The battle lines have been drawn. The people of Russalka turn upon one another in a ruthless and unwavering civil war even while their world sickens and the deep black ocean is stained red with their blood. As the young civilisation weakens, its vitality fuelling the opposing militaries at the cost of all else, the war drums beat louder and louder.

Katya Kuriakova knows it cannot last. Both sides are exhausted – it can only be a matter of days or weeks before they finally call a truce and negotiate. But the days and weeks pass, the death toll mounts, and still the enemy will not talk.

Then a figure from the tainted past returns to make her an offer she cannot lightly refuse – a plan to stop the war. But to do it she will have to turn her back on everything she has believed in, everything she has ever fought for, to make sacrifices greater even than laying down her own life. To save Russalka, she must become its greatest enemy.

Jonathan L. Howard

KATYA’S WAR

Dedicated to my fellow Strange Chemists, for their support, kindnesses, and general esprit de corps.

CHAPTER ONE

Lukyan

The piece of paper looked cheap and disposable and in no way commensurate with the hard work and trouble it was intended to reward.

Katya Kuriakova held up the paper between her index and middle finger and said, “What the hell is this?”

The Federal officer was too busy writing on his pad for several seconds before he could be bothered to answer her. “It’s your payment, captain.” He glanced up and deigned to look her in the face. “It’s a standard Federal compensation form, properly authorised. Payment in full for services rendered.”

Even a few years before, the officer might have found it strange to be calling a girl of sixteen “captain,” but that was what she was and protocol on such matters was inflexible. That her boat was some battered little utility bug was irrelevant. She stood there in a set of dark red overalls that bore her name and a “Master & Commander” stripe over the left breast pocket, her short blonde hair tousled unattractively by the same lack of sleep that was doubtless responsible for the dark rings under her eyes, glaring at him with aggressive disbelief, and holding up the Federal scrip as if it were a declaration of war or, at least, a grave personal insult.

Still, conceded the officer inwardly, she had a nice nose.

“A scrip? A scrip? Two days navigating the Vexations, dodging Yagizban patrols the whole way, pushing test depth for twelve hours at a stretch, and have you any idea what the sanitary arrangements on a minisub are like?”

The officer sighed. “Three things, captain. First, the scrip’s as good as money. Second…” he had to raise his voice slightly to override Katya’s furious denial that scrips were damn well nowhere near as good as money, “…I have no leeway on the matter. My orders are to pay captains with compensation forms. I have no money to give you even if my orders permitted it. And third, there is a war on.” He hefted his pad under his arm as if it were some marker of rank and walked further down the docking corridor towards another weary-looking captain and probably an identical argument.

Katya watched him go with the muted anger of somebody who knows from bitter experience that you can’t fight the system, especially when the system is running in a crisis and has its heels dug in against anything less important than its own survival.

There is a war on.

A single humourless laugh escaped her. Yes, officer, she thought, there is a war on. I helped start it.

She was glad she had kept that to herself; it really wouldn’t have helped matters.

She walked back to the minisub pens, to where her boat sat snugly held in its stall, aft door secure against the stable’s open access hatch. Sergei was just finishing draining the cess tank and looking as happy about it as could be expected. His mood was not improved when he saw the scrip in Katya’s hand.

“God’s teeth!” he muttered with the easy blasphemy of a born atheist. He picked up the toilet paper refill from the deck and held it out to her. “You might as well stick that thing in here. At least we’ll have a use for it then.”

Katya ignored the proffered box and stepped through the hatch, neatly avoiding catching her foot on the cess drainage tube. Four months previously she had not been so agile and the result had been impressively unpleasant. It was the sort of lesson that only needed learning once.

She sank into the fore starboard passenger’s seat and opened the locker beneath it. Inside was a waterproof documents box — “Guaranteed to resist pressures to five hundred metres!” according to the vendor — which she pulled out and unlocked with a four digit key. Inside, amongst all the other hardcopy documentation a properly registered submarine was supposed to carry and keep maintained, was a plastic folder labelled Magic Money Markers! Collect the set and see the wizerd! Labelled by Sergei, obviously. Certainly from its tone but not least because he had misspelled “wizard.” Within it was a wad of Federal Maritime Authority compensation forms, generically identical to the one that she now added to it. She quickly counted them, summing their worth as she went.

“Fancy going to Atlantis?” she called back to Sergei.

Sergei was just finishing with the cess tank. “Why is it not OK to vent the tank to the sea when it’s full, but it’s fine to vent it for cleaning after it’s been drained?” he asked and, like many of his questions, it was rhetorical. “I mean, like a bit of shit is going to break the ecosystem.” He locked down the tank’s hatch and cycled water through it from outside the hull. “Fish like shit, anyway. It’s got nutrients.”

“And deep thoughts like that are why you must never be put into any position of authority, Sergei. Now, pay attention. This is your captain speaking.” She waited until he had deactivated the cess tank’s cleaning procedure, replaced the deck plate over it, and then slowly swung his hand to his brow to make his usual lackadaisical and mocking salute to her. She took no offence at it; Sergei used to make the same salute to her uncle Lukyan when he had been captain. Lukyan could have punched Sergei clean through a bulkhead if he’d had a mind to, but what was the point? To deny Sergei his minor insubordinations would have been like denying him air.

Things were different now, of course. Lukyan was dead, and Katya was captain and owner of the little submarine, and it wasn’t called Pushkin’s Baby anymore. Also there was a war on. So many changes in so little time. It was good that some things could still be relied upon. Sergei being miserable, for example.

“Aye aye, Captain Kuriakova,” he said, his salute a thing of refined slovenliness that hung upon his brow like a dead eel. Belatedly, he realised what she had said and he dropped his arm to his side. “Atlantis? Do we have to?”

She waved the wad of scrips at him before returning them to the folder and stowing it away again. “Only way we’ll ever get these things turned into real money.”

“I know a man,” said Sergei. He had lowered his voice a little and was cautiously looking up and down the corridor alley connecting the pens. “And this fellow, he will buy the scrips off us, no questions asked.”

“Oh?” said Katya. “And how much ‘commission’ will he want?”

Sergei looked at her with astonishment. He still thinks I’m a little girl, she thought.

He mumbled something, mumbled it a little louder when she raised her eyebrows, and finally, provoked by her crossing her arms and leaning back in the seat, grudgingly admitted, “Fifty per cent.”

She shook her head in disbelief. “Are you serious? Is he serious? Six months of hard, dangerous work, and half of it goes to some criminal who–”

“He’s not a criminal,” muttered Sergei.

“He’s buying scrips at half price and then somehow cashing them in for full. That’s not legal. So, yes, some criminal who profits from half our work while he sits nice and safe.” She spat a descriptive term for the unnamed criminal that hadn’t been heard in the boat since Lukyan was alive, and which went a long way to assuring Sergei that, no, Katya was no longer a little girl.

Sergei walked forward and took the seat opposite her. When he spoke, it was in a quieter and more reasonable tone. She began to understand that this wasn’t just his habitual pessimism; he was truly concerned.

“Atlantis is dangerous, Katya. I’ve heard some real horror stories about the Yags attacking anything in the water near there.”

“I haven’t.”

“It’s not the kind of thing the Feds are going to advertise, is it? That they can’t even defend the volume around the capital?” He leaned forward, almost speaking in a whisper. “Things are going really badly for the Feds. Really badly.”

Katya looked at Sergei’s worried expression, but it did not soften her resolve. The truth, as far as the truth can ever really be defined in wartime, seemed very even-handed. Yes, the Feds were having a bad time of it, but the Yagizban were hardly swimming around without a care in the world. They may have had the technological edge, but they lacked numbers, and — since the FMA had captured one of their advanced war boats at the eve of the war — even that edge had been somewhat blunted. Several of its systems had been reverse-engineered, reproduced and incorporated into serving FMA vessels already. As for the captured boat, it was out there right now, fighting for the Federal cause under its new name, the Vengeance.

“The Feds located and destroyed a Yag spy base,” she countered. “It was all over the news just before we left.”

“Yes, but they would say that,” countered Sergei, much more inclined to believe the worst in any given situation.

“There were pictures…”

“You only have the Feds’ word for it that they were new. Could have been taken months ago.”

