Erin M. Evans

Brimstone Angels

PROLOGUE

The village of Arush Vayem,

The Tymantheran frontier

21 Nightal, The Year of the Purloined Statue (1477 DR)

Farideh met the devil in the dead of winter, seventeen years after she’d been left at the gates of a village on no one’s map. It was the winter after she’d drunk too much whiskey for the first time, and four winters after she’d had her first heartbreak, infatuated with the dairyman’s much older son. Seven winters had passed since she’d first managed to swing a sword without dropping it.

And ten winters had blown through the village of Arush Vayem since she’d first realized that all of these things were bound to be heavy with other implications-all because she was a tiefling.

Farideh hugged the book she carried to her chest to make an extra layer against the frigid breeze that blew through her cloak and her clothes beneath. Her tail was nearly numb with the chill as she made long tiptoed steps to keep the drifting snow from crumbling into her boots, her eyes on the ground to keep her balance.

As she passed the well, she looked up from her feet, and her chest squeezed tight.

Not ten steps before her another tiefling, Criella, the village midwife and a priestess of the earth goddess, trudged up the same path. Bundled against the cold, Criella’s sawn-off horns were hidden and her brick red skin ruddier than usual. Suddenly conscious of her own unaltered horns, curling back from her face and uncovered, Farideh smiled nervously.

“Well met, Mistress Criella,” Farideh said, “and good morning.”

“Well met,” Criella said. Her smile hovered at the corners of her mouth, but her eyes were hard. She stopped in the middle of the path. “Where are you heading?”

“Home,” Farideh answered.

“Hm. Where did you get that book?”

Farideh made herself keep smiling, as if she couldn’t hear Criella’s implication that she ought not to have the book in the first place. “From Garago,” she said, naming the wizard whose book it was. “He lends books to Havilar and me sometimes.”

“Havilar and I, dear.” Farideh bit her tongue as Criella continued. “And where is your sister?”

“Inside, probably,” Farideh said. Criella pursed her lips, and the younger tiefling quickly added, “I haven’t seen her in some hours. She’s likely with Mehen.”

“Does Mehen know you’re borrowing magic books?” Criella asked.

Farideh turned it over and opened it to show the frontispiece. “It’s just a history book.”

“The Legacy of the Skyfire Emirates in the Calim?” Criella said. “What has you so interested in there of all places?”

Far, far to the west, other tieflings sometimes joined the fiery efreets in the Calim Desert in their perpetual war against their enemies, the djinns of the air. Criella didn’t have to say another word-Farideh knew what she was implying: Why was Farideh reading a book about rogue tieflings who aided monsters and known slavers? Didn’t Farideh understand that she-just like everyone else descended from devils and fiends-had to know her place, to stay safe somewhere like Arush Vayem, to be quiet and unnoticeable?

Or did Farideh want to be the sort of tiefling who made life hard for the rest of them?

“Mehen was talking about the wars there.” Mehen, a dragonborn and a soldier in his life before Arush Vayem, had been the guardian of Farideh and her twin sister, Havilar, since they were abandoned at the village gates. More than a few of Havilar and Farideh’s childhood bedtime stories had been sweeping, gory tales of battle. If he hadn’t talked about the Calim, it was the merest coincidence.

“Was he?” Criella said.

“He mentioned them,” Farideh amended. “It seems like such a silly thing, don’t you think? For so many hostilities to range around something as unchangeable as one’s nature?”

Criella’s smile vanished altogether. “Ah. Is that something else Mehen has taught you?”

Farideh flushed. “That … the djinn shall always be djinn?” she said as innocently as she could, but her pulse raced. It had been too near to admitting there was something like fear lurking in herself. That the lines of descent that linked her to some long ago and faraway fiend were more powerful than anything she could affect. “I believe that’s why they’re called elemental,” Farideh added.

“Of course,” Criella said, but already she was studying Farideh as if there might be some sign of her true nature unfolding. Farideh blushed harder. Any of the human villagers would find Criella’s scrutiny too subtle to notice. But Farideh’s eyes were like Criella’s-she knew the shifts and flickers of a tiefling’s eyes. Criella wasn’t trying to hide her disquiet.

Farideh longed to tell Criella that she knew. That she hated it. That it was worse coming from someone like Criella, who was a tiefling too. Who had gotten the same scrutiny from someone else when she was Farideh’s age. Who had cut off her horns and clubbed her tail because of those looks and run away to Arush Vayem, a community of tieflings, dragonborn, and anyone else who wanted to disappear.

A prison and a refuge, Farideh thought. The wall around the village-the wall that kept out the monsters of the mountains, raiders and scouts, the hordes of people who hated Criella and the others enough to drive them to a place like Arush Vayem-might as well have been a circle of armed warriors, half their weapons pointed inward.

“Blood is a powerful thing,” Criella said, her eyes burning into Farideh, “though it is always within our power to circumvent it. If we are vigilant.”

“Criella.” The gruff voice behind Farideh made her jump. Criella looked up, and her surprise at seeing Mehen standing there was as plain as her contempt for his foster daughter. He might have weighed as much as a small ox, but Mehen could move with a silence not even Farideh could predict. She shifted out of his way.

Mehen stood a full foot taller than the already tall and gangly tiefling girl, his scales a dull ocher over hard muscle, and the frill along his jaw full of holes where he once wore the jade plugs that had marked his clan. Those rested now in a small enameled box Mehen kept in his room. He did not discuss them with Farideh or Havilar.

“Well met,” Criella said. “Farideh was just telling me about her interest in the Skyfire Emirates.”

“Is that right,” he said. He looked down his snout at Farideh. The way Mehen looked at Farideh made her suspect he never quite knew what to do with her. She was not like Havilar, who would have polled her own horns like Criella had it meant she could be a warrior of Mehen’s skill.

But even if she was not his favorite, Mehen would surely not take Criella’s side.

“It’s a history book,” Farideh said again. She knew Mehen’s expressions too-well enough to spot the shift of a scaly ridge that registered his annoyance at Criella.

“Good,” he said. “The genasi’s tactics are blunt, but it’s good to know your enemy.” He smiled at Criella, and she drew back at the row of sharp, yellowed teeth. “Run along,” he said to Farideh, “and get inside. You’ll freeze to death in this weather.”

“Yes,” Criella added. “I was about to say the same.”

Farideh bobbed her head meekly over the edge of the book.

She wanted to tell Criella, “I know you’re thinking I’d be lucky to freeze. I know you’re thinking my blood runs hot as the Ninth Layer of the Hells and we’ll all find that out soon enough. I know you’re thinking that with twins, one of us is bound to turn out rotten, and your coin’s been set on me.”

“Good morning, then, Mistress Criella,” was what she did say.

She had no more than rounded the corner before Mehen and Criella started talking again. “You had best set them to a profession,” Criella said. “They’re too old to be running wild.”

“They’re young enough,” Mehen said. “And I’m training them fine. We need defenders.”

“That girl is going to be no one’s defender and you know it,” Criella said. “Everyone knows it. Better to put up scarecrows than to send her on patrol.”

“No one was hurt.” But Farideh heard the embarrassed tone in Mehen’s voice. Havi could be sent on patrol, but not Farideh. Not so long as she jumped at martens and couldn’t keep hold of her sword.

“She’s a bright girl,” Criella said, “but she has a smart mouth and she’s too clever by half. Give her to me. I need an apprentice, and a few years of devotion to Chauntea should wear her …”

Farideh hurried down the lane, her face hot despite the cold wind. She didn’t need to hear the rest of Criella’s offer-the priestess had hinted at it often enough to Farideh-and she couldn’t bear to hear Mehen’s reply. Determined as Mehen was to keep her home and training, Farideh wasn’t sure which fate was worse.

But she would have to choose. There wasn’t much else open to her within the village’s walls, and Farideh knew better than to dream of a future she couldn’t have.

Farideh picked her way up to the ancient stone barn that had been converted, long before she’d been born, into a house for the dragonborn veteran and, later, his foundling daughters. By the time she stomped the snow off of her boots, she had forgiven Mehen, as she always did, but Criella knew just how to get under her skin.

She wasn’t the kind of tiefling Criella thought she was. She started to unwind the scarf from her neck and looked up into the room. Maybe Criella was right. Maybe she ought to keep her head down and stay here, so that people didn’t think …

The flutter of her thoughts ceased.

Her twin sister, Havilar, sat on the floor, her long legs stretched out in front of her, resting back on her arms. She was looking up at something standing in front of her.

No. Not something, Someone.

The devil was standing-waiting-in a circle of chalk runes that Havilar had drawn on the ancient oak planks of the floor. If Farideh looked at the runes, she would have known their names, but she could only look at him.

