Omega: an apocalyptic rumour from the Eastern Front.

Omega: something that will alter all the strategic calculations of the Earth’s great military blocs.

But if Omega is indeed the agent that will destroy the world, that world is not our own. For this is a timeline in which World War Two never truly ended: a timeline in which Hitler died in a plane crash, Britain joined Germany in its battle against Communist Russia, and the present is an age of intermittent, but deadly, armed conflict between the USSR, the European Alliance, and the USA. The frontier regions are radioactive wastelands, nuclear winter threatens catastrophe, global confrontation could erupt again any time—and that’s Omega is taken into account…

This is the reality experienced by Owen Meredith when an accident forces his consciousness from the England we know into the mind of his cognate self in that other darker, Europe. Switching back and forth between being plain Owen Meredith and troubled Major Owain Maredudd, Owen is faced not only with a Cold War going Hot, but with a deep crisis of identity. Who is he? Whose twisted destiny is he treading? Did the ordinary domestic life he remembers ever even take place? Perhaps the universe of Owain and Omega is merely a symptom of mental illness—but if so, why is it so urgently tangible?

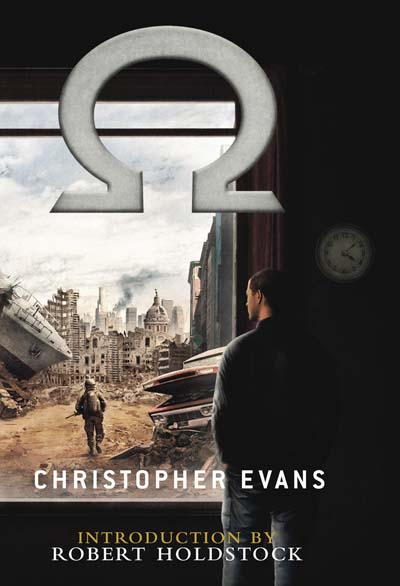

Christopher Evans

OMEGA

Enter the SF Gateway…

In the last years of the twentieth century (as Wells might have put it), Gollancz, Britain’s oldest and most distinguished science fiction imprint, created the SF and Fantasy Masterworks series. Dedicated to re-publishing the English language’s finest works of SF and Fantasy, most of which were languishing out of print at the time, they were – and remain – landmark lists, consummately fulfilling the original mission statement:

‘SF MASTERWORKS is a library of the greatest SF ever written, chosen with the help of today’s leading SF writers and editors. These books show that genuinely innovative SF is as exciting today as when it was first written.’

Now, as we move inexorably into the twenty-first century, we are delighted to be widening our remit even more. The realities of commercial publishing are such that vast troves of classic SF & Fantasy are almost certainly destined never again to see print. Until very recently, this meant that anyone interested in reading any of these books would have been confined to scouring second-hand bookshops. The advent of digital publishing has changed that paradigm for ever.

The technology now exists to enable us to make available, for the first time, the entire backlists of an incredibly wide range of classic and modern SF and fantasy authors. Our plan is, at its simplest, to use this technology to build on the success of the SF and Fantasy Masterworks series and to go even further.

Welcome to the new home of Science Fiction & Fantasy. Welcome to the most comprehensive electronic library of classic SFF titles ever assembled.

Welcome to the SF Gateway.

INTRODUCTION

Omega opens with a shock; a literally explosive start to a story set in two worlds. Our narrator, Owen Meredith, is the victim of the bombing in our cosy, contemporary London. He’s the producer of Battlegrounds, a CGI television series recreating old battles, and a very popular programme. Recovering in hospital he begins to learn that his personal world is not the world he remembers.

At the same time Major Owain Maredudd, in a brilliantly drawn wartime London of the 21st century, is also the victim of an explosion. But this time the source of the attack is a mystery. How eerie to have the whole of Soho a militarily guarded “forbidden zone”. Nelson’s Column topped by a gold eagle rampant!

But of course, we are in Chris Evans’s territory. The confusion and interaction of alternatives that Chris always does so well; here, with this new novel, and in past tales.

Chris is excellent at evoking a constant atmosphere of mystery, of uncertainty. Everything is clear—but is everything as it seems? As the two worlds run in parallel, the mysteries are different but oddly reflective of each other. We are constantly asking how the characters are being manipulated, and to what extent the reader is too.

And when Owen and Owain start becoming aware of each others’ worlds, we are in for a mind-game to take the breath away.

Both men are examples of a character trait that Chris does well: the displaced man, characters in search of their true ground. Perhaps this is how the author himself felt when he left a valley in Wales for the cold sprawl of London. Perhaps it is not. In any event, it’s a theme that often crops up in Chris’s work.

And displacement is at the heart of Omega in several forms; and “Omega” itself is at the heart of it.

Chris Evans writes slowly and carefully and it shows in the incredible detail. He is also very strong on character. Though Owen and Owain are the same man, he shows the similarities in character as human and the differences caused by their individual situations. And the same goes for the women in the book. Chris is very strong on female characterisation. They inform his stories with power and insight.

Omega is very much a story of relationships, from love, to authority; from brothers, to deception. But the most intriguing relationship in Omega is that between Owen and Owain, as each man becomes aware of the other.

The dark world of Major Owain Maredudd that Chris explores is packed with facts and references, political and military. It’s tempting to redraw the political map of the world based on this section, the different alliances, the different war zones—America encroaching on Australian Pacific territory, statues of Field Marshal Montgomery celebrating his landings along the Baltic in 1943! Owen, in this world, would have a field day with his tv programme! The astonishingly vivid sequence set in Russia, in Major Owain’s war-torn continent, certainly takes Owen to a battleground.

Omega is a story of dark, deep, sometimes desolate but always hopeful alternatives. We run our lives alongside the “what might have been”. We run those lives with compassion. And with humour. And with the persistence of love. Omega is two stories, both very human, both addressing the harsh realities of a world of this age and this time: one recognisable, the other sinister. We are invited to sympathise with both sides.

I met Chris thirty years ago and we found we had much in common in our attitude and desires for what we wished to achieve from our writing, even though we were very different writers. We were both published at the time by Faber and Faber. His first novel was Capella’s Golden Eyes. In the early and middle 80s we enjoyed a little “time off”, co-editing a writer’s magazine (Focus)and three volumes of stories, Other Edens, which featured early work by some now well-known authors in the field.

But importantly, Chris went on to write The Insider—a, story of alien occupation in the most invasive of ways—and In Limbo. In Limbo, a story concerning “Carpenter”, a man in care after a nervous breakdown, contains some of Chris’s funniest and most personal writing in the second of its three sections. Intensely political though much of his work is, he is also a very wry observer with a great sense of humour. In Omega, for instance, Owen’s historian father is described as having a “prodigious appetite for disapproval. He had a special distaste for what he called ‘fantasists’—historians who did not stick scrupulously to the facts but were prepared to speculate on alternative outcomes.”

After In Limbo, Chris produced a collection of related short stories entitled Chimeras. Again, they are set in a world we can recognise but which is not our own world. They deal with the process of creation, of invention, of the desire to fashion beauty in a place where beauty is both ubiquitous and yet absent. They are Chris’s take on the way we live in two worlds: that y ie real and that of the imagined—the creative process, another theme that fascinates him. Art, in these tales, is conjured out of the air: “creations deliberately fashioned with an excess of ambition so that they dissolved away within minutes of their emergence, leaving nothing but dust behind.” An eloquent comment on the ephemeral nature of “art for art’s sake”? And yet, in another tale, an artist of genuine talent is described as claiming that “becoming an artist had given meaning to his life. He wanted to leave behind something lasting. When he had difficulties with a creation, he would pause… focusing his imagination.” He would become as a “locked door.”

Imagination is fleeting, but it can leave dust or reality.

Chris spent his childhood in South Wales. Hard work, respect for family, the courage to challenge authority informs his writing, the mood of his writing, the passion of his writing; and indeed, the politics of his writing. In his 1993 novel Aztec Century he takes a huge chance by setting up a Britain as it might have been if taken over by a fascist state; but he twists the tale to make the conquering forces the Aztecs, in a world where the Spanish had failed to conquer them and the Aztec kingdom has become all powerful. By so doing he doesn’t just set two political regimes into conflict and contrast, as happened in the middle 20th Century; he deals with the confrontation of belief systems and the role and respect of two hierarchical societies, the brutality of such societies, where the notion of sacrifice is played for everything that “sacrifice” means.

