DEDICATION

For Leslyn, John, and Katea.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Special thanks to Evelyn Kriete, John D. Mason,

Neil Jordan, Christopher Mello, Charles Shanley, and Eric Strauss.

PREFACE, by Alec Nevala-Lee

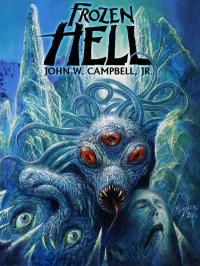

The greatest science fiction horror story of all time opens with the accidental discovery of a relic that has gone undisturbed for ages. Frozen Hell was unearthed in much the same way, although its reappearance was somewhat less dramatic. Instead of the Antarctic ice, it resided in an offsite storage facility used by Houghton Library at Harvard, and it wasn’t detected through a magnetic anomaly, but through a line in a letter and an obscure catalog entry. It went overlooked for six decades, rather than 20 million years, which was still long enough for it to be forgotten. And instead of an extraterrestrial spacecraft, it lay within a carton of a few dozen manila folders, labeled lightly in pencil, that contained the bulk of the fiction of John W. Campbell, Jr., and Don A. Stuart, who somehow were the same man.

When you glance through the browned typewriter carbons inside the box, you find many titles that only the most dedicated science fiction fan would recognize. Among the manuscripts are drafts of the superscience sagas, such as “Uncertainty” and The Mightiest Machine, that Campbell cranked out in the ’30s under his own name, as well as other works, notably the novel The Moon is Hell, that wouldn’t appear in print until much later. There are also the vastly superior stories that he wrote as Don A. Stuart, including early versions of “Night,” “Dead Knowledge,” and “Forgetfulness,” and a few efforts—“The Bridge of One Crossing,” “The Gods Laugh Twice,” “Silence”—that he never published at all. One precious folder holds a copy of “Beyond the Door,” the only known work of fiction by his remarkable wife Doña.

But two folders—labeled “Frozen Hell” and “Pandora”—stand out from the rest. One contains the first 20 pages of a story in clean typescript, a fair copy that was presumably prepared by Doña, who was a better typist than her husband. The other holds 112 pages of a complete rough draft, with typographical errors and misspellings that suggest that it was typed by Campbell, along with numerous corrections in the author’s hand. A cover page bears the alternative titles “Frozen Hell” or “Pandora,” one typewritten, the other written in small capitals, and a note indicates that the manuscript was meant for Argosy, the leading pulp magazine of its era.

The pages that follow correspond to no published work, although some readers might recognize the character named McReady, as well as the setting on an icy plateau in Antarctica. Reading further, they might start to suspect the truth, especially after encountering the buried spaceship with its horrifying passenger inside. After about forty pages, as familiar lines appear with greater frequency, many would know for sure that this was no ordinary document—and even if they didn’t recognize it from context, its significance would be made clear by a penciled note on the upper corner of the first page of the fair copy: “Version of Who Goes There?”

Frozen Hell is a dramatically longer and more detailed version of one of the most famous science fiction stories ever written, which remains best known among the general public for its cinematic adaptations as The Thing. Its lengthy opening section, which was cut before publication, is more than worthy of the rest—Campbell was still in his twenties, but under the name Don A. Stuart, he was perhaps the most admired pulp science fiction writer of his time. Another folder contains a set of false starts for the same story, with at least five different openings told from various points of view, which reflects the care that Campbell put into its construction. He was feeling his way into it, and although most of his singular career still lay in the future, part of him may have sensed that this was the best story that he would ever write.

Campbell was only twenty-five when he came up with the idea that that evolved into “Who Goes There?” In 1936, he was about to start work as a secretary at Mack Truck in New Jersey, having failed to land the research position that he had wanted after college. He was a popular writer in the pulps, and in a casual conversation with an organic chemist, he became interested in the problem of how to tell whether an alien life form was a plant or an animal. As he explained to his friend Robert Swisher, he proceeded from there to the notion of organisms that “could alter their form, animal to vegetable, or vice versa, as the conditions of their environment momentarily required. This led to the idea of an intelligent animal having this property.”

As Robert Silverberg notes in the introduction that follows, Campbell initially wrote up the premise as a humorous throwaway, “Brain Stealers of Mars,” which he sold for $80 to Mort Weisinger at Thrilling Wonder Stories. Yet he continued to mull over the underlying idea, and after discussing it with Jack Byrne, the editor of Argosy, he reworked it into an ambitious horror story titled Frozen Hell. Decades afterward, he told the author James H. Schmitz that once he figured out the premise, setting, and first scene, the rest was easy, although finding the right opening had been a challenge: “This was where I sweated out things and made false starts.” In the end, however, Byrne passed, and Campbell decided to try it on the editor of Astounding Science Fiction, F. Orlin Tremaine, whom he saw on October 5, 1937.

At the meeting, Campbell was offered the editorship of Astounding instead. It was an unforeseen development that would change his life forever—but he didn’t forget Frozen Hell. His own magazine was the obvious place for it, but Tremaine still retained editorial control. In January 1938, Campbell revised the story with input from Tremaine and Frank Blackwell, the editor-in-chief of the publishing firm Street & Smith. This was evidently when the original opening was cut, as Campbell implied to Swisher: “I rewrote the first third of Frozen Hell, and have hopes Tremaine will take it.” “Who Goes There?” finally appeared in the August 1938 issue, credited to Don A. Stuart, and the full draft of Frozen Hell was quietly put away.

Eight decades later, the manuscript unexpectedly resurfaced. In 2017, I was working on the biography Astounding: John W. Campbell, Isaac Asimov, Robert A. Heinlein, L. Ron Hubbard, and the Golden Age of Science Fiction. In the course of my research, I had to review thousands of pages of correspondence, and I found a letter that had been sent to Campbell on March 2, 1966 by Howard L. Applegate, the administrator of manuscripts at Syracuse University. The library was building a science fiction collection that would ultimately include the papers of such figures as Hugo Gernsback, Forrest J Ackerman, and Frederik Pohl, and Applegate wrote to ask if Campbell would be interested in contributing his archive.

Campbell responded on March 16 to politely decline: “Sorry…but the Harvard Library got all the old manuscripts I had about eight years ago! Since I stopped writing stories when I became editor of Astounding-Analog, I haven’t produced any manuscripts since 1938.… So…sorry, but any scholarly would-be biographers are going to have a tough time finding any useful documentation on me! I just didn’t keep the records!” Since I was currently engaged in writing just such a biography, I read this passage with unusual interest—and Campbell’s belief about the lack of primary sources turned out to be fortunately off the mark.

But I was even more intrigued by the reference to Harvard. At that point, I had been working on the book for over a year, and I had never heard of any such archive. Long afterward, I noticed a passing mention in a letter that Campbell wrote to Swisher, who had been storing many of the editor’s drafts, on October 7, 1957: “The manuscripts, Bob, will be taken up to Harvard on our next trip. Harvard’s started a science fiction collection, and is definitely interested in it as a development of American culture. They’re collecting books, magazines, manuscripts, etc.” But I didn’t see this until later, and as far as I knew, no other scholar had ever referred to these papers.

When I checked the online catalog of the Harvard Library system, I found them—but I had to look closely. A search for Campbell’s name generated numerous results, but it was only after scrolling to the fourth page, past dozens of marginally relevant listings, that I saw the entry that I wanted: “John Wood Campbell compositions, ca. 1935-1939 and undated.” After I contacted the library, I received a list of the folders inside, one of which was labeled “Frozen Hell.” I knew from Campbell’s correspondence that this was the working title of “Who Goes There?,” and I immediately wanted a closer look. Since I was unable to travel to Cambridge, Massachusetts in person, I hired a research assistant to copy the manuscripts and send me the scanned images.

As soon as I received the copies on my end, “Frozen Hell” was the first file that I examined. At that point, I was hoping to find little more than a draft of “Who Goes There?” with a few variations from the published text. When I realized how much had been cut, I was amazed—and to the best of my knowledge, no one else alive ever knew that the story had been reworked so completely. (Going back over Campbell’s correspondence, I did find a reference to Doña typing up the draft, “40,000 words of it,” but it was easy to overlook.) I reached out to Campbell’s daughter, Leslyn Randazzo, and she pointed me to John Betancourt, who handled the rights for the estate. The result is the book that you hold in your hands.

