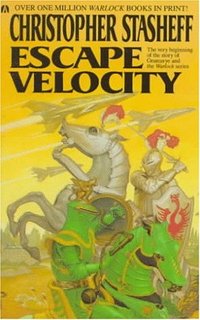

Cristopher Stasheff

Escape Velocity

Warlock in Spite of Himself - 1

1

She was a girl. Dar knew it the moment he saw her.

That wasn’t as easy as it sounds. Really. Considering that she was shaved bald and was wearing a baggy gray flannel coverall, Dar was doing pretty well to identify her as human, let alone female. It would’ve been a much better bet that she was a department-store mannequin in one of those bags that are put on them between outfits, to protect them in case somebody with a plastic fetish comes along.

But she moved. That’s how Dar knew she was human.

And he was just in from a six-week trading tour and was just about to go out on another one (Cholly, the boss, was shorthanded this month; one of his traders had been caught shaving percentage points with Occam’s Razor). Which meant, since the Wolmar natives didn’t allow their womenfolk to meet strangers, that for the last six weeks Dar had seen things that were human, and things that were female, but never both at the same time; so he was in a prime state to recognize a girl if one happened along.

This one didn’t “happen”—she strode. She nearly swaggered, and she stepped down so hard that Dar suspected she was fighting to keep her hips from rolling. It sort of went with the gray jumpsuit, bald head, and lack of makeup.

She sat down on a bar stool, and waited. And waited. And waited.

The reason she waited so long was that Cholly was alone behind the bar today and was discussing the nature of reality with a corporal; he wasn’t about to give up a chance at a soldier.

Not that the girl seemed to mind. She was ostentatiously not looking at the two privates at the other end of the bar, but her ears fairly twitched in their direction.

“He niver had a chance,” the gray-haired one burbled around his cigar. “He but scarcely looked up, and whap! I had him!”

“Took him out good and proper, hey?” The blond grinned.

“Out! I should say! So far out he an’t niver coming back! Mark my words, he’ll buy the farm! Buy it for me yet, he will!”

The girl’s lips pinched tight, and her throat swelled the way someone’s does when they can’t hold it in anymore and it’s just got to bust loose; and Dar figured he’d better catch it, ‘cause the soldiers wouldn’t understand.

But Dar would. After six weeks without women, he was ready to understand anything, provided it came from a female.

So he sidled up to lean on the bar, neatly intersecting her line of sight, smiled with all the sincerity he could dredge up, and chirped, “Service is really slow around here, isn’t it?”

She got that blank look of total surprise for a minute; then her lip curled, and she spat, “Yes, unless you’re looking for death! You seem to dish it up awfully fast around here, just because you’re wearing a uniform!”

“ ‘Uniform’?” Dar looked down at his heavy green coveralls and mackinaw, then glanced over at the two soldiers, who were looking surprised and thinking about feeling offended. He turned back to the girl, and said quickly. “ ‘Fraid I don’t follow you, miz. Hasn’t been a killing around here all year.”

“Sure,” she retorted, “it’s January seventh. And what were those two bums over there talking about, if it wasn’t murder?”

She had to point. She just had to. Making sure Dar couldn’t pretend she’d been talking about two CPOs walking by in the street, no doubt. To make it worse, judging by their accents, the two privates were from New Perth, where “bum” had a very specific meaning that had absolutely nothing to do with unemployment.

The older private opened his mouth for a bellow, but Dar cut in quicker. “Points, miz. You can believe me or not, but they were talking about points.”

She looked doubtful for a fraction of a second, but only a fraction. Then her face firmed up again with the look of someone who’s absolutely sure that she’s right, especially if she’s wrong. She demanded, “Why should I believe you? What are you, if you aren’t a soldier?”

Dar screwed up his hopes and tried to look casual. “Well, I used to be a pilot …”

“Am I supposed to be impressed?” she said sourly.

“They told me girls would be, when I enlisted.” Dar sighed. “It’s got to work sometime.”

“I thought this planet was an Army prison.”

“It is. The Army has ships too.”

“Why?” She frowned. “Doesn’t it trust the Navy to do its shipping?”

“Something like that.”

“You say that with authority. What kind of ship did you pilot—a barge?”

“A space tug,” Dar admitted.

She nodded. “What are you now?”

Dar shrugged, and tried to look meek. “A trader.”

“A trader?” She spoke with such gleeful indignation that even Cholly looked up—for a second, anyway. “So you’re one of the vampires who’re victimizing the poor, helpless natives!”

“Helpless!” the old private snorted—well, roared, really; and Dar scratched his head and said, “Um, ‘fraid you’ve got your cables crossed, miz. I wouldn’t exactly say who’s doing the victimizing.”

“Well, I would!” she stormed. “Stampeding out here, victimizing these poor people, trying to take over their land and destroy their culture—it’s always the same! It’s all part of a pattern, a pattern as old as Cortez, and it just goes on and on and on! ‘Don’t give a damn what the people want; give ‘em technology! Don’t give a damn whether or not their religion’s perfectly adequate for ‘em—give ‘em the Bible! Don’t ask whether or not they own the place—herd ‘em onto reservations! Or make slaves of ‘em!’ Oh, I’ve heard about it, I’ve read about it! It’s just starting here, but you wait and see! It’s genocide, that’s what it is! It’s the worst kind of imperialism! And all being practiced by the wonderful, loyal soldiers of our miraculously democratic Interstellar Dominion Electorates! Imperialists!” And she spat.

The two soldiers swelled up like weather balloons, and the weather was going to be bad, so Cholly yanked himself out of his talk and hurried down to the end of the bar to put in a soothing word or two. As he passed Dar, he muttered, “Now, then, lad, whut’ve I told ye? Reason, don’cha know, now, Dar, reason! Try it, there’s a good fellow, just try it! An’ you’ll see. Sweet reason, now, Dar!” And he hurried on down to the end of the bar.

Dar thought he’d been trying reason already, and so far it hadn’t been turning out sweetly; but he took a deep breath, and set himself to try it again. “Now, then, miz. Uh, first off, I’d say we didn’t exactly stampede out here. More like a roundup, actually.”

She frowned. “What’re you talking about? … Oh. You mean because this is a military prison planet.”

“Well, something of that sort, yes.”

She shrugged. “Makes no difference. Whether you wanted to come here or not, you’re here—and they’re shipping you in by the thousands.”

“Well, more like the hundreds, really.” Dar scratched behind his ear. “We get in maybe two hundred, three hundred, ah …”

“Colonists,” she said sternly.

“… prisoners,” Dar finished. “Per year. Personally, I’d rather think of myself as a ‘recruit.’ ”

“Doesn’t make any difference,” she snapped. “It’s what you do after you get here that counts. You go out there, making war on those poor, innocent natives … and you traders go cheating them blind. Oh, I’ve heard what you’re up to.”

“Oh, you have?” Dar perked up. “Hey, we’re gettin’ famous! Where’d you hear about us, huh?”

She shrugged impatiently. “What does it matter?”

“A lot, to me. To most of us, for that matter. When you’re stuck way out here on the fringe of the Terran Sphere, you start caring a lot about whether or not people’ve ever heard about your planet. Be nice to feel even that important.”

“Mm.” Her face softened a moment, in a thoughtful frown. “Well … I’m afraid this won’t help much. I used to be a clerk back on Terra, in the records section of the Bureau of Otherworldly Activities—and a report about Wolmar came through occasionally.”

“Oh.” Dar could almost feel himself sag. “Just official reports?”

She nodded, with a vestige of sympathy. “That’s right. Nobody ever saw them except bureaucrats. And the computer, of course.”

“Of course.” Dar heaved a sigh and straightened his shoulders. “Well! That’s better than nothing … I suppose. What’d they say about us?”

“Enough.” She smiled vindictively. “Enough so that I know this is a prison planet for criminal soldiers, governed by a sadomasochistic general; that scarcely a day passes when you don’t have a war going on…”

“Holidays,” Dar murmured, “and Sundays.”

“ ‘Scarcely,’ I said! And that you’ve got an extremely profitable trade going with the natives for some sort of vegetable drug, in return for which you give them bits of cut glass and surplus spare parts that you order through the quartermaster.”

“That’s all?” Dar asked, crestfallen.

“All!” She stared, scandalized. “Isn’t that enough? What did you want—a list of war crimes?”

“Oh …” Dar gestured vaguely. “Maybe some of the nice things—like this tavern, and plenty of leave, and …”

“Military corruptness. Slackness of discipline.” She snorted. “Sure. Maybe if I’d stayed with the Bureau, a piece of whitewash would’ve crossed my desk.”

“If you’d stayed with them?” Dar looked up. “You’re not with BOA anymore?”

She frowned. “If I were working for the Bureau, would I be here?”

Dar just looked at her for a long moment.

Then he shook himself and said, “Miz, the only reason I can think of why you would be here is because BOA sent you. Who could want to come here?”

“Me,” she said, with a sardonic smile. “Use your head. Could I dress like this if I worked for the government?”