I read a proof of Omega whilst on vacation. It was hot. Everything around me was lazy with ease. In the villa, I read a book that was dark and compelling, and which punched holes in the society that we have become. It is a story of two worlds, two men who are the same man, two lives that are entangled across a strange barrier. Chris often argues through fiction for an understanding of the way we live in a dual reality. Omega opens many doors, and there are scenes that are shocking in their truth and in their brutality. What Omega does very precisely, and very much for the time in which it is being published, is ask the big question about how we cope with our lives, how we deal with the dark, or the bright, that is in the lives of others; how we trust. And the question is both an alpha and an omega question.

PROLOGUE

I woke up in the back of an ambulance. Two men in short-sleeved shirts were standing over me.

“I’m sure I’ve seen him before” one said.

The other one leaned closer. “What’s your name?”

For some reason I grinned. It probably looked cheesy.

“Owen,” I mouthed. “Owen Meredith.”

I wasn’t sure whether the words had actually come out.

A gold Christmas-tree star hung from the roof, swaying with the movement of the vehicle. I tried to remember what had happened. An explosion. I’d been knocked over. The ambulance’s siren was wailing.

The man who had loosened my tie was asking me other questions, but I couldn’t hear him properly. Pain was blossoming in my head. Everything began to fade.

It was Lyneth who had insisted we take the girls Christmas shopping in the West End. We’d set off early, taking the train so that Sara and Bethany, seven and five, could peer excitedly at the industrial estates and wrecked car graveyards that lined the approaches to London Bridge station.

We spent a couple of hours in Covent Garden, where there were jugglers and mime artists to keep the children entertained, before lunching in the Piazza. Then it was on to Regent Street, Lyneth already having accumulated three carrier bags of presents by strategic strikes on selected stores while I shepherded the girls away from ice cream stalls and street vendors selling helium balloons of Winnie the Pooh and Harry Potter.

As Lyneth led the way down Regent Street I felt myself beginning to flag. We were headed for Hamley’s, where the girls had been promised an audience with Santa Claus. The pavements were thick with uncompromising shoppers. I clung on tightly to Bethany’s hand as we wove through the crowds, dodging buggies and squalling toddlers, pulling up sharply at intersections where traffic lurched out of side streets the moment the lights changed.

At the entrance to the store Lyneth stopped and marshalled us. She looked, if anything, fresher than when we had set out that morning, her bobbed blonde hair sprinkled with drizzle, her cheeks rosy, her eyes filled with the gleam of a good morning’s work already done, targets met, everything still on schedule. We’d met at school and had first gone out together when we were sixteen. Half a lifetime ago. So long a companionship only heightens those moments when you look at someone and see if not a stranger then someone whose familiarity is in itself strange.

Of course I can’t honestly say I thought anything of the sort at that moment. I remember only her standing there in her navy gabardine coat, putting her shopping bags down to wipe Bethany’s nose before straightening.

“Listen” she said to me in the considerate-yet-purposeful tone she always adopted when making a concession, “why don’t I take the girls inside while you pop off for half an hour and get something for Rees? A sweater or something.”

Rees was my brother, always a problem to buy for.

I grinned. “An hour would be better.”

She gave me a firm look. “Forty-five minutes at most. It’s going to be heaving in there.”

“OK. I’ll see you at the grotto.”

“There isn’t one. He does the rounds.”

“Then how will I find you?”

“Mobile, silly.”

This was Sara, always quick off the mark, just like her mother. I poked my tongue out at her and she responded in kind.

“Make sure you switch it on,” Lyneth said.

“Will do.” We had one each of course, so Lyneth could co-ordinate our movements in situations like this. She was always doing battle with my timekeeping and organisation.

I watched her take the girls inside before crossing the road at a red light and heading down a side street for a swift drink to restore myself.

I stood at the bar of a pub whose name I can’t remember, sipping a half. In the mirror I could see three men in their twenties sitting at a table. One of them was staring at me. Cropped hair, lots of muscles, a bit fearsome looking. He said something to the others and began making gestures in my direction. They looked blank. Before I knew it, he was at my side.

“You did that series, right?”

His accent was cod-cockney: grafted on, like a studied attempt at de-refinement. He was in his early twenties, a silver ring in one ear, his tight ribbed polo neck showing evidence of bodybuilding.

I nodded amiably.

“Battlezones, yeah?”

“Battlegrounds”

He shook his head as if he couldn’t believe it. “Those tank battles, man. Awesome.”

His lips were pursed in approval. I made appreciative noises.

“That Tiger tank—where was it? Same place as that submarine.”

“Kursk.”

“The way you took us inside, showed us what it was really like. The graphics were A-1. And that tank commander, he was a real hero. Six kills! He survive the war?”

“He wasn’t a real person. We generated the character from a variety of original sources.”

“You felt as if you were really in there, you know? All the controls, the bumping and hustle. You could almost smell the sweat and ammunition!”

“We wanted to make it as realistic as possible.”

“There going to be a PC game or anything? I’ve got Steel Storm and Red Star Rising, but I liked the intimacy, you know?”

I wondered how to reply to this.

“Excellent idea,” I told him. “I’ll talk to my brother. He’s the computer wizard.”

“You’d rake it in. What about another series?”

“It’s in the planning stage.”

“Yeah?” He plainly wanted to know more.

“We’ll be focusing on more recent conflicts—the Falklands, the Gulf, Bosnia, possibly Iraq.”

“You travel there? All those places? North Africa and stuff?”

“Some,” I said vaguely.

“I’m in the T.A. myself. Hitched a ride on a Challenger on Salisbury Plain one time.”

“Oh? Was it fun?”

“Nearly fucking choked from the exhaust fumes. Those things can really motor.”

I kept smiling, now a bit uncertain of the exact nature of his enthusiasm.

“Best thing I’ve seen on the box in years,” he announced.

“That’s great to hear.”

He was offering his hand. I took it and shook. His grip was firm and muscular, and he pumped my arm as if he was sending me off on a suicide mission.

“When’s it out on DVD?”

“In the spring. Lots of background info on how we did the simulations.”

“I’ll look out for it. You really opened my eyes.”

He returned to his table.

It was hard not to look in the mirror, to watch him enthuse to his friends. At the same time I’d learned to be wary of the enthusiasms of militaristic types. It wasn’t often that I was recognised and it still surprised me whenever it happened.

Battlegrounds had been broadcast in the autumn on Channel 5. The series had been given plenty of pre-publicity emphasising the use of state-of-the-art computer animation to give tactical and strategic overviews as well as more intimate portraits of the actual experiences of individual soldiers in major battles. Although it had been designed to appeal to a wide audience the scale of its success exceeded everyone’s expectations.

Battlezones. Now that was a title worth considering for the new series. It had a suitable ring of modernity to it.

I swallowed the last of my beer and departed with a mannered wave to the three men.

Five minutes later I slipped into Racing Green and emerged with a heathery V-neck. It was unlikely Rees would ever wear it, his style tending more to sweatshirts and ancient denims, but Lyneth had a mission to civilise him. Rees was a talented software designer specialising in graphical interfaces, and we’d employed him during the making of the series, so for once he wasn’t short of cash. But his personal life was a mess and he was presently living alone in a Peckham bedsit. Lyneth had invited him to spend Christmas Day with us. I doubted he would actually show up.

I spotted a gap in the traffic and sprinted across the road. Two things happened, one after the other. The mobile in my pocket started trilling and I instinctively paused to pull it free. An instant later there was an enormous bang that picked me up and hurled me backwards.

My head hit something—it may have been the body of a car—and I felt a blaze of enveloping pain. I saw the entire front of Hamley’s bulging outwards, dust blossoming and debris cascading down on the swarming street. Darkness swallowed me up.

What followed were snippets of disconnected impressions: the persistent squeaking of a trolley wheel as I was bundled down a corridor; Christmas greetings cards pinned around the frame of a notice board; distant voices blurring in and out of earshot; a taste of stale blood on my bloated tongue. The pain in my head was so intense that it dwarfed everything else, even my fleeting thoughts of Lyneth and the girls. I kept passing out and resurfacing before eventually settling into a more prolonged period of unconsciousness. When I finally woke again I was in another world entirely.

