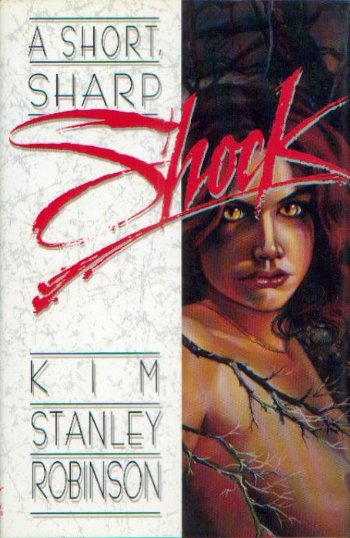

A Short, Sharp Shock

by Kim Stanley Robinson

1. The Night Beach

When he came to he was drowning. The water was black and he bobbed up in it swiftly, obscurely aware that it was dangerous to do so, but he was helpless to stop; he tumbled over and swam downward, arms loose and thrusting like tentacles, but it was useless. Air popped out of him in a stream of white bubbles that flattened and shimmied as they squashed upward, all clustered around bearing him to the surface. He glanced up, suddenly aware of the idea of surface; and there it was, an undulating sheet of obsidian silk on which chips of raw silver skittered wildly back and forth. A flock of startled birds turning all at once—no—it was, he thought as the world began to roar, the shattered image of a crescent moon. At the thought a whole cosmology bloomed in him—

And broke apart like the moon’s image, as he crashed up into the air and gasped. He flailed at the water whooping and kicking hard to stay afloat; he felt a wave lift him, and flopped around to face it. A cold smack in the face and he tumbled again, thrashed through a somersault and came up breathing, barking like a seal to suck in more air.

The next time under he rammed a sandbar and then he was rolling on a steep shorebreak, sluiced by sandy water and struck repeatedly by small silver fish. He crawled up through rushing foam, mouth full of salty grit, hands sinking wrist-deep in the wet sand. The little fish leaped in the phosphorescent foam, banged into his arms and legs. The beach was bouncing with silver fish, it was like an infestation of insects. On hands and knees he couldn’t avoid squashing some into the sand.

At the high-water mark he collapsed. He looked across a gleaming black strand, filigreed with sea foam receding on a wave. Coarse-grained sand sparked with reflected moonlight, and the fish arched to the shape of the crescent moon, which hung over the horizon at the end of a mirrorflake path of water. Such a dense, intricate, shifting texture of black and white—

A large wave caught him, rolled him back down among the suffocating fish. He clawed the sand without effect, then slammed into another body, warm and as naked as he was. The receding wave rushed down to the triple ripple of the low-water mark, leaving them behind: he and a woman, a woman with close-cropped hair. She appeared senseless and he tried to pull her up, but the next wave knocked them down and rolled them like driftwood. He untangled himself from her and got to his knees, took her arms and pulled her up the wet sand, shifting one knee at a time, the little silver fish bouncing all around them. When he had gotten her a few body lengths into dry sand he fell beside her. He couldn’t move.

From down the beach came shrill birdy cries. Children ran up to them shouting, buckets swinging at the ends of their arms like great deformed hands. When they ran on he could not move his head to track them. They returned to his field of vision, with taller people whose heads scraped the moon. The children dashed up and down the strand on the lace edge of the waves. They dumped full buckets of wriggling silver leaves in a pile beyond his head. Fire bloomed and driftwood was thrown on it, until transparent gold ribbons leaped up into the night.

Then another wave caught them and rolled them back down to the sea; the tide was rising and they would have perished, but the cords of a thrown net stopped them short, and they were hauled back and dumped closer to the fire, which hissed and sizzled. The children were laughing.

Later, fighting unconsciousness, he lifted the great stone at the end of his neck. The fire had died, the moon sat on the beach. He looked at the woman beside him. She lay on her stomach, one knee to the side. Dry sand stuck to her skin and the moonlight reflecting from her was gritty; it sparkled as she breathed. Powerful thighs met in a rounded muscly bottom, which curved the light into the dip of her lower back. Her upper back was broad, her spine in a deep trough of muscle, her shoulders rangy, her biceps thick. Short-cropped hair, dark under the moon’s glaze, curled tight to her head; and the profile glimpsed over one shoulder was straight-nosed and somehow classical: a swimmer, he thought as his head fell back, with the big chest and smooth hard muscling of a sponge diver, or a sea goddess, something from the myths of a world he couldn’t remember.

Then her arm shifted out, and her hand came to rest against his flank, and the feel of her coursed all through him: a short, sharp shock. He caught his breath and found he was sitting up facing her, her palm both cool and warm against his side. He watched her catch the moon on her skin and fling it away.

2. Sea Wrack

When he woke in the morning, the woman was gone. The sun burned just over the water. He lay on a crumbling sand cliff, the high mark of the previous tide’s assault on the beach. With his head resting on one ear, he saw a wet slick foam-flecked strand of silvery brown, and the sea; resting on the other, he saw a lumpy expanse of blond beach, dotted with driftwood. Behind the beach was a forest, which rose steeply to a very tall cliff of white stone; its top edge made a brilliant border with the deep blue sky above.

He lifted his head and noticed that the sand cliff under him was a tiny model of the granite cliff standing over the forest—a transient replica, already falling into the sea. But then again the immense rock cliff was also falling into the sea, the forest its beach, the beach its strand. It repeated the little sand cliff’s dissolution on a scale of time so much vaster that the idea of it made him dizzy. The tide ebbs and the stars die.

On the wet strand a troop of birds ran back and forth. They seemed a kind of sandpiper, except their feathers were a dark, metallic red. They stabbed away at dead grunion rolling in the wrack, and then dashed madly up the strand chased by waves, their stick legs pumping over blurred reflections of themselves. They made one of these frantic cavalry charges right under a thick white fishing line; surprised at the sight, he raised himself up on his elbows and looked behind him.

A surf fisher sat on a big driftwood log. In fact there were several of them, scattered down the beach at more or less regular intervals. The one closest to him was all in brown, an old brown woman in a baggy coat and floppy hat, who waved briefly at him and did not stir from her log.

He stood and walked to her. Beside her a bucket stood on the sand, filled with the little silver fish from the previous night. She gestured at the bucket, offering him some of the fish, and he saw that her hand was a thick mass of shiny dark brown, her fingers long tubes of lighter hollow brown, with bulbs at their ends. Like tubes of seaweed. And her coat was a brown frond of kelp, and her face a wrinkled brown bulb, popped by the slit of her mouth; and her eyes were polyps, smooth and wet.

An animated bundle of seaweed. He knew this was wrong, but there she sat, and the sun was bright and it was hard to think. Many things inside his head had broken or gone away. He felt no particular emotion. He sat on the sand beside her fishing pole, trying to think. There was a thick tendril that fell from her lower back to her driftwood log, attaching her to it.

He found he was puzzled. “Were you here last night?” he croaked.

The old woman cackled. “A wild one. The stars fell and the fish tried to become birds again. Spring.” She had a wet hissing voice, a strange accent. But it was his language, or a language he knew. He couldn’t decide if he knew any others or not.

She gestured again at her bucket, repeating her offer. Noticing suddenly the pangs of his hunger, he took a few grunion from the bucket and swallowed them.

When he had finished he said, “Where is the woman who washed up with me?”

She jerked a thumb at the forest behind them. “Sold to the spine kings.”

“Sold?”

“They took her, but they gave us some hooks.”

He looked up at the stone cliff above the trees, and she nodded.

“Up there, yes. But they’ll take her on to Kataptron Cove.”

“Why not me?”

“They didn’t want you.”

A child ran down the beach toward them, stepping on the edge of the sand cliff and collapsing it with her passage. She too wore a baggy frond coat and a floppy hat. He noticed that each of the seated surf fishers had a child running about in its area. Buckets sat on the sand like discarded party hats. For a long time he sat and watched the child approach. It was hard to think. The sunlight hurt his eyes.

“Who am I?” he said.

“You can’t expect me to tell you that,” the fisherwoman said.

“No.” He shook his head. “But I… I don’t know who I am.”

“We say, The fish knows it’s a fish when we yank it into the air.”

He got to his feet, laughed oddly, waited for the blood to return to his head. “Perhaps I’m a fish, then. But… I don’t know what’s happened to me. I don’t know what happened.”

