Chris Pierson

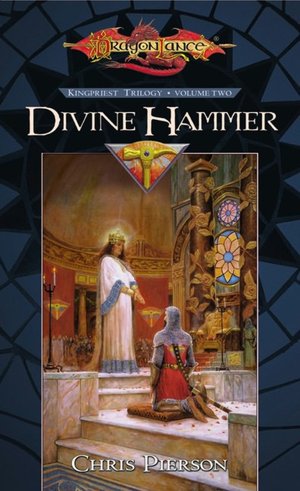

Divine Hammer

PROLOGUE

Tenthmonth, 935 I.A.

The folk of Krynn thought it was a moonless night. Silver Solinari, a slender crescent at this time of the month, set soon after sunset, and Lunitari, the red moon, would not rise until dawn. In their absence, the sky-clear this cool autumn eve, unmarred by clouds-seemed empty of all but stars.

It was not.

Most folk could not see the third moon. Unlike its bright sisters, Nuitari was black as a dragon’s heart, blending with the night. Only a few-astronomers and madmen, mostly-marked it as a hole in the sky, tracing it by the stars it blocked as it passed. Others, however, could see every crater and scar, even-though it reflected none of the sun’s light-its phase, and thus gauge its power.

A thousand years ago, dragons, monsters, and dark-hearted men had all but ruled the world, and Nuitari had shimmered with their power. That was the past, though. The dragons were gone, banished from the world, and the followers of the gods of light had hunted down those who served the shadows, beast and man alike. In all the world’s realms-crumbling Ergoth, proud Solamnia, wild Kharolis, the kingdoms of elves, dwarves, and kender-the disciples of evil were few, scattered, forced to hide if they wanted to survive.

The place of faintest shadows was the Holy Empire of Istar. The Kingpriest who ruled the empire, a man folk called Lightbringer, had commanded his people to destroy all evil in the name of the god Paladine. For more than a decade, pyres had burned beneath stakes, gibbets had groaned and creaked, and blood had caked thick on headsmen’s blocks and warriors’ swords.

Still, despite the purges, vestiges of darkness survived.

Monsters still skulked in the wildlands, and cults of evil gods worshiped in secret haunts. There were those who could not only see the black moon but could draw down its power to spin into sorcery. The Kingpriest detested these dark wizards, and so the mages who wore the Black Robes seldom ventured out into the open.

The black moon was strong tonight, not just full but close, large in the sky. Its power crackled in the crisp air, so charged that children the world over squirmed as they slept, in the throes of formless nightmares. In this night, dark sorcerers walked out in the open.

Andras crouched in the darkness, his breath coming short and quick. He was a tall man, slender and golden-haired, the sort who might have made maidens swoon had he wielded a blade or played the lute. No maidens pined for those whose tools were the staff and the scroll, though-or for those whose faces were half burnt away. The strange tightness of Andras’s ravaged flesh was a constant reminder of the sacrifices he had made to become a mage. The Test, which every wizard had to undergo in order to join the Order of High Sorcery, often left its mark. Barely a year ago, it had left the left side of his face ridged and glistening with scars as a warning against vanity. The warning had worked: not even the enchantresses who served Nuitari could look at him without wincing, so he had devoted himself all the more to the magic and his dark god.

“Boy,” rasped a voice in the gloom, “Get your head about you.”

Andras started out of his reverie, glancing to his left. Stooped beside him, small and bony beneath his ebon robes, was his master. Nusendran the Voiceless-the Test had ravaged his throat so badly he could only speak in a dry growl-was a powerful Black Robe and would one day serve on the Conclave that governed the High Sorcerers. His gray-bearded face was pinched with annoyance.

“It’s time,” Nusendran said. “Cast the spell as I taught you.”

A smile crept across Andras’s disfigured face. He had been waiting for this moment for half his twenty-four years, ever since his first lesson in magecraft. Until today; he had cast only minor spells, under his master’s supervision. Tonight, though, he would finally wield true magic. He felt the black moon’s power bathing him, hot and strong.

Eye of Night, he prayed, watch over me.

As his master watched, he delved into a small pouch at his belt and produced a wad of Yerasan gum. Rolling it into a ball, he reached up with his other hand and plucked out one of his eyelashes. He stuck this into the gum, tears running down his cheek, then squeezed it in his left hand. With his right he wove a complicated gesture through the air, fingers dancing as he chanted soft, spidery words.

“Ristak pur koivannon, sha pangit felori.”

The feel of magic recalled the bliss of loveplay, lost to him since the Test. His body went rigid, his nostrils flaring as the magic surged through him. A quiet groan slipped from his lips. The air around him shuddered, as it might on a summer’s day-then stilled again-and Andras vanished.

Nusendran hardly ever smiled, but now a proud grin split his wispy beard. “Well done, lad,” he said. “Keep it up, and one day you’ll make your mark on the world.”

He cast the invisibility spell as well, barely blinking as he plucked his eyelash, and spoke the incantation in half the time it had taken Andras. Then he was gone as well.

“Now,” Nusendran rasped, “let’s go.”

Together, they crept out of the shadows, beneath the black moon’s gaze.

The farm was like any in Ismin, the breadbasket of Istar. The family who owned it were wealthy landholders, overseeing several hundred workers who tended fields of barley and wheat, herds of cattle, and scattered orchards, olive groves, and vineyards. The villa, a sprawling, whitewashed building with a red-tiled root, perched on a ridge overlooking the farmers’ thatched cottages. A simple shrine of Paladine, surmounted by the god’s silver triangle, stood watch on the village’s other side. It was wearing on midnight, and the farmers were asleep, the rich folk above finishing their evening meal and perhaps listening to a wandering poet’s latest epic or playing at khas in their parlor.

Two guards stood watch at the hamlet’s edge, rough men who held their spears awkwardly, more accustomed to the feel of a flail or scythe. They muttered together in hushed voices, and one laughed, lifting a jug of wine. He drank deeply, then passed it to the other.

The two wizards stood ten paces from them, cloaked by magic. Andras had worried there might be dogs to pick up their scent, but the only one around was an old bitch asleep beneath a wagon. He looked a question at his master, whose eyes glittered.

“I’ll take the one on the right,” whispered Nusendran. “The other is yours. Be swift.”

Andras nodded, a dark, sweet thrill running through him. He hadn’t expected he would have the chance to kill with sorcery tonight. Swallowing, he looked back to the guards, and began to gesture, pointing. “Obrut ku movani, yatho viskos daldannu. ”

The man on the left was still drinking when the spell took hold, and so, when the wine sprayed from his mouth and the jug crashed to the ground, his fellow started to pound him on his back, sure he was choking. Andras smiled, reaching out with magic to squeeze out the man’s breath. He clenched his fist, and the guard collapsed, eyes bulging, clutching at his collar. The other man gaped as, with a last, twitching kick, the guard fell limp.

Nusendran grunted approvingly, then spoke, and all at once the darkness around the second guard began to writhe. In a heartbeat it coalesced into a black serpent, with eyes of jet and a mouth of obsidian fangs. The guard stared, his mouth opening to scream. In a flash, the shadow-snake struck, ripping out the guard’s throat. A fan of blood shot through the air as he collapsed.

Nusendran sent the serpent to kill the sleeping bitch as well, just in case. Then the shadowy monster shivered and dissolved back into the night. The two mages held still a moment longer, watching and listening. All was silent.

They met no one else as they crept around the village, finally drawing up before a small pasture to the south, surrounded by a low, stone fence. Within, the pen was filled with small, woolly shapes: yearling lambs, all of them asleep. Andras glanced up at Nuitari: the dark moon was near its zenith now, fat as a summer plum. Nearly time.

Several lambs stirred as he and Nusendran hoisted themselves over the fence and dropped down into the pen, but none of them woke, and after holding still a moment, the two mages moved again. They split up, carefully stepping over the sleeping animals, eyes darting this way and that. Andras bit his lip as he went, feeling the black moon’s weight upon him.

“Boy! Over here!”

The whisper cut through the night, making Andras jump. He glanced across the pen. An orange tree rustled by the fence. Smiling, he started toward it.

There, surrounded by a sea of white fleece, was a single animal that was as dark as his robes. Teeth bared, Andras threaded toward the black lamb. As he went, he pulled a small opal vial from his sleeve. Unstopping it, he crouched beside the animal and waited.

Black Robe wizards used certain magic the other orders wouldn’t touch: spells that could make moldering bodies rise again or cause a man such agony he would smash his own skull to escape the pain. Others treated with the foul spirits of the Abyss. Demons, however, didn’t aid mortals for free.Without the proper offering of appeasement, they would rip apart any sorcerer who dared disturb them. Nusendran had been preparing for months to make contact with such a fiend, but the spell demanded the lifeblood of a black lamb, stolen when Nuitari soared full in an empty sky. A night like tonight.

