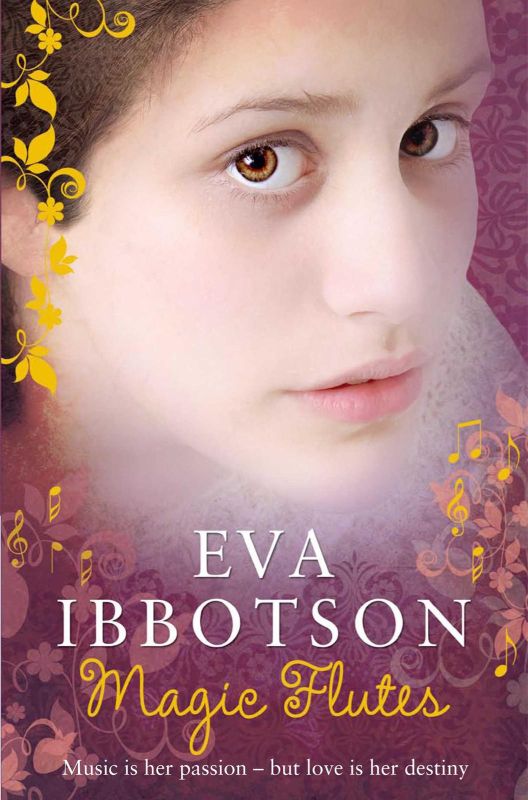

Magic Flutes

by

Eva Ibbotson

To Aaron and Johanna

‘What do they celebrate, the magic flutes of love? Why, tears and laughter’

Prologue

(Birth of a Hero)

They were both born under the sign of Gemini, and for those who believe in the stars as arbiters of fate this must have seemed the link that bound them. She herself was to invoke the heavens when at last they met. ‘Could I be your Star Sister?’ she was to ask him, ‘Could I at least be that?’

Certainly it would seem to need the magic of star lore to link the life of the tiny, dark-eyed Austrian princess — born in a famous castle and burdened, in the presence of the Emperor Franz Joseph, with a dozen sonorous Christian names — with that of the abandoned, grey-blanketed bundle found on the quayside of a grim, industrial English town: a bundle opened to reveal a day-old, naked, furiously screaming baby boy.

Her birth thus was chronicled, documented and celebrated with fanfares (though she should have been a boy). But his…

It was the merest chance that he was found at all, for the bundle was half concealed by sacking and the Tyne docks that mid-morning in 1891 were high-piled with packing cases waiting to be loaded on the boats for Scandinavia, with rusty barrels, coils of rope and coal from the barges. But among the shawled and clogged women on their way to work on the Fish Quay there was one who had sharp ears and detected above the screeching of the gulls another, more frantic and urgent cry.

An hour later, in the Central Police Station in Newcastle upon Tyne, the contents of the bundle had been recorded in the register, found to be the fourteenth foundling abandoned in the city that month and noted to be male.

By the evening, the baby was in the arms of the matron of the Byker orphanage where, duly fed, bathed and clothed in the calico nightdress stitched by the ladies of the Christian Gentlefolk Association, it caused that excellent woman a certain puzzlement.

Bald, shading from puce to apricot and back again under the impact of his rage, the baby, squinting at her with the lascivious eyes of a Tunisian belly dancer, seemed to be made of a different, a denser, substance than any she had known. She was sure she had never seen a baby that sucked at its own wrist with such ferocity or screwed up its legs with such violence, and as she lowered it into the twelfth cot from the left she was already aware that the question she so often asked about abandoned babies, namely ‘Will it survive?’ was inappropriate. If there was a question to be posed about this latest addition to her orphanage, it was rather, would they survive him?

Matron followed her instincts about the occupant of cot number twelve when naming the baby, and rejected the list put out for her guidance by the Board of Governors. The compressed and explosive individual whose irate face appeared so incongruously above the scalloped edges of his nightgown was clearly no Albert or Edward and certainly no Algernon, and ‘Attila the Hun’, though suitable, was unlikely to be acceptable to the gentlemen on whom her livelihood depended. She called the baby ‘Guy’, and for his surname used that of a group of islands off the Northumbrian coast which she had visited as a child with her fisherman father: the Farnes.

A relative lull followed while Guy Farne primed his muscles, coordinated his limbs and secured a few basic necessities in the way of teeth and hair. Then, some three months earlier than expected, he began to crawl and subsequently to walk. Life had now begun in earnest.

Speculation about the ancestry of their babies was something that Matron and her hard-working assistants seldom permitted themselves. Not one of their foundlings had ever been traced or claimed, and in turning them out to be clean, God-fearing and suitable for work as domestic servants or labourers, the staff of the orphanage was doing all it could. With Guy Farne, however, it was different. As he progressed from child-battering to arson, including a little grievous bodily harm and possession of unlawful weapons on the way, there was an attempt to prove that this particular baby could not possibly have been English.

‘Well, he doesn’t look English, does he?’ argued Matron’s assistant. ‘And him being found in the docks like that. I mean, there’s boats from all over come in there.’

‘Aye. He could be anything with those cheekbones and his eyes set like that.’

‘There’s all sorts you find where there are ships,’ agreed cook. ‘Even Lithuanians,’ she added darkly.

A tendency to blame Lithuania increased amongst the staff of the Byker orphanage as Guy Farne reached the age of three, four, five…

‘Though you can’t really say there’s any actual malice in him,’ said Matron, bandaging the leg of a fat girl he had bitten in the calf. ‘I mean, Maisie was bullying little Dora.’

This was true, but the staff found it cold comfort. It was also true that when Billy was carried in with concussion because Guy had knocked him against a brick wall, he had been tying a tin can to the tail of a puppy that belonged to Matron’s sister. And that Guy had stolen a gold watch from a corpulent governor’s back pocket only to present it immediately to the aged boiler-man who had a birthday. True, all true — but when Guy reached his sixth year Matron decided that enough was enough and looked about for a suitable victim.

Her choice fell, as in the manner of fairy stories, on a poor widow named Martha Hodge.

Mrs Hodge had lost her husband when very young in an accident in one of the shipyards; since then she had fostered, very successfully, one little girl with partial hearing for whom she had found a job with a kind lady as a housemaid and another girl who was now working happily in the country. Matron accordingly wrote a letter in her neat copperplate to Mrs Hodge, suggesting that she might like to foster another child and reminding her that the three and six paid weekly by the parish had now risen to a munificent five shillings, enabling those who took up fostering to make a reasonable profit.

Mrs Hodge had not found this to be so, but she nevertheless put on her hat and coat and on arrival at the orphanage told Matron respectfully that she was willing but it had to be a little girl.

‘For without a man to help me, Ma’m, I divn’t think I can deal with a wee lad.’

Matron repressed a sigh and said she saw her point. ‘However, if you’ll just look at the boy now you’re here?’

Guy was led in, glowering, and stood before her. At the time of this encounter he was six and a half years old. Entirely without hope or expectation, he looked at Mrs Hodge. Small for his age, with the extraordinary air of compactness that characterized him, his chin lifted to receive the information that he was not acceptable, he waited. His knees, scrubbed to a godly cleanliness, shone scarred and raw; his naturally springy hair had been slicked down with several applications of vaseline and water and stuck relentlessly to his scalp.

Mrs Hodge looked at him and felt frail and tired and more mortal than usual. Force emanated from this strange-looking boy as visibly as beams from a lighthouse. It was impossible; she would never be able to cope with him.

The boy waited. His eyes, strangely and slantingly set above high cheekbones, were a curious deep green which sent Mrs Hodge in search of images that were beyond her: of malachite, of the opaque and clouded waters of the Nile.

Silence fell. Only the sudden descent of his left sock as the garter snapped revealed the tension that the child was concealing.

It was entirely without volition that the words Mrs Hodge now uttered issued from her mouth.

‘All right,’ she said, ‘I’ll have ’im. I’ll give it a try.’

She had turned to the Matron as she spoke, and it was a few moments before she turned back to look at the boy. When she did so, she had to catch her breath. The child had not moved from where he stood, nor did he smile, yet he was utterly transformed. The mouth, sullen no longer, curved upward; the clenched fists had unfurled, and everything about him, every line of his body, seemed to express joy and a wholly unexpected grace. Most movingly of all, there had appeared in the strange green eyes a glimmer of the purest, the most celestial, blue.

It was then she suspected that she did not stand a chance.