“Whatever happened, you’re here.” She shrugged and began to reel in her line. “It’s now that matters, we say.”

He considered it.

“Which way is the cove you mentioned?” he said at last.

She pointed down the beach, away from the sun. “But the beach ends, and the cliff falls straight into the sea. It’s best to climb it here.”

He looked at the cliff. It would be a hard climb. He took a few more grunion from the bucket. Fellow fish, dead of self-discovery. The seaweed woman grubbed in a dark mass of stuff in the lee of her log, then offered him a skirt of woven seaweed. He tied it around his waist, thanked her and took off across the beach.

“You’d better hurry,” she called after him. “Kataptron Cove is a long way west, and the spine kings are fast.”

3. The Spine

The forest was thick and damp, with leaves scattered at every level, from the rotting logs embedded in the carpet of ferns to the sunbroken ceiling of leaves overhead. Streams gurgled down the slope, but apparently it had not rained for some time, as smaller creekbeds held only trickles; one served him as a pebble-bottomed trail, broken by networks of exposed roots. In the cool gloom he hiked uphill, moving from glade to glade as if from one green room to the next, each sculpted according to a different theory of space and color. Leaves everywhere gave proof of his eye’s infinite depth of field, and all was still except for the water falling to the sea—and an occasional flash in his peripheral vision, birds, perhaps, which he could never quite see.

The forest ended at the bottom of the cliff, which rose overhead like the side of an enormous continent. Boulders taller than the trees were scattered about at the foot of the cliff. Ferns and mosses covered the tumble of rotten granite between boulders. The cliff itself was riven by deep gullies, which were almost as steep as the buttresses separating them. He clambered between boulders looking for a likely way up, in a constant fine mist: far above waterfalls had broken apart, and to the left against the white rock was a broad faint rainbow.

Just as he was concluding that he would have to scramble up one of the gullies he came on a trail going up the side of one, beginning abruptly in the ferny talus. The trail was wide enough for two people to walk side by side, and had been hacked out of the granite side wall of the gully, where it switchbacked frequently. When the side wall became completely vertical, the trail wound out over the buttress to the left and zigzagged up that steep finger of stone, in stubborn defiance of the breathtaking exposure. It was impossible to imagine how the trail had been built, and it was also true that a break any where in the supporting walls would have cut the trail as neatly as miles of empty air; but there were no breaks, and the weedless gravel and polished bedrock he walked over indicated frequent use. He climbed as if on a staircase in a dream, endlessly ascending in hairpin turns, until the forest and beach below became no more than green and blond stripes running as far as he could see in both directions, between the sun-beaten blue of the ocean and the sunbeaten white of the granite.

Then the cliff laid back, and the trail led straight ahead on an incline that got less and less steep, until he saw ahead a skyline of shattered granite, running right to left as far as he could see. The rock stood stark against the sky. He hurried forward and suddenly he was on the crest of a ridge extending to his left and right, and before him he saw ocean again—ocean far below, spread out in front of him exactly as it was behind. Surprised, he walked automatically to a point where he could see all the way down: a steep cliff, a strip of forest, a strip of sand, the white-on-blue tapestry of breaking waves, the intense cobalt of the sea. He stepped back and staggered a little, trying to look in every direction at once.

He was standing on the crest of a tall peninsula, which snaked through an empty ocean for as far as he could see. It was a narrow ridge of white granite, running roughly east to west, bisecting the blue plate of the sea and twice marring the circular line of the horizon. The ridge rose to peaks again and again, higher perhaps in the talcum of afternoon light to the west; it also undulated back and forth, big S shapes making a frozen sine wave. The horizon was an enormous distance away, so far away that it seemed wrong to him, as wrong as the seaweed woman. In fact the whole prospect was fantastically strange; but there he stood, feeling the wind rake hard over the lichen-stained ridge, watching it shove at low shrubs and tufts of sedge.

It occurred to him that the peninsula extended all the way around the world. A big ocean world, and this lofty ring of rock its only land: he was sure of it. It was as if it were something he remembered.

4. Beauty Is the Promise of Happiness

And the only happiness is action. So he roused himself and headed west, thinking that a bend in the peninsula out that way might hide Kataptron Cove. The sun fell just to the right of the rock, slowing as it fell, flattening as if reluctant to touch the horizon, breaking into bands of glowing orange light that stretched until they were sucked down by the sea. The twilight was long, a mauve and purple half day, and he hiked rapidly over the crest’s shattered granite, which was studded with crystals of translucent quartz. As he walked over the rough edges of stones, feeling liberty in the twisting ligaments of his ankles, he kept an eye out for some sort of shelter for the night. The trail he had followed onto the spine had disappeared, no doubt because the crest itself served as a broad high trail; but at one point a deep transverse cleft had been filled at a single spot by boulders, confirming his notion that the trail still ran, and would reappear when needed.

So he was not surprised when he came upon a low circular stone hut, next to a small pool of water. In this area stone broke away from the bedrock in irregular plates, and a great number of these had been gathered and stacked in rings that grew successively smaller as they got higher off the ground, until a final large capstone topped things off. The stones had been sized and placed so precisely that it would have been difficult to get more than a fingernail between any two of them. A short chimney made of smaller stones protruded from one side of the roof.

Opening a wooden door in the wall opposite the chimney, he entered and found a wooden shelf circling the interior of the wall. Next to the fireplace was a stack of kindling and logs; other than that the hut was empty. He was without the means to start a fire, and it was fairly warm in any case, so he went back outside and drank from the pool, then sat against the west wall to eat the last of the fisherwoman’s grunion, in the final hour of twilight. As the light leaked out of the sky it turned a deep rich blue, dark but not quite black: and across this strangely palpable firmament the stars popped into existence, thousands upon thousands of them, from bright disks that might have been nearby planets to dots so faint that he could only see them by looking slightly to the side. Eventually the sky was packed with stars, so densely that they defined perfectly the dome of sky; and frightened him. “Where I come from there are not so many stars,” he said shakily to the hut, and then felt acutely his solitude, and the emptinesses inside his mind, the black membranes he could not penetrate. He retreated into the hut. After a long time lying on the hard wooden shelf, he fell asleep.

Sometime before dawn he was awakened by a crowd of folk banging in the doorway. They held him down and searched under his skirt. They had broad hard hands. Cloaks made of small leaves sewn together clicked in the dark, and it smelled like oranges.

“Are you the spine kings?” he asked, drunk with sleep.

They laughed, an airy sound. One said, “If we were you’d be strangled with your own guts by now.”

“Or tossed down the cliff.”

The first voice said, “Or both. The spine kings’ hello.”

They all had lumps on their left shoulders, irregular dark masses that looked like shrubs. They took him out of the hut, and under the sea-colored sky he saw that the lumps were in fact shrubs—miniature fruit trees, it appeared, growing out of their left shoulders. The fruits were fragrant and still reminded him of oranges, although the smell had been altered by the salt tang, made more bitter. Round fruit, in any case, of a washed-out color that in better light might have been pale green.

The members of this group arranged themselves in a circle facing inward, took off their leaf cloaks and sat down. He sat in the circle between two of them, glancing at the shoulder tree to his right. It definitely grew directly out of the creature’s skin—the gnarled little roots dove into the flesh just as a wart would, leaving an overgrown fissure between bark and skin.

With a jerk he looked away. It was almost dawn, and the treefolk began singing a low monophonic chant, in a language he didn’t recognize. The sky brightened to its day blue, slightly thickened by the sun’s absence, and the wind suddenly picked up, as if a door had banged open somewhere—a cool fresh breeze, peeling over the spine in the same moment that the sun pricked the distant gray line of the horizon, a green point stretching to a line of hot yellow and then a band of white fire, throwing the sea’s surface into shadow and revealing a scree of low diaphanous cloud. Before the sun had detached itself from the sea each member of the circle had plucked a fruit from the shoulder of the person on their right, and when the sun was clear and the horizon sinking rapidly away from it, they ate. Their bites caused a faint crystalline ringing, and the odor of bitter oranges was strong. He felt his stomach muscles contract, and saliva ran down his throat. The celebrant nearest the sun glanced at him and said, “Treeless here will be hungry.”

He almost nodded, but held himself still.

“What’s your name?” the celebrant asked. He had been the first speaker in the hut.

