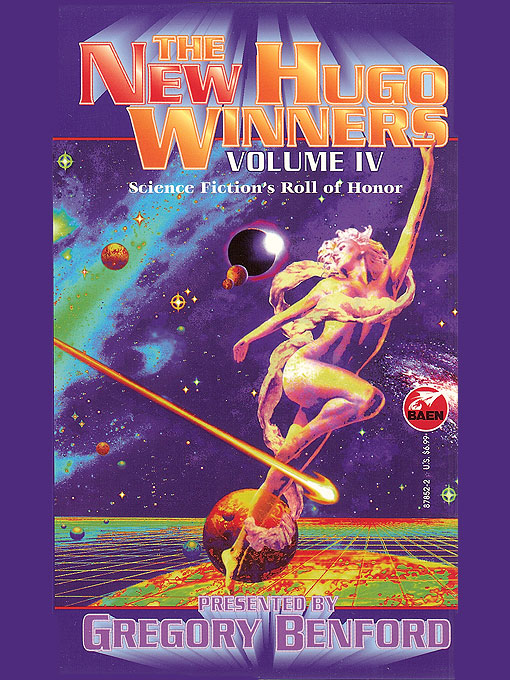

The New Hugo Winners - Volume IV

ISBN: 0-671-87852-2

Cover art by Bob Eggleton

First printing, November 1997

1992

50th Convention

Orlando

A Walk In The Sun

by Geoffrey A. Landis

Hard science fiction proceeds from a fidelity to both the facts and attitudes of science, into the murkier landscape of the human soul. In this crisply constructed story, Landis hedges his hero in with inescapable constraints, then demands that solution come from facing the hard facts of the airless moon. His way out demands an extreme of endurance and cleverness, but all along the game is played fairly—no miracles pop out of hats.

Geoff Landis is uniquely qualified to play this exacting game, for he is a trained physicist working for NASA. His career is built on solidly made short stories, making him a member of a small band, perhaps no more than thirty, who make up the hard sf community.

I have sat in convention bars and tossed ideas back and forth with Geoff for hours, and always found his instincts for technical matters on the mark. You will find this tale of adroitly conceived constraint up to his highest standard, and richly deserving its award. A tale of survival in desperate, strange circumstances, it stands in a long sf tradition, and quite matches the classics.

The pilots have a saying: a good landing is any landing you can walk away from.

Perhaps Sanjiv might have done better, if he'd been alive. Trish had done the best she could. All things considered, it was a far better landing than she had any right to expect.

Titanium struts, pencil-slender, had never been designed to take the force of a landing. Paper-thin pressure walls had buckled and shattered, spreading wreckage out into the vacuum and across a square kilometer of lunar surface. An instant before impact she remembered to blow the tanks. There was no explosion, but no landing could have been gentle enough to keep Moonshadow together. In eerie silence, the fragile ship had crumpled and ripped apart like a discarded aluminum can.

The piloting module had torn open and broken loose from the main part of the ship. The fragment settled against a crater wall. When it stopped moving, Trish unbuckled the straps that held her in the pilot's seat and fell slowly to the ceiling. She oriented herself to the unaccustomed gravity, found an undamaged EVA pack and plugged it into her suit, then crawled out into the sunlight through the jagged hole where the living module had been attached.

She stood on the grey lunar surface and stared. Her shadow reached out ahead of her, a pool of inky black in the shape of a fantastically stretched man. The landscape was rugged and utterly barren, painted in stark shades of grey and black. "Magnificent desolation," she whispered. Behind her, the sun hovered just over the mountains, glinting off shards of titanium and steel scattered across the cratered plain.

Patricia Jay Mulligan looked out across the desolate moonscape and tried not to weep.

First things first. She took the radio out from the shattered crew compartment and tried it. Nothing. That was no surprise; Earth was over the horizon, and there were no other ships in cislunar space.

After a little searching she found Sanjiv and Theresa. In the low gravity they were absurdly easy to carry. There was no use in burying them. She sat them in a niche between two boulders, facing the sun, facing west, toward where the Earth was hidden behind a range of black mountains. She tried to think of the right words to say, and failed. Perhaps as well; she wouldn't know the proper service for Sanjiv anyway. "Goodbye, Sanjiv. Goodbye, Theresa. I wish—I wish things would have been different. I'm sorry." Her voice was barely more than a whisper. "Go with God."

She tried not to think of how soon she was likely to be joining them.

She forced herself to think. What would her sister have done? Survive. Karen would survive. First: inventory your assets. She was alive, miraculously unhurt. Her vacuum suit was in serviceable condition. Life-support was powered by the suit's solar arrays; she had air and water for as long as the sun continued to shine. Scavenging the wreckage yielded plenty of unbroken food packs; she wasn't about to starve.

Second: call for help. In this case, the nearest help was a quarter of a million miles over the horizon. She would need a high-gain antenna and a mountain peak with a view of Earth.

In its computer, Moonshadow had carried the best maps of the moon ever made. Gone. There had been other maps on the ship; they were scattered with the wreckage. She'd managed to find a detailed map of Mare Nubium—useless—and a small global map meant to be used as an index. It would have to do. As near as she could tell, the impact site was just over the eastern edge of Mare Smythii—"Smith's Sea." The mountains in the distance should mark the edge of the sea, and, with luck, have a view of Earth.

She checked her suit. At a command, the solar arrays spread out to their full extent like oversized dragonfly wings and glinted in prismatic colors as they rotated to face the sun. She verified that the suit's systems were charging properly, and set off.

Close up, the mountain was less steep than it had looked from the crash site. In the low gravity, climbing was hardly more difficult than walking, although the two-meter dish made her balance awkward. Reaching the ridgetop, Trish was rewarded with the sight of a tiny sliver of blue on the horizon. The mountains on the far side of the valley were still in darkness. She hoisted the radio higher up on her shoulder and started across the next valley.

From the next mountain peak the Earth edged over the horizon, a blue and white marble half-hidden by black mountains. She unfolded the tripod for the antenna and carefully sighted along the feed. "Hello? This is Astronaut Mulligan from Moonshadow. Emergency. Repeat, this is an emergency. Does anybody hear me?"

She took her thumb off the transmit button and waited for a response, but heard nothing but the soft whisper of static from the sun.

"This is Astronaut Mulligan from Moonshadow. Does anybody hear me?" She paused again. "Moonshadow, calling anybody. Moonshadow, calling anybody. This is an emergency."

"—shadow, this is Geneva control. We read you faint but clear. Hang on, up there." She released her breath in a sudden gasp. She hadn't even realized she'd been holding it.

After five minutes the rotation of the Earth had taken the ground antenna out of range. In that time after they had gotten over their surprise that there was a survivor of the Moonshadow—she learned the parameters of the problem. Her landing had been close to the sunset terminator: the very edge of the illuminated side of the moon. The moon's rotation is slow, but inexorable. Sunset would arrive in three days. There was no shelter on the moon, no place to wait out the fourteen-day-long lunar night. Her solar cells needed sunlight to keep her air fresh. Her search of the wreckage had yielded no unruptured storage tanks, no batteries, no means to lay up a store of oxygen.

And there was no way they could launch a rescue mission before nightfall.

Too many "no"s.

She sat silent, gazing across the jagged plain toward the slender blue crescent, thinking.

After a few minutes the antenna at Goldstone rotated into range, and the radio crackled to life. "Moonshadow, do you read me? Hello, Moonshadow, do you read me?"

"Moonshadow here."

She released the transmit button and waited in long silence for her words to be carried to Earth.

"Roger, Moonshadow. We confirm the earliest window for a rescue mission is thirty days from now. Can you hold on that long?"

She made her decision and pressed the transmit button. "Astronaut Mulligan for Moonshadow. I'll be here waiting for you. One way or another."

She waited, but there was no answer. The receiving antenna at Goldstone couldn't have rotated out of range so quickly. She checked the radio. When she took the cover off, she could see that the printed circuit board on the power supply had been slightly cracked from the crash, but she couldn't see any broken leads or components clearly out of place. She banged on it with her fist—Karen's first rule of electronics: if it doesn't work, hit it—and re-aimed the antenna, but it didn't help. Clearly something in it had broken.

What would Karen have done? Not just sit here and die, that was certain. Get a move on, kiddo. When sunset catches you, you'll die.