PART ONE

ALTERED STATES

ONE

The room was painted a duck-egg green. I lay in a dim light, in a wrought iron bed that was not a modern fashionable type but one of authentic age. My head was raised on a series of pillows with starchy covers. There was the smell of something sooty.

I risked a slight movement of the head, and felt a wave of pain worse than any headache. But it ebbed and I was able to inch myself up from the pillow.

A crimson patchwork quilt lay across the bed. Beyond the foot of the bed was a mirrored dresser on which a tasselled table lamp gave off a dull orange glow. The room looked utilitarian, but the furniture gave it a cosy feel. A computer sat on a drop-leaf table beside the door. It was not switched on, and someone had hung a crocheted doily over its screen. Next to the dresser an area of wall had been hacked out to make a fireplace where coals were burning low in a cast iron grate. Its bricked-in surrounds were crudely finished.

Had I been taken out of hospital? If so, to where? The room was quite unfamiliar to me, though in my drowsy state this didn’t bother me unduly.

The door opened, casting a swathe of brighter light into the room. A squat middle aged woman in a floral dress and black cardigan entered. She came to the bed and, seeing that I was awake, said, “There is water here for your thirst.”

She spoke gruffly, her English heavily accented. I tried to speak, failed.

She filled a tumbler from a glass pitcher on the bedside table, put one hand behind my back and sat me upright. Blood swirled in my head. When my vision cleared I saw that she was holding the tumbler in front of my mouth. She was stocky and swarthy and smelt of mothballs and stale sweat. Her dark eyes regarded me incuriously from what I found myself thinking was a peasant’s face.

I gulped like a child, the water dribbling down my chin. Finally she laid me back on the pillow and swabbed my chin with a scrap of cloth from her cardigan pocket.

“There, there,” she said, giving a gap-toothed smile. “That will be better, yes?”

For a long time after she was gone I just lay there, registering the unfamiliar surroundings with a kind of bleary curiosity. I began to make small movements, growing bolder when none provoked a renewed spasm of head pain. I threw back the covers. Swung my feet down to the floor. Slowly, very slowly, levered myself up until I was standing.

A dull throbbing in the head, nothing more. I glimpsed my nakedness in the mirror as I crossed the room to the window. I began cranking a handle to raise the blind.

Outside it was dark. No street lamps shone and there were no lights in any of the windows of the shadowy buildings visible across a snow-covered square. They were squat concrete fortresses of slit windows and angular walls, their roofs topped with radar dishes, artillery and missile emplacements. I knew them to be just the surface structures of an extensive underground complex housing all the administrative functions of the state. This was Westminster, the heart of a London I’d never seen before.

And I was in one such building myself, several floors above ground. A fleeting memory came of flying low over the city at night: I’d looked down on the coiled milky band of the frozen Thames, with dark lines of roads and clusters of buildings stretching away on either side. There were extensive areas of mottled whiteness between them. The city’s broken panorama was like a study in monochrome, a photographic negative of something that was familiar yet unfamiliar.

A dim reflection faced me in the window glass. It wasn’t me—not quite. A slimmer, harder-edged version of myself, with cropped hair and a more upright stance. An alter ego, staring back like a not-quite-identical twin.

I heard footsteps outside the room, felt my legs beginning to give way. Somehow I managed to get back to the bed, burying myself under the quilt, letting sleep wash over me like a benedicon.

TWO

All that night I dreamt that I kept waking to find myself lying in a modern hospital room, a monitor blinking off to my left. I was propped up under crisp cotton sheets, left alone in the suffocating sterile warmth. It was a fever sleep filled with confusion. At various times I saw two quite distinct women. The first, seated beside the door in the hospital room, was the same age as myself, dark auburn hair framing a sensuous and intelligent face. I couldn’t recall her name, though I knew we had once been lovers. At other times I was back in the green room, attended by a younger woman, sallow skinned and gamin, her black hair tied back in a ponytail. When I woke fully again I was in the wrought iron bed and a man in a white coat was standing beside me.

“Good morning,” he said. “Would you like some breakfast?”

A noise escaped my throat, something between a cough and a clearing of the throat.

“What time is it?”

This was an odd question under the circumstances, but it hadn’t really come from me. The voice was different from my own, huskier, with a stronger Welsh accent.

“Just after eight,” he said. “I’d suggest something light. Some cereal or toast. I’m Tyler, by the way. Sir Gruffydd consigned you to my tender mercies.”

He meant my other self’s uncle. I had an image of a florid, white-haired man in his seventies. A field marshal with a long record of service. His name was spelt in the Welsh fashion—I knew this without knowing how.

“Am I all right?” I heard myself ask.

“You were lucky,” Tyler said. “It’s probably just mild concussion and a few scratches. You should be up and about in a day or two.”

“Was it a bomb?”

“Not my pigeon.” He pulled down one of my eyelids and peered perfunctorily at it. I could smell the nicotine on his yellowed fingers. He was middle-aged, brisk in manner, a horseshoe of greying hair fringing his bald skull. He wore a taupe-coloured shirt and tie under his white coat.

“Any headaches or grogginess?”

“Not at the moment.”

“Other symptoms?”

“Like what?”

“Sleep disturbances? Nausea? Nightmares?”

“No. Nothing.”

This was said brusquely, a determined rejection of any admission that might be construed as personal weakness. It wasn’t me talking: it was my other self.

“Good,” Tyler said. “We’ll rest you up for twenty-four hours, put you on light duties for a couple of weeks.”

“I’m only just back from overseas. I’d rather be occupied.”

“Up to you. But don’t overdo it. Now—breakfast. What’s it to be?”

I realised that I had no appetite—or rather my counterpart had none.

“I never eat breakfast,” I heard him say. “A glass of orange juice would do, if there’s any.”

I sensed a craving for some freshly squeezed juice, like that available during his recent trip to Brazil, sharp and sweet and thick with pulp. There was little chance of it here.

“We’ll see what we can do. I take it you remember everything that happened?”

A sudden panic at this. He was blank. Then he remembered a blinding soundless flash, his car being consumed by it, though he was not inside it. He was hurled over as the shock wave hit him. A further memory of crawling through rubble before hands took him, helping him up into the back of a white van with the shield and crossed swords emblem of the Security Police.

“Of course,” he said. “There was an—”

Tyler put his hand up sharply. “Don’t tell me. Need to know basis. Wait till you see Sir Gruffydd.”

He checked my pulse, asked to see my tongue. It felt coated.

“I do believe you’ll live,” he announced at last. “Make sure you eat something. I’ll pop in tomorrow morning and give you a final once over. All right?”

“Yes.”

With this, he left.

I felt like a spy perched in someone else’s head, an invisible spectator to thoughts and speech and actions that came from within me yet did not belong to me. I was cohabiting, but with no knowledge of the life I had here except what I could glean from my counterpart’s reactions. The explosion that had injured him was not the one I remembered.

As soon as Tyler was gone, I got out of bed—or rather my other self did so. Still naked, he crossed to the mirror on the dressing table.

A cut above the right eyebrow was already healing, and there was no other sign of injury. He had a similar complexion and was about the same height and age as myself, though distinctly leaner. He staot the his reflection for a long time with an expression of mild consternation. It was like looking at a close relative, a brother, perhaps, yet he was someone I had never seen before. A thick growth of stubble did not disguise the pockmarks that covered his face from brow to chin. I assumed he had suffered badly from acne, though his thoughts remained resolutely closed to me at that moment. When he put a hand up to the mirror I saw crescents of grime under his fingernails and felt the cool smoothness of the glass.

An adjoining door opened on a narrow bathroom. It was unheated and chilly. The brass showerhead that sprouted from the white-tiled wall looked antiquated and encrusted with hard-water deposits. When he turned the tap there was a creaking noise, followed by a delay before tea-coloured water began spurting out. It soon cleared, though it remained tepid. To my alarm he twisted the lever to cold before climbing under it. The chill made him gasp with a mixture of shock and exhilaration that I felt myself just as keenly.

