Two children are found dead in a basement. Four years later their murderer escapes from prison. The police know if he is not found quickly, he will kill again.

But when their worst fears come true and another child is murdered in the nearby town of Strengnas, the situation spirals out of control. In an atmosphere of hysteria whipped up by the media, Fredrik Steffansson, the father of the murdered child, decides he must take revenge. His actions will have devastating consequences. As anger spreads across the whole country, the two detectives assigned to the case – Ewert Grens and Sven Sunkist – find themselves caught up in a situation of escalating violence.

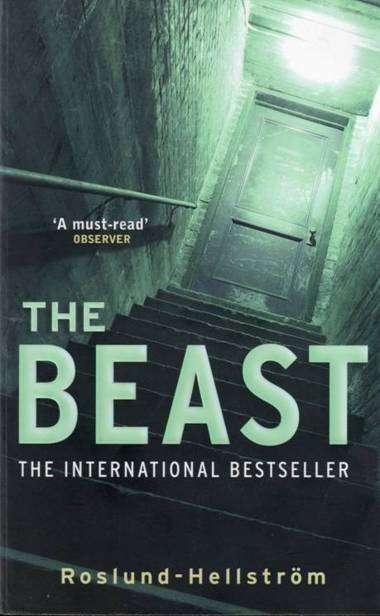

A powerful and at times profoundly shocking novel, has been likened to both Hitchcock and le Carre. It is also an important and timely exploration of what can happen when we take the law into our own hands. It has been shortlisted for Glasnyckeln 2005 (The Glass Key 2005) for Best Scandinavian Crime Novel of the Year.

Anders Roslund and Börge Hellström

THE BEAST

SOME FOUR YEARS EARLIER, PROBABLY

He shouldn’t have.

They’re coming now. There they are.

Walking down the slope, past the climbing frame. Twenty metres away now, maybe thirty. They’ve reached the plants with red flowers. They’re like the ones at Säter secure unit, near the front door. He guessed they were roses. Or whatever.

He shouldn’t have.

It doesn’t feel the same afterwards. Not so strong, it’s like the sensation’s gone.

There now. Two of them, walking along, their heads close together, talking. They’re friends, it’s easy to spot. Friends talk in a special way, using their hands as well.

It seems the dark-haired girl is in charge. She’s a live wire, wants to get everything said in one go. The blonde one is mostly listening. Maybe she’s tired? Maybe she’s a quiet one, who never talks much. Quiet ones don’t need their own space to feel sure they’re alive. Maybe one is dominant and the other one dominated. Isn’t that always the way?

He shouldn’t have wanked.

Still, that was then, this morning, twelve hours ago. It mightn’t matter now. The effect might’ve gone.

He’d known it first thing, as soon as he woke up, known that everything would work out tonight. It’s Thursday today, and it was Thursday the last time.

It’s sunny and dry today, and it was sunny and dry the last time.

They’re wearing the same kind of jacket. White, thin material, like nylon, a hood dangling at the back. He’s seen lots since Monday. Both have small rucksacks hooked over one shoulder. They all carry rucksacks, all their stuff’s in a mess inside, they’ve just thrown it in. What’s the point? Weird.

They’re close, so close he can hear them talking and laughing. They’re laughing together now, the one with dark hair laughs the loudest, the blonde is more cautious, not anxious or anything, she just doesn’t need the space.

He had dressed with care. Jeans, T-shirt, baseball cap worn back-to-front, that’s something he has noticed, he’s been watching the kids in the park every day. They wear caps like that, with the visors round the back.

‘Hi there!’

They’re startled and stop. It’s suddenly very quiet, the kind of silence you get when an ordinary noise ceases and your ears are forced to listen out. Maybe he should’ve done an accent, like he was from down south. He’s good at accents and some of them pay more attention. It sounds important somehow. Three days he spent collecting local voices. People here don’t have a southern accent. Or a northern one; folk are into proper Swedish in this place. No drawly vowel sounds, nothing like that, not much slang either. A bit boring, actually. He fiddles with his cap. Turns it right round, pushes it down more firmly over the back of his neck, still back- to-front.

‘Hi there, kids. You allowed out this late?’

They look at him, then at each other. Ready to move off. He tries to relax, leaning lightly against the back of the bench. What’s it to be? An animal? A squirrel, or a rabbit?

Or a car? Or even sweeties? He shouldn’t have wanked. He should’ve prepared himself better.

‘We’re going home, if you must know. And we are allowed to be out this late.’

She knows she mustn’t talk to him. She has been told not to talk to grown-ups who’re strangers.

She knows it.

But he’s not a grown-up, not really. He doesn’t look like one. Not like most of them, anyway. He’s got a cap on. And he doesn’t sit like a grown-up, they don’t sit like that.

Her name is Maria Stanczyk, the surname is Polish. She’s from Poland, or rather, her mum and dad are. She’s from Mariefred.

She’s got two sisters, Diana and Izabella. They are both older than she is, practically married. They don’t live at home any longer. She misses them, it used to be good having two sisters around. She’s alone with Mum and Dad now, it’s like they’ve only got her to worry about, and they keep asking where she’s off to and who she’s seeing and when she’ll be back home.

They shouldn’t fuss so. She is nine, after all.

The brunette speaks for them both. Her long hair is tied back with a pink ribbon. She sounds quite bossy, foreign too. She’s got attitude. She’s looking down her nose at the blonde, who’s a bit tubby. The brunette makes the decisions, he realises that, feels it.

‘I don’t believe it. You’re too young. What’s so important you’ve got to be out at this time?’

He likes the slightly plump blonde best. Her eyes have a sneaky look. Eyes with a look he’s seen before. By now she dares, she steals a glance at her dark-haired friend, then at him.

‘Actually, we’ve been training.’

Maria keeps talking, always. She fancies herself. She’s the one who says what they think.

But it’s her turn now. She wants to say something too.

This guy isn’t dangerous. Not angry or rough or anything. His cap’s nice, just like Marwin’s.

Marwin is her big brother. She’s called Ida. She knows why, it’s because Marwin was so keen on that book about Emil and Ida. So her mum and dad figured her name should be Ida. It’s ugly. She thinks it’s horrid. Sandra is nicer. Or Isidora. Imagine being called Ida. It’s like, you’re the one they play silly tricks on, perching you on top of a flagpole. Stuff like that.

She’s hungry, it’s ages since she had something to eat. The food was yucky today. Stew, with meat in it. Training always makes her hungry. Usually they’re in a hurry to get home to supper, not like now, Maria has to talk and talk and the guy with the cap keeps asking her things.

No animal. No car. No sweeties. No need for any of that. They’re talking to him and that means everything is fixed. When they talk, it’s fixed. He looks at the slightly plump blonde. She, who dared to speak, and he hadn’t thought she would. She, who’s naked.

He smiles. They like it. If you smile, they trust you. When you smile, they smile back.

Only the blonde. Only her.

‘You’re kidding. Have you been training? Training for what? I’m just curious.’

The slightly plump blonde smiles. He knew it. She’s looking at him. He grabs hold of his cap, twists it round half a turn until the visor is in front. Then he bows to her, pulls the cap off, raises it, holds it in the air above her head.

‘Hey, do you like it?’

She raises her eyebrows, glancing upwards without moving her head. As if fearing that she might hit her head against an invisible ceiling. She pulls herself in, makes herself small.

‘It’s great. Marwin’s got one like that.’

Only her.

‘Who’s Marwin?’

‘My big brother. He’s twelve.’

He lowers the cap. That invisible ceiling, he’s pushed through it. He strokes her pale hair quickly. It’s quite smooth, soft. He places the cap on her head. On that smooth softness. The cap’s colours, red and green, suit her.

‘It’s good on you. You look great.’

She doesn’t say anything. The brunette is just about to speak, so he’d better be quick.

‘It’s yours.’

‘Mine?’

‘Yes, if you want it. You look pretty with it on.’

She looks away, gets hold of the brunette’s hand. She wants to pull them both away from the park bench, away from the man who had been wearing the red and green cap.

‘Don’t you like it?’

She stops, lets go of her friend’s hand.

‘Yes, I do.’

‘You can keep it.’

‘Thank you.’

She curtseys.

That’s rare these days. Girls did things like that in the past, but not now. Everybody is equal these days, meant to be anyway, so no curtseys to anyone. Nobody bows properly either.

The brunette has been silent for much longer than she’s used to. Now she grabs hold of the slightly plump blonde’s hand, hard. She tugs at it and both of them stumble.

