she would be able to sleep and she said yes, she thought so. After about fifteen minutes he heard her easy rhythmic breathing and knew that she was sleeping.

He couldn’t fall asleep. The beating had tired him, and his body wanted sleep, but it didn’t work. He would manage to relax and would start drifting off and then the memory would come, racing in at his mind, and he would suck in breath and shake his head and sit up in the bed, his heart beating fast and hard. From time to time he got out of the bed and sat in a chair at the window, smoking a cigarette in the darkness, then putting out the cigarette and returning to bed.

Around four, he dozed off. At a quarter to six he heard a frightened yelp and was instantly awake. She lay on her back, her head on a pillow, her eyes closed, and she was crying in her sleep. He woke her up and soothed her and told her that everything was all right. After a few minutes she fell asleep again, and he got up and put clothes on.

Now he talked to her without looking at her, his eyes conveniently fixed on the road ahead. “When we get to Monticello,” he said, “you’re going to see a doctor.”

“No.”

“Why not?”

He looked at her. She was worrying her lip with her teeth. “I don’t want anyone, oh, touching me. Now. Examining me.”

“Is that all?”

“I just don’t want it. And if a doctor could tell anything, wouldn’t he have to report it? Like a gunshot wound?”

“I don’t know. But if they injured you—”

“They didn’t hurt me,” she said. “I mean, they didn’t do any damage. I checked, I know. There were no cuts or bleeding.” Her voice, flat until then, came alive again. “Dave, those policemen were stupid.”

“Why?”

“They figured it all out. The mess in Carroll’s cabin, the way everything was turned upside down. They think Carroll fought with his murderers and then they dragged him outside and shot him.”

“I didn’t even think about that. That’s what they figure?”

“They were talking outside, before you got out of the shower. Dave, they didn’t hurt me. I don’t have to see any doctor.”

“Well—”

“There wasn’t even that much pain,” she said. “The doctor I saw, before we were married—”

He waited.

“He told me about some exercises. To make it easier for us to—” She stopped, and he waited, and she caught hold of herself and started in again. “—to consummate our marriage.”

He kept his eyes on the road. He swung to the left, passed a station wagon, cut back to the right again. He looked at his hands on the steering wheel, the knuckles white, the fingers locked tight around the wheel. He moved his hands lower on the steering wheel so that she would not see them.

Suddenly he was grinning.

“Is something funny?”

“I was just picturing you,” he said. “Doing your exercises.”

He laughed then, and she laughed. It was the first time either of them had laughed since Carroll was murdered.

A little later he said, “There’s another reason you ought to see a doctor.”

“What’s that?”

“I don’t know how to say it well. Suppose you’re pregnant?”

She didn’t say anything.

“It’s no fun to think about,” he said. “But it could be. Jesus.”

“Oh, Dave—”

He slowed the car. “It’s nothing to worry about,” he said. “They can always do something about it. The legal question varies from state to state, but I know a dozen doctors who wouldn’t worry about the law. If a... rape victim is pregnant, she can get an abortion. There’s no problem.”

“Oh, God,” she said. “I didn’t even think. You’ve been worrying about this, haven’t you? All night, probably.”

“Well—”

“I’m not pregnant. I’m taking these pills, oral contraceptives. That was one of my surprises for you. The doctor gave me pills to take. Little yellow pills. I couldn’t possibly be pregnant.”

She began to cry then. He started to pull off the road but she told him to go on driving, that she would be all right. He went on driving, and she stopped crying. “Don’t worry about me,” she said. “I’m not going to cry any more, at all.”

They made good time. They stopped once on the road for gas and food and were in New York by twelve-thirty. They came in on the Saw Mill River Parkway and the West Side Drive. They took a room with twin beds at the Royalton, on West Forty-fourth Street. The doorman parked their car for them.

Their room was on the eleventh floor. A bellhop carried their luggage, checked the towels, showed them where their closets were, opened a window, thanked Dave for the tip, and left. Dave walked to the window. You couldn’t see much from it, just the side of an office building.

“We’re here,” he said.

“Yes. Have you spent much time in New York?”

“A couple of weekends during college. And then for six weeks two years ago. I was studying for the bar exams, and there’s a course you take just to cram for the bar. A six-week cram course. I stayed downtown at the Martinique and didn’t do a thing but eat and sleep and study. I could have been in any city for all the attention I paid to it.”

“I didn’t know you then.”

“No, not then. Do you know this city?”

She shook her head. “I have an aunt who lives here. A sister of my father’s. She never married, and she has a job in the advertising department for one of the big department stores. Had, anyway. I don’t know if she still does, I haven’t seen her in years. Name some department stores.”

“Jesus, I don’t know. Saks, Brooks Brothers—”

“She wouldn’t work at Brooks Brothers.”