The soap was a mustard-yellow brick that stank of coal tar. He lathered himself vigorously, especially his groin and armpits. His body was wiry, with not a hint of spare flesh. I had the queasy feeling of being an involuntary witness to the intimate actions of a stranger. At the same time I was fascinated by the contrast between his habits and my own. I was used to hot showers in a heated bathroom. I’d fold a soft towelling robe around myself, whereas he began to rub himself down with a stiff off-white bath towel redolent of carbolic.

After this, still naked, he shaved, using a bristle brush, a stick of shaving soap and a single-bladed steel razor that sat on the shelf. There were other toiletries in plain white packaging. It was years since I had wet-shaved, and never with such a primitive razor. He was diligent, lathering thoroughly, stretching and contorting his pitted face as he slid the razor over it, paying scrupulous attention to the crevices under his nostrils and the line of his sideboards. There was several days’ growth to remove, and he made a great ceremony of it.

His eyes were a deeper brown than mine, his nose narrower, hair cropped in a short-back-and-sides that made no concessions to style. Abdominal muscles rippled as he did a series of stretching exercises in front of the mirror, taking deep breaths and exhalations. He had none of my incipient middle-aged flab.

His clothing had been draped over the back of an armchair in the bedroom—an army uniform in a greyish khaki. The jacket had shoulder patches showing the Union flag below a sky-blue diamond with a single five-pointed star in gold. It signified a major’s rank.

I knew this only because he knew it: the uniform was otherwise unfamiliar, and certainly not that of the present British Army. Under the chair were matt-black leather boots, fleece-lined. The closure strips had attachments resembling Velcro. A padded thigh-length combat jacket in pale winter-camouflage colours hung on the back of the door.

He donned his vest and underpants. Everything had been freshly laundered. I knew that he was intending to dress and go out, but suddenly he felt weak and sat down on the bed.

A tumbler of orange juice had been put on the bedside table while he was showering. He picked it up and drained it. The juice was thin and from a can; but it took the sour taste from his mouth. He rose again and went into the bathroom to brush his teeth.

The toiletries were his own: a bag bearing the initials O.M. sat on the shelf. I knew instantly his name was the same as mine. A plain white tube had FLUORIDE stencilled along it in black. The toothpaste tasted like mashed minted chalk, but he even scrubbed his tongue, probing so deeply I was amazed he didn’t gag.

As we emerged from the bathroom the woman entered. She was plainly surprised to find us out of our bed and in our underwear.

“What is this?” she said in her accented English. “No getting up yet! Back to bed.”

His inclination was to ignore her, but he couldn’t deny the weakness he felt.

“You will land us in bad trouble!” the woman said, scuttling forward and taking him by the elbow. “No getting up today. You must rest. Plenty of resting.”

He let her lead him back to the bed, though he insisted on getting into it himself. She tucked him in as one might do a child, though he noticed that never once did she look directly at him.

“Where are you from?” he asked.

“Here,” she said, folding under the bottom edges of the quilt. “I live here.”

“I mean originally.”

She gave no answer, still busy with the sheets.

“Are you Polish?”

She made a noise that sounded like an expletive, and left without another word.

THREE

The white hospital room. I was back. Through the window I could see dingy clouds scudding across a blue sky.

There was no sensation of transition. I had simply switched in an instant from one place to another. From another mind and body back to my own.

Unable to raise myself from the pillow, I felt both dull-witted and incredulous. I couldn’t begin to imagine what was happening to me.

I heard a rustling sound, managed to turn my head a little.

Tanya was sitting at the side of the bed.

Tanya! She was the auburn-haired woman I had dreamt was watching over me. Once, in our university days, we had been lovers.

She was wearing reading glasses, a hardback on her lap. Under her brown suede coat shewore a print silk skirt with calf-length boots. Her hair, cropped as a student, was now free-flowing to her shoulders but still the deep red-brown it had always been. She looked prosperous, but not showily so. Her very presence at my bedside meant something dreadful had happened.

Lyneth and the girls had been injured in the explosion, or worse. Tanya wouldn’t have been here otherwise. I had no family apart from my errant brother and my father, who was in a nursing home. Perhaps they’d been unable to contact Rees, who had a habit of dropping out of sight. Somehow Tanya must have heard the news and come to my bedside to be there when I woke. It had to be serious: of her own choice Lyneth wouldn’t have allowed Tanya anywhere near me.

Sara and Bethany. My mind rebelled at the very idea that anything could have happened to them. Perhaps they were all in intensive care, somewhere in the very same hospital, mere wards away. They would be clinging on to life, surviving as I’d survived. Or perhaps the girls had suffered minor injuries and were being tended by Lyneth while I recuperated.

I tried calling out to Tanya, demanding to know what had become of them. But nothing would emerge. Here, unlike in the other world, I had a distinct and proper sense of my own physicality; but my body was refusing to cooperate.

Could it have been a terrorist attack? A suicide bomber, even? Or something as banal as a leaky gas main? How many people had been caught up in the explosion? How many were dead?

My thoughts raced like pond skaters over the surface of these questions, but whatever drugs I’d been given muted my reactions to a dreamy bewilderment.

Tanya turned a page of her book. I willed her to look up, to notice I was awake. This wasn’t happening. I couldn’t allow it to have happened.

“So,” said a gruff male voice, “you’ve been playing with fire again, eh?”

My uncle was short and stocky, with a genial expression on his rubicund face. His epaulettes and scarlet gorget collars bore the insignia of his rank, gold oakleaf embroidery enclosing wreathed batons, a lion rampant within its ring of stars. He pulled a chair up to my bedside and gently pushed me back when I tried to sit up.

“No, no, just lie there,” he said. “The doctor tells me you need to have a good rest, so let’s not have any standing on ceremony.”

I had the immediate sense that he was speaking in another language, lilting and glottal. Apart from a smattering of French, English was the only language I knew, yet I understood him perfectly.

He put my hand between his own, grasping it firmly, his eyes becoming a little glazed. A man of sentiment, despite his status. Protective of family members.

“I was worried we might have lost you,” he said. “A bad business, Owen. A bad business, indeed.”

He pronounced the name O-wine—the Welsh way, I realised. It was the language he was speaking. Presumably it would be written Owain. Yet I, born in Swansea but raised both there and in Oxford, had never learned it.

“Second time around,” I heard myself say, also in Welsh. “Someone up there must like me.”

The field marshal released my hand. “It’s no joking matter, my boy.”

I looked at him through Owain’s eyes with a certain degree of awe: Sir Gruffydd Maredudd, the commander-in-chief of the Alliance armed forces in the United Kingdom and head of the Joint Governing Council, the body that had superseded a defunct Parliament in the conduct of the nation’s affairs. At the same time I knew that in my own life I had never had an uncle by that name, let alone an ennobled senior military commander.

“What exactly was it?” Owain asked. “A missile?”

“What do you remember?”

Owain thought about it. His mind was empty.

“Take your time,” his uncle said firmly. “Tell me everything you remember.”

He made a renewed effort to recall the details. Slowly they began to come.

He had just flown back from a three-week information-gathering mission to South America. His clearest memory was of the snow-camouflaged Bentley that had been waiting for him at Northolt, its driver a talkative Jamaican émigré called Maurice who had fled the American occupation of the Caribbean in the late ’fifties. Cheerful and patriotic, he had served in the old Royal Navy for twenty years. He lived in the Docklands and was looking forward to a family gathering at Christmas.

There was little traffic in central London apart from the usual convoys and patrols. At Oxford Circus an enterprising Sikh trader was selling straggly Christmas trees to the checkpoint guards. Regent Street itself was closed to civilian vehicles, but staff cars were invariably allowed the benefit of the shortcut.

As the barrier was raised for them, Maurice asked Owain if he could pull over and buy a tree. Owain had no objections: he saw an opportunity to stretch his legs after twelve hours of being cooped in various forms of transport.

They drove through and parked in the middle of the empty road. Taking his briefcase, Owain wandered down the street while Maurice returned to the checkpoint to barter with the trader.

Around Owain there was nothing but silence and abandonment. He was surrounded by the shells of once-thriving commercial outlets. On the western side they had been emptied and bricked-up; on the eastern side only reduced façades remained like the half-ruined outer keep of a castle. The entire area of Soho beyond had long been off-limits to civilians, sealed off and plastered with biohazard signs after an anthrax attack thirty years before. His mother had brought him here as a six-year-old to see the Christmas lights and watch a special broadcast from the troops in Persia, where his father was serving. He’d searched the assembled faces in vain for a glimpse of him.