A soft word hissed, and Nusendran shimmered back into being. In his hand was a long knife of cold-forged iron. Andras ended his invisibility spell as well, holding out the vial.

“Hold it steady,” the elder mage said. “This will be over quick.”

Andras nodded. Nusendran bent low over the lamb, set the blade’s tip behind the animal’s ear, whispered a prayer to Nuitari, then drove the dagger home.

The lamb shuddered, kicking, but made no sound as it went limp. Nusendran jerked the blade free, then opened the veins in the animal’s throat, freeing a crimson torrent to soak the earth. Andras moved quickly; the warm blood poured into the vial and soaked his hands. He rose, replacing the cork with fingers that glistened red.

For the second time that night, Nusendran smiled. He wiped the knife on the dead lamb’s wool and sheathed it again.

“Good,” he said. “Now let’s go, before-”

Another voice rose, clear and loud and close. “Cie nieas supam torco, Palado,” it intoned, “mas bodoram burtud.”

Andras looked up, his breath catching. Like any lettered person in the empire, he knew the tongue of the Istaran church. Though I walk through night’s heart, Paladine, be thou my light.

A shaft of light, bright as the silver moon, lanced down upon the pasture. Nusendran and Andras froze as around them the lambs began to wake. The elder mage whirled, and Andras followed his master’s gaze, his lip curling. There, beneath a poplar tree, stood a man in a white cassock. In his hand, gleaming as it reflected the holy light, was a platinum medallion. A Revered Son, one of the servants of the Kingpriest of Istar.

The cleric wasn’t what made Andras’s eyes widen and his flesh crawl, though. Rather, it was the men flanking him: a dozen knights in mirror-bright armor and horned, visored helms. Half of them cradled loaded crossbows. The rest gripped swords. Emblazoned on their white shields and snowy tabards was an emblem that made hate surge in Andras’s heart: a golden hammer, limned with scarlet flames.

“Ten eyes of Takhisis,” he swore, staring. “Master-”

“Run!” Nusendran shouted, shoving him.

The lambs bleated madly as they fled. Behind, the knights shouted for them to halt.

Andras heard the click of crossbows. He shut his eyes, waiting for the pain of quarrels burying themselves in his flesh, but his master was quicker. Beside him, Nusendran twisted a garnet ring on his finger, and a sphere of golden light burst about them. The bolts struck the light as if it were a wall of stone and spun away, sparking. The knights’ shouts turned to curses, and Andras laughed.

Armor clattered after them as they vaulted the fence again. Andras stumbled over a tree root, nearly fell. Nusendran made no effort to help him. Righting himself, he ran on, catching up to his master as they reached the village’s edge.

Suddenly, there were more knights in front of them as well, swords bristling, Nusendran snarled a vile curse as he skidded to a halt. Andras staggered up beside him. His hood had blown back as he ran, as had his master’s, and his heart dropped when he saw how pale Nusendran was. Even the old man’s lips were the color of bleached bone. Andras had never seen his master afraid before. Now both men were terrified.

The knights clattered nearer, surrounding them. Snarling, Nusendran flung out his arm, and darts of violet light struck three of them with a thunderclap. The reek of burnt flesh filled the air as boneless bodies rattled to the ground. Nusendran wasted no time, dashing toward the gap in the knights’ ranks….

A quarrel hit him in the back, spinning him around. He fell, gasping and clutching at the bloody point sticking out of his breast. Andras stared, his jaw slack. Nusendran glared up at him, his teeth clenched.

“Do something, damn you,” the mage wheezed.

It was too late. Andras was winded, and the magic he’d wielded tonight had drained him. He had no strength to fight, nowhere to run. The knights closed in-

Something strange happened.

At first, Andras thought his eyes were playing him false, but after a moment he knew it wasn’t so. There was a cloud of silvery motes in the air, surrounding him, growing brighter with every breath he drew. The knights saw the cloud too and halted their advance, glancing warily at one another. Nusendran’s eyes went wide.

With a noise like shattering crystal, the motes flared sunbright. Andras saw his master’s shocked face, saw the knights fling up their shields to protect their eyes-then the light blinded him, and he saw no more.

Andras awoke in a bower of acorn-heavy oaks, propped against a gnarled, mossy stump.

It was dark, and the world swam before him as he struggled to sit up. He knuckled his eyes, trying to get them to work. What had happened to him? He could remember the knights, his master falling, the silver light … and now, this place. Where in the Abyss was he?

“Get up, lad. You’re just in time to watch.”

The voice was like none Andras had ever heard before. In his training as a Black Robe, he had met scores of dark-hearted mages, and more than a few priests of the evil gods. He had even listened while Nusendran communed with minor demons. None of them, however, had sounded so eerie, so cruel. It seemed the air actually filled, with frost at the sound.

Shivering, he twisted, looking for its source.

There were many tales of the man his brethren called the Dark One, the mightiest of all the Black Robes, but few were privileged to encounter him. Now, though, Andras found himself staring at a tall, broad-shouldered form whose plain black robes made him all but invisible in the bower’s gloom. His hands were age-spotted and almost skeletal, his face mercifully lost in his hood’s shadows. Only the tip of a long, gray beard emerged from that darkness. Magical power seemed to seethe about him, rippling the air.

“Fistandantilus,” Andras breathed.

The hooded head inclined. “You know me,” said the cold voice. “That will save time. Come, boy. You should see this, before it is done.”

With that, the archmage turned and strode away, into the shadows.

Andras hesitated, torn. His instincts screamed at him to flee: even the highest among the Black Robes feared Fistandantilus. But he knew, too, that the Dark One was not the sort of man from whom one escaped. It would only make the archmage angry if he fled, and tales of Fistandantilus in his wrath were the sort that robbed necromancers of sleep.

Shuddering, Andras rose and followed the robed figure into the night.

He emerged from the oaks at the edge of a cliff, above a narrow ravine. In the distance, on another ridge, was the farm-villa, lights now blazing in all its windows. And below, near the creek that snaked through the ravine’s heart, were the knights.

There were thirty of them and three clerics whom he could see-the Revered Son of Paladine in his white vestments, a Mishakite healer in pale blue, and a war-priest of Kiri-Jolith in gold. They were all singing a hymn in the church tongue. He couldn’t quite make out the words. Many of the knights had doffed their helms and held the hilts of their swords to their lips as they stared past the clerics toward a bonfire that burned beside the stream.

It was a high blaze, flames snapping and popping ten feet tall, cinders billowing to soar away on the night wind. Andras frowned, wondering why the knights would build such a fire-but only for a moment. Then he saw the form amid the flames and knew.

Little remained of Nusendran but a charred husk hanging from manacles affixed to a stake. His hair and robes had burned away, his flesh peeled and bubbled as the fire caressed it. The wind was wrong for the stink to reach him, but Andras’s mind fooled him into smelling the stench of death anyway. Groaning, he bent forward and vomited over the cliffs edge. When that was done, he leaned against a tree, gasping.

Fistandantilus was right beside him, cold coming off him in waves. His voice held no sympathy whatsoever.

“Poor Nusendran, the old fool. He died cursing them, you know.”

Andras didn’t look at the archmage. Instead, he stared at the flames, his eyes shimmering with their light. He clenched his fists, fighting down his rage. If he didn’t, he knew, he would charge at the knights now. Perhaps he would be able kill one or two before they brought him down, but bring him down they would.

He took a deep breath. “I have to tell the Conclave.”

“The Conclave are useless,” Fistandantilus replied. “Do you think this is the first time this has happened? The White Robes and the Red Robes have heard this tale many times, and still they do nothing to help those who wear the Black.”

It was true, Andras knew. Nusendran had known several mages who died at the hands of the Kingpriest’s men. Even one of the wizards who had administered the Test for Andras had perished thus. The Black Robes who served on the Conclave demanded that the orders take action, but the White and the Red held them in check, too leery of the Kingpriest’s power to act. They would do nothing for Nusendran.

“You want vengeance,” Fistandantilus murmured, “and well you should. Not just for Nusendran. For all our brethren who have died in the Kingpriest’s pogrom. I can give you that power. Come with me, Andras, and if you are patient, one day you can show the Knights of the Divine Hammer the meaning of grief. Or deny me, and-”

He pointed down into the ravine, then turned and strode away. Atop the cliff, Andras stared at the flames, the charred form of his former master drooping as the Revered Son quenched the fire with holy water-and saw something else. He hadn’t noticed it before, but now the sight of it lodged a dagger of ice in his heart.

A second stake.