Someone else might have said he looked like an archdevil out of one of Garago’s books. He did-red-skinned, cinder-haired and black-eyed, handsome as a young lord, with shapely horns and a pair of veiny wings that nearly scraped the ceiling of the loft he stood below. He was slim and well-muscled and clothed in snug leather, with rings on every finger and charms pinned wherever they could find a place.

But to Farideh, he looked like sin. He looked like want. He looked like all the thoughts she couldn’t let herself have, bundled up in a skin and watching her drip snowmelt on the floor.

Handsome was a paltry word for him. Tiefling, human, or anything else-boys didn’t look like this. Boys didn’t make her feel as if someone were pulling seams loose inside her. He smiled, and his teeth were so like hers-even but for the sharp points of his canines that were too large by human standards, and pitiable by dragonborn. She had never thought so looking at her own teeth, but the devil’s looked like a wolf’s. Like something ready to take a bite of her.

The book slid out of Farideh’s hands.

Havilar nearly jumped out of her skin when it hit the floor. When she turned and saw Farideh, she clasped a hand to her chest and let out a sigh. “Karshoj, you scared me.”

“Oh Havi,” Farideh breathed. “What have you done?”

A grin split Havilar’s face-a face that was in almost every respect identical to Farideh’s, save two: First, where Havilar’s eyes were both golden, Farideh’s right was silver and always had been. Second, Havilar was much more likely to be grinning. People called her “the cheerful one,” and sometimes “the wild one.”

The one I am always chasing after, Farideh thought.

“Isn’t he marvelous?” Havilar said, though by the tone of her voice, Farideh could tell that the devil with his black, black eyes didn’t have the same effect on Havilar at all. “The spell was supposed to call an imp,” she said, “but I must have gotten lucky. He’s a cambion. Half-devil,” she added. “And people say you’re the smart one.”

“No one says that,” Farideh said, forcing herself to look away, to look at her sister. But still she could feel the cambion looking at her. “Listen to me: This isn’t lucky. This is very bad. You have to send him back-right now.”

“You’re such a worrywart. He’s safe. He can’t harm anyone as long as he’s in the circle and look-” She turned and made a series of rude gestures at the cambion. He regarded her with the same mild smile. “He’s locked right in. He can’t do any harm.”

He can, Farideh thought. He is. She felt as if her mind were slowing down, as if her tongue were turning to clay. “Send him back. If anyone finds out you’ve summoned a devil-”

“I’m not sending him anywhere until Mehen has seen him. Maybe you won’t be the smart one forever. This is a hundred times better than that dire rat he had me trap.” She pulled off Farideh’s scarf the rest of the way and wrapped it around her own neck. “Here, you watch him for a minute.”

“What? I can’t! You can’t leave me-”

Havilar took up Farideh’s cloak as well. “Yes, you can. Just don’t mar the circle. That’s important. Probably.”

“Wait!” Farideh said, but Havilar was already out the door and into the snow.

Leaving Farideh alone with a devil who looked like walking sin.

He stood there-quiet, still, watching her intently. The silence felt so fragile, as if the slightest breath would shatter it. She thought of Criella’s concern, of the fiendish blood undeniably coursing through her veins, ready to make her do something foolish. Or dangerous. For a long time she didn’t dare move.

But then, neither did the devil. The circle-despite the fact that Havilar shouldn’t have been able to do anything of the sort-was holding. He was only standing there.

She told herself to relax-she wasn’t going to talk to him, she knew better than that, Criella was wrong-and bent down to pick up the book.

“You’re not like that one,” the cambion said.

Farideh lost her grip on the book and dropped it again. She stared up at the devil, but he was still standing there, still trapped in the circle. “What?”

“You are not like her,” he said. His voice slithered into her ears and Farideh shivered. She scooped up the book and held it to her like a shield.

“I … I thought you weren’t supposed to talk,” she said.

“I’m not able to do any harm,” he said, “and what harm is talking?” He smiled again, as if he knew what Farideh had been thinking before. “You’re not like her,” he repeated. “Like night and day. Like sweet and sour. Like the ocean and the desert.” He tilted his head. “It’s astonishing.”

Farideh flushed. “I don’t know what you mean by that. We’re twins. We’re alike tip to toe.”

The cambion tapped a finger below his right eye, the same eye as Farideh’s silver one. Farideh’s flush burned hotter.

“It’s only an eye.”

More than an eye though. Even the dragonborn who refused to see fate or the hands of the gods in anything, touched the hafts of their weapons when they spied her odd eyes. Bad enough to be a tiefling, the descendent of humans and fiends; worse still to be marked like that. If she’d come by it honestly-she knew they thought-by a blinding stroke, it would be one thing … but nothing normal was born with two-colored eyes.

“It’s a very clever eye,” the cambion said. “Both of them are. They see things your sister’s don’t.”

Farideh scowled at him. “It’s just an eye. It can’t see invisible doors. No spell-hidden creatures. No silver pieces in your ear-”

“Of course not,” he said, and like that, the wheedling tone was gone. “But you do see the way people look at you, devil’s child.”

Those black eyes, cold as a winter storm, were staring right into her heart and the sudden seriousness in his voice jolted her.

“What is it they say?” he asked. “One’s a curiosity, two’s a conspiracy-”

“Three’s a curse,” she finished. “You think I haven’t heard that rubbish before?”

“I know you have.” When she glared at him, he added, “It’s not as if I’m plumbing the depths of your mind, dear girl. That is the burden of every tiefling. Some break under it, some make it the millstone around their neck, some revel in it.” He tilted his head again, scrutinizing her, with that wicked glint in his eyes. “You fight it, don’t you? Like a little wildcat, I wager. Every little jab and comment just sharpens your claws.”

“I …” Farideh realized she was doing exactly what she had sworn not to do, and took hold of the book, crossing over to the shelves on the opposite side of the barn. So he was right-as he said, it wasn’t hard to guess. She slid the tome onto the shelf.

“Who could blame you?” the cambion went on. “Who wants to be held responsible for something they can’t control? Turned away because of something their foremothers and forefathers did to gain a little power?”

She was trying, but gods, he was prodding her in sore spots. “What do you know about my foremothers and forefathers?” she said. She kept her eyes on the spines of the books. “Maybe it was power that made them cross with devils, or maybe they didn’t have much choice. Maybe it was for some … greater good. Maybe it was love.”

The cambion broke into raucous laughter, and she felt herself flush.

“Ah! Is that what they tell you?”

“They … It just might have been that way, that’s all.” She looked back over her shoulder. “You weren’t there.”

A smile twisted the cambion’s lips, and Farideh blushed again. She’d been staring at his mouth. “Of course. All those mortal women swooning over gallant pit fiends. All those golden-hearted succubi blushing as men kiss their burning hands. My darling, let me tell you a secret: devils don’t love.”

Farideh looked at the door. Havilar would be back any minute, and with her, Mehen. Mehen would tell Havilar what a stupid thing it was to call a devil and make her send him back. Or maybe he’d just pull out his falchion and slice the cambion in half.

When she looked back, the devil had taken a few steps closer to her, still toeing the edge of the circle of runes. She was still a good eight feet away, but there was nothing between them, and she was very aware of those eight empty feet.

“You’re a half-devil,” she said. “So if it’s all about power, who wanted it there?”

His smile twitched, and for a moment she wondered if he had sore spots of his own. “Nobody. Least of all my father.”

“Is he the devil?”

“No, that would be my mother,” he said. “Invadiah, the fiercest erinyes of the Lady of Malbolge.” There was a sour note to the way he said it.

Farideh didn’t know what an erinyes was, but she suspected Criella would tell Mehen to keep a tighter rein on her if she did. Malbolge was the name of one of the Nine Hells. Her sense of dread deepened, though she pushed it aside. He was a devil-of course he came out of the Hells. He was still trapped in a circle Havilar made.

“What’s your name?” he asked.

“Farideh,” she said.

The cambion clucked his tongue. “Anyone ever tell you, Farideh, that there’s power in names?”

“You told me your mother’s name pretty easily,” she replied.

“True enough,” he said. “And I’ll even tell you mine, since I know you want to hear it. It’s Lorcan.”

“Well met,” she said, and instantly felt foolish.

“Better than you think,” he said. “We’re even now. You can see I’m not like the others.”

“What others?”

“Why, the ones who judge you,” he said, with a wide gesture at the world beyond. “The ones who wait for you to fail.”

“There’s no one like that here,” she said, even though that wasn’t true. Criella. The dairyman, the blacksmith’s apprentice, the tinkers, and others. They thought they were hiding it, but they watched her when they thought she wouldn’t notice, gauging her, waiting for her true nature to burst forth like a bud coming to poisonous bloom.