They had heard her reply. She had to believe they heard her reply and would be coming for her. All she had to do was survive.

The dish antenna would be too awkward to carry with her. She could afford nothing but the bare necessities. At sunset her air would be gone. She put down the radio and began to walk.

Mission Commander Stanley stared at the X-rays of his engine. It was four in the morning. There would be no more sleep for him that night; he was scheduled to fly to Washington at six to testify to Congress.

"Your decision, Commander," the engine technician said. "We can't find any flaws in the X-rays we took of the flight engines, but it could be hidden. The nominal flight profile doesn't take the engines to a hundred twenty, so the blades should hold even if there is a flaw."

"How long a delay if we yank the engines for inspection?"

"Assuming they're okay, we lose a day. If not, two, maybe three."

Commander Stanley drummed his fingers in irritation. He hated to be forced into hasty decisions. "Normal procedure would be?"

"Normally we'd want to reinspect."

"Do it."

He sighed. Another delay. Somewhere up there, somebody was counting on him to get there on time. If she was still alive. If the cut-off radio signal didn't signify catastrophic failure of other systems.

If she could find a way to survive without air.

On Earth it would have been a marathon pace. On the moon it was an easy lope. After ten miles the trek fell into an easy rhythm: half a walk, half like jogging, and half bounding like a slow-motion kangaroo. Her worst enemy was boredom.

Her comrades at the academy—in part envious of the top scores that had made her the first of their class picked for a mission—had ribbed her mercilessly about flying a mission that would come within a few kilometers of the moon without landing. Now she had a chance to see more of the moon up close than anybody in history. She wondered what her classmates were thinking now. She would have a tale to tell—if only she could survive to tell it.

The warble of the low voltage warning broke her out of her reverie. She checked her running display as she started down the maintenance checklist. Elapsed EVA time, eight point three hours. System functions, nominal, except that the solar array current was way below norm. In a few moments she found the trouble: a thin layer of dust on her solar array. Not a serious problem; it could be brushed off. If she couldn't find a pace that would avoid kicking dust on the arrays, then she would have to break every few hours to housekeep. She rechecked the array and continued on.

With the sun unmoving ahead of her and nothing but the hypnotically blue crescent of the slowly rotating Earth creeping imperceptibly off the horizon, her attention wandered. Moonshadow had been tagged as an easy mission, a low-orbit mapping flight to scout sites for the future moonbase. Moonshadow had never been intended to land, not on the moon, not anywhere.

She'd landed it anyway; she'd had to.

Walking west across the barren plain, Trish had nightmares of blood and falling, Sanjiv dying beside her; Theresa already dead in the lab module; the moon looming huge, spinning at a crazy angle in the viewports. Stop the spin, aim for the terminator at low sun angles, the illumination makes it easier to see the roughness of the surface. Conserve fuel, but remember to blow the tanks an instant before you hit to avoid explosion.

That was over. Concentrate on the present. One foot in front of the other. Again. Again.

The undervoltage alarm chimed again. Dust, already?

She looked down at her navigation aid and realized with a shock that she had walked a hundred and fifty kilometers.

Time for a break anyway. She sat down on a boulder, fetched a snack-pack out of her carryall, and set a timer for fifteen minutes. The airtight quick-seal on the food pack was designed to mate to the matching port in the lower part of her faceplate. It would be important to keep the seal free of grit. She verified the vacuum seal twice before opening the pack into the suit, then pushed the food bar in so she could turn her head and gnaw off pieces. The bar was hard and slightly sweet.

She looked west across the gently rolling plain. The horizon looked flat, unreal; a painted backdrop barely out of reach. On the moon, it should be easy to keep up a pace of fifteen or even twenty miles an hour—counting time out for sleep, maybe ten. She could walk a long, long way.

Karen would have liked it; she'd always liked hiking in desolate areas. "Quite pretty, in its own way, isn't it, Sis?" Trish said. "Who'd have thought there were so many shadings of grey? Plenty of uncrowded beach. Too bad it's such a long walk to the water."

Time to move on. She continued on across terrain that was generally flat, although everywhere pocked with craters of every size. The moon is surprisingly flat; only one percent of the surface has a slope of more than fifteen degrees. The small hills she bounded over easily; the few larger ones she detoured around. In the low gravity this posed no real problem to walking. She walked on. She didn't feel tired, but when she checked her readout and realized that she had been walking for twenty hours, she forced herself to stop.

Sleeping was a problem. The solar arrays were designed to be detached from the suit for easy servicing, but had no provision to power the life-support while detached. Eventually she found a way to stretch the short cable out far enough to allow her to prop up the array next to her so she could lie down without disconnecting the power. She would have to be careful not to roll over. That done, she found she couldn't sleep. After a time she lapsed into a fitful doze, dreaming not of the Moonshadow as she'd expected, but of her sister, Karen, who—in the dream—wasn't dead at all, but had only been playing a joke on her, pretending to die.

She awoke disoriented, muscles aching, then suddenly remembered where she was. The Earth was a full handspan above the horizon. She got up, yawned, and jogged west across the gunpowder-grey sandscape.

Her feet were tender where the boots rubbed. She varied her pace, changing from jogging to skipping to a kangaroo bounce. It helped some; not enough. She could feel her feet starting to blister, but knew that there was no way to take off her boots to tend, or even examine, her feet.

Karen had made her hike on blistered feet, and had had no patience with complaints or slacking off. She should have broken her boots in before the hike. In the one-sixth gee, at least the pain was bearable.

After a while her feet simply got numb.

Small craters she bounded over; larger ones she detoured around; larger ones yet she simply climbed across. West of Mare Smythii she entered a badlands and the terrain got bumpy. She had to slow down. The downhill slopes were in full sun, but the crater bottoms and valleys were still in shadow.

Her blisters broke, the pain a shrill and discordant singing in her boots. She bit her lip to keep herself from crying and continued on. Another few hundred kilometers and she was in Mare Spumans—"Sea of Froth"—and it was clear trekking again. Across Spumans, then into the north lobe of Fecundity and through to Tranquility. Somewhere around the sixth day of her trek she must have passed Tranquility Base; she carefully scanned for it on the horizon as she traveled but didn't see anything. By her best guess she missed it by several hundred kilometers; she was already deviating toward the north, aiming for a pass just north of the crater Julius Caesar into Mare Vaporum to avoid the mountains. The ancient landing stage would have been too small to spot unless she'd almost walked right over it.

"Figures," she said. "Come all this way, and the only tourist attraction in a hundred miles is closed. That's the way things always seem to turn out, eh, Sis?"

There was nobody to laugh at her witticism, so after a moment she laughed at it herself.

Wake up from confused dreams to black sky and motionless sunlight, yawn, and start walking before you're completely awake. Sip on the insipid warm water, trying not to think about what it's recycled from. Break, cleaning your solar arrays, your life, with exquisite care. Walk. Break. Sleep again, the sun nailed to the sky in the same position it was in when you awoke. Next day do it all over. And again. And again.

The nutrition packs are low-residue, but every few days you must still squat for nature. Your life support can't recycle solid waste, so you wait for the suit to desiccate the waste and then void the crumbly brown powder to vacuum. Your trail is marked by your powdery deposits, scarcely distinguishable from the dark lunar dust.

Walk west, ever west, racing the sun.

Earth was high in the sky; she could no longer see it without craning her neck way back. When the Earth was directly overhead she stopped and celebrated, miming the opening of an invisible bottle of champagne to toast her imaginary traveling companions. The sun was well above the horizon now. In six days of travel she had walked a quarter of the way around the moon.

She passed well south of Copernicus, to stay as far out of the impact rubble as possible without crossing mountains. The terrain was eerie, boulders as big as houses, as big as shuttle tanks. In places the footing was treacherous where the grainy regolith gave way to jumbles of rock, rays thrown out by the cataclysmic impact billions of years ago. She picked her way as best she could. She left her radio on and gave a running commentary as she moved. "Watch your step here, footing's treacherous. Coming up on a hill; think we should climb it or detour around?"

Nobody voiced an opinion. She contemplated the rocky hill. Likely an ancient volcanic bubble, although she hadn't realized that this region had once been active. The territory around it would be bad. From the top she'd be able to study the terrain for a ways ahead. "Okay, listen up, everybody. The climb could be tricky here, so stay close and watch where I place my feet. Don't take chances better slow and safe than fast and dead. Any questions?" Silence; good. "Okay, then. We'll take a fifteen minute break when we reach the top. Follow me."

