David Pilling

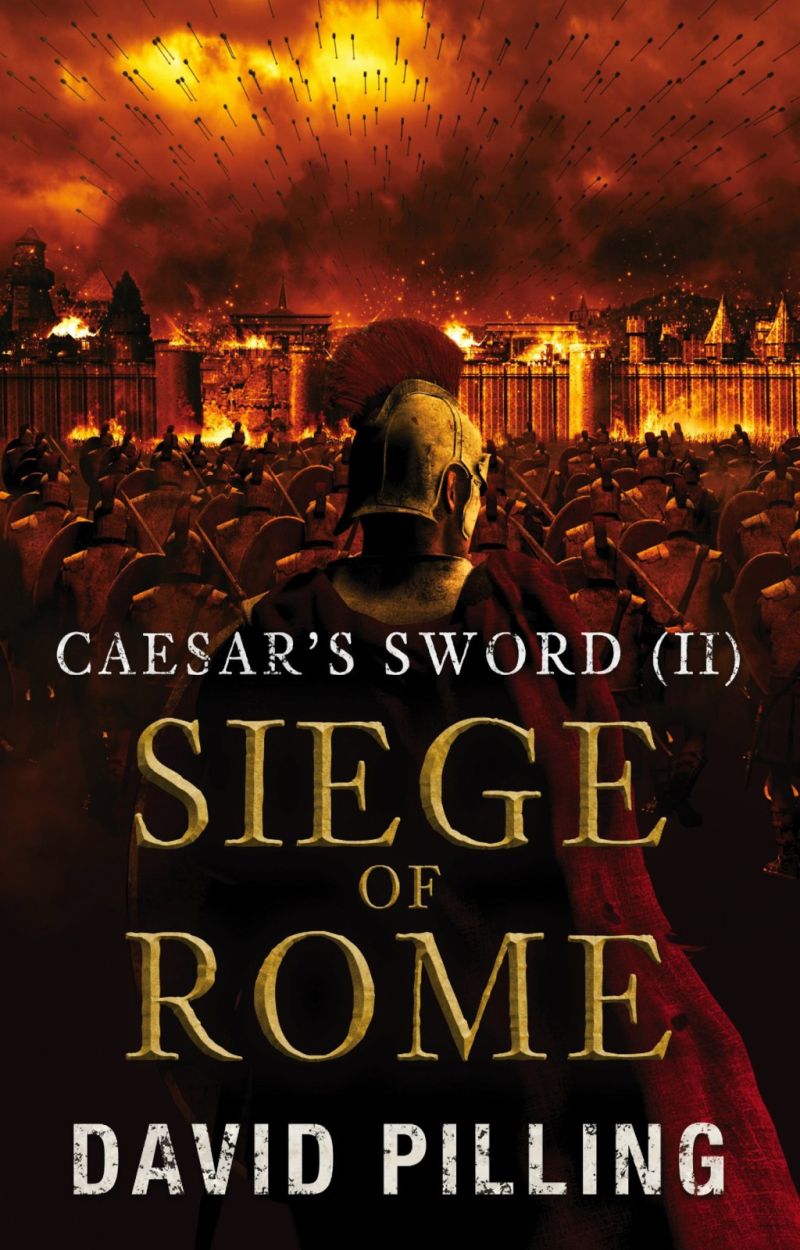

Siege of Rome

Prologue

Abbaye de Rhuys, Brittany, 570 AD

The glory of Britain is dead. News has reached our monastery of a battle fought in the west of the island, not far from the scene of Arthur’s great victory at Mount Badon.

On this occasion it has pleased God to allow the Saxons the victory. No less than three British kings were left dead on the field, their blood mingled with that of five thousand British warriors.

The Saxons, they say, attacked at dawn, while the Britons were still wallowing in their beds. In their arrogance and complacency, our kings did not think to post any guards.

Now the whole of western Britain lies open to the invaders. Our crops shall fill pagan bellies. Fire and sword shall consume our undefended towns. Woe to the people! God have mercy on them, who shall now be conquered and enslaved.

My fires are not all burned out. A flicker of life yet courses through these withered veins, and the incompetence of those charged with guarding the land of my birth fills me with as much rage as sorrow.

It is the custom of old men to decry the state of the world as it is now, and to recall with misty-eyed fondness the glories of their youth. I am reluctant to follow the same path, but the fact remains that Britain is degenerate, and her warriors a pale shadow of their forefathers. Would Arthur, my mighty grandsire, have been caught with his breeches down by a pack of yelping Saxons? Would any of his captains, proud Cei or matchless Bedwyr?

Perhaps I pay too much heed to legend. I never knew my grandsire or any of his men. Their bones lie mouldering in the soil of a dozen battlefields. No more shall Arthur’s legion ride forth from Caerleon under the dragon banner, to strike terror and a kind of awed respect into Britain’s foes.

Nor have I set eyes on Britain since my early childhood, save a glimpse of its green shores across the sea on clear days. My fate was to serve in distant lands under a foreign chief. His name was Flavius Belisarius. The Pillar of the East, as the Romans called him, a man every bit as great as Arthur.

It is the fate of great men to be betrayed. Arthur was betrayed, and so was Belisarius. How I have wept and prayed for their souls. Foolish, helpless, driveling old man that I am, eking out my declining years in this cramped little cell. Of all the afflictions Gods sends to test His creation, old age is the worst.

I can dimly recall a better time. In my mind’s eye I see the city of Rome, restored to something like her former grandeur. The Eternal City, ancient capital of the greatest empire the world has ever known.

And yet she is threatened. Her walls encompassed by a hundred and fifty thousand baying Goths, while scarcely a tenth that number of Romans hurl defiance at them from the ramparts.

I see Belisarius, our golden general, snatching a bow from one of his archers and putting an arrow through the gullet of a Gothic chief.

“Courage, Romans!” he cried above the approving roars of his men, “have no fear of these barbarians. Maintain your trust in God, cast your javelins and spears down on their heads, and you shall see them run.”

The defence of Rome was his greatest exploit. Who else could have held her against overwhelming numbers of Goths, while the cowardly citizens threatened to stab him in the back at any moment, and his own troops whined and begged to go home?

Who else could have broken my heart so completely? Even now, after the passage of thirty years, the wound has not healed.

I see the general on his white-faced bay, racing across the plain by the banks of the Tiber at the head of his guards. Six times his number of Gothic cavalry stand between us and the gates of Rome.

“That is Belisarius! Kill the bay!”

The cry erupts from pagan throats. They charge. The sky darkens with steel-tipped rain. Spears, arrows and javelins hammer against my shield. We close around the general. He must be protected at all costs. Without him, our army is a rag-bag of mercenaries and conscripts. With him, we are the Roman legions reborn.

My hand closes around the hilt of Caledfwlch: the sword that Arthur held aloft at Mount Badon and buried in Medraut’s guts at Camlann. Julius Caesar’s sword, also known as The Red Death, forged by the gods on Mount Olympus.

The sword flames into life. The triumphant war-shouts of the enemy turn to fear and dismay. We are among them. Their guttural voices ring in my ears. Their hot blood whets my grandsire’s blade.

Better times. I shall take a little wine, and then take up my pen again to write of Belisarius’ greatest victory.

My greatest defeat.

1.

It took me three weeks to recover from the fight in the Hippodrome. I had killed Leo, the traitor and ex-charioteer, but he left me with a broken arm and a fractured jaw.

Belisarius had his guards carry from the arena. The crowd was still chanting my name as they laid me on a stretcher. Delirious with pain, I flickered in and out of consciousness, barely aware of my surroundings. The taste of victory was in my mouth, along with the salt tang of blood.

They carried me through the empty streets to a sanatorium not far from Belisarius’ house. He could not shelter me in his own house, for that would have been perceived as a deliberate insult to the Empress Theodora. It was public knowledge that she wanted me dead, and had sponsored Leo as her champion. His death at my hands was a serious defeat for her, and one she would thirst to avenge.

Belisarius appreciated the danger I was in. He posted six of his men to watch over me while I recovered. They were Huns, brawny mercenaries from Scythia, and he put his trust in them over our own people. Theodora’s influence spread like an ever-expanding net over the city. There were few among the citizens she could not bribe, threaten or manipulate into doing her will.

Towards the end of my recuperation, the general visited me in person. He came at night, hooded and cloaked, and alone.

I woke from an uneasy sleep to find his narrow features staring down at me. Hollow-cheeked and balding, he still looked more like a priest than a soldier, though his wiry, meatless frame possessed enormous strength and skill at arms. The flame of the tallow candle next my bed reflected in the pits of his large, expressive eyes.

“General,” I croaked, endeavoring to sit up, but he placed his hand against my chest and gently pressed me back against the pillows.