Over the last year, I’ve occasionally wondered whether Campbell would have wanted this version to be read. He personally edited Frozen Hell for publication, and the decision to cut the story to emphasize the horror element was unquestionably sound. Campbell had agonized over the opening, and he advised another young writer years later: “Asimov, when you have trouble with the beginning of the story, that is because you are starting in the wrong place, and almost certainly too soon. Pick out a later point in the story and begin again.” He had ruthlessly cut the openings of several of his own stories, including “Night” and “Dead Knowledge,” and “Who Goes There?” certainly didn’t suffer from the change.

But he also appears to have liked the original draft. He told Swisher that it gave him “more fun” than anything else he had ever written, and he cut the beginning only after consulting with Blackwell and Tremaine. The quality of the excised material is on much the same level as the rest, and both versions have their merits. “Who Goes There?” is darker and more focused, but there’s something very effective—and oddly modern—in how Frozen Hell abruptly shifts genres from adventure to horror. It drastically alters the tone and effect of the overall story, and the result is worth reading as more than just a curiosity.

Finally, the obvious care that Campbell took to preserve this manuscript—and all of his discarded openings—implies that he thought that it was worth saving. Campbell was a man of tremendous ambition, and he might have had mixed feelings at the idea that his most famous work would be one that he wrote in his twenties. Yet he undoubtedly wanted to be remembered after his death, and I think that he would be gratified by the excitement over Frozen Hell. Every version of this story is about a discovery that would have been better left unmade, as reflected in the third title, “Pandora,” that its author seems to have considered for it. But I suspect that Campbell would be pleased that this particular box was found and opened.

INTRODUCTION, by Robert Silverberg

The novella “Who Goes There?” by John W. Campbell, Jr., is one of the most famous science-fiction horror stories ever written. When it first appeared, in the August 1938 issue of Astounding Science Fiction, the magazine that the 28-year-old Campbell had been editing for less than a year, it established itself immediately as a classic work. Along with Robert A. Heinlein’s “By His Boot-straps,” Lester del Rey’s “Nerves,” and Isaac Asimov’s “Nightfall,” it was one of the four anchoring stories of the 1946 anthology Adventures in Time and Space, a book still in print after more than seventy years that is the definitive collection of Golden Age science fiction (most of which came from Campbell’s own magazine.) Campbell’s story finished in first place in the voting when the Science Fiction Writers of America chose the stories for its 1971 Hall of Fame anthology of the greatest science-fiction novellas. It has been filmed three times and in 2014 the World Science Fiction Convention gave it a retroactive Hugo award as the best novella of 1938. I can never forget my own first reading of it, in Adventures in Time and Space, when I was thirteen: it had an overwhelming impact for me and has never failed, in many rereadings over the decades, to generate the same sort of excitement I felt in that first encounter. “Who Goes There” is a masterpiece, the work of a writer in full command of his powers.

Campbell would go on to edit Astounding and its successor Analog Science Fiction for 33 more years, publishing, along the way, the best work of such writers as Heinlein, Asimov, Theodore Sturgeon, Henry Kuttner, L. Ron Hubbard, A.E. van Vogt, L. Sprague de Camp, and many another mighty figure of that formative period in the history of science fiction. He was a mighty figure himself, physically imposing, a big man with a commanding voice, still the dominant editor of the field when I first entered his office, with more than a little trepidation, as a new young writer in 1955. Though he no longer wrote science fiction himself—his editorial responsibilities kept him too busy for that—he was a fountain of ideas, sharing them freely with the authors who visited them (myself included, though I was just a twenty-year-old beginner.)

What I had trouble realizing, as a novice writer standing in the presence of the great John Campbell in 1955, was that there had been a time when Campbell himself was a novice, young, uncertain, struggling to earn a living as a writer. Like me, he had begun writing science fiction in his teens.

And, like me, he had won editorial acceptance right away. The editor who took his first story promptly lost it, though, and since Campbell had no other copy of it, it was lost forever. But a second story, “When the Atoms Failed,” afforded him his professional debut in the January 1930 issue of Amazing Stories. He was nineteen years old. The editor’s introduction declared, “Our new author, who is a student at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, shows marvelous ability at combining science with romance, evolving a piece of fiction of real scientific and literary value.”

Young Campbell followed it swiftly with a string of lengthy stories—“The Black Star Passes,” “Piracy Preferred,” “Islands of Space,” “Invaders from the Infinite,” and others, which established him, while he was still in his early 20s, as the second most popular science-fiction writer of the time, behind only Dr. E.E. Smith, the author of vast and ponderous space epics that Campbell had carefully imitated. By 1934, when his serialized novel “The Mightiest Machine” appeared in Astounding (even then the leading magazine of the field), he was looked upon by readers more highly than even Smith himself.

The problem was that this early success did not translate itself into any sort of financial security. The science-fiction magazines of that early day paid a cent a word at best, and Campbell’s primary market, Amazing Stories, paid on publication, which meant he could wait as long as two years before seeing any return on his work. And, major figure that he was to science-fiction readers, he was not doing well in the mundane world. He had flunked out of M.I.T. in his junior year after three times failing to pass his German course, a required subject. After that embarrassing debacle he enrolled at Duke University, where, after an intensive summer course in German, he finally was able to come away with a degree in 1934. By then he had married, and, unable to earn a real-world living from his writing, he had embarked on a series of undistinguished jobs—car salesman, air-conditioner salesman, and a secretarial job at Mack Trucks, among others—but never managed to keep any of them very long.

His writing career was presenting difficulties, too. F. Orlin Tremaine, the astute editor of Astounding, had begun to think that readers were tiring of the sort of super-science tales that had brought Campbell his early fame, wordy epics in which grim, methodical supermen repeatedly saved the world from menacing aliens by mastering, with the greatest of ease, such things as faster—than-light travel, the fabrication of matter-destroying rays, the release of atomic energy, and the penetration of hyperspace. In 1935 Campbell turned in three lengthy sequels to The Mightiest Machine and Tremaine rejected all three. He had no place else to sell them, since Amazing Stories already was holding a novel of his for which it had not yet paid, and Wonder Stories, the third of the three science-fiction magazines of the day, was in financial trouble and buying very little new material, and the failure of the three novellas left him in harsh financial circumstances.

Having exhausted the possibilities of the high-tech galactic epic on which he had built his fame, Campbell somewhat desperately began to reposition himself as a writer. At Tremaine’s suggestion he began a series of moody, poetic stories of the far future under the pseudonym of “Don A. Stuart”. These, beginning with the haunting, visionary “Twilight” and going on to “Blindness,” “The Machine,” “Night,” and several others, were an immediate success with the readers of Astounding. Seeking to escape from the low—pay world of the science-fiction pulps, Campbell looked toward Argosy, a weekly magazine of general fiction noted for publishing fantastic novels by such writers as Edgar Rice Burroughs and A. Merritt and paying quite well for them. He tried them with Frozen Hell, a tight, tense novel about a lunar expedition stranded on the Moon, which had not interested Tremaine. But it was written in diary form, a mode not ideally suited to the demands of the magazine readers of the day for fast-paced fiction, and neither Argosy nor any other magazine cared for it. (It finally saw print in 1951, published by a small press under the title of The Moon is Hell.)With the heavy-science epic no longer marketable, and the moody Don A. Stuart stories insufficient to support him by themselves, Campbell needed to find something different to write, and, with the help of a new editor named Mort Weisinger, he undertook a series of potboilers in the comic mode of Stanley G. Weinbaum, an immensely popular writer who had died in 1935 after a brief, spectacular career. Weinbaum was a natural storyteller with a distinctive light touch, and his work had won him a wide following, beginning in 1934 in Hugo Gernsback’s Wonder Stories with “A Martian Odyssey,” still often reprinted in anthologies, and continuing until his death eighteen months later. The sales of Wonder Stories were approaching the vanishing point early in 1936, and Gernsback sold it to the aptly named Standard Magazines, a chain of pulps that dealt in simply told action-adventure stories for young readers, which renamed it Thrilling Wonder Stories. Weisinger, a long-time science-fiction fan who was put in charge, was aware that Weinbaum had been the old magazine’s readers’ favorite, and, with Weinbaum no longer available, he called in John Campbell and asked him to write a series of stories in the Weinbaum manner.

