Half of winning a battle is showmanship.

The pink point grew up fast and shed light on the river. There must have been forty boats sneaking towards us. They had extended their croc hide protection in hopes of shedding fire bombs.

I was glowing and breathing fire. Bet I made a hell of a sight from over there.

The nearest boats were ten feet away. I saw the ladder boxes and grinned behind my croc teeth. I had guessed right.

I threw my hands up, then down. A single bomb arced out to shatter the nearest boat.

The trap was almost too good. Fire sucked most of the air away and heated what was left till it was almost unbearable. The survivors had no stomach left for combat. That was the first wave, a distant rattle announced the second wave. I was laying for these guys, too.

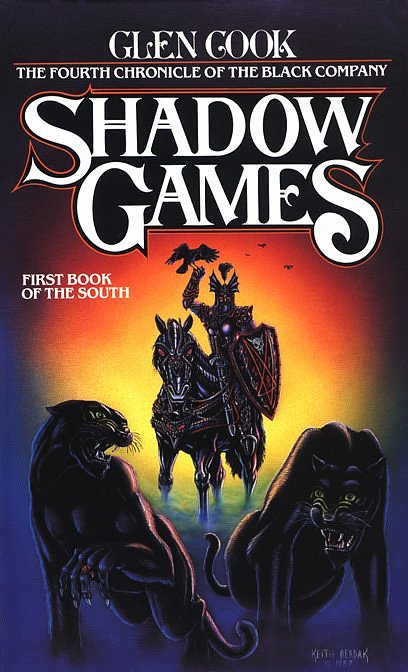

Glen Cook

Shadow Games

Got to be for Harriet McDougal whose gentle hands guided Croaker and the Company out of the darkness With Special Thanks to Lee Childs of North Hollywood, for historical research and valued suggestions

Chapter One

The crossroads

We seven remained at the crossroads, watching the dust from the eastern way. Even irrepressible One-Eye and Goblin were stricken by the finality of the hour. Otto’s horse whickered. He closed her nostrils with one hand, patted her neck with the other, quieting her. It was a time for contemplation, the final emotional milemark of an era.

Then there was no more dust. They were gone. Birds began to sing, so still did we remain. I took an old notebook from my saddlebag, settled in the road. In a shaky hand I wrote: The end has come. The parting is done. Silent, Darling, and the Torque brothers have taken the road to Lords. The Black Company is no more.

Yet I will continue to keep the Annals, if only because a habit of twenty-five years is so hard to break. And, who knows? Those to whom I am obliged to carry them may find the account interesting. The heart is stilled but the corpse stumbles on. The Company is dead in fact but not in name.

And we, O merciless gods, stand witness to the power of names.

I replaced the book in my saddlebag. “Well, that’s that.” I swatted the dust off the back of my lap, peered down our own road into tomorrow. A low line of greening hills formed a fencerow over which sheeplike tufts began to bound. “The quest begins. We have time to cover the first dozen miles.”

That would leave only seven or eight thousand more.

I surveyed my companions.

One-Eye was the oldest by a century, a wizard, wrinkled and black as a dusty prune. He wore an eyepatch and a floppy, battered black felt hat. That hat seemed to suffer every conceivable misfortune, yet survived every indignity.

Likewise Otto, a very ordinary man. He had been wounded a hundred times and had survived. He almost believed himself favored of the gods.

Otto’s sidekick was Hagop, another man with no special color. But another survivor. My glance surprised a tear.

Then there was Goblin. What is there to say of Goblin? The name says it all, and yet nothing? He was another wizard, small, feisty, forever at odds with One-Eye, without whose enmity he would curl up and die. He was the inventor of the frog-faced grin.

We five have been together twenty-some years. We have grown old together. Perhaps we know one another too well. We form limbs of a dying organism. Last of a mighty, magnificent, storied line. I fear we, who look more like bandits than the best soldiers in the world, denigrate the memory of the Black Company.

Two more. Murgen, whom One-Eye sometimes calls Pup, was twenty-eight. The youngest. He joined the Company after our defection from the empire. He was a quiet man of many sorrows, unspoken, with no one and nothing but the Company to call his own, yet an outside and lonely man even here.

As are we all. As are we all.

Lastly, there was Lady, who used to be the Lady. Lost Lady, beautiful Lady, my fantasy, my terror, more silent than Murgen, but from a different cause: despair. Once she had it all. She gave it up. Now she has nothing.

Nothing she knows to be of value.

That dust on the Lords road was gone, scattered by a chilly breeze. Some of my beloved had departed my life forever.

No sense staying around. “Cinch them up,” I said, and set an example. I tested the ties on the pack animals. “Mount up. One-Eye, you take the point.”

Finally, a hint of spirit as Goblin carped, “I have to eat his dust?” If One-Eye had point that meant Goblin had rearguard. As wizards they were no mountain movers, but they were useful. One fore and one aft left me feeling far more comfortable.

“About his turn, don’t you think?”

“Things like that don’t deserve a turn,” Goblin said. He tried to giggle but only managed a smile that was a ghost of his usual toadlike grin.

One-Eye’s answering glower was not much pumpkin, either. He rode out without comment.

Murgen followed fifty yards behind, a twelve-foot lance rigidly upright. Once that lance had flaunted our standard. Now it trailed four feet of tattered black cloth. The symbolism lay on several levels.

We knew who we were. It was best that others did not. The Company had too many enemies.

Hagop and Otto followed Murgen, leading pack animals. Then came Lady and I, also with tethers behind. Goblin trailed us by seventy yards. And thus we always traveled for we were at war with the world. Or maybe it was the other way around.

I might have wished for outriders and scouts, but there was a limit to what seven could accomplish. Two wizards were the next best thing.

We bristled with weaponry. I hoped we looked as easy as a hedgehog does to a fox.

The eastbound road dropped out of sight. I was the only one to look back in hopes Silent had found a vacancy in his heart. But that was a vain fantasy. And I knew it.

In emotional terms we had parted ways with Silent and Darling months ago, on the blood-sodden, hate-drenched battleground of the Barrowland.

A world was saved there, and so much else lost. We will live put our lives wondering about the cost.

Different hearts, different roads.

“Looks like rain, Croaker,” Lady said.

Her remark startled me. Not that what she said was not true. It did look like rain. But it was the first observation she had volunteered since that dire day in the north.

Maybe she was going to come around.

Chapter Two

The road south

“The farther we come, the more it looks like spring,” One-Eye observed. He was in a good mood.

I caught the occasional glint of mischief brewing in Goblin’s eyes too, lately. Before long those two would find some excuse to revive their ancient feud. The magical sparks would fly. If nothing else, the rest of us would be entertained.

Even Lady’s mood improved, though she spoke little more than before.

“Break’s over,” I said. “Otto, kill the fire. Goblin. Your point.” I stared down the road. Another two weeks and we would be near Charm. I had not yet revealed what we had to do there.

I noticed buzzards circling. Something dead ahead, near the road.

I do not like omens. They make me uncomfortable. Those birds made me uncomfortable.

I gestured. Goblin nodded. “I’ll go now,” he said. “Stretch it out a bit.”

“Right.”

Murgen gave him an extra fifty yards. Otto and Hagop gave Murgen additional room. But One-Eye kept pressing up behind Lady and I, rising in his stirrups, trying to keep an eye on Goblin. “Got a bad feeling about that, Croaker,” he said. “A bad feeling.”

Though Goblin raised no alarm, One-Eye was right. Those doombirds did mark a bad thing.

A fancy coach lay overturned beside the road. Two of its team of four had been killed in the traces, probably because of injuries. Two animals were missing.

Around the coach lay the bodies of six uniformed guards and the driver, and that of one riding horse. Within the coach were a man, a woman, and two small children. All murdered.

“Hagop,” I said, “see what you can read from the signs. Lady. Do you know these people? Do you recognize their crest?” I indicated fancywork on the coach door.

“The Falcon of Rail. Proconsul of the empire. But he isn’t one of those. He’s older, and fat. They might be family.”

Hagop told us, “They were headed north. The brigands overtook them.” He held up a scrap of dirty cloth. “They didn’t get off easy themselves.” When I did not respond he drew my attention to the scrap.

“Grey boys,” I mused. Grey boys were imperial troops of the northern armies. “Bit out of their territory.”

“Deserters,” Lady said. “The dissolution has begun.”

“Likely.” I frowned. I had hoped decay would hold off till we got a running start.

Lady mused, “Three months ago travelling the empire was safe for a virgin alone.”