“I don’t know.”

“No?” The creature considered it. “Treeless will be good enough, then. In our naming language, that is Thel.”

In his mind he called himself Thel. But his real name… Black space, behind his nose, in the sky under his skull.… “It will do here,” he said, and waved a hand. “It is accurate enough.”

The man laughed. “So it is. I am Julo.” He looked across the circle. “Garth, come here.”

A young man stood. He had been sitting opposite Julo, facing out from the circle, and now Thel noticed his tree grew from the right shoulder rather than the left.

“This is Garth, which means Rightbush. Garth, give Thel here an apple.” Garth hesitated, and Julo strode across the circle of watchers and cuffed him on the arm. “Do it!”

Garth approached Thel and stood before him, looked down. Thel said to him, “Which should I choose?”

With a grateful glance up the youth indicated the largest fruit, on a lower branch. Thel took the round green sphere in his fingers and pulled sharply, noting Garth’s involuntary wince. Then he sniffed the stem, and bit through the skin. The bitter taste of orange, he sat in a small dark room, watching the wick of a lamp lit by a match held in long fingers, the flame turned up and burning poorly, in a library with bookcases for walls and a huge old leather globe in one corner.… He shook his head, back on the windy dawn spine, Julo’s laughter in his ear, behind that a crystalline ringing. A bird hovered in the updraft, a windhover searching the lee cliff for prey. “Thank you,” Thel said to Garth.

The treefolk gathered around him, touched his bare shoulders, asked him questions. He had nothing but questions in reply. Who were the spine kings? he asked, and their faces darkened. “Why do you ask?” Julo said. “Why don’t you know?”

Thel explained. “The fisherfolk pulled me from the sea. Before that—I don’t know. I can’t…” He shook-his head. “They pulled out a woman with me, a swimmer, and sold her to the spine kings.” He gestured helplessly, the thought of her painful. Already the memory of her was fading, he knew. But that touch in the moonlight—“I want to find her.”

“They have some of our people as well,” Julo said. “We’re going after them.” He reached into his bag and threw Thel a leaf cloak and a pair of leather moccasins with thick soles. “You can come along. They’re at Kataptron Cove, for the sacrifices.”

The boy’s fruit was suddenly heavy on his stomach, and he shuddered as if every cell in him had tasted something bitter.

5. The Snake and the Tree

The treefolk hiked long and hard, following a line on the broad crest that minimized the ups and downs, nearly running along a rock road that Thel judged to be some three thousand feet above the sea. After a few days, the south side of the sinuous peninsula became a fairly gentle slope, cut by ravines and covered with tall redwood trees; in places on this side the beach was a wide expanse, dotted with ponds and green with rippling dune grass. The north side, on the other hand, remained a nearly vertical cliff, falling directly into waves, which slapped against the rock unbroken and sent bowed counterwaves back out to the north, stippling the blue surface of the water with intersecting arcs.

Once their ridge road narrowed, and big blocky towers of pink granite stood in their way. The trail reappeared then, on the sunny southern slope, and they followed it along a contoured traverse below the boulders, passing small pools that looked hacked into the rock. Half a day of this and they had passed the sharp peaks and were back on the ridge, looking ahead down its back as it snaked through the blue ocean. “How long is this peninsula?” Thel asked, but they only stared at him.

Every morning at sunrise Julo ordered young Garth to provide a shoulder apple for Thel’s consumption, and in the absence of any other food Thel accepted it and ate hungrily. He saw no more hallucinations, but each time experienced a sudden flush of pinkness in his vision, and felt the bitter tang of the taste to his bones. His right shoulder began to ache as he lay down to sleep. He ignored it and hiked on. He noticed that on cloudy days his companions hiked more slowly, and that when they stopped by pools to rest on those days, they took off their boots and stuck their feet between cracks in the rock, looking weary and relaxed.

Some days later the peninsula took a broad curve to the north, and for the first time the sun set on the south side of it. They stopped at a hut set on a particularly high knob on the ridge, and Thel looked around at the peninsula, splitting the ocean all the way to the distant horizon. It was a big world, no doubt of it; and the days and nights were much longer than what he had been used to, he was sure. He grew tired at midday, and often woke for a time in the middle of the long nights. “It doesn’t make sense,” he said to Garth, waving, perplexed at the mountainous mound zigzagging across the sea. “There isn’t any geological process that could create a feature like this.”

This was said almost in jest, given the other more important mysteries of his existence. But Garth stared at him, eyes feverish. He was lying exhausted, his feet deep in a crack; seeing this in the evenings Thel always resolved not to eat, and every morning he awoke too ravenous to refuse. Now, as if to pay Garth back with conversation, he added, “Land floats like wood, thick cakes of it drifting on slow currents of melted rock below, and a peninsula like this, as tall as this… I suppose it could be a mid-oceanic ridge, but in that case it would be volcanic, and this is all granite. I don’t understand.”

Garth said, “It’s here, so it must be possible.”

Thel laughed. “The basis of your world’s philosophy. You didn’t tell me you were a philosopher.”

Garth smiled bitterly, “Live like me and you too will become one. Maybe it’s happening already, eh? Maybe before you swam ashore you didn’t concern yourself with questions like that.”

“No,” Thel said, considering it. “I was always curious. I think.” And to Garth’s laugh: “So it feels, you see. Perhaps not everything is gone.” It seemed possible that the questions came from the shattered side of his mind, from some past self he couldn’t recall but which shaped his thinking anyway. “Perhaps I studied rock.”

At sunset the wind tended to die, just as the sunrise quickened it; now it slackened. Perhaps I have died like the wind, he thought; perhaps the only thing that survives after death are the questions, or the habit of questioning.

The two of them watched the sun sink, just to the left of the bump of the spine on the horizon. “It’s as if it’s a river in reverse,” Thel said. “If a deep river ran across a desert land, and then you reversed the landscape, water and earth, you would get something that looked like this.”

“The earth river,” Garth said. “The priests of the bird-folk call it that.”

“Are there any tributaries? Any lakes-turned-into-islands?”

“I’ve never seen any.”

The air darkened and the salt air grew chill. Garth was breathing deeply, about to fall asleep, when he said in a voice not his, a voice pleasant but at the same time chilling: “Through mirrors we see things right way round at last.”

In the days that followed, this image of a landscape in reverse haunted Thel, though in the end it explained nothing. The stony spine continued to split the water, and it got taller, the south side becoming as steep as the north again. In places they walked on a strip of level granite no wider than a person, and on each side the cliffs plunged some five thousand feet into white foam tapestries that shifted back and forth over deep water, as if something below the blue were lightly breathing: it disturbed one’s balance to look down at it, and though the strip was wide enough to walk on comfortably, the sheer airiness of it gave Thel vertigo. Garth walked over it with a pinched expression, and Julo laughed at him, cuffed him hard so that he had to go to his knees to avoid falling over the side; then Julo forced him to walk backwards, which served the others as amusement.

Eventually the north side grew less steep, laying out until the peninsula was wider than ever. In this section a hot white cliff faced south, a cool forested slope faced north. On the north slope were scattered stands of enormous evergreens, the tallest trees three or four hundred feet high. One of these giants stood on a ledge just below the crest, and had grown up above the ridge, where the winds had flattened it so that its branches grew horizontally in all directions, some laying over the ridge, others fanning out into the air over the beach and the sea far below.

The treefolk greeted this flat-topped giant as an ancestor, and clambered out over the horizontal branches to the tree’s mighty trunk, over it, and out the other side. They ended up on three or four lightning-blasted gnarly branches, ten feet wide and so solid that jumping up and down would not move them, though the whole tree swayed gently in a fitful west wind. Big shallow circular depressions had been cut into the tops of these branches, and the exposed wood had been polished till it gleamed.

They spent the night in these open-roofed rooms, under the star-flooded sky. By starlight Thel looked at the wood by his head and saw the grain of centuries of growth exposed. The peninsula had been here for thousands of years, millions of years—both the plant life and the erosion of the granite showed that. But how had it begun? “When you talk among yourselves about the spine,” he said to the treefolk, “do you ever talk about where it came from? Do you have a story that explains it?”