Katya closed her eyes and rubbed the bridge of her nose. Sergei recognised the gesture and became subdued. It meant she was finding a quiet place in her mind where she could make a decision, a decision that was not long in coming.

“We have to believe in something,” she said, tired and morose. “Right now, I have a strong belief that I need a shower and a night where I can sleep in an actual bed. Be ready to leave at oh-nine-hundred tomorrow morning.” She climbed to her feet and walked aft to the open hatch. Sergei sighed melodramatically, but did not argue. Like her uncle, there was little point in debating with Katya once her mind was made up. “I’ll book the departure with traffic control now,” she said as she climbed out. “Good night, Sergei.”

“‘Night, Katya,” he replied, but the hatchway was already empty.

She was in the traffic control office for fifteen minutes, five of which were spent waiting, four logging the departure, and six creating the course. The desk officer was irritated at first when she told him she didn’t have a course already plotted and would it be alright to use his console? His uniform denoted him as a major of the Federal Marines, and his prosthetic right arm was the likely reason he was now piloting a desk and for his generally spiky demeanour. While his comrades were off engaging the hated foe in battle, he was left ratifying civilian travel arrangements and issuing dockets. His irritation was rapidly soothed, however, by the speed and assurance with which she made the necessary calculations and by the time she had finished, he found it within himself to compliment her.

“My uncle used to say I was a prodigy,” she said with a wan smile.

“Your uncle? Well, he’s…” The officer, a lean man in his early fifties paused, his eyes upon the name of the submarine. “Ah. You’re Lukyan’s girl…?”

She could only nod. It still hurt even to hear his name.

The officer looked at her with a respect she did not feel she had earned. “He was a fine man, captain. Yes, he mentioned you, more than once.” He smiled a little bleakly. “The word prodigy was bandied around. Not just family pride as it turns out.” The console bleeped and showed a green light by the plotted course, indicating that it was acceptable by marine law and sensible within the complex flows of the Russalkin seas. The officer immediately authorised the plot and entered it into the log.

“My co-pilot is concerned about Yag activity near Atlantis,” said Katya. “Anything that we should know about?”

The officer shook his head. “A week ago I would have told you to wait or join a convoy. Nothing’s happened out there for days, though. It’s likely the patrols have driven the Yag out of the volume, but… be careful all the same.”

Katya picked up her identity card and her boat’s clock card and stowed them in her coveralls. “I always am. Good evening, major.”

Something happened on the way to the hotel. The route she used was a supply corridor that would have been off-limits to foot traffic during the day shift while electric tractors pulled cargo to storage areas and industrial sections. Once the lights dimmed, however, the corridors opened to pedestrians on the understanding that the occasional tractor would still be whirring by, so they should get out of the way when they heard one coming. The submariners were the only people to feel comfortable doing that; most stuck to the main corridors no matter what time it was.

Katya was making her way along the side of the long curved tunnel, when she heard footfalls approaching from the other direction. A moment later, two FMA base security officers — police officers in all but title — walked by her. One ignored her entirely, too busy adjusting the baton in his belt, the other stared straight at Katya as they passed, as if daring her to return the look. Katya did not; she had no desire to get into a battle of wills with them. At the very least they’d demand to see her identity card, and she was too tired for those kinds of status games.

They passed her without slowing and she kept walking, grateful that there was nothing between her, the hotel, and sleep. Nothing, that is, until she turned the corner and found the sobbing man.

He was crouched by the wall, his back to her, crying like a child in a pool of his own blood. Katya stopped sharply enough to make her boots squeal on the concrete. The man gasped with terror and looked furtively over his shoulder at her. She saw his nose was broken, and the white of one eye was bloodshot, the pupil blown.

“Oh, gods,” she managed. “What happened? Are you alright?”

The second question was almost as stupid as the first, but she’d had to say something. It was as plain that he’d been badly beaten as it was that, no, he wasn’t alright at all.

The bloodied eye looked past her, and she realised what he was looking for. “No, it’s alright,” she said in a quiet, reassuring tone. “They’ve gone. Why did they do this to you?”

He didn’t answer, but she saw the fear grow in him, and the tears mix with the blood and snot from his ruined nose. She saw the defence injures on the back of his hands as he cowered from her, at least two fingers on his right hand seeming broken; she saw his belt lying by his feet on the concrete floor; she saw the smashed teeth and the straight bruises, as wide as a baton’s contact area, across his brow.

They remained in tableau for long moments, the only sound the man’s miserable soul-deep weeping.

“I’ll take you to the medical centre, OK?” she said finally. She crouched by him. “I’ll take you to the medical centre. You’ll be OK.”

She didn’t ask again why the FMA officers had done this. It could have been something or nothing. She’d heard it didn’t take much to earn a beating these days — a word in the wrong place about rationing, how the war was being handled, how the Feds had their noses into everything — but she’d believed it had been exaggerated in the telling. It seemed she had been the one deluding herself.

The man shook his head, said something like, “I’m fine,” rose and walked painfully away from her, back in the direction of the docks. He leaned against the wall as he went, leaving a trail of bloody handprints, each dimmer than the last.

“That’s the direction they were going in!” she called after him, but he did not respond.

She called it in. She found a communications point a little further up the corridor and asked specifically for the major in traffic control. When she was put through, she explained what had happened, and that there was a man heading in his direction who desperately needed medical attention.

“I’ll alert a response team. Don’t worry, captain. He’ll be attended to.”

“What about the officers?”

The line was silent for a moment. “Did you actually see the assault?”

“No,” said Katya, “but there was no one else in the corridor. It had to have been…”

“That’s supposition. You’re not a witness. It will be dealt with, don’t worry.”

“But I am a witness, aren’t I? After the fact, but I’m still a witness. Don’t you want a statement or anything?”

Another silence. Katya suddenly wondered if the major was consulting with somebody else.

“That won’t be necessary. Base security can take it from here.”

Katya wanted to say, “But they won’t investigate their own people properly,” when she caught herself.

It really didn’t take much to earn a beating these days.

“I understand,” she said. “I’ll leave it with you, major.”

“Thank you for calling it in, Captain Kuriakova. Good night.”

The line closed before she could reply.

Katya looked back along the corridor. The man’s belt was still lying there. She turned and walked away, feeling she’d failed a test.

It wasn’t what you’d call a hotel. Many of the larger settlements contained hotels or hostels or similar establishments, but Mologa Station was too small for that. Originally a mining site, its tunnels cut by fusion torches in strange organic curves and meanders to follow mineral seams, Mologa was now primarily a heavy engineering plant producing boats and mobile facilities for the war effort, hence the tight security and strong Federal presence.

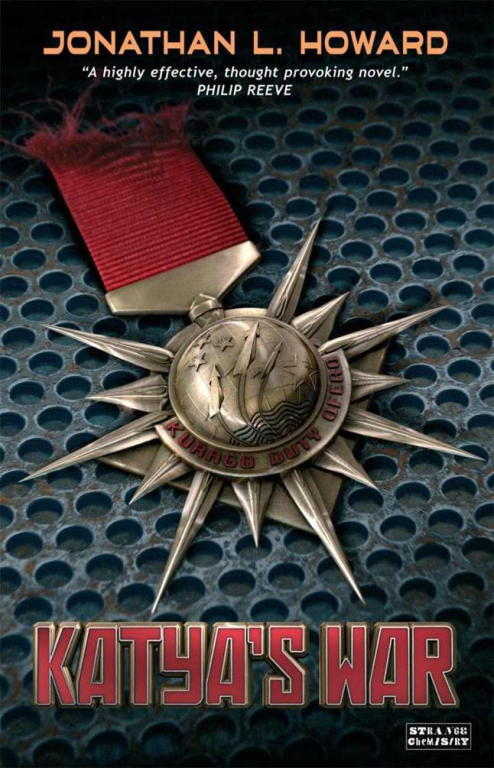

Katya’s security grade was Beta Plus, a full three grades higher than most civilians and the product of being in the FMA’s good books after the events of six months earlier, the very events that had begun the war. In the same waterproof container that held the boat’s papers and her personal documents was a small box made of wood.