Dar’s face went blank. Then he shrugged. “I dunno. Could you?”

“Of course not,” she snapped. “I’d have to have a coiffeured hairdo, and plaster myself with skintight see-throughs and spider heels. I had to, for five years.”

“Oh. You didn’t like it?”

“Would you like to have to display yourself everyday so a crowd of the opposite sex could gawk at you?”

Dar started a slow grin.

“Well, I didn’t!” she snapped, reddening.

“And that’s why you quit?”

“More than that,” she said grimly. “I got fed up with the whole conformist ragout, so I aced out instead.”

“ ‘Aced out’?” Dar was totally lost.

“Aced out! Quit! Got out of all of it!” she shouted. “I turned into a Hume!”

“What’s a ‘Hume’?”

She stared, scandalized. “You really are away from it all out here, aren’t you?”

“I’ve kinda been trying to hint about something along those lines, yes. We get the news whenever a freighter lands, about three times a year. So until they invent faster-than-light radio, we’re not going to know what’s happening on Terra until a couple of years after it’s happened.”

She shook her head in exasperation. “Talk about primitive! All right … a Hume is me—a nonconformist. We wear loose gray coveralls like this to hide our bodies from all those lascivious, leering eyes. We shave our heads, so we don’t have to do up a pompadour everyday. And we don’t submit to those prisons society calls ‘jobs’; we’d rather be poor. We’ve put in our time, we’ve got some savings, and between that, our GNP share, and whatever we can pick up at odd jobs, we manage to keep going. We do what we want, not what the I.D.E. wants. That’s what’s a Hume.”

Dar nodded, lips pursed and eyes slightly glazed. “Uh. But you don’t conform. Right.”

“I didn’t say that, gnappie! I said we’re nonconformists.”

“Uh—right.” Dar nodded. “I see the difference—or I’ll try to.”

She turned on him, but Cholly got there first. “Do thet, lad! Do thet, and you’ll make me proud of you! But you see, you have to know the history of it, don’t you? Of course you do; can’t understand nothing wot’s happening in human society if you don’t know the history of it. The first who was called ‘Nonconformists,’ see, they started showing up toward the end of the 1500s, now. Shakespeare wrote one of ‘em into Twelfth Night, called him ‘Malvolio.’ Puritans, they was, and Calvinists, and Baptists, too, and Anabaptists, all manner of Protestant sects what wasn’t Church of England. And the Anglicans, they lumped ‘em all together and called ‘em ‘Nonconformists’ (the name got put on ‘em from the outside, you see, the way it always does) ‘cause they didn’t conform to the Established Church (what was C. of E., of course). Yet if you sees the pictures of ‘em, like Cromwell’s Roundheads, why! they’re like to one another as bottles in a case! Within their opposition-culture, you sees, they conformed much more tightly than your C. of E.s—and so it has been, ever since. When you call ‘em ‘nonconformists,’ it doesn’t mean they don’t conform to the standards of their group, but that their group don’t conform to the majority culture—and that’s why any opposition-culture’s called ‘nonconformist.’ Now then, Sergeant …” And he was off again, back to the reality case.

The Hume stared after him, then nodded thickly. “He’s right, come to think of it …” She gave herself a shake, and scowled at Dar. “What was that—a bartender, or a professor?”

“Cholly,” Dar said, by way of explanation. “My boss.”

The Hume frowned. “You mean you work here? WHOA!”

Dar saw the indignation rise up in her, and grinned. “That’s right. He’s the owner, president, and manager of operations for the Wolmar Pharmaceutical Trading Company, Inc.”

“The boss drug-runner?” she cried, scandalized. “The robber baron? The capitalist slave-master?”

“Not really. More like the bookkeeper for a cooperative.”

She reared up in righteous wrath, opening her mouth for a crushing witticism—but couldn’t think of any, and had to content herself with a look of withering scorn.

Dar obligingly did his best to wither.

She turned away to slug back a swallow from her glass—then stared, suddenly realizing that she had a glass.

Dar glanced at Cholly, who looked up, winked, nodded, and turned back to discussing the weightier aspects of kicking a cobble.

The Hume seemed to deflate a little. She sighed, shrugged, and took another drink. “Hospitable, anyway …” She turned and looked up at Dar “Besides, can you deny it?”

Dar ducked his head—down, around, and back up in hopes of a sequitur. “Deny what?”

“All of it! Everything I’ve said about this place! It’s all true, isn’t it? Starting with your General Governor!”

“Oh. Well, I can deny that General Shacklar’s a sadist.”

“But he is a masochist?”

Dar nodded. “But he’s very well-adjusted. As to the rest of it … well, no, I can’t deny it, really; but I would say you’ve gotten the wrong emphasis.”

“I’m open to reason,” the Hume said, fairly bristling. “Explain it to me.”

Dar shook his head. “Can’t explain it, really. You’ve got to experience it, see it with your own eyes.”

“Yes. Of course.” She rolled her eyes up. “And how, may I ask, am I supposed to manage that?”

“Uhhhh …” Dar’s mind raced, frantically calculating probable risks versus probable benefits. It totaled up to 50-50, so he smiled and said, “Well, as it happens, I’m going out on another trading mission. You’re welcome to come along. I can’t guarantee your safety, of course—but it’s really pretty tame.”

The Hume stared, and Dar could almost see her suddenly pulling back, withdrawing into a thickened shell. But something clicked, and her eyes turned defiant again. “All right.” She gulped the rest of her drink and slammed the glass back down on the bar. “Sure.” She stood up, hooking her thumbs in her pockets. “Ready to go. Where’s your pack mule?”

Dar grinned. “It’s a little more civilized than that—but it’s just out back. Shall we?” And he bowed her toward the door.

She spared him a last withering glance, and marched past him. Dar smiled, and followed.

As they passed Cholly and the sergeant, the bartender was saying earnestly, “So Descartes felt he had to prove it all, don’t you see—everything, from the ground up. No assumptions, none.”

“Ayuh. Ah kin see thet.” The sergeant nodded, frowning. “If’n he assumed anything, and thet one thing turned out to be wrong, everything else he’d figgered out’d be wrong, too.”

“Right, right!” Cholly nodded emphatically. “So he stopped right there, don’t you see, took out a hotel room, and swore he’d not stir till he’d found some one thing he could prove, some one way to be sure he existed. And he thought and he thought, and it finally hit him.”

“Whut dud?”

“He was thinking! And if’n he wuz thinking, there had to be someone there to do the thinking! And that someone was him, of course—so the simple fact that he was thinking proved he existed!”

“Ay-y-y-y-uh!” The sergeant’s face lit with the glow of enlightenment, and the Hume stopped in the doorway, turning back to watch, hushed, almost reverent.

Cholly nodded, glowing, victorious. “So he laid it out, right then and there, and set it down on paper, where he could read it. Cogito, ergo sum, he wrote—for he wrote in Latin, don’t you see, all them philosphers did, back then—Cogito, ergo sum; and it means ‘I think; therefore: I exist.’ ”

“Ay-y-y-y-uh. Ayuh, I see.” The sergeant scratched his head, then looked up at Cholly again. “Well, then—that’s whut makes us human, ain’t it? Thinking, I mean.”

The Hume drew in a long, shuddering breath, then looked up at Dar. “What is this—a tavern, or a college?”

“Yes.” Dar pushed the door open. “Shall we?”

They came out into the light of early afternoon. Dar led the Hume to a long, narrow grav-sled, lumpy with trade goods under a tarpaulin. “No room for us, I’m afraid—every ounce of lift has to go to the payload. We walk.”

“Not till I get an answer.” The Hume planted her feet, and set her fists on his hips.

“Answer?” Dar looked up, surprised. “To what?”

“To my question. This boss of yours—what is he? A capitalist? An immoral, unethical, swindling trader? A bartender? Or a professor?”

“Oh.” Dar sat down on his heels, checking the fastenings of the tarp. “Well, I wouldn’t really call him a capitalist, ‘cause he never really does more than break even; and he’s as moral as a preacher, and as ethical as a statue. And he’s never swindled anybody. Aside from that, though, you’ve pretty well pegged him.”

“Then he is a professor!”

Dar nodded. “Used to teach at the University of Luna.”

The Hume frowned. “So what happened? What’s he doing tending bar?”

Dar shrugged. “I think he got the idea from his last name: Barman.”

“ ‘Barman’?” She frowned. “Cholly Barman? Whoa! Not Charles T. Barman!”

Dar nodded.

“But he’s famous! I mean, he’s got to be the most famous teacher alive!”

“Well, notorious, anyway.” Dar gave the fastenings a last tug and stood up. “He came up with some very wild theories of education. I gather they weren’t too popular.”

“So I heard. But I can’t figure why; all he was saying was that everybody ought to have a college education.”