“Well, I don’t know anything about department stores. Bonwit? Is there one called Bonwit?”

“It was Bergdorf Goodman. I remember now. We went to visit her, oh, two or three times. I was just a kid then. We didn’t see her very often because my mother can’t stand her. Do you think she might be a lesbian?”

“Your mother?”

“Oh, don’t be an idiot. My aunt.”

“How do I know?”

“I wonder. There was a lesbian in my dormitory in college.”

“You told me.”

“She wanted to make love to me. Did I tell you that, too?”

“Yes.”

“Everybody said I should have reported her, but I didn’t I wonder if Aunt Beth is a lesbian.”

“Call her up and ask her.”

“Some other time. Dave?” Her face was serious now. “I think we ought to figure out what we’re going to do first. How we’re going to find them, the two men. We don’t know anything about them.”

“We know a few things.”

“What?”

He had a notebook in his jacket pocket, a small loose-leaf notebook for appointments and memos. He sat down in an armchair and flipped the book open to a blank page. He took his pencil and wrote: “Joe Carroll.”

“They killed a man named Joe Carroll,” he said. “That’s a start” She nodded, and he said, “If that was his name.”

“Huh?”

“That was the name he gave us, and that was the name he used at the lodge. But he was running away, trying to hide. He might not have used his own name.”

“What did the men call him?”

“I don’t remember. I don’t think they called him anything. I couldn’t hear that much from where we were.”

“Wouldn’t the police know his real name?”

“The troopers?” He thought a minute. “He might have had some identification on him. They called him Carroll. They might have done that in front of us just to keep from confusing us, but maybe not Or maybe he wasn’t carrying any identification.”

“Or maybe they took his wallet with them.”

“Maybe.” He lit a cigarette. “But they would fingerprint him,” he said. “They would do that much automatically, and they would send his prints to Washington, to the FBI. If he’s ever been fingerprinted, then, his prints would be on file and they would get a positive identification of him.”

“How could we find out?”

“If he’s important, then it would be in the New York papers. If not, it would just be in the local papers. If Pomquit has a paper. Or one of larger cities around there. Scranton — I don’t know.”

“Can you get Scranton papers in New York?”

“Yes. There’s a newsstand in Times Square. I used to pick up Binghamton papers during that bar-exam stretch. The papers run late, but they would have them.”

In the notebook he wrote: “Scranton paper.”

He looked up. “Let’s take it from the top. Carroll, whatever his name is, said he was in construction. And semiretired.”

“He was probably just talking.”

“Maybe. People usually stay close to the truth when they lie. Especially when they’re lying just for the sake of convenience. Carroll wanted to be friendly with us, and he had to invent a story, not to keep anything from us, specifically, but because he couldn’t tell the truth without drawing the wrong kind of attention to himself. He was probably a criminal. I got that picture from the way he talked with the two of them.”

“So did I.”

“But I think he was probably a criminal with some background in the construction business. A lot of rackets have legitimate front operations. You know the cigar store across from the Lafayette?”

“In Binghamton?”

“Yes. It’s a bookie joint.”

“I didn’t know that.”

“It’s not exactly a secret. Everybody knows it, they operate pretty much in the open. Still, the place is a cigar store. They don’t have a sign that says ‘Bookie Joint,’ and the man who runs it tells people he runs a cigar store, not a bookie joint. It’s probably something like that with Carroll. He was probably in construction, or on the periphery of it, no matter what racket he may have had on the side.”

He was talking as much to himself as to her now. If they were going to find Lee and the other man, they would do it by reasoning from the few facts and nuances at their disposal.

“Carroll did something wrong. That was why the two of them came after him. He double-crossed somebody.”

“He said that he would make it good.”

He nodded. “That’s right. There was a name. Their boss, the one they work for. Carroll told them to tell the boss that he would make it good.”

On the notebook page he changed the first entry to read: “Joe Carroll — Construction.” Then he wrote: “Nassau County,” which was where Carroll had said he was in business.

Jill said, “They mentioned the boss by name. Or Carroll did.”

“I think Carroll did.”

“I can remember it. Just a minute.” He waited, and she closed her eyes and put her hands together, pressing the palms one against the other.

“Dublin,” she said.

“No, that’s not it.”

“Dublin, it was Dublin. Tell Dublin that I’ll make it good. No, that’s not right either.”

“It’s not what they said.”

“Lublin, maybe?”

“I don’t know.”

“Well, say the sentence for me. I think I can tell if I hear it, if you say it for me. Like a visual memory, I except different. Say the sentence the way he said it.”

“With Lublin?”

“Yes.”

He said, “‘Tell Lublin I’ll make it good.’”

“That’s it. I’m positive, Dave. Lublin.”

He wrote: “Lublin — Boss.”

“They worked for Lublin? Is that it?”