‘Come on, let’s go now. He’s just a crappy cap-man.’

The slightly plump blonde turns to the brunette and then to him, looks back at her friend; obviously she’s feeling stroppy.

‘Hang on. We’ll go soon.’

The brunette speaks more loudly.

‘No, now. Right away.’

Then she turns to him, pulling at her long ponytail.

‘And that cap’s ugly. Like, it’s the ugliest ever.’

She points at the cap, then jabs it with her finger.

An animal. A cat. A dead cat? They’re nine, at most ten years old. A cat should be fine.

‘You never said what you were training at.’

The brunette looks accusingly at him with her hands on her hips, she’s like an old woman in a bad mood. He faced one once, in Säter secure that first time; she was a nosy bitch hammering on about Reform. Change. He can’t change. He doesn’t want to change. He is who he is.

‘Gymnastics. We’ve been training gym. We do it lots, all the time. We’re off now.’

They walk away, the dark-haired girl in the lead, the slightly plump blonde one following, less confidently. He watches their backs, sees their backs naked, bums naked, feet naked.

He goes after them quickly, passes them and stops, holding up his hands.

‘What are you doing, crappy cap-man?’

‘Where?’

‘Where what?’

‘Where do you train?’

Two elderly women are strolling down the slope, getting close to the flowers that may or may not be roses. He glances at the women, looks at the ground and counts to ten quickly before looking up again. They’re still there, but about to turn off down the other path, the one that leads to the fountain.

‘What are you doing, crappy cap-man? Praying?’

‘Where do you train?’

‘Not telling.’

The slightly plump blonde is staring angrily at her friend. Maria is speaking for both of them again. And she doesn’t agree. There’s no need to be rotten.

‘We train in the Skarpholm Centre. You know. It’s over there, kind of.’

The blonde points in the direction of the hill they have just come walking down.

The cat. The dead cat. Bugger that. Bugger all animals.

‘Is it any good?’

‘No.’

‘It’s yuckier than you.’

Not even the brunette could keep her mouth shut for long. Both are biting on the bait now.

He’s still standing in front of them, but lowers his arms. One of his hands slips across his black moustache, pats it a little.

‘I know where they got a new leisure centre, a brand- new one. Not far from here. Look over there, near the big block of flats, there’s a white house next to it. See it? I know the guy who owns it. I hang out there a lot myself. Would you prefer training there? All of your mates, the whole gym club, I mean.’

He’s pointing eagerly, they look in the direction of his arm, the slightly plump blonde curiously, the dark whore with that attitude of hers.

‘There’s no leisure centre in that house. You’re a crappy cap-man. It’s not true.’

‘Have you been there?’

‘No.’

‘So what do you know? It’s there, brand new, that’s for sure. It’s not nasty at all.’

‘That’s what you say. You’re fibbing.’

‘Fibbing?’

‘You’re telling fibs.’

Maria just talks. Talks and talks, all the time. She shouldn’t do that. Not for her. And she shouldn’t be so beastly. She’s just cross because she didn’t get his cap. He gave Ida his red and green cap and she trusts him. He knows the man who owns that new gym. She doesn’t like the Skarpholm Centre, not one bit, it’s smelly and old, the mats smell like vomit.

‘I believe you. Marwin said there’s a new centre once. It’s got to be better to train there.’

Ida believes there’s a new centre over there. She believes such a lot. Anyway, it’s just because he gave her that horrid cap.

Maria knows what a new leisure centre should look like. She saw one once in Warsaw when she went there with her mum and dad.

‘I know there isn’t a new gym there, silly cap-man. It’s a lie. I know that. And if there’s no new centre there I’ll tell on you to my mum and dad.’

It’s a nice day in June, sunny and warm. A Thursday. Two little whores are walking ahead of him on the path through the park. The brunette is everyone’s whore. The slightly plump blonde is his own whore, nobody else’s. Whores whores whores. Long hair, thin jackets, tight trousers. He shouldn’t have wanked.

The slightly plump blonde whore turns to look at him.

‘We’ve got to go home soon. It’s time to eat. Mum and Marwin and me. I’m really hungry, I get that hungry after training, every time.’

He smiles. It’s what they like. He reaches for the cap on her head, pulls gently at the visor.

‘Listen, it will be super-quick. I promised, didn’t I? We’re practically there. Then you can check it out, see if you like it. If you want to do your training there. It smells new, know what I mean? You know what new places smell like, don’t you?’

They step inside. He’s slept there the last three nights. Breaking in was no trouble, he did the lock easily. A shared basement with storage pens, one for each flat. Lousy pickings, though. Cardboard boxes full of household kit and books, that sort of crap. Prams, IKEA shelving, a standard lamp or two. Fuck all. Except for the kid’s bike, black with five gears, in Flat 33’s pen at the far end. He’d flogged it but only got Z50 smackers. A whole block, and no goods except a fucking kid’s bike.

He grabs hold of their arms as soon as they are in the basement corridor, one girl in each hand. He grips hard and they scream the way they all scream, so he tightens his hold. He’s in charge, makes the decisions. Whores scream. After sleeping in this dump for three nights running he knows that not a fucking soul comes down there after dark. Twice he’s heard someone in the morning, moving along the basement corridor and shuffling about in one of the storage pens. Afterwards, silence. The little slags might as well scream. Whores should scream.

She’s thinking of Marwin. She’s thinking of Marwin. She’s thinking of Marwin. Marwin’s room. Is he there now? She hopes he’s there, in his room. At home. With Mum. She thinks of him lying on top of his bed, reading. That’s what he likes doing in the evenings. Mostly Donald Duck, the small pocket books, they’re still his favourites. He read a bit of Lord of the Rings once, but it’s the pocket Donald Ducks he likes best. She feels sure that’s what Marwin is doing.

Horrid crappy cap-man. Horrid crappy cap-man. Horrid crappy cap-man.

She mustn’t speak to men like him. Mum and Dad keep nagging about it, go on and on at her and she swears she never speaks to them. And she doesn’t. Or anyway, only to tell them off. Ida doesn’t dare do that. But she dares. Mum and Dad will be furious if they hear that she’s talked to one of them. She doesn’t want them to hear that, they mustn’t be angry with her.

Number 33 is best. That’s where he nicked the bike. And where he slept.

They’ve stopped screaming. The fat little blonde whore is crying, red-eyed, snot running from her nose. The dark slag looks obstinate, staring at him, challenging him, hating. He ties their hands to one of the pipes running along the cement-grey wall. It’s hot, must be a hot water pipe. It will burn their arms. They both kick, trying to hit him. Every time, he kicks them back. They get the message soon enough and don’t try kicking any more.

They’re sitting still now. Whores should sit still. Whores wait for what’s coming to them. He calls the shots. He takes his clothes off. T-shirt, jeans, underpants, shoes, socks. In that order. He undresses in front of them. If they don’t look at him, he kicks them until they do. Whores should look. He stands naked in front of them. He’s handsome. He knows that he’s handsome. Trained body. Muscular legs. Firm buttocks. No belly. Handsome.

‘What do you think?’

The dark slag is crying now.

‘Horrid horrid cap-man.’

She’s crying, she took her time, but she’s just like all the whores.

‘What do you think? Handsome or what?’

‘Horrid horrid cap-man. I want to go home.’

His cock is hard. He calls the shots. He comes up close, pushes his penis at their faces.

‘Looks good, eh?’

He shouldn’t have wanked. He did it twice this morning. He can only manage two more times, probably. He does it in front of them, his breathing quickens. He kicks the fat blonde when she looks away for a moment, empties himself in their faces, on their hair, it gets messy when they shake their heads.

They’re crying. Whores always cry, all the fucking time.

He undresses them. Their tops have to be cut first, now that their hands are tied to the hot pipe. They’re younger than he’d thought, no sign of tits.

He pulls everything off except their shoes. Not the shoes. Not yet. The fat blonde slag has got pink shoes, shiny, like patent leather. The brunette is wearing white trainers, like for playing tennis in.

He bends over the fat blonde whore. He kisses her pink shoes on top, near the toes. He licks both of them, starting at the toe, all along the shoe, the heel too. He takes them off. Her little whore’s feet are gorgeous. He lifts one of her feet, she almost tips over backwards. He licks her ankle, her toes, sucks a little on each one. He glances up at her face, she’s crying quietly.

He feels an urgent desire.

She always wakes when the newspaper arrives. Every single morning. It falls on the wooden floor with a sodding awful thump. Then there’re two more thumps, next door, and then the next one along. She has tried to catch him, tell him to stop, but has been too late every time. She caught sight of his back quite a few times. He’s young, with his hair in a ponytail. If she gets hold of him she’ll explain how people feel at five o’clock on Sunday mornings.