Real wood. Real, actual wood, grown as a luxury in one of the larger hydroponics farms. Inside the box was a medal on a little red ribbon, upon which was her name, and the legend, Hero of Russalka. There was also a slip of paper, the citation for the medal, which explained why it had been awarded. It used a lot of words like “heroic” and “selfless” when talking about her, and “villainy” and “traitorous” when talking about the Yagizban. It also gave the date on which the honour had been presented to her. That was a little lie, though; the medal had never been presented to her at all. Instead it had been delivered by courier, who’d just had her submit to a retinal scan, handed over a package, and left. The box had been in the package, and the medal had been in the box.

She’d barely looked at the medal. Had read the citation once and experienced trouble finishing it, racked by embarrassment and a faint sense of disgust. It hadn’t been like that. It just hadn’t. But it was the official version now, and who was she to argue with the Federal Maritime Authority’s telling of events? After all, she had only been there, had only lived through it all.

The wooden box, though… the box she liked. Sometimes she would just hold the box, stroking its cover gently with the pad of her thumb, sensing the fine grain against her skin. What must it be like to see trees just… there? Growing where they liked, randomly dotted about?

Still, this was nature, too. Stone was natural, even if the torches had melted it smooth. She hadn’t needed to follow the signs to the Mologa Hotel — she’d been there often enough — but lost in her reverie, listening to her own tired thoughts and the sound of her boots on the decking grates, it was a surprise when she turned a corner and there it was. Mologa Hotel, a long, dimly lit tunnel with staggered rows of hatches set into each wall. Admittedly, it looked more like a mass morgue, but it was better than nothing.

She walked along, looking for a green vacancy light. Unsurprisingly, the ones nearest the tunnel entrance all showed red “Occupied” flashes with a few amber lights to show freshly vacated units that still had to be cleaned before being designated available again. She had little idea of how often the units were cleaned out. Perhaps twice a day, she guessed. It didn’t matter; she would do what she always did and walk most of the way along, and pass most of the two hundred capsule “rooms.” That far along, she was already walking past plentiful numbers of greens and some ambers. She deduced that whoever was supposed to clean the capsules perhaps only bothered with the far end of the tunnel once a day, maybe less. Once she might have been outraged at such a dereliction of duty. Right now, however, she just wanted to sleep.

She found a capsule that was identical to all its neighbours, but that she took a shine to on a whim. Her boat’s docking fee included two capsule rentals, one for her and one for Sergei, although she suspected he’d sleep aboard again. Over fifty hours in that confined space apparently wasn’t too much for Sergei Ilyin. Well, good luck to him. She swiped her ID card, waited for the click, and swung the door open.

In the same way that you couldn’t really call it a hotel, you couldn’t really call it a room. It was no more than a burrow a metre and a half square at the entrance and two and a half metres deep. The walls were covered with a smooth epoxy coating in a “restful” shade of pale blue that was apparently what the sky looked like on Earth, and which the primitive parts of their minds found comforting, or so she was told. The floor of the capsule was covered by a mattress that could be removed and hosed down for cleaning if need be, and there was a clean blanket rolled up to one side. Set into the ceiling above where the occupant would lay their head was a screen on which could be watched a selection of dull programming, available on demand. Beneath the capsule floor was a cubby for putting boots, and Katya sat in the hatchway while she removed them and her thin socks before storing them in there. When she crawled in and closed the hatch behind her, the cubby was covered and kept secure, too.

She struggled out of her clothes, made more of an attempt at folding them than she felt was really necessary, and ended up tossing them into the alcove at the capsule end along with her overnight bag. She pulled the thin blanket over herself, more from habit than necessity as the temperature was maintained at a comfortable level, set the alarm for oh-seven-thirty, and turned off the light.

She couldn’t sleep. Tired and listless, she was desperate to, yet her disloyal head kept buzzing and denied her the ease she needed to drift off. She wished she hadn’t mentioned her uncle to the major in traffic control, wished he hadn’t known Lukyan, hadn’t said he was a good man. Yes, her uncle had been a good man, and she missed him so much that it hurt. She felt the tears and did nothing to stop them. It was natural to grieve, even months later. She knew it would be months more before the pain stopped being quite so sharp, when it didn’t make her wish she had died along with him.

Each capsule had half a metre of stone between itself and its neighbours, and the doors were designed to be soundproof, but even so this was why she always chose a capsule as far from others as possible, so nobody might hear her cry.

Sergei had cried. In the pause between the threat of the Leviathan killing everyone on the planet being lifted, and the beginning of the civil war that threatened to result in everybody killing one another instead, she had got back home and sought him out immediately. She had to be the one to tell him, it was what Lukyan would have wanted.

She had stood there, willing herself to stay ramrod straight, and told Sergei that his captain, her uncle, his best friend since childhood was dead. Death wasn’t so strange on Russalka, after all. The dangerous world killed people all the time for the silliest mistakes and the most fleeting of inattentions. Sergei was made of tough stuff, she had told herself. He’d take it stoically.

But he didn’t. He sat down heavily on the floor — on the floor! — and cried like a child. There was no denial, not a single “Are you sure?” She said she’d been there, told him how Lukyan had died, and that was enough. He’d sobbed and looked ridiculous, his face red and snot running out of his nose, and he hadn’t cared. Finally she’d sat by him, put her arm around him and cried too. Her tears had been silent, though.

Perhaps Sergei had been wise after all. He had come to terms with his grief quickly and accepted Lukyan was gone forever, his lifelong friend lost for good. She still saw him grow quiet and reflective sometimes, and he might touch the corner of his eye as if dust had got into it, but that was all.

He didn’t spend his nights crying himself to sleep in a soundproof cell.

Quarter of an hour later she felt exhausted, puffy-eyed, and again empty of grief and the guilt of the survivor for a while, at least. But, she did not feel sleepy. This seemed very unfair.

Finally she gave up trying to will herself into unconsciousness. Instead she found the gently illuminated controls for the screen and switched it on — perhaps she could bore herself to sleep.

The first feed was an old action drama she was sure she’d seen years before and which hadn’t been new even then, made during or just after the war against Earth. It was about an isolated station where a Fed boat has to stop to make repairs and finds itself stuck there with some refugees. Somebody amongst them is a traitor working for the Grubbers and there was a lot of stuff with people accusing one another and then something else happens that means the accused person must be innocent, and so they accuse somebody else.

That the villain turned out to be a Yag — even though he’s really a Grubber infiltrator — was probably why they were rerunning such a steaming piece of melodrama about the war in the first place.

The war. Katya realised that nobody had yet got around to coming up with a name for the new conflict. When people said “the war,” they always meant the war against Earth, the war that was eleven, almost twelve years ago now. It was a civil war they were currently fighting, but nobody called it that. Nobody called it anything at all.

Katya changed the feed and found herself watching a news channel. There was little new here; the Feds were doughty and honourable warriors while the Yag were dirty, sneaky scum who it turned out had been colluding with the Terrans during the war.

Being caught out as traitors hadn’t really been the declaration of independence the Yags had been planning on, but you can’t always get what you want, can you?

Katya turned down the sound and dimmed the screen brightness. She lay in the flickering darkness watching earnest newsreaders, pictures of smiling Federal sailors and marines coming back from successful sorties, a few bedraggled and wretched Yagizban prisoners being paraded for the cameras, public information proclamations, some newly decorated hero going back to his old school to give a speech about duty and honour. It was just another man in a dark blue FMA naval uniform until he took his cap off for the cameras and she laughed with delighted surprise.

Suhkalev! From spotty little thug to a “Knight of the Deep” as the caption proclaimed him, and all in only six months. They’d given him a medal and everything, just like they’d given to her.

Look at us now, Suhkalev, she thought. Look at us with our medals, heroes all. Knights of the Deep.

She finally passed out soon after that, the screen still flickering images of resistance to the enemy and glorious victory above her face. Her mouth moved, and she may have been saying “Knights of the Deep” as she sank into unconsciousness, then she half laughed, and then she was asleep.

CHAPTER TWO

Jarilo

Katya awoke in total darkness. Her first thought was a power failure, but then she realised it couldn’t be — every station had back-up generators and slow-bleed capacitors to ensure a total power failure could not happen. After all, a facility without power would be a facility without life before very long. It was more likely to be a local failure, she thought, probably a power bus to the hotel had simply overloaded and was waiting to be reset. Well, if the power had failed, so had her wake up alarm. Sergei was probably down in the pens right now, tutting and muttering as they lost their departure slot.