The first month that Guy spent in Martha’s ‘back-to-back’ in the narrow, cobbled road beside the shipyard passed in unnatural quiet. Every child knew that fostering or adoption was on a month’s trial. Memories of cowed and defeated children returning with their bundles to the orphanage had been burned into Guy’s mind when he was scarcely four years old. On the last day of February he packed his belongings, crept downstairs and said, ‘I’m ready.’ It was always thus with him — to anticipate the worst, to be prepared.

‘Ready for what?’

‘To go back,’ said the little boy.

‘Go back?’ said Martha. ‘Whatever for, you daft boy? Don’t you want to stay?’

Guy did want to stay. By the time he had made this clear, his eyes undergoing that characteristic change from green to blue, Martha found herself knocked backwards on to the horsehair sofa, with broom sent flying and hairpins clattering on to the floor.

His violence and aggression now took a different direction. In the orphanage he had fought against the world, now he fought for Martha Hodge. When she explained that kicking, biting and twisting the limbs of children who had fallen foul of her in some way just would not do, he taught himself to box. While applying first aid to the bloodied noses of his victims, Martha wished she had held her tongue. Whether or not Martha, long widowed and still comely, would have wished the fishmonger to kiss her when he came up the cobbled lane with fresh herrings was never put to the test, for no sooner had the tradesman’s arms encircled her waist than Guy shot out from the coal bunker and — forming himself into a human battering ram — sent the unfortunate man sprawling.

School, for which Martha had thirsted like a spent hart for the thicket, provided scant relief, for despite returning with his behind in weals from the cane, Guy still seemed to have enough energy left for hours of mayhem before she got him into bed. Nevertheless, it was from this small, red-brick building between the slaughterhouse and the glue factory that deliverance came. Two years after Guy had come to her, Martha was sent for by the headmaster.

‘He is a devil, Mrs Hodge,’ said Mr Forster. ‘A thoroughgoing, copper-bottomed fiend in hell.’ He embarked upon a recital of the damage that Guy Farne had inflicted in his short time at Titley Street Board School. ‘However…’

Martha, lifting her head at the ‘however’, was then informed that her foster-child had a remarkable capacity for learning: had, in short, more brains than any child that had passed through Mr Forster’s hands in twenty years and could, in his opinion, win a scholarship to grammar school.

She came home, burst into tears and was discovered thus by Guy. Though disappointed that what she wanted of him was something as humdrum as a scholarship, when he was prepared to raise an army or build a fleet, Guy applied himself. Going out with her rolling pin one day to rescue a neighbour’s little boy who was pinned against the sooty brick wall of the shipyard, Martha discovered that the child was warding off not Guy’s threatened blows but his determination to explain the Second Law of Thermodynamics; then she knew that the battle was won.

When he got his scholarship, there was a street party and Guy, now sporting a black blazer with a tower on the pocket, went to the Royal Grammar School. Soon he became, as such children do, bilingual in English and Geordie. His passion was for science, but he had an ear for languages and the kind of maths-and-music brain that gives tensile strength to this type of high intelligence. He still fought at the slightest provocation, but now there were sports to channel his energy and though he was too wary to make friends, friends — cautiously — began to make him.

The scholarship to Cambridge was a surprise to no one except Guy himself. He went to Trinity for natural sciences, and Martha, just as she had braced herself through the years of his childhood for the reappearance of his lost parents, now prepared herself to let him go, without complaint, out of her life.

These preparations were unnecessary. No one was ever to come forward and claim kinship with Guy, nor did Guy himself now show the slightest signs of turning his back on his past. Though he spent the long vacation getting such work as he could to help pay for his clothes and extra expenses, he returned every Christmas and Easter, changing as the train steamed over the Tyne Bridge into his old ways and old dialect as easily as one changes coats. At nineteen, Guy Farne was still on the short side, still trailing his extraordinary strength and compactness as though his muscles were of a different clay. The springy dark hair, the pointed ears which Martha had bandaged to his skull in vain, combined with his high cheekbones to give him that puckish, foreign look that in the orphanage had been laid at the door of the Lithuanians, but his wide mouth and strong chin recalled a simpler, more pastoral heritage. Guy’s eyes, during those years at Cambridge, were seldom without the glint of blue which signalled the well-being of his soul as he came into his own in scholarship, in sport and friendship. Only women he left alone, knowing — as men whose sexual power has never been in doubt do know — how to wait.

He got a First and went to the University of Vienna which, in the year 1911, was unrivalled for its work on the conduction of metallic ions through water. Martha Hodge never knew what happened during that year for which he left bursting with confidence and from which he returned, green-eyed and taciturn, with the information that he was no longer interested in academic life and had thrown up his studies. That he had been deeply hurt was obvious; that it was by a woman she did not find it difficult to guess. Wisely, she held her tongue and received, with her usual quiet attention, the information that nothing mattered except to be extremely rich.

The first million, they say, is the hardest. Guy made his by selling to the house of Rothschild (one of whose youthful members he had known in Vienna) a detailed and audacious scheme for the forward purchase of options on cargo shipping rights. Based on the prediction of a war which, owing to the almost equal balance of power in Europe, would be long, and presented to the amazed old banker in a red student’s exercise book which was to become a family heirloom, it provided at minimum risk — for the down payments to the shipping companies were to be regarded as interest-free and recallable loans — an opportunity to corner the charter market within five years.

Extorting his reward, under the threat of publishing the details of his scheme, Guy left for South America where he spent three months exploring the backward and mineral-rich Minas Cerais. Within a year he had extracted from the Brazilian government an option on the mining rights of the Ouro Preto range, offering in exchange foreign investment and the building of roads and schools for the Indians. It was not the gold and emeralds which were his chief concern, but the cobalt, for he foresaw the western world’s insatiable demand for high-grade steel.

Thus, in those first years, he established a pattern which was to make his success a legend: the use of his scientific training to predict events, the nerve to back his hunches and the direct and practical entrepreneurism of the man on the spot; for he was always to return to the products of the earth’s crust and the adventure of their extraction.

By the time war came, he had a facienda on the Amazon and a diversity of interests from oil to real estate, but he chose to honour his commitment to the Indians and it was 1916 before he returned to England. Resisting the efforts of the War Office to recruit him on the staff, he joined the Northumberland Yeomanry, fighting with a detached ferocity directed not at the enemy but at the blundering fools who had made the war. A year later he was invalided out with a shattered leg and a Distinguished Service Order and set about forming his own investment company. By now he had a retinue, an international reputation and offices in a dozen capitals, but Martha Hodge — as he returned at intervals to install into the house she resolutely refused to leave, first running water, then electricity, then a bathroom — continued to be troubled by the colour of his eyes.

Then, in the spring of 1922, he returned to Vienna.

1

Guy returned to the capital of a dismembered empire: a city impoverished by defeat, in the grip of inflation but still beautiful. The theatres were open, the concert halls were packed. The Viennese still danced, still sang. Sometimes, as the new republic struggled with the shortages and disruptions left by the war, they even ate.

Guy took a suite at Sachers, saw that his stenographer and chauffeur were suitably housed nearby and allowed himself a week of the swashbuckling entrepreneurism that was his hallmark, wresting the copper concessions in the Eisen Gebirge from an Armenian syndicate after a spectacular battle, and gleefully beating a South African tycoon to the lignite deposits near Graz. After which, considerably refreshed, he presented himself at the Treasury and plunged into the work which had brought him to Vienna.

It was work shrouded in secrecy, as vital and exacting as it was outwardly unspectacular. For Austria was seeking a huge loan from the League of Nations, seeing in this her only chance to stabilize her currency and set off along the road to recovery. It was to assist the new republic in presenting her case to the League that Guy had been sent out by the British government, who feared that a permanently weakened Austria would seek union with Germany. No one seeing him, day after day, courteous and patient, would have imagined how irksome he found the ponderous bureaucracy and time-wasting social functions in the stuffy, grandiose rooms of the Hofburg.

Then, on a fine Saturday at the end of March, Guy, obeying a summons from his young secretary David Tremayne, left the city, dismissed his chauffeur and turned his car southward towards the fortress known as Pfaffenstein. This is the most famous castle in Burgenland, an emblem for the whole of Austria — the embodiment for close on a thousand years of defensive power, aggression, grandeur and pride.

The position alone is breathtaking. At the head of a dark green lake whose glacial waters chill the blood even in midsummer, is a great pinnacle of rock rising skyward from the pines which cling to its base. To the east the crag, split from top to bottom by a fault in the rock, drops sheer to the Hungarian plain. To the north are the wooded slopes and jagged peaks of the Pfaffenstein mountains whose passes it dominates; to the west, sloping more gently, are the vineyards and orchards which merge in the far distance with the snow crown of the Alps.

