In the fragile peace following Queen Death’s defeat, Dr. Daniel Jackson arrives in Atlantis to indulge in some real archaeology. Naturally, things don’t go according to plan.

Convinced that an Ascended Elizabeth Weir saved his life, Dr. Rodney McKay argues that she must have escaped her replicator body in order to ascend. No one believes him, but when rumors reach Atlantis of a woman with no memory who calls herself ‘Elizabeth’, Rodney is determined to track her down.

Meanwhile, Daniel’s research uncovers evidence of Vanir activity in the Pegasus galaxy — evidence that casts both light and shadow over the mystery of Elizabeth…

http://interworldbookforge.blogspot.ru/. Follow for new books.

http://politvopros.blogspot.ru/ — PQA: Political question and answer. The blog about russian and the world politics.

http://auristian.livejournal.com/ — Interworld's political blog in LJ.

https://vk.com/bookforge — community of Bookforge in VK.

https://www.facebook.com/pages/Кузница-книг-InterWorldа/816942508355261?ref=aymt_homepage_panel — Bookforge's community in Facebook.

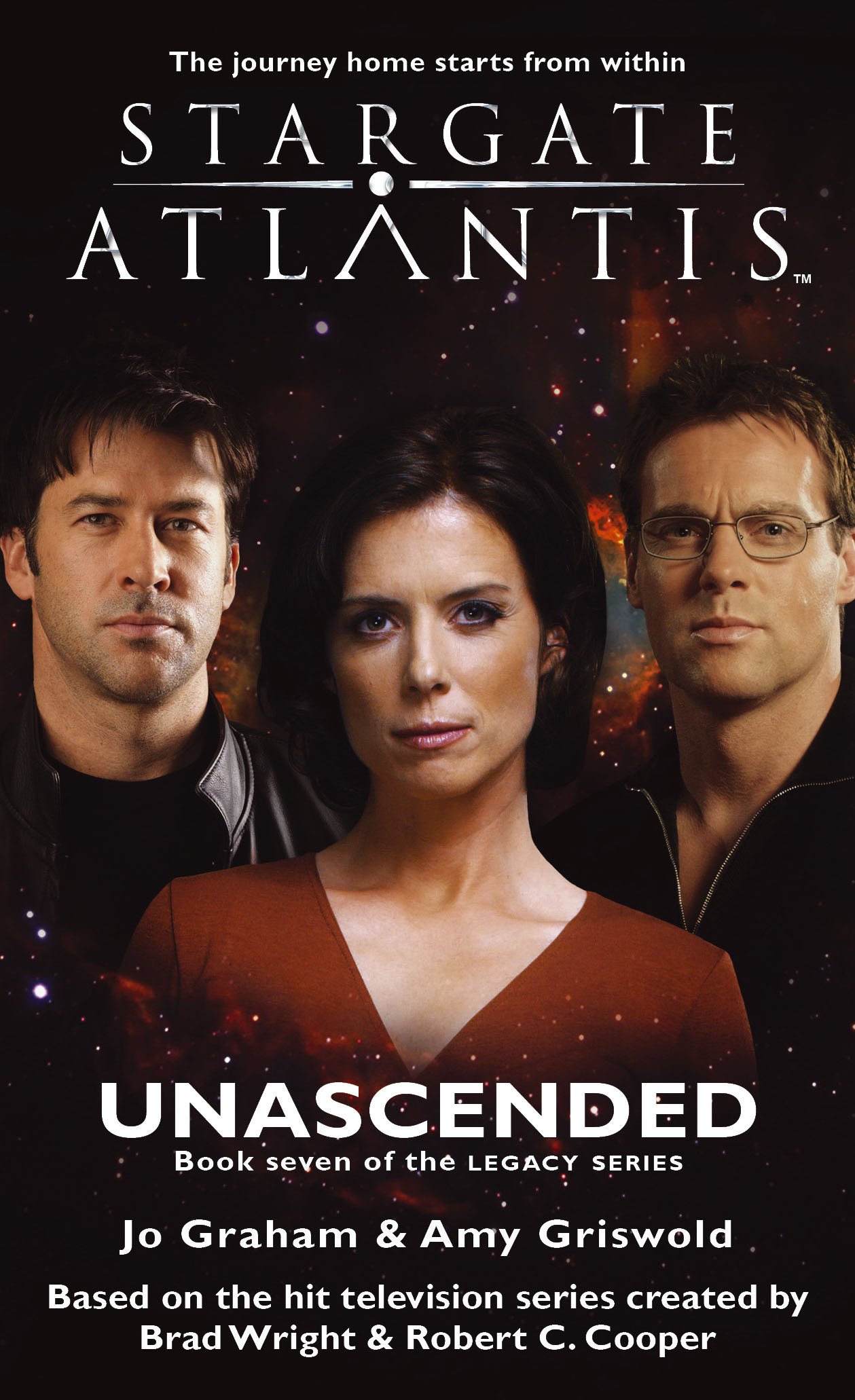

Jo Graham, Amy Griswold

StarGate: Atlantis

Legacy

Unascended

Prologue

There was nothing. It might have been a few hours. It might have been years. She had no sense of time, no sense of self.

Nothing.

Floating in near-absolute zero space, trapped in a non-functioning replicator body, days might have passed. Or eons. There was nothing.

“Elizabeth.”

There was a voice, and in some dim part of her she knew that. She knew something. There was a voice, and it said her name.

There was no way she could answer. Frozen synapses and circuits could never respond. She could not even think an answer, not in any conventional way. She knew it was not possible.

She knew. Which should not be possible either. Thought should not be possible. Consciousness should not be possible. She should not hear a voice, or even dream that she heard one.

And at that the part of her that was still Elizabeth Weir leaped, a frail flame trembling in determination. “Who are you?”

There was a net, a golden net that twined around her. For a moment she saw it complete, gold strands formed into knots, each one different, each one tied by hand, “You are safe,” the voice said. It sounded like her mother, like a woman’s voice, but that couldn’t be.

“I am dead,” Elizabeth said.

“Not quite,” the voice said. “You cannot die and you cannot live, frozen in a replicator’s body.”

“Who are you?” she asked, and it felt like her voice strengthened with each word, that her mind strengthened with each thought, herself coming back to her as though her whole being was gathered in by the golden net.

“Ran,” she said, and Elizabeth saw her, a woman two thirds her height with long, raven black hair and pale skin mottled with all the colors of the sea. She could almost have been human except for her eyes, black and wide with no iris or pupil at all, simply dark lenses.

“This is not possible,” she said, for it seemed to her that the woman stood in front of her, and that Elizabeth had a body again, like her own had been when she died, with all its flaws and strengths. It was not possible for her even to imagine this.

The circuits necessary to produce such a delusion should be frozen inactive.

“It is,” Ran said, her voice timbreless. “Are you ready to leave?”

Elizabeth raised her chin. “To die?” Death would be a mercy, compared to eternal nothing. It would be an ending, or perhaps a beginning depending on whose beliefs about the universe were true.

“To live,” the woman said, almost tenderly. There was something vaguely familiar about her, about her long four fingered hands that drew the net in gently.

“Do I know you?” she asked.

“Your people worshipped me once,” the woman said, drawing in the net from infinite space, each strand glittering in her hands. “She who takes the souls of sailors lost at sea. Ran, the Queen of the Deeps. Are you ready to leave?”

“I can’t,” Elizabeth said. “If you thaw me, you will reactivate the nanites. We can’t afford that. Humanity can’t afford that.”

“I meant without your body,” Ran said gently. “There is one way out, Elizabeth. A way that has always been open to you.”

“Ascension.” She looked at her, feeling her brows furrow, and surely that was impossible. Surely she had no face, no body, though she felt it around her, felt her face change expressions. “Are you an Ancient?”

Ran did not smile, though her voice seemed amused. Perhaps those lips were never meant for smiling. “Do you think the Ancients are the only ones who ever learned to Ascend?”

“You’re not human…” There were pieces of a puzzle here, if she could put it together.

“Nor any other child of the Ancients,” Ran said. She held out one long, four fingered hand, and her voice was like the murmur of the sea. “Come, Elizabeth.”

She took a deep breath. “What do I need to do?”

“Take my hands,” she said. “And let go.”

And then there was something.

Chapter One

Rodney McKay frowned down at his coffee, which had grown ice cold since the beginning of an interminable meeting with Radek Zelenka to plan the science department’s schedule. He drank it anyway. There were only a few more hours of lab time left to fill with maintenance and other people’s questionably necessary research, and then at least he could get more coffee.

“So we are on systems maintenance for Friday afternoon,” Radek prompted.

“Friday, right. We can finish testing the power conduits for damage that might have resulted from flying the city, although given that it’s been weeks, any actual significant damage would already have shown itself in the city’s power consumption by now, so ultimately that’s one more pointless exercise.”