Past the rubble of Copernicus, Oceanus Procellarum was smooth as a golf course. Trish jogged across the sand with a smooth, even glide. Karen and Dutchman seemed to always be lagging behind or running up ahead out of sight. Silly dog still followed Karen around like a puppy, even though Trish was the one who fed him and refilled his water dish every day since Karen went away to college. The way Karen wouldn't stay close behind her annoyed Trish. Karen had promised to let her be the leader this time—but she kept her feelings to herself. Karen had called her a bratty little pest, and she was determined to show she could act like an adult. Anyway, she was the one with the map. If Karen got lost, it would serve her right.

She angled slightly north again to take advantage of the map's promise of smooth terrain. She looked around to see if Karen was there, and was surprised to see that the Earth was a gibbous ball low down on the horizon. Of course, Karen wasn't there. Karen had died years ago. Trish was alone in a spacesuit that itched and stank and chafed her skin nearly raw across the thighs. She should have broken it in better, but who would have expected she would want to go jogging in it?

It was unfair how she had to wear a spacesuit and Karen didn't. Karen got to do a lot of things that she didn't, but how come she didn't have to wear a spacesuit? Everybody had to wear a spacesuit. It was the rule. She turned to Karen to ask. Karen laughed bitterly. "I don't have to wear a spacesuit, my bratty little sister, because I'm dead. Squished like a bug and buried, remember?"

Oh, yes, that was right. Okay, then, if Karen was dead, then she didn't have to wear a spacesuit. It made perfect sense for a few more kilometers, and they jogged along together in companionable silence until Trish had a sudden thought. "Hey, wait—if you're dead, then how can you be here?"

"Because I'm not here, silly. I'm a fig-newton of your overactive imagination."

With a shock, Trish looked over her shoulder. Karen wasn't there. Karen had never been there.

"I'm sorry. Please come back. Please?"

She stumbled and fell headlong, sliding in a spray of dust down the bowl of a crater. As she slid she frantically twisted to stay face-down, to keep from rolling over on the fragile solar wings on her back. When she finally slid to a stop, the silence echoing in her ears, there was a long scratch like a badly healed scar down the glass of her helmet. The double reinforced faceplate had held, fortunately, or she wouldn't be looking at it.

She checked her suit. There were no breaks in the integrity, but the titanium strut that held out the left wing of the solar array had buckled back and nearly broken. Miraculously there had been no other damage. She pulled off the array and studied the damaged strut. She bent it back into position as best she could, and splinted the joint with a mechanical pencil tied on with two short lengths of wire. The pencil had been only extra weight anyway; it was lucky she hadn't thought to discard it. She tested the joint gingerly. It wouldn't take much stress, but if she didn't bounce around too much it should hold. Time for a break anyway.

When she awoke she took stock of her situation. While she hadn't been paying attention, the terrain had slowly turned mountainous. The next stretch would be slower going than the last bit.

"About time you woke up, sleepyhead," said Karen. She yawned, stretched, and turned her head to look back at the line of footprints. At the end of the long trail, the Earth showed as a tiny blue dome on the horizon, not very far away at all, the single speck of color in a landscape of uniform grey. "Twelve days to walk halfway around the moon," she said. "Not bad, kid. Not great, but not bad. You training for a marathon or something?"

Trish got up and started jogging, her feet falling into rhythm automatically as she sipped from the suit recycler, trying to wash the stale taste out of her mouth. She called out to Karen behind her without turning around. "Get a move on, we got places to go. You coming, or what?"

In the nearly shadowless sunlight the ground was washed-out, two-dimensional. Trish had a hard time finding footing, stumbling over rocks that were nearly invisible against the flat landscape. One foot in front of the other. Again. Again.

The excitement of the trek had long ago faded, leaving behind a relentless determination to prevail, which in turn had faded into a kind of mental numbness. Trish spent the time chatting with Karen, telling the private details of her life, secretly hoping that Karen would be pleased, would say something telling her she was proud of her. Suddenly she noticed that Karen wasn't listening; had apparently wandered off on her sometime when she hadn't been paying attention.

She stopped on the edge of a long, winding rille. It looked like a riverbed just waiting for a rainstorm to fill it, but Trish knew it had never known water. Covering the bottom was only dust, dry as powdered bone. She slowly picked her way to the bottom, careful not to slip again and risk damage to her fragile life-support system. She looked up at the top. Karen was standing on the rim waving at her. "Come on! Quit dawdling, you slowpoke—you want to stay here forever?"

"What's the hurry? We're ahead of schedule. The sun is high up in the sky, and we're halfway around the moon. We'll make it, no sweat."

Karen came down the slope, sliding like a skier in the powdery dust. She pressed her face up against Trish's helmet and stared into her eyes with a manic intensity that almost frightened her. "The hurry, my lazy little sister, is that you're halfway around the moon, you've finished with the easy part and it's all mountains and badlands from here on, you've got six thousand kilometers to walk in a broken spacesuit, and if you slow down and let the sun get ahead of you, and then run into one more teensy little problem, just one, you'll be dead, dead, dead, just like me. You wouldn't like it, trust me. Now get your pretty little lazy butt into gear and move!"

And, indeed, it was slow going. She couldn't bound down slopes as she used to, or the broken strut would fail and she'd have to stop for painstaking repair. There were no more level plains; it all seemed to be either boulder fields, crater walls, or mountains. On the eighteenth day she came to a huge natural arch. It towered over her head, and she gazed up at it in awe, wondering how such a structure could have been formed on the moon.

"Not by wind, that's for sure," said Karen. "Lava, I'd figure. Melted through a ridge and flowed on, leaving the hole; then over the eons micrometeoroid bombardment ground off the rough edges. Pretty, though, isn't it?"

"Magnificent."

Not far past the arch she entered a forest of needle-thin crystals. At first they were small, breaking like glass under her feet, but then they soared above her, six-sided spires and minarets in fantastic colors. She picked her way in silence between them, bedazzled by the forest of light sparkling between the sapphire spires. The crystal jungle finally thinned out and was replaced by giant crystal boulders, glistening iridescent in the sun. Emeralds? Diamonds?

"I don't know, kid. But they're in our way. I'll be glad when they're behind us."

And after a while the glistening boulders thinned out as well, until there were only a scattered few glints of color on the slopes of the hills beside her, and then at last the rocks were just rocks, craggy and pitted.

Crater Daedalus, the middle of the lunar farside. There was no celebration this time. The sun had long ago stopped its lazy rise, and was imperceptibly dropping toward the horizon ahead of them.

"It's a race against the sun, kid, and the sun ain't making any stops to rest. You're losing ground."

"I'm tired. Can't you see I'm tired? I think I'm sick. I hurt all over. Get off my case. Let me rest. Just a few more minutes? Please?"

"You can rest when you're dead." Karen laughed in a strangled, high-pitched voice. Trish suddenly realized that she was on the edge of hysteria. Abruptly she stopped laughing. "Get a move on, kid. Move!"

The lunar surface passed under her, an irregular grey treadmill.

Hard work and good intentions couldn't disguise the fact that the sun was gaining. Every day when she woke up the sun was a little lower down ahead of her, shining a little more directly in her eyes.

Ahead of her, in the glare of the sun she could see an oasis, a tiny island of grass and trees in the lifeless desert. She could already hear the croaking of frogs: braap, braap, BRAAP!

No. That was no oasis; that was the sound of a malfunction alarm. She stopped, disoriented. Overheating. The suit air conditioning had broken down. It took her half a day to find the clogged coolant valve and another three hours soaked in sweat to find a way to unclog it without letting the precious liquid vent to space. The sun sank another handspan toward the horizon.

The sun was directly in her face now. Shadows of the rocks stretched toward her like hungry tentacles, even the smallest looking hungry and mean. Karen was walking beside her again, but now she was silent, sullen.

"Why won't you talk to me? Did I do something? Did I say something wrong? Tell me."

"I'm not here, little sister, I'm dead. I think it's about time you faced up to that."

"Don't say that. You can't be dead."

"You have an idealized picture of me in your mind. Let me go. Let me go!"