“Conserve your strength,” he said, “you will need it soon enough. Are you mending? How is your arm?”

I cautiously tried to bend my right arm, which until the previous morning had been held straight in a splint. Leo had broken my elbow during the fight in the arena.

The priest at the sanatorium kept the pain at bay by dosing me with alcohol and poppy juice. His potent medicine kept me in a semi-delirious state for days on end, during which time I suffered terrifying hallucinations. Gradually he lessened the dose, and the devils faded from view.

Relief washed over me as I found that I could bend the arm without too much pain, save a dull ache that throbbed up and down the limb, and flex my fingers.

Belisarius smiled. “Good,” he said, “the arm will be weak for a while, but nothing is broken beyond repair. Open your mouth.”

I obeyed without question, wincing as pain stabbed through my jaw. Leo, may his soul baste in fire in the lowest circle of Hell, had dislocated it with his knee.

Belisarius tilted my face towards the light. “You have lost four teeth,” he said, “I saw them on sale outside the gates of the Hippodrome, the day after your triumph. You are something of a hero among the people, Britannicus Minor.”

I winced again. Britannicus Minor was Theodora’s mocking pet name for me, bestowed when I was a youth training to be a charioteer in the Hippodrome, and she a common dancer and prostitute. I hated it, but the name became popular when I started racing in the arena.

My mind was still clouded with the lingering effect of opium, and it hurt to form words. “A dead hero, sir,” I mumbled, “if I stay in the city.”

Belisarius’ long face was naturally suited to looking grave. He nodded somberly and lowered his bony rump onto the stool beside my bed.

“My guards have already slain two of Theodora’s assassins,” he said, “they grow bolder every day. One of them posed as a seller of rare herbs and medicines. He might have passed through if my men hadn’t insisted on searching his basket and found the knife. Sooner or later they will abandon stratagems and resort to force. The Empress has only stayed her hand this long for fear of public disgrace. Her husband disapproves of her actions, and has asked her to abandon this ridiculous feud against you.”

It seemed incredible that I, a mere ex-charioteer and not very distinguished soldier, should have incurred the wrath of the most powerful woman on earth. But then I knew Theodora of old. For all her outward majesty, she was a vengeful, petty-minded soul, and not one to forgive a slight.

She was also forceful and possessed of a mighty strength of will, far more so than her affable, pleasure-loving husband. Justinian might upbraid her in public, but in private she would work on him until he either went mad or yielded to her desires.

“Fortunately, an easy answer presents itself,” Belisarius went on, “our victory in North Africa has given the Emperor a taste for conquest. Italy is next.”

I could scarcely believe my ears. The African campaign had been a desperate gamble, and might easily have ended in the total destruction of the Roman army.

Thanks to the favour of God, and the skill of Belisarius, a most unlikely triumph had been achieved. The barbarian Vandals were destroyed in two great battles, their mad king taken prisoner, and the old Roman province returned to imperial rule.

My harrowing experiences on that campaign are burned into my memory. I had fought at Ad Decimum, witnessed the slaughter of the Vandal nation at Tricamarum, and shivered my way through months of siege on Mount Papua. Somehow I survived the ordeal with a reasonably whole skin, though I used up most of my life’s supply of good fortune in doing so.

“Madness,” I croaked, reaching for the jug of watered wine, “Italy was lost a hundred years ago, and cannot be regained. Caesar should be content with what he has.”

Belisarius frowned in disapproval. I noticed the deep lines at the corners of his eyes, and the prominent tendons in his slender neck. We were of an age, both in our middle thirties, but he looked twenty years older.

“It is not for us to question the will of the Emperor,” he said severely, “only to do his bidding. This new campaign has come at a good time for you. I shall commission you as an officer in my guards, and take you to Italy with me.”

I gaped at him, wondering if the damned priest had drugged my wine.

“It is your only chance,” he went on, “my guards cannot protect you forever. It is only by the grace of God that you have evaded Theodora’s assassins for so long. You must come with me on this campaign, or die.”

Belisarius was risking much on my behalf. I was aware that little love existed between him and Theodora, though his wife, Antonina, enjoyed the Empress’s confidence.

Antonina was another who had tried to ensnare me. Belisarius was entirely in her power. To go against her, as well as braving the wrath of Theodora, could only mean he valued me far more than I deserved.

I was in no position to refuse, even if the invasion of Italy was a suicidal venture. The ancient Roman homeland had been in the hands of barbarian Goths and Ostrogoths for over a century, ever since Alaric swept through the country and put Rome herself to the sack. The Gothic peoples were far more numerous and powerful than the Vandals, and their fighting strength could not be exhausted in a couple of pitched battles.

An image passed through my fevered mind of Justinian plucking men from a sack and laughing insanely as he threw them into the maw of a ravenous lion.

Belisarius read the doubts on my face. “I know,” he said, “it sounds like death. But the Emperor is no fool. You must trust in his judgment, and mine.”

I struggled up onto my good elbow. “I have no choice,” I replied, and drained the last of the wine.

The general patted my knee. His wintry face cracked into a grin.

“None,” he agreed.

2.

While I lay in a drug-induced fog in the sanatorium, the Gothic rulers of Italy were doing their best to slaughter each other and provide Justinian with a plausible reason to declare war.

The Goths may have been barbarians, yet another strain of the Germanic peoples that overwhelmed the Western Empire, but had quickly acquired civilized Roman habits. In terms of ruthless infighting and dirty politics, Rome had little to teach them.

Let me try and summarise the rat’s nest of Gothic politics as best I may.

At this time their queen, Amalasontha, was locked in a vicious power-struggle with Theodatus, nephew of the great Gothic king, Theoderic.

Amalasontha was as proud, cruel and ambitious as any Roman Empress. Her son had died young, debauched to death after a reign of just eight years. Determined to keep her grip on power, but unable to rule alone – the Goths had a horror of being ruled by women – she proposed that she and Theodatus be crowned as joint sovereigns of Italy.

This Theodatus was an old man, renowned, like the Emperor Claudius, for his love of learning and not much else. Amalasontha flattered herself that she had made a cunning choice. Once he was crowned, the old fool could be safely ignored, and she would be the ruler of Italy in fact if not in name.

Alas, she miscalculated. The old fool was not so foolish as all that. Having submitted to her every condition and sworn every oath she demanded of him, Theodatus suddenly pounced and had Amalasontha’s servants massacred. The queen herself was arrested and banished to a distant island. There, in the spring of the year 535, she was strangled in her bath by one of her colleague’s assassins.

The murder of Amalasontha gave Justinian the perfect excuse to invade. Donning a mask of outrage and indignation, he declared Theodatus a tyrant without legitimate authority, and that Italy must be liberated from his illegal rule.

No further pretext for war was needed. The citizens of Constantinople, their pride and patriotism inflated beyond measure by the easy conquest of Africa, were eager for another taste of military glory.

How I despised them. The fickleness, the cowardice, the sheer arrant stupidity of the Roman mob was the bane of the Empire. They had almost destroyed the city during the Nika riots, and even the bloody vengeance inflicted by Belisarius’ veterans had failed to knock some sense into them. They would cheer a man one day and tear him in pieces the next. Now, skillfully manipulated by the Emperor’s propaganda, they willingly scraped together the money to help fund another war.

Not that Justinian was short of money. The booty from the North African campaign had filled his coffers to overflowing. Some of the treasure went towards the completion of his pet project, the construction of the gigantic domed cathedral in the heart of Constantinople. The rest was poured into the effort of re-fitting the fleet and raising two new armies.

When I was fit to walk, my guards hurried me out of the sanatorium under cover of darkness, to Belisarius’ house. I needed a stick to remain upright, and laboured along the cobbled street like an old man, panting for breath. The Huns grumbled and cursed me in their savage tongue, and in the end two of them seized my arms and half-carried me down the alleyway beside the outer wall of Belisarius’ dwelling.

A slave admitted us via the postern gate, and led us across silent, torch-lit gardens towards an arched doorway. Lights blazed in the windows of the ground floor. The door opened onto the narrow vestibule, and beyond that lay the atrium, a large, open central court with a circular pool in the middle.

We followed the gravel path around the pool, towards the double doors at the northern end. These were guarded by two of Belisarius’ Veterans, hard-looking men in scale armour, armed with round shields and long spears. They glanced at us suspiciously, but did nothing as the slave pushed open the doors and beckoned us through.

Inside was a large, rectangular chamber with a high roof and a beautifully inlaid mosaic floor. It was a warm night in early spring, so there was no fire laid in the great stone hearth. Three arched and colonnaded doorways led off to other parts of the house, but all my attention was fixed on the three men seated on couches in the middle of the room.

One of the men was Belisarius. As ever, he looked uncomfortable out of military uniform, and his loose robes and fringed mantle hung awkwardly from his tall, bony frame.