Campbell, hard pressed to pay his rent at the time, eagerly complied. The usual Weinbaum plot had involved space explorers who become entangled in some complicated manner with alien beings, and though Campbell’s published work had been anything but lighthearted up until then, he proposed a group of breezy Weinbaumian tales featuring two space travelers named Penton and Blake. The first one Campbell turned in, in the spring of 1936, was “Imitation,” to which Weisinger gave the livelier title of “Brain-Stealers of Mars” when he ran it in the December 1936 issue of Thrilling Wonder Stories.

“Brain-Stealers” begins in a cheerfully Weinbaumian way. Penton and Blake, having caused some trouble on Earth by touching off an atomic explosion in the course of an experiment, jump into a spaceship and take off for Mars. They are puzzled to find what look like Japanese maple trees there, and also weirder-looking plants, weird plants and animals having been a Weinbaum specialty. Before long things get stranger: the Japanese maples change form, becoming something very alien; and then Penton and Blake find themselves surrounded by some twenty duplicate Pentons and Blakes, identical in all respects, including voices, personalities, and memories.

They respond fairly casually at first, Blake shooting one of the extra Pentons with his atomic pistol when it begins to show signs of further physical change, then eliminating some of the others. Then centaur-like creatures show up—Martian natives, quite friendly, who explain telepathically that the shapeshifters are creatures called thushol that have the power of transforming themselves into perfect imitations of other life-forms.

“How do you tell them from the thing they’re imitating?” Penton asks.

“It used to bother us because we couldn’t,” one of the centaurs replies. “But it doesn’t any more.”

“I know—but how do you tell them apart? Do you do it by mind-reading?”

“Oh, no. We don’t try to tell them apart. That way they don’t bother us any more.”

The centaurs are untroubled by the presence of shapeshifters in their midst (“If the imitation is so perfect we can’t tell the difference, what’s the difference?”), but Penton and Blake see real danger in it, and abruptly what had been an amiable Weinbaumian romp takes on a much darker tone. What if some future explorer from Earth inadvertently brings a thushol back from Mars? “If they eat like an amoeba,” Penton says, “God help us. If you maroon one on a desert island, it will turn into a fish, and swim home. If you put it in jail it will turn into a snake and go down the drain pipe. If you dump it in the desert it will turn into a cactus and get along real nice, thank you.” The thushol, he saw, were infinitely adaptive creatures that could conquer and absorb all enemies, and if they somehow managed to get to Earth it would mean the end of the human race.

The thing to do, they realize, is to return to Earth immediately. But all about them are duplicate Pentons and Blakes, indistinguishable from the originals. How can each of the authentic Earthmen be certain that no thushol has taken the place of the other one for the return voyage? Some reliable way of determining authenticity is needed; and after a time Penton devises one, an ingenious biological test, quite Weinbaumian in nature, that allows them to identify and destroy all the false Pentons and Blakes in their midst. The world is saved and the story ends with a wry Weinbaumian punchline.

“Brain-Stealers of Mars” was no more than a clever piece of hackwork nicely suited for the undemanding requirements of \Thrilling Wonder Stories. Campbell quickly followed it with further Penton and Blake adventures for Weisinger. But he still yearned to break away from the low-paying science-fiction magazines, and in the spring of 1937, he paid a call on Jack Byrne, the editor of Argosy, who had let it be known that he wanted to publish more science fiction but had no idea where to find it.

Campbell told of his meeting with Byrne in a letter to his best friend, Robert Swisher, a pharmaceutical chemist and avid science-fiction reader who lived in a suburb of Boston: “Byrne was offered a collection of story ideas, including the human mutant one, but he liked best the idea of the Thusol [sic] from ‘Brain-Stealers of Mars’. I told him I’d done it in a humorous vein—comic opera possibilities of course obvious—for Wonder. Would he like it done in a horror vein, with the setting Earth instead of Mars.… He would. Wants 24,000, 35,000, or 44,000 words of it. They pay 1-1/4 to 1-1/2 cents a word for their stuff—34,000 of them sound interesting.… Byrne said he didn’t think the Thusol should be let loose on Earth—inject ’em into a movie colony on location—or on a desert island or something—in a city would be too darned much, and too impersonal. (Think he’s right myself.) The horror angle there is—they might get loose.… I finally decided they get loose in an Antarctic expedition, when one was thawed out of the Antarctic ice.…Starts with the finding of things. Biologist puts frozen beast in the one cabin that’s kept warm all night, so that it can thaw out for dissection; the hut where the meteor observer sits alone all night. Something stirs behind him—he turns.

“The next morning—he finds animal gone. Great curiosity. Meteor man says he didn’t hear a sound all night—wanders off— He’s missing later, but they find a cow in the passage, half molten, and a three-foot image of meteor man growing from it—it runs—they learn the horrible truth.”

Thus was the future classic “Who Goes There?” born. But there was many a step, and a misstep or two, between the initiation of the idea and the final great story.

Campbell set out immediately to write it, working at his usual high speed, and by June, 1937 had done his new story employing the shapeshifting monster theme, setting it on an Antarctic base that he envisioned after reading the account of Admiral Richard E. Byrd’s recent expedition to the south polar regions. He may also have been influenced to some degree by H.P. Lovecraft’s novella “At the Mountains of Madness,” which had been serialized in Astounding in 1936—a powerful tale with an Antarctic setting, although Lovecraft’s style and narrative approach had very little in common with Campbell’s. A third factor that may have enabled Campbell to intensify the impact of his shapeshifter plot was a strange autobiographical one that Campbell revealed many years later: his mother had been one of a pair of identical twins, so much like each other that as a small boy he was unable to tell them apart. The sisters disliked each other and the aunt disliked her nephew, and on occasion he would come home from school to seek comfort from his mother for some mishap that day, only to be coldly rebuffed by a woman who was actually his aunt.

He called the new story Frozen Hell, thus recycling the title of his unsold and apparently unsalable novel of lunar exploration of the year before. His intended market was Argosy, but when Jack Byrne of Argosy called him into the office to discuss the story, it was to tell him of its rejection. As Campbell wrote to his friend Swisher, Byrne had said “‘it’s a good yarn, good idea, good writing. But there aren’t any characters in it. It’s got a bunch of minor characters, but no major characters.’ Quite true—I can see that. Hence, most of the conference revolved about how to bring out characters.” In the 15-minute discussion that followed, Byrne’s associate editor, George Post, suggested that what the story needed was a female character. Campbell was willing to give that a try, but saw no way to make a woman part of a 1930s Antarctic expedition. He went home promising to study the story and find some way to make it acceptable.

Campbell was destined to become one of the most capable editors in the history of science fiction, and I can testify from my own experience of his editorial skills, eighteen years after the time he was working on his Antarctic horror tale, that he had a superb sense of story construction and knew how to guide the author of a not-quite-right work toward a satisfying revision. Those skills must already have been well developed even in 1937, when, after all, he had been writing for the science-fiction magazines for eight years and had published a great many widely admired stories.

We know how he went about shaping the Antarctic novel he called Frozen Hell into the masterly novella “Who Goes There?,” because we have the text of Frozen Hell available for comparison today. No one had given much thought to that original version for many years, though when the Swisher-Campbell letters were published in a limited edition in 2011 it was mentioned; but even then the manuscript was believed to be lost. A few years later, though, Alec Nevala-Lee, while doing research for his book Astounding (an account of Campbell’s influence on science fiction, and in particular of his editorial relationships with Isaac Asimov, Robert A. Heinlein, and L. Ron Hubbard), came upon a reference in Campbell’s correspondence file to a box of manuscripts that Campbell had deposited in the Harvard University library. Nevala-Lee eventually discovered the forgotten box in Harvard’s Houghton Library, and there within it was the Antarctic version of Frozen Hell, now brought forth at last for 21st-century readers.

Comparing the rediscovered manuscript with the published novella is an instructive lesson in Campbell’s growing mastery of his craft. What is immediately apparent when putting one against the other is that Campbell the future editor must have realized at once that he had opened the story in the wrong place. Frozen Hell starts with the discovery of an alien spaceship buried in the Antarctic ice cap, but, though Campbell tells of it in the crisp, efficient prose that had become his professional hallmark, and describes the south polar setting with a vividness worthy of Admiral Byrd himself (“The northern horizon was barely washed with rose and crimson and green, the southern horizon black mystery sweeping off to the pole.…”), nothing that he tells us in the first three chapters of the original version drives the reader toward the terrifying situation that is the mainspring of the novella’s plot. That situation is foreshadowed, in a heavy-handed way, toward the end of Chapter Three, when McReady, who is as close to a protagonist as the story will have, tells of a nightmare he has had (which recapitulates the story line that Campbell had used in “Brain-Stealers of Mars”). In his dream the Antarctic explorers have brought forth a strange frozen creature from the ice that manifests shapechanging powers. “It could turn into anything, or anybody.… It had a secret, unholy knowledge of life and life-stuff, protoplasm, gained through ages of experiment and thought. That is, it wasn’t bound to any form or size or shape, but could mold its very blood and flesh and smallest cell to not merely imitate but duplicate the blood and flesh and cells of any other thing it chose. And read the thoughts, the habits, the mind of anyone.”