She can’t go back to sleep now. She twists and turns, she’s sweating. Must go back to sleep, should sleep, but no, it can’t be done. She never used to have this problem, it’s different now, her thoughts attack her at once and by six o’clock she’s really tense, to hell with the paperboy and his ponytail.

The Sunday version of Dagens Nyheter feels as weighty as the Bible. She starts reading part of it in bed, looking at the words and then more words; there are too many. Nothing makes sense to her. Lots of in-depth reports about interesting people, she ought to read them but feels too tired to get her mind round it all. She makes a careful pile, she’ll tackle it later. She never does.

She is restless. All these hours. Read DN, then coffee, do teeth, breakfast, make bed, wash up, teeth again. It’s not even half past seven yet, a Sunday morning in June with beams of sun piercing the Venetian blinds. She turns her head away, can’t face the light yet, too much summer out there, too many people holding other people’s hands, too many people sleeping close to other people, too many who’re laughing, making love. She can’t face any of them, not just now.

She walks down the steps to the basement, to the store. It’s dark down there, lonely and untidy. She knows she’s got at least two hours of work ahead, sorting and packing. It’ll take her to half past nine. Not so bad.

The first thing she notices is that the padlock has been forced. And the padlocks on either side as well, on both 32 and 34. She’d better find out who owns them; after seven years in the house she wouldn’t even recognise her neighbours. But now they’ve got forced padlocks in common. Now they can talk to each other.

The next thing she notices is the bike. Or rather, that the bike isn’t there. Jonathan’s expensive five-geared black mountain bike. And to think that she was going to sell it; it should have been worth at least 500 kronor. Now she’s got to phone him, he’s with his father, but better tell him now so he’ll have time to calm down before he comes to stay with her.

Afterwards she cannot explain why she didn’t see them. Why she was worrying about the owners of pens 32 and 34, about Jonathan’s bike. As if she did not want to see, was unable to see. When the police asked what she had noticed first on entering the pen, wanting her crucial first impressions, she started laughing hysterically. She laughed for a while, started to cough and then explained, with tears flowing down her cheeks. Her first reaction had been that Jonathan would be upset, because his black mountain bike was gone and he wouldn’t be able to spend the money he’d get from-selling it on the PlayStation game he wanted. It cost at least 500 kronor.

Of course, she had never seen death before, never come across anyone so still, looking at her without breathing.

That’s what they did. They looked at her. They were lying on the cement floor with their heads propped up on upturned flowerpots, like rigid pillows. Two little girls, younger than Jonathan, no more than ten years old. One blonde, one dark. There was blood all over them, on their faces, chests, thighs, between their legs. Dried blood everywhere, except their feet; their feet were so clean, almost as if they had been washed.

She had never seen them before. Well, maybe. They lived nearby, after all. Sure, she might have seen them. In the shop, maybe, or in the park. Always so many children in the park.

They’d been on the floor in her storage pen for three days and two nights, that’s what the police doctor said. Semen had been sprayed all over them, in vagina and anus, on chest and hair. Vagina and anus had received what the doctor called sharp trauma. A pointed object, probably made of metal, had been repeatedly forced inside, causing severe internal haemorrhaging.

They might have been in the same school as Jonathan. Crowds of girls there, all looking alike, girls do, alike as a thousand sisters.

They were naked. Their clothes had been arranged in front of them, just inside the door of the pen. One piece of clothing after another, lined up like exhibits. Jackets folded, trousers rolled up, T-shirts, panties, tights, shoes, a hair- ribbon, everything was very neatly and precisely placed with about two centimetres between each item. Just about exactly two centimetres apart.

The girls had been looking at her. But they had not been breathing.

ABOUT NOW

I

(24 HOURS)

Putting on a mask always made him feel very silly. A grown man hiding behind a kid’s mask ought to feel silly. But he had watched other men doing it, playing at being Winnie the Pooh or Uncle Scrooge McDuck with some kind of dignity, as if the mask didn’t bother them. I’ll never get the hang of this, he thought, never get used to it. Won’t ever turn into the kind of father I wanted for myself once, the kind I was determined to be one day.

He kept touching the thin, garishly coloured plastic membrane that covered his face. It was held on by a rubber band that fitted tightly round the back of his head and had become tangled in his hair. It was hard to breathe, each breath smelled of saliva and sweat.

‘You must run, Daddy! You’re not running! You’re standing still! Big Bad Wolf’s always running!’

She had stopped in front of him, looking at him with her head tilted back, bits of grass and earth scattered in her long blonde curls. She was trying to look cross, but angry children don’t smile and she did; she was smiling with the beaming face of a child who has been chased by the Big Bad Wolf, round and round a house in the small town. Chased until her dad couldn’t stand it any more, wanted very much to be somebody else, someone who didn’t wear a mask with a wolf’s plastic tongue and teeth.

‘Marie, I can’t hack it any more. Big Bad Wolf has to sit down and rest for a bit. The Big Bad Wolf wants to become small and kind.’

She shook her head.

‘One more time, Daddy! Just one more.’

‘That’s what you said last time.’

‘This is the last time.’

You’ve said that before too.’

‘It’s the last time. For sure.’

‘Sure, sure?’

‘Sure.’

I love her, he thought. She’s my daughter. It didn’t happen immediately, I didn’t understand at first, but now I do. I love her.

Suddenly he caught sight of the moving shadow. Just behind him. It was slow, crept along. He’d thought the other one was somewhere ahead of him, over by the trees, instead of right behind him, but there he was, moving stealthily at first, then speeding up, just at the moment when the girl with the mucky hair attacked from in front. They pushed him at the same time from opposite directions. He staggered, fell and hit the ground. Now they could both jump on top of him. They stayed as they were, then the girl with mucky hair raised her hand, palm outwards, and the dark- haired boy, the same age as her, raised his hand. Their palms slapped together. High five!

‘David, look! He’s given in!’

‘We won!’

‘The Pigs are the best!’

‘The Pigs are always the best!’

Attacked by two five-year-olds from opposite directions, the Big Bad Wolf hadn’t got a hope. As always. He knew what he must do, and rolled over, the two creatures on top of him following the roll. Lying on his back, he raised his hands to the plastic mask and pulled it off his face, blinking in the strong sunlight. He laughed out loud.

‘Isn’t it funny? I lose every time. Never win. Have I ever won, just once? Can anyone explain what’s going on?’

Waste of breath. The two creatures didn’t listen. They had won the prize, the plastic mask. They would try it on first, then celebrate by wearing it for a run-around. Afterwards they would go inside, upstairs to Marie’s room on the first floor, to add the mask to their other trophies. They would stand in front of the pile for a moment, a Ducksburg monument to the glory of two five-year-old friends.

As the children wandered away, his eyes followed them. He looked at the boy from next door, then at his daughter. So much life inside them, so many years held in their hands, with months slipping between their fingers. I envy them, he thought. I envy their endless time, their sense that an hour is long, that winter will last for ever.

They disappeared through the door and he turned his face towards the sky. Lying on his back, he searched for different shades of blue, something he had done when he was little and now did again. Any kind of sky held different blues. He’d had a good time back then, when he was just a small boy. His father was a career army officer, a captain, and that meant something. You were in a regiment. Your future promotion was embroidered on the shoulders of your uniform, or so you hoped, at least. His mother was a housewife, at home when he and his brother left for school, and still there when they returned. He’d never understood what she found to do, alone in four rooms on the third floor of a block of flats. How did she endure the sameness of her days?

On his twelfth birthday everything changed. Or, to be exact, on the day after. It seemed that Frans had waited until his birthday celebrations were over, as if he had not wanted to ruin them. As if he knew that for his little brother a birthday was something more than when you were born; it was all your longing concentrated into one day.

Fredrik Steffansson got up and brushed the grass from his shirt and shorts. He often thought about Frans, remembered missing him, more now than he’d used to. From the day after his birthday his brother simply wasn’t there. His empty bed stayed made for ever. Their talking together silenced. It was so sudden. In the morning Frans had hugged him for a long time, longer than any time Fredrik could recall. Frans had hugged him, said goodbye and walked off to Strängnäs station in time for the fast train to Stockholm. Next, no more than an hour later, in the metro station, he had bought another single ticket and caught a green line train going south, towards Farsta. At Medborgar Square, he got off, then jumped from the platform on to the track and started walking slowly between the rails into the tunnel towards Skanstull. Six minutes later a train driver caught sight of a human shape in the light of the bright headlamps and threw himself at the brakes, screaming in anguish and terror as the front carriage hit a fifteen-year-old body.

