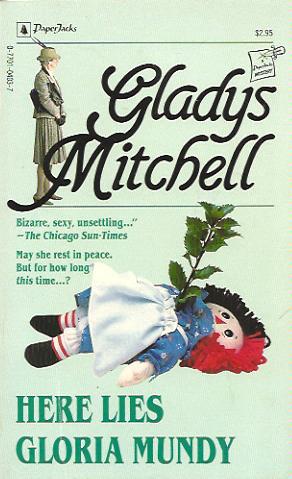

Here Lies Gloria Mundy

Gladys Mitchell

Bradley 61

A 3S digital back-up edition 1.0

click for scan notes and proofing history

Contents

chapter 1: a case in the papers

chapter 2: chance encounter

chapter 3: beeches lawn

chapter 4: unbidden guest

chapter 5: chapter of accidents

chapter 6: arson

chapter 7: ichabod

chapter 8: hounds in cry

chapter 9: chaucer’s prioress

chapter 10: colloquies

chapter 11: a conference with the accused

chapter 12: recapitulation with surprise ending

chapter 13: the revenant

chapter 14: unexpected developments

chapter 15: little progress

chapter 16: attempt at a volte-face

chapter 17: a letter from dame beatrice

chapter 18: exit gloria

chapter 19: a kind of pilgrimage

Also by Gladys Mitchell

SPEEDY DEATH

MYSTERY OF A BUTCHER’S SHOP

THE LONGER BODIES

THE SALTMARSH MURDERS

DEATH AT THE OPERA

THE DEVIL AT SAXON WALL

DEAD MAN’S MORRIS

COME AWAY DEATH

ST. PETER ‘S FINGER

PRINTER’S ERROR

BRAZEN TONGUE

HANGMAN’S CURFEW

WHEN LAST I DIED

LAURELS ARE POISON

THE WORSTED VIPER

SUNSET OVER SOHO

MY FATHER SLEEPS

THE RISING OF THE MOON

HERE COMES A CHOPPER

DEATH AND THE MAIDEN

THE DANCING DRUIDS

TOM BROWN’S BODY

GROANING SPINNEY

THE DEVIL ‘S ELBOW

THE ECHOING STRANGERS

MERLIN’S FURLONG

FAINTLEY SPEAKING

WATSON’S CHOICE

TWELVE HORSES AND THE HANGMAN’S NOOSE

THE TWENTY-THIRD MAN

SPOTTED HEMLOCK

THE MAN WHO GREW TOMATOES

SAY IT WITH FLOWERS

THE NODDING CANARIES

MY BONES WILL KEEP

ADDERS ON THE HEATH

DEATH OF A DELFT BLUE

PAGEANT OF MURDER

THE CROAKING RAVEN

SKELETON ISLAND

THREE QUICK AND FIVE DEAD

DANCE TO YOUR DADDY

GORY DEW

LAMENT FOR LETO

A HEARSE ON MAY DAY

THE MURDER OF BUSY LIZZIE

A JAVELIN FOR JONAH

WINKING AT THE BRIM

CONVENT ON STYX

LATE, LATE IN THE EVENING

NOONDAY AND NIGHT

FAULT IN THE STRUCTURE

WRAITHS AND CHANGELINGS

MINGLED WITH VENOM

NEST OF VIPERS

MUDFLATS OF THE DEAD

UNCOFFIN’D CLAY

THE WHISPERING KNIGHTS

THE DEATH-CAP DANCERS

LOVERS, MAKE MOAN

here lies gloria mundy. Copyright © 1982 by Gladys Mitchell.

All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. For information, address St. Martin’s Press, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010.

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Mitchell, Gladys, 1901-

Here lies Gloria Mundy.

I. Title.

PR6025.I832H4 1983 823'.912 83-2924

ISBN 0-312-36986-7

First published in Great Britain by Michael Joseph Ltd.

First U.S. Edition

To

QUENTIN

who, like St Joan, has accepted

the burdens which are too heavy

for the rest of us

1

A Case in the Papers

^ »

At school I always insisted that my first name was Colin. This is an acceptable name among boys. My baptismal name of Corin is not, although why this should be I don’t know. Can one consonant make such a difference?

The trouble is that I have a twin sister whom my father was determined should be christened Corinna. My mother wanted her called Oenone, so, to settle the matter, they agreed upon Corin and Corinna, much to my youthful discomfiture. Talk about ‘Hello, twins!’

When I got to university, however, I realised that it was no bad thing to have a name which, so far as I know, has nothing but literary connections, so I reverted to Corin and have become, in a modest way, part of the contemporary scribal scene. That is to say, I earn my living as a writer under the name of Corin Stratford. Stratford is not my patronymic, but nowadays most people use it, as I have made it clear that it is in my professional interests that my name should be publicised as much as possible.

I was determined not to tie myself down to a nine-to-five job, but neither was I prepared to do a Mr Micawber and wait for something to turn up. My father was willing to continue my small allowance — as much as he could possibly afford — for a couple of years after I left college, but after that I had to fend for myself. Fair enough, I thought. I had faith in myself and decided to make my name the appendage to a modicum of fame even if I starved while this was happening.

‘Does the road wind uphill all the way?’ asked Christina Rossetti. Well, it certainly did for me, but, after a hard slog, the way up has eased to a gentle gradient and at the beginning of this year I found myself, if not affluent, at least able to afford a small flat in Baker Street instead of being in digs, and to take a holiday when and where I chose.

I had been in the flat for only a fortnight when I read about the murder of a young woman who had been living in one room in the neighbourhood of Earls Court.

I had done some freelance work for Dawn Chorus, the paper which carried the fullest coverage of the murder, so I telephoned and was told (as I had expected) that the story was being covered by the paper’s own reporters. However, I was also told when and where the inquest was to be held, and I decided to attend it, since it seemed to me, judging by the account given in the papers, that, after a lapse of time and some artful manipulation of the facts, a lucrative bit of fiction might evolve. It was a long-term proposition, but I am a patient man and so much inured to delays, frustrations and disappointments that I have become something of a philosopher and content to bide my time.

The coroner’s court was full, for any chance of obtaining free entertainment is not to be missed. I managed to get a seat next to one of the Dawn Chorus reporters just before the coroner got to work. Compared with the luridly written-up account of the murder in the newspaper, however, the proceedings were colourless and dull. Evidence of identity and the medical evidence were dealt with and the police then asked for an adjournment.

Assisted far more by the account in Dawn Chorus than by the court proceedings, I roughed out a story as soon as I got back to my flat after a pub lunch in the Earls Court Road, and then I put my notes aside to ferment and then mature.

The story was commonplace enough. The murdered woman had spent some time in America, according to the sleazy old party who gave evidence of identity, and had been lodging in London for a matter of six years. During that time she had had visitors of both sexes, some of whom claimed to be relatives, although the landlady did not believe this.

The landlady had no rules against visitors. (This I got from the newspaper. It was not mentioned at the inquest.) They were, according to her, all of them respectable people, quiet, well-behaved, never stopping more than a couple of hours and certainly never staying the night. The reporter who recorded this had managed, with cunning skill, to query most of it without actually appearing to cast doubt on the landlady’s assertions. I am sure he was worth his pay. I knew his work, and admired it, although I could not have emulated it. Suffice to say that, however close to the wind his paper sailed, so far it had never been involved in an action for libel, although there were rumours of sums having exchanged hands out of court.

When I learned that the murdered girl had had a baby with her when she arrived and that the child had been taken into care only after the death of the mother, I discounted the Dawn Chorus innuendoes. Ladies of doubtful virtue do not discourage their clients by having to get up in the night to soothe or feed an infant, nor do they want a six-year-old sharing the bedroom. Also, as the reporter, to his credit, did not fail to point out, the child had never been neglected or ill-treated.

One item which the newspaper had got hold of was that the girl was on her way to find out more about a situation as chambermaid in a hotel near Brighton when she met death. How she had come to hear of the post remained a mystery. The landlady thought she had heard of it through a friend, not by reading an advertisement, but there was no proof of this, or of who the friend might be.

From that journey she never came back. When she did not return, the landlady took it for granted that she had been given the job and had begun work, but after a day or two, during which the girl had not come for the child, the landlady began to wonder, especially as one or two people came to enquire after the girl and she could tell them nothing. Then a young reporter somehow got hold of the landlady’s story and asked for the address of the hotel, but all that she could supply was its name. He went to the police. He knew the London to Brighton roads very well, he told them, but had never seen a hotel, pub or roadhouse with the name the landlady had given him.