Andras stood rigid, his stomach twisting. The stake had been put up for him. If Fistandantilus had not cast the teleport spell that brought him here, his withered form would be hanging beside his master’s, even now. He wore the Black, so they wanted him dead. His rage crystallized within him, turning diamond-hard.

His blasted face dark with hate, he turned and strode after the Dark One.

CHAPTER 1

Eleventhmonth, 942 I.A.

Folk called the rock the Hullbreaker, and as he squinted through the lashing rain, Cathan MarSevrin could see why. It was a sea captain’s nightmare, a great spire of dark stone half a mile from shore, jabbing up from the angry sea like the talon of some ungodly beast. The stub of an old lighthouse jutted from its peak, but it was dark as a skull, abandoned to weeds and the gales. Any mariner who plied the seas off Istar’s northern coast knew well enough to give it a wide berth, but if the fisherfolk were to be believed, the sea floor about the rock ran thick with ancient shipwrecks. The young and foolhardy, craving riches and adventure, sometimes went diving out by the Hullbreaker, seeking treasures lost for centuries. Few returned with any booty of value. Some didn’t return at all.

Cathan hadn’t come to the Hullbreaker for wealth. The rock held other promises for him. He ran a hand up his face, pushing water into his dark hair-thinning now as he neared his fortieth year, and graying at his temples to match the frost in his beard-and reached down to touch his sword, Ebonbane. Its hilt, gold encrusted with shards of white ceramic had seldom been far from his reach in the twenty years since he’d first buckled it on. A Knight of the Divine Hammer seldom went anywhere without blade or bludgeon at hand.

Lightning forked across the sky, pink and jagged. Thunder followed an eye blink later, loud enough to set Cathan’s ears ringing. He didn’t flinch, though some of the other knights standing nearby did. There were better places to be during such a violent storm than standing on the edge of a high sea cliff, particularly clad in heavy armor.

“Abysmal night,” said Sir Damid Segorro. He was a small, wiry man whose nut-brown skin and beaded hair marked him as hailing from the province of Seldjuk. He wore glistening scale mail in place of the other knights’ plate, and his sword was short and curved. He scowled at the clouds, which seethed with flashes of light.

“Dragon weather. I’d sooner do this when we’re less apt to get smashed to flotsam.”

Cathan didn’t glance at his second in command. He’d fought beside the little easterner for more than a year-long enough to know Damid was no coward, only cautious. He may have a point, Cathan thought, glancing over the cliffs edge at the rocks below. Surf exploded against them and about the Hullbreaker in great white blossoms. Beyond, the sea heaved and chopped like a living thing. Audo conib, mariners called it, from the safety of harbor taverns. Hungry water. Those who sailed it called it worse.

Cathan shook his head, a smile curling his lips. “Where is your faith, friend?” he asked.

“The god will protect us.”

Damid met his gaze, but only for a second, then looked out to sea. Despite all the months they had served together, the Seldjuki still couldn’t look into Cathan’s eyes for long. Few men could. Cathan’s were no ordinary eyes, but were dead white, empty. In the storm’s coruscating light they seemed to flash with their own inner fire. They had been so for more than half his life, and Cathan had long since gotten used to men and women averting their gaze. No other man on Krynn had eyes like his.

But then, no other man on Krynn had died and lived to tell the tale.

He looked past Damid to his fellow knights. They were all mailed and armed, white surcoats plastered to their breastplates by the rain, golden hammers burning upon them. A few had donned their helms, closing the visors against the weather, while others let the storm’s fury buffet them. They were thirty in all, a smaller force than Cathan was used to commanding. A senior marshal in Istar’s holy knighthood, he usually led regiments of a thousand men or more, both knights and Scatas, the common footmen of the imperial army.

Tonight, though, a thousand men would not do. He only needed these few to bring down the Skull Brethren.

Cathan had been hunting the Brethren for more than a season now, following one clue to the next. They were followers of Chemosh, among the last of the death god’s cultists left in the empire. They practiced their foul rites in secret, stealing corpses from beneath the earth and live folk from above it to sacrifice to their unholy deity. Week after week, month upon month, Cathan and his men had searched in vain, finding only a few abandoned fanes with altars rusty with old blood. Finally, however, their quest had led them to the Hullbreaker. The Chemoshans’ main temple was there, far from the eyes of common folk, where they could practice their foul rituals in safety.

That will end tonight, Cathan thought, touching Ebonbane again. By the god, it will.

“Sir? Sir!”

He blinked, snapping away from his musings to face the man who had spoken. It was his squire, a boy of sixteen summers with a wide, freckled face and a mane of straw-colored hair that he had gathered into a long ponytail. His armor was simple chain mail, the hammer on his blazon silver, reflecting the fact he had not yet been dubbed a knight. The eagerness in his eyes made them shine nearly as bright as Cathan’s own.

“What is it, Tithian?” Cathan asked.

“Sir, the boats are ready,” said the youth, who was Cathan’s squire. “Shall we go now?”

Cathan glanced at Damid, who shrugged, a grin twisting his lips. Tithian’s enthusiasm amused the Seldjuki, and Cathan had to fight back an answering smile. A Marshal of the Hammer didn’t mock his men, least of all for zeal. Besides, his own blood was beginning to warm a little, as well. After many years fighting evil in the Kingpriest’s name, the song of battle still rang within him.

“Very well,” he said: “Let’s attend the clerics first, though. We need our blessings before the battle.”

There were four priests in Cathan’s company, and now the knights gathered before them, heads bowed. Serissi, a silver-haired, iron-jawed woman in Mishakite blue who served as the band’s healer, prayed to her goddess to keep the knights safe from harm.

Revic, a mountain of a man with Kiri-Jolith’s golden tabard over his mail, cut the palm of his hand with a dagger, pouring his blood on the ground in the hopes that it would be the last they would shed that day. Athex-swarthy, fat, and draped in the purple of Habbakuk the Fisher-daubed the knights’ foreheads with blessed saltwater, reciting prayers of protection from the sea. Last, stooped by age and snowy vestments made heavy by the rain, came white-bearded Ovinus, Revered Son of Paladine, who sanctified them in the name of the holy church.

“Ucdas pafiro,” Ovinus prayed, signing the sacred triangle of Istar’s highest god, “nomas cridam pidias, e nos follas ebissas. Sifat.”

Father of Dawn, bring us glory, and guide our swords true. So let it be.

“Sifat,” the knights echoed. Each drew his weapon-sword, mace, or hammer-and laid a gentle kiss upon it. Then they turned and started down the cliff face.

The men who had once tended the Hullbreaker’s lighthouse had carved a long, narrow stair from the stone here. Wind and water had worn the steps smooth, and they were slick with rain, so the knights had to move slowly, creeping down to the rocky shore. Spray from the bursting surf billowed high above them. Most of the younger men, and a couple of the older ones too, stared at the water with dread-all the more so when they beheld the pair of boats that would carry them to battle.

They were puny things, six-oared shorecraft that bobbed and thudded against each other in the shallows. Damid coughed and sucked on his wispy moustache, and Tithian’s eyes were so wide, it seemed they would pop out of his skull. Cathan, however, merely nodded to himself, staring past the seas to the pillar of rock that was their destination. The storm was bad, but there would be no better time to assail the Chemoshans’ temple. The cultists would not see them coming in the tempest.

“Get in!” he shouted, above the storm’s roar. “As we arranged! Go!”

Several of the men were pale, their faces looking green in the lightning’s glare, but they all obeyed. They had taken oaths when they became knights, so on they went, sloshing through knee-deep water, then hoisting themselves over the gunwales. Cathan went last of all, clambering up to the prow of one vessel. It bucked beneath him as the sea swelled and dropped, but he kept his footing. He reached to his belt again, but this time his fingers didn’t find his sword. Rather, he pulled free a string of glistening pearls, letting them slide and dangle among his fingers. Drawing a deep breath, he held them out, pointing toward the rock.

“Palado Calib,” he said, “me iromas, tus ban abam drifo.”

Blessed Paladine, clear my path, that I may walk it without fear.

With that, he broke the string and flung the pearls away. A tiny hailstorm of pearls pattered down into the water before the skiff. Cathan held his breath, waiting. The sea swallowed them and continued to seethe for a time. Then silver light flared beneath the surface, and the water began to change.

Legends spoke of ancient priests, so rich in Paladine’s power that they could calm whole oceans with a prayer. This invocation wasn’t so strong. Beyond the foam-drenched rocks, the waves kept hurling themselves madly toward destruction. Around the two boats, however, the surface grew smooth, like a great sheet of Micahi glass. It didn’t even ripple when the oarsmen dipped their blades into it. The knights regarded it for a good while, wonder in their faces, then looked to Cathan again.