An almost subliminal hum was coming from somewhere. It grew in volume, like the approach of an insect.

“Major!”

He turned and saw Maurice hurrying back to the car, triumphantly flourishing a stunted and bedraggled tree. The hum rose in volume and frequency, ceasing an instant before a flood of white light surged through the gaping windows and balconies of the façade, swamping everything and sending him reeling.

“It was like a massive flare,” he told his uncle. “There was no noise.”

It felt like a confession, an admission of guilt.

“What possessed you to go down there in the first place?”

He thought that he’d already explained it. “I was thinking about mother.”

The field marshal gave a grunt of consideration and undisguised sadness. Owain’s mother had died with other family members when the water supply at their estate in Brecon was contaminated with cholera. Easter 1984. Owain and his brother Rhys only escaped because they were still in boarding school in Aberystwyth. It turned out that the well on the estate had been infected with chlorine-resistant bacteria by religious disarmamentarians who were subsequently shot for their pains.

Their father was serving overseas at the time, while his uncle, newly promoted, had been summoned to London because the Soviets had launched a new offensive in the east. To minimise the risk of infection, he and Rhys were only allowed to view the bodies from behind a glass screen before they were cremated. Now their father too was long gone, leaving just the three of them.

“The driver,” Owain said. “Is he dead?”

Sir Gruffydd shook his head. “Knocked over. Shaken up like you.”

“It came out of Soho,” he said.

“Derelict ground, fortunately.”

“What was it?”

His uncle shrugged. “The CIF unit that went in reckon it was a big incendiary, nineteen-seventies vintage. Been lying there for donkey’s years. Could have gone off at any time.”

The CIF were the Counter Insurgency Forces, always sent in if sabotage was suspected. Owain remained puzzled. “I didn’t hear any explosion. Just a rising whine, almost like a jet engine. And a big flash of light.”

Sir Gruffydd didn’t look surprised. “You never hear the one that has your name on it. You were fortunate it didn’t kill you.”

There was something in his uncle’s tone that made Owain wonder if he was withholding harsh facts. Or perhaps it was sheer relief.

“Were there any casualties?”

“Indian chap. Street frontage above the old station collapsed on him. Apparently the epicentre was right behind it.”

Owain couldn’t work it out. “That would have been north of me. It felt like the flash came from due east.”

The field marshal looked unconvinced. “I got the report this morning. Very thorough in these matters, Legister’s legionnaires.”

He was referring to Carl Legister, the Secretary of State for Inland Security. Legister was responsible for anti-terrorism and civilian order on the home front, in charge of both the Security Police and their quasi-military offshoot.

“I don’t understand,” Owain persisted. “It was so bright. One big flash.”

“Maybe it had a magnesium fuse,” his uncle said with the merest hint of impatience. “Maybe it was a white phosphorus charge.”

The mention of phosphorus instinctively made Owain think of his pockmarked face. There was also another more powerful memory that he immediately quashed. It was something to do with his service on the eastern front. He had ended up being invalided home the previous spring.

His continued scepticism must have shown because his uncle said, “It’s dead ground, Owain. Who would want to target it with a missile? We’ve not had a strike on London in over a decade. Count your blessings. You were fortunate it wasn’t anything nuclear or biological. They’ve given you a clean bill of health on that score. Nothing nasty lurking in the system. Physically speaking.”

The last two words were significant. Owain knew his uncle was still concerned he might be suffering after-effects from his combat experience.

“Don’t let it gnaw at you,” the old man admonished. “Trauma makes it easy to misremember the details. You’re still recuperating, and at least you’ve got youth on your side. Wait until you’re my age. Without my valet I’d have a job finding my shoes in the morning.”

His uncle plainly wanted to get off the subject. Perhaps it was what he’d been told: just an old bomb. Owain made himself smile.

“What happened to my report?” he asked.

“Your briefcase was recovered undamaged. I read it over a mug of cocoa last night. You did a thorough job.”

The generals had sent him to neutral Brazil, where he’d met Alliance agents and liaised with various representatives of the US armed forces. His instructions had been to glean more information about American intentions in the central Asian and Pacific theatres. But an air of guarded reticence had dominated all his meetings with his opposite numbers in the US armed forces: nothing was being volunteered. While there was no suggestion that the Americans were preparing renewed offensives on the Northern Indian or Chinese fronts, Owain felt a distinct chill in the diplomatic air. In his report he’d concluded that the laissez-faire approach that had served both sides so well for half a century was now being strained by the overlap of respective spheres of influence.

The strange thing was that the tour already felt remote, like something he’d done years ago. His uncle’s almost offhand reaction to his report made him wonder how much importance he actually attached to it.

“Was the driver on your staff?” Owain asked.

His uncle nodded. “One of our regulars. Very reliable. They discharged him after a couple of days. In time to cut the turkey. I had one sent him specially.”

“Christmas is over?” Owain said. “How long have I been here?”

“Only a few days. We had you in the Berlin Memorial to begin with.”

It was the main military hospital in the capital. Owain’s shock mirrored my own. I wondered if he could sense my presence. He gave no sign of it.

“In hospital?” he said.

“They didn’t tell you? You were in a coma for the first forty-eight hours. Then you woke up raving until they tranquillised you. You were out of it for ten days. We had you transferred here when the crisis passed.”

He was in the surface apartments of the War Office. No wonder the old man was concerned that he might have been hallucinating. “I don’t remember any of that.”

“We had to be sure you hadn’t picked up something, but there were no indications. Just a nasty knock to the head.”

The time between the explosion and the final waking was a complete blank. I knew that a similar period must have passed in my own world.

“Tyler’s a good man,” his uncle said. “He thinks you’re over the worst.”

“I’m fine,” Owain assured him. “A little weak at the knees, that’s all.”

“That’s only to be expected. You don’t look too bad for a mongrel.”

The usual actionate tease about his mother, who had been English. He had only the fondest memories of her, but had been devoted to his father, who’d died in Palestine when Owain was sixteen. Not that he’d seen much of him during those years: his father had served overseas even before he was born and was rarely home on leave. Owain and his brother had been raised on his uncle’s estates in mid-Wales, learning Welsh during the vogue for encouraging regional cultural identity. They had even de-anglicised their names. It proved just a fad, but the language was useful for conducting private conversations since few other people spoke it.

“I’d like to return to my duties as soon as possible,” he announced.

The field marshal looked stern. “I’m sure you would.”

“Sir, I’m fine.”

“Of course you are. But you’re going to wait until the plasters come off.”

Owain didn’t demur; he felt weaker than he had actually admitted.

“Well, my boy,” Sir Gruffydd said, rising, “can’t sit here chatting all day. You know the drill.”

“I appreciate you coming, sir.”

His uncle squeezed his shoulder affectionately. “You’ve had another narrow escape, Owain. Third time might not be so lucky. Go easy on yourself. That’s an order!”

FOUR

A muddled memory of my own life:

I was sitting in a small viewing theatre, watching a preview of the first episode of Battlegrounds. We’d made eight programmes in all, the aim being to recreate the soldiers’ experience of the major land campaigns in Europe and North Africa. For over a year I’d travelled widely, ranging from Norway to Normandy, Libya to Latvia and beyond. The split screen showed me in a T-shirt and jeans, walking a tranquil stretch of desert, backdropped by a computer simulation of German infantry men in a sandy dug-out, under bombardment from the barrage that had opened the final battle of El Alamein.

Lyneth and both the girls were with me. Sara sat cross-legged, watching with wide-eyed seriousness her father up there on the screen. It was the first time any of them had seen the programmes, and I remember feeling peevish towards Lyneth, who spent the entire hour with Bethany huddled on her lap while she flipped through picture books to keep her occupied. Ever the practical one, she’d even brought a small pencil torch for the purpose. I had hoped that at last she would show some interest in my work and acknowledge my achievements. This was, after all, my finest hour. But she kept her head down as she read the books to Bethany in a secretive whisper.

The faint glow of the torch highlighted her flawless complexion and the intense concentration she was putting into the task. She didn’t look up once to sh my small moment of glory. I felt a surge of irritation and affection in equal measure. I wanted to snatch the book from her hands and demand she pay me some attention. I wanted to turn the lights on so that everyone else could see what an excellent mother she was.