She exaggerated. But not much. Before the struggle in the Barrowland consumed them, great powers called the Taken watched over the provinces and requited unlicensed wickedness swiftly and ferociously. Still, in any land or time, there are those brave or fool enough to test the limits, and others eager to follow their example. That process was accelerating in an empire bereft of its cementing horrors.

I hoped their passing had not yet become a general suspicion. My plans depended on the assumption of old guises.

“Shall we start digging?” Otto asked.

“In a minute,” I said. “How long ago did it happen, Hagop?”

“Couple of hours.”

“And nobody’s been along?”

“Oh, yeah. But they just went around.”

“Must be a nice bunch of bandits,” One-Eye mused. “If they can get away with leaving bodies laying around.”

“Maybe they’re supposed to be seen,” I said. “Could be they’re trying to carve out their own barony.”

“Likely,” Lady said. “Ride carefully, Croaker.”

I raised an eyebrow.

“I don’t want to lose you.”

One-Eye cackled. I reddened. But it was good to see some life in her.

We buried the bodies but left the coach. Civilized obligation fulfilled, we resumed our journey.

Two hours later Goblin came riding back. Murgen stationed himself where he could be seen on a curve. We were in a forest now, but the road was in good repair, with the woods cleared back from its sides. It was a road upgraded for military traffic.

Goblin said, “There’s an inn up ahead. I don’t like its feel.”

Night would be along soon. We had spent the afternoon planting the dead. “It look alive?” The countryside had gotten strange after the burying. We met no one on the road. The farms near the woods were abandoned.

“Teeming. Twenty people in the inn. Five more in the stables. Thirty horses. Another twenty people out in the woods. Forty more horses penned there. A lot of other livestock, too.”

The implications seemed obvious enough. Pass by, or meet trouble head-on?

The debate was brisk. Otto and Hagop said straight in. We had One-Eye and Goblin if it got hairy.

One-Eye and Goblin did not like being put on the spot.

I demanded an advisory vote. Murgen and Lady abstained. Otto and Hagop were for stopping. One-Eye and Goblin eyeballed one another, each waiting for the other to jump so he could come down on the opposite side.

“We go straight at it, then,” I said. “These clowns are going to split but still make a majority for...” Whereupon the wizards ganged up and voted to jump in just to make a liar out of me.

Three minutes later I caught my first glimpse of the ramshackle inn. A hardcase stood in the doorway, studying Goblin. Another sat in a rickety chair, tilted against the wall, chewing a stick or piece of straw. The man in the doorway withdrew.

Grey boys Hagop had called the bandits whose handiwork we encountered on the road. But grey was the color of uniforms in the territories whence we came. In Forsberger, the most common language in the northern forces, I asked the man in the chair, “Place open for business?”

“Yeah.” Chair-sitter’s eyes narrowed. He wondered.

“One-Eye. Otto. Hagop. See to the animals.” Softly, I asked, “You catching anything, Goblin?”

“Somebody just went out the back. They’re on their feet inside. But it don’t look like trouble right away.”

Chair-sitter did not like us whispering. “How long you reckon on staying?” he asked. I noted a tatoo on one wrist, another giveaway betraying him as an immigrant from the north.

“Just tonight.”

“We’re crowded, but we’ll fit you in somehow.” He was a cool one.

Trapdoor spiders, these deserters. The inn was their base, the place where they marked out their victims. But they did their dirt on the road.

Silence reigned inside the inn. We examined the men there as we entered, and a few women who looked badly used. They did not ring true. Wayside inns usually are family-run establishments, infested with kids and old folks and all the oddities in between. None of those were evident. Just hard men and bad women.

There was a large table available near the kitchen door. I seated myself with my back to a wall. Lady plopped down beside me. I sensed her anger. She was not accustomed to being looked at the way these men were looking at her.

She remained beautiful despite road dirt and rags.

I rested a hand upon one of hers, a gesture of restraint rather than of possession.

A plump girl of sixteen with haunted bovine eyes came to ask how many we were, our needs in food and quarters, whether bath water should be heated, how long we meant to tarry, what was the color of our coin. She did it listlessly but right, as though beyond hope, filled only with dread of the cost of doing it wrong.

I intuited her as belonging to the family who rightfully operated the inn.

I tossed her a gold piece. We had plenty, having looted certain imperial treasures before departing the Barrow-land. The flicker of the spinning coin sparked a sudden glitter in the eyes of men pretending not to be watching.

One-Eye and the others clumped in, dragged up chairs. The little black man whispered, “There’s a big stir out in the woods. They have plans for us.” A froggish grin yanked at the left corner of his mouth. I gathered he might have plans of his own. He likes to let the bad guys ambush themselves.

“There’s plans and plans,” I said. “If they are bandits, we’ll let them hang themselves.”

He wanted to know what I meant. My schemes sometimes got more nasty than his. That is because I lose my sense of humor and just go for maximum dirt.

We rose before dawn. One-Eye and Goblin used a favorite spell to put everyone in the inn into a deep sleep.

Then they slipped out to repeat their performance in the woods. The rest of us readied our animals and gear. I had a small skirmish with Lady. She wanted me to do something for the women kept captive by the brigands.

“If I try to right every wrong I run into, I’ll never get to Khatovar.”

She did not respond. We rode out minutes later.

One-Eye said we were near the end of the forest. “This looks as good a place as any,” I said. Murgen, Lady, and I turned into the woods west of the road. Hagop, Otto, and Goblin turned east. One-Eye just turned around and waited.

He was doing nothing apparent. Goblin was busy, too.

“What if they don’t come?” Murgen asked.

“Then we guessed wrong. They’re not bandits. I’ll send them an apology on the wind.”

Nothing got said for a while. When next I moved forward to check the road One-Eye was no longer alone. A half-dozen horsemen backed him. My heart twisted. His phantoms were all men I had known, old comrades, long dead.

I retreated, more shaken than I had expected. My emotional state did not improve. Sunlight dropped through the forest canopy to dapple the doubles of more dead friends. They waited with shields and weapons ready, silently, as befit ghosts.

They were not ghosts, really, except in my mind. They were illusions crafted by One-Eye. Across the road Goblin was raising his own shadow legion.

Given time to work, those two were quite the artists.

There was no doubt, now, even who Lady was.

“Hoofbeats,” I said, needlessly. “They’re coming.”

My stomach turned over. Had I bet to an inside straight? Taken too long a shot? If they chose to fight... If Goblin or One-Eye faltered...

“Too late for debate, Croaker.”

I looked at Lady, a glowing memory of what she had been. She was smiling. She knew my mind. How many times had she been there herself, albeit on a grander game board?

The brigands pounded down the aisle formed by the road. And reined in in confusion when they saw One-Eye awaiting them.

I started forward. All through the woods ghost horses moved with me. There was harness noise, brush noise. Nice touch, One-Eye. What you call verisimilitude.

There were twenty-five bandits. They wore ghastly expressions. Their faces went paler still when they spied Lady, when they saw the specter-banner on Murgen’s lance.

The Black Company was pretty well known.

Two hundred ghost bows bent. Fifty hands tried to find some sky-belly to grab. “I suggest you dismount and disarm,” I told their captain. He gulped air a few times, considered the odds, did as directed. “Now clear away from the horses. You naughty boys.”

They moved. Lady made a gesture. The horses all turned and trotted toward Goblin, who was their real motivator. He let the animals pass. They would return to the inn, to proclaim the terror ended.

Slick. Oh, slick. Not even a hangnail. That was the way we did it in the old days. Maneuver and trickery. Why get yourself hurt if you can whip them with a shuffle and con?

We got the prisoners into a rope come where they could be adequately controlled, then headed south. The brigands were greatly exercised when Goblin and One-Eye relaxed. They didn’t think it was fair of us.

Two days later we reached Vest. With One-Eye and Goblin again supporting her grand illusion, Lady remanded the deserters to the justice of the garrison commander. We only had to kill two of them to get them there.

Something of a distraction along the road. Now there was none, and Charm drew closer by the hour. I had to face the fact that trouble beckoned.

The bulk of the Annals, which my companions believed to be in my possession, remained in Imperial hands. They had been captured at Queen’s Bridge, an old defeat that still stings. I was promised their return shortly before the crisis in the Barrowland. But that crisis prevented their delivery. Afterward, there was nothing to do but go fetch them myself.