His companion to his left was Mundus, the hulking German mercenary and magister militum of all the Roman forces in Illyria and along the Danubian frontier. I had last seen him during the Nika riots, when he led four hundred Huns to slaughter ten thousand Roman citizens. It was impossible to imagine the brute in civilian dress, and despite the heat he was decked out in his usual furs and leathers.

The presence of these two powerful men was intimidating enough, but the third surprised and frightened me.

“Good evening, Coel,” said Narses, his ugly face stretched into a smile, “you are fully recovered, I hope. Hardy barbarian stock, eh?”

He was not a welcome or pleasant sight. The last time I was summoned into the presence of Narses and Belisarius, they had coerced me into accompanying the Roman expedition to North Africa, so I could help steal Caledfwlch from Gelimer, the mad King of the Vandals.

After my return to Constantinople, Narses had rescued me from being boiled alive by Theodora’s assassins. I should have felt grateful to him for that, but he was a skilled and subtle politico, and not the sort to do anything except for his own profit. By saving me he offended and humiliated the Empress, and thus reduced her influence.

He was dwarfish little monstrosity, hardly bigger than a child, limping his way through life on a pair of twisted legs. God had seen fit to bring Narses only half-formed into the world. His physical afflictions were offset by an agile brain and burning ambition, and he had risen high in the world through sheer force of will and intellect. Anyone who judged the dwarf on his feeble appearance did so at their peril.

“My lords,” I said, with a stilted bow.

The three men had been sitting in silence when we entered, and the air fairly crackled with the tension between them. Belisarius and Mundus were allies and friends, of a sort, but both distrusted Narses. For good reason: the eunuch once cheerfully informed me that anyone who trusted him was a fool, and deserved an early grave.

For all his ugliness, Narses had acquired a certain degree of practiced charm. He rose, or rather dropped, from his seat, and patted the cushion next to his, inviting me to sit.

“Dismissed,” growled Mundus, waving away the Huns. They stamped their feet, turned smartly and marched outside. The slave closed the doors behind them and melted into the shadows.

“Wine for the champion of the arena,” said Narses, waddling over to the low table beside his couch, “wine for the latest hero of Rome.”

Embarrassed, I limped over to the couch and sat, while Narses poured out a rich, red flow from an elegantly fluted silver jug. He handed me the cup and regarded me with something like affection.

“You did splendidly in the arena,” he said, “Theodora’s face was sheer artistry for days afterwards. I have seldom seen her so enraged.”

He sighed happily. “Bliss to behold, I assure you, though I doubt her servants would agree. Their lives have been hell, ever since you plunged your magic sword into Leo’s heart.”

In truth Leo had fallen onto the blade, but now was not the time to quibble. “I am sorry for that,” I replied cautiously, “I never meant to cause any suffering. I have never done anything save follow my conscience.”

Belisarius had been watching me closely. “No man who listens to his conscience can thrive for long in this city,” he said, “it is a pit of snakes. The sooner we are gone, the better.”

Narses smiled indulgently. “Our famous general is too good for politics,” he said, winking at me, “in his world, honest men with swords defend the frontiers of the Empire, while corrupt eunuchs and former prostitutes do their best to undermine the state from within. Where is your wife tonight, Flavius?”

Belisarius’ jaw tightened. He clearly despised Narses, but for some unfathomable reason had invited the eunuch to his house.

“You know very well,” he replied, with forced patience, “Antonina was summoned to the palace tonight.”

“As she is most nights. Antonina and Theodora hatch plots together in the Empress’s private quarters, while we do the same here. Does the Emperor plot, I wonder? And if so, with whom?”

Mundus shifted impatiently. “I came here to talk of the war,” he grunted, “not to chop words and exchange clever insults. I see no reason why we could not have met in open council during the day, instead of creeping about like a pack of thieves in the dark.”

“He is the reason,” said Narses, pointing at me, “and that pig-sticker he carries.”

I touched the hilt of Caledfwlch, which I had strapped on before leaving the sanatorium. Having gone to such lengths to retrieve my grandsire’s sword, I never let it out of my sight.

“Show us the sword, Coel,” ordered Belisarius. He spoke with the voice of stern authority, and almost without thinking I drew Caledfwlch from its sheath.

Mundus lent forward and squinted at the blade as I held it up to the light. “I see an old-fashioned gladius,” he said, “with two golden eagles stamped in the hilt.”

“Caesar’s sword,” Narses explained, “wielded by old Julius himself, and said to have been forged by Vulcan himself in the depths of Mount Olympus. Lost in the mists of Albion for centuries, until it fell into the hands of Coel’s ancestor. Some grubby warlord or other.”

He hesitated, snapping his fingers and pretending that he had forgotten my grandsire’s name. The eunuch loved to play-act and provoke others. Once, I might have fallen for the bait, but was too canny to snap at it now.

“Arthur,” I said calmly, taking a long swallow of the excellent wine, “his name was Arthur.”

“Just so,” said Narses, smiling sweetly at me, “not just any sword, but a symbol and an icon of rare power. Gelimer would have used it to unite the barbarian nations of the world under his banner and destroy the Empire. It must never fall into the wrong hands.”

He held out his right hand, palm upwards. “Give it to me.”

I slammed Caledfwlch back into its sheath. “Never. That is one order I cannot obey. I will die first.”

“Coel speaks the truth,” said Belisarius, “I tried to persuade him to give it up in Carthage. He refused. The sword is part of him.”

Narses responded to defeats by pretending they hadn’t happened. “I merely tested you, Coel,” he said, lowering his hand, “you are every bit as brave and honest as I feared. But you must not stay in Constantinople. Your enemies multiply.”

He snapped his fingers, and a slave emerged from a shadowy corner, carrying a dark blue woolen cloak scarce big enough to fit a child. He draped it over Narses’ lumpen shoulders.

“I take my leave,” said the eunuch, “thank you for your hospitality, Flavius. An excellent supper. I must return the favour sometime.”

“I look forward to it,” Belisarius replied without a hint of sincerity. He and Mundus rose and bowed respectfully as Narses limped out of the room, followed by his slave.

When the doors had closed, Belisarius subsided gratefully onto his couch and stretched out his long legs. All the strain and tension in the air dissolved.

“Thank God for that,” he groaned, passing a hand over his face, “if the little swine had stayed much longer, I might have thrown him out of the window.”

“Why did he come, anyway?” demanded Mundus, “he talked of nothing but trivialities over supper. Every time I mentioned Italy, he changed the subject.”

Belisarius nodded at me. “Narses used our tame Briton to humiliate Theodora, but not had seen him since he was carried from the arena. I made sure of that. He wanted to know if Coel was still alive and whole, and if he could still be used. Now he knows.”

Mundus’s little eyes raked over me. “Your enemies multiply, Briton,” he said, “Narses referred to himself. You should have given him the sword.”

“It is mine, sir,” I said defensively, “all I have in the world. Without Caledfwlch I am nothing.”

“Narses will take it from you, if he can,” said Belisarius, “I know that scheming little imp. He craves power, spends every waking hour thinking of ways to obtain it. With Caesar’s sword in his hand, there would be no limit to his ambition. Can you imagine him perched on the throne?”

For the first time in weeks I laughed. The effort hurt my jaw, but I was glad of something to lift the clouds gathering over my head.

Belisarius and Mundus spent the next hour discussing the war. I listened avidly.

Justinian had hatched a plan whereby the Romans would attack Italy on two fronts. Mundus would lead the army west and invade Dalmatia, which was held by the Goths, hoping to leech the strength of the enemy by forcing them to defend their eastern province. Meanwhile Belisarius and the Roman fleet would sail south-west, officially to reinforce the Roman garrisons in Africa, but in fact to seize the island of Sicily.

“Sicily will be our stepping-stone to the Italian mainland,” said Belisarius, “our forces shall be likened unto a spear, thrust into her soft underbelly.”

He grinned at my expression. “Well, that is how the Emperor put it. He is something of a poet, and can turn a decent phrase on occasion.”

“What do you make of our plan?” he asked, again watching me closely. I seemed to fascinate these Romans, who regarded me as a relic from some distant world. Their forefathers had lost control of Britain generations ago, and I sometimes wondered if my presence served as a reminder – not always a welcome one – of the diminished Empire’s glorious past.

I pondered before answering. By now I was well into my third cup of wine, but even the heady glow of alcohol failed to fill me with optimism.

“If you can conquer North Africa with a mere fifteen thousand men, sir,” I said carefully, “then you can certainly repeat the feat elsewhere.”

“A shame, then,” said Belisarius, “that I won’t have fifteen thousand men. The Emperor has given me no more than twelve thousand for the task. Four thousand foederati troops, three thousand Isaurians, some Hunnish and Moorish cavalry, and my bucelarii.”