“And thereby threatened the ones who already had it.” Dar smiled sweetly. “But it was more than that. He thinks all teaching ought to be done on a one-to-one basis, which made him unpopular with the administrators—imagine having to pay that many teachers!—and thought the teaching ought to be done in an informal environment, without the student realizing he was being taught. That meant each professor would have to have a cover role, such as bartending, which made him unpopular with the educators.”

The Hume frowned. “I didn’t hear about that part of it.”

Dar shrugged. “He published it; it was there to read, if you managed to get hold of a copy before the LORDS party convinced the central book-feed to quit distributing it down the line to the retail terminals.”

“Yes.” Her mouth flattened, as though she’d tasted something sour “Freedom of the press isn’t what it used to be, is it?”

“Not really, no. But you can see why the talk gets so deep, back in there; Cholly never misses a chance to do some teaching on the side. When he’s got ‘em hooked on talk, he lets ‘em start hanging out in the back room—it’s got an open beer keg, and wall-to-wall books.”

She nodded, looking a little dazzled. “You don’t sound so ‘innocent of books’ yourself, come to think of it.”

Dar grinned, and picked up the towrope. “Shall we go?”

They trudged down the alley and out into the plastrete street, the Hume walking beside Dar, brooding.

Finally she looked up. “But what’s he doing out here? I mean, he’s putting his theories into practice, that’s clear—but why here? Why not on some fat planet in near Terra?”

“Well, the LORDS seem to have had something to do with that.”

“That bunch of fascists! I knew they were taking over the Assembly—but I didn’t know they were down on education!”

“Figure it out.” Dar spread his hands. “They say they want really efficient central government; they mean totalitarianism. And one of the biggest threats to a totalitarian government is a liberal education.”

“Oh.” Her face clouded. “Yes, of course. So what did they do?”

“Well, Cholly won’t go into much detail about it, but I gather they tried to assassinate him on Luna, and he ran for it. The assassins chased him, so he kept running—and he wound up here.”

“Isn’t he still worried about assassins?”

Dar flashed her a grin. “Not with Shacklar running the place. By the way, if we’re going to be traveling together, we really oughta get onto a first-name basis. I’m Dar Mandra.” He held out his hand.

She seemed to shrink back again, considering the offer; then, slowly, she extended her own hand, looking up at him gravely. “Samantha Bine. Call me Sam.”

Dar gave her hand a shake, and her face his warmest smile. “Good to meet you, Sam. Welcome to education.”

“Yes,” she said slowly. “There is a lot here that wasn’t in the reports, isn’t there?”

Sam looked at the town gate as they passed through it, and frowned. “A little archaic, isn’t it? I thought walled towns went out with the Middle Ages.”

“Only because the attackers had cannon, which the Wolmen didn’t have when this colony started.”

“But they do now?”

“Well,” Dar hedged, “let’s say they’re working on it.”

“Hey! You, there! Halt!”

They looked back to see a corporal in impeccable battle-dress running after them.

“Here now, Dar Mandra!” he panted as he caught up with them. “You know better than to go hiking out at two o’clock!”

“Is it that late already?” Dar glanced up at the sun. “Yeah, it is. My, how the time flies!” He hauled the grav-sled around. “Come on, Sam. We’ve gotta get back against the wall.”

“Why?” Sam came along, frowning. “What’s wrong?”

“Nothing, really. It’s just that it’s time for one of those continual battles you mentioned.”

“Time?” Sam squawked. “You mean you schedule these things?”

“Sure, at 8 a.m. and 2 p.m., eight hours apart. That gives everybody time to rest up, have lunch, and let it digest in between.”

“Eight hours?” She frowned. “There’s only six hours between eight and two!”

“No, eight. Wolmar’s got a twenty-eight-hour day, so noon’s at fourteen o’clock.” He pulled the sled up against the wall and leaned back against it. “Now, whatever you do, make sure you stay right here.”

“Don’t worry.” Sam settled herself back against the plastrete, folding her arms defiantly. “I want to get back to Terra to tell about this. I don’t intend to get hit by a stray beam.”

“Oh, no chance of that—but you might get trampled.”

Brightly colored figures rose over the ridge, and came closet Sam stiffened. “The natives?”

Dar nodded. “The Wolmen.”

“Purple skin?”

“No, that’s a dye they use to decorate their bodies. I think the chartreuse loincloths go rather well with it, don’t you?”

The warriors drew up in a ragged line, shaking white-tipped poles at the walled town and shouting.

“Bareskins go down today! Jailers of poor natives! Wolmen break-um free today! Bareskins’ Great Father lose-um papooses!”

“It’s traditional,” Dar explained.

“What? The way they talk?”

“No, just the threats.”

“Oh.” Sam frowned. “But that dialect! I can understand why they’d speak Terrese, but why the pidgin grammar and all those ‘ums’?”

Dar shrugged. “Don’t know, actually. There’re some of us have been wondering about that for a few years now. The best we can come up with is that they copped it from some stereotyped presentation of barbarians, probably in an entertainment form. Opposition cultures tend to be pretty romantic.”

The soldiers began to file out of the main gate, lining up a hundred yards away from the Wolmen in a precise line. Their bright green uniforms were immaculately clean, with knife-edge creases; their boots gleamed, and their metal work glistened. They held their white-tipped sticks at order arms, a precise forty-five degree angle across their bodies.

“Shacklar’s big on morale,” Dar explained. “Each soldier gets a two-BTU bonus if his boots are polished; another two if his uniform’s clean; two more if it’s pressed; and so on.”

The soldiers muttered among themselves out of the corners of their mouths. Dar could catch the odd phrase:

“Bloody Wolmen think they own the whole planet! Can’t tell us what t’ do! They think they c’n lord it over us, they got another think comin’!”

Sam looked up at Dar, frowning. “What’s that all about? It almost sounds as though they think the Wolmen are the government!”

“They do.” Dar grinned.

Sam scanned the line of troops, frowning. “Where’re their weapons?”

“Weapons!” Dar stared down at net scandalized. “What do you think we are—a bunch of savages?”

“But I thought you said this was a …”

BR-R-R-R-ANK! rolled a huge gong atop the wall, and the officers shouted, “Charge!”

The Wolmen chiefs whooped, and their warriors leaped down toward the soldiers with piercing, ululating war cries.

The soldiers shouted, and charged them.

The two lines crashed together, and instantly broke into a chaotic melee, with everyone yelling and slashing about them with their sticks.

“This is civilized warfare?” Sam watched the confusion numbly.

“Very,” Dar answered. “There’s none of this nonsense about killing or maiming, you see. I mean, we’re short enough on manpower as it is.”

Sam looked up at him, unbelieving. “Then how do you tell who’s won?”

“The war-sticks.” Dar pointed. “They’ve got lumps of very soft chalk in the ends. If you manage to touch your opponent with it, it leaves a huge white blotch on him.”

A soldier ran past, with a Wolman hot on his heels, whooping like a Saturday matinee. Suddenly the soldier dropped into a crouch, whirled about and slashed upward. The stick slashed across the Wolman’s chest, leaving a long white streak. The Wolman skidded to a stop, staring down at his new badge, appalled. Then his face darkened, and he advanced toward the soldier, swinging his stick up.

“Every one loses his temper now and then,” Dar murmured.

A whistle shrilled, and a Terran officer came running up. “All right, that’ll do! You there, tribesman—you’re out of the war, plain as the chalk on your chest! On your way, now, or I’ll call one o’ yer own officers.”

“Oppressor of poor, ignorant savages!” the Wolman stormed. “We rise-um up! We beat-um you down!”

“Ayuh, well, tomorrow, maybe. Move along to the sidelines, now, there’s a good chap!” The officer made shooing motions.

The Wolman stood stiffly, face dark with rebellion. Then he threw down his chalk-stick with a snarl and went stalking off toward a growing crowd of men, soldiers and Wolmen alike, standing off to the east, well clear of the “battle.”

The officer nodded. “That’s well done, then.” And he ran off, back toward the thick of the melee.

The soldier swaggered toward Dar; grinning and twirling his stick. “Chalk up one more for the good guys, eh?”

“And another ten BTUs in your account!” Dar called back. “Well done, soldier!”

The soldier grinned, waved, and charged back into the thick of the chaos.

“Ten credits?” Sam gasped, blanching. “You don’t mean your General pays a bounty?”

“No, of course not. I mean, it’s not the General who let himself get chalked up, is it? It’s the Wolman who pays.”

“What?”

“Sure. After the battle’s over; the officers’ll transfer ten credits from that Wolman’s account to the soldier’s. I mean, there’s got to be some risk involved.”

“Right,” she agreed. “Sure. Risk.” Her eyes had glazed. “I, uh, notice the, uh, ‘casualties’ seem to be having a pretty good time over there.”

“Mm?” Dar looked up at the group over to the east. Wolmen and soldiers were chatting amicably over tankards. A couple of privates and three warriors wove in and out through the crowd with trays of bottles and cups, dispensing cheer and collecting credits.

He turned back to Sam. “Why not? Gotta fill in the ‘dead’ time somehow.”

“Sure,” she agreed. “Why not?”