Julo was looking down into the grain of the floor beneath him, still and rapt as if he had not heard Thel; but after a while he said, in a low voice, “We tell a story about it. Traveling in silent majesty along their ordered ways, the gods tree and snake were lovers in the time without time. But they fell into time, and snake saw a vision of a lover as mobile as he, and he chased round the sky until he saw the vision was his own tail. He bit the tail in anger and began to bleed, and his blood flowed out into a single great drop, bound by the circle his long body made. He died of the loss, and tree climbed on his back and drove her roots deep into his body, trying to feed his blood into him, trying to bring him back to life, and all her acorns dropped and grew to join in the attempt. And here we are, accidents of her effort, trying to help her as we can, and some day the snake will live again, and we will all sail off among the stars, traveling in silent majesty.”

“Ah,” Thel said. And then: “I see.”

But he didn’t see, and he arranged himself for sleep and looked up into the thickets of stars, disappointed. Garth lay next to him, and much later, when the others were asleep, he whispered to him, “You don’t know where you came from. You have no idea how you came here or what you are. Worry about that, and when you know those things, then worry about the great spine.”

6. Kataptron Cove

The next dawn it was bitterly cold out on the swaying branches, and they sat back against the curved wall of the biggest room shivering as Julo watched the sky to determine the exact moment of sunrise, hidden behind the ridge. When he turned to pluck the fruit from the man next to him he took three, and the others did the same. Thel restricted himself to his usual one of Garth’s, and asked him why the others had eaten more.

“We’ll reach Kataptron Cove this evening.”

And so they did. It was on the south side, in an arc the peninsula made. Here the granite side of the peninsula was marred by the shattered walls of a small crater—a horseshoe ring of jagged black rock, extending into the sea and broken open to it as its outermost point, so that the inside of the crater was a small lagoon. Clearly it was an old volcanic vent, and as it was the first sign of vulcanism that Thel had seen, he approached it with interest.

But he was soon distracted by the grim faces of the treefolk, who marched around him as if going into battle. Foreboding charged the air, and the treefolk abandoned the trail that descended the southern slope in a long traverse to the crater bay, and struggled through dense woods above the trail.

They descended into thick salt air rilled with the sound of waves, gliding from tree to tree like spirits, moving very slowly onto the high crumbly rim of the crater, overlooking the inner lagoon. The curving inner wall of the crater was a reddish cliff, overgrown with green. Where the crater met the spine a stream fell down the inner wall and across the sand into the lagoon; on the banks of the stream there was a permanent camp, built in a grove of trees that had been cleared of undergrowth. In the shadows of these trees people moved, and smoke spiraled up through the sunbeams lancing among the branches.

In the depths of the grove there was a hubbub, and a crowd emerged onto the open beach, a gang wearing leather skirts and belted short swords, and tight golden helmets. They chivvied along a short row of prisoners, naked and in chains, and Thel heard Garth whimper softly. He looked around and saw that the treefolk had their eyes fixed on the beach in horror and unwilling fascination. “What is it?” he said.

Garth pointed at where the grove met the beach. Two tall tree trunks standing beside each other had been stripped bare; behind the trunks stood a platform about half their height. “It’s the flex X,” Garth whispered, and would not elaborate. He sat with his back to the scene, head in hands.

Thel and the rest of the treefolk watched as a prisoner was hauled up the steps of the platform. Two crews on the ground set about winding ropes tied to the top of each tree trunk, until the trunks were crossing each other at about the level of the platform. Intuitively Thel understood the function of the large bowed X the trees made, and his stomach contracted to a hard knot of tension and vicarious terror; still he watched as the first prisoner was tied to the two trees, and the thick ropes holding the trees in position were knocked off notched stumps, and the two tall trunks returned to an upright position, with a stately swaying motion that had not the slightest hitch in it when the prisoner was ripped apart. Blood fountained from the head and the body, now separated. Thel saw that the beach around the two trees was littered with lumps here and there, all a dark brown, now splattered with red: the wreckage of lives.

At that distance people were the size of dolls, and they heard nothing of them over the sounds of waves. The executioners tied each prisoner to the two trees in a different manner, so that the second came apart at the limbs, and the third in the middle, leaving a long loop of intestine hanging between the two poles.

Thel found he was sitting. His skin was covered with a sour sweat. He felt cold. He moved in front of Garth, took his face in his hands. “The spine kings?”

Garth nodded miserably.

“Who are they?”

No response. Feeling the futility of the question, Thel stood and went to Mo, who laughed maliciously as he saw Thel’s face.

“What will you do?” Thel asked.

“Go have a look. They’ll be drinking tonight, they’ll all get drunk and there’ll be little watch kept. They fear no one in any case. We can be quiet, and some of us will go have a look for our kind. If we can find them, we can see what kind of lock they’re under. It may be possible to slip them out on a night like this. We’re lucky to have seen that,” he said, ironic to the point of snarling. “We know they’ll be off guard.”

Thel nodded, impressed despite himself by Julo’s courage. “I want to come with you,” he said. “I can look for the swimmer.”

“She’ll be under stronger guard,” Julo warned him. “But you’re welcome to try. It’s why you’re here, right?”

7. Two Xs

So in the long indigo twilight they made their way around the rim of the crater bay like ghosts, stepping so silently that the loudest sound coming from them was their heartbeats, locking at the backs of their open mouths. Shadows with heartbeats, as silent as the fear of death, slipping from trunk to trunk and searching the forest ahead with the acute gaze of hunted beasts… the spine king sentinels carried crossbows, Julo had said. They descended the crater wall well away from the village, and then worked their way back to it through a thin forest of pines, stepping across a carpet of brown needles.

Ahead came the sound of voices, and the beach stream. The leaves of the treefolk’s shoulder bushes rustled when they moved too quickly. It was getting dark, the color draining out of everything except the pinpricks of fire dancing in the black needles ahead.

Drumming began, parodying their heavy heartbeats. They hugged the crater wall, circled to the edge of a firelit clearing. In the clearing were huts, cages, and platforms, all made of straight branches with the bark still on them. Some of the cages held huddled figures.

Thel froze. Reflection of torchlight from a pair of eyes, the shaggy head of a wild beast captured and caged, brilliant whites defiant and exhausted: it was her. Thel stared and stared at the black lump of the body, heavy in the dark, clothed only in dirt—the tangled hair backlit by fire-eyes reflecting torchlight. He had no idea why he was so certain. But he knew it was the swimmer.

The treefolk were clustered around him. When guards with torches arrived in the clearing, the prisoners sat up, and around him Thel heard a faint rustling of leaves. He peered more closely and saw that the cage beside the swimmer’s held seated figures, slumped over. One of them begged for water and the guards approached. In the sharply flickering torchlight Thel could see slack faces, eyes shut against the light, odd hunched shoulders—ah. Trunks, stalks, stumps: their shoulder bushes had been chopped off. One of the captured treefolk, lying flat on the ground, was hauled up; he still had his little tree, its fruit gone, its leaves drooping. “The fire’s low,” one guard said drunkenly, and drew his short broadsword and hacked away. It took several blows, thunk, thunk, the victim weeping, his companions listless, looking away, the other guards holding the victim upright and steady and finally bending the trunk of the miniature tree until it broke with a dull crack. The victim flopped to the ground and the guards left the cage and tossed the little tree onto the embers of a big fire: it flared up white and burned well for several minutes, as if the wood were resinous.

Thel’s companions had watched this scene without moving; only the rustle of leaves betrayed their distress. The guards left and they slipped back into the black forest, and Thel followed them. When they showed no signs of stopping he crashed forward recklessly, and pulled at Julo’s arm; when Julo shrugged him offand continued on, Thel reached out and grabbed the trunk of Julo’s shoulder tree and yanked him around, and then had to defend himself immediately from a vicious rain of blows, which stopped only when “the other treefolk threw themselves between the two, protesting in anxious mutters, whispering, “Shh, shh, shhh.”

“What are you doing?” Thel cried softly.

“Leaving,” Julo said between his teeth.

“Aren’t you going to free them?”

“They’re dead.” Julo turned away, clearly too disgusted and furious to discuss it further. With a fierce chopping gesture he led the others away.

“What about the swimmer?”