Chapter Three

A tavern in Taglios

Willow scrunched a little more comfortably into his chair. The girls giggled and dared one another to touch his cornsilk hair. The one with the most promising eyes reached, ran her fingers down its length. Willow looked across the room, winked at Cordy Mather.

This was the life-till their fathers and brothers got wise. This was every man’s dream-with the same old lethal risks a-sneaking. If it kept on, and did not catch up, he’d soon weigh four hundred pounds and be the happiest slug in Taglios.

Who would have thought it? A simple tavern in a straitlaced burg like this. A hole in the wall like those that graced every other street corner back home, here such a novelty they couldn’t help getting rich. If the priests didn’t get over their inertia and shove a stick into the spokes.

Of course, it helped them being exotic outlanders that the whole city wanted to see. Even those priests. And their little chickies. Especially their little brown daughters.

A long, insane journey getting here, but worth every dreadful step now.

He folded his hands upon his chest and let the girls take what liberties they wanted. He could handle it. He could put up with it.

He watched Cordy tap another barrel of the bitter, third-rate green beer he’d brewed. These Taglian fools paid three times what it was worth. What kind of a place never ran into beer before? Hell. The kind of place guys with no special talents and itchy feet dream of finding.

Cordy brought a mug over. He said, “Swan, this keeps on, we’re going to have to hire somebody to help me brew. We’re going to be tapped out in a couple days.”

“Why worry? How long can it last? Those priest characters are starting to smolder now. They’re going to start looking for some excuse to shut us down. Worry about finding another racket as sweet, not about making more beer faster. What?”

“What do you mean, what?”

“You got a grim look all of a sudden.”

“The blackbird of doom just walked in the front door.”

Willow twisted so he could see that end of the room. Sure enough, Blade had come home. Tall, lean, ebony, head shaved to a polish, muscles rippling with the slightest movement, he looked like some kind of gleaming statue. He looked around without approval. Then he strode to Willow’s table, took a seat. The girls gave him the eye. He was as exotic as Willow Swan.

“Come to collect your share and tell us how lousy we are, corrupting these children?” Willow asked.

Blade shook his head. “That old spook Smoke’s having dreams again. The Woman wants you.”

“Shit.” Swan dropped his feet to the floor. Here was the fly in the ointment. The Woman wouldn’t leave them alone. “What is it this time? What’s he doing? Hemp?”

“He’s a wizard. He don’t need to do nothing to get obnoxious.”

“Shit,” Swan said again. “What do you think, we just do a fade-out here? Sell the rest of Cordy’s rat piss and head back up the river?”

A big, slow grin spread across Blade’s face. “Too late, boy. You been chosen. You can’t run fast enough. That

Smoke, he might be a joke if he was to open shop up where you came from, but around here he’s the bad boss spook pusher. You try to head out, you’re going to find your toes tied in knots.”

“That the official word?”

“They didn’t say it that way. That’s what they meant.”

“So what did he dream this time? Why drag us in?”

“Shadowmasters. More Shadowmasters. Been a big meet at Shadowcatch, he says. They’re going to stop talking and start doing. He says Moonshadow got the call. Says we’ll be seeing them in Taglian territory real soon now.”

“Big deal. Been trying to sell us that since the day we got here, practically.”

Blade’s face lost all its humor. “It was different this time, man. There’s scared and scared, you know what I mean? And Smoke and the Woman was the second kind this time. And it ain’t just Shadowmasters they got on the brain now. Said to tell you the Black Company is coming. Said you’d know what that means.”

Swan grunted as if hit in the stomach. He stood, drained the beer Cordy had brought, looked around as if unable to believe what he saw. “Damned-foolest thing I ever heard, Blade. The Black Company? Coming here?”

“Said that’s what’s got the Shadowmasters riled, Willow. Said they’re rattled good. This’s the last free country north of them, under the river. And you know what’s on the other side of Shadowcatch.”

“I don’t believe it. You know how far they’d have to come?”

“About as far as you and Cordy.” Blade had joined Willow and Cordwood Mather two thousand miles into their journey south.

“Yeah. You tell me, Blade. Who in the hell besides you and me and Cordy would be crazy enough to travel that far without any reason?”

“They got a reason. According to Smoke.”

“Like what?”

“I don’t know. You go up there like the Woman says. Maybe she’ll tell you.”

“I’ll go. We’ll all go. Just to stall. And first chance we get we’re going to get the hell out of Taglios. If they got the Shadowmasters stirred up down there, and the Black Company coming in, I don’t want to be anywhere around.”

Blade leaned back so one of the girls could wiggle in closer. His expression was questioning.

Swan said, “I seen what those bastards could do back home. I saw Roses caught between them and... Hell. Just take my word for it, Blade. Big mojo, and all bad. If they’re coming for real, and we’re still around when they show, you might end up wishing we’d let those crocs go ahead and snack on you.”

Blade never had been too clear on why he had been thrown to the crocodiles. And Willow was none too clear on why he had talked Cordy into dragging him out and taking him along. Though Blade had been a right enough guy since. He’d paid back the debt.

“I think you ought to help them, Swan,” Blade said. “I like this town. I like the people. Only thing wrong with them is they don’t have sense enough to burn all the temples down.”

“Damnit, Blade, I ain’t the guy can help.”

“You and Cordy are the only ones around who know anything about soldiering.”

“I was in the army for two months. I never even learned how to keep in step. And Cordy don’t have the stomach for it anymore. All he wants is to forget that part of his life.”

Cordy had overheard most of what had been said. He came over. “I’m not that bad off, Willow. I don’t object to soldiering when the cause is right. I just was with the wrong bunch up there. I’m with Blade. I like Taglios. I like the people. I’m willing to do what I can to see they don’t get worked over by the Shadowmasters.”

“You heard what he said? The Black Company?”

“I heard. I also heard him say they want to talk about it. I think we ought to go find out what’s going on before we run our mouths and say what we’re not going to do.”

“All right. I’m going to change. Hold the fort, and all that, Blade. Keep your mitts off the one in the red. I got first dibs.” He stalked off.

Cordy Mather grinned. “You’re catching on how to handle Willow, Blade.”

“If this’s going down the way I think, he don’t need handling. He’ll be the guy out front when they try to stop the Shadowmasters. You could roast him in coals and he’d never admit it, but he’s got a thing for Taglios.”

Cordy Mather chuckled. “You’re right. He’s finally found him a home. And no one is going to move him out. Not the Shadowmasters or the Black Company.”

“They as bad as he lets on?”

“Worse. Lots worse. You take all the legends you ever heard back home, and everything you heard tell around here, and anything you can imagine, and double it, and maybe you’re getting close. They’re mean and they’re tough and they’re good. And maybe the worst thing about them is that they’re tricky like you can’t imagine tricky. They’ve been around four, five hundred years, and no outfit lasts that long without being so damned nasty even the gods don’t screw with them.”

“Mothers, hide your babies,” Blade said. “Smoke had him a dream.”

Cordy’s face darkened. “Yeah. I’ve heard tell wizards maybe make things come true by dreaming them first. Maybe we ought to cut Smoke’s throat.”

Willow was back. He said, “Maybe we ought to find out what’s going on before we do anything.”

Cordy chuckled. Blade grinned. Then they began shooing the marks out of the tavern-each making sure an appointment was understood by one or more of the young ladies.

Chapter Four

The dark Tower

I piddled around another five days before working myself up to a little after-breakfast skull session. I introduced the subject in a golden-tongued blurt: “Our next stopover will be the Tower.”

“What?”

“Are you crazy, Croaker?”

“Knew we should have kept an eye on him after the sun went down.” Knowing glances Lady’s way. She stayed out of it.

“I thought she was going with us. Not the other way around.”

Only Murgen did not snap up a membership in the bitch-of-the-minute club. Good lad, that Murgen.

Lady, of course, already knew a stopover was needed.

“I’m serious, guys,” I said.

If I wanted to be serious, One-Eye would be, too. “Why?” he asked.

I sort of shrank. “To pick up the Annals I left behind at Queen’s Bridge.” We got caught good, there. Only because we were the best, and desperate, and sneaky, had we been able to crack the imperial encirclement. At the cost of half the Company. There were more important concerns at the time than books.

“I thought you already got them.”

“I asked for them and was told I could have them. But we were busy at the time. Remember? The Doroinator? The Limper? Toadkiller Dog? All that lot? There wasn’t any chance to actually lay hands on them.”

Lady supported me with a nod. Getting really into the spirit, there.

Goblin pasted on his most ferocious face. Made him look like a saber-toothed toad. “Then you knew about this clean back before we ever left the Barrowland.”