He smiled, his silver eyes flashing as a bolt of lightning struck the ruins atop the Hullbreaker. Slamming down his visor, he drew Ebonbane and pointed it forward.

“On, then! In the Kingpriest’s name!”

“For the Lightbringer!” the knights replied as one. Then the oarsmen set to, and the boats shot away from the shore.

The Chemoshans had set watchers on the rocks at the spire’s foot: six men with leather cuirasses under dark cloaks, and helmets made from the skulls of goats and wolves. In the storm’s fury, though, they didn’t notice the boats gliding toward them on patches of smooth water until they had pulled up to the Hullbreaker itself. The knights began to pour out even before the skiffs bumped to a stop, shouting the names of Paladine and the Kingpriest as they clambered up the slippery rocks. Shocked, the cultists hurried to block them, five brandishing sickle-bladed swords while one scrambled back toward a fissure in the stone, is robes flapping behind him.

The guards died quickly, in a clamor of steel. They were too few, the Divine Hammer too well trained. The followers of the death god fought without fear of being killed, but that didn’t stop steel from sliding between their ribs or opening their throats. Less than a minute after the battle began it was over, their bodies sprawled in tidal pools, the water billowing red about them. One young knight won a fresh scar on his chin from a sickle-blow, but other than that the knights escaped unharmed.

Still, the cultists achieved at least one goal: the last of them escaped, disappearing into the fissure, shouting madly. The knights tried to give chase, but the ground was too treacherous, and he was gone before they, could stop him. Cathan cursed.

“So much for surprise,” said Damid.

Scowling, Cathan waved his sword, then plunged ahead toward the cave. “Quickly, men!” he shouted. “Take the fight to them!”

In the knights went, Cathan at the fore, Damid at his side. The tunnel was rough and close, its walls smeared with bloody handprints. Torches guttered in wall sconces, making the shadows dance. The way sloped down, a trickle of rainwater flowing along its midst as it twisted deep beneath the spire. As they left the din of the storm behind, a new sound rose, seeming to come up through the rocks beneath their feet. It was a deep thunder, the pounding of drums. Cathan signed the triangle. The Chemoshans skinned their instruments with hides flayed from living men. They made pipes of bones, too, but the knights were too far away to hear those yet.

All at once, the drumming stopped. For a heartbeat, the tunnel was horribly quiet, save for the clatter of the knights’ armor. Then came a chorus of angry shouts, punctuated by ululating howls that echoed up the tunnel. Biting his lip, Cathan glanced over at Damid.

The Seldjuki’s eyes were closed, his lips moving in silent prayer. Cathan offered a quick entreaty to the gods as well.

The smell hit them.

It was sickeningly sweet, like the attar of some terrible flower, with a meaty, greasy stench beneath: the reek of rotting flesh. Several knights choked as it clogged their nostrils, and toward the rear a squire was noisily sick. Cathan focused and held firm. He had fought Chemoshans before. He’d been expecting this, and he tightened his grip on Ebonbane as the shadows down the tunnel began to move.

The fane’s defenders wore no skull helms, wielded no sickle swords. They walked unsteadily, the scuff of feet dragging across the floor the only sound of their approach. They did not speak, growl, nor even breathe. The Chemoshans’ protectors were dead.

The stench grew unbearable as they staggered into the torchlight. They were horrible to behold, all rancid flesh and glistening bone, slack-hanging mouths and clutching, clawed hands. The Chemoshans’ rites gave the dead power to move but not to think. They were as mindless as the creatures that scuttled among the shipwrecks outside. They shambled on, seeking warm flesh, every step an affront to all that was holy.

The first of the dead was a big man who had clearly died by drowning. His flesh was swollen and blue, and there were hollows where the crabs had taken his eyes. Cathan cut him open with a stroke of his sword, slitting his belly to let his entrails slide out. The wound barely slowed the lurching horror, though, and it took a second slash from Damid to drop it, its bloated head spurting free of its shoulders and smacking against the corpse behind it. The creature went boneless, hitting the floor with a wet smack.

The second ghoul had died more violently, a gash in its throat gaping like a second smile. The cut did not bleed, nor did its arm when Damid’s scimitar took it off at the elbow leaving ragged strips of sinew behind. Cathan finished it with a thrust through its mouth, turning it as limp as a Pesaran puppet with the strings cut off.

On they came, one grisly wight after another: one with the side of its skull staved in, another with a broken spear shaft still sticking from its belly. Cathan’s eyes watered at the stink as Ebonbane rose and fell, rose and fell, in concert with Damid’s weapon. After a time, they began to tire, their blows becoming slow and clumsy, so they fell back, letting the next two knights take over the gruesome butchery.

It was one of that pair, a young knight named Sir Alarran, who became the first of the Divine Hammer’s casualties. He was fighting his fourth corpse, his blade dancing in tandem with the mace of the man beside him, when somehow the enemy got past his defenses and buffeted the side of his head with its’ fist. His helm came off, clattering against the wall, and he staggered to one knee, jabbing his sword through the corpse’s gut as he dropped. The ghoul did not fall, however. Even as the other knight rained blows down upon it, it lunged at Sir Alarran, broken yellow teeth clamping down on his forehead.

Alarran screamed. There was a sickening crunch.

A heartbeat later, the other knight’s mace struck the corpse in the ear, crushing its head to a pulp. It was too late, though. Alarran was dead. Another knight rushed forward to take his place.

The knights pressed forward. By the time the tunnel’s slope began to level, six more of their number had fallen and more than half a hundred corpses lay in their wake, hacked and crushed, a few still twitching. Finally, the numbers of the dead began to thin, and the tunnel opened out into the enormous cavern that was the Chemoshans’ fane.

The cave was vast, fifty paces across. A great, dark pool filled half of it, fed by dripping stalactites above. Firelight painted the walls, leaping from copper braziers festooned with skulls-animal and human alike. The dreaded drums towered atop the broad stumps of two broken stalagmites, and more skins hung upon the walls, stretched on wooden frames and painted with unholy sigils. Skull-helmed Chemoshans, two score and more, filled the fane, and more ghouls lurked in the shadows. On a stony outcrop above the pool was the altar itself, the huge skull of a long-dead dragon, cut open so its brainpan formed a bowl for sacrifices. Beside it, clad in midnight robes and a bear-skull headdress encrusted with scarlet and black gems, was the head of the cult, the Deathmaster.

Seeing the knights from across the cave, the high priest raised a hand-dark with blood from whatever offering he’d been preparing in the altar-and roared for his men to attack.

They obeyed, charging at Cathan and his men with sickle swords and wavy-bladed knives.

The remaining ghouls lurched behind. The knights raised their shields to repulse the charge, and for a time the cavern filled with the crash of steel against steel. The wounded and dying shouted out the names of gods both light and dark.

The knights were outnumbered, but they fought hard, and again the cultists were no match. Men died on either side, but the Divine Hammer slew three for each of their own. In time, the Chemoshans’ lines faltered, then gave way entirely.

The battle broke up, the Chemoshans’ lines unraveling into small pockets that soon fell before the knights’ swords. They died howling curses at their killers, their eyes blazing with hate. Cathan and Damid pushed past, Tithian and a half-dozen other knights on their heels as they charged the altar. Another knot of priests awaited them there, and these diehards fought even more furiously than their brethren had, desperation and fury fueling their strength. Even so, they were no match for the Hammer.

The Deathmaster had stayed by the altar, no weapon in his hand, his long-bearded face twisted into a cold sneer. There was no fear in his eyes, though his own end was surely at hand. He had made his pact with Chemosh, Cathan knew. His only desire now was to take his foes into death with him as many as he could. Cathan led his men up the steps of the fane’s makeshift dais, Ebonbane flashing red in his hand.

Smiling, the Deathmaster raised a finger to point at him.

Cathan froze, feeling the death god’s presence surge through the fane. Seconds became centuries as he watched the high priest’s eyes flare blood red, and crimson light swell around the man’s fingertips. A strange, itching heat spread across his skin, swiftly gathering into pain….

Something hit him from behind, knocking him to the ground.

Damid.

Cathan felt the Deathmaster’s spell leave him, saw his fellow knight freeze, scimitar upraised. “No!” he shouted, reaching out. “Get-”

With a sound like claws scratching slate, the crimson light around the Deathmaster’s hand became a whip, a scarlet strand that lashed out and wrapped around and around Damid. The Seldjuki screamed, dropping his sword, then shuddered as his cry rose into agony, muffled by the magical cocoon. Cathan clutched at him, but the webs burned where he touched them, and he snatched his hand back with a hiss.

For an instant, everything was still. Then the magical fibers sprang loose, and tore Sir Damid Segorro apart.