This is, of course, the nightmarish central situation we will ultimately encounter in “Who Goes There?” But laying it out in this blunt way, in flat exposition and in the arm’s-length reality of a retold dream, must have struck Campbell, upon re-reading, as a woefully ineffective way of setting up his plot. There were other flaws in the longer version, too. On page 12 we find a scientist named Norris explaining something to McReady, in two paragraphs of leaden dialogue, that McReady surely already knows. (“To a compass the magnetic South Pole is what the true south pole 1,200 miles away is to the geographer; any direction is due north. There is no horizontal pull, the shortest way north is straight down.…”) And on page 35 the Antarctic explorers accidentally destroy the buried alien spaceship in a clumsy attempt to excavate it, though it would have been much more plausible to leave it in the ice to be recovered by some later, and better-equipped, expedition.

In his revision Campbell solved all these problems simply by cutting the first three chapters, getting rid of the slow opening sequence and the lecture on geomagnetism, and brushing McReady’s dream and the destruction of the spaceship into quick flashbacks where they would be less obtrusive. To set events in motion now he wrote two new paragraphs that constitute one of the most potent story openings in the history of science fiction:

The place stank. A queer, mingled stench that only the ice-buried cabins of an Antarctic camp know, compounded of reeking human sweat, and the heavy, fish-oil stench of melted seal blubber. An overtone of liniment combatted the musty smell of sweat-and-snow-drenched furs. The acrid odor of burnt cooking fat, and the animal, not-unpleasant smell of dogs, diluted by time, hung in the air.

Lingering odors of machine oil contrasted sharply with the taint of harness dressing and leather. Yet, somehow, through all that reek of human beings and their associates—dogs, machines, and cooking—came another taint. It was a queer, neck-ruffling thing, a faintest suggestion of an odor alien among the smells of industry and life. And it was a life-smell. But it came from the thing that lay bound with cord and tarpaulin on the table, dripping slowly, methodically over the heavy planks, dank and gaunt under the unshielded glare of the electric light.

It is all there, from the harsh crackle of that three-word opening sentence through the sensory pressure of the reek of sweat and blubber to the presence of some mysterious alien thing strapped up in a tarpaulin on a table. And from that point on the pace is unrelenting, as horror upon horror is manifested, and, ultimately, the survivors conquer the alien menace a way analogous to the resolution of the similar problem posed in “Brain-Stealers of Mars,” but this time in no way comic.

The final version of the story, now called “Who Goes There?,” is essentially the last five chapters of the eight-chapter Frozen Hell, with only minor revisions. “I had more fun writing that story than I’ve gotten out of any I ever turned out,” he said in a letter to Robert Swisher. Though he must have known that the revised story was far superior to the original, Campbell was un- certain enough about it to show the manuscript to his wife Doña, who frequently served as his first reader. “Doña says I clicked,” he told Swisher jubilantly. He showed it also to his friend Mort Weisinger of Thrilling Wonder Stories. Weisinger was impressed also, though he grumbled about Campbells’ recycling of the plot idea of “Brain-Stealers of Mars,” which he had published. “Mort got peeved,” Campbell reported to Swisher. “Seems he has an idea he bought the idea as well as the story, when he bought ‘Brain-Stealers of Mars’. I disagree. We left with no blows exchanged.”

Weisinger did not want the story for Thrilling Wonder Stories—he needed material that adhered more closely to pulp-magazine formulas—and it is not clear whether Campbell submitted it to Argosy, which had suggested he rewrite the longer version in the first place. But late in the summer of 1937 he offered it to F. Orlin Tremaine of Astounding. A strange thing happened, though, while the manuscript was still sitting on Tremaine’s desk. In September, 1937, Street & Smith, the publishers of Astounding, underwent a vast corporate shakeup. Ten of its magazines were discontinued, some high managerial figures were dismissed, and Tremaine was moved up into the post of executive editor of the entire magazine chain, leaving Astounding itself without an editor. And at the beginning of October Tremaine asked Campbell to be his replacement. With astonishing swiftness Campbell found himself the editor of the very magazine to which “Who Goes There?” was currently under submission.

Science-fiction fandom was amazed that Campbell, who was looked upon as a titan among writers, would abandon a brilliant writing career to take on a mere editorial job. From Campbell’s point of view the situation looked quite different. He had depended, since leaving college in 1934, on the uncertain income from three science-fiction magazines that paid, at best, a cent a word for their material. He had held a series of uninteresting mundane jobs, affording satisfaction neither to himself nor to his various employers. Science fiction was central to his life, and the job at Astounding would provide a steady income while allowing him to immerse himself in the field that he loved. And, in fact, this was the last job Campbell ever would have: he would hold it to the end of his days, in 1971.

He could not, however, buy his new novella on his own say-so. As editor he was at that time merely a first reader, and needed Tremaine’s approval for anything he acquired; but “Who Goes There?” presented no problems for Tremaine, and the story was purchased and put into the schedule for publication in an early issue. Campbell would run it not under his own name but with the “Don A. Stuart” pseudonym; but by then the identity of “Stuart” was pretty much an open secret among science-fiction readers.

By the time “Who Goes There?” appeared, in the August 1938 Astounding, Campbell no longer had Orlin Tremaine looking over his shoulder. Tremaine was not comfortable in his new managerial post and Street & Smith was not comfortable with him, and by May, 1938, he was gone, ostensibly by resignation but actually having been dismissed by Street & Smith’s new president, “with the result,” Campbell told Swisher, “that I am now all of Astounding. There isn’t any more. No assistant, no readers, no nobody.” With Tremaine out of the picture Campbell had put the magazine through an extensive makeover, going about it in the dynamic manner that would mark his entire long editorial career.

One of the first things Campbell did was to change the magazine’s name from Astounding Stories to Astounding Science Fiction with the March 1938 issue. He loathed that gaudy adjective “astounding,” but could not then get rid of it; this was the best he could do in 1938. (He finally dumped it in 1960 in favor of Analog Science Fiction, the name it still bears.) The cover format underwent a redesign, and a splendid new cover artist, Hubert Rogers, arrived and created, month after month, visions of the shining future that were in line with Campbell’s own. Campbell had inherited a considerable backlog of stories from Tremaine, which was not a serious problem, since Tremaine had been an excellent editor. But Campbell, a younger man firmly grounded in the twentieth-century, wanted the magazine’s fiction to take a fresher approach, and a change in tone became apparent within a few months. Some of the stories he bought were by long-time Tremaine contributors like Jack Williamson, Nat Schachner, and Raymond Z. Gallun, but, month by month, new names appeared on the contents page—L. Sprague de Camp, Lester del Rey, Theodore Sturgeon, Robert A. Heinlein, Isaac Asimov, A.E. van Vogt, and many others, who under Campbell’s editorial guidance would transform the way science fiction was written forever. It was a radical and memorable metamorphosis, and knowledgeable readers today still look back on the era of Astounding Science Fiction of Campbell’s early years as a golden age.

Of all the Golden Age classics, Campbell’s own “Who Goes There?” has long held a key position, and those of us who have revered that story since our first acquaintance with it owe Alec Nevala-Lee deep gratitude for his excavation of the earlier version of that masterpiece. Not only is Frozen Hell of major interest by the way it shows a great s-f writer gaining total mastery of his craft and the nascent great editor that was the John W. Campbell of 1937 demonstrating why the magazine he would shortly be editing defined the modern era of science fiction, but the original version itself, for all its flaws, is exciting in its own right, providing character development and background detail that Campbell, for the sake of telling a swifter story, eliminated from his final draft. It is, of itself, a treasure. We are lucky to have it.

FROZEN HELL, by John W. Campbell, Jr.