Radek pushed his glasses up his nose in obvious frustration. “Tell me, Rodney, is there anything on this week’s schedule that you are in favor of our doing? You are the one setting the schedule, so to complain about it at the same time seems more than a little perverse. What do you want us to do?”

“I think we ought to look for Elizabeth.”

He hadn’t known that was what he wanted to do until he said it, but the words crystallized the sense he’d been having these last few weeks that they were wasting time, letting it pour through their fingers in some way that he hadn’t been able to articulate but that he was sure that they’d regret.

There was a lengthy silence before Radek replied, and when he did he seemed to be choosing his words very carefully. “Rodney, Elizabeth Weir is dead.”

“I remember what happened to Elizabeth. I’m not an amnesiac. Or crazy.”

“Anymore.”

“I don’t have amnesia anymore, and according to Carson, physically I’m in perfect health and almost 100 percent human again—”

“You still have the white hair.”

“I’ve been thinking of dying it, actually, I’ve been considering Grecian Formula for Men — and you know what, never mind the hair, that’s not the point. My point is, I am feeling much better. And I was never crazy, I was brainwashed and medically transformed into a Wraith.”

“You nearly killed me.”

“Yes, but I didn’t.”

“You let the Wraith into Atlantis.”

“Yes, and I’m sure that it will really help me to deal with my traumatic guilt about the things that I did while I had amnesia for everyone to keep constantly reminding me.”

“All I am saying is that you have been through a great deal.”

“I know what I saw,” Rodney said doggedly. “When I was in that puddle-jumper headed into the sun, out of reach of anybody’s transport beams, Elizabeth saved me. She appeared in the jumper and transported me aboard the Hammond. The only way she could have done that was if she weren’t dead, but Ascended. And what do we know is the one rule for Ascended beings?” He didn’t wait for an answer. “They’re not supposed to interfere in the affairs of unascended beings. Or they get kicked out of the higher plane. That’s what happened to Dr. Jackson when he was Ascended.”

“You think she is out there somewhere, having, what … unascended?” Radek shook his head slowly. “Rodney, we all understand that you have been having a difficult time—”

“Fine.” Rodney slammed down his coffee cup with a thud. “I’m going to go get Woolsey to authorize the gate team to do something about the problem. Since you’re not on the gate team anymore, you can finish the maintenance schedule. You don’t need me for that.”

“Yes, because scheduling is not entertaining and therefore does not require your genius,” Radek said. He sounded relieved that they were back to bickering about the schedule.

“I’m going to see Woolsey,” Rodney said, and stalked out.

Woolsey steepled his fingers. “Dr. McKay. As much as I would like to believe that Dr. Weir somehow survived being frozen in the vacuum of space—”

“In the body of a Replicator,” Rodney said. “So being frozen in space wouldn’t actually have killed her, just rendered her completely incapable of any kind of movement or thought.”

“Which raises the question of how she could possibly have Ascended while in that state.”

“Maybe it doesn’t require conscious thought. Maybe it’s more of a Zen thing. And, all right, as far as we know it requires certain brainwaves that a frozen Replicator body probably doesn’t have, but maybe something happened to unfreeze her, or maybe there’s a way around that, I don’t know. I suggest we find her and ask her.”

“Even granting the possibility,” Woolsey said slowly, “do you have any evidence whatsoever to support the idea that this is what actually happened?”

“Someone transported me off that puddle-jumper,” Rodney said. “The Hammond was out of range, and Sam says that they couldn’t and didn’t transport me aboard.”

“Consider the possibility that the Hammond’s transport logs could be in error. The ship was actively engaged in battle and had taken considerable damage at that point.”

“They were still out of range.”

“Even so, isn’t it possible that the transport beam might have worked at an abnormal range as a result of the sun’s radiation, or some other unusual circumstance—”

“No,” Rodney said flatly. “That’s not how it works. Ask Carter. She’ll tell you that there’s no way that radiation interference could radically alter the capabilities of the Asgard transport beams that way, let alone do it at the perfect moment to save my life.” He hesitated, and then added, “And she believes me about Elizabeth.”

“I could ask Colonel Carter, if she weren’t on her way back to the Milky Way galaxy with the Hammond.”

“So ask her when she gets there. And in the mean time, we need a plan for how we’re going to get out there and …” He trailed off at Woolsey’s expression.

“Dr. McKay,” Woolsey said. “I’m absolutely certain that you understand that I can’t take Colonel Sheppard and his team off their current list of priorities in order to conduct a search for someone we don’t know is actually missing.”

“So find out. Let us dial the space gate where we sent Elizabeth and the other Replicators and see if she’s still there. If she is, then … then we know that, and if she isn’t, then she has to have gone somewhere.”

“All right,” Woolsey said after a moment. “I’ll send Major Lorne’s team to search the area around the gate.”

“Even accounting for drift, it’s a reasonable area to search. If they’re there, Lorne should be able to find them. And if they’re not, if she’s not—”

“With all due respect, Dr. McKay, suppose we cross that bridge when we come to it.” Woolsey considered him from across the desk. “I understand that you feel ready to return to your usual duties, but considering what you’ve been through—”

“I am fine,” Rodney snapped. “Let me know when Lorne doesn’t find her.”

“I will let you know as soon as I hear anything,” Woolsey said, which was unfortunately hard to argue with.

“You do that,” Rodney said. “I’m going to go ask Sheppard what he thinks.”

“I think you’ve been under a lot of pressure lately,” John said. He was leaning on the balcony looking out over the slate blue sea, the chilly wind whipping the swells into whitecaps and sending them breaking against the pier. Their current planet was colder than either of the previous two, and although it wasn’t actually snowing at the moment, the weather still felt wintry.

“Will you stop saying that? I am not crazy.”

“I didn’t say you were,” John said. “I’ve been in the ‘hallucinating dead people’ place myself, so I haven’t exactly got room to judge. You just need some time to get over this.”

“What connection do you see between having been turned into a Wraith and seeing Elizabeth appear out of thin air to save my life?”

“I think you might have been under just a little bit of stress,” John said. “Remember the time when you were trapped in a submerged puddle-jumper and you hallucinated Carter in a bathing suit?”

“The life support systems were failing. I was hypoxic.”

“And that’s nothing like how you were hypoxic when you appeared in the Hammond’s medical bay, right?”

“It was Elizabeth,” Rodney said. “She was real. We have to go find her.”

“Look,” John said, his tone growing grim. “No one wanted to save Elizabeth more than I did. If there were any way to get her back, we would have already done it. We don’t leave our people behind.”

“I know that.”

“So you ought to know we did everything we could. You can’t let some kind of hallucination—”

“It was not a hallucination. I dreamed about her, when I still thought I was a Wraith. I wasn’t hypoxic then.”

“And dreaming about dead people is a sure sign that they’re alive, right? Listen to yourself, McKay.”

“Something transported me aboard the Hammond. And don’t say it was the Hammond’s transport beams having some strange malfunction unless you know more about Asgard engineering than me and Sam put together.”

“No one is putting you and Carter together.”

“Yes, very funny. My point stands.”

“Maybe you figured something out. That’s what you do. You come up with these last-ditch solutions to save our asses when things go wrong. So, you came up with some way to transport yourself off the jumper, but then because you were hypoxic, you didn’t remember what you’d done.”

“I would remember if I’d broken about ten laws of physics.”

“If you say so, McKay.”

“You don’t believe me,” Rodney said.

John turned to look at him, no humor at all now in his eyes. “Elizabeth’s gone,” he said. “I don’t know if you blame yourself—”

“Of course I blame myself, I’m the one who reprogrammed the DHD to transport her into space.”

“Which she knew. It was the only way.”

“I know that.”

“I know you know that. And I know that you feel bad about some of the things you did when you were a Wraith, which I don’t blame you for, because you had amnesia. But maybe that’s, I don’t know, bringing up some feelings—”

“Are you trying to psychoanalyze me? Don’t make me laugh. You are the last person on the planet who is qualified for that.”

“Pretty much,” John agreed, sounding a little relieved. “You know, maybe you should talk to Teyla. She’s better at dealing with …”

“Crazy people who hallucinate dead friends rescuing them?”

“That kind of thing,” John said.

Rodney ran into Ronon first, clearly on his way back from the gym, with a towel thrown over his shoulder and a stick in hand. He looked cheerful, like he’d been beating up Marines.

“Have you seen Teyla?”

“She went to take Torren to New Athos. He was going to spend the weekend with Kanaan. She should be back by now, though.” Ronon looked at him cautiously. “You’re not having more Wraith problems, are you?”

And that was still a bit of a sore subject; Ronon had come pretty close to killing Rodney with a weapon that would have destroyed everyone with Wraith genetics, and Rodney had come pretty close to feeding on Ronon while he was still physically a Wraith. As far as he could tell, they were dealing with both of those using the traditional Atlantis method known as “let us never speak of this again.”