Bits of flesh spattered the stones, splashing down into the pool below. Steel armor ripped apart like tin. Red mist filled the air. Amid it all, Damid’s ghastly skeletal remains collapsed in a ruin of bone and tendon.

A mocking laugh burst from the Deathmaster’s lips as the knights stared at what remained of their fellow. Eyes blazing with madness, he reached out toward Cathan again-

— and stopped, staring at the sword that had just buried itself in his stomach.

Cathan blinked, turned, and saw Tithian. His squire no longer held his blade.

Recklessly, he had hurled it at the Deathmaster, and somehow the throw had struck true, burying the blade halfway to its quillons in the Chemoshan’s gut. It was hard to say whether he or the cult’s leader looked more surprised.

The Deathmaster fell to his knees, still gaping at the weapon. Furious, Cathan got to his feet, reached down, and lifted Damid’s scimitar. Setting his own blade aside, he walked to the high priest, grabbed the bear’s skull, and wrenched it from the man’s head. The Deathmaster was old, his face scarred by some long-ago pox. There were finger-bones woven into his hair and beard. He looked up, his dark eyes shining with fanatical hatred.

When he opened his mouth to curse Cathan, though, only a dark rope of blood spilled out.

“By the Divine Hammer,” Cathan pronounced, raising his dead friend’s blade, “in the name of god and Kingpriest, I condemn thee. Du tas usam, porved.”

Go to thy god.

The blade fell.

CHAPTER 2

The Knights built two pyres the morning after the attack, on the cliff tops overlooking the Hullbreaker. The storm had broken, yielding to gray skies fringed with blue in, the south, and the sea had lost its rage. Gulls wheeled above, and crows as well, drawn by the smell of the dead. Far off, well beyond the stone spire, the dark speck of a lone caravel plied the waves.

The first pyre was a jumble of driftwood and scrub, thrown in a crude heap. Sprawled upon it, arms outflung and, often as not, eyes staring wide, were the Chemoshans and the stinking corpses who had served them. A few of the death cult’s ghouls still twitched, clinging to their horrible unlife. The knights had spent the better part of the night dragging them back from the Hullbreaker, The Church mandated that servants of evil be purified with flame, and so Cathan threw first torch onto the pyre as the company’s priests flicked oil upon the bodies. The conflagration leaped high, the trailing black smoke across the sky.

The second pyre, placed upwind of the first, was smaller-Paladine be blessed, Cathan thought as he looked upon it. It was carefully stacked, cut from a stand of goldleaf trees that stood inland. The bodies upon it were more orderly, each laid upon his shield, his hands grasping his weapon upon his breast. The dead knights’ eyes were closed, the more ghastly wounds covered with white linen. Here the priests took greater care with the rites of sanctification. They laid blocks of sweet incense among the dead, carefully daubed-each with oil, and recited the Ligibo, the ritual for those who died fighting in the god’s name.

“Porasom, usas farnas,” the clerics prayed, “e bonasom iudun donbulas, Palado fi.”

Go, children of the god, and dwell beyond the stars, at Paladine’s side forevermore.

As one, the surviving knights-twenty in all where thirty had stood the night before-drew blade and mace, and raised them high in salute. “Sifat,” they murmured.

Here, too, Cathan lit the first brand. He had lost count of how many men of the Divine Hammer-and boys, for that matter-he had burned over the years. Too many faces to remember, all of them martyrs in the Kingpriest’s name. Today, though, it was harder to light the fire. Damid, whose body lay shrouded to conceal how the Deathmaster had ruined him, had been more than just a comrade at arms. They had spent many good days together, drinking in wine shops and laughing at each other’s tales. They had journeyed from one end of the empire to the other. Now those days were done, and Cathan felt tired and old. It wasn’t like losing a brother, as some men said-Cathan’s own brother was twenty years gone, victim to a terrible plague, and that loss was still a thorn in his heart-but it hurt all the same.

“Farewell, my friend,” he said, as he set the pyre ablaze.

He walked away, not bothering to look back as the other knights added their own torches to the pile. He went to the cliffs edge, staring out at the caravel with his colorless eyes. The wind snapped at his white tabard, and fine rain began to fall. Sighing, he reached to his belt and pulled forth a talisman of bones and teeth, tipped with a rat’s skull. Black sapphires glittered in the empty sockets. He had pulled it from the Deathmaster’s neck, as proof the old man was dead. There was still blood on it. Now he stared at it, drawn into its ebon gaze.

Behind him, someone coughed. Cathan started, closing his fist around the talisman, and glanced over his shoulder. Tithian stood there, freckled, shaggy, and gangly.

Confronted with his master’s strange stare, he flushed deep red and looked down at his boots. The other knights and squires had taken to calling him Sword flinger after the battle.

Though Cathan had been only slightly older when he first became a knight, Tithian still looked little more than a boy.

“This war,” he said, scuffing the ground with his foot. “It never will end, will it, sir?”

Damid would have laughed at the question, in his infectious way. Just remembering it made Cathan chuckle. Seeing Tithian’s flush deepen, he laid a hand on the boy’s shoulder.

“This is no war, lad,” he said. “We fight the battle every pious man fights, to rid himself of evil-only we fight it for the empire. Our task is to keep the darkness at bay, not to destroy it utterly.”

In its early days, the Divine Hammer had sought to eradicate all evil in Istar. It remained the knighthood’s stated policy, even now. The Kingpriest still spoke of his promised kingdom of eternal light, where the sun would burn so brightly there would be no need for shadow. After so many years, however-so many lives lost-Cathan had found that as weak as the servants of darkness grew, there were always more of them. Perhaps there always would be.

Tithian coughed again, still studying his toes.

“What is it?” Cathan asked.

The squire squirmed beneath his stare. “Well, sir. I mean. It …” He stopped, took a deep breath. “The men say I’m to be knighted for … for what happened.”

Cathan scowled. Those dolts, he thought. I’d been hoping to keep it a surprise.

“Of course,” he said reassuringly. “You don’t do what you did and just get a pat on the head, lad. When we get back to the Lordcity, Grand Marshal Tavarre will dub you himself.”

He paused, frowning as he studied the boy’s grimacing face. “You’re supposed to be happy about that news, Tithian.”

“I know, sir,” Tithian said. “And I’m glad. But…well, I’d hoped you would…”

Pride surged in Cathan’s breast. He’d had four squires before Tithian-all of them knights now, two already dead and burned-but none had asked such a thing of him.

Rightly so, too: the code of the Divine Hammer was clear that the only men who could confer knighthood were the order’s Grand Marshal and the Kingpriest himself. There was something different about Tithian, though. The boy doted on him. He’d been an orphan when the order first took him in, had never known his father, didn’t even have a family name. If Damid had been almost a brother to Cathan, Tithian was nearly his son — and as close as anyone would be, since as a holy order, the Divine Hammer demanded chastity of its members.

Cathan smiled. “Kneel, then.”

Grinning like a kender, Tithian obeyed. His mail rattled as he lowered himself to the rocky ground.

“You understand this isn’t the official ceremony,” Cathan said. “Tavarre will still take care of that. You’re not getting out of your vigil that easily.”

Tithian nodded, still beaming. Chuckling, Cathan reached across his body and drew Ebonbane. The rasp of metal drew the other knights’ attention, and they looked on in surprise as he raised the blade, then set it down on his squire’s shoulders in turns-left, then right, then left again.

“All right,” Cathan bade, sliding his sword home again. “Get up. You’re not a true knight yet, lad, but you’re one in my eyes.”

Any wider and Tithian’s smile would have split his head in two. Leaping to his feet, he clasped Cathan’s arms. “Thank you, sir,” he gushed. “Thank you!” He dashed off, back toward the other squires, who were eyeing him jealously.

Cathan shook his head, watching him go. Then his gaze drifted along the bluff, taking in the two pyres, and his smile faltered. He signed the triangle. Tucking the talisman back into his belt, he turned and stared out to sea once more.

The sky was filled with jewels. Diamond and ruby stars sparkled on black velvet. The two moons, disks of chalcedony and sard, glided over constellations Cathan knew well: the Valiant Warrior, horned Kiri-Jolith, the five-headed Queen of Darkness, and still others, each the sign of a god of light or darkness. There, amid it all, was the greatest gem of all: a globe of turquoise, fringed with wisps of cloud. The world. Krynn.

Cathan winced in his sleep, groaning. He knew this dream. It had plagued his sleep since the night before his dubbing. Not a month went by when he didn’t find himself floating here, among the stars. Every time, it was the same.