The dream was vivid, even though it was the merest snapshot, a true reflection of my ambivalent feelings. But a malignant fantasy intruded and my father was sitting there, the serious professional historian who was gazing at the screen with open contempt.

I surfaced in the wrought iron bed. Back in the body of my other self, Major Owain Maredudd, he of the ravaged face and guarded thoughts. He had lurched upright as though rising from a nightmare.

His body was filmed with sweat, the sheets tacky against him. A pale wintry light seeped through the open curtains. The room was filled with the emphatic ticking of a carriage clock. It had been placed on the dresser and showed two-fifteen.

Owain went into the bathroom. He took another cold shower, which again I endured with far less fortitude than he. After vigorously rubbing himself dry, he began to dress.

I tried to will myself back to my own world. This time I couldn’t sense the undercurrents of his thoughts and memories. He’d shut down, as though in reaction to whatever dream had disturbed him, and was narrowly focused on the here-and-now. I felt mentally press-ganged, hemmed in. But I couldn’t escape.

He stood before the mirror, buttoning his tunic to the neck, checking that he looked presentable. His eyes were shadowed and he hadn’t fully recovered his strength; but I could feel his determination to leave the room. He picked up a leather wallet and flipped it open, staring at his ID card as if he needed to verify his own existence.

He tucked the wallet away and retrieved his belt from the bedpost. It held a canvas-holstered hand pistol which he did not remove, though I gleaned that it was a 9mm Walther APS with a twenty-round magazine, standard Alliance Army issue.

A padded jacket hung on the back of the door. It was lightweight, the fabric waterproofed, closures sealed with what here were called dryads, for dry adhesive strips. There were gloves in one pocket, a furlined hat with earflaps in the other.

A carpeted corridor led to a landing where a swarthy female MP was on duty, her black hair tucked up under her forage cap. Owain knew her by sight if not by name.

“Sir?” she said uncertainly.

“I’m going downstairs,” he told her. “Stretch my legs.”

He went past without saying anything further, taking the stairs at a brisk pace but holding on to the handrail.

The stairs debouched on a broad marble hallway that had been partitioned so that it could function as offices. The place was a bustle of clerical activity. An oriental woman sat at a desk piled with box fs; a boy barely out of adolescence was clattering away on a bulky manual typewriter, pausing to scrutinise a document through thick-lensed spectacles.

Owain walked swiftly through the centre of the workspace, almost colliding with a Nilotic man who was talking loudly down a telephone. I gleaned that electronic communications had been severely disrupted for several months, though the thought was quickly stifled.

A pair of steel doors gave access to one of the stairwells. He went down two floors to the lower ground floor, where the vehicle ports were located. But someone was waiting for him on the landing.

“Good morning, major,” she said. “Up and about already?”

She was a dark-haired woman in her mid-forties. Lieutenant-Colonel Giselle Vigoroux, his uncle’s military secretary, a permanent member of his personal staff. Evidently the MP had phoned down, and good for her.

“I was bored,” he said. “How long can you lie in bed when there’s nothing wrong with you? I needed a breath of air, a little drive.”

She smiled at him in a knowing way. She wore her hair short but in a stylish cut which made her cap no more than an accessory to it. Despite the uniform there was always something casually elegant about her.

The pager on her belt started bleeping. Gently she drew him in through the open doors of the service lift. The doors slid shut.

Owain was nervous of lifts but determined not to show it. They were descending into the subterranean heart of the complex. Most of the building above ground was given over to routine administrative tasks; all the important activity was carried out deep enough down to be proof against enemy attack.

Finally the lift stopped and the doors trundled open, admitting a waft of warm, stale air. A short corridor led to another pair of doors. There were signs on them saying AUTHORISED PERSONNEL ONLY in a dozen different languages. Giselle slid her ID card into a slot and pressed digits on a keypad. The doors parted, releasing a wave of even warmer air.

“Your uncle’s not here at the moment,” she told him as she led him through.

“I wasn’t aware that I’d need his permission to go out.”

“I was told you were still convalescing.”

“Does that make me a prisoner here?”

He was pushing it, he knew, and with a woman he liked and who was extremely good at her job. She merely laughed.

“Are you fit enough to go driving?” she asked.

“I wouldn’t be asking if I wasn’t.”

They had entered a room with metal walkways surrounding a large central well. Attentive staff sat before monitor screens, while above them animated maps showed swathes of eastern Europe, the Middle East and the Pacific islands in electric primary colours. The displays were constantly changing as if searching for a static equilibrium but never finding one. Here, deep below ground, the equipment was securely shielded from the electromagnetic interference that plagued surface transmissions.

“You’ll have to excuse me a moment,” Giselle said, and promptly disappeared down one of the walkways.

The large well below was dominated by a softly-lit area with dark banks of machines arranged around it. I knew from Owain that this was AEGIS, the automated tactical and strategic defence network that had been used by the Alliance to direct their military operations for the past quarter of a century. It was part of a network linked to sites in Paris, Hamburg and elsewhere. The Russians had their own equivalent, as did the Americans. All three had been seriously reduced in their operational efficiency following a catastrophic breakdown of the satellite systems on which so much of their data gathering depended. Or so it was said.

One of the TV screens was showing footage of the Chancellor touring the vast concrete fortifications of New Jerusalem. A handsome middle-aged man in his customary dark suit, he was an electronic composite designed twenty years before as a permanent figurehead of the Alliance, immune to assassination, disease and ageing. The Silicon Chancellor, they called him, and he was held in greater affection than any of his flesh-and-blood predecessors.

Giselle returned and led him out of the room. Owain was grateful for the relative coolness of the concrete corridor as they walked back to the lift doors. She presented him with a set of keys.

“There’s a Land Rover out the back,” she said. “Canvas-topped. Make sure you’re back indoors before curfew.”

The lift doors were already open.

“Don’t do anything foolish,” Giselle added. “You know he’s worried about you.”

She meant his uncle. “I’m fine,” he said adamantly. “I just need to remind myself that there’s a world out there. Tell Sir Gruffydd I’m available for duty whenever he needs me.”

“Before dark,” she reminded him. “Otherwise my neck will be on the chopping block.”

My own instinct was to retort that the British preference was for hanging, but Owain wasn’t prone to such frivolities.

He was greatly tempted to take the stairs back up to the surface but knew it would be a foolish exertion in his present feeble state. He entered the lift.

As I stared at his smeared image in the polished steel wall of the lift I could sense his unease. To me he looked the perfetinldier; he had been raised to it from an early age. Yet he was filled with vague, restless insecurities, not least the nagging anxiety that the lift might at any moment fail and send him plummeting.

His relief was palpable when we emerged at the basement level. We passed down another concrete corridor and went through a storage area with crates piled high on cantilevered shelves. At its far end was a pair of clear plastic doors stuck with black-and-yellow striped tape for the benefit of forklift drivers.

The warehouse was quiet and deserted apart from two elderly men who were crouched around a paraffin stove, sipping a golden brown liquid from glass cups.

“Tea or whisky?” Owain called, surprised at his own levity, which had in fact been prompted by my own instinct to say something.

The men looked back at him with blank incomprehension. I relished a mild sense of victory in my brief display of presence, though I sensed Owain stiffening his control again with a feeling of having spoken out of turn. He viewed the comment as a lax outburst, a mild breach of decorum; he had no inkling I was the originator.

Beyond the doors was an extensive parking space for staff cars and All-Terrain Vehicles. Impacted snow crunched under Owain’s boots as he crossed to a sentry box where two MPs sat, playing cards. They rose and saluted.

He jangled his keys, having already spotted the Land Rover. One of the men waved him on. They’d been expecting him. No doubt Giselle had phoned through.

The vehicle was a left-hand drive of some vintage, the dashboard old-fashioned with its flick switches and analogue dials. He turned the key and the engine chuntered into life. Without delay he drove up the slip road and out onto Whitehall, driving on the right-hand side of the road.

The civilian traffic was sparse, a few long-serving trucks and vans rather than cars. An old double-decker bus went by, ferrying civilians. Its windows were missing and the flaking red paint on its coachwork was almost indistinguishable from the extensive areas of rust. It was followed by a taxicab hand-painted in white and grey, grilles encasing its side windows. A senior officer and a young woman were sitting in the back seat.