Ever since, they had left Frans’s bed untouched, the bedspread pulled tight, the folded red blanket at the foot- end. He never understood why. Still didn’t. Maybe to look welcoming if Frans returned. For years he had kept hoping that one day his brother would simply be there, that it had all been a mistake. After all, such mistakes are not unheard of. They can happen.

It was as if the whole family had died that day, on the track in a tunnel between Medborgar Square and Skanstull. His mother no longer spent her days waiting around in the flat. She never told anyone where she went but, regardless of season, she was always back at dusk. His father collapsed in every way. The straight-backed captain looked crumpled and bent, and while he’d been taciturn before, he now became practically mute. He stopped chastising his son. At least, after Frans had died, Fredrik couldn’t remember ever being beaten again.

They were back, standing in the doorway. Marie and David. One as tall as the other, five-year-olds’ height; he’d forgotten how many centimetres, it had said on the note from the nursery that stated Marie’s height and weight, but both kids were presumably as tall as they ought to be; he didn’t much care for notes with statistics. Marie’s long blonde curls were still full of grass and stuff, and David’s short dark hair was sticking to his forehead and temples, which meant that he’d put the mask on while they were inside. Fredrik observed them knowingly and laughed.

‘Look at you, so neat and tidy. Not. Just like me. We all need a bath. Do pigs take baths?’

He didn’t wait for a reply. Putting one hand on each of their thin bony shoulders, he pushed them gently back into the house, through the hall, past Marie’s room, past his bedroom, and into the big bathroom. He filled the old bathtub with water, a high-sided old tub on feet and with two seats inside. He’d found it at an auction of stuff from some grand house. Every night he would sit in the bath, allowing the sauna-like conditions to relax him and thinking, doing nothing for half an hour or so, except planning what he’d write the following day. The next chapter, the next word.

Now he worried about getting the water right for them. Not too hot, not too cold. He squeezed foam from a green Mr Men bottle. It looked soft and inviting. To his surprise they stepped into the bath without any fuss and settled side by side on one seat. He undressed quickly and sat on the seat opposite them.

Five-year-olds are so small. You don’t realise quite how small until they’re naked. Soft skin, slender bodies, forever hopeful faces. He looked at Marie, her forehead covered in white bubbles that trickled down her nose. He looked at

David, who was holding the empty Mr Men bottle upside down, making more bubbles. He felt he lacked a picture of himself at the age of five, and tried placing his own head on Marie’s shoulders. People said that they were strikingly alike, they enjoyed pointing it out. This baffled him and embarrassed Marie. His five-year-old face on her body. He ought to recall something, have a recognition of the way he’d felt then, but all he remembered was the beatings. He and Dad in the drawing room, that fucking awful big hand hitting his bottom, this he did remember, and he remembered too Frans pressing his face against the pane of glass in the drawing room door.

‘The foam’s finished.’

David held out the bottle to show him, shook it with the spout touching the water.

‘I noticed. Now, could that be because you’ve poured it all out?’

‘Wasn’t I meant to?’

Fredrik sighed.

‘Oh, sure. Of course.’

‘You must buy another one.’

He had used to do it too, watch through the pane when Frans was beaten. Dad never noticed either of them, how they’d be observing what happened through the glazed panel in the door. Frans was older. He got hit more times, the beating took longer, at least that was how it felt from a couple of metres away. Fredrik had not remembered any of this until he was an adult. The beatings hadn’t happened for over fifteen years and then, suddenly, it all came back, the big hand and the pane of glass. He was almost thirty by that stage and ever since then he’d had to haul his thoughts away from the memory, away from the drawing room. Not that he felt angry, oddly enough not even vengeful; instead he grieved, or at least, the nearest thing to what he felt was grief.

‘Dad. We’ve got more.’

He stared vacantly at Marie. She chased that hollow feeling away.

‘Hey! Dad!’

‘More what?’

‘We’ve got more Mr Men bath foam.’

‘Do we?’

‘On the bottom shelf. Two more. We bought three, you see.’

Frans had felt a greater grief. He was older, more time had passed, more beatings. Frans used to cry behind the pane of glass. He cried only when he was watching. Only then. He lived with his grief, hid it, carried it with him, until it became all he was, savagely threatening his self. Its last, conclusive blow struck him that morning, backed by a thirty- ton carriage.

‘Here it is.’

Marie had clambered out of the tub and padded over to the bathroom cabinet.

‘Look. Two more. I knew that. ’Cause we bought three.’

She pointed proudly.

The floor was awash, foam and water had been pouring off her body but she didn’t notice, of course, just climbed back into the tub clutching the Mr Men figure. She got the top off with less trouble than he’d expected. David grabbed the bottle and instantly, unhesitatingly turned it upside down, shouting something that sounded like ‘Yippee!’ And they did their high-five handclap again.

He hated nonces. Everyone did. Still, he was a professional. A job was a job. He kept telling himself that. A job a job a job.

Åke Andersson had transported criminals to and from assorted care institutions for thirty-two years. He was fifty- nine now, but his greying hair was still thick, well looked after. He carried a kilogram or two more than he should, but he was tall, taller than all his colleagues, and any villain he’d driven. He admitted to 199 centimetres. Actually 202 was nearer the mark, but if you were over two metres tall, folk took you for a freak, one of nature’s misfits, and he was fed up with that.

He hated nonces. Perverts who used force to get pussy. Most of all he hated the beasts who forced kids. His feelings were strong and therefore forbidden, but his hatred grew in intensity with each nonce job, the only times in his daily round when he responded emotionally. The aggression he felt frightened him. He had to control his urge to stop, shut down the engine, take a long stride between the front seats and fix the bastard by pushing him against the rear window.

He showed nothing.

No question, he’d had worse scum in the van, or, at least, scum with heavier sentences. He’d seen it all, put handcuffs on every fucking hard man in the headlines, walked them to the bus and driven them, staring vacantly into the mirror. Many of them were complete cretins. Loonies. Only a few had got their heads round the idea that there’s a cost. If you buy, you’ve got to pay, it’s that simple. Never mind the suckers outside, with their sermons about care and concern and rehabilitation. You buy and you pay. That’s all.

He could spot the perverts, pick them out every single time. There was something about them, which meant he didn’t need to know the charge. No paperwork required. He saw and hated. Now and then he had tried to explain it over a beer in the pub, tried to convince people that it was possible to spot them and that he knew how. Trouble was, when his mates asked for details he couldn’t say and they reckoned he was prejudiced, possibly homophobic or even anti-everybody. Now he kept his mouth shut: it was too much hassle and not worth the effort. Still, he knew who was who, and the scumbags sensed it, looking away shiftily when his eyes sought theirs.

This nonce in the back had done the rounds. Åke had driven him at least six times. Back in ’91, a couple of round- trips between trial court and the cells, then again in ’97, after he’d done a runner and been caught once more. Another trip in ’99, from Säter secure to wherever it was. Now he was off to the Southern General Hospital, in the middle of the night. He looked at the face in the mirror and the beast looked back, it was like some pointless competition about who could keep staring the longest. As ever, he seemed normal enough. At least, he would’ve, to most people. A bit shortish, 175 centimetres, say, medium build, close-cropped hair. Calm. Normal. Except, he was a repeat child rapist.

Red lights at the start of the uphill run along Ring Street. Not much traffic at this time of night. Blue lamps materialised behind him. An ambulance, its sirens blaring. He stayed where he was to let it overtake.

‘That’s it, Lund. You’ve got thirty seconds now, then out. We phoned ahead, a doctor is seeing you straight away.’

Åke didn’t talk with nonces. Never did. His colleague knew that. Ulrik Berntfors felt very much the same way, it was just that he didn’t hate.

‘This way we don’t have to wait for our breakfast. And you don’t have to sit in the waiting room with all that kit on.’

Ulrik gestured at Lund, at the chain across his stomach. It was part of a transfer waist-restraint, complete with leg- irons. He had never had to use one before. Body-belts, yes. Still, it was an order. Oscarsson had phoned up about it, made a special point. Told to undress, Lund had smiled and waggled his hips. He was fitted out with a metal belt round his waist, joined to the leg-irons with four chains running down his legs and to the handcuffs with two chains along his torso and arms. Ulrik had seen these things on TV and once for real, during a study visit to India. Never in Sweden. Here, the main idea was to control offenders by outnumbering them. More guards than villains. Sometimes handcuffs, of course, but not chains inside shirt and trousers.