They didn’t stop. Suddenly the black forest seemed filled with distant voices, with drunken bodies crashing into underbrush, with yellow winking torches bouncing through the trees. Thel backed into a tree, leaned against the shaggy bark. He took deep deliberate breaths. The cage had, been made of lashed branches, but out in the center of the clearing like that…

“I’ll help you,” Garth said out of the darkness, giving Thel a start. “It’s me, Garth.”

They held each other’s forearms in the dark. “You’ll lose the others if you stay,” Thel said.

“I know,” Garth said, voice low and bitter. “You’ve seen how he treats me. I want to be free of them all, forever. I’ll make my own life from now on.”

“That’s not an easy thing,” Thel said.

Without replying Garth turned back the way they had come, and they crept back to the clearing. Once there they lay behind a fallen log and looked into the firelit cages. Garth’s fellow folk sat there listlessly. “Their trees won’t grow back?”

“Would your arm?”

“And so they’ll die?”

“Yes.”

Garth slipped away, and after a time Thel saw an orange light like a sort of firefly bobbing through the trees: Garth, holding a branch tipped by a glowing ember. Thel joined him, and they crept to the back of the treefolk’s cage, and Garth held the tip of the branch to the lashings at the bottom of one pole. As they blew on the coal the treefolk inside watched, without a sound or any sign of interest. Garth begged those inside to emerge, and got no reply.

Thel stared at the orange ember which brightened as they blew on it, embarrassed for Garth, and worried about what he could do alone. When the cage lashing caught fire with a miniature explosion of white flame, Garth looked at his comrades through the smoke and said fiercely, “You know what the spine kings have done to you! You know what they’ll do to you next! Come out and exact some revenge, meet your end like trees should. While you do we can rescue a friend who yet lives, and you’ll either make a quick end to it, or escape to be free on the great spine when your time comes.” He jerked hard on the pole and it came loose. “Come on, get out there among them and remember the part of you they threw on their fires.”

One of them started forward and crawled under the lifted pole, and the rest looked at each other, at the raw stumps protruding from their shoulders; they too slipped from the cage. In a moment they had all disappeared into the dark.

“It would be better if we had something else for the other cage,” Garth said to Thel. “The ember is dying.”

“There are a lot more in the fire.”

“My kin’s lives.”

“They can free these others.”

Garth nodded. “We burn hot. But one of those swords they carry would be helpful.” And he disappeared again.

Thel waited, as near the swimmer’s cage as he could get without emerging into the light. From the hut beside the bonfire and the central cage came the sounds of laughter, then those of an argument turning ugly. Around him in the forest were odd noises, sudden silences, and he imagined the treeless treefolk wandering murderously in the dark, jumping drunken guards as they stumbled off to piss in the trees, bludgeoning them and then stealing their swords to slip between the ribs of others. The spine kings feared no one and now they would pay, ambushed in their own village in the midst of their death bacchanal. Sick with images of brutal murder, keyed to the highest pitch of tension, Thel leaped to his feet involuntarily as a crash and cries came from the direction of the beach, and the guards in the clearing’s hut rushed out and down a path. “The platform!” someone was shouting in the distance as Thel ran to the bonfire and snatched up a brand. Sparks streamed in a wide arc from the burning end as he ran to the cage and crushed the burning end of the branch against the lashings at the bottom of a pole. This cage was better constructed and it was going to take longer. A twig cracked behind him and the swimmer croaked a warning; he swung the brand around and caught an onrushing guard in the face. The guard’s raised broadsword flew into the cage, cutting one prisoner who cried out; the guard himself couldn’t do more than grunt, as Thel beat him furiously across the neck and head. When Thel turned back to the cage the prisoners had cut the lashing with the sword and were squeezing out of the cage and cursing one another under their breath. Thel took the swimmer woman by the arm and pulled her out; she was thicker than the others and barely fit through the gap. She appeared dazed, but when Thel held her face in his hands and caught her eye, she recognized him. Garth had reappeared, and Thel was about to lead the swimmer out of the clearing when one of the other prisoners said urgently, “Wonderful saviours, thank you eternally, please, follow me, I know where the trailhead is that leads up to the spine!” So they followed him, but it seemed to Thel he went straight for the center of the camp.

Shrieks cut the night and torches had been tossed high into the trees, some of which had caught fire and become great torches themselves, so that there was far too much light for their purpose. “Wait one moment please,” the prisoner who claimed to know the way said, and he ran into the largest house in the camp.

Apparently some of the treefolk amputees had found the flex X and set it alight. The crater wall enclosing the lagoon appeared out of the darkness, faintly illuminated by the burning village. Sparks wafted among the stars, it seemed the cosmos was winking out fire by fire. The prisoner ran out of the house carrying a sack. “Follow me now,” he cried jubilantly, “and run for your lives!”

They ran after him. Thel took the swimmer by the arm, determined not to lose her in the mayhem. But now the prisoner was true to his word, and he led them through firebroken shadows to a wide cobbled trail, ignoring the shouts and cries around them. The trail ran up to the crater’s rim and then along it, to the point where the crater wall diverged from the great slope of the spine ridge. The trail began to switchback up the slope. Looking across an arc of the lagoon they saw the village dotted with burning trees and smaller patches of fire, the flex X burning high on a beach glossy as a seal’s back, and there were two images of everything: one burning whitely over the beach, another, inverted, burning a clear yellow in the calm black water of the bay.

8. The Mirror

Afraid of the spine kings’ pursuit, they ran the trail west for many days, scarcely pausing to loot caches located by the prisoner who led them. The caches contained clothing and shoes, and also buried jugs of dried meat and fruit, lumps so hard and dry they couldn’t tell what anything was until chewing it; good food, but because there were seven of them they were still hungry. “We’ll come to my village soon,” the prisoner said one evening after doling out a meager dinner, and outfitting Thel and the swimmer in pants and tunics, and boots that were a lucky fit. The prisoner’s name was Tinou, and he had a wonderful big smile; he seemed astonished and delighted to have escaped the spine kings, and often he thanked Thel and Garth for their rescue. “When we get there we’ll eat like the lords of the ocean deep.”

The sun had set an hour before, and a line of clouds over the western horizon was the pink of azaleas, set in a sky the color of lapis. The seven sat around a small fire:

Thel, the swimmer, Garth, Tinou, and three women.

These women all had faces cast in the same mold, and a strange mold it was; where their right eye should have been the skin bulged out into another, smaller face, lively and animated, with features that did not look like the larger one around it—except for the fact that its own little right eye was again replaced by a face, a very little face—which had an even tinier face where its right eye should have been, and so on and so on, down in a short curve to the limit of visibility, and no doubt beyond.

This oddity made the three women’s faces impressive and even frightening, and because the three full-sized faces seldom spoke, Thel always felt that when talking to them he was really conversing with one of the smaller faces—perhaps the very smallest, beyond the limit of visibility—which might reply in a tiny high squeak at any time.

But now the three women stood before Tinou, and one said, “We want to know what you took from Kataptron Cove.”

“I took this bag,” Tinou said, “and it’s mine.”

“It is all of ours,” the middle woman said, her voice heavy and slow. Her companions moved to Tinou’s sides. “Show us what it is.”

In the dusk it was hard to tell if expressions or firelight were flickering across Tinou’s long and mobile face. Thel and the swimmer leaned forward together to see better this small confrontation, and Tinou flashed them his friendly smile. “I suppose there is justice in that,” he said, and picked up his shoulder bag. Untying the drawstring he said, “Here,” and slipped something out of the bag, a small shiny plate of some sort.

“Gold,” the middle faceworoan said. Tinou nodded. “Yes, in a manner of speaking. But it is more than that, in fact. It is a mirror, see?” He held it up—a round smooth mirror with no rim, the glass of it golden rather than silver. Held up against the dark eastern sky it gleamed like a lamp, revealing a rich blue line in a field of pink.

“It is no ordinary mirror,” Tinou said. “My people will reward us generously when we arrive with it, I assure you.”

He put it back in the bag, and for a moment it seemed to Thel he was stuffing light into the bag as well, until with a hard jerk he closed the drawstring. Wind riffled over them, below lay the calm surface of the sea, and in the east the moon rose, its blasted face round and brilliant; looking from it to the quick yellow banners of their fire, Thel suddenly felt he walked in a world of riches. Night beach and big-handed children, running the mirrorflake road on the sea.…

The next dawn they were off again. At first Thel had been shy of the swimmer, even a bit frightened of her; she couldn’t know how important her image had been to him before the rescue, and he didn’t know what to say to her. But now he walked behind her or beside her, depending on the width of the trail, and as they walked he asked her questions. Who was she? What did she remember from before the night they had washed onto the beach? What had gotten them to that point under the water? What was her name?