A few days later the body was found washed up near Hastings. It had not drowned; there were no signs of sexual assault; death had resulted from stab wounds, one of which had penetrated the heart.

The police began their usual painstaking work and the papers soon dropped the case. Shorn of any salacious details, it made dull reading after its first impact. I myself was somewhat disappointed in it as it stood, but I set aside my notes again, with the reflection gained from Rabindranath Tagore that ‘Truth in her dress finds facts too tight. In fiction she moves with ease.’

I never wrote the story because, merely through a chance meeting with a friend I had not seen for years, I was caught up in a far better one. All the same, I did go to see the landlady.

‘You’ll have to pay me for my time and trouble,’ she said. ‘I’m sick of giving you lot something for nothing. Show me a couple of quid and I’ll show you her room, what I have not yet let, and I’ll answer your questions up to a quarter of an hour, my time being money.’

‘I’ll skip the bedroom,’ I said. ‘That ought to be worth at least another five minutes of your time.’ I gave her one pound and showed her the other, to be handed to her when our conversation was finished.

‘You might as well be one of them mean-fisted coppers,’ she grumbled; but she answered my questions and received her money well within the agreed time.

‘You say she was after a job in a hotel. Did she have a job before that?’

‘Bits of charring. I reckon, though, as she got bits of money from America, where she come from.’

‘What makes you think so?’

‘She got letters regular with postal orders in ’em.’

‘How do you know that they came from America?’

‘I don’t know it. She always got to the front door before I did, to pick up the post.’

‘If you know the letters contained postal orders, I still wonder what makes you think they came from the United States. Dollar bills or something in the nature of a cheque would be more likely.’

‘That ’ud mean a bank. She never went to no bank, only to the post office.’

‘You followed her, then?’

‘No. I wanted to buy a stamp for me own letter to my boy what’s serving the Queen in Germany, didn’t I?’

‘Did she ever stay out at nights?’

‘She’d have been out of here P D Q if she had. This is a respectable house I’d have you to know.’

So that was that, and my notes remained unused.

2

Chance Encounter

« ^ »

When I ran into Hardie Keir McMaster after a lapse of seven years it was at one of the more unlikely places, for it was outside the south door of a church. There had not been a wedding or a funeral; neither was it a Sunday, so I could only conclude that he was there for the same purpose as I was. This was to take a look at the church itself, a most surprising thing for him to do. At college he had been one of our ‘hearties’ with, so far as anybody knew, no interest in either art or architecture.

As well as being a freelance journalist, I am a novelist and biographer. With regard to the first, I look hopefully for commissioned articles and can supply these on any subject covered by the Encyclopaedia Britannica, but for the other two I please myself. At the time I had just published my third novel. My biography of Horace Walpole was still selling, and the royalties had just come to hand, so I was taking a little holiday, ‘resting’ as actors call it, and that morning I had driven in my car to Herefordshire to look at Kilpeck church.

Kilpeck church is unique. I had heard of it from friends and had seen photographs of its south door. I was prepared for the south door, but not to see McMaster standing in front of it. I was more than surprised, but I could not mistake that massive six feet three, those mighty shoulders, the firmly planted feet and, still less, that Viking thatch of yellow hair. I went up and thumped him on the back.

It was an ill-judged act. He swung round and nearly knocked me flying. However, he collected me, planted me in front of him, held me at arms’ length and said, ‘Well, I’m damned. Just the very man!’

‘How are you, Hara-kiri?’ I asked. He had been given the title at college. He had played prop forward for us and some wit had christened him with a joke on his first names of Hardie Keir because it was alleged to be tantamount to committing suicide if you tackled him on the field. Off it, a sucking dove might have envied him and even striven to emulate him, for he was normally the gentlest and most amiable of creatures.

‘Corin Stratford, by heaven!’ he shouted. ‘What on earth are you doing here, you old son of a mermaid?’

‘Taking a photograph of the south door of this church, when you move your great carcase out of the way,’ I said. Unmistakeably of its period, the south doorway of Kilpeck church nevertheless bears some striking and unusual features. Like many late Norman doorways, it is extensively decorated, and among the decorations are two warriors wearing trousers, Phrygian caps, and tunics of chain mail. I had read that the whole doorway is a representation of this sinful world of lust and strife, but it also holds a promise of better things to come, for in the concentric double tympanum arch is the Tree of Life, and on the jamb a writhing serpent is shown, head downwards in defeat.

There is a suggestion of the Saxon origin of the church in the style of some of the carvings, but even more obvious is the Celtic influence. Moreover, on the west wall of the church I had seen gargoyles in stone which could only have derived from the carved wooden prows of Viking ships, so the church is an epitome of local history.

‘Let’s walk round,’ I said. ‘There’s a corbel-table underneath the eaves. There are birds and beasts and human heads. There is even a sheila-ma-gig.’

‘You mean a thingummy-jig,’ said McMaster.

‘No, I don’t. I mean a sheila-ma-gig. She’s a rather rude lady who appears on some Irish churches. My guess is that she represents something fairly unspeakable from the Book of Revelations. Anyway, compare her with the crude Australian term “sheila”, meaning a woman and used, I always think, in a derogatory sense. After I’ve identified her, if I can, I’m going inside the church. There’s a notable chancel arch. After one has looked at these warriors and the serpent, and has seen the lion and the dragon fighting each other as depicted on this doorway, the chancel arch promises the peace of heaven, so that the church preaches a sermon in stone.’

‘See you later, then,’ he said. ‘I’m going to look at the gravestones. I collect curious epitaphs.’

I laughed. ‘I know one or two,’ I said.

‘ “Mary Ann has gone to rest,

Safe at last on Abram’s breast,

Which may be fine for Mary Ann,

But sure is tough on Abraham.” ’

He laughed, too.

‘That’s apocryphal,’ he said, ‘and, anyway, I know it.’

‘All right, then. What about this one?

‘Here lies that old liar Ned,

But he can’t lie because he’s dead,

For now he lies on heaven’s shore,

Where he don’t need to lie no more.” ’

‘Where did you get that?’

‘From a chap in a pub in Bristol.’

‘It’s difficult to get them authenticated,’ said McMaster, ‘when they’re only given you by word of mouth. I got a beauty in East Anglia once, but the chap couldn’t name the church. It was:

‘Poor Dimity Ann,

Her tooken one can

Too many, so her vomit,

And that done it.” ’

‘Well,’ McMaster concluded, ‘see you when you’ve gloated over your Sheila.’ He pointed to one of the figures carved on the uprights of the doorway. ‘Talking of sheilas,’ he said, ‘I wish that fellow didn’t remind me of Gloria Mundy.’

‘Gloria mundi, according to the learned professor who tried to teach me Latin,’ I said.

‘No,’ said McMaster, ‘I don’t mean the glory of the world. I mean a girl I used to date until I found out what a little tramp she was and ditched her. She used to wear a cap like that one, and a sort of ridged and ruckled sweater to try to hide how thin she was. His chain mail reminds me of it. She also used to knot a long silk scarf thing round her waist to keep her pants up because she really hadn’t any hips to hang them on to, and the ends of the scarf used to hang down in front in just the way that chap’s seem to do.’

‘I suppose she carried a sword over her shoulder, too,’ I said ironically.

‘No,’ he replied seriously, ‘not a sword, but whenever it was sunny she carried a parasol and used to slant it over her shoulder in just that way. She was partly redheaded, you see, so she burnt to an unbecoming brick-red and then began to peel if she allowed Phoebus Apollo to take any liberties with her complexion. Oh, well, never mind Gloria. Come with me for a drink when you’ve finished with the church. I’ll be somewhere around the grounds. I have a proposition to put to you and I’ve got a pub in Hereford which I think you’ll like.’

‘You’ve got a pub? You’re a Mine Host?’

‘No. I’m on the board of directors of a chain of hotels and the one in Hereford belongs to our group. We have a number of places which are meant to attract tourists, particularly foreign tourists. We have others for commercial travellers and to accommodate coach parties and bodies attending conferences and the Rotary people and all that sort of thing, but, so far as you are concerned, I am not including these. What we want is an updating of our brochures for our top-class tourist hotels. It’s a sort of sub-editing job for you, really. A lot of the information — golf courses, stately homes and castles, old churches and cathedrals, areas of unspoilt natural beauty, facilities for fishing, pony-trekking, access to riding-stables, all that — is already printed in our booklets, but the information is several years out of date. You would have to check all the various items, especially the routes, and make any additions and alterations you thought necessary, bearing in mind that the readers will be on holiday and bent on enjoying themselves in various ways which may or may not be your idea of pleasure.’