On the summit of this gigantic eyrie, the last outcrop of the Pfaffenburg spur, the Franks built a fort at the time of Charlemagne, but even they were not the first. Two hundred years later, the Crusaders added a square of turreted towers, threw a drawbridge over the dizzying ravine to the east of the castle and rode out full panoplied against the infidel, bearing aloft the banner of the Pfaffensteins with its impaled griffin and crimson glove.

By the time Richard Coeur de Lion was brought there, pending his imprisonment at Durenstein, Burg Pfaffenstein was a thriving Romanesque citadel with a council chamber, a chapel and a village clinging humbly to the base of its crag. In subsequent centuries, as the Tartars invaded Hungary, the Hungarians invaded Austria and the Turks invaded both, its fame and importance increased as steadily as the power of its owners who became, by conquest and marriage, first counts, then margravines, then princes.

The rout of Sultan Mahomet’s troops after the second siege of Vienna, which banished the Turks for ever from Christendom, set in train a riot of new building as cannon bastions and barrier walls were blown up and the years of imperial splendour under the ever mightier Habsburgs were reflected in Pfaffenstein’s steadily increasing grandeur, opulence and pomp. Ignoring, but never quite managing to erase, the dungeons built deep into the rock, the torture chambers and oubliettes of the earlier fortress, the princes of Pfaffenstein built a palace along the southern front, the windows of its great state rooms sheer with the crag as it rose above the lake; blasted terraces out of the rock and threw pepper-pot turrets on to the flanking towers. A musical Pfaffenstein built a theatre, an Italianate one arcaded the courtyards, a prince of the Church enlarged the Romanesque chapel to form a soaring, gilded paean to the glory of God.

Larger than Hochosterwitz, more heavily fortified than the Esterhazy palace at Eisenstadt and far, far older than the castles that the poor mad Swan King Ludwig had built to the north in Bavaria, Burg Pfaffenstein, by the end of the nineteenth century, had become the subject of innumerable paintings and the inspiration of countless minor poets. The redoubtable Baedecker, when he arrived, gave it three stars.

To this castle, driving himself in his custom-built, tulip-wood Hispano-Suiza, came Guy Farne on a spring afternoon in 1922, with a view to purchase.

He came, as all who come from Vienna must, by the road which skirted the western side of the lake and as the fantastic, towering pile reared up before him, his wide mouth curved into an appreciative smile.

‘Yes,’ he said to the young man sitting beside him, ‘it will do. Definitely, it will do. You’ve done well, David.’

His secretary, David Tremayne, whose fair good looks and puppyish desire to please concealed a tireless efficiency, turned a relieved face to his employer. ‘I thought you’d like it, sir. I saw a few others but I don’t know… This one put them all in the shade.’

‘It certainly makes its own quiet statement,’ said Guy sardonically.

But as he switched off the engine and got out of the car, he momentarily caught his breath. Burg Pfaffenstein’s role as fortress, as refuge and as palace was evident in every stone. Now, in the still, green lake which mirrored with exquisite accuracy each tower and pinnacle and glistening spire, Guy saw it in another guise: as Valhalla or Venusberg — the castle as dream.

‘You’re certain the owners want to sell?’

‘Absolutely, sir. There are only the two old ladies left now and a great-niece in Vienna.’ And David fell silent, thinking with compassion of the proud, impoverished families he had visited in his search, all desperate to offer him their ducal Schloss or moated Wasserburg or hunting lodge.

Guy nodded, measuring the road which passed under the crag at the head of the lake and then vanished into the ravine.

‘Let’s see if we can make it without oxygen, then,’ he said and climbed back into the car.

But as Guy drove skilfully round the hair-raising bends that led up to the Burg, David was frowning. His instructions had been simple: to find an impressive and imposing castle (‘toffee-nosed’ was the word his employer had used, reverting to his origins) which the owners were willing to rent or preferably to sell.

Only why? This was something Guy Farne had not chosen to reveal to his otherwise trusted secretary, and the whole enterprise seemed totally out of keeping with what David knew of his employer’s tastes and inclinations. A millionaire he might be, and several times over, but his personal habits were spartan to a degree which caused deep pain to Morgan his chauffeur, to Miss Thisbe Purse, his stenographer, and at times to David himself. Farne’s indifference to comfort, his ability to go without food or sleep, his detestation of pomp were a byword, nor had he troubled to conceal his contempt for those post-war profiteers who conned the newly-poor out of their houses and possessions. True, his sojourn in Austria was likely to be of some duration and he needed a base — but why this gigantic castle? In Brazil, where other men of his wealth had bought palaces, he had lived in a simple if lovely facienda by the river, his only extravagance a steam yacht with which he explored the mazed waterways of the Amazon. In London he lived in an apartment in the Albany, in Paris in a roof-top flat in the Ile St Louis which but for the glory of its plumbing might have belonged to any Left Bank painter or poet. Only on movement — elegant boats, fleet cars and (his latest acquisition) a small bi-plane — did Farne habitually spend the awe-inspiring sums which betrayed his stupendous wealth.

They had negotiated that last hairpin bend, crossed the drawbridge, been sneered at by the griffins on the gatehouse arch and now drew up in a vast and silent courtyard.

Ten minutes later, having followed an ancient retainer in the Pfaffenstein livery of crimson and bottle-green along an immense groin-vaulted corridor and through a series of shrouded and magnificent rooms, they found themselves in the presence of the two old ladies who were now the castle’s sole occupants.

Augustine-Maria, Duchess of Breganzer, was in her eighties, her eagle’s beak of a nose and fierce grey eyes dominating the wrinkled, parchment face. The Duchess wore a black lace dress to the hem of which there adhered a number of cobwebs and what appeared to be a piece of cheese. A cap of priceless and yellowing lace was set on her sparse hair and her rather dirty, arthritic hands rested on a magnificent ivory cane which had belonged to Marie Antoinette.

Her sister-in-law Mathilde, Margravine of Attendorf and Untersweg, was a little younger and in spite of recent shortages, resolutely round-faced and plump. Unlike the Duchess who had received them standing, the Margravine remained seated in order to embrace more efficiently the quivering, shivering form of a goggle-eyed and slightly malodorous pug whose lower extremities were wrapped in a gold-embroidered Medici cope.

Driven back room by room by their poverty, the demands of the war (which had turned Pfaffenstein into a military hospital) and their own increasing age and infirmity, the ladies had taken refuge in the West Tower, in what had been an ante-room connecting the great enfilade of state rooms on the southern facade with the kitchens.

Its round walls were hung with tapestries which Guy suspected had been chosen more for their capacity to exclude draughts than for their artistic content, for they mainly depicted people holding heads: Judith that of Holofernes, Salome of John the Baptist and St Jerome of a dismembered stag. The Meissen-tiled stove was unlit; dust lay on the carved arms of the vast chairs fashioned, it seemed, for the behinds of mountain ogres — but the condescension and graciousness of the ladies was absolute.

‘Welcome to Pfaffenstein, Herr Farne. We trust you found your journey enjoyable.’

Guy, kissing the extended hand and replying suitably, noticed with pleasure that the Duchess spoke what was called ‘Schönbrunner Deutsch’, a dialect which the high nobility shared with the cab drivers of Vienna. And indeed both ladies had been attendant on the Emperor Franz Joseph’s family in the palace of Schönbrunn outside Vienna where the gruelling Spanish ceremonial, the staggering absence of lavatories and the indifferent food had proved an excellent preparation for their present way of life.

Refreshment was offered and refused, the necessary courtesies were exchanged. Then Guy, whose German was fast and fluent, came to the point.

‘You will know already that I would like to buy Burg Pfaffenstein. My solicitors have mentioned the terms?’

The Duchess inclined her head. ‘They are fair,’ she conceded, ‘and we are willing. But as I have already informed your secretary, for a final decision we are awaiting a reply from Putzerl.’

Hearing the name, the pug shot like a squeezed pip from his golden cope and began to run round the room yapping excitedly, causing Guy to exchange an apprehensive glance with his secretary. If Putzerl was the name of the little dog they were in trouble.

The danger passed. For Putzerl, as the ladies now explained, was the great-niece in Vienna, more precisely the Princess of Pfaffenstein and (her mother having been an archduchess) of quite a few other places, and now the sole and legal owner of the castle with its dairies, sawmills, brewery, villages, salt-mine (now defunct) and 56,627 hectares of land.

‘Because, you see, when her father went off to fight he managed to break the entail on the male heir and a great fuss it was. He had to go and see poor cousin Pippi in the end,’ said the Margravine.