Suddenly whistles shrilled all over the field, and the frantic runners slowed to a walk, lowering their chalk sticks. Most of them looked pretty disgusted. “Cease!” bellowed one officer. “Study war no more!” echoed a Wolman chief. The combatants began to circulate; a hum of conversation swelled.

“Continual warfare,” Sam muttered.

Dar leaned back against the wall and began whistling through his teeth.

Two resplendent figures stepped in from the west—an I.D.E. colonel in full dress uniform and a Wolman in a brightly patterned cloak and elaborate headdress.

“The top-ranking officers,” Dar explained. “Also the peace commission.”

“Referees?” Sam muttered.

“Come again?”

“I’d rather not.”

Each officer singled out those of his own men who had chalk marks on them, but who hadn’t retired to the sidelines. Most of them seemed genuinely surprised to find they’d been marked. A few seemed chagrined.

The officers herded them over to join the beerfest, then barked out orders, and the “casualties” lined up according to side in two ragged lines, still slurping beer. The officers walked down each other’s line, counting heads, then switched and counted their own lines. Then they met and discussed the situation.

“Me count-um twenty-nine of mine, and thirty-two of yours.”

“Came to the same count, old chap. Wouldn’t debate it a bit.”

The Wolman grinned, extending a palm. “Pay up.”

The I.D.E. colonel sighed, pulled out a pad, and scribbled a voucher. The Wolman pocketed it, grinning.

A lieutenant and a minor Wolman stepped up from the battlefield, each holding out a sheaf of papers. The two chief officers took them and shuffled through, muttering to each other, comparing claims.

“That’s the lot.” The colonel tapped his sheaf into order, squaring it off. “Only this one discrepancy, on top here.”

The Wolman nodded. “Me got same.”

“Well, let’s check it, then … O’Schwarzkopf!”

“Sir!” A corporal stepped forward and came to attention with a click of his heels, managing not to spill his tankard in the process.

“This warrior, um, ‘Xlitplox,’ claims he chalked you. Valid?”

“Valid, sir.”

“Xlitplox!” the Wolman officer barked.

“Me here.” The Wolman stepped forward, sipping.

“O’Schwarzkopf claim-um him chalk you.”

“He do-um.” Xlitplox nodded.

“Could be collusion,” the colonel noted.

The Wolman shrugged. “What matter? Cancel-um out, anyhow. Null score.”

The colonel nodded. “They want to trade tenners, that’s their business. Well!” He tapped the sheaf and saluted the Wolman with them. “I’ll have these to the bank directly.”

“Me go-um, too.” The Wolman caught two tankards from a passing tray and dropped a chit on it. “Drink?”

“Don’t mind if I do.” The colonel accepted a tankard and lifted it. “To the revolution!”

“Was hael!” The Wolman clinked mugs with him. “We rise-um up; we break-um and bury-um corrupt colonial government!”

“And we’ll destroy the Wolman tyranny! … Your health.”

“Yours,” the Wolman agreed, and they drank.

“What is this?” Sam rounded on Dar “Who’s rebelling against whom?”

“Depends on whom you ask. Makes sense, doesn’t it? I mean, each side claims to be the rightful government of the whole planet—so each side also thinks it’s staging a revolution.”

“That’s asinine! Anybody can see the Wolmen are the rightful owners of the planet.”

“Why? They didn’t evolve here, any more than we soldiers did.”

“How do you know?” Sam sneered.

“Because I read a history book. The Wolmen are the descendants of the ‘Tonies,’ the last big opposition culture, a hundred years ago. You should hear their music—twenty-four tones. They came out here to get away from technology.”

Sam shuddered, then shook her head. “That doesn’t really change anything. They were here first.”

“Sure, but they think we came in and took over. After all, we’ve got a government. Their idea of politics is everybody sitting around in a circle and arguing until they can all agree on something.”

“Sounds heavenly,” Sam murmured, eyes losing focus.

“Maybe, but that still leaves General Shacklar as the only government strong enough to rebel against—at least, the way the Wolmen see it. And we think they’re trying to tell us what to do—so we’re revolting, too.”

“No argument there.” Sam shrugged. “I suppose I shouldn’t gripe. As ‘continual wars’ go, this is pretty healthy.”

“Yeah, especially when you think of what it was like my first two years here.”

“What? Real war—with sticks and stones?”

Dar frowned. “When you tie the stone to the end of the stick, it can kill a man—and it did. I saw a lot of soldiers lying on the ground with their heads bashed in and their blood soaking into the weeds. I saw more with stone-tipped spears and arrows in them. Our casualties were very messy.”

“So what are dead Wolmen like—pretty?”

“I was beginning to think so, back then.” Dar grimaced at the memory. “But dead Wolmen were almost antiseptic—just a neat little hole drilled into ‘em. Not even any blood—laser wounds are cauterized.”

Sam caught at his arm, looking queasy. “All right! That’s … enough!”

Dar stared down at her. “Sorry. Didn’t think I’d been all that vivid.”

“I’ve got a good imagination.” Sam pushed against him, righting herself. “How old were you then?”

“Eighteen. Yeah, it made me sick too. Everybody was.”

“But they couldn’t figure out how to stop it?”

“Of course not. Then Shacklar was assigned the command.”

“What’d he do—talk it to death?”

Dar frowned. “How’d you guess?”

“I was kidding. You can’t stop a war by talking!”

Dar shrugged. “Maybe he waved a magic wand. All I knew was that he had the Wolmen talking instead of fighting. How, I don’t know—but he finally managed to get them to sign a treaty agreeing to this style of war.”

“Would it surprise you to learn the man’s just human?”

“It’s hard to remember sometimes,” Dar admitted. “As far as I’m concerned, Shacklar can do no wrong.”

“I take it all the rest of the soldiers feel the same way.”

Dar nodded. “Make snide comments about the Secretary of the Navy, if you want. Sneer at the General Secretary of the whole Interstellar Dominion Electorates. Maybe even joke about God. But don’t you dare say a word against General Shacklar!”

Sam put on a nasty smile and started to say something. Then she thought better of it, her mouth still open. After a second, she closed it. “I suppose a person could really get into trouble that way here.”

“What size trouble would you like? Standard measurements here are two feet wide, six feet long, and six feet down.”

“No man should have that kind of power!”

“Power? He doesn’t even give orders! He just asks …”

“Yeah, and you soldiers fall all over each other trying to see who can obey first! That’s obscene!”

Dar bridled. “Soldiers are supposed to be obscene.”

“Sexual stereotype,” Sam snapped. “It’s absurd.”

“Okay—so soldiers should be obscene and not absurd.” Dar gave her a wicked grin. “But wouldn’t you feel that way about a man who’d saved your life, not to mention your face?”

“My face doesn’t need saving, thank you!”

Dar decided to keep his opinions to himself. “Look—there’re only two ways to stop a war. Somebody can win—and that wasn’t happening here. Or you can find some way to save face on both sides. Shacklar did.”

“I’ll take your word for it.” Sam looked more convinced than she sounded. “The main point is, he’s found a way to let off the steam that comes from the collision of two cultures.”

Dar nodded. “His way also sublimates all sorts of drives very nicely.”

Sam looked up, frowning. “Yes, it would. But you can’t claim he planned it that way.”

“Sure I can. Didn’t you know? Shacklar’s a psychiatrist.”

“Psychiatrist?”

“Sure. By accident, the Navy assigned a man with the right background to be warden for a prison planet. I mean, any soldier who’s sent here probably has a mental problem of some sort.”

“And if he doesn’t, half an hour here should do the trick. But Shacklar’s a masochist!”

“Who else could survive in a job like this?” Dar looked around, surveying the “battlefield.”

“Things have quieted down enough. Let’s go.”

He shouldered the rope and trudged off across the plain. Sam stayed a moment, then followed, brooding.

She caught up with him. “I hate to admit it—but you’ve really scrambled my brains.”

Dar looked up, surprised. “No offense taken.”

“None intended. In fact, it was more like a confession.”

“Oh—a compliment. You had us pegged wrong, huh?”

“Thanks for not rubbing it in,” she groused. “And don’t start crowing too soon. I’m not saying I was wrong, yet. But, well, let’s say it’s not what I expected.”

“What did you expect?”

“The dregs of society,” she snapped.

“Well, we are now. I mean, that’s just a matter of definition, isn’t it? If you’re in prison, you’re the lowest form of social life.”

“But people are supposed to go to prison because they’re the lowest of the low!”

“ ‘Supposed to,’ maybe. Might even have been that way, once. But now? You can get sent here just for being in the wrong place at the wrong time.”

“Isn’t that stretching it?”

“No.” Dar’s mouth tightened at the corners. “Believe me, it’s not.”

“Convince me.”

“Look,” Dar said evenly, “on a prison planet, one thing you don’t do is ask anybody why he’s there.”

“I figured that much.” Sam gazed at him, very intently. “I’m asking.”

Dar’s face went blank, and his jaw tightened. After a few seconds, he took a deep breath. “Okay. Not me, let’s say—just someone I know. All right?”