“All better now,” he said, with what he hoped was a reassuring smile. “Except for the hair, which is a problem I can deal with.”

“You could dye it.”

“I’m thinking about that.” Ronon was headed in the same direction as Teyla’s quarters, so Rodney hurried his own steps to keep up with him. “I think Elizabeth was the one who saved me from the puddle-jumper,” he said, because Ronon already thought he was strange, and at least he wasn’t likely to try amateur psychotherapy. “I think she Ascended.”

“Could be,” Ronon said.

Rodney stopped, and then had to trot to keep up with him. “You don’t think I’m crazy?”

Ronon shrugged. “Stranger things have happened.”

“So you think she could be out there somewhere?”

“I don’t know. I’m not really the person to ask.”

“Yes, I know Dr. Jackson is still here, but the two of us haven’t exactly worked smoothly together in the past, and I’m not sure I really need his help with this.”

“I was thinking more like some kind of priest. Your people have those, right? Or maybe you should talk to Teyla. She knows more about that spiritual stuff. She meditates, and everything.”

“I was actually looking for Teyla.”

“Good plan,” Ronon said.

Teyla poured him a cup of tea. Rodney would have preferred coffee, but it didn’t seem like the moment to insist.

“I dreamed about Elizabeth,” he said. “When I was a Wraith, when I couldn’t even remember that I was human, let alone remember my own name, she helped me. And then she appeared in the puddle-jumper. That wasn’t a hallucination. It was the real Elizabeth, and she had Ascended.” He spread his hands defensively. “All right, let’s get the part where you tell me I’m crazy out of the way.”

“Why would I say that?”

“Everyone else thinks so. Except maybe Ronon, but who knows what he really thinks.”

“I have dreamed of Elizabeth too,” Teyla said seriously.

“You have?”

Teyla nodded. “I dreamed that she spoke to me and showed me things that helped me. I believe that she has become a guardian for her people here in Atlantis, that she watches over us as one of the Ancestors and protects us. Perhaps she Ascended, or perhaps that is part of what happens beyond death. But I believe that she helped you.”

“All right, good, someone believes me. Now all we have to do is figure out how to find her,” Rodney said.

Teyla put her head to one side. “Find her?”

“Ascended beings aren’t supposed to interfere. She even told me that she knew she’d get in trouble for it. If they’ve sent her back as a human, she’s out there somewhere. She wouldn’t know Atlantis’s current gate address even if she was trying to come home. I’ve asked Woolsey to authorize a search, but he’s dragging his feet about it.”

Teyla poured herself another cup of tea before she answered. “I believe Elizabeth is trying to tell you something, but you may need to look deeper to understand her message.”

“What do you mean?”

“If you feel the need to look for Elizabeth, perhaps you should try looking within. If you meditate, and open yourself to hearing the voices of your ancestors and guardians, you may find her there.”

“I am not talking about a spiritual experience,” Rodney said. “I’m talking about contact with someone on another plane of existence.” Teyla looked at him as if that didn’t make perfect sense. “She was there,” Rodney said. “Not as a voice or a guardian spirit or anything mystical. She was right there in the jumper with me, just like we’re sitting here right now, and she saved my life.”

“I am sure that you saw her there,” Teyla said patiently. “And I believe she did save your life, by helping you find a way to save yourself.”

“I didn’t transport myself off the jumper,” Rodney said. “There is no possible way I could have done that.”

“You have said yourself that the Ancestors knew far more about their technology than we do,” Teyla said. “Elizabeth may have learned things about it that we still have not discovered.”

“There is nothing you can do with a puddle-jumper’s systems that we haven’t figured out by now. And if there is, the Hammond would have detected the transport. I wouldn’t have just appeared.”

“There is another possibility,” Teyla said. “You came very close to Ascending yourself once.”

“Only because an Ancient device had given me superpowers and I thought was going to die if I didn’t,” Rodney said.

Teyla nodded encouragingly. “Is it not possible that under great duress, you rediscovered within yourself some of the same abilities—”

“So why this time, and not during any of the other terrifying near-death experiences I have on an all-too-regular basis?”

“Perhaps because this time Elizabeth was there to guide you.”

“If you believe that, why don’t you believe she’s out there for us to find?”

“I believe that people we loved may watch over us and guide us,” Teyla said. “But the dead are still dead. They do not simply … come back.”

“Daniel Jackson did.”

“Then perhaps you should ask him what he experienced.”

“I was afraid you’d say that,” Rodney said.

Daniel cleared a chair of books, which made it possible for Rodney to actually sit down. “Sorry about the mess,” he said. He waved a hand at his tablet, which was lying on the coffee table still scrolling lines of Ancient text. “I’m reading up on everything we know about early Ancient settlement in the Pegasus Galaxy. I appreciate your team helping me investigate some of the settlement sites.”

“Woolsey ordered us to,” Rodney said.

Daniel’s voice grew dryer. “Yes, I knew that, but I thought we were being polite.”

“Let me start over,” Rodney said. “What do you know about Ascension?”

Daniel leaned back in his chair and considered him. “More than most people. Why do you ask?”

“I think Dr. Weir may have Ascended,” Rodney said. “When I was a Wraith, she appeared to me and spoke to me. And then when I was going to die, she appeared and saved my life. But she seemed to think she was going to be in big trouble for that. Like the kind of trouble where you get kicked out of a higher plane of existence.”

“It’s possible,” Daniel said. “I’m told that while I was Ascended — the first time — I appeared to some of my friends when they were in bad situations. And then when I tried to interfere more directly, I got kicked out. But I don’t remember much about what that was actually like.”

“You just appeared somewhere, right?”

“Yes, and that’s something that you could ask your allies if they’ve heard anything about. Naked amnesiacs don’t show up in the middle of somebody’s field every day.”

“How serious amnesia are we talking about?”

“I had no idea who I was or where I came from,” Daniel said. “I could talk, and I remembered some skills, but most of it was just … flashes, images. Nothing that made sense. Even after SG-1 found me, it took some time for everything to come back. Of course, it may not have helped that I wasn’t entirely sure I wanted everything to come back. In some ways it was restful having a break from remembering everything that had ever happened to me.”

“She may not even remember that she’s looking for Atlantis. We’ve got to find her.”

“All right. How?”

“I was hoping you’d have some ideas about that,” Rodney said, as humbly as possible.

Daniel drummed his fingers on the table for a minute. “When Oma sent me back, I think she wasn’t supposed to send me home. I was supposed to start a new life that didn’t involve causing any more trouble. But she put me somewhere that SG-1 was going to come sooner or later, because it was a possible site of Atlantis, which we were still looking for at the time.”

“She cheated?”

“Never play poker with Oma Desala. Now, we don’t know what Dr. Weir’s situation is. We don’t even know for certain that she was forced to unascend. But it’s possible that she, or whoever returned her to human form, wanted her to be found.”

“Meaning what?”

“Meaning that your best chance of finding her is probably to continue doing whatever you were planning to do, and to keep your eyes open. I’m assuming that if she’d appeared on New Athos, you’d have heard about it by now.”

“They all knew Elizabeth.”

Daniel nodded. “I only met her briefly, but she was a remarkable person. I’d like to think you’re right.”

“As long as you don’t think I’m crazy.”

“Why does it bother you that people might think you’re crazy? I mean, I’m pretty much used to it. Pyramids built by aliens, it was never a popular theory.”

“That’s you,” Rodney said. “I’ve always—” He was interrupted by his headset radio.

“Dr. McKay, this is Woolsey. Major Lorne has just reported back.”

“And?”

“I’m very sorry, Dr. McKay. Dr. Weir’s Replicator body was located along with the other Replicators. It appears to still be entirely inert.”

“Dead. You mean dead.”

“I am sorry.”

“Yes, well, so am I,” Rodney muttered, and he switched off his headset.

“Bad news?” Daniel said.

“They found Elizabeth,” Rodney said. “Still floating frozen in space. So there goes that theory, right? Chalk the whole thing up to an incipient and well-deserved psychotic break.”

“I don’t know,” Daniel said slowly. “I don’t want to give you too much hope—”

“You know what, excessive optimism has never really been a problem of mine.”

“Okay, then. The body that’s floating in space isn’t Elizabeth’s original body. Her consciousness had already been separated from that body, in a state that allowed it to exist in subspace, and then to inhabit a new Replicator body. Yes?”

“As far as we understand, yes.”

“So, it’s possible that the part of her that makes her Elizabeth could have Ascended, and not taken the Replicator body with her. I think the physical body goes with you in the first place because you’re used to thinking of it as part of yourself. But this was a new body for Elizabeth. She may not have identified herself with the body that way.”

“And there’s no way of knowing if Elizabeth is still in there, because we can’t risk thawing her out and asking her,” Rodney said.

“I don’t expect Woolsey’s going to authorize that,” Daniel said. “Not to mention that if she is in there, it would be pretty cruel to put her through being woken up when you still don’t have a solution for her problem.”