He shook his head. “I think he hired them. I don’t think they were regular... well, employees of his. They were paid to kill Carroll. And when one of them wanted to kill us, so that we wouldn’t be able to tell the police anything, the other said something about not killing anybody unless he was getting paid for it As if they had been specifically hired to kill Carroll, to do that one job for a set fee.”

“That was Lee who said that. I remember now.”

He wrote: “Hired Professional Killers. Lee.” He said, “I know one name — Lee. It could be his first name or his last name.”

“Or a nickname,” she said. “If his name is LeGrand, or something.”

“It could be anything. That was all he was called, wasn’t it? I didn’t hear him called anything else. And he didn’t call the other one anything.”

“No, he didn’t.”

He lit a fresh cigarette. He looked at the notebook, at the neat entries one beneath the other: “Joe Carroll — Construction. Nassau County. Scranton paper. Lublin — Boss. Hired Professional Killers. Lee.” He went to the window and looked across at the office building. He wanted to look out at the city but the building was in the way. There were eight or nine million people in the city, and he was looking for two of those millions, and he couldn’t even see the city itself. There was a building in the way.

“Dave.”

He turned. She was next to him, her hair brushing his cheek. He put an arm around her and she drew close. Her head settled on his shoulder. For a moment he had thought of those two, lost in that huge crowd, and that it was hopeless and ridiculous. But now his arm was around her, and he remembered what they had done to her and what they had taken from her and from him. He closed his eyes and pictured both men dead.

Chapter 4

He missed the out-of-town-newspaper stand on the first try. He passed it on the wrong side of the street and walked to Seventh Avenue and Forty-second, then got his bearings and retraced his steps. The stand was at Forty-third Street, in the island behind the Times Tower. He asked for a copy of the Scranton morning paper. The newsie ducked into his shack and came back with a folded copy of the Scranton Courier-Herald. He looked at the date. It was Saturday’s paper.

“This the latest?”

“What is it, Saturday? That’s the latest. No good?”

“I need today’s.”

The newsie said, “Can’t do it. The bigger cities, Chicago or Philly or Detroit, we get in the afternoon if it’s a morning paper or the next day if it’s a night paper. The towns, we rim about two days behind. You want Monday’s Courier-Herald, it would be Wednesday afternoon by the time I had it for you, maybe Thursday morning.”

“I need this morning’s paper. Even if it’s late.”

“You could use it Wednesday?”

“Yes,” he said. “And tomorrow’s, too.”

“Yeah. Say, we only get two or three. You want ’em, I could set ’em aside for you. If you’re sure you’ll be coming back. Any paper I’m stuck with, then I’m stuck with it. But if you want ’em, I could hold ’em for you.”

“How much are they?”

“Half a buck each.’

“If I give you a dollar now, will you be sure to have a copy of each for me?”

“You don’t have to pay me now.”

“I’d just as soon,” Dave said. He gave the man a dollar, then had to wait while the newsie scrawled out a receipt and made a note for himself on a scrap of paper.

Around the corner, he bought the New York afternoon papers at another newsstand. They didn’t have any of the morning papers left. But the news of Carroll’s murder wouldn’t have gotten to New York in time for the morning papers anyway. He took the papers to a cafeteria on Forty-second Street, bought a cup of coffee, and sat down at an empty table. He checked very carefully and found no mention of the shooting in any of the papers. He left them on his table and went out of the cafeteria.

Two doors down, he stopped at an outdoor phone booth and flipped through two telephone directories, the one for Manhattan and the one for Brooklyn. There were seven Lublins listed in Manhattan and nine in Brooklyn, plus “Lublin’s Flowers” and “Lublin and Devlin — Bakers.” The other local phone books were not there, just Manhattan and Brooklyn. He went to the Walgreen’s on the corner of Seventh Avenue and Forty-second, and the store had the books for the Bronx and Queens and Staten Island. There were fourteen Lublins listed in the Bronx, six in Queens, and none in Staten Island. The Walgreen’s did not have telephone books for northern New Jersey, Long Island, or Westchester County. And Lublin might live in one of those places. There was no guarantee that he lived in the city itself.

In the classified directory — a separate book in New York, not just a section of yellow pages at the back — he turned to “Contractors, General.” He looked first for “Lublin,” because he had grown used to looking for Lublins, but there were no contractors listed under that name. He tried looking for “Carroll, Joseph.” He found “Carroll, Jas” and “Carrel, J.” He waited until one of the phone booths was empty, and then he dropped a dime in the slot and dialed the number for Carroll, Jas in Queens. A man answered. Dave said, “Is Mr. Carroll there?”

“Speaking.”

He hung up quickly and tried another dime. He | called Carrel, J., also in Queens, and the line was busy. He hung up. There was a woman waiting to use the booth. He let her wait. He called again, and this time a girl answered.