“Anything you say,” Sam murmured.

Dar marched along in silence for a few minutes. Then he said, “Call him George.”

Sam nodded.

“George was a nice young kid. You know, good parents, lived in a nice small town with good schools, never got into any real trouble. But he got bored with school, and dropped out.”

“And got drafted?”

“No—the young idiot enlisted. And, since he had absolutely no training or experience in cargo handling, bookkeeping, or stocking, of course he was assigned to the Quartermaster’s Corps.”

“Which is where you met him?”

“You could say that. Anyway, they made him a cargo handler—taught him how to pilot a small space-tug—and he had a whale of a time, jockeying cargo off shuttles and onto starships. Figured he was a hotshot Navy pilot, all that stuff.”

“I thought he was in the Army.”

“Even the Army has to run a few ships. Anyway, it was a great job, but after a while it got boring.”

Sam closed her eyes. “He wanted a change.”

“Right,” Dar said sourly. “So he applied for promotion—and they made him into a stock clerk. He began to go crazy, just walking around all day, making sure the robots had put the right items into the right boxes and the right boxes into the right bins—especially since they rarely took anything out of those bins, or put in anything new. And he heard the stories in the mess about how even generals have to be very nice to the sergeants in charge of the routing computers, or the goods they order will ‘accidently’ get shipped halfway across the Sphere.”

“Sounds important.”

“It does, when you’re a teenager. So George decided he was going to get promoted again.”

“Well, that’s the way it’s supposed to be,” Sam said quietly. “The young man’s supposed to find himself in the Army, and study and work hard to make something better out of himself.”

“Sure,” Dar said sourly. “Well, George did. He knew a little about data processing, of course, but just the basics they make you learn in school. He’d dropped out before he’d learned anything really useful—so now he learned it. You know, night classes, studying three hours a day, the rest of it. And it worked—he passed the test, and made corporal.”

“Everything’s fine so far. They assign him a computer terminal?”

Dar nodded. “And for a few months, he just did what he was told, punched in the numbers he was given. By the end of the first month, he knew the computer codes for every single Army platoon and every single Navy ship by heart. By the end of the second month, he knew all their standard locations.”

“And by the end of the third month, he’d begun to realize this wasn’t much better than stocking shelves?”

“You got it. Then, one day, the sergeant handed him some numbers that didn’t make sense. He’d been on the job long enough to recognize them—the goods number was for a giant heating system, and the destination code was for Betelgeuse Gamma.”

“Betelgeuse Gamma?” Sam frowned. “I think that one went across my desk once. Isn’t it a jungle world?”

Dar nodded. “That’s what George thought. He’d seen such things as insecticides and dehumidifiers shipped out there. This heating unit didn’t seem to make sense. So he ran to his sergeant and reported it, just bursting with pride, figuring he’d get a promotion out of catching such an expensive mistake.”

“And the sergeant told him to shut up and do what he was told?”

“You have worked in a bureaucracy, haven’t you? Yeah, ‘Ours not to question why, ours but to do and fry.’ That sort of thing. But. George had a moral sense! And he remembered the scuttlebutt about why even generals have to treat supply sergeants nicely.”

“Just offhand, I’d say his sergeant was no exception.”

“Kind of looked that way, didn’t it? So George did the right thing.”

“He reported the sergeant?”

“He wasn’t that stupid. After all, it was just a set of numbers. Who could prove when they’d gotten into the computer, or where from? No, nobody could’ve proven anything against the sergeant, but he could have made George’s next few years miserable. Reporting him wouldn’t do any good, so George did the next best thing. He changed the goods number to one for a giant air-cooling system.”

Sam’s eyes widened. “Oh, no!”

“Ah,” Dar said bitterly, “I see you’ve been caught in the rules, too. But George was an innocent—he only knew the rules for computers, and assumed the rules for people would be just as logical.”

Sam shook her head. “The poor kid. What happened to him?”

“Nothing, for a while,” Dar sighed, “and there never were any complaints from Betelgeuse Gamma.”

“But after a while, his sergeant started getting nasty?”

“No, and that should’ve tipped him off. But as I said, he didn’t know the people-rules. He couldn’t stand the suspense of waiting. So, after a while, he put a query through the system, to find out what happened to that shipment.”

Sam squeezed her eyes shut. “Oh, no!”

“Oh, yes. Not quite as good as waving a signal flag to attract attention to the situation, but almost. And everything was hunky-dory on Betelgeuse Gamma; the CO there had even sent in a recommendation for a commendation for the lieutenant who had overseen the processing of the order, because that air-cooling plant had already saved several hundred lives in his base hospital. And before the day was out, the sergeant called George into his office.”

“A little angry?”

“He was furious. Seems the lieutenant had raked him over the coals because the wrong order number had been filed—and against the sergeant’s direct order. George tried to explain, but all that mattered to the sergeant was that he was in trouble. He told George that he was remanding him to the lieutenant’s attention for disciplinary action.”

“So it was the lieutenant who’d been out to get the general on Betelgeuse Gamma!”

“Or somebody in his command. Who knows? Maybe that CO had a lieutenant who’d said something nasty to George’s lieutenant, back at the Academy. One way or another, the lieutenant didn’t have to press charges, or initiate anything—all he had to do was act on his sergeant’s recommendation. He demoted George to private and requested his transfer to Eta Cassiopeia.”

“Could be worse, I suppose,” Sam mused.

“Well, George heard there was a war going on there at the moment—but that wasn’t the real problem. This lieutenant had charge of a computer section, remember.”

“Of course—what’s wrong with me? His traveling orders came out with a different destination on ‘em.” Sam looked up. “Not Wolmar! Not here!”

“Oh, yes,” Dar said, with a saccharine smile. “Here. And, the first time he showed his orders to an officer, the officer assumed that, if he was en route to Wolmar, he must be a convicted criminal, and clapped him in irons.”

“How neat,” Sam murmured, gazing into the distance. “Off to prison, without taking a chance of being exposed during a court-martial… Your lieutenant was a brainy man.”

“Not really—he just knew the system. So there George was, on his way here and nothing he could do about it.”

“Couldn’t he file a complaint?” Sam bit her lip. “No, of course not. What’s wrong with me?”

“Right.” Dar nodded. “He was in the brig. Besides, the complaint would’ve been filed into the computer, and the lieutenant knew computers. And who would let a convicted felon near a computer terminal?”

“But wouldn’t the ship’s commanding officer listen to him?”

“Why? Every criminal says he didn’t do it. And, of course, once it’s on your record that you’ve been sent to a prison planet, you’re automatically a felon for the rest of your life.”

Sam nodded slowly. “The perfect revenge. He made George hurt, he got him out of the way, and he made sure George’d never be able to get back at him.” She looked up at Dar. “Or do you people get to go home when your sentence is up?”

Dar shook his head. “No such thing as a sentence ending here. They don’t send you to Wolmar unless it’s for life.” He stopped and pointed. “This is where a life ends.”

Sam turned to look.

They stood in the middle of a broad, flat plain. A few hundred yards away stood a plastrete blockhouse, with long, high fences running out from it like the sides of a funnel. The rest of the plain was scorched, barren earth, pocked with huge blackened craters, glossy and glinting.

“The spaceport.” Sam nodded. “Yes, I’ve been here.”

“Great first sight of the place, isn’t it? They chose the most desolate spot on the whole planet for the new convict’s first sight of his future home. Here’s where George’s life ended.”

“And a new one began?”

Dar shook his head. “For two years he wondered if he was in hell, with Wolmen throwing nasty, pointed things at him during the day and guards beating him up if he hiccupped during the night.” He nodded toward the blockhouse again. “That was the worst thing about this place, the first time I looked at it—guards, all over. Everywhere. They were all built like gorillas, too, and they all loved pain—other people’s pain.”

“Yes, I was wondering about that. Where are they?”

“Gone, to wherever the computers reassigned them. When Shacklar came, the guards went.”

“What?” Sam whirled, staring up at him. “That’s impossible!”

“Oh, I dunno.” Dar looked around. “See any guards?”

“Well, no, but—one uniform looks just like any other to me.”

“We didn’t wear uniforms when I came here. First thing they did was give me a set of gray coveralls and tell me to get into ‘em.” His mouth tightened at the memory. Then he shook his head and forced a smile. “But that was eleven years ago. Now we wear the uniforms, and the guards are gone.”

“Why?”

Dar shrugged. “Shacklar thought uniforms’d be good for morale. He was right, too.”

“No, no! I mean, why no guards?”

“Wrong question. Look at it Shacklar’s way—why have any guards?”

Sam frowned, thinking it over. “To keep the prisoners from escaping.”

“Where to?” Dar spread his hand toward the whole vast plain. “The Wolman villages? We were already fighting them—had been, ever since this, uh, ‘colony’ started.”

“No, no! Off-planet! Where the rest of society is! Your victims! The rest of the universe!”

“So how do you escape from a planet?”