“Believe me, we’ve tried to come up with something,” Rodney said. “But if she didn’t Ascend, there’s nothing we can do that will make it safe to unfreeze her. She’s essentially dead, and she’s going to stay that way.”

“So let’s keep our eyes open,” Daniel said. “And keep doing what we’d be doing if we weren’t looking for Elizabeth, and hope she finds us.”

“That’s fair enough,” Rodney said. “Of course, that means that we’re going to be doing exactly what you wanted us to do in the first place.”

“As you pointed out, that’s what Woolsey already ordered you to do.”

“Great. Let’s go look for Ancient installations.”

“I’m looking forward to it,” Daniel said.

Interlude

She lay in the tall grass, feeling it itch along her skin, and opened her eyes. Shadow. She lay face down, her head pillowed on her arm, and turned her head. She lay in a field of flowers. Golden stars surrounded her, deep in the tall grass, while above the largest stalks great pink flowers raised their heads to the sun, their centers black with seeds. They were no flowers she knew, nothing she had a name for. The sun was warm on her back and she lay in a field of flowers.

The sun was warm. Where had she been that it was so cold? Why couldn’t she remember? Perhaps it didn’t matter much.

There were the sounds of voices, children’s voices raised in song, the deeper voices of adults. They sounded happy. That was good. It was good for people to be happy on such a lovely day.

There were the sounds of running feet, and then they stopped. A child’s voice sang out very close at hand. “Gran! Gran, come quick! There’s a naked lady here!”

More footsteps. A woman’s voice. “Kyan, get back. Go to your father.”

A hand touched her neck from behind, careful fingers gentle as they felt her throat. Checking for a pulse. She knew that gesture, and she opened her hand against the earth.

“Ah.” A woman’s voice, then a man further away.

“Kyan, come here.”

“She’s alive,” the woman said.

She wanted to answer, but the words stuck in her throat.

Careful hands lifted her, turning her over, the sun unbearably bright on her face. “Can you hear me?” the woman asked.

A shadow, the man bending over. ‘I don’t see any blood. Is she hurt?”

Something settled around her shoulders, a cape of soft feathers. She opened her eyes.

An old woman bent over her, concerned brown eyes peering at her face. “Can you speak?”

“I…think so.” Her voice was hoarse, as if from disuse.

The cape settled around her, bright green feathers smelling like sunshine and some deeper scent of resin, covering her nearly to the knees.

The man held a little boy by the hand, the boy watching her curiously. Behind were other people and a three wheeled cart pulled by a pair of large dogs. The men’s heads were shaved except for the child, each carrying packs or bundles. “Where did you come from?” the man asked.

“Child, can you stand?” the old woman asked.

She took the offered hand, getting slowly to her feet. All around them stretched a plain of wild grass, a prairie filled with wildflowers. “Where am I?”

“Along the route to Iaxila,” the man said. “Were you lost from a caravan?” He looked at the old woman worriedly. “There haven’t been bandits on this route for a long time, but…”

The old woman held her hand gently. “You’ve fallen in among honest people. We won’t hurt you, I promise. The Ancestors charge us to treat the stranger as our own. What terrible thing happened to you?”

She stood in the bright sun, her hand in the old woman’s, looking across the grass from horizon to horizon, and no words came. No thoughts. They ran away like water, any moment before this. “I don’t remember,” she said.

They camped that night on the open plains, their fire small compared to the fires above. The sky was thick with stars, a wash of them across the eastern sky illuminating almost to twilight. There was a stew of grains and dried meat, some folded dried fruits passed hand to hand. She sat in the clearing where the tall grass had been cut for the fire, her hands around the hollowed gourd that held her stew.

They had found clothes for her, baggy trousers that tied at waist and ankles, a tight fitting top of knitted wool dyed in all the green shades of new growth, as though one skein had been dipped from dark to light and back again. She was warm enough. Everyone was very kind and very careful.

She slept beneath the stars, wrapped in a tanned hide with fur on one side, listening to the quiet sounds of the camp. Waking changed to sleeping and sleeping to dreaming so gradually that it seemed she was still awake.

She lay beside the dying fires, the tents lit from within by their battery powered lights while the adults talked quietly. The radio with its makeshift antenna played, a song about a girl with kaleidoscope eyes. Her parents were talking, nursing cups of strong British tea, while outside the circle of the fires she saw the reflected gleam of green eyes. They watched steadily.

She got to her feet. The green eyes were unblinking. She started toward them, away from the fires.

An arm around her waist, picking her up and carrying her back. “Let me go!” she said. “I want to see the lions!”

“The problem is if the lions see you, little one.” He put her down as her mother came hurrying.

“Oh Dr. Birna! Thank you so much. Elizabeth, you must never wander off like that. You have to stay by the fires.”

“I want to see the lions!”

“Lions are very dangerous,” Dr. Birna said, kneeling down so that she could see his face, dark beneath white hair. “They know better than to attack a camp, but a child who wanders off alone is fair prey. You must do as your mother says and stay by the fires.”

“…stay by the fires…” She turned, reaching out.

“You are by the fire. There is nothing to worry about.” A man’s voice, calming, and she opened her eyes. She lay under alien stars, wrapped in a shearling blanket. The boy’s father bent over her. “You’re safe,” he said. “There are no predators here that will attack a camp as large as this.”

“Lions,” she said, sitting up. The dream and the present folded together seamlessly. She thought he was Dr. Birna for a moment, but who was Dr. Birna? His face, his name, and then it was gone.

The grandmother had also sat up, turning to face her. “Did you remember something?”

“Kenya,” she said. The name was there suddenly. “We were in Kenya.”

The man frowned. “I don’t know this world, Kenya. Is it your home?”

“No.” She shook her head, certain of that. “We were visiting. Traveling. My father…” His face didn’t come, but the sense of him did, the shape of his hands with a brush in them, brushing away red earth from bones. “He studied old things. Bones. Looking for clues about how humanity began. We were in Kenya and I was very small.”

“Do you have kin there?” the old woman asked gently.

“No. It was a long time ago. And my father is gone.” She knew that. He had died a long time ago, an old sadness long healed over.

And that was all — the shape of his hands, the brush moving quickly and carefully over bone, the light of the fires, the eyes in the dark, the radio playing a song about diamonds.

The man put his hand on her shoulder gently. “You don’t remember any more?”

The dream was fading. There had been the lions and Dr. Birna and he had handed her to a woman, to her mother…

“My mother called me Elizabeth.”

Chapter Two

Ronon jogged along the upper catwalks of the city, John following doggedly at his heels. He could still outdistance John easily, maybe even a fraction more easily than he’d been able to four years before, but he preferred the company. He appreciated it, too, as a sign that he hadn’t burned too many bridges with John in the last few months.

He’d screwed up, he knew, letting himself be tempted to use Hyperion’s weapon, and even worse in keeping it hidden when half the city had been looking for it. He’d gotten people killed in the process, not on purpose, but he still wasn’t proud of it. And he had to admit now that while it would have been worth a lot to get rid of all the Wraith, it wouldn’t have been worth killing everyone with the Gift. Not worth killing Teyla and Torren, who were as much his family as if she’d been born his sister.

And his duty had been to turn the damned thing over to his commanding officer. If he’d started to doubt some of the decisions his commanding officers made, now that they were making treaties with the Wraith and working with them as allies, disobeying orders still wasn’t the way to handle that. He still wasn’t sure how he was going to handle that, but he was trying not to think about it very hard.

Apparently that wasn’t working. He picked up the pace, grinning fiercely over his shoulder at John. “You got soft while you were in charge of the city.”

“A few weeks in a desk job isn’t enough to get soft.”

“So prove it,” Ronon said, and listened for the sound of running footsteps speeding up.

They sprinted to the end of the catwalk, and Ronon slowed his pace to let John catch his breath.

“See? Woolsey’s back in charge, and everything’s back to normal,” John said between gasping breaths.

“Yeah. I’m beating you.”

“Like I said, back to normal. Probably to everyone’s relief.”

“You weren’t so bad,” Ronon said. “At least having you in charge means having someone who isn’t completely stupid.”

“Thanks,” John said dryly. “You mean unlike Woolsey when he got here.”

“He wasn’t stupid,” Ronon said, considering more carefully. “But he didn’t know anything about how things work here.”

“He’s learned. We’ve all learned.” John looked at him sideways. “I thought you didn’t like some of my decisions very much when I was running the city.”

Ronon shrugged. “Do you like everything Woolsey decides?”

“I’m not Woolsey.”

“Carter, then.”

“Not everything. I didn’t like everything Elizabeth decided, for that matter. But I liked enough of their decisions that I didn’t mind following their orders.” John shook out his damp hair, and then added in an apparent effort at scrupulous honesty, “Most days.”

“I don’t mind following yours.”

“Most days?”