‘How caring. Thanks a lot. You’re great guys.’

Lund was speaking quietly. He was barely audible. Ulrik had no idea if what he said was meant to be ironic. Then Lund shifted position, chains clanking against each other, until he was leaning forward with his head resting on the frame of the glazed hatch separating the front seats from the back of the van.

‘Listen, you two. This is no good. I’ve got chains up my arse. Get me out of this fucking tin body-belt and I give you my word I won’t run.’

Åke stared at him in the mirror. He speeded up suddenly, shot along the slope up to the Casualty entrance and then stood on the brakes.

Lund’s chin crashed against the sharp edge of the hatch.

‘Fucking screws! What the fuck’s that for? You cunts!’

Usually Lund spoke calmly and sounded quite educated. Until he felt got at. Then he swore. Åke knew that. It wasn’t just that they all looked alike. They were alike.

Ulrik was laughing, but only inside. That bugger Andersson, he wasn’t quite right in the head. He kept doing stuff like this, but refused to say a word.

‘Too bad,’ he said. ‘Nothing doing, it’s Oscarsson’s orders. You see, Lund, you’re classed as dangerous. A danger to society. So you’d better lump it.’

Ulrik found it difficult to utter all this. The words seemed to have a will of their own, pushing their way out of his mouth despite his straining facial muscles, tensed to hold back the rumbling laughter inside. If it slipped out and was heard, it would provoke their passenger even more. He spoke, but afterwards, following Andersson’s example, stared silently straight ahead.

‘If we take the tinsel off you, we’d be ignoring Oscarsson’s express order. And that’s against the regulations. You know that.’

The ambulance that had overtaken them was parked next to the ramp outside Casualty. Two male paramedics were running up the stairs to the entrance, two steps at a time, carrying a stretcher. Ulrik caught a glimpse of a woman; the blood in her long hair made it stick to the leg of one of the paramedics. Orange and red don’t go together, he thought, wondering why they wore orange, they must get blood on their uniforms pretty often. Being upset always made his mind wander.

‘Oscarsson’s an arsehole! He’s fucking lost it. Why won’t that motherfucker believe me? I said I won’t run! I told him at Aspsås!’

Lund was shouting through the hatch, then backed away only to throw himself against the windowless wall. The chains of his restraint thumped against the metal side of the van, making Åke momentarily think he’d hit something, turn to look for another vehicle that wasn’t there.

‘I fucking told him, you bastards! So you didn’t know? OK, here’s another deal. If you don’t get this lot of chain- mail off me, I’ll be away. Get that, cunts? I’ll walk. Understood?’

Åke tried to meet his eyes. He adjusted the mirror to find Lund. He sensed the hatred welling up; he had to hit him, that scum had gone too far, had just said ‘cunt’ once too often.

Thirty-two years. A job a job a job. But he couldn’t hack it any more. Not today. And sooner or later it would all go to hell, whatever.

He ripped off the seatbelt, opened the door. Ulrik realised what was up, but didn’t have time to act. Åke was going to beat the shit out of the nonce. Lund would get it harder than any of them ever had. Not that Ulrik minded. He stayed where he was, smiling to himself.

The town was never more silent than a few minutes past four in the morning. After the last customers had left Hörnans Bar to make their way noisily from the harbour along the Promenade towards the old bridge to Toster Island, there was this quiet space, until the newspaper boys delivering the Strängrtäs Gazette fanned out to sprint along Stor Street, opening porch doors and letterboxes.

Fredrik Steffansson knew it all, he hadn’t slept through the night for ages. He kept the window open, so he could lie in bed and listen to the little town falling asleep and waking again, to the movements of people he mostly knew, or at least recognised. That’s how it is when your world is small-scale. Everything crowds in on you. He had lived here almost all his life. Sure, he had read a lot of books by the right people and gone off to live in Stockholm’s South End, studying comparative religion at the university. Then he had worked in a kibbutz in northern Israel, a few miles from the Lebanese border. But once all that was over and done with, he returned to Strängnäs and the people he knew, or at least recognised. He’d never truly got away, never left growing up here behind him. His memories and his lasting sadness at the loss of Frans tied him to this town. It was here he had met Agnes. He had fallen madly in love with her, she was so sophisticated, exclusively dressed in black, always searching for something. They started living together, but had been about to part when Marie arrived and made them rediscover each other, so that, for almost a year, the three of them were a family. Then Fredrik and Agnes separated for ever, not as enemies, but they spoke only when Marie was to be delivered or collected. She had to travel from one city to another, because Agnes had moved to Stockholm, living among her beautiful friends, where she really belonged.

Someone was walking down there in the street. He checked the time. Quarter to five. Bloody nights. If only he could think of something that made sense, his next piece of writing, just the next two pages, but no, it seemed impossible. He couldn’t think at all, the empty time passed as he listened to what seeped in through the window, taking note of when doors closed and cars started. Meaningless accountancy. He had hardly any energy left for writing. When he had delivered Marie to nursery school and settled down at his computer with the day stretching ahead of him, the hours without sleep attacked, tiredness engulfed him. Three chapters in two months was simply disastrous, his powerful publisher wouldn’t put up with it and was already sending out feelers to find out what was up.

A truck. That sounded like that truck. But it usually didn’t run before half past five.

Such a thin partition to Marie’s room. He could hear her. She was snoring. How come little children snore like fat old men? Fragile five-year-olds with piping voices, as cute as anything? He used to think it was just Marie, but whenever David slept over they made twice as much noise, filling the silences between each other’s breaths.

It wasn’t a truck. A bus, that was it.

He turned away from the window. Micaela slept in the nude, blanket and sheet bundled up at her feet as always.

She was just twenty-four, so young. She made him feel loved, often randy, and, at times, so old. It would hit him suddenly, often when they were talking about music or books or films. One of them would make a remark about a composition, or someone’s writing, or a play, and it would become obvious that she was young and he was middle-aged. Sixteen years is a long time in the life of guitar solos and film dialogue; they age and fade away and get replaced.

She was lying on her stomach, her face turned towards him. He caressed her cheek, planted a light kiss on a buttock. He liked her very much. Was he in love? He couldn’t bear the effort of working it out. He liked that she was there, next to him, that she agreed to share his hours, for he detested being lonely, it was pointless, like suffocating; surely solitude was a kind of death. He moved his hand from her cheek to stroke her back. She stirred. Why did she lie there, next to an older man with a child, a man who wasn’t that good-looking, not ugly but certainly not handsome, and not well off, and, arguably, not even fun to be with? Why had she chosen to spend her nights with him, she who was so beautiful, so young and had so many more hours left to live? He kissed her again, this time on her hip.

‘Are you still awake?’

‘I’m sorry. Did I wake you?’

‘I don’t know. What about you, haven’t you been asleep?’

‘You know what I’m like.’

She pulled him close, her naked body against his, sleepily warm, awake but not quite.

‘You must sleep, my old darling.’

‘Old?’

‘You can’t cope if you don’t sleep. You know that. Come on. Sleep.’

She looked at him, kissed him, held him.

‘I was thinking about Frans.’

‘Fredrik, not now.’

‘I do think about him. I want to think about him, I’m listening to Marie next door and I’m thinking about how Frans too was a child when he was beaten, when he watched me being beaten. When he caught the train to Stockholm.’

‘Close your eyes.’

‘Why should anyone beat a child?’

‘If you keep your eyes closed for long enough you go to sleep. That’s how it works.’

‘Why should anyone beat a child, who will grow up and learn to understand and judge the person who’s been beating it? At least, judge the rights and wrongs of that beaten child.’

She pushed at him to turn him on his side with his back towards her, then moved in close behind him, twisting into him until they were like two boughs of a tree.

‘Why keep hitting a child, who will construe the beatings as Daddy’s duty and look to its own failings for the reason. I’m not good enough, not tough enough. The child will tell itself that it’s his or her own fault, partly at least. Christ almighty, I was into that kind of crap myself. I forced myself to believe it, not to feel violated and abandoned.’

Micaela slept. Her breathing was slow and regular against the back of his neck, so close that the skin became damp. Through the window came the sounds of another bus. It stopped outside, reversed, stopped again, reversed. Perhaps the same one as yesterday, a large coach.

Lennart Oscarsson carried a secret. He wasn’t alone in this, but felt as if he were. The pain of it rode him, curled up on his right shoulder, slept inside his chest, occupied all the space inside his stomach. Every evening he decided to let it out the following morning. Once he had set it free, he could sit back quietly, contemplating days without a secret for company stretching out ahead.