Sam opened her mouth—and hesitated.

“If you can come up with an idea, I’ll be delighted to listen.” Dar’s eyes glinted.

Sam shut her mouth with an angry snap. “Get going! All you have to do is get going fast enough! Escape velocity!”

“Great idea! How do I do it? Run real fast? Flap my arms?”

“Spare me the sarcasm! You hijack a spaceship, of course!”

“We have thought of it,” Dar mused. “Of course, there’s only one spaceship per month. You came in on it, so you know: Where does it go?”

“Well, it’s a starship, so it can’t land. It just goes into orbit. Around the … uh …”

“Moon.” Dar nodded. “And a shuttle brings you down to the moon’s surface, and you have to go into the terminal there through a boarding tube, because you don’t have a spacesuit. And there’re hidden video pickups in the shuttle, and hidden video pickups all through the terminal, so the starship’s crew can make sure there aren’t any escaping prisoners waiting to try to take over the shuttle.”

“Hidden video pickups? What makes you think that?”

“Shacklar. He told us about them, just before he sent the guards home.”

“Oh.” Sam chewed it over. “What would they do if they did see some prisoners waiting to take over the shuttle?”

“Bleed off the air and turn off the heaters. It’s a vacuum up there, you know. And the whole terminal’s remote-controlled, by the starship; there isn’t even a station master you can clobber and steal keys from.”

Sam shuddered.

“Don’t worry,” Dar soothed. “We couldn’t get up there, anyway.”

Sam looked up. “Why not?”

Dar spread his hands. “How did you get down here?”

“The base sent up a ferry to bring us down.”

Dar nodded. “Didn’t you wonder why it wasn’t there waiting for you when you arrived?”

“I did think it was rather inconsiderate,” Sam said slowly, “but spaceline travel isn’t what it used to be.”

“Decadent,” Dar agreed. “Did you notice when the ferry did come up?”

“Now that you mention it … after the starship left.”

Dar nodded. “Just before it blasted out of orbit, the starship sent down a pulse that unlocked the ferry’s engines—for twenty-four hours.”

“That’s long enough. If you really had any gumption, you could take over the ferry after it lands, go back up to the moon, and wait a few months for the next starship.”

“Great! We could bring sandwiches, and have a picnic—a lot of sandwiches; they don’t store any rations up there, so we’d need a few months’ worth. They’d get a little stale, you know? Besides, the ferry’s engines automatically relock after one round trip. But the real problem is air.”

“I could breathe in that terminal.”

“You wouldn’t have if you’d stayed around for a day. The starship brings in a twenty-four-hour air supply when it comes. They send an advance crew to come in, turn it on, and wait for pressure before they call down the shuttle.” Dar gazed up at the sky. “No, I don’t think I’d like waiting for a ship up there, for a month. Breathing CO2 gets to you, after a while.”

“It’s a gas,” Sam said in a dry icy tone. “I take it Shacklar set up this darling little system when he came?”

“No, it was always here. I wouldn’t be surprised if it were standard for prison planets. So, by the time Shacklar’d managed to reach the surface of Wolmar, he knew there wasn’t really any need for guards.”

“Except to keep you from killing each other! How many convicts were here for cold-blooded murder?”

“Not too many, really; most of the murderers were hot-blooded.” He shuddered at the memory. “Very. But there were a handful of reptiles—and three of them were power-hungry, too.”

“Why?” Sam looked up, frowning. “I mean, how much power could they get? Nothing that counts, if they couldn’t leave the planet.”

“If you’ll pardon my saying so, that’s a very provincial view. I mean, there’s a whole planet here.”

“But no money.”

“Well, not real money, no. But I didn’t say they were out to get rich; I said they were out for power.”

“Power over a mud puddle? A handful of soldiers? What good is that?”

“Thanks for rubbing my nose in it,” Dar snapped.

“Oh! I’m sorry.” Sam’s eyes widened hugely. “I just turn off other people’s feelings, sometimes. I get carried away with what I’m saying.”

“Don’t we all?” Dar smiled bleakly, sawing his temper back. “I suppose that’s how the lust for power begins.”

“How—by ignoring other people’s feelings?”

Dar nodded. “Only worrying about how you feel. I suppose if you’re the boss, you feel safer, and that’s all that really matters.”

“Not the bosses I’ve met. They’re always worrying about who’s going to try to kick them out and take over—and I’m just talking about bureaucrats!” She looked up at Dar. “Would you believe it—some of them actually hire bodyguards?”

“Sure, I’d believe it! After living on a prison planet without guards.”

“Oh. Your fellow prisoners were worse than the gorillas?”

“Much worse,” Dar confirmed. “I mean, with the guards at least you knew who to watch out for—they wore uniforms. But with your friendly fellow prisoners, you never knew from one moment to the next who was going to try to slip a knife between your ribs.”

“They let you have knives?”

Dar shrugged impatiently. “The Wolmen could chip flints; so could we. Who was going to stop us, with the guards gone? No, they loaded onto the ferry and lifted off; Shacklar stepped into Government House and locked himself in behind concrete and steel with triple locks and arm-thick bolts … and the monsters came out of the woodwork. Anybody who had a grudge hunted down his favorite enemy, and started slicing. Or got sliced up himself.”

“Immoral!” Sam muttered. “How could he bring himself to do such a thing!”

Dar shrugged. “Had to be hard, I guess. Lord knows we had enough hard cases walking around. When they saw blood flowing, they started banding together to guard each other’s backs. And the first thing you knew, there were little gangs roaming around, looking for people to rough up and valuables to steal.”

Sam snorted. “What kind of valuables could you have had?”

“Food would do, at that point. Distribution had broken down. Why should the work-gangs work, without the guards to make them? Finally, we mobbed the warehouse and broke in—and ruined more food than we ate.” He shuddered at the memory. “They started knife fights over ham hocks! That was about when I started looking for a hole to crawl into.”

“Your general has no more ethics than a shark!” Sam blazed. “How could he just sit there and let it happen?”

“I expect he had a pretty good idea about how it would all come out.”

“How could he? With chaos like that, it was completely unpredictable!”

“Well, not really…”

“What’re you talking about? You could’ve all killed each other off!”

“That’s predictable, isn’t it? But there wasn’t too much chance of it, I guess. There were too many of us—half a million. That’s a full society; and anarchy’s an unstable condition. When the little gangs began to realize they couldn’t be sure of beating the next little gang they were trying to steal from, they made a truce instead, and merged into a bigger gang that could be sure of winning a fight, because it was the biggest gang around.”

“So other little gangs had to band together into bigger gangs too.” Sam nodded. “And that meant the bigger gangs had to merge into small armies.”

“Right. Only most of us didn’t realize all that; we just knew there were three big gangs fighting it out, all of a sudden.”

“The power-hungry boys you told me about?”

Dar nodded. “And they were pretty evenly balanced, too. So their battles didn’t really decide anything; they just killed off sixty men. Which meant you had to stay way clear of any of ‘em, or they’d draft you as a replacement.”

“So two of them made a truce and ganged up on the third?”

“No, the Wolmen ganged up on all of us, first.”

“Oh.” Sam looked surprised, then nodded slowly. “Makes sense, of course. I mean, why should they just sit back and wait for you to get yourselves organized?”

“Right. It made a lot more sense to hit us while we were still disorganized. And we’d stopped keeping sentries on the wall, and the Wolmen knew enough to hit us at night.”

Sam shuddered. “Why weren’t you all killed in your beds?”

“Because the Big Three did have sentries, to make sure none of the others tried a night attack. So all of a sudden, the sirens were howling, and everybody was running around yelling—and military conditioning took over.”

“Military conditioning?” Sam frowned. “I thought you were convicts!”

“Yeah, but we were still soldiers. What’d you think—the Army provided a few battalions to fight off the Wolmen for us? We had to do our own fighting, with our own sergeants and lieutenants. The guards just stood back and made sure we didn’t try to get any big ideas … and handled the laser cannons.”

“But how could they let you have weapons?”

Dar shrugged. “Bows and arrows, tops. That gave us a fair chance against the Wolmen. So when the sirens shrieked, we just automatically ran for the armory and grabbed our bows, and jumped any Wolman who got in our way. Then, when we had our weapons, we just naturally yelled, ‘What do we do, Sarge?’ I mean, he was there getting his weapons, too—if he was still alive.”

“And most of them were?”

“What can I tell you? Rank has its privileges. Yeah, most of them were there, and they told us where to go.”

“Sergeants usually do, I understand.”

“Well, yes. But in this case, they just took us out to chop up anything that didn’t wear a uniform—and look for a lieutenant to ask orders from. We pulled together into companies—and the lieutenants were already squawking into their wrist coms, demanding that Shacklar tell them what to do.”

“Why would they do …?” Sam broke off, her eyes widening. “I just realized something: soldiers are basically bureaucrats. Nobody wants to take a chance on getting blamed.”