My spirits sank. How many warriors could the King of the Goths muster – forty, fifty thousand? And he could call on the support of his kin in Frankia, Hispania and Germania. If I was of a paranoid disposition, I might have suspected the Emperor of deliberately sending Belisarius to his death.

Yet my only chance of survival was to accompany this suicide mission. With the likes of Narses and Theodora for enemies, my life in Constantinople was not worth a straw.

“Twelve thousand men,” I said, “and one Briton.”

3.

It took months to re-assemble the imperial fleet, and muster armies for the invasion of Dalmatia and Sicily. Spring passed into summer, and all that time I was kept under guard at Belisarius’ house. He had taken a great risk in moving me from the sanatorium, and only done so because I was no longer safe there.

“Not even Theodora’s assassins,” he assured me, “would think of trying to force entry into my house. Not, at least, while I stand high in the favour of the Emperor.”

That favour depended on continued military success. Justinian was a fickle creature, and susceptible to the whispered asides of his courtiers. He was already envious of his general’s exploits in Syria and Africa, and for a time entertained suspicions that Belisarius meant to sever ties with the Empire and declare himself King of an independent African province. Only Belisarius’ speed in returning to Constantinople and protesting his innocence had cleared him of the taint of treason.

For now, with the laurels of recent victories still fresh on his brow, Belisarius was all but untouchable. Even so, he was not fool enough to presume on his current popularity, and made efforts to deter Theodora’s agents. The six Huns who protected me during my convalescence remained at their posts at the sanatorium, guarding an empty room. Meanwhile I was ordered to remain indoors at all times in his house.

This suited me for the time, for I was still weak from my injuries. Belisarius treated me well, and I enjoyed the best of rations from his kitchen. He employed a master-at-arms to spar with me, until my confidence returned and my right arm had regained its strength.

The general himself was often absent, either at the palace or overseeing preparations for war. As before the African campaign, he was drilling his troops on the plains outside the city walls, while the fleet that carried us home was being re-fitted in the harbour of the Golden Horn.

A similar number of ships were needed to take the army to Sicily, transports and dromons for the most part, along with a few galleys. I pictured the feverish bustle of activity in the harbour, hundreds of hired Egyptian and Syrian sailors and engineers toiling in the summer sun, and groaned at the prospect of another sea-voyage. I was a wretched sailor, a martyr to sea-sickness, and had barely survived the journey to Africa.

The long days of rest and inactivity did nothing to ease my mind. Fears gnawed at me in the evenings, when shadows crept slowly through the gaps of the shuttered windows and oiled into my bedchamber. I was acutely aware that only the friendship of Belisarius stood between me and destruction. He was an honourable man, but had his weaknesses, chiefly his slavish adoration of Antonina.

Antonina had tried to seduce me in Carthage, as part of a foul plot to disgrace me in the eyes of her husband. I resisted her, but had lived in terror since that she might feed some twisted version of the incident to Belisarius, claiming that I had tried to force myself on her. So far that particular axe had not fallen, but remained suspended over my neck.

I sat and sweated in the growing darkness. Caledfwlch was my only comfort. I often hugged the blade to my chest, as though willing its hard-forged steel into my quaking soul. Sometimes I thought I could hear the screams of all its victims down the centuries, and pictured the hell of Mount Badon, where my grandsire personally laid low hundreds of Saxons in a single charge.

My ordeal ended in the dying days of summer. Belisarius came to his house one evening, exhausted from his labours, and announced that the expedition was ready to sail.

“Mundus has departed for Dalmatia,” he said over supper, “along with his son Maurice and ten thousand men. Their object is the Gothic capital, Salona.”

He swallowed some wine and dabbed his lips with a cloth. “God grant that Theodatus is as stupid as he seems,” he added, “and sends the largest portion of his forces to relieve Salona. Then Italy will be ripe for the taking.”

Our best hope of victory lay in the folly of Theodatus, whose wisdom did not extend beyond his academic studies. His murder of Amalasontha was the act of a savage and a political child, for it gave Rome the perfect excuse to try and retake her homeland.

The odds were still stacked against us. Despite his outward confidence, Belisarius was well aware of that. Already old before his time, he seemed to age before my eyes, and I started to fear for his health. If he broke down or even – God forbid! – died, there was no-one to protect me.

By the beginning of autumn, all was ready. My gentle confinement finally came to an end, and I was smuggled out of Belisarius’ house one moonless night with the same Hunnish escort that had brought me there. The seven of us, muffled up in dark hoods and cloaks, hurried down to the docks, where a boat was waiting to row me out to Belisarius’ flagship.

If there were spies watching us from the shadows, none tried to impede our progress. The Huns were armed with swords and braces of knives under their cloaks, and I had Caledfwlch, so it would have gone hard for any that tried.

The harbour was relatively quiet, with just a few groups of weary Egyptian sailors stockpiling bales of fodder and other supplies ready to be carried out to the fleet. They paid no heed to us, or the troop of soldiers with torches waiting for us at a jetty.

A tall, bareheaded man stood among the mailed and helmed soldiers. We had never spoken, but I recognized him instantly as he stepped forward to greet me.

His name is famous now, but at this time Procopius of Caesarea was still a young man, and relatively unknown. A Jewish scholar and historian, he had acted as Belisarius’ legal advisor, secretary and general confidante on the African campaign. He was no soldier, but did not lack for courage, and had undertaken several dangerous missions on the general’s behalf.

In person he was of medium height, and always put me in mind of a starving bird of prey. His body was lean, with long arms and legs, and his oversized head was stuck on the end of a scrawny neck. Prominent cheekbones, slightly protruding eyes, thin lips and a long, hooked nose completed the effect.

“Hurry, he whispered, casting anxious glances over my shoulder, “before the wolves that tracked you here find the courage to strike.”

“I saw no-one,” I said as the Huns bundled me down the ladder into the boat. He sniffed and folded his arms tight against his skinny chest.

“Of course you didn’t,” he muttered, his big eyes narrowing to slits as he peered into the darkness, “the Empress employs professionals. You wouldn’t know they were near until you felt steel in your back.”

The waters were calm, but the boat rocked alarmingly when my foot slipped on the lowest rung. I dropped into it like a stone and incurred the displeasure of the oarsman, who cursed me for a handless idiot.

“Quiet, you fools!” hissed Procopius, “do you want the entire city to hear? Perhaps we should bang a gong, or sing a few hymns?”

He hitched up his robe and made his way awkwardly down the ladder, exposing a good deal of pale thigh. His descent into the boat was scarcely less clumsy than mine, but the oarsman evidently knew better than to curse Belisarius’ private secretary. Biting his lip, he poled us out into the harbour.

Procopius hunkered down in the stern, and sat eyeing me with cool interest. “Coel ap Amhar,” he said, with a decent stab at British pronunciation, “I have watched your progress for some time now. The refugee who became a slave, who became a charioteer, who became a soldier. Equally at home in the Hippodrome, or the camp of the Heruli, or the imperial court.”

He rested his chin on his fist. “Your face is a blank canvas. Any number of personas can be painted on it and wiped clean, ready for the next. A play-actor.”

I bridled at that. “I am nothing of the sort,” I replied, careful to keep my voice low, “and have never pretended to be anything I am not. I do what is necessary to survive.”

“Of course. As we all do. But a great deal is necessary in order to survive in Constantinople. You have made your way in the city for over thirty years. From the gutter to an officer in Belisarius’ personal guard. Quite a tale.”

My pride gave a flicker. “I am still in the gutter,” I said, “you know my name, but not my quality. I am Coel ap Amhar ap Arthur, grandson of the First Warlord of the Island of the Mighty, descendent of the ancient line of British princes and kings. The blood of Coel Hen, ruler of the North, grandsire of Constantine the Great, runs in my veins.”

Procopius rubbed his thin hands and gave an enigmatic smile. “Belisarius told me you were proud. I suppose a man with nothing save his name and an old sword must cleave to pride. Step carefully, Coel, and be wary lest you fall further.”

He said nothing more, but lapsed into a brooding silence as the boat sculled across the dark waters to the looming bulk of Belisarius’ flagship.

This was the largest galley in the fleet, and one of the few old-fashioned Roman warships still in use. It was of the type called a bireme, with two staggered banks of oars and a long, narrow prow. Biremes were usually propelled by oars, with just a single sail, but this had been converted into a three-mast vessel. Unlike the lumbering transports and the smaller dromons, the galley had a sleek, dangerous look, and resembled some kind of dormant sea-monster as she lay resting at anchor inside the harbour.

We drew alongside, and a rope-ladder was let down the side. I was the first up, helped aboard by two brawny Sicilians.