Ronon shrugged. “Ready to go again?”

“Bring it on,” John said, and Ronon started running again.

The outside seating at the mess hall was deserted in all but the finest weather Atlantis’s new home world had to offer. Daniel took advantage of the quiet, making his way to the rail and leaning against it to look up at the city, his hands in his pockets against the chill wind. The spires stretched for the sky, deliberately impractical, the exuberant creation of people who wanted to impress. Or maybe who just liked beautiful views.

After so many failed attempts to arrive in a position where he could see this particular beautiful view, it was hard to believe that he was actually standing in the city of the Ancients without any immediate disaster ensuing. The last time he’d been here, he’d barely managed to scratch the surface of the city’s mysteries before exploring the wrong laboratory had resulted in triggering a poorly designed Ancient weapon, leading to a disastrous encounter with the Pegasus galaxy Asgard.

He was sure that he’d have better luck this time. It would be hard to have worse luck, anyway.

Teyla came out onto the balcony and came to join him, turning to look up at the city herself.

“Do you ever get used to it?”

She tilted her head to one side curiously. “To what?”

He shrugged. “Living in the city of the Ancients.”

She shook her head, smiling a little. “I do not expect I will ever take living in Atlantis for granted. But after so many years, it has become my home.”

“That sounds nice,” Daniel said.

“It is for many people. But many others eventually wish to return to their own homes. The city is not for everyone,” Teyla said. “I have seen Earth, and it is a beautiful world. And a safer one.”

“I think safer depends on who you are.”

“If you choose to be on a gate team, you will not have a safe life, certainly,” Teyla said, sounding a little amused.

“No. But I wouldn’t rather sit around wondering if the Goa’uld or the Ori or whoever shows up next is going to take over Earth and enslave everybody or blow out all life in the galaxy like blowing out birthday candles. They’re candles, that—”

“I have seen many birthday celebrations for members of the expedition,” Teyla said, now decidedly amused.

“You probably have. Sorry, I tend to over-explain. My point is that I don’t think I’d feel better knowing that there were huge threats to Earth and not being able to do anything about them.”

“I agree,” Teyla said. “I too would rather act than stand by helplessly and wait for whatever comes. But it seems that many on your world are not aware of their dangers and would prefer not to be.”

“That’s not… ever really been a possibility for me. I keep asking questions until I find out the answers. Even if they’re unpleasant answers. Especially if they’re unpleasant answers. I’d always rather know the truth.”

“Even if it takes you far from home.”

“I’m not really sure I have a home. I have an apartment in Colorado Springs. I have friends there, and I like my job — all right, most days I like my job, although not the days when we get tortured by unpleasant people or have to deal with the IOA — but I’m not sure it’s really the same as having roots somewhere.”

Abydos had been his home, for a brief precious time. He wasn’t sure what it would take for him to feel the same sense of belonging anywhere, or the same sense of optimism and purpose. It was possible that he’d just gotten old enough to know better. But if he was going to feel it anywhere, Atlantis might be the place.

“I hope you find what you are looking for,” Teyla said.

He nodded. “So do I.”

Lorne stretched out his knee for Carson’s medical scanner to examine its internal workings. “How does it look, doc?”

“Better than it has any right to, given what you did to it,” Carson said.

“Hey, I got hit by a jumper. Being piloted by Dr. McKay, who was out of his mind at the time. I hardly think that counts as my fault.”

“All right, maybe not. But try to dodge next time.”

“I’ll keep that in mind,” Lorne said. “Maybe we need those warning beepers for the jumpers that they put on garbage trucks so you can hear them when they’re backing up. Except that it wasn’t backing up.”

“A warning beeper might not be a bad idea,” Carson said. “It would also help warn everyone about those of us who aren’t the best drivers.” Carson was a perfectly competent jumper pilot at this point — good, even — but he’d resisted learning with all his might in the early days of the expedition.

“Hey, it’s the hot-shot pilots you have to watch out for. They’re the ones trying to set the speed records.” Lorne sobered, swinging his leg off the table. “Seriously, though… ”

“The fracture healed beautifully. You shouldn’t have any long-term problems, although I want you to keep doing the stretches Dr. Keller prescribed.”

“That’s a relief.” He was acutely aware that getting killed and getting promoted weren’t the only ways to wind up sent back to Earth. For all its frustrations, he enjoyed his current job far too much to want to wind up stuck behind a desk back home.

“For someone who essentially got hit by a truck, you got off very lightly.”

“Don’t I know it,” Lorne said. “Have you heard anything from Dr. Keller?”

“She checked in a few weeks ago and sent me some of the results from her first round of tests of the new retrovirus,” Carson said. “Frankly she didn’t have many results yet to report. I think she just wanted to reassure everyone that she wasn’t dead.”

“Well, when you’re hanging out with the Wraith, people do worry.”

“I worry,” Carson said. “But not as much as Rodney does.”

“Are the two of them… I heard they split up. And also that they were on a break. And also that he asked her to marry him.”

“The Atlantis rumor mill never changes,” Carson said. “It’s like living in a small town full of elderly grannies gossiping over the back fence.”

“It’s probably none of my business.”

Carson shrugged. “It’s not as if either of them told me anything about it as their doctor. I don’t know what they’re doing. I don’t think they know what they’re doing. But she’s going to be gone from Atlantis for some considerable time, and maybe that will give them both time to think about what they want.”

“Absence makes the heart grow fonder?”

“Or presents enough distractions that you stop pining after the one you love. One or the other.”

“Distractions we’ve got.”

“Truer words were never spoken,” Carson said.

John sat in front of his laptop, trying to figure out how to frame the email he was thinking of sending.

Hi Sam, he began mentally. How’s it going? I was just wondering if you think there’s any chance that Elizabeth Weir is an Ascended being, rather than being dead in space because we couldn’t do anything to save her.

That sounded crazy. If he got that kind of email from someone, he’d think there was something wrong with them. Like they were having some kind of guilt complex about not being able to save people they cared about. So, screw that.

Hi Sam, he tried mentally composing again. Hope you’re having a good time on the Hammond. I was just wondering if there’s any chance that McKay is actually onto something rather than just being a little unhinged by having been turned into a Wraith.

He could just imagine Sam’s bemused expression reading that one. “I’m not a psychiatrist, Sheppard,” she would say, with that alarmed look she usually got when she had to deal with problems that involved people’s feelings. It was one of the things they understood really well about each other.

He made himself actually start typing this time. Hi Sam. Hope that you’re having as much fun getting shot at in the Milky Way as you did getting shot at here in Pegasus. A weird thing — McKay has started saying he thinks that Elizabeth Weir may have Ascended and showed up to talk to him in his dreams.

He took a deep breath. Believe me, I know how that sounds. Still, you’ve had some experience with this kind of thing, so I thought I’d ask you if that sounded like something that could possibly actually happen. McKay has this idea that she may have gotten in trouble for helping him and wound up getting kicked out of her higher plane. He keeps saying we ought to look for her, and you can imagine how that goes over with Woolsey. Dr. Jackson probably knows the most about it, but he just says “maybe,” only in a lot more words than that. And I trust your judgment. It’s always been good before. So any advice would be appreciated.

Say hi to the Milky Way galaxy for me,

John

He clicked to send the email before he could think better of it. He regretted it anyway the moment after it was sent, but by then it was too late; he shut his email and resolved not to think about the question any more until he got a reply.

“So what are we supposed to go look for?” Sheppard asked as Daniel came into the conference room, trying to keep his coffee cup from toppling off the top of his stack of books. Sheppard’s team had already staked out one side of the table, with Woolsey at its head. Daniel set down his tablet on the other side of the table, pushing his books to one side, although it made him feel a little like the unpopular new kid in the junior high school classroom.

He cleared his throat. “Well, I’m hoping we can find out more about the early history of Ancient settlement here in the Pegasus galaxy,” he said. “We know they came here after a plague wiped out most of the Ancients in the Milky Way galaxy. At that point, there wasn’t any intelligent life in the Pegasus galaxy. So, the Ancients started seeding planets with humans.”

“And built the Rings,” Ronon said. “We know.”

“Right, because the Ancients left a lot more traces of their presence here than they did on Earth, where we’ve just figured out they existed in the last decade. Okay, decade and a half.” It never ceased to startle him to be reminded that it had been more than ten years since he’d first walked through the Stargate. “Anyway. Various human civilizations developed over time, eventually there was the war with the Wraith, and the Ancients returned to Earth. We know a little bit about that period, but we know almost nothing about what happened when the Ancients first arrived in this galaxy.”

“We know they settled on Lantea,” McKay said. “Which we pretty thoroughly explored for any signs of Ancient installations other than Atlantis itself, and found zip.”

“I know that,” Daniel said.

“I know you know, I’m just reminding everyone.”

“Assume we’re all up to speed,” Sheppard said. “What are we doing?”