“It is kind of drilled into you,” Dar admitted. “And as I said, when the Wolmen came over the wall, habit took over. It did for Shacklar, too, I guess. He started telling them what to do.”

“Habit, my great toe! He’d been waiting for a chance like that—counting on it!”

“Looking for me to disagree with you? Anyway, he had the viewscreens, and he knew the tactics; so he started giving orders.” Dar shook his head in disbelief. “If you can call them orders! ‘Lieutenant Walker, there’s a band of Wolmen breaking through over on the left; I really think you should run over and arrange a little surprise for them.’ ‘Lieutenant Able, Sergeant Dorter’s squad is outnumbered two to one over on your company’s right; would you send your reserves over to join him, please?’ ”

“Come off it! No general talks to his subordinates that way!”

Dar held up a palm. “So help me, he did it! I overheard Lieutenant Walker’s communicator.”

“You mean you were in that battle?”

“I had a choice?”

“But I thought you tried to find a hole to crawl into!”

“Sure. I didn’t say I succeeded, did I?”

Sam turned away, glowering. “I still don’t believe it. Why should he be so polite?”

“We figured it out later. In effect, he was telling us it was our war, and it was up to us to fight it; but he was willing to give us advice, if we wanted it.”

“Good advice, I take it?”

“Oh, very good! We had the Wolmen pushed back against the wall in an hour. Then Shacklar told the lieutenants to pull back and give them a chance to get away. They all answered, basically, ‘The hell with that noise! We’ve got a chance to wipe out the bastards!’ ‘Indeed you do,’ Shacklar answered, ‘and they all have brothers and cousins back home—six of them for every one of you. But if you do try to exterminate them—well, you’ll manage it, but they’ll kill two of your men for every one of theirs.’ Well, the lieutenants allowed that he had a point, so they did what he said and pulled back; and the Wolmen, with great daring and ingenuity, managed to get back up over the wall and away.”

“Then he told you to break out the laser cannon?”

“No, he’d sent the cannons home with the guards. Good thing, too; I’d hate to think what those three power-mongers would’ve done with them. But we did have hand-blasters, in the armories. Each of the power-mongers had managed to seize an armory as a power base as soon as he’d recruited a gang. They’d opened the doors and issued sidearms as soon as the sirens screamed. They weren’t much good for the close fighting inside the wall; but, once the Wolmen were over the top and running, we got up on the parapet and started shooting after them, until the lieutenants yelled at us to stop wasting our charges. The Wolmen were running, and they didn’t stop until morning.”

“A victory,” Sam said dryly.

“A bigger one than you think—because as soon as the shooting was over the three would-be warlords showed up with their henchmen, bawling, ‘All right, it’s all over! Turn in your guns! Go home!’ ”

“They what!”

“Well, sure.” Dar shrugged. “After all, they’d opened up the armories for us, hadn’t they? Shouldn’t we give them their guns back now? I mean, you’ve got to see it from their viewpoint.”

“I hope you didn’t!”

“Of course we didn’t. We just turned around grinning, and pointed the guns at them. But we didn’t say anything; we let the lieutenants do the talking.”

“What talking?”

“It depended. The nice ones said, ‘Hands up.’ The rest of them just said, ‘Fire!’ And we did.”

Sam formed a silent O with her lips.

“It was quick and merciful,” Dar pointed out. “More than they had a right to, really.”

“What did you do without them? I mean, they had provided some sort of social order.”

“I see you favor loose definitions. But while the ashes cooled, the lieutenants got together and did some talking.”

“They elected a leader?”

“Yeah, they could all agree that they needed to. But they weren’t so unanimous about who. There were four main candidates, and they wrangled and haggled, but nobody could agree on anything—I mean, not even enough to call for a vote.”

“How long did they keep that up?”

“Long enough for it to get pretty tense, and the boys on the battlements were getting kind of edgy, eyeing each other and wondering if we were going to be ordered to start burning each other pretty soon.”

“You wouldn’t really have done it!”

“I dunno. That military conditioning runs pretty deep. You don’t know what you’ll do when you hear your lieutenant call, ‘Fire!’ ”

Sam shuddered. “What are you—animals?”

“I understand the philosophers are still debating that one. My favorite is, ‘Man is the animal who laughs.’ Fortunately, Lieutenant Mandring thought the same way.”

“Who’s Lieutenant Mandring?”

“The one with the sense of humor. He nominated General Shacklar.”

Sam whirled, the picture of fury. Then she developed a sudden faraway look. “You know …”

Dar pointed a finger at her. “That’s just about the way all the other lieutenants reacted. They started to yell—then they realized he meant it for a joke. After they’d finished rolling around on the ground and had it throttled down to a chuckle, they started eyeing each other, and it got awfully quiet.”

“But Shacklar didn’t even try to talk them into it!”

“He didn’t have to; he’d given them a taste of do-it-yourself government. So they were ready to consider a change of diet—but nobody wanted to be the first one to say it. So Lieutenant Griffin had to take it—he’s the one with the talent for saving other people’s faces. Too bad he can’t do anything about his own…”

“What happened!”

“Oh! Yes … well, all he said was, ‘Why don’t we ask him what he thinks?’ And after they got done laughing again, Lieutenant Able said, ‘It’d be good for a laugh.’ And Lieutenant Walker said, ‘Sure. I mean, we don’t have to do what he says, you know.’ Well, they could all agree on that, of course, so they put Lieutenant Walker up to it, he having spoken last, and he called the General on his wrist com, explained the situation, and asked what he’d do in their place. He said he was willing to serve, but really thought they ought to elect one of their own number.”

Sam smiled. “How nice of him! What’d they do back at Square One?”

“They asked the comedian for a suggestion. He said they ought to call out each lieutenant’s name and have everybody who had confidence in him raise a hand.”

“Who won?”

“Everybody; they all pulled, ‘No confidence.’ So Lieutenant Mandring called for a vote on General Shacklar.”

“How long was the pause?”

“Long enough for everybody to realize they were getting hungry. But after a while they started raising hands, and three hundred sixty out of four hundred went up.”

“This, for the man who had to hide in a fortress? What changed their minds?”

“The chaos, mostly—especially since he’d just done a good job directing them in battle. Soldiers value that kind of thing. So they called Shacklar and told him he was elected.”

“I take it he was glad to hear it.”

“Hard to say; he just heaved a sigh and asked them to form a parliament before they went to lunch and to start thinking about a constitution while they ate.”

“Constitution! In a prison?”

“Why not? I mean, they’d just elected him, hadn’t they?”

Sam developed a faraway look again. “I suppose…”

“So did they. That was the turning point, you see—when we started thinking of ourselves as a colony, not a prison. When we wrote the constitution, we didn’t call Shacklar ‘warden’—we named him ‘governor.’ ”

“Generous of you,” Sam smirked, “considering Terra had done it already.”

“Yeah, but we hadn’t. And once he had the consent of the populace, he could govern without guards.”

“That … makes … a weird kind of sense.”

“Doesn’t it? Only when you can make a whole planet into a prison, of course—and there’s no way out. But that’s the way it is here. So he could send the guards home, and let us fight it out for ourselves.”

“Which made you realize he was better than the natural product.”

“It did have that advantage. And, once his position was consolidated, he could start proposing reforms to the Council.”

“Council?”

“The legislative body. The Wolmen are agitating for representation, now. But that’s okay—we traders are angling for a rep at their moots. Anyway, Shacklar talked the Council into instituting pay.”

“Oh, that certainly must have taken a lot of convincing!”

“It did, as it happens; a fair number of them were Communists. But pay it was—in scrip; worthless off-planet, I’m sure, but it buys a lot here—a BTU for a neat bunk, two BTUs for a clean yard, and so forth.”

“Great! Where could they spend it?”

“Oh, the General talked Cholly into coming in and setting up shop, and a few of the con … uh, colonists, decided he had a good thing going, and …”

“Pretty soon, the place was lousy with capitalists.”

“Just the bare necessities—a general store, a fix-it shop, and three taverns.”

“That ‘general store’ looks more like a shopping complex.”

“Just a matter of scale. Anyway, that created a driving hunger for BTUs and that meant soldiers started spiffing up, and …”

“Higher morale, all over,” Sam muttered. “Because they can improve their lot.”

“Right. Then Cholly started paying top dollar for pipe-leaf traders, and …”

“A drug baron!”

“Suppose you could call him that. But it turned out there was a market for it—the drug’s very low-bulk after it’s processed, you see; and it doesn’t provide euphoria or kill pain, but it does retard the aging process. So Universal Pharmaceuticals was interested, and Interstellar Geriatrics, and …”

“I get the picture. Top money.”

“But it costs a lot, too—especially at first, when it was a little on the hazardous side. But Cholly was bringing in trade goods that made glass beads just sharp-cornered gravel, so once we managed to get trade started, it mushroomed.”

“And all of a sudden, the Wolmen weren’t quite so hostile any more.” Sam nodded.

“Aw, you peeked.” Dar scuffed at the turf with his boot-toe. “And from there, of course, it was just a little fast talking to get them to agree to the chalk-fights.”