I half-expected Belisarius to be there to greet me, but doubtless the general had more pressing matters to attend to. The ship’s captain, a heavy-set Greek with a long pink scar running from his temple to his jaw, regarded me with impatience.

“You’re to get below,” he said, jerking his thumb at the hatchway leading to the bowels of the ship, “and stay there until sent for. Quickly, if you please. I haven’t slept for two bloody days, and there is still much to do.”

I obeyed, and clambered down the ladder into the damp, musty-smelling space below deck. Even though the ship lay at anchor in peaceful waters, her gentle motion was enough to make my guts churn a little. The smell of tar and the salt tang of the sea in my nostrils brought back memories of the nightmarish voyage to Africa.

Procopius followed me down the ladder. “I am also a poor sailor,” he said, noting my pained expression, “but with luck our voyage shall be a short one.”

“Why do I have to hide down here?” I demanded, trying to ignore the thought of being cooped up below deck in a pool of my own vomit when the fleet sailed for Sicily.

“Your enemies may or may not know where you are,” he replied, “I have little doubt you were followed from Belisarius’ house, but the agents of Narses and Theodora cannot touch you here, aboard the general’s own flagship. This is his territory. Any violation of it would be perceived as a direct insult to Belisarius. Whatever petty grudges and feuds that may exist, Rome cannot afford to alienate its greatest soldier.”

He pursed his thin lips and leaned against a bulkhead. “For now, at any rate. If Belisarius fails in Italy, he will be dead or disgraced, and you will be fair game.”

I had discerned as much, and was anxious to get away from Constantinople as far and as swiftly as possible. “When does the fleet put to sea?” I asked.

“Tomorrow, if all goes to plan. Mundus is already laying siege to Salona, and Belisarius can afford no delay.”

A few more hours, then, and I would be safe. “What if Theodora and Narses send agents after me? No-one would notice a few men disguised as soldiers.”

“Perhaps. Theodora, at least, has no need for such crude stratagems. Her greatest agent will be among us, in plain view.”

It took me a moment to fathom his meaning. “Yes,” he said, reacting to the horror on my face, “Antonina is coming with us.”

4.

The fleet put to sea the next morning, propelled down the straits of the Bosphorus by a fair wind and the cheers of the multitude gathered on the docks. Their cheers were mingled with the dirge-like chants of the priests, clashing cymbals, screeching trumpets, and the tolling of every church bell in the city.

Before the African expedition, the Emperor and the Patriarch came to the harbour in person to give the fleet their blessing. They did so again now, though the Patriarch was so old he had to be carried in a litter. I heard the roar of the crowd treble in volume as Justinian arrived, preceded by the droning of bull-horns and escorted by six hundred of his personal guard, the Excubitors.

Heard, but did not see. I was confined below deck with two Huns to protect me and ensure I stayed hidden. They were a couple of surly, yellow-skinned brutes, typical of their race, and dripping with weaponry.

“No need to watch me so closely, boys,” I said with feigned cheerfulness, “I’m quite happy where I am.”

At last the moment I dreaded arrived. The ship began to move. I crouched in a corner, draping my cloak over me as a blanket and preparing for the worst.

The histories will tell you that the Roman fleet encountered no difficulty on the short voyage from Constantinople to Sicily. No storms delayed our progress, the winds were constant, and the Sicilian coast completely undefended. The Emperor’s ruse had worked. The Gothic fleet, such as it was, had sailed north carrying troops and supplies to reinforce their garrisons in Dalmatia.

To me, trapped below deck in the grip of sea-sickness, the voyage was a miserable and painful ordeal. The Huns kindly provided me with a bucket, which they emptied at regular intervals. Procopius visited me once or twice, to give me updates and check that I hadn’t puked myself to death.

“You are a better sailor than you claimed,” I whispered during one of his visits.

Procopius smiled weakly. He was even paler than usual, and trembled slightly, but his illness was nothing compared to mine. I could not walk, or eat, and shivered uncontrollably like a sick dog.

“Courage,” he replied, “we will soon be on dry land, and there will an end to this damned creaking and lurching. Belisarius means to land at Catania.”

This made sense. Catania was a desolate, rocky stretch of dried lava, near the base of Mount Etna. He had landed there before on the way to North Africa.

“What then?” I asked, drawing my blanket closer around me. My guts gave a sudden heave, and Procopius’ answer was delayed while I retched feebly into the bucket.

“We march on Palermo,” he said when I was done, “once the principal city falls, the rest of Sicily will follow. An easy conquest.”

Too easy, was my initial thought. Even a dotard like Theodatus would surely not have left the island undefended. My suspicious mind spun all kinds of alternatives. Perhaps the Goths were waiting in force at Palermo, to attack our much smaller army as we marched inland. Perhaps their fleet was hidden, somewhere among Sicily’s northern coastline, and would emerge to fall upon ours at Catania.

“What of Antonina?” I asked, dragging my mind away from these dreadful scenarios, “does she I know I am aboard?”

“Oh yes. I was with Belisarius when he mentioned your presence to her, two days ago. Our tame Briton, he called you.”

I swallowed hard, and rested my head against the hull. “How did she react?”

Procopius shrugged. “She didn’t. As far as her husband is aware, you mean nothing to her. She must have known you were aboard anyway.”

He squatted down on his haunches. “Attend to me, Coel,” he said severely, “for your life is most certainly in danger. Antonina has brought her son, Photius, the fruit of one of her previous marriages.”

I blinked at him. The name was vaguely familiar to me, but I had never seen Photius, and knew nothing of him.

“He is very young, barely grown to manhood,” Procopius added, “and has inherited his mother’s courage and fair looks. There, unless he is a better actor than I judge him to be, the resemblance ends. There is no deceit in him. Rather, he is impulsive, and constantly at Belisarius’ elbow, begging him for a command. Eager to win glory at the point of a sword.”

“Is he a threat to me?” I asked, who cared nothing for Photius or his ambitions.

“Possibly. He adores his mother, though she appears to care nothing for him. There is little he would not do to win her approval.”

“Including murder?”

“I don’t know. Perhaps. Antonina would not hesitate to use him as a weapon against you. The question is whether he would agree to it.”

Procopius thought for a moment, tapping his finger-tips together. “I think,” he said eventually, “that Belisarius should give this valiant young man a chance to prove himself.”

His eyes bored into mine. “Yes. Photius should be among the first to be sent ashore. Perhaps he can be dispatched on a scouting mission inland, with just a few men for company. Picked men.”

I knew what Procopius was implying. It filled me with revulsion, but I was too old and battle-hardened to be entirely scrupulous.

“You would go to such lengths, for me?” I asked quietly, “why?”

“Belisarius values you, as an officer and a friend,” he replied, rising, “he asked me to see you safe. He commands, and I obey. Not that I have any objection to seeing Antonina thwarted. She hates me, as she hates anyone with influence over her husband. She wants Belisarius all to herself.”

“Does she love him?”

Procopius gave a dry chuckle, the nearest he ever got to laughter. “Like an epicure loves his dinner. Antonina will eat him alive and then toss away the bones.”

I remained below deck until the fleet made landfall at Catania, which lies on the east coast of Sicily, facing the Ionian Sea. Despite the harsh and rugged landscape, there was a city here, much reduced from its former wealth and status after being sacked by the Vandals. The garrison offered no resistance, and opened the city gates to our soldiers after Belisarius promised not to sack the town or molest the inhabitants.

I was sick of concealment, and of languishing in my own stench in the stuffy hold. The Huns were sick of me too, and watched impassively as I crawled feebly up the ladder onto deck.

The sunlight was dazzling, and I had to shade my eyes until they grew used to the unaccustomed glare. I tried to stand on the deck as it gently rose and fell beneath me, but my shaking legs gave way.

A strong hand gripped my forearm as I fell, and hauled me upright. “Steady, old man,” said a familiar voice, “we shall have to find you a stick to lean on.”

I opened my eyes a crack and gazed on the rugged, dark-skinned features of Bessas, one of Belisarius’ chief cavalry officers. He was a Thracian of Gothic origin, fluent in the Gothic language, and I had often overheard him croaking songs in that harsh, guttural language.

Belisarius was a good judge of officers, and could scarcely have chosen a better man to lead his cavalry in Italy. Not only did Bessas speak the language of the enemy, but he was a tough, resourceful veteran of many campaigns, in his mid-fifties or thereabouts, and strong as a bull. His fingers had a grip like steel on my wasted arm. If he had increased the pressure, he might have snapped the bone.

“Coel, isn’t it?” he asked after I had mumbled my thanks, “our sickly Briton. God help us, you look like you’ve puked out your innards. I thought the Britons were a seafaring race?”

“I am the exception,” I groaned, clutching my aching belly, “though doomed to spend my life being dragged back and forth across the sea.”