I admitted that that was true.

“You goatfu-Lover. I bet you’ve spent all this time concocting some half-assed off-the-wall plan that’s guaranteed to get us all killed.”

I confessed that that was mostly true, too. “We’re going to ride up there like we own the Tower. You’re going to make the garrison think Lady is still number one.”

One-Eye snorted, stomped off to the horses. Goblin got up and stared down at me. And stared some more. And sneered. “We’re just going to strut in and snatch them, eh? Like the Old Man used to say, audacity and more audacity.” He did not ask his real question.

Lady answered it for him, anyway. “I gave my word.”

Goblin did not mouth the next question, either. No one did. And Lady left it hanging.

It would be easy for her to job us. She could keep her word and have us for breakfast afterward. If she wanted.

My plan (sic), boiled down, depended entirely on my trust in her. It was a trust my comrades did not share.

But they do, however foolishly, trust me.

The Tower at Charm is the largest single construction in the world, a featureless black cube five hundred feet to the dimension. It was the first project undertaken by the Lady and the Taken after their return from the grave, so many lifetimes ago. From the Tower the Taken had marched forth, and raised their armies, and conquered half the world. Its shadow still fell upon half the earth, for few knew that the heart and blood of the empire had been sacrificed to buy victory over a power older and darker still.

There is but one ground-level entrance to the Tower. The road leading to it runs as straight as a geometrician’s dream. It passes through parklike grounds that only someone who had been there could believe was the site of history’s bloodiest battle.

I had been there. I remembered.

Goblin and One-Eye and Hagop and Otto remembered, too. Most of all, One-Eye remembered. It was on this plain that he destroyed the monster that had murdered his brother.

I recalled the crash and tumult, the screams and terrors, the horrors wrought by wizards at war, and not for the first time I wondered, “Did they really all die here? They went so easily.”

“Who you talking about?” One-Eye demanded. He did not need to concentrate on keeping Lady englamored.

“The Taken. Sometimes I think about how hard it was to get rid of the Limper. Then I wonder how so many Taken could have gone down so easy, a whole bunch in a couple days, almost never where I could see it. So sometimes I get to suspecting there was maybe some faking and two or three are still around somewhere.”

Goblin squeaked, “But they had six different plots going, Croaker. They was all backstabbing each other.”

“But I only saw a couple of them check out. None of you guys saw the others go. You heard about it. Maybe there was one more plot behind all the other plots. Maybe ...”

Lady gave me an odd, almost speculative look, like maybe she had not thought much about it herself and did not like the ideas I stirred now.

“They died dead enough for me, Croaker,” One-Eye said. “I saw plenty of bodies. Look over there. Their graves are marked.”

“That don’t mean there’s anybody in them. Raven died on us twice. Turn around and there he was again. On the hoof.”

Lady said, “You have my permission to dig them up if you like, Croaker.”

A glance showed me she was chiding me gently. Maybe even teasing. “That’s all right. Maybe someday when I’m good and bored and got nothing better to do than look at rotten corpses.”

“Gah!” Murgen said. “Can’t you guys talk about something else?” Which was a mistake.

Otto laughed. Hagop started humming. To his tune Otto sang, “The worms crawl in, the worms crawl out, the ants play the bagpipes on your snout.” Goblin and One-Eye joined in. Murgen threatened to ride over and puke on somebody.

We were distracting ourselves from the dark promise looming ahead.

One-Eye stopped singing to say, “None of the Taken were the sort who could lie low all these years, Croaker. If any survived we would have seen the fireworks. Me and Goblin would have heard something, anyway.”

“I guess you’re right.” But I did not feel reassured. Maybe some part of me just did not want the Taken to be all dead.

We were approaching the incline that led up to the doorway into the Tower. For the first time the structure betrayed signs of life. Men clad as brightly as peacocks appeared on the high battlements. A handful came out of the gateway, hastily preparing a ceremonial in greeting to their mistress. One-Eye hooted derisively when he saw their apparel.

He would not have dared last time he was there.

I leaned over and whispered, “Be careful. She designed the uniforms on them guys.”

I hoped they wanted to greet the Lady, hoped they had nothing more sinister in mind. That depended on what news they had had from the north. Sometimes evil rumors travel swifter than the wind.

“Audacity, guys,” I said. “Always audacity. Be bold. Be arrogant. Keep them reeling.” I looked at that dark entrance and reflected aloud, “They know me here.”

“That’s what scares me,” Goblin squeaked. Then he cackled.

The Tower filled more and more of the world. Murgen, who’d never seen it before, surrendered to openmouthed awe. Otto and Hagop pretended that that stone pile did not impress them. Goblin and One-Eye became too busy to pay much attention. Lady could not be impressed. She had built the place when she was someone both greater and smaller than the person she was now.

I became totally involved in creating the persona I wanted to project. I recognized the colonel in charge of the welcoming party. We had crossed paths when my fortunes had led me into the Tower before. Our feelings toward one another were ambiguous at best.

He recognized me, too. And he was baffled. The Lady and I had left the Tower together, most of a year ago.

“How you doing, Colonel?” I asked, putting on a big, friendly grin. “We finally made it back. Mission successful.”

He glanced at Lady. I did the same, from the edge of my eye. Now was her chance.

She had on her most arrogant face. I could have sworn she was the devil who haunted this Tower-Well, she was. Once. That person did not die when she lost her powers. Did she?

It looked like she would play my game. I sighed, closed my eyes momentarily, while the Tower Guard welcomed their liege.

I trusted her. But always there are reservations. You cannot predict other people. Especially not the hopeless.

Always there was the chance she might reassume the empire, hiding in her secret part of the Tower, letting her minions believe she was unchanged. There was nothing to stop her trying.

She could go that route even after keeping her promise to return the Annals.

That, my companions believed, was what she would do. And they dreaded her first order as empress of shadow restored.

Chapter Five

Chains of empire

Lady kept her promise. I had the Annals in hand within hours of entering the Tower, while its denizens were still overawed by her return. But...

“I want to go on with you, Croaker.” This while we watched the sun set from the Tower’s battlements the second evening after our arrival.

I, of course, replied with the golden tongue of a horse seller. “Uh ... Uh ... But...” Like that. Master of the glib and facile remark. Why the hell did she want to do that? She had it all, there in the Tower. A little careful faking and she could spend the rest of her natural life as the most powerful being in the world. Why go riding off with a band of tired old men, who did not know where they were going or why, only that they had to keep moving lest something-their consciences, maybe- caught them up?

“There’s nothing here for me anymore,” she said. As if that explained anything. “I want... I just want to find out what it’s like to be ordinary people.”

“You wouldn’t like it. Not near as much as you like being the Lady.”

“But I never liked that very much. Not after I had it and found out what I really had. You won’t tell me I can’t go, will you?”

Was she kidding? No. I would not. It had been the surface understanding, anyway. But it was an understanding I expected to perish once she reestablished herself in the Tower.

I was disconcerted by the implications.

“Can I go?”

“If that’s what you want.”

“There’s a problem.”

Isn’t there always if there’s a woman involved?

“I can’t leave right now. Things have gotten confused here. I need a few days to straighten them out. So I can leave with a clear conscience.”

We had not encountered any of the troubles I expected. None of her people dared scrutinize her closely. All the labors of One-Eye and Goblin were wasted effort with that audience. The word was out: the Lady was at the helm again. The Black Company was in the fold once more, under her protection. And that was enough for her people.

Wonderful. But Opal was only a few weeks away. From “Opal it was a short passage over the Sea of Torments to ports outside the empire. I thought. I wanted to get out while our luck was holding.”

“You understand, don’t you, Croaker? It’ll only be a few days. Honest. Just long enough to shape things up. The empire is a good machine that works smooth as long as the proconsuls are sure someone is in charge.”

“All right. All right. We can last a couple days. As long as you keep people away. And you keep out of the way yourself, most of the time. Don’t let them get too good a look at you.”

“I don’t intend to. Croaker?” “Yeah?”

“Go teach your grandmother to suck eggs.” Startled, I laughed. She kept getting more human all the time. And more able to laugh at herself.

She had good intentions. But he-or she-who would rule an empire becomes slave to its administrative detail. A few days came and went. And a few more. And a few more still.