CHAPTER ONE

McReady stuck his head barely above the surface, and looked off toward the north. The sun was a dulled wheel of light barely hanging on the horizon of an ice-bound plateau. The wind that had started with a mad slide down the foothills of the South Polar Plateau 800 miles to the south, and strengthened in its sweep across the glacier-locked continent, had lost nothing of its edge. Thirty miles of wind from the southeast, honed by 75 degrees of frost.

It carried a few sharp-edged, fine grains of ice, mementoes of their digging three days before. It wasn’t drift. The high, bald plateau had been scoured free of drift-snow ages ago; the unending winds had swept a huge patch 10 miles in diameter as bald as a buzzard’s throat.

McReady grinned behind his face-muffling scarf and adjusted his goggles. The physicists could be relied on to pick a place like this to roost. A quarter mile away, the orange paint of the tractor and the lesser blot of its trailing sledge loomed out of a dusk which represented two o’clock on a spring afternoon—October, in fact. October 2, 1939.

Barclay was running toward him, downwind like a man going down hill, his ice crampons sending up showers of ice chips that swirled away in front of him in the wind. Suddenly his feet went out from under him, and the wind tossed him along for ten yards before he caught himself and he climbed to his feet again. The padding of his coat and many layers of thermal clothing protected him from serious injury.

When Barclay reached the Secondary Magnetic Station, the wind shied a larger chip of ice against his goggles. It might have blinded him without their protection. McReady stepped back, giving him room. Barclay cursed, ducked through the flapping canvas door, and climbed backwards down the small ladder into the Station’s antechamber.

“Christ, Mac,” he said, voice dulled by layers of wool, “do you like this weather so much you’ve got to stand out in it?”

McReady smiled slowly. The sky was cloudless; only the drumming organ music of the wind and the wash like the slipstream of a transport plane suggested a storm.

“This place fascinates me. As a meteorologist, I’m always interested in storms. Anywhere else I’ve ever been, I’d call this a storm, but it’s been blowing steadily for four consecutive days, ever since we came here. The barometer hit 23 inches on the way down. I wonder…what would a real storm be out here?”

Barclay inched his head up above the level of the blue ice, into which they had cut the Secondary Magnetic Station. His goggles flashed twin reflections of the white of the sun

“If there were water,” Barclay mused, “it would be hell and high water. Dutton at Big Magnet reported fine, clear skies, wind SW 5. Bah! This is the world’s worst spot for a camp. I’ve some notes for them from Big Magnet that may keep them underground for a while.”

McReady reached up and tied shut the outer canvas door-flap. Then they went through the next door—a wood one—into the Station proper.

The roof of tent canvas laid across chicken wire and slats, weighted down by chunks of ice cut out in the making, rested across bolted uprights. Fiberboard panels made up the side walls. A copper stove, in the center of the room, succeeded in bringing the upper layer of air to about 80 degrees, but the wooden floor had a tracery of ice crystals scattered over it. Wind growled threats down the stove pipe.

Norris and Vane sat on the edge of Norris’s bunk, working over a sheaf of data sheets. Above the table, they were clad in long-sleeved grey woolen underwear and shoulder-length hair. They had on light khaki trousers, and the clothing increased in thickness as it approached the floor, ending in knee-length wool socks, and heavy, fur-lined boots. Perishable stores were kept frozen on the floor, while dry cells, beer, and food stock took to the temperate climate half way up. The tropics near the 7-foot ceiling were reserved for drying socks, two suits of underwear, and Vane’s bunk.

The galley was tossed into the stock-box at present, its space preempted by the magnetic instruments Norris and Vane were working over. McReady’s meteorological instruments, being of a more rugged type, were fastened to the wall. McReady crossed to check the recording anemometer card. It showed an almost straight line across the dial—30 to 35 miles of wind during every hour of the last 20. The thermometer showed greater activity, climbing to a height of -40°.

“Get through with the schedule?” Vane looked up toward Barclay.

“The batteries thawed out enough, but they won’t stand many more shots. I’ll have to use the dynamo next time, and you’ll have to shut down shop, I’m afraid, Vane.” Barclay nodded toward the magnetic instruments. “Dutton said my stuff was just coming in, and his voice was weak in the receiver. Here are the data. I’ll try to turn it into English letters, if you can’t read it, but it’s damned hard to write on that rig.”

“I know.” Vane nodded. “Did it work, though?”

“Well—in a way. I didn’t get frost-nipped much, and I didn’t get burned much, but trying to use a primus stove for a writing table isn’t quite the best way to do things.” Barclay shrugged. “Commander Garry wanted to know if you’d gotten any answers yet, and I replied none that I knew of. Right?”

“Not altogether.” Norris poked a stubby finger at a large scale sketch-map of the area, which included their Secondary Magnetic Station as well as the main Antarctic base camp at the South Magnetic Pole, 78 miles away. He had drawn a small X near the Station. “The data we got from Big Magnet combined with what we got here during the last 24 hours make the magnetite-mountain idea impossible. It seems to be a meteor or something of the sort. Apparently a very considerable mass of extremely dense material, far too small and concentrated to be an iron-oxide mountain.”

“A meteorite?” McReady looked doubtfully at the spot marked on the map. “About a half mile away, eh? But would a meteorite affect your instruments at Big Magnet?”

Norris nodded. “Big Magnet is directly over the South Magnetic Pole of the Earth, therefore the compass needle should point directly downward. There is no horizontal component—that is, a horizontal compass needle would say that any direction is north, turning freely about a vertical axis. To a compass, the Magnetic South Pole is what the true south pole 1,200 miles away is to the geographer; any direction is due north. There is no horizontal pull, the shortest way north is straight down.

“But we found, with our sensitive instruments, that there was a horizontal component, indicating a sort of secondary south magnetic pole, a very weak one, in this direction. It’s only detectable where there is no horizontal interference from the Earth’s magnetic pole.” His finger jabbed at the X again. “And that meteorite, whatever it’s made of, is terrifically magnetic.”

McReady whistled softly. “You think you’ve got it located? Going to try to find it?”

Vane looked up at him with a smile. “If you found the nesting place of the great-grandfather of all storms—would you go after it?”

McReady laughed. “Thanks, boys, but I think you’ve already found that great-granddaddy of all storms for me. The barometer’s falling, and this place has a 30-mile wind as a normal condition. Commander Garry will have to send one of the planes back up country that way to see if there isn’t a funneling mountain chain sending us these breezes.” He glanced at the map. “Do you think you can find that meteorite?”

“Certainly,” Vane said. “If it is only a half mile away, then it can’t be very deep under the surface. We might even be able to reach it physically. I’m just damn fool enough to hope, and I’m going to set out tomorrow with ice axes and shovels.”

“Ye Gods,” Barclay groaned, “more digging? I thought I hated snow shovels, but since I’ve played with these non-magnetic darlings of yours in this blasted ice, my star detestation has become the ice axe.”

Barclay glanced toward the tool chest. The lid was up two inches or so, and the ends of three pointed ice axes showed, looking like teeth in a grinning mouth.

“You can always hope that it’s buried good and deep so we can’t possibly dig it out,” pointed out Norris. “And those beryllium-bronze tools aren’t so bad—the stuff will cut steel.”

“All right maybe for ice axes and butcher knives,” Barclay admitted, “but every blasted wrench and cold chisel we’ve got is made out of it. It hasn’t got the grip that case-hardened steel has. The Stillson wrenches aren’t worth a damn on a hardened steel tractor shaft. What I object to is making me use bronze-age tools on a machine-age tractor. Since the magnetic mass of the tractors make it impossible for you to work near them anyway, you might have let me have steel tools there.”

“Avoid duplication,” said Vane, spreading his hands sorrowfully. “Axiom number One of South Polar research. We had to use carbon dioxide in the Geiger counters for cosmic ray work because the argon bottle leaked and we didn’t have a duplicate. If you really want to lug an extra 150 pounds of steel tools around, that’s your privilege, I suppose. Speaking of duplication and digging—how many thermite bombs have we got left?”

“Three,” said Barclay. “I fell over all three trying to get at the radio set in the tractor. Three 25-pounders.”

“Well, if McReady’s storm holds off, we’re going hunting tomorrow. I think Norris better ride the sledge with the instruments, while we man-haul him. Sad experience convinces me you can’t watch a dip needle and your feet at the same time. This ice-dome may be bald, but it presents some nice cracks to fall into.”