“Mr. Carrel, please,” he said.

“Which Mr. Carrel?”

Which Mr. Carrel? He said, “I didn’t know there were more than one. Was more than one.”

“There are two Mr. Carrels,” the girl said. “Whom did you wish to speak to?”

“What are their names?”

“We have a Mr. Jacob Carrel and a Mr. Leonard Carrel. Lennie... Mr. Leonard Carrel, I mean, is the son. He’s not in, but Mr. Jacob Carrel—”

He hung up the phone. For the hell of it, he looked up “Joseph Carroll” in the Brooklyn book. There were listings for fourteen Joseph Carrolls in Brooklyn. He did not bother looking in the other books.

The only way was through Carroll, he thought. They had to learn who the man was. If they learned who Carroll was they could find the right Lublin, and once they got Lublin they could find the men he had hired to do the killing. It was impossible to find Carroll or Lublin or anyone else through the phone book. The city was too big. There were thirty-six Lublins listed in New York City and God knew how many more with no phones or unlisted numbers. And he had never heard the name Lublin before, even. A name he’d never heard, and there were too many of them in New York City for him to know where to begin.

She was waiting in the room at the Royalton. He told her where he had gone and what he had done. She didn’t say anything.

He said, “Right now there’s nothing to do but wait There should be a story in one of the morning papers, and then there should be a longer story in the Scranton papers when we get them. Maybe we should have stayed around the lodge for a day or two, maybe we would have found out something.”

“I couldn’t stay there.”

“No, neither could I.”

“We could go to Scranton, if you want. And save a day.”

He shook his head. “That’s going around Robin Hood’s barn. We wait. We’re here, and we’ll stay here. Once we find out who Carroll is, or was, then we can think of what to do.”

“You think he was a gangster?”

“Something like that.”

“I liked him,” she said.

Around six-thirty they went across the street and had dinner at a Chinese restaurant. The food was fair. They went back to the hotel and sat in the room but it was too small, they felt too confined. There was a television set in the room. She turned it on and started watching a panel show. He got up, went over to the set, and turned it off. “Come on,” he said. “Let’s get out of here, let’s go to a movie.”

“What’s playing?”

“What’s the difference?”

They went to the Criterion on Broadway and saw a sexy comedy with Dean Martin and Shirley MacLaine. He bought loge tickets and they shared cigarettes and watched the movie. They got there about ten minutes after the picture started, left about fifteen minutes before it ended. On the way back to the hotel they stopped at a newsstand, and he tried to buy the morning papers. The early edition of the Daily News was the only one available. He bought the News and they went back to their room.

He divided the paper in half and they went through it. There was nothing about the murder in either section. He picked up both halves and threw them out. She asked what time it was.

“Nine-thirty.”

“This takes forever,” she said. “Do you want to try getting the Times again?”

“Not yet.”

She got up and walked to the window, turned, walked to the bed, turned again and faced him. “I think I’m going crazy,” she said.

He got up, walked to her. She turned from him. She said, “Like a lion in a cage.”

“Easy, baby.”

“Let’s get drunk, Dave. Can we do that?”

Her face was calm, unreally so. Her hands, at her sides, were knotted into tight little fists with her long fingernails digging into her palms. She saw him looking at her fists, and she opened her hands. There were red marks on the palms of her hands — she had very nearly broken the skin.

He picked up the phone and got the bell captain. He ordered a bottle of V.O., ice, club soda, and two glasses. When the lad brought their order he met him at the door, took the tray from him, signed the tab, and gave the kid a dollar.

“My husband is a big tipper,” she said. “How much money do we have left?”

“A couple of hundred. Enough.”

He started making the drinks. She said, “How much is the hotel room?”

“I don’t know. Why?”

“We could go to a cheaper hotel. We’ll be here a while and we don’t want to run out of money.”

“They’ll take a check.”

“They will?”

“Any hotel will,” he said. “Any halfway decent hotel.”

She took her drink and held it awkwardly while he finished making one for himself. He raised his glass toward her and she lowered her eyes and drank part of her drink. When their glasses were empty he took them over to the dresser and added more whiskey and a little more soda.

“I’m going to get drunk tonight,” she said. “I’ve never been really stoned in front of you, have I?”

“The hell you haven’t.”

“I don’t mean parties. Everybody gets drunk at parties. I mean plain drinking where you’re just trying to get stoned, like now. We used to at college. My roommate and I, my junior year. My roommate was a girl from Virginia named Mary Beth George. You never met her.”

“No.”

“We would get stoned together and tell each other all our little problems. She used to cry when she got drunk. I didn’t. We swore that we would be each other’s maid of honor. Or matron, whoever got married first. I didn’t even invite her to the wedding. I never even thought to. Isn’t that terrible?”