“So is that what this is?” Farideh said, hotly. “You’re going to try and convince me to … to … what? Kill my neighbors? Corrupt them? I’m not going to-”

“Heavens to Hells, you’re an excitable one,” Lorcan said. “How old are you? Sixteen?”

“Seventeen.”

“All but grown,” he said. “Regardless, you’re smart enough to know better than to do something just because I said it, I’d wager. I would have had an easier time snatching up your sister if I were that sort of fiend. I’m only here to help.”

“I thought you were here because Havilar called you.”

“And I came,” he said, “because I wanted to help.”

“You can’t help me.”

“Oh? It doesn’t take a seer to work out how your life will go.”

Farideh shook her head again, as if she could stop listening to him. Leave, she told herself, leave now. She started toward the door.

“You’ll live in this village for all of your life,” Lorcan said, keeping pace with her along the border of the circle. “You’ll spend every day trying your hardest to be what they want, and you’ll never meet their expectations, because you were not made for this. You will always be their burden, the creature that turned up at the gates in swaddling.”

Farideh stopped. “How do you know that?”

He smiled. “Your sister told me. They love her, don’t they? But only so long as you keep after her, cleaning her messes and making sure no one realizes that she’s causing so much trouble.”

“Havi’s not trouble.”

“No,” Lorcan said, with a chuckle. “She’d never do something foolish like summoning a devil because she thought it would be fun.” Farideh bit her lip. “If you’re lucky you’ll succeed and she’ll be safe. If you aren’t-and darling, no one’s that lucky-one day you’ll slip, you’ll miss, and she’ll undo everything you’ve worked your entire life to protect. They’ll throw you out of this village and into the real world. She’ll never see it coming because Havilar believes that people are good and they’ll always love her and there’s nothing wrong with playing along the lines of their expectations. Whoever finds her first will take her head if she’s lucky. At least that way’s quick.”

As he spoke, Farideh saw the village, angry and afraid. A garrote, a chopping block, or an angry mob. Soldiers from somewhere else. Warrior-priests on horseback. Gods, it could come a thousand different ways. She’d heard it a thousand different ways from the villagers. Her blood would melt the snow …

“I wouldn’t let that happen,” she said. Tears choked her voice.

“Doesn’t matter,” Lorcan said. “It’s an unhallowed grave, unmourned and alone for the both of you. There’s no escaping that, no matter how perfect you are.”

There isn’t, Farideh thought-she’d always known that, hadn’t she? Hard as she tried to be good, no one trusted her.

“I can help you, you know,” Lorcan’s crooning voice slid through her worries. “Simple as it comes. No one will ever hurt you. No one will ever hurt her either.”

“No,” Farideh said, though her thoughts felt slippery and loose. She covered her eyes and ducked her head. “No. Go away.” Stay, she thought. Tell me.

“It’s a simple thing,” he said again. Lorcan set his hand, hot as an iron, on the bare spot between her shoulder blades, his fingers sliding just under the edge of her collar. “Not like what they tell you. Just say you’re mine. That’s all it takes.”

“No.” She couldn’t. It would be everything she wasn’t supposed to …

“You’ll have the power to do as you please. You’ll have the power to stop them. I’ll give you everything and all you have to do is take it. Take the power. Say you’re mine.”

“No,” she said, though her voice was growing fainter and her head was spinning. Why would she say no? She would be safe.

“No one touches a burning coal-and that’s what you’ll be, my darling, something so hot and bright and dangerous they dare not lay a hand on you. Someone tries to harm Havilar and you will stop them. Someone tries to deny you what you truly deserve, you will show them their folly. Anyone comes to this village, looking for anyone who doesn’t want to be found …” He trailed off.

She could not open her eyes now. “Yes?”

“You will be their savior,” he whispered in her ear. “Tell me you don’t want that?”

“I …” Farideh faltered. “I do.”

“Free. Free to do as you please. Free to find whatever life you want.” He pulled her close, very close. “Free to stop those who would hurt the innocent. Hurt your friends. Hurt Havilar.” His breath burned against her skin. “You want that, don’t you?”

“Yes.”

“You want me to give you that power?”

“Yes.”

“You want to be mine?”

“Yes,” she said, and with that her thoughts seemed to clear: He’s out of the circle.

Farideh looked up in horror at the cambion, whose arms held her like an iron band. “No!” she cried.

“Too late, darling.” He whispered in her ear, “It wouldn’t have held the imp either.”

Then everything caught fire.

Farideh woke to someone calling her name. There was a smell of burned wood and a chill breeze blowing over her skin. She opened her eyes to a heavy black snow swirling through the sky.

Not snow, she thought. Ashes. Fat black ashes. Like burnt paper.

She started to sit up and someone grabbed her arm. Havilar. She looked up at her sister, whose cheeks were streaked and spotted with a slurry of tears and clinging cinders. Beyond, the village-the whole village of Arush Vayem-stood, watching from a distance of a good twenty feet. Between the twins and the villagers, the ground was a flat stretch, cleared and charred as if something had exploded, burning away the grass and snow and … what else had been there? Mehen stood in the middle, his falchion out and ready. But he was facing the villagers.

They’re angry, Farideh thought muzzily. Something …

She remembered the stone barn and the cambion. Her breath sped up. Her nerves rattled with fear and pain and she realized her shoulder was screaming, and her dress had been torn open on that side.

From her collar to her elbow her golden skin had been branded with an elaborate design. She stared at it a moment and the lines seemed to form a flail. A flail and a smattering of lines that looked like a whirlwind. She touched it gingerly-it burned like a fever.

“Oh Fari,” Havilar whispered. “What have you done?”

The time between waking in the wreckage of her home and finding herself sitting in the dark beside a campfire, somewhere in the foothills of the Smoking Mountains passed in a blur. She remembered shoving half-burnt things into a haversack. She remembered Mehen cursing the villagers in a string of Common and Draconic, blowing out a fork of lightning breath when the blacksmith’s apprentice got too near. Criella shouting. Everyone shouting. Farideh had to leave. If Farideh was leaving then so was Havilar, if Havilar and Farideh were leaving, then so was Mehen, and damn them all and karshoji Tiamat come down on them. She remembered Havilar clinging to her arm with one hand and her glaive with the other, as if the two were all that could anchor her in the world. Mehen leading them up a mountain trail, muttering to himself in Draconic-they could not go to Tymanther, but where else could they go? The Black Ash Plain lay to the south, riddled with giants and their kin. The great Underchasm split Faerun to the west. To the north lay Chessenta … and if Farideh’s burn meant what he thought …

The lines that laced her shoulder were red and oozing. They ached. They itched. Worse, they pulled, as if the burn were a tether and something was holding the other end.

Mehen settled a blanket over her shoulders. “You should go to sleep,” he said gently. Havilar was already fast asleep, sprawled facedown with her horns curling back from the ground.

“I’m not tired,” she said, hardly above a whisper. Her throat ached from the effort of not crying. She couldn’t-not after all she’d done.

He was silent for a moment. “We’ll be all right.”

Farideh nodded, though she couldn’t see how.

“Farideh,” Mehen said. She looked up. “Trust me. I’ve done this before.”

“And so we can’t go to Tymanther,” she said dully.

Mehen snorted. “There’s a lot more world than Arush Vayem and Tymanther. We’ll make our way, take bounties or serve as guards. We’ll find someone to help you get rid of that pact, and we can come back.”

Farideh pulled the blanket close. “You know we can’t.” She squeezed her eyes shut. The cambion had been right. One mistake, and she was as good as dead.

Fine-if that was how the world was going to treat her, perhaps she’d just keep whatever the cambion offered, and to the Hells with them all. If they all thought her damned, better to damn herself right.

The thought frightened her, but there it was.

Mehen was watching her. “If you’re not going to sleep, keep watch. Wake me when you’re tired. Or if you hear anything.”

Farideh doubted she would ever be tired again. Once Mehen had gone to his own bedroll and dropped off to sleep, she let herself weep quietly into her hands.

“What on all the planes are you crying for?” a voice said. “You’re much better off now than you were.”

She froze like a rabbit before a wolf, looking up at Lorcan silhouetted in the firelight. He was still ferociously handsome, still unspeakably fiendish, and this time there was no circle-not even a broken, haphazard one-to separate them. Havilar and Mehen slept on.

“Are you here to take my soul then?” she said quietly.

Lorcan burst into laughter. “Oh, Glasya skin me, that’s adorable. No, I’m not here to harvest you. We have an agreement, and I’m here to see to that.”

“Oh.” She wondered what exactly it was she had bargained away in the heat of the moment and the tangle of his pretty words. “But you will? Is that what this is?”