Bessas smiled and patted me roughly on the back. “You can go ashore at once, if you like, ” he said, “look there.”

He pointed at the hundreds of longboats and other smaller vessels that populated the stretch of ocean between our fleet and the coast. The city of Catania was visible to the east, dominated by the brooding shadow of Mount Etna. Procopius had informed me that the volcano last erupted during the days of the Roman Republic, and swamped the greater part of the city in an ocean of boiling lava and hot ash.

Our entire army was disembarking, with a calm order and efficiency that made for a stark contrast to the last time I had witnessed a Roman army disembark, on the north coast of Africa. There all had been chaos and haste, as our sickness-ravaged soldiers struggled to shore in terror of the Vandals falling upon them at any moment.

I spotted Belisarius on the foredeck, standing among a little knot of officers and advisors. Procopius was among them, listening and nodding gravely while the soldiers talked. He was wearing his enigmatic little smile, and I could guess his opinion of what was being said.

Thankfully, there was no sign of Antonina, though a golden-haired young man among the officers might have been Photius. “I was appointed one of the general’s personal guard,” I said, “my place is by his side.”

“Admirable,” smirked Bessas, “but you’re no use to him in your current state. Go ashore and recuperate. For now, the conquest of Sicily will have to proceed without you.”

He gave me back to my Hunnish guards, who had followed me above deck like a couple of faithful hounds, and barked at them to take me ashore. Somehow I found the strength to climb down a rope ladder into one of the launches. I took my place alongside a group of Isaurian archers, and listened in silent misery to their excited chatter as the boat rowed into the shallows.

I could see our army deploying on the broad plain south-west of the city, thousands of tiny doll-figures busily pitching tents and digging temporary fortifications. As usual, Belisarius was taking no chances. The majority of his troops would camp outside the city, along with the baggage, while troops of light horse were sent out to scout the countryside.

Anxious to be rid of boats and sailing, I dropped over the side as soon as it seemed safe, and staggered through warm, waist-deep waters towards the beach. The Huns dogged my steps, which was a comfort. Nobody watching could have any doubt that I was well-guarded, and still enjoyed the favour and protection of Belisarius.

From Catania the army marched north-west, leaving a garrison of two hundred men to hold the city. Belisarius had furnished me with a horse, and I rode at an easy peace in the rearguard, enjoying the peace and beauty of the island. Sicily basked in the autumn sun, and the lengthy, oppressive heat of summer had given way to a pleasant mildness. The hedges on the roadsides were loaded with prickly pears. When my stomach had eased, I promptly ruined it again by indulging in too much of the succulent fruit, and afforded the troops much amusement by throwing up in a ditch.

Our army hugged the coast, while the fleet kept in sight to the east, but there was no need for such precautions. As Procopius had predicted, Sicily was an easy conquest, and we encountered no resistance on the march to Palermo. The native farmers presented us with gifts of bread and fruit, and expressed warm enthusiasm at being rescued from the tyranny of the Goths.

Some tyranny, I remember thinking as I looked around at the prosperous little villages and fertile, well-tilled farmland. The Sicilians had no cause to hate their occupiers.

“They might soon have cause to hate us,” remarked Procopius when he rode down the line to speak with me, “if we are defeated in Italy, the Goths will exact a bloody revenge for their treachery. If we are victorious, and the island remains part of the Empire, the Emperor will squeeze them for everything they have. Sicily produces abundant crops of grain. Justinian will take it all in annual tribute, leaving the inhabitants to live on grass.”

Palermo was approached from the south via a road winding through craggy mountains. Belisarius sent horsemen ahead to scout the route. I saw Photius among them, his fair hair gleaming like burnished gold as he galloped at the head of a troop of Herulii. They returned unscathed – Procopius had had no opportunity to put his murderous little plan into effect – to report that the road was unguarded.

The city was an astonishingly beautiful sight, its whitewashed walls gleaming like pale diamond. I first saw it from a ridge overlooking the bay. Blue mountains enclosed and concealed Palermo from the landward side, and the sea from the east. I shaded my eyes and glimpsed the first of our ships rounding the headland to the south.

I also saw that the harbour was undefended. The garrison had closed the gates against us, but the city was open to assault from land and sea. There was no Gothic army lying in wait, hidden among the mountains. Either deliberately or through sheer negligence, Theodatus had left Sicily to its fate.

Keen to score a bloodless victory, Belisarius sent forward messengers to demand Palermo’s surrender. The garrison sent back a haughty reply, ordering the Romans to withdraw from their walls or face destruction.

That night Belisarius summoned his officers to a council of war. My presence was also required, along with five other members of his personal guard. I struggled into my heavy chain mail and crested helmet, and limped down to the general’s pavilion.

“I will not waste time in a siege,” said Belisarius, thumping his fist on the table set up in the middle of his tent. A map of Sicily rested on the table, with various lead markers representing our forces.

Bessas was present, along with Constantine and Valentinian, the general’s two other chief officers, and Galierus, the admiral of the fleet. Procopius was there in his capacity as secretary. He briefly glanced up at me as I came in, and then sidelong at Photius.

Seen at close quarters, Antonina’s son had something of the Greek god about him. Tall and blonde, well-made and impossibly handsome in a sculpted sort of way, he seemed to glow with a strange inner light, putting the rest of us in the shade. All his attention was on Belisarius, and he paid me no heed whatsoever.

“Then we must take the city by storm,” said Bessas, leaning over to study the map, “I suggest an attack at dawn from east and west. The Gothic garrison will be spread thin to repel us. Bloody work, but it can be done.”

There was a murmur of agreement from Constantine and Valentinian. Like him, they were a couple of hard-faced veterans. The three of them put me in mind of a pack of old mastiffs.

Steel flashed in the gloom of the tent. Photius had drawn his spatha, and slapped it down on the table. “General, I beg the honour of leading the vanguard!” he piped in the high-pitched, breaking voice of adolescence, “I will be the first man up the ladders!”

Procopius smirked, and the officers looked unimpressed, but Belisarius regarded him fondly. “I think not, brave Photius,” he said gently, “your mother would nail my skin to the walls of Palermo if any harm befell you.”

The boy’s flawless skin flushed with angry blood, and his lower lip trembled. He looked on the verge of hysterics, but Belisarius lifted a hand to calm him.

“Peace,” he said patiently, “you will have a chance to show your valour. Not, however, in the vanguard. That is not the place for untried youths.”

Mention of Antonina made my skin prickle. I had glimpsed her a few times on the march, in a covered litter toward the rear of the army, lying full-length on a comfortable divan and sunning herself with the silk curtains drawn back. She had brought her ladies with her. At Palermo Belisarius set up a little camp for them apart from the main army, well away from the prying eyes and lustful impulses of our soldiers. I had heard rumours that she insisted on being present at her husband’s military councils, and even on giving him advice, but tonight she kept her distance.

Belisarius switched his attention to Galierus. “How deep are the waters of the bay?” he asked, “deep enough for our ships to approach within bow-shot of the walls?”

“Yes, general,” the admiral replied.

“Then we shall attack at dawn,” Belisarius said cheerfully, “and the city shall fall without a single casualty on our side. What do you think of that, Bessas?”

The old soldier and his colleagues looked nonplussed. “I think it most unlikely, sir,” he replied, “the Goths may have been abandoned by their king, but they are determined to resist.”

“There must be blood,” said Constantine, “and lots of it.”

Belisarius burst out laughing. I had rarely seen him in a better humour, and looked questioningly at Procopius, but he ignored me.

“God bless you, you old butchers,” said the general, wiping a tear of mirth from his eye, “there must be blood, eh? Well, let it be Gothic blood, for I have no intention of wasting ours on this flyspeck of a city.”

His officers looked offended, as well they might, for they were all proud men. Their sullen humour quickly melted to disbelief as Belisarius went on to outline his plan. I listened with mounting admiration for this extraordinary soldier, whom God had sent to rescue the Empire from disgrace and decay.

I spent the night in one of the guard tents close to Belisarius’ pavilion. In the morning we were roused early to accompany him onto the high bluffs overlooking Palermo. From there we watched Galierius, who had returned to the fleet after the council, carry out the general’s orders.

The bay of Palermo, as I have said, was open and undefended. During the night sixteen of our transports had used their oars to crowd into the harbour, as close to the sea-walls as the depth of water would allow. I could see the steel helmets of the Gothic soldiers on the battlements. They had no catapults or ballistae, and must have had a limited supply of arrows, for they did nothing but watch as our ships rowed closer.

Belisarius had ordered his Isaurian spearmen and archers to assemble in battalions on the plain beyond the eastern walls of the city. Scaling ladders had been fetched from the baggage, and three great battering rams pieced together. To the Goths, it must have looked as though we were preparing for an all-out assault.