McReady sighed and sat down on the edge of his bunk. “It’s my turn to cook this evening, I believe. If you birds will move that junk, I’ll set up the primus stove and we’ll see what the larder offers. I think I’m going to crack a few eggs. Everybody willing?”

“What, no pemmican? No rancid seal-blubber? We couldn’t stand for that omission.” Vane sprang to remove the magnetic apparatus. “By the way, Mac, do you suppose that they still have eggs, up there in the north, that lie down flat when you open ’em? Eggs that lie down together like the lion and the lamb, with both yolk and white flat?

“If you don’t like eggs that have been frozen, you don’t have to eat ’em. You can have that seal-blubber. And if you don’t like that, remember that the seal didn’t ask to be eaten. I just thought it might be a good idea to stoke up for work tomorrow. Either we dig for your blasted meteorite, or we have to lace down the roof against the wind. We’ll have a little variety tonight, and then tomorrow breakfast can be something different. How about cocoa and oatmeal?”

“Let’s see, didn’t we have that yesterday? It was oatmeal and cocoa this morning, but wasn’t it cocoa and oatmeal yesterday?”

“No, it was oatmeal and cocoa.” McReady assured him. “I fixed it. Barclay, will you start heaving the kitchen over here. Primus stove first—let’s go.”

Barclay started in at the top of the chest, and worked down rapidly. First the stove. Then the food crate.

* * * *

McReady was first up next morning, and his was the joy of starting the copper stove to dispel the frost of the night. The Garry Expedition had tried, with fair success, a new system in Antarctic exploration. Since they were basing at the South Magnetic Pole, Big Magnet base had been, perforce, 350 miles from the nearest point accessible to ships. The entire mass of expedition equipment had been freighted in by the five planes. Even one of the six tractors had been flown in. But the impossibility of freighting 500 tons of fuel so far inland had forced Commander Garry to try to live off the country in this respect; Antarctica was known to have coal reserves greater than those of any equal area on Earth, excepting only the United States. The expedition’s tractors and electric power plant were steam driven, the heating and cooking stoves coal-fired.

The fuel found 20 miles from Big Magnet in the Magnet Range had, however, been a low-grade, high-ash bituminous coal. McReady’s task of starting the little stove was, in consequence, no easy one. Belches of smoke served effectively to force the others from their bunks into the chill temperature of the Secondary Magnetic Station.

“The temperature outside,” reported McReady carefully placing another lump of coal, “has fallen to -58°. The storm has arrived, the abnormal condition of the local weather. I might have known what it would be.”

“I don’t hear anything,” Barclay said.

“It’s a dead calm. Bar, my friend, I fear we dig today, unless the meteorite is happily placed very deep. Let us pray.”

“Damn. A dead calm. Oh, well, the temperature may go down, but that’s more comfortable than wind. Is it still dropping?”

“On its way down. It’ll be -65° by the time we get started.” McReady assured him. “Will you get some ice for the melter?”

* * * *

Two hours later, the thermometer verified McReady’s prediction. From horizon to horizon, the blue ice of the bald plateau stretched out under winking stars, the calmest and clearest air they had seen since reaching this wind-swept dome. The northern horizon was barely washed with rose and crimson and green, the southern horizon black mystery sweeping off to the pole. The auroral lights wavered in shimmering curtains about them, intensified slightly off to the northeast, in the direction of Big Magnet base and the magnetic pole. The brightest stars had dancing crystalline duplicates in the sparkling ice underfoot. Off to the west, the ice contracting under the cold gave a ripping crack, and a succession of spreading, lesser reports as the strain was eased.

“Be hell if one of those relief cracks strikes through the camp,” muttered Barclay. “We’ve weakened the ice cutting into it here, so it might.”

“The seismic sounding showed the ice right here to be 1,200 feet deep,” Vane pointed out. “A 7-foot hole is just a little chip. By the way, the ice movement is toward the northwest, here, and we’re bound in that direction. There is probably a drowned mountain or hill backing the ice up this way; we may hit it.”

“Got everything?” McReady asked.

“Um. Let me get settled, and thank God that your storm was a flat calm.” Vane alone of the party had worn heavy furs. The others would be sweating in stout khaki trousers, woolen shirts, and mackinaws under wind-proof clothes. Vane, riding the man-hauled sledge would have the least pleasant task, that of sitting still and observing the magnetic instruments.

“I said an unusual condition would arrive,” McReady defended himself, “and it did. This is the first calm we’ve seen since we got here. I admit I gave the wrong interpretation, but there must be wind storms here at times. One might even say that this is a storm—a 35-mile-per-hour wind in the opposite direction.”

The men set off. The ice crampons chipped into the ice under their heels and made going not too difficult, but the age-scoured ice, gouged by the sand-like grains of ice borne on howling, unceasing winds, remained a rough and uncertain surface. The man on the sledge had to brace himself continuously at unexpected angles. Two deep crevasses, unbridged in this drift-free territory, forced them to detour for nearly a mile before returning to the course indicated by the dip needle and the spaced inductor-readings Vane made.

Slowly, though, the dip needle reacted to their motion, and the steady point toward the greater power of Earth’s South Magnetic Pole gradually weakening as they approached the unknown magnetic body near at hand. Abruptly, as they entered a region cut and folded with hundreds of crevasses ranging from 6-inch cracks to 10-foot wide gaps falling to unplumbed depths, the needle swung idle. Swung, then in the jar of a hummock of ice, languidly took a new direction.

“Stop,” Vane called excitedly, “She’s swung!”

The hiss of the air turbine, and the soft whine of the inductor coil spinning madly in the magnetic field started again as Vane unlocked the galvanometer needle and opened the valve. Slowly Vane rotated the brushes, while Norris took a sight on several of the brighter stars to the south, faded now in the growing light to the North as the sun crept nearer the horizon. “No effective field to speak of. The Earth’s field and the meteor’s field about cancel here.” Vane closed off the turbine valves, and the hiss of escaping air stopped.

The dip needle rocked with the swaying sledge, twisting in its multiple, delicate gimbals. Now it moved less and less sluggishly as they approached the new center of attraction. The crevassed area forced their way to slant and twist, required the utmost care lest a small crack be the surface warning of a cavern whose walls curved nearly to meeting at the surface, leaving flimsy shelves to snap off under their weight. Roped to each other, 190-pound Barclay lead the way, examining each crack as he passed.

“That ridge damming back the ice must lie near here, Norris.” McReady pointed toward the field of crevasses ahead, and the further field of smooth ice sloping down to a field of familiar antarctic drift snow beyond.

The sledge twisted on, through the last of the crevassed region. The returning sun sweeping above the horizon had begun to stir a slight wind, a wind that would barely turn anemometer cups, but added a danger of sudden frost-bite at that temperature. The crest of the ice-buried hill was passed, and a gradual slope to the field of drift snow, less broken than the region they had passed, lay before them.

“She’s almost vertical now, Norris,” Vane called presently. “A little to the left—whoa! She’s backed up! Norris, that damn meteorite isn’t fifty feet across!”

Barclay took a beryllium-bronze hammer from the sledge, a blowtorch, and some sounding equipment. The ice axe cut a chip from the ice, while the physicists worked over their apparatus. McReady struggled with the blowtorch while Barclay buried the sounder and the receiver under ice chips. The torch roared suddenly, and in its blast the ice chips fused about the sounder and receiver, to freeze solidly the moment the torch was withdrawn. Skilled by long practice, Barclay thawed out the dry cells and slipped them, still faintly warm, into his belt against his body.

He pressed the sounder key, and a sharp, clean-cut whine shot out from the sounder. Instantly a needle jerked across the dial of the apparatus, to halt abruptly a fraction of a division from the stop pin. “Less than fifty feet of ice, and then an unregistered depth of rock.” Barclay reported finally. The blowtorch freed the bits of apparatus. He tried a new station. Still less than fifty feet. Then the depth fell abruptly as they passed some ice-drowned rocky cliff-edge. Back and forth they maneuvered, plotting a profile of the invisible surface beneath the ice.

Vane and Norris were tracing spirals about them, widening and narrowing their range, until at last they found their center of action. Barclay and McReady joined them. A dozen careful plots back and forth across the lines Vane and Norris determined magnetically gave only consistent readings of less than fifty feet—too small for the sonic instrument to measure.