“Dear girl,” he said, “the king of the Hells’ own blood runs in your veins. A soul was never a certainty for you. I’d suggest you stop worrying about it.”

“So I am doomed,” she said. “And you are here to take me.”

“There you are again,” he said, with a shake of his head, “being melodramatic. I’m merely giving you some perspective. That isn’t the sort of deal we’ve made at all.”

“You’re talking in circles again,” she said.

“My darling, I already told you: If all I wanted was a petty little soul, there were dozens I could have snapped up quicker and neater than yours.”

She pulled the blanket closer around her shoulders. “Then what do you want?”

“A warlock.” He stepped closer. “You, in particular, as my warlock.”

She shook her head. “I don’t … I don’t know what you mean.”

He gave her a dark look, as if she were being deliberately obtuse, but she could only shake her head again. Lorcan sighed. “It means you’re bound to me. For the pleasure, I grant you powers. Powers you seemed to dearly want, before.”

“Spells?” she asked. “What … what do I have to do?”

“Nothing. You’ll find it’s much simpler than other sorts of spell-casting. Now,” he said, his eyes gleaming in the firelight, “do you want a taste of what you’ve purchased?”

She shifted uncomfortably. “I don’t know that I do.” And he wasn’t telling her what she’d purchased those powers with, she couldn’t help but notice. “Why me?”

He shrugged. “Call it a whimsy of my character. I have certain preferences for my warlocks.”

“Warlocks?” she said, emphasizing the plural.

“You aren’t exactly my first,” he said with a chuckle.

Farideh started to ask him who the others were-whether they, too, were caught in the net of their own fears and wants, whether they were afraid of him, whether they were pretty-and stopped herself. She didn’t want to know.

He set his hands on his hips. “Come now,” he said after a moment, “what are you thinking?”

“That you don’t seem dangerous,” she admitted. “Which makes me suspect you are very dangerous.”

“I hope that is not a logic you apply to your everyday life.”

“No,” Farideh said. “Just devils … and the like.”

“I’m only half a devil.”

“That’s enough like a devil.” Her voice hitched, and she pressed a hand to her mouth, willing herself not to cry again. But it was too much and the tears overcame her.

“Oh Hells,” he said, holding out a hand, “come here.”

She didn’t know how he snatched her wrist away from the layers of the blanket, how he pulled her free of it and to her feet, but as soon as she realized he was moving and she should stop him, Lorcan had her tucked against him, her back pressed to his chest, his arms wrapped around her.

“You’re freezing,” he commented. Fortunately he was warmer than the fire.

She stiffened, and kept her eyes resolutely on Mehen’s sleeping form. “What do you think you’re doing?”

“Proving you haven’t doomed yourself. Really, I’m a pleasant enough fellow if you give me a chance.”

She was sure in her heart of hearts that Lorcan would say anything if it meant she’d stay bound to him. But that night, far from home and far from any future, she was still seventeen, still a girl, and still desperately lonesome. She stayed where she was.

“Why me?” she said. “You said … ‘the king of the Hells’ own blood.’ Is that why?”

“All tieflings have the blood of Asmodeus,” he said. “Regardless of who first dirtied the well. An effect of the ascension-it’s terribly boring. Don’t worry about it.”

Farideh pursed her lips. “I don’t like people telling me what to think.”

“Fascinating. How do you feel about people telling you what to do?”

He snatched up her hands in his own. Her breath caught-her double concerns twining over each other. She’d heard stories enough of people who lost their souls by not paying close enough attention to canny devils.

But at the same time no one had ever grabbed her hands like that. Lorcan’s hands were strong, and she found herself considering how much larger than hers they were.

If he held tight, she didn’t think she could break away.

“Close your eyes,” he said.

She gave a little shake of her head. She didn’t want to, and yet she did. She wanted to see what he was going to try-it wasn’t as if anyone had tried anything on her-but she wasn’t a fool and she knew he was up to no good.

“Close your eyes. Think about your burn,” he said. “And think about the world.”

“The whole world?”

“Yes. Think about Toril.”

Tempted, Farideh tried, but it was like trying to think about how to walk or how the color yellow looked-Toril was Toril. She opened her eyes.

“I don’t know how-”

“Stop talking,” he said, “and concentrate.”

Farideh closed her eyes again, and instead, thought of the ground. The way it felt to stand solid and to spread her weight between both feet in one of Mehen’s fighting stances. She thought of the cold, dry air and the wind that stirred the snow over the solidness of the mountains. She thought of the sun and Selune looking down at her, and the color of the moon goddess’s light on the rocks and the snow. The stillness of the cold winter night and the sound of the breath through her nostrils and the heat and pop of the fire.

And the burn-no, she thought, not burn. Brand. Lorcan could call it whatever pleased him, the lines that laced her shoulder were more than a burn. Tieflings didn’t burn easily-she and Havilar had scared Mehen enough times, snatching dropped bits of bread or meat right out of the flames, quick enough that they didn’t feel a thing. Only setting fire to their sleeves now and again.

But this burn, this brand, was no more a part of Toril than Lorcan was. Farideh knew that all the way to her marrow. The way it pulled at her, the way it still ached after hours and hours and Mehen’s ministrations. The brand was something magical, and it tied her to Lorcan.

And something tied him to someplace … else. If she let her thoughts drift along the bindings, she could sense another world beyond Toril.

The Nine Hells.

Farideh swallowed hard and opened her eyes.

“You’ve noticed,” Lorcan said.

She nodded, not wanting him to be a devil, not wanting him to be a monster. Not wanting to have said anything to him in the first place, if she could just wish for things to be true, so that she wouldn’t be standing there, as unsafe as she could be.

Lorcan let go of her hand and traced the lines of the brand peeking through her hastily mended dress. “This mark is what connects you to the powers of the Hells. Well,” he amended, “rather it’s what lets you channel them. Through me. Easier than spellbooks.”

“Does it hurt?”

“You’ll be fine.”

She looked back over her shoulder. “I meant you. Does it hurt you?”

He smiled-such a wicked, wicked smile. “I’ll be fine too. Here’s your first lesson.” Lorcan took her hands up again. “Think about that connection. You were close. You felt the power.”

She still could-it was like a primed pump, waiting for someone to grab hold of the handle and start it flowing. And it seemed to want her to grab hold of it, as if it were aware, as if it wanted to flow through her.

“What will it do?” she asked.

“Nothing,” Lorcan said, “unless you take hold of it.”

She opened her eyes. “Is this how you’re going to take my soul?”

He sighed. “Lords. If I promise to leave your soul alone for the time being will you just do what I say?”

Farideh laughed bitterly. “What’s your promise worth?”

“Plenty,” he said, sounding affronted. “I’m not some demon or something. I keep my word.”

“You lied about the circle.”

“I didn’t lie. I wasn’t forthcoming. There’s a difference. And I give you my most solemn word that you can keep whatever semblance of a soul you’ve managed, devil-child-unless you want to give it up-if you just do what I say.”

“For now,” Farideh added. “If I do what you say for now.”

He chuckled again. “You are terribly melodramatic. For now.”

Farideh hesitated again, sensing the power lying just out of reach. It seemed, she thought, to be only a part of something larger, a fraction of the Nine Hells, and still it was vast and roiling. She wondered if she managed to open that channel wider, like the breaking of a dam, if it would surge through her and Lorcan and kill them both.

“You know,” Lorcan said, “you are bound to come up against bandits. Or monsters. Or just people who don’t like the look of you. Maybe those neighbors of yours will decide you need more punishment than just banishment. This will help. For all I’m sure your dragonborn has trained you with a sword, you’re not practiced enough with it.”

“How do you know that?” she asked.

He rubbed his thumb over her palm in a slow circle. “Calluses. Your hands are far too smooth.”

She blushed to the roots of her hair.

Later, Farideh would think if anyone ever asked her about that night, she would need to invent a story-something where she acted because she was prideful and thought she could handle what she should have known she could not; or because Lorcan was clever and she was grief-stricken and foolish; or because she was forced against her will to grasp the powers of a warlock.

Anything, she would think, is better than the truth-that I reached for the powers of the Hells so I wouldn’t have to think of something to say to the half-devil stirring up my blood in ways I didn’t want to think about anymore.

The power poured into her, like slick, dark water filling a basin, and churned through her, stirring through every vessel, every part of her.

“Say adaestuo,” Lorcan said.

She opened her eyes. “Adaestuo.”

The power seemed to burst into being in the air before her mouth and, channeled by her outstretched hands, streamed across the clearing and exploded against a fir tree with a sickly violet light.

Farideh stared, agape, at the force of it. The wood had splintered and charred where the blast had struck it, and embers of purple light still scintillated at its edges. A single word and she’d blown off a piece of the tree nearly as large as her head.