Owain drove slowly, in no great hurry. Knots of soldiers and civilians were gathered around the soup kitchens lining the approach to Trafalgar Square, steam billowing from big urns. They looked surprisingly cheerful and were busy bartering food items and medical supplies. A line of people waited at a bus stop, its pole mounted in a concrete-filled drum. The civilians wore all manner of hats and layer on layer of hand-me-down clothing. Most were clutching bulging bags of vegetables and firewood. Dirty snow had been piled on either side of the thoroughfare, barricading buildings with metal shuttered windows. Sandbags and barbed wire framed doorways and forecourts.

Overhead the sky was a marbled grey. Darkness was already beginning to gather. Owain switched on the jeep’s heating. He turned into Trafalgar Square, circling it in an anticlockwise direction. In place of Nelsons Column stood a weathered golden statue of an eagle rampant. The rest of the site had been levelled and was a parking space for snow ploughs and security police wagons. A Cougar battle tank sat in the colonnade of the National Gallery, pigeons perched on its 120mm gun barrel, its slab-faced armour zebra-striped. Soldiers and MPs manned checkpoints all around the square.

Owain drove on. There were frequent gaps in the street frontages that held nothing but snow-covered rubble. In places the dereliction was extensive. I saw no evidence of what I might have recognised as modern commercial architecture, no sleek high-rises of brick and glass, nothing that looked as if it had been constructed for any purpose other than to withstand a prolonged siege.

Halfway up the Haymarket Owain came to a checkpoint and was directed to pull over. He showed his ID card to an MP. It resembled a credit card, with profile and frontal head shots, a magnetic strip on its rear. The MP told him that if he was headed north he would have to go along Piccadilly and up Park Lane since both Shaftesbury Avenue and Charing Cross Road were presently closed to traffic. Effectively sealing off all the Soho margins, he thought.

“I’m headed west,” he said, the lie making his pulse surge.

He turned left into Jermyn Street, took a right, and found himself driving straight towards a full-blown roadblock. Temporary signs indicated a left turn only, which would force him west along Piccadilly, away from his intended destination. Instead he drove straight up to the razor-wire barrier.

Ahead of him hoardings around Piccadilly Circus carried patriotic posters featuring images of citizens and soldiers clone in a style that reminded me of Soviet heroic realism. One showed a multiracial group surrounded by a swirl of national flags and a scroll declaring: BROTHERS-IN-ARMS! Among the flags was a red, gold and black banner, its central band surmounted by a black Teutonic cross.

One of the soldiers from the roadblock approached the car. They were CIF men, equipped with Sterling submachine guns and snug hooded winter-camouflage body suits. This one held a senior guard’s rank, equivalent to a sergeant.

Owain surrendered his ID card. The guardsman swiped it through a hand-held scanner before frowning as if it wasn’t working. Or as if it didn’t check out.

“Can I ask where you’re going, sir?”

Owain decided to be direct. “I’d like to take a look at the bomb site.”

The man squinted at him, his eyes shadowed under the cowled brim of his helmet. “And which one would that be, sir?”

He had an Ulster accent; Owain had done a six-month tour of duty there while still an NCO. Suppressing extreme Catholic and Loyalist groups opposed to the Ecumenical Irish Republic.

“Soho,” he replied.

“I have no information on any bomb site, sir.”

“There was an explosion. A few days ago. I mean, a few days before Christmas.”

The man looked studiously blank. “I know nothing about that, sir. I’m afraid the area’s off-limits.”

He was scrupulously formal. Owain knew he wasn’t going to get anywhere unless he raised the stakes.

“Listen,” he said, “I was in Regent Street when it went off. Let me speak to someone.”

The guardsman’s face didn’t change. There were half a dozen of his colleagues at the barricade, all watching.

“Field Marshal Maredudd sent me over,” Owain said. “I’ve come straight from the War Office.”

Another glance at the scanner screen. “As far as I can see, there’s nothing here relating to site access.”

Owain essayed a shrug. “We didn’t imagine it would be a problem. Would I have driven up here otherwise?”

Once again the guardsman scrutinised him against the picture on his ID. “I’m sorry, colonel—”

“It’s major” he said. “Major Owain Maredudd. If I was a spy or a saboteur, you don’t really think I’d fall for that one, do you? Do you want my serial number and my mother’s maiden name?”

The guardsman had the grace to smile.

“Pull in over there,” he said, pointing to an area of waste ground on the corner of Piccadilly. “Oh, and sir?”

“Yes?”

“You might want to switch on your lights.”

A hard-topped truck and a Rapier armoured car were already parked on the waste ground, the latter standing with its view slits shuttered but its engine idling. Owain spun the Land Rover around and reversed into a space.

A blue haze of cigarette smoke was issuing from one of the vents in the armoured car. The guard had gone across to a female superior standing beside a long cargo lorry that was parked right across the entrance to Regent Street. Owain saw the woman look towards him before taking his ID and climbing into the back of the lorry. Cables were trailing from its rear into an open manhole on the pavement.

Owain waited, stamping his feet on the powdery snow, stretching his shoulder and neck muscles. A big RAF helicopter went by, the red-and-blue decal on its midsection enclosed by a circle of yellow stars. None of the personnel on the ground looked up as it went past.

The cles. opter was an Euro Avionics HT-11, I gleaned from Owain, popularly known as the Fishtail for its forked rear end. It was used as a vehicle and troop carrier, and Owain had flown in one many times, especially while on the eastern front. I had a brief image of him driving down a ramp from the belly of such a craft into a cold predawn darkness.

The woman emerged from the trailer. Her head was swaddled in a grey fur hat, the earflaps hanging loose in the wind.

“Good evening, major,” she said. “A raw day to be out and about.”

“Indeed,” Owain replied.

“Perhaps you’d like to sit in your vehicle.”

Was this a suggestion or an order? She had a unit leader’s patches, was roughly the same rank as him. But with jurisdiction. Owain decided not to make an issue of it. He climbed back into the Land Rover and wound down the window. He’d left its engine running.

“I’m here half the night myself,” she went on, turning his ID in her mittened hands. Owain was sure she had already checked it with the database. “The graveyard shift. Much rather be curled up in front of the TV with a mug of something hot.”

Owain was trying to place her accent. South African or Rhodesian, he decided; he didn’t bother to ask.

She was still holding on to his card. Owain drummed his gloved fingers on the steering wheel. He was beginning to regret having made his intentions explicit.

She reached in and extracted his wallet from the dashboard pouch. Removing a mitten, she replaced the card in the wallet.

“Well then,” she said, handing it back through the window, “everything appears to be in order. But it’s not going to be possible to visit the site.”

Owain was striving hard to control his impatience. “I just wanted to see what damage it caused. My driver and I were nearly killed. Check it for yourself if you don’t believe me.” He was certain she had already done so. “I’m only just out of convalescence.”

“You have my sympathies. But I’m afraid no one’s being allowed in without authorisation.”

“Look,” Owen said, “I’m Sir Gruffydd Maredudd’s adjutant. Do I really have to go back to the WO and get his signature?”

“That would be entirely appropriate. You would also need to make sure you’re suitably dressed. There’s a concern that the explosion might have stirred up toxins. My orders are to keep everyone out unless they have security clearance. You will appreciate that they have to be applied without exception.”

This was at odds with what his uncle had t

Owain inhaled sharply. I could feel his fury mounting, and his struggle to control it. It was an emotion unfamiliar to me, or at least long forgotten.

He rammed the gear lever into first. The woman stepped back.

“Lights on, major,” she reminded him. “I wouldn’t want to hear that you’d had an accident.”

Owain drove away, heading straight down Piccadilly. The night fog was already rolling up from the river. This decided him. Out of sight of the roadblock he turned sharply right into an unmanned intersection, driving parallel with Regent Street into Saville Row.

The district was lined with mouldering tenement blocks. The central area of London had suffered from repeated aerial attack over the last half-century and much of it was now depopulated. The buildings, raised hastily on bomb sites in the nineteen sixties, had long been abandoned, the factory workers dispersed to rural sites.