‘But we’re certain she’ll agree. She’s been urging us to sell. Putzerl is extremely modern,’ said the Duchess. ‘And of course the money will be invaluable for her dowry because poor Maxi really doesn’t have a kreutzer to bless himself with.’

The dizzying capacity of the Austrians to refer to absolutely everybody by some appalling diminutive or nickname, which Guy had forgotten, now returned to his mind. Having gathered that cousin Pippi was Pope Pius XV, he was now informed, though he had been careful not to ask, that Maxi (alias Maximilian Ferdinand, Prince of Spittau and Neusiedel) was the young man they had picked for Putzerl to marry, there being — owing to the cruel war and the sordid revolutions in various places which had followed it — quite simply no one else.

‘The Gastini-Bernardi boy would have done quite well, actually,’ said the Duchess, on whom the thought of Maxi seemed to be working adversely. ‘But he’s dead. And I must say there always seems to be cholera in Trieste.’

‘Or Schweini,’ said the Margravine, her voice soft. ‘Such a sweet-looking boy.’

‘Don’t be silly, Tilda. The Trautenstaufers only have twelve quarterings.’

‘Still, they’re in the Almanach…’

The argument that followed seemed a little pointless since Schweini, though destined for the Uhlans, had apparently been speared to death by one of his own boars before he could cover himself with glory. Guy, while not wishing to appear indifferent to Putzerl’s matrimonial prospects, now felt free to indicate that he would like to look round the castle.

If he had hoped that he and David would be allowed to roam at will, his hopes were dashed. The retainer was rung for, the pug lowered on to the ground again; shawls, walking sticks and bunches of keys were fetched and the expedition set off.

Within ten minutes Guy realized that Pffaffenstein, inside and out, was exactly what he had been looking for. Its neglect, though spectacular, was recent. In the three months he had set aside for the task he could easily restore it to its former splendour. The huge, baroque state rooms with their breathtaking views over the lake were ideal for his purpose; the guest rooms in the loggia were sound and the outer courtyards with their stables, coachhouses and servants’ quarters would house his workmen without inconveniencing the villagers. Above all, the private theatre with its aquamarine curtains, gilded boxes and ceiling frescoes by Tiepolo was a jewel which would be the perfect setting for the entertainment that was to set the seal on his plans.

But if he had seen enough to satisfy himself almost at once, there was no way of hurrying the ladies.

‘This,’ announced the Duchess unnecessarily as they entered a low building piled from floor to ceiling with skulls, ‘is the charnel house.’

‘Those skulls on the right are from the Black Death,’ said the Margravine helpfully.

‘And the ones on the left are Protestants,’ said the Duchess, murmuring, as she recalled the probable Anglicanism of Guy and his secretary, that there had been a ‘little bit of trouble’ during the Thirty Years War.

But it was before a lone skull displayed on a plinth in a kind of bird-cage and still boasting fragments of a mummified ear, that both ladies stopped with an especial pride.

‘Putzerl found this one when she climbed out through the dungeons on to the south face, the naughty girl.’

‘She believes it’s a Turk and we never had the heart to contradict her, though it is most unlikely. The Turks were all impaled on the eastern wall.’

‘We think it was probably a commercial traveller who came to see her great-grandfather.’

‘About saddle soap,’ put in the Margravine.

‘He came by the front entrance, you see. And poor Rudi was always so impulsive.’

They inspected the chapel with its Eichendorfer altar piece, climbed up yet another massive flight of stairs to the weapons room bristling with flintlock pistols and percussion guns; the museum packed with the heads of wolves, boars and the last auroch in the Forest of Pfaffenstein which Kaiser Wilhelm II had shot, only to be bitten in the leg by the three-year-old Putzerl for his pains… And down again, passing the well into which a seventeenth-century princess of Pfaffenstein, who had not cared for the matrimonial arrangements made on her behalf, had thrown herself on her wedding day.

‘Which was extremely silly of her,’ added the Duchess, ‘because he would have had Modena and Parma had he lived.’

‘Oh, Augustina, but he had no nose,’ expostulated the gentler Margravine. ‘It was all eaten away, you know,’ she explained to Guy, blushing, ‘by a… certain disease.’

‘Putzerl used to sit here on the rim of the well for hours when she was little,’ said the Duchess, ‘waiting for a frog to come.’

‘She wanted to throw it against the wall, like in the fairy tale, and turn it into a prince.’

‘And then one day a frog really did come and she cried and cried and cried.’

‘The frog was so much prettier than a prince, you see — even than Schweini, and he had the most lovely curls!’

‘So she kept it in the oubliette as a pet. Now here,’ continued the Duchess, opening a studded door from which a flight of slime-green steps led down into the darkness, ‘we must be a little careful. But you’ll be interested in the third Count’s collection of torture instruments. It is arranged exactly as the Inquisition left it!’

But at last they were back in the tower room, solicitors’ names exchanged, contracts mentioned and a bottle of Margaux ’83 brought up from the cellar.

‘And how soon would you wish us to leave?’ asked the Duchess, her voice carefully expressionless.

Guy leaned back in his carved chair and, the ladies having given him permission to smoke, selected a Monte Cristo, rolled it between his long fingers and began the careful husbandry that precedes the lighting of a great cigar.

‘There is no need for you to leave at present unless you wish to,’ he said. ‘On the contrary. In fact, you could say that in proposing to purchase Pfaffenstein I am endeavouring to secure your services.’

The ladies, whose small breath of relief had not escaped him, looked at him in puzzlement. ‘What had you in mind, Herr Farne? Not tourists? Because I’m afraid we couldn’t countenance that.’

No, no,’ said Guy soothingly. ‘Nothing like that. I propose to give a house party here at Pfaffenstein. It will last for a week and include a ball, a banquet, possibly a regatta on the lake — and finish with an entertainment here in the theatre. And I want you to select the guests.’

‘Us?’ faltered the Duchess.

Guy inclined his head. ‘I only ask that they should belong to your social circle.’

‘You wish to entertain our friends to a banquet and a ball?’ said the stunned Margravine.

‘And a house party to follow,’ repeated Guy. ‘I myself shall bring only one guest: a lady.’

Guy’s voice had been carefully expressionless but David leaned forward, aware that he had touched the heart of the mystery. At the same time he felt an inexplicable sense of unease.

‘A lady to whom I hope to be married,’ Guy continued. And answering David’s look of bewilderment, the slight hurt in the boy’s face, he added, ‘She is the widow of an officer wounded in the war and her period of mourning will only end in June, so no formal engagement exists as yet.’ He paused, and David saw the extraordinary change in the colour of his eyes as he remembered happiness. ‘I knew her years ago in Vienna.’

‘She is Austrian?’ enquired the Duchess.

‘No, English, but she loves your country. I should add perhaps that I am myself a foundling and was discovered in circumstances so disreputable that they must entirely preclude my seeking an entrée into the nobility. Indeed, my ambitions in that direction are non-existent. It is otherwise, however, with Mrs Hurlingham. Her aunt,’ said Guy, who had been made well aware of the fact, ‘was an Honourable.’

The ladies exchanged glances. ‘That is not a very high rank, Herr Farne,’ said the Duchess reprovingly.

‘Nevertheless she wishes, most understandably, to take her place in society. And I,’ he went on, his voice suddenly harsh, ‘do not wish her to suffer from being married to a man who is not even low-born but not “born” at all.’

‘It will be difficult,’ stated the Duchess.

‘She is not perhaps a Howard? Or a Percy — the aunt?’ enquired the Margravine hopefully.

‘I don’t think so.’

‘Oh, dear.’ The Duchess was perplexed. Well versed in the ways of the world, she was aware that the attractive Herr Farne with his wealth and obvious indifference to what anybody thought of him would be accepted far more easily than a fiancée with aspirations. ‘You see, our friends are rather particular. Prince Monteforelli, for example…’

Though highly entertained by the deep and ingrained snobbery of these old women, whose country on the map now looked like a severed and diminutive pancreas, whose court and emperor were totally defunct, Guy felt it was time he made his position clear. So leaning back, gently lowering a wedge of fragrant ash into the Louis Quatorze spittoon with which he had been provided, he said placidly that if they felt unable to introduce Mrs Hurlingham to European high society he regretted that the sale would be cancelled.

The ladies now retired behind a screen to confer. Though they spoke in whispers, they were sufficiently deaf for their deliberations to be perfectly clear to Guy, who gathered that their desire not to deprive Putzerl of her dowry, along with the lure of the word ‘banquet’ was fast overcoming their reluctance to offend their friends by introducing them to a lady whose aunt, though an Honourable, was unrelated to the great ducal families of Britain.

‘Very well, Herr Farne,’ said the Duchess with a sigh. ‘We will present your friend.’