I could entertain myself skulking around the Tower’s libraries, digging into rare texts from the Domination or before, unravelling the snarled threads of northern history, but for the rest of the guys it was rough. There was nothing for them to do but try to keep out of sight and worry. And bait Goblin and One-Eye, though they did not have much luck with that. To those of us without talent the Tower was just a big dark pile of rock, but to those two it was a great throbbing engine of sorcery, still peopled by numerous practitioners of the dark arts. They lived every moment in dread.

One-Eye handled it better than Goblin. He managed to escape occasionally, going out to the old battlefield to prowl among his memories. Sometimes I joined him, halfway tempted to take up Lady’s invitation to open a few old graves.

“Still not comfortable about what happened?” One-Eye asked one afternoon, as I stood leaning on a bowstave over a marker bearing the name and sigil of the Taken who had been called the Faceless Man. One-Eye’s tone was as serious as it ever gets.

“Not entirely,” I admitted. “I can’t pin it down, and it don’t matter much now, but when you reflect on what happened here, it don’t add up. I mean, it did at the time. It all looked like it was inevitable. A great kill-off that rid the world of a skillion Rebels and most of the Taken, leaving the Lady a free hand and setting her up for the Dominator at the same time. But in the context of later events ...”

One-Eye had started to stroll, pulling me along in his wake. He came to a place that was not marked at all, except in his memory. A thing called a forvalaka had perished there. A thing that had slaughtered his brother -maybe-way back in the days when we first became involved with Soulcatcher, the Lady’s legate to Beryl. The forvalaka was a sort of vampirous wereleopard originally native to One-Eye’s own home jungle, somewhere way down south. It had taken One-Eye a year to catch up with and have his revenge upon this one.

“You’re thinking about how hard it was to get rid of the Limper,” he said. His voice was thoughtful. I knew he was recalling something I thought he had put out of mind.

We were never certain that the forvalaka which killed Tom-Tom was the forvalaka that paid the price. Because in those days the Taken Soulcatcher worked closely with another Taken called Shapeshifter and there was evidence to suggest Shifter might have been in Beryl that night. And using the forvalaka shape to assure the destruction of the ruling family so the empire could take over on the cheap.

If One-Eye had not avenged Tom-Tpm on the right creature it was far too late for tears. Shifter was another of the victims of the Battle at Charm.

“I’m thinking about Limper,” I admitted. “I killed him at that inn, One-Eye. I killed him good. And if he hadn’t turned up again, I’d never have doubted that he was gone.”

“And no doubts about these?”

“Some.”

“You want to sneak out after dark and dig one of them up?”

“What’s the point? There’ll be somebody in the grave, and no way to prove it isn’t who it’s supposed to be.”

“They were killed by other Taken and by members of the Circle. That’s a little different than getting worked on by a no-talent like you.”

He meant no talent for sorcery. “I know. That’s what keeps me from getting obsessed with the whole mess. Knowing that those who supposedly killed them really had the power to do them in.”

One-Eye stared at the ground where once a cross stood with the forvalaka nailed upon it. After a while he shivered and came back to now. “Well, it doesn’t matter now. It was long ago, if not very far away. And far away is where we’ll be if we ever get out of here.” He pulled his floppy black hat forward to keep the sun out of his eyes, looked up at the Tower. We were being watched.

“Why does she want to go with us? That’s the one I keep coming back to. What’s in this for her?”

One-Eye looked at me with the oddest expression. He pushed his hat back, put his hands on his hips, cocked his head a moment, then shook it slowly. “Croaker. Sometimes you’re too much to be believed. Why are you hanging around here waiting for her instead of heading out, putting miles behind?”

It was a good question and one I shied off anytime I tried to examine it. “Well, I guess I kind of like her and think she deserves a shot at some kind of regular life. She’s all right. Really.”

I caught a transient smirk as he turned to the unmarked grave. “Life wouldn’t be half fun without you in it, Croaker. Watching you bumble through is an education in itself. How soon can we get moving? I don’t like this place.”

“I don’t know. A few more days. There’re things she has to wrap up first.” “That’s what you said-” I am afraid I got snappish. “I’ll let you know when.”

When seemed never to come. Days passed. Lady remained ensnared in the web of the administrative spider.

Then the messages began pouring in from the provinces, in response to edicts from the Tower. Each one demanded immediate attention.

We had been closed up in that dread place for two weeks.

“Get us the hell out of here, Croaker,” One-Eye demanded. “My nerves can’t take this place anymore.”

“Look, there’s stuff she’s got to do.”

“There’s stuff we’ve got to do, according to you. Who says what we got to do has to wait on what she’s got to do?”

And Goblin jumped on me. With both feet. “We put up with your infatuation for about twenty years, Croaker,” he exaggerated. “Because it was amusing. Something to ride you about when times got boring. But it ain’t nothing I mean to get killed over, I absodamnlutely guarantee. Even if she makes us all field marshals.”

I warded a flash of anger. It was hard, but Goblin was right. I had no business hanging around there, keeping everyone at maximum risk. The longer we waited, the more certain it was that something would go sour. We were having enough trouble getting along with the Tower Guards, who resented our being so close to their mistress after haying fought against her for so many years.

“We ride out in the morning,” I said. “My apologies. I was elected to lead the Company, not just Croaker. Forgive me for losing sight of that.”

Crafty old Croaker. One-Eye and Goblin looked properly abashed. I grinned. “So go get packed. We’re gone with the morning sun.”

She wakened me in the night. For a moment I thought...

I saw her face. She had heard.

She begged me to stay just one more day. Or two, at the most. She did not want to be here any more than we did, surrounded and taunted by all that she had lost. She wanted to go away, to go with us, to remain with me, the only friend she’d ever had-

She broke my heart.

It sounds sappy when you write it down in words, but a man has to do what a man has to do. In a way I was proud of me. I did not give an inch.

“There is no end to it,” I told her. “There’ll always be just one more thing that has to be done. Khatovar gets no closer while I wait. Death does. I value you, too. I don’t want to leave... Death lurks in every shadow in this place. It writhes in the heart of every man who resents my influence.” It was that kind of empire too, and in the past few days a lot of old imperials were given cause to resent me deeply.

“You promised me dinner at the Gardens in Opal.”

I promised you a lot more than that, my heart said. Aloud, I replied, “So I did. And the offer still stands. But I have to get my men out of here.”

I turned reflective while she turned uncharacteristically nervous. I saw the fires of schemes flickering behind her eyes, being rejected. There were ways she could manipulate me. We both knew that. But she never used the personal to gain political ends. Not with me, anyway.

I guess each of us, at some time, finds one person with whom we are compelled toward absolute honesty, one person whose good opinion of us becomes a substitute for the broader opinion of the world. And that opinion becomes more important than all our sneaky, sleazy schemes of greed, lust, self-aggrandizement, whatever we are up to while lying the world into believing we are just plain nice folks. I was her truth object, and she was mine.

There was only one thing we hid from one another, and that was because we were afraid that if it came into the open it would reshape everything else and maybe shatter that broader honesty.

Are lovers ever honest?

“I figure it’ll take us three weeks to reach Opal. It’ll take another week to find a trustworthy shipmaster and to work One-Eye up to crossing the Sea of Torments. So twenty-five days from today I’ll go to the Gardens. I’ll have the Camelia Grotto reserved for the evening.” I patted the lump next to my heart. That lump was a beautifully tooled leather wallet containing papers commissioning me a general in the imperial armed forces and naming me a diplomatic legate answerable only to the Lady herself.

Precious, precious. And one good reason some longtime imperials had a big hate on for me.

I am not sure just how that came about. Some banter during one of those rare hours when she was not issuing decrees or signing proclamations. Next thing I knew I had been brought to bay by a pack of tailors. They fitted me out with a complete imperial wardrobe. Never will I unravel the significance of all the piping, badges, buttons, medals, doodads, and gewgaws. I felt silly wearing all that clutter.

I didn’t need much time to see some possibilities, though, in what at first I interpreted as an elaborate practical joke.

She does have that kind of sense of humor, not always taking this great dreadfully humorless empire of hers seriously.

I am sure she saw the possibilities long before I did.

Anyway, we were talking the Gardens in Opal, and the Camelia Grotto there, the acme of that city’s society see-and-be-seen. “I’ll take my evening meal there,” I told her. “You’re welcome to join me.”

Hints of hidden things tugged at her face. She said, “All right. If I’m in town.”

It was one of those moments in which I become very uncomfortable. One of those times when nothing you say can be right, and almost anything you do say is wrong. I could see no answer but the classic Croaker approach.

I began to back away.

That is how I handle my women. Duck for cover when they get distressed.

I almost made it to the door.