She checked her chronometer and was nonplussed to discover its face dark. Fumbling with its buttons didn’t produce even a flicker of illumination. Now she was becoming worried; a local power failure was one thing, but even personal electronics dying? Probably just a coincidence. Probably. The possibility that the Yagizban had triggered some sort of electro-magnetic pulse weapon and scrambled Mologa’s electronics entered her mind and was just as quickly dispatched. Every station’s electronics were gauss-hardened against EMP weapons and had been since the war. No, something else was going on here. Well, lying in the dark wasn’t going to give her any answers.

She started to reach back to get her clothes when a sudden sharp sound made her freeze — a single loud crack, shockingly close. She froze, her heart suddenly pounding very fast and hard which only served to dull her hearing as the beats sounded through her head. She stayed still for ten, twenty, thirty seconds, but the noise was not repeated.

The silence was less reassuring than she had hoped. Then she realised how absolute the silence was. The tiny yet infinitely comforting sound of the ventilation fan was absent. While she doubted it was possible to suffocate in a capsule room, she didn’t care to find out. Besides, the air was growing cloying and hot. She reached for her clothes again, and as she did there was the same awful cracking noise, but this time it continued, and grew. A heavy splintering, a grinding of stone upon stone. The realisation that the stone around her was suffering some sort of structural failure filled her with urgent terror.

She decided she would rather face the humiliation of being on the corridors in her underwear than stay in the capsule a second longer and abandoned her clothes in favour of getting out. As she sat up, however, her forehead banged forcefully into the screen mounted on the capsule ceiling. The screen was probably undamaged, being a flexible polymer laminate sheet, but directly behind it was a single insulation layer and then solid stone. Katya fell back, her head landing on the pillow pad. She blinked away the pain and tried to understand how she could possibly have hit her head on a ceiling that had given her comfortable space to sit up the previous night. Now the ceiling seemed to be lower. How was that possible?

There was another loud crack, the grating of stone against stone, and she finally understood. The capsule’s collapsing, she realised. Move! Move! Move!

She tried to sit up as far as the ceiling would allow, but now it was barely above her face. She started shuffling towards the hatch as fast as she could manage. The hatch’s locking handle would be a problem, but perhaps she might be able to disengage it with a kick. She had hardly managed to get five centimetres before the smooth plastic of the screen brushed her face. The ceiling didn’t seem to be lurching down at all, but smoothly descending like a hydraulic press.

She tried to move but it was bearing down on her now, pushing her backward into the shallow mattress. She squirmed hopelessly, her face to one side. How had this happened? Had the station been hit by some new and strange weapon of the Yagizban?

The ceiling stopped its descent. Then, with another crack of fracturing stone, it slammed down.

Katya felt her bones break and break again. She felt her skull compress and shatter as millions of tonnes of submarine mountain settled on her. She felt little pain, but only an odd sense of regret as her skeleton splintered, her tongue was crushed, her eyeballs exploded.

And she did not die.

She was smeared, an atom thick, between the rock faces.

And she did not die.

She could feel the mass of the mountain, feel the shift in the drowned continental plate on which it stood, feel the countless billions tonnes of water flow across the planet’s surface drawn by an unseen moon beyond the unending clouds.

An atom thick, no, thinner yet, as thin as thought, she enveloped the planet Russalka. Russalka — she’d always thought it a good name, but now she realised it was too small to encompass everything the world was. She could almost reach out and…

The alarm was a relief and a huge frustration. The cubicle lights came up gently along with the slowly increasing volume of the alarm tones, and Katya found herself whole and sweating in the capsule room that showed no signs of wanting to be any smaller than it already was. She reached out reflexively and muted the alarm, looked up at the silent screen where the news was always changing yet reassuringly similar. Fierce battles, broad victories, solitary and inconsequential defeats, proud Feds, subhuman Yags.

Her mind was still echoing with her dream, though. A dream of a united planet. She had felt good, powerful, and another emotion that she equated with confidence yet had been somehow different.

Not such a bad dream, then, although she could have done without the bit about being crushed into liquid. That had been… not so enjoyable.

She struggled into her old clothes, grabbed her overnight bag and left the capsule, its red light snapping over to amber as she swiped her card again and tapped the “Checking Out?” square on the status screen mounted on the outside of the hatch. Now, she decided, before she did anything else that day, she desperately needed a shower.

Twenty minutes later, clean, in fresh clothes, and the last echoes of her dream fading, Katya joined Sergei in the station cafeteria for breakfast. He stirred his scrambled eggs (in reality a 1:3 ratio of Edible Protein Reconstitutes 78 and 80b) onto his slice of toast (Carbohydrate Staple Complex Synthetic — Bread 15, although at least it had seen the inside of a real toaster), and glowered across the table at her. He looked exactly as he always looked. His disreputable coveralls never seemed to get any dirtier, his moustache was never any longer or shorter, his stubble was always one missed shave old.

“What are you so happy about?” he demanded, then shovelled some “egg” into his mouth as if he expected it to be taken from him any moment.

“Had a strange dream,” she replied. She was eating kedgeree. The egg was as synthetic as Sergei’s, the rice was reconstituted starch pellets, and the spice paste had come out of a laboratory somewhere, but at least the fish was real. “I saw the whole world. I was the whole world, sort of. Y’know, Sergei, there’s not a problem that can’t be solved. I think we’re going to be OK.”

Sergei’s shovelling stopped. “God. If you’re going to be like this all day, I’m resigning now.”

“Seriously? OK. We both know I can handle the boat alone and the navy’s desperate for hands, so just hand in your reserved occupation papers and get yourself into uniform. Oh, and you’ll have to keep it clean. They’re pretty fussy about that.” She smiled sweetly at him.

He looked at her stonily. “I bloody hate you, Kuriakova,” he said, and returned his attention to his breakfast.

“‘I bloody hate you, Captain Kuriakova,’” she corrected him. “I will have discipline within my crew.”

She carried on eating, having duly noted Sergei struggling not to smile.

“Wake her up, Sergei.”

They were aboard the boat, set to go with a small cargo of assorted parcels, mainly intended for friends and family of Mologa’s military staff at Atlantis. That and a few data sticks containing messages in written and video form, both official and personal. Lines of communication were often among the first casualties in wartime. The landlines, never very reliable, had mainly been severed by enemy action, and the surface long wave relays — tethered communication buoys floating above the settlements — were too easy to intercept and jam. That’s if some enterprising raider didn’t slap them with a couple of torpedoes, of course. With rapid communications difficult, almost everything had to be done by couriers.

Katya had noticed among the parcels some actual letters, forming their own envelopes with a tab of tape to seal them.

“Letters. Imagine that,” she’d said, waving one of them at Sergei. “Writing. On paper.” Sergei had said nothing, so she’d added, “Amazing!” to emphasise the novelty of it.

“People sent letters on paper in the war,” he’d said. It was an extruded fibre weave, but it looked and behaved in much the same fashion as real wood pulp paper, the kind they had on Earth. “Sometimes, y’know, sometimes words on a screen aren’t enough. You want something you can carry with you. Sometimes it’s all that’s left of someone.”

Now the bags were stowed, and twenty hours of submarine travel awaited. Twenty hours of brain-freezing tedium, possibly mixed with bouts of bowel-loosening terror should the major in traffic control be wrong about local Yag activity. At least, Katya reflected, the cess tank was empty.

It was the co-pilot’s job to run down the pre-launch checklist, and the captain’s to oversee it, so Sergei counted off the items and called “check” at each positive, and it was Katya who watched him do it. It was ridiculous, she thought. In her entire maritime career to date, she had done that job once. Once, and only once, she had been co-pilot/navigator. Then she had inherited the boat and become captain. “A battlefield promotion,” Uncle Lukyan would have called it.

She snapped herself out of her reverie before it could become maudlin, and listened to Sergei finish the list. “All lights green, captain. All systems go.”

Katya opened the communications channel to traffic control. “We’re clear to disengage, traffic control. No last minute reports of Yag boats in the vicinity?”

“Nothing new, captain.” She recognised the voice of the major. “I can only recommend you stay sharp, and take care. Launch when ready, RRS 15743 Kilo Lukyan. Good luck.”

“Thank you, major,” replied Katya. “Disengaging now. Lukyan out.”