Small wonder it’s happening tonight, he thought. Once the pyres guttered out, the cultists’ ashes scattered and the knights’ gathered into a golden urn to be brought back to the Lordcity, his company had ridden inland, away from the Hullbreaker and the fierce sea winds. When they camped at nightfall, in a copse of swaying birches, the men of the Divine Hammer had all but fallen from their saddles. Cathan had forced himself to stay awake until the fires were lit and the watch set, then had climbed into his bedroll and fallen asleep as soon as he closed his eyes.

Now in his dreams he looked upon Krynn from high above, marking the continent of Ansalon amid the ocean’s blue. He saw each of its realms: Ergoth, Solamnia, Kharolis…the woods of the elves and the mountain fastnesses of the dwarves…the meadows where the kender dwelt, and the frozen barrens of Icereach…and there, larger than any, Istar the Holy, the Kingpriest’s glorious Lordcity shining at its heart.

Now something else. Something behind him, coming closer.

He turned, knowing already what he would see. The burning hammer was as much a part of the dream as the stars and moons, a great flaming mass streaking across the night.

It had been there the first time the dream came, the eve of his dubbing. The Divine Hammer took its name from the vision. As Cathan watched, it grew larger and larger against the night. Closer, closer…then streaking past him in a silent rush, close enough that its heat seared him, its light made his eyes sting.

Still he watched it go, fire trailing in its wake, diving now toward the turquoise orb.

Toward Istar. It was the god’s justice, come down to crush evil from the world. He ground his teeth, tensing as he waited for it to strike, the terrible roar of noise as it fell upon the empire….

“Sir? Sir, wake-”

Cathan’s eyes snapped open at once. A dark shadow loomed over him, a hand touched his arm. He sat up, reached for Ebonbane beside him, and had the sword halfway out of its scabbard before the shape resolved into Tithian. The boy straightened up, taking a step back, unafraid. This wasn’t the first time he’d woken his master from the throes of the dream.

It was dim out, and cool-it never got truly cold this far north. Fine rain, almost mist, dripped down through the boughs. The sun hadn’t risen yet, but it was trying, the sky and everything beneath it gray. The campfires had burned down to cinders, and most of the other knights were still asleep in their bedrolls. Off in the shadows, the horses whickered.

In the other direction, Ovinus’s low voice chanted. The Revered Son prepared to greet the dawn, such as it was.

Ebonbane hissed back into its sheath.

“Early,” Cathan muttered. ”What’s the matter?”

Tithian tugged at the collar of his tunic. “The lookouts spotted something.”

“Something?” Cathan raised an eyebrow.

“In the sky, sir.”

That was interesting. Throwing off his bedroll, Cathan rose to his feet. He ached worse than when he’d gone to sleep; but he put it from his mind. His squire handed him a horn of wine, warm from mulling over the fire, and he gulped it down as he slung his baldric over his shoulder. Ebonbane bumped against his thigh, reassuring. Tithian offered his helm next, but Cathan waved him off.

“Which way?” he asked.

The boy led him south from the camp, to where the wood gave way to hilly grasslands draped in cords of mist. Two of Cathan’s sharper-eyed knights stood just inside the tree line, staring at the clouds. One, an amiable hulk named Sir Marto, glanced back, then raised his hand in salute. He put a finger to his lips as Cathan and Tithian crunched through fallen leaves toward them. His partner, a lean, flame-haired fellow called Pellidas, continued to stare skyward.

“Strange thing, sir,” Marto whispered, his voice thick with the accent of the jungle province of Falthana. He tugged at his beard, forked in the style of his homeland. “Pell saw it not long ago. It’s been circling ever since. I think it’s looking for something.”

Pellidas nodded, saying nothing. He had been born mute.

Cathan frowned, looking up. His eyes were not as good as they’d once been. He couldn’t make anything out against the slate-colored pall. He muttered a curse. “Tithian, get my farglass,” he hissed.

The boy cleared his throat, Cathan glanced at him, and saw the boy already had the contraption he’d asked for-a brass tube with lenses of Micahi glass at both ends. He’d been thinking ahead, evidently. With a sheepish smile, Tithian held out the farglass.

Cathan took it, and held one end up to his eye, peering through it at whatever it was Marto and Pell had seen.

There weren’t many flying beasts left in Istar. The dragons were long gone, and such-wicked creatures as manticores and wyverns were few, all but unknown in the northern provinces. Perhaps it was a griffin, like the tame ones the elves in the Kingpriest’s court kept. Maybe even a winged horse. Legend said such creatures had once run wild on the empire’s grasslands and in the skies above. He’d never seen one, and the thought that one of the beasts might be above him now made him shiver. He tracked the farglass back and forth, searching, searching…

Then his lips tightened with irritation. ”Jolith’s horns, Marto,” he said, lowering the farglass. “That’s a bird.”

“That’s what I told Pell,” the big knight said, “but he made me look again.”

Cathan glanced at Tithian, who shrugged, then looked at Pellidas. The redheaded knight was still watching the circling shadow, the one that had looked to Cathan’s eye like some kind of common raptor. Falcons were widespread in Istar, which was why the first Kingpriests had chosen one for the imperial emblem. Frowning, Cathan raised the farglass back to his eye.

He found the bird again and studied it more carefully this time. There was something unusual about it, something not quite right about the way it moved. Its wings moved jerkily, and its tail feathers didn’t ruffle on the wind. There was something else, too-an odd glint in the gray morning light. It was almost as if…

“What in…” he began, then stopped, frowning. “Is that thing made of metal?”

Pellidas nodded. Marto tugged his beard. “Looks like it, doesn’t it, sir? That’s why I thought you might want to see. I’d reckon the thing’s magical.”

“Good guess,” Cathan muttered. Metal birds were something new, although Cathan had heard tales of animals and even men that wizards made of bronze or iron. He shuddered at the thought. He’d never had much use for sorcery. Marto had even less and was biting the heel of his hand to ward against magic.

He gestured to Tithian, not taking his eye off the hawk, and the boy dashed off, back toward the camp. The bird was searching-he could see its head swiveling this way as it wheeled above. He wondered what the mage who’d sent it was up to. Nothing good, he was sure.

Tithian was back before long, holding a crossbow and a quiver of quarrels. He strained to cock the weapon, loading it before handing it to his master. Cathan shook his head, though. “I can barely see the blasted thing from here,” he said, and looked to the other two knights. “Which one of you is the better shot?”

“That’d be Pell,” Marto said.

Sir Pellidas took his eyes off the hawk long enough to take the crossbow from Tithian, then looked back up, sighting along its length. He licked his lips, tracking the hawk across the sky, tightened his grip, and squeezed the trigger.

The string snapped forward, and the quarrel streaked away. Cathan followed its flight until he lost sight of it-then there was a faint, high clang. Marto laughed, clapping Pellidas on his shoulder; the redheaded knight smiled slightly as he handed the crossbow back to Tithian.

Cathan saw the hawk again a moment later, without the farglass. It was dropping now, plummeting earthward like a spent arrow. He watched it fall, wings hanging loosely. It hit the ground with a thud, fifty paces away.

Ebonbane made it all the way out of the scabbard now. Pellidas and Tithian drew their own blades, and Marto pulled a beaked war axe from his belt. Together they crept out of the trees, toward where the bird had hit.

It was half-buried, having dug a furrow in the grassy earth. Now it lay motionless, one wing snapped off, the other bent out of shape. It was a falcon, Cathan saw, but its plumage was copper and silver, its beak made of gold. Its eyes were yellow gems-sapphires, maybe, or topaz. The quarrel, made of hard steel, had caught it mid-breast and punched out its back. Pellidas nudged it with his boot, then reached down and yanked the bolt free. As he did, more bits of metal spilled out of the hole: tiny, toothed gears and springs knocked loose by his shot.

“Karthayan clockwork,” said Marto, who would know. He was from a small town near the fabled capital of Falthana, a rich city known for its tiered gardens and fine tinkers.

Some said the Karthayans had gnomish blood, such was their fondness for mechanical inventions.

Never having seen one, Cathan doubted the existence of gnomes. The thought of a race of mad engineers was altogether strange to him. There was no doubting, though, that the bird wasn’t magical at all. It was some sort of curious machine.

“Have you seen anything like this before?” he asked.

Marto shook his head. “Haven’t been back to Karthay in ten years, though. Gods know what they’ve been up to there.”

“There’s something tied to its leg,” Tithian said.

Cathan raised his eyebrows, then looked closer. His squire was right. Affixed to the hawk’s leg was an ivory tube, the sort of thing couriers used to keep scrolls safe from bad weather. There was something more-a platinum plaque attached to it. Etched into the metal was a symbol Cathan knew well: a noble falcon, clutching Paladine’s sacred triangle in its talons.