‘How long is all this supposed to take? I mean, how many hotels are there and where are they situated?’

‘There is nothing further north than Yorkshire. We’ve got a couple there, one in Norfolk, a couple in Worcestershire, one in Suffolk, one in Dorset, two in Devon, two in Cornwall, two in Sussex, one in Kent and this one in Hereford. You can lump some of them together, I should think. Everybody has a car nowadays and a hundred miles means nothing. We can give you until the end of November to send us the stuff so that the printers can get it out for next season. Oh, a photograph for each brochure would be nice. That’s a pretty good camera you’ve got. You will live free at the hotels, get a generous petrol allowance and a certain amount of credit at the hotel bars and, of course, your pay.’ He told me what this would be and added, ‘I had thought of going up to town this afternoon to ask a newspaper editor I know whether he could put me on to anybody for this job, but I would far rather have you.’

We met again twenty minutes later, when I had examined the rest of the church and he, I suppose, had searched for a headstone to add to his collection. The church was small and, in any case, I was able to purchase two descriptions of it, with some excellent drawings and photographs, when I had been inside the building. Hardie expressed appreciation of the churchyard, but had not been able to add to his gallery of epitaphs.

‘Some of these graves are those of children,’ he said, ‘and that depresses me. Did you get any joy out of your sheila-ma-gig?’

‘I couldn’t even identify her,’ I said. He sighed and then laughed.

‘Damned if I’m sure whether I could identify Gloria herself nowadays,’ he said, ‘and I should class her as the queen of the sheila-ma-gigs.’

‘A rather rude lady?’ I asked, quoting my own words.

‘A damned dangerous one, anyway,’ he said. ‘If you’re ready, let’s go.’

The hotel was all that he had claimed for one of his ‘specials’ and gave me some idea of the kind of work he expected me to do. It was outside the town, had its own golf course of nine holes and the gardens went down in three broad terraces to an immense lawn. Beyond this there was a reed-fringed lake with water-fowl and a smaller pond with water-lilies and goldfish.

The public rooms were high-ceilinged and grand and before lunch he was able to show me a suite of rooms upstairs which the manager told him would not be tenanted until the weekend.

‘Kept for visits from royalty or one of the Arab oil-nabobs,’ McMaster said. Then he asked me how much time I would need to consider his offer.

‘I don’t need any time at all,’ I replied. ‘I’d admire to take it on, as our American cousins used to say.’

‘Oh, that’s good, Corin. When can you start?’ he asked. ‘It will take you quite a bit of time, you know, and we must have the stuff by November.’

‘I can start as soon as ever you like. Is it all right if I get a book out of my experiences? They should be rather productive of copy.’

‘So long as you don’t libel us or any of the hotel residents, go ahead, but bear in mind that at these particular hotels we get VIPs and other sensitive plants. Well, what about some lunch? After that, perhaps you’ll spare time while I give you a fuller briefing and get you to sign on the dotted line, and all that sort of rot.’

Over lunch he told me more about the girl he had called Gloria. I began it because I asked him whether he was married.

‘Lord, yes, for three years now,’ he said. ‘One reason I had to ditch Gloria was that I’d met Kate. Mind you, I was warned against Gloria by Wotton. You remember Wotton, of course. Front-row forward and capable of even more dirty work in the scrum than most front-row forwards, but a nicer fellow off the field you’d never meet. He had had a brief spell with Gloria himself. Met her on a Mediterranean cruise, I believe. My word, those shipping companies will have something to answer for in the great hereafter! Of course he came to his senses when all the boat-deck-by-moonlight stuff was over and they were back in England, but Gloria, I fancy, was very difficult to dislodge.’

‘So he off-loaded her on to you?’

‘Not exactly. She picked me up at a night-club. She soon decided I was a better bet than Wotton. This was before he came into the property, of course. She wasn’t really the type for either of us. I have never seen a girl so thin.’

‘What did you have against her, apart from the lack of robustness in her component parts?’ I asked. ‘Was it because you knew she had had an affair with Wotton?’

‘No, I’m broadminded about that sort of thing. It was over. That was all that mattered. I soon found though, that she was dashed expensive. I wouldn’t have minded that so much, although she was stretching me to the limits of the salary I was getting in those days, but then I found out that she was double-crossing me with an Italian artist fellow and subsidising him out of my money and by selling the jewellery I’d given her. When I remonstrated with her and we had a row, she had the neck to threaten me with breach of promise if I didn’t shut up and continue to play ball. Well, I was pretty sure the case wouldn’t succeed, but I knew that, if she brought it, it would queer my pitch with my father, who had promised to take me into partnership; also there was Kate, so I stalled, and then the artist chap committed suicide, poor devil, and there was a fair amount of stink with Gloria mixed up in it. She disappeared out of my life for a time, and I was thankful.’

‘Only for a time?’

‘Oh, yes. When the suicide became old hat, and things simmered down, she bobbed up again, but by that time I’d got married to Kate. When Gloria knew this, she threatened to write to Kate with details of the night-club pick-up and its aftermath. I told her Kate knew already (although, of course, she didn’t) and I said that if Kate received even one dirty letter I would strangle Gloria. I tracked her down and I went so far as to give her a short demonstration of what I would do to her. That really frightened her off. I think she believed I meant what I said, and I reckon I would have meant it, too, if she had attempted to muck up my marriage.’

‘When we were looking at that church doorway, you told me she was partly a redhead. What did you mean by that?’

‘Oh, apart from her extreme emaciation — although she ate like a starving wolf when I took her out — she had one very unusual feature. She was auburn-haired on one side of her head and coal-black on the other.’

‘Dyed, to create an effect?’

‘No. Before I rumbled that she was playing me up, I used to help her wash her hair. The colours were genuine enough. She told me one of her ancestors had been burnt as a witch and that all the female descendants had had half their hair red and the other half black ever since. I could well believe the witchcraft story. The way Gloria could charm the money out of my pockets was witchcraft enough for me. I nearly went to the money sharks, I was so desperate, but came to my senses and made a clean breast of things to the family lawyer. He subbed up on the strength of my expectations — he had drawn up my father’s will — and I married Kate.’

‘So you haven’t heard from Gloria again?’

‘No, and, until I saw that fellow carved on that doorway, I’ve never even thought of her since I threatened to kill her. Not that I now retain any really hard feelings towards her. The Lord who made the little green apples also made the little gold-diggers, I suppose. I’d like to know why the artist chap committed suicide, though. She must have led him the devil of a dance.’

‘Artists, like women, are kittle cattle,’ I said. ‘There’s no accounting for them.’ We finished lunch, and in the lounge he drafted out a simple form of contract for me to sign and I promised to begin work on the hotel brochures as soon as I had arranged my own affairs. I had booked a room for that night in a hotel at Tewkesbury but, before I went there after I had left him, I decided to pay another visit to Kilpeck church.

The early summer evening was still light enough to allow me to distinguish the figures and carvings on the south door. I stood in front of it and apostrophised the swordbearer in the Phrygian cap.

‘Well, Gloria, old fellow, you’ve done me proud today,’ I said. Of course, the evening was drawing in, so I could not see his features all that well, but I could have sworn that, as I spoke, the Celtic warrior winked at me and grinned.

3

Beeches Lawn

« ^ »

It had been agreed that McMaster would send a complete set of brochures to my home address so that I could be armed and well-prepared, so to speak, for my mission. I decided to accept his tip of lumping some of the hotels together, as it was unlikely that tourists who had spent a week or a fortnight in, for instance, Norfolk, would then go and stay in Suffolk, or that those who had stayed at one of his hotels in Yorkshire would then go and spend time and money in the other.

When I had prepared my way by making notes and studying guidebooks, the month of May was almost at its end, but careful planning convinced me that, with any luck, I could finish the job by the end of October at the latest. I decided to start with Yorkshire, work southwards to Norfolk, Suffolk, Kent and Sussex, then take in Worcestershire and Herefordshire and finish up with Cornwall, Devon and Dorset.

The whole thing took even less time than I had allowed. Some of the brochures needed little alteration, although I made fresh road-plans where there were alternative or new routes, referring for these to the very latest motoring atlas, and I took great trouble to select and photograph what I thought would be an attractive frontispiece for each little book.

I enjoyed the work, was fairly lucky with the weather and by mid-September I was able to send in most of the amended brochures. The hotels at which I had been staying were all much of a muchness, however, in spite of their comfort and luxury, and, after more than three months of them, I was very pleased to receive an invitation to stay for a week with my old friend Anthony Wotton at his ancestral home in the Cotswolds. As for the red-and-black-haired, skeletal Gloria, I had forgotten all about her.