He didn’t have the strength, couldn’t do it. He was screaming, but nobody listened. Maybe to scream properly you actually had to open your mouth?

He did the same things every morning. Sat in the kitchen at their round pine table, spooning yoghurt into his face. Karin was always there at his side. She was his life, this beautiful woman, whom he had loved beyond reason ever since he’d met her for the first time, sixteen years ago. She drank her usual coffee with hot milk, ate rye bread and butter, read the arts pages in the morning paper.

Now. Now!

He should tell her now. Then it would have been said. She had every right to know. Others didn’t, but she did. It was so simple. A couple of minutes, a few sentences, that was all. They could finish their breakfasts, leave for their daily work. He would return home that night freed from having to hide it. He put the spoon down, drank the last of the yoghurt straight from the container.

Lennart took pride in his work at Aspsås prison. He held a senior post, chief officer in charge of a unit, and had ambitions to advance further. He took every opportunity for study leave, joined every course, reckoned you had to show willing, and he did, in the knowledge that somewhere, someone was taking notes.

Seven years ago he had taken over the running of one of Aspsås’s two units for sex offenders. His working life had become focused on people locked up for violating those whom they had been charged to protect. These men had broken the strongest taboo left in society, they were outcasts; he was responsible for them and for the staff who were employed to care as well as to punish. Punishing and trying to understand, this was what they were meant to do, care and punish and remain aware of the difference. His views were his own, he felt what he felt, but he did show willing, and someone, somewhere, kept notes on his progress.

At the same time his bloody awful secret had started growing. How he wished he could tell. The outcome couldn’t be any worse than now, when the betrayal lived inside his marriage and made every word he and Karin exchanged suspect, filthy.

He got up, picked up the dirty dishes and stacked the dishwasher. Wiped the table, rinsed the cloth.

He wore a blue uniform. Officers’ uniforms looked the same throughout the Swedish prison service, rather like a cab driver’s outfit. He dressed for work in the kitchen: trousers, tie, shirt. Meanwhile he hoped that Karin and he would exchange a few words, about anything as long as it stopped him feeling so bloody hypocritical.

‘Look at the weather, Lennart. It’s windy outside. They say it’ll stay like this all day. You need your gloves.’

Karin came close to him and stroked his cheek. He pressed his face against her hand, rubbed against it, needing the contact. She was so beautiful. He wished she knew.

‘It’s not cold yet. And I’ve only got a few hundred metres to go.’

‘You know that’s not the point. You’ll regret it afterwards, when your joints start hurting.’

She held out his leather gloves. He put them on. Kissed her, first her lips, then her shoulder. Put on his jacket and stepped outside, looked across to Aspsås. It was only two minutes’ stroll away. Its grey concrete wall dominated the village.

When Åke Andersson climbed out of the driver’s seat, he was propelled by an emotion different from anything he had felt before. His rage, his damned hatred, had overwhelmed him.

He had taken a lot of crap from prisoners for thirty years, hated them but stayed in control, silently driven them from police cells to courts, from hospitals to prisons. He had ferried the lowlife but left the talking to his mates, just kept his eyes on the road and minded his own business. But that fucking beast was too bloody fucking much.

Åke had nearly lost it last time he had had to transfer that animal, knowing that he was holed up in the back of the van, knowing about the tortures he’d carried out, what the girls had looked like when he’d finished with them. Afterwards, his sneering grin and utter callousness haunted Åke’s dreams, the crimes were replayed over and over again, throughout the nights; one bad morning he didn’t get to the loo in time and threw up in the hall, as if his enforced control had congealed and swelled his stomach until there was no more room.

It was that third ‘cunt’ coming through the hatch that tore it. Åke lost his grip, had no idea what he should do next, no sense of duty left. He couldn’t answer for the consequences now; his mind was filling with images of the little girls, their cut-up genitals, they’d been tortured with a pointed metal object. His big body hurled itself towards the back door of the van.

Ulrik Berntfors had driven Lund once before, that was all, on the second day of the girls-in-the-basement trial. He’d been new to the job and the trial was the biggest he’d been involved in, lots of journalists and photographers crowding the reserved seats. Two nine-year-old girls; it pulled at the heartstrings and sold newspapers. He was ashamed of his reaction at the time, he hadn’t really thought about the girls, not understood, had been too inexperienced. He had simply felt special, almost proud, as he walked along at Lund’s side. But afterwards his own daughter asked him why Lund had killed the two girls, why he’d wanted to destroy them. She was only a year older than the victims and had read every piece of news carefully, formulating questions for her dad, who knew the man who had done it and had walked next to him, as seen on TV, lots of times. Of course he couldn’t answer her, but understanding was dawning on him. His daughter’s fears and her questions had taught him more about his job than any course he had attended.

Åke hated, Ulrik knew that. Not that they’d ever talked about it, but it hadn’t been hard to work out. And maybe one day Ulrik would too, when scum like Lund had screamed ‘cunt’ at him once too often. He had done the person-to- person contacts, so far. Someone had to. Driving these people was a job. But when Lund shouted ‘cunts’ for the third time, he realised that this was it. He knew, from the moment Andersson got up.

Maybe if he kept observing the steps leading up to the Casualty door, he wouldn’t have to see whatever was going on. If it came to an inquiry, he didn’t want to have to lie.

The area in front of Casualty was quiet, no parked cars, no people. That’s what Åke said afterwards, adding that even if it hadn’t been so deserted, even if other people had been about and able to watch what he did, he probably wouldn’t have noticed. Running to the back of the bus, rage and hatred blinkered him.

He pulled the door open. The handle was small. His hand was made on the same scale as the rest of him and it was hard to push it in between metal and metal.

Then everything went horribly wrong.

Bernt Lund was screaming ‘cunt, cunt’ over and over, in a high falsetto voice. He hit out with the chains gripped in one hand, the long chains that ran under his clothing, linking handcuffs, leg-irons and belt. Åke didn’t have time to see, to take in what was happening, as the heavy iron links tore into his face and ripped it open. He fell to the ground and Lund leapt out of the van, swinging the chains against the fallen man’s head and face until his victim passed out. Then he used his boots, kicking belly, kidneys, crotch, kicking and kicking until the tall guard lay quite still.

Ulrik had kept staring straight ahead. Åke was taking his time beating the hell out of the nonce. Lund was still screaming ‘cunt’; he could obviously take a lot. Then Ulrik began to feel bad about it. Åke had been at it for too long, enough now for Christ’s sake, or things might go seriously wrong. When he opened the door to climb out and stop him from causing some kind of emergency, Lund moved in. Using a long chain he broke the window, hit Ulrik in the face, pulled him outside and kept hitting. All Ulrik remembered afterwards was the hellish screeching voice and the moment Lund pulled his trousers down to hit his exposed penis with the chain, screaming that he would have buggered them if they hadn’t been such big bastards. Too big for him, only little whores would take him inside, only small arses were good enough.

The distance between his front door and the steel gate leading to his place of work was 180 paces. Lennart Oscarsson counted them almost every time. Once he’d done the distance in 161 paces, his record. It was a few years ago, when he was really fit. Until the assault he used to train with the inmates in the gym. Then, early one morning, someone beat a sex offender to pulp with dumbbells and barbells. The medic had said the marks were clear and easy to identify. No one had known the first thing about the incident, of course. Not one single fucking soul had noticed that a human being was being clubbed, presumably screaming his head off, unseen and unheard, until the final darkness fell. The weight-training area was awash with blood afterwards, yet apparently no one had the faintest idea why. For a long time afterwards he didn’t go there. Not because he was frightened; nobody was quite cretinous enough to risk a new round of sentencing just to get even with a boss. It wasn’t fear, it was disgust, he couldn’t bear being in a room where one of the men in his charge had been robbed of his right to a life.

He rang the bell, waited for a sense of being watched in the small camera above his head and a voice coming through the loudspeaker. Turning round, he looked at his home, at the sitting room and bedroom windows. All dark, roller blinds halfway down. No face to be glimpsed, no body moving about.

‘Yes?’

‘Oscarsson here.’

‘Opening up.’

He stepped inside, blinked, inside an enclosed world now. The other one of his two worlds. Standing in front of the next door, he knocked on the windowpane of the guardroom and waved to Bergh, who was taking his time. Stupid bugger, what made Bergh tick was a mystery. At last he waved back and pressed a button. The door buzzed open; the long corridor behind it smelled of disinfectant and something else, something unmistakable.