"I can't. Don't go. Hey—do you remember the time we saved up all our allowances for a year so we could buy a horse? And we found a stray kitten that was real sick, and we took the shoebox full of our allowance and the kitten to the vet, and he fixed the kitten but wouldn't take any money?"

"Yeah, I remember. But somehow we still never managed to save enough for a horse." Karen sighed. "Do you think it was easy growing up with a bratty little sister dogging my footsteps, trying to imitate everything I did?"

"I wasn't either bratty."

"You were too."

"No, I wasn't. I adored you." Did she? "I worshipped you."

"I know you did. Let me tell you, kid, that didn't make it any easier. Do you think it was easy being worshipped? Having to be a paragon all the time? Christ, all through high school, when I wanted to get high, I had to sneak away and do it in private, or else I knew my damn kid sister would be doing it too."

"You didn't. You never."

"Grow up, kid. Damn right I did. You were always right behind me. Everything I did, I knew you'd be right there doing it next. I had to struggle like hell to keep ahead of you, and you, damn you, followed effortlessly. You were smarter than me—you know that, don't you?—and how do you think that made me feel?"

"Well, what about me? Do you think it was easy for me? Growing up with a dead sister—everything I did, it was 'Too bad you can't be more like Karen' and 'Karen wouldn't have done it that way' and 'If only Karen had. . . .' How do you think that made me feel, huh? You had it easy—I was the one who had to live up to the standards of a goddamn angel."

"Tough breaks, kid. Better than being dead."

"Damn it, Karen, I loved you. I love you. Why did you have to go away?"

"I know that, kid. I couldn't help it. I'm sorry. I love you too, but I have to go. Can you let me go? Can you just be yourself now, and stop trying to be me?"

"I'll . . . I'll try."

"Goodbye, little sister."

"Goodbye, Karen."

She was alone in the settling shadows on an empty, rugged plain. Ahead of her, the sun was barely kissing the ridgetops. The dust she kicked up was behaving strangely; rather than falling to the ground, it would hover half a meter off the ground. She puzzled over the effect, then saw that all around her, dust was silently rising off the ground. For a moment she thought it was another hallucination, but then realized it was some kind of electrostatic charging effect. She moved forward again through the rising fog of moondust. The sun reddened, and the sky turned a deep purple.

The darkness came at her like a demon. Behind her only the tips of mountains were illuminated, the bases disappearing into shadow. The ground ahead of her was covered with pools of ink that she had to pick her way around. Her radio locator was turned on, but receiving only static. It could only pick up the locator beacon from the Moonshadow if she got in line of sight of the crash site. She must be nearly there, but none of the landscape looked even slightly familiar. Ahead was that the ridge she'd climbed to radio Earth? She couldn't tell. She climbed it, but didn't see the blue marble. The next one?

The darkness had spread up to her knees. She kept tripping over rocks invisible in the dark. Her footsteps struck sparks from the rocks, and behind her footprints glowed faintly. Triboluminescent glow, she thought nobody has ever seen that before. She couldn't die now, not so close. But the darkness wouldn't wait. All around her the darkness lay like an unsuspected ocean, rocks sticking up out of the tidepools into the dying sunlight. The undervoltage alarm began to warble as the rising tide of darkness reached her solar array. The crash site had to be around here somewhere, it had to. Maybe the locator beacon was broken? She climbed up a ridge and into the light, looking around desperately for clues. Shouldn't there have been a rescue mission by now?

Only the mountaintops were in the light. She aimed for the nearest and tallest mountain she could see and made her way across the darkness to it, stumbling and crawling in the ocean of ink, at last pulling herself into the light like a swimmer gasping for air. She huddled on her rocky island, desperate as the tide of darkness slowly rose about her. Where were they? Where were they?

Back on Earth, work on the rescue mission had moved at a frantic pace. Everything was checked and triple-checked in space, cutting corners was an invitation for sudden death, but still the rescue mission had been dogged by small problems and minor delays, delays that would have been routine for an ordinary mission, but loomed huge against the tight mission deadline.

The scheduling was almost impossibly tight—the mission had been set to launch in four months, not four weeks. Technicians scheduled for vacations volunteered to work overtime, while suppliers who normally took weeks to deliver parts delivered overnight. Final integration for the replacement for Moonshadow, originally to be called Explorer but now hastily re-christened Rescuer, was speeded up, and the transfer vehicle launched to the Space Station months ahead of the original schedule, less than two weeks after the Moonshadow crash. Two shuttle-loads of propellant swiftly followed, and the transfer vehicle was mated to its aeroshell and tested. While the rescue crew practiced possible scenarios on the simulator, the lander, with engines inspected and replaced, was hastily modified to accept a third person on ascent, tested, and then launched to rendezvous with Rescuer. Four weeks after the crash the stack was fueled and ready, the crew briefed, and the trajectory calculated. The crew shuttle launched through heavy fog to join their Rescuer in orbit.

Thirty days after the unexpected signal from the moon had revealed a survivor of the Moonshadow expedition, Rescuer left orbit for the moon.

From the top of the mountain ridge west of the crash site, Commander Stanley passed his searchlight over the wreckage one more time and shook his head in awe. "An amazing job of piloting," he said. "Looks like she used the TEI motor for braking, and then set it down on the RCS verniers."

"Incredible," Tanya Nakora murmured. "Too bad it couldn't save her."

The record of Patricia Mulligan's travels was written in the soil around the wreck. After the rescue team had searched the wreckage, they found the single line of footsteps that led due west, crossed the ridge, and disappeared over the horizon. Stanley put down the binoculars. There was no sign of returning footprints. "Looks like she wanted to see the moon before her air ran out," he said. Inside his helmet he shook his head slowly. "Wonder how far she got?"

"Could she be alive somehow?" asked Nakora. "She was a pretty ingenious kid."

"Not ingenious enough to breathe vacuum. Don't fool yourself—this rescue mission was a political toy from the start. We never had a chance of finding anybody up here still alive."

"Still, we had to try, didn't we?"

Stanley shook his head and tapped his helmet. "Hold on a sec, my damn radio's acting up. I'm picking up some kind of feedback—almost sounds like a voice."

"I hear it too, Commander. But it doesn't make any sense."

The voice was faint in the radio. "Don't turn off the lights. Please, please, don't turn off your light. . . ."

Stanley turned to Nakora. "Do you . . . ?"

"I hear it, Commander . . . but I don't believe it."

Stanley picked up the searchlight and began sweeping the horizon. "Hello? Rescuer calling Astronaut Patricia Mulligan. Where the hell are you?"

The spacesuit had once been pristine white. It was now dirty grey with moondust, only the ragged and bent solar array on the back carefully polished free of debris. The figure in it was nearly as ragged.

After a meal and a wash, she was coherent and ready to explain.

"It was the mountaintop. I climbed the mountaintop to stay in the sunlight, and I just barely got high enough to hear your radios."

Nakora nodded. "That much we figured out. But the rest—the last month—you really walked all the way around the moon? Eleven thousand kilometers?"

Trish nodded. "It was all I could think of. I figured, about the distance from New York to LA and back—people have walked that and lived. It came to a walking speed of just under ten miles an hour. Farside was the hard part—turned out to be much rougher than nearside. But strange and weirdly beautiful, in places. You wouldn't believe the things I saw."

She shook her head, and laughed quietly. "I don't believe some of the things I saw. The immensity of it—we've barely scratched the surface. I'll be coming back, Commander. I promise you."

"I'm sure you will," said Commander Stanley. "I'm sure you will."

As the ship lifted off the moon, Trish looked out for a last view of the surface. For a moment she thought she saw a lonely figure standing on the surface, waving her goodbye. She didn't wave back.

She looked again, and there was nothing out there but magnificent desolation.

Gold

by Isaac Asimov

Isaac Asimov introduced earlier collections of Hugo winners with his jovial authority. This story carries forward effortlessly, gliding on his unique gift for quick narration and darting ideas. Isaac was a genius at the apparently simple. Anyone who thinks that writing about complex ideas, including both modern science and the human heart, with clarity and simplicity, is welcome to try; if so, take Asimov as your model. Like Arthur Clarke, his method is deceptively transparent; indeed, readers typically remark of them both, as I heard a fan put it, "They have no style, they just write."