‘I have told Celia about you and she has read one of your novels and is looking forward to meeting you,’ wrote Anthony.

He had been a bachelor when I had heard from him last. I assumed (correctly, as it turned out) that Celia was his wife. I could not imagine him married. However, I need have had no qualms on Anthony’s behalf. Celia was a charming woman of about his own age and she made me welcome as though she was sincerely pleased to see me.

‘I don’t know why you haven’t been here before,’ she said. I explained that I had often visited Anthony at his London flat before old Mr Wotton died and his son inherited the estate, but had never been invited to Beeches Lawn before.

‘No, his father and Anthony didn’t get on,’ she said when she was showing me the room I was to have. ‘Anthony thought he might will this place away from him, but he didn’t, and I think they were reconciled towards the end. Fortunately’ — she smiled — ‘the old gentleman took to me and approved of the marriage.’

‘He could hardly help it,’ I said, looking appreciatively at her. She laughed, told me when to come down for cocktails and left me to unpack, bathe and change. I went to the window, a deep bay which gave good views of the garden and the hills, and looked out. I have always loved the Cotswolds ever since, as a boy, I used to stay with a gamekeeper at Nescomb and learnt country lore from him. He was a wonderful naturalist and could recognise every wild plant that grew. He showed me where the badgers had made their sett under a bank in the woods and where the various birds built their nests. He showed me where there was a fox’s den and where to see the now almost extinct red squirrels before those tree-rats, the grey squirrels, took over. He taught me how to shoot, how to recognise every tree in the woods which surrounded his cottage, how to stack wood for the Cotswold winter, how to cook over a wood fire, and how to make cunning flies for fishing by using the feathers of jays. He showed me a green woodpecker, taught me how to handle ferrets and took me to see a grave he revered. It was not in the churchyard, where he himself is buried, but by the side of a woodland ride along which the young owner of the place, before it was sold to become a public school, loved to ride his horse and where he had asked to be laid so that he could dream he was riding there again. The gamekeeper’s name was Will Smith and he lived in a stone-built cottage about a mile from the village. I think I liked him better than any man I have ever known.

His father had been a gamekeeper before him. They were not Gloucestershire people, but came from Norfolk, and Will never lost that note at the end of a Norfolk sentence which always seems to ask a question. I was reminded of him when I looked out at the hills. Beeches Lawn was just outside Hilcombury, which is not all that far from Nescomb. I thought, as I looked over to the hills, that I would visit Nescomb again, although I knew that, with Will Smith gone, I could never recapture the old magic of his woods and walks, or that of the long lane which led from the stream and the village street up the hill to his cottage, a lane in which the ‘weeds… grow long, lovely and lush’ and the wild flowers proliferate as they please. There was history, too, in that lane. The big, striped, edible snails introduced by the Roman conquerors were still to be found among the weeds and grasses, and the Chedworth villa was not all that far away, and neither were Cirencester and Gloucester.

Meanwhile, my present surroundings were pleasant and peaceful enough. Below me was an immense sweep of lawn. Among trees which, with some bushes between, divided it into two unequal parts, stood an immense lime tree, the largest I have ever seen, and there was a magnificent copper beech at the other end of the garden. Beyond the further part of the lawn, the ground, I thought, might slope down to a little stream, and beyond this again I could see an occasional vehicle making its way along the road to the town.

At the other end of the lawn there were flowerbeds and on my way up to the house, when I had parked my car, I had passed greenhouses, a flourishing kitchen garden and a mighty apple tree laden with fruit. For some reason I have never been able to explain, although the words turned out to be prophetic, I found myself murmuring, as I looked out upon this peaceful and attractive scene:

‘And pleasant is the fairy land

For them that in it dwell,

But aye at end of seven years,

They pay a teind to hell.’

‘Teind’ is a due or a tax, but what, I wondered, had made me think of hell in a place like Beeches Lawn? All I could think of was that the copper beech tree had put the thought of evil into my mind. I would have been about twelve years old, I suppose, when I first came across the Sherlock Holmes stories, and I still think that the twelfth adventure is one of the most spine-tingling tales in the series. That ‘prodigiously stout man with a very smiling face and a great heavy chin which rolled down in fold upon fold’ has always seemed to me a much more sinister and frightening figure than Colonel Lysander Stark or any other of Conan Doyle’s villains.

On the following morning Anthony showed me around. The stables had been converted to garages and the pigsties were empty. I remember he remarked that he was glad to be so near the town as to be virtually part of it, otherwise he might be expected to hunt, ‘and all that sort of time-wasting nonsense, old boy. Anyway, I’m a Londoner and, like the film-star ladies, I am happiest among my books,’ he said, ‘now that I’ve given up rugger.’

His was a curious property in some ways. Within his boundaries were two other dwellings, and these were not estate cottages, but houses in the full sense of the word. One was a beautiful old place which had been the original family dwelling. I, for one, would never have abandoned it. It was stone-built and charming, a typical Cotswold manor house.

‘It’s said to be haunted,’ he told me, ‘but the fact is that it became too small to house my great-great-grandfather’s family, so he let it decay. My great-grandfather had it done up and used to keep a woman there. She was supposed to catalogue the library here and help with the household accounts, but rumour, of course, told a different story. My grandfather left the house to rot, but it’s not in such a bad state as all that. I think I shall do it up again and let it as a couple of holiday flats. I would only need to put another bathroom in and, I suppose, another kitchen, but I’m considering an offer from somebody who is willing to buy it as it stands. The only problem is the staircase, which is in a parlous state and dangerous.’

We retraced our steps, took the path round the lawn to a field, crossed this and came out into a roughly surfaced lane. I noticed that the field boasted a small pavilion.

‘Yes,’ he said, when I mentioned this, ‘a prep school rent the field from me for games. I charge only a peppercorn rent, of course. I like kids and these are very decent little chaps. I have the headmaster to dinner occasionally, so as to maintain the entente cordiale. It works very well. The chap who wants to make me an offer for the old house is this same headmaster. If he comes up with any reasonable figure, I think I shall let him have it. It would save me a lot of trouble and expense as he would do it up to suit himself, because I should sell it as it stands and it would need quite a lot of alteration, I suppose, before I could convert it into flats.’

‘It’s a charming old place,’ I said. ‘What is it like inside?’

‘Coberley — that’s the headmaster — has the only key at present, as I’ve mislaid mine. I’ll get it off him while you’re here and show you round.’

‘Why does he want to buy it?’

‘Goodness knows. I suppose the school is expanding. The kids are mostly day boys, but I believe there are a few boarders.’

‘Won’t it interfere with your privacy to have youngsters passing your windows on their way to the playing field?’

‘They won’t need to do that. They will go out by the way you brought your car in and then walk along the road. You can get to the playing field that way, past this next house I’m going to show you.’

This house was a fair way along a lane. It turned out to be a vast, dark, grim-looking place of which the ground-floor windows were barred. Even the front door with its iron-ended bell-pull looked forbidding. It reminded me of the entrance to a gaol.

‘It doesn’t belong to the estate,’ said Anthony. ‘We sold it a hundred years ago. A colony of craftsmen have it now, but it used to be a convent for nuns.’

‘Poor girls!’ I said, looking at the barred windows and the forbidding exterior of the big, dark house.

‘Not necessarily, Corin. As Wordsworth put it:

‘ “Nuns fret not at their convent’s narrow room,

And hermits are contented with their cells,

And students with their pensive citadels.”

‘I think you and I are enough of like mind to agree with him.’

‘Perhaps,’ I said. ‘Anyway, it’s peaceful enough here. I thought perhaps I might rough out my next book while I’m with you. You’ll be glad for me to be occupied.’ He glanced sideways at me, but said nothing and the bombshell burst early on the following day, the Saturday. There was to be a house-party.

The bad news came when Celia opened her letters and came to the last one.

‘Well, that’s everybody,’ she said. ‘Karen has accepted at her leisure, the rude little beast. She always does leave everything to the last minute. I suppose she hopes something more exciting than a visit to us will turn up. She wants to bring somebody called William Underedge with her.’

‘Who’s he?’ asked Anthony.

‘How should I know? The current boyfriend, I suppose.’

‘Where will you put him?’

‘On a camp bed in one of the attics. It won’t matter where I put him. He’ll sleep with Karen anyway, if I know her.’

‘He may be a sort of young Sir Galahad. You never know who Karen is going to pick up.’