“So trade is growing, and morale is growing, and you’re taking the first steps toward a unified society, and everybody feels as though they’ve got some opportunity, and …” Sam broke off, shaking her head, dazzled. “I can’t believe it! The central planets are mired in malaise and self-pity, and out here in the marches, you’ve managed to build a growing, maybe even hopeful, society! Back on Terra, everybody’s living in walking despair because nobody feels they can make things better.”

“What?” Dar was shocked. “But they’ve got everything! They’ve …”

“Got nothing,” Sam sneered. “On Terra, you’ll die doing the job your father did, and everybody knows it. You’ve got your rooms, your servos, and your rations. And that’s it.”

“But even beggars have whole houses—with furniture that makes anything here look like firewood! And they don’t have to do a lick of housework, with all those servos—their free time’s all free!”

“Free to do what—rot?”

“To do anything they want! I mean, even a rube like me has heard what’s included in those rations.”

Sam shrugged. “Sure, you can get drunk or stoned every night, and you can go out to a party or go to a show …”

Dar gave a whimpering sigh.

“… but actually do something? No chance! Unless you’re born into government—and even they can’t figure out anything worth doing.”

“But …” Dar flailed at the sky. “But there’s a thousand worlds out there to conquer!”

“Why bother?” She smiled bitterly. “We’ve done that already—and it hasn’t improved things back on Terra much.”

“Hasn’t improved!? But your poorest beggar lives like a medieval king!”

“Oh, does she?” Sam’s eyes glittered. “Where’re the servants, the musicians, the courtiers, the knights willing to fight for her smile?”

“Even a Terran reject has three or four servos! They’ll even turn on the audio for him—and there’s your musicians!”

“And the courtiers? The knights?” Sam shook her head. “What made a king royal was being able to command other people—and there’s no coin that’ll buy that!”

Dar could only stare.

Then he gave his head a quick shake, pushing out a whistle. “Boy! That’s sick!”

“Also decadent.” She smiled, with Pyrrhic triumph. “They’re moribund there. What I can’t figure out is how you folks avoid it.”

Dar shrugged. “Because we’re already at the bottom? I mean, once you’ve landed here, there’s no place to go but up!”

“There’s no place to go, period!” Sam’s eyes lit. “Maybe that’s it—because it’s out here in the marches! Out here, on the edge of civilization—because anything you’re going to do, you’re going to have to do for yourselves. Terra’s too far away to send help. And too far away to really be able to run you, either. By the time they can tell you not to do something, you’ve already been doing it for a year! And because …” She clamped her mouth shut.

“Because they really don’t care?” Dar grinned. “Because this place is a hole, and the only people Terra sends out here are the ones they want to forget about? I wouldn’t be surprised if they even wanted to get rid of Shacklar.”

“Of course; he was a threat to the ones with the real power. I mean, after all, he’s capable. He was bound to make waves. Which I’m about to do too.”

“I’m braced.” Dar tried to hide the smile.

“You still haven’t shown me how you’re not really fleecing the natives.”

“No, I haven’t, have I. But it does take showing. We start trading at sundown.”

2

That’s not the way to make a campfire,” Sam pointed out.

“What would you know about it?” Dar blithely heaped green sticks and leaves onto the flaming kindling. “You’re a city girl.”

“Who says?”

“You. You said you came from Terra, and it’s just one great big city.”

“It is, but we’ve kept a few parks, like the Rockies. I do know you’re supposed to use dry wood.”

“Entirely correct.” Dar smiled up at the roiling column of thick gray smoke turning gold in the sunset.

Sam sighed. “All right, so you’re trying to attract attention. What do we use for cooking?”

“Why bother?” Dar started foraging in the foodbag. “All we’ve got is cheese and crackers. And raisin wine, of course.”

Sam shuddered.

Darkness came down, and company came up—five Wolmen, each with a bale on his shoulder

“Ah! Company for cordials!” Dar rubbed his hands, then reached for the bottle and the glasses.

“Get ‘em drunk before they start bargaining, huh?” Sam snorted.

“That’d take more liquor than I can pack. But they count it friendly.” He stepped toward the arrivals, raising the bottle. “How!”

“You not know, me not tell you,” the first grunted, completing the formula. “Good seeing, Dar Mandra.”

“Good to see you, too, Hirschmeir.” Dar held out a handful of glasses; the Wolman took one, and so did each of his mates as they came up. Dar poured a round and lifted his glass. “To trade!”

“And profit,” Hirschmeir grunted. He drank half his glass. “Ah! Good swill after long hike. And hot day gathering pipeweed.”

“Yeah, I know,” Dar sympathized. “And it brings so little, too.”

“Five point three eight kwahers per ounce on Libra exchange,” a second Wolman said promptly.

Dar looked up in surprise. “That’s the fresh quote, right off today’s cargo ship. Where’d you get it?”

“You sell us nice wireless last month,” Hirschmeir reminded. “Tell Sergeant Walstock him run nice music service.”

“Sure will.” Dar pulled out a pad and scribbled a note.

“Little heavy on drums, though,” another Wolman said thoughtfully.

“Gotcha, Slotmeyer.” Dar scribbled again. “More booze, anybody?”

Five glasses jumped out. Dar whistled, walking around with the bottle, then picked up a bale. “Well. Let’s see what we’re talking about.” He plopped the bale onto the front of the grav-sled.

“Twenty-seven point three two kilograms,” the sled reported. “Ninety-seven percent Organum Translucem, with three percent grasses, leaf particles, and sundry detritus.”

“The sundry’s the good part.” Dar hefted the bale back off the sled and set it about halfway between himself and Hirschmeir.

“You sure that thing not living?” one of the Wolmen demanded.

“Sure. But it’s got a ghost in it.”

“No ghost in machine.” The Wolman shook his head emphatically.

Dar looked up sharply, then frowned. “Did I sell you folks that cubook series on the history of philosophy?”

“Last year,” Hirschmeir grunted. “Lousy bargain. Half of tribe quote-um Locke now.”

“Locke?” Dar scowled. “I would’ve thought Berkeley and Sartre would be more your speed.”

“Old concepts,” Slotmeyer snorted. “We learn at mothers’ knees. You forget—our ancestors opposition culture.”

“That does keep slipping my mind,” Dar confessed. “Well! How about two hundred thirty-four for the bale?”

Hirschmeir shook his head. “Too far below Libra quote. Your scrip only worth eighty percent of Libran BTU today.”

“I’m going to have to have a talk with Sergeant Walstock,” Dar growled. “Okay, so my price is twenty percent low. But you forget—we have to pay shipping charges to get this stuff to Libra.”

“And your boss Cholly also gotta pay you, and overhead,” Slotmeyer added. “We not forget anything, Dar Mandra.”

“Except that Cholly’s gotta show some profit, or he can’t stay in business,” Dar amended. “Okay, look—how about two seventy-five?”

“Tenth of a kwaher?” Hirschmeir scoffed. He bent over and picked up his bale. “Nice talking to you, Dar Mandra.”

“Okay, okay! Two eighty!”

“Two ninety,” Slotmeyer said promptly.

“Okay, two eighty-five.” Dar sighed, shaking his head. “The things I do for you guys! Well, it’s not your worry if I don’t come back next month. Hope you like the new man.”

“No worry. We tell Cholly we only deal with soft touch.” Hirschmeir grinned. “Okay. What you got to sell, Dar Mandra?”

“Oh, a little bit of this and a minor chunk of that.” Dar turned to the sled. “Wanna give me a hand?”

Together, all six of them manhandled a huge crate onto the ground. Dar popped the catches and opened the front and the left side. The Wolmen crowded around, fingering the merchandise and muttering in excitement.

“What this red stone?” Slotmeyer demanded, holding up a machined gem. “Ruby for laser?”

Dar nodded. “Synthetically grown, but it works better than the natural ones.”

“Here barrels,” another Wolman pointed out.

“Same model you sold us instruction manual for?” Hirschmeir weighed a power cell in his palm.

Dar nodded. “Double-X 14. Same as the Navy uses.”

“What this?” One of the Wolmen held up a bit of machined steel.

“Part of the template assembly for an automatic lathe,” Dar answered.

Slotmeyer frowned. “What is ‘lathe’?”

Dar grinned. “Instruction manual’s only twenty-five kwahers.”

“Twenty-five?” Hirschmeir bleated.

Dar’s grin widened.

Hirschmeir glowered at him, then grimaced and nodded. “You highway robber, Dar Mandra.”

“No, low-way,” Dar corrected. “Cholly tells me I’m not ready for the highway.”

“Him got high idea of low,” Hirschmeir grunted. “What prices on laser parts?”

Dar slid a printed slip out of his jacket pocket and handed it to Hirschmeir. “ ‘Scuse me while you study that; I’ll finish the weigh-in.” He turned away to start hoisting bales onto the sled’s scale as the Wolmen clustered around Hirschmeir, running through the price list and muttering darkly.