She could move when she wanted. She crossed the gap and put her arms around me, rested a cheek against my chest.

And that is how they handle me, the sentimental fool. The closet romantic. I mean, I don’t even have to know them. They can work that one on me. When they really want to drill me they turn on the water.

I held her till she was ready to be let go. We did not look at one another as I turned and went away. So. She hadn’t gone for the heavy artillery.

She played fair, mostly. Give her that. Even when she was the Lady. Slick, tricky, but more or less fair.

The job of legate comes with all sorts of rights to subinfeudation and plunder of the treasury. I had drafted that pack of tailors and turned them loose on the men. I handed out commissions. I waved my magic wand and One-Eye and Goblin became colonels. Hagop and Otto turned into captains. I even cast a glamor on Murgen, so that he looked like a lieutenant. I drew us all three months’ pay in advance. It all boggled the others. I think one reason One-Eye was anxious to get moving was an eagerness to get off somewhere where he could abuse his newfound privileges. For the time being, though, he mostly bickered with Goblin about whose commission carried the greater seniority. Those two never once questioned our shift in fortunes.

The weirdest part was when she called me in to present my commissions, and insisted on a real name to enter into the record. It took me a while to remember what my name was.

We rode out as threatened. Only we did not do it as the ragged band that rode in.

I travelled in a black iron coach drawn by six raging black stallions, with Murgen driving and Otto and Hagpp riding as guards. With a string of saddle horses trailing behind. One-Eye and Goblin, disdaining the coach, rode before and behind upon mounts as fey and magnificent as the beasts which pulled the coach. With twenty-six Horse Guards as escort.

The horses she gave us were of a wild and wonderful breed, hitherto given only to the greatest champions of her empire. I had ridden one once, long ago, during the Battle at Charm, when she and I had chased down Soulcatcher. They could run forever without tiring. They were magical beasts. They constituted a gift precious beyond belief.

How do these weird things happen to me?

A year earlier I was living in a hole in the ground, under that boil on the butt of the world, the Plain of Fear, with fifty other men, constantly afraid we would be discovered by the empire. I had not had new or clean clothing in a decade, and baths and shaves were as rare and dear as diamonds.

Lying opposite me in that coach was a black bow, the first gift she ever gave me, so many years ago, before the Company deserted her. It was precious in its own right.

How the wheel turns.

Chapter Six

Opal

Hagop stared as I finished primping. “Gods. You really look the part, Croaker.”

Otto said, “Amazing what a bath and a shave will do. I believe the word is ’distinguished.’”

“Looks like a supernatural miracle to me, Ott.”

“Be sarcastic, you guys.”

“I mean it,” Otto said. “You do look good. If you had a little rug to cover where your hairline is running back toward your butt...”

He did mean it. “Well, then,” I mumbled, uncomfortable. I changed the subject. “I meant what I said. Keep those two in line.” In town only four days and already I’d bailed Goblin and One-Eye out of trouble twice. There was a limit to what even a legate could cover, hush, and smooth over.

“There’s only three of us, Croaker,” Hagop protested. “What do you want? They don’t want to be kept in line.”

“I know you guys. You’ll think of something. While you’re at it, get this junk packed up. It has to go down to the ship.”

“Yes sir, your grand legateship, sir.”

I was about to deliver one of my fiery, witty, withering rejoinders when Murgen stuck his head into the room and said, “The coach is ready, Croaker.”

And Hagop wondered aloud, “How do we keep them in line when we don’t even know where they are? Nobody’s seen them since lunchtime.”

I went out to the coach hoping I would not get an ulcer before I got out of the empire.

We roared through Opal’s streets, my escort of Horse Guards, my black stallions, my ringing black iron coach, and I. Sparks flew around the horses’ hooves and the coach’s steel wheels. Dramatic, but riding in that metal monster was like being locked inside a steel box that was being enthusiastically pounded by vandalistic giants.

We swept up to the Gardens’ understated gate, scattering gawkers. I stepped down, stood more stiffly erect than was my wont, made an effete gesture of dismissal copied from some prince seen somewhere along life’s twisted way. I strode through the gate, thrown open in haste.

I marched back to the Camelia Grotto, hoping ancient memory would not betray me. Gardens employees yapped at my heels. I ignored them.

My way took me past a pond so smooth and silvery its surface formed a mirror. I halted, mouth dropping open.

I did, indeed, cut an imposing figure, cleaned up and dressed up. But were my eyes two eggs of fire, and my open mouth a glowing furnace? “I’ll strangle those two in their sleep,” I murmured.

Worse than the fire, I had a shadow, a barely perceptible specter, behind me. It hinted that the legate was but an illusion cast by something darker.

Damn those two and their practical jokes.

When I resumed moving I noted that the Gardens were packed but silent. The guests all watched me.

I had heard that the Gardens were not as popular as once they had been.

They were there to see me. Of course. The new general. The unknown legate out of the dark tower. The wolves wanted a look at the tiger.

I should have expected it. The escort. They had had four days to tell tales around town.

I turned on all the outward arrogance I could muster. And inside I echoed to the whimper of a kid with stage fright.

I settled in in the Camelia Grotto, out of sight of the crowd. Shadows played about me. The staff came to enquire after my needs. They were revolting in their obsequiousness.

A disgusting little part of me gobbled it up. A part just big enough to show why some men lust after power. But not for me, thank you. I am too lazy. And I am, I fear, the unfortunate victim of a sense of responsibility. Put me in charge and I try to accomplish the ends to which the office was allegedly created. I guess I suffer from an impoverishment of the sociopathic spirit necessary to go big time.

How do you do the show, with the multiple-course meal, when you are accustomed to patronizing places where you take whatever is in the pot or starve? Craft. Take advantage of the covey hovering about, fearful I might devour them if not pleased. Ask this, ask that, use a physician’s habitual intuition for the hinted and implied, and I had it whipped. I sent them to the kitchens with instructions to be in no haste, for a companion might join me later.

Not that I expected Lady. I was going through the motions. I meant to keep my date without its other half.

Other guests kept finding excuses to pass by and look at the new man. I began to wish I had brought my escort along.

There was a rolling rumble like the sound of distant thunder, then a hammerclap close at hand. A wave of chatter ran through the Gardens, followed by grave-dead silence. Then the silence gave way to the rhythm of steel-tapped heels falling in unison.

I did not believe it. Even as I rose to greet her, I did not believe it.

Tower Guards hove into view, halted, parted. Goblin came hup-two-threeing between them, strutting like a drum major, looking like his namesake freshly scrounged from some especially fiery Hell. He glowed. He trailed a fiery mist which evaporated a few yards behind him. He stepped down into the Grotto and gave the place the fish-eye, and me a wink. He then marched up the far side steps and posted himself facing outward.

What the hell were they up to now? Expanding on their already overburdened practical joke?

Then Lady appeared, as fell and as radiant as fantasy, as beautiful as a dream. I clicked my heels and bowed. She descended to join me. She was a vision. She extended a hand. My manners did not desert me, despite all the hard years.

Wouldn’t this give Opal fuel for gossip?

One-Eye followed Lady down, wreathed in dark mists through which crawled shadows with eyes. He inspected the Grotto, too.

As he turned to go back the way he had come, I said, “I’m going to incinerate that hat.” Tricked out like a lord, he was, but still wearing his ragpicker’s hat.

He grinned, assumed his post.

“Have you ordered?” Lady asked.

“Yes. But only for one.”

A small horde of staff tumbled past One-Eye, terrified. The master of the Gardens himself drove them. If they had been fawning with me, they were downright disgusting with Lady. I have never been that impressed with anyone in any position of power.

It was a long, slow meal, undertaken mostly in silence, with me sending unanswered puzzled glances across the table. A memorable dining experience for me, though Lady hinted that she had known better.

The problem was, we were too much on stage to take any real enjoyment from it. Not only for the crowd, but for one another.

Along the way I admitted I had not expected her to appear, and she said my storming out of the Tower made her realize that if she did not just drop everything and go she would not shake the tentacles of imperial responsibility till someone freed her by murdering her.

“So you just walked? The place will be coming apart.”

“No. I left certain safeguards in place. I delegated powers to people whose judgment I trust, in such fashion that the empire will acrete to them gradually, and become theirs solidly before they realize that I’ve deserted.”

“I hope so.” I am a charter member of that philosophical school which believes that if anything can go sour, it will.

“It won’t matter to us, will it? We’ll be well out of range.”

“Morally, it matters, if half a continent is thrown into civil war.”