“Searching possible sites of very early Ancient settlement in Pegasus,” Daniel said. “In the Milky Way, they settled primarily on Earth and Dakara, but they had outposts throughout the galaxy. It seems likely that when they were seeding planets here with life, they actually spent some time on some of those planets, and may have left enough behind that we can get some idea of what they were doing.”

“Anything in particular we’re looking for?” Sheppard asked. “If they didn’t abandon these outposts in any particular hurry, I’m assuming they wouldn’t have left all their stuff behind.”

“I don’t expect we’re going to find a new super-weapon or a stash of ZPMs, if that’s what you mean. It’s very likely that any very early Ancient sites have been at least partially stripped, either by the Ancients themselves or by the local inhabitants. But even the layout of the buildings can tell us something about how the sites were used. And it’s possible that they left things behind that they considered unimportant, considered to be trash, even that will help us understand who they were and how they lived.”

He spread his hands in frustration. “That’s how actual archaeology works. As opposed to treasure-hunting, which, granted, is what we do around here a lot of the time. At best, I’m hoping we may find some surviving records from that era. We’re not likely to find anything you can use to shoot people.”

“I was actually just asking if there was anything in particular we were looking for,” Sheppard said after a moment.

It took Daniel a moment to shift gears. “Umm. Not really. Anything we find is going to increase our knowledge of Ancient settlement in the Pegasus galaxy from nothing to something.”

“I assume, Dr. Jackson, that you have some idea of where to start,” Woolsey said. He didn’t look particularly enthusiastic, but given his history with SG-1, it was saying something that he’d been willing in the first place to lend him Sheppard’s team.

“I actually have a couple of different ideas. First, I’ve been going through Janus’s records. He seems to have taken an interest in abandoned Ancient settlements here in Pegasus, possibly because he wanted to do his unauthorized experiments in places where no one was going to stumble across them by accident.”

“I’m getting a little tired of Janus and his experiments,” Sheppard said, although McKay brightened a bit.

“Janus doesn’t seem to have used any of these sites,” Daniel said. “Maybe he put this list together toward the end and then ran out of time before the Ancients went back to Earth, I don’t know. But it gives us a set of gate addresses to start checking out.”

Woolsey nodded. “You said you had two ideas.”

“I’d like to take a look at planets that show evidence of having been occupied by humans for a particularly long time. The original Athos, for example, we know that technological civilization developed there over and over again, with the Wraith knocking them back every time. But even before that, I think it’s clear that human settlement on Athos considerably predates the war with the Wraith.”

He sketched archaeological strata with his hands. “The problem there is that any kind of Ancient site is probably going to be buried under layer after layer of later cities built on top of it. But I’d still like to take a look around one of the Athosian cities and see if there’s any evidence that would support a larger-scale excavation effort. I was hoping that Teyla could get us permission from the Athosians to go take a look around.”

“I have spoken about this to Halling and Kanaan,” Teyla said. “I see the value myself of finding out more about our own past, as well as about the Ancestors. But my people are still debating whether to agree.”

“What’s the main issue?” Daniel asked.

“It is complicated. My people did not enter the ruined cities, for fear of attracting the attention of the Wraith. Things may be different now that we have a treaty with the Wraith, but that is very new. Some people are still not comfortable with the idea. And there is the larger issue of what will become of our original world if the treaty holds.”

“Do your people want to go back?” Ronon asked.

“Some do,” she said, and smiled at him. “Hearing that some Satedans have returned to their homeworld has inspired them. Others are worried that whether or not we return, Athos will be overrun by settlers from some other world interested in mining the old cities for their resources.”

“You mean the Genii,” Sheppard said.

“It would not be a surprise. And we must attract people to join us, whether or not we return to Athos. We are too few now to be a viable population alone. And we have always taken in refugees and travelers who wished to become Athosian. But they have always come a few at a time, and some of us worry about what will be lost if many people come who have no interest in becoming Athosian. My people do not want to become Genii.”

“I do see the problem,” Daniel said.

“There are others who are tired of moving from world to world and would prefer to stay where we have made a home, and still others who believe that because the Ancestors sent us to New Athos when they returned, it is where we ought to stay.” She shook her head. “It will take time for everyone to talk and come to a decision. In the meantime, I am afraid that any kind of mission to Athos would be perceived as the Lanteans staking a claim.”

“We aren’t going to jeopardize our relationship with the Athosians,” Woolsey said. “Dr. Jackson, I think you had better stick to the sites on Janus’s list.”

“We’ll do that,” he said. “I want to concentrate first on the sites that Janus has listed as being on currently uninhabited worlds, on the grounds that those are the sites least likely to have been stripped. First up is M4G-877. According to Janus’s notes, both the Ancients and the resident humans abandoned the planet because of hostile wildlife.”

McKay looked up with a frown. “How hostile are we talking about here?”

“If the Ancients couldn’t deal with it, I’m guessing that it’s pretty hostile,” Sheppard said. “Come on, Rodney, you know the drill. Planets with Stargates that are uninhabited are uninhabited for a reason.”

“Great. I’ll be sure to bring my dinosaur repellent.”

“It probably won’t be dinosaurs,” Woolsey said. The glances exchanged around the table suggested that no one else agreed.

Interlude

On the third day they came to a town, earth houses with roofs of sod, long grasses growing on the roof, their roots holding everything in place, so that from a distance all one saw was a group of rounded hills, thin streams of smoke rising from chimneys.

“We will ask if anyone knows you,” the grandmother said, though she sounded as though she thought that was unlikely. “You must have come from somewhere.”

“Maybe the Wraith left her,” the boy, Kyan, piped up.

“The Wraith don’t leave their prey,” his father said.

“The Wraith?” The name meant menace, though she did not know who they were.

The father and grandmother exchanged a glance. “They come through the Ring sometimes,” the old woman said. “But our Ring is in orbit. They cull now and again, but we are a lot of work for a very small harvest. Mazatla has no cities.”

“This world is Mazatla.” Elizabeth frowned. The name ought to mean something. The name of the world she was on ought to be important, but it wasn’t.

“Yes.” The old woman nodded. “But Wraith or not, something bad has happened to you. Rest and heal, and perhaps it will all come back.”

“I shouldn’t be on Mazatla,” Elizabeth said. “It’s not my world.” A ring, a ring turning in a flash of blue fire… And then it was gone.

“Rest and try to remember,” the man said. “We’ll ask at the Gathering if anyone knows you or knows your people. We’ll stop here tonight and then go on to the Gathering at the Place of Two Rivers.”

“The Place of Two Rivers.”

Two rivers wreathed in mist, gray as steel beneath a winter sky, flowing together at a green point… There were bridges over the rivers, struts of iron against the sky woven like baskets of steel. One long span crossed on brick arches, iron rails dark with coal cars… Down the river, smoke rose from high smokestacks…

“Two rivers,” she whispered. “A city where two rivers came together.”

“Your home?” the grandmother asked.

Summer, and a green park full of people, boats on the river while above the sky lit with flowers of fire, green and gold and purple and blue, while she sat on a blanket.

“A festival,” Elizabeth said. “At the end of summer. To celebrate the working man?” The words came back slowly. “There was a boat race on the river between steamboats. We watched from the park where the fort had been. There were people on the bridges watching and cheering. I had a red balloon because it was my favorite color. We ate ice cream when it got dark and waited for the fireworks.” Her parents were there. She was older, old enough to go to school. “The City of Three Rivers.”

“Do you remember why you were there?” the man asked.

Elizabeth nodded slowly. She remembered, or at least the child she had been did. “My father, he had work there. We had come back after Kenya and we were going to stay. There was a building.” The pictures slipped away, and she grabbed at them. “A very tall building with classrooms in it. Very tall. Twenty, thirty, forty stories. A cathedral to learning? I don’t know.” And then it was gone again, the memories slipping just out of reach, words she had almost found. But she knew one thing. “I am from the City of Three Rivers.”

The grandmother looked at the father. “Sateda,” she said.

Elizabeth looked up. “Sateda?” The name was familiar, but…

“It sounds like the things they had on Sateda,” she said. She put her hand on Elizabeth’s shoulder. “Sateda was destroyed by the Wraith years ago. A few people escaped but they wander. They have no homes. Maybe you are Satedan.”

Satedan. The word was familiar. “Maybe so.”

“If so, you’ve been wandering a long time,” the father said. “I don’t know how you got here.”

“I have to get back there,” Elizabeth said. That was one thing she was certain of. “I need to go home.”

“There’s nothing left of Sateda,” the old woman said gently. “The Wraith destroyed everything. They killed everyone they could find. It’s gone.”

“I have to get there,” Elizabeth said. If the City of Three Rivers was there… “I have to find out what happened.” What happened to someone. Who? Who was she worried about?

“We could ask the Travelers,” the grandmother said. “Sometimes they come to the Gathering. They might know other Satedans. Sometimes they’ve had Satedans working on their ships.” She looked at Elizabeth. “You know machines?”