With a thud as the docking clamps released the boat, and the hum of the impellers taking them out into open water, the voyage was underway.

It had seemed like a good idea at the time, renaming her uncle’s boat from Pushkin’s Baby to the Lukyan. It had seemed like a good way to honour him, to remember him. But now every time the boat’s name was used, she had to fight the urge to look at the left hand seat to see if he was there. Really, that should have been her seat as captain, but she just couldn’t bring herself to take it. She felt a big enough fraud calling herself “captain.” Claiming the captain’s seat, Lukyan’s seat… no. That was too much.

Sergei hadn’t wanted it either, but he had seen how she looked at the seat almost superstitiously and decided that he was going to have to be the stoic, pragmatic one. He didn’t like it, though, and had spent much of the first couple of months complaining that the seat felt wrong, that no matter how he adjusted it, it just felt wrong.

Katya steered until they were clear of Mologa Station’s approach volume and then switched on the autopilot. The inertial guidance systems took what data they could from the baseline of Mologa’s precise location on the charts and took over, taking them on a slow downward gradient into seabed clutter to try and make them a difficult contact to acquire should a Yagizban boat happen by. In peacetime, echo beacons along the way would have provided route correction, but they had all been closed down now. Anything that might help the enemy was to be denied to them, even if it inconvenienced your own people.

“Arrival at Atlantis docking bays in nineteen hours, forty eight minutes,” said the Lukyan’s computer voice in the same calm tones that it announced everything from waypoint arrivals to incoming torpedoes.

Katya lifted her hands from the control yoke and watched it move by itself under the autopilot’s direction. “I sometimes wonder why boats even have crews anymore.”

Sergei was already climbing out of the left hand seat, and was glad to do so. “They used to use drones. Then we got pirates after the war. Drones aren’t so great when it comes to out-thinking people who are after your cargo.” He sat in the forward port passenger seat and pulled the table down from the ceiling on its central strut that swung down to the vertical and then telescoped out. He pulled up the screen on his side and gestured impatiently at the opposite seat. “Well?”

Katya left the co-pilot’s position and climbed into the indicated seat. “What are we playing?” she asked. “Chess?”

Sergei curled a lip and tapped some keys. Katya raised the screen on her side to find a virtual card table already waiting for her.

“Poker,” he said. “A proper game, with risk and chance. Just like life.”

They played a few hands until Sergei said he was feeling tired again and was going to take a nap. Katya noted that his energy seemed to have a direct correlation to how well he was doing in the game. After a disastrous losing streak that would have cost him his wages for a year had they been playing for real money, he was entirely exhausted and was horizontal across two passenger seats and snoring a minute later.

“Your choice, my friend,” said Katya under her breath, logged when he fell asleep and set that as the beginning of his down shift. He would argue about it when he woke up in thirty or forty minutes’ time, but it had been one of Lukyan’s hard and fast rules. If Sergei had ever thought Katya was going to be a soft touch, he was well on his way to re-education now.

As it was, he actually woke twenty-three minutes later when Katya threw an empty beaker at his head. He struggled upright, swearing copiously until she told him in a harsh whisper to shut up and quiet down. The realisation that the drives were off and they were drifting in the current was enough to calm him instantly. He was up front, headset on, and seat restraints locked inside ten seconds.

“What is it?” he whispered. “Yags?”

“Don’t know yet,” she replied. “Just caught a glimpse of something on the passive sonar. One-oh-five relative. Might be nothing. Better safe than sorry.”

Sergei nodded. “Better safe than dead.” He noted the concentration on her face and knew she was listening through the hydrophones, the submarine’s “ears,” for the sound of engines. Without needing to be told, he pulled up the passive sonar interface on his own multi-function display and started a slow, careful scan, quadrant by quadrant.

Five minutes passed. Ten. At fifteen Katya was about to call it off as a false alert when something showed on the passive sonar at fifty degrees high relative to their heading. She immediately brought the hydrophone array to bear and listened intently.

“A shoal?” asked Sergei with unusual optimism.

Katya shook her head slightly. “I hear a drive. Lock it up at my bearing and give me an analysis.”

Sergei told the passive sonar to lock onto the hydrophone bearing and ran the sound through the database. “It’s military.”

“Yeah. She’s no civilian.” Military boats carried engines with much higher performance than those of civil transports and carriers. Their turbines ran at greater speed and generated a very distinctive tone that every sensor operator knew. There was still a chance it was a Federal boat combing the Mologa approaches. Not even three hours out and a Yag warboat sniffing around? It seemed… all too likely. The ocean deeps were vast and even a large carrier could shuffle around out there with a whole fleet looking for it and probably stay safe. The station approaches, though… there the game went from looking for a fish in an ocean to looking for a fish in a bath. It was dangerous for the hunters if the station defences picked them up, of course, but war is all about risks.

Another twenty seconds of tracking the unidentified contact passed before the computer decided it had enough information to offer its analysis. “Eighty seven per cent likelihood contact Alpha is a Vodyanoi/2 class hunter-killer submarine of the Yagizba Enclaves,” it told them. “It is therefore designated an enemy.” And to show them what it thought of enemies, the computer changed the contact’s symbol on the sonar display from yellow to red.

“A Vodyanoi?” said Sergei hollowly. He had gone very pale, or at least his stubble seemed much more clearly defined. “One of their new boats? The Grubber design? It would be.” His tone was bitter. “We’ve never dealt with one of those before.”

It wasn’t good news. The Yag’s Vodyanoi/2 class was a development of a Terran boat called the Vodyanoi, the vessel of the notorious pirate Havilland Kane, no less. She had met Kane, and she had been aboard the Vodyanoi. It was a highly sophisticated boat, but she knew the Yag copies were not its match; necessary compromises had to be made in their production to keep down costs, and some aspects of the original’s technology were beyond Russalkin manufacturing methods. Even so, the Vodyanoi/2s were dangerous predators. If it got a clear lock on them, they were as good as dead.

So, they did the only thing a minisub could do against such a killer; they remained quiet and hoped for the best.

“Do you think they’d hear our ballast tanks vent?” said Katya in a whisper. When you knew people who were keen on the idea of killing you weren’t very far away and were actively listening for you, it was difficult not to whisper. “We’re about fifty metres above a thermocline. We’d be a bit safer under it.”

Sergei shook his head. “I know it’s tempting, but it’s best not to do a thing, Katya. If they’re low on munitions, they might not bother, but if they’re flush, they might stick a fish in our direction on a search pattern, and then we’d be pretty screwed.”

By “fish,” he meant “torpedo.” By “pretty screwed,” he meant “very thoroughly dead.”

Katya knew good advice when she heard it, so she leaned back in her seat and crossed her arms so she wouldn’t be tempted to press any buttons just to relieve the tension.

The only thing they could do was watch the sonar screen as the passive return grew stronger. The Yag boat was heading almost directly for them; it would pass by about three hundred metres above them and a little in front. It would be a close call whether they ended up in its baffles — the conical volume astern of a boat in which its own engines blinded its sonar.

Katya had no idea how broad a cone that was. If they were hidden by the Yag’s engine noise, they could risk the descent to the thermocline and hide behind the layer of the water where the temperature above was lower than that below, and which could reflect sonar waves. If they weren’t, however, the Yag would hear the air venting from their ballast tanks as they gained negative buoyancy, and then the Yag would kill them. Given how nice a boat the Vodyanoi was, she reckoned its baffles were small, and that the baffles of her clones might be small too. It wasn’t worth the risk.

Katya kept her arms very folded.

Sergei leaned forward. “What the hell is that?” he murmured.

Behind them, a new trace had appeared. If they had been under way the contact would have been lost in their own baffles. Only that they were running silent permitted the sonar receptors to pick up the new contact. Katya quickly brought the hydrophones to bear. Any faint hope that it might be a Federal patrol boat was quickly shattered.

“Ninety per cent likelihood contact Beta is a Jarilo Mark 4 class heavy carrier submarine of the Federal Maritime Authority,” the computer told them. “It is therefore designated an ally.” The contact’s symbol flicked from yellow to blue.

“A transporter,” whispered Sergei. “It’s bound to have an escort!”