“I think I have made sufficient moral sacrifice.” A cold wind overswept me. Why can’t I keep my big damned mouth shut?

“Sorry,” I said. “You’re right. I didn’t think.”

“Apology accepted. I must confess something. I’ve taken a liberty with your plans.”

“Eh?” One of my more intellectual moments.

“I cancelled your passage aboard that merchantman.”

“What? Why?”

“It wouldn’t be seemly for a legate of the empire to travel aboard a broken-down grain barge. You are too cheap, Croaker. The quinquirireme Soulcatcher built, The Dark Wings, is in port. I ordered her readied for the crossing to Beryl.”

My gods. The very doomship that brought us north. “We aren’t well loved in Beryl.”

“Beryl is an imperial province these days. The frontier lies three hundred miles beyond the sea now. Have you forgotten your part in what made that possible?”

I only wanted to. “No. But my attention has been elsewhere the past few decades.” If the frontier had drifted that far, then imperial boots tramped the asphalted avenues of my own home city. It never occurred to me that the southern proconsuls might expand the borders beyond the maritime city-states. Only the Jewel Cities themselves were of any strategic value.

“Now who’s being bitter?”

“Who? Me? You’re right. Let’s enjoy the civilized moment. We’ll have few enough of them.” Our gazes locked. For a moment there were sparks of challenge in hers. I looked away. “How did you manage to enlist those two clowns in your charade?”

“A donative.”

I laughed. Of course. Anything for money. “And how soon will The Dark Wings be ready to sail?”

“Two days. Three at the most. And no, I won’t be handling any imperial business while I’m here.”

“Uhm. Good. I’m stuffed to the gills and ripe for roasting. We ought to go walk this off, or something. Is there a reasonably safe place we could go?”

“You probably know Opal better than I do, Croaker. I’ve never been here before.”

I suppose I looked surprised.

“I can’t be everywhere. There was a time when I was preoccupied in the north and east. A time when I was preoccupied with putting my husband down. A time when I was preoccupied with catching you. There never was a time when I was free for broadening travel.”

“Thank the stars.”

“What?”

“Meant to be a compliment. On your youthful figure.”

She gave me a calculating look. “I won’t say anything to that. You’ll stick it all in your Annals.”

I grinned. Threads of smoke snaked between my teeth.

I swore I’d get them.

Chapter Seven

Smoke and the Woman

Willow figured you could pick Smoke for what he was in any crowd. He was a wrinkled, skinny little geek that looked like somebody tried to do him in black walnut husk stain, only they missed some spots. There were spatters of pink on the backs of his hands, one arm, and one side of his face. Like maybe somebody threw acid at him and it killed the color where it hit him.

Smoke had not done anything to Willow. Not yet. But Willow did not like him. Blade did not care one way or another. Blade didn’t care much about anybody. Cordy Mather said he was reserving judgment. Willow kept his dislike back out of sight, because Smoke was what he was and because he hung out with the Woman.

The Woman was waiting for them, too. She was browner than Smoke and most anyone else in town, as far as Willow knew. She had a mean face that made it hard to look at her. She was about average size for Taglian women, which was not very big by Swan’s standards. Except for her attitude of “I am the boss” she would not have stood out much. She did not dress better than old women Willow saw in the streets. Black crows, Cordy called them. Always wrapped up in black, like old peasant women they saw when they were headed down through the territories of the Jewel Cities.

They had not been able to find out who the Woman was, but they knew she was somebody. She had connections in the Prahbrindrah’s palace, right up at the top. Smoke worked for her. Fishwives didn’t have wizards on the payroll. Anyway, both of them acted like officials trying not to look official. Like they did not know how to be regular people.

The place they met was somebody’s house. Somebody important, but Willow had not yet figured who. The class lines and heirarchies did not make sense in Taglios. Everything was always screwed up by religious affiliation.

He entered the room where they waited, helped himself to a chair. Had to show them he wasn’t some boy to run and fetch at their beck. Cordy and Blade were more circumspect. Cordy winced as Willow said, “Blade says you guys want to kick it up ’bout Smoke’s nightmares. Maybe pipe dreams?”

“You have a very good idea why you interest us, Mr. Swan. Taglios and its dependencies have been pacifistic for centuries. War is a forgotten art. It’s been unnecessary. Our neighbors were equally traumatized by the passage-”

Willow asked Smoke, “She talking Taglian?”

“As you wish, Mr. Swan.” Willow caught a hint of mischief in the Woman’s eye. “When the Free Companies came through they kicked ass so damned bad that for three hundred years anybody who even looked at a sword got so scared he puked his guts up.”

“Yeah.” Swan chuckled. “That’s right. We can talk. Tell us.”

“We want help, Mr. Swan.”

Willow mused, “Let’s see, the way I hear, around seventy-five, a hundred years ago people finally started playing games. Archery shoots, whatnot. But never anything man to man. Then here come the Shadowmasters to take over Tragevec and Kiaulune and change the names to Shadowlight and Shadowcatch.”

“Kiaulune means Shadow Gate,” Smoke said. His voice was like his skin, splotched with oddities. Squeaks, sort of. They made Willow bristle. “Not much change. Yes. They came. And like Kina in the legend they set free the wicked knowledge. In this case, how to make war.”

“And right away they started carving them an empire and if they hadn’t had that trouble at Shadowcatch and hadn’t got so busy fighting each other they would’ve been here fifteen years ago. I know. I been asking around ever since you guys started hustling us.”

“And?”

“So for fifteen years you knew they was coming someday. And for fifteen years you ain’t done squat about it. Now when you all of a sudden know the day, you want to grab three guys off the street and con them into thinking they can work some kind of miracle. Sorry, sister. Willow Swan ain’t buying. There’s your conjure man. Get old Smoke to pull pigeons out of his hat.”

“We aren’t looking for miracles, Mr. Swan. The miracle has happened. Smoke dreamed it. We’re looking for time for the miracle to take effect.”

Willow snorted.

“We have a realistic appreciation of how desperate our situation is, Mr. Swan. We have had since the Shadow-masters appeared. We have not been playing ostrich. We have been doing what seems most practical, given the cultural context. We have encouraged the masses to accept the notion that it would be a great and glorious thing to repel the onslaught when it comes.”

“You sold them that much,” Blade said. “They ready to go die.”

“And that’s all they would do,” Swan said. “Die.”

“Why?” the Woman asked.

“No organization,” said Cordy. The thoughtful one. “But organization wouldn’t be possible. No one from any of the major cult families would take orders from somebody from another one.”

“Exactly. Religious conflicts make it impossible to raise an army. Three armies, maybe. But then the high priests might be tempted to use them to settle scores here at home.”

Blade snorted. “They ought to burn the temples and strangle the priests.”

“Sentiments my brother often expresses,” the Woman said. “Smoke and I feel they might follow outsiders of proven skill who aren’t beholden to any faction.” “What? You going to make me a general?” Cordy laughed. “Willow, if the gods thought half as much of you as you think of yourself, you’d be king of the world. You figure you’re the miracle Smoke saw in his dream? They’re not going to make you a general. Not really. Unless maybe for show, while they stall.”

“What?”

“Who’s the guy keeps saying he only spent two months in the army and never even learned to keep step?”

“Oh.” Willow thought for a minute. “I think I see.”

“Actually, you will be generals,” the Woman said. “And we’ll have to rely heavily on Mr. Mather’s practical experience. But Smoke will have the final say.”

“We have to buy time,” the wizard echoed. “A lot of time. Someday soon Moonshadow will send a combined force of five thousand to invade Taglios. We have to keep from being beaten. If there’s any way possible, we have to beat the force sent against us.”

“Nothing like wishing.”

“Are you willing to pay the price?” Cordy asked. Like he thought it could be done.

“The price will be paid,” the Woman said. “Whatever it may be.”

Willow looked at her till he could no longer keep his teeth clamped on the big question. “Just who the hell are you, lady? Making your promises and plans.”

“I am the Radisha Drah, Mr. Swan.”

“Holy shit,” Swan muttered. “The prince’s big sister.” The one some people said was the real boss bull in those parts. “I knew you was somebody, but...” He was rattled right down to his toenails. But he would not have been Willow Swan if he had not leaned back, folded his hands on his belly, put on a big grin, and asked, “What’s in it for us?”