It was a ruse. When our ships were within range, their crews used ropes and chains to hoist longboats and other smaller vessels up to the mastheads. Picked archers and javelin-men then clambered up the rigging and jumped into the boats.

Only now did the Goths realise what was afoot. The mastheads of our ships were much higher than the ramparts of the sea-defences. From their lofty height our men now unleashed a hail of arrows and javelins down on the exposed heads of the enemy. Some lit fire-arrows, and shot them into the town itself, where they set roofs and houses aflame and spread terror among the citizens.

“You see?” said Belisarius, nudging Bessas with his elbow, “I said we would take Palermo without losing a drop of Roman blood. We should have had a wager on it.”

“The city has not fallen yet,” grumbled the other man, but the general was right. The fighting spirit of the Goths was not as stout as their spokesmen had pretended. Even as we watched, the archers on the walls abandoned their posts and fled into the streets, leaving dozens of dead and wounded strewn on the ramparts, their bodies stuck full of missiles.

Panic rippled through the city. A bell sounded inside one of the larger churches, and we saw the tiny figures of the citizens running to and fro. Our archers continued to pour flaming arrows into the streets. More buildings caught fire, especially in the poorest quarters, where all was dry timber and thatch. Plumes of blackish smoke twisted into the sky, while orange flames danced and leaped from one roof to another.

Antonina was present, clothed all in white silk, which lent her the appearance of a goddess among so many rough, ill-favoured soldiers. She clung to her husband’s arm, and occasionally leaned in to whisper something in his ear. It angered me to see how he doted on her. All his attention should have been fixed on the battle below, but Antonina distracted him from his duty.

Do I sound envious? Perhaps a little. She was a great beauty, especially in those days, and unlike her friend Theodora required little artifice to sustain that beauty against the advancing armies of time. Her milky complexion remained as fresh as a young girl’s, though she was well into her thirties by now. The golden hair, which she wore bound up in the aristocratic Roman style, with long, curly ringlets framing her delicate cheeks, was as lustrous as ever. I feared her, and desired her, and all the time struggled to avert my eyes from her.

Thankfully, she paid no attention to me, or pretended not to. Her son Photius was absent. As a sop to the boy’s eagerness, Belisarius had allowed him to join one of the assault-parties mustered on the plain. He was safe enough, for they were destined to see no action.

“Not long now,” remarked Procopius, who had shuffled next to me. He was gazing complacently down at the chaos inside Palermo, like a hawk contemplating its prey.

The courage of the Goths soon wilted. Barely two hours after we begun our assault, their gates opened and a group of dignitaries filed out, waving olive branches in a token of peace.

Belisarius agreed to discuss terms. They were straightforward enough: in return for clemency, the Goths agreed to lay down their arms and surrender the city. Belisarius allowed the garrison to march out with honour, unarmed but with their banners flying, and to take ship for the Italian mainland.

With the fall of Palermo, his conquest of Sicily was effectively complete. Leaving a strong garrison to hold the city, he marched south to Syracuse, an ancient city in the south-east corner of the island.

The Gothic governor yielded it up without the faintest show of resistance, and Belisarius entered in triumph at the head of his bucelarii. I rode close behind him. My sickness had passed completely, and my spirits were buoyed by the rapturous reception.

By now our commander’s fame had spread to every corner of Sicily. The people of Syracuse flocked to welcome and applaud the conqueror of Africa and hail him as a new Caesar. Belisarius knew how to court popularity, and scattered gold coins and medals among the adoring crowds as he rode through the streets.

My joy was tempered with caution. The chants of Caesar! Caesar! were disquieting. Rome already had a Caesar in the form of Justinian, and it wouldn’t take much for the Emperor’s suspicions of Belisarius to flare hot again. He had his spies among our army. If Belisarius gloried too much in the acclaim of the mob, they would go racing back to Constantinople to pour fresh rumours of treason into Justinian’s ears.

Belisarius took up residence in the governor’s palace. There he received a steady flow of Gothic officers and diplomats from all over Sicily, come to bend the knee before him and swear allegiance to the Empire.

He took pains to dress in the plain garb of a soldier, and display no signs of arrogance or pretensions above his station. To no avail. The Goths insisted on addressing him in the most servile manner, as though he were indeed the Emperor instead of his representative. One or two even called him Caesar to his face.

I stood beside his chair as the Goths filed into the audience chamber. They were a beautiful people, tall and strongly-made, with auburn hair and fresh, clear-eyed features. The contrast with our swarthy, stunted eastern soldiers was marked, and I sometimes noticed the Goths glancing at us with contempt.

How, I could almost hear them thinking, have we been conquered by these dwarves?

It was a question my own ancestors must have asked themselves, after the Roman legions of old had defeated Caradog, the last native British chief in arms, and sent him in chains to Rome.

When business was done for the day, and the last Goth had departed, Belisarius relaxed gratefully in his chair and yawned.

“Wine, in Heaven’s name,” he croaked, massaging his dry throat. I poured some from a silver jug and handed him the goblet. He downed it one swallow, wiped his lips, and grinned at me.

“Lend me your sword, Coel,” he asked, stretching out his hand.

“Come,” he said impatiently when I hesitated, “do you think I am going to steal it? I merely wish to hold the thing for a moment.”

Reluctantly, I drew Caledfwlch and placed the hilt in his hand. He held the blade vertically before him and gazed at his reflection in the oiled and polished steel.

“I came, I saw, I conquered,” he murmured, “but unlike you, Julius, I lost not a single man.”

He weighed the sword in his hand, holding it at different angles and examining the eagles stamped into the hilt.

“I thought I might feel something,” he said, handing it back to me, “some tingle of power. Foolish. A sword is just a sword, no matter how many illustrious hands have wielded it. A tool for killing people.”

“I think otherwise, sir,” I said, hurriedly sliding Caledfwlch back into the sheath, “part of my grandsire’s soul rests inside this blade. I am certain of that. Perhaps Julius Caesar’s as well.”

He raised a skeptical eyebrow. “It must be crowded in there. Your belief smacks of paganism, Coel. A man’s soul cannot be hacked up like a loaf of bread. It is pure and indivisible.”

“Oh God,” he added, yawning again and stretching his long limbs, “let us not discuss such weighty matters. I have had a bellyful of them for one day.”

Despite his weariness, Belisarius seemed relaxed and cheerful. Sicily had fallen. The crushing weights of duty and responsibility had lifted, however briefly, from his narrow shoulders.

We spent the best part of three months in Sicily, waiting for the arrival of spring and the new campaign season. Belisarius made preparations to invade Italy, while diplomats sped back and forth between Theoderic in Ravenna and Justinian in Constantinople, striving to find some peaceful compromise.

I did remarkably little. The life of a guard officer during peacetime is not a taxing one. When not exercising or on duty, I explored the countryside around Syracuse in the company of Procopius, took care to avoid Antonina and Photius, and was reasonably content. Even in winter, Sicily was a fair island.

“I can picture myself living here,” I said to Procopius during one of our idle excursions, “settle down on a little farm with some local woman, hang Caledfwlch above the hearth, and raise goats.”

Procopius’ mouth twisted in distaste. “You have just described one my images of Hell,” he said sourly, “the sooner we can leave this patch of dirt, the better. So far this war has been more akin to a holiday.”

“What is wrong with that?” I asked, smiling at him, “if only all wars were so pleasant and straightforward.”

“I am a historian, Coel, among other things. My ambition is to witness and record great events, and the deeds of great men. How many pages will my account of the conquest of Sicily fill? One? It will require all my powers of hyperbole and exaggeration to make it worth the reading.”

“Then your history is in safe hands,” I said cheerfully, giving my reins a shake, “for I never knew a better liar.”

The idyll could not last. Word reached us of some disturbance in North Africa, where some of the Moorish desert tribes had revolted against Roman rule. They were inspired by an absurd prophecy, told by one of their female prophets, that they could only be defeated in battle by beardless soldiers. Our generals in Africa all sported beards on their chins, which was enough to persuade the Moors that they could rise up and overthrow our government.

Belisarius dispatched Procopius to Carthage, to talk with the Roman governor and assess the seriousness of the situation. I was sorry to see him go, for the secretary had become something of a friend, but he assured me of a swift return.

“The governor in Carthage is an old woman,” he sneered, “else he would have stamped on these Moorish desert-rats as soon as they raised their heads. Belisarius should be wiser in his choice of subordinates.”

He was gone for several weeks, during which time I amused myself in a dalliance with a shopkeeper’s daughter in Syracuse. She was my first woman since Elene, the Greek dancer who betrayed me, and I am sorry to say that I have only the vaguest memory of her appearance and character. I do recall that her parents had no objection to me staying in her bedchamber on a nightly basis. To the conqueror, as some wise man once said, the spoils.