‘If he is, he won’t mind the camp bed and bumping his head on the beams in the attic, so that’s still all right.’

The guests turned up at intervals during the afternoon and by tea-time everybody was with us. The delinquent Karen turned out to be a fresh-looking up-and-coming young miss, not particularly pretty but engaging enough and possessing a certain amount of spontaneous charm, due, I think, to the fact that she took it for granted that everybody she met was going to like her. In so thinking she was probably right. People are apt to take you at your own self-evaluation.

Her escort, whom she had wished upon her hostess at such short notice, was a stocky, swarthy, gravely earnest young man who turned out to be the son of a local mill-owner. I heard him explaining himself apologetically to Celia.

‘If I could have trusted her to drive here without smashing herself up,’ he said, ‘I wouldn’t have pushed in on you, you know. I mean, it seems awful cheek when you don’t even know me.’

‘We soon shall put that right,’ said Celia kindly, ‘and we are very pleased you could come. Have you known Karen long?’

‘Oh, on and off, you know; just on and off. I mean, everybody goes round with a gang these days, don’t they, and she and I are in the same crowd. We sing Bach and five of us play chamber music.’

‘Not — surely not Karen?’

‘Oh, I weaned her off the disco stuff long ago and now she sings Bach and I’m hoping to get her to take lessons on the cello. She’s got the figure for the cello, I think, although, of course, she’ll never look quite like Suggia, I’m afraid.’

I realised that Celia, whose niece Karen was, was looking at the earnest young man with something not far short of awe, and it occurred to me that William Underedge was an incarnation of one of the great fictional creations of the Master of English Prose. I put it to Celia later.

‘The Efficient Baxter personified, wouldn’t you say?’

‘Good heavens, no, Corin! I think William Underedge is perfectly sweet.’

‘Not even efficient?’

‘I just hope he’s efficient enough to make Karen marry him. He would be very good for her, I think. By the way, don’t let my aunt back you into a corner and talk to you about the Malleus Maleficarum. She will, if she gets half a chance.’

There were two extraordinary old ladies in the party. Both had come unescorted and both, I suspected, were quite notably eccentric. This aunt, who was really Celia’s great-aunt, was tall and of intimidating bulk. She wore pince-nez with two gold chains which looped over her ears and dangled safely on to her immense bosom when she discarded the glasses. She spoke in almost a whisper unless she became excited, but then her voice screamed like a particularly indignant seagull or boomed like a bittern heard through an amplifier. This happened chiefly when she was talking on her favourite topic which, as Celia had warned me, was the Malleus Maleficarum of the Dominican priors Heinrich Kramer and James Sprenger, published in the witchhunting days of 1486 AD.

‘Germans, of course,’ Aunt Eglantine belted out across the dinner-table, ‘but, when it comes to sheer thoroughness, there is nobody to beat them.’

Nobody attempted to contest this. I think all shared my hope that, so long as she was permitted to proceed unchecked, in the end she would gallop herself to a standstill. The policy succeeded after a fashion when she had issued what proved to be a final challenge, but it succeeded only with the help of Dame Beatrice, our other old lady.

‘What’s more,’ went on Miss Eglantine Brockworth, warming to her theme, ‘it is high time that somebody wrote another Malleus. Witchcraft is rife in the world of today. The powers of evil gather strength. Even this house is not free from them. Incubi and succubi are all around us and soon they will be in our midst. They have the power to destroy us.’

‘But no operation of witchcraft can have a permanent effect, according to the authorities you have been quoting,’ said Dame Beatrice Lestrange Bradley. ‘I believe the reverend fathers went on to say that a belief that the devil has power to do human bodies any permanent harm does not appear to conform to the teachings of the Church.’

At mention of the Church, everybody gave great attention to the food, and there was the slightly uneasy silence which usually follows the introduction of such a gaffe as to make a reference to religion at any social gathering. That this interval of silence had been brought about deliberately by the reptilian old lady opposite me was manifest the next moment. She looked up, caught my eye, and the ghost of a grin appeared for a fleeting instant on her yellow countenance. At that moment I fell in love with Dame Beatrice Lestrange Bradley.

Celia, as a good hostess, started conversation off again by introducing some innocuous topic — I forget what it was — and we all relaxed. Fortunately Aunt Eglantine (‘my name comes not from Shakespeare, but from Chaucer’) elected to retire early, so we were quit of her and the Malleus Maleficarum for the rest of the evening.

Then there were the other guests. The first two who had arrived were the Coberleys. Cranford Coberley was headmaster of the school which rented Anthony’s field, who might also be considering the purchase of the old house, so I took it that the occasional dinner to which my host had referred had developed, this time, into a weekend stay. As the school was so close at hand, I suppose Coberley thought that he could pop back at any moment if an emergency presented itself or an anxious mum turned up to enquire after the health and happiness of little Johnny, as the staff knew where to contact the headmaster. He struck me as a taciturn, colourless man, but perhaps he was more dynamic when he was in harness. From what I know of small boys, he would need to be.

To my mild astonishment, it appeared that he had yoked himself (her second marriage, I learnt later) to a ravishing beauty. Marigold Coberley, slimmer than the Venus of Milo, more golden than Helen of Troy, was the loveliest girl I had ever seen or ever expect to see. It is not possible for me to describe her, except to say, with Yeats, ‘Oh, that I were young again, and held her in my arms!’

As a matter of fact, I was very much younger than Coberley, but let the quotation stand for what it is worth, namely, ‘the desire of the moth for the star; of the night for the morrow’. My desire for Marigold Coberley was not more lustful than that, but, in any case, I would have shared Yeats’s despairing cry, even though my age, as such, was not against me. Besides, beauty such as hers is intimidating and, to me, sacrosanct. I was content to be the courtier in the palace, not a man who thought he had a claim to the throne.

The other two were an engaged couple and seemed pleasant enough young people, although I had the impression that Roland Thornbury, who was vaguely related to Anthony and had expectations from him if Celia had no children, might turn into a domestic tyrant once he was married to the self-effacing Kay Shortwood. I put this opinion to Celia and Anthony after everybody else had gone to bed. Celia gave a short, expressive, derisive laugh.

‘Don’t you believe it, Corin,’ she said. ‘Roland is safely hooked and she’ll play him with guile until she’s got him just where she wants him. After that, it will be the landing-net and the gaff, and goodbye to Roland except as a meal-ticket. She knows very well that at present Roland is Anthony’s heir. However, I am quite young enough to have children. I don’t particularly want them, but it would be rather fun to see Kay Shortwood’s reactions if she knew there was Roland’s supplanter on the way.’

‘I had no idea you could be so vindictive,’ I said, laughing.

‘Oh, there’s a bitch in every woman,’ she responded, ‘and I particularly dislike that mealy-mouthed little gold-digger. However, Roland always wants to bring her with him and they are engaged to be married, so what can we do?’

‘As we appear to be doing, which is to leave Roland to his fate and to the minding of his own business,’ said Anthony.

‘A Daniel come to judgment!’ she quoted ironically. ‘What do you make of Dame Beatrice, Corin?’

‘I rather wondered why she was here. You two — I speak mostly for Anthony — have never mentioned that you were acquainted with her, yet I understand that she’s a celebrity in her own line.’

‘She got me out of an awful mess in the south of France once. That was before Celia and I were married,’ said Anthony. ‘I was accused of murdering a little girl and Dame Beatrice got the case stopped and told the police who the murderer was. I don’t know how she did it, but she did it all right.’

‘Possibly by “the monstrous power of witchcraft”,’ I suggested, ‘or so Celia’s aunt might say.’

‘Talking of witches,’ said Celia, with a chuckle, ‘wasn’t it clever of Dame Beatrice to match herself against Aunt Eglantine and win?’

‘Anybody could do it, I suppose, provided they had read the Malleus and remembered what they’d read,’ said Anthony.

‘I tried reading it once,’ said Celia, ‘if only to be able to keep up sides with Aunt. However, in Montague Summers’s translation from the Latin there are five hundred and sixty-five closely printed pages, so I didn’t stay the course.’

‘That’s your aunt’s strong suit, of course,’ said Anthony. ‘She trades on the fact that nobody she is acquainted with has read the stuff, so that she can pontificate away to her heart’s content without fear of being challenged. Now that she has come up against somebody who knows the text even better than she does, I expect we shall have a bit of peace until Dame Beatrice goes. Unfortunately she’s got to attend a conference in Cheltenham, so she’ll be leaving us before lunch tomorrow.’

‘I could wish to be better acquainted with her,’ I said.