Marto roared with laughter. “The imperial arms!” he bellowed. “Branchala bite me, Pell-that’s the Kingpriest’s toy you killed!”

Sir Pellidas winced, his ruddy face turning bright crimson. Cathan had to fight back a chuckle. “It’s all right,” he told the mute knight. “You did it by my order.”

He tapped the broken bird with Ebonbane’s tip, making sure it wasn’t going to spring back to life, then bent down and pulled the scrolltube from its leg. Even before he broke the seal that covered the cylinder’s cap-blue wax, with the falcon-and-triangle stamped in it as well-he guessed the missive inside was for him. Sure enough, it was.

Cathan, the scroll read-in the Common tongue, for Cathan had never been very good at reading the language of Istar’s church-my old friend:

I write this epistle with mixed feelings in my heart. I had hoped to be joyful, for the twentieth anniversary of my coronation draws nigh. Indeed, I meant to summon you to my side anyway, to celebrate that glorious day. Sadly, though, I have heavier tidings to tell.

Marwort the Illustrious, who has long served me as envoy of the Order of High Sorcery, has died.

I know you have no love for wizards. Nor do I, be sure: The Black Robes remain a blight in the god’s sight, and those who wear the White and Red shame themselves by associating with such fiends. Marwort, however, has remained a steadfast part of my court for as long as I have ruled. I may not have approved of his sorcerous ways, but he was still a friend to the empire, and I mourn him.

For this reason, my friend, I am summoning you back to the Lordcity. Soon the Conclave will send a new wizard to take Marwort’s place. I would like you at my side, as you were in olden days, when they do. Return to Istar at once.

Beldinas Pilofiro

Voice of Paladino and true Kingpriest of Istar

PS: I hope the bearer of this missive amuses you. It is a new device, a gift from the Patriarch of Falthana. I am eager to hear what you have to say about it.

Cathan read the scroll twice, then rolled it up again and tucked it into his sleeve. The Kingpriest was right, he cared nothing at all for Marwort. The old wizard had seemed harmless enough, had even sided with the empire against his own order a few times. More than a few, actually. But he was still a sorcerer, and not to be trusted. With the Conclave sending a new wizard to take his place…

Cathan’s eyes went back to the broken hawk sprawled in the soil and wet grass. He sighed, then turned back toward the knights’ camp.

“Bring that,” he said to Marto and Pellidas as he strode into the wood, Tithian at his heels. “The pieces, too, and be quick about it. We ride for the Lordcity within the hour.”

CHAPTER 3

Twelfthmonth, 942 I.A.

There were five Towers of High Sorcery in the world, each of them old beyond telling and alive with the power of the moons above. Four stood within the cities of mortal men, constant reminders of magic’s might. They loomed over Daltigoth, the Capitol of Ergoth, and Palanthas, the greatest city in the knightly realm of Solamnia. Istar, for its part, had two-one in the Lordcity itself, and one in Losarcum, the fabled Stone City, which had been the heart of the kingdom of Dravinaar before war and annexation made that proud realm into the Holy Empire’s two southernmost provinces.

Mages of all robes-the White of good, the Red of neutrality, and even the hated Black-dwelt within the Towers studying and teaching magic, united by their love for their Art.

Each held artifacts and lore of inestimable value, as well as vast laboratories where the most learned wizards toiled to discover new uses for the magic. Those few common folk who had been inside the Towers spoke of countless wonders: demons imprisoned in shards of crystal, hallways and rooms that changed size and shape without warning, windows through which one could gaze out upon lands hundreds of leagues away. Statues got up and moved when no one was looking, and flashes of light and eerie sounds came from nearly every door or window. Even in Daltigoth, where they tolerated magic, folk gave wide berth to the Tower, and to the surrounding grove of enchanted pine trees. In the other cities, where people viewed magic and its practitioners with suspicion, they gave the lofty spires dark glances, signing the triangle or Jolith’s horns or the twin teardrops of Mishakal against whatever evils lurked within.

Of all the Towers, however, the greatest was the one folk didn’t see. It stood not in any city, but deep, deep in Wayreth Forest, an eldritch wood in the north of Kharolis. The forest appeared on few maps, for it tended to move, bordering the fabled elf realm of Qualinesti one day, tucked among the hills near the city of Xak Tsaroth the next. Such was Wayreth’s curious power that none saw the Tower except those the mages wished to see it. From everyone else, the Tower hid.

It was a strange-looking structure of a style seen nowhere else on Krynn. Surrounded by triangular walls, it consisted of a pair of obsidian cones, raised from the earth’s bones by forces of forgotten power. Narrow slits of windows broke up its black, gleaming surface. It had no battlements, no turrets. Hidden by the forest and protected by the power of sorcery, it had no need of mortal sentries. Within dwelt the mightiest wizards in an Ansalon: men and women whose power in the Art knew no equal. Even Fistandantilus the Old, the legendary archmage called the Dark One by his fellow Black Robes, kept apartments at the Tower, though-to general relief none had seen him there in centuries. There was no place in all of Krynn more alive with magic.

Leciane do Cirica stared up at the two towers, reaching up toward the stars like the claws of the great dragons that once had filled Ansalon’s skies. Solinari, round and bright, made the northern tower gleam with silver light. Lunitari, also full, made the southern one seem dipped in blood. Nuitari was up there somewhere too, Leciane knew, but she could not see it. She was no Black Robe, but rather wore the Red of those who walked the path between light and shadow.

The night wind gusted, cold enough to make her shiver. Around the Tower the forest remained green, but the tang of winter was in the air. It blew back her hood, momentarily uncovering a dusky face that had been breathtakingly beautiful when she was a girl. Even now, with her fortieth year behind her, she made most women half her age seem plain. The lines around her eyes and mouth, the threads of silver that crept through her long black curls, only accentuated her loveliness. Her green eyes sparkled with equal parts amusement and annoyance as she grabbed for her hood and pulled it down over her face again.

She had been at Losarcum’s Tower when the summons found her. She had residences both there and at Daltigoth, where she had taken the Test to become a full-blooded wizard.

The message had come not as words written on parchment or vellum but rather as a pair of disembodied lips, which had appeared before her and bidden her come at once to Wayreth.

She had obeyed, and now she was here, the mouth still floating in the air beside her. It was hard to tell but she thought it had a smug look to it.

“Well?” she asked. “No one to meet us?”

The pointed tip of a tongue poked out, running over the ruby lips. “Be patient,” the mouth said. “The Conclave are in discussion now. They will call you soon.”

She scowled. The Conclave, the rulers of High Sorcery, consisted of the orders’ strongest wizards, its most influential. A powerful sorceress in her own right, Leciane hoped one day to ascend to their ranks. For now, though, she was as bound to do their bidding as any neophyte fresh from his Test. Still, that didn’t keep her from glowering at the twin spires.

She’d spent a great deal of energy getting here, using the Art to speed her travel. Now, to be kept waiting…

The mouth twitched, then curled into a grin full of pointed teeth. At the same time, the air around Leciane shivered, shimmered with silver sparks. They fell upon her, cold where they touched her dark skin. She didn’t flinch at them, or at the sinking in her stomach as the spell took hold. This wasn’t the first time someone had cast a teleportation spell on her.

“Go, then;” said the magical lips, still smiling. “The Conclave welcomes you, Your Excellency.”

Excellency? Leciane thought, glancing at the lips. The lips chuckled, then disappeared.

With a silver flash and a shimmer of noise, so did she.

*****

The Hall of Mages was a vast, dark chamber in the heart of the South Tower, its full dimensions lost amid shadows. No lamps or candles lit it; only a dim, blue-white glimmer in its midst. Darkness hid its walls, ceiling, and much of the floor. Neither did the hall have any doors. The only way in was by magic, and powerful wards kept out all but the Conclave and those they allowed to enter. Once, an ambitious Black Robe had tried to force his way past those wards. Sometimes, it was said, the echo of his howls could still be heard through the Tower’s halls.

In the room’s midst, at the edges of the pool of light, a half-circle of chairs stood atop a raised platform. There were twenty one in all-seven each for the followers of the three moons. Wizards sat in each of them, clad in hooded robes, their faces drenched in shadow.

On the left, seven dressed in the White of Solinari-two of them elves from ancient Silvanesti, the rest human. On the right, an equal number of Black Robes, serving Nuitari, among them a gray-bearded Daergar dwarf. Between the two groups were seven of Lunitari’s Red Robes, all of them human. In their midst, the only one among the Conclave who did not wear a hood, sat Highmage Vincil, the leader of all Krynn’s sorcerers.