She might never please Mehen with her sword work, she might never rival Havilar’s skill with her glaive, but this … this was breathtaking.

It was also loud. At the explosion, Havilar sat bolt upright. Mehen did not wake so much as materialize on his feet, falchion in hand. His eyes went straight to the tree, with its ring of strange, purplish embers … and then followed the path of the blast back to Farideh, her hands in Lorcan’s.

She tried to leap away, to put as much space between her and the cambion as she could, but she couldn’t move. Lorcan had folded his arms around her, as if this were nothing, as if no one were watching, as if Mehen weren’t advancing on him with his bare blade.

“You were made for this,” he whispered, and kissed her, just under her cheekbone. He vanished, and Farideh lost her balance and fell to the ground under the astonished stares of her sister and guardian.

CHAPTER ONE

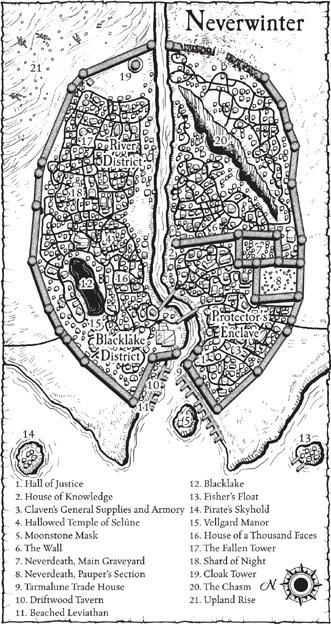

The high road, two days south of Neverwinter 10 Kythorn, the Year of the Dark Circle (1478 DR)

(six months later)

The wagon limped along the high road more slowly than Brin could have walked, but after well over a month, he was tired of walking. To be honest, he was tired of wagons as well, and ships and horses too. He was tired of moving, and the call from the lead wagon that the caravan had reached the city of Neverwinter couldn’t come soon enough.

Brin watched the road behind them, stretching on beyond another four lumbering carts of former refugees returning to rebuild the city that had fallen nearly a quarter century ago. He did not see-as he feared-the cloud of dust on the horizon that half-a-dozen knights on chargers would kick up as they pelted along the dirt road.

This didn’t calm him the way it should have. In fact, the longer he didn’t see any sign of his cousin, Constancia, the more he worried she was just behind the last hill, ready to grab him by the ear and haul him home. He looked up at the clouds hanging in the blue summer sky and wondered if he had made an enormous mistake.

Constancia would say so: It was irresponsible. It was foolish. It was possibly illegal. And why, she would ask, by the lions of Azoun, Neverwinter?

The call had gone out halfway across the continent that the Open Lord of Waterdeep was rebuilding Neverwinter out of its shattered ruins, and all her citizens-and their descendants-were encouraged and invited to return. Among the thousands of people filtering in through the city gates, no one would notice one more boy.

And there was the city’s history-the famed clockworks and fanciful buildings, the artisans whose creations were still prized-that had caught Brin’s attention. And the catastrophic death of the city by earthquake and volcano, that had held it.

But perhaps most of all, it was far enough away that no one would know who he was or what he’d done or what he might have done if things were a little different-

“Is something troubling you?”

Brin looked up at the man sitting beside him, who had also paid the cart’s owner to carry him to Neverwinter.

“No,” Brin lied. “Just thinking.”

The man was a Calishite, perhaps in his forties or fifties, slim and muscular. The threads of gray in the man’s hair might as well have been ornaments and the crinkles in his brown skin, paint for all he wore his age. He smiled, one corner of his mouth crooked by a small scar where something had once cut the skin deeply. Brin wondered how someone came by a scar like that, and his eyes strayed briefly to the chain the man wore wrapped around his waist like a belt.

The man gave Brin a look that Brin was accustomed to getting from adults, down his broken nose, as if the man knew very well that Brin was lying. He nodded at the flute Brin wore tucked into his own belt. It was the only thing Brin had taken that he didn’t strictly need. It had been his father’s.

Brin’s hand tapped the holes of the flute.

“You seemed nervous,” the man said. “Do you play?”

“Oh,” Brin said. He set his hand back down on the cart bed. “Yes.”

“But you’re not a musician?”

“What makes you say that?”

The man shrugged. “You haven’t played it once since you joined us in Waterdeep. In my experience, someone who depends on their skills to eat doesn’t give them a chance to get rusty.” He smiled again. “You’ll have to forgive me. There’s not much to do on this stretch of the road but observe each other. I’m called Tam.”

“Brin.” Whatever other attributes Constancia and the rest of their family had tried to impress onto Brin, they had succeeded in making him curious about other people and observant enough of the minor details that hinted at a whole. His eyes dropped to the silver pin on the man’s shoulder-a pair of eyes surrounded by seven stars. The symbol of Selune. Another pin sat below it. But it was pinned from the inside of his cloak. Curious.

Tam followed his gaze. “Suppose the game’s a little duller if I wear my profession on my sleeve, hm?”

“Suppose so,” Brin said. “Do you like being a priest?”

Tam studied Brin for a moment, as if he were trying to divine whether Brin was making conversation or if he was really curious. Brin made himself stay quiet-let him guess.

“It’s a calling,” Tam said finally, “and it suits me. Mostly.”

Which, as far as callings went, sounded like a decent set of cards to be dealt in Brin’s opinion. Maybe the Moonmaiden was a more generous mistress than most.

“What doesn’t suit you?”

Tam leaned forward. “Traveling,” he said in conspiratorial tones.

Brin smiled because he was supposed to-the pin might be the mark of a Selunite, but the spiked chain that looked older than Brin had nothing to do with the Moonmaiden and neither did the canny look in Tam’s eye. At least I’m not the only liar in this wagon, he thought. He wondered if the priest realized his little game of observation went both ways.

“Aren’t you a little young to have fled Neverwinter?” Tam asked.

“Not me,” Brin said. “My parents.” The parents had been part of the story since the beginning-they were his ticket to Neverwinter.

“Ah,” Tam said. “Of course. Where did they head?”

“Darromar,” Brin said, the same city he’d told the wagon driver. Before, it had been Westgate and before that Yhaunn. Later, he thought, he might say Waterdeep-a city big enough that even if he met a Waterdhavian, they wouldn’t bat an eye if they didn’t know the same people or the same areas.

Lying out in the world was easier than lying at home-for one, nobody here assumed Brin was lying when he opened his mouth, and nobody criticized his lies once he told them. The tricky part was keeping his story straight when he had to keep changing things.

“Oh?” Tam said. “I lived in Athkatla for some years.”

Brin nodded, racking his brain. Athkatla … was the capital of Amn-south. Not so far south as Darromar, and while Athkatla was closer-probably-to Darromar than they were now, they were far enough apart that Brin would have no cause to have visited the larger town … except-

“Was the road north always that bad?” he said. “It felt like we’d never make it to Waterdeep.”

Tam shrugged. “It was a long time ago. I left on the road east.”

Brin shrugged and looked back at the road again, a bad feeling creeping through his thoughts. If Tam didn’t mention Athkatla because of the road, then why? Was he just looking for something they had vaguely in common? Or was he trying to catch Brin in a lie? He looked at the odd priest out of the corner of his eye.

He’d felt sure that no one who knew he’d left would be willing to send out hunters or postings. He’d assumed they would just send Constancia and her warrior-priests …

He’s not a bounty hunter, Brin told himself. And if he were, he couldn’t be sure Brin was who he was looking for: There were no portraits to show a hunter, and besides, Brin had stained his blond hair regularly since leaving Cormyr. A hunter would be told he was seventeen, but Brin had been relying on his short height and scrawny build to pass for younger-the wagon master thought he was fourteen, which would have mortified Brin a few months ago but now felt like a special triumph. And the hunter would be looking for someone to answer to another name.

Still Brin was sure of none of these things, and his stomach pulled with the familiar unease that puzzling out someone else’s motives always gave him.

“Where are you coming from?” Brin asked the strange priest.

Tam smiled again, but there was still that look in his eye. As if he knew they were playing a game. As if he could manipulate and maneuver all day long against a little turncoat Cormyrian. As if he knew exactly how Brin’s stomach felt, and how weak that made him.

“Westgate,” he said.

“Did you flee Neverwinter then?”

“No, just lending a hand.” Tam seemed to consider Brin a moment, and he was a little less certain of his assessment-Brin’s mother used to give him a similar look. “Are you sure nothing’s weighing on you?”

“It’s weighing on me that you keep asking that,” Brin said as lightly as he could. “I must look wretched. How soon will we reach Neverwinter, do you think?”