She only shook he head. She remembered the night on the beach; beyond that she was unable to say. She concentrated her gaze on her long feet, which seemed to have trouble negotiating the rock, and she rarely looked at him. He didn’t mind. It was a comfort to be walking with her and to know that someone shared the mystery of his arrival on the peninsula. She was a fellow exile, moving like a dancer caught in heavier gravity than she was used to, and it was a pleasure just to watch her as the sun roasted her brown hair white at the tips, and burned her pale skin red-brown. Often Aspects of her reminded Thel of that first night: the set of her rangy shoulders, the profile of her long nose. With speech or without, she reassured him.

And Garth—Garth too was an exile, a new one, and he hiked with them but in himself, skittish, distracted, sad. Thel hiked with him as well, and told him more stories of the rock under their feet, and Garth nodded to show he was listening; but he wasn’t entirely there. The leaves on his little tree drooped, as if they needed watering.

So they moved westward, and the peninsula got steep and narrow again, the granite as hard as iron and a gray near black, flecked with rose quartz nodules. The drop-offs on both sides became so extreme that they could see nothing but a short curved slope of rock, and then ocean, a few thousand feet below. Tinou told them that here the walls of the sea cliffs were concave, so that they walked on a tube of rock that rested on a thin vertical sheet of stone, layered like an onion. “Exfoliating granite,” Thel said. Tinou nodded, interested, and went on to say that in places the two cliffsides had fallen away to nothing, so that they were walking on arches over open holes, called the Serpent’s Gates. “If you were on the tide trail, you could climb up into them and sit under a giant rainbow of stone, the wind howling through the hole.”

Instead they tramped a trail set right down the edge of a fishback ridge. In places the trail had been hacked waist-deep into the dense dark rock, to give some protection, from falls. Every day Tinou said they were getting close to his village, and to support the claim (for somehow his cheerful assurances made Thel doubt him), the trail changed under their feet, shifting imperceptibly from barely touched broken rock to a loose riprap, and then to cobblestones set in rings of concentric overlapping arcs, and finally, early one morning shortly after they started. off, to a smoothly laid mosaic, made of small polished segments of the rose quartz. Longer swirls of dark hornblende were set into this pink road, forming letters in a cursive alphabet, and Tinou sang out the words they spelled in a jubilant tenor, the “Song of Mystic Arrival in Oia” as he explained, fluid syllables like the sound of a beach stream’s highest gurgling. At one point for their benefit he sang in the language they all shared:

We walk the edge of pain and death

And carve in waves our only hearth

And nothing ever brings us home.

But something makes us want to climb:

The sight of water cut like stone

A village hanging in the sky.

A village hanging in the sky

And nothing ever brings us home

But something makes us, climb.

And climb they did, all that long day, until they came over a rise in the ridge, and there facing the southern sea, tucked in a steep scoop in the top of the cliff, was a cluster of whitewashed blocky buildings, lined in tight rows so that the narrow lanes were protected from the wind. Terrace after terrace cut the in-curved slope, until it reached an escarpment hanging over the sea; from there a white staircase zigzagged down a gully to a tiny harbor below, three white buildings and a dock, gleaming like a pendant hanging from Oia.

9. The Sorcerers of Oia

A crowd greeted them as they entered the village, men and women convening almost as though by coincidence, as though if Tinou and his retinue had not appeared they would have gathered anyway; but when they saw Tinou they smiled, for the most part, and congratulated him on his return. “Not many escape the spine kings,” one woman said, and laughing the others crushed in on them to touch Tinou and his companions, while Tinou sang the trail’s mosaic song, ending with an exuberant leap in the air.

“I thought I would never return here again,” he cried, “and I never would have if not for Thel here, who slipped into the spine kings’ village the night we were to be torn apart on the crossing trees. He set us free, he saved our lives!” Jubilantly he embraced Thel, then added, “He made it possible for all of us to return to Oia—” and he took the mirror out of his shoulder bag.

Silence fell, and the crowd seemed both to step back and to press in at once. Thel thought he could hear the sound of the sea, murmuring far below. A woman dressed in a saffron dress said, “Well, Tinou, your return was one thing, but this—”

General laughter, and then they were being led into the narrow streets of the village. These either contoured across town, making simple arcs, or ascended it in steep marble staircases, each step bowed in the middle from centuries of wear. Every lane and alley was lined by blocky whitewashed buildings, often painted with the graceful cursive lettering. By the time they came to a tiny plaza on the far side of the village, the sun was low on the horizon; it broke under clouds and suddenly every west wall was as gold as Tinou’s mirror, and many of the west-facing windows were blinding white.

Restaurants ringed the plaza, each sporting a cluster of outdoor tables, and as dusk seeped into things lanterns were hung in small gnarled trees or put on windowsills, and the people ate and drank long into the night. Thel and the swimmer and the three facewomen ate voraciously, and became drunk on the fiery spirits poured for them, and the villagers danced, their long pantaloons and dresses swirling like the colors in a kaleidoscope, yards of cloth spinning under strong wiry naked torsos, both men and women dancing like gods, so that the watchers were shocked when a bottle shattered and the color of blood spurted into their field of vision, off to the side; a fight, quickly broken up, overridden by the gaiety of the sorcerers of Oia. The mirror was back.

In the days that followed, the celebration continued. Eventually it became clear that this was the permanent state of things in Oia, that this was the way the sorcerers lived. They poured seawater into stone vats, and later drew their spirits from taps at the vats’ bottoms. Sea lions brought them their daily fish in exchange for drinks of this liquor; the creatures swam right up to the dock at the cliff bottom, barking hoarsely as they deposited long three-eyed fish on the dock. Later the sorcerers turned some of the fish meat into tough dark red steak, which tasted nothing like the flaking fish. Their gardens and goats were tended by their children—and in short, they lived lives of leisure, playing complex games, undergoing abstruse studies, and performing rituals and ceremonies. Tinou took his fellow travelers with him wherever he went, and introduced them as his saviours, and they were feted to exhaustion.

One day to escape it Thel and the swimmer walked down the staircase trail that switchbacked precipitously to the sea. On the way they passed grown-over foundations, and roofless walls rilled with weeds: vestiges of earlier Oias, shaken by earthquakes into the sea. On the dock below some of the sorcerers stood talking to the sea lions, taking their bloody catch and pouring tankards of the liquor down their throats. Even their vilest imprecations couldn’t keep a flock of gulls away, and the gulls wheeled overhead crying madly until the barking sea lions breached far into the air, thick sleek sluglike bodies twisting adroitly as they snagged birds and crushed them in their small powerful mouths. Eventually the gulls departed and the lions swam off, a wrack of feathered corpses left on the groundswell. After they were gone, Thel and the swimmer shed their garments and dove in. Underwater Thel became instantly afraid, but the sight of the swimmer stroking downward was somehow familiar, and strangely reassuring. He stayed under for as long as hecould hold his breath, and then joined her in bodysurfing the groundswells that rose up to strike the cliffs. As the two rode the waves they remained completely inside the water, surfing as the sea lions did, and they were drawn swiftly forward in the wave until they ducked down and out to avoid crashing into the cliff or the dock. During these rides, slung through the water by two curves of space-time rushing across each other, Thel would look over at the swimmer’s long naked body and feel his own flowing in the water, until it was hard to hold his breath, not because he was winded but because he needed to shout for joy.

When they pulled themselves back onto the worn stones of the dock, Tinou was there, except now he was a woman, laughing in a contralto at their expressions as she stripped and dove in; her face was clearly Tinou’s, unmistakable despite the fact that it was slimmer, more feminine—yet clearly not a sister or twin, no, nothing but Tinou himself, shape-changed into a svelte female form. Thel and the swimmer looked at each other, baffled by this transformation; and halfway through the long climb up the stairs Tinou caught up with them, a man again, coquettishly embracing first the swimmer and then Thel (slim wet arms quick around his shoulders), and then laughing uproariously at their expressions.