‘I’m not so sure you’re wise, old boy,’ said Anthony. ‘She’s consultant psychiatrist to the Home Office and has probably already got you sized up as a lad who can bear watching.’

‘The girl who can bear watching, although not in the insulting sense your reference to me suggests, is Mrs Coberley,’ I said indiscreetly. Anthony chipped in at once, and I knew he was not joking.

‘You keep your eyes to yourself, or there’ll be murder done,’ he said. ‘Coberley ain’t as quiet as he looks; and he’s as possessive as the devil where his lily-and-rose is concerned.’

4

Unbidden Guest

« ^ »

I woke early next day and went to the window to see the long shadow of the copper beech lying slantwise across the lawn in the morning sun. Nobody else was stirring when I went downstairs except a housemaid busy in the dining-room. She asked whether I would like my breakfast, but I replied that I would wait until the usual hour, whenever that was.

‘The mistress has hers on a tray, sir, and Sandra mostly puts out the dining-room sideboard at nine, sir.’

I decided to take my car for a short run. It would disturb nobody, as it was parked at a considerable distance from the house. As I walked past the flowerbeds and through the kitchen garden to get to it, I felt an urge to look again at the family’s other house, that which had once been the lodging of Anthony’s great-grandfather’s mistress. Just as I reached it I met Coberley coming from the opposite direction. We exchanged greetings.

‘I wondered whether it was possible to go inside,’ I said, indicating the house.

‘Oh, I’ve got a key,’ he said. ‘I’ve got an option on the place. It would make a storehouse for all the junk my little boys collect. Dear me, what rubbish they do bring in, but children are inveterate collectors. The dangerous objects are already in a wooden box in the old house. I intend to start — ’

‘A school museum?’ I suggested.

‘Call it what you like. I’ve offered to buy the house from Wotton and do it up. By the time the parents have paid for it I shall see that there will be enough money left over to enlarge the pavilion in Wotton’s field.’

‘High finance,’ I commented.

‘Oh, one thing works in with another, and I do well with Common Entrance, so the parents are pleased.’ He produced a key and opened the front door. ‘I wouldn’t try the stairs,’ he said. ‘You could break your neck on them.’

‘So they wouldn’t be safe for Great-aunt Eglantine,’ I said lightly.

‘That old monstrosity will bring trouble on herself if she insists on regaling us with extracts from the Hammer of Evil,’ he said seriously. ‘She doesn’t know what she’s talking about. Those two Dominicans who wrote the Malleus were fair, just and merciful men, considering the times in which they lived. They were also great ecclesiastical lawyers and, I would say, haters of heresy but not of heretics. They genuinely desired to save souls from perdition and only to condemn bodies to those ghastly punishments when everything else had been tried. But that overweight dabbler in the occult is treading on dangerous ground because she is only out for sensationalism and, once you get that bug, you can land up almost anywhere. Those men quite rightly saw witchcraft as the supreme heresy and not only as a religious but as a political danger. She has neither their intellect nor their concern for the human race, but only for her own entertainment and the assertion of her ego. I’m told that in her youth she learnt to toss the caber. No, I don’t believe it, either,’ he said in response to my ejaculation, ‘but I believe that in her day she was a first-class tennis player. I suppose all the muscle has gone to adipose tissue and that she’s taken up this witchcraft stuff to compensate her for losing the plaudits of the crowd.’

‘But there’s nothing in witchcraft,’ I said.

‘Not if you don’t believe in it. All the same, I’ve seen some very strange things in my time. What do you think of the only picture in the place?’ He led the way to a ground-floor room at the back of the house. ‘It belongs to Wotton, of course, but, in any case, I should discard it before I took over the house. It is not an object on which I should desire young boys to speculate.’

The picture hung on a wall opposite the window, so that the light of the emerging day fell full on it. It was the portrait (I guessed that it was a portrait) of a naked girl. She was thin to the point of emaciation, and yet the artist had contrived to give her a sensuousness, almost a voluptuousness, which seemed quite at variance with her meagre, childish body, long thin legs and unformed, skinny arms.

There was nothing in the face, either, of any pretensions to beauty. She was snub-nosed and her eyes were set close together. She had a low forehead and the most striking thing about her was her hair. It fell only to her shoulders, but was of two unimaginably contrasting colours, violently red on the right side of her head, almost coal-black on the other. In one apparently nerveless hand she held a rose between her thumb and first finger. The other hand fell lifelessly down to reach her thigh.

‘Well?’ said Coberley, watching me.

‘She is a witch,’ I said, ‘and the artist was a genius.’

We strolled back to Wotton’s house. I had forgotten my plan to take out my car. I wondered when the portrait had been painted, and whether Celia had ever seen it.

Aunt Eglantine did not appear at breakfast, but everyone else except Celia was there. Dame Beatrice, who took nothing but toast and coffee, sat next to me and proved to have read my biography of Horace Walpole.

‘He was a visitor to a property a few miles from here,’ she said, ‘and recommended it to a friend of his, William Cole. Have you been to Prinknash Abbey?’

‘No. My book concerned itself mostly with his writings after he retired to Strawberry Hill.’

‘You would enjoy Prinknash. The Benedictines have it now, and have built a new and much enlarged abbey. The old building is used as a retreat house, so you can probably get permission to be shown over it, if you are interested. It is a lovely Early Tudor building and the west court is particularly fine. On the outer wall of the east court there is a bas-relief of a young man reputed to be Henry the Eighth.’

‘I shouldn’t think that would find much favour with the monks,’ I said lightly.

‘Oh, the thing would have been sculptured long before the Dissolution. There are connections with Catherine of Aragon. Her badge of a pomegranate surmounted by a crown is to be seen here and there, and on the ceiling of the old chapel, which dates back to the later Middle Ages and has a misericord to every stall, there is the badge of Edward the Fourth, a rose and a falcon.’

At this point a servant came in to say that I was wanted on the telephone. As the only person to whom I had given my address in case there should be any queries about the brochures was McMaster, I guessed correctly that the call must come from him. I took it and went sadly back to the dining-room to tell Wotton that I had to leave forthwith.

‘I promised to place myself at McMaster’s disposal,’ I said apologetically, ‘so I’m afraid I shall have to go and see him.’

‘Oh, but why? Couldn’t you suggest meeting him here? I would like to see the old buster again. We used to play in the college fifteen, if you remember. Do ask him to come. Is he married?’

‘Yes, to somebody called Kate,’ I replied.

‘Well, tell him to bring the girl along. We have plenty of room now that Dame Beatrice has to leave us.’

I had discovered that Celia had repented of putting the earnest young Underedge on a camp bed in one of the attics. (In fact, I doubted whether that had ever been her serious intention.) ‘Roland and Kay are leaving after lunch, too.’ Anthony added.

Except for Wotton himself, the dining-room was empty when I came back from the telephone for the second time.

‘Grateful thanks from McMaster,’ I said. ‘Kate’s decided not to come. He hates leaving her, but won’t be here long. He thinks he and I can be through in about an hour.’

‘Oh, good. It would have been a great pity to lose you so soon after your arrival,’ said Anthony.

‘Thanks very much.’

‘You’ve made a big hit with Celia. She has never met a real live author before. I noticed you seemed to be getting on extremely well with Dame Beatrice, too. A pity you had to say goodbye to her so soon.’

‘She was telling me I ought to visit Prinknash Abbey.’

‘Oh, yes, you must do that. Apart from a lovely old house which used to be the monastery before they needed more room, the setting is quite supremely beautiful. The place lies in a valley surrounded by wooded hills. You can’t imagine a more delightful spot. I’m glad Dame Beatrice mentioned it.’

‘Does one ask any sort of permission to go and see the place?’

‘Oh, no. The grounds are open to the public. I don’t know whether you could be shown over the house, but at least you could look at the outside of it. It really is a picture.’

‘Talking of pictures,’ I said, ‘Coberley showed me the one in your other house.’

‘That’s the lady my great-grandfather kept there,’ he said. ‘She was reputed to have been a witch. I don’t have the picture in this house because it’s supposed to be unlucky. I’d get rid of it if it weren’t such a marvellous bit of painting.’

‘Strangely enough, McMaster described it to me,’ I said.

‘McMaster? He couldn’t have done. He’s never seen it. Of course, though! You mean he described Gloria Mundy to you.’

I could feel that there was tension in the air, so, to relieve it, this time it was I who changed the subject. I asked a question which it would have been impossible to put in the presence of the old lady herself.