Tam began to answer, but a ululating cry out of the forest startled both of them, and no amount of maneuvering or manipulating would have made any difference then.

“Come on,” Havilar said, stomping her foot. “Hurry up. A good hard sprint and we’ll catch them.”

It was too hot to be sprinting after anyone. Farideh shifted her haversack to her right shoulder. Her scar itched where the strap had rubbed against it for the last few miles. The sweat that trickled over her skin made the itch sting in places.

“Do that,” Mehen said, coming to stand beside her on the crest of the road, “and you’ll spook our bounty.” He raised a spyglass to one eye.

“You don’t even know the bounty’s on the caravan,” Havilar protested. “Because you won’t let us catch up!”

“What do you think is going to happen if we wait?” Farideh asked, joining them. “We’re miles from anywhere.” Ahead on the road, the caravan that had been slipping in and out of sight for the past day was close enough to make out the black dog hanging its head over the edge of the last cart, the bright pink of its tongue.

“This one might … I don’t know … run into the woods and join up with bandits,” Havilar said, “and then what will we do? Hmm? Creep through a bandit fortress for another three bloody tendays?”

Mehen collapsed the spyglass. “Havi, calm down. Let them get ahead. Let them get to the next waystation if they need to. Then at least we’ll have a room and someone we can buy passage to the next Tormish temple from. We’ll catch up. Go practice with your glaive.”

Farideh watched the last wagon hobble over a stone in the roadway. Three tendays had passed since Mehen had taken on the bounty in Proskur, and more and more Farideh suspected they were on the wrong track altogether.

Not that she was an expert; Mehen had done such work in the time between leaving his clan and settling in Arush Vayem, and returned to it quickly enough when they left there. But none of the bounties they’d had in the last six months had been this difficult-

Her scar suddenly flared, hotter than the baked road. She drew a sharp breath and clapped a hand to her shoulder. The pain faded, but Farideh knew it would come again. It came when the cambion was watching her, and it meant he was angry or annoyed or just wanting her attention. It meant he would come. Farideh tensed.

She had no idea why Lorcan was stirred-up-the gods probably didn’t know why he was stirred-up. If he came … Oh Hells, if he came with the caravan so near, they would all be in so much danger. And Mehen would never let her forget it. She rubbed her arm, as if she could rub away the lingering sensation of Lorcan’s pique.

Calm, she told herself. She shut her eyes and tried to breathe more slowly. None of that’s happened.

The burn flared again.

She opened her eyes and cursed. She’d told the cambion-repeatedly-that he couldn’t just appear in front of Mehen and not expect to get them both into trouble. At least Lorcan had stopped appearing as if he were merely coming by to borrow some butter. Now, he needled at her brand until she removed herself from any company. It was only a matter of time before Mehen noticed that, too, not that Lorcan cared.

Bastard, she thought, then wished she hadn’t. She wondered what he wanted.

Farideh looked back at Havilar and at Mehen, who was watching her grimly.

“Fari, come spar with your sister.”

Farideh watched her sister’s fluid sweeps of the wicked-looking blade, her quick jabs with its sharp end.

“Why?”

“Because you need practice,” Mehen said. “And it will help … It will give you something to distract yourself with.”

Farideh pursed her lips, but drew her short sword. She turned the hilt in her hand to get the proper grip, the leather wrappings slick and still uncomfortable in her damp palms. Havilar gave her a skeptical look.

“So are we doing basic passes, then?”

Farideh sighed. “Whatever you’d like.”

“You can’t do what I’d like,” Havilar said. “But it’s not going to help me to go easy on you with Kidney Carver.”

“Kidney Carver?”

“My glaive,” Havilar said. “It needs a name. Every warrior worth talking about has a weapon with a name.”

“Kidney Carver?”

“It’s … carved kidneys,” she said. “Or close enough.”

“Girls,” Mehen warned.

Havilar rolled her eyes. “Come on,” she said to Farideh, “get your guard up. You start defensive.”

Farideh readjusted her grip and brought the sword up in front of her. The glaive swung down in a careful arc, and she caught it on the flat of the blade, shoving it aside. Havi tried again, sweeping the glaive up under Farideh’s sword this time, and Farideh stepped out of its reach, knocking Havilar’s guard open.

Farideh went through the motions like the steps in a dance she only half knew. Parry, dodge, parry, reverse … She counted on the fact that Havilar would go through the passes as rote as possible, if only because she thought Farideh couldn’t handle anything more. It gave Farideh a chance to think about other things-about the bounty, about Mehen’s disappointed expression, about the searing pain that laced her shoulder-so she didn’t bother giving Havilar any other impression.

Farideh’s brand stung so sharply she gasped. At the same moment, Havilar’s glaive came up hard into Farideh’s sword.

Farideh yelped and loosed her grip. The glaive locked under her guard, and sent her sword sailing over Havilar’s head and into the brambles beyond. Mehen heaved a great sigh and covered his face with one hand.

“Gods,” Havilar said. “Did you throw that?”

“You know I didn’t,” Farideh snapped. She wiped the sweat from her hand on her skirt. Her shoulder was on fire. “Go get it, would you?” she begged.

“Hells, no,” Havilar said. “I don’t want to dig through brambles. You lost it. You get it.”

“Fari, go get your damned sword,” Mehen said. “A few brambles won’t hurt you.”

Farideh hesitated. She couldn’t tell Mehen why she didn’t want to go. Better he think she was so fragile as to be afraid of some thorns. Not like Havilar, she thought, as she ducked into a break in the canes where some animal had made a path, and wove her way through the brambles.

The fat smell of blackberries baking in the sun and the buzz of wasps swallowed Farideh. The brambles snagged at her loose robe with every step. When she’d woken that morning to the already-humid air, she’d thought it better than her leather armor. Now, as she untangled thorns from the fabric and waited for Lorcan to appear, she just felt foolish.

She finally stepped free of the thorns and into the open forest. On the other side of the brambles, the hill fell away down through a sparse gathering of pines and spreading maples, their feet carpeted in ferns and overlaid with the remnants of cracked boulders.

And no devils. She waited a moment, but there was nothing. Perhaps he’d had his fun needling her while Mehen grew suspicious.

A little searching found her sword caught on the overhanging canes that had launched themselves over their predecessors in greedy arcs down the hill. She ducked beneath them and wound her hand between the thorns and blackberries, then snaked the sword out, hilt-first, the same way. Through the brambles, she could just hear Havilar and Mehen’s voices, but not what they were saying. She sheathed the sword.

A breeze stirred the air and lifted the sweaty hair off Farideh’s neck.

Out of the breeze, a pair of hands grabbed ahold of her shoulders. Startled, Farideh turned sharply, bringing her elbow around to slam into her attacker’s arm. As she turned, she caught a glimpse of Lorcan’s red skin and his wings. She pulled her arm back against her chest, sending her off balance, and onto one knee.

“Gods,” she hissed. She glared up at him. “Why must you do that?”

“I was starting to worry your arm had been cut off,” Lorcan said, sounding anything but worried. “Or were you just playing hard to get?”

Farideh let him help her to her feet. “You shouldn’t be here.”

“You forced me to,” he said. “You’re going to get hurt if you keep on like this.”

“What? Havi? She gets enthusiastic, but she knows when to pull-”

“Not your sister-although we can discuss what an utter waste of time that was, later. No, I meant the orcs.”

Farideh shook her head. “What orcs?”

He turned her to face north, and left his hands lingering on her shoulders. “Other side of the road, up on the hillside there. There’s an ambush waiting. Maybe a dozen fellows-axes, arrows, at least one shaman. A wonder dear Mehen didn’t spot it.”

“That’s …” She turned out of his hands. “… kind of you, actually. We’ll avoid them.”

“Of course you will.” He smiled and her heart beat to match the throb of her scar. “And even if you didn’t, what are a few orcs? You’d burn them to ashes. I’m not worried about that.”

“What then?”

“Darling,” he said, taking hold of her arm and walking her back toward the part in the brambles, “they don’t want you. They don’t even know you’re here. They’re waiting for that caravan, which is carrying a score of people, including children. Also at least two priests-the kind who won’t be happy to see you. The orcs are out of supplies, they’re lost and they’re hungry-they aren’t looking to leave survivors. Which means you’re going to have to decide.” He ran a finger over her jaw and said, low in her ear, “Do you keep safe and hidden and wait for the people to die, or do you aid the caravan with everything you have?”

A scream split the air, and Lorcan vanished. Farideh stumbled at the sudden lack of him.

A part of her-the part that was still Arush Vayem through and through-insisted she drop to the ground and stay behind the wall of thorns where it was safe. This wasn’t her fight. She couldn’t help. And if she did, the priests would be after her.