“Is she married?”

“I think so.”

“Did she invite you to her wedding?”

“No. We lost track of each other. Isn’t that the worst thing you ever heard of? We drank vodka and water. Did you ever have that?”

“Yes.”

“It didn’t have any taste at all. It tasted like water with too much chlorine in it, the way it gets in the winter sometimes. You know how I mean, don’t you?”

“Yes.”

“With a little provocation I think I could maybe become an alcoholic. Will you make me another of these, please?”

He fixed her another drink. He made it strong, and he added a little of the V.O. to his own glass. She took several small quick sips from her drink.

She said, “I didn’t even know you then. Both in Binghamton and we never even met. We went to two different schools together. That’s a stupid line, isn’t it? There was a comedian who used to say that, but I can’t remember who. Can you?”

“No.”

“There are some other lines like that. Would you rather go to New York or by train?’ Silly. ‘Do you walk to school or take your lunch?’ I think that’s my favorite. I didn’t fall in love with you the first time I saw you. I didn’t even like you. What dreadful things I’m telling you! But when you asked me out I felt very excited. I didn’t know why. I thought here I don’t like him, but I’m excited he asked me out. I can’t stop talking. I’m just babbling like an idiot, I can’t stop talking.”

She drank almost all of her drink in one swallow and took a step toward him, just one step, and then stopped. There was a moment when he thought she was going to fall down and he started for her to catch her but she stayed on her feet. She had a worried look on her face.

She said, “I might be sick.”

“Don’t worry about it.”

“I want you to make love to me, you know that, don’t you? You know I want that, don’t you?”

He held her and her face was pressed against his chest. She put her hands on his upper arms and pushed him away a little and looked up into his eyes. Her own eyes were a deeper green than ever, the color of fine jade.

She said, “I want to but I can’t. I love you, I love you more than I ever did, but I just can’t do anything. Do you understand?”

“Yes. Don’t talk about it.”

“This afternoon I thought I would wait for you and when you came back I would get you to make love to me, and everything would be all right. You haven’t tried to make love to me. I think if you’d tried, before, I would have gone crazy. I don’t know. But I sat here in this room and I planned it out, all of it, and just what I would do and just how I would feel, and I was all alone in the room, and all of a sudden I started to shake. I couldn’t do it. Oh, I’m afraid.”

“Don’t be.”

“Will I be all right?”

“Yes.”

“How can you tell?”

“I know.”

“I think you’re right. I think everything’s just stopped, just shut up in a box, until we do what we have to do. Those men. I can shut my eyes and see their faces perfectly. If I knew how to draw I could draw them, every detail. I’ll be all right afterward, I think.”

A few minutes later she said, “This is some honeymoon, isn’t it? I’m sorry, darling.” Then he took her into the bathroom and held her while she threw up. She was very sick and he held her and told her it was all right, everything was all right. He helped her wash up and he undressed her and put her to bed. She did not cry at all through any of this. He put her to bed and covered her with the sheet and the blanket and she looked up at him and said that she loved him, and he kissed her. She was asleep almost at once.

He had one more drink, no soda and no ice. He capped the bottle and put it in the dresser with his shirts. In the morning, he thought, he would have to take a bundle to the laundry, the two shirts he had worn and a pair of slacks. And he would have to buy some things if he got the chance. He had packed mostly sportswear for the stay at the lodge and he would need dress shirts in New York.

The liquor helped him sleep. He woke up very suddenly and looked at his watch and it was seven o’clock, he had slept eight hours. He got dressed and went downstairs and outside. Jill was still sleeping. He bought the morning newspapers and went back to the room, and one of them had the story.

Chapter 5

Pennsylvania Shooting Victim Identified As Hicksville Builder

Scranton, Pa. — State police today identified the victim of a vicious gangland-style slaying as Joseph P. Corelli, a Long Island building contractor residing in Hicksville.

Corelli was shot to death late Sunday in an as yet unsolved attack outside his cabin at Pomquit Lodge on nearby Lake Wallenpaupack. “It has all the earmarks of a professional murder,” stated Sheriff Roy Fairland of Pomquit. “Corelli was shot five times in the head and two different guns were used.”

The dead man had resided at Pomquit Lodge for almost three months prior to the murder. He was registered at the Lodge as Joseph Carroll and carried false identification in that name. Proper identification of Corelli was facilitated through fingerprint records of the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

Corelli was arrested three times in the past five years, twice on charges of extortion and once for possession of betting slips. He was released each time without being brought to trial, according to New York Police Sgt. James Gregg. “He [Corelli] had definite underworld connections,” Sgt. Gregg asserted. “He had several criminal contacts that we know of, and it’s a good bet he was operating outside the law.”

Nassau County police officials denied knowledge of any recent criminal activity on Corelli’s part. “We were aware of his record and kept an eye on him,” one officer stated, “but if he was involved in anything shady, it was going on outside of our jurisdiction.”

Corelli, a bachelor, lived alone at 4113 Bayview Road in Hicksville and maintained an office in the Bascom Building, also in Hicksville. His sole survivor is a sister, Mrs. Raymond Romagno of Boston.

When he opened the door of the hotel room she sat up in the bed and blinked at him. Her face was pale and drawn. He asked her if she was all right.

“I’m a little rocky,” she said. “I drank too much, I got all sloppy. I’m sorry.”

“Forget it. It’s in the paper.”

“Carroll?”

“Corelli,” he said. He folded the paper open to the story and handed it to her. She couldn’t find it at first and he sat next to her and pointed it out to her. He watched her face while she worked her way through the article. Halfway through she motioned for a cigarette and he lit one for her. She coughed on it but went on reading to the end of the article. Then she set the paper on the bed beside her. She finished the cigarette and put it out in the ashtray on top of the bedside table. She started to say something, then realized for the first time that she didn’t have any clothes on. She looked at herself and jumped up and ran into the bathroom.

When she came out she looked reborn. Her face was fresh and clean, the pallor gone from it now. She had lipstick on. He smoked a cigarette while she put on a dress and shoes.

She said, “Corelli. I didn’t think he looked Italian.”

“He could have been almost anything, as far as I could tell. He didn’t look Irish, either.”

“Carroll isn’t always Irish.”

“I guess not.”

“There was a composer named Corelli. Before Bach, I think. We were right about almost everything, weren’t we? About who he was. He was in construction, but he was also a gangster.”

“In a small way.” He thought a minute. “There are some things that aren’t in that article.”

“You mean about us?”

“I mean about Carroll. Corelli. What rackets he was in, who his friends were. They talked a lot about his contacts but they didn’t say who they were. It might help to know.”

“How do we find out?”

“From the police,” he said.

‘You mean just ask them?”

“Not exactly,” he said.

They skipped breakfast. They left the hotel and found an empty phone booth in a drugstore on Sixth Avenue. He coached her on what to say and she practiced while he looked up the number of police headquarters in the Manhattan book. He wrote the number in his notebook and she said, “Let me try it now. How does this sound?”

He listened while she went through her speech. Then he said, “I think that’s right. It’s hard to tell without hearing it over the phone. Let’s give it a try.”

She went into the booth and closed the door. She dialed the number he had written down. A man answered in the middle of the first ring.

She said, “Sergeant James Gregg, please. Long distance calling.”

The man asked her who was calling. She said, “The Scranton Courier-Herald.”

The man told her to hang on, he’d see if he could find Gregg. There was a pause, and some voices in the distance, and a click and silence, another click and a youngish voice saying, “Gregg here.”

“Sergeant James Gregg?”

“Speaking.”

“Go ahead, please.” She opened the phone-booth door quickly, stepped outside and handed the receiver to Dave. He took it, ducked into the booth and pulled the door shut

He said, “Sergeant Gregg? This is Pete Miller at the Courier-Herald. We’re trying to work up a background story on the Corelli murder, and I’d like to ask you a couple of questions.”

“Again? I just talked to you people an hour ago.”

“I just came on,” he said quickly. “What we’re trying to do, Sergeant Gregg, what I’m trying to do, is to work up a human-interest piece on Corelli. Gangland killings, in this area, they’re exciting—”

“Exciting?”

“—and people are interested. Could you tell me a few things about Corelli?”

“Well, I’m pretty busy now.”

“It won’t take a minute, Sergeant. Now, first of all, I think you or somebody else mentioned that Corelli was connected with the underworld.”

“He had connections,” Gregg said guardedly.

“What sort of racket was he in?”

There was a short pause. Then, “What he was in was construction. We don’t know exactly what he did on the side, the illegal side. He knew a lot of gamblers, and his last arrest was here in Manhattan, he was picked up in a gambling raid. We didn’t have a case against him and we let him go.”

“I see.”

“His business was all out on Long Island. That’s out of our jurisdiction, and we didn’t nose around in that connection. We know he was in touch with some people here in the city, some racket people, but we don’t know what exactly he was doing. If he was working a racket in Long Island, well, that wasn’t our business.”

“Could you tell me some of his associates in New York?”

“Why?”

“It would give the story some color,” he said.

“The names wouldn’t mean anything to you,” Gregg said. “You’re out in Scranton and Corelli’s friends, the ones we know about, are just small-time gamblers. People like George White and Eddie Mizell, just people nobody ever heard of. No one important.”

“I see,” he said. “How about a man named Lublin?”

“Maurie Lublin? What about him?”

“Was he an associate of Corelli’s?”

“Where did you hear that?”

“The name came up, I don’t remember where. Was he?”

“I never heard about it. It might be. People like Corelli know a lot of people, it’s hard to say. Offhand I would say Maurie Lublin is too big to be interested in Corelli.”

“Do you know why Corelli was killed?”

“Well, it’s not our case. There’s nothing certain. Just rumors.”

“Rumors?”

“That’s right.”

It was like pulling teeth, he thought. He said, “What kind of rumors?”

“He was supposed to owe money.”

“To anyone in particular?”

“We don’t know, and I wouldn’t want to say anyway. Jesus, don’t you people ever get together on anything? I talked to one of your men and told him most of this just a little while ago. Can’t you get it from him?”

“Well, you probably talked to someone on straight news, Sergeant Gregg. I’m on features.”

“Oh.”

“I don’t want to keep you, I know you’re busy. Just one thing more. Will you be in charge of the investigation in New York?”

“Investigation?”

“Of the Corelli murder.”

“What investigation?” Gregg seemed almost irritated. “He was a man from Long Island who got himself killed out of state. We’re not doing anything about it. We’ll cooperate with Pennsylvania if they ask us to, but we’re not doing anything.”

“Will there be an investigation in Hicksville?”

“On the Island? What for? He got shot out of state, for God’s sake.”

He thought, Pennsylvania would shelve it because Corelli was from New York, and New York would forget about it because the murder happened in Pennsylvania. He said, “Thank you very much, Sergeant. You’ve been a big help, and I didn’t mean to take too much of your time.”

“It’s okay,” Gregg said. “We try to cooperate.”

He got out of the booth. She started to ask him a question, but he shook his head and began writing in the little notebook. He wrote: “Maurie Lublin.” Under that he wrote: “George White and Eddie Mizell.” On the next line he wrote: “Corelli owed money.” Then: “No Investigation.”

The drugstore was too crowded to talk in. He took her arm, put the notebook back in his breast pocket, and led her out of the store. There was a Cobb’s Corner across the street. They waited for the light to change, crossed Sixth Avenue and went into the restaurant. It was past nine already. Most of the breakfast crowd had gone to work and the place was near empty. They took a table for two in the rear and ordered orange juice and toast and coffee. He gave her the whole conversation by the time the waitress brought the food.

“You’d make a good reporter,” she said.

“And you’d make a good telephone operator. I kept waiting for him to catch on and start wondering who the hell I was and why I was bothering him, but he believed it all the way. We learned a lot.”

“Yes.”

“A hell of a lot. George White and Eddie Mizell — I don’t know what we can do with those names. But there is a Lublin. And he’s a crook, and he’s in New York somewhere. Maurie Lublin. Maurice, I guess that would be.”

“Or Morris.”

“One or the other. And everything still holds together the way we figured it. That Joe Corelli owed money, I mean. And that was why he was running.”

She nodded and sipped her coffee. He lit a cigarette and set it down in an oval glass ashtray.

“The big thing is that there’s no investigation. Not in New York and not in Hicksville. Isn’t that a hell of a name for a town?”

“Probably a description.”

“Probably. But the cops there won’t bother with the murder. They may close a file on Corelli but that’s all. That means we go out there.”

“To Hicksville?”

“That’s right.”

“Is that safe?”

“It’s safe. There won’t be any police there, not at his place and not at his office either. The New York police aren’t interested in Corelli any more. And Lublin’s men won’t be there, either.”

“How do you know?”

“They had about three months to search Corelli’s room and office. Maybe that was how they found out where he was, how they got the idea. That lodge was out of the way. They must have had some information or they never would have dug him up. They’ve probably sifted through his papers and everything else a dozen times already. Now he’s out of the way. They won’t be interested any more.”

She looked thoughtful. He said, “Maybe you should stay at the hotel, baby. I’ll run out there myself.”

“No.”

“It won’t take long. And—”

“No. Whither thou goest and all that. That’s not it. I was just wondering what we could find there. If they already searched—”

“They were looking for different things. They wanted, to find out where Corelli was hiding, and we want to find out why he was hiding, and from whom. It’s worth a try.”

“And I’m going with you, Dave.” He argued some more and got nowhere with it. He let it go. It seemed safe enough, and perhaps she’d be better off with him than alone with her thoughts at the hotel.

The doorman at the Royalton got the car for them. He told them how to find the Queens-Midtown tunnel and what to do when they were through it. The sky was clouded over and the air was thick with the promise of rain. They drove through the tunnel and cut east across Queens on an expressway. The road was confusing. They missed the turnoff for Hicksville, went five miles out of their way and cut back. At an Atlantic station they filled the gas tank and found out where Bayview Road was. They hit Bayview Road in the 2300 block and drove past numbered streets until they found the address listed in the newspaper story. Hicksville was monolithic, block after block of semidetached two-story brick houses with treeless front yards and a transient air, a general impression that all the inhabitants were merely living there until they could afford to move again, either further out on the Island or closer to the city.

Corelli’s building, 4113, was another faceless brick building jammed between 4111 and 4115. There were wash lines in the back. According to the mailboxes, someone named Haas lived upstairs and someone named Penner lived on the ground floor. Dave stepped back into the street to check the address, then dug the newspaper clipping from his wallet to make sure he had read it correctly the first time around: “Corelli, a bachelor, lived alone at 4113 Bayview Road in Hicksville...”

Jill told him to try the downstairs buzzer. “Probably the landlord,” she said. “They buy the house and live downstairs and rent out the upstairs. The income covers the mortgage payments.”

He rang the downstairs bell and waited. There were sounds inside the house but nothing happened. He rang again, and a muffled voice called, “All right, I’m coming, take it easy.”

He waited. The door opened inward and a woman peered suspiciously at him through the screen door. Her face said she thought he was a salesman and she wasn’t interested. Then she caught sight of Jill and decided that he wasn’t a salesman and her face softened slightly. She still wasn’t thrilled to see him, her face said, but at least he wasn’t selling anything, and that was a break.

He said, “Mrs. Penner?”

She nodded. He searched for the right phrasing, something that would fit whether or not she knew Corelli was dead. “My name is Peter Miller,” he said. “Does a Mr. Joseph Corelli live in the upstairs apartment?”

“Why?”

“Just business,” he said, smiling.

“He used to live here. I rented the place after he skipped on me. He lives here for three years, he pays his rent every time the first of the month, and then he skips. Just one day he’s gone.” She shook her head. “Just disappears. Didn’t take his things, that’s his furniture and he left it, everything. I figured he would be back. Leaving everything, you would think he’d be back, wouldn’t you?”

He nodded. She didn’t know Corelli was dead, he thought. Maybe that was good.

“But he never shows,” she said, shifting conveniently into present tense again. “He never shows, and I hold the place a month, waiting for him. That’s seventy dollars I’m out plus another week before I could rent it. I don’t rent to colored and it took a full week before they moved in, Mr. and Mrs. Haas. Eighty-five dollars he cost me, Corelli.”

“Do you have his things? His furniture and all?”

“I rented the place furnished,” Mrs. Penner said. She was defensive now. “Mrs. Haas, she didn’t have any furniture. They just got married. No kids, you know?” She shook her head again. “There’ll be kids, though. A young couple, they’ll have kids soon enough, you bet on it. One thing about Corelli, he was quiet up there. What about his things? He send you or something?”

Jill said, “Mrs. Penner, I’m Joe’s sister. Joe called me, he’s in Arizona and he had to leave New York in a hurry.”

“Cop trouble?”

“He didn’t say. Mrs. Penner—”

“There was cops came around right after he left. Showed me their badges and went pawing through everything.” She paused. “They don’t look like cops, not them. But they show me their badges and that’s enough. I don’t like to stick my nose in.”

Jill said, “Mrs. Penner, you know Joe was in business here. There was a lawsuit and he had to leave the state to stay out of trouble. It wasn’t police trouble.”

“So?”

“He called me yesterday,” she went on. “There were some things of his, some things he had to leave here, and he wanted me to get them for him.”

“Sure.”

“If I could just—”

The screen door stayed shut. “As soon as I get that eighty-five dollars,” she said. “That’s what he cost me, that eighty-five dollars. There was no lease so that’s all, just the eighty-five, but I want that before he gets his stuff.”

Jill didn’t say anything. Dave took out a cigarette and said, “You can hold the furniture for the time being, Mrs. Penner. In fact I think Joe would just as soon you kept the furniture, and then you can go on renting the flat furnished. It’s worth more than eighty-five dollars, but just to make things easier you could keep the furniture for the rent you missed out on.”

He could see her mind working, balancing the extra five or ten dollars a month against the eighty-five dollars Corelli had cost her. She looked as though she wanted a little more, so he said, “Unless you’d rather have the money. Then I could have a truck here later this afternoon to pick up the furniture.”

He could imagine her trying to explain that to the Haases. Quickly she said, “No, it’s fair enough. And easier all around, right?”

“That’s what I thought. Now if we could see Joe’s other stuff, his clothes and all. You kept everything, didn’t you?”

She had everything downstairs in large cardboard boxes. Suits, ties, slacks, underwear. Corelli had had an extensive wardrobe, sharp Broadway suits with Phil Kronfeld and Martin Janss labels in them. There was one boxful of papers. Dave took the carton and carried it out to the car. Jill waited in the car, and he went back to the house and told Mrs. Penner he would send somebody around for the rest of the stuff, the clothes and everything. “Today or tomorrow,” he said.

That was fine with her. He got into the car and drove off.