He was an Ergothian of more than sixty summers, his skin as dark as polished mahogany. His head was smooth-shaven, save for a white ponytail at the back, and his beard was long and shovel-shaped. He steepled his fingers, saying nothing as he gazed down from his seat. His gray eyes might been hewn of granite.

Leciane stood before him, unafraid. She had known Vincil before he became highmage, even before the Red Robes had invited him to join their delegation on the Conclave. She had been his apprentice, both before and after her Test. She had also been his lover. All that was in the past, ten years and more, but they had remained friends since.

She raised her eyebrows, arms folded across her chest.

“What do you mean, ‘excellency’?”

The archmages glanced at one another, stirring slightly. She looked to either side.

Neither the Black Robes nor the White seemed happy. Ysarl, the most-powerful of the evil mages-Fistandantilus did not serve on the Conclave, fortunately-let out a snort, his wizened features contorting. Jorelia, on the side of good, shot the aged Black Robe an imperious look.

Vincil ignored them, his gaze never leaving Leciane. “Marwort is dead,” he said.

Leciane knew she should have felt sadness at that news, but she did not. Indeed, if anything, she felt relief. Marwort the Illustrious had been a sore spot among the three orders. A White Robe of no small power, he had served in the imperial court of Istar for some forty years. At first; he had proved a capable emissary, but as the years passed he had come to side more and more with the Kingpriest against the wishes of the Conclave-particularly since the empire’s current ruler, the one they called Lightbringer, took the throne. Given the Lightbringer’s rejection of the Doctrine of Balance and his quest to destroy all evil in the world, the Black Robes understandably had come to loathe Marwort.

The Red Robes had been no more comfortable, for the place of those who followed the neutral path was uncertain in Istar these days. Even many who wore the White had been disenchanted with Marwort, a creature they could not control. When a Conclave appointed an ambassador, though, it was for life, so the archmages had had little choice but to wait for Marwort to die-something he had stubbornly refused to do. Until now.

It had been quick, Vincil said. A blood vessel in his brain had burst while he slept. That made it clear the Black Robes hadn’t finally carried out their threats to have Marwort killed. They would not have made it so painless-not when the regime he’d supported made a point of burning every dark-robed mage it could find. The White Robes had claimed his body, entombed it beneath the Tower in the Lordcity, not far from the Temple where he had served for so long. The Conclave, meanwhile, had convened to begin the important step of naming a replacement.

Leciane smiled, imagining what those “discussions” must have been like. Each order wanted the new ambassador to be one of their own: the Black Robes as an act of defiance, the White Robes for amelioration, and the Red as, perhaps, a bit of both. In the end, the White Robes would not accept a Black Robe ambassador to the Great Temple of Paladine, and the Black would not allow another White to take Marwort’s place, so Red was the compromise. Nobody was happy, to be certain-Ysarl’s grumbling and Jorelia’s glare made that much clear-but it was the only course that wouldn’t crack the orders’ tenuous solidarity.

“And so, Leciane,” Vincil concluded, “I have called you here. All know you are trustworthy and devoted to the Art. All know you will speak on the orders’ behalf, even if it makes those around you unhappy. After much discussion we have chosen you to represent us at the Kingpriest’s court.”

Leciane’s breast swelled. She did her best to hide her joy, but she could tell by the way the corners of Vinci1’s mouth twitched that he had spotted the gleam of pride in her eyes.

“I am honored, Most High,” she murmured. “I would think you might choose one of greater years, however. I am younger even than Marwort was when he first went to Istar. If I should prove a poor choice, you’ll be stuck with me there for quite a while.”

Ysarl of the Black chuckled at that, and Leciane shivered. She didn’t miss his meaning.

The dark mages would not suffer another displeasing envoy for long. If she crossed them, it wouldn’t be long before she found a viper in her bed or poison in her goblet. It had happened before, and only Vincil’s iron hand had kept them from doing the same to Marwort these past few years.

“We know you, Leciane,” Vincil repeated. “You have always been loyal. We trust you shall continue to be so, whatever may come. Do you accept this honor?”

They were all looking at her, all twenty-one of them, their eyes heavy with portent.

Leciane stood erect beneath their heavy gaze, and for a mischievous moment considered saying no. It might be worth it, for the look on their faces. In the end, though, they knew she would accept. With solemn grace, she lowered herself to one knee before the Conclave, her long hair spilling forward as she bowed her head.

“I consent,” she murmured. “Beneath the three moons, I swear I will do thy will.”

After, when the ritual was done-when the heads of the three orders had each extracted an oath of service from her and smeared her forehead with white ashes, red blood, and black soot-she went to Vincil’s study atop the North Tower and kissed him hard on the mouth when he opened the door.

That surprised him, his eyes showing round and white when she was done. She laughed, striding into the room.

The Highmage’s study was a wonder to behold, so filled with magic that the air all but sizzled. It raised the fine hairs on Leciane’s arms as she looked about the room. It was a comfortable place, tastefully appointed in Ergothian style, all dark wood panels and stone-tiled floors, padded armchairs and couches. Enchanted glass globes hung from the ceiling in silken nets, aglow with golden light; bookshelves lined the walls, groaning under the weight of thousands of tomes, scrolls and wax tablets. Unlike some mages, Vincil didn’t fill his study with gewgaws-there were no gaudy displays of magical jewels and wands here-but there were some interesting things: A blackwood staff tipped with a star sapphire leaned in the corner, and a jade orb stood on a pedestal, limned with green fire.

A wide lapis bowl filled with water sat on a table in the room’s midst. Seeing it, Leciane smiled. In her days as his apprentice, she’d often helped Vincil with scrying spells that let him see things happening a thousand leagues away. She walked over and dipped her fingers in it, rippling its still surface, then pulled them out, sucked them dry, and grinned at the Highmage “Nepotist,” she said.

He chuckled dryly. “Hardly. We’re not related.”

“And a good thing,” she said, laughing again as his dusky face grew darker still. “You know what I mean, though you need a new envoy, and you recommended me? I’m surprised the others didn’t call you worse.”

“They did,” Vincil said. He shrugged. “They know you too, though, Leciane. They know you’ll do what we ask of you, whatever the risk.”

Leciane had turned to admire a model of a sailing ship on a sideboard-a model enchanted so that its sails rippled as if under full wind, and tiny, illusionary sailors scrambled about its deck and rigging. Now she frowned over her shoulder at the Highmage.

“What do you mean?” she asked.

Vincil didn’t answer right away; instead, he motioned for her to follow, out onto a balcony that looked down upon the Tower’s grounds. Below, Wayreth’s forest stretched out on all sides, red-silver beneath the moons’ glow. Strange cries and growls rose from the wood, and a pair of winged wildcats skimmed low over the hissing leaves, either fighting or mating. The air was crisp, smelling faintly of musk. Vincil leaned against a railing of twined gold and iron, gazing over the mages’ enchanted realm. Leciane watched him, waiting for him to speak.

“Something is wrong,” he said, sighing. “I don’t know what, but there is a new danger in Istar. The others have felt it too. The Black Robes say it’s this Kingpriest, this Lightbringer, but…” He stopped, staring at his hands.

Leciane laid a hand on his shoulder, “You think it’s something else?”

“I don’t know,” he said again. His brow wrinkled with frustration as he looked out over the treetops. “I’ve tried and tried to divine what it is, but it is hidden from my powers. Still, I can sense it out there.”

She bit her lip. “This danger,” she murmured. “You think it threatens the order?”

Silently, he turned. Their eyes met, and Leciane’s insides tightened at what she saw.

She tried to remember a time when she’d seen Vincil frightened before. She couldn’t.

Shuddering, she bowed her head.

“All right,” she said. There was steel in her gaze when she looked up again. “Tell me what I must do.”

CHAPTER 4

The Lordcity of Istar went by many names. Istar the Mighty, Istar the Beautiful, Istar the Holy. It was all of these and more: the greatest city in all of Krynn, outshining such grand metropolises as Palanthas and Xak Tsaroth. A quarter of a million souls dwelt within its soaring, gold-chased walls, spread out over seven hilltops along the northern shore of the shining waters of Lake Istar. It was a city of delicate towers and mighty arches, broad plazas and lush gardens, alabaster domes and gleaming mosaics, fountains and statues of lapis, serpentine, and bloodstone. Its streets, markets, and wine shops teemed with folk from all over the empire-towering natives from the Sadrahka Jungle, stout highlanders from the hills of Taol, slender, graceful Dravinish ladies, all dressed in a riot of colors and making an incessant din of shouting, song, and laughter. Exotic smells-spices and citrus, camphor and jasmine-filled the air, mingling with the music of dulcimers. The sight of Istar from afar had been known to bring even the grimmest warriors to tears.

To Cathan MarSevrin, it was home.