That sunset he led them and the facewomen down into the ruins of the previous village. Here broken buildings had dropped their barrel roofs onto their floors, and worn splintered sticks of old furniture still stuck out between the bowed bricks. Other sorcerers set lanterns in a circle around what appeared to be an abandoned plaza, smaller even than the one above, and in the long lavender dusk more of the sorcerers gathered, somber for once and drinking hard. In the sky above a windhover caught the last rays of the sun, a white kestrel turned pink by the sunset, fluttering its wings in the rapid complex pattern that allows it to stay fixed in the air. Tinou took the stolen mirror from his bag and set it on a short wooden stand, on the eastern edge of the circle the sorcerers made. Against the starry east it was a circle of pure pink sheen. When Tinou sat down the circle of seated sorcerers was complete, and they began to sing, their faces upturned to the windhover riding the last rays of the sun. The light leaked out of the sky and the wind riffled the enormous space of dusk and the sea, and Thel, surprising himself, feeling the old compulsion, said “As you can change your shape, and bend the world to serve you, perhaps you can tell me how this world came to be the way it is.”

They all stared at him. “We have only a story,” Tinou said finally in a kind tone, “just like anyone else.”

Another voice took over, that of an old woman; but it was impossible to pick out the speaker from the circle of faces. “The universe burst from a bubble the size of an eye, some fifteen billion years ago, and it has been flying apart ever since. It will achieve its maximum reach outward in our lifetimes, and fall back into that eye of density which is God’s eye, and then all will begin again, just as it was the time before, and the time before that, eternally. So that every breath that you take has occurred in just that way an infinity of times, and all of us are but statues in time to the eye of God.”

“As for this world,” said the voice of an old man, a cold, hard voice, “this road of mountain across an empty sea, an equatorial peninsula circumnavigating the great globe: it came about like this:

“Gods fly through space in bubbles of glass, and their powers exceed ours as ours exceed those of the stones we stand on, who know only to endure. And once long ago gods voyaged through this forgotten bay of the night sea, and to pass the time they argued a point of philosophy.” And here the speaker’s voice grew harsh, the edge of every word sharper, until they were as edged as the taste of Garth’s shoulder fruit, sending the same kind of bitter shock through Thel. “They argued aesthetics, the most metaphysical of philosophical problems. One of them said that beauty was a quality of the universe independent of any other, that it was inlaid in the fabric of being like gravity, in a pattern that no one could pull out. Another disagreed: beauty is the ache of mortality, this god said, an attribute of consciousness, and nothing is beautiful except perceived through the love of lost time, so that wherever there is beauty, love was there also, and first.”

Here another voice spoke, on the breaking edge of bitterness. “And so they agreed to put it to a test, and being gods and therefore just like us, less ignorant but no less cruel, they decided to transform and populate one of the planets they sailed by, sinking all its land but this spine under an endless sea, and then making what remained as beautiful as they could imagine; but leeching every living thing of love, to see if the beauty would yet remain. And here we are.”

Silence. For a moment Thel felt he was falling. A tray was passed around, and Thel did as the rest and took from it a thin white wafer, feeling a powerful compulsion. He ate it and his skin tingled as if crystallizing. Looking up he thought he could still see the kestrel hovering overhead, a black star among the sparkling white ones. The mirror’s surface was a dark lustrous violet now, nothing like the western sky which had grown as dark as the east; as his gaze began to fall into the drop of rich glossy color there was a disturbance across the circle, and one of the sorcerer children burst among them.

“The spine kings,” she gasped, “at the Thera Gate.”

All the sorcerers rose to their feet. “So,” Tinou said, “we must hurry a little.” Quickly several of them seized Thel by the arms and legs; when he struggled he might as well have been thrashing on an iron rack. His skin was shattering. The swimmer and the three facewomen were being held back. Thel was lifted up, carried to the mirror.

Tinou appeared beside him, touched his temple. His smile was solicitous. “My thanks for the rescue,” he said jovially, then in more formal tones: “Through mirrors we see things right way round at last.”

They shoved his left foot into the surface, which was as smooth as a glass of water full over the rim, completely violet and completely gold at one and the same time; and the foot went in to the ankle. Now he had a left foot made of fire, it seemed, and he twisted in the implacable grip, cried out. Tinou nodded sympathetically, cocked his head. “It’s pain most proves we live. Nothing serves better to focus our attention on our bodies and the flesh metronomes ticking inside them, timing the bombs that will go off some day and end the universe. Remember!”

He stepped forward and leaned over Thel’s face, looked at him curiously. “There are so many kinds of pain, really.” They shoved his leg in to the hip. “Is it pulsing, throbbing, shooting, lancing, cutting, stabbing, scalding? Is it pressing, gnawing, cramping, wrenching, burning, searing, ripping? Is it smarting, stinging, pricking, pounding, itching, freezing, drilling? Is it superficial or profound? Can you think of anything else? Can you tell me what eight times six equals? Can you take a full breath and hold it?”

And with each question Thel was thrust further in. A brief flare of genitals, the sickening twist of the gut, all his skin an organ of pain, every atom of him spinning in vain efforts to fly off—and Tinou, smiling, leaning over his face and questioning still, each word slower, louder, more drawn out: “’Is it dull, sore, taut, tender? Is it rasping, splitting, exhausting, sickening? Is it suffocating, frightful, punishing? Vicious, wretched? Blinding? Horrible? Killing? Excruciating? Unbearable?”

Then they got his face to the glossy surface, and the reflected visage within was that of a complete stranger, puffy and thick necked, eyes bulging out—I have never looked like that, Thel tried to say, certain he was dying. Compared to this the flex X would have been bliss, he thought, and with one last glimpse of Tinou’s laughing face he was through the glass and gone.

10. Through the Mirror

Blue stars ahead, red behind. Flare of an oil lamp in the library. We know more than our senses ever tell us, but how? How? Old brown globe, bookcases, beyond it a glassine sphere, the image of a wall. Milky black of the galactic core, tumbling down, down, down, down. Emergency landing. Emergence. The sensuous rise to consciousness.

Splayed on riprap, the taste of ocean wrack in his throat. Once with his parents he tripped and smashed his nose, vivid image of sunny pain and a chocolate ice cream,down by the canals filled with trash, a glassy sheen like the taste of blood suffusing every sundrenched manifestation of the world. Filled with sudden grief at the lost past, Thel sat up shakily and wiped his nose, spat red. Bloody spit on uneven paving stones, crowded with dead weeds. The whole village of Oia was in ruins, the walls just a block or two high. Dark wind was keening through him and the weeds rustled, it had been centuries and clearly he would never see the swimmer on the night beach again, it was past and irrecoverable. All his past was gone for good even if he could remember it; given the sense of loss for what little he could remember, it was perhaps for the best that so much was forgotten. But he knew he had had a life, childhood, adolescence, he felt its intensity and knew it would never return no matter what he did, even if he remembered every instant of it perfectly, as he felt he did, all of it right there behind some impermeable membrane in his mind, pressing against his thoughts until the ache of it filled everything.

And yet really it didn’t matter if he remembered or not. Live a life and seize it to you with an infant’s fierce clench of the fist, it still would slip away as lovely as the mountain sky at dusk and never come back again: not the moment in the dim library, the noon by the poolside, that moonlit beach and the warm sandy touch, none of it, none of it, none of it. How he loved his past in that moment, how he wanted it back! Eternal recurrence, as the sorcerers had said; ah, it would almost be worth it to be a clockwork mechanism, a bronze creature of destiny, if you could then have it over and over and over. As long as it felt new at every recurrence, who cared? He was a creature of destiny in any case, impelled by forces utterly beyond his control. To move his forefinger left rather than right was an enormous exertion against fate, anything more was too much to ask, it would be only water splashing uphill for a moment; he would bend to the curve of space-time at last, which leads to the sea in the end. Fate is the path of least action. And if you never know it is all recurrence then it only means you feel the loss, over and over and over. But he had loved his life, he knew he had, the bad and the good and he wanted to keep it forever, all of it, to observe it from some eternal beach and perhaps step back into it, a moment here, a moment there, looking out a bay window at streetlight, bare branch, falling snow, listening to a snatch of piano by the coals of a fire, those moments of being when all the past seemed in him and alive, suffusing the moment and the only moment with a feeling—with every feeling, all at once.