Elizabeth nodded. “Machines. Yes. Radios and computers and guns.”

“Sateda,” the man nodded. “You’re Satedan. Well, let’s see if the Travelers come and if there are Satedans with them.”

“I need to go there.”

The old woman patted her hand. “Sateda is gone. But perhaps we can find your people. Or you will find a place with the Travelers as other Satedans have.”

The word spread around the Gathering about the woman with no memories, and lots of people came to see her. They camped in the flood plain of two sleepy brown rivers, five thousand people or more, with bright tents in all the colors of the rainbow. The Mazatla did not live in cities, but in the summer there were these gatherings at various traditional locations, part fair, part sports meet, part courtship opportunity. Goods and animals were traded and sold, and there were matches of a game that involved throwing balls back and forth between three teams on an enormous staked out triangular field that went on all day until sunset ended the game. Then the victors paraded by torchlight, beginning a dance that went until dawn.

Elizabeth shared the tent of the family that had found her. When people came to see the woman with no memories she greeted them eagerly. Perhaps they would know where she had come from! But no one did. Each curious person at last went away shaking their heads. The woman with no memories had come from nowhere.

“The Travelers may know you,” the grandmother said confidently. “If anyone here does, they will.”

The Travelers arrived on the third day. Elizabeth heard shouts and went outside. A spaceship was descending from the blue sky streaked with a few high clouds, its white contrail bright. She raised her hand to shade her eyes, everyone else shouting and pointing too. It was bigger than…

Bigger than what? The comparison she’d meant to make slipped away. Bigger than a small ship meant to carry six to ten people. And smaller than…

Elizabeth frowned. A man in an olive green jumpsuit, bald headed, severe. He had a ship, a ship that was bigger than this one, and yet his name and the name of the ship ran away, lost somewhere among other things forgotten.

‘It’s the Travelers!” the boy Kyan said. He pulled on her arm. “They’ll help you get home.”

His father looked worried. “Only one ship this year. Something can’t be right.”

“Maybe it’s because of the Wraith,” Kyan said.

“Let’s hope not,” his father replied, and they walked together to the part of the field where the ship had landed.

Close up, the ship looked battered. It wasn’t all the same color, and parts of it looked as though they’d originally belonged to another ship, including a pair of long, organic looking weapons emitters. There was something disturbing about them, something inhuman.

The man coming down the ramp to cheers and greetings was entirely human. He was white haired and burly, wearing a bright red jacket over a jumpsuit. “Hello everybody! We’re glad to be here. Give us a few minutes to unload, folks. Then we’ll be glad to trade with everybody.”

“Lesko!” A man was pushing through the crowd, which parted when they recognized him as Elizabeth did, one of the Mazatla Leading Men, elected to govern this year. “Any news of the Wraith?”

Lesko held up his hands as everyone quieted. “Queen Death is dead.”

“I know,” Elizabeth murmured, and the grandmother turned to look at her.

No one else had heard, and there were shouted questions.

Lesko held up his hands again. “An alliance of other Wraith and the Lanteans and the Genii killed her.”

“The Genii?”

“What did the Lanteans…”

“How could…”

“The Genii have a warship belonging to the Ancestors,” Lesko shouted over the din. “It was flown into battle by the Leader Ladon Radim with the assistance of a Lantean pilot, Lorne. It defeated Queen Death’s ship and then the Genii boarded it. They killed Queen Death.”

Shouts, cheers, people slapping each other on the back…

Elizabeth felt strangely isolated, wrapped in private quiet. Lorne. Ladon Radim. Should she know those names? Why couldn’t she find faces to go with those names?

She missed the question, someone shouting how Lesko knew.

“I heard it from the Genii myself,” he called back. “They showed me the video of Radim’s speech. They showed me the video the Genii took inside the hive ship.”

“But there are other Wraith,” someone said.

Lesko nodded. “The Genii and the Lanteans are making a treaty with them. Some of the other Wraith attacked Queen Death too.”

“A treaty with the Wraith?” the grandmother said incredulously. “You can’t make a treaty with the Wraith.”

“You can make a treaty with anyone,” Elizabeth said. “With the right leverage.”

“Don’t be ridiculous,” someone behind her in the crowd said.

“Don’t be ridiculous, Elizabeth.” She was sitting at a desk in a room full of people, looking up at a green board covered in words. A man was leaning over her, dark rims to his glasses, dark hair. “You can’t negotiate with people bent on global domination.”

“I don’t see how you can fail to,” she responded. Her hands were young and thin and she wore a white sweater with blue floral trim around the wrists. “What other choice do we have? To simply say that we acquiesce? Or that we consider global thermonuclear destruction a viable alternative? Chernenko is a rational man…”

“It is not rational.” Mr. Henry’s mouth pursed. That was his name, Mr. Henry. He was her teacher. She was fifteen years old. “The Soviet Union does not pursue rational foreign policies, but rather ideological ones. Even when faced with Mutual Assured Destruction…”

“Surely there are rational voices.”

“The rational voices are powerless.” Mr. Henry shook his head. “As are those elements in the Eastern Bloc who oppose him. I’m sorry to tell you, Miss Weir, but Solidarity is just as doomed as the Prague Spring or the rebels in Budapest in 1955. The moment tanks roll into Gdansk…”

Elizabeth blinked. Kyan was shaking her arm. “Are you ok?”

“Yes,” she said. The crowd was still yelling questions, though Lesko held up his hands.

“All in good time!” he said. “Come on now. Let my people unload. We’ll have plenty of time for news.”

“Did you remember something?” Kyan asked cheerfully.

“Yes. I think.” Elizabeth shook her head. There was no more of it, just that moment, that frustration, those words that were so freighted with meaning that no one here would know.

Elizabeth put her hands at her side, watching the Travelers. Who am I? she thought. Who am I to feel that I should carry such responsibility?

“This is Atelia Zel,” the grandmother said. “Atelia, I’d like you to meet Elizabeth. She is the woman with no memories I told you about.”

“I’m pleased to meet you,” Elizabeth said.

They stood in the shade of the Travelers’ ship, its bulk casting deep cool shadows. A striped awning had been rigged and their wares were laid out on the tops of boxes and shipping crates, bulky things in front and the most valuable things displayed on cloths back near the open hatch where the sellers could keep their eyes on them. Lesko and a number of others haggled with the Mazatla, trading food for cloth, hides for medicines. Some few of them, the most valuable, were kept in a strong box, bottles neatly labeled and swathed in cloth. She only saw them for a moment, but some of them… There was something wrong, something familiar about them. Ramipril 10 mg… Erythromycin…

“Atelia is Satedan,” the grandmother said, calling her attention back, and Elizabeth turned to look at her.

Atelia Zel was of average height and young, with lighter skin than the Mazatla but not as pale as Elizabeth’s. Her black hair was braided tightly to the scalp, each braid worked with a single strand of gold thread. A little boy perhaps a year old peered curiously over her shoulder from a harness worn on her back over her spacer’s coveralls. He looked at Elizabeth curiously, then gave her a four-toothed smile.

She smiled back. “What a beautiful baby!”

At that Atelia smiled too. “Thank you. He’s a handful, and I have to watch him every minute so he doesn’t get into things.” Her eyes searched Elizabeth’s face as if looking for something familiar. “They said you might be Satedan?”

“I don’t know,” Elizabeth said. “I don’t remember much before I found myself on this world. Everyone here has been very kind to me, but nobody knows me or where I came from. The few things I do remember cities, technology, suggest to these people that I’m Satedan.” Even as she said it, it felt wrong. And yet this young woman’s face was like so many she’d known, her clothes, the casual way she handled the electronics…

“What do you remember?” Atelia asked.

“Cities. Buildings with many stories. Vehicles.” Elizabeth shook her head. “Steel bridges over rivers.” Her eyes fell on the bottles carefully swaddled in the compartmented box. “Bottles like that. A hospital where sick people went for operations…” Corridors with nurses in white, a kind dark haired man with an instrument around his neck who stood outside her father’s room, talking to her in a low voice…

“We had hospitals and high rises,” Atelia said. “Medicines like these.”

“Are those from Sateda?” She didn’t quite pick them up. Not quite.

Atelia shook her head. “Not these. All our cites were destroyed and all our industries too. These came from the Genii who traded with the Lanteans for them.” She touched the one labeled Erythromycin gently. “These pills are for people who have a sickness in their lungs, a cold that has gone to the chest and their lungs are filling with fluid. When nothing else will save them, these pills will.” Her eyes searched Elizabeth’s face. “It’s a wide spectrum antibiotic for respiratory infections. Do you understand what that means?”

“Yes,” Elizabeth said, though she couldn’t have said how she knew. “For pneumonia.” And it was a good thing, somehow, that these pills were here. A cheap drug, worth almost nothing per dose, rendered nearly priceless to these people, just as she’d seen it in clinics, where? She looked at Atelia. “Are you a doctor?”