“I hate to mention it—” Vane looked suggestively at the ice axes and snow shovels lashed to the sledge. “That ice axe there has been forcefully reminding me of its presence all the way out here. Let’s give it a beating.”

The sun rose very gradually above the horizon to the north, rising by sliding along an invisible, angling groove somewhere beyond the edge of the frozen continent. The thermometer rose slowly with it, and wind began to creep across the plateau, gaining velocity as the temperature differences increased. The thermometer passed -50°, and the wind passed 15 miles an hour. The four men still chopped and hacked into the cold-brittled ice. A sloping, step-nicked tube grew down into the ice, the solid blue of the stuff began to scintillate with blinding, intense azures, pure rays of sapphire, the chips became huge wealths of discarded emeralds, sapphires and rubies. The sun’s slanting rays were piercing down, heatless, through nearly twenty feet of crystalline ice. Still the magnetic needle pointed straight downward.

Barclay returned to the surface with a tarpaulin of ice-chips to dump, and cursed over the blowtorch. The rising wind nipped at his fingers, the metal was torture to ungloved fingers, and the gasoline blistered his fingers by its swift evaporation, while refusing to ignite. The wind whipped the flames out, and it was minutes before it roared in welcome blue-white heat.

“As long as we’ve got this damned hole, we may as well try to heat it,” Barclay growled as he stumbled down the tube to the others. “And this ice seems clear as glass. Maybe we can see what we’re driving at if we melt a smooth patch.”

The blowtorch flame licked at the chipped wall at the bottom of the pit. The jagged fractures smoothed, and ran. Slowly, as Barclay circulated the torch, the smooth surface widened to a window in the unbelievably clear, hard ice. The vague shapes of rocks moved and wavered as the melting water flowed away from the flame; a blue sea lit by the diffused light of the sun became visible beyond the clearing window.

Norris looked through the window. Only vaguely could the dark, rounded forms of huge rocks be guessed at, great dark masses too far away now for clear vision. The compass needle pointed almost directly downward. “Try a window in the floor, Bar. I think you’ve got a sound idea there.”

The flame washed at the floor, after McReady had chopped it more nearly level with an ice axe, and cut a deeper groove to catch the melted water. The others, crowded out of the narrow tube as Barclay worked below, saw him turn the torch aside suddenly. It roared to itself, a stuttering, fluctuating mumbling almost on the verge of speech. Barclay stared down through the window he had cleared, a black, slick surface in the blue sea of ice.

He straightened slowly and cut off the torch. His head bent far back to look up the steep tube toward the others, he spoke at length. “I’m nuts, so I’m going to chop up this window, and you birds can go on digging, if you like.”

The ice axe McReady had left shivered the slick blackness into refracting, scattering chips, and Barclay walked stolidly up the crude steps cut in the slanting wall of the pit.

“Bar—what the hell’s the matter?” Vane demanded.

“Go ahead and dig. I know damn well I’m screwy, so I’ll let you find out for yourselves. If you find what I think I saw, I’ll help. But not until or unless. It’s about five feet down. Go easy when you get there.” Barclay walked off toward the sledge, and began relashing the load silently.

For a moment the other three looked at each other uneasily. “There’s one good way to find out,” suggested McReady. He slid down the steep slope, using an ice axe to break his fall. Vane joined him, throwing the ice chips he tore loose into a tarpaulin to be taken to the surface. Norris followed Barclay over to the sledge, fruitlessly trying to get some answer to his question.

Abruptly, the two men turned at the explosive shout of McReady in the depth of the pit. There was an immense silence, then a single curse. Then: “Bar—Bar, you damned wall-eyed idiot. Why in ten hells didn’t you say what you saw. Norris—Norris—for God’s sake come here! There’s a plate of polished, machined metal that extends for an indefinite distance.”

“It’s the magnet, Norris!” Vane’s voice rang out hollowly from the pit.

“That,” said Barclay softly, seating himself on the edge of the sledge, “is not what I saw. I guess I’m not nuts, maybe, but maybe I am at that. They haven’t gone down five feet. Tell ’em to keep going.”

Norris left on the run. Vane passed up the ice chips to him, and a second sack before the first was returned, while McReady’s ice axe and snow shovel rapidly enlarged and deepened the pit before Norris was able to get down for an examination. Then—the brittle schith sound of the splitting ice crystals changed to a duller, sodden crack. The activity below became a sudden silence.

“God!” said McReady softly. “Good God!” The schuff of the ice axe started, very gently, very carefully.

Unable to see past the two men, Norris heard Vane’s soft sigh, and over his head caught a glimpse of glittering silvery metal. A smooth, curving metal surface nearly five feet square was bared. The sun had set again, but the rose and lavender, apple greens and melting yellows lingered in the sky. The light that trickled down through twenty feet of ice glimmered on the bared metal, hinting at an immense bulk of machined, rounded metal plates, joined with unhuman skill.

Vane straightened, and backed away. Half visible between McReady’s legs was a head, a half-split head laid open by a careless ice axe. Norris turned up toward the sun-painted patch of sky and called out to Barclay.

“Bar, if what you saw had blue hair like earthworms and three red eyes, it’s here.”

CHAPTER TWO

The autogyro settled to the ice gingerly, in an absolutely vertical descent. The thirty-five-mile wind rushing across the bald ice was a steady, smooth river of super-cold air flowing from the high South Polar Plateau to the sea somewhere to the north. The brilliant orange of the plane was the only color on a landscape, made glaringly blatant under the fierce brilliance of four magnesium torches. The moment it touched, the four members of the Secondary Magnetic Station party started inward with the torches, while Blair jumped from the cabin of the plane with ice-anchors in hand. Behind the wiry little biologist, the stocky figure of Dr. Copper tumbled out with further anchors. The ’gyro rocked slightly back and forth as the pilot gunned the engine uncertainly. The propeller had to maintain a fair thrust to barely hold the plane in place against the unceasing thrust of the wind from the south. The twinkling rotor blades shifted jerkily, then slowed as Macy gradually cut their lift-angle to make the plane stay more solidly on the ground.

The biologist and the medico had the anchors placed by the time McReady and Norris reached them, and the pilot cut back his throttle. Almost instantly the thin, cold blast of air chilled the motor, and it began to splutter. Macy gunned it again, jazzing the throttle to make it catch. His mouth moved behind the plastic windows, but the roar of the engine drowned his words.

“Six sacks of coal—food supplies—two more bunks.” Blair shouted. “He’s going right back. Dr. Copper can stay only two days or so. Commander Garry had to stay behind—too much weight.”

Norris nodded vigorously. Barclay and Vane came up, dousing their unneeded torches. The bitter blast of the plane’s slipstream forced the men to some distance, as Copper explained the plans.

“Garry thinks he will let you men work here, modify the plans for the Geological Party to leave this tractor available. They’ve sent another gang of men to the coal vein so more fuel can be used. Done any more digging?”

Vane shook his head. The booming of the engine made conversation half lip-reading. “Waiting for you. Moved the tractor up, though. Bring the saw?”

“Yes. Upjohn kicked, but gave it up. He’s needed it making the ‘houses’ on the other tractors, so he wants it back when we can let him have it. Macy wants to get going. Says that he can land the Douglass here if you can promise a wind like this all the time.”

McReady grinned sourly. “We’ve had it practically 24 hours of every day we’ve been here. The elevation’s only 1100 feet, and a little chopping will smooth any humps out of this ice. He could land the big Boeing here if he had to. I’ll promise him a 35-mile wind any day, and on special order we can get him a 50-miler.”

“We’ll need more coal,” Barclay put in. “We’ll be running the tractor engine for the dynamo a lot.”

“Couldn’t carry any more this trip. Too much junk. He’ll be back for me in the Lockheed, he said, and bring three tons if you need it. Let’s get that stuff out before his engine conks. Ye gods, its cold.”

McReady said, “You haven’t been here, Doc. It’s -45° tonight. Let’s go.”

* * * *

Ten minutes later, the ’gyro’s vanes began spinning more rapidly. There was no need to clutch in the engine here; the river of wind cranked them to speed. The plane took off from the ice in a vertical climb, the windmill vanes flapping awkwardly, like some immense duck rising from blue water. The tiny lights circled overhead, then vanished at express speed as Macy turned downwind toward Big Magnet.