Chapter Eight

Opal

Crows

Though the empire retained a surface appearance of cohesion, a failure of the old discipline snaked through the deeps beneath. When you wandered the streets of Opal you sensed the laxness. There was flip talk about the new crop of overlords. One-Eye spoke of an increase in black marketeering, a subject on which he had been expert for a century. I overheard talk of crimes committed that were not officially sanctioned.

Lady seemed unconcerned. “The empire is seeking normalcy. The wars are over. There’s no need for the strictures of the past.”

“You saying it’s time to relax?”

“Why not? You’d be the first to scream about what a price we paid for peace.”

“Yeah. But the comparative order, the enforcement of public safety laws ... I admired that part.”

“You sweetheart, Croaker. You’re saying we weren’t all bad.”

She knew damned well I’d claimed that all along. “You know I don’t believe there’s any such thing as pure evil.”

“Yes there is. It’s festering up north in a silver spike your friends drove into the trunk of a sapling that’s the son of a god.”

“Even the Dominator may have had some redeeming quality sometime. Maybe he was good to his mother.”

“He probably ripped her heart out and ate it. Raw.”

I wanted to say something like, you married him, but did not need to give her further excuses to change her mind. She was pressed enough.

But I digress. I was remarking on the changes in the Lady’s world. What brought the whole thing home was having a dozen men drop in and ask if they could sign on with the Black Company. They were all veterans. Which meant there were men of military age at loose ends these days. During the war years there had been no extra bodies anywhere. If they were not with the grey boys or that lot they were with the White Rose.

I rejected six guys right away and accepted one, a man with his front teeth done up m gold inlays. Goblin and One-Eye, self-appointed name givers, dubbed him Sparkle.

Of the other five there were three I liked and two I did not and could find no sound reasons for going either way with any of them. I lied and told them they were all in and should report aboard The Dark Wings in time for our departure. Then I conferred with Goblin. He said he would make sure that the two I did not like would miss our departure.

I first noticed the crows then, consciously. I attached no special significance, just wondered why everywhere we went there seemed to be crows.

One-Eye wanted a private chat. “You nosed around that place where your girlfriend is staying?”

“Not to speak of.” I had given up arguing about whether or not Lady was my girlfriend.

“You ought to.”

“It’s a little late. I take it you have. What’s your beef?”

“It isn’t something you can pin down like sticking a nail through a frog, Croaker. Kind of hard to get a good look around there, anyway, what with she brought a whole damned army along. An army that I think she figures on dragging along wherever we go.”

“She won’t. Maybe she rules this end of the world, but she don’t run the Black Company. Nobody runs with this outfit who don’t answer to me and only to me.”

One-Eye clapped. “That was good, Croaker. I could almost hear the Captain talking. You even got to standing the way he did, like a big old bear about to jump on something.”

I was not original, but I didn’t think I was that transparent a borrower, either. “So what’s your point, One-Eye? Why has she got you spooked?”

“Not spooked, Croaker. Just feeling cautious. It’s her baggage. She’s dragging along enough stuff to fill a wagon.”

“Women get that way.”

“Ain’t women’s stuff. Not unless she wears magical lacies. You’d know that better than me.”

“Magical?”

“Whatever that stuff is, it’s got a charge on it. A pretty hefty one.”

“What am I supposed to do about it?”

He shrugged. “I don’t know. I just thought you ought to know.”

“If it’s magical it’s your department. Keep an eye out” — I snickered — “and let me know if you find anything useful.”

“Your sense of humor has gone to hell, Croaker.”

“I know. Must be the company I keep. My mother warned me about guys like you. Scat. Go help Goblin give those two guys the runs, or something. And stay out of trouble. Or I’ll take you across the water in a nice bouncy rowboat we’ll pull along behind the ship.”

It takes some doing for a black man to get green around the gills. One-Eye managed it.

The threat worked. He even kept Goblin from getting into mischief.

Though not in keeping with the time sequence, I hereby make notation of four new members of the Company. They are: Sparkle, Big Bucket (I don’t know why; he came with the name), Red Rudy, and Candles. Candles came with his name, too. There is a long story to tell how he got it. It does not make sense and is not especially interesting. Being the new guys they mostly stayed quiet, stayed out of the way, did the scut work, and worked on learning what we were all about. Lieutenant Murgen was happy to have somebody around he outranked.

Chapter Nine

Across the screaming sea

Our black iron coaches roared through Opal’s streets, flooding the dawn with fear and thunder. Goblin outdid himself This time the black stallions breathed smoke and fire, and flames sprang up where their hooves struck, fading only after we were long gone. Citizens stayed under cover.

One-Eye lolled beside me, restrained by protective cords. Lady sat opposite us, hands folded in her lap. The lurching of the coach bothered her not at all.

Her coach and mine parted ways. Hers headed for the north gate, bound toward the Tower. All the city-we hoped-would believe her to be in that coach. It would disappear somewhere in uninhabited country. The coachmen, handsomely bribed, should head west, to make new lives in the distant cities on the ocean coast. The trail, we hoped, would be a dead one before anyone became concerned.

Lady wore clothing that made her look like a doxy, the legate’s momentary fancy.

She travelled like a courtesan. The coach was jammed with her stuff and One-Eye reported that a load had been delivered to The Dark Wings already, with a wagon to carry it.

One-Eye was limp because he had been drugged.

Faced by a sea voyage, he became balky. He always does. Old in knowing One-Eye’s ways, Goblin had been prepared. Knockout drops in his morning brandy did the trick.

Through wakening streets we thundered, down to the waterfront, amidst the confusion of arriving stevedores. Onto the massive naval dock we rolled, to its very end, and up a broad gangway. Hooves drummed on deck timbers. Finally, we halted.

I stepped down from the coach. The ship’s captain met me with all the appropriate honors and dignities-and a furious scowl on behalf of his savaged deck. I looked around. The four new men were there. I nodded. The captain shouted. Hands began casting off. Others began helping my men unharness and unsaddle horses. I noticed a crow perched on the masthead.

Small tugs manned by convict oarsmen pulled The Dark Wings off the pier. Her own sweeps came out. Drums pounded the beat. She turned her bows seaward. In an hour we were well down the channel, running with the tide, the ship’s great black sail bellied with an offshore breeze. The device thereon was unchanged since our northward journey, though Soulcatcher had been destroyed by the Lady herself soon after the Battle at Charm. The crow kept its perch.

It was the best season for crossing the Sea of Torments. Even One-Eye admitted it was a swift and easy passage. We raised the Beryl light on the third morning and entered the harbor with the afternoon tide.

The advent of The Dark Wings had all the impact I expected and feared.

The last time that monster put in at Beryl the city’s last free, homegrown tyrant had died. His successor, chosen by Soulcatcher, became an imperial puppet. And his successors were imperial governors.

Local imperial functionaries swarmed onto the pier as the quinquirireme warped in. “Termites,” Goblin called them. “Tax farmers and pen-pushers. Little things that live under rocks and shy from the light of honest employment.”

Somewhere in his background was a cause for a big hatred of tax collectors. I understand in an intellectual sort of way. I mean there is no lower human life-form-with the possible exception of pimps-than that which revels in its state-derived power to humiliate, extort, and generate misery. I am left with a disgust for my species. But with Goblin it can become a flaming passion, with him trying to work everybody up to go out and treat a few tax people to grotesque excruciations and deaths.

The termites were shaken and distressed. They did not know what to make of this sudden, obviously portentous arrival. The advent of an imperial legate could mean a hundred things, but nothing good for the entrenched bureaucracy.

Elsewhere, all work came to a halt. Even cursing gang leaders paused to stare at the harbinger ship.

One-Eye eyeballed the situation. “Better get us out of town fast, Croaker. Else it will turn into the Tower all over again, this time with too many people asking too damned many questions.”

The coach was ready. Lady was inside. The mounts, both great and normal, were saddled. A small, light, closed wagon was brought up and assembled by the Horse Guards and filled with Lady’s plunder. We were ready to roll when the ship’s captain was ready to let us.

“Mount up,” I ordered. “One-Eye, when that gangway goes down you make like the horns of hell. Otto, take this coach off here like the Limper himself is after you.” I turned to the commander of the Horse Guards. “You break trail. Don’t give those people down there a chance to slow us down.” I boarded the coach.

“Wise thinking,” Lady said. “Get away fast or risk falling into the trap I barely escaped at the Tower.”

“That’s what I’m afraid of. I can fake this legate business only if nobody looks at me too close.” Far better to roar through town and leave them thinking me a foul-tempered, contemptuous, arrogant Taken legate southward bound on a mission that was no business of the procurators of Beryl.