He turned into a side street, into a dead end. Big coils of razor wire had been piled against a breezeblock wall about ten metres high. Above the old yellow-and-black biohazard signs were new ones showing anti-personnel mine symbols. A stark warning in English, French and German said: ENTRY FORBIDDEN: INTRUDERS WILL BE SHOT

I could feel Owain’s powerful urge to investigate, regardless of any dangers. He switched off the Land Rover’s lights but left the engine running. I wanted him to stop, but my anxiety counted for nothing, wasn’t even registered. What would happen to me if he were killed?

The tenement blocks were all sealed off, their doors and windows long bricked up. Owain skirted the barrier cautiously. The razor wire had been laid in haste, thrown down almost casually against the base of the wall, the new signs hammered in with masonry nails. Flattening himself against the wall, he managed to slip past the wire without getting snagged.

The wall itself was at least twenty years old. There were gaps in the pointing, and hardened cement had oozed out like cream from a sponge cake. In one corner, ice from an overflow pipe had piled up, reducing the height by half.

Purposefully Owain began to root around in the snow. Amongst the broken bricks and the rotting cement bags was a pallet of unused blocks, abandoned and forgotten. He withdrew an army knife from his belt and cut off lengths of plastic packing strips before knotting them together into a crude lasso.

The overflow pipe projected from beneath the guttering on the corner of the tenement wall. He managed to hook the noose over it at his second attempt. He tugged several times; it held. Confident that his gloves would prevent the strips from cutting into his hands, he began hauling himself up.

All this was conducted with total concentration on the task. He had a more practical bent than me and was also much fitter. Despite not being fully recovered from the bomb blast, he scaled the wall effortlessly and perched on its lip.

He was just high enough to peer across the deserted street and over the broken frontages into the Soho wasteland. The fog was rapidly thickening, making visibility intermittent. But parts of the area were lit with fuzzy halos of arc-lamp light, and he was able to see the outlines of bulldozers and other earth-shifting equipment. They were moving about amid a tangled, lumpy landscape.

The drone of their engines carried to him. He glimpsed a lorry piled high with debris, driving away into the fog. A few figures were discernible too—men who looked as if they were wearing hardhats and coveralls rather than decontamination suits. Some were directing dump trucks; others were hitching rides on open-topped ATVs. The noise of a mini avalanche reached him as another unseen lorry received its load. Squinting harder he saw that the mounds comprised mountains of earth in which were embedded the broken outlines of heavy machinery parts.

The area was supposed to have been cleared years ago, but it looked as if it had suffered saturation bombing, everything churned up and mangled beyond recognition. He cursed the fact that he didn’t have binoculars and could only rely on murky impressions. But what was certain was that this was no decontamination team: on the contrary, as much of the ground was being turned over as possible.

A wave of giddiness swept over him. We almost went plummeting down. Another sound reached us: that of an approaching helicopter.

Again Owain cursed himself for leaving the Land Rover’s engine running: if it was a patrol craft it would be carrying heat sensors that could locate the vehicle.

He scrambled down the wall, sliding off the ice but landing safely. Edging past the razor wire, he stopped for a moment and listened. The helicopter sound was receding. He glimpsed it in the near distance, banking. It was going to come back his way.

He jumped into the Land Rover and reversed down the street, back into Saville Row. He headed south, only switching his lights on again as he made a westwards turn along Piccadilly.

I was amazed at his calmness, but his hands began to tremble. He peeled off his gloves and gripped the steering wheel tightly, his entire body swimming with a nervous exhaustion.

A vehicle was approaching from the opposite direction, its headlights blazing. It went past him without slowing, an old Army Saxon APC, reconditioned for Security Police use with a rear-mounted machine gun.

At Hyde Park Corner a street market was shutting up for the night. The area around it had been levelled. Owain turned south, winding down the window. We passed what had once been Buckingham Palace Gardens but was now snow-choked allotments that extended into Belgravia. The palace itself had been bulldozed half a century before following a direct enemy hit, the royal family reduced to a handful of survivors who were shipped overseas for safekeeping and were now dispersed around southern Africa and the American-occupied Caribbean. Their departure had only added more legitimacy to the new military government, wch already had its counterparts on the Continent. Fifty years later it was still in charge.

Owain went through a dense pocket of fog. He was driving too quickly. A T-junction materialised without warning. Mentally I lunged, attempting to wrench the wheel around. Brakes screeched, and a wall loomed in front of us.

FIVE

Two male nurses were lifting me into a wheelchair. One of them folded a blanket over my lap. I was pushed to a window and left alone.

Darkness had fallen, but I had a good view out over a rectangle of lawn with two wings of the building on either side. A modern redbrick hospital with row upon row of windows, cars going by on the road beyond.

I tried to lift myself out of the wheelchair, grasping the window ledge and levering myself up. I almost managed to straighten but the giddiness returned. I let go, for fear it might sweep me up and send me spiralling back into that shadow-world.

I lay half-twisted in the chair, my head filled with the pulse of my blood. Someone helped me sit up properly. Tanya.

Her renewed presence, and the sombre look on her face, made me think again that Lyneth and the girls must be dead.

I began raving at her, demanding to know what had happened. But again nothing emerged: I remained as limp and mute as a stuffed toy.

It had to be the medication. Or was I semi-paralysed? Brain-damaged? No, it was neither of these, I was certain. At least not in the conventional sense.

Tanya drew up a chair facing me and sat down. She wore the same brown suede coat as before, looked quite artlessly alluring. But although she sat only a few feet away from me, she might as well have been on the Moon because the rolling, sloshing sounds I could hear were coming from her. She was talking to me but I couldn’t make out a single word.

This went on for some time. What did I look like to her? A zombie? A drooling idiot? What was she trying to tell me? Something about Lyneth and the girls? She didn’t exactly look devastated, more concerned. This encouraged me. I was certain I’d seen only the front of the building collapsing in the explosion. Lyneth and the girls might have been at the back of the store. Possibly they had been injured by flying debris.

Suddenly I had an image of myself standing on sodden grass, watching as a coffin was lowered into a hole in the ground that had been cut square to accommodate more than one. I had no idea whether or not this was a true memory since I couldn’t actually remember anything else apart from Tanya’s previous visit to my bedside. But if Lyneth and the girls were dead they would probably have been buried by now.

No. It didn’t make sense. How could I have attended a funeral when I was still hospitalised and couldn’t even get out of bed without help? Tanya didn’t look pained enough. I had the impression she was more worried about me.

What had caused the explosion? Possibly she was telling me, but I was quite unable to comprehend anything. The idea that anyone would deliberately target a toy store was so repulsive it beggared belief.

I felt such a confusion of emotions. In embarrassment I managed to turn my head and look out the window again. The lawn below became a road, the redbrick hospital the metal-ribbed flanks of a bridge across which I was driving, my knuckles oozing lymph. Then I was back in the wheelchair again.

Tanya leaned forward to wipe my cheeks with a handkerchief that smelt of her perfume. She’d worn it as long as I’d known her, though I couldn’t recall its name. She scrutinised me in silence. This was unreal. Somehow I had to get a grip on things.

Tanya dragged her chair closer and took hold of my hands. She was talking again, and I could tell from her expression that she was insisting that I concentrate. Nothing she said made any sense. The sound of her voice grew higher pitched, became a buzzing that I thought was going to make my head explode.

At this point she did something astonishing. She leaned forward and planted a kiss on my lips.

It was a gentle but unreserved kiss. She hadn’t kissed me like that in years, since our salad days at university when everything had been new and we couldn’t keep our hands off one another.

She drew back and looked closely at me. I couldn’t imagine what she was thinking.

SIX

Owain had produced a torch and was climbing a stairway that zigzagged up the outside of the building.

He emerged on to a broad balcony with a view to the west. The building lay on the south bank near Westminster Bridge, itself an unfamiliar utilitarian structure of girders and thick wooden beams. In the darkness across the frozen river I could see the huddled fortresses of the state. They looked like a latter-day version of an ancient temple complex, but dedicated to their own hermetic ceremonies rather than the lofty aspirations of worship. A deserted park of sinuous walkways and barren trees occupied the site of the Houses of Parliament.

I tried to wrench myself free of him, to hurl myself back to my own world. It was another unwilled and unanticipated transition, a seamless shift from the warm aftermath of Tanya’s kiss to the bitter-cold outside air. I didn’t want to be there. I wanted my own life, as fraught with confusion and uncertainty as it was. How else was I going to find out what had actually happened?