She pushed past it and past the brambles. It might be safe this breath. It wouldn’t be safe if the orcs triumphed. And people were going to die.

“Ambush!” she cried, as she broke through to the road. “There’s an ambush! Orcs!”

Mehen and Havilar were already on their feet, watching the caravan downhill. Mehen’s yellow eyes locked on Farideh and he pulled her through the last of the brush.

“A dozen,” she said. “Archers, axemen, a priest or something. There are children in the caravan.”

Mehen spat out a curse and scooped up his pack. “Where did you-”

“Lorcan,” she said, her pulse in her throat. She took up her haversack.

“Bloody, karshoji henish-”

“I know. He was only warning-”

“Later,” Mehen growled. “Come on.” They raced down the hill toward the caravan and the orcs pouring out of the woods. Mehen slid to a stop, taking in the battlefield.

“Farideh, stay here,” Mehen barked.

“I could cast-”

“No,” he shouted, halting long enough to turn and make sure she stopped as well. “Keep out of the way. You stab them if they get too close. Havilar, with me. Don’t get sloppy.”

“Wait!” Farideh called, but they both sprinted into the chaos of the road, and were gone.

A few score feet separated Farideh from the end of the caravan, from the clatter of blades, from the bellows of orcs, the screaming horses, and the singing of arrows through the air. From the heavy thud that carried farther than she’d ever expected as an arrow sank deeply into a man’s chest and toppled him. Mehen was right-she was too nervous for fighting.

She had to do something. She could do something-she thought of the spells Lorcan had given her. She could take out the archers without entering the fray. It was a better solution than Mehen’s, by far. She sheathed her sword.

Spurred by her nerves, the powers that swirled through her spread outward in a cloak of shadowy smoke, a miasma that blurred her and made it harder to spot where she stood. A little protection at least.

She tried to focus, to draw up the powers Lorcan’s pact granted her, but her nerves were jangling. There were too many eyes ready to stare at her.

There are too many eyes, she thought, but they’re too busy to notice you. If you don’t do something they’ll all be dead, and their eyes will be treats for the crows.

She clutched at the stream of magic that ran through her and hurled a rain of fiery bolts toward the forest, far from the crowd, over where the arrows seemed to fall from. She cast another, frustrated-who knew if she were even hitting anything?

Then she saw a boy, about her own age, running toward the thorns that lined the road, chased by orcs. He didn’t see her-she was sure-but she saw the look of fear in his eyes.

The orcs were going to kill him, and he knew it.

No one else was going to save him. She drew hard on the powers of the Hells.

CHAPTER TWO

A chorus of bowstrings sang out and the driver of the wagon behind them screamed, an arrow sunk into his side. Orcs boiled out of the brush, axes clattering on their shields. The little girls in the wagon woke, eyes wide, startling at screams and too shocked to listen to their father’s orders to lie flat in the cart.

All around Brin, people who’d been riding along, quiet as you please, pulled weapons from under provisions and wagon seats and jumped from their carts under a hail of arrows. Tam leaped out of the cart as well and unwound the spiked chain he wore around his narrow waist.

“Shar and hrast.” The priest spat. He shoved a dagger into Brin’s hand. “Under the cart. Stay low and hamstring them as they pass.” His chain lashed out, suddenly alive with holy fire, and caught an orc that sprang onto the road by the throat.

Brin’s ears were buzzing loud enough to drown out the screaming. He looked down at the blade in his hand-rougher than the one in his pack, smaller than the short sword he had in the cart bed. What had the priest said?

What had Constancia said? Loyal Fury, you fight like an actor. You’ll faint the first time someone draws a sword on you, Torm help me-

Brin gripped the blade, despite the fact he did feel light-headed and sick-he knew how to use a bloody dagger!

He looked up in time to duck a notched axe blade. It sliced past his head and slammed into the side of the wagon.

Instinct made him turn the dagger into the orc’s partly bare chest. It sliced through his pectoral and immediately caught on a rib. The orc screamed, a sound more of rage than pain, as he struggled against the stuck axe head.

Brin bolted.

The loose dirt of the forest floor made him slip, and his legs seemed suddenly too long and clumsy, but he ran as fast as he could as the clashing sounds of battle built behind him. There was no room in his head for thoughts of what Constancia would think, what the priest would think, what Torm-the god of duty himself-would think. All Brin knew was that he needed to get as far as possible from the orc with the axe.

Another fearsome roar rattled the air and a creature-half man and half dragon it seemed-barreled up the road. The refugees turned to contend with this new front. But the huge, wicked-looking sword the dragon-man carried avoided the humans and cut into one orc after another. He roared, and the crackle of lightning spread out from his mouth, leaping from orc to orc.

After him, on feet as quick as a deer’s, a devil dressed in well-fitted scale armor used a glaive to stab one orc and then vaulted over his body to kick a second.

Brin’s foot caught a wagon rut as he sprinted past. He sprawled forward, skinning his nose on the ground. He turned over, at the thud of feet. Axe-wielding orcs, three of them now, were chasing him down.

He hadn’t even made it across the road.

The orc in the lead slowed, just enough to pull his axe back over one shoulder.

Torm forgive me, Brin thought. He wished he could apologize to Constancia.

Crack!

With a gust of flames and shadows, something, some creature stood between Brin and the orcs, a horned thing in purple robes with a twitching tail. It raised both hands, gave a soft gasp of effort, and where the robes had fallen down its arms-its human arms-Brin saw veins suffused with black. Horrible clouds of something caustic and dark billowed out toward the orcs. Their screams drowned out the sounds of the fight beyond.

The thing turned on Brin. He glimpsed a face like a girl’s, but with strange eyes and horns. A devil.

“Oh, Loyal Torm,” he managed, before she grabbed him firmly by the arm, and he was yanked … away. The world dropped out from under him, and it felt as if he were being dragged through a bonfire.

He blinked, and suddenly, he was coughing at the sharp taste of brimstone and looking up at the fir tree that had been a solid twenty feet to his right when she’d first grabbed his arm.

The devil wasn’t looking at him. She was watching the orcs. One lay on the ground, half out of the thicket and dead or at least stunned into stillness, but the other two were trying to figure out where the devil and Brin had gone.

She didn’t give them much time to wonder. She tensed again, as something seemed to pulse through her. She spoke a soft word, and a smattering of missiles-a hail of burning sulfur-rained down on the orcs. They howled again, and sprinted toward the devil.

Brin pulled himself up and to his feet. He’d lost the dagger, but … surely there was something he could do to stop her … send her back to-

The devil cast another hail of fire and one of the orcs racing toward them went down. She grabbed Brin by the hand as the orcs reached them, but he twisted, trying to break free. The closest orc’s axe darted out awkwardly, and the flat of it smashed into Brin’s thigh as it swung past.

The devil twisted and punched a fist under the orc’s upraised arm. The orc cried out and dropped the axe. The devil gasped another word in some infernal language.

Again all Brin smelled was brimstone and they were suddenly a few cart-lengths ahead of where they’d been, beyond the fir tree and behind some brush that overhung the side of the road. Brin fell to the ground and cried out with pain. The creature looked down at him, one eye blazing gold, the other silver. “Stay back!”

The second devil was nearly on top of them. She twisted, her glaive catching two orc warriors in the throat in quick succession, the end thrusting back into the first’s belly for good measure, as the first devil caught the same orc with a blaze of flames.

This close he could make out their faces-nearly identical. The same sort of devil. The world was full of monsters.

“What are you doing?” the devil with the glaive shouted.

“Changing the plan!”

“Well hit the damned archers at least!”

The devil who had Brin dragged another rain of sulfur into existence, sending the missiles searing through the forest. Screams followed. She did it again, the blackness suffusing her veins like rot.

He looked up to see the orc who had wounded him running toward them, his features fixed in fury.

“Ye gods!” he cried. He raised his hands, praying furiously-

The orc roared and swung his axe again. The devil-girl holding Brin by the arm didn’t flinch. Her hand came up again, and this time a great gout of flame streaked out of it.

The last of the three orcs toppled over, smoldering slightly and not moving. Another dozen or so lay dead around the caravan, and the remainder were running, crashing through the woods. The scaled man poked at a few orcs’ bodies. The other devil made a few flourishes with her glaive, but the battle had ended. Brin saw the priest drop his chain and rush to the side of a woman whose shirtfront was soaked through with blood. She wasn’t the only casualty. Brin’s hands started to itch.

“Are you all right?” the devil said, bringing him sharply back to the present. Her voice shook and her breath came hard. She reached out to touch his neck where the vein pulsed.

He slapped her hand away and she fell back. He tried to scuttle away, but a sharp pain in his leg reminded him it was injured. The devil leaned down and grabbed his hands again. But instead of teleporting, she hushed him.