‘Good,’ said Guy. ‘You should hear from my lawyers in a few days, by which time I trust your great-niece will have been in touch, and then I will send in the workmen. Mr Tremayne here,’ he continued, grinning at David, ‘will see to everything. There is one other condition. I want complete secrecy. My name is not to appear in the transaction; the deeds will be made out in the name of one of my companies. I would prefer that even the local people do not know that I am the new owner until everything is completed. I suggest June the eighteenth for the reception and the opening ball?’

‘Very well, Herr Farne.’

‘Oh, and I want to hire an opera company. Is there one that you can recommend?’

Even the ladies of Burg Pfaffenstein were impressed by the high-handedness of this.

‘The International Opera Company in the Klostern Theatre is said to be very good. Putzerl often speaks of it.’

‘And she’s extremely musical. In fact she’s studying music’

Guy thanked them, removed a spider which had fallen into his wineglass and took his leave.

It was not until they were halfway back to Vienna, eating supper in the candle-lit dining room of the White Horse Inn, that Guy, crumbling a roll in his long fingers, chose to give his secretary some kind of explanation.

‘You’ve been very patient, David. You must think I’ve gone quite mad. All that for a woman… Only, you see, she’s had a rotten life — forced into an unhappy marriage, then watching the poor devil take four years to die.’ He was silent for a moment, his eyes on the candle flame, the customary mocking look momentarily absent from his face. He looked years younger and to David, who worshipped him, suddenly and frighteningly vulnerable.

‘I want her to have everything she wanted at seventeen, however absurd,’ he went on. ‘Everything. She doesn’t even realize I’m rich — we only met a fortnight before I came away and I didn’t tell her. When I knew her before, I was twenty years old and penniless. I want her to come upon Pfaffenstein lit up for a ball and peopled with princes. I want her to walk into a fairy tale — and know that all of it is hers.’

‘She must be very beautiful,’ said David quietly.

‘The most beautiful woman I’ve ever seen. She’s lovely now but at seventeen — oh, God!’

And for the first time in his life, Guy began to speak of his love for the girl who had been Nerine Croft.

2

Whether it was the sheer beauty of the city, then at the height of its imperial splendour: a city from whose every window came music, a lazily grey and gold-domed city framed in the cherished hills and vineyards of the Wienerwald… whether it was Vienna itself or the cosmopolitan society Guy experienced there, or the fizz of new thought as Schönberg revolutionized music, Klimt’s golden, exotic ladies scandalized the world of art and Sigmund Freud produced the outrageous theories which were to change men’s views of themselves for ever… or whether it was simply that he was young and at the height of his powers, Guy now paused in the conquest of knowledge, the world, himself — and began simply to enjoy life.

What happened next was of course inevitable, but to Guy it was the miracle that a first love, truly and violently experienced, is to every man who is worthy of the name.

Vienna, in those halcyon years, was not only a gay and fashionable capital but also the centre of a thriving international industry: Europe’s most popular marriage mart. To the finishing schools of Vienna came the daughters of American millionaires, British industrialists and the French nouveau riche, nominally to learn German, study music and appreciate art — actually to take the preliminary steps which would secure, in due course, a husband both nobly born and rich.

Housed generally in some magnificent Schloss whose owners had fallen on hard times, protected by high walls and splendid iron gates, these girls, who often could scarcely add two numbers together, nevertheless understood precisely the subtle arithmetic by which a German ritter with land might equal a Hungarian count without… how a French vicomte with a pedigree could nevertheless be set aside for an Italian marchese with factories discreetly out of sight somewhere which made him a millionaire. As for a prince, he needed nothing else. To be addressed as ‘princess’ these girls, well-trained by their mothers, would have embraced a man of fifty with dentures and the pox.

Meanwhile, enchantingly dressed in their muslins, frantically chaperoned by hatchet-faced and underpaid ‘companions’, the girls trooped through museums, attended concerts and military manoeuvres and took excursions into the surrounding countryside.

This beguiling, hot-house world was one to which normally Guy would never have had access. But coming into the university lobby in his first month in Vienna, he found a pale, frightened, long-haired young man pinned to the wall by two cropped louts from the Jew-baiting Burschenschaft who were questioning him about his ancestry.

Guy had been leading a life of exceptional docility but a look of pleasure now spread over his face. Taking one of the louts by the shoulder, he said he would be obliged if they would leave his friend alone.

The lout, swinging round to meet a pair of malachite eyes, asked what business it was of his? Guy, mustering his German, said that bullying did not amuse him, adding that if there was no objection to duelling with someone who had been found under a piece of sacking on the Fish Quay in Newcastle upon Tyne and was most unlikely to have been born in wedlock, then he would be delighted to meet him. Otherwise, if he did not go away, Guy would pulverize him into insensibility and knock his idiotic duelling scar into his earhole. The second lout, coming to trip him up, found himself rolling down the steps towards the Ringstrasse.

Nonplussed, the louts departed. The victim, who in spite of his tragic and semitic appearance was the scion of a noble Hungarian house, now became Guy’s devoted slave and invited him to his family’s box at the Opera. In the neighbouring box, displayed like the choicest flowers from Olympus for the gaze of the populace, was a group of girls from Frau von Edelnau’s Academy. Pretty girls, striking girls — and one, in the seat nearest to Guy, who possessed that unique quality: an unequivocal and breathtaking beauty.

The English are a plain race but just occasionally, borrowing usually from some Celtic ancestor, they achieve a breathtaking perfection. Nerine Croft’s dusky, abundant ringlets were tied high with a golden thong to dance on her bare shoulders: the forget-me-nots embroidered on her white muslin dress mirrored the heavenly blue of her wide-set eyes and her small nose, as though to ward off the accusation of a cold perfection, was slightly, tantalizingly retroussée.

If it hadn’t been The Magic Flute… if she had not, as the curtain rose, given the smallest of anticipatory sighs… if she had not, at the end of Pamino’s miraculous aria of exalted love, turned in the soft dusk of the lôge and smiled at him.

But it was Mozart’s masterpiece, and she did so turn. The parents of Guy’s friend were acquainted with Frau Edelnau, and in the interval he was introduced. Nerine, delighted to find that he was English, said, yes, the singing had been wonderful and, yes, he could procure for her an ice.

So it began. It was spring: violets in the Prater; Strauss in the Stadtpark; the café tables with their bright, checked cloths spilling out on to the pavements once again. Bells rang in this enchanted city, the Kaiser drove out in a carriage with golden wheels… It was Frau Edelnau’s policy to invite suitably vetted young men to private dances and outings with her girls. To this select band of officers and students Guy, who at twenty was a strangely compelling creature with his wolf’s eyes and air of compressed energy, was now admitted. And Nerine, trained almost from birth to beguile and flirt and please, was enchanting to her young compatriot whose physical courage and intellectual brilliance were becoming something of a legend in the University.

And so, in a city which God might have designed for the purpose, Guy experienced the miracle, the transforming alchemy of total love. Every plumed spray of lilac in the Volksgarten, every caryatid supporting Vienna’s innumerable pillars, every street-seller with her brazier of chestnuts seemed to him limned in light. He wrote songs to Nerine and sent them floating as paper boats down the River Wien; he kept vigil outside her window at night. Friends clustered round him like puppies, bemused by his happiness. He discovered the Secessionists, climbed the dizzying verdigris dome of the University, and hardly ever went to bed. That spring and summer of his twenty-first year, Guy was invincible.

Later, he was to ask himself how much Nerine had been affected. She was always enchanting, looking up at him with those artless, deep-blue eyes, and he was accepted by the other girls as ‘hers’. But Frau von Edelnau and her minions had brought chaperonage to a fine art. Guy was allowed to waltz with her at private dances but never more than twice, to walk beside her carriage in the Prater, to procure lemonade at the manoeuvres and military parades so beloved of the Viennese, but it was impossible to be with her alone.

Until the picnic in the Vienna Woods…

The word ‘picnic’, which to the British suggests a casual and relaxed approach to eating, suggested to Frau Edelnau something quite different. Rugs and hampers of food were piled into carriages; the ropy arms of the chaperones emerged from hastily donned dirndls, and the expedition set off for the ruined monastery on the Kahlenberg now suitably provided with wooden tables, carefully sited vantage points and hygienic toilets.

They arrived… picnicked… the chaperones dozed, overcome by salami and pumpernickl. The girls picked cornflowers and marguerites to twine into their hair.

‘There can’t be anything better than this,’ said a freckle-faced, sunny American girl, looking at the tapestry of the green and gold-domed city below them.

‘Yes, there can,’ said Nerine.