On the screen, the Alpha contact slowed and faded. The Yags were coming about for an attack pass. “They’ll fire and run,” he said. “Those poor bastards…”

Katya’s eye fell on the database readout currently displayed on one of her secondary screens. The Jarilo was listed as having a standard crew of twenty. Twenty men and women who would probably die in a few minutes. Then its unseen escort or escorts would engage the Vodyanoi/2 and soon there would be more blood in the water.

“No,” she murmured. “I can’t let that happen.”

CHAPTER THREE

False Flag

Sergei’s eyes were unattractively wide. Fear did that to them.

“Katya, we can’t get involved! We’re in a minisub, a tiny bug! Even a close detonation will break us open!”

“Then we’re just going to have to make sure nothing goes off near us then, aren’t we?” Katya was already pulling up the operations screens. “Arm a noisemaker and stand by to dive.”

Sergei did neither. “What? No! You’ll kill us!”

“Not part of the plan, Sergei. Just do it.”

“What plan? We’re nothing more than krill compared to the hunter-killers out there! Just stay still and silent and we should weather this out!”

“I am not standing by and letting this happen, Sergei. Noisemaker! Arm one!” But Sergei just looked at her as if she was insane. “I am the captain here, Sergei Illyin! You will obey my orders!”

On the screen the Alpha contact faded away entirely. The Beta contact in contrast grew steadily stronger. It would only be a matter of moments before the Yagizban boat launched torpedoes.

“You can’t order me to commit suicide,” said Sergei. “Captain.”

Katya glared at him, then turned her attention to the controls. In a few quick moves she had frozen Sergei’s work station out and taken full control of the Lukyan.

“Noisemaker 1 armed,” reported the computer. Katya checked the settings she’d given it, and then flipped the cover on a “Commit” button. As a security and safety measure, some functions could not be activated through the touch screens — it was far too easy for accidents to happen that way. These functions, many of which were associated with weapons, had to be confirmed with the actual push of a physical button. Technically, noisemakers were considered weapons in terms of their interface functionality and the fact that they were expendable and expensive supplies. Nobody wanted to launch one accidentally. Katya’s fingertip hesitated for half a heartbeat, and then pushed the button with a sense of finality.

A slight click sounded through the hull as the noisemaker’s mounting clamp released it. “Noisemaker 1 away,” said the computer.

Katya made a point of not looking at Sergei; she knew full well what expression he would be wearing at that moment and it wouldn’t be one that bolstered her confidence.

Without pause, she opened the tactical options sheet on a secondary screen and ordered a slow descent below the next thermocline. The computer gauged that they would reach it in about ten seconds, which was encouraging as that was the timing she’d based the noisemaker’s programming upon. Now she could only hope that the Yagizban would not open fire in those ten seconds, that her plan — such as it was — would work, and that they didn’t get killed in the next few minutes.

Dying would be bad enough, but having Sergei spending their last moments saying “I told you so” would be more than she could bear.

The passive sonar did not report torpedoes in the water, which didn’t surprise her at all. She’d seen enough of the military to know that they didn’t like jumping in when there was still uncertainty about the situation. In this case, the Yags had almost certainly picked up the sound of air venting from the Lukyan’s ballast tanks and were wondering what was out there that they hadn’t yet detected. That was enough to take the finger off the firing button.

A moment later the Lukyan sank through the thermocline and immediately adjusted its tanks to neutral buoyancy in the shadowed space there, where sonar waves tended to behave unreliably. As they breached the thermal layer where the water temperature changed abruptly, a hundred metres above them, where it had been lazily rising from its release point, the noisemaker burst into life. Essentially a small torpedo with a motor that mimicked the sound of a larger boat, the Noisemaker 1 set off on its maiden and final journey, straight towards the presumed location of the Yagizban Vodyanoi/2 warboat.

Noisemakers were clever devices, but the fact remained that their impersonation could only be reasonably convincing and no more. Inside a minute the Yag boat would have identified inconsistencies in the hydrophone data and the noisemaker would be subsequently ignored. A minute is a long time in a battle, however, and now things started to happen rapidly.

The Jarilo, more than aware that stealth was not its strong suit, anticipated that it was probably already on an enemy’s scopes and decided to respond aggressively. A focused cone of sound energy sped out from its bow as it emitted a directional sonar “ping.” Suddenly the Yagizban’s stealthy manoeuvring was all for nothing as it lit up brilliantly on the sonar screens of the Jarilo, the Lukyan, and doubtless the one or more Federal warboats shadowing the transport.

Instantly the situation changed from a stalking game to a straight fight. The Vodyanoi/2 launched one torpedo and changed course dramatically, diving for the thermocline itself. “Oops,” said Katya more mildly than this development really deserved; in a moment the Yagizban warboat would be on the same side of the temperature differential as them, and it would be able to see them easily.

Discretion would definitely be the better part of valour, she decided, and opened the throttle to one third ahead. It had turned into a game of judging the angles; she needed the Lukyan to get into the Yag’s baffles while at the same time not exciting the curiosity of the Jarilo’s escort — who, a bleep on the display informed her, had just launched a torpedo themselves — because in the confusion of a submarine battle, the Feds would be sure to fire first and run a sonic profile analysis later. They would probably be very sorrowful about sinking a Federally registered minisub, but then shrug, say “That’s war” and ask what’s for dinner.

She made an educated guess where the rapidly fading trace of the Yagizban boat was heading and what its bearing was; drew a line that should be, more or less, its blind spot, and piloted the Lukyan into it. Beside her she could hear Sergei breathing heavily, possibly with fear, possibly with anger, most likely both. If she got them out of this alive, there was going to be a monstrous argument afterwards, of that she was sure. For the time being, however, she was entirely focused on the “getting out of this alive” aspect of their immediate situation.

She turned the Lukyan to starboard and headed away, hoping for the best. The hydrophones were full of the sound of control surface cavitation, torpedo drives, and noisemakers being shot off in all directions, all of which boded well — the big boys were too busy with one another to worry about a little bug like theirs. There was still the possibility of a torpedo performing a search pattern picking them up, but every second they ran broadened their chances. After ten minutes Katya and Sergei were breathing more easily. After twenty they were as sure as they could be that they’d escaped the battle. Katya slowed to a crawl and “cleared the baffles” to be sure, performing a quiet three hundred and sixty degree circle that allowed the sensors to scan the entire environs. There was nothing out there but the kind of fish that doesn’t carry a warhead.

Still Sergei said nothing. In the heavy silence, Katya hand-plotted a change to the logged route that would take them around the battleground and then back on course for Atlantis.

Finally, she’d had enough of it. “Speak up or stop making that faulty valve noise with your nose, Sergei. You’ve got something to say. Let’s hear it.”

For several seconds he just stared at her as if he’d never really looked at her before and didn’t like what he saw. Then he said, “Why? Why did you do that?”

“The Jarilo didn’t stand a chance. We had to do something.”

“No,” he replied with cold emphasis. “We didn’t have to do anything. We’re just a little boat keeping its head down and out of trouble. We can’t change anything. Don’t you get it?”

Katya looked at him and some of that sense of revelation came to her, too. Sergei was afraid. Sergei had always been afraid. All these years she had seen him just as an adjunct to Uncle Lukyan, or even to the boat, a sidekick to one, an organic module of the other. She had never really looked at him as a person, and what she saw disturbed her and, to her great sorrow, disappointed her. He was just a man with small dreams and small hopes who’d latched onto Lukyan and followed him wherever big, bluff Lukyan wanted to go. All he wanted in life was a steady job and not to be afraid, and not being afraid meant never taking risks.

Once, not so long ago, she would not only have sympathised, she would have agreed with him wholeheartedly. The world had been much simpler then. Now, however… now she’d seen the kind of people who start wars at first hand. The experience had not filled her with confidence that they would be doing everything in their power to bring things to a peaceful conclusion. The FMA was furious with the Yagizban because the Yags had betrayed them not once but twice, first conspiring with the Terrans during the war, and then by preparing for a Terran return that never came. For their part, the Yagizban were sick of the Federals for getting into a war with Earth in the first place, and then using it as an excuse for never-ending martial law. They would fight like zmey over a manta-whale carcass, until one of them was dead, and the manta was torn to pieces.

“No, Sergei. I don’t get it. Not anymore.” She turned her attention to the controls. “If you want to resign, I’ll give you a good reference.”