A boring day ahead. Unit meeting, communication. The staff were well on their way to losing themselves in a labyrinthine schedule of meetings that they had imposed on themselves. Each meeting made endless pointless decisions about pointless routine matters that landed everyone within an ever more rigid framework. Actual problem-solving needed a different approach, needed sharp minds and driving energy. The meetings fed a sense of security, but created nothing.

And the coffee machine was fucked up as well. He kicked it. Then he fed coins into the soft-drinks machine. Coke apparently contained caffeine too.

‘Morning, Lennart.’

‘Morning, Nils.’

Nils Roth, senior wing officer. He and Oscarsson had come to Aspsås at the same time and advanced in the service side by side. Together they had experienced the anxiety of the novice change into the weary calm of the veteran. They walked into the meeting room together. The room with its long table, overhead projector, whiteboard could have belonged to any management outfit.

Everybody greeted each other; all eight senior wing officers were there, and the prison governor, Arne Bertolsson. Quite a few were drinking coffee. Lennart looked hard at the mugs and turned to the new man, what was his name, Månsson.

‘Where did you get that?’

‘The machine.’

‘It’s out of order.’

‘Not when I tried it. Only minutes ago.’

Arne Bertolsson called them to order, sounding irritable. He had been fiddling with the overhead projector. It made a noise, but that was all. The screen stayed blank.

‘This thing’s bloody useless.’

Bertolsson crouched down to examine whatever buttons he might push next. Lennart looked at him, then at the line-up of men at the table. Eight of them, his immediate colleagues, people in whose company he spent hours and hours, day after day, but had never got close to. Apart from Nils, that is. As for the rest, he hadn’t been to their homes and none of them had visited his. A beer in town, the odd football match, but never at home. What did that make them? Not friends, anyway. But they were all of about the same age, and looked alike too. A room full of middle-aged taxi drivers.

Bertolsson gave up.

‘Sod this. And the agenda too. Who wants to start?’

Nobody, it seemed. Månsson drank a mouthful of his coffee. Nils scribbled on a notepad. No one spoke. The routine of these meetings had broken down and everyone felt at a loss.

Lennart cleared his throat.

‘I’ll start.’

The others breathed sighs of relief; something was on the agenda at least.

Bertolsson nodded.

‘I’ve been on about this before, but the fact is, I know what I’m talking about. I suppose no one has forgotten the fatality in the gym? No? Exactly. But has it made any flaming difference whatsoever? The men from the normal units are shuttling in and out of the gym at the same time as my lot. There was another incident yesterday. It might’ve turned nasty if Brandt and Persson hadn’t stepped in promptly.’

Not a peep from the bench of the accused. But he bloody well wouldn’t back down. He had seen what the weights could do to a human body.

Having watched everyone in turn as he spoke, Lennart’s eyes lingered on the only woman in the room. Eva Barnard and he had clashed more than once before. He couldn’t relate to her in any way, she only knew the textbook stuff and not the traditions, the unspoken rules, which drew their power from simply having been there, always.

Bertolsson had picked up the accusation in Lennart’s eyes, but wanted to avoid trouble. Not another row, not again. He interrupted.

‘More coordination between wings, is that what you want?’

‘Yes, it is. Coordination outside the walls is a different matter. This is a jail. It’s an unreal place, the exception is the rule inside. Everyone here knows it. At least, ought to know it.’

Lennart kept his eyes fixed on Eva. Bertolsson hated conflicts, but that was too bad. No way would he be allowed to hide this problem out of sight.

‘If the wrong type from a normal unit comes across one of my lot, that’s it. End of story. Everything goes straight to hell, that’s well known. If a nonce gets killed, it’s applause all round.’

He pointed at Eva.

‘The old lag who stirred it yesterday was a case in point. He’s from your unit.’

Now they were both angry. Eva never took the coward’s way out, he had to admit that. She didn’t scare easily and now she was staring back at him. Ugly and stupid, but brave.

‘If you mean 0243 Lindgren, why not say it straight out?’

‘I mean Lindgren all right.’

‘Lindgren can be a bastard when he’s in the mood. The rest of the time he’s a model prisoner, calm and quiet. Does zilch in fact. Lies in his cell smoking handrolls, lets the hours pass, doesn’t read or watch the telly. He has served forty- two different sentences, and done a total of twenty-seven years inside. Look, he’s one of the few who still can speak the old prison lingo. He only stirs up trouble when somebody new turns up. Has to show who’s done most time, who knows the score. It’s all about hierarchy. Hierarchy and respect.’

‘Come off it. Yesterday he wasn’t trying to impress a newcomer. He would have killed my man if he hadn’t been spotted in time.’

The other officers were becoming restive. What was happening to the proper agenda? Bertolsson let this confrontation run on without comment. Maybe he found it interesting. Maybe he was too fed up to bother.

‘Let me finish,’ Eva went on. ‘Sex offenders are different, Lindgren goes wild at the sight of them. It’s something stronger than disgust. I’ve been through his file and found some reasons why he tries to kill them. For one thing, he was abused himself as a child. Many times.’

Lennart drained the last drop of sweet bubbly muck from the can. Caffeine. He knew perfectly well who Stig ‘Dickybird’ Lindgren was, no need to lecture him. Dickybird had been a dealer, mostly smalltime, in whatever came his way. By now he was so institutionalised that he was terrified every time he was released. He’d piss against the prison wall hoping that the gate staff would see him. If that didn’t do the trick he’d beat up the driver of the first likely bus into town, like the last time out. One way or another he’d be back inside within a few weeks, back to the only place where he felt at home, the only place where people cared enough to know his name.

Lennart told himself that he must stop eyeballing that silly frump. Look at Nils instead. But Nils kept his eyes down, scribbling away, no, he was doodling. How did he take this? Did he feel uneasy? Ashamed? Lennart knew that Nils didn’t care for the way he challenged Eva and had said so, asking him to leave it. Fuelling the general dislike of her just meant that they would never take any notice of the good work she often did. Admittedly.

Lennart knew that he wanted to talk to Nils about that bloody awful secret, their secret. And he waited to see if Nils would look up, just for a moment. I need your help now, Nils, look at me, what the fuck do we do next? I must tell Karin.

‘Did I hear you mention something about a prison language? You said Stig Lindgren could speak it.’

Månsson, the new recruit from Malmö, sounded interested. What was the man’s first name? Now he wanted to know more.

‘That’s right.’

‘Could you explain?’

Eva was pleased that the exchange with Lennart was over, and that she had the upper hand now. She was in charge. As she turned to Månsson, she smiled in the self-satisfied way she had, which fuelled the general dislike.

‘I suppose it’s natural that you wouldn’t know.’

This Månsson boy was new, but he had just learned something useful. Which was not to mess with her.

‘Sorry. Forget it.’

‘No, no. No problem. This prison-speak was used by the inmates all the time. It was a special communication, for cons only. By now it’s practically extinct. Only old lags like Lindgren know it. Men who’ve led their lives more inside than outside the walls.’

She felt good. Lennart had jumped on her, suggesting that she was ignorant of prison life. She’d shown everyone that she knew all right. What a loser, he’d been so stupid he reckoned he could muzzle her. Must have forgotten that she got the last word every time he tried it on.

Bertolsson had managed to start the overhead and an image showed on the screen. The agenda. He looked as relieved as he felt. This meeting had been about to run off the rails, but now he was back in control. He acknowledged the ironic applause from his colleagues.

Then a phone rang. It wasn’t his mobile. He had switched it off, as everyone should have done. The governor, already fed up, was close to blowing a fuse.

Lennart got up.

‘Sorry. It’s mine. Christ, I forgot all about it.’

A second ring. He didn’t recognise the number. A third. He shouldn’t answer. A fourth. He gave in.

‘Oscarsson here.’

Eight people were listening in. Not that it bothered him.

‘And?’ He sat down. ‘What the fuck are you saying?’

His voice had changed. It sounded screechy. Upset.

Nils, who knew him well, was instantly convinced that this was serious. He couldn’t remember Lennart ever sounding so alarmed.

‘Not him!’ A cry, in that high-pitched voice. ‘Not him! It can’t be! You heard me, it can’t be.’

His colleagues were very still. Lennart seemed close to a breakdown. He, who was always cool and collected. And now he was shaking.

‘Bloody fucking hell!’

Lennart ended the call. His face was flushed, he was breathing through his mouth. His dignity had gone. The room waited.

Lennart got up, took one step back, as if to take in the whole scene.