‘What, then?’

‘Oh, being rich… having marvellous clothes… Dancing the night through with princes at a glittering ball. Living in a castle.’

Guy, as always, was beside her.

‘I’ll buy you a castle,’ he said.

Nerine turned and stared at him, caught not by the words but by the tone in which they were spoken. It was almost as though this impecunious boy really had the power to grant wishes. She became dreamy, pensive… Guy had found a glade of wild orchids in which there danced a myriad golden butterflies. Now he offered to show it to the girls and a party set off. The others fell behind and in a sudden shaft of sunlight Nerine, dazzled, stumbled on a root.

Guy caught her and quite beside himself by now, kissed her with all the passion of his nature.

And Nerine kissed him back.

To Guy, adrift in a foreign city, reared by Martha Hodge, that kiss meant one thing and one thing only. When Nerine returned to England, he followed her and in a daze of happiness, presented himself at the Crofts’ ornate and over-furnished villa in Twickenham to ask for her hand.

It is hard to see why they were not kind. So simple, surely, to have spoken of her youth, his need to complete his studies, their conviction that at seventeen their daughter could hardly know her own mind. Instead, the Crofts exhibited a cruelty and arrogance that he had not known existed.

‘Insolent puppy!’ snorted the empurpled Mr Croft, just returned from his city bank. ‘How dare you! I ought to have you horse-whipped.’

‘No birth, no family and no prospects,’ sneered Nerine’s brother, a pallid young man of Guy’s own age. ‘I must say you’ve got a nerve!’

‘And penniless!’ roared Mr Croft, to whom poverty was the ultimate crime.

‘Are you aware that Nerine’s aunt is an Honourable?’ enquired Mrs Croft, a small, tight-lipped woman with calculating eyes.

Unable to lift a finger against the relatives of his beloved, Guy stood stock-still in the centre of the drawing-room with its draped piano legs and overstuffed cushions. But the footman, coming forward in response to Mr Croft’s instructions to ‘Throw him out, James’, found himself reeling against the wall, nursing his arm.

Nerine was not present at the interview. His subsequent letters were returned.

That had been ten years ago. To say that the wound had never healed might seem absurd. If Guy was deflected, now, from the path of scholarship and determined to become rich enough to be revenged on the Crofts of this world, it was a decision he never regretted. Three years later he was in the Amazon, entertaining a string of lovely women on his yacht, and in the years that followed he had innumerable affairs. But he never again fell in love — and he never forgot.

Then, just two weeks before he left for Vienna, he had come out of the new, seven-storey office block in the Strand which housed his Associated Investment Company when he heard a soft voice say, ‘Guy!’ — and there she was.

Nerine was in half-mourning, her raven hair piled high under a plumed velvet hat. She had filled out, there were now a few lines round her lovely eyes, but Guy, as he gazed at her, was gazing at his youth.

She was pleased to see him, pleased and surprised, she made that clear, having no idea what had become of him. Her own story was sad: marriage to the son of a baronet who should have inherited a title and a comfortable life as a landowner — and had instead died by slow degrees of a wound received in Flanders.

‘So I’m back home,’ said Nerine, lifting a face full of courage and resignation to his. ‘And you, Guy? How are you?’

‘I’m just off to Vienna, as a matter of fact,’ said Guy, when he could trust his voice again.

‘Ah, Vienna! I was so happy there! Do you remember…?’ Guy remembered.

Nerine’s father was dead. Her brother had speculated unwisely. In the villa at Twickenham, Guy, though he kept his wealth a secret, was now a welcome guest. When he left for Austria, it was with Nerine’s promise to join him, with her brother, as soon as she was out of mourning. Though nothing could be settled until then, he had returned to Vienna as a man who, against all expectations, was to achieve his heart’s desire.

3

Though she was both emancipated and in a hurry, Tessa began the day by brushing, with three hundred regular strokes, her almost knee-length, toffee-coloured hair. Her country upbringing had been strict and even though her glorious new life in Vienna was now devoted to the service of art in general and opera in particular, she found it hard to break the habits of her childhood. Moreover, it was true that lacking the height, the Rubenesque and potentially heaving bosom and the Roman nose she so desperately craved, she could find a certain consolation in the rich, fawn tresses which she could most comfortably have sat on had her employer, Jacob Witzler, ever given her the time.

Whether Tessa would have appeared on the payroll of the International Opera Company as under wardrobe mistress, assistant lighting engineer, deputy wigmaker, A.S.M., prompter or errand girl, remained a theoretical question since she did not, in fact, get any pay. That it was an inestimable privilege to be allowed to work in the opera house and learn her craft, Tessa, her auburn eyes burning with artistic fervour, had assured Herr Witzler — a view which he entirely shared and had in fact suggested to her in the first place. And though she did not actually have any money to speak of, it had all worked out marvellously because Frau Witzler, a former Rhinemaiden and spear-carrying soprano of distinction, had found a family in the Wipplingerstrasse who, in exchange for a little help with their three young children, had offered Tessa one of the old servants’ attics. A beautiful room, she thought it, with its views over the roofs of the Inner City and the soaring spire of the Stefansdom.

Now she quickly braided and pinned her hair, washed her hands and face, dressed in her working smock of unbleached linen, and ran downstairs to where the three infant Kugelheimers in their cots greeted her with cries of satisfaction.

During the next half-hour she changed the baby, lugged the three-year-old Klara on to the gigantic, rose-adorned chamber-pot, ran into the kitchen to heat some milk, dressed the four-year-old Franzerl, made coffee for Frau Kugelheimer — and, finally, grabbing a letter from the postman which she thrust unread into her pocket, was safely out into the street.

It was just growing light, the city lifting itself out of sleep. A row of tiny choristers walked across the cobbles to sing Mass in the Peterskirche; the pigeons on the Plague Memorial, safe again after years of being potted at by hungry citizens, began to preen themselves for the day. A baker, pulling up his shutters, called ‘Grüss Gott!’ and Tessa gave him a smile of such radiance that he stood watching her like a man warming himself in a sudden shaft of sun until she turned into the Kärntner-strasse. It never failed her, this sense of awe and wonder at belonging… at working here in this city which had been Schubert’s and Mozart’s, and now was hers.

The Klostern Theatre, which now housed the International Opera Company, had once been the private theatre of a nobleman whose adjoining palace had been pulled down at the time the old ramparts were destroyed and the Ringstrasse built. The auditorium with its enchanted painted ceiling of obese and ecstatic nymphs, its red velvet boxes and gold proscenium arch, invariably wrung a sigh of pleasure from connoisseurs of Austrian high baroque. Backstage, the theatre resembled a cross between the Black Hole of Calcutta and the public lavatory of an abandoned railway terminus. The pit was too small for the orchestra, the manager’s office was a windowless kennel, merely to approach the dimmer board was to take one’s life in one’s hands. Everyone who worked there cursed the place from morning to night and resisted with vituperative ferocity all suggestions of a move to more salubrious quarters.

Tessa let herself in by the stage door, sighing happily at the familiar smell of glue and size and paint and dust. As always she was the first to arrive and the sense of the sleeping theatre, dark and cold, waiting to be brought to life — and by her — was an ever-recurring delight. Today was a particularly exciting day: the last day of Lucia di Lammermoor in which Raisa Romola, losing her reason as only a two-hundred-kilo, red-haired Rumanian soprano knew how, had scored a triumph; then the announcement by Herr Witzler, after curtain down, of the new opera they would begin to rehearse next week.

Quickly she sorted the mail into the appropriate pigeonholes, took the director’s letters upstairs to his office, emptied the mousetraps under his desk, riddled and filled the ancient, rusty stove. Then downstairs again to the front of the house to turn on the light, admit the cleaning ladies and ring the police to inform them that a handbag containing three thousand kroner and a ticket to Karlsbad had been left in row D of the stalls.

Then she hurried back through the orchestra pit, pausing to tidy up the poker school which the trombonists had set up under the stage… up two flights again, round a curving iron staircase to the star soprano’s dressing-room, to change the water for Raisa Romola’s roses, scrub out her dachshund’s feeding bowl and collect for repair the bloodstained Act Three nightdress through which an idiot stage hand had put his foot as the heaving diva waited in the wings to take her curtain call.

And downstairs again to find that the wigmaker, Boris Slatarski, had arrived and was staring gloomily at ‘The Mother’.

Boris was a Bulgarian and thus committed to longevity and yoghurt. The latter he made from a culture of great ethnicity and ripeness which originated in some shepherd-infested village in the Mirrovaroan Hills. Known as ‘The Mother’, it lived in a jamjar on the draining-board of the laundry room, smelling vilely, flocculating, turning blue and generally showing all the signs of the artistic temperament.