She’d suggested much the same at breakfast, but then it had been in jest. The hard truth was resignation really did mean being promptly conscripted into the Federal forces. By the time she realised it was a threat, the chance to withdraw the comment was gone. Misunderstandings, she thought. This is how wars start.

The following seventeen hours were not the most comfortable either of them had ever spent. Sergei was surlier than usual, and barely spoke. Katya tried to jolly him along for the first couple of hours, but grew tired of his wilful recalcitrance and was soon only speaking to him when she needed to. There was no chance of any more hands of poker and certainly none of a game of chess, so she pulled up a book on a non-luminescent plastic paper screen and read to pass the time. The Russalkin loathing of all things Terran perhaps unsurprisingly did not extend to Earth art in general and literature in particular, so she felt no tremors of spiritual treason in reading a book called Moby Dick. It was about a man who had grown obsessed with hunting and killing a sea monster, a great white whale in one of the Terran oceans. Katya doubted it would end well.

It was a relief for both of them when they picked up the Atlantean approach markers, and even when they were interrogated at torpedo point by a patrol boat, because at least it gave them something to focus on outside the toxic levels of animosity inside the Lukyan. With the patrol boat captain’s suspicions allayed, they were permitted to enter the minisub pens on the western side of the largest pressurised environment on the planet. Some of the Atlanteans went so far as to call it a city, but cities were a grubby Terrestrial conceit, and the term had never really stuck. Its population of a million and a half did make it comfortably larger than any other base or station, however, and it was large enough to support non-vital services.

Katya had heard that Atlantis was the only place on the planet where it was possible to forget that the Yagizban were trying to kill you, at least for a while. There was no chance of that during a three-hour debriefing, however. It was necessary to hand in a journey report to the authorities on arrival. Usually this simply consisted of a copy of the logged course, a plot of the actual course taken, and a brief description of anything that might be of interest to the FMA, although by far the most common style of report was the solitary sentence, “Nothing to report.” An actual plot that deviated wildly from the logged course and a description that included the phrases “Vodyanoi/2 warboat,” “Jarilo transport,” “anticipated ambush,” “noisemaker launched,” and “torpedoes detected” was never going to go by with a mildly interested nod from the authorities.

By the time they were released, they had been awake for over twenty-four hours with only a few short catnaps, and tiredness made Katya and Sergei even snappier with one another, especially since Sergei appeared to harbour a suspicion that their lengthy debriefing had been all part of a surreal plan of Katya’s to make him even more miserable.

They walked down the main southern promenade of the settlement silent and angry, barely exchanging a word.

It was a shame they were so tired and so ill-tempered, because Atlantis was like no other place on Russalka. It had actual shopping “streets,” wide concourses with recessed shops and freestanding stalls selling admittedly minor variations of each other’s stock. Once, Katya knew, these stalls had also dealt with goods brought in from the other Earth colonies, but that was before the war, when Russalka still had ships capable of reaching their near neighbours. Now there were some odd trinkets, curiosities like bone coral growths and the preserved forms of some of the more unusual fish from the world ocean. One stall was even topped by the massive skull of a zmey — a sea dragon. Neither Katya nor Sergei had time for any of this, though; both wanted sleep and to be out of one another’s company; and they wanted these things as soon as possible.

When the Federal officer and two troopers stopped them, it just seemed like another lousy thing to top off another lousy day.

“Captain Kuriakova?” said the officer. Katya had the impression of a tall and efficient woman in the uniform, but what raised her concerns most was the small black insignia at the end of the officer’s rank patch on her left breast pocket. She was a captain in Secor, the Federal security organisation. When Secor took an interest in your business, it never boded well. There were grim little rumours about Secor arresting those they found suspicious, spiriting them off to remote secure facilities like the Deeps or R’lyeh, where they would be interrogated, perhaps tortured, and dumped out of an airlock when Secor had squeezed every drop of useful information out of them.

“I… Yes?” said Katya, promptly wishing she hadn’t admitted to her identity, and then immediately glad she had. It didn’t pay to lie to Secor. That might make them angry with you, and that might make you dead.

“We have some questions for you,” said the captain. Her tone was officious and curt. “You will come with us.”

“What? But we’ve just been debriefed once.”

“Irrelevant. This is Secor business.”

To his credit, Sergei was having none of this. “We haven’t slept in over a day, captain,” he said, managing to be courteous for once. Speaking to somebody with the power of life and death, with an unpleasant period of “harsh” interrogation between the two, can have that effect. “Can’t this wait?”

The Secor captain looked at him as if Sergei was something that might be found in a cess tank. “And you are..?”

Sergei had an awkward habit of saying the wrong thing at the wrong time and getting himself into trouble. Katya stepped in to stop him coming out with anything they might both regret. “He’s my co-pilot. Do you need both of us, captain? I’m fine going with you, but my co has business to attend to.”

Sergei shot her a “What are you playing at?” expression.

“The cargo still needs to be handed over to the dispersals agent at the dock. Yes, yes,” she stopped him interrupting, “I know I said we could leave that until we’d had some rest, but we’re overdue as it is. People are waiting for those parcels and letters, Sergei. We should hand them over as soon as possible.”

Sergei narrowed his eyes. He knew there was nothing he could say or do that would have any influence on Secor with the possible exception of making them angry, but he didn’t want to just leave it at that. Despite the current tension between them, his loyalty was still to her.

“I’ll be fine, Sergei. I’ll just answer the captain’s questions and then we can get on with cashing in the scrips and finding some more work, OK?”

With every sign of not finding it OK in the least, Sergei nodded. “Take care, Katya,” he said as he reluctantly took his leave. “I’ll see you back at the boat, yes?”

“I’ll see you there. Bye for now, Sergei.”

He walked back towards the docks slowly, looking over his shoulder now and then.

“He’s very protective of you,” said the captain.

“Yes,” agreed Katya, turning away from Sergei to face her. “He’s a family friend.”

“How nice, considering you don’t have any family left.”

Katya blanched. “You’re such a bastard, Tasya Morevna. Hard to believe you ever had a family. What did you do, eat them?”

The “Secor captain” smiled slightly. She’d been called much worse in her life, and accused of much worse. Sometimes the charges had even been true. “Lovely to see you again too, Kuriakova,” she said. “I was wondering if you’d recognised me. I’ve even dyed my hair.”

“How about I shout the place down, Chertovka?” demanded Katya, exhaustion making her reckless. “How about I point at you and denounce you as a war criminal and a traitor? You won’t get out of here alive.”

Tasya Morevna, unkindly nicknamed the “Chertovka” or “She-Devil,” seemed supremely unimpressed by the threat, even if the two “troopers” with her looked a little worried. “No,” she admitted, “we probably wouldn’t. Of course, neither would you. And then we’d all be dead, and you wouldn’t have found out why we’d gone to all this trouble to speak to you.” She smiled icily. “You’d die curious, and I know how much that would irritate you. Walk with me, Kuriakova. We’re attracting attention standing here.”

Grim and angry, Katya allowed herself to be cajoled into walking alongside Tasya, the two “troopers,” whom were certainly Yagizban agents in reality, following up the rear, their maser carbines carried at a “full port” position across their bodies. People avoided looking at the little group; Katya’s surly expression, Tasya’s smirk, and the two troopers were the popular image of a typical Secor arrest in progress, whether the detainee was guilty or not. Nobody wanted to stare, because that might mean sharing their fate. Even before the conflict against the Yagizba Enclaves had begun, Secor had enjoyed an unsavoury reputation. Now that people’s fear of spies and saboteurs — a fear the FMA was happy to encourage — was running wild, Secor did almost anything they liked, as long as it was not considered too overt or damaging to public morale by the ruling council. Impromptu public executions, such as had occurred in the first month of the conflict, had been stamped out. Most Federal citizens assumed they had simply been replaced with impromptu private executions. In this, they were correct.

The advantage of the almost supernatural levels of fear that accompanied Secor agents was that it meant anyone dressed as one was essentially invisible. It was an easy bet that not one of the dozens of people that passed them by would have been able to provide anything but the vaguest of descriptions for anyone in the party.

Tasya led the group to a restricted door into a disused maintenance area, the card she swiped through the lock looking suspiciously like an authentic Secor pass to Katya. She had assumed up to this point that the uniforms had been stolen from a storeroom somewhere, but now she was beginning to have misgivings. Where the Chertovka was involved, it was all too easy to imagine a storeroom with the corpses of a Secor officer and two troopers somewhere, stripped of their uniforms.