Ah, the depths of admirable innocence behind that phrase. For it is best if a reader does not see the furniture moving around behind a thin curtain, while reading a story. The events of the imagined world should be real, manufactured by the reader himself in that theatre of the mind which words excite. Reading is an intellectually demanding amusement, for it calls upon us to take symbols and make of them pictures, sights, sounds, to conjure up people and emotions with our mental machinery. How much more difficult to do this if the devices of the author peek into the mental field of vision, destroying the fleeting sense of real events unfolding. So it is with style, I think, for most readers. They do not want to see style so much as feel it. They desire to be propelled through events and sensations and ideas which unfurl effortlessly, as though ordained, and they do not wish to feel any intrusion. The author's voice does this task best when it is transparent, seemingly "natural," inevitable.

Isaac had that gift. Of course, what style appears invisible yet effective depends upon the taste of the reader. For a huge readership, Isaac's worked that wonder. He is the only author represented with a book in each classification of the Dewey Decimal System in the Library of Congress. Not only did he write compulsively, he did it well. I have known only two writers who truly enjoyed the sheer process of writing— from the deep concentration through the mechanical details of hammering out thoughts on a keyboard, through (in Isaac's case) the tedium of making up cards for each important word in a book, to create its Index. (The other is Dean Koontz, whose work methods are quite different, but inner demons seem similar at least in their incessant energies.)

Alas, we shall have no more of Isaac's limpid prose. I was so struck by his death that when his widow, Janet, proposed to me in 1995 that I write a novel set in his Foundation, I at first declined. My first thought was, how could I echo that style? Isaac wrote much of his fiction in a way he termed "direct and spare," though in the later works he relaxed this constraint a bit. For the Foundation novels he used a particularly bare-boards approach, with virtually no background descriptions or novelistic details. I found that I had to explore Asimovian ideas my own way, so the resulting book, Foundation's Fear, is not an imitation Asimov novel, but a Benford novel using Asimov's basic ideas and backdrop.

I recall my last conversation with him, only months before he died. His prodigious memory had failed and he could again read favorite mysteries, not knowing how they would turn out. An oblique blessing indeed. He told me how his memory once had organized each scrap of new information, filing it properly under instinctive headings for instant recovery. "It saved time looking things up," he said. I once tested this filing system by demanding that he immediately tell me a joke with a camel in it. Without blinking, he did. Okay, I said, now another. He delivered just as quickly. I wondered how many more camel jokes he had and he shot back, "Three."

His books were filled with such almost offhand intelligence and knowledge. Readers flocked to them. Such is the continuing impact of probably the most influential sf novelist since Wells. For a memorable lingering moment with him, "Gold" give us Isaac still at his peak.

Jonas Willard looked from side to side and tapped his baton on the stand before him.

He said, "Understood now? This is just a practice scene, designed to find out if we know what we're doing. We've gone through this enough times so that I expect a professional performance now. Get ready. All of you get ready."

He looked again from side to side. There was a person at each of the voice-recorders, and there were three others working the image projection. A seventh was for the music and an eighth for the all-important background. Others waited to one side for their turn.

Willard said, "All right now. Remember this old man has spent his entire adult life as a tyrant. He is accustomed to having everyone jump at his slightest word, to having everyone tremble at his frown. That is all gone now but he doesn't know it. He faces his daughter whom he thinks of only as a bent-headed obsequious girl who will do anything he says, and he cannot believe that it is an imperious queen that he now faces. So let's have the King."

Lear appeared. Tall, white hair and beard, somewhat disheveled, eyes sharp and piercing.

Willard said, "Not bent. Not bent. He's eighty years old but he doesn't think of himself as old. Not now. Straight. Every inch a king." The image was adjusted. "That's right. And the voice has to be strong. No quavering. Not now. Right?"

"Right, chief," said the Lear voice-recorder, nodding.

"All right. The Queen."

And there she was, almost as tall as Lear, standing straight and rigid as a statue, her draped clothing in fine array, nothing out of place. Her beauty was as cold and unforgiving as ice.

"And the Fool."

A little fellow, thin and fragile, like a frightened teenager but with a face too old for a teenager and with a sharp look in eyes that seemed so large that they threatened to devour his face.

"Good," said Willard. "Be ready for Albany. He comes in pretty soon. Begin the scene." He tapped the podium again, took a quick glance at the marked-up play before him and said, "Lear!" and his baton pointed to the Lear voice-recorder, moving gently to mark the speech cadence that he wanted created.

Lear says, "How now, daughter? What makes that frontlet on? Methinks you are too much o' late i' th' frown."

The Fool's thin voice, fifelike, piping, interrupts, "Thou wast a pretty fellow when thou hadst no need to care for her frowning—"

Goneril, the Queen, turns slowly to face the Clown as he speaks, her eyes turning momentarily into balls of lurid light—doing it so momentarily that those watching caught the impression rather than viewed the fact. The Fool completes his speech in gathering fright and backs his way behind Lear in a blind search for protection against the searing glance.

Goneril proceeds to tell Lear the facts of life and there is the faint crackling of thin ice as she speaks, while the music plays in soft discords, barely heard.

Nor are Goneril's demands so out of line, for she wants an orderly court and there couldn't be one as long as Lear still thought of himself as tyrant. But Lear is in no mood to recognize reason. He breaks into a passion and begins railing.

Albany enters. He is Goneril's consort—round-faced, innocent, eyes looking about in wonder. What is happening? He is completely drowned out by his dominating wife and by his raging father-in-law. It is at this point that Lear breaks into one of the great piercing denunciations in all of literature. He is overreacting. Goneril has not as yet done anything to deserve this, but Lear knows no restraint. He says:

"Hear, Nature, hear dear goddess, hear!

Suspend thy purpose, if thou didst intend

To make this creature fruitful.

Into her womb convey sterility;

Dry up in her the organs of increase;

And from her derogate body never spring

A babe to honour her! If she must teem,

Create her child of spleen, that it may live

And be a thwart disnatur'd torment to her.

Let it stamp wrinkles in her brow of youth,

With cadent tears fret channels in her cheeks,

Turn all her mother's pains and benefits

To laughter and contempt, that she may feel

How sharper than a serpent's tooth, it is

To have a thankless child!"

The voice-recorder strengthened Lear's voice for this speech, gave it a distant hiss, his body became taller and somehow less substantial as though it had been converted into a vengeful Fury.

As for Goneril, she remained untouched throughout, never flinching, never receding, but her beautiful face, without any change that could be described, seemed to accumulate evil so that by the end of Lear's curse, she had the appearance of an archangel still, but an archangel ruined. All possible pity had been wiped out of the countenance, leaving behind only a devil's dangerous magnificence.

The Fool remained behind Lear throughout, shuddering. Albany was the very epitome of confusion, asking useless questions, seeming to want to step between the two antagonists and clearly afraid to do so.

Willard tapped his baton and said, "All right. It's been recorded and I want you all to watch the scene." He lifted his baton high and the synthesizer at the rear of the set began what could only be called the instant replay.

It was watched in silence, and Willard said, "It was good, but I think you'll grant it was not good enough. I'm going to ask you all to listen to me, so that I can explain what we're trying to do. Computerized theater is not new, as you all know. Voices and images have been built up to beyond what human beings can do. You don't have to break your speechifying in order to breathe; the range and quality of the voices are almost limitless; and the images can change to suit the words and action. Still, the technique has only been used, so far, for childish purposes. What we intend now is to make the first serious compu-drama the world has ever seen, and nothing will do—for me, at any rate—but to start at the top. I want to do the greatest play written by the greatest playwright in history: King Lear by William Shakespeare.

"I want not a word changed. I want not a word left out. I don't want to modernize the play. I don't want to remove the archaisms, because the play, as written, has its glorious music and any change will diminish it. But in that case, how do we have it reach the general public? I don't mean the students, I don't mean the intellectuals, I mean everybody. I mean people who've never watched Shakespeare before and whose idea of a good play is a slapstick musical. This play is archaic in spots, and people don't talk in iambic pentameter. They are not even accustomed to hearing it on the stage.

"So we're going to have to translate the archaic and the unusual. The voices, more than human, will, just by their timbre and changes, interpret the words. The images will shift to reinforce the words.

"Now Goneril's change in appearance as Lear's curse proceeded was good. The viewer will gauge the devastating effect it has on her even though her iron will won't let it show in words. The viewer will therefore feel the devastating effect upon himself, too, even if some of the words Lear uses are strange to him.