‘I don’t like the look of her this morning, Tessa,’ he said now, unwinding his long, yellow face and bald skull from the folds of a gigantic muffler. ‘She’s precipitating much too fast.’ He rummaged in a hamper, ripped the muslin sleeve out of a peasant blouse from The Bartered Bride and began to filter The Mother through it. ‘Have you got the milk yet?’

‘I’m just going,’ said Tessa. She fetched the can, ran to the dairy three streets away, and back, hiding the egg she had managed to wheedle out of the dairyman in a box labelled ‘Spats’.

The theatre was fully awake now. Hammering resounded from the scene dock, pieces of scenery suddenly flew upward. Cries of ‘Where’s Tessa?’ came with increasing frequency — from Frau Pollack, the wardrobe mistress, who wanted to know why Tessa had not brought down the costumes for Tosca, had not sorted out the buckle box, had not made the coffee… from the lighting assistant who wanted her to hold a spot, from the carpenter who had a splinter in his eye.

At eleven the Herr Direktor, Jacob Witzler, arrived and began to go through the pile of bills, of notices threatening to cut off the water, the telephone and the electricity, which constituted his morning mail.

This frog-eyed Moravian Jew, with his ulcer and his despair, quite simply was the International Opera Company. Jacob’s dedication, his sacrifices, his chicanery, cajoling and bullying had steered this unsubsidized company for over twenty years through crisis after financial crisis, through war and inflation and the machinations of his rivals.

In a way the whole thing had been bad luck. Jacob came of a wealthy and not particularly musical family of leather merchants in the Moravian town of Sprotz. His life was marked out almost from birth — a serene progress from bar mitzvah to entry into the family firm, marriage to a nice Jewish girl already selected by his mother, a partnership…

Jacob was deprived of this comfortable future in a single afternoon when at the age of eleven he was taken, scrubbed to the eyeballs and in his sailor suit, to a touring company’s performance of Carmen.

All around him, dragged in by their culture-hungry parents, sat other little boys and girls, Christian and Jewish, Moravian and Czech, wriggling and fidgeting, longing for the interval, thirsting for lemonade, bursting for the lavatory.

Not so Jacob. The Hippopotamus-sized mezzo dropped her castanets, Escamillo fell over his dagger, the orchestra was short of two trumpets, three violins and the timpani. No matter. Alone of all the infants of Moravia Jacob Witzler was struck down, and fatally, by the disease known as Opera.

Now, some thirty years later, his fortune gone, his health ruined, his faith abandoned, he reached for a dyspepsia pill and settled down to work. The claque was clamouring to be paid but that was absurd of course. Raisa would get enough applause tonight; the mad scene always got them and next week they were alternating Tosca with Fledermaus, old war horses both. Frau Kievenholler had put in a perfectly ludicrous claim for cab fares for her harp…

The phone rang: a tenor wanting to audition for the chorus. And rang again: someone was coming round to inspect the fire precautions! And rang again…

At noon Jacob put down his pen and sent for Tessa.

‘Good morning, Herr Witzler.’

The under wardrobe mistress stood respectfully before him. There was a smut on her small and surprisingly serious nose, her hair was coming down and her smock was liberally spattered with paint, but as he looked at the little figure emitting as always an almost epic willingness to be of use, Jacob at once felt better. His blood pressure descended; his ulcer composed itself for sleep.

Allowing Tessa to come and work for him was one of the best things he had done and if the police did come for her one day he, Jacob, was going to fight for her tooth and nail. True, she had obviously lied to him about her age — he doubted if she was twenty, let alone the twenty-three she had laid claim to. Nor had she remembered to respond, within half an hour of her interview, to the surname she had offered him. She appeared to have no relatives to vouch for her, no documents, certainly no references of any sort; that she had run away from some institution in the country seemed clear enough. He had told himself that he was mad to take her on, but he knew this was not true.

Since then his hunch had paid off a thousand times. It was not simply that this fragile looking waif with her earth-brown eyes worked a fifteen-hour day, trotting indefatigably through the labyrinthine corridors with loads which would have tired a mountain pony. Nor, even, that she herself had no personal ambition to sing or act or dance but only and always to help and to learn. It was, perhaps, that her patent ecstasy at being allowed to serve art somehow vindicated his own absurd and obsessive life. He and this foundling were fellow sufferers from the same disease.

‘Have you seen to Miss Romola’s bouquet for tonight?’ he began.

‘Yes, Herr Witzler. It’s ordered and I’m going to fetch it after lunch.’

‘You don’t think we could make it a bit smaller?’

Raisa’s bouquets had been steadily shrinking on the principle of the horse from whose feed one removes each day a single oat. It was Tessa’s opinion, now delicately voiced, that they were down to the stage where the horse was in danger of dropping dead.

‘But I could get Herr Klasky’s buttonhole out of it, I think,’ she said, referring to the conductor, ‘which would save a little?’

‘Good, do that. What about the wine for the party tonight?’

‘It’s just arrived and I’ve put it in the wig oven, very low, to make it chambré.’

‘And you’ve remembered my wife’s reservations at Baden-Baden?’

‘Yes, Herr Witzler. A room for one week from June the eighteenth at the Hotel Park, with a cot for your son.’

Jacob nodded gloomily. He had married Leopoldine Goertl-Eisen after that lady, suspended aloft (and in the act of singing ‘Weie, Wiege, Wage die Welle’) had been horribly precipitated by the snapping of her steel cable on to the stage of the Klostern Theatre during a matinee of Rheingold. If he had espoused the massive, bruised Silesian soprano mainly to stop her from suing the International Opera Company, there was no doubt that the marriage was a success. Understandably, however, his Rhinemaiden’s nerves had been affected. When they gave Rheingold anywhere in Vienna, Jacob was compelled to send her to Baden-Baden and the expense was appalling.

‘Then there’s a tenor auditioning at three,’ he went on. ‘Respini can’t come, so you’ll have to accompany him.’

‘Ah, but I don’t play well enough.’

‘For a tenor you play well enough,’ said Jacob firmly. He sighed. ‘I was wondering about a ballet for Tosca?’

Tessa screwed up her waif-like countenance, pondering. Sylphides in the torture scene? Swans in the prison yard?

Jacob’s efforts to insert a ballet into almost everything were herculean and disinterested since he himself was indifferent to ‘the Dance’. He employed, however, three delectably pretty and available ballet girls known collectively as The Heidis (since two of them were christened thus) in the hope that their presence would lure in the rich patron he so desperately craved.

‘If the Heidis were in the stage box dressed in their tutus with rosebud wreaths and some gauze on their shoulders, you know?’ suggested Tessa. ‘We could keep the lôge light on low above them. Then the gentlemen could see them and if they wished to… afterwards… they could…’

Jacob beamed. ‘Yes! That’s what we’ll do. Now that leaves the new Fledermaus programmes to be fetched from the printers, and I want you to go round and tell Grabenheimer that if I don’t get those poster designs by Friday I’m not interested and if he’s in the Turkish bath, get him out!’

At six the conductor arrived and demanded his button-hole. Zoltan Klasky was a Hungarian with tormented eyes, a shock of long, dark hair and the kind of divine and profound discontent which has sent Magyars through countless centuries galloping westwards and giving everybody hell. He was a brilliant musician who loathed sopranos, tenors and everything that both moved and sang except the occasional nasal and impoverished Gypsy.

Though he conducted even the lightest operettas with maniacal expertise and care, Klasky’s own being was dedicated to the composition of an expressionist opera, now in its seventh year of labour. The libretto of this work, authentically based on a newspaper clipping, concerned the wife of a village policeman who is seduced by a millowner, bears him a son and hangs herself, after which the policeman goes mad and tries to murder the baby and serve it to the millowner in a fricassée.

While Tessa had doubts about the operatic qualities of the fricassée, like the rest of the company she was a staunch believer in Klasky’s opera which was scored for strings, mandolins and thirty percussion instruments and would herald a new era in atonal music drama, when it was at last performed.

Now, however, there was a peremptory screech from the star dressing-room, announcing Raisa Romola’s arrival. Within five minutes, Raisa’s dachshund (who inexplicably had remained uneaten during the hardest years of the war) had made a puddle, the state of her head notes made it impossible for her to go on and the tenor, Pino Mastrini, had accused her of stealing his egg.

Tessa dealt with the dachshund, rushed down to the spats box to fetch the egg so vital to the tenor’s larynx, ran up to the chorus dressing-room to help Lucia’s clansmen with their tartan plaids…

And the curtain went up.