The door clanged to and locked behind them, cutting them off from the busy thoroughfare and leaving them in a suddenly very quiet, dank, barely lit access corridor to some part of Atlantis’ infrastructure that it probably didn’t even use anymore. “There,” said Tasya with satisfaction. “This is much cosier, isn’t it?”

Without waiting for the obvious reply, she moved ahead and Katya — for lack of other options — followed her. The corridor really was an archaeological site, in Russalkin terms at any rate, probably dating back to the foundation of Atlantis over a century before. At some point it had become surplus to requirements and was now just home to a few leaky pipes and some corroded power and control cabling, none of which had carried so much as a joule of energy since before she was born. Tasya clearly knew her way through the narrow corridors of what turned out to be a labyrinthine route. Behind them, the Yagizban “troopers,” pleased at no longer having to playact soldiers, slung their carbines over their backs by their straps and held a brief muttered conversation about being glad to be off the thoroughfare as they followed Tasya and Katya.

Katya was both irritated at all the clandestine sneaking around, and slightly smug because she was memorising the route. She might not have many talents, she thought, but trying to trip her up on a matter of navigation was just stupid. She knew they had already re-crossed their path twice, so she was positive Tasya was trying to disorientate her. Well, if crossing the Vexations with an unreliable inertial compass hadn’t caused her any great problems, then wandering around a few corridors — each of which was littered with plenty of distinctive features to remember — was insultingly easy. She didn’t tell Tasya that, of course; let her think she’d succeeded in baffling poor little Katya.

Then, finally, Tasya reached a door, opened it and waved Katya inside. Katya went with poor grace; she was reasonably sure that if they were going to murder her, they’d had plenty of opportunities up to now and passed on all of them. Thus, she felt fairly safe in giving Tasya the evil eye as she passed her. Then she looked into the room and any thought of such one-upmanship left her.

The poorly lit, dirty little room must have been some sort of supervisor’s office once, a long, long time ago. Charts and schematics still hung from the walls, discoloured and watermarked. There was an old desk, a steel thing that had probably been manufactured on Earth, and an old holoconsole of a type that Russalka was currently incapable of making because the technology behind it was of limited use and not vital to survival.

Sitting behind the desk was the most wanted man on the planet.

“Hello, Katya,” said Havilland Kane.

CHAPTER FOUR

Total War

Katya was literally lost for words for several long seconds. This didn’t make any sense. Tasya had worked with Kane when Kane — the “great pirate” and “terror of the world ocean” — had been working for the Yagizban. But then Kane had betrayed the Yagizban, and Tasya — a colonel of the Yagizban military, for crying out loud — had stopped being his friend very abruptly. Indeed, there had been some name-calling.

And shooting. There had definitely been shooting.

Yet here they were, the pirate-king and the war criminal, all cosy together. Unless…

Turning to Tasya, she said, “Is Kane your prisoner?”

Tasya looked nonplussed, then she followed Katya’s logic and laughed. “No. Havilland is not my prisoner, nor am I his. We’re working together again.”

“Just like that? I don’t believe it.” She turned to Kane. “The Yags would never work with you. Not after what you pulled on them.”

“Yags, Katya?” He seemed pained. “Yags? Really? You sound like one of those FMA scream sheets.”

Katya had had enough of this already. She’d had enough of it the very second she saw Kane’s face. “Take me back,” she said to Tasya. “I’ve got nothing to say to you, and I’ve got even less to say to him.” She indicated Kane with a perfunctory jerk of her head. “Take me back right now and let me get on with my life without having lunatics like you and scum like Kane in it.”

Tasya raised an eyebrow. “Her diplomatic skills have simply come on in leaps and bounds, haven’t they, Havilland?”

“Katya,” said Kane sharply, “stop behaving like a little brat and listen to me. Do you think we took a risk like coming to Atlantis unless there was a very good reason?”

“Of course there’s a good reason,” said Katya, “but it’s a good reason that profits you and the Yags. I’m not helping either of you. That’s all there is to it. And if you’re not going to take me out of here,” she said to Tasya, “I’ll find my own way.”

Kane grunted with displeasure. He still looked much as she remembered him; in his late thirties, lean, an aesthete in appearance. He always looked as if he should be lecturing in philosophy or literature, not leading a crew of stranded Terrans as his pirate crew around the deep waters of Russalka. He looked a little older now, though. There was grey at his temples that certainly had not been there before. She doubted that was because of the stress of being Federal Enemy No.1; he’d been that for years now and it didn’t seem to bother him very much. There was another, darker possibility — that his long-term dependence on the drug “Sin” was finally taking its toll. Sin was no pleasure; it was a method of enslavement. If Kane didn’t receive regular doses of it, he would slowly die in agony. Even though he had the formula and a steady supply of the stuff, it was hard to believe that having something so terrible in his system could do anything but harm eventually.

“The Yagizban wanted to win,” Kane said. “Me, I just want to stay alive and to keep my people alive.”

“Whoopee for you, Kane. You and every family in this…” She stopped as she fully analysed what he had said. “What do you mean, the Yagizban wanted to win? I was an unwilling spectator to a shooting match with one of those Vodyanoi copies on our way here. I think its crew were still trying to win. All the torpedoes swimming around, they were a strong hint.”

“No,” said Tasya, leaning against the doorjamb. “What you saw was the prosecution of a war. That’s not the same as trying to win it. That’s just not lying down and giving up.”

Katya was having problems with the conversation that extended beyond its location and the other speakers. They were talking as if the Yagizban were at least thinking of giving up. It certainly didn’t sound as if they had much belly for the fight. Kane was ahead of her.

“Don’t think the Yagizba Enclaves are thinking of surrendering. Because they’re not.”

“We can’t,” added Tasya with quiet emphasis.

Katya was still near the door with a strong impulse to leave, but she wasn’t leaving. She would in a moment, she was sure. Any minute now, she’d be gone. Any moment.

Just as soon as she’d found out what the hell they were talking about.

“What does that mean, ‘we can’t’?” she said. “It’s very easy. You say to the Feds, ‘We surrender.’ There’s no big trick to it.”

Kane shook his head. “This war is more complicated than you realise, Katya.”

He reached inside the long coat he always insisted on wearing, even in the temperature and humidity controlled submarine environments, the freak. Mind you, he liked the surface, liked standing around on surfaced submarine decks and on the Yagizban floating platforms, even in the howling cold and rain. She’d seen him do it herself, and it still mystified her even if it explained his attachment to his coat.

She decided she needed a stronger word than “freak” to really sum Kane up. Then she remembered that he was Terran by birth; he was already the most extreme form of freak imaginable.

Meanwhile, the freak in question had found what he was looking for. He pulled a waterproof envelope from his inside pocket, unsealed it and produced several sheets of hard copy. “These documents are all top secret,” he said offhandedly, as if everybody carried secret papers around with them. “The Yagizba Enclaves have already made diplomatic overtures towards equitable terms for a cessation of hostilities.” He looked at Katya. “That means they’re trying to end the war, by the way.”

“I know what it means,” said Katya, although she hadn’t been completely sure.

Unabashed, Kane held up one of the sheets. “This is what they suggested. Immediate ceasefire, normalisation of relations, independence for the Enclaves from Federal authority, and a claim of about an eighth of the planet’s surface.”

“An eighth?” Katya was astounded and disgusted. That sounded like a lot.

“Yes, an eighth. Bear in mind that the Yagizban represent about a quarter of the planet’s human population. An eighth is actually pretty modest. The eighth they want contains no Federal facilities, stations, developed mining sites, or anything else that would need to change hands. It’s untouched apart from what the Yagizban already have there.”

“What has this got to do with me?”

“As a Federal citizen, it has everything to do with you. Did you know the Yagizban had tried to negotiate? No. Their terms sound better than a war, don’t they?”

Katya said nothing. She could see the other sheets Kane had taken from the envelope and scattered on the desk. One of them had the FMA seal in the corner. Kane picked it up.

“This is the Federal response to that olive branch.” He saw her frown and added, “Sorry, that’s an Earth term that apparently didn’t make the trip here. It just means a peaceful overture. Here, read it yourself.” He passed her the FMA document.