‘It was the man on the gate, that idiot Bergh. Told me we’ve got a runner. One of mine, on transfer to Southern General Hospital. Bernt Lund. He beat up both guards and went off in the van.’

Siw Malmqvist’s winsome voice was flooding the police station at Berg Street in Stockholm. At least, the corridor at the far end of the ground floor was awash, as it was every morning. The earlier it was, the louder the voice. It came from a huge, ancient cassette player, as big as any ghetto-blaster. The old plastic hulk had run the same tapes for thirty years, three popular compilations with Siw’s voice singing her songs in different combinations. This morning it was ‘My Mummy is Like Her Mummy’ followed by ‘No Place is as Good as Good Old Skåne’, A- and B-sides of the same 1968 Metronome single, with a black-and-white shot of Siw at a microphone stand, holding a broom and wearing a mini version of a cleaner’s overall.

Ewert Glens had been given his music machine for his twenty-fifth birthday and brought it to the office, putting it on the bookshelf. As time went by he changed office now and then, but always carried it to its new home, cradling it in his arms. He was Detective Chief Inspector now, still always the first in and never later than half past five in the morning; that meant he had two or three hours without any prats bothering him, invading his space in person or on the phone. Round about half past seven he would lower the volume; it caused a lot of bloody moaning from the useless crew pottering about outside. Still, he would always make them whinge for a while. They fucking well wouldn’t catch him turning the sound down unless someone asked first.

Grens was a large man, heavy and tired. His hair had receded to a grey, bushy ring. He moved in short, brisk bursts, due to his odd gait, a kind of limp. His stiff neck was due to a near-garrotting, a memento of leading a raid on the premises of a Lithuanian hitman. They kept Grens in hospital for quite a while afterwards.

He had been a good policeman, but didn’t know if he still was. At least, he wasn’t sure if he felt up to it for much longer. Did he hang on to his job because he couldn’t think of anything better to do? Had he inflated the importance of policing, made too much of it to drop everything when the time came? After a few years, not one of the buggers round here would remember him. They’d recruit replacement DCIs, new lads without a history, lacking a sense of what had mattered before, who had had power back then, informally of course, and why that was.

He often thought that everyone should be taught how to debrief, from the word go, whatever job you were training for. Novices should learn that the professional ins-and-outs they came to value were worthless in the end, and that you were around in your job only for a short while. It was a small part of your life that was at stake; you were there one moment, gone the next. Look at himself. There’d been others ahead of him and did he care about them? Hell, no. He didn’t.

Someone knocked on the door. Some saddo who had come to plead with him to turn down the music. Sodding bunnies.

But it was Sven, the only one in the house with some steel in him.

‘Ewert?’

‘Yes?’

‘Big trouble.’

‘What’s happening?’

‘Bernt Lund.’

That got to him. He raised his eyebrows and put down the paper he held.

‘Bernt Lund? What’s with him?’

‘He’s walked.’

‘The fuck he has!’

‘Again.’

Sven Sundkvist liked his old colleague and didn’t get fazed by the old boy’s sarcasm. He knew that Ewert’s bitterness, his fears, came from being too close to the day when he’d be forced to stop working, the day when he would be told that thirty-five years in service amounted to no more or less than precisely thirty-five years.

At least Ewert wanted something. He believed in what he did, unlike most of the others. So, never mind his surliness, his fits of bad temper, his oddities.

‘Come on, Sven. Get on with it.’

Sven gave an account of Lund’s hospital transport, the whole trip from Aspsås to Southern General’s casualty entrance. He described how he had used his elaborate body- belt chains to batter the two officers. Afterwards he had made off with the van. Now he was at liberty out there, probably stalking girls, children, little kids who’d just started school.

Ewert got up during this and limped restlessly about the room, waddling round his desk, manoeuvring his big body between the chair and the stand with potted plants. He stopped in front of the wastepaper bin, aimed with his good foot and kicked it hard.

‘How fucking stupid can you get, letting Lund out with only two escorts? What was Oscarsson thinking about? If he only could’ve been arsed to call us, we’d have sent a car and then that fucking freak wouldn’t have been at large!’

The kick had sent the bin flying, spewing banana peel and empty snuffboxes and torn envelopes all over the floor. Sven had seen it all before, and waited for the next instalment.

‘Åke Andersson and Ulrik Berntfors,’ he said. ‘Two good men. Andersson is the tall one, well over one hundred and ninety-something. Your age.’

‘I know who Andersson is.’

‘Now what?’

‘Tell you in a while. Can’t think now.’

Sven felt tired. It came over him suddenly. He wanted to go home. Home to Anita, to Jonas. He had finished for the day and couldn’t bear thinking about what had happened, that a child might be violated any moment now, or anything else to do with Bernt Lund. After all, he’d swapped to get the morning shift, because they’d planned to celebrate. He had some bottles of wine and a posh gateau in his car. They were meant to be drinking his birthday toast, soon.

Ewert noticed Sven’s tired eyes, his straying thoughts. Damn, he shouldn’t have kicked that effing bin. Sven disapproved of that kind of thing. Better say something. Be calm, cool.

‘Sven, you look tired. How are things?’

‘Oh, all right. I was about to leave. Go home. It’s my birthday today.’

‘Is it? Congratulations! How many years?’

‘Forty.’

Ewert whistled, then made a bow.

‘Well I never. Shake hands!’

He held out his hand, Sven grabbed it firmly and they shook for quite a long time. Then Ewert spoke.

‘But, young man. Regrettably, forty or not forty, you’re going nowhere now.’

Ewert had bad breath. Normally they never got that close.

‘You’re joking.’

‘Let me tell you something.’

Ewert pointed at his visitor’s chair. He was impatient, jabbing towards it with his index finger. Sven pulled his hand away and went to perch on the edge of the chair, still ready to leave any minute now.

‘I was in it up to my neck, the last time.’

‘The girls in the basement.’

‘Two girls, both nine years old. He had tied them up, jerked off all over them, raped them, cut them. Just like the time before. They were lying on this bare cement floor, staring at us. The medic confirmed that they’d been alive when Lund cut them, stuck a metal object into them, into the vagina, the anus. I don’t believe it, because I can’t bear to believe it. Have you thought about that, eh, Sven? That you can believe whatever you like, if you put your mind to it?’

Ewert Grens scared quite a few people. He didn’t stay put where you left him. His body was restless inside his creased shirt, his too-short trousers. Sven understood why people kept away from him, he had avoided the man himself. But he always felt that it was wrong to set out planning to humiliate someone. Simple enough rule. Anyway, he’d kept himself to himself until it seemed Ewert had accepted him. Even selected him, not that Sven understood why. The old boy must have needed someone and it happened to be him. Now Ewert didn’t seem dangerous any more. Big and grey and intense, but not dangerous.

He was sad, grieving over the two girls. He didn’t cry, not tears yet.

‘I did the questioning. I kept trying to look Lund in the eye: No way. No fucking way. He stared above me, past me, through me. I interrupted the session several times to demand that he look straight at me.’

Grens, you don’t get it.

Grens, listen.

I thought you were one of the guys who’d get it.

I don’t get the hots for all kids.

You’ve no reason to say that.

I only go for some of them, the ones who’re a bit… bigger.

Like that blonde, plump one.

You know the kind.

That’s important, Grens.

They’re whores.

Little slags with small feet.

Who think about cock.

They fucking well shouldn’t do that, you know.

Fucking little slags with tight cunts, they shouldn’t be thinking about cock all the time.

Human beings looked at each other when they talked. But no, not him. No way.

He looked at Sven. Sven looked at him. They were human.

‘I understand. And I don’t. If he’s one of those who don’t look at you, then why wasn’t he locked up in a special psycho institution? Like Säters secure? Or Karsudden? Or Sidsjön?’

Ewert bent to pick up the bin. He pulled out the tobacco from under his upper lip.

‘That’s what used to happen. His first time inside he got three years in Säter. But last time he was caught his mental disorder was diagnosed as minor. And then it’s off to the jug like everyone else. These days. Sex offenders’ unit, not a secure madhouse.’

Ewert swallowed whatever it was. Not quite tears.

Then, back to normality.

He changed the tape. More of Siw’s singing, of course. ‘Jazz Bacillus, 1959’. He stood in front of the loudspeaker for a moment with his eyes closed. He turned the volume up, crouched to pick up the rubbish, returning it to the bin. Then he straightened, took three steps back to get maximum impact, aimed and kicked the bin again. This time it went further, hitting the wall by the window.

He started speaking again.