Three hours later Tessa, leaning humbly against an upstage tombstone holding her glass of wine, heard Jacob Witzler announce that their new production would be Debussy’s lyrical masterpiece, Pelleas and Melisande.

The clock was striking two when she let herself back into the house in the Wipplingerstrasse. It was not until she was standing at her attic window, once again brushing her hair, that she remembered the letter which had come that morning and was still unread in the pocket of her smock.

She opened it, noting with approval that her aunt had learned to address her in the way that Tessa had instructed, read it through once, then read it through again.

The news was wholly and absolutely good. It was necessary for Tessa to repeat this to herself with resolution because there was no denying that she did feel… well, a pang, and that her stomach seemed to be plunging about in a rather uncomfortable way. It was rather as though the whole of her childhood had suddenly dropped into a void. But that was absurd, of course; just sentiment and a failure of courage — and anyway she had no choice. The thing to hold on to was that she was free now… free for work, for art, for life!

And opening the window, allowing her long hair to ripple over the sill, the Princess Theresa-Maria of Pfaffenstein leaned her head on her arms, blinked away the foolish tears that threatened her and smiled at the moon.

4

In the breakfast room of Schloss Spittau, watched from the banks of the moat by a pair of moulting swans, Dorothea, Princess of Spittau, was reading a letter.

From the turreted windows of the room, as from all the windows of the castle, one looked out on water. Spittau’s long, low, yellow-stuccoed main front, with its flanking pepper-pot towers, was lapped by the waters of the Neusiedler See, a large, reedy and melancholy lake stretching away to the Hungarian border. The north, west and south sides of the ancient Wasserburg were surrounded by a wide and scummy moat. Only a single causeway connected the castle with the swampy, pool-infested marsh, which in that desolate, aqueous region had to pass for land.

‘Pfaffenstein is sold!’ said the princess now, looking across the table at her son. ‘And well sold. To a foreigner. A millionaire!’

Prince Maximilian of Spittau, thus addressed, momentarily stopped chewing and said, ‘Putzerl will be pleased.’

‘Not only pleased,’ said his mother, ‘but rich. There is no longer anything to wait for. You must act, Maxi. Act!’

Maxi’s blue, poached eyes bulged with a certain apprehension; his vestigial forehead creased into furrows. He was in fact a man of action, having shot a large number of people during the war, and, with the cessation of hostilities, an infinitely larger number of snipe, mallard, teal, godwall, pochard and geese which he pursued virtually from dawn to dusk in punts, rowing boats and waders. Even now his feet, under the table, rested on a huddle of soaking wet pointers, retrievers and setters who had been out with him since sunrise.

But action as understood by his mother was a different thing.

That the prince had been dropped on his head as a baby was unlikely. Kaiser Wilhelm II had attended his christening; a series of starched and iron-willed nurses had handed him from room to room in the gargantuan palace in Schleswig-Holstein, now confiscated by the Allies, in which he had been born. His lack of cerebral matter seemed rather to be inborn, the price he had paid for being related to both Joan the Mad who brought Castile and Aragon to the House of Austria, and to the Emperor Charles II whose Habsburg chin and Bourbon nose had locked in a manner that made the ingestion of food almost impossible. But though his intellectual activity was limited to weekly visits to the village hall in Neusiedl where they showed the latest films from Hollywood, there was nothing unattractive about Maxi. True, his duelling scar had gone awry a little, but enough of it was visible above his left eye to give him a slightly rakish look; his blond moustache waved pleasantly and except when he was dealing with his mother, his expression was amiable and relaxed.

‘I have been very patient with you, Maxi,’ continued his mother, whose nickname ‘The Swan Princess’ referred rather to her beady eye and savage beak than to any grace or beauty, ‘and so have Putzerl’s aunts. But enough is enough. There is going to be a house party at Pfaffenstein in June. Putzerl is sure to be there for that, so you must propose to her formally then and announce your engagement on the spot.’

‘But, Mother, I have proposed to Putzerl three times. When you told me to, on her eighteenth birthday, and then again that spring. And only three months ago, when I was in Vienna, I invited her out for lunch and proposed again. Without you telling me! She doesn’t,’ said Maxi, a trace of pardonable puzzlement in his voice, ‘love me.’

‘Don’t talk like a waiter,’ snapped the princess. ‘Putzerl knows perfectly well that she must marry you. I must say she isn’t quite what I had hoped for from the point of view of character, but her lineage is impeccable, and with the money she brings in from Pfaffenstein we will be able to shore up the east wing and mend the roof. Anyway, no one not bred to the life would fit in at Spittau.’

This was certainly true. Schloss Spittau, almost afloat on water, was not for the faint-hearted. In winter, mist enshrouded it; frozen birds honked drearily on the ice. The coughing of retainers bent double with rheumatism mingled, as spring advanced, with the plopping of evil-eyed pike in the moat. Pieces of stucco fell suddenly into the lake, and in the summer enormous, muscular mosquitoes moved in like the Grande Armée.

Maxi continued to look depressed. He was perfectly aware of the advantages of marrying Putzerl. He liked her. When you took Putzerl out on to the lake there was no need to take a call duck. She could imitate, like no one he had ever met, the cry of a mallard ready to mate. There was no girl who was a better sport than the Princess of Pfaffenstein. But all this proposing got at a man’s pride…

Then suddenly he brightened and pulled at the soft ears of the dog nearest to him, a German pointer with beseeching amber eyes. ‘If I could take the dogs to Pfaffenstein?’ he suggested. ‘To the house party? Don’t you think Putzerl might agree to marry me then? You know how she is about the dogs.’

The princess looked at the five dogs now thumping their wet tails on the floor and trembling with anticipation. She opened her mouth to tell Maxi not to be silly — and closed it again.

For it seemed to her that, for once, Maxi had a point. Whatever her feelings about her intended bridegroom, the Princess of Pfaffenstein really did love the dogs.

‘I cannot zink in French!’ declared Raisa Romola the morning after Jacob’s announcement.

‘There are no tunes in Debussy,’ declared Pino. ‘It is not what my public expects.’

‘I shall go to Schalk!’ stated Raisa — and Jacob blenched. Schalk was the director of Vienna’s most prestigious institution, the heavily subsidized State Opera. Saying ‘Schalk’ to Jacob was like saying ‘Boots’ to a struggling British retail chemist.

Rallying, he launched into an impassioned speech in praise of Debussy’s subtle, impressionistic score, its contrapuntal texture, its throbbing beauty…

The idea of throbbing beautifully had a slightly calming effect on Raisa, who narrowed her greedy almond eyes and said that if Jacob was prepared to consider a bonus, ‘zinking’ in French might just be possible.

To all this Tessa, busy repainting a flat for Tosca in the wings, listened with eager interest. True, there were strange things in Pelleas and Melisande. One never knew, for example, who exactly Melisande was. Was she a mortal or a being from another world? Had she in fact deceived her husband, Gollaud, with his handsome younger brother Pelleas? And why did she keep losing quite so many things down wells — her crown, her golden ball, her wedding ring? But the whole opera, played largely behind a gauze and subtly and romantically lit, was the very stuff of poetry — and modern too.

She was therefore a little disappointed when Boris, spooning yoghurt on to his plate at lunchtime, said gloomily, ‘You know what Pelleas means, don’t you? It means hair. And hair, right now, spells trouble.’

Boris was right. For the outstanding feature of Melisande which makes her mysterious, haunting beauty unforgettable, is her knee-length shimmering, streaming, golden hair. With this hair, as she lets it fall from her window, the lovesick Pelleas besottedly toys; with this hair Gollaud, her jealous husband, humiliates her, pulling her by it back and forth across the stage. The same hair surrounds her, an incandescent aureole, as she lies dying.

Hair for wigs comes traditionally from nuns. Italian nuns, mostly, since the Italians are noted for being both hirsute and religious, and postulants by the hundred are shorn to become brides of Christ. But her Italian possessions had been wrested from Austria, as had Moravia, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Yugoslavia and all the other countries which had once humbly supplied the capital with everything from paprika to the tresses of their young girls. Of late, Boris had been driven to do business with the local convents, which had been anything but easy — with the fall of the monarchy and the urgings of the new republic, the religious vocation of Vienna’s jeunes filles had declined disastrously.

Any hope that they would get away with horsehair dipped in peroxide, or an old wig from Meistersinger, was dispelled at the first rehearsal. Max Regensburg, the young director called in for the production, was a realist through and through. ‘This Melisande must be flesh and blood,’ he declared, and the company, envisaging Raisa’s bulk, felt he had a point.