‘You told me how you came to be acquainted with Dame Beatrice, but what was she doing here? I shouldn’t have thought psychiatry was much in your line. Was she here on the same terms as the rest of us, merely as a guest?’

‘It was Celia’s idea. She thinks — and with some justification — that poor old Aunt Eglantine is going off her rocker, so Dame Beatrice came to take a look at her and to advise us whether treatment is necessary.’

‘How is Aunt Eglantine going to respond, if Dame Beatrice does think it’s necessary?’

‘I don’t know what the outcome will be. Dame Beatrice will send us a report.’

McMaster was to join us after lunch, so, accepting Wotton’s offer to put a writing-desk in my room, I watched the four young people go off for a Sunday morning drive in Roland Thornbury’s car and then went upstairs to go through my notes for McMaster’s brochures so that I should be prepared for his arrival.

The desk Wotton had given me faced the window, so that every time Ï looked up I had a view of the lawn, the trees and the hills. There was not a great deal to go through in my notes, and at about eleven a servant came in with coffee, a flask of whisky and some biscuits. I had disposed of the coffee and biscuits, and was relaxing and wondering what queries McMaster might have to put to me concerning the brochures, when I saw a girl approaching the house. She was dressed in jeans and a sweater and was carrying a small suitcase. She was a stranger to me until I realised that I had seen, not herself, but a portrait of her. Allowing for the fact that she was clad, whereas the picture I had seen was that of a nude, she bore an uncanny resemblance to the picture of the girl in the old house. What clinched it was her hair. As she approached my window she had pulled off the woollen cap she was wearing and her hair, which had been tucked up under it, fell to her shoulders. Half of it was a fiery red, the rest of it was black.

She passed in front of my window, but very shortly she was back again. I was standing up by this time and she must have seen me, for she called out, ‘Hi, there! Come and let me in.’

The window was open at the top. I pushed it up from the bottom and leant out.

‘Ring the bell,’ I advised her. ‘I can’t let you in. I’m a visitor here.’

‘This is Tony’s pad, isn’t it?’

‘It belongs to Mr Wotton.’

‘Well, that’s Tony. I’m his cousin Gloria.’

‘The front door is round the corner. You must have passed it just now,’ I told her. She made a very rude gesture, walked on, and I heard the doorbell ring.

The four young ones had returned from their drive. Aunt Eglantine, who had taken affectionate leave of Dame Beatrice, was looking smug. Dame Beatrice, with the expression of a satisfied snake, had been escorted to her car, Celia, at the foot of the table, was looking pensive, Anthony, at its head, appeared gloomy and the newcomer, seated opposite Aunt Eglantine, was glancing brightly round at the company.

Anthony had introduced her to us as Miss Gloria Mundy, but made no mention of relationship. When it was my turn to greet her I had said that coincidence was a very strange thing.

‘Another friend of mine knows you,’ I said, ‘a man named McMaster. He mentioned you only a few weeks ago.’

‘Oh, dear old Hardie,’ she said. ‘We had great times together. He was tremendous fun.’

‘He’s coming here after lunch,’ said Celia. ‘You’ll be able to talk over old times, as perhaps you had hoped to do with Anthony.’

‘He is coming on business,’ said Anthony. ‘The person he will want to talk to is Corin.’

‘He will want to talk to me,’ said Gloria. She continued to look brightly but, I thought, challengingly around her at the others seated at table. Soup had been served, and she sat there opposite Aunt Eglantine, her soup spoon poised. She waved it. ‘What a bevy of beauties you have assembled, Tony darling,’ she said, looking straight at Marigold Coberley, ‘I wonder how you dare collect young, pretty girls around you now you are a married man. It was different in the old days, wasn’t it? My word! You stepped high and handsome then, you sporty boy, didn’t you? Don’t tell me the old Adam is coming out again. ’

It was Aunt Eglantine who made what I thought was the adequate response to this. She picked up a flat, soft bread-roll and lobbed it neatly and accurately into Gloria’s well-filled plate of soup.

‘Well, her ancient skills have not deserted her,’ said Celia, referring to the incident. ‘Appalling though it was of Aunt, and providing as it did visible proof that we had good reason for having Dame Beatrice take a look at her, it nearly killed me not to laugh.’

‘Dame Beatrice would have remained unmoved,’ I said.

‘I expect she is accustomed to eccentric patients. I thought Cranford Coberley looked distressed. I expect he was glad none of his boys was present to have such a bad example set them.’ Celia seemed to hesitate for a moment and then, presumably because there was no one in the room except ourselves — for McMaster had arrived and Anthony was showing him over the estate before Hardie and I settled down with the brochures — out she came with it.

‘Corin! That awful girl! Whatever could Anthony have seen in her? And why on earth should she come here? He finished with her years ago.’

‘Oh, I expect she found herself in the neighbourhood and thought she would look the two of you up.’

Celia was not pleased. She asked angrily, ‘Oh, why do men always try to cover up for one another?’

‘To oppose the monstrous regiment of women. Besides, aren’t women — don’t women — do the same?’ I asked.

‘Sometimes, I suppose, sometimes not. Well, I’m not always grateful to Aunt Eglantine, but I’m thankful to her for finding a way of getting rid of Gloria Mundy.’

‘Yes, the soup did splash about a bit, didn’t it? I wonder why there is always three times as much liquid when it’s spilt than when it is in the bowl.’

‘One of Parkinson’s Laws, isn’t it? I’ll tell you one thing, Corin. That girl is up to mischief of some sort.’

‘What sort?’

‘If I knew that, I’d know what to do about it. I wish Marigold Coberley hadn’t laughed when the soup went all over Gloria. Did you see the look she got while we were all mopping Gloria up?’

‘I wonder why that staggeringly beautiful young woman married a stick-in-the-mud like Coberley?’

‘Thereby hangs a tale, but it’s not my story. You must ask Anthony.’

Anthony, coming into the room, said firmly, ‘As I tried to tell you, he’s a ravening lion where she’s concerned. He risked a lot to marry her, you know. She stood trial for killing her former husband and only got off by the skin of her teeth. Surely you remember the case, Corin? Her name then was Maria Pinzón Campville. Coberley was called as a prosecution witness (most unwillingly, of course) and he married her as soon as the case was over. He threw up a lucrative job and bought the school just to get her away from all the publicity. He told me the story last Christmas when I’d got him nicely sozzled, but it’s old hat now.’

‘And did she do it?’ I asked. ‘Kill her husband, I mean?’

‘Quíen sabe? There were nine men on the jury, and you know how beautiful she is.’

‘At least one of the three women must have voted for an acquittal, though,’ I said, ‘and probably carried the other two with her. There are always women who think a man deserves everything he gets, so perhaps these ladies of the jury approved of the murder. The war between the sexes waxes fiercely in these days of women’s emancipation and the competition for top jobs, I suppose.’

‘I’ve got a bone to pick with you,’ said Hara-kiri after we had gone through my notes and alterations.

‘With me? But you said you liked what I’d done with the brochures.’

‘I’m not talking about the brochures. Do you remember my mentioning Gloria Mundy when we last met?’

‘Yes, of course I remember.’

‘And I gave you an impression of what I thought of her?’

‘Unfavourable, on the whole, as I remember it.’

‘Well, I think you might have told me she was staying in the house when you relayed old Anthony’s invitation.’

‘But she isn’t staying here. She breezed in all unexpectedly and had to be asked to stay for lunch. You were probably on your way here by the time she turned up, so I couldn’t have let you know, even if I had thought of it. Anyway, there is no question of her staying here. She didn’t even stay long enough to finish her lunch. One of the other guests splashed soup all over her, so she upped and went.’

‘I spotted her in the kitchen garden after I had left my car.’

‘Well, she won’t be coming back, that’s for sure.’

‘You never know. I hope you’re right, that’s all. How long are you staying here?’

‘Only until Thursday. Don’t worry. I shall be on to the rest of the brochures in just a day or so.’

‘That is not what I meant. How did Wotton react when Gloria showed up?’

‘I wasn’t present at their meeting. I was up here.’

‘I wonder what she was after?’

‘Wanted a free lunch, perhaps,’ I said. ‘I don’t think she looks any more robust than when you knew her. Did you see her again while you were in the grounds with Wotton?’

‘No. She can’t have been up to any good coming here, Corin. Was there a hint of Auld Lang Syne, would you say?’

‘Honestly, Hardie, I have no idea.’

‘Up to no good at all,’ he said thoughtfully. ‘As for me, I’m going to sprinkle salt all round my bed tonight.’

‘Don’t tell me you’re as superstitious as that!’ I said.