“I’ll signal the take off.” Barclay started toward the buried station, two bags of coal trailing black dust behind him, black dust the rushing wind scoured off the ice instantly to whip away toward the Antarctic Ocean 400 miles north. Blair and McReady were lashing the little biologist’s instruments onto the sledge, piling bunk sections and sacked food supplies on top.

The Station seemed even more crowded, with everything jammed down to one wall. The magnetic instruments were gone, packed on the tractor and moved to the new location. But the battery-operated trail radio set had replaced them, the dry batteries forming a fringe under Barclay’s bunk, swinging high enough from the floor to be above the “frost line.” The transmitter had been suspended at shoulder height by cords from the ceiling, the key lashed to a horizontal brace of the wall.

Barclay leaned against the bunk upright and began tapping out a call for Big Magnet. Macy and the ’gyro were already in sight over the main base before he got an answer fifteen minutes later. Macy had found a band of 80-mile wind at 4,000 feet.

“Is it time for theories yet?” Dr. Copper asked, as the bunk sections were going into position. “By the way, I hope you birds aren’t sloppy eaters. I see my bunk is going to be the dining table.”

“Bar’s not bad,” McReady grunted. “He laps up everything he drops. But I don’t think it’s theory time. Whatever that thing is, it might be taken for a submarine—the soundings we made, both magnetically and sonically, indicate it’s about fifty to sixty feet in diameter, and the magnetic instruments indicate a tapering length of about 250 feet. It definitely doesn’t have wings. There’s a tremendous concentration of magnetic mass, Vane says, near the center. Engines or something, maybe. It might be a submarine wrecked when this portion of Antarctica was submerged. I don’t believe that. Then it’s a type of flying gadget we never heard of, and it got wrecked somehow. The length of it, incidentally, runs northeast and south-west, almost at right angles to a line drawn from it to the Magnetic Pole.

“Here’s where the meteorology comes in. It’s been glaciated under. Once upon a time, snow fell here, and drift fell, and the Thing was buried. Weight compacted the snow to this blue ice. Then the wind of this bald plateau scoured God knows how much of the snow and ice away. If that thing landed before the snow started compacting, it’s at least half a million years old. If it fell warm, it might have melted its way under the surface for a while and landed where it is at any time. It’s on the sheltered side of the drowned ridge, behind a tongue of high land that runs south for half a mile dividing the glacier, and diverting the ice movement and pressure. That’s the reason for those crevasses we ran into. You know Doc, that thing could have been there a hell of a while.”

“How about the—thing you found?” Blair asked.

“No dope.” Vane stoked his pipe and lit it. “We didn’t mess with it much, Unpleasant animal, I can tell you that. I think we said about all we knew about it. Frozen hard as the ice it’s in. Might have been there a million years—or fifty million. Perfectly preserved, of course, and dead as those mammoths they find in Siberia. It’s kept for some while already, so we figured it’d keep until you got here. You can play with it. We didn’t like it.”

“You described the head rather vaguely,” the biologist objected. “Is it anthropomorphous?”

“Man-like? The rest of it’s under the ice and rather blurred. What we could see suggested that we let you look at it. We saw enough. If it had a disposition such as the face indicated, I’m not interested, even if it’s been dead since Antarctica froze.”

“Disposition—the face—?” Blair looked curiously at the members of the Station party.

Barclay spat into the little stove and heaved in a few lumps of coal. “You can look at it tomorrow. You’d rather.”

“Eh?”

“He means you’ll sleep better,” Vane said. “There aren’t any scientific terms for facial expression, so far as I know.” He looked into the fire for a moment silently. “Anyway, the face isn’t human, so maybe we can’t interpret it. He might actually be registering resignation in the only way his kind of face could. But I don’t think so. Certainly if he was, he started out with a terrible handicap; that face wasn’t designed to register any peaceable emotion. From human experience—which one glance at the face would assure you has nothing to do with the problem whatever—it isn’t remotely human—I’d say the thing was trapped, and it was mad. Not crazy, though any human to have as much distilled essence of hatred in his eyes would have to be crazy. I think it was just angry.

“Vaguely through the ice, I got a suggestion that the flying submarine-thing was jammed up against a rock wall, the nose crumpled in. The small section we exposed was strained and bent; I think the nose was ruined. From the build and the lines, I’d say that whatever it had been, it was fast—damn fast. Make the trip from the magnetic pole to where it was in maybe 30 seconds, say, or—perhaps—a trip from Mars or Venus in three or four days. Nothing Earth ever spawned had the inexpressibly cruel hatred those three red eyes displayed, I know that.

“But the center section of the ship had an impossible magnetic mass, the section where driving engines ought to be. All that attraction we detected 80 miles away at Big Magnet originated in a section about 20 by 20 feet. That’s fact. This isn’t even theory, it’s just guess. I think that ship came down to Earth too near the magnetic pole, and the driving mechanism—however it may have worked—soaked up too much of Earth’s magnetic field and blew out. Earth’s field isn’t particularly intense, but it’s big. A hundred million ampere current circulating the equator might cause it. If that ship’s engines tangled with the planet’s field, something would blow. It wouldn’t be the Earth’s field.

“So that thing came out of its ship, trapped. It must belong to an older race than man. It looked out over an Antarctica already frozen, perhaps even colder then than now. Four hundred miles of it in every direction, four hundred miles of impassable glaciation without a living thing bigger than a microbe or an alga between it and an unattainable sea. And oh, God the hatred in that three-eyed face, with its blue earthworm hair.

“Damn it man, let’s turn in. Tomorrow’s soon enough to, think about that Thing out of the Pit.”

Vane grunted, knocked out his dead pipe against the belly of the copper stove, and started fixing up his bunk. The wind mouthed throaty gurgles down the stove pipe, curses and maledictions whose seeming syllables made one listen, struggling to understand the nearly-intelligible vindictiveness. Syllables, perhaps, that the Thing out in the frozen pit had taught it once, ages ago.

* * * *

The wind was belching the same vague syllables when they rose in the morning. Norris, taking his turn at starting the sullen stove, cursed and kicked it back to life.

When they started out, the wind slashed at them with an edge keened by a -45° temperature. The lashings of the sledge grunting and thrumming under its pressure. The unremitting force seemed to be pushing them away, trying to turn them back from the flag-marked trail. Many of the tough, orange cloth flags had been whipped to three-inch tattered remnants in the 30 hours since they had been placed, and some of them had been torn away completely.

But the trail was marked now. They no longer had to feel an uncertain way through the treacherous crevasses, and as they passed the region cracked and torn by pressure from the ice-river to the south, the orange blot of the tractor loomed up against the colored wash of the northern horizon. Close beyond it, the wind-leveled heaps of ice chips the Magnetic Station party had cut from around the buried ship marked the entrance to the excavation.

They parked and dismounted. McReady lead the way into the tunnel, substituting a furiously incandescent magnesium-metal torch for the dimmer pressure lamps used on the trail. The magnesium strips burned with an incredible white light in the blue crystalline tube, the ice slanting down about them in rough, blazing gems of crystalline refraction. The fierce thrust of the radiance seeped through the ice for a distance of more than a hundred feet. From the surface, the men below became vast bat-like shadows writhing beneath the ice, the whole ice field glowing with an inner incandescence for 100 feet around save for the immense black shadow of the strange ship, frozen in this glacier unknown ages before.

When they reached the Thing, Blair and Copper looked thoughtfully at the face staring up from the scintillant floor of the tube. Ice chips blown in by the wind had dusted it with a powder that glittered like diamond-dust under the brilliance of the magnesium flare.

Blair drew a bulky little camera out from under his windproof clothes and took half a dozen pictures. The face seemed disembodied, a mad sculptor’s interpretation of incarnate evil tossed carelessly on a jeweled floor. Copper scraped carefully with an ice axe and passed his ungloved hand over the smoothed surface. His body heat fused the surface to a black, slick, wavy lens giving view to the depths below.

McReady grinned as the doctor hastily scuffed the surface with the ice crampons on his heel. “That’s our pretty beastie, Doc. We have got to dig the damned thing out.”

“Ugh. Damned is right. That thing belongs in this sunken pit in the middle of a frozen hell. It isn’t quite so bad, here. That glittering ice under the rather unreal light of that flare—” Copper shook himself. “Hell of a thing for a medical man and a scientist to say, but I don’t want to dig it out.”

Blair continued to stare down at the face. The little biologist spoke suddenly above the organ thrum of the wind over the pit’s mouth. “You split the head accidentally, when you were digging down to it?”