"In that connection, we must remember to make the Fool look older with every one of his appearances. He's a weak, sickly fellow to begin with, broken-hearted over the loss of Cordelia, frightened to death of Goneril and Regan, destroyed by the storm from which Lear, his only protector, can't protect him—and I mean by that the storm of Lear's daughter's as well as of the raging weather. When he slips out of the play in Act III, Scene VI, it must be made plain that he is about to die. Shakespeare doesn't say so, so the Fool's face must say so.

"However, we've got to do something about Lear. The voice-recorder was on the right track by having a hissing sound in the voice-track. Lear is spewing venom; he is a man who, having lost power, has no recourse but vile and extreme words. He is a cobra who cannot strike. But I don't want the hiss noticeable until the right time. What I am more interested in is the background."

The woman in charge of background was Meg Cathcart. She had been creating backgrounds for as long as the compu-drama technique had existed.

"What do you want in background?" Cathcart asked, coolly.

"The snake motif," said Willard. "Give me some of that and there can be less hiss in Lear's voice. Of course, I don't want you to show a snake. The too obvious doesn't work. I want a snake there that people can't see but that they can feel without quite noting why they feel. I want them to know a snake is there without really knowing it is there, so that it will chill them to the bone, as Lear's speech should. So when we do it over, Meg, give us a snake that is not a snake."

"And how do I do that, Jonas?" said Cathcart, making free with his first name. She knew her worth and how essential she was.

He said, "I don't know. If I did I'd be a backgrounder instead of a lousy director. I only know what I want. You've got to supply it. You've got to supply sinuosity, the impression of scales. Until we get to one point. Notice when Lear says, 'How sharper than a serpent's tooth it is to have a thankless child.' That is power. The whole speech leads up to that and it is one of the most famous quotes in Shakespeare. And it is sibilant. There is the 'sh,' the three s's in 'serpent's' and in 'thankless,' and the two unvoiced 'th's in 'tooth' and 'thankless.' That can be hissed. If you keep down the hiss as much as possible in the rest of the speech, you can hiss here, and you should zero in to his face and make it venomous. And for background, the serpent—which, after all, is now referred to in the words—can make its appearance in background. A flash of an open mouth and fangs, fangs— We must have the momentary appearance of fangs as Lear says, 'a serpent's tooth.' "

Willard felt very tired suddenly. "All right. We'll try again tomorrow. I want each one of you to go over the entire scene and try to work out the strategy you intend to use. Only please remember that you are not the only ones involved. What you do must match the others, so I'll encourage you to talk to each other about this—and, most of all, to listen to me because I have no instrument to handle and I alone can see the play as a whole. And if I seem as tyrannical as Lear at his worst in spots, well, that's my job."

Willard was approaching the great storm scene, the most difficult portion of this most difficult play, and he felt wrung out. Lear has been cast out by his daughters into a raging storm of wind and rain, with only his Fool for company, and he has gone almost mad at this mistreatment. To him, even the storm is not as bad as his daughters.

Willard pointed his baton and Lear appeared. A point in another direction and the Fool was there clinging, disregarded, to Lear's left leg. Another point and the background, came in, with its impression of a storm, of a howling wind, of driving rain, of the crackle of thunder and the flash of lightning.

The storm took over, a phenomenon of nature, but even as it did so, the image of Lear extended and became what seemed mountain-tall. The storm of his emotions matched the storm of the elements, and his voice gave back to the wind every last howl. His body lost substance and wavered with the wind as though he himself were a storm cloud, contending on an equal basis with the atmospheric fury. Lear, having failed with his daughters, defied the storm to do its worst. He called out in a voice that was far more than human:

"Blow, winds, and crack your cheeks! rage! blow!

You cataracts and hurricanoes, spout

Till you have drench'd our steeples, drown'd the cocks!

You sulph'rous and thought-executing fires.

Vaunt-couriers to oak-cleaving thunderbolts,

Singe my white head! And thou, all-shaking thunder,

Strike flat the thick rotundity o' th' world.

Crack Nature's moulds, all germains spill at once.

That make ingrateful man."

The Fool interrupts, his voice shrilling, and making Lear's defiance the more heroic by contrast. He begs Lear to make his way back to the castle and make peace with his daughters, but Lear doesn't even hear him. He roars on:

"Rumble thy bellyful! Spit, fire! spout, rain!

Nor rain, wind, thunder, fire are my daughters.

I tax not you, you elements, with unkindness.

I never gave you kingdom, call'd you children,

You owe me no subscription. Then let fall

Your horrible pleasure. Here I stand your slave,

A poor, infirm, weak, and despis'd old man . . ."

The Duke of Kent, Lear's loyal servant (though the King in a fit of rage has banished him) finds Lear and tries to lead him to some shelter. After an interlude in the castle of the Duke of Gloucester, the scene returns to Lear in the storm, and he is brought, or rather dragged, to a hovel.

And then, finally, Lear learns to think of others. He insists that the Fool enter first and then he lingers outside to think (undoubtedly for the first time in his life) of the plight of those who are not kings and courtiers.

His image shrank and the wildness of his face smoothed out. His head was lifted to the rain, and his words seemed detached and to be coming not quite from him, as though he were listening to someone else read the speech. It was, after all, not the old Lear speaking, but a new and better Lear, refined and sharpened by suffering. With an anxious Kent watching, and striving to lead him into the hovel, and with Meg Cathcart managing to work up an impression of beggars merely by producing the fluttering of rags, Lear says:

"Poor naked wretches, wheresoe'er you are,

That bide the pelting of this pithess storm.

How shall your houseless heads and unfed sides,

Your loop'd and window'd raggedness, defend you

From seasons such as these? O, I have ta'en

Too little care of this! Take physic, pomp;

Expose thyself to feel what wretches feel,

That thou mayst shake the superflux to them

And show the heavens more just."

"Not bad," said Wilbur, eventually. "We're getting the idea. Only, Meg, rags aren't enough. Can you manage an impression of hollow eyes? Not blind ones. The eyes are there, but sunken in."

"I think I can do that," said Cathcart.

It was difficult for Willard to believe. The money spent was greater than expected. The time it had taken was considerably greater than had been expected. And the general weariness was far greater than had been expected. Still, the project was coming to an end.

He had the reconciliation scene to get through—so simple that it would require the most delicate touches. There would be no background, no souped-up voices, no images, for at this point Shakespeare became simple. Nothing beyond simplicity was needed.

Lear was an old man, just an old man. Cordelia, having found him, was a loving daughter, with none of the majesty of Goneril, none of the cruelty of Regan, just softly endearing.

Lear, his madness burned out of him, is slowly beginning to understand the situation. He scarcely recognizes Cordelia at first and thinks he is dead and she is a heavenly spirit. Nor does he recognize the faithful Kent.

When Cordelia tries to bring him back the rest of the way to sanity, he says:

"Pray, do not mock me.

I am a very foolish fond old man.

Fourscore and upward, not an hour more nor less.

And, to deal plainly,

I fear I am not in my perfect mind.

Methinks I should know you, and know this man;

Yet I am doubtful; for I am mainly ignorant

What place this is; and all the skills I have

Remembers not these garments; nor I know not

Where I did lodge last night. Do not laugh at me;

For (as I am a man) I think this lady

To be my child Cordelia."

Cordelia tells him she is and he says:

"Be your tears wet? Yes, faith. I pray weep not.

If you have poison for me, I will drink it.

I know you do not love me; for your sisters

Have, as I do remember, done me wrong.

You have some cause, they have not."

All poor Cordelia can say is "No cause, no cause."

And eventually, Willard was able to draw a deep breath and say, "We've done all we can do. The rest is in the hands of the public."

It was a year later that Willard, now the most famous man in the entertainment world, met Gregory Laborian. It had come about almost accidentally and largely because of the activities of a mutual friend. Willard was not grateful.

He greeted Laborian with what politeness he could manage and cast a cold eye on the time-strip on the wall.

He said, "I don't want to seem unpleasant or inhospitable, Mr.—uh—but I'm really a very busy man, and don't have much time."

"I'm sure of it, but that's why I want to see you. Surely, you want to do another compu-drama."

"Surely I intend to, but," and Willard smiled dryly, "King Lear is a hard act to follow and I don't intend to turn out something that will seem like trash in comparison."