Atelia laughed. “I’m a scholar. Or I was going to be. But all that ended a long time ago.”

“How did you escape when your world was destroyed?”

“I wasn’t there.” Atelia looked up at the awning above, put her head back against the baby’s cheek. “I was in my last year of studies. I was going to be a scholar who studied other peoples, finding the common threads of culture that help us understand who we are and where we all came from. I was doing field work when Sateda was attacked.” Her mouth pursed. “Everyone I knew was killed.”

Elizabeth put her hand on her arm. “I am so sorry. And so sorry to have asked.”

“It was a long time ago.” Atelia forced a smile. “And I’ve found a place with the Travelers. The technology that everyone understood on Sateda is rare and complicated everywhere else. I have skills that are valuable. I understand what these do.” She touched the bottle. “I learned.”

“And you have a family,” Elizabeth said.

“Oh yes.” She nodded, glancing back over her shoulder at the little face behind hers. “I have a son and a husband, though he’s not with us now because he’s a Hunter.”

“What does he hunt?” Elizabeth asked.

Atelia’s smile wasn’t nice at all. “He hunts Wraith.”

Chapter Three

The iris filled with blue as the gate opened, and Daniel leaned back in his seat as John threaded the needle’s eye neatly with the jumper. He was used to missions beginning with a hike, and found it an unaccustomed luxury to be able to take the jumper and as much gear as he wanted to haul along without having to be able to carry it all on his back.

They came through the gate into bright sunlight, grassland stretching out around them as far as Daniel could see. The grass was amber rather than green, seed heads swaying in the wind that the jumper kicked up. The distant horizon swam with heat.

“All right, listen up, I’m only going to say this once,” Rodney said.

Sheppard spoke up from the pilot’s seat. “Promise?”

“No.” It was easy banter, comfortable, and it made Daniel wish for a moment that his own team was there. He hadn’t been able to justify why he needed SG-1 on this mission — it had been hard enough making a case for him to stay and continue his research rather than going back to work — but he wished Sam were there. Although of course Sam wasn’t on SG-1 anymore.

“This planet has a high-oxygen atmosphere,” Rodney went on. “Anything that burns here is going to burn fast and hot. Anything that strikes a spark is extremely likely to start a fire. These?” He held up his P90. “Likely to strike sparks.”

“We get it,” John said. “No weapons fire unless it’s absolutely necessary.”

“My gun doesn’t fire bullets,” Ronon said.

“No, it fires directed energy. Did what I just said make that sound like a better idea to you?”

“We will not fire except as a last resort,” Teyla said. She glanced at Daniel, as if making certain that he was paying attention, and he nodded.

“Got it.”

“Hopefully there won’t be anything to shoot at,” John said.

“Hostile wildlife,” Rodney said, as if John might have forgotten.

“Thousands of years ago. Maybe they’ve moved on. Dr. Jackson, any idea where we should be looking for your archaeological site?”

“The records mentioned a river near the gate.”

“For some definition of ‘near,’” Rodney said.

Ronon rolled his eyes at him. “It’s not like we’re having to walk.”

Jinx, Jack would have said. Daniel shook his head, wondering why he was thinking about the early years of his team rather than the actual team he’d left behind. He wasn’t nostalgic for those days, he told himself. Nostalgic for the people he’d worked with then, maybe, but not actually for those early days of blundering in the dark, making lethal mistakes more often than they solved problems.

They hadn’t even known what questions to ask, then, and there had been no time to look for answers that weren’t immediately useful. Now, finally, he had the luxury of doing real archaeology, the kind that didn’t involve trying to shoot pictures of artifacts while being chased past them by enemy troops. It was hard to remember how that even felt. He tried to summon up his old enthusiasm for the beginning of a dig, the promise of answers to questions he hadn’t even thought of yet, and couldn’t quite recapture the feeling. All he could think of was how many questions there were, and how inadequate the answers always seemed.

“All right,” John said. “It looks like there’s a river about thirty klicks to the northwest of here, so let’s go check it out.”

Ronon leaned over Rodney’s shoulder to look out the front window. “What are we looking for?”

“Hopefully, visible buildings,” Daniel said. “Or mounds that have accreted over buildings. I’m hoping we won’t end up having to dig too much.”

“It would have been nice if they’d built a road,” John said.

“They probably did, but we’re talking about thousands of years, here. It could be under meters of dirt, and I don’t see anything that looks like the track of a road here. You might try the jumper’s sensors, though. If the road was paved, you may be able to pick up the building material as distinct from the soil in the local area—”

“Already on it,” Rodney said, his hands flying over the console in front of him. “And voilà.” The jumper’s screen now displayed an enhanced version of the scene outside, clearly showing a three-meter strip of irregular paving stone stretching from the gate to the northwest.

“Nice,” Daniel said.

John nodded, one hand moving affectionately over the jumper’s controls. “You ought to get yourselves one of these.”

“You know, we’ve asked, but that keeps not happening.”

“Oh, please, you have a time traveling jumper to study,” Rodney said. “You know we’ve asked for that back, right?”

“It’s like they think we would use it,” John said.

“Only as, you know, a last resort,” Rodney said. Teyla and Ronon exchanged a skeptical look.

“That’s always how it starts,” Daniel said. He squinted at the haze of trees now visible to the northwest, and then at the display scrolling across the screen. “It doesn’t look like the road goes all the way to the river. Take us a little lower.”

John obliged, bringing the jumper down to skim low enough over the grass that it billowed in the wind they kicked up.

“There,” he said, pointing to a stand of scrub trees and bushes far short of the meandering green line of the river’s course on the horizon.

“That’s not near the river,” Rodney said.

“It used to be. Look at the contours, there’s a depression here just the right shape to be an old ox-bow. The river meanders, a loop gets cut off, it turns into a lake, then eventually the lake dries up. What was an outpost next to the river turns into an outpost sitting in the middle of a field. But those trees suggest there’s still some source of water there, try running a more tightly focused scan.”

The display on the console shifted as John gave instructions to the jumper, and Rodney’s skeptical look changed to one of focused attention. “Oh, that’s definitely man made,” he said. “There’s some kind of rectangular structure down there. And metal piping running down to the water table.”

“The Ancients sunk a well. It’s probably leaking, and the water source and the slight windbreak caused by the depression in the ground is how you get trees.”

John frowned as he brought the jumper lower. “Why would the Ancients put in a well if this used to be right on the river?”

“Ah… I’m not entirely sure. Maybe the river water wasn’t drinkable without purification, which makes sense if there was a lot of native wildlife. Or maybe they didn’t want their water source to be dependent on the river’s present course.”

“Taking the really long view?”

“They did that. We’re talking about people who seeded entire civilizations. The chance of the river changing its course in a few hundred years might have seemed like next week’s problem to them. Try not to put us down right on top of the archaeological site, please.”

John set the jumper down well clear of the structure, and Daniel climbed out, pushing his way into the chest-high grass that crunched dryly underfoot as he walked. Teyla fingered a stalk, frowning.

“Problems?” John said, looking sideways at her.

“We call this tindergrass,” she said. “It grows in burned-over fields and other places where there has recently been a fire.”

“I wouldn’t say recently,” John said, pushing dry seed-heads aside as he plowed through the tall grass.

“It grows very quickly. And it burns very easily itself.”

“So would soaking wet wood, in this atmosphere,” Rodney said. “That’s why we’re all going to be really careful—”

“We get the picture,” John said.

Ronon turned abruptly, drawing his pistol, and Rodney slapped his arm. “What did I just say!”

“I thought I saw something.”

“Probably some kind of animal,” John said.

“I figured that, yes.” Ronon pushed his way some distance through the tall grass away from their path, and crouched to brush the grasses aside. “There’s a trail here.”

“Now we get the tyrannosaurs,” Rodney said.

Ronon grinned. “Only if they’re two feet tall.”

“There were small dinosaurs,” Rodney said. “Small but vicious. Probably poisonous.”

“Can we put a hold on the extreme pessimism until we actually get to the site?” Sheppard brushed sweat out of his eyes with the back of his hand. “Please?”

“I think they’re little grazing animals,” Ronon said. “These look like hoofprints.”

“So, probably not really scary.”

“Famous last words,” Daniel said.

There was a sudden rustling in the grass, coming rapidly toward them. Daniel drew his own pistol despite Rodney’s warnings, although he didn’t thumb the safety off. Ronon and Teyla turned toward the sound, backing warily away.

Several small brown forms exploded out of the grass and raced across their path, hooves beating the ground. Everyone stared after them for a moment as they vanished into the sea of tall grass on the other side.

John adjusted his sunglasses, as if they might have been affecting his vision. “Were those horses?”

“Really short horses,” Ronon said. “With fangs.”

“They did not have fangs,” Rodney said.

“You’re right, they didn’t.”