Procopius did return, but not in the expected manner. He arrived at Syracuse in an open boat, half-dead of thirst, starvation and exposure, with just seven companions, all in an equally wretched state.

One of them, though I nor anyone else crowded into the harbour could believe it, was the governor of North Africa. His name was Solomon, and he stood in the prow of the boat, beating his breast and feebly uttering the same cry, over and over:

“Africa has fallen!”

5.

Belisarius had the seven men taken to the palace on a litter, and there cared for until any danger to their lives had passed. The governor, Solomon, insisted on speaking to Belisarius of the catastrophe that had befallen the Roman province in North Africa.

I accompanied the general to Solomon’s bedchamber – I was becoming Belisarius’ shadow – and listened to the sick man give his account.

Solomon was proud, far more competent and dutiful than Procopius gave him credit for, and had done his best to hold onto the province. Alas, it would have taken a man of far greater abilities to deal with the fearful catalogue of treason and rebellion that he reported.

“The trouble started with the Moors,” he said weakly, “at first it was just a few raids on isolated villages. Nothing out of the ordinary, and I left our local garrisons to cope with them. Then I received word that some of the desert tribes had formed a coalition. They fell upon a detachment of our infantry and cut our soldiers all to pieces.”

He paused to cough and drink some water. I glanced at Belisarius. The general’s face was as grim as ever I saw it, like a bust carved in stone.

Besides one other guardsman and myself, no-one else was present. The shutters on the bedchamber’s single window were closed, blocking out the wintry afternoon sun. Belisarius wanted the details of the African disaster to be kept secret for as long as possible.

“When I heard of the massacre, I resolved to act,” Solomon continued, “and led out our garrison in force from Carthage to give battle.”

Belisarius gave a slight nod of approval. He would have done no less.

“We met the Moors on a fair open field and utterly routed them. You know what poor soldiers they make. They wear no armour, and their flimsy shields and javelins were no match for Roman arms. I followed up, hoping to destroy the survivors, and found them entrenched in a strong position on Mount Burgaon. I threw in our infantry, and in one assault they cleared the trenches and drove the Moors like sheep, until the desert ran red with their tainted blood.”

“So far, a textbook campaign,” murmured Belisarius, “what went wrong?”

Solomon laid his head back on the pillows and closed his eyes. “The tribes retreated into the recesses of the desert, where we could not follow,” he said, “and then our men started to disintegrate. I did not realise until it was too late, but the army was rotten with sedition. Most of the protestors were Arians. The heresy is still strong in Africa. They complained of Justinian’s harsh edits against their faith, and that they were barred from baptizing their children. They complained that the plunder taken from the defeated Moors was not shared out equally. They complained of these and other matters with loud and bitter voices, and the disaffection quickly spread among our orthodox troops. Meanwhile the Moors were allowed to recover their strength.”

It was now that Solomon’s failure became apparent. As governor and commander-in-chief, he should have stamped down hard on the dissenting voices. Belisarius was of a naturally merciful disposition, but had never hesitated from applying old-fashioned Roman discipline when necessary. I remember the pair of drunken Hunnish confederates he had executed on the hills above Heraclea, and their headless bodies tossed into the sea.

“Unknown to me, some of our garrison troops met at Mount Auras,” said Solomon, “and there formed a pact with the Moors and the worst of the Arian dissenters. They raised the standard of revolt against Roman rule. At the same time, a ship bearing four hundred Vandals taken captive in the recent wars was on its way to our eastern provinces. The Vandals were supposed to enlist in our armies there. As the ship sailed past the African coast, the Vandals rose in revolt, slaughtered the sailors and marines, and forced the captain to land. They joined with the rebels at Mount Auras.”

He passed a hand over his face. “The Arian poison had even spread to Carthage. Some of the fanatics there plotted against my life, and chose Easter as the best time to murder me. They planned to have me killed as I entered the cathedral before the ceremony. However, when news reached them of the rebel host gathered at Mount Auras, they threw aside all caution and forswore their allegiance to Rome.”

Belisarius could contain himself no longer. “And what in the hells were you doing, while all this was going on?” he demanded through gritted teeth.

I had never seen him so angry. His sallow cheeks had turned the colour of fresh steak, and his fists were clenched until the bony knuckles turned white. A thick blue vein throbbed dangerously on his forehead.

“I was planning to march on the rebels, sir,” Solomon replied hastily, “but the conspiracy in Carthage took me by surprise. The Arians took to the streets at night. They smashed and plundered the houses of wealthy citizens and slaughtered all in their path, regardless of age, rank or degree. I tried to raise the garrison to sally out against them, but our men were seized with terror, and refused to move. When the mutineers forced the doors of the palace, I was obliged to flee for my life, and take refuge in a chapel. Procopius and a few loyal attendants fled with me. When dawn broke, and the mutineers were drowsy with wine and murder, we crept down to the harbour and stole a boat.”

“And so came here,” said Belisarius. He pressed his fingertips together and held them to his lips for a moment. I watched him in silence, wondering what even that superb military mind could conceive to reverse such a disaster.

“How many of our ships are ready to sail immediately?” he asked suddenly.

“Just your flagship, sir,” I replied, “the rest of our fleet is either being re-fitted, or scattered among the other Sicilian ports.”

Just for a second, the briefest of seconds, I thought his resolution faltered. A shadow crawled over his face, but then vanished.

“My galley can carry no more than a hundred men,” he said briskly, “but that will have to do. We sail for Carthage. Now.”

He turned on his heel and strode to the door. I and my fellow guardsman exchanged panicked glances and hurried after him down the corridor outside.

“Sir,” I cried, struggling to keep pace with his long legs, “forgive my presumption, but how can you hope to retake North Africa with just a hundred men?”

Belisarius didn’t even break step. “No questions, Coel,” he snapped, “my forebears never brooked questions from their subordinates. I should have you flogged. My God, would the likes of Agrippa or Agricola have put up with junior officers bleating at them? Roman discipline is much decayed.”

In this mood, it was impossible to tell if he was joking. “Summon my personal guard,” he added, “I will take a hundred of the best with me. Once we reach Carthage, I will call upon the garrison to join me. I left two thousand men to defend the city. More than enough.”

A host of objections flew to my lips, and stayed there. I knew the general was fond of me, and also knew that he would have the skin flayed off my back if I irked him any further. Leaving him to bellow for his armour, I ran down to the barracks to rouse his guard.

We hurriedly assembled on the drill-yard outside the palace. Belisarius soon appeared, buckling on his breastplate and trailed by a group of officers, including Photius. The godlike young man looked immaculate in a gleaming silver breastplate and plumed helm, as though he had been waiting in his armour for the order to march.

His personal guard were formed into an old-fashioned maniple or cohort of five hundred men, divided into six centuries of eighty men each. They were the cream of his Veterans and bucelarii, or men like me who had performed well enough in past campaigns to be admitted to their ranks. Above all, we were men Belisarius felt he could trust on the battlefield and off it.

“First Century, with me,” he shouted as our men tumbled into line, “the rest, dismissed.”

I was technically appointed to the Third Century, but there was no question of me staying behind.

The eighty men of the First followed the general as he hurried down to the docks. There were a few Egyptian sailors lounging near the jetty where Belisarius’ ship was moored. He pressed these unfortunates into service, roaring at them to get aboard and make ready to sail, if they valued their lives. Abandoning their games of dice, the Egyptians scrambled aboard the galley and started hauling on ropes.

We followed, pounding in double file up the gangplank. It felt as though I had barely drawn breath since Belisarius threatened to have me flogged. The wind was set fair, and my stomach gave a lurch as the mainsail billowed and the steersman turned the ship’s prow south.

Over a hundred miles of open sea lay between Syracuse and Carthage. Our ship sped through the sparkling blue waters like a dolphin, propelled by Heaven-sent winds and the fierce will of Belisarius. He stood at the prow, jaw clenched, eyes fixed on the western horizon.

Meanwhile I clung to the side and emptied my breakfast into the sea. I hated myself for showing such weakness, especially in front of my comrades, even though they tactfully looked away.

“God preserve my strength,” I muttered between dry heaves, touching the hilt of Caledfwlch for luck. I would need all of my grandsire’s warlike skill and resolve when we reached Carthage.

We started early in the morning, and arrived within sight of the Tunisian coast just before dusk. The scattered lights of Carthage lit up the dark mass of the coastline, like thousands of yellow stars gleaming in the night sky.

Belisarius called me over to his side. “There,” he said, pointing to the south of the city, “the rebel host.”

I clung to a rope and squinted at a smaller gathering of lights, several miles distant of the city. If Belisarius was right, the rebels had quit Carthage and set up camp on the desolate plains outside.