“Look,” she said, her voice still light and uneven. “Look, you’re going to hurt yourself. Stop it.” She pulled a vial off her belt and held it out to him. “Here. Here! Drink it.”

He shoved it away. The gods only knew what was in there. She looked around-they were partially hidden behind an overgrown broom shrub. No one would see. No one would stop her …

Gods, gods, she was going to-

“Take the potion,” she said gently. “You’re having a fit of shock.”

“You …” He paused and swallowed. “You can’t trick me like that. Can’t kidnap me.”

She sighed. “If I wanted to kidnap you, don’t you think I would have already done it? You’ve got a wounded leg and you’re panicking.” She gave him a sad look. “I’m trying to help. You’re going to have a hard time walking if you don’t tend it.”

“Where … where are you going to make me walk?” he said, his voice drying up. Her cheeks burned brightly and she looked away.

The second devil-girl strode up and planted her bloodied glaive, tilting it away from her. “Eater of Her Enemies’ Livers,” she interrupted with a wicked glee. “I just thought of it.”

Her twin glared up at her. “Not now.”

“Why?” She seemed to notice Brin. “Oh. Well met. Is he dying?”

“No.”

“Good,” she said. “Then: Eater of Her Enemies’ Livers?”

The first devil sighed. “No. It’s too many words.”

The second girl scowled. “But they’re all the right words.”

“It sounds pretentious.”

“You mean ‘glorious.’ ” The second girl wrinkled her nose and turned to Brin. “What do you think?”

“Ab-about what?” he said. He swallowed. Was this how devils tricked one? Why couldn’t he remember? He could hear the clerics who had given him his lessons droning on about fiendish creatures, see all the lines of their faces, the whiskers of beards and the sleekness of severe coiffures … but the words weren’t coming to him.

Not demons-demons would have ripped him apart and been done. That was something.

“About ‘Eater of Her Enemies’ Livers,’ ” the girl said in an exasperated tone. “Is it pretentious or does it strike fear into the very core of your heart?”

“She’s trying to name her glaive,” the first devil explained. “Like in a story.”

The second one peered at him. “Maybe I shouldn’t ask you. You look a little peaked.”

“Yes,” the first twin said. “So stop waving your glaive in his face, Havilar.”

“Eater of Her Enemies’ Livers,” the second corrected.

The first shrugged. She pulled a rag out of her haversack and handed it to her sister. “I liked ‘Kidney Carver’ better.” She took out a small leather roll and handed it to Brin. “If you want, you can use it.” Brin stared, dumbly. She unrolled it for him. It looked like a healer’s kit.

“Kidney Carver sounds common,” Havilar said. “Like some butcher’s cleaver.”

“Where’s Mehen?” the devil-girl said, still watching him.

“Cleaning up,” Havilar answered. “Why did you run out like that? He’s going to be furious.”

She was quiet for a moment. “Not now, Havi.”

“Yes now, Farideh,” Havilar said. “You ran out like you were going to start cutting all their heads off yourself. You never do that.”

Brin’s pulse was deafening. “To get me,” he said hoarsely. “You came out to … take me from the orcs.”

Farideh’s odd eyes settled back on him, and she nodded hesitantly. “I didn’t mean to scare you. Are you feeling better?”

Havilar bent down and looked at Brin. “You look pale. Are you sure he’s not dying?”

“Ignore her,” Farideh said. “You don’t seem to be bleeding anywhere, so it’s likely a little bit of shock. Which having a blade waved in your face doesn’t help.”

Havilar made a disgruntled little noise and pulled her glaive back. “Worrywart.”

“Show-off,” Farideh muttered.

“I’m the show off? You’re the one slinging magic all around like it was pebbles. What’s that thing? That thing with the fire?”

“A fire bolt.”

“You did a fire bolt on an orc. A wounded orc.” Havilar put a hand on her hip. “That is the very definition of a show-off. Mehen told you to stay back.”

“Says the girl who managed to work a little twirl into every one of her attacks. You know Mehen’s going to tell you off for that.”

“Thrik-ukris!” a man’s voice bellowed, and both girls shut their mouths.

Striding toward them was the enormous scaled man-no, not a man. Brin remembered now: dragonborn.

He had seen dragonborn come to the temple of Torm once, and once before that in the markets of Suzail. They were fierce, disciplined fighters, new to the world of Faerun-new, anyway, since the Blue Fire had remade things a hundred years ago. This far north, they were few and far between indeed.

“What in all the depths and heights of the planes around was that!” The dragonborn man’s features were fearsome even though his movements were sure and calm. Like Havilar he was well fitted in scale armor over his own reddish scales, and along his jaw there were a series of holes, as if once he’d worn rings in that ridge.

He pointed a sharp-taloned finger at the first twin. “We had a plan. You leaped in there throwing fire like a street performer in front of fifty karshoji people, and then very nearly got yourself spitted on a pothac orc’s bastard sword. What in the Hells were you thinking?”

Farideh’s face contorted in anger. “Everyone can stop shouting at me, thanks. I was thinking they were going to kill him. Did you want me just to watch?”

She meant Brin. The orcs had been going to kill … He felt dizzy.

“If I hadn’t done something,” she continued, “then he’d be the one spitted on a sword.”

“Axe,” Havilar said blandly, scrutinizing her glaive. She looked down at him. “You can’t spit things on an axe though. Split. You would have been split on that axe.”

Brin turned and vomited on the ground beside him.

“Yes,” the dragonborn said sarcastically. “I can see you’ve saved quite the precious soul. What would they have done without him?”

“I didn’t get in your way,” Farideh said. “It’s not like they weren’t going to be able to tell what we are anyway. You let Havilar out.”

“Tieflings are one thing but warlo-” He broke off with a hissing sigh. “No,” the man said, “we can have this conversation later. When I lecture your sister for wasting her energy prancing around the battlefield like a godsdamned acrobat!”

“I killed seven of them!” Havilar protested.

“You killed five,” the dragonborn replied. “The two that limped off don’t count. And you could have taken nine.” He looked down at Brin, his eyes as cold and clear as a snake’s, but far more clever. “Are you done heaving all over the ground?”

“Y-yes,” Brin said.

The dragonborn reached beneath his breastplate and pulled out a much-folded, much-handled piece of paper. He smoothed it out and squatted down beside Brin so he could hold it close to his face. It smelled odd and musky, like dragonborn, concentrated. The page was a wanted poster-a picture of a sour-looking woman looked back at Brin. A pointed chin, a pinched nose. Dark, narrow eyes and darker hair with severe bangs. Brin’s heart started racing, and once more, he was afraid he was going to faint.

“You know her?” the dragonborn said. “You see her in that caravan?”

“No,” Brin said. He’d not seen her in the caravan, but he’d seen her nearly every day of his young life.

The woman was Constancia. Utterly, undoubtedly Constancia.

Of course Constancia had come looking for him-it was her head once someone realized he’d fled. Brin had counted on the fact that no one would send out hunters and wanted posters for him-too many had too much at stake for his name to become well-known. But if Constancia had ridden out after him, if she hadn’t gone to her superiors at the temple or their family, then …

The poster spoke volumes: Constancia was apostate for losing Brin.

The dragonborn stood, muttering under his breath in a language that wasn’t Common. “Farideh, Havilar-you two stay here. I’ll sort out things with the caravan master.” He pointed at each of them. “Don’t. Move.”

“Do you think they need help?” Farideh said.

“Don’t you go near them,” the dragonborn said. “You don’t know anything about them and now they know too much about you. Chances are better than good you’ll need your own help when one of them gets skittish and decides to stick you. Stay. Here.”

“They might like us better if we gave them our healing potions,” Havilar said.

“If they’re stupid enough to be traveling this road without their own supplies, then you don’t want them to like you. And they have a priest, so stop making up reasons to go over there.” He stomped off, muttering in the same language as before, toward the caravan and the priest-who had moved on from the bloody woman to a man with a head wound.

I should help, Brin thought, but his mind was racing with concern for his cousin and concern about the devils. What was he going to do?

“Don’t mind Mehen,” Farideh said. “He’s just annoyed we aren’t having better luck up here.”

“We’re bounty hunters,” Havilar chimed in. “Only we have the worst quarry these days. Mehen took her off another bounty hunter who’d given up. Fari’s sure we’ve gotten ahead of her. It’s like hunting a ghost. Except you can lure ghosts.”

“No you can’t,” Farideh said. “Who told you that?”

“Everyone knows that. You use whiskey. In a little plate.”

“That doesn’t even make sense.”

Brin blinked at them, the fog of the fight dissipating and the reality of what he was sitting amidst dawning. “You aren’t devils, are you?”