He scowled at me, ‘That damn girl spells trouble. You mark my words,’ he muttered angrily. ‘I cut and ran as soon as I spotted that red and black hair above the bushes. I only saw the top of her head, but nobody can mistake her.’

5

Chapter of Accidents

« ^ »

I had no idea what time it was when Roland and Kay left the house. McMaster and I were still upstairs, working on the brochures. The front door was round a corner and so out of sight of my window, but, in any case, I had no time to look out of it. McMaster had wanted one or two additions to the brochures and there was enough to do to keep us busy until almost teatime.

It had been getting darker all the afternoon, so, by the time we went downstairs, I had had the electric light on for the past hour. The full force of the storm struck the house just as we reached the hall.

We heard afterwards that it was the worst storm for ten years. The sky blackened, the windows rattled, doors thought to be shut flew open, the wind shrieked and tore at the trees and bushes, and then the rain came down and deluged the paths and the lawn.

I have never experienced such rain. It blotted out everything as though the house were surrounded by thick fog. The others all fled to their rooms to make certain that the windows were closed, while Anthony, Celia and the servants made the rest of the rounds. A skylight which had been left open was allowing a spate of water to cascade down the back stairs and for more than five minutes it resisted all attempts to close it.

The cook reported that water was coming in under the back door and part of the guttering gave up the struggle, so that water fell in fountains down one of the outside walls.

‘You shouldn’t have let that witch-girl in,’ pronounced Aunt Eglantine, during the first lull in the storm before its devils’ chorus broke out again. ‘She’s doing all this.’

‘You shouldn’t have chucked your bread into her soup,’ said William Underedge severely. ‘I’m afraid you are a very naughty old lady.“

‘Karen laughed when I did it.’

‘No, I didn’t,’ said Karen. ‘I wouldn’t have thought of laughing. I detest hearty humour. It was Mrs Coberley who laughed.’

‘People laugh from shock mostly,’ said McMaster. ‘Isn’t that so?’

Before anybody could answer, the doorbell pealed and pealed.

‘That’s witchcraft, too,’ said Aunt Eglantine. ‘They always do that when they want to annoy people.’

A maidservant, her cap askew and her shoes soaking wet, announced the return of Kay and Roland. They had decided to take to the byroads, had come to a watersplash which the rain had swollen into a torrent and got their car waterlogged in mid-stream. To complete the disaster, the wind had flung a big branch at them and it had smashed the windscreen.

‘We had to abandon the car and get to a garage,’ said Roland. ‘They won’t touch the job until the water ebbs away, so we hired from them and they brought us back. We’re soaking.’

As this hardly needed saying, Celia sent them off to get a hot bath and she and Anthony lent them clothes, as all their luggage had been left in the boot of their car.

‘I’m very grateful for your offer of a bed for the night,’ said McMaster, when the two drowned rats had gone upstairs, ‘but I think I ought to be off as soon as the storm gives over.’

‘Oh, why?’ asked Celia.

‘Because you’ve offered me Miss Shortwood’s room, and now she’ll be needing it herself.’

‘That’s all right. Kay could have shared with Karen just for one night, but Dame Beatrice has gone, so her room is available. Do stay. But, anyway, it would have been quite easy.’

Kay came downstairs again before Roland reappeared. Over tea, at which the Coberleys were not present as they had been called back to the school before the storm broke, she asked casually, ‘I thought, didn’t I, that Miss Mundy had left? Didn’t she go after the soup incident at lunch? She said she was going, I thought.’

‘Oh, she did go,’ said Celia, without glancing at Aunt Eglantine, who was wiping buttery fingers down the front of a black velvet gown. ‘Yes, she went off in a white-hot rage and I didn’t suggest she should stay.’

‘Witches are gate-crashers,’ said Aunt Eglantine. ‘Nobody wants them. They just invite themselves.’

‘What do you mean about Gloria?’ said Anthony to Kay. ‘Of course she went, and no wonder.’

‘Then I think you may take it that she has come back,’ said Roland, who had just entered the room. ‘Tea? Oh, I say, jolly good!’ He seated himself. ‘She’s in the old house. We saw her at the window.’

‘But she couldn’t get in. Coberley has the only key,’ said Anthony.

‘Witches can get in anywhere,’ said Aunt Eglantine.

‘Well, she can’t sleep there. There is no bed and no heating,’ said Celia. ‘As soon as the rain eases off, somebody had better go and bring her back here. I shall have to find somewhere to bed her down, that’s all.’

‘No. I shall take her to a hotel,’ said Anthony. ‘She is not going to make a nuisance of herself here.’

‘You’ll do nothing of the sort,’ said McMaster. ‘Kate will expect me. I am very grateful, as I said, for your offer of a bed for tonight but, as the weather already seems to be easing off, there is no reason why you should put me up. I’ll be the one to go.’

‘To make room for Gloria? Perish the thought!’ said Anthony.

‘No, really, you mustn’t go,’ said Celia. ‘Anthony can telephone the hotel and a taxi can take the wretched woman there. They know us. We often go there on Saturday evenings to dine and dance. They will take her in and Anthony can settle the bill later. It’s worth it to make sure that she doesn’t come back here. You ring up your wife and tell her you’re staying, and then after dinner we’ll all settle down and have a cosy time. I’m sure you three old college friends will like to get together and talk over old times in Anthony’s den, and I expect the rest of us can amuse ourselves without you. The rain may ease off, but there is bound to be flooding. We don’t want you bogged down like Roland and Kay.’

‘They should have stuck to the main roads, of course,’ said William Underedge.

‘Thanks for the hindsight,’ said Roland Thornbury angrily.

‘Now, now!’ said Karen. ‘Boys must not be boys in mixed company.’ The maid came in to clear away the tea things, and the various parties dispersed to their rooms except for Anthony and Celia. As I, the last to leave, was passing through the doorway into the hall, I heard him say, ‘The storm has upset people. Well, I had better see about Gloria, I suppose.’

‘I’m sure Roland and Kay are mistaken,’ I said, turning round. ‘Coberley let me into the old house this morning. She couldn’t possibly have got in without the key.’

‘Then I had better ring up the school and find out whether Coberley lent it to her,’ said Anthony. ‘It was not right of him if he did. The house is not yet his property.’

‘Do you mind that he took me in there this morning?’

‘My dear chap, of course not. It is one thing for him to take somebody in with him; quite another for him to lend the key to somebody else, particularly to somebody who turned up out of the blue and wished herself on us the way Gloria did.’

‘I thought you might have been glad to see her,’ said Celia. ‘She must have been pretty sure of her welcome to have chanced her arm like that.’

‘What do you mean? I hate the sight of her.’

I closed the door behind me and left them to it. At the top of the stairs I met McMaster with a towel over his arm.

‘Thank God for what Rupert Brooke called “the benison of hot water”,’ he said. ‘What’s happening about our precious Gloria? I hope those two made a mistake and she isn’t still on the premises.’

‘Anthony is going over to find out.’ I was tempted to tell him that Gloria, however involuntarily, had already managed to create friction between husband and wife, but I thought better of it. It was no business of mine, anyway.

When I went downstairs again, I realised that outwardly Anthony and Celia had patched up their differences. Aunt Eglantine had opted for a tray in her room instead of joining us at table, so the company was depleted in numbers, for the Coberleys had decided to remain at the school.

Anthony had been over to the old house and reported that one of the back windows was smashed and that the portrait which Coberley had shown me had disappeared. He supposed that Gloria had broken in and stolen it. He added, without looking at Celia, that he was not sorry it had gone. Gloria had gone, too. However doubtful Anthony had been about the information which Roland and Kay had given him, the disappearance of the picture, together with the broken window (a feature Coberley would have noticed and commented upon when he had shown me over the house) bore out what Roland had said.

Anthony had hammered on the front door, received no answer, and had then gone round to the back and knocked and shouted. There had been no response, so he had climbed in and found the place empty and the picture gone. This he confided only to Celia and myself while we were having cocktails before dinner.

When dinner was over, the four young people played Scrabble for a bit, but soon drifted off to bed. Aunt Eglantine, who had come down after dinner and had been communing either with herself or with the spirits of Kramer and Sprenger, also gave us little of her company. Celia went off to the ground-floor room she had allocated to her own use, and Anthony, McMaster and I settled down in Anthony’s den on the first floor and, with the assistance of his whisky, relived our youth by adopting Celia’s suggestion and talking over old times.

We broke up at well past midnight. Mopping-up operations seemed to have been completed and the house, except for a faint sound of water dripping from a leaky guttering somewhere, was almost eerily silent.