"But what if you never find anything that can match King Lear?"

"I'm sure I never will, but I'll find something."

"I have something."

"Oh?"

"I have a story, a novel, that could be made into a compu-drama."

"Oh, well. I can't really deal with items that come in over the transom."

"I'm not offering you something from a slush pile. The novel has been published and it has been rather highly thought of."

"I'm sorry. I don't want to be insulting. But I didn't recognize your name when you introduced yourself."

"Laborian. Gregory Laborian."

"But I still don't recognize it. I've never read anything by you. I've never heard of you."

Laborian sighed. "I wish you were the only one, but you're not. Still, I could give you a copy of my novel to read."

Willard shook his head. "That's kind of you, Mr. Laborian, but I don't want to mislead you. I have no time to read it. And even if I had the time—I just want you to understand—I don't have the inclination."

"I could make it worth your while, Mr. Willard."

"In what way?"

"I could pay you. I wouldn't consider it a bribe, merely an offer of money that you would well deserve if you worked with my novel."

"I don't think you understand, Mr. Laborian, how much money it takes to make a first-class compu-drama. I take it you're not a multimillionaire."

"No, I'm not, but I can pay you a hundred thousand globo-dollars."

"If that's a bribe, at least it's a totally ineffective one. For a hundred thousand globo-dollars, I couldn't do a single scene."

Laborian sighed again. His large brown eyes looked soulful. "I understand, Mr. Willard, but if you'll just give me a few more minutes—" (for Willard's eyes were wandering to the time-strip again.)

"Well, five more minutes. That's all I can manage really."

"It's all I need. I'm not offering the money for making the compu-drama. You know, and I know, Mr. Willard, that you can go to any of a dozen people in the country and say you are doing a compu-drama and you'll get all the money you need. After King Lear, no one will refuse you anything, or even ask you what you plan to do. I'm offering you one hundred thousand globo-dollars for your own use."

"Then it is a bribe, and that won't work with me. Good-bye, Mr. Laborian."

"Wait. I'm not offering you an electronic switch. I don't suggest that I place my financial card into a slot and that you do so, too, and that a hundred thousand globo-dollars be transferred from my account to yours. I'm talking gold, Mr. Willard."

Willard had risen from his chair, ready to open the door and usher Laborian out, but now he hesitated. "What do you mean, gold?"

"I mean that I can lay my hands on a hundred thousand globo-dollars of gold, about fifteen pounds' worth, I think. I may not be a multimillionaire, but I'm quite well off and I wouldn't be stealing it. It would be my own money and I am entitled to draw it in gold. There is nothing illegal about it. What I am offering you is a hundred thousand globo-dollars in five-hundred globo-dollar pieces—two hundred of them. Gold, Mr. Willard."

Gold! Willard was hesitating. Money, when it was a matter of electronic exchange, meant nothing. There was no feeling of either wealth or of poverty above a certain level. The world was a matter of plastic cards (each keyed to a nucleic acid pattern) and of slots, and all the world transferred, transferred, transferred.

Gold was different. It had a feel. Each piece had a weight. Piled together it had a gleaming beauty. It was wealth one could appreciate and experience. Willard had never even seen a gold coin, let alone felt or hefted one. Two hundred of them!

He didn't need the money. He was not so sure he didn't need the gold.

He said, with a kind of shamefaced weakness. "What kind of a novel is it that you are talking about?"

"Science fiction."

Willard made a face. "I've never read science fiction."

"Then it's time you expanded your horizons, Mr. Willard. Read mine. If you imagine a gold coin between every two pages of the book, you will have your two hundred."

And Willard, rather despising his own weakness, said, "What's the name of your book?"

"Three in One."

"And you have a copy?"

"I brought one with me."

And Willard held out his hand and took it.

That Willard was a busy man was by no means a lie. It took him better than a week to find the time to read the book, even with two hundred pieces of gold glittering, and luring him on.

Then he sat a while and pondered. Then he phoned Laborian.

The next morning, Laborian was in Willard's office again.

Willard said, bluntly, "Mr. Laborian, I have read your book."

Laborian nodded and could not hide the anxiety in his eyes. "I hope you like it, Mr. Willard."

Willard lifted his hand and rocked it right and left. "So-so. I told you I have not read science fiction, and I don't know how good or bad it is of its kind—"

"Does it matter, if you liked it?"

"I'm not sure if I liked it. I'm not used to this sort of thing. We are dealing in this novel with three sexes."

"Yes."

"Which you call a Rational, an Emotional, and a Parental."

"Yes."

"But you don't describe them?"

Laborian looked embarrassed. "I didn't describe them, Mr. Willard, because I couldn't. They're alien creatures, really alien. I didn't want to pretend they were alien by simply giving them blue skins or a pair of antennae or a third eye. I wanted them indescribable, so I didn't describe them, you see."

"What you're saying is that your imagination failed."

"N—no. I wouldn't say that. It's more like not having that kind of imagination. I don't describe anyone. If I were to write a story about you and me, I probably wouldn't bother describing either one of us."

Willard stared at Laborian without trying to disguise his contempt. He thought of himself. Middle-sized, soft about the middle, needed to reduce a bit, the beginnings of a double chin, and a mole on his right wrist. Light brown hair, dark blue eyes, bulbous nose. What was so hard to describe? Anyone could do it. If you had an imaginary character, think of someone real—and describe.

There was Laborian, dark in complexion, crisp curly black hair, looked as though he needed a shave, probably looked that way all the time, prominent Adam's apple, small scar on the right cheek, dark brown eyes rather large, and his only good feature.

Willard said, "I don't understand you. What kind of writer are you if you have trouble describing things? What do you write?"

Laborian said, gently, somewhat as though this was not the first time he had had to defend himself along those lines, "You've read Three in One. I've written other novels and they're all in the same style. Mostly conversation. I don't see things when I write; I hear, and for most part, what my characters talk about are ideas—competing ideas. I'm strong on that and my readers like it."

"Yes, but where does that leave me? I can't devise a compu-drama based on conversation alone. I have to create sight and sound and subliminal messages, and you leave me nothing to work on."

"Are you thinking of doing Three in One, then?"

"Not if you give me nothing to work on. Think, Mr. Laborian, think! This Parental. He's the dumb one."

"Not dumb," said Laborian, frowning. "Single-minded. He only has room in his mind for children, real and potential."

"Blockish! If you didn't use that actual word for the Parental in the novel, and I don't remember offhand whether you did or not, it's certainly the impression I got. Cubical. Is that what he is?"

"Well, simple. Straight lines. Straight planes. Not cubical. Longer than he is wide."

"How does he move? Does he have legs?"

"I don't know. I honestly never gave it any thought."

"Hmp. And the Rational. He's the smart one and he's smooth and quick. What is he? Egg-shaped?"

"I'd accept that. I've never given that any thought, either, but I'd accept that."

"And no legs?"

"I haven't described any."

"And how about the middle one. Your 'she' character—the other two being 'he's.' "

"The Emotional."

"That's right. The Emotional. You did better on her."

"Of course. I did most of my thinking about her. She was trying to save the alien intelligences—us—of an alien world, Earth. The reader's sympathy must be with her, even though she fails."

"I gather she was more like a cloud, didn't have any firm shape at all, could attenuate and tighten."

"Yes, yes. That's exactly right."

"Does she flow along the ground or drift through the air?"

Laborian thought, then shook his head. "I don't know. I would say you would have to suit yourself when it came to that."

"I see. And what about the sex?"

Laborian said, with sudden enthusiasm, "That's a crucial point. I never have any sex in my novels beyond that which is absolutely necessary and then I manage to refrain from describing it—"

"You don't like sex?"

"I like sex fine, thank you. I just don't like it in my novels. Everyone else puts it in and, frankly, I think that readers find its absence in my novels refreshing; at least, my readers do. And I must explain to you that my books do very well. I wouldn't have a hundred thousand dollars to spend if they didn't."

"All right. I'm not trying to put you down."

"However, there are always people who say I don't include sex because I don't know how, so—out of vainglory, I suppose—I wrote this novel just to show that I could do it. The entire novel deals with sex. Of course, it's alien sex, not at all like ours."

"That's right. That's why I have to ask you about the mechanics of it. How does it work?"

Laborian looked uncertain for a moment. "They melt."

"I know that that's the word you use. Do you mean they come together? Superimpose?"

"I suppose so."

Willard sighed. "How can you write a book without knowing anything about so fundamental a part of it?"

"I don't have to describe it in detail. The reader gets the impression. With subliminal suggestion so much a part of the compu-drama, how can you ask the question?"

Willard's lips pressed together. Laborian had him there. "Very well. They superimpose. What do they look like after they have superimposed?"

Laborian shook his head. "I avoided that."

"You realize, of course, that I can't."

Laborian nodded. "Yes."

Willard heaved another sigh and said, "Look, Mr. Laborian, assuming that I agree to do such a compu-drama—and I have not yet made up my mind on the matter—I would have to do it entirely my way. I would tolerate no interference from you. You have ducked so many of your own responsibilities in writing the book that I can't allow you to decide suddenly that you want to participate in my creative endeavors."

"That's quite understood, Mr. Willard. I only ask that you keep my story and as much of my dialogue as you can. All of the visual, sonic, and subliminal aspects I am willing to leave entirely in your hands."

"You understand that this is not a matter of a verbal agreement which someone in our industry, about a century and a half ago, described as not worth the paper it was written on. There will have to be a written contract made firm by my lawyers that will exclude you from participation."

"My lawyers will be glad to look over it, but I assure you I am not going to quibble."

"And," said Willard severely, "I will want an advance on the money you offered me. I can't afford to have you change your mind on me and I am not in the mood for a long lawsuit."

At this, Laborian frowned. He said, "Mr. Willard, those who know me never question my financial honesty. You don't know me, so I'll permit the remark, but please don't repeat it. How much of an advance do you wish?"

"Half," said Willard, briefly.

Laborian said, "I will do better than that. Once you have obtained the necessary commitments from those who will be willing to put up the money for the compu-drama and once the contract between us is drawn up, then I will give you every cent of the hundred thousand dollars even before you begin the first scene of the book."

Willard's eyes opened wide and he could not prevent himself from saying, "Why?"

"Because I want to urge you on. What's more, if the compu-drama turns out to be too hard to do, if it won't work, or if you turn out something that will not do—my hard luck—you can keep the hundred thousand. It's a risk I'm ready to take."

"Why? What's the catch?"

"No catch. I'm gambling on immortality. I'm a popular writer but I have never heard anyone call me a great one. My books are very likely to die with me. Do Three in One as a compu-drama and do it well and that at least might live on, and make my name ring down through the ages," he smiled ruefully, "or at least some ages. However—"

"Ah," said Willard. "Now we come to it."

"Well, yes. I have a dream that I'm willing to risk a great deal for, but I'm not a complete fool. I will give you the hundred thousand I promised before you start and if the thing doesn't work out you can keep it, but the payment will be electronic. If, however, you turn out a product that satisfies me, then you will return the electronic gift and I will give you the hundred thousand globo-dollars in gold pieces. You have nothing to lose except that to an artist like yourself, gold must be more dramatic and worthwhile than blips in a finance-card." And Laborian smiled gently.

Willard said, "Understand, Mr. Laborian! I would be taking a risk, too. I risk losing a great deal of time and effort that I might have devoted to a more likely project. I risk producing a docu-drama that will be a failure and that will tarnish the reputation I have built up with Lear. In my business, you're only as good as your most recent product. I will consult various people—"

"On a confidential basis, please."

"Of course! And I will do a bit of deep consideration. I am willing to go along with your proposition for now, but you mustn't think of it as a definite commitment. Not yet. We will talk further."

Jonas Willard and Meg Cathcart sat together over lunch in Meg's apartment. They were at their coffee when Willard said, with apparent reluctance as one who broaches a subject he would rather not, "Have you read the book?"

"Yes, I have."

"And what did you think?"

"I don't know," said Cathcart peering at him from under the dark, reddish hair she wore clustered over her forehead. "At least not enough to judge."

"You're not a science fiction buff either, then?"

"Well, I've read science fiction, mostly sword and sorcery, but nothing like Three in One. I've heard of Laborian, though. He does what they call 'hard science fiction.' "

"It's hard enough. I don't see how I can do it. That book, whatever its virtues, just isn't me."

Cathcart fixed him with a sharp glance. "How do you know it isn't you?"

"Listen, it's important to know what you can't do."

"And you were born knowing you can't do science fiction?"

"I have an instinct in these things."

"So you say. Why don't you think what you might do with those three undescribed characters, and what you would want subliminally, before you let your instinct tell you what you can and can't do. For instance, how would you do the Parental, who is referred to constantly as 'he' even though it's the Parental who bears the children? That struck me as jackassy, if you must know."

"No, no," said Willard, at once. "I accept the 'he.' Laborian might have invented a third pronoun, but it would have made no sense and the reader would have gagged on it. Instead, he reserved the pronoun, 'she,' for the Emotional. She's the central character, differing from the other two enormously. The use of 'she' for her and only for her focuses the reader's attention on her, and it's on her that the reader's attention must focus. What's more, it's on her that the viewer's attention must focus in the compu-drama."

"Then you have been thinking of it." She grinned, impishly. "I wouldn't have known if I hadn't needled you."

Willard stirred uneasily. "Actually, Laborian said something of the sort, so I can't lay claim to complete creativity here. But let's get back to the Parental. I want to talk about these things to you because everything is going to depend on subliminal suggestion, if I do try to do this thing. The Parental is a block, a rectangle."

"A right parallelepiped, I think they would call it in solid geometry."

"Come on. I don't care what they call it in solid geometry. The point is we can't just have a block. We have to give it personality. The Parental is a 'he' who bears children, so we have to get across an epicene quality. The voice has to be neither clearly masculine nor feminine. I'm not sure that I have in mind exactly the timbre and sound I will need, but that will be for the voice-recorder and myself to work out by trial and error, I think. Of course, the voice isn't the only thing."

"What else?"

"The feet. The Parental moves about, but there is no description of any limbs. He has to have the equivalent of arms; there are things he does. He obtains an energy source that he feeds the Emotional, so we'll have to evolve arms that are alien but that are arms. And we need legs. And a number of sturdy, stumpy legs that move rapidly."

"Like a caterpillar? Or a centipede?"

Willard winced. "Those aren't pleasant comparisons, are they?"

"Well, it would be my job to subliminate, if I may use the expression, a centipede, so to speak, without showing one. Just the notion of a series of legs, a double fading row of parentheses, just on and off as a kind of visual leitmotiv for the Parental, whenever he appears."

"I see what you mean. We'll have to try it out and see what we can get away with. The Rational is ovoid. Laborian admitted it might be egg-shaped. We can imagine him progressing by rolling but I find that completely inappropriate. The Rational is mind-proud, dignified. We can't make him do anything laughable, and rolling would be laughable."

"We could have him with a flat bottom slightly curved, and he could slide along it, like a penguin belly-whopping."

"Or like a snail on a layer of grease. No. That would be just as bad. I had thought of having three legs extrude. In other words, when he is at rest, he would be smoothly ovoid and proud of it, but when he is moving three stubby legs emerge and he can walk on them."

"Why three?"

"It carries on the three motif; three sexes, you know. It could be a kind of hopping run. The foreleg digs in and holds firm and the two hind legs come along on each side."

"Like a three-legged kangaroo?"

"Yes! Can you subliminate a kangaroo?"

"I can try."

"The Emotional, of course, is the hardest of the three. What can you do with something that may be nothing but a coherent cloud of gas?"

Cathcart considered. "What about giving the impression of draperies containing nothing. They would be moving about wraith-like, just as you presented Lear in the storm scene. She would be wind, she would be air, she would be the filmy, foggy draperies that would represent that."

Willard felt himself drawn to the suggestion. "Hey, that's not bad, Meg. For the subliminal effect, could you do Helen of Troy?"

"Helen of Troy?"

"Yes! To the Rational and Parental, the Emotional is the most beautiful thing ever invented. They're crazy about her. There's this strong, almost unbearable sexual attraction—their kind of sex—and we've got to make the audience aware of it in their terms. If you can somehow get across a statuesque Greek woman, with bound hair and draperies—the draperies would exactly fit what we're imagining for the Emotional—and make it look like the paintings and sculptures everyone is familiar with, that would be the Emotional's leitmotiv."

"You don't ask simple things. The slightest intrusion of a human figure will destroy the mood."