Wind soughed in the weeds. Inside him the flesh metronome went tick, tick. Life slipped away hadon by hadon, limning every joy with a rime of grief; and he walked backward into the future, waving and crying put “Goodbye! Good-bye! Good-bye!”

It was dark. There were only pinprick stars, a dozen at most though the sky was black as an eye’s pupil. Shivering with fear, he stood and staggered up one of the marble staircases, now littered with blocks of stone which glowed whitely underfoot, apparently from some internal luminance, so faint it was at the edge of the visible. He was seeing the skeleton of the world.

On the spine the view of both seas was disorienting, literally in that he became aware that the sun would dawn in the west, and that he would have to trek east to new ground to escape the spine kings. Still it was reassuring to see both the oceans, to straddle the high edge of the peninsula, riding the back of the present as it snaked through past and future. He stood there for a minute, savoring the view and the bitter bite of the wind.

Looking back down at the dark luminous ruins of Oia, he saw a figure moving up terrace after terrace, flitting between walls and seeming at times to jump from place to place instantaneously. The figure looked up, and its eyes gleamed like two stars in its dark face. Thel shivered and waited, knowing the figure was coming to join him; and so it did, taking much of the night though it moved rapidly.

Finally it approached him: a man, though it was a man so slight and fluid in his movement that he seemed androgynous, or feminine. His skin was blacker than the sky, so that his smile and the whites of his eyes seemed disembodied above clothing that glowed like the stones of Oia, outlining his slim form. “The spine kings are upon us,” he said in a bright, friendly voice. “Sidestepping them only works for so long. If you want to escape you’ll have to move fast. I can show you the way.”

“Lead on,” Thel said. He knew he could trust this figure, at the same time that another part of his mind was aware that it was a manifestation of Tinou. The intonation of the voice was the same, but it didn’t matter. This one could be trusted. “What is your name?” Thel asked, to be sure.

“I am Naousa,” the figure said, and reached forward in a confidential way to touch Thel lightly on the upper arm, a touch suasive and erotic. “This way.”

He led Thel to a steep drop-off in the ridge, unlike anything Thel had seen before. Here the spine of the peninsula planed down and away in a smooth flat incline, as if an enormous blade had shaved offthe mountain range, cutting at a hard angle down toward the beaches. Cliffs on the sides to north and south remained, while the cut itself descended at nearly a forty-five-degree angle. The exposed stone of the cut was as smooth as glass, and a black that somehow indicated it would be dark gray in daylight. Descending this slippery slope would be extremely difficult on foot, but Naousa reached deep into a cleft in the granite and pulled out two lightweight bobsleds, both a whitish color. The sleds’ bottoms were smoother than the glassy rock slope, and had no runners or steering mechanism. “You lean in the direction you want to go,” Naousa said. “The drop isn’t entirely level left to right, so you have to steer a little to keep from going over the cliffs. Just follow me, and look out for bumps.” And before Thel could nod he had jumped on his bobsled and was off.

Thel threw his sled down and sat on it, and quickly was sliding down the slope. Naousa was an obvious dot below, cutting big slalom curves down an invisible course. The cut slope was only a couple hundred feet wide, though it broadened as they dropped lower. Bumps and curves invisible to the eye threw Thel left and right as he picked up speed, accelerating at what seemed an accelerating rate; he realized the only hope for survival was to follow Naousa’s every move, even if it meant going as fast as Naousa and staying right on his tail. Naousa was flying down the slope, carving wide curves and crying out for joy—Thel could hear the shouts wafting back at him as another impossible turn by Naousa skirted the cliffs. It was thrilling to watch and Thel shouted himself, leaning hard left or right to follow Naousa’s bold track, and despite the fact that it was like bobsledding on an open ice slope with cliffs on both sides, Thel began to enjoy himself—to enjoy the contemplation of Naousa’s expertise, and his own reproduction of it, and the sheer noise of the sleds and the wind smashing his face and the tears streaming back over his ears and off the cliff edges into space, falling down like dewdrop stars into the original salt.

It was a long ride but did not take much time. At the bottom they sledded out onto the grass of a meadow and tumbled head over heels. Naousa picked up the sleds and tucked them behind a round boulder perched on the ridge.

Down here the peninsula was different in character: the stone old and weathered and graying, the spine only fifty to a hundred feet above the noisy sea, and the beaches to both sides wide, with sand white as could be, even in the starless night. “The south side is the easiest walking,” Naousa said, and headed down to the north side.

Thel shouted thanks, and dropped to the south side, and walked west toward the sunrise. The sun would be up soon, the sky to the west was blueing. The white sand underfoot was tightly packed; scuffing it made a squeaking sound, squick, squick, and the scuffed sand sprayed ahead of Thel’s feet in brief blazes of phosphorus. The dunes behind the tidal stretch were neatly scalloped and covered with dense short grass all blown flat, pointing west to the dawn. The dome of the sky was higher down here and fuzzier, the blues of dawn glowing pastels. Then as he walked stars began popping into sight overhead and he stepped knee-deep into the beach, as if the sand were gel; he was sinking in it, the sky was the pink of cherry blossoms and he was in sand to his cheekbones, drowning in it.

11. Inside the Wave

The sun was hot on his cheek. There was too much light. He rolled on sand, shaded his eyes with a hand and cracked a lid: his brain pulsed painfully and the eyelash-blurred gold-on-white pattern meant nothing to him, then coalesced with a jolt that jerked his body up. The swimmer lay on the wide morning beach. Beyond her lay Garth and the three facewomen, leaves in their hair and long scratches on their arms and legs. Then he saw the shape of the mirror, in a bag tucked under the swimmer’s outstretched arm. He was sitting and he almost rolled to her side, every muscle creaking as if carved of wood. He shook her arm, afraid to touch the bag holding the mirror.

She woke, and he asked her what had happened. She stared at him.

“I don’t remember,” he explained. “I mean, Tinou and the others pushed me through that,” pointing at the mirror bag.

“After that…”

She spoke slowly. “The spine kings attacked and everything caught fire. The sorcerers left you on the plaza, and the mirror as well. We picked you up and carried you away, and took the mirror too. Then you woke and told us to follow you, and we did. We climbed out on the cliff face beside Oia to escape the sorcerers and the spine kings, and the next night we climbed to the spine and started west. You talked most of the time but we couldn’t see who you talked to. Garth carried the mirror. The spine dropped into a forest and you ran all the way, and we chased you. Then it seemed you were never going to see us, and so Garth said we should push you back through the mirror. We did that and you fell through, unconscious—”

“You could just push me through?”

“No, it wouldn’t work at first, it was hard as glass when I tried it, but Garth said it had to be at sunset, on the spine, with a kessel hawk hunting in the western sky. We waited three days until we saw one, and then it worked. But after we got you through you were asleep again. So we waited and then we fell asleep too. I’m hungry.”

The others were stirring at the sound of their voices. They woke and the beach air was filled with the chatter of voices over the hiss of broken waves. As they shared their stories they walked to the sea without volition, drawn by their hunger. The peninsula had changed to something like what Thel had traversed in his time beyond the mirror: a low forested mound snaking through the sea, sandy moon bays alternating with chalky headlands. They walked to the next bay, which faced north. Here the beach was a steep pebbly shingle that roared and grumbled at every wave’s swift attack and retreat, and among the millions of shifting oval pebbles, which when wet looked like semiprecious stones, they found crabs, beach eels, scraps of seaweed that the facewomen declared edible, and one surprised-looking fish, tossed up by a wave and snatched by Garth. As they made their catch they wandered west, marking the sine curve of the hours with their passage until the sun was low. Knobs of old worn sandstone stood here and there like vertebrae out of the scrubby forest, and they climbed to one of these bony boulder knots collecting dead wood as they went, and in the sunset made a fire using Garth’s firestone and knocker. Every scrap of the sea’s provender tasted better than the last, the least scrap finer than a master chef’s creation. Clouds came in from the south as if a roll of carpet had been kicked over them, and the sinking sun tinted the frilly undersurface a delicate yellow. Their fire blazed through the long dusk, and in the wind the whitecaps tossed, so that it felt like they were on the deck of a ship.

Each day they foraged west, and spent the night on knolls. “We’ll reach your folk soon?” Thel asked the facewomen.

“No. Many days. But when we do, you can